Introduction

The search for life elsewhere in the universe is a central occupation of astrobiology and scientists have often looked to Earth analogues for extremophile bacteria, life under varying climate states and the genesis of life itself. A subset of this search is the prospect for intelligent life, and then a further subset is the search for civilizations that have the potential to communicate with us. A common assumption is that any such civilization must have developed industry of some sort. In particular, the ability to harness those industrial processes to develop radio technologies capable of sending or receiving messages. In what follows, however, we will define industrial civilizations here as the ability to harness external energy sources at global scales.

One of the key questions in assessing the likelihood of finding such a civilization is an understanding of how often, given that life has arisen and that some species are intelligent, does an industrial civilization develop? Humans are the only example we know of, and our industrial civilization has lasted (so far) roughly 300 years (since, for example, the beginning of mass production methods). This is a small fraction of the time we have existed as a species, and a tiny fraction of the time that complex life has existed on the Earth's land surface (~400 million years ago, Ma). This short time period raises the obvious question as to whether this could have happened before. We term this the ‘Silurian hypothesis’Footnote 1.

While much idle speculation and late night chatter has been devoted to this question, we are unaware of previous serious treatments of the problem of detectability of prior terrestrial industrial civilizations in the geologic past. Given the vast increase in work surrounding exoplanets and questions related to detection of life, it is worth addressing the question more formally and in its astrobiological setting. We note also the recent work of Wright (Reference Wright2017) which addressed aspects of the problem and previous attempts to assess the likelihood of solar system non-terrestrial civilization such as Haqq-Misra & Kopparapu (Reference Haqq-Misra and Kopparapu2012). This paper is an attempt to remedy the gap in a way that also puts our current impact on the planet into a broader perspective. We first note the importance of this question to the well-known Drake equation. Then we address the likely geologic consequences of human industrial civilization and then compare that fingerprint to potentially similar events in the geologic record. Finally, we address some possible research directions that might improve the constraints on this question.

Relevance to the Drake equation

The Drake equation is the well-known framework for estimating of the number of active, communicative extraterrestrial civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy (Drake, Reference Drake1961, Reference Drake, Mamikunian and Briggs1965). The number of such civilizations, N, is assumed to be equal to the product of; the average rate of star formation, R*, in our Galaxy; the fraction of formed stars, f p, that have planets; the average number of planets per star, n e, that can potentially support life; the fraction of those planets, f l, that actually develop life; the fraction of planets bearing life on which intelligent, civilized life, f i, has developed; the fraction of these civilizations that have developed communications, f c, i.e., technologies that release detectable signs into space, and the length of time, L, over which such civilizations release detectable signals.

If over the course of a planet's existence, multiple industrial civilizations can arise over the span of time that life exists at all, the value of f c may in fact be >1.

This is a particularly cogent issue in light of recent developments in astrobiology in which the first three terms, which all involve purely astronomical observations, have now been fully determined. It is now apparent that most stars harbour families of planets (Seager, Reference Seager2013). Indeed, many of those planets will be in the star's habitable zones (Dressing & Charbonneau, Reference Dressing and Charbonneau2013; Howard, Reference Howard2013). These results allow the next three terms to be bracketed in a way that uses the exoplanet data to establish a constraint on exo-civilization pessimism. In Frank & Sullivan (Reference Frank and Sullivan2016) such a ‘pessimism line’ was defined as the maximum ‘biotechnological’ probability (per habitable zone planets) f bt for humans to be the only time a technological civilization has evolved in cosmic history. Frank & Sullivan (Reference Frank and Sullivan2016) found f bt in the range ~10−24–10−22.

Determination of the ‘pessimism line’ emphasizes the importance of three Drake equation terms f l, f i and f c. Earth's history often serves as a template for discussions of possible values for these probabilities. For example, there has been considerable discussion of how many times life began on Earth during the early Archean given the ease of abiogenisis (Patel et al., Reference Patel2015) including the possibility of a ‘shadow biosphere’ composed of descendants of a different origin event from the one which led to our Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) (Cleland & Copley, Reference Cleland and Copley2006). In addition, there is a long-standing debate concerning the number of times intelligence has evolved in terms of dolphins and other species (Marino, Reference Marino, Vakoch and Dowd2015). Thus, only the term f c has been commonly accepted to have a value on Earth of strictly 1.

Relevance to other solar system planets

Consideration of previous civilizations on other solar system worlds has been taken on by Wright (Reference Wright2017) and Haqq-Misra & Kopparapu (Reference Haqq-Misra and Kopparapu2012). We note here that abundant evidence exists of surface water in ancient Martian climates (3.8 Ga) (e.g. Achille & Hynek, Reference Achille and Hynek2010; Arvidson et al., Reference Arvidson2014), and speculation that early Venus (2 Ga to 0.7 Ga) was habitable (due to a dimmer sun and lower CO2 atmosphere) has been supported by recent modelling studies (Way et al., Reference Way2016). Conceivably, deep drilling operations could be carried out on either planet in future to assess their geological history. This would constrain consideration of what the fingerprint might be of life, and even organized civilization (Haqq-Misra & Kopparapu, Reference Haqq-Misra and Kopparapu2012). Assessments of prior Earth events and consideration of Anthropocene markers such as those we carry out below will likely provide a key context for those explorations.

Limitations of the geological record

That this paper's title question is worth posing is a function of the incompleteness of the geological record. For the Quaternary (the last 2.5 million years), there is widespread extant physical evidence of, for instance, climate changes, soil horizons and archaeological evidence of non-Homo Sapiens cultures (Denisovians, Neanderthals, etc.) with occasional evidence of bipedal hominids dating back to at least 3.7 Ma (e.g. the Laetoli footprints) (Leakey & Hay, Reference Leakey and Hay1979). The oldest extant large-scale surface is in the Negev Desert and is ~1.8 Ma old (Matmon et al., Reference Matmon2009). However, pre-Quaternary land-evidence is far sparser, existing mainly in exposed sections, drilling and mining operations. In the ocean sediments, due to the recycling of ocean crust, there only exists sediment evidence for periods that post-date the Jurassic (~170 Ma) (ODP Leg 801 Team, 2000).

The fraction of life that gets fossilized is always extremely small and varies widely as a function of time, habitat and degree of soft tissue versus hard shells or bones (Behrensmeyer et al., Reference Behrensmeyer, Kidwell and Gastaldo2000). Fossilization rates are very low in tropical, forested environments but are higher in arid environments and fluvial systems. As an example, for all the dinosaurs that ever lived, there are only a few thousand near-complete specimens, or equivalently only a handful of individual animals across thousands of taxa per 100,000 years. Given the rate of new discovery of taxa of this age, it is clear that species as short-lived as Homo sapiens (so far) might not be represented in the existing fossil record at all.

The likelihood of objects surviving and being discovered is similarly unlikely. Zalasiewicz (Reference Zalasiewicz2009) speculates about preservation of objects or their forms, but the current area of urbanization is <1% of the Earth's surface (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Friedl and Potere2009), and exposed sections and drilling sites for pre-Quaternary surfaces are orders of magnitude less as fractions of the original surface. Note that even for early human technology, complex objects are very rarely found. For instance, the Antikythera Mechanism (ca. 205 BCE) is a unique object until the Renaissance. Despite impressive recent gains in the ability to detect the wider impacts of civilization on landscapes and ecosystems (Kidwell, Reference Kidwell2015), we conclude that for potential civilizations older than about 4 Ma, the chances of finding direct evidence of their existence via objects or fossilized examples of their population is small. We note, however, that one might ask the indirect question related to antecedents in the fossil record indicating species that might lead downstream to the evolution of later civilization-building species. Such arguments, for or against, the Silurian hypothesis would rest on evidence concerning highly social behaviour or high intelligence based on brain size. The claim would then be that there are other species in the fossil record which could, or could not, have evolved into civilization-builders. In this paper, however, we focus on physicochemical tracers for previous industrial civilizations. In this way, there is an opportunity to widen the search to tracers that are more widespread, even though they may be subject to more varied interpretations.

Scope of this paper

We will restrict the scope of this paper to geochemical constraints on the existence of pre-Quaternary industrial civilizations, that may have existed since the rise of complex life on land. This rules out societies that might have been highly organized and potentially sophisticated but that did not develop industry and probably any purely ocean-based lifeforms. The focus is thus on the period between the emergence of complex life on land in the Devonian (~400 Ma) in the Paleozoic era and the mid-Pliocene (~4 Ma).

The geological footprint of the Anthropocene

While an official declaration of the Anthropocene as a unique geological era is still pending (Crutzen, Reference Crutzen2002; Zalasiewicz et al., Reference Zalasiewicz2017), it is already clear that our human efforts will impact the geologic record being laid down today (Waters et al., Reference Waters2014). Some of the discussion of the specific boundary that will define this new period is not relevant for our purposes because the markers proposed (ice core gas concentrations, short-half-lived radioactivity, the Columbian exchange) (e.g. Lewis & Maslin, Reference Lewis and Maslin2015; Hamilton, Reference Hamilton2016) are not going to be geologically stable or distinguishable on multi-million year timescales. However, there are multiple changes that have already occurred that will persist. We discuss a number of these below.

There is an interesting paradox in considering the Anthropogenic footprint on a geological timescale. The longer human civilization lasts, the larger the signal one would expect in the record. However, the longer a civilization lasts, the more sustainable its practices would need to have become in order to survive. The more sustainable a society (e.g. in energy generation, manufacturing or agriculture) the smaller the footprint on the rest of the planet. But the smaller the footprint, the less of a signal will be embedded in the geological record. Thus, the footprint of civilization might be self-limiting on a relatively short timescale. To avoid speculating about the ultimate fate of humanity, we will consider impacts that are already clear, or that are foreseeable under plausible trajectories for the next century (e.g. Nazarenko et al., Reference Nazarenko2015; Köhler, Reference Köhler2016).

We note that effective sedimentation rates in ocean sediment for cores with multi-million-year-old sediment are of the order of a few cm/1000 years at best, and while the degree of bioturbation may smear a short-period signal, the Anthropocene will likely only appear as a section a few cm thick, and appear almost instantaneously in the record.

Stable isotope anomalies of carbon, oxygen, hydrogen and nitrogen

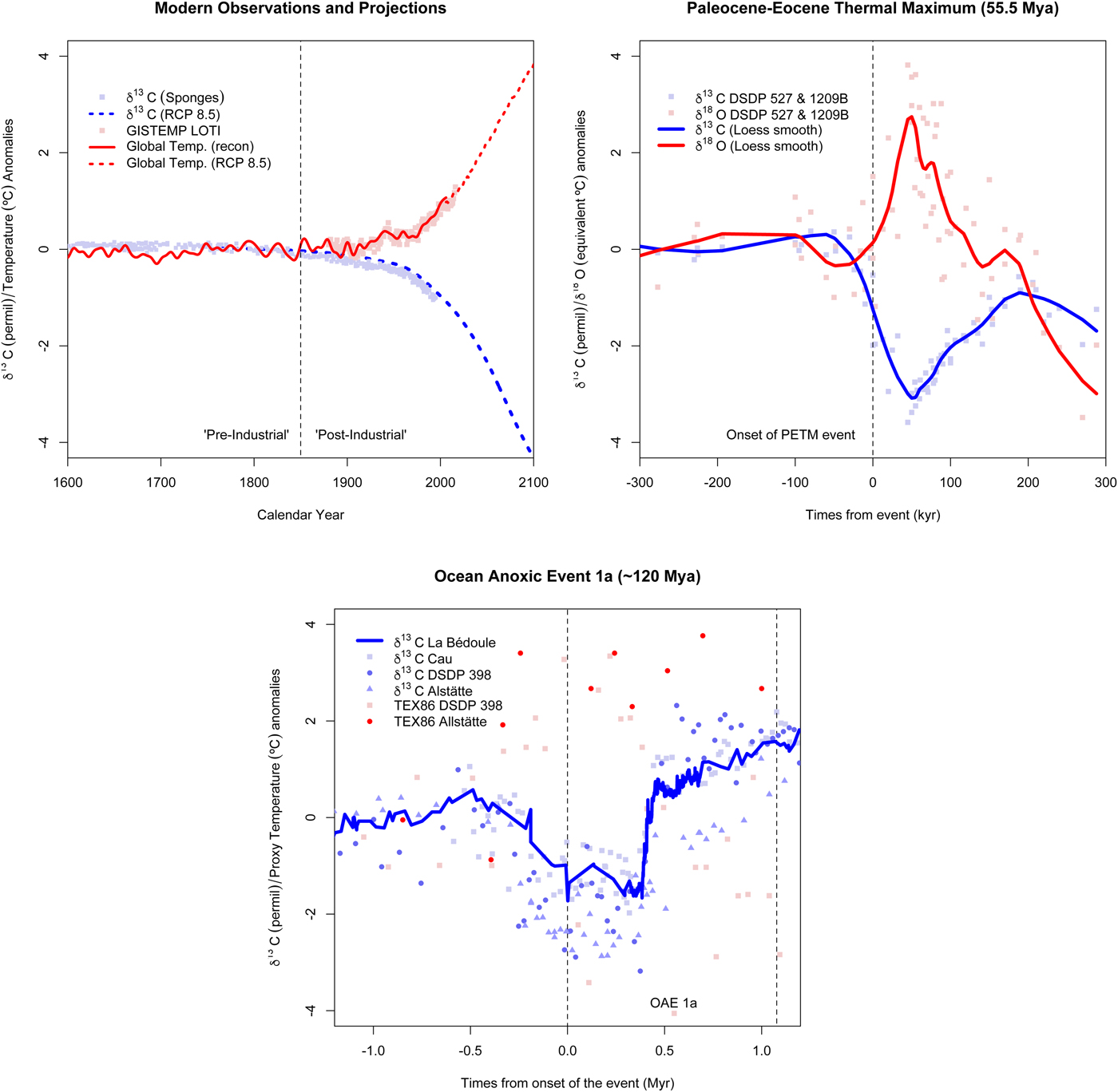

Since the mid-18th century, humans have released over 0.5 trillion tonnes of fossil carbon via the burning of coal, oil and natural gas (Le Quéré et al., Reference Le Quéré2016), at a rate orders of magnitude faster than natural long-term sources or sinks. In addition, there has been widespread deforestation and addition of carbon dioxide into the air via biomass burning. All of this carbon is biological in origin and is thus depleted in13C compared with the much larger pool of inorganic carbon (Revelle & Suess, Reference Revelle and Suess1957). Thus, the ratio of 13C to 12C in the atmosphere, ocean and soils is decreasing (an impact known as the ‘Suess Effect’ Quay et al., Reference Quay, Tilbrook and Wong1992) with a current change of around − 1‰ δ 13C since the pre-industrial (Böhm et al., Reference Böhm2002; Eide et al., Reference Eide2017) in the surface ocean and atmosphere (Fig. 1(a)).

Fig. 1. Illustrative stable carbon isotopes and temperature (or proxy) profiles across three periods. (a) The modern era (from 1600 CE with projections to 2100). Carbon isotopes are from sea sponges (Böhm et al., Reference Böhm2002), and projections from Köhler (Reference Köhler2016). Temperatures are from Mann et al. (Reference Mann2008) (reconstructions), GISTEMP (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen2010) (instrumental) and projected to 2100 using results from Nazarenko et al. (Reference Nazarenko2015). Projections assume trajectories of emissions associated with RCP8.5 (van Vuuren et al., Reference van Vuuren2011). (b) The Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (55.5 Ma). Data from two DSDP cores (589 and 1209B) (Tripati & Elderfield, Reference Tripati and Elderfield2004) are used to estimate anomalous isotopic changes and a loess smooth with a span of 200 kya is applied to make the trends clearer. Temperatures changes are estimated from observed δ 18Ocarbonate using a standard calibration (Kim & O'Neil, Reference Kim and O'Neil1997). (c) Oceanic Anoxic Event 1a (about 120 Ma). Carbon isotopes are from the La Bédoule and Cau cores from the paleo-Tethys (Kuhnt et al., Reference Kuhnt, Holbourn and Moullade2011; Naafs et al., Reference Naafs2016) aligned as in Naafs et al. (Reference Naafs2016) and placed on an approximate age model. Data from Alstätte (Bottini & Mutterlose, Reference Bottini and Mutterlose2012) and DSDP Site 398 (Li et al., Reference Li2008) are aligned based on coherence of the δ 13C anomalies. Temperature change estimates are derived from TEX86 (Mutterlose et al., Reference Mutterlose2014; Naafs et al., Reference Naafs2016). Note that the y-axis spans the same range in all three cases, while the timescales vary significantly.

As a function of the increase of fossil carbon into the system, augmented by black carbon changes, other non-CO2 trace greenhouse gases (e.g. N2O, CH4 and chloro-fluoro-carbons (CFCs)), global industrialization has been accompanied by a warming of about 1°C so far since the mid-19th century (Bindoff et al., Reference Bindoff, Stocker, Qin, Plattner, Tignor, Allen, Boschung, Nauels, Xia, Bex and Midgley2013; GISTEMP Team, 2016). Due to the temperature-related fractionation in the formation of carbonates (Kim & O'Neil, Reference Kim and O'Neil1997) (![]() $-0.2\permil \ \delta ^{18}$O per °C) and strong correlation in the extra-tropics between temperature and δ 18O (between 0.4 and 0.7‰ per °C) (and ~8× as sensitive for deuterium isotopes relative to hydrogen (δD)), we expect this temperature rise to be detectable in surface ocean carbonates (notably foraminifera), organic biomarkers, cave records (stalactites), lake ostracods and high-latitude ice cores, though only the first two of these will be retrievable in the timescales considered here.

$-0.2\permil \ \delta ^{18}$O per °C) and strong correlation in the extra-tropics between temperature and δ 18O (between 0.4 and 0.7‰ per °C) (and ~8× as sensitive for deuterium isotopes relative to hydrogen (δD)), we expect this temperature rise to be detectable in surface ocean carbonates (notably foraminifera), organic biomarkers, cave records (stalactites), lake ostracods and high-latitude ice cores, though only the first two of these will be retrievable in the timescales considered here.

The combustion of fossil fuel, the invention of the Haber–Bosch process, the large-scale application of nitrogenous fertilizers and the enhanced nitrogen fixation associated with cultivated plants, have caused a profound impact on nitrogen cycling (Canfield et al., Reference Canfield, Glazer and Falkowski2010), such that δ 15N anomalies are already detectable in sediments remote from civilization (Holtgrieve et al., Reference Holtgrieve2011).

Sedimentological records

There are multiple causes of a greatly increased sediment flow in rivers and therefore in deposition in coastal environments. The advent of agriculture and associated deforestation have lead to large increases in soil erosion (Goudie, Reference Goudie2000; National Research Council, 2010). Furthermore, canalization of rivers (such as the Mississippi) have led to much greater oceanic deposition of sediment than would otherwise have occurred. This tendency is mitigated somewhat by concurrent increases in river dams which reduce sediment flow downstream. Additionally, increasing temperatures and atmospheric water vapour content have led to greater intensity of precipitation (Kunkel et al., Reference Kunkel2013) which, on its own, would also lead to greater erosion, at least regionally. Coastal erosion is also on the increase as a function of the rising sea level, and in polar regions is being enhanced by reductions in sea ice and thawing permafrost (Overeem et al., Reference Overeem2011).

In addition to changes in the flux of sediment from land to ocean, the composition of the sediment will also change. Due to the increased dissolution of CO2 in the ocean as a function of anthropogenic CO2 emissions, the upper ocean is acidifying (a 26% increase in H+ or 0.1 pH decrease since the 19th century) (Orr et al., Reference Orr2005). This will lead to an increase in CaCO3 dissolution within the sediment that will last until the ocean can neutralize the increase. There will also be important changes in mineralogy (Zalasiewicz et al., Reference Zalasiewicz, Kryza and Williams2013; Hazen et al., Reference Hazen2017). Increases in continental weathering are also likely to change ratios of strontium and osmium (e.g.87Sr/86Sr and 187Os/188Os ratios) (Jenkyns, Reference Jenkyns2010).

As discussed above, nitrogen load in rivers is increasing as a function of agricultural practices. This in turn is leading to more microbial activity in the coastal ocean which can deplete dissolved oxygen in the water column (Diaz & Rosenberg, Reference Diaz and Rosenberg2008), and recent syntheses suggests a global decline already of about 2% (Ito et al., Reference Ito2017; Schmidtko et al., Reference Schmidtko, Stramma and Visbeck2017). This in turn is leading to an expansion of the oxygen minimum zones, greater ocean anoxia and the creation of so-called ‘dead-zones’ (Breitburg et al., Reference Breitburg2018). Sediment within these areas will thus have greater organic content and less bioturbation (Tyrrell, Reference Tyrrell2011). The ultimate extent of these dead zones is unknown.

Furthermore, anthropogenic fluxes of lead, chromium, antimony, rhenium, platinum group metals, rare earths and gold, are now much larger than their natural sources (Sen & Peucker-Ehrenbrink, Reference Sen and Peucker-Ehrenbrink2012; Gałuszka et al., Reference Gałuszka, Migaszewski and Zalasiewicz2013), implying that there will be a spike in fluxes in these metals in river outflow and hence higher concentrations in coastal sediments.

Faunal radiation and extinctions

The last few centuries have seen significant changes in the abundance and spread of small animals, particularly rats, mice and cats, etc. that are associated with human exploration and biotic exchanges. Isolated populations almost everywhere have now been superseded in many respects by these invasive species. The fossil record will likely indicate a large faunal radiation of these indicator species at this point. Concurrently, many other species have already, or are likely to become, extinct, and their disappearance from the fossil record will be noticeable. Given the perspective from many million years ahead, large mammal extinctions that occurred at the end of the last ice age will also associated with the onset of the Anthropocene.

Non-naturally occurring synthetics

There are many chemicals that have been (or were) manufactured industrially that for various reasons can spread and persist in the environment for a long time (Bernhardt et al., Reference Bernhardt, Rosi and Gessner2017). Most notably, persistent organic pollutants (organic molecules that are resistant to degradation by chemical, photo-chemical or biological processes), are known to have spread across the world (even to otherwise pristine environments) (Beyer et al., Reference Beyer2000). Their persistence is often tied to being halogenated organics since the bond strength of C–Cl (for instance) is much stronger than C–C. For instance, polychlorinated biphenyls are known to have lifetimes of many hundreds of years in river sediment (Bopp, Reference Bopp1979). How long a detectable signal would persist in ocean sediment is, however, unclear.

Other chlorinated compounds may also have the potential for long-term preservation, specifically CFCs and related compounds. While there are natural sources for the most stable compound (CF4), there are only anthropogenic sources for C2F6 and SF6, the next most stable compounds. In the atmosphere, their sink via photolytic destruction in the stratosphere limits their lifetimes to a few thousand years (Ravishankara et al., Reference Ravishankara1993). The compounds do dissolve in the the ocean and can be used as tracers of ocean circulation, but we are unaware of studies indicating how long these chemicals might survive and/or be detectable in ocean sediment given some limited evidence for microbial degradation in anaerobic environments (Denovan & Strand, Reference Denovan and Strand1992).

Other classes of synthetic biomarkers may also persist in sediments. For instance, steroids, leaf waxes, alkenones and lipids can be preserved in sediment for many millions of years (i.e. Pagani et al., Reference Pagani2006). What might distinguish naturally occurring biomarkers from synthetics might be the chirality of the molecules. Most total synthesis pathways do not discriminate between D- and L-chirality, while biological processes are almost exclusively monochiral (Meierhenrich, Reference Meierhenrich2008) (for instance, naturally occurring amino acids are all L-forms, and almost all sugars are D-forms). Synthetic steroids that do not have natural counterparts are also now ubiquitous in water bodies.

Plastics

Since 1950, there has been a huge increase in plastics being delivered into the ocean (Moore, Reference Moore2008; Eriksen et al., Reference Eriksen2014). Although many common forms of plastic (such as polyethylene and polypropylene) are buoyant in sea water, and even those that are nominally heavier than water may be incorporated into flotsam that remains at the surface, it is already clear that mechanical erosional processes will lead to the production of large amounts of plastic micro- and nano-particles (Cozar et al., Reference Cozar2014; Andrady, Reference Andrady2015). Surveys have shown increasing amounts of plastic ‘marine litter’ on the seafloor from coastal areas to deep basins and the Arctic (Pham et al., Reference Pham2014; Tekman et al., Reference Tekman, Krumpen and Bergmann2017). On beaches, novel aggregates ‘plastiglomerates’ have been found where plastic-containing debris comes into contact with high temperatures (Corcoran et al., Reference Corcoran, Moore and Jazvac2014).

The degradation of plastics is mostly by solar ultraviolet radiation and in the oceans occurs mostly in the photic zone (Andrady, Reference Andrady2015) and is notably temperature dependent (Andrady et al., Reference Andrady1998) (other mechanisms such as thermo-oxidation or hydrolysis do not readily occur in the ocean). The densification of small plastic particles by fouling organisms, ingestion and incorporation into organic ‘rains’ that sink to the sea floor is an effective delivery mechanism to the seafloor, leading to increasing accumulation in ocean sediment where degradation rates are much slower (Andrady, Reference Andrady2015). Once in the sediment, microbial activity is a possible degradation pathway (Shah et al., Reference Shah2008) but rates are sensitive to oxygen availability and suitable microbial communities.

As above, the ultimate long-term fate of these plastics in sediment is unclear, but the potential for very long-term persistence and detectability is high.

Transuranic elements

Many radioactive isotopes that are related to anthropogenic fission or nuclear arms, have half-lives that are long, but not long enough to be relevant here. However, there are two isotopes that are potentially long-lived enough. Specifically, Plutonium-244 (half-life 80.8 million years) and Curium-247 (half-life 15 million years) would be detectable for a large fraction of the relevant time period if they were deposited in sufficient quantities, say, as a result of a nuclear weapon exchange. There are no known natural sources of 244Pu outside of supernovae.

Attempts have been made to detect primordial 244Pu on Earth with mixed success (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman1971; Lachner et al., Reference Lachner2012), indicating the rate of actinide meteorite accretion is small enough (Wallner et al., Reference Wallner2015) for this to be a valid marker in the event of a sufficiently large nuclear exchange. Similarly, 247Cm is present in nuclear fuel waste and as a consequence of a nuclear explosion.

Anomalous isotopic ratios in elements with long-lived radioactive isotopes are also possible signatures, for instance, lower than usual 235U ratios, and the presence of expected daughter products, in uranium ores in the Franceville Basin in the Gabon have been traced to naturally occurring nuclear fission in oxygenated, hydrated rocks ~2 Ga (Gauthier-Lafaye et al., Reference Gauthier-Lafaye, Holliger and Blanc1996).

Summary

The Anthropocene layer in ocean sediment will be abrupt and multi-variate, consisting of seemingly concurrent-specific peaks in multiple geochemical proxies, biomarkers, elemental composition and mineralogy. It will likely demarcate a clear transition of faunal taxa prior to the event compared with afterwards. Most of the individual markers will not be unique in the context of Earth history as we demonstrate below, but the combination of tracers may be. However, we speculate that some specific tracers that would be unique, specifically persistent synthetic molecules, plastics and (potentially) very long-lived radioactive fallout in the event of nuclear catastrophe. Absent those markers, the uniqueness of the event may well be seen in the multitude of relatively independent fingerprints as opposed to a coherent set of changes associated with a single geophysical cause.

Abrupt paleozoic, mesozoic and cenozoic events

The summary for the Anthropocene fingerprint above suggests that similarities might be found in (geologically) abrupt events with a multi-variate signature. In this section, we review a partial selection of known events in the paleo-record that have some similarities to the hypothesized eventual anthropogenic signature. The clearest class of event with such similarities are the hyperthermals, most notably the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (56 Ma) (McInerney & Wing, Reference McInerney and Wing2011), but this also includes smaller hyperthermal events, ocean anoxic events in the Cretaceous and Jurassic and significant (if less well characterized) events of the Paleozoic. We do not consider of events (such as the K–T extinction event or the Eocene–Oligocene boundary) where there are very clear and distinct causes (asteroid impact combined with massive volcanism(Vellekoop et al., Reference Vellekoop2014), and the onset of Antarctic glaciation(Zachos et al., Reference Zachos2001) (likely linked to the opening of Drake Passage Cristini et al., Reference Cristini2012, respectively). There may be more such events in the record but that are not included here simply because they may not have been examined in detail, particularly in the pre-Cenozoic.

The Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum (PETM)

The existence of an abrupt spike in carbon and oxygen isotopes near the Paleocene/Eocene transition (56 Ma) was first noted by Kennett & Stott (Reference Kennett and Stott1991) and demonstrated to be global by Koch et al. (Reference Koch, Zachos and Gingerich1992). Since then, more detailed and high-resolution analyses on land and in the ocean have revealed a fascinating sequence of events lasting 100–200 kyr and involving a rapid input (in perhaps <5 kyr Kirtland Turner et al., Reference Kirtland Turner2017) of exogenous carbon into the system (see review by McInerney & Wing, Reference McInerney and Wing2011), possibly related to the intrusion of the North American Igneous Province into organic sediments (Storey et al., Reference Storey, Duncan and Swisher2007). Temperatures rose 5–7°C (derived from multiple proxies Tripati & Elderfield, Reference Tripati and Elderfield2004), and there was a negative spike in carbon isotopes (>3‰), and decreased ocean carbonate preservation in the upper ocean. There was an increase in kaolinite (clay) in many sediments (Schmitz et al., Reference Schmitz, Pujalte and Nú nez-Betelu2001), indicating greater erosion, though evidence for a global increase is mixed. During the PETM 30–50% of benthic foraminiferal taxa became extinct, and it marked the time of an important mammalian (Aubry et al., Reference Aubry, Lucas and Berggren1998) and lizard (Smith, Reference Smith2009) expansion across North America. Additionally, many metal abundances (including V, Zn, Mo, Cr) spiked during the event (Soliman et al., Reference Soliman2011).

Eocene events

In the 6 million years following the PETM, there are a number of smaller, though qualitatively similar, hyperthermal events seen in the record (Slotnick et al., Reference Slotnick2012). Notably, the Eocene Thermal Maximum 2 event (ETM-2), and at least four other peaks are characterized by significant negative carbon isotope excursions, warming and relatively high sedimentation rates driven by increases in terrigenous input (D'Onofrio et al., Reference D'Onofrio2016). Arctic conditions during ETM-2 show evidence of warming, lower salinity and greater anoxia (Sluijs et al., Reference Sluijs2009). Collectively these events have been denoted Eocene Layers of Mysterious Origin (ELMOs)Footnote 2.

Around 40 Ma, another abrupt warming event occurs (the mid-Eocene Climate Optimum (MECO)), again with an accompanying carbon isotope anomaly (Galazzo et al., Reference Galazzo2014).

Cretaceous and Jurassic ocean anoxic events

First identified by Schlanger & Jenkyns (Reference Schlanger and Jenkyns1976), ocean anoxic events (OAEs), identified by periods of greatly increased organic carbon deposition and laminated black shale deposits, are times when significant portions of the ocean (either regionally or globally) became depleted in dissolved oxygen, greatly reducing aerobic bacterial activity. There is partial (though not ubiquitous) evidence during the larger OAEs for euxinia (when the ocean column becomes filled with hydrogen sulfide (H2S)) (Meyer & Kump, Reference Meyer and Kump2008).

There were three major OAEs in the Cretaceous, the Weissert event (132 Ma) (Erba et al., Reference Erba, Bartolini and Larson2004), OAE-1a around 120 Ma lasting about 1 Myr and another OAE-2 around 93 Ma lasting around 0.8 Myr (Kerr, Reference Kerr1998; Li et al., Reference Li2008; Malinverno et al., Reference Malinverno, Erba and Herbert2010; Li et al., Reference Li2017). At least four other minor episodes of organic black shale production are noted in the Cretaceous (the Faraoni event, OAE-1b, 1d and OAE-3) but seem to be restricted to the proto-Atlantic region (Takashima et al., Reference Takashima2006; Jenkyns, Reference Jenkyns2010). At least one similar event occurred in the Jurassic (183 Ma) (Pearce et al., Reference Pearce2008).

The sequence of events during these events have two distinct fingerprints possibly associated with the two differing theoretical mechanisms for the events. For example, during OAE-1b, there is evidence of strong stratification and a stagnant deep ocean, while for OAE-2, the evidence suggests an decrease in stratification, increased upper ocean productivity and an expansion of the oxygen minimum zones (Takashima et al., Reference Takashima2006).

At the onset of the events (Fig. 1(c)), there is often a significant negative excursion in δ 13C (as in the PETM), followed by a positive recovery during the events themselves as the burial of (light) organic carbon increased and compensated for the initial release (Jenkyns, Reference Jenkyns2010; Kuhnt et al., Reference Kuhnt, Holbourn and Moullade2011; Mutterlose et al., Reference Mutterlose2014; Naafs et al., Reference Naafs2016). Causes have been linked to the crustal formation/tectonic activity and enhanced CO2 (or possibly CH4) release, causing global warmth (Jenkyns, Reference Jenkyns2010). Increased seawater values of 87Sr/86Sr and 187Os/188Os suggest increased runoff, greater nutrient supply and consequently higher upper ocean productivity (Jones, Reference Jones2001). Possible hiatuses in some OAE 1a sections are suggestive of an upper ocean dissolution event (Bottini et al., Reference Bottini2015).

Other important shifts in geochemical tracers during the OAEs include much lower nitrogen isotope ratios (δ 15N), increases in metal concentrations (including As, Bi, Cd, Co, Cr, Ni, V) (Jenkyns, Reference Jenkyns2010). Positive shifts in sulphur isotopes are seen in most OAEs, with a curious exception in OAE-1a where the shift is negative (Turchyn et al., Reference Turchyn2009).

Early Mesozoic and Late Paleozoic events

Starting from the Devonian period, there have been several major abrupt events registered in terrestrial sections. The sequences of changes and the comprehensiveness of geochemical analyses are less well known than for later events, partly due to the lack of existing ocean sediment, but these have been identified in multiple locations and are presumed to be global in extent.

The Late Devonian extinction around 380–360 Ma, was one of the big five mass extinctions. It is associated with black shales and ocean anoxia (Algeo & Scheckler, Reference Algeo and Scheckler1998), stretching from the Kellwasser events (~378 Ma) to the Hangenberg event at the Devonian–Carboniferous boundary (359 Ma) (Brezinski et al., Reference Brezinski2009; Vleeschouwer et al., Reference Vleeschouwer2013).

In the late Carboniferous, around 305 Ma the Pangaean tropical rainforests collapsed (Sahney et al., Reference Sahney, Benton and Falcon-Lang2010). This was associated with a shift towards drier and cooler climate, and possibly a reduction in atmospheric oxygen, leading to extinctions of some mega-fauna.

Lastly, the end-Permian extinction event (252 Ma) lasted about 60 kyr was accompanied by an initial decrease in carbon isotopes (− 5–7‰), significant global warming and extensive deforestation and wildfires (Krull & Retallack, Reference Krull and Retallack2000; Shen et al., Reference Shen2011; Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Bowring and zhong Shen2014) associated with widespread ocean anoxia and euxinia (Wignall & Twitchett, Reference Wignall and Twitchett1996). Pre-event spikes in nickel (Ni) have also been reported (Rothman et al., Reference Rothman2014).

Discussion and testable hypotheses

There are undoubted similarities between previous abrupt events in the geological record and the likely Anthropocene signature in the geological record to come. Negative, abrupt δ 13C excursions, warmings and disruptions of the nitrogen cycle are ubiquitous. More complex changes in biota, sedimentation and mineralogy are also common. Specifically, compared with the hypothesized Anthropocene signature, almost all changes found so far for the PETM are of the same sign and comparable magnitude. Some similarities would be expected if the main effect during any event was a significant global warming, however caused. Furthermore, there is evidence at many of these events that warming was driven by a massive input of exogeneous (biogenic) carbon, either as CO2 or CH4. At least since the Carboniferous (300–350 Ma), there has been sufficient fossil carbon to fuel an industrial civilization comparable with our own and any of these sources could provide the light carbon input. However, in many cases this input is contemporaneous to significant episodes of tectonic and/or volcanic activity, for instance, the coincidence of crustal formation events with the climate changes suggest that the intrusion of basaltic magmas into organic-rich shales and/or petroleum-bearing evaporites (Storey et al., Reference Storey, Duncan and Swisher2007; Svensen et al., Reference Svensen2009; Kravchinsky, Reference Kravchinsky2012) may have released large quantities of CO2 or CH4 to the atmosphere. Impacts to warming and/or carbon influx (such as increased runoff, erosion, etc.) appear to be qualitatively similar whenever in the geological period they occur. These changes are thus not sufficient evidence for prior industrial civilizations.

Current changes appear to be significantly faster than the paleoclimatic events (Fig. 1), but this may be partly due to limitations of chronology in the geological record. Attempts to time the length of prior events have used constant sedimentation estimates, or constant-flux markers (e.g.3He McGee & Mukhopadhyay, Reference McGee and Mukhopadhyay2012), or orbital chronologies, or supposed annual or seasonal banding in the sediment (Wright & Schaller, Reference Wright and Schaller2013). The accuracy of these methods suffer when there are large changes in sedimentation or hiatuses across these events (which is common), or rely on the imperfect identification of regularities with specific astronomical features (Pearson & Nicholas, Reference Pearson and Nicholas2014; Pearson & Thomas, Reference Pearson and Thomas2015). Additionally, bioturbation will often smooth an abrupt event even in a perfectly preserved sedimentary setting. Thus, the ability to detect an event onset of a few centuries (or less) in the record is questionable, and so direct isolation of an industrial cause based only on apparent timing is also not conclusive.

The specific markers of human industrial activity discussed above (plastics, synthetic pollutants, increased metal concentrations, etc.) are however a consequence of the specific path human society and technology has taken, and the generality of that pathway for other industrial species is totally unknown. Large-scale energy harnessing is potentially a more universal indicator, and given the large energy density in carbon-based fossil fuel, one might postulate that a light δ 13C signal might be a common signal. Conceivably, solar, hydro or geothermal energy sources could have been tapped preferentially, and that would greatly reduce any geological footprint (as it would ours). However, any large release of biogenic carbon whether from methane hydrate pools or volcanic intrusions into organic-rich sediments, will have a similar signal. We therefore have a situation where the known unique markers might not be indicative, while the (perhaps) more expected markers are not sufficient.

We are aware that raising the possibility of a prior industrial civilization as a driver for events in the geological record might lead to rather unconstrained speculation. One would be able to fit any observations to an imagined civilization in ways that would be basically unfalsifiable. Thus, care must be taken not to postulate such a cause until actually positive evidence is available. The Silurian hypothesis cannot be regarded as likely merely because no other valid idea presents itself.

We nonetheless find the above analyses intriguing enough to motivate some additional research. Firstly, despite copious existing work on the likely Anthropocene signature, we recommend further synthesis and study on the persistence of uniquely industrial byproducts in ocean sediment environments. Are there other classes of compounds that will leave unique traces in the sediment geochemistry on multi-million year timescales? In particular, will the byproducts of common plastics, or organic long-chain synthetics, be detectable?

Secondly, and this is indeed more speculative, we propose that a deeper exploration of elemental and compositional anomalies in extant sediments spanning previous events be performed (although we expect that far more information has been obtained about these sections than has been referenced here). Oddities in these sections have been looked for previously as potential signals of impact events (successfully for the K–T boundary event, not so for any of the events mentioned above), ranging from iridium layers, shocked quartz, micro-tectites, magnetites, etc. But it may be that a new search and new analyses with the Silurian hypothesis in mind might reveal more. Anomalous behaviour in the past might be more clearly detectable in proxies normalized by weathering fluxes or other constant flux proxies in order to highlight times when productivity or metal production might have been artificially enhanced. Thirdly, should any unexplained anomalies be found, the question of whether there are candidate species in the fossil record may become more relevant, as might questions about their ultimate fate.

An intriguing hypothesis presents itself should any of the initial releases of light carbon described above indeed be related to a prior industrial civilization. As discussed in the section ‘Cretaceous and Jurassic ocean anoxic events’, these releases often triggered episodes of ocean anoxia (via increased nutrient supply) causing a massive burial of organic matter, which eventually became source strata for further fossil fuels. Thus, the prior industrial activity would have actually given rise to the potential for future industry via their own demise. Large-scale anoxia, in effect, might provide a self-limiting but self-perpetuating feedback of industry on the planet. Alternatively, it may be just be a part of a long-term episodic natural carbon cycle feedback on tectonically active planets.

Perhaps unusually, the authors of this paper are not convinced of the correctness of their proposed hypothesis. Were it to be true it would have profound implications and not just for astrobiology. However, most readers do not need to be told that it is always a bad idea to decide on the truth or falsity of an idea based on the consequences of it being true. While we strongly doubt that any previous industrial civilization existed before our own, asking the question in a formal way that articulates explicitly what evidence for such a civilization might look like raises its own useful questions related both to astrobiology and to Anthropocene studies. Thus, we hope that this paper will serve as motivation to improve the constraints on the hypothesis so that in future we may be better placed to answer our title question.

Acknowledgments

No funding has been provided nor sought for this study. We thank Susan Kidwell for being generous with her time and helpful discussions, David Naafs and Stuart Robinson for help and pointers to data for OAE1a and Chris Reinhard for his thoughtful review. The GISTEMP data in Fig. 1(a) were from https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp (accessed Jul 15 2017).