Studies of Middle Eastern urbanism have traditionally been guided by a limited repertoire of tropes, many of which emphasize antiquity, confinement, and religiosity. Notions of the old city, the walled city,Footnote 1 the casbah, the native quarter, and the medina,Footnote 2 sometimes subsumed in the quintessential “Islamic city,”Footnote 3 have all been part of Western scholarship's long-standing fascination with the region. Etched in emblematic “holy cities” like Jerusalem, Mecca, or Najaf, Middle Eastern urban space is heavily associated with the “sacred,”Footnote 4 complete with mystical visions and assumptions of violent eschatologies and redemption.

These depictions, like all tropes, are analytically impounding. Accentuating authenticity and a concomitant cultural autochthony, their vividness breeds essentialization and theoretical impasse. Often obscured by idioms such as “stagnation,” “traditionalism,” and “backwardness,”Footnote 5 Middle Eastern cities thus tend to have their emergent urban configurations obfuscated and misrecognized.

Responding to this Orientalist bias, students of Middle Eastern urbanism began in the 1970s framing Middle Eastern cities as instances of Third World urbanization.Footnote 6 This comparative perspective productively subverted the myth of the Islamic, Oriental city.Footnote 7 Instead it focused on the colonial and postcolonial city as a site of class struggle, urban apartheid, imperial planning, and colonial architecture.

This revisionist framework in turn yielded three paradigmatic idioms: the colonial city (e.g., Algiers under French rule), the dual city (e.g., Rabat under post-Moroccan independence), and the divided city (e.g., Jerusalem since 1967).Footnote 8 Stressing political economy, governmentality,Footnote 9 and urban inequalities under colonialism and, recently, neocolonialism,Footnote 10 these idioms have their own myopic limitations—primarily their tendency to misrecognize intercommunal dynamics and to underestimate social networking across ethnic divides. Highlighting exclusion, disenfranchisement, and marginality, they are often oblivious to professional collaboration, residential mix, and other factors that nourish and vitalize plural urban societies.

This article, which focuses on ethnically mixed townsFootnote 11 in Ottoman and Mandatory Palestine and, later, in Israel, wishes to avoid the restrictive tropes of urban Orientalism and Manichean conceptualizations of the colonial and dual city. Defying such binary oppositions, we argue that these towns manifest powerful nationalist and persistent colonial segregation while actively resisting them. By scrutinizing demographic diversification, geographical and cultural expansion, intercommunal relations, and, not least, the secularizing and nationalizing effect urban centers have had on the Middle East since the 19th century, our analysis reconfigures the sociopolitical history of this city form. Like scholars of the urban informed by postcolonial theory, notably Anthony King and Jane Jacobs, we recognize how ethnic segregation does not rule out cohabitation and how the dialectics of oppression and resistance are often intertwined.Footnote 12 This leads us to argue that mixed towns in Palestine/Israel are best characterized as emergent constellations, that is to say, historically specific superpositions of earlier urban forms. Rather than treating them as essentialized primordial entities, we see them, following Nezar al-Sayyad, as unfolding manifestations of “hybrid urbanism”Footnote 13—an idiom resonating with imageries of mimicry, unconscious infatuation, and tense cross-references between colonizer and colonized, as developed within postcolonial theory.

In light of this interpretive paradigm, a revisionist conceptualization of the urban colonial encounter makes visible, as Albert Memmi has noted, the dialectic “enchaînement” between colonizer and colonized that produces in the process multiple intentionalities, identifications, and alienations.Footnote 14 The urban colonial frontier thus emerges not as a site of unidirectional zero-sum conflict but rather as “a place in which the unfolding sociolegal and political histories” of both dominators and dominated, and center and periphery “met—there to be made, reciprocally, in relation to each other.”Footnote 15 Beyond and beneath colonialism's black-and-white dualisms and powerful “working essentialisms,” “visible differences in the master class did create an awareness of ruptures and incoherences in European control; ruptures at which local resistance was directed, and in which new hybridities could take root.”Footnote 16 Similarly, from this perspective, the city can be viewed not as a container of ethnic “communities” but as a site of production, mediation, and transaction—a locus of dialectic relationship between form, function, and structureFootnote 17—in which social processes and urban “things” get intertwined.Footnote 18 The same reconceptualization applies for urban space and minority/majority relations among ethnic groups in Palestine/Israel as well as for the national and local identities they produce.

Modern urban spaces are, by definition, mixed sociospatial configurations. Their unprecedented success and vitality lie in the richness of their ethnic texture and ongoing exchange of economic goods, cultural practices, political ideas, and social movements.Footnote 19 Variety, however, rarely spells harmony, and urban mix has often led to violent conflict over land and identity. As urban theorists consistently stress, urbanization inherently involves the differential production of marginalized groups, cultural alterities, class subordination, and racial segregation.Footnote 20 The modern city as we know it is also an agonistic, dynamic combination of confluence, diversity, and conflict. As Simmel's classical analysis of the mental life of the metropolis suggests, urban complexity is often played out as individuality and subjective freedom poised against estrangement and subordination to “objective culture.”Footnote 21

A second seminal component of modern urban life is its linkage to the concept of the nation. Modern nations, in Europe and elsewhere, may have invented themselves through idealized, nostalgic imaginations of rural heritage and earthy effigies of ancient peasantry.Footnote 22 Their feet, however, have always been firmly grounded in the political, economic, and cultural theater of the modern city. Their potency has always drawn on the exuberant supply of human energy, material resources, and political momentum provided by the city.Footnote 23

The 19th and 20th centuries, which saw an exponential growth in the number of urban centers, their sizes, and general salience for humanity, witnessed a particularly significant role for what we now know as capital cities. Some capitals have, of course, transcended nations, serving as metropolitan hubs for world-encompassing colonial projects.Footnote 24 On the whole, however, the political, cultural, and economic centrality of national hubs was closely linked to their symbolic roles as emblems of the nation's future. Capitals, in other words, became urban embodiments of the human confluence and ever-growing popularity of the notion of the nation.Footnote 25

The salience of capital cities notwithstanding, this article wishes to avoid a metropolitan bias. It focuses on the role of lesser towns as nodes of urban life where demographic growth and ethnonational assertion feed on each other. Some of the towns we look at are old; most of them are predominantly modern. Some are or have been until quite recently confined within a walled compound; a few of them, however, retain the cultural, social, and political tenor that ostensibly comes with this enclosure. Some carry religious loads, but none has its contemporary identity shaped by religious “holiness.” Also, none is a capital city in the formal, modernist sense of the term.Footnote 26

Our analysis, in other words, enjoys a degree of theoretical freedom, which enables new theorization of the significant relationship among modernity, the concept of the nation, and urbanity. This trajectory, we believe, is particularly well served by an informed, historicized analysis of the urban chronology of mixed Arab and Jewish spaces in Palestine, and later Israel, in the 19th and 20th centuries. The urban foci in this territory, which displayed unmistakable signs of modernization already under late Ottoman rule,Footnote 27 saw the concept of the nation assuming a central sociopolitical role in the first half of the 20th century, soon becoming a major factor in the tumultuous events that unfolded in subsequent decades.

The classic variant of European nationalism, with single nations embodied in unitary projects claiming sovereignty over specific bounded territories, often hinged on the invention, construction, and transformation of the social group that would eventually become identified as “the nation.”Footnote 28 With homogeneity taken for granted, the notion of the nation was potent enough to iron out differences, producing coherent tapestries with which most members could identify.

Unlike the European variant, Palestine was host to two competing national projects—a local Palestinian Arab project and a colonizing Jewish-Zionist one. Both projects were equipped with coherent narratives of history and of entitlement: the Palestinians stressed native indigenous rights whereas the Zionists emphasized primordial biblical promise and redemption from a dangerous diaspora in Europe. It is not surprising that this soon had the two projects locked in a struggle that protagonists on both sides still see as a zero-sum game for supremacy and bare survival. The way this bifurcation played out on the urban scene merits further analytical scrutiny.

The territorial logic of the nation hinges on clear-cut definitions and discrete boundaries.Footnote 29 The Israeli–Arab conflict, however, with its intense focus on territory, has always had respective sides attempting to gain maximum control of as much land occupied by as few members of the other as possible. It is an imperative that many on both sides still regard as a sacred duty.

Within this context, proactive Zionist settlement in and near existing Arab urban centers produced a pattern of territorial and residential mix that became a major component of pre-1948 Palestine. One result was that the same segments of urban space were often seen by actors on both sides of the ethnonational divide as empty and available. A fascinating array of contradictions, overlaps, collusions, protrusions, and, at times, mimicry and cooperation thus developed.

The unbounded sense of territorial availability and historical entitlement on both sides of the divide pushed Jewish and Palestinian urbanites to interact in a varied web of relations. This includes, on the one hand, land purchase, dispossession, and territorial feuds and, on the other hand, commercial partnerships, class-based coalitions, residential mix, and municipal cooperation. The two groups and their identities, in other words, were and still are constituted through an array of dialectic oppositions. Historically and analytically, the Palestinian and the Jewish entities oppose each other but at the same time create each other in asymmetrical relations of power.Footnote 30

Mixed urban space in Palestine and, later, Israel thus emerged as a border zone where politically constructed ethnoterritorial rival groups compete but also where individuals and institutions on either side often cooperate, seeking personal gain, communal persistence, and resistance against colonial and state power. This twilight area is the theoretical and analytical territory that we explore.

As different from the classic 19th-century European case as Palestine may have been, taken in a global historical analytical perspective, it is by no means singular. In the post-World War II era, as European empires were dissolving, many decolonizing territories in Africa, the Americas, and Southeast Asia had two or more ethnoterritorial groups vying for control of rural terrain, urban spaces, and, most importantly, political and economic dominance in the emerging state.Footnote 31 In most bifurcated (or multifactioned) states, one of the competing groups ended up in power then proceeded to operate the state as if it were the perfect personification of a “united nation,” hoping to maintain an acceptable level of unity and peace.Footnote 32 Yet many of these territories are still haunted by the bloody consequences of these old divisions.

“MIXED TOWNS”: A POLITICAL ETYMOLOGY

We propose a two-pronged definition of mixed town. One element is simply a sociodemographic reality: a certain ethnic mix in housing zones, ongoing neighborly relations, socioeconomic proximity, and various modes of joint sociality. The second element is discursive, namely, a consciousness of proximity whereby individuals and groups on both sides actually share elements of identity, symbolic traits, and cultural markers, signifying the mixed town as a locus of joint memory, affiliation, and self-identification. This, we believe, is what distinguishes a “mixed” town (like Haifa in the 1930s) from a “divided” one (like post-1967 Jerusalem).

Superimposed on the history of modern urbanism in Palestine and, later, Israel, this working definition informs a diachronic typology (following) of mixed towns and of the spatial realities they engendered. This historicization helps contextualize particular cases of urban interaction within contemporary social science and historical literature.

The term mixed towns has had a checkered history in Palestine/Israel.Footnote 33 It was and still is used by Israelis and Palestinians in diverse historical and political contexts, serving a number of discursive goals. The first mention of the concept appears in the Peel Commission Report (1937), following the breakout of the “Arab Revolt” (1936–39). The report puts forth the first plan for territorial partition between Jews and Arabs as a fair compromise and possible resolution of the escalating national conflict. For the mixed towns of Tiberias, Safad, Haifa, and Acre, however, the commission stresses that absolute separation cannot be realistically expected. In order to guarantee the protection of minorities in these towns, the report suggests keeping these towns under “Mandatory administration” even after the partition plan is under way.

A survey of two main Hebrew and Arabic newspapers from the early 1940s to date indicates that next to utilize the term were Labor Zionist spokesmen. The earliest mention of the Hebrew term is in an article published in 1943 in Yedioth Aharonot.Footnote 34 The article quotes Aba Hushi, a prominent Zionist Labor politician who later became Haifa's longest-standing mayor. Hushi comments on the “unique circumstances” of Haifa as “a mixed town” (˓irme ˓orevet), a situation he obviously saw as a challenge to the Histadrut, the Zionist trade union federation of which he was the local leader. The task of the Histadrut, he says, is to “stand fast” and ensure that although Jews in Haifa are a minority, they will nevertheless get their share of employment in a labor market dominated by governmental, municipal, and industrial projects operated by transnational colonial corporations. His implication is clear: a “mixed town,” as opposed to “a Jewish town” like Tel-Aviv, is an impediment to proper protection of the interests of Jewish labor, which presumably would have been better served by an exclusively Jewish municipal administration.

The debate about mixed towns that took place in Jewish and Zionist leadership circles in the 1940s was later summarized in a 1953 article that examines whether Jaffa should have been defined as “a mixed town” in the 1940s.Footnote 35 As in Hushi's argument regarding Haifa, here, too, the term is coined in order to account for the peculiar situation of a Jewish minority population under Arab majority rule.

A survey of the Arabic daily Al-Ittihad from 1944 to date yields no mention whatsoever of “mixed towns.” Prior to 1948 and, even more significantly, since then, Jaffa, Haifa, Ramle, Lydda, and Acre are represented as strictly “Arab” towns. Palestinian recognition of the presence of Jews, and thus of the legitimate existence of de facto mixed towns, was simply absent before the 1990s.

The concept in its current Palestinian use evolved, it would appear, as the second generation of Palestinians born as Israeli citizens were seeking to define mixed towns vis-à-vis the state, the municipality, and other institutions such as the Supreme Monitoring Committee of Arabs in Israel.Footnote 36 This need was accentuated following the breakout of the second intifada in the occupied territories and the violent events of October 2000 inside Israel, some of which took place in mixed towns (Jaffa, Acre). These tumultuous events, in which many Palestinians felt that their personal security was breached, yielded an assertive position on mixed towns (mudun mukhtalaṭa). Resorting to the language of collective rights, this position, which has since gained some visibility in Palestinian public discourse within Israel, demands that Palestinian populations in mixed towns be represented in the Supreme Monitoring Committee of Arabs in Israel. It also calls to address the particular needs of their residents through negotiations and joint projects with Jewish-dominated local authorities and nongovermental organizations.Footnote 37

These sensibilities were brought to the attention of the Jewish public in Israel through increasing media coverage and public debate. A particularly visible example is a comprehensive series in Ha˒aretz, authored by Ori Nir and Lili Galili in late 2000, that looks at mixed towns in the wake of the October 2000 events. The debate about mixed towns, Nir and Galili argue, is important, as “mixed towns are a metaphor for the entire Israeli–Palestinian conflict.”Footnote 38 Fifty years after the establishment of the State of Israel and the destruction of important segments of Palestinian urbanism, Palestinian and Jewish-Israeli public discourses constitute mixed towns as a marked cultural and political category, deeply intertwined with the future of Israel and its Palestinian minority.

As indicated by our survey of Al-Ittihad, the discourse on mixed towns can be conducted not only positively, but also negatively, by denying its very existence. A certain Palestinian scholarly discourse rejects the characterization of such towns as mixed,Footnote 39 arguing that the idiom is nothing but a figment of Zionist ideologist imagination. In reality, this position claims, these towns are simply Jewish towns with marginalized and oppressed Arab communities.Footnote 40 Concomitantly, this critical view depicts the discourse of mixed towns as a neoliberal construction and prefers to label them either as “targeted towns” (mudun mustahdafa) or, in a slightly more optimistic vein, “shared towns” (mudun mushtaraka).Footnote 41

On the Jewish-Israeli side, discursive strategies reflect other forms of denial. Local leaders in mixed towns, such as Natzerat Illit in the 1980s, suppressed statistical data that indicated that their towns had any Palestinian component, let alone one meaningful enough to render it a mixed town.Footnote 42 Instead, official local publications pushed perceptions and representations of the town as exclusively Jewish and intensely Zionist.

This bifurcated discursive negation suggests that the concept of mixed towns underwent a structural inversion as the 20th century unfolded. Originally coined to describe the predicament of Jewish neighborhoods under Arab municipal dominance, it currently denotes the predicament of minority Palestinian communities in towns dominated by Jewish majorities and is sometimes obfuscated by Jewish urban politicians wishing to avoid what they see as a Palestinian stigma of their town. Moreover, whereas Palestinian narratives traditionally constructed Jaffa, Haifa, Ramle, Lydda, and Acre as an unmarked category (an “Arab town”),Footnote 43 thus symbolically erasing the presence of Jewish communities in their midst, the effects of the nakba and the Judaization of Palestinian urban space transformed these towns into a marked Palestinian category that demands cultural definition and political mobilization.

The unfolding vicissitude of the discourse on mixed towns encapsulates many of the pertinent issues in the history of 20th-century Jewish–Arab relations. This dialectic inversion corresponds to what Yuval Portugali has termed “implicate relations,”Footnote 44 denoting the similarities in form and content that exist between the two national projects. The urban landscape is as good a context as any to demonstrate how political, social, and philosophical sensibilities, as well as figments of collective memory, evolved in a process of dialectic opposition and reciprocal determination between the two communities.

THE HISTORY OF URBAN MIX IN PALESTINE

Taking the Ottoman conquest of 1517 as our point of departure, our typology identifies six chronological urban configurations, each of which evolved within the context of specific sociohistoric circumstances. The six configurations are as follows:

• the prenational, precapitalist Ottoman sectarian town (1517–1858)

• the protonational, mercantile mixed town (1830–1921)

• the bifurcated nationalizing mixed town (1917–48)

• the truncated town as war zone (1947–50)

• the depopulated colonized mixed town (1948 to date)

• the newly mixed town (1980s to date)

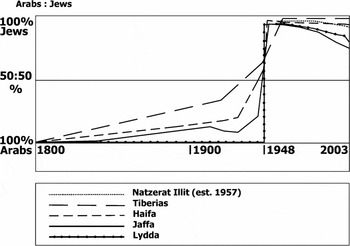

It is important to point out that interfaces between different configurations, although generally temporal, do not provide precise periodization with discrete cutoff points. Rather, this typology accentuates the dynamics that prevailed as each configuration of urban mix was gradually eclipsed by the next one. Particular cutoff points, as well as overlaps between the periods, are explicated in our more detailed account of these six configurations in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Demographic ratio (Arabs/Jews) in Selected Mixed Towns in Palestine/Israel, 1800–2003.

The Prenational, Precapitalist Ottoman Sectarian Town (1517–1858)

Urban spaces in the Ottoman Middle East during the early modern era were predicated on the logic of religious communalism.Footnote 45 Although some public spaces were ethnically neutral, residential patterns corresponded by and large to the administrative millet system of patronage and classification.Footnote 46 Early modern urbanism in Ottoman Palestine was no exception. Consisting of separate ethnic quarters that housed religiously defined communities regulated by imperial law,Footnote 47 it had cultural difference semiotically marked and socially recognized within the material and symbolic walls of the “old city.”Footnote 48 Using the religious idiom, so vividly inscribed by the Ottoman regime as the primary marker of community, we identify four towns in early Ottoman Palestine where Jews, Muslims, Christians, and other ethnoreligious communities coexisted in a regulated urban mix: Jerusalem, Tiberias, Hebron, and Safad.

Under Ottoman administration, these communities, which were vertically subordinate to regional Ottoman rulers and, through them, to the metropole in Istanbul, conducted their affairs largely independent of one another. People living in them had neither a common municipal organizational framework of which they were subjects nor a coherent concept of local identity as or affiliation with a unified body of local citizenry. This is understandable once we recall that this era had yet to see territorial nationalism as a defining element of identity and that communities of natives and immigrants alike were defined along ethnoreligious lines.

To anticipate a later theme, prenational, precapitalist Ottoman sectarian towns, robust as they may have been in early modern times, were about to be subverted and reconfigured by two related features of modernity poised to make their entry into Middle Eastern history: print capitalism and ethnonationalism.

The Protonational, Mercantile Mixed Town (1830–1921)

The second configuration of mixed urbanism in Palestine that we identify emerged in the 1830s as the prenationalist, precapitalist, community-based social order was gradually eclipsed by a capitalist colonial order ushered in by a new form of imperial rule.

The 1830s were a turbulent decade in North Africa and the Levant, producing considerable population movement, some of which was instigated by the Ottoman authorities. One result was the appearance in Jaffa of a first contingent of Jewish immigrants from the Maghrib, who formed the nucleus of a community that displayed consistent growth in subsequent decades.Footnote 49 However, Jaffa became attractive for others too. It attracted a steady influx of Palestinian Arabs from the town's rural hinterland and from territories farther afield and Christian and Jewish immigrants from the Mediterranean and southern European countries such as Greece and Turkey. This immigration soon spread to other coastal towns in Palestine, notably Haifa and Acre, triggering considerable growth of the urban component of Palestine's population and, concomitantly, an accelerated modernizing thrust.

The growth in Italy, France, Germany, and England of new markets for consumer goods, fueled by economic growth and newly acquired tastes in food and propelled by technological advances in marine transportation, triggered a dramatic rise in the export of agricultural produce through the ports of Palestine.Footnote 50 One result was a new dialectic between two foci of economic activity and political mobilization: the mercantile coastline towns of Jaffa, Haifa, and Acre, where growth was based on booming trade with Europe, and the semirural inland towns of Nablus, Hebron, Ramallah, and Nazareth,Footnote 51 where the economy was still a markedly localized one, with trade in staples for premodern tools being the (considerably slower) order of the day.Footnote 52 The period between 1880 and 1918, in which the average annual growth of the urban population of Palestine was 3 percent, saw a particularly dramatic expansion in the coastal towns. Haifa, which in the 1830s had been a fishing village with no more than 1,000 inhabitants, had three times this number by 1850 and over 20,000 in 1939. Jaffa, which in 1850 had a built-up area within its ancient walls of twenty-five acres and a population of 5,000, grew by 1939 to nearly 400 acres and 50,000 inhabitants.Footnote 53

Meanwhile, growing European interest in Palestine resulted in missionary outposts and a growing presence of European mercantile agents. Centered mainly in towns, missionary schools became key factors in the production of a new, predominantly Christian Palestinian middle class and elite.Footnote 54

Towns in Palestine that hitherto had not been significantly mixed, particularly Jaffa and Acre,Footnote 55 were now absorbing Jewish immigrants from various parts of the Mediterranean basin, not least the Balkans. The newcomers were involved in commerce, finance, fishing, and crafts—a stark opposition to the more traditional existence of Jews in the four premercantile Ottoman mixed towns characterized earlier.

From the 1860s onward, as security conditions in Palestine improved, new neighborhoods emerged outside the walls of Jerusalem, Jaffa, and later Haifa. This urban expansion often came at the expense of older quarters, which saw middle-class and poorer residents trading their dense residential units in the crowded alleys for more spacious domiciles outside the walls.Footnote 56

Jaffa, for example, reaped considerable benefit from the nearby establishment of an agricultural school in Mikve Yisrael in 1870. The school, along with the busy harbor, helped the town become the focal point of the growing Jewish community in Palestine. New Jewish neighborhoods were now established—Neve Tzedek in 1887 and Neve Shalom in 1885— signaling a colonizing effort that culminated in 1909 with Ahuzat Bait, the nucleus of what soon became the (exclusively Jewish) town of Tel-Aviv.Footnote 57

The expansion of new residential and commercial quarters beyond the old town walls was by no means an exclusively Jewish phenomenon. In the latter part of the 19th century Jaffa saw Muslim expansion north of the old town to what would become known as Manshiyya, and Christians colonized the area south of the town walls. Significantly, although the establishment of these new neighborhoods initially followed an ethnodenominational logic, they soon became spaces where all ethnicities mixed relatively freely. This point is illustrated lucidly by Bernstein's work on Manshiyya.Footnote 58

Haifa and West Jerusalem present further examples of this modernizing urban mix, in which Zionist influx in the 1890s and 1900s created new demand for residential properties and a concomitant desire to define new areas as not merely Jewish but also Zionist. Here again, however, projects that were initiated by a drive for ethnic separation sometimes ended up ethnically diverse. Haifa, which grew westward from the predominantly Muslim walled Ottoman town, is a good example of this diversification, with new Palestinian Christian clusters, a German Christian colony, a considerable Armenian presence, and more.

However, the dynamics that produced this ethnic mix were short-lived. Whereas the late 19th century saw the old millet-based correspondence between spatial boundaries and social grouping blurred, a new form of public space emerged that was exceedingly informed by a new national—rather than denominational—awareness. Ethnonational competition between Jews and Arabs was clearly feeding an exclusionary demand for spatial segregation. Before World War I, urbanism in Palestine was thus exhibiting patterns of modernization and spatial differentiation that clearly diverged from patterns that had guided the old sectarian Ottoman towns. Resonating with an ever-growing logic of nationalism, politicized urban space was about to assume a dramatic role under British rule.

On the eve of the British conquest in 1917 we can identify eight mixed towns in Palestine that broadly fall into the two categories reviewed so far. East Jerusalem, Hebron, Safad, and Tiberias had retained their prenational, sectarian Ottoman tenor; Haifa, Jaffa, Acre, and, to a lesser extent, West Jerusalem, showed clear features of mercantile, protonational urban nodes. We suggest 1921 as the date that marks the end of this interstitial epoch of transition. That year saw a watershed event in the urban history of Palestine, one that had far-reaching consequences for the wider ethnonational struggle. On 1 and 2 May, forty-three Jews, some of them residents of a hostel for new immigrants, were murdered by Palestinian militants in Jaffa.Footnote 59 The nationalizing wave that was about to sweep the country in the 20th century became dramatically violent. Significantly, the entry took place in the urban medium, now poised to form a prime arena for the Arab–Jewish national struggle.

It is interesting to note the fate that awaited the four prenational Ottoman sectarian mixed towns (East Jerusalem, Safad, Tiberias, and Hebron) when national tensions finally erupted into large-scale conflict in 1929, in 1936–38, and eventually in the all-out war of 1948. All four suffered cataclysmic, violent events that ultimately led to ethnic cleansing. Hebron's thriving Jewish community was forced to flee the town en masse in August 1929, following a Palestinian assault that left sixty-four men, women, and children dead. The Palestinian communities of Safad and Tiberias ceased to exist in April 1948, when Israeli forces took control and drove all Palestinians to Lebanon and Syria. The old Jewish quarter of Jerusalem was likewise abandoned in July 1948, when its entire Jewish population fled under pressure from Jordanian-army shelling as their hope of being joined by Israeli forces was fading.

This is not to suggest that the fate of Palestinians in Jaffa, Haifa, and Acre, the three towns that in the 19th century evolved into protonational, mercantile mixed towns, was idyllic. Most Palestinian residents suffered immeasurably in 1948, the majority becoming refugees. The truncation of the old Palestinian existence, however, was not as finite as the severing of the Palestinian communities of Safad and Tiberias or, for that matter, of the Jewish communities of Hebron and Old Jerusalem. More significantly, subsequent decades saw partial rehabilitation of Palestinian urbanity in the three protonational mercantile mixed towns, something that did not happen in Safad and Tiberias.

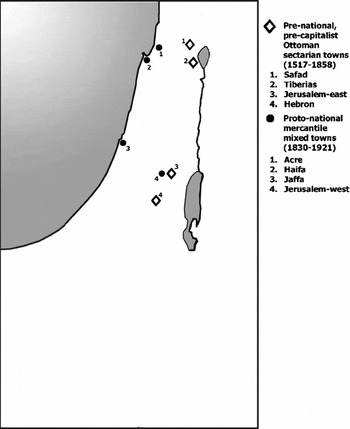

The map in Figure 2 does not present comprehensive citation of all mixed towns that existed in the relevant period. Rather, it captures analytically the emergence of new urban compositions, either in the form of newly established settlements (e.g., West Jerusalem) or in the form of transformation of an older urban model into a new one (e.g., Jaffa).

Figure 2 Prenational, precapitalist Ottoman sectarian towns (1517–1858), and protonational, mercantile mixed towns (1830–1921).

Bifurcated National Capitalist Mixed Towns (1917–48)

The third pattern of urban mix in Palestine began emerging following the 1917 Balfour Declaration and the start of “surrogate colonization” of Palestine by British forces and Jewish Zionist immigrants.Footnote 60 This period of escalating ethnoterritorial conflict saw explicit and conscious remodeling of urban space as nationalized place, to use De Certeau's idiom.Footnote 61 It was a time, however, in which national boundaries were paradoxically challenged by more cooperative sensibilities and practices. Intercommunal relations, trade activities, residential patterns, and social ties created a cognitive and interactional mixture whereby exclusionary nationalism, prenational community-based ties, and more recent ventures of Jewish–Arab economic and political collaboration were all at play at once.

The nexus between Jews and Palestinians in Jaffa and in Tel-Aviv is a good illustration of this dialectic.Footnote 62 Since its founding in 1909, Tel-Aviv had had a problematic and ambivalent relationship with Jaffa—its mother city turned rival. Like many cases of child–parent rivalry, this relationship focused on the complexities of separation and individuation.Footnote 63 Tel-Aviv, which started with Ahuzat Bait as Jaffa's “Jewish garden suburb,” was overshadowing Jaffa, economically and demographically, as early as the 1930s.Footnote 64 The power balance capsized in 1948, when Jaffa was conquered by Israeli forces and emptied of most of its Palestinian inhabitants. In the 1950s Jaffa was officially incorporated into the municipal jurisdiction of Tel-Aviv, a move that rendered it the chronically dilapidated south side of the “White City,” perpetuating an economic and political dependence on Tel-Aviv and a drastic cultural otherness from it.

The century-long relationship between Jaffa and Tel-Aviv thus reflects a tension between assimilation and distinction, and cultural integration and spatial separation—a dialectical conflict that shapes Jaffa's identity to date. It conflates social proximity and distance, political inclusion and exclusion, and ethnic mix and segregation.

The case of Jaffa and Tel-Aviv is metonymic of a wider, macronational order. Prior to 1948, both Jaffa and Tel-Aviv were perceived as the metropolitan embodiments of their respective national—although not religious or spiritual—geists. Tel-Aviv was mythicized in Zionist imagination as “the city that begat a state” (ha˓ir she-holida medina). Jaffa, dubbed in the Palestinian cannon as “the bride of Palestine” (˓arus Filasṭīn), emerged in Palestinian national imagination as the nation's cosmopolitan, modern, and secular outpost. The confrontation between the two towns thus became an existential battle between two national projects locked in a zero-sum game. The symbolic, discursive, and later physical erasure of the Palestinian hub became a precondition for the symbolic and material emergence of Jewish-Israeli Tel-Aviv.Footnote 65

The consolidation in the 1920s of Tel-Aviv's image as “the first Hebrew town” (ha˓ir ha˓ivrit harishona) encouraged the construction of new Jewish neighborhoods in other cities such as Hadar Hacarmel in Haifa and Rehavia in Jerusalem. Relations between Jewish and Arab residents varied widely, ranging from the 1929 pogrom in Hebron to what Goren describes as an equitable distribution of resources and balanced political system in the case of Haifa.Footnote 66

As indicated earlier, the towns of Palestine were a magnet for new waves of immigrants on both sides. Jewish immigration from Europe in the 1920s and 1930s was matched by large-scale labor migration from surrounding Arab territories in present-day Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, and beyond. Arab immigrants fed a new demand for residential construction, fueling planning and establishment of new neighborhoods in every major town, including Sheikh Jarah and Talbiye in Jerusalem, Wadi Nisnas and Halissa in Haifa, and King George Boulevard in Jaffa, to name but a few. It also had an impact on lesser towns like Ramle, Lydda, Acre, and Bi˒r al-Sab˓, where Palestinian civil society was steadily expanding. Newspapers were printed, and the economy, although obviously impacted by upheavals in Palestine and abroad, was growing.Footnote 67

Seven mixed towns were reconfigured during this transitional period, typified by budding modernization, economic growth, incoming migration, and a growing sense of national awareness.Footnote 68 Four were the old Ottoman sectarian mixed towns of East Jerusalem, Safad, Tiberias, and Hebron (until the departure of the Jews in 1929). The remaining three were the rapidly modernizing coastal towns of Haifa, Jaffa (until the departure of most Jews in 1936), and Acre (until the departure of the Jews in 1929).Footnote 69 In all seven, bifurcated nationalization consolidated spatial separation while capitalist modernization pulled toward integration, creating new residential and economic “contact zones,”Footnote 70 soon to be recognized as politically sensitive.Footnote 71 The inclusive, color-blind logic of capital consumption and production was constantly subverting the exclusionary, essentializing, segregative definitions that fueled the ethnonational drive.Footnote 72

The violent events of 1921, 1929, and 1936–39 (“The Arab Revolt”), which left Hebron, Acre, and Jaffa practically empty of Jewish inhabitants, brought the region at the eve of the 1948 war to a situation whereby only five towns could pass as genuinely mixed: West Jerusalem, the Old City, Safad, Tiberias, and Haifa. Of these five, only Haifa retained a fraction of its ethnic complexion in the aftermath of the 1948 war.

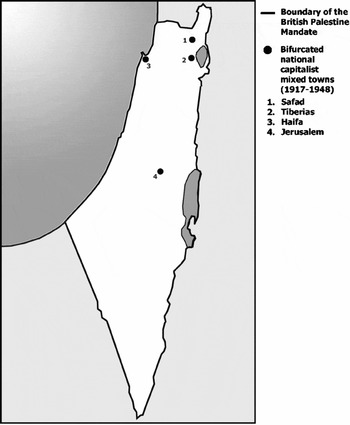

The map in Figure 3 does not present a comprehensive citation of all mixed towns that existed in the relevant period. Rather, it highlights those cases in which older urban models were eclipsed by new ones. Jaffa and Acre are absent from this map because both are hardly relevant to the evolution of the bifurcated national capitalist model of an ethnically mixed town. In both cases, the escalation of national conflict resulted in the 1920s in increasing Jewish flight, rendering them virtually ethnically homogenized (all Arab).

Figure 3 Bifurcated national capitalist mixed towns (1917–1948).

The Truncated Town as War Zone (1947–50)

The 1948 war saw a dramatic severance of Palestinian urbanism.Footnote 73 In 1947, even before the U.N. resolution of November 29 divided Palestine between a Jewish and an Arab state, life in those towns that were still effectively mixed (i.e., Haifa, East Jerusalem, West Jerusalem, Safad, and Tiberias) was becoming tense. Sniper shots, terror attacks, and skirmishes forced people on both sides to retreat to well-defined, often fortified ethnic quarters. As incidents became more frequent, a British-imposed curfew made retreat into one's own enclave compulsory.Footnote 74 Wealthier Palestinian families, anticipating a period of unrest akin to the one they had known in 1936–39, sought temporary shelter with relatives and friends in other parts of the Arab Middle East. Jews by and large stayed put.

The first mixed town forcibly emptied of its Palestinian residents was Tiberias, the 5,770 Palestinian inhabitants of which were driven out—mostly on buses—on 16 and 17 April 1948, when the town was taken by Jewish Hagana forces.Footnote 75 The Palestinian neighborhoods of Haifa, which had been home to 70,000 residents prior to the war, were seized by Jewish forces on 21 and 22 April, producing an immediate, massive flood of refugees. By May, no more than 3,000 Palestinians were left in Haifa. West Jerusalem, where some 24,000 Palestinians had resided prior to the war,Footnote 76 had virtually none by the end of April. The last of Safad's 10,210 Palestinians were forced to flee by 9 May, most of them heading to the east bank of the Jordan.Footnote 77 Mid-May saw Jaffa and Acre fall into Israeli hands.

By then Israeli forces were in control of urban areas nationwide that prior to the war had been home to 215,000 Palestinians. A staggering 70 percent of the prewar Palestinian urban population had fled or was deported.Footnote 78 This happened concurrently with the displacement, in the spring and summer of 1948, of more than 85 percent of the entire Palestinian population, both rural and urban, in the territory that would eventually become the state of Israel. The war that enabled Zionism to establish an independent Jewish state was the one that devastated the Palestinian community. Those Arabs who stayed in situ became what we now know as the Palestinian citizens of Israel.Footnote 79 For a brief period during the war, the old mixed towns, now truncated, became a semivoid. The Palestinian quarters of Safad, Tiberias, Haifa, Jaffa, and West Jerusalem and the Jewish quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem were in a state of sociological catastrophe, with no community to speak of to even bury the dead and mourn the old existence.Footnote 80

The emptied Palestinian quarters of the old mixed towns soon became primary destinations for Jewish immigrants. In mid-June 1948 the provisional government of Israel issued a directive that barred Palestinians wishing to return to their old homes once hostilities abated from doing so.Footnote 81 The directive reflected Israeli apprehensions that areas that previously had been densely populated by Palestinians, once repopulated, might sway the United Nations to exclude them from the final territory of Israel. This fear was combined with a desire to make as many properties as possible available for tens of thousands of Jewish families, both new immigrants and veterans, who had no proper housing.Footnote 82 Whereas Jaffa, and even more so Haifa, saw newcomers occupying Palestinian properties almost immediately and on a large scale,Footnote 83 Jerusalem, where vacated Palestinian residencies were located along the more restless eastern frontier, saw this process developing only as of August 1948.Footnote 84

In Tiberias, the demise of the Palestinian community was coupled in early 1949 with mass destruction of their old properties. By March the Israeli army had blown up and bulldozed 477 of the 696 buildings in the old city.Footnote 85 This left few buildings available for incoming Jewish immigrants, who by April 1949 numbered only 500.Footnote 86 The old city of Safad, where most structures in the Palestinian quarter stayed physically intact, had 1,400 new immigrants installed in previously Palestinian properties by April 1949.

By late 1949 only one of the five towns that had been effectively mixed on the eve of the war, namely, Haifa, still had a Palestinian contingent. Even there, however, the urban mix had been transformed beyond recognition. The 3,000 remaining Palestinians, now representing less than 5 percent of the original community, had been uprooted and forced to relocate to downtown Wadi Nisnas. Given Haifa's proximity to large concentrations of rural Palestinians in the Galilee who in subsequent decades sought urban outlets, Wadi Nisnas soon became the focal point for a quickly growing Palestinian community and serves the hub of the community to date.

The Depopulated, Colonized Mixed Town (1948 to date)

A number of semiurban peripheral towns including Majdal, Beisan, Mjeidal, Halsa, and Bi˒r al-Sab˓, which prior to 1948 had been exclusively Palestinian, were included in 1949 within Israel's internationally sanctioned “Green Line” border. Their entire Palestinian populations having been exiled during the hostilities, these towns were soon rebuilt, repopulated, and reinvented as exclusively Jewish Israeli new towns, and are now known respectively as Ashkelon, Bet-She˒an, Migdal Ha˓emeq, Kiryat Shmona, and Be˒er Sheva. Almost exclusively Jewish, they are of limited analytic value in the present context.

More relevant for our concerns here are Acre, Lydda, Ramle, and Jaffa, which, although exclusively Palestinian before the war of 1948, became predominantly Jewish mixed towns after. All of them had their residual Palestinian populations concentrated in bounded compounds, in one case (Jaffa) surrounded for a while by barbed wire.Footnote 87 As late as the summer of 1949, all of these compounds were subjected to martial law.Footnote 88

These residual Palestinian communities were soon inundated by Jewish immigrants who arrived in Israel in the immigration waves of the 1950s. The ratio of Palestinian old-timers to Jewish immigrants was changing rapidly. More balanced in Acre, at least initially, where a residual population of some 4,000 Palestinians was joined by mid-1949 by some 3,600 Jewish new immigrants,Footnote 89 this ratio was skewed dramatically in favor of incoming Jews in Jaffa (renamed Yafo by Israel), Lydda (now Lod), and Ramle (now Ramla). In Jaffa, Jewish squatters, preferring empty Palestinian houses to transit camps established for them elsewhere, were infiltrating areas initially designated for Palestinians only. This penetration, coupled with an increasing willingness on the part of Palestinians to test the spatial limitations they were subjected to by the authorities, subverted spatial segregations designed and administered primarily by the Israeli security services.

This post-1948 Jewish penetration of urban spaces that hitherto had been predominantly Palestinian was not a new phenomenon. It had been part of the scene in Palestine ever since the arrival of the first Jewish immigrants from North Africa to Jaffa in the 19th century. It had taken place in Haifa since the 1890s, in Acre in the 1920s, and in the rapidly transforming urban landscape of West Jerusalem since the 1880s. In Jerusalem, in fact, new Jewish neighborhoods were being built in the town's rural hinterland, on land belonging to some twenty Palestinian villages.Footnote 90

In the 1950s, however, penetration had a comprehensive, transformative effect. For one thing, Palestinian urban space was now almost completely empty. The old communities of Lydda, Ramle, Acre, and Jaffa had been decimated, with rights in residential properties legally transferred to the state's custodian of absentee property, under the Law of Absentee Property (1950). Unlike earlier periods, however, this time the process was guided by Israeli sovereignty. Urban space was not only available for individual penetration, but also now had the potential of becoming what KimmerlingFootnote 91 calls Israeli space, thus strengthening Jewish immigrants’ resolve to commit themselves to this trajectory.

Although Zionist institutions treated the annexation and control of Palestinian urban space as a signal of historical justice, ordinary Jews who had maintained business and social ties with Palestinians and other Arabs in the region prior to 1948 were more ambivalent. Some were surprised by the sudden transformation of a familiar town into a space from which they now felt alienated.Footnote 92 A Hebrew guidebook to Jaffa, prepared in 1949 for Jewish immigrants about to settle in the town, reflects the incongruities associated with this rapid urban transformation:

The massive immigration [˓alliah] brought about the creation in Jaffa of a Jewish settlement [yishuv] of fifty thousand or more—the largest urban community created by the current ingathering of the exiles. This New-Old Jewish city is like a sealed book—not only for most Israelis living elsewhere, but also for those living in near-by Tel-Aviv and even for many of the residents of Jaffa itself . . . [N]ames of quarters and of streets were revoked and changed in Israeli Jaffa to the extent that it now has a new face [. . .] Jaffa has already become an Israeli city but not yet a Hebrew city . . . This is not the normal process of building a new city. Here the empty shell—the houses themselves—were ready-made. What was left to be done was to bring this ghost town back to life . . . Materially and externally, Hebrew Jaffa is nothing but the legacy of Arab Jaffa prior to May 1948.Footnote 93

KimmerlingFootnote 94 identifies different patterns of control in ethnonationally contested territories. Focusing on presence, ownership, and sovereignty as the key elements, his model suggests that as Israel became a sovereign state and gained the power to deploy settlers (thus creating presence) and to instate a legally sanctioned system of tenure (thus advancing ownership), its control of space was more or less complete. RabinowitzFootnote 95 takes Kimmerling's model a step further by introducing a fourth element—visible environmental transformation. Israel usurped the freedom to have formerly Palestinian space metamorphosed into topi that no longer signified “Palestinianness.” Alternatively, the state neglected Palestinian spaces to the point of rendering them frozen illustrations of the ostensibly premodern, archaic essence of Oriental Arabness—a further ploy to exercise control of newly Judaized space.Footnote 96

Old Palestinian towns were thus evolving into mixed ones. Jaffa and Acre had hosted Jewish minority populations prior to the violence of the 1920s and the 1930s—in the case of Jaffa, a substantial community. Lydda and Ramle had not had Jewish residency to speak of prior to 1948, their mixed communities being reconstructed from scratch. In all four cases, however, the task took place in stressful circumstances. The residual Palestinian population had to recover from the shock of 1948, while the incoming immigrants, who were often housed in Palestinian properties now classified as absentee properties, were struggling with the difficulties of their own displacement.Footnote 97

The first decade after 1948 was thus characterized by a drive to establish new physical structures as well as new social networks and communal institutions. Although Jews and Palestinians sometimes shared houses and even flats, resources pumped by the central government and by local authorities for rehabilitation and welfare were anything but equal. The Palestinian communities lagged behind in education, health care, welfare, employment, planning, and development.Footnote 98 Sixty years later, Palestinian communities in these residual mixed towns still include enclaves of poverty, poor educational facilities, widespread informal residential construction, and pockets of crime.

Predominantly Palestinian towns that were depopulated in 1948 and then immediately repopulated by newly arrived immigrants to become primarily Jewish mixed towns provide the most vivid embodiment of the tragedy of 1948 Palestinian urbanism. Bereft of a bourgeoisie, their political and cultural elites dispersed, their stride toward modernization was violently truncated. Old Palestinian sections in Haifa, Ramla, and Lydda suffered stagnation and urban disintegration. In Jaffa and Acre they were transformed into Orientalist tourist sites,Footnote 99 with capital gains and operational revenues firmly in public or private Jewish hands. This is most apparent in the oldest part of walled Jaffa, gentrified by Jewish artists and known to date as “the artists' colony.”

It is not surprising that many formerly Palestinian urban nodes still bear the scars of fifty years of exclusion, land expropriation, and intentional neglect. It is only recently that some of them have begun a slow recovery. For this Palestinian urban rejuvenation to be successful, however, these efforts will have to radically overturn the prevailing structural inequalities that characterize these towns.

Finally, as Salim Tamari indicates,Footnote 100 old Palestinian towns transformed into mixed cities feature strongly in the imagery of rootedness and return that is cultivated by Palestinian refugees abroad.Footnote 101 Websites dedicated to the history of these Palestinian towns and to potential future rehabilitation of this heritage abound, as do literary and art productions that cultivate them as sites of memory.Footnote 102

Newly Mixed Towns—1980s to date

The 1980s saw the emergence of a new urban residential mix in Israel's peripheral towns. New towns founded by the Israeli government in the 1950s and 1960s—such as Natzerat Illit, Carmiel, and Hazor Ha-glilit—as well as old, predominantly Palestinian towns depopulated in 1948 and reconstituted as exclusively Jewish new towns—such as Safad and Be˒er Sheva— were becoming attractive for Palestinian families, who started moving to them to seek employment and cheaper residential options.Footnote 103

The key was real estate. Land scarcity and rapidly growing populations in most Palestinian communities, particularly in Galilee, created chronic shortages of land available for housing, pushing prices well above levels affordable for young Palestinian families. At the same time, adjacent Israeli new towns, established on cheap state-owned land (which in many cases had belonged to Palestinians prior to 1948), had heavily subsidized residential construction for new immigrants, artificially pushing prices down. This buyers’ advantage was compounded, at certain periods, by negative migration of Jewish residents who, after a few years in the peripheral new town, wanted to relocate to Israel's metropolitan center. Palestinian families from neighboring communities soon began filling this void, renting and purchasing apartments, often becoming the only positive flow of resources into the otherwise dormant local economy. In Natzerat Illit, for example, such a process led to the growth of a Palestinian contingent that by the end of the 1980s accounted for approximately one tenth of the town's population.Footnote 104

The extent to which Jewish-Israeli residents of these newly mixed towns see them as “mixed towns” is an interesting issue. Unlike Haifa, Jaffa, and Acre, where local politicians flag this ethnic mixedness, often manipulating it to their own advantage, the politics of demography in newly mixed towns is much more charged. In Natzerat Illit, where a considerable increase in the size of the Palestinian population in the 1980s met Jewish intransigence and fears,Footnote 105 people asked about the Palestinian presence in the town tended to dodge and obfuscate the issue. In 1988–89, local officials consistently refused to disclose to a researcher any figures concerning the size of the local Palestinian community. A decade or so later, the mayor did go on record, admitting that the Arab minority accounted for 8 percent of the population, but he rejected the notion that Natzerat Illit was a mixed town. In his view, “a town must have a minority of at least 10 percent to be qualified as mixed.”Footnote 106

The phenomenon of Palestinians settling in newly mixed peripheral towns reflects the growth of a vital Palestinian middle class, financially able and politically and culturally willing to face the challenges associated with such choice of residence. Significantly, however, this phenomenon is largely limited to residential use, as Palestinians by and large remain uninvolved in commerce, industry, education, and culture in the newly mixed towns, maintaining social ties and community focus in their neighboring communities of origin.

Safad and Be˒er Sheva form, in this regard, a unique subtype of newly mixed towns. Predominantly Palestinian prior to 1948,Footnote 107 both had their entire Palestinian populations displaced in the war, were reconstituted as exclusively Jewish towns in the 1950s, and have been infiltrated by young Palestinian families since. Most newcomers are not related to the original Palestinian residents, however—a phenomenon known also in Haifa, Jaffa, Lydda, and Ramle.

Finally, a word on the recent phenomenon of young upwardly mobile Palestinians, including university graduates, professionals, and artists who take up residence in long-established Jewish towns, particularly Tel-Aviv. Hanna HerzogFootnote 108 looks at the dynamics of Palestinian yuppies making this move. Their relocation, which happens on a scale too small to make a dent in the demographic balance of any major Israeli city, allows young professionals to come closer to the economic, cultural, and political hubs of Israel. Significantly, it also allows women to break free from the patriarchal shackles of their extended families in the rural hinterland.

Another component of this trend are mixed couples—mostly Jewish women and Palestinian men—who seek the larger city as a place in which they can live their lives more freely. Although some of them choose to reside in Palestinian towns and villages, others prefer mixed and even predominately Jewish towns. The latter create a two-pronged challenge to prevailing views among Jewish Israelis. First, these mixed couples challenge the notion that families and households must be either Jewish or Arab. Second, they subvert the assumption, so widespread among Jewish Israelis, that “Arabs do not belong” in Israeli towns.Footnote 109

Most Jewish-Israeli residents of mixed towns live in communities that harbor tensions and contentions beyond the ethnoterritorial divide. One significant split, evident particularly in Jaffa and Haifa, is along class lines, between lower-class new Jewish immigrants who replaced the original Palestinian inhabitants in the 1950s; residual or incoming Palestinian residents, most of whom are similarly less affluent; and middle-class Israelis, predominantly Ashkenazim. Regardless of whether the middle-class Ashkenazim are erstwhile residents of well-established older residential quarters or recent newcomers into gentrified parts that once belonged to Palestinians, their proximity often triggers resentment on the part of lower-class inhabitants, Jews as well as Palestinians.Footnote 110

The tensions, contradictions, and opportunities associated with life inside a mixed town in contemporary Israel are a vivid illustration of the predicament of Palestinian citizens of Israel as a “trapped minority.”Footnote 111 Contemptuously labeled “Arabs” by their Israeli neighbors, their “Israeliness” is what keeps them apart from Palestinians and Arabs elsewhere. Nominal citizens of a state that denies non-Jews a genuine sense of belonging, they are trapped in the political and cultural cross fire between their state and their nation.

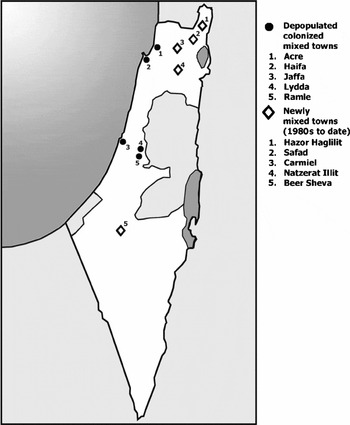

Unlike most Palestinian citizens of Israel, who generally live in purely Palestinian towns and villages, those living in mixed towns are members of a municipal minority as well as of a national one (Fig. 4). Some refer to themselves as “a double minority.”Footnote 112 Representing merely 10 percent of the million or so Palestinian citizens of Israel, they embody the impasse of the community at large as well as hope for novel forms of coexistence.

Figure 4 Mixed towns in Israel, 1948 onward: depopulated/colonized mixed towns and newly mixed towns since the 1980s.

The analytical category “newly mixed towns” represents two variants: new Israeli towns (e.g., Natzerat Illit) established ex nihilo, which later attracted Palestinian residents, and new Israeli towns that replaced pre-1948 Palestinian towns and that later began attracting Palestinian residents (e.g., Be˒er Sheva).

DISCUSSION: URBAN COLONIALISM FROM A RELATIONAL APPROACH

This article fills a gap in the literature on Middle Eastern urbanism. Identifying ethnonational mixed towns as an analytical category, we show how in the case of Palestine/Israel these towns underwent six major historical transformations. Under Ottoman, British, and Israeli rule, they gradually emerged as a distinct city form. Bound by demography, discourse, and history, this sociospatial configuration simultaneously symbolizes and reproduces dialectic urban encounters and conflicts.

The history of ethnically mixed towns in Israel/Palestine since the 16th century is an obvious manifestation of the power of urban colonialism and its vicissitudes in the Levant. In the wake of Ottoman rule and throughout the 20th century, the powerful intervention of European planning ideologies and Zionist projects of territorial expansion resulted in an urban regime that geographers Yiftachel and Yacobi have recently termed “urban ethnocracy.”Footnote 113 This regime of governmental power and ethnic control is notably predicated on the radical division of urban space between the affluent and politically dominant Jewish settlers and the weakened Palestinian community, which is systematically barred from access to land reserves, economic resources, and circles of policymaking.

From an anthropological and historical outlook, our intervention problematizes linear geographical trajectories. Diachronically, we argue, mixed towns evolved from millet-based ethnoconfessional structures to modern nation-based configurations largely determined by the logic of the Palestinian–Israeli conflict. This notwithstanding, ethnographic sensibilities and ethnohistorical inquiry make us wary of treating mixed towns as one monolithic unit. In the case of contemporary Israel, for example, spatial segregation, ethnocratic control, capital accumulation, and political alliances vary considerably between Lydda/Lod, where indexes of segregation and poverty are the highest, and Jaffa and Haifa, which display more varied sociospatial patterns, with Haifa especially offering pockets of more equitable distribution of wealth and access to property, amenities, and political influence.Footnote 114 Geographers have usefully devised means of classifying different modalities of the “urban ethnic spectrum,” from assimilation through pluralism, segmentation, and polarization, all the way to cleansing.Footnote 115 To address this diachronic and synchronic variability we propose the perspective of relationality, developed by Lockman, Stein, Swedenburg, and Monterescu.Footnote 116

As relational historian Zachary Lockman convincingly shows, in the historiography of Israel/Palestine, ideologically motivated scholarship has laid the basis for the model of the “dual society.”Footnote 117 Institutional sociologists such as S. N. Eisenstadt have posited the existence of two essentially separate societies with distinct and disconnected historical trajectories:

The Arab and Jewish communities in Palestine are represented as primordial, self-contained, and largely monolithic entities. By extension communal identities are regarded as natural rather than as constructed within a larger fields of relations and forces that differentially affected (and even constituted) subgroups among both Arabs and Jews . . . This approach has rendered their mutually constitutive impact virtually invisible, tended to downplay intracommunal divisions, and focused attention on episodes of violent conflict, implicitly assumed to be the sole normal or even possible form of interaction.Footnote 118

Equating societies in general with nation-state societies, and seeing states and their national ideologies as the cornerstones of social–scientific analysis, the “dual society” approach has been the main interpretive framework characterizing research on Israel/Palestine. This “methodological nationalist”Footnote 119 stance is a deep-rooted paradigmatic epistemological position that cuts across the spectrum of both Palestinian and Israeli political viewpoints and operates by fixating social agents as independent oppositional actors (settlers vs. natives, colonizers vs. colonized). The relational analysis of Jewish–Arab mixed towns we put forth, although not disregarding the internal processes inherent to each community, avoids the blind spot of the dual-society paradigm and takes the relationship between the Jewish and the Palestinian populations (the latter transformed from majority to minority in 1948) as its central object of study. Moreover, in this view the Palestinian “minority” becomes not merely a passive ethnonational group marginalized by the state but a key and active agent in the historical making of Israeli society and the Palestinian–Israeli conflict at large.

An important clarification is in line here. Although this article proposes a relational and postcolonial reading of ethnically mixed towns in Palestine and, later, Israel, such reading by no means intends to overwrite Palestine's colonial history. In fact it proposes precisely the opposite: while drawing on urban colonialism as its point of departure, it reveals “the fissures and contradictions” of such projects.Footnote 120 Mixed towns are exemplary sites where colonial regimes played their most radical role. This notwithstanding, it is also there that they (fortunately) failed in their attempts to instigate and to sustain a stable regime of complete ethnic separation. Although such attempts at ethnic dichotomization were effective in terms of residential segregation in some cities, when it came to other aspects of urban synergy, they were often subverted by external resistance and internal failures. Taking these as the objects of elaboration, our interpretive paradigm enables a revisionary conceptualization of the urban colonial encounter as one that, as Albert Memmi implies, produces multiple intentionalities, identifications, and alienations.Footnote 121

As we suggested previously, the relational reframing of Jewish–Arab mixed towns should be viewed in contradistinction to three different images of the city prevalent in Middle Eastern studies: the classical colonial city, the divided city, and the dual city. These tropes are not only popular and politically efficacious metaphors of racial segregation, ethnic violence, nationalist struggle, and class division, but they also serve as sociological ideal types and geographical models underwriting urban analysis.Footnote 122

The classical model of the colonial city has been a major gatekeeping concept in such analyses. Following Fanon's foundational work on Algiers, urban colonialism has since been viewed through the Manichean divide between citizens and subjects, Europeans and natives, and colonizers and colonized.Footnote 123 Much scholarly attention, for example, has been drawn to the role of urban planning and architecture in visualizing the rational power and civilizing mission of colonial regimes in the Middle East.Footnote 124 Colonial demarcations between the (Arab) native town and the (European) ville nouvelle signified the superiority of Western modernity and, concomitantly, the absence, perhaps even improbability, of non-European modernities. The colonial city was thus only nominally one city, but in fact it constituted two radically different life worlds and social temporalities.Footnote 125

The violent climate surrounding Arab–Jewish urban relations since the advent of Zionism may induce observer and participant alike to subscribe to a classical colonial paradigm à la Fanon. Although this may be an appropriate description of the situation in the West Bank and Gaza, citizenship configurations in mixed towns inside Israel, and in particular the presence of Palestinian citizens within them, problematize this political and theoretical perspective. Urban mix in Jaffa, Haifa, Acre, Lydda, and Ramla presents a historical and sociological context that complicates a space that no longer corresponds to Fanon's “world cut in two.”Footnote 126 By posing a theoretical challenge to this idealized polarized dichotomy whereby divisions and frontiers are “shown by barracks and police stations,”Footnote 127 ethnically mixed towns of the type we have historicized call for refinements of these analytical tools.

An interesting case in point is historian Mark LeVine's characterization of Tel-Aviv as a colonial city that appropriated and dispossessed Arab Jaffa of its land, culture, and history.Footnote 128 Although this was certainly the case for the first half of the 20th century, the classic colonial city subsequently ceased to provide a nuanced analytical framework. The victory of the Zionist forces and the ensuing Palestinian tragedy of the nakba rocked the foundations of the social and political systems in Palestine and gave rise to a new political subject—the Palestinian citizens of Israel. Henceforth, despite state-funded projects of Judaization, unbreakable glass ceilings, and limited mobility, Palestinians in mixed towns nevertheless chose to participate in the politics of citizenship.Footnote 129 Thus, while Palestinian towns in the occupied territories, such as Ramallah, Nablus, or Hebron, remain sharply colonized and cordoned off by powerful external forces, Palestinian residents of mixed towns within Israel find themselves in a different predicament vis-à-vis the state.

Enjoying equal formal status, Palestinian citizens of Israel tend to channel their resistance to party politics, civil society, and local-level (municipal) spheres rather than to the politics of decolonization. Although many of them do invoke narratives and images of colonization,Footnote 130 these are better seen as mayday calls of disenfranchised citizens rather than collectively organized calls of a national liberation movement. A recent example is the eruption in 2000 of the second Palestinian uprising in Jerusalem, the Galilee, and the occupied territories. Triggering Pan–Palestinian solidarity and frustration, it bred a momentary surge of heated demonstrations on the part of Palestinian residents in mixed towns and amplified those voices there that call for redefining Israeli citizenship to more fully include its Palestinian citizens. Even these events, however, failed to mobilize urban Palestinians within Israel as long-term active participants in the national struggle.Footnote 131 In terms of patterns of political awareness and mobilization, then, mixed towns once again emerge as markedly distinct from colonial cities.Footnote 132

To recapitulate our discussion on the classical colonial city: urban colonialism in mixed towns has worked in different ways from Ottoman rule through British administration and ending with the Israeli state. Except for moments of radical confrontation (e.g., in 1936 or 1948), these cities, by virtue of economic exchange, commercial collaboration, and demographic interpermeation, posed a serious challenge to the logic of colonial segregation. For cities like Haifa (where joint Jewish–Arab mayorship and administration persisted until 1948) and Jaffa (whose relations with Tel-Aviv, as LeVine shows, were nothing but intertwined), the history of colonialism points also to its own political and conceptual limitations.

The divided city is the second powerful trope and urban archetype, one that conjures slightly different images of separation walls, barbed wire, and police patrols.Footnote 133 They evoke barriers of race, religion, and nationality, encoded in dualistic metaphors of East and West, uptown and downtown, and northside and southside. Represented by archetypes such as Jerusalem, Nicosia, Berlin, or Belfast, these towns predominantly reproduce formal discrimination through differential entitlement to citizenship and planning rights. The status of East Jerusalem is perhaps the strongest case for distinguishing the divided city from the ethnically mixed town. In addition to the explicit project of Judaization, which is more implicit in mixed towns, post-1967 Jerusalemites are not Israeli citizens but merely permanent residents.Footnote 134 The unabashed state violence that Palestinians encounter on a daily basis dissuades even the most optimistic activists and analysts from wishful thinking of equal footing and interaction.

The third image we write against is the dual-city model. Although the metaphor of duality has been applied to colonial cities and divided cities alike, it became associated within urban studies with economic restructuring and the vicissitudes of late capitalism. In an age of globablization and increasing disparities between global North and South, the notion of “duality,” which theorizes the contemporary city as a site of unequal production of space,Footnote 135 successfully captures the uneven nature of social and urban change.Footnote 136 Even in the context of advanced capitalism from which this concept emerged,Footnote 137 however, Mollenkopf and Castells—editors of the book Dual City Footnote 138 —conclude that the dual-city idiom is imperfect. As Bodnàr aptly argues, “While there are powerful polarizing tendencies, dichotomies will not suffice: the intersections of class, race and gender inequalities are more complex.”Footnote 139

The concept of urban duality is predicated on the primacy of capital-based dynamics and class structure, often at the expense of ethnic dynamics, cultural factors, and communal relations. Thus the dual-city paradigm often reduces multivaried urban differentiation to the duality of formal and informal labor, and increased professionalization and capital flows. This analytic weakness notwithstanding, in treating the period of decolonization in the Middle East, the dual-city approach has greatly contributed to the understanding of the agonistic transition from colonial occupation to postcolonial self-governance. In Urban Apartheid in Morocco,Footnote 140 Abu-Lughod argues that the “caste cleavages” of social and spatial segregation the French instituted in 1912 had been progressively transformed by the late 1940s into a “complex but rigid system of class stratification along ethnic lines.”Footnote 141 This, however, was replaced in turn by systemic class-based residential separation, which emerged in the 1970s.Footnote 142

In the context of ethnically mixed towns in Palestine/Israel, the continual presence of ethnonational conflict does not allow class to overwhelm or supersede ethnicity. The creeping neoliberalization of the Israeli economy and real estate in the last two decades, the recent emergence of a new Palestinian middle class, and consequentially the growing number of young Palestinian professionals who chose to live in mixed towns have introduced class into an already complicated urban matrix, which became more fragmented and diversified rather than dual. Thus the model of the dual city, as well as of the divided city or the colonial city, does little to provide an adequate framework for explaining and interpreting residential choices, urban-planning dynamics, electoral coalitions, and urban violence in these towns.

To conclude, although excellent research by individual scholars on ethnically mixed towns in Israel/Palestine is certainly to be found,Footnote 143 we argue that this field of research can greatly benefit from a new comparative conceptualization of mixed towns as a historically specific sociospatial configuration. Insisting as we do on the importance of a joint analytic framework, it is key to bear in mind that these towns emerged de facto—that is to say, not as a theoretical, ideological, or deterministic model but in practice—as a new type of city that resulted from the historical hybrid superposition of old and new urban forms. Out of the collusion of the old Ottoman sectarian urban regime and the new national, modernizing, and capitalist order (both Palestinian and Zionist)—there emerged in the first half of the 20th century and, more dramatically, since 1948, a new heteronomous urban form.Footnote 144 Bearing traces of the old one, it was in fact a fragmented amalgam of various city forms.

If the story of mixed towns has a moral, it is perhaps that nationalistic attempts at effacing and rewriting history as part of an effort to create a country (or at least a cityscape) that is ethnically cleansed are bound to fail. This could perhaps provide a “mixed” space of hope.