In April 1893, immediately after the establishment of the Railway Police (Bulis al-Sikka al-Hadidiyya) under the Ministry of Interior (Diwan al-Dakhiliyya), the new department conducted a survey of local station ghaffirs (guards) that intended to inspect the rampant crime along Egyptian railway lines.Footnote 1 On 18 May, Bimbashi (equivalent to Lieutenant Colonel) E. Marten, the first commandant of the Railway Police, presented a summary of this inspection to the Egyptian Railway Administration (Administration des chemins de fer, des télégraphes et du port d'Alexandrie, henceforth ERA). Marten described in-transit cargo theft as the “chief class of crime on the railway.”Footnote 2 In search of a reason, he blamed the Egyptian police for being a parochial, shorthanded, under-skilled, and badly organized force, and more often than not an institution that cooperated with criminal activities rather than preventing them.Footnote 3 Marten's assertion that the rampant crime was a result of an inadequate police force resonated with the accounts of Lord Cromer (Evelyn Baring), the British consul-general in Egypt from 1883 to 1907. With his stated goal of “a well-established reign of law,” the viceroy expressed his disappointment in the ineptitude of law enforcement in Egypt, noting that the “law [did] not inspire sufficient terror to evildoers.”Footnote 4

Both Bimbashi Marten and Lord Cromer typified the way British colonial officials viewed the rampant crime along the rail networks and how they planned to tackle the problem. From their perspective, the arbitrariness of Egypt's law enforcement had led to the frequent escape of criminals from punishment. Although we may be tempted to take this colonial viewpoint with a grain of salt, I did find that among the eighty-eight cases from the Diwan al-Dakhiliyya collection of Dar al-Wathaʾiq al-Qawmiyya (National Archives of Egypt), on which this article is based, the police succeeded in identifying and apprehending culprits in only fifteen cases, showing a 17 percent clearance rate. Indeed, colonial officials, perhaps out of fear of bringing their own competence into question, underplayed the efficiency of the police they oversaw. The 17 percent clearance rate was significantly lower than the average rate of 43.5 percent that Cromer claimed in 1906.Footnote 5 My analysis considers the reasons for this low clearance rate. Colonial officials presumed that the main causes of rampant railway crimes lay in the decentralized character of the Egyptian police system, the ambiguous nature of its authority and responsibility, and the insufficient training of its executive officers. They believed that to fundamentally change the status quo, an “arbitrary system” had to be replaced with more “modern” and “scientific” supervision, so that criminals would stand in awe of the police, and of the power of the British Empire.Footnote 6 To their minds, railway crimes underlined the necessity and urgency of strengthening social supervision as a preventive measure against crime and its attendant unrest.

Departing from the colonial narrative that inadequate surveillance led to rampant railway crime, this article focuses on sophisticated networks of the marginalized who sometimes engaged in such crimes, their interactions with the new technology, and their relationship to the lower levels of the state bureaucracy, to understand railway crimes as everyday acts that accommodated or resisted the colonial distribution of wealth and centralization of power. The density of railway crimes between 1876 and 1904 coincided in time with what the historiography of modern Egypt has tended to characterize as a “imperial high noon, nationalist dawn” or “colonial quiescence and subterranean resistance” in Egypt.Footnote 7 At the beginning of this period, the passionate tide of patriotic ʿUrabism erupted suddenly but soon ebbed away. On the surface, colonial centralization of the government and contractionary fiscal policies were pushing the colony toward new prosperity and stability. In 1876, the Caisse de la Dette Publique had been mandated to establish an international administrative council within the railway administration, marking the transition of power over the Egyptian railway from the khedive to colonial officials even before the 1882 British conquest.Footnote 8 After 1876, headed by British officials who received orders directly from the Caisse and Lord Cromer, the international council constituted the supreme authority over the affairs of the Egyptian State Railway until its formal annexation to the Ministry of Public Works (Wizara al-ʾAshghal al-ʿAmma) in 1904 and the subsequent indirect intervention of British advisors to the Egyptian railway.Footnote 9 Between 1876 and 1904, the Caisse closely dictated the ERA's decision-making, implementing a set of contractionary financial practices that became well known during the interwar period as austerity.Footnote 10 Specifically, the Caisse stipulated that the ERA would contribute a prescribed portion of railway revenue for debt repayment, resulting in the administrative council to maximize immediate profits while drastically decreasing long-term investments in infrastructure construction and technological upgrade, as well as wages and subsidies of lower-level employees. In short, the period between 1876 and 1904 featured the centralized control of British officials over the Egyptian railway and the enforcement of austerity in government finance and particularly in the rail sector, making it a coherent period for analysis.

This article draws attention to social crises experienced by Egyptians on the periphery but hidden beneath the exterior prosperity and stability of late 19th-century Egypt. Austerity, despite contributing enormously to Egypt's debt repayment, had an adverse impact on the poorest segments of the Egyptian population, some of whom resorted to robbery and theft.Footnote 11 Despite this context, however, I argue that we should avoid depicting train robbers in overly romantic terms as defiant challengers of the existing colonial order. This article instead explores their complex relationship with the material prosperity brought by the new technology and colonial governance. They lived in symbiosis with the railway infrastructure, stealthily grabbing resources and diminishing the infrastructure's efficiency, yet expecting the system to maintain its status quo.Footnote 12 In this respect, Eric Hobsbawm's pre-organizational and pre-ideological conception of social banditry applies to most Egyptian train robbers of this period, since they unanimously favored tangible material interests and improvisational practices rather than idealistic ambitions.Footnote 13 Their rationales for committing these crimes lacked any obvious nationalist dimension, so they shared few if any similarities with the much later revolutionary railway saboteurs of 1919.Footnote 14 Train robbers and thieves of late 19th-century Egypt, systemically restricted by poverty, lack of education, and the growing inequality that characterized the class structure, resorted to illegal acts as a means of sharing what the booming economy was generating without thoughts of toppling the system.

Whereas the railway facilitated a capitalist and colonial form of wealth distribution, this article focuses on how impoverished Egyptians reacted against this distribution by illegally extracting resources from the transport. As Robert Tignor has observed, Britain's primary goal in maintaining and developing the railway infrastructure in Egypt during the occupation period was “to enable Egypt to move goods easily within the country and ultimately to export some of the products overseas.”Footnote 15 The railway arteries served the movement of commercial goods through the length and breadth of the British Empire, vitalizing liberal capitalism as a global and homogenizing thrust that conquered hitherto self-sufficient economies and interlocked cotton fields along the Nile with fashion stores of the imperial center.Footnote 16 Impoverished Egyptians, under the shadow of capitalist and colonial expansion, declined to accept the marginal role assigned to them, and some among them found ways of struggling against these epochal changes. When they found themselves incapable of making a profit lawfully from the new form of transportation, they engaged in pilfering, looting, and embezzlement in an attempt to alleviate individual or communal pauperization.

This article engages with recent scholarship on technology and society to contend that acts of usurpation highlight the “socially assembling” nature of large-scale infrastructure projects, and points to differentiated experiences of everyday life.Footnote 17 Regarding social assemblage, I specify that the reticulated system of infrastructure convenes all sorts of people and becomes a locus of various forms of social activities, some of which are identified as deviant or illegal by the infrastructure management.Footnote 18 For instance, On Barak, Nikhil Anand, and Fredrik Meiton, respectively, have written about transport delays, water leakages, and electricity theft as manifestations of the new infrastructure's multivalent trajectories, trajectories by which local users of marginalized status crystallized memories of the past, articulated capacities of the present, and set expectations for the future.Footnote 19 In line with the emerging scholarship on technology and society, this article attends to both the way the configuration of the technology shaped forms of criminal activity and the impact of crime on the outlook and practical implementation of technology on the part of railway management. Even though the state itself punished these acts when it could, train robbers and thieves consciously and systematically adapted their extractive tactics to fit both their technological and social conditions. This article, by recognizing the heterogeneous desires and practices of marginalized Egyptians, examines railway crimes—including their occasional violence—within their social settings, to evaluate their roots within domains of the infrastructure, and to understand why and how people turned to it.

The first and second parts of this article examine specific cases in rural areas and in railway stations, respectively. Because of perpetrators’ distinctive strategies and tactics, I discuss two categories of crime separately. When trains ran on the track in rural areas, railway crime featured predominantly gang-related banditry. In comparison, embezzlement and other types of insider crimes occurred more frequently in railway stations of more urban environments. By analyzing individual crime cases, I call attention to the perpetrators’ deployment of everyday knowledge, communal norms, and local networks against police inspection, their adjustments of illegal tactics to technological innovation as well as various colonial countermeasures that intended to install centralized supervision in the forming sphere of the railway. The third part of the article provides macroanalyses of the rampant railway crime in late 19th-century Egypt. Bedouin, land-deprived peasants, and railway employees, the three groups of Egyptians whose activities are most recorded, turned to railway crimes due to their specific living conditions. At the same time, all of them were affected by the same historical trends—government austerity, grassroots political turmoil, and the centralization of state supervision. It was these personal and structural impulses that propelled their illegal acts.

Rural Egypt: Everyday Knowledge, Centralized Supervision, Technological Innovation

Omnia El Shakry, writing about interwar Egyptian criminologists, criticized their elitist prejudice of associating rural crimes with a unique peasant mentality and their ubiquitous ignorance.Footnote 20 In light of El Shakry's critique, I provide a bottom-up narrative of rural crimes by centering robbers’ tactics and strategies. Train robberies, because of their close connection with railway technologies, usually required more skills than run-of-the-mill thefts. Perpetrators needed effective coordination, accurate information, and, most crucially, extensive familiarity with the railway's daily operations. The knowledge they acquired from mundane interactions with the railway's specificities revolutionized ways of using the technology and even prompted new innovations in response, such as in the Egyptian railway's signaling system.

The relatively fast speed of trains posed the greatest challenge for Egyptian bandits in the late 19th century. A typical cargo train ran at an average velocity of 18 kilometers per hour, with a maximum of around 40.Footnote 21 When a train operated at full speed, boarding a carriage and disembarking were practically impossible. Moreover, even if robbers successfully boarded a train, they needed to drop goods to their fellow thieves on the ground. Only low train speeds allowed bags to land on the ground intact. Hence, the railway administration had long boasted that the railway, compared to the steamship, was the “preferred choice” for merchants to ship goods from Upper Egypt to Alexandria.Footnote 22 Notably, traditional river transport was a much easier target for pirates because they could easily carry out inside jobs after bribing the ship captains. The ERA observed, “in Cairo and elsewhere there are well-known boats that empty the sacks of grain on the riverbank and then re-inflate them with a certain amount of land.”Footnote 23 A train's speed, in comparison to a cargo ship, provided it with an inherent protection against assault. Although bandits might bribe train staff, robbery was still technically difficult without a decreased speed. Train robbers, therefore, had to deploy more detailed and complicated tactics when planning an attack. To succeed, they had to determine locations where the speed of passing trains was low and, ideally, on-board train staff were absent.

A successful train robbery depended heavily on slowing down a train to an acceptable speed. The robbers needed to find locations where trains proceeded at less than 5 kilometers per hour. The most obvious place was near train stations. Within several kilometers of stations, trains either slowed down, preparing to stop, or began to accelerate as they departed. These were the opportune conditions for a successful attempt. One such case occurred near the Abu Qirqas station that a bedouin gang preyed on with some regularity between 1886 and 1889.Footnote 24 A month before the gang attempted their first robbery, their members kept watch near the rail to determine the optimal times that cargo-laden trains arrived at or departed from the station. After careful examination, they filtered out passenger trains and empty freight trains and drafted their own “schedule” that included information on the trains that would guarantee a plentiful bounty. Outsiders had no access to that schedule—the inner circle of thieves most likely memorized and shared it among themselves. Yet, this shadowy train schedule accurately directed the plotters to their expected targets. In addition to scheduling their operations, the bedouin of Abu Qirqas developed a specialized division of labor. In carrying out their plans, the bedouin divided into groups with different tasks, including watching security guards, dropping goods from trains, gathering loot, and transporting loot to their camp.Footnote 25 Their actions were well coordinated and stealthy, inasmuch as few train staff ever had time to notice, let alone react to these robberies. Even if railway employees noticed the assault, they were unable to apprehend the mobile and long-vanished outlaws.Footnote 26 Since the bandits’ coordinated efforts were usually accurately timed and well executed, they seldom risked being apprehended.

The Abu Qirgas gang managed to survive for more than three years in the region by selling the booty from train heists. Their lucrative “business” enabled them to feed more of their cattle and even to build a new granary in their stronghold near the village. Moreover, they sold surplus to nearby villagers and became a key player in the local economy. We do not have a clear sense from the records how this black market operated. It is very likely that some stolen goods were used in exchange for political protection from local shaykhs. Village ghaffirs had noticed the gang from the beginning and informed the shaykhs of the gang's business. Yet there was an evident difference in the perceptions of crime between law enforcement officials and the local shaykhs.Footnote 27 The shaykhs chose to turn a blind eye. Even under last-minute pressure from the central government, they refused to act against the gang.Footnote 28 Thus, the gang remained untouched and lived in symbiotic peace with other communities in Abu Qirqas for more than two years. In this period, village shaykhs to some extent tolerated their acts of looting and reselling, partially because these bedouin managed to integrate with economic activities of the nearby villages, and partially because they targeted trains rather than villagers’ properties.

The Cairo government eventually learned about the bedouin gang, not through villagers but from railway staff. As the gang's appetite for theft increased, railway employees of the Minya-Asyut line appeared to fear the consequences of not speaking up. Sending various petitions to the ERA, they revealed the gang's criminal activities and even admitted their own involvement and complicity with the loss of goods. To solve the problem, the ERA negotiated with the governor (mudīr) of Minya Province in September 1889, requesting strong intervention. The governor agreed to the request and dispatched scores of provincial policemen, forcing the bedouin to relocate away from the Abu Qirqas station.Footnote 29 Direct state intervention eventually resulted in the gang's demise.

Since state control in rural areas was relatively lax, communal politics often operated outside the purview of state laws and official regulations. Especially in Upper Egypt, the Cairo government relied on co-opted local elites, giving rise to incompetent curbing of grassroots resistance.Footnote 30 Instead of police officers (ḍābiṭ, pl. ḍubbāṭ) directly dispatched by the central government, village ghaffirs, heavily influenced by rural notables, acted as de facto judges of guilt or innocence.Footnote 31 In 1884, the Council of Ministries (Majlis al-Nidhar), unable to fulfill the ERA's request to expand the size of the security force, ordered provincial authorities to assign supervision duties to local shaykhs and village ghaffirs and asked ERA-hired station ghaffirs to assist them. Despite this direction, the president of the Council frankly stated that “village ghaffirs had little to no responsibility for law enforcement, and the responsibility totally fell on the ERA-hired ghaffirs.”Footnote 32 In the case of Abu Qirqas, local shaykhs and ghaffirs who sympathized with the gang had obstructed fulfillment of law enforcement duties by the state-directed police. Such local support ensured the survival of the criminal gangs and even helped expand their enterprises under the shelter of local community.

Although the Abu Qirqas gang stole a massive quantity of goods during their train heists, their deeds were by no means destructive to the railway system. A more significant threat came from robbers who intentionally halted a moving locomotive. Railway linesmen often found stones or other hard objects being intentionally placed on the rail. For instance, the linesmen between Damanhur and Abu Hummus, after discovering some scattered materials on the rail on 19 August 1893, suspected that some vagrants were responsible for this malicious act. The linesmen also warned that had they not taken emergency measures to remove obstacles, the impact could have derailed the approaching train no. 175 and caused significant damage.Footnote 33 Not all train attackers were unaware of their potential destructiveness. On the Helwan line in November 1881, several bedouin placed obstacles on the rail and stood kilometers ahead, warning the train conductor of the danger. When they discovered that the conductor did not heed their warning, they removed the obstacles at the last minute and abandoned their original plan.Footnote 34 These bedouin exemplified many train robbers in this period who did not want to cause severe injuries or even the death of the innocent by their looting.

Since robbers had little or no intention of endangering public safety but wanted their plans to be effective, some figured out a more deceptive tactic: manipulation of railway signals. Those plotting such acts had to acquire basic knowledge of operating signals, which they acquired through daily observation. In the late 19th century, the Egyptian railway adopted the block signaling system that required a signalman's manual operation (Fig. 1). The system segmented an entire railway line into numerous sections controlled by successive signals. Before a train steamed into a new section, this section had to be cleared of other trains. For this signaling system to run smoothly, a signalman at an intersection of railway tracks kept records of each passing train in a register book. If any train had occupied the section, a warning signal of yellow or red would notify the coming train conductor to slow down or stop. Once the section was clear, the signal light turned green and the train could pass safely.Footnote 35 Signalmen, in this system, were critical to traffic performance. They were well trained in applying the right rules and regulations to any condition to guarantee railway safety. Some signal poles were located far from police jurisdiction, inadvertently creating an opportunity for plotters, who could easily attack these places and manipulate signals. Standardization of the block signaling system unexpectedly produced an unforeseen vulnerability.

Figure 1. A rail crossing with mechanical signaling in Egypt, ca. 1930. Source: “In the Nile Valley: Train Operation in Modern Egypt,” Railway Wonders of the World 2, part 41 (1935): 1314.

Some technically savvy bandits, accordingly, utilized the system's vulnerability to plan their attacks. They sent purposefully wrong signals that might cause an unexpected train stop. One way to manipulate signals was by creating a fabricated red light that interrupted routine communications between signalmen and train conductors. Concealing the original signal with a cover, the plotters would display red lanterns or lamps they prepared in advance to the fast-approaching train. This tactic was used frequently by bandits on the line between Abu Hummus and Kafr al-Dawwar in the Delta. Since none of the perpetrators was ever captured, it was unclear to the police if they belonged to a single or multiple groups.Footnote 36 Ideally for thieves, train conductors would decrease the train's speed upon seeing the red light. Sometimes, an experienced conductor or other train staff could distinguish a fake light from a real one at a closer distance. Or they might notice suspicious people nearby, who were bandits waiting to board the train. Despite this, there might have already been enough time for the on-board bandits to drop several bags of confiscated goods.Footnote 37 This entire thieving process was fast, usually taking no longer than fifteen minutes. In this way, the bandits achieved their goals while minimizing potential danger to the public.

Stealthy bandits would quietly replace signals without detection. However, there were rare occasions when on-duty signalmen discovered their signals being replaced and directly confronted bandits. In such scenarios, violence was unavoidable. One such case occurred near Tanta in 1892 when a gang of robbers approached a signal pole carrying stones, bricks, and a gun. This gang probably did not know the exact workings of railway signaling. Instead of changing the light themselves, they forced the signalman to do it. Initially, the signalman resisted their demands. The bandits beat him with stones and bricks, and even fired a gunshot to scare him. As the final act of their crime, they locked the signalman in the signal box, where he was later discovered and released by his shift workers.Footnote 38

Although violent attacks remained a distinct minority among all railway crime cases, one such incident was enough to cause enormous anxieties for British officials about railway security. Before 1893, railway crime cases were prosecuted by the ERA and local police forces—the Provincial Police (Bulis al-Mudiriyya) or village ghaffirs. A loss of items, once discovered by railway staff, would in theory be immediately reported to the nearest stationmaster, and then to the police station of the relevant borough (ḍābiṭiyya).Footnote 39 Depending on the severity of crime, different levels of police would investigate the case. The former supervision system caused a dilemma in practice: the ERA had no capacity to solve a case—its staff were neither trained in criminal investigation nor equipped with weapons to apprehend suspects; local police forces, for their part, had few incentives for law enforcement—they relied heavily on village ghaffirs who often had ambiguous relations with criminals.Footnote 40 Realizing the inefficiency and potential harmfulness of this supervision system, Henry Settle, who was promoted to the Inspector General of Egyptian Police in 1892, immediately pressed for the establishment of a weaponized police force to take full charge of every railway zone.Footnote 41 Settle's proposal, endorsed by Lord Cromer and put into operation one year later, sought a complete overhaul of the decentralized supervision, in which local police forces were in charge of the rail sections within their own precincts. The new Railway Police overrode the jurisdiction of local police forces and supervised all security issues relating to the railway. They were placed directly under the Minister of Interior and the inspector general, independent of the Provincial Police, which meant that even a provincial governor had no right to give an order to a railway policeman of the lowest rank.Footnote 42 According to Settle's scheme, the majority of railway policemen were selected from veterans of the Mahdist War (1881–99) and were transferred to their new positions as noncommissioned officers.Footnote 43 Over the following years, the Railway Police became the key agency of the British-controlled Ministry of Interior for enforcing a centralized supervision over the entirety of the rail networks.

Another impact of the Tanta incident was to pressure the ERA to improve the signaling system to a level that would technically prevent similar assaults. The ERA estimated that signalmen working in remote areas were at high risk and must be protected at all costs.Footnote 44 In 1903, the ERA launched a signaling department, which started to introduce the Westinghouse electropneumatic system to replace the previous manual equipment.Footnote 45 Technically, the new system provided automatic connections between the signaling apparatus and railway tracks so that signalmen who used to manually switch signals on site could now work in stations kilometers away from signal poles and still exert comprehensive control over signals.Footnote 46 The automatic device greatly reduced the risk of signalmen being attacked in remote signal boxes. Train robbers here forced the administration to technological innovation. The original automatic interlocking system invented by American engineers was aimed primarily at reducing labor cost and human error.Footnote 47 Even though few technical designers would give credit to Egyptian robbers, these unusual “users” of the railway accurately detected otherwise unrevealed technological vulnerabilities and assisted in improving its efficiency. Therefore, they played a critical role in adaption of railway technology to the social circumstances in late 19th-century Egypt.

Railway Station: Insider Crimes, Networks, Accountability

Unlike rural areas, Egyptian railway stations in cities and town centers had enacted stricter security measures that significantly reduced crime. After the British occupation in 1882, the British deployed the City Police (Bulis al-Mudun) who were quartered in metropolitan centers and usually near railway stations.Footnote 48 The City Police handled all crime cases within their precincts, including those related to the railway. With the establishment of the Railway Police in 1893, cases relating to the railway were transferred from the City Police to their authority. Both the City Police and the Railway Police were headed by British officers who had served in the occupation army. Besides police officers dispatched by the colonial government, each stationmaster hired station ghaffirs for daily duties, such as guarding warehouses, managing crowds, and checking tickets. The Ministry of Interior, after being seized by British officials in 1894, persuaded the ERA to relinquish control of station ghaffirs and placed them under the administration of the Railway Police. In doing so, the Railway Police managed to annex the local supervision force to form a unified colonial supervision agency.Footnote 49 Besides police officers and station ghaffirs, each numbered train also had security personnel on board who at times were dispatched by the ERA or hired by goods owners.Footnote 50 These three sources of security—the colonial supervision agency, local station ghaffirs, and train security guards—all monitored the transported goods during loading and unloading, making robbery inside stations for even the most sophisticated bandits difficult to commit.

Since state laws did not necessarily conform to, or take into account, local mores and norms, rank-and-file policemen at times found themselves caught in a dilemma. On 2 August 1883, three bags of cereal were reported missing at the Abu Hummus station and a policeman named ʿAbduh al-Diyab was dispatched to investigate.Footnote 51 After a day of fruitless investigation, the policeman bribed a coachman, who identified the thief as one Hammad Abu Qa'id, a security guard for a nearby British company. Abu Qaʾid was rumored to be a “dangerous malefactor” who at one time had been exiled to the White Nile. After hearing the news, the policeman rushed to the suspect's house. Abu Qaʾid was there; so were the three bags of cereal. Much to the policeman's surprise, however, the suspect was a white-haired, old man with shaky hands. It was apparent that the suspect had lost his physical capacity to work and lived in dire poverty. He made no attempt to hide the cereal and confessed to the crime. He also provided the policeman with the name of his partner in crime. Sympathetic to the old man's circumstances, the policeman turned a blind eye. He left the cereal with the suspect and reported the case as an in-transit cargo loss. Nowhere was Abu Qaʾid's name mentioned in his initial report.Footnote 52

The policeman's attempt to disguise the crime was soon discovered by Boghos Nubar Pasha, who at that time served as the Egyptian member of the railway administrative council.Footnote 53 Although the loss of three bags of cereal was not a serious incident, the case was viewed as symptomatic of the police's dereliction of duty. Boghos Pasha initiated a more in-depth investigation, and during the course of interrogation, the policeman confessed to bribing the coachman for information, concealing the perpetrator's identity, and releasing the suspect without authorization.Footnote 54 As punishment, the policeman was fired. As for the suspect, he was retroactively charged with the theft. In the final police record, he was depicted as “a dangerous malefactor who was exiled in perpetuity and escaped from the place of his exile.”Footnote 55 The coachman's damning statement became the lynchpin in securing Abu Qaʾid's conviction, and the culprit's real and dire socioeconomic situation was not even mentioned.

Two conditions allowed Abu Qaʾid to nearly escape legal sanction. First, his seniority and disability compelled empathy and support. His coconspirator had, in fact, carried out the crime and delivered the stolen goods to him. Other workers in the British company were unwilling to cooperate with the police. Since communal members shared societal mores of helping the weak and infirm, they did not perceive it problematic or guilty to reject modern laws and connive or partner with “criminals.”Footnote 56 In contrast, the bribed coachman only dared to contact the policemen secretly, fearing that his community would see his action as a betrayal and retaliate accordingly. Second, the policeman made the conscious choice to adhere to locally transcribed principles in how he reported the case to his superiors. At that moment, he relinquished his role as a law enforcement official to join forces with the suspect and the wider community.

Because of the mediating role played by rank-and-file railway staff and policemen to connect state institutions with local communities, their corruption would trigger embezzlement and other insider crimes that harmed the railway system. Typically, they did not earn a living wage, nor did they have job security.Footnote 57 Whereas in 1893 a British bimbashi sitting in a comfortable office earned 150 L.E. annually, the wage of an Egyptian nafar (equivalent to private) who worked and lived in a station twenty-four hours a day was only one-eighth of a bimbashi's.Footnote 58 Nafar was not even the bottom rank of the colonial supervision system. Bimbashis and stationmasters recruited private guards and agents, whose names were never identified on the police rosters. Yet it was these anonymous Egyptians on the periphery of state institutions who supervised the daily operations of each railway line at their respective locations. They enforced the law and maintained public order. They also could readily subvert the law for personal interests, and some managed to do so with the help of local gangs. There was one such occurrence near Bani Suwayf in 1880. A railway security guard, whose key responsibility was to protect trains from potential attacks, stole twelve bags of cereal at night. Due to his local connections, he promptly found help from several nearby villagers who transferred the stolen goods to their homes. To conceal his misconduct, the guard reported to the ERA that some unidentifiable “robbers” had planned the attack after the train departed from the Bani Suwayf station.Footnote 59 The closeness of rank-and-file employees to both the railway system and local society made such crime and corruption possible.

To reduce potential corruption among government employees, the ERA tried to improve its accountability system. Previously, multiple people, including train staff, ghaffirs, nafars, and stationmasters, had been simultaneously responsible for cargo loss or damage. In the new accountability system put in place by the colonial government in 1878, only on-site guards, who usually ranked as ghaffirs or nafars, were held directly accountable. A stationmaster's primary responsibility was to oversee his guards. He visited them several times a day and reviewed their records. He would only be held accountable if his subordinates were found complicit in robberies.Footnote 60 In other words, the new accountability system limited each employee's responsibility to his specific task and assigned job role. In the ERA's annual report of 1880, the administration attributed the reduction in the total amount of cargo losses and damages, particularly in Egypt's urban centers of Cairo, Alexandria, and Tanta, to the new accountability system.Footnote 61

This accountability system, however, unexpectedly produced a new set of problems. In this increasingly stratified system that distinguished duties and accountabilities, rank-and-file employees had to be ever vigilant and follow the letter of the law. A moment of carelessness could lead to unemployment, leaving their families destitute. Consequently, they tried as much as possible to cover up their mistakes, sometimes even by making new ones. A case in point occurred at the Abu Hummus station where the conductor of train no. 37 accidentally broke several bags of cereal while loading the cargo. For fear of being held accountable, he scattered the cereal on the train floor to create the appearance of a crime. He further inflicted a self-made wound to prove that he had tried to impede the robbery. Once the train left the station, the conductor immediately contacted the police, claiming that eighteen robbers attempted to board the freight train while eight others used a red lantern to signal a stop. The fabricated robbery was so believable that it deceived almost everyone, including the local newspaper editor who lauded the conductor as a morally upright and courageous hero. After reading the newspaper, the governor of Buhayra demanded that the police find out the robbers. However, much to everyone's surprise, the police found no evidence that the robbery had ever happened except the conductor's own testimony and concluded that the conductor had made up the story himself. The police officers also affirmed that they had handled several other cases invented by railway staff as pretexts to avoid refunding the amount of goods lost through their negligence.Footnote 62

Frequent cargo losses of late 19th-century Egyptian railways made such a fabrication to evade accountability believable. In 1879, cargo losses amounted to a record high of 4,890 kantars, posing a grave concern for ERA management.Footnote 63 Moreover, some of the more violent robberies posed an imminent threat to British-maintained public security.Footnote 64 The police, however, were restricted by their limited resources from monitoring every swiftly moving train. Even if they got a whiff of a planned heist, they could only investigate after goods had been lost and the perpetrators escaped.Footnote 65 Complaints about police ineffectiveness were frequently filed.Footnote 66 Because of the police's low capture rate, some compromised employees calculated it low risk to cooperate with robbers or invent a robbery case.

Filing a false robbery report became a customary tactic among railway employees to divert public attention, cover up their mistakes, and even shift blame to others. This weakened the colonial government's ability to exert full control over the railway. Another example of this kind took place on 4 February 1885. Some station ghaffirs reported that 206 piasters of merchandised goods were missing. In addition to the loss of goods, a guard named Nasir ʿAbd al-Bari was severely injured. The case was initially classified as a robbery and assault. As in many such cases, the culprits were reported to have disappeared without a trace.Footnote 67 However, the stationmaster of al-Wasta suspected that al-Bari, as one of the replacements for some recently dismissed guards, was targeted by his predecessors. Because of the reported cargo loss, the stationmaster also was punished for mismanagement, one of the consequences that the dismissed guards foresaw. A secret police agent eventually confirmed the stationmaster's suspicion. He identified several ex-guards and testified that they planned the attack for the express purpose of avenging their recent dismissal.Footnote 68

Inside jobs made up a considerable percentage of overall crime cases. The vast and growing class inequalities of late 19th-century Egypt contributed to this type of crime. Rank-and-file employees received a low income and had little to no job security. Meanwhile, they kept close ties with the local society, including outlaws, and felt increasing pressure from the ERA's accountability system. Additionally, due to poor organization, police rarely solved cases of railway crime. These conditions made fertile ground for embezzlement and other insider crimes. For rank-and-file employees, crime definitely was not a long-term solution. But it was understood as a pragmatic means to financially support themselves and their families.

Macro-Criminology: Macroscopic Analyses Of Egypt's Railway Crime

After this close examination of individual cases and criminal tactics, let us now step back to review the question proposed by colonial officials at the start of the article: Why did railway crimes loom large as a social problem in Egypt by the late 19th century? In this part, I propose to reassess the question from the macroscopic perspectives of macro-economic policies, political climate, and government supervision.

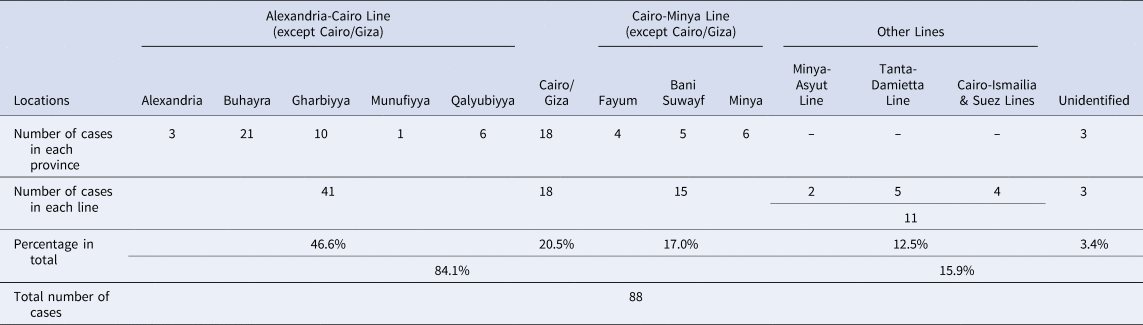

The geographical distribution of railway crimes (Table 1) reveals the overall materialistic intentions behind this type of crime. The Alexandria-Cairo-Minya line accounted for 84.1 percent of the cases studied in this article, and on this line, crimes more frequently occurred in line sections near Egypt's major cities—especially in Cairo's suburbs and south of Alexandria between Abu Hummus and Kafr al-Dawwar (in Buhayra province). The Alexandria-Cairo-Minya line transported the most agricultural materials—cotton, sugar, and cereal—which also were means of subsistence for criminals. The world-famous long-staple cotton grew mainly in the Buhayra, Gharbiyya, Dakhiliyya, and Sharqiyya provinces. Every year between September and December, trains transported voluminous amounts of cotton from these provinces to Alexandria for export.Footnote 69 Stationmasters in the major stations along the cotton lines—Minya, Cairo, Tanta, Alexandria—hired seasonal workers and additional security guards to ensure the smooth and safe transportation of cotton.Footnote 70 Sugar cane was almost exclusively grown in Upper Egypt, in the fertile Nile basin between Cairo and Aswan (Fig. 2). After being processed, refined sugar embarked on its journey to Cairo and Alexandria.Footnote 71 A substantial portion of sugar was exported to the United States, England, India, and the Ottoman Empire via the Port of Alexandria.Footnote 72 Whereas Egypt exported cotton and sugar, by 1865 it became a net importer of cereal.Footnote 73 Wheat and barley from France and Russia were initially gathered in Marseille and Novorossiysk and then shipped to Alexandria. From Alexandria, imported cereal was dispatched to Cairo and other Egyptian cities via railways.Footnote 74 Trains transported cotton and sugar to Alexandria and carried cereal and other imported industrial products back to inland cities, with completely full freight wagons for the round trip.

Table 1. Distribution of railway crimes by railway line and province, 1876–1904

Source: 88 cases from the Diwan al-Dakhiliyya collection of Dar al-Wathaʾiq al-Qawmiyya, Cairo, Egypt.

Figure 2. “Cane being transported by railroad to the factory,” ca. 1900. Source: Walter Tiemann, The Sugar Cane in Egypt (Altrincham, UK: Office of International Sugar Journal, 1903), plate V.

Since material benefit was the primary motivation for late 19th-century crimes, criminal activities pointed toward redressing, albeit unconsciously, the social inequality partially derived from the dispositions of infrastructure. From a long-term structural perspective, when poverty hobbled the poor, looting became a practical means of redistributing resources and redressing wealth inequality.Footnote 75 But why did railway crimes break out in the late 1870s rather than a decade earlier when poverty was equally rampant in Egypt? I argue that a sharp rise in crime was in part a direct social response to the strict austerity policies in the wake of European assumption of Egypt's debt repayment.Footnote 76 Austerity denotes a series of contractionary fiscal policies, including both spending cuts and revenue increases, taken by the Caisse de la Dette Publique to repay the enormous foreign debts Egypt accumulated before 1876.Footnote 77 Specifically, the Caisse terminated all state-sponsored infrastructure projects in the 1880s and controlled on average 45 percent of total state revenues between 1876 and 1904.Footnote 78 By its measures of stimulating short-term revenue and reducing long-term investments, the Caisse sought to recover Egypt's fiscal balance and ultimately guaranteed the benefits of European creditors. However, austerity had indelible negative impacts on Egyptian society. Prior to 1876, reactions of the lower-class population to social inequality were lessened by the massive public expenditures of Khedive Ismaʿil (r. 1863–79). I am not arguing that the Egyptian society was more socioeconomically equitable during the reign of Khedive Ismaʿil. But Ismaʿil's extravagant investment in infrastructure, functioning as an embryonic form of modern social welfare, provided job opportunities and basic salaries, albeit in an unequal manner, to the Egyptian lower classes who would have starved without these government-sponsored expenditures and subsidies.Footnote 79 With the advent of austerity, however, the poor could no longer benefit or receive subsidies from previous expansionary policies. Concurrently, they found themselves impaired by rapid land consolidation and increasing capitalist exploitation, enterprises that were often stimulated by frenzied speculation in Egypt's bubbling financial market.Footnote 80 Under these circumstances, banditry, embezzlement, and other types of insider crimes helped ease the tensions caused by the appropriation of wealth that the railway itself facilitated.

The political turmoil created by the ʿUrabi Revolt (1879–82) mobilized grassroots Egyptians. Juan Cole demonstrates how numerous indigenous groups mobilized against the European invasion during this period by engaging in crimes and protests.Footnote 81 During the revolt, the railway provided the British army with both personnel and logistical transportation, and was vitally important for its success.Footnote 82 Of note, there is no evidence that the railway crimes committed after the ʿUrabi Revolt were a continuation of anti-British protest. The revolt, however, stimulated grassroots mobilization and forged an environment in which crimes and other small-scale disturbances converged. As described, criminals were deeply intertwined with local networks and communities, sharing community-based beliefs and values that underscored their identity and participation in what Partha Chatterjee identifies as “political society.”Footnote 83 Although local communities during this austerity period did not directly confront the state, as occurred later in the Dinshawai incident (1906) or the Egyptian Revolution of 1919, they extended moral support, protection of personal security, and even political shelter to criminals.Footnote 84 With the help of their communities, many criminals managed to evade state supervision and sanction, partially explaining the poor success rate of the Egyptian police in solving railway crimes.

Besides social and structural incentives that spurred crime in late 19th-century Egypt, reforms undertaken by the colonial government managed to centralize the supervision system, thus rendering various types of railway crimes a unified category recorded by the state. As Nathan Brown shows, 19th-century banditry in Egypt was both discovered and invented by the government, not in the sense of fabricating events, but by constructing new institutions that reinterpreted events and recognized them as criminal activities.Footnote 85 The founding of the Railway Police marked the separation of railway crimes from other crime cases in government records. The specialized Railway Police, garrisoning twenty-four hours a day and seven days a week in stations, maintained full responsibility for investigating criminal cases, with rare interference from the ERA or local provinces. They further coordinated public resources, which previously had been decentralized among stationmasters, provincial policemen, and village shaykhs, to conduct criminal investigations, write examination reports, and correspond with the Ministry of Interior, ensuring that the colonial government could take precautions against potential social unrest.

Although the colonial government began to categorize all crimes related to the railway under a single rubric, it is still crucial to acknowledge the diverse causes that set various bands of individuals on the path to crime. In rural Egypt, bedouin and peasants were perpetrators of most recorded cases. Bedouin were engaged primarily in animal husbandry, and also in dry farming, commerce, and caravan transportation. Existing scholarship has revealed the extent to which bedouin were connected to the wider economy via reciprocal exchanges of daily goods with settled populations.Footnote 86 With these economic relationships, bedouin could easily barter booties from train heists for needed supplies. For instance, some tribesmen of the Awlad ʿAli, among the most influential bedouin in the Western Desert, were associated with salt theft and smuggling near Abu Hummus between 1887 and 1888. The bedouin, equipped with horses and modern weaponry, were accused of killing multiple coastal guards and train staff during extensive looting. They began to monopolize the salt supply of many villages in the greater Abu Hummus region.Footnote 87 The high mobility of these nomads made them difficult targets for the police to apprehend on site. Garrisoning at railway stations, policemen were unable to detect in-process robbery and could only conduct subsequent investigations, when bedouin were nowhere to be found. Moreover, the bedouin had enjoyed a certain degree of legal and political autonomy, whereby the government acknowledged the tribal judicial system (ʿurf) as the means of settling disputes. Because of this autonomy, the police were unable to search bedouin suspects within the tribal territory.Footnote 88 As a countermeasure to bedouin raids, the colonial government tried to co-opt tribal leaders to help constrain their tribesmen from looting. In the most successful scenarios, the government appointed tribal shaykhs as state officials to protect the security of railway and telegraph lines within their territories.Footnote 89 Yet this was rare, and bedouin continued to pose a threat to the state's management of the railway.

Egyptian fellahin, sometimes described in government reports as “villagers” (qarawiyyin), also were associated with rural banditry. For peasants, arable land, or at least the right to cultivate on it, represented their most valuable asset. Bearing little resemblance to nomadic bedouin, peasants were more or less incapable of moving freely because of their attachment to land. According to the Khedive's order of 1864, the state could expropriate land on each side of the railway embankments within five kassabahs (17.75 meters) “for the passage of the public,” and it was forbidden to sell this type of expropriated land.Footnote 90 In practice, peasants still cultivated the land beside the railway without tax relief. This state policy changed in the 1890s, when the colonial government permitted landowners to sell cultivable land to private companies, many of them European.Footnote 91 Meanwhile, the central government disinvested from new railway projects and granted concessions to private railway companies to build narrow-gauge railways separate from state-owned standard-gauge lines.Footnote 92 During this process of rapid privatization, private railway companies began to negotiate land transactions directly with landowners. Rise of the speculative real-estate market in the 1890s further encouraged large Egyptian landowners to convert their land assets to shares in the new railway companies.Footnote 93 Notably, these landowners managed to transform themselves into the companies' shareholders and received dividends.Footnote 94 Deals between private investors and landowners, however, had little consideration for the interests of landless peasants. With the rise of large landed estates and the ʿizba (sharecropping) system in 19th-century Egypt, many peasants turned into ʿizba sharecroppers (zurrāʿ) who did not legally possess land properties but made their living by farming lands owned and operated by large landowners.Footnote 95 They lost their houses and already-harvested lands in the land transactions with private railway companies but received little or no compensation for their crops.Footnote 96 Consequently, the land transactions that benefited private companies and large landowners stripped sharecroppers of their means of production and engendered grievous resentment from below. Besides stealing transported goods, land-deprived peasants released their pent-up anger on the railway by intentionally blocking train traffic and attacking train stations.Footnote 97 Women and children also displayed their dissatisfaction by throwing dirt clods and rocks at first-class carriages. Despite the extent to which women and children participated in grassroots resistance, the colonial government regarded their acts less threatening than the robberies organized predominantly by able-bodied men.Footnote 98 Peasant forays against the railway were not limited to a specific town or village; their acts demonstrated a nationwide resentment of railway-induced land transactions.

In urban environments, rank-and-file railway staff and the urban poor comprised the majority of crime suspects. The general board topped the ERA power structure, and the administration had tiers of managers supervising various levels of workers, who constituted the majority of the workforce and were in charge of the railway's daily operations.Footnote 99 The austerity policies affected the various layers of ERA employees differently, with the bottom tier suffering more profound economic losses. The Council of Ministers recorded frequent petitions from rank-and-file railway employees who received a wage cut or who were unable to receive compensation for work-related injuries.Footnote 100 As a result of their disadvantaged situations, some railway employees collaborated with acquaintances outside the railway system to illegally transfer public resources into their own pockets. With their rich frontline experience of the system's daily operation, these employees easily detected and made use of supervision loopholes, and even managed to fabricate evidence for self-protection. In doing so, they desired to hide their criminal actions, shift blame and suspicion onto others, and benefit financially from their criminal activities.

Conclusion: Conceptualizing Railway Crimes In Late 19th-Century Egypt

This article, by focusing on railway crime, reveals the heterogeneous desires and practices at the margins of Egypt's modern infrastructure. It demonstrates the ways marginal populations strove to redistribute social wealth, repurpose the technical promise of modern railways, and confound the intentions of colonial governance. Few train robbers had professional training in railway-related knowledge, but many detected vulnerabilities of the new technology from everyday experiences. They also deployed personal networks and relied on locally sanctioned or accepted mores and norms to create both protection and a respite from state intervention. Robbers and thieves, in their unique fashion, embedded their quotidian experiences and complex social environments into the railway infrastructure. Their everyday knowledge, far from irrelevant to the railway, helped to conceptualize the railway infrastructure as a decentralizing and socially assembling system that invited diversity, contestation, and politics. Michel Foucault characterizes the possibility of “an insurrection of subjugated knowledges” revealing itself at particular historical moments.Footnote 101 The prevalence of railway crimes in late 19th-century Egypt proved the capability of marginalized Egyptians to re-territorialize the terrain of the railway infrastructure with their everyday knowledge and contesting practices.

To respond to the initial question of the recorded rise in these crimes, I suggest that the criminal acts were reactions to a series of socioeconomic trends and administrative measures that challenged the prevailing images of exterior prosperity and stability in late 19th-century Egypt. Economic polarization under fiscal austerity, rapid population growth with rising unemployment, and intensified political participation after the ʿUrabi Revolt contributed to structural impulses toward crime. Additionally, the centralization of railway supervision under British authority facilitated the compilation of surveillance files on various sorts of railway crime cases as a distinct category, rendering these cases legible to high officials of the colonial government and preserving their visibility for 21st-century observers. Although bedouin, land-deprived peasants, and railway employees harbored heterogeneous desires and expectations in their usurpation of the railway system, as a group they challenged the authorized ways of interpreting and operating the infrastructure from their socio-technical positions at the peripheries.

While acknowledging the rebellious nature of railway crimes, in this article I also address their limitations. Central to the types of crimes in late 19th-century Egypt were their prerevolutionary features, even though in a broad sense criminals resorted to political means to bring about individual liberation. Eric Hobsbawm notes that social bandits driven by moral emotions and economic interests often overlooked structural injustice and therefore were unable to redress deep social issues.Footnote 102 Train robbers and thieves lived in symbiosis with the material prosperity brought about by technological progress and colonial governance. Most of them were unwilling to destroy the rail transport, from which they seized benefits. Their material aspirations alone were incapable of bringing a revolutionary change to the country's political system.

By 1904, the urgency of Egypt's debt repayment had lessened. The Egyptian government's expenditure exceeded its revenue for the first time, following twenty-eight years of austerity.Footnote 103 After bearing the material hardship of squeezing railway profits for the Caisse's mission, the ERA was placed under the auspices of the Ministry of Public Works and was released from previous financial constraints. Although still tightly supervised by British advisors, the ERA gradually began to invest in a series of technological advances that, intentionally or otherwise, forestalled previous types of crimes. These advances included updating locomotives that sped up freight trains and remodeling the signal system, which reduced the number of on-site workers. By the early 20th century, the Railway Police managed to centralize nationwide resources that had been dispersed to various local agencies, to identify and subdue criminal activities along the rail. Fewer crime cases are recorded in the archives during the decade before World War I. However, the colonial railway's distribution of wealth for imperial interests did not change. The marginalized did speak, not so much purposively articulating a collective ambition or a revolutionary outlook as uncovering social ills, which they continued to feel deeply.

Acknowledgments

I extend my most sincere gratitude to Juan Cole, Perrin Selcer, Alexander Knysh, and Yucong Hao for their insightful comments on the earlier drafts of this article. I am also grateful for the inspirational suggestions from the IJMES editor Joel Gordon and the three anonymous reviewers. Ideas and earlier versions of this article were presented at the Eisenberg Institute for Historical Studies (EIHS), the annual meetings of the Society for the History of Technology (SHOT) and the Middle East Studies Association (MESA). I appreciate the comments from co-panelists and participants at these panels.