No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

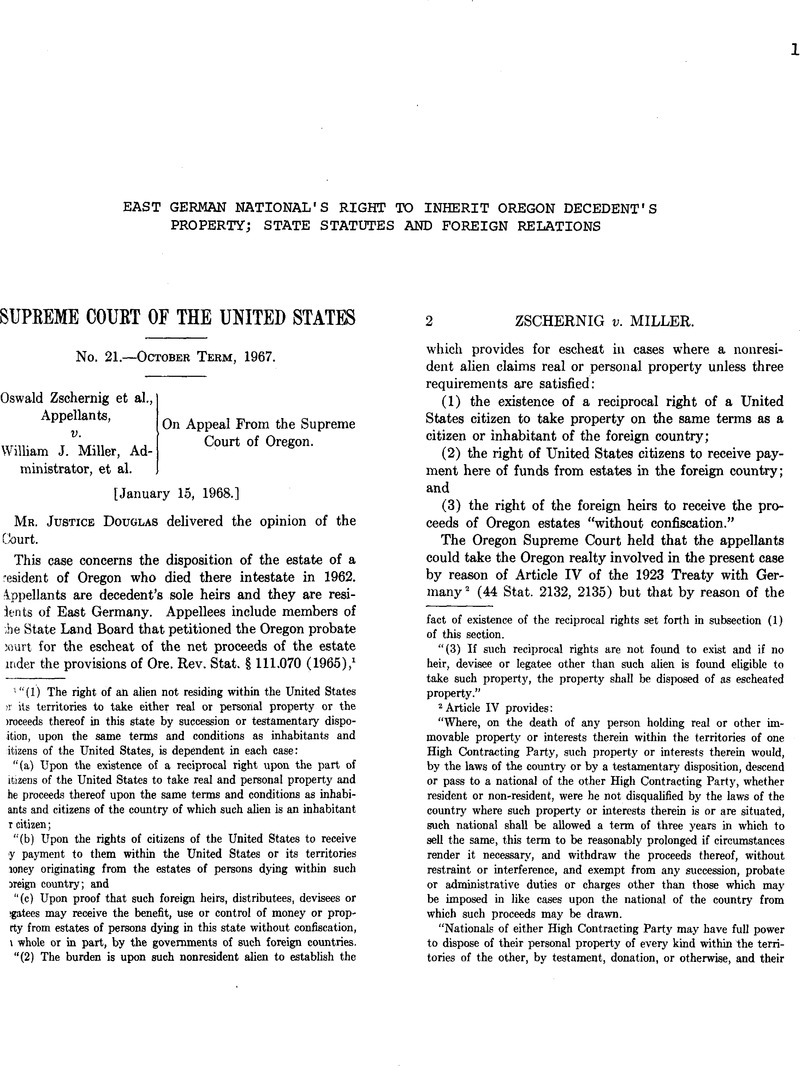

East German National's Right to Inherit Oregon Decedent's Property; State Statutes and Foreign Relations

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1969

References

1 “(1) The right of an alien not residing within the United States or its territories to take either real or personal property or the proceeds thereof in this state by succession or testamentary dispoition, upon the same terms and conditions as inhabitants and citizens of the United States, is dependent in each case:

“(a) Upon the existence of a reciprocal right upon the part of citizens of the United States to take real and personal property and he proceeds thereof upon the same terms and conditions as inhabiants and citizens of the country of which such alien is an inhabitant or citizen;

“(b) Upon the rights of citizens of the United States to receive by payment to them within the United States or its territories money originating from the estates of persons dying within such foreign country; and

“(c) Upon proof that such foreign heirs, distributees, devisees or legatees may receive the benefit, use or control of money or property from estates of persons dying in this state without confiscation, in whole or in part, by the governments of such foreign countries.

“(2) The burden is upon such nonresident alien to establish the fact of existence of the reciprocal rights set forth in subsection (1) of this section.

“(3) If such reciprocal rights are not found to exist and if no heir, devisee or legatee other than such alien is found eligible to take such property, the property shall be disposed of as escheated property.”

2 Article IV provides:

“Where, on the death of any person holding real or other immovable property or interests therein within the territories of one High Contracting Party, such property or interests therein would, by the laws of the country or by a testamentary disposition, descend or pass to a national of the other High Contracting Party, whether resident or non-resident, were he not disqualified by the laws of the country where such property or interests therein is or are situated, such national shall be allowed a term of three years in which to sell the same, this term to be reasonably prolonged if circumstances render it necessary, and withdraw the proceeds thereof, without restraint or interference, and exempt from any succession, probate or administrative duties or charges other than those which may be imposed in like cases upon the national of the country from which such proceeds may be drawn.

“Nationals of either High Contracting Party may have full power to dispose of their personal property of every kind within the territories of the other, by testament, donation, or otherwise, and their heirs, legatees and donees, of whatsoever nationality, whether resident or non-resident, shall succeed to such personal property, and may take possession thereof, either by themselves or by others acting for them, and retain or dispose of the same at their pleasure subject to the payment of such duties or charges only as the nationals of the High Contracting Party within whose territories such property may be or belong shall be liable to pay in like cases.”

3 Supra, n. 1.

4 Ore. Comp. L. Ann. § 61–107 (1940).

5 In Clark v. Allen, 331 U. S. 503, the District Court had held the California reciprocity statute unconstitutional because of legislative history indicating that the purpose of the statute was to prevent American assets from reaching hostile nations preparing for war on this country. Crowley v. Alien, 52 F. Supp. 850, S53 (D. C. N. D. Calif.). But when the case reached this Court, petitioner contended that the statute was invalid not because of the legislature’s motive, but because on its face the statute constituted “an invasion of the exclusively Federal field of control over our foreign relations.” In discussing how the statute was applied, petitioner noted that California courts had accepted as conclusive proof of reciprocity the statement of a foreign ambassador that reciprocal rights existed in his nation. Id., pp. 73–74. Thus we had no reason to suspect that the California statute in Clark v. Allen was to be applied as anything other than a general reciprocity provision requiring just matching of laws. Had we been reviewing the later California decision of Estate of Gogabashvele, 195 Cal. App, 2d 503, 16 Cal. Rptr. 77, see n. 6, infra, the additional problems we now find with the Oregon provision would have been presented.

6 See Estate of Gogabashvele, 195 Cal. App. 2d 503, 16 Cal. Rptr. 77, disapproved in Estate of Larkin, 65 Cal. 2d 60, 52 Cal. Rptr. 441, 416 P. 2d 473, and Estate of Chichernea, — Cal. 2d — , 57 Cal. Rptr. 135, 424 P. 2d 687. One commentator has described the Gogabashvele decision in the following manner:

“The court analyzed the general nature of rights in the Soviet system instead of examining whether Russian inheritance rights were granted equally to aliens and residents. The court found Russia had no separation of powers, too much control in the hands of the Communist Party, no independent judiciary, confused legislation, unpublished statutes, and unrepealed obsolete statutes. Before stating its holding of no reciprocity, the court also noted Stalin’s crimes, the Beria trial, the doctrine of crime by analogy, Soviet xenophobia, and demonstrations at the American Embassy in Moscow unhindered by the police. The court concluded that a leading Soviet jurist’s construction of article 8 of the law enacting the R. S. F. S. R. Civil Code seemed modeled after Humpty Dumpty, who said, ‘When I use a word . . . , it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.’” Note, 55 Calif. L. Rev. 592, 594, n. 10 (1967).

7 The Rogers case, we are advised, prompted the Government of Bulgaria to register a complaint with the State Department, an disclosed by a letter of November 20, 1967, written by a State Department adviser to the Oregon trial court stating: “The Government of Bulgaria has raised with this Government the matter of difficulties reportedly being encountered by Bulgarian citizens resident in Bulgaria in obtaining the transfer to them of property or funds from estates probated in this country, some under the jurisdiction of the State of Oregon. . . .”

8 Such attitudes are not confined to the Oregon courts. Representative samples from other States would include statements in the New York courts, such as “This court would consider sending money out of this country and into Hungary tantamount to putting funds within the grasp of the Communists,” and “If this money were turned over to the Russian authorities, it would be used to kill our boys and innocent people in Southeast Asia. . . .” Heyman, The Nonresident Alien’s Right to Succession Under the “Iron Curtain Rule,” 52 Nw. U. L. Rev. 221, 234 (1957). In Pennsylvania, a judge stated at the trial of a case involving a Soviet claimant that “If you want to say that I’m prejudiced, you can, because when it comes to Communism I’m a bigoted anti-Communist.” and another judge exclaimed, “I am not going to send money to Russia where it can go into making bullets which may one day be used against my son.” A California judge, upon being asked if he would hear argument on the law, replied, “No, I won’t send any money to Russia.’’ The judge took “judicial notice that Russia kicks the United States in the teeth all the time,” and told counsel for the Soviet claimant that “I would think your firm would feel it honor bound to withdraw as representing the Russian government. No American can make it too strong.” Berman, Soviet Heirs in American Courts, 62 Col. L. Rev. 257, n. 3 (1962).

A particularly pointed attack was made by Judge Musanno of ;be Pennsylvania Supreme Court, where he stated with respect to the Pennsylvania Act that:

“It is a commendable and salutary piece of legislation because it provides for the safekeeping of these funds even with accruing interest, in the steelbound vaults of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania until such time as the Iron Curtain lifts or sufficiently cracks to allow honest money to pass through and be honestly delivered to the persons entitled to them. Otherwise, wages and other monetary rewards faithfully earned under a free enterprise democratic system could be used by Communist forces which are committed to the very destruction of that free enterprising world of democracy.” Belemecich Estate, 411 Pa. 506, 508, 192 A. 2d 740, 741, rev’d, sub nom. Consul General of Yugoslavia v. Pennsylvania, 375 U. S. 395, on authority of Kolovrat v. Oregon, 366 C. S. 187.

and further:

“. . . Yugoslavia, as the court below found, is a satellite state where the residents have no individualistic control over their destiny, fate or pocketbooks, and where their politico-economic horizon is raised or lowered according to the will, wish or whim of a self-made dictator.” Id., at 509, 192 A. 2d, at 742.

“All the known facts of a Sovietized state lead to the irresistible conclusion that sending American money to a person within the borders of an Iron Curtain country is like sending a basket of food to Little Red Ridinghood in care of her ‘grandmother.’ It could be that the greedy, gluttonous grasp of the government collector in Yugoslavia does not clutch as rapaciously as his brother confiscators in Russia, but it is abundantly clear that there is no assurance upon which an American court can depend that a named Yugoslavian individual beneficiary of American dollars will have anything left to shelter, clothe and feed himself once he has paid financial involuntary tribute to the tyranny of a totalitarian regime.” Id., at 511, 192 A. 2d, at 742–743.

Another example is a concurring opinion by Justice Doyle in In re Hosova’s Estate, 143 Mont. 74, 387 P. 2d 305.

“In this year 1963, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the U. S. S. R. issued the following directive to all of its member, ‘We fully stand for the destruction of imperialism and capitalism. We not only believe in the inevitable destruction of capitalism, but also are doing everything for this to be accomplished by way of the class struggle, and as soon as possible.’

“Hence, in affirming this decision the writer is knowingly contributing financial aid to a Communist monolithic satellite, fanatically dedicated to the abolishing of the freedom and liberty of the citizens of this nation.

“By reason of self-hypnosis and failure to understand the aims and objective of the international Communist conspiracy, in the year 1946, Montana did not have statutes to estop us from making cash contributions to our own ultimate destruction as a free nation.” Id., at 85–86, 387 P. 2d, at 311.

9 In Mullart v. State Land Board, 222 Ore. 463, 353 P. 2d 531, the court had little difficulty finding that reciprocity existed with Estonia. But it took pains to observe that in 1941 Russia “moved in and overwhelmed it [Estonia] with its military might. At the same time the Soviet hastily and cruelly deported about 60,000 of its people to Russia and Siberia, and, in addition, exterminated many of its elderly residents. This policy of destroying or decimating families and rendering normal economic life chaotic continued long afterward.” Id., at 467, 353 P. 2d, at 534.

“[A]ny effort to communicate with persons in Estonia exposes such persons to possible death or exile to Siberia. It seems that the Russians scrutinize all correspondence from friends of Estonians in lands where freedom prevails and subject the recipient to suspicion of a relationship innimical to the Soviet . . . . This line of testimony has the support of reliable historical matter of which we take notice. We mention it as explaining the futility of attempting, under the circumstances, to secure more cogent evidence than hear-say in the matter.” Id., at 476, 353 P. 2d, at 537–538.

10 See Berman, , Soviet Heirs in American Courts, 62 Col. L. Rev. 257 (1962)Google Scholar; Chaitkin, , The Rights of Residents of Russian and its Satellites to Share in Estates of American Decedents, 25 S. Cal. I Rev. 297 (1952)Google Scholar.

1 Dec. 8, 1923, 44 Stat. 2132, T. S. No. 725.

2 See, e. g., Giles v. Maryland, 386 U. S. 66, 80–81; Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U. S. 306, 316; Bell v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 226, 237; Communist Party v. Catherwood, 367 U. S. 389, 392; Poe v. Ullman, 367 U. S. 497, 503; Machinists v. Street, 367 U. S. 740, 749.

3 See also Alma Motor Co. v. Timken Co., 329 U. S. 129, 136–137.

4 It is true, of course, that the treaty would displace the Oregon statute only by virtue of the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution. Yet I think it plain that this fact does not render inapplicable the teachings of Ashwander. Disposition of the case pursuant to the treaty would involve no interpretation of the Constitution, and this is what the Ashwander rules seek to avoid. Cf. Swift & Co., Inc. v. Wickham, 382 U. S. I l l , 126–127.

5 Petersen v. Iowa, 245 U. S. 170; Duus v. Brown, 245 U. S. 176; Skarderud v. Tax Commission, 245 U. S. 633.

6 The statute appears in the majority opinion at p. —, n. 1, ante.

7 The appellees argue that a substantial part of the 1923 treaty has been terminated or abrogated by the 1954 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation with the Federal Republic of Germany, 7 IT. S. T. 1839, T. I. A. S. No. 3593. However, Article XXVI of the 1954 treaty specifies that it extends only to “all areas of land and water under the sovereignty or authority of” the Federal Republic of Germany, and to West Berlin. The United States does not challenge the holding of the Oregon Supreme Court that the 1923 treaty still applies to East Germany. See Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, p. 6, n. 5.

8 125 Notes from Great Britain, Sept. 24, 1895, MSS., Nat. Archives.

9 Treaty of March 2, 1899, with Great Britain, 31 Stat. 1939.

10 Sept. 10, 1785, 8 Stat. 84, 88.

11 See Art. XI, Treaty of Feb. 6, 1778, with France, 8 Stat. 12, 18; Art. VI, Treaty of Oct. 8, 1782, with the Netherlands, 8 Stat. 32, 36; Art. VI, Treaty of April 3, 1783,’with Sweden, 8 Stat. 60, 64.

12 See also 3 Vattel, The Law of Nations § 112, at 147–148 (1916 ed.); Wheaton, Elements of International Law §82, at 115–116 (1866 ed.).

13 See Borchard, Diplomatic Protection of Citizens Abroad §39, at 88 (1915 ed.); 4 Miller, Treaties and other International Acts of the United States of America 547 (1934).

14 The quotation is from the Swedish treaty. The wording of the Dutch treaty differs only slightly.

15 The earlier treaties used the words “effects” and “goods,” which have been held to include realty. Todok v. Union State Bank, 281 U. S. 449, 454.

16 See 1 Blackstone, Commentaries 372; 2 Kent, Commentaries 61–63.

17 See XXVI Journals of the Continental Congress 357, 360–361.

18 See 2 Diplomatic Correspondence of the United States 1783–1789, at 111, 116–117.

19 Despatch, Wheaton to Legare, June 14, 1843, 3 Despatches, Prussia, No. 226, MSS., Nat, Archives; see 4 Miller, Treaties and other International Acts of the United States of America 547–548 (1934).

20 4 Miller, supra, at 546, 548.

21 Treaty of Nov. 25, 1850, with Switzerland, 11 Stat. 587, 590.

22 See Diplomatic Correspondence of the United States, 1862 Pt. II, 194, 196–197; Foreign Relations of the United States, 1880 952–953.

23 See 4 Moore, , Digest of International Law 6 (1906)Google Scholar. The treat was the Treaty of Dec. 18, 1832, with Russia, 8 Stat. 444, 448.

24 Bacardi Corp. v. Domenech, 311 U. S. 150, 163, citing Jorda v. Tashiro, 278 U. S. 123, 127; Nielsen v. Johnson, 279 U. S. 47 5:

25 See, e. g., Clarke v. Deckenbach, 274 U. S. 392; Friek v. Webb, 263 U. S. 326; Webb v. O’Brien, 263 U. S. 313; Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U. S. 197; Heim v. McCall, 239 U. S. 175.

26 Brief for Appellants, p. 13. Thus, this case does not present the question whether a uniform denial of rights to nonresident aliens might be a denial of equal protection forbidden by the Fourteenth Amendment. Cf. Blake v. McClung, 172 U. S. 239, 260–261.

27 The communication from the Bulgarian Government mentioned in the majority opinion at p. — , n. 7, ante, apparently refers not to intemperate comments by state-court judges but to the v. existence of state statutes which result in the denial of inherira rights to Bulgarians.

28 Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, p. 6, n. 5.

29 Memorandum for the United States as Amicus Curiae, p.

30 See, e, g., Estate of Larkin, 52 Cal. Rptr. 441, 416 P. 2d 4

31 Uniform Foreign Money-Judgments Recognition Act §4 (a)(1), 9B Unif. Laws Ann. 67.

32 See generally Schlesinger, Comparative Law 31–143 (2d ed. 1959).

33 See Slater v. Mexican Natl. R. Co., 194 U. S. 120, 129 (Holmes, J.); American Banana Co. v. United Fruit Co., 213 U. S. 347, 355–356 (Holmes, J.); Cuba R. Co. v. Crosby, 222 U. S. 473, 478 (Holmes, J.); Walton v. Arabian Am. Oil Co., 233 F. 2d 541, 545.