No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

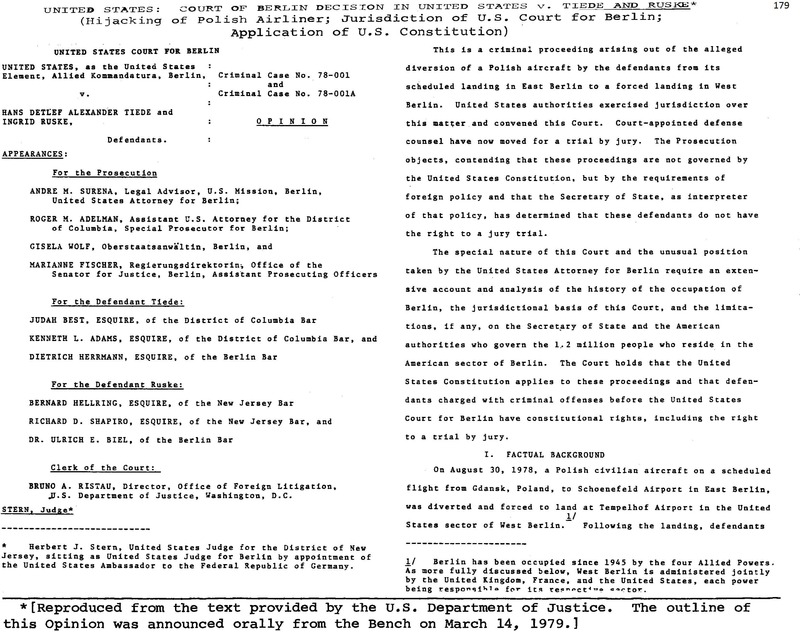

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Department of Justice. The outline of this Opinion was announced orally from the Bench on March 14, 1979.]

* Herbert J. Stern, United States Judge for the District of New Jersey, sitting as United States Judge for Berlin by appointment of the United States Ambassador to the Federal Republic of Germany.

1/ Berlin has been occupied since 1945 by the four Allied Powers. As more fully discussed below, West Berlin is administered jointly by the United Kingdom, France, and the United States, each power being responsible for its respective sector.

2/ Jurisdiction was exercised pursuant to Articles 7 and 10 of Allied Kommandatura Berlin Law No. 7 of March 17, 1950, which provides in pertinent part as follows:

ARTICLE 7

1. The appropriate Sector Commandant may ... withdraw from a German Court, any proceeding directly.affecting any of the persons or matters within the purview of paragraph 2 of the Statement of Principles governing the relationship between the Allied Kommandatura and Greater Berlin.

ARTICLE 10

The appropriate Sector Commandant may take such measures as he may deem necessary to provide forthe determination of cases which under this Law will not be within the jurisdiction of the German Courts.

3/ Law No. 46 Is reproduced In full In the appendix to this opinion.

4/ Senior United States District Judge, and former Chief Judge, of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York.

5/ Former Judge of the United States Court of the Allied High Commission for Germany, and presently the United States Member on the Supreme Restitution Court, Germany.

6/ The complaint read in pertinent part:

That on or about 30 August, 1978, Hans Detlef Alexander Tiede did, by means of force, threats and a weapon, that is a pistol, take a hostage, and divert Polish LOT Flight No. 165 while from it scheduled route of Gdansk, Poland to Schoenefeld Airport and force it to land at Tenpelhof Central Airport in Berlin.

7/ Protocol on Zones of Occupation in Germany and Administration of “Greater Berlin”, Approved by the European Advisory Commission, Sept. 12, 1944, 5 U.S.T. 2078, T.I.A.S. No. 3071, 227 U.N.T.S. 279.

8/ Agreement on Control Machinery in Germany, Adopted by the European Advisory Commission, Nov. 14, 1944, 5 U.S.T. 2062, T.I.A.S. No. 3070, 236 U.N.T.S. 359.

9/ Protocol of Proceedings of Crimea (Yalta) Conference, Feb. 11, 1945, reprinted in DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, 1944-1971, Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 8 (1971) [hereinafter “DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY”].

10/ Declaration Regarding the Defeat of Germany and the Assumption of Supreme Authority by the Allied Powers, Signed at Berlin, June 5, 1945, DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, supra note 9, at 12, 13.

11/ Agreement on Control Machinery in Germany, Art. 3(b), supra note 8.

12/ See Declaration Regarding the Defeat of Germany, supra note 10.

13/ See Protocol of the Proceedings of the Berlin (Potsdam) Conference, August 1, 1945; DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, supra note 9, at 32, 34.

14/ Account Issued by the Department of State on “Soviet Interference with Access to Berlin” in the Period March 30-July 3, 1948; DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, supra note 9. at 101.

15/ Statement Issued by the Soviet Government on Withdrawal of the Soviet Representative From the Allied Kommandatura, Berlin, July 1, 1948; DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, supra note 9, at 100.

16/ Occupation Statute Defining the Powers to be Retained by the Occupation Authorities, Signed by the Three Western Foreign Ministers, April 8, 1949; DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, supra note 9. at 148.

17/ Agreements on Merger of Three Western German Zones of Occupation in Germany and Other Matters, April 8, 1949, United States – United Kingdom – France, 63 Stat. 2817, T.I.A.S. No. 2066, 140 U.N.T.S. 196.

18/ Agreement as to Tripartite Controls, supra note 17, Art. 1.

19/ The position of United States High Commissioner for Germany was established by the President on June 6, 1949, by Exec. Order No. 10062, 14 Fed. Reg. 2965 (1949). The order read in pertinent part:

The United States High Commissioner for Germany, hereinafter referred to as the High Commissioner, shall be the supreme United States authority in Germany. The High Commissioner shall have the authority, under the immediate supervision of the Secretary of State (subject, however, to consultation with and ultimate direction by the President), to exercise all of the governmental functions of the United States in Germany (other than the command of troops), including representation of the United States on the Allied High Commission for Germany when established, and the exercise of appropriate functions of a Chief of Mission within the meaning of the Foreign Service Act of 1946.

20/ Joint Resolution of Congres's, 55 Stat. 451; Pres. Proclamation No. 2950, 16 Fed. Reg. 10915 (1951).

21/ Convention on Relations between the Three Powers and the Federal Republic of Germany, May 26, 1952, 6 U.S.T. 4251, T.I.A.S. 3425, 331 U.N.T.S. 327; Convention on the Settlement of Matters Arising Out of the War and the Occupation, May 26, 1952, 6 U.S.T. 4411, T.I.A.S. 3425, 332 U.N.T.S. 219; Protocol to Correct Certain Textual Errors in the Convention on Relations, June 27, 1952, 6 U.S.T. 5381, T.I.A.S. 3425.

22/ See Protocol on Termination of the Occupation Regime, Oct. 23, 1954, 6 U.S.T. 4117, T.I.A.S. No. 3425, 331 U.N.T.S. 253; Convention on Relaxation, supra note 21.Art 1.

23/ Protocol on Zones of Occupation in Germany and Administration of “Greater Berlin”, supra note 7, 5 U.S.T. at 2080.

24/ Id., 5 U.S.I, at 2081.

25/ Supra note 8, 5 U.S.T. at 2065.

26/ Allied Agreement on Quadripartite Administration of Berlin, July 7, 1945; DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, supra note 9, at 22-23.

27/ The ensuing airborne supply of the citv became known as the “Berlin Airlift.”

28/ See Simpson, Berlin: Allied Rights and Responsibilities in the Divided City, 6 Int. 4 Comp. L/Q. 33, 86-87 (1957).

29/ Four-Power Communique on Agreement on Lifting the Berlin B1ockade Effective May 12, New York, May 4, 1949; DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, Supra note 9, at 154.

30/ Simpson, supra note 28, at 87.

31/ Agreement on Merger of three Western German Zones of Occupation, supra note 17; Agreed Minute Respecting Berlin.

32/ Agreement on Terms for Continuance of the Allied (Western) Kommandatura as the Agency for Allied Control of Berlin, June 7, 1949; DOCUMENTS OS GERMANY, supra note 9, at 160.

33/ DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, supra note 9, at 158.

34/ The Allied Kommandatura reserved to itself, inter alia, the right to supervise the Berlin Police, to take measures related to the Berlin blockade, and to coordinate banking, currency, and credit policies with those of the Federal Republic.

35/ DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, supra note 9, at 159.

36/ Id.

37/ Art. 6 of the Statement of Principles provided:

Subject only to the requirements of their security, the Occupation Authorities guarantee that all agencies of the Occupation will respect the civil rights of every person to be protected against arbitrary arrest, search, or seizure, to be represented by council [sic], to be admitted to appeal as circumstances warrant, to communicate with relatives, and to have a fair, prompt trial.

38/ DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, supra note 9, at 208.

39/ Id.., Art. I.

40/ Exec. Order No. 10603, 20 Fed. Reg. 3093, reads in pertinent part as follows:

1. Executive Order No. 10062 of June 6, 1949, and Executive Order No. 10144 of July 21, 1950, amending that order, are hereby revoked, and the position of United States High Commissioner for Germany, established by that order, is hereby abolished.

2. The Chief of the United States Diplomatic Mission to the Federal Republic of Germany, hereinafter referred to as the Chief of Mission, shall have supreme authority, except as otherwise provided hcceis, with respect to all responsibilities, duties and governmental functions of the United States in all Germany. The Chief of Mission shall exercise his authority under the supervision of the Secretary of State ,and subject to ultimate direction by the President.

41/ Declaration on Berlin Governing Relations Between the Allied (Western) Kommandatura and Berlin, DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, supra note 9, at 209, Art. IV.

42/ Id., Art. V.

43/ See generally. DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, supra note 9, at 277 et seq.

44/ See Note from the Western Commandants in Berlin to the Soviet Commandant Protesting Erection of the “Berlin Wall”, August 15, 1961; DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, supra note 9 at 568; Note from the United States to the Soviet Union Protesting East German violation of the Quadripartite status of Scrlin, August 17, 1961, Report by President Kennedy to the Nation on the Berlin Crisis, July 25, 1961, 45 Dep't State Bull. 267 (1961)

45/ 24 U.S.T. 283, T.I.A.S. No. 7551.

46/ 24 U.S.T. at 343.

47/ See McCauley, American Courts in Germany: 600.000 Cases Later, 40 A.B.A.J. 1041, 1042 (1954).

48/ Proc. No. 1, United States Area of Control, United States Military Government for Germany, July 14, 1945, 12 Fed. Reg. 6997 (1947).

49/ Proc. No. 2, United States Area of Control, United States Military Government for Germany, September 19, 1945, 12 Fed. Reg. 6997 (194T).

50/ Ord. No. 1, Crimes and Offenses, United States Military Government for Germany, 12 Fed. Reg. 21C9 (1947).

51/ Ord. No. 2, Military Government Courts, United States Military Government for Germany, 12 Fed. Reg. 2190 (1947).

52/ Law No. 2, German Courts, United States Military Government for Germany, 12 Fed, Reg. 219] (1947).

53/ Ord. No. 31, United States Military Government Courts for Germany, 14 Fed. Reg. 124 (1948).

54/ Law No. 13, Judicial Power in the Reserved Fields, Nov. 25, 1949, 15 Fed. Reg. 1056 (1950).

55/ Law No. 7, Judicial Powers in the Reserved Fields, Allied KommandaFura Berlin, Mar. 17, 1950, Allied Kommandatura Gazette 11 (1950-53).

That law is still in force today, and was referred to in the communication from the United States authorities to the Berlin Senator for Justice denying the German authorities jurisdiction in the present case. See note 2 supra.

56/ Allied High Commission, Law No. 1, 15 Fed. Reg. 2086 (1950).

57/ See note 40 supra.

58/ See note 4 supra.

59/ Memorandum in Opposition to Defendants' Motion Regarding the Application of the Constitution of the United States to these Proceedings, filed March 6, 1979, at 25-27 [hereinafter “Memorandum in Oopcsition”].

60/ Id. at 28.

61/ Alternatively, the Prosecution argues that the Court has the discretion to deny defendants' motion for a jury trial. It suggests that the Court exercise this discretion for several reasons. First, the Prosecution contends that a jury would be inappropriate in an occupation setting because of the historic function of a jury to oversee governmental authority. Moreover, it contends, laws which mandate participation by Berlin residents in a jury trial would require an exercise of authority unprecedented in the United States occupation of Germany. Further, implementation of a jury system would require the cooperation of local authorities unfamiliar with the assumptions underlying the jury system. Finally, the Prosecution argues, the United States authorities would have to consider whether Berliners serving as jurors might be made subject to pressures, deriving from Berlin's unique political status and geographic location, which might undermine the conduct of a fair trial.

In view of the Court's holding that the United States Constitution dictates that defendants have a right to a jury trial, it is clear that neither the Court nor the State Department has the discretion to deny that right.

62/ Memorandum in,. Opposition, supra note 59, at 10.

63/ Id. at 14.

This quotation was taken from General Clay's account of his administration of military government in Germany. L. Clay, Decision in Germany 249 (1950). state of war was formally ended. It was not until 1955 that sovereignty was returned to the German people everywhere in the Western zones of occupation excepting, of course, Berlin. It is against this background that we must evaluate the claim of the Prosecution that the civilian German population in Berlin in 1979 may be governet by the United States Department of State without any constitutional limitation.

64/ Memorandum in Opposition, supra note 59 at 10-11.

65/ Id. at 2.

66/ Id. at 10.

67/ Id. at 29.

69/ The Prosecution's position was fully explored in oral a when the United States Attorney for Berlin was questioned by Court upon the assertions made in the Prosecution's brief:

THE COURT: [M]ust [the Court] take the directives of the Secretary of State?

***

MR. SURENA: The Court cannot go beyond whatever restrictions the Department of State places upon the Court. That is not to say that the Department of State will affirmatively issue directives to the Court.

***

THE COURT: How will I know when you argue to me on the one hand and when you are telling me on the other?

***

THE COURT: So that if I understand your position correctly, I have nothing to decide. I have only to obey?

MR. SURENA: You have, in our opinion, nothing to decide on the question of a trial by jury.

***

MR. SURENA: Ultimately it is the position of the United States that the question of the applicability of the Constitution is not a question to be decided by this Court, except to decide in agreement withour interpretation that the Constitution does not, of itself, apply in these proceedings.

***

THE COURT: Are you standing there telling me you are prosecutor, judge and jury, that you will make the rules as you wish, change them as you wish, and that all of us must do what you say?

MR. SURENA: No.

THE COURT: Well, then you are going to have to explain to me, Mr. Surena, how you do not have those powers if you are not in any way bounded by the constitution of the United States?

MR. SURENA: I think there may be a difference between having those powers and purporting to exercise them.

THE COURT: No, sir Either you have them or you don't. And if you have them, you may exercise them at will, unbounded by any restraint. Is that what you are telling me?

MR. SURENA: If we have them, then we can exercise them in proceedings before the United States Court for Berlin, without restriction by the Constitution.

THE COURT: Is that what you are telling me, that you may do whatever you wish, and whenever you decide to withdraw your grace, you may do it, at will?

***

THE COURT: Therefore, you are saying, are you not, that there is no right to due process in this court?

MR. SURENA: That is correct.

***

THE COURT: American citizens are subject to the jurisdiction of this Court. Isn't that true?

MR. SURENA: They can be, yes.

THE COURT: Indeed, if the plane which was allegedly hijacked in this case had been hijacked by two Americans, the same procedures, the same proceedings and the same briefs could have been filed; is that not so?

MR. SURENA: Essentially, yes.

***

THE COURT: Is there any guarantee that tomorrow you would not summarily arrest somebody off the street in Berlin, hold them liable for crime, and say, for example, also, I think, from Lewis Carroll, “Sentence first, trial later?” What stops you from that?

MR. SURENA: The history and jurisprudence of the Court.

THE COURT: Which, I gather, is subservient to the directions of the Secretary of State. You told me that, didn't you?

MR. SURENA: Yes.

Transcript of Proceedings of March 13, 1979, at. 66-67; 69, 71, 74-75, 83-84.

70/ Military cases provide the closest analogy to the situation presented here. The United States Court of Military Appeals has repeatedly held that, even muugii iae judge and prosecutor are both appointed by the Executive Branch, the judge is required to remain impartial, and may not be influenced in his decision by his superiors. See, e.g., United States v. Whitley. 5 USCMA 786 (1955) (dismissal of presiding judge at court-martial proceeding for sustaining objection by defense counsel deprived defendant of a fair trial).

71/ Ex parte Quirin, 317 U.S. 1 (1942).

72/ Madsen v. Kinsella, 343 U.S. 341 (1952); Cross v. Harrison. 16 How. 164 (1853); Leitensdorf v. Webb, 20 How. 176 (1857).

73/ See Allied Kommandatura Berlin Law No. 7 of March 17, 1950, Art. Tib).

74/ Ex parte Quirin, supra, n. 68; Johnson v. Eisentrager, 33s U.S. 763 (1950).

75/ Hirota v. McArthur, 338 U.S. 197 (1949).

76/ Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U.S. 763 (1950); In re Yamashita, 327 U.S. 1 (1946); Homma v. Patterson, 327 U.S. 759 (1946).

77/ See note 2 suora.

78/ The circumstances under which the present occupation continues muse be considered by this Court. It is not within the province of this, or any, court to determine when wars end or should end, or when occupations end or should end; such matters relate to the conduct of the United States' foreign policy and are non-justiciable. Commercial Trust Co. Miller. 262 U.S. 51, 57 (1923). Nonetheless, the talismanic incantation of the word “occupation” cannot foreclose judicial inquiry into the nature and circumstances of the occupation, or the personal rights of two defendants which are at stake.

79/ The Court is mindful that a President of the United States proudly proclaimed in West Berlin in 1963:

All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words “Ich bin ein Berliner.”

Remarks by President Kennedy upon signing the “Golden Book,” West Berlin, June 26, 1963, DOCUMENTS ON GERMANY, supra, 633-34.

80/ De Lima v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 1 (1901); Downes v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 244 (1901); Dooley v. United States, 182 U.S. 222 (1901); Fourteen Diamond Rings v. United States, 183 U.S. 176 (1901); Armstrong v. United States, 182 U.S. 243 (1901); Huus v. New York and Porto Rico Steamship Company, 182 U.S. 392 (1901); Dooley v. United States, 183 U.S. 151 (1901); Dorr v. United States. 195 U.S. 138 (1904); Territory of Hawaii v. Mankichi, 190 U.S. 197 (1903). See also Balzac v. Porto Rico. 258 U.S. 298 (1922); Santiago v. Nogueras, 214 U.S. 260 (1909).

81/ Littlefield, The Insular Cases, 15 Harv. L. Rev. 169, 170 (1901).

82/ In the interim, the Court held, in Rassmussen v. United States. 197 U.S. 516 (1905), that the right to a jury trial applied to the territory of Alaska because it had been “incorporated” into the United States.

83/ The United States federal court, established in Puerto Rico as early as April 12, 1900, had from its inception afforded jury trials to criminal defendants. See Act of April 12, 1900, c. 191, Sec. 34, 31 Stat. 84. For the qualifications of jurors in that court, see Act of Just 25, 1906, c. 3542, 34 Stat. 466.

84/ In Reid, the United States exercised jurisdiction over Mrs. Covert in England solely because of her American citizenship.

85/ In footnote, Mr Jv.stice Black quoted with approval the views of two former Secretaries of State — Blaine and Seward -- on the almost unlimited powers which had been conferred in earlier times on consular courts:

Secretary of State Blaine referred to these consular powers as “greater than ever the Roman law conferred on the pro-consuls of the empire, to an officer who, under the terms of the commitment of this astounding trust, is practically irresponsible” S. Exec. Doc. No. 21.

86/ Petitioners were charged with (1) Violation of the Law of War; (2) Violation of Article 81 of the Articles of War, defining the offense of relieving or attempting to relieve, or corresponding with or giving intelligence to, the enemy; (3) Violation of Article 82, defining the offense of spying; and (4) Conspiracy to commit the offenses alleged in charges 1, 2 and 3. 317 U.S. at 23.

87/ See 317 U.S. at pp. 29-46, especially n. 14.

88/ This, interpretation of Quirin draws further support from the fact that the Supreme Court rejected the claim of one of the Quirin petitioners that, as a naturalized citizen of the United States, he was entitled to a jury trial in a civilian court. The Court stated: “Citizenship in the United States of an enemy belligerent does not relieve him from the consequences of a belligerency which is unlawfu because in violation of the law of war.” 317 U.S. at 37.

89/ See discussion supra pp. 16-17.

90/ Between 1916 and the 1957 Supreme Court decision in Reid v. Covert. American civilians accompanying the armed forces abroad were subject to general court martial pursuant to Articles 2 and 12 of the Articles of War. See Madsen, supra, 317 U.S. at 350-52.

91/ Having juries sit in criminal trials in occupation courts in Germany is not so unheard of as the Prosecution would make' the Court believe. The Prosecution suggests that a jury trial might impactpolitically on the relationship between the United States and its two Western Allies, although the nature of that impact has not been enunciated.

The Court notes that the British, with whom we share centuries of legal tradition, regularly afforded to British citizens, tried before their Military Government courts in Germany, the right to trial by jury. See British Ordinance No. 68. 17 Military Government Gazette (British Zone of Control) 437; 26 jld_. 921; 16 Official Gazette of the Allied High Commission for Germany 179. Under this Ordinance, British subjects were entitled to be tried by a jury consisting of seven British subjects in cases involving criminal charges for which the maximum penalty was death or a sentence of imprisonment exceeding five years.

92/ It is also interesting to note that, when the Court made its passing reference to the lack of jury trials in the occupation courts in Germany, it was discussing its conclusion that “[t]he United States Courts of the Allied High Commission for Germany were, at the time of the trial of petitioner's case, tribunals in the nature of milita'ry commissions conforming to the Constitution and laws of the United States.,” 343 U.S. at 356 (emphasis supplied).

93/ The state of belligerency between the United States and Germany was not terminated until 1951. See page 8 supra.

94/ 22 Fed. Reg. 4007.

95/ Public Papers of the Presidents-John F. Kennedy, 1962, 247-48 (1963) (Statement of Mar. 19, 1962). For similar statements see 47 Dep't State Bull. 770 (1962) (referring to “the anticipated eventual restoration of these inlands to Japanese administration”).

96/ The amendments to the Code of March 8, 1963 read as follows:

Chapter 5. Indictment and Jury Trial

1.5.1 Right to Indictment and Trial by Jury.

Any person charged with an offense before a Civil Administration Court shall have the right to indictment by the grand jury as to any offense which may be punished by death or imprisonment for a term exceeding one year and trial by petit jury as to any offense other than a petty offense in accordance with the provisions of this

97/ Memorandum on the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands: Trial by Jury, filed March 6, 1979, at 8-10.

98/ See note 69 supra.

99/ See, e.g., Graham v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 365 (1971) (aliens may not be excluded from state welfare benefits); Sugarman v. Dougall 413 U.S. “634 (1973) (aliens may not be excluded from a state's civil service); In re Griffith. 413 U.S. 717 (1973) (aliens may not be barred from practicing law); Examining Bd. v. Flores de Otero, 426 U.S. 562 (1976) (aliens may not be barred from the engineering profession); Nyauist v. Mauclet. 442 U.S. 1 (1977) (aliens may not be denied state education benefits). But see Foley v. Connelie, 435U.S. 291 (1978) (aliens may be excluded from the state police force).

100 Convention on Offenses and Certain Other Acts Committed on Board Aircraft, September 14, 1963, 20 U.S.T. 2941; T.I.A.S. 6768; 704 U.N.T.S. 219.

101/ Senate Exec. Doc. L., 90th Cong., 2d Sess. 13 (1968).

102/ Senate Comm. on Foreign Relations, Convention on Offenses Committed on Board Aircraft, S. Exec. Rept. No. 3, 91st Cong., 1st Sess. 20 (1969) (Statement of Murray J. Bellman, Deputy Legal Adviser, Department of State).

103/ I.C.A.O. International Conference on Air Law, Proposal of The United States of America, Doc. No. 59, 208, I.C.A.O. Doc. 8565 LC/152-2 (1963).

104/ Memorandum ot the United States Regarding the Selection of

1 Amendment added by Ordinance Amending United States High Commissioner Law No. 46, United States Court for Berlin, done at Berlin, 1 November 197 8, Allied Kommandatura Berlin Gazette, Supp. 96, Page 1220.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Amendment added by Ordinance Amending United States High Commissioner Law No. 46, United States Court for Berlin, done at Berlin, 19 October 1955, Allied Kommandatura Berlin Gazette, Supp. 75, Page 1083.

6 Ibid.

7 Amendment added by Ordinance No. 2, Amending United States High Commissioner Law No. 46, United States Court for Berlin, done at Berlin, 9 February 1957, Allied Kommandatura Berlin Gazette, Supp. 83, Page 1132.