INTRODUCTION

The 21st century is a period of rapid development of new technologies, communication tools and the Internet. The inevitable progress in the field of science and technology, especially computer technology, was to make it easier for a person to move around in a new reality. Any spatial boundaries and barriers have been reduced to a minimum. However, this situation has created not only many new opportunities, but also many threats to society. One of them is identity theft, which despite the fact that it does not have to be only cybercrime, it very often uses new forms of human identification (PIN, login, nicknames, passwords), and hence progressing computerization, both in purely social life and financial transactions (Sowirka Reference Sowirka2013:64). The world’s first phenomenon of identity theft penalized technologically highly developed countries such as the United States or Canada (Lach Reference Lach2012:30).

In Poland, there has been systematic technological development, access to the Internet and communication tools in recent years. The percentage of households equipped with at least one computer at home has been increasing on a systematic basis in recent years. In 2018 it reached 82.7% and was significantly higher in households with children. The number of regular computer users also increased over the period 2014–2018. Over 84% of households had access to the Internet at home in 2018, which is a 2.3 percentage point increase in comparison with the previous year. In the year 2018 over three-quarters of households in Poland had broadband access to the Internet at home. This percentage was higher by 1.7 percentage points than in the previous year. In 2018, 74.8% of persons aged 16–74 years used the Internet on a regular basis. The highest share of regular users was found among pupils and students (99.6%), the self-employed (92.60%) as well as residents of large cities (83.1%) and persons with tertiary education (96.6%). The percentage of regular Internet users was higher among the residents of Central Poland than other regions (Główny Urząd Statystyczny, Urząd Statystyczny w Szczecinie 2018:115–46).

What is puzzling, despite the above from 2012 to 2017, the number of people convicted of identity theft per year was between four and 79 people. Thus, it never exceed .03% of convictions for all crimes committed in each year and never exceeded 1% of all convictions for crimes against freedom – a category to which it belongs in Poland. Does this mean that the problem of identity theft does not exist in Poland? Or maybe there are reasons why disclosure of this crime in Poland is not possible? Is the crime of identity theft really inseparable from cyberspace? In order to answer the above questions, one should thoroughly analyse both the criminal-law regulations of this crime, the criminological aspects of the phenomenon, as well as reach for empirical research that approximates the realities of the phenomenon in Poland.

The Polish response to the threat of identity theft was to be Art. 190a § 2 of the Polish Penal Code (hereafter k.k. (Kodeks karny)). The legislator introduced it during the amendment of the Penal Code in 2011, in one article together with stalking.Footnote 1

The justification of the bill suggests that identity theft may consist of, for example: posting photographs of victims and comments revealing information about them on the Internet; ordering unwanted goods and services at the expense of victims; and dissemination of information about victims, for example, within the framework created without the knowledge and consent of victims of personal accounts on social networks (Lach Reference Lach2012:32).

Nowadays, the Internet and social networking sites have gained enormous importance in people’s private and professional lives. Increasingly, people base their business activities on building their own brand on ICT platforms, which have made the personal data and images of these people an integral part of their business activities, and at the same time a very valuable good. The impersonation of such a person, and thus the theft of its identity, in the era of today’s information society has become more acute than ever before (Nowak Reference Nowak2014:232).

According to the explanatory memorandum of the bill, it was decided to separate the crime of identity theft from stalking, arguing that this type of behaviour may be a one-off act, so it would not be possible to qualify it under the multi-criminal offence under Art. 190a § 1 k.k. (Lach Reference Lach2012:32) Therefore, from the very beginning in Poland identity theft was in the legislator’s intention closely related to the crime of stalking, that is, a crime against freedom than crimes against property. However, the form in which criminalization was made seems to contradict such an idea.

STATUTORY FEATURES OF THE OFFENCE

1. The Subject of the Offence

Both identity theft and the qualified type provided in § 3 are common offences. Any natural person capable of incurring criminal liability may commit them (Kłączyńska Reference Kłączyńska2014). According to Art. 10 § 1 k.k., the perpetrator of the offence may be a person who, when committing a prohibited act, was 17 years of age and was accountable at the time of committing the offence (Grześkowiak Reference Grześkowiak2012:102). The provisions do not provide for these offences or the liability of juveniles on the basis of the Penal Code or collective entities (Budyn-Kulik and Mozgawa Reference Budyn-Kulik and Mozgawa2012:18).

2. Subject of Protection of the Offence

Despite a common element with persistent harassment, which is protection against unlawful interference in the privacy sphere of the other person, in Art. 190a § 2 k.k. emphasis was placed on ensuring the protection of the individual’s identity, i.e. personal data and its image (Zoll Reference Zoll2013).

The justification of the draft law shows that the ratio legis of the analysed provision was to provide protection for the freedom to decide on the use of information about your personal life, which perfectly correlates with the right to protect your private life (Mozgawa Reference Mozgawa2010). The main good of the protected crime of identity theft is responsibility only for their own actions, and not for being attributed as a result of impersonating and misinforming other people by the impersonating person. The ownership of the entity is also a protected by-product of this type of prohibited act (Zoll Reference Zoll2013).

The individual subject of protection seems to be the right to the image of the person. The doctrine indicates that one may also consider adopting the right to identity. Due to the objective of the perpetrator (causing property or personal harm to the aggrieved party), it may be assumed that the non-material object of protection is the interests (both property and non-property interests) of the aggrieved party (Mozgawa Reference Mozgawa2015).

In Art. 190a § 3 k.k. human life is also protected in connection with the possibility of committing suicide as a result of identity theft or stalking (Zoll Reference Zoll2013).

Unlike most laws, it focuses on connections between identity theft and crime of stalking; therefore, not only on the aspect of material damage, but also on non-material harm. In the concept of the Polish legislator, it is not only a financial crime. If that were the case, it would be sufficient, for example, the provision of Art. 286 – a criminalizing crime of fraud or Art. 275 – criminalizing use, theft or misappropriation of a document stating the identity of another person or its property rights, etc.

Undoubtedly, the doctrine has been subjected to the legitimacy of including a provision that criminalizes the crime of identity theft in the chapter on crimes against freedom. There are voices that the main good to be protected is not freedom itself, but personal data, that is, some kind of information, so the more appropriate place for this provision would be Chapter XXXIII – Crimes against the protection of information (Sowirka Reference Sowirka2013:65). In the opinion of Budyn-Kulik, it would also be possible to consider placing the analysed provision among offences against honour and physical integrity, because – according to the author – the implementation of the offence under Art. 190a § 2 of the Penal Code can typically reconcile the honour and reputation of the aggrieved party (Budyn-Kulik Reference Budyn-Kulik2011).

It is difficult to say whether these opinions are correct. Due to the multiplicity of goods protected by this provision, the decision which is the most important is extremely difficult.

3. Objective Side of the Offence

Acting in the case of identity theft consists of “impersonating” another person. The term “pretend” needs to be clarified. Prior to the 2011 amendment, the Penal Code did not contain that term. The legislator has not introduced a legal definition of this term, so relying on the contents of the Dictionary of the Polish language (Słownik języka polskiego), the term “impersonate” means “pretends to be someone else” (Anonymous 2019).

The crime of identity theft can only be committed by acting and, more specifically, by “misleading the recipient of the information by creating an impression by means of the image or other personal data that the information comes from the person to whom the image or other personal data relates, when in fact this information comes from the perpetrator” (Zoll Reference Zoll2013). In conclusion, the perpetrator does not have to use a counterfeit or stolen document of the victim, it is enough that he uses his “image” or “other personal data”.

The Dictionary of the Polish language explains “image” in two ways: as “someone’s likeness in the drawing, picture, photograph, etc.” and “the way in which a given person or thing is perceived and presented” (Anonymous 2019). It seems that the application in the case of the crime of identity theft will have both definitions. One can imagine impersonating another person using a description of how uniformly and unequivocally perceived by a given society, for example, as the most popular clairvoyant in Poland. The legislator using the phrase “or other personal data” determines that the “image” belongs to the elements of personal data.

The explanation of the concept of “personal data” is not difficult due to the legal definition contained in Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of The European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) (Dz. Urz.UE.L Nr 119, str. 1). Article 4 of this Act states: “‘personal data’ means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person”. (European Parliament and Council 2016).

It is, therefore, an area encircled very broadly, including not only the social security, identity card, passport, fingerprints, tax identification number (TIN), address, parents’ names, retinal, as is commonly assumed, but all information allowing to indicate a specific person, e.g. a social function, a professional position (Sowirka Reference Sowirka2013:70). The doctrine also indicates the possibility of qualifying, in some circumstances, a telephone number or e-mail address to the scope of personal data (Drozd Reference Drozd2007:53).

Importantly, imitating someone, stylizing someone else like a famous actress, without wanting to mislead another person is not subject to criminal liability. The analysed crime, in contrast to the crime of stalking, belongs to the category of formal crimes. To fulfill it, it is enough to impersonate another person in order to cause him damage to property or personal damage; it is not necessary to have the effect of deceiving another person as to his identity or causing real harm to the victim (Budyn-Kulik and Mozgawa Reference Budyn-Kulik and Mozgawa2012:17).

The victim of identity theft due to the use of the terms “person” and “personal data” can only become a natural person. Regulation of 190a § 2 k.k., therefore, will not protect a legal person. However, there are situations in which information about a natural person may result from data on a legal person, so in this case, each case will be assessed individually by the trial body (Barta, Fajgielski, and Markiewicz Reference Barta, Fajgielski and Markiewicz2007:347). Such a case was noted by the author during examination of the court files, as will be seen later in the article. It also seems obvious that impersonation can only affect a person other than the perpetrator. However, a problem may arise when the perpetrator uses some of his personal data, and part of the victim’s, thus creating a self-contained identity, in which case the judgment of the court will also determine whether the data were significant enough and their scope so extensive that it was impersonated for another person body (Barta et al. Reference Barta, Fajgielski and Markiewicz2007:34).

In addition, impersonating another person is only possible if it is a person living in the real world. Due to the fact that a fictitious person does not have personal property according to Polish civil law, the perpetrator does not incur criminal liability under Art. 190a § 2 k.k. impersonating an imaginary figure, for example: film, literary (Kosonoga Reference Kosonoga2019). In addition to the above, it must also be a person living in the same sense. According to Polish civil law, a deceased person is no longer an entity – an identifiable natural person, which is necessary for the acceptance that certain information is personal data (Sowirka Reference Sowirka2013:67).

Art. 190a § 3 k.k. states: “If the act specified in § 1 or 2 results in a suicide attempt of the person, the offender is liable to imprisonment from one to 10 years”. So § 3 creates a type qualified by the succession of an act; moreover, it is a material crime, the result of which is a suicide attempt or suicide (Chamernik Reference Chamernik2013:313). The driving action in § 3 is accordingly the same as in the above-mentioned crime. For the implementation of the features of Art. 190 § 3 k.k. there must be an effect in the form of the victim’s losing of his own life, caused by the behaviour of the perpetrator. A causal link between the actions of the perpetrator and the attempt of the victim to take his own life is crucial to the inclusion of the actual state in the scope of the qualified type (Grześkowiak and Wiak Reference Grześkowiak and Wiak2012:860).

4. Subjective Side of the Offence

The crime of identity theft belongs to the category of intentional crimes. What is more, it is required to be committed by a perpetrator with a specific intent (dolus directus coloratus). The direct intention is not enough. The perpetrator will only be diable of identity theft if his purpose is to inflict damage to property or personal damage to another person (Budyn-Kulik Reference Budyn-Kulik2011).

The introduced procedure has been rightly criticized in the literature. It is doubtless justified to limit the penalization of behaviour only to those committed with the directional intention. The first of the arguments is the great difficulty in demonstrating the existence of dolus coloratus during criminal proceedings (Mozgawa Reference Mozgawa2015). Another is the unusually large sphere of behaviours that will not be criminalized because of existing this specific intent. For example, if identity theft is committed: just with the intention of enriching the perpetrator; without the desire to inflict damage to another person; to conceal his identity; to cause damage to another person than he pretended to be or in the situation of conditional intent (dolus eventualis) – when the perpetrator only agrees that his behaviour can cause damage to another person but he is indifferent whether the given effect will occur or not. Accordingly, correctly, M. Mozgawa postulated replacing dolus directus coloratus by just dolus directus (Lach Reference Lach2012:32–3).

In connection with the inclusion of the analysed provision in the chapter of crimes against freedom, the emphasis on criminalization should be placed on the protection of the right to one’s identity and the disposition of personal data. The insertion of additional restrictions in the form of specific intent caused that on the basis of this provision, goods and personal goods seem to be more important, which is in conflict with the adopted assumption of protecting the freedom of citizens (Budyn-Kulik Reference Budyn-Kulik2011).

The qualified type of § 3 can be committed with combined fault (culpa dolo exorta). Art. 190a § 3 k.k. establishes an intentional–unintentional offence, which means that the crime of identity theft is an intentional crime, and the result is a suicide attempt by the victim, covered by the unintentional offence of the offender (Budyn-Kulik and Mozgawa Reference Budyn-Kulik and Mozgawa2012:19). Therefore, according to Art. 9 § 3 k.k., the effect in the form of the victim’s suicide attempt is objectively predictable, and the perpetrator, even though he did not intend to lead him to that move, predicted or could have predicted it (Zoll Reference Zoll2013).

5. Punishment Threat and Prosecution

Offences contained in Art. 190a § 1 and § 2 k.k. are punished by up to three years’ imprisonment. The qualified type described in § 3 provides for the threat of imprisonment from one to 10 years.

In addition, in accordance with Art. 59 k.k. if the offence is subject only to imprisonment for up to three years, or to a lesser penalty, and the social impact of the act is not significant, the court may decide to impose a penal measure instead of the penalty, where the aim of the penalty is performed by the measure – so it is possible in some cases of identity theft.

The scope of criminal sanction assigned for offences under Art. 190a § 1 and 2 k.k. has been criticized already at the legislative stage. A. Sakowicz rightly suggested that the ailment in the form of only a penalty of imprisonment of up to three years is too tight. He applied for the possibility of an alternative sentence of a fine, restriction of liberty and imprisonment of up to two years, as stipulated in Art. 190 k.k. He argued for maintaining the uniformity of the Penal Code, in terms of the statutory threat of crimes of comparable form of interference in the sphere of individual freedom (Sakowicz Reference Sakowicz2010:7). This postulate was supported by other legal authorities, but the legislature did not consider those opinions.

As it turned out in practice, it turned out to be wrong. From court statistics it is clear that thanks to Art. 37a k.k. allowing a fine or restriction of liberty to be imposed if the Act provides for punishment imprisonment not exceeding eight years – courts have repeatedly used that opportunity. Instead of imprisonment, they imposed a fine or restriction of liberty (61% of all court rulings).

In addition, due to the lack of alternative prediction of criminal sanctions in accordance with Art. 58 § 1 k.k.Footnote 2 the legislator de facto eliminates the “presumption” of conditional suspension of imprisonment (Furman Reference Furman2012:22). This issue was also verified by statistics showing that courts more than 16 times more often ruled imprisonment with suspension of execution of punishment in relation to the absolute imprisonment – only 2% of perpetrators in 2011–2017 were sentenced to imprisonment. In conclusion, it should be considered whether the level of social harmfulness of identity theft in theoretical considerations has been overestimated without introducing alternative penalties.

Prosecution of crimes specified in § 1 and § 2 takes place at the request of the victim, while for § 3 the offence is prosecuted by a public authority. The overall assessment of such a procedure by the legislator is positive. The person has the right to decide whether his/her freedom to freely dispose of his/her personal data and image, as well as the freedom from unauthorized use of his or her identity, was infringed (Furman Reference Furman2012:23,27). The literature also refers to the premise of “special respect for family ties, which may induce the aggrieved party to forgive the perpetrator or cause that he prefers to settle the matter in the family” (Gardocka Reference Gardocka1980:74). The proprietor will be able to withdraw the application for prosecution at any stage of the pre-trial proceedings, both in the in rem and in personam phases. Bringing an indictment to court will limit the possibility of withdrawal of the application to start the court proceedings at the first main hearing.

In conclusion, the introduction of Art. 190a k.k. to the Polish Penal Code was a right and necessary action of the legislator, while the number of disputable and clearly uneven elements is quite numerous, as for such a short recipe. The postulate of de lege ferenda for correcting them is correct, which would definitely facilitate the practical application of Art. 190a k.k., positively influencing the rights of the victims and the work of law enforcement and court.

CRIMINOLOGICAL ASPECTS

1. The Phenomenon of Identity Theft

There are different types of crime: real crime (all offences committed in a given area at a given time); revealed crime (all acts of which law enforcement authorities have received information), also referred to as “apparent crime” as acts include acts, qualified at the initiation stage, and then did not prove to be a crime; identified crime (all acts whose criminal character was confirmed, thanks to preparatory proceedings); and sentenced crime (all acts classified as offences as a result of court proceedings) (Hołyst Reference Hołyst2007:80).

To illustrate the revealed crime, the crime structure (crime distribution in terms of the type of crimes committed) and the dynamics of crime (the pace and direction of changes in the elementary features of criminal acts) (Kuć Reference Kuć2013:46–7) are presented, based on police and court statistics.

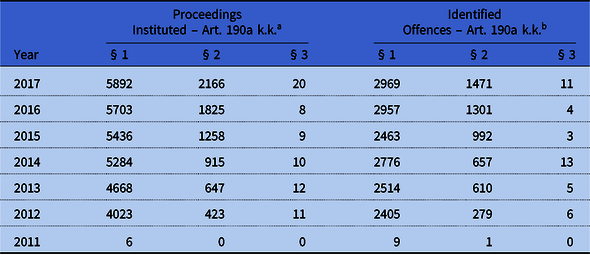

Table 1. Offences Under Art. 190a – Proceedings Instituted and Identified Offences in Poland in 2011–2017

Source: Own study, based on police statistics provided by the General Police Headquarters (Komenda Główna Policji; KGP) (http://www.statystyka.policja.pl/st/przestepstwa-ogolem/przestepstwa-kryminalne/63470,Przestepstwa-kryminalne-ogolem.html).

k.k, Kodeks karny (Penal Code).

a Initial proceedings instituted are proceedings initiated by the police organizational unit in connection with an event suspected of being a crime or initiated by the prosecutor’s office and handed over to the police for direct continuation. Investigations instituted in fact are also added to proceedings instituted, and then ended with the issuance of the decision to write off and enter the case in the register of offences. Excluded proceedings are not included in relation to the act and accomplice.

b An identified offence/crime is a crime or an offence prosecuted by public prosecution, including fiscal offence, covered by preparatory proceedings concluded as a result of which the offence has been confirmed.

There is a growing tendency both in the number of cases initiated and cases classified as stalking as well as those classified as a crime of identity theft (see Table 1). In 2012, there was a significant increase in the commenced and identified offences under Art. 190a k.k.; to clarify, the existing state of affairs may be so that only in mid-2011, Art. 190a k.k., people were not yet aware of the change, but in 2012 this information became more common and members of society began to enforce their rights. In subsequent years, up to the last year, the number of proceedings instituted has been steadily increasing, similarly as regards the offences identified. Only in 2015, compared with previous years, did this figure slightly decrease, so that in 2016 it again rose. The general upward trend can be explained by factors such as the propagation of information about identity theft among the public and technological development, which is followed by methods of impersonating another person, with simultaneous anonymity and impunity (Kosińska Reference Kosińska2008:47).

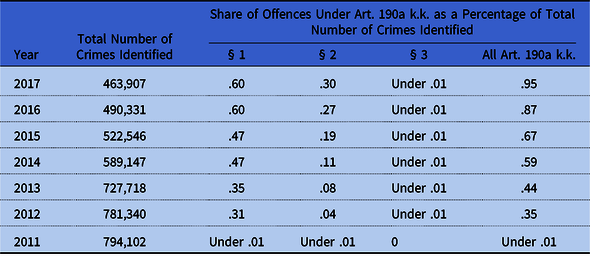

Table 2. Share of Offences Under Art. 190a k.k. as a Percentage of Total Number of Crimes Identified in Poland, 2011–2017

Source: Own study, based on police statistics provided by the General Police Headquarters (Komenda Główna Policji; KGP) (http://www.statystyka.policja.pl/st/przestepstwa-ogolem/przestepstwa-kryminalne/63470,Przestepstwa-kryminalne-ogolem.html).

k.k, Kodeks karny (Penal Code).

Since 2011, the number of all offences identified has been gradually decreasing; therefore it can be assumed that crime in Poland is also falling or law enforcement agencies have not received enough information about crimes (see Table 2). However, due to the technological progress and a significant decrease in the offences identified, the author approaches the first thesis. In contrast to the downward trend of all crimes committed in Poland in 2011–2016, the number of crimes under Art. 190a k.k. are increasing. Each year their percentage share increases, in 2017 it amounted to .95% (.60% – crime of stalking; .30% – crime of identity theft). The percentage share seems to be insignificant; however, it is necessary to be aware that the overall share of the categories of crimes against freedom in committed criminal offences is low, which will be demonstrated later in the work based on court statistics.

Figure 1 presents the territorial distribution of the offences identified under Art. 190a k.k. in Poland in 2016. The highest number of identity theft crimes was found in Warsaw (12.14%) and Kraków (11.46%), with the smallest in Opole (1.77%) and Białystok (2.15%). It is difficult to state the irrefutable reasons for which the distribution is as follows. The general trend is that there is less crime in smaller cities, while more developed cities have more. However, taking into account that in 2016 Warsaw had 1.754 million inhabitants and 158 crimes identified by the police, 28 identity thefts found in Białystok with 293,407 inhabitants, an almost six times smaller city, are proportional (over 5.5 times smaller number). The same applies to other cities. A certain deviation seems to be the 71 identity thefts found in Radom with 213,715 inhabitants; there were three times as many identity thefts than in Białystok, a bigger city. Radom is, however, one of the cities in which generally a high level of crime occurs, so despite the above, it can be concluded that in all cities, taking into account the population, the share of identity theft detected by the police is more or less at the same level.

Figure 1. Number of Offences Identified Under Art. 190a in 2016 – Division Into Police Units. KWP (Komenda Wojewódzka Policji; Voivodship Police Headquarters). Source: Own Study – Based on Police Statistics Provided by the General Police Headquarters (Komenda Główna Policji; KGP) (http://www.statystyka.policja.pl/st/przestepstwa-ogolem/przestepstwa-kryminalne/63470,Przestepstwa-kryminalne-ogolem.html).

As previously indicated, the low number of offences established under Art. 190a § 2 k.k., which in 2016 oscillated around .27%, also results from the fact that the same category of crimes against freedom is not popular among criminals.

The percentage of crimes against freedom in all crimes increased year by year (see Table 3). In 2017 a slight decrease was observed, while it still remained at the level of 3% of all convictions for criminal offences. However, this does not mean that due to their infrequent occurrence they are not crimes worthy of interest in criminological terms. Many of these behaviours are extremely painful for the victim, what is the reason why they were criminalized.

Table 3. Share of Convictions For Crimes Against Freedom as a Percentage of the Total Number of Convictions in Poland

Source: Based on court statistics (https://isws.ms.gov.pl/pl/baza-statystyczna/opracowania-wieloletnie/download,2853,41.html).

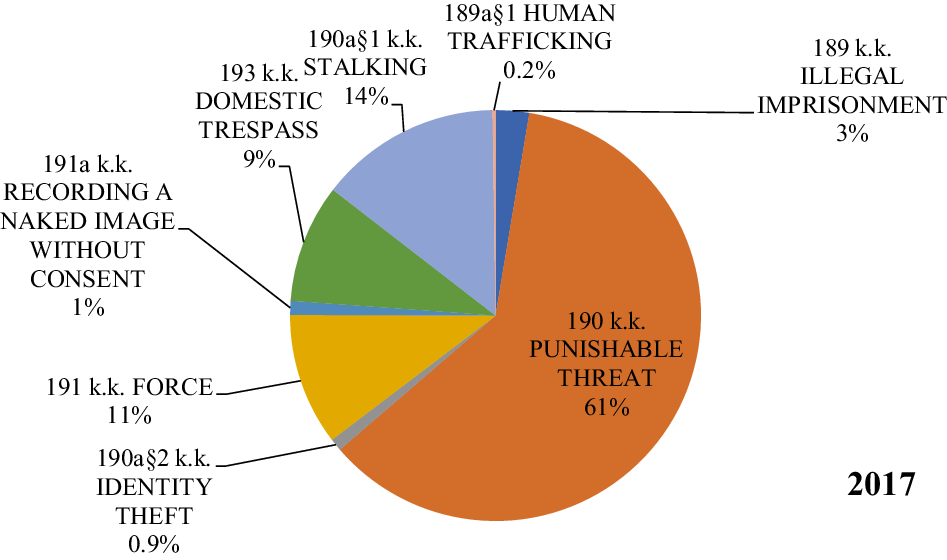

Despite the fact that the media often talk about threats related to technological development and the threat of identity theft, statistics show that less than 1% of convictions from the category of crimes against freedom is a crime of identity theft (Figure 2). Only judgments for trafficking in human beings were rarer. This shows a worrying dysfunction of the legal regulation of identity theft, in contrast to the crime of persistent harassment regulated in the same article, which has become the second most common crime against freedom.

Figure 2. Distribution of the Participation of Convictions for Particular Types of Offences Against Freedom in General of Convictions for Crimes of this Category in 2017. Source: Own Study – Based on Court Statistics (https://isws.ms.gov.pl/pl/baza-statystyczna/opracowania-wieloletnie/download,2853,41.html).

From 2012 to 2017, the percentage share of stalking crime more than doubled, becoming the second most-used crime among crimes against freedom (see Table 4). There is no indication that a similar trend would occur in the case of identity theft. Despite the fact that in 2017, in comparison with 2012, the number of convictions for identity theft has gradually increased and more than doubled, the number of convictions does not seem to be adequate, bearing in mind the technological leap in recent years in Poland and the number of offences identified by the police. This may be due to many factors, as was already pointed out, from the defectiveness of the construction of the provision, which is due to the fact that it is necessary to assign a direct intention. Such a thing is extremely difficult and it is relatively easy to defend against it, claiming that impersonating another person was only for fun, and not in order to cause damage to property or personal damage. Another reason may be a lack of training in the field of new technologies, which leads to the inability of the perpetrator to evade crime or to secure evidence of digital crime (see, also, Pływaczewski Reference Pływaczewski2017). Another reason for the very significant dark number of identity thefts can be the classification of this crime as other offences under the Penal Code, as a result of its defects – defamation, fraud, using another person’s identity document.

Table 4. Share of Convictions For Offences Under Art. 190a k.k. as a Percentage of Total Number of Convictions For Crimes Against Freedom in 2011–2017

Source: Own study, based on court statistics (https://isws.ms.gov.pl/pl/baza-statystyczna/opracowania-wieloletnie/).

k.k, Kodeks karny (Penal Code).

The number of crimes found in Art. 190a k.k. and perpetrators convicted of crimes in the analysed article is systematically growing. However, the number of convictions is drastically low. In 2016, the police reported the occurrence of 1301 identity thefts, but only 77 people were convicted of this crime in 2016, while in 2017 – 79 people. Thus, only 3.67% of people were prosecuted. This is not a normal result, considering that with a stalking crime from the same article, it is almost 37%. This proves, therefore, the difficulties at the stage of court proceedings in proving the guilty person’s fault, and thus the need to amend the provision.

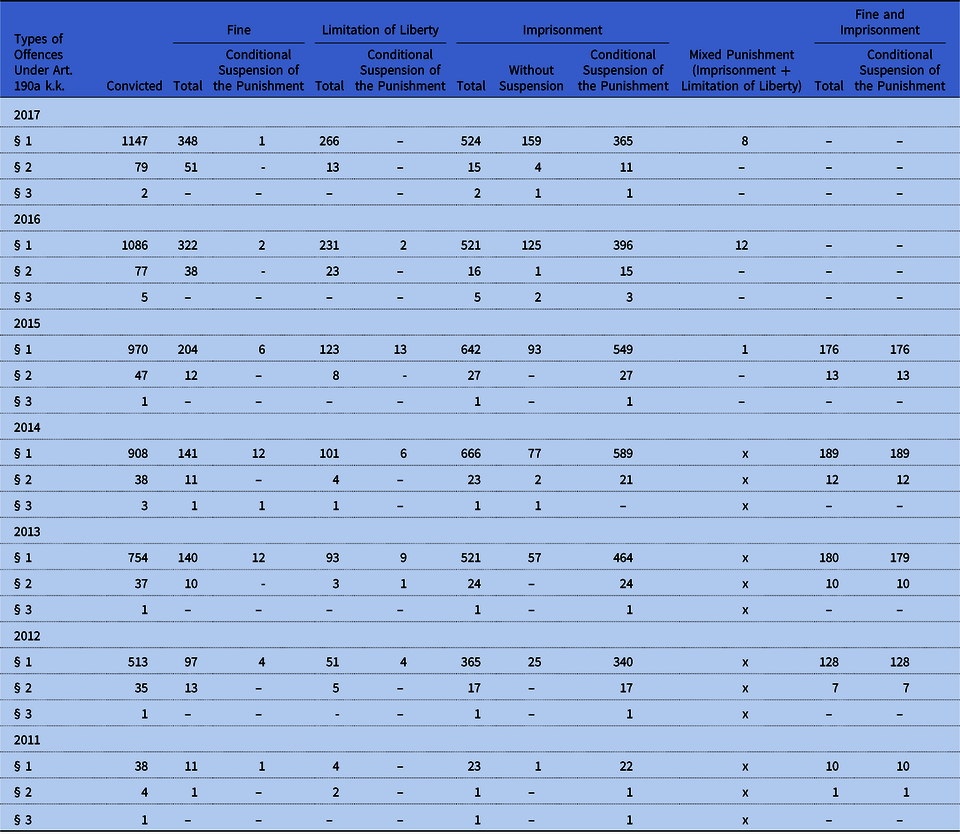

Table 5 shows the number of convictions for offences under Art. 190a k.k. and the types of penalties imposed since 2011, from entry into force, until 2017.

Table 5. Final Convictions of Adults on the Basis of Art. 190a k.k. in 2011–2017

Source: Based on court statistics (https://isws.ms.gov.pl/pl/baza-statystyczna/opracowania-wieloletnie/).

k.k, Kodeks karny (Penal Code).

As regards the crime of identity theft from 2011 to 2013, there was no sentence of absolute imprisonment. In 2014, there were two sentences of absolute imprisonment, which is 5.26% of all sentences imposed in this year. In 2015, this type of punishment was once again not sentenced, while in 2016, one was, and in 2017 – four, which is 5.06% of all imposed penalties. What can also be observed is that over 98% of sentences sentenced are punishments of imprisonment with suspension of execution or non-isolation penalties. In summary, in Poland almost all perpetrators of the crime of identity theft remain at large.

Within seven years, referring to the decisions of the courts regarding the type of punishments, it is apparent that the legislator overestimated the dangerousness of the identity theft (in the shape proposed by him), not including the possibility of choosing non-isolation punishments, such as fines or limitation of liberty. The courts must resort to other special provisions of the Penal Code to apply such penalties or simply they are suspending the execution of imprisonment – which is contrary to the legislator's intention.

2. Preventing and Combating Identity Theft

As part of criminal prevention, two crime prevention strategies can be distinguished: destructive (activities are focused on eliminating crime symptoms and directly directed against combated behaviours) and creative (focusing on taking “desirable activities to displace crime or leave no space for it”) (Kuć Reference Kuć2013:161). The methods of destructive strategy are: disabling, suppressing and threatening, while the creative strategy is: training, persuasion, propaganda, information and processing (Błachut, Gaberle, and Krajewski Reference Błachut, Gaberle and Krajewski2007:472–3). In terms of combating the crime of identity theft, both strategies are used.

Since 2011, a number of campaigns have been carried out in Poland to raise citizens’ awareness of methods of identity theft and ways to mitigate the risk of becoming a victim of this crime.

In October 2013, the General Inspector of Personal Data and Fellowes Company organized the “Identity Theft Identity Week” campaign. The action consisted of dissemination of a questionnaire, thanks to which it was possible to verify to what extent we protect our personal data.Footnote 3 In 2015, a joint informational and educational campaign of the Police and Credit Information Bureau was started under the slogan “Secure identity. Unscrewed life” creating a website with advice on, for example, dealing with loss of documents.Footnote 4 In the field of public awareness and training of law enforcement employees regarding the possibility of committing identity theft, conferences were organized all over Poland, for example on 19 January 2016 at the Higher Police School in Szczytno, under the honorary patronage of the Minister of Internal Affairs and Administration: “Identity Theft”.Footnote 5 On 22 November 2016 in Warsaw, the Ministry of Interior and Administration, the Inspector General for Personal Data Protection and the Department of Administration and Social Sciences of the Warsaw University of Technology organized a scientific conference “Identity Theft in the Internet”,Footnote 6 while on 2–6 December 2016 in Warsaw a nationwide scientific conference “License for Security” took place, organized by the Society of Legal and Forensic Initiatives, during which two panels were devoted to security in the network, including the issue of identity theft.Footnote 7

In 2014, an educational campaign was conducted by Fellowes Company in cooperation with the Credit Information Bureau. The slogan was “STOP! Do not be robbed. Protect your identity”, which verified the state of public knowledge about the phenomenon of identity theft. The research included, among others, the scale of the phenomenon, knowledge of the problem of identity theft, methods of protecting against theft and social behaviour affecting the level of threat.Footnote 8

Campaigns and information about the crime of identity theft, as well as how to protect against it, are often presented on websites not only of Police Headquarters, but also of banks or companies dealing with anti-virus software, for example, Bank PKO BP, Norton by Symantec, Avast Software s.r.o.

As the author has already pointed out, the prevention and combating of identity theft is a difficult task, taking into account the development of new technologies and new methods of breaking the security. However, it is quite effective to prevent an identity theft, as it is largely up to the victim whether or not he will become a victim of the crime of identity theft. Therefore, the strategy of preventing is informing the public about the possibilities of securing your personal data, and the same hindering the perpetrators of committing the analysed crime is a right procedure.

Has the presented crime prevention had a positive effect? It is difficult to define it clearly. Of course, with such a small number of crimes of identity theft in Poland, one could say that this is the merit of criminal prevention, but it does not seem to be a too idealistic assumption.

What is important is that these statistics based on Art. 190a § 2 k.k. do not show the broad concept of identity theft. The Penal Code also has other provisions allowing prosecution of perpetrators of this crime in its world meaning. A good example would be the provisions of chapters 33 and 34 – crimes against the protection of information and crimes against the credibility of documents, in particular: Art. 267,Footnote 9 Art. 268,Footnote 10 Art. 269a,Footnote 11 Art. 269b,Footnote 12 Art. 270Footnote 13 and more. What is paradoxical, for cases involving professional criminals who steal identities (hackers, using phishing), not for the purpose of causing damage to someone’s property or personal harm, but simply for enrichment, Art. 190a § 2 k.k. named identity theft cannot be used.

EMPIRICAL RESEARCH

1. Introduction

The research method used was the method of document examination. This is a form of indirect observation of a given phenomenon by means of court judgments. A significant research technique for this method is research on court files. The research tool allowing the implementation of this technique was a questionnaire of file research.

The subject of the analysis of the contents of court files was criminal proceedings for offences under Art. 190a k.k – crime of “stalking” and “identity theft”. The questionnaire for file research included 49 questions grouped into categories: general information and classification of the act; characteristics of the perpetrator of the offence; characteristics of the victim; description of the act committed; the course of the pre-trial and judicial proceedings. The time span of the research covered the years 2011–2016, that is from the entry into force of Art. 190a k.k. until the research started. Research started at the end of September 2016 at the District Court in Białystok.

In the course of the research process, all final legal proceedings for crimes under Art. 190 § 1 k.k. and 190 § 2 k.k., which were pending until September 2016 in the Białystok district, not including redeemed cases, were identified. A total of 60 cases under Article 190a k.k. including 53 cases classified as an offence under Art. 190a § 1 k.k., five cases classified as an offence under Art. 190a § 2 k.k. and two cases from Art. 190a § 1 k.k. in the collection with Art. 190a § 2 k.k. Thus, seven cases were qualified for the analysis of the crime of identity theft. Six people were convicted using Art. 190a § 2 and in one case the court conditionally discontinued the proceedings. In these seven cases were nine victims.

The aim of the research project was to determine the actual causes of this state of affairs and the nature of the phenomenon. This was done by characterizing perpetrators and their victims, relations between them, motives of action, forms of indentity theft, consequences caused by identity theft, efficiency of court decisions and punitive measures.

The main criminological problem was formulated in the form of the following question: How is the modern image of the crime of identity theft shaped in practice?

The main research problem of a criminological nature formulated in this way implies the need to refine the research field by defining detailed criminological research problems. These problems were defined in the form of the following questions:

(1) What are the characteristics of perpetrators and victims of identity theft?

(2) What are the relationships between perpetrators and victims?

(3) What are the reasons for identity theft?

(4) To what extent has the crime affected the lives of victims?

(5) What is the modus operandi of this crime?

(6) How did state institutions react to these behaviours?

(7) What punitive measures were imposed on perpetrators of identity theft?

(8) Were the pre-trial and trial effective?

2. General Information and Legal Qualification of Acts

The crime of identity theft during the research records of court cases, in three cases, occurred in confluence with other crimes, for example: with crime of stalking, crime of illegal access to information, damage to databases, punishable threat, bodily harm, domestic trespass, breach of personal inviolability, destruction and concealment of documents and slander.

The place of committing the crime of identity theft in four cases (57.14%) was Białystok. Due to the fact that more and more often the crime of identity theft is committed with the help of the Internet, it is not always possible to determine the place of committing a crime. This phenomenon occurred in three cases examined by the author, which constitutes 42.86% of all crimes under investigation.

It would seem that identity theft is usually a one-off behaviour in the cases examined; however, only two times it was one act (28.57%), three victims were subjected to a negative impact for a period from one month to six months (42.86%), two experienced impersonation for their identity for a period of two to three days (28.57%), in one case the actions filling the signs of identity theft were repeated for three years and one month (14.28%) (Table 6). Such long time spans resulted from confluence with stalking crime.

Table 6. Duration of the Crime of Identity Thefta

Source: Own research.

a Due to the fact that part of the duration was different for several of the victims (nine in total), eight different durations of behaviours contributing to identity theft were distinguished. For this reason, the sum of the number of perpetrators from the Table does not correspond to 7.

To convince citizens about the efficiency of justice, its speed of action is necessary. According to Art. 2 § 1 point 4 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, the matter should be resolved within a reasonable time.

As it emerged from the research, in spite of public opinion about the long-term process of claiming their rights by the victims, in Białystok the process of notifying about committing a crime to issuing a final court ruling ran fairly well. Of cases, 71.43% (five cases) were settled in the period from six months to one year, and 28.57% (two cases) in the period from three months to six months (Table 7).

Table 7. Period of Time From Submitting a Notification About Committing a Crime to Issuing a Final Judgment

Source: Own research.

3. Characteristics of the Perpetrators of Identity Theft Crime

Under Art. 190a § 2 k.k. the court qualified seven criminal cases. The number of criminals was also seven. As mentioned in the analysed seven criminal cases, two of them were qualified as a coincidence with Art. 190a § 1 k.k. (stalking).

In the case of identity theft, all perpetrators were male. The feminization rate of crime, or the share of women as crime perpetrators in Poland, is around 10% (Kędzierska Reference Kędzierska, Kędzierska and Pływaczewski2010:23–38). As a result, this crime in Białystok was under the feminization rate of crime.

In all cases investigated, the crime of identity theft was committed with full awareness of its actions without the influence of alcohol or drugs. None of the perpetrators of the crime of identity theft was addicted by any means.

Pursuant to the Polish Penal Code, an identity offence may also be committed only by a person who committed the act at the age of 17 years or more (Art. 10 § 1 k.k.) and was sane.

Most offenders from Art. 190a § 2 were in the range up to 34 years of age – people in early adulthood – i.e. 25–34 years (two offenders/28.57%) and juveniles (two offenders/28.57%) (Table 8). Slightly fewer people were in mid adulthood – i.e. 35–49 years (three offenders/42.86%). There was no single perpetrator over 49 years of age, which would confirm the assumption of free movement in the world of new technologies to commit identity theft, which is more common in younger people.

Table 8. Age of the Perpetrator at the Time of Committing the Act

Source: Own research.

The perpetrators of identity theft most often had secondary education (three offenders/42.86%), the second in the order turned out to be the holders of higher Master’s education (two people/28.58%), one person completed junior high school (14.28%) and vocational education (14.28%). There was not a single person with primary education (Table 9).

Table 9. Level of Education of the Perpetrator

Source: Own research.

Most of the perpetrators under Art. 190a § 2 k.k. are divorced (three offenders/42.86%), another large group are married (two offenders/28.58%) and single (two people/28.58%). So the division is aligned (see Table 10).

Table 10. Marital Status of the Perpetrator

Source: Own research.

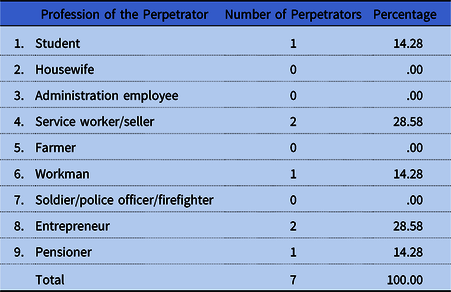

The largest part of the perpetrators are people from the socio-professional group “service worker/seller” (two people/28.58%) and “entrepreneur” (two people/28.58%), one representative (14.28%) was the “student” and “worker” categories and one person was a pensioner (see Table 11).

Table 11. Profession of the Perpetrator

Source: Own research.

Information taken from indictments regarding the employment of perpetrators of offences under Art. 190a § 2 k.k. indicate that the employment of perpetrators is also equal: 42.86% (three perpetrators) are in a situation of unemployment, three perpetrators (42.86% of the total) are employed on a permanent basis, and one person (14.28%) has an odd job. Thus, there is a slight advantage of people who have an uncertain situation as to their employment (four persons/57.14%) (Table 12).

Table 12. Employment Status of the Perpetrator

Source: Own research.

An important issue from the point of criminology is to determine how many convicts were previously punished. The literature indicates that about one-third of convicted persons had previously been subjected to punishment (Błachut et al. Reference Błachut, Gaberle and Krajewski2007:223–4).

Of those covered by the study, 71.42% (five people) were punished for the first time, while 28.58% (two people) had been previously convicted (Table 13). This is slightly different from the one-third of convicted criminals, but it still oscillates around the theory adopted by criminological literature.

Table 13. Prior Criminality of the Perpetrator

Source: Own research.

In the files of criminal cases investigated regarding the crime of identity theft all the perpetrators were in a good state of health, with neither physical nor mental disorders.

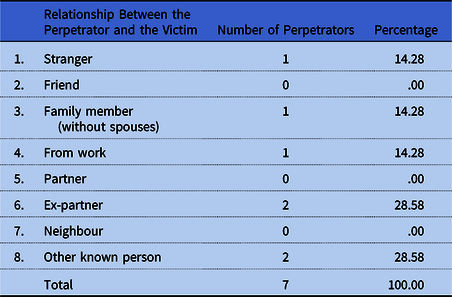

Most offenders from Art. 190a § 2 k.k. were ex-partners of the victims (two persons/28.58%), and two others belonged to the category of “other known person” (two offenders/28.58%). One offender and victim knew each other from work (14.28%), another was a member of the family (one offender/14.28%), and one offender was a person unknown to the victim (14.28%). Thus, the perpetrator was usually known to the aggrieved person (Table 14).

Table 14. Relationship Between the Perpetrator and the Victim

Source: Own research.

4. Characteristics of the Victim of Identity Theft Crime

In seven cases classified as a crime of identity theft, nine victims of crime occurred.

In the case of the crime of identity theft, only a few more victims are women (five victims/55.5%), and there were four male victims (44.44% of the total number of victims). In terms of the gender of the victims, we can speak of an even number.

Most victims of crime from Art. 190a § 2 k.k. were the age of 25–34 years (three people/33.33%) and 50–69 years (three victims/33.33%), slightly fewer were aged 35–49 years (two people/22.22%). One person (11.11%) belonged to the age category 17–24 years (Table 15). Interestingly, in contrast to the perpetrators who were under 34 years of age, the victims were people up to 69 years of age – this may indicate the need for greater preventive measures in this group, as a group that is not so familiar with new technologies.

Table 15. Age of the Victim at the Time of the Act

Source: Own research.

During the analysis of court files, in five cases (55.56%), it was impossible to determine what level of education victims of identity theft had completed (see Table 16). According to the information contained in the files, two victims had a Master’s degree (22.22%), and another two victims (22.22%) had finished secondary education.

Table 16. Level of Education of the Victim

Source: Own research.

Most victims from Art. 190a § 2 k.k were married (five victims/55.56%); slightly fewer, four people (44.44%), were unmarried (see Table 17). Marital status, like gender, is also quantified.

Table 17. Marital Status of the Victim

Source: Own research.

One group of victims was “students” (two persons/22.22%) and “entrepreneurs” (two persons/22.22%); for two people (22.22%) there was no information on this subject. One person (11.11%) was in the category of “service worker/seller” and one from “workers” and “soldier/police officer/firefighter” (see Table 18).

Table 18. Profession of the Victim

Source: Own research.

According to the criminal records, 66.67% (six victims) have permanent employment, and 33.33% (three people) have no employment (see Table 19).

Table 19. Employment Status of the Victim

Source: Own research.

5. Description of the Committed Act

The crime of identity theft of two perpetrators was committed using a telephone call (28.57%), and six offenders (85.71%) impersonated another person via the Internet (see Table 20). It shows what a huge impact that technological development has on the form of the crime, and in particular the Internet, thanks to which the perpetrators are able to find increasingly new and more effective methods of impersonation and at the same time not requiring much effort and even leaving their own homes.

Table 20. Forms of Impersonation for Another Persona

Source: Own research.

a A few of the perpetrators used various forms of impersonating another person, therefore the sum from the Table is not equal to the sum of the perpetrators.

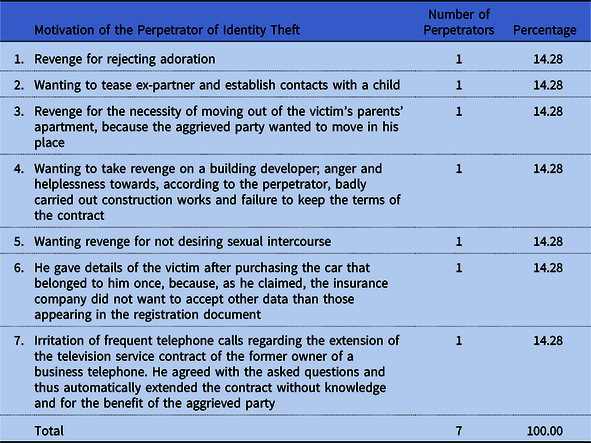

In the files studied, three perpetrators (42.86%) impersonated once and also three others three times. Only one perpetrator (14.29%) performed such activities four times (see Table 21). Thus, it can be seen that the perpetrators are not usually limited to one-time impersonation for another person, but impersonate multiple characters, which is quite understandable due to the motivation of the perpetrators, as shown in Table 22 below.

Table 21. Frequency of Identity Theft

Source: Own research.

Table 22. Motivation of the Perpetrator of Identity Theft

Source: Own research.

The motivation for the theft of identity in the files was mainly the desire to take revenge and tease the victim – this motivation was presented by five perpetrators, that is 71.43% of the total.

In one case (14.28%), the perpetrator only wanted the television service representatives to stop calling, making life impossible for him on his work telephone number, which once belonged to the client. By agreeing to the consultant’s questions about personal data, to his surprise he extended the contract with the operator for the benefit of the victim. He thought that the need for a signature, and the telephone conversation alone were not enough to extend the contract. The court, however, in this case ignored the necessary element of this crime, which is the dolus directus coloratus in the form of willingness to cause personal or property damage. The court did not allow presentation of billing indicating the persistence of the television service representatives, which would confirm the defendant’s version. In the next case (14.28%), the perpetrator also denied that he intended to cause personal injury to the aggrieved party (14.28%) by providing personal data from the car registration certificate. The court also did not give the perpetrator the faith. In accordance with the above, the element of the specific intent objectively really causes problems of proof, but also provides the perpetrator with the possibility of manipulation. This does not change the fact that in some cases courts are beginning to interpret the law regulating the crime of identity theft by unreservedly rejecting the requirement of a dolus directus coloratus.

I will now return to the question of whether you can impersonate a legal entity. In one of the cases the perpetrator impersonated the partners of a real estate company and used their private images and personal data when he registered the domain on the home.pl portal (using the surname of the victims and the real estate, for example, smith-realestatecompany.pl), on whose page he placed the data relating to the victims’ original site without the consent and knowledge of the victims. On the website he made slander against the company established by the victims, and then after blocking the subject page, on the same day registered a similar domain using the victim’s data. On this site he placed private photographs without the consent and knowledge of the victims, in such a way that he copied them from pages placed by the victims on facebook, as well as pretending to be a victim using an e-mail address (smith-realestate@wp.pl), he sent e-mail messages to the company’s clients, defaming the injured party with a link to the website he created. These acts exposed the aggrieved parties and their company to loss of social trust and property losses. The above proves that it is possible to impersonate a company if the data concern their owners’ data. In this case, the court adjudicated three months’ imprisonment suspended for two years and obliged the accused to apologize to the victims by posting an apology in the local newspaper in the property supplement within one month from the validation of the verdict.

6. The Course of the Pre-Trial and Judicial Proceedings

Many times, the victims may be concerned that reporting a case to law enforcement authorities will not result in any positive changes, and the persecutors will not change their behaviour. The author decided to check this thesis in her research. In the case of identity theft, all the perpetrators after the victim’s complaint to the police completely ceased to impersonate the victim during the proceedings.

In four cases examined (57.14%), one or several preventive measures were applied to the perpetrator of the crime of identity theft. Most often it was police supervision (two offenders/28.57%) and a ban on contacting the victim (two offenders/28.57%). Each one of three perpetrators received one preventive measure: a ban on approaching the victim, detention and a ban on leaving the country (see Table 23).

Table 23. Applied Preventive Measuresa

Source: Own research.

a In the case of several perpetrators, more than one preventive measure was applied, therefore the sum of preventive measures is not equal to 7.

One of the more important issues is the evidence used to prove the guilt of the perpetrator of identity theft. Table 24 shows those that were used in the cases in Białystok.

Table 24. Evidence in the Casesa

Source: Own research.

a In several cases, more than one piece of evidence was used in trial, therefore the sum of evidence is not equal to 7.

In 57.14% of cases (four cases), evidence of close relatives/strangers became evidence, e-mails became the second most used evidence (three cases/42.86%); in two cases (28.57%) expert opinion was used, and also photographs and posts posted on the Internet.

Six perpetrators (85.71% of the total) were sentenced to imprisonment with suspension of the sentence (Table 25). The proceedings were conditionally discontinued with one perpetrator. None of the perpetrators was sentenced to absolute imprisonment. Once again, the penalties imposed seem to be much milder than those anticipated by the legislator at the stage of introducing the crime of identity theft into the Penal Code.

Table 25. Penalties

Source: Own research.

In the cases examined, punitive measures were imposed against 71.43% of perpetrators (five perpetrators) (Table 26). Two perpetrators (28.60%) were ordered to provide compensation to the aggrieved party in the amount of 200 Polish zloty (PLN) and 2000 PLN. One perpetrator (14.30%) was required to refrain from any personal or telephone/Internet contact with victims, curator’s supervision, the obligation to apologize to the victim by posting an apology in the newspaper and a benefit to the Victims Assistance Fund and Post-Penitentiary Assistance.

Table 26. Penal Measuresa

Source: Own research.

PLN, Polish zloty.

a The sum of the perpetrators is not equal to 7 because some of perpetrators received more than one penal measure.

The vast majority of perpetrators (six offenders/85.71%) of identity theft had voluntarily admitted guilt. Only one person (14.29%) did not plead guilty/voluntarily punished (Table 27).

Table 27. Voluntary Submission to Punishment/Confession

Source: Own research.

In the analysed files, the author has not found a single perpetrator appealing against the verdict of the court in the first instance.

CONCLUSION

In Poland, despite the crime of identity theft being criminalized in a separate provision, it does not guarantee protection against attacks by professional criminals who make themselves the source of identity theft. In relation to this type of cases, it is necessary to use other legal regulations.

As empirical research shows, the current form of the criminalization of identity theft protects mainly from behaviour of perpetrators from among known people. Their actions are characterized by emotional involvement and the will to annoy or revenge. This is a good start and unnecessarily limits more serious cases of attacks.

Although the number of crimes found in Art. 190a k.k. and perpetrators convicted of crimes in the analysed article are systematically growing, the number of convictions is disproportionally low compared with technological development in recent years. The number of convicted perpetrators of indentity crime is also very low – 3.67% of the identity crimes identified by the police. This proves that the erroneous legal regulation must be corrected, as well as training of investigative bodies in the field of cybercrime and new technologies. Prophylactic activities focused on educating the public, in particular young people and the elderly, on threats related to new technologies, should also be promoted.

The dark number of identity thefts in Poland is also due to the necessity of using other criminal laws to bring perpetrators to criminal liability. Therefore, if the statistics of crime of identity theft is one of the marginal crimes in Poland, it seems to be something of an oversimplification.

Fortunately, the draft amendment to the analysed provision includes the doubts expressed in the article and it is possible that the situation will improve significantly soon.Footnote 14

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Emil W. Pływaczewski and my PhD Supervisor, Professor Ewa M. Guzik-Makaruk, for supporting my scientific development and encouraging me to write this article.

Aleksandra Stachelska is a research assistant at the International Centre of Criminological Research and Expertise, Faculty of Law, University of Białystok and PhD candidate in the Department of Criminal Law and Criminology, Faculty of Law, University of Białystok, Poland. Her field of interest comprises criminal law and criminology with focus on juvenile crime and cybercrime.