No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

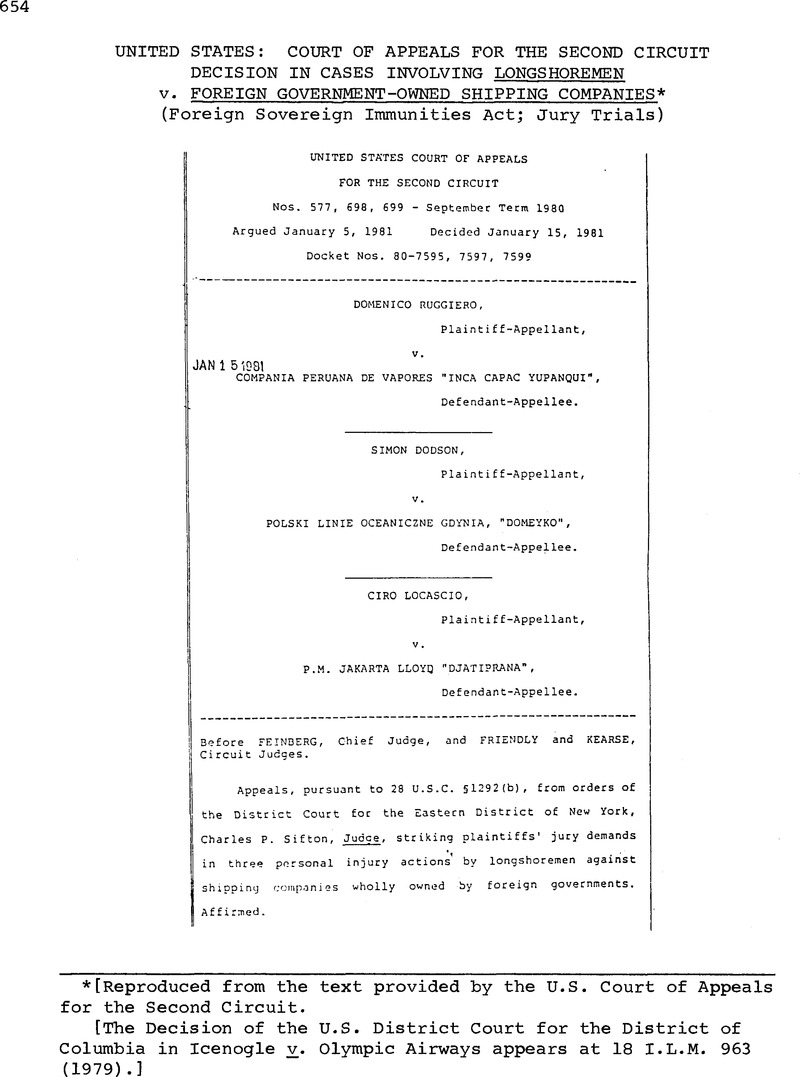

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

[The Decision of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia in Icenogle v. Olympic Airways appears at 18 I.L.M. 963 (1979).]

1. The district court’s statement that the suits sought damages under the Jones Act was mistaken. It has been suggested, however that “5905(b) incorporates the Jones Act”, Gilmore & Black, The Law of Admiralty 455 (2d ed. 1975), See also note 8 infra.

2. Icenoqle v. Olympic Airways, 82 F.R.D. 36, 39 (D.D.C. 1979); Rex v. Cia. Peruana de Vapores, 493 F.Supp. 459 (E.D. Pa. 1980); Houston v. Murmansk Shipping Co., 87 F.R.D. 71 (D. Md. 1980); Lonon v. Companhia de Naveaacao Lloyd Basileiro, 85 F.R.D. 71 (E.D. Pa. 1979). Cf. Williams v. Shipping Corp. of India, 489 F.Supp. 526 (E.D. Va. 1980) (no jury trial in removed action against shipping company owned by foreign state) and Jones v. Shipping Corp. of India, Ltd., 491 F.Supp. 1260 (E.D. Va. 1980) (same). Defendants’ counsel advised us at argument that in some ten cases like those here at issue which are now pending in the Southern and Eastern Districts of New York, judges have stricken demands for jury trial.

3. Appeal from the decision in Rex v. Cia. Peruana de Vapores, supra, is pending in the Third Circuit. Appeals from the decisions in Williams v. Shipping Corporation of India, supra, and Houston v. Murmansk Shipping Co., supra, are pending in the Fourth.

4. These precisions, found in Chapter 97 of Title 28, are preceded by a preamble, 28 U.S.C. §1602, reading as follows:

§ 1602. Findings and declaration of purpose

The Congress finds that the determination by United States courts of the claims of foreign states to immunity from the jurisdiction of such courts would serve the interests of justice and would protect the rights of both foreign states and litigants in United States courts. Under international law, states are not immune from the jurisdiction of foreign courts insofar as their commercial activities are concerned, and their commercial property may be levied upon for the satisfaction of judgments rendered against them in connection with their commercial activities. Claims of foreign states to immunity should henceforth be decided by courts of the United States and of the States in conformity with the principles set forth in this chapter.

5. This ruling was thought, 106 U.S. at 120-21, to follow inevitably from the earlier holding in Ohio & Mississippi R.R. v. Wheeler, 66 U.S. (1 Black) 286, 296 (1862), “‘that where a corporation is created by the laws of a State, the legal presumption is, that its members are citizens of the State in which alone the corporate body has a legal existence; and that a suit by or against a corporation, in its corporate name, must be presumed to be a suit by or against citizens of the State which created the corporate body; and that no averment or evidence to the contrary is admissible, for the purposes of withdrawing the suit from the jurisdiction of a court of the United States.’”

6. Seme argument is made that since $1603 begins with the words “For purposes of this chapter”, to wit. Chapter 57, the reach of the definition of “foreign state” does not extend to Chapter 85 where 51332 is located. This reasoning is obviously flawed since §1330(a), which is also in Chapter 85, itself refers to §1603(a), and sections 1330 and 1332 must be read together.

Counsel also argues, somewhat inconsistently, that Congress’ direct reference to §1603 in §§1330(a) and 1441(d) and the absence of such a reference in §1332 somehow show what congress did not intend to withdraw jurisdiction under §1332 in this class of cases. This argument fails also since there simply was no reason for congress to refer to §1603 in §1332.

7. An additional consideration strongly supporting this conclusion is the new §1441(d) dealing with removal. It is transparently clear that if an entity like these defendants had been sued in a state court and had removed to federal court, on the basis that diversity jurisdiction existed under §1332(a)(2), jury trial in federal court would be barred by §1441(d). Williams v. Shipping Corp. of India, supra; Jones v. Shipping Corp. of India, Ltd., supra. We can perceive no reason why Congress should have wished the situation to be different when suit was initiated in federal court.

Defendants point to another anomaly consequent on plaintiffs’ construction, namely, that corporations owned by foreign states would be subject to jury trial in suits when the amount in controversy exceeded $10,000, but not when it was §10,000 or less.

8. The court may well have been mistaken in assuming there would be a right to jury trial in such cases when §905(b) afforded the sole basis for federal jurisdiction. Unlike the Jones Act, 46 U.S.C. §688, 33 U.S.C. §905(b) does not explicitly provide for a jury trial. The lack of any such reference would seen to require that in suits where no other basis for federal jurisdiction exists, the courts would have to consider the problems dealt with in Romero v. International Terminal Operating Co., 358 U.S. 354, 359-80 (1959), and its progeny. See the discussion of this and related procedural issues with respect to §905(b) in Gilmore & Black, The Law of Admiralty, supra at 455, 470-71. The Fifth Circuit has recently held that §905(b) cannot be a basis for federal jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §1331 and that §905(b) actions invoke admiralty jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §1333, which, of course, confers no right to jury trial, Russell v. Atlantic & Gulf Stevedores, 625 F.2d 71 (1980). We leave all this to the future.

9. We also do not understand the fear of the district judge in Rex, supra 493 F.Supp. at 468, that under our construction of §1330

[a] district court would not only no longer have jurisdiction over a suit against a commercial corporation that happened to be owned fifty-one percent by a foreign state under 28 U.S.C., §1332, but in addition shown would be no jurisdiction in federal question cases (28 U.S.C. §1331); civil rights actions (28 U.S.C. §1343); or other actions relating to regulation of interstate commerce (28 U.S.C. §1337), all of which traditionally are tried by a jury.

Under §1330 the district courts have jurisdiction of all actions against commercial corporations owned by foreign states as defined in §1603. All that is prohibited is jury trial.

Our conclusion with respect to §1331 jurisdiction is reinforced by §1441 (d), see note 7 supra. Clearly if a foreign state, as defined in §1603 (a), were to base removal on the existence of a federal question, §1441 (d) would bar a jury trial. As stated in 1 Moore, Federal Practice 10.66[4) at 700.180, “Of course it would be within the power of Congress to provide for a jury trial in original actions but not in removed actions, but the reason for such a distinction is obscure.”

10. Plaintiffs’ reply brief calls our attention to a recent article, Kirst, Jury Trial and the Federal Tort Claims Act: Time to Recognize the Seventh Amendment Right, 58 Texas L. Rev. 549 (1980). Conceding that “[e]very federal district court and court of appeals that has faced the issue has concluded that the denial of jury trial in FTCS actions does not violate the seventh amendment”. id. at 550, Professor Kirst attacks the rather cryptic statements of the Supreme Court in McElrath and Galloway on grounds of both history and principle. He argues, id. at 563, that “[i]n 1791 it was possible to sue the Crown in a common law action in which there was trial by jury”, referring to the petition of right, which required the king’s consent, and the monstrans de droit and the traverse of office. Although the superiority of the two latter remedies caused the petition of right to fall into disuse for two centuries after 1614, judges continued to mention it, see, e.g., the dissenting opinion of Justice Iredell in Chisholm v. Georgia, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 419, 437-46 (1793); and Blackstone described the procedures, 3 Blackstone, Commentaries on the Law of England 47-48 (Facsimile ed., U. Chi. Press 1979). Apparently all three remedies began in the “petty bag” office of the chancellor but, according to Blackstone, “if any fact be disputed between the parties, the chancellor cannot try it, having no power to summon a jury; but must deliver the record propria manu into the court of king’s bench, where it shall be tried by the country, and judgment shall be there given thereon.” Id. at 48. See also 9 Holdsworth, History of English Law 13-29 (1926); Jaffe, Suits Against Governments and Officers: Sovereign Immunity, 77 Harv. L. Rev. 1, 1-16 (1963). However, the Supreme Court stated in United States v. Lee, 106 U.S. 196, 238-39 (1882), that: “The English remedies of petition of right monstrans de droit, and traverse of office, were never introduced into this country as part of our common law.” Beyond this, if we should assume with Professor Kirst that in 1791 it was generally possible for an English subject to have a remedy against the Crown and that factual issues were tried to juries, this would not necessarily mean that the franers regarded such proceedings as “suits at common law”. We think it unnecessary for us to pursue this further. Whatever the Supreme Court may decide with respect to Professor Kirst’s arguments if these are presented in a case it deems appropriate for review, we are bound by McElrath and Galloway, as well as our own decisions in Cargill, Inc. v. Commodity Credit Corp., 275 F.2d 745, 748 (1960) and Birnbaum v. United States, 588 F.2d 319, 335 (1978), that the Seventh Amendment does not apply in suits against the United States.

11. E.g., Mr. Justice Holmes’ explanation that “[a) sovereign is exempt from suit, not because of any formal conception or obsolete theory, but on the logical and practical ground that there can be no legal right as against the authority that makes the law on which the right depends.” Kawananakoa v. Polvblank, 205 U.S. 349, 353 (1907). See also United States v. Lee, supra, 106 U.S. at 206.

12. Whatever our enthusiasm over the jury may be, this is not necessarily shared by foreign governments — particularly those which may fear that at one time or another they may be politically unpopular with Americans.

13. The lack of any provision safeguarding jury trial in the Constitution as originally adopted was, as is well known, a principal basis for objection in the state ratification debates. We have been cited to nothing in these or in the legislative history of the Seventh Amendment to indicate that the true believers in jury trial had given any thought to the problem here at issue.