Books under Review

Berry, Marie E., War, Women, and Power: From Violence to Mobilization in Rwanda and Bosnia-Herzegovina (Cambridge University Press, 2018)

Eichenberg, Richard C., Gender, War, and World Order: A Study of Public Opinion (Cornell University Press, 2019)

Ellerby, Kara, No Shortcut to Change: An Unlikely Path to a More Gender Equitable World (New York University Press, 2017)

Hudson, Valerie M., Bowen, Donna Lee, and Nielsen, Perpetua Lynne, The First Political Order: How Sex Shapes Governance and National Security Worldwide (Columbia University Press, 2020)

Sjoberg, Laura, Gendering Global Conflict: Toward a Feminist Theory of War (Columbia University Press, 2013)

Tripp, Aili Mari, Women and Power in Post-Conflict Africa (Cambridge University Press, 2015)

Wood, Reed M., Female Fighters: Why Rebel Groups Recruit Women for War (Columbia University Press, 2019)

In recent years, several countries have voted into office strongman leaders—Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro, Rodrigo Duterte—all of whom are portrayed as hypermasculine and willing to use force against their own people or other countries. At the same time, through its sweeping Women, Peace, and Security agenda, the United Nations treats women's rights as fundamental to international security,Footnote 1 a host of major political figures have embraced the idea that gender equality is foundational to a peaceful world,Footnote 2 and some states, including Sweden, France, Canada, and Mexico, have formally adopted “feminist foreign policies,” centered on the notion that global peace can be achieved through gender equality.Footnote 3 The stark differences in countries’ gendered approaches to security policies illuminate how politics is gendered, and how sex and gender shape outcomes in international politics.

Feminist scholars understood these links between the subordination of women in a given state and that state's likelihood for violence early on.Footnote 4 Feminist research in international relations (IR) flourished in the 1990s, as scholars wrote about using gender both as an analytical category and as a lens through which to understand how and why interstate and civil wars occur.Footnote 5 Feminist arguments have varied, including that sexism and the possibility of war are co-constituted, that more agency for women in conflict decision making may lead to more peaceful outcomes because of women's gendered positions in social and political life, and that the gendered state itself is a source of gendered warfare.Footnote 6

Research on these questions branched in new directions in the early 2000s when quantitative scholars, analyzing large cross-national data sets, demonstrated a statistically significant correlation between sex and gender inequality—measured a variety of ways—and the probability of interstate war and civil conflict, even controlling for many other factors known to be associated with the onset of violence.Footnote 7 This core result has been replicated many times: nearly a hundred studies indicate some type of link between sex and gender inequality and violent outcomes.Footnote 8 Scholars characterize the relationship between sex and gender inequality and war as “well-established,”Footnote 9 and a “near-consensus.”Footnote 10

Yet despite the overwhelming evidence of this connection, it has not been widely embraced in the international politics literature; instead, it has been relegated to a specialized group of IR scholars, whose work is rarely integrated into major IR theories.Footnote 11 In particular, quantitative studies on sex and gender inequality and war face critiques from both quantitative IR scholars and feminist IR theorists. On the one hand, feminist scholars have argued that forms of sex and gender inequality should not be used as variables because they are neither measurable nor quantifiable.Footnote 12 These scholars also view feminist methods as both an analytical tool and a theory in itself, and are critical of the quantitative scholarship for not paying sufficient attention to feminist methods, even while studying feminist questions.Footnote 13 On the other hand, conflict scholars who use quantitative methods also point to measurement problems, albeit for different reasons, and have argued that the numerous ways the core correlation has been tested suffer from a lack of causal identification.Footnote 14 The unfortunate consequence of this two-pronged critique is that the tremendous progress in this field—and its potential for future research—has been largely overlooked.

We argue that there is great merit to studying the complex relationship between sex and gender inequality and political violence. Taking seriously the concerns of both feminist and quantitative scholars paves the way for a multi-method and theoretically informed research agenda that explores the conditions under which sex and gender inequality influence war. In this review essay, we aim to enable scholars to understand better the full complexity of the relationship between sex and gender inequality and war,Footnote 15 and to address some of the critiques from both feminist theorists and quantitative scholars.

The essay proceeds as follows. We begin by describing the aforementioned critiques, emphasizing the importance of more clearly defining and aligning concepts and measurement. We then turn to two important moves in the scholarship that have propelled this research agenda forward: focusing on the mechanisms that underlie the central correlation between sex and gender inequality and war, rather than the correlation itself; and shifting the units of analysis from macro-level, cross-national studies to the micro-level study of individuals and groups. The former move enables better causal identification, and the latter clarifies definitions and the alignment of concepts and measurements. Both moves integrate an intersectional analysis of sex, gender, and war, showing how gender hierarchies do not exist in a vacuum, and are intertwined with race, ethnicity, religion, and other identities. Throughout, our discussion is meant to demonstrate to scholars who use quantitative methods to study the causes and consequences of war how to incorporate core tenets from feminist theory into their work.Footnote 16 While we do not claim to address all possible critiques, we highlight a variety of ways to move forward from where debates have stalled, some of which are already happening.

To demonstrate the value of exploring these two avenues, we draw on seven books published over the past decade that have advanced the agenda of sex and gender inequality and war. All seven books contribute to the larger debate about how and why the unequal status of women and of femininities in society is related to the outbreak of war. They represent a range of academic disciplines (sociology, political science), a wide array of methods and epistemologies (case studies, ethnography, surveys, and experiments), and two subfields of political science (comparative politics and IR).

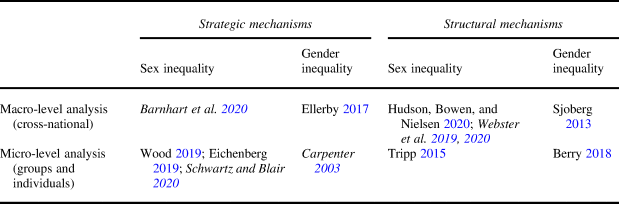

Table 1 provides a framework for classifying the research on women, gender, and war, organized across different dimensions that are theoretically relevant for the next stages of the research agenda. We first organize the books under review (and some illustrative articles) based on whether the central theories rely on strategic or structural mechanisms of women or gender to explain a political outcome. By “strategic” we mean whether political actors have leveraged the category of women or gender to achieve political ends. Alternatively, “structural” explanations are focused on institutions, systems, or environmental contexts that shape how women or gender affect political ends.

Table 1. Sex and gender inequality and war: Categorizing reviewed books

Note: The italicized works are articles. Wood (Reference Wood2019, 9) writes that his book is about sex; however, the survey experiments are about “gender framing and audience attitudes” (xi). Sjoberg Reference Sjoberg2013 does not presume a definitive theory or mechanism to test, but rather argues that all processes are gendered. In some cases (e.g., Tripp Reference Tripp2015), a theory is tested at multiple levels of analysis; we highlight only one in the table.

Second, we categorize the books under review by whether the central theory is about sex (in this case, women) or gender (a continuum of masculinity and femininity).Footnote 17 As we discuss in more detail later, one of the central critiques of feminist IR scholars is the conflation of sex and gender, a classification error that affects the accuracy of hypothesis testing and measurement. Sjoberg and Ellerby are most clearly focused on gender, while the theoretical frameworks in Berry and Wood articulate gender differences (although their measurements are sometimes operationalized as sex).Footnote 18 In contrast, the political and social conditions of women, and women's preferences and beliefs, are featured in the books of Eichenberg, Tripp, and Hudson, Bowen, and Nielsen, and the articles of Barnhart and colleagues and Webster, Chen, and Beardsley;Footnote 19 all of these studies focus primarily on sex. Finally, beyond the strategic and structural theories, the books vary with respect to the unit of analysis: some focus on country-level theories, while others hone in on micro-foundations.Footnote 20 As we argue later, shifting from the macro to micro is a critical step in this literature, and enables more refined identification of causal mechanisms.

Despite their similar themes, these books are not often in direct conversation with each other, and in fact the authors mostly do not cite each other. This fact itself highlights one of our main points: the literature on sex and gender inequality and war is sharply divided by subfield and methodological orientation. Cross-pollination within subfields and among scholars in the broader IR subdiscipline will enable a far richer and more comprehensive discussion about gender, sex, and conflict. The books under review represent the vanguard of research on the complex relationships between sex, gender, and war, allowing us to assess where the research has been, and to set out where it might go next. One of our goals in this essay is to bring together a diverse set of findings—from these seven recent books and a host of journal articles—to make a broader argument about how sex and gender inequality interact with political violence, and what a productive future research agenda could include, particularly for quantitative empirical scholarship.

A Two-Pronged Critique of the Sex and Gender Inequality and War Argument

The argument that sex and gender inequality predicts war has received criticism from feminist IR theorists and scholars who use quantitative methods; we review both sets of critiques.

Feminist Critiques of Sex and Gender Inequality as a Cause of War

Feminist IR scholars have pointed to the link between sex and gender inequality and war for decades,Footnote 21 but have also critiqued (some of) the quantitative work that demonstrates a statistical correlation. These arguments take different forms, but here we focus on the most fundamental: the conflation of gender and sex in theory and measurement.

Much of the quantitative work on sex, gender, and war uses gender interchangeably with, and as a synonym for, biological sex.Footnote 22 This is a conceptual error, and one that has consequences for the types of research questions that are asked, and how they are answered. Gender is “the socially constructed expectation that persons perceived to be members of a biological sex category will have certain characteristics.”Footnote 23 In other words, gender refers to the socially constructed ideas and narratives of what it means to be a man or a woman and individuals’ conformity to those ideas. In contrast, sex refers to the biological or physiological features that make an individual a man or a woman.Footnote 24 The conflation often occurs when scholars blend gender and sex by assuming that women are (always) feminine and men are (always) masculine. It is a mistake, many feminist IR scholars argue, to use biological sex—often assumed to be immutable—to measure gender, which is fluid, contextual, and relational.Footnote 25

Gender equality implies an equal privileging of masculinity and femininity, but scholars rarely measure these concepts directly, instead relying on variables that capture various forms of sex inequality, such as women in parliament, fertility rates, or female labor force participation, among many others, as well as a range of indices that have been created (and critiqued and occasionally abandoned) by scholars and policymakers in recent decades.Footnote 26 Each measures different concepts, yet they are often used interchangeably. In effect, not measuring the status of femininity relative to the status of masculinity means that much of the quantitative literature claims to evaluate theories of gender inequality but in practice evaluates theories of sex inequality.

However, a standard set of sex and gender inequality measures would not resolve these problems.Footnote 27 Instead, measures must be aligned to the specific context and concepts—and this is likely to vary dramatically depending on the theoretical mechanism, and even on the country context. For example, the book by Hudson, Bowen, and Nielsen presents a new, comprehensive, and theoretically justified measure for testing the authors’ theory about patriarchy. But their measure may be less useful for exploring other facets of sex and gender inequality. More broadly, the move to the micro level suggests that it is counterproductive to strive for a single measure.

In addition, studying how gender affects war implies different questions than studying how sex affects war. A theory about sex and war might evaluate how increasing women's inclusion in different policy leadership roles, such as minister of defense, affects war and peace. A theory about gender and war might analyze how a particular state's prioritizing masculinity over femininity affects decision making around war and peace. The significance of the conflation, both theoretically and in measurement, should not be underestimated; it is akin to conflating Kantian norms of democracy with audience costs when evaluating theories of the democratic peace.

Beyond theoretical and measurement errors associated with using sex to measure gender, many feminist scholars argue that studying sex as a category is problematic. The category “women” is not a monolithic group; some standard proxies reflect a small subset of elite women, while others may reflect a broader set of conditions faced by only some women. Feminists argue that the use of this category homogenizes women according to the characteristics, beliefs, and narratives of the dominant or majority women in that society.Footnote 28 In creating the categories and assumptions about what it means to be a woman, dominant narratives assume that all women (and all men) share the same preferences. In reality, there is great variation among women and men, including by race, ethnicity, economic status, religion, caste, political ideology, and other salient groups and identities.Footnote 29 Thus using women as a category reinforces gendered, raced, and other hierarchies within the broader social context because it assumes that all women are same, and ignores the hierarchy embedded within that category.Footnote 30

Finally, some scholars make the case that both sex and gender are immeasurable and cannot be captured by any quantitative proxy, and that by definition any dichotomy (feminine/masculine, male/female, etc.) fails to consider continuums.Footnote 31 In this view, sex and gender are co-constitutive of outcomes, including of each other,Footnote 32 as well as dynamic and constantly shifting. Individuals perform different genders (and sexes)—becoming, for example, more or less masculine or feminine—depending on the context.Footnote 33 The fluid and performative nature of sex and gender, as well as their co-constitutive relationship, means that there is no way to measure them accurately.Footnote 34 It also suggests that there is not a causal, unidirectional arrow that points from (sex or gender) inequality to war; rather, the relationships are highly endogenous. Despite these critiques, however, many feminist scholars see merit in the broader research agenda, arguing that “the question of whether states with more sex equality are more peaceful is worth exploring.”Footnote 35

Quantitative Critiques of Sex and Gender Inequality as a Cause of War

In contrast to the feminist IR literature, there is far less direct engagement or debate by quantitative IR scholars about sex and gender inequality and war. Its absence from many top political science journals and prominent quantitative work on the causes and consequences of war and peace suggests that the linkage is simply overlooked by many IR scholars;Footnote 36 sex and gender inequality variables are not standard in models of the onset of war.Footnote 37

Given the consistency of the correlation, why are these variables not regularly included in studies of war, much like variables that measure ethnicity and wealth inequality? Scholars have written voluminously about these other variables, resulting in a vast literature debating the effects of democracy, ethnic fractionalization, and economic development on civil war, for example. But even though sex- and gender-related variables are consistently statistically significant in regression analyses, no such equivalent literature exists, nor do most scholars appear to consider them principal factors. Only one of the two main textbooks on civil war includes a chapter on gender equality.Footnote 38 Graduate courses on international security do not regularly consider sex and gender inequality as predictors of war. Beyond biases in what readings and topics instructors assign,Footnote 39 we highlight one methodological reason for overlooking sex and gender equality in the literature on the onset of war: causal identification.

Causal Identification

While some scholars present detailed theoretical arguments about why the correlation between sex and gender inequality and war is causal,Footnote 40 the empirical evidence—mostly using cross-national data—may remain unpersuasive for those concerned about causal inference. Neither biological sex nor gender can be randomized by researchers. In addition, skeptics are unconvinced that sex and gender inequality or their proxies can be usefully separated from per capita income, level of democracy, and ethnic fractionalization such that sex and gender inequality by themselves can be said to cause episodes of major political violence.Footnote 41 Moreover, recent studies have shown that war alters sex and gender equality,Footnote 42 raising concerns about reverse causation. The endogenous nature of the relationships makes it difficult to parse whether war causes changes in sex and gender equality or whether sex and gender inequality cause war.

These are all valid concerns, and ones that can be partially mitigated by following the lead of other communities of scholars studying challenging topics with similar endogeneity concerns.Footnote 43 Variables related to democracy and development raise similar concerns about endogeneity and yet have become standard variables for analysis. Issues of causal identification alone are insufficient to explain why mainstream scholarship has failed to embrace sex and gender inequality as key to violence.

Bridging the Divide on Sex and Gender Inequality and War: Two Ways Forward

With critiques from these two communities of scholars in mind, we highlight two ways to advance the research agenda. First, we argue that to better understand what specifically about sex and gender inequality might drive political violence it is important to focus on mechanisms—the precise causal chain—rather than the correlation itself. A shift to mechanisms paves the way toward more refined theories that can be tested using causal identification methods. Furthermore, focusing on mechanisms avoids the conflation of gender and sex, ensuring more accurate use of the concepts. Second, we advocate a greater focus on micro-level studies rather than macro, cross-national studies to better test the more refined theories. Micro-level research designs, where the unit of analysis is organizations or individuals, enable greater causal identification and offer more flexibility, allowing researchers to incorporate intersectional analysis.

Focus on the Mechanisms

Although studies have provided evidence of a link between different proxy measures of sex and gender inequality and war, many of these studies do not well explain why there is a link. Indeed, cross-national studies often do not detail why certain factors matter in the ways they do.Footnote 44 For instance, if a greater proportion of female parliamentarians is associated with a lower incidence of war,Footnote 45 why is this so?

Feminist theorists and recent quantitative studies on women's political and social conditions point toward several mechanisms through which sex and gender shape war; we highlight both contributions here. We argue that the seven books under review demonstrate that some mechanisms rely on the strategic use of sex and gender by political actors, whereas other theories are structural in nature (Table 1). While they vary in research design and level of analysis, we use strategy-versus-structure as the core division for categorizing the mechanisms that explore the links among gender, sex, and war.

Strategic Uses of Sex and/or Gender

Mechanisms that rely on strategy require that political leaders leverage women or gender to achieve political outcomes. While most of the literature does not explicitly employ a strategic framework, applying one illuminates possible mechanisms at play; two books and several foundational quantitative articles demonstrate the role of political strategy.

First, some of the original studies linking women to war in the cross-national, quantitative scholarship suggests that women's inclusion in politics, particularly in the legislative rather than the executive branch, leads to more peaceful outcomes.Footnote 46 The underlying assumption in this scholarship is that women tend (whether for biological or social reasons) to hold more peaceful beliefs, so the more women there are in politics, the more peace there will be; women will dampen tendencies toward aggressive uses of military force. Yet, many questions and criticism emerge from this assumption, such as: how many women are needed, and in which types of leadership roles, to effect this shift toward dovish policies? Can women “behave” like women—that is, is performing femininity even possible for women—in masculine national security spaces? And how are sex and gender conditioned by competing identities, like race, ethnicity, political ideology, or class?

These questions and critiques led scholars to move beyond intrinsic qualities of women and men to different explanations for how women influence politics: mechanisms of political strategy. A number of arguments emerged from these initial studies. For example, one explanation for why intrastate and interstate conflicts decrease when women are leaders is that opponents perceive female leaders as more credible.Footnote 47 In contrast, others have argued that women may feel pressured to perform masculinity and thus initiate conflicts as a way to signal their political viability.Footnote 48 In addition, due to stereotypes, women may incur higher “inconstancy costs” for backing down from a conflict; it signals to their opponents that women are indecisive.Footnote 49 Others have theorized that opponents are more likely to attack if they are facing off against a woman because they do not want to appear weaker or more docile than their female opponent.Footnote 50 These studies suggest ways that political leaders might make strategic political decisions based on gender stereotypes about women.

However, women do not have to be leaders in politics to influence decisions about war. Political leaders need votes and public support to remain in their positions. When women become a part of the electorate, their beliefs and preferences become salient to political leaders. On issues where there are significant differences between men's and women's preferences, political leaders must take this sex gap seriously. Scholars note that the difference in men's and women's preferences over war is the “largest and most consistent policy gender gap in public opinion polling.”Footnote 51 Eichenberg's Gender, War, and World Order presents the most comprehensive analysis of the so-called gender gap (more accurately, and hereafter, the sex gap) in public opinion about war, highlighting how women are less accepting of war, particularly in the US and Europe. He argues that the sex gap in support for war is as consistent as it is consequential for security. In his view, and echoing an earlier argument by Fukuyama, women in public audiences are the main constraint on leaders’ use of force, an under-studied factor in theories of the democratic peace.Footnote 52 Eichenberg predicts that as more women gain power and take up powerful political positions, there may be less war between states because women will shift the consensus toward less violent policy solutions.

Using historical data, Barnhart and coauthors similarly argue that women's suffrage reduced states’ likelihood of war because women's preferences about war influenced policymaking when women became voters. The authors find strong evidence of a sex gap in opinions about war, and suggest that this difference between men and women drove the public policy of political leaders, as leaders needed to gain the support of this new constituency. According to this view, when women gain suffrage, they change the incentives of elected politicians, forcing them to become more responsive to issues that they perceive women care about. But women also change the political leaders themselves, by voting for candidates who more closely align with their preferences. War occurs when public opinion is more concentrated along the preferences of men, and peace is more likely when these preferences are diluted by women entering the electorate.

While both Eichenberg and Barnhart and colleagues are careful to avoid assuming that women are inherently peaceful, neither disaggregates the broad category of “women,” nor evaluates which women's opinions matter to political leaders.Footnote 53 A refinement of the mechanism that incorporates intersectional analysis would be to limit the scope of the argument: when the sex gap in public opinion regarding war is between dominant/majority women and men, then political leaders might be less inclined to go to war, assuming that the contingent of dominant women is large enough to be salient to political leaders. An intersectional analysis could also analyze whether and how the opinions of minority women influence political decisions.

Politicians are not the only political actors to strategize about women's role in politics. Nonstate actors, including rebel groups, must also consider whether women's inclusion is strategic for their broader political goals.Footnote 54 Wood's book Female Fighters presents a theory of how rebel leaders balance competing demands to fill their ranks with available recruits, including women, while also being careful about violating local social norms about gender and violence.Footnote 55 According to Wood, the recruitment of women into rebel organizations is the result of savvy strategic planning for two central goals: to mitigate labor shortages, and to appeal to international audiences, who are more likely to empathize with the grievances and goals of the group when women are members. The strategic use of women by rebel groups is apparent in other recent work that analyzes images of women in rebel propaganda. Loken finds that images of armed mothers help rebel groups navigate the competing pressures to use women to increase legitimacy for the cause and to avoid alienating potential supporters by humanizing women's roles and suggesting that their taking up arms is but a temporary respite from traditional caretaking roles.Footnote 56

Wood focuses more on the demand side of why rebel groups recruit women and less on the supply side of why women seek to join such groups; a brief discussion emphasizes that women have similar motivations to men. This is a reasonable scope condition, but it limits the ability to understand the full complexity of how particular forms of sex inequality may make women more likely to seek to join a rebel group, and in turn, how the women who join rebel groups inform the ideologies that such groups decide to employ. A focus on the demand side also implicitly places the agency for strategic decision making more on rebel group leaders than on the women fighters themselves. Leaders may have strategic reasons to recruit women, but women also have strategic reasons to join.Footnote 57

Political groups and organizations are strategic not only about leveraging sex but also in how they leverage gender. At first glance, Ellerby's No Shortcut to Change does not appear to be a book about political strategy. However, a closer reading reveals that her argument is about how international organizations (IOs) avoid the promotion of gender equality globally. Much of the work of IOs is to promote sex equality—the status of women—because this aligns with the liberal order. A feminist understanding of gender equality would mean dismantling some of the structures that uphold the core tenets of liberalism.Footnote 58 In this view, feminist scholars argue, liberalism and liberal ideas such as women's rights can contribute to the structures and systems that subordinate women.Footnote 59

As Ellerby argues, women-centered policies do little to disrupt and challenge gender hierarchies (“ranked patterns of masculinities and femininities”) or to facilitate substantive equality between genders, which she defines as valuing masculinity and femininity equally. Ellerby's study looks at the political process of how “gender equality” came to be a “catch-all” phrase for any policy meant to address discrimination against and exclusion of women, and a “‘shortcut’ expression, a way to acknowledge the socially produced, differently valorized realities of men and women, without the deeper critical analysis explaining why such realities persist.” She demonstrates how IOs’ policy agendas on women are often cloaked in the language of gender equality, but avoid challenging the status quo regarding gender. In this way, IOs take a “shortcut” to promote gender equality by limiting their efforts to promoting the status of (often majority) women. The solution, Ellerby argues, is a shift to a more limited use of the term “gender equality,” to be applied only when policies go well beyond simple inclusion. This shift would more accurately reflect what gender equality policies should strive for, and would offer a return to gender equality in the original feminist understanding.

Because the book does not directly consider the strategic decision making of IOs, Ellerby does not explore why they take these shortcuts. Moreover, she does not extend her critique to the quantitative literature on sex and gender inequality and war. Nevertheless, these decisions have significant repercussions for international politics, and they suggest that only when gender equality is accurately understood by policymakers can there be changes to make gender equality more of a reality. One implication of this argument is that if there is indeed a link between gender inequality and war (and not merely sex inequality or women's unequal status and war), then policies intended to improve women's status will have little effect on the prevention of war.

While Ellerby highlights how shortcuts occur at the international and state levels, decisions to focus on sex and not gender also happen at the organizational and individual levels. IOs use gender—or ideas about what qualities and attributes constitute men and women—to make life-and-death decisions.Footnote 60 For example, humanitarian organizations make strategic determinations about how to triage humanitarian evacuations—which noncombatant individuals get rescued and which do not. Carpenter argues that because these organizations understand women and children as inherently vulnerable, “presumptive innocents,” leaders face pressure to “save” women and children, but not men. The move to privilege women and children is not because they are more likely to die; in reality, men are most prone to succumb to lethal violence during war. But civilian men are rarely evacuated because they are perceived as “presumptive combatants.” The powerful gender norms of who is vulnerable are perpetuated through transnational advocacy organizations, which recognize and harness the power of highlighting vulnerable women to donors and policymakers for their own strategic ends.Footnote 61

Organizing the research on gender, sex, and war around political strategy opens the door to developing innovative mechanisms and testing them using novel research designs that might have been overlooked in the quantitative literature. Although Ellerby's book is not framed as strategic, doing so introduces new research designs that could, for example, experimentally evaluate whether or not IO personnel privilege the rights of dominant women over gender equality, and whether personnel in humanitarian organizations have sexed, gendered, raced, or other biases with respect to victimization. But strategy is only one lens to understand the roles of sex and gender; we turn next to structural explanations.

Structural Accounts of Sex and/or Gender

Structural mechanisms that link women, gender, and war include cultural explanations as well as institutional and event-based arguments. These mechanisms lack an actor making rational decisions, instead relying on the reinforcing nature of culture, institutional arrangements that emerge from historical precedent, and “critical junctures.”Footnote 62

In Gendering Global Conflict, Sjoberg argues that war cannot be understood without the use of gender as a primary analytical category, including the consideration of sex, gender, and what she calls “genderings,” the application of perceived gender tropes to social and political analyses.Footnote 63 Within this framework, Sjoberg highlights the mechanism of hegemonic militarized masculinities, the process of remaking ordinary men into soldiers, which relies on reifying gender roles.Footnote 64

Sjoberg's book exemplifies a feminist theory of gender and war, which acknowledges that when masculinity is privileged over femininity, masculine methods for handling conflict are also privileged. Although there are many masculinities, only some forms of masculinity become dominant, or hegemonic.Footnote 65 In particular, Sjoberg argues that under certain circumstances—periods of heightened nationalism or threat—militarized masculinity, the idea of a “male hero soldier,” becomes the dominant narrative.Footnote 66 Hegemonic militarized masculinity means that the markers of militarized masculinity—toughness, responsibility for protection, assertiveness in decision making, and the importance of maintaining reputation—become the standard for what it means to be “a man,” and are valued above all other characteristics.Footnote 67 States’ hegemonic masculinities shape their strategic cultures, which in turn shape leaders’ strategic decisions. Leaders, for their part, strive to perform this masculinity, and their security decisions are influenced by the adoption of this identity.

In contrast, the idealized feminine traits of women are docility, honor, and caregiving; it becomes the responsibility of the woman to take care of the household and the homeland while the men are fighting in war. In this way, women become the “mother” of the nation, and it is the job of the “good soldier” to protect her.Footnote 68 Creating and sustaining these gender roles enables the state to overcome the collective-action problem, providing both the justification (protection of the motherland) and the resources (men's bodies) to engage in warfare.

A related cultural explanation relies on the idea of honor. Melander suggests that men are socialized into and identify with a definition of masculinity that stresses the necessity and honor of violently defending one's name, the interests of the group, and the nation.Footnote 69 To avoid being viewed by other men as feminine, men must prove their masculinity through violence. These arguments are echoed in research in psychology on “precarious manhood” that has found that manhood must be “earned and maintained through publicly verifiable actions.”Footnote 70 For aristocrats in early modern Europe, this meant engaging in duels; in countries around the world today, it may mean performing honor killings. According to Bjarnegård, Brounéus, and Melander, honor ideology has two dimensions: patriarchal values, a measure of the desire to control female independence and sexuality; and masculine toughness, the perceived necessity for men to be fierce and respond to affronts with violence or threats of violence to preserve their social status. The authors find that men who express strong support for the values of honor culture (such as control over female sexuality and the need to respond to even minor insults with physical violence) are more likely to have been violent during political protests in Thailand.Footnote 71

In addition to cultural explanations, scholars have theorized specific mechanisms about sex inequality and war that are institutional in nature, focused on the organizational structure of societies.Footnote 72 The analysis of social ordering and sex inequality is perhaps the most important contribution of Hudson, Bowen, and Nielsen's book. As suggested by the title, their theory centers on “the first political order,” which the authors define as the sexual political order in which the subordination of women at the household level, often through violence and coercion, sustains violent kinship networks. The “first difference”—the different body structures between men and women, including upper body strength, height, skeletal mass, and muscle mass—give men, on average, an advantage, in that they can relatively easily physically coerce women. But they can coerce other men as well, and thus a security dilemma emerges, wherein men must form groups to ward off attacks from other men. The all-male alliance of kin survives, the authors argue, because of mechanisms of identity reproduction in the form of the “patrilineal/fraternal syndrome,” which enables kinship bonds to sustain themselves through coercion over women. The authors show that the syndrome, a set of eleven distinct practices that allow men to form security alliances with each other while simultaneously subordinating women,Footnote 73 is associated with a wide range of political and social ills, from political violence—our main concern—to poor economic performance and health outcomes.

Some of these arguments build on earlier work that similarly relies on evolutionary theory to suggest that social ordering in the form of clan or national identity is almost exclusively defined by men, who decide who is a member of the in-group and who is relegated to outgroups.Footnote 74 A theme throughout Hudson and her coauthors’ body of work is that same-sex groupings of men tend to emphasize and enforce women's differences and perceived inferiority, which are used to justify objectification and dehumanization.Footnote 75 Their quantitative analyses have demonstrated that violence against women is a stronger correlate of violent outcomes than the level of democracy or wealth.Footnote 76

The theory of the patrilineal/fraternal syndrome is ambitious in its global and historical sweep. But this comes at the cost of explanations of particular mechanisms for what might be thought of as separate micro-theories to explain particular forms of violence, distinct from the umbrella of the larger theory. For example, The First Political Order includes a chapter on disruptions of the marriage market as a cause of violence (and many other consequences—see their Figure 5.2). Like Hudson's and her coauthors’ previous work on the topic,Footnote 77 the argument is that shortages of women in the marriage market create “bare branches”—men who are unable to marry and fulfill masculine expectations for adulthood. These men are then targeted to be recruited by violent groups or otherwise enticed into a violent life. The bare branches theory posits that shortages of women in the marriage market, whether through infanticide (of girls), sex-selective abortions, polygamy, or high bride prices, leaves many men idle and available to be recruited into violent activity. In The First Political Order, the bare branches micro-theory is woven into the macro theory as a consequence of the first political order, and of the patrilineal/fraternal syndrome. But whether there are other plausible pathways to obstructed marriage markets is not considered. A grand theory of the sort presented in The First Political Order is commendable; however, by design it limits the exploration of other possible micro-mechanisms and the testing of competing mechanisms against one another.

The important project of theorizing about precise structural mechanisms has been taken on by several scholars who specify the causal chain through which gender inequality (or other measures related to sex inequality) and war may be linked.Footnote 78 Forsberg and Olsson highlight three mechanisms through which “gender inequality can affect armed conflict.”Footnote 79 In the “norms mechanism,” sex and gender inequality provide the foundation for norms about the use of violence as legitimate to address conflict. Another mechanism is “societal capacity,” in which greater investment in women produces stronger social networks and more resources, enabling the society to handle conflicts more peacefully. Finally, the “gendered socioeconomic development mechanism” makes young men unavailable for recruitment into armed groups because they are occupied by work and marriage. The authors find that the latter two explanations best explain trends in political violence in India.

Structural Changes as Cause for Sex and Gender Equality

To fully consider the possible causal chains, we must also investigate the mechanisms that link war to exacerbating or ameliorating sex and gender inequality. For example, rather than being an exclusively destructive force, might war serve as a critical juncture for sex and gender equality?Footnote 80 Drawing a pessimistic conclusion, Sjoberg argues that war leads to a tightening of the regulation of traditional gender norms; as gender roles become compounded, women must assume more formal and informal labor, and men are required to fight in the war effort, often risking death.Footnote 81

However, two of the books under review provide mechanisms for how this structural change (war) creates new opportunities for women and reshapes gender relations, potentially leading to improvements in life conditions.Footnote 82 Both rely on the mechanism of political opportunity to disrupt gender relations and to create space for women to assume new gender roles. Tripp maintains that major political violence—especially the most brutal forms of widespread and longer-term wars—leads to “gender regime change.” Similarly, Berry finds that mass violence allows rapid social change that reconfigures gender power relations and increases formal and informal political participation.

Tripp's book, Women and Power in Post-Conflict Africa, provides the most comprehensive theory for why there may be large increases in women's rights and inclusion after major civil wars end, as was observed in sub-Saharan Africa in the 1990s. Tripp argues that these countries experienced such changes due to a wide range of political opportunities that opened up in the region as a result of civil wars. War accelerated the progression of women's inclusion and rights, not merely through greater opportunities for women following the war-related deaths of men, but also because war itself disrupts traditional gender relations. First, she posits that lethal and longer wars require women to assume new responsibilities, placing them in roles traditionally occupied by men. Second, how wars end matters: civil wars ending with a negotiated settlement create more political opportunities for women, by allowing women to participate in negotiation, mediation, and the postwar reform process.Footnote 83 Civil war terminations in Africa were followed by periods of liberalization and democratization, including the creation of new constitutions. Along with heightened women's activism—the emergence of local women's groups, supported by transnational women's movements, and international actors such as the United Nations—during the democratization period, these new constitutions often included reforms for women.

Berry makes a related argument but focuses on how war creates avenues for different types of women's political participation. In War, Women, and Power, Berry argues that war leads to the loosening of traditional gender power relations through three types of shifts: demographic, due to disproportionate deaths among men; economic, due to the destruction of infrastructure and agriculture and the arrival of humanitarian aid; and cultural, enabling women to become public actors. These three changes enable women to engage in a wide array of new roles, increasing participation in informal or “everyday” politics, including seeking aid from NGOs and government, and lobbying officials for their rights.Footnote 84

Under some conditions, this political participation becomes more formal; similar to Tripp, Berry shows that the installation of new gender-sensitive political regimes allows women to participate in politics as legislators and even as heads of state. However, a new “gender-sensitive regime” occurred in Rwanda but not Bosnia. While Rwanda saw the highest percentage of women in the legislature in the world, at over 63 percent in 2013, Bosnia reached a high of only 21 percent in 2014. Berry attributes this difference to the Rwandan government's incorporation of women's movements into the government.Footnote 85 Here, the structural explanation could intersect with strategic explanations. War might create political opportunities for women to enter politics, but political leaders incorporate women for strategic reasons: to increase their vote share and to enhance their legitimacy in the eyes of domestic and international audiences.Footnote 86

While both Tripp and Berry offer persuasive arguments for how war creates opportunities for women's political participation, neither addresses whether sex or gender inequality led to war in the first place, or whether it might do so in the future. They might have concluded, for example, that with more women serving in influential political positions and broader women's rights, a return to war or the onset of future unrest is less likely. Moreover, because both are situated in the comparative politics literature, neither author explicitly incorporates the IR literature on sex and gender inequality and war, missing an opportunity to theorize the endogenous cycle of women's political and social conditions and violence.

One question that remains is whether these gains endure. New research provides a rigorous, quantitative exploration of how war, whether interstate or intrastate, affects women's empowerment in the short, medium, and long term.Footnote 87 Webster, Chen, and Beardsley provide an explicit discussion of the endogenous nature of women's empowerment.Footnote 88 They find that intrastate and interstate wars are associated with fairly short-lived changes in women's political empowerment, up to five years after the war concludes. Longer, protracted wars are more likely to produce immediate changes in women's empowerment, and the effects are strongest for interstate wars.Footnote 89

Berry's comparison of Bosnia and Rwanda sheds light on three impediments to long-lasting change.Footnote 90 First, political elites and international actors involved in the postwar peace-building and state-building efforts privilege certain women over others, creating hierarchies of victimhood and fracturing women's solidarity and organizing.Footnote 91 Second, international actors ignore local grass-roots initiatives, which impedes women's organizing. Finally, women's gains challenge the prewar hierarchy of male privilege, inciting violent patriarchal backlash such as domestic violence, harassment, or targeted political violence.Footnote 92

Taken together, these studies suggest that there are conditions and limits to women's gains after war. Women may even begin to be targeted because of their newfound empowerment, suggesting that patriarchal structures are not dismantled during war, only briefly shifted. Further, some of these inequities could become entrenched due to backlash, which could in turn increase the probability of renewed conflict—another reason that war may beget more war.Footnote 93 The recent turn in the quantitative scholarship to disaggregation of mechanisms helps prevent scholars from conflating gender and sex, instead theorizing each separately. By specifying and testing individual mechanisms, scholars can select the most accurate variables to test different theories. Moreover, parsing mechanisms allows scholars to generate plausible, competing hypotheses and to seek creative ways to test them, including better addressing causal identification. Finally, a turn to mechanisms enables scholars to test particular aspects of what feminists have identified as the co-constitutive nature of sex, gender, and war. Testing mechanisms presents an opportunity to develop and test multiple arrows leading in different directions within the categories of gender, sex, and war.

Shifting the Unit of Analysis

The move to better identify and study mechanisms also means a shift in the research designs used to test hypotheses. The IR literature has experienced a turn toward the subnational, group, and individual levels to better elucidate and test the micro-foundations of theories.Footnote 94 As Kertzer argues, “many of our theories in IR … rest on lower-level mechanisms [but] they either leave these assumptions unarticulated or fail to test them directly.”Footnote 95 The IR research agenda on sex and gender inequality and war could usefully follow in the footsteps of adjacent fields, where significant advances have been made on mechanisms through disaggregation to the subnational and micro levels. For example, research on the prosocial legacies of war has analyzed data at the subnational, household, and individual levels in postwar contexts, and has used behavioral games to understand the underlying mechanisms.Footnote 96

From Cross-National to Subnational

The seven books under review use a variety of levels of analysis. Three rely in part on cross-sectional analyses, two at the country level (Hudson, Bowen, and Nielsen; Tripp) and the other at the group level (Wood), all of which are also susceptible to criticisms related to causal inference. In The First Political Order, while the patrilineal/fraternal syndrome begins with beliefs formed early in life based on experiences in the household, these beliefs are not directly measured or tested. Instead, the authors point to the consistency of their measure of the patrilineal/fraternal syndrome across a whole host of dependent variables, as well as a vast literature that supports their claims. A fruitful path for future research would be to build on this work to conduct analyses at the subnational, group, or individual level.

Some of the books under review have made the turn to subnational-level analysis, illuminating important dynamics that would have been obscured in country-level studies.Footnote 97 Tripp uses process tracing in three countries—Uganda, Liberia, and Angola—to assess whether variation in disruptions due to civil war, women's movements, and the spread of international gender norms via international actors such as the United Nations led to changes in a “gender regime,” or greater women's rights and inclusion in politics.Footnote 98 If any of these three factors (civil war, grass-roots women's movements, or international efforts) are missing, Tripp hypothesizes that there will be fewer positive changes in women's rights and inclusion. The case design allows the use of a “hoop test,” or assessing the conditions that are necessary but not sufficient for improvements in women's rights and inclusion. Tripp argues that the case design method enables causal inference because she examines whether the causal factors were present in the cases, whether the causes are clearly linked to the outcome, and whether competing hypotheses can be eliminated.Footnote 99

In War, Women, and Power, Berry uses a most-similar case design to look at Rwanda and Bosnia.Footnote 100 Her approach is one of “feminist historical institutionalism,” in which she strives to explain large-scale structural shifts and critical junctures by assessing the causal processes and mechanisms that led to changes. This approach allows causal claims because it asks about “possible outcomes at every stage of the event trajectory, engaging in counterfactuals and expecting contingencies.”Footnote 101

Much more of this type of subnational work could be done by future researchers, often with readily available data. For example, Forsberg and Olsson turn to the subnational level in India, where they examine the influence of sex ratios, fertility rates, and labor force participation on war.Footnote 102 They analyze the correlations between a range of indicators in all districts in India over a twenty-five-year period. The correlations found in this work echo others’ cross-national results.

Moreover, subnational analysis provides researchers with greater knowledge about the country under study. Detailed knowledge about cases (such as subnational units of countries) could point to a natural experiment or an instrumental variable. For example, Bjarnegård and coauthors use the military draft lottery system in Thailand as a natural experiment to assess the effect of militarized masculinity.Footnote 103 The lottery randomized men's entry into the military, creating a causally identifiable way to measure whether the military socializes recruits.

A focus on the subnational level has many benefits. Subnational studies can hold constant many factors that vary between states, while still allowing scholars to exploit variation in the variables of interest—in this case, levels of sex and gender inequality and types of political violence. Such studies also make it more possible to identify additional mechanisms that connect the two sets of variables. However, such work is unlikely to persuade those who remain concerned about causation. To assuage those concerns, scholars ought to consider survey data and experimental methods.

From the Subnational to the Individual Level

The turn to the micro level enables a close examination of some of the mechanisms mentioned earlier. For example, to test the mechanisms undergirding the strategic argument requires understanding variation in public opinion among men and women about war, as well as the shortcomings of such studies. It also requires understanding how public opinion changes with women's inclusion in (state or rebel) violent groups.

The public opinion literature on the sex gap in support for war mostly treats women's lack of support for war as a universal truth. As Eichenberg argues, this literature is limited in scope by the available data. Most audiences that have been polled about war support are in the global North, in countries that lack direct recent experience with war, and have answered questions mostly about major war rather than conflicts short of war.Footnote 104

While Eichenberg finds differences based on the type of force used, a recent study on the topic finds overwhelming evidence for the sex gap. A sweeping meta-analysis of a series of experiments that randomize the use of force by country leaders using representative samples of different national populations concludes that support for the use of force is consistently higher among men than among women.Footnote 105 Meta-analysis is an innovation with great promise for future research; nearly every survey source includes data on men and women's preferences.Footnote 106

The sex gap raises a puzzle about why more women don't support war, given that it can bring about immense changes in their rights and inclusion. If conditions for women can improve after war,Footnote 107 and women rarely directly serve as combatants, isn't it rational for women to support war, or at least to support it as much as men do? This critical question of why women have differences in opinion from men has been theorized and explored empirically by only a few scholars.Footnote 108 For example, in a series of survey experiments on gender and foreign policy, Brooks and Valentino find that the sex gap disappeared when the stakes of the war were humanitarian in nature, or the war effort was endorsed by the United Nations.Footnote 109

Moreover, little is known about the origins of the gap, and scholars have urged others to more fully explore the sources.Footnote 110 Some recent research provides preliminary findings that can guide future work. First, a survey in Port au Prince, Haiti, suggests that the sex gap is shaped by perceptions of the relative costs and benefits of war for men and women. When respondents were told that war may benefit women politically, the gap disappeared: men's support decreased while women's support increased.Footnote 111 Second, in a survey experiment across five countries—Lebanon, Jordan, Indonesia, Mongolia, and India—support for polygamy depended on the first wife's opinion of polygamy. If the first wife was supportive, then respondents were more likely to be as well.Footnote 112 This suggests that women's views may be conditional on their perceptions of what other, higher-status women think.

Finally, a key insight may lie in the possibility that it is a gender gap (differences in degrees of masculinity and femininity), not a sex gap (differences between men and women); in other words, taking seriously that public opinion is shaped by gender identities and beliefs. For instance, gender gaps can be measured by using standard data sets that contain relevant questions about feminist attitudes.Footnote 113 Bjarnegård and Melander use survey data from the Pew Global Attitudes Project for four Asian countries (China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea) and the US.Footnote 114 They find that both men and women who espouse views that support gender equality are less likely to express hostility to other countries or to religious minority groups (Jews, Christians, and Muslims) in their own country. Furthermore, using a nationally representative study of US citizens, Wood and Ramirez find that individuals (regardless of sex) with more egalitarian views about gender are less likely to support the use of force (even controlling for education, race, age, religion, and many other factors) and that this is especially strong among male respondents, effectively closing the sex gap.Footnote 115 Eichenberg focuses on personal perceptions of vulnerability, which are likely gendered: feminine men, for example, might fear for their safety too. These studies indicate that the source of the “gender gap” in support for war is not biological sex, but rather attitudes about certain forms of masculinity—an argument feminist scholars have made for years.

While there are few standardized questions about gender or even beliefs about women in political science, a few scholars have begun to import measures from other fields.Footnote 116 In her book on sex and American political behavior, McDermott uses the Bem sex role inventory, commonly used in psychology, to map respondents into four ideal types based on self-reported sex traits: feminine, masculine, androgynous (scoring high for both femininity and masculinity), or undifferentiated (scoring low for both femininity and masculinity).Footnote 117 Importantly, individuals of either sex can be masculine or feminine, with significant variation in these scales. Future research in IR could use the Bem sex role scale to hypothesize and test ideas about sex, gender, and public opinion.

In addition to its use in studying the sex and gender gap, the turn to individual-level survey data helps scholars better understand how women's inclusion affects strategic group behavior. As previously argued, leaders often include women for strategic reasons. Wood's book, Female Fighters, shifts the unit of analysis to the individual level using a survey experiment that analyzes the effects of female fighters on external audience perceptions of an armed group, differentiating the book from other studies of women rebels.Footnote 118 The inclusion of women in rebel groups shifts respondents’ attitudes toward greater support for the rebels. Rather than demonstrating correlations at greater levels of aggregation and assuming that these reflect individual preferences, evidence from survey experiments can directly reveal the individual preferences at the foundation of these theories.

In sum, one of the most promising ways forward will be the use of surveys to gather micro-level evidence from individuals, and survey experiments to identify and test the underlying mechanisms. Surveys can be used to analyze (1) correlations between individual respondents’ characteristics and self-reported attitudes about gender equality, and (2) correlations between individual respondents’ characteristics (such as beliefs about conflict resolution, foreign policy, the use of force, and self-reported participation in acts of political violence) and political violence outcomes.Footnote 119 Meta-analyses of surveys from different countries around the world aggregate findings, shed light on generalizability, and provide leverage for the external validity of mechanisms. Survey experiments can be used to uncover biases regarding gender, and are particularly useful for biases that are sensitive to report outright.Footnote 120 Finally, hypothetical scenarios can illuminate conditions under which different respondents view violence as an appropriate solution to political problems.Footnote 121

Experiments

Another fruitful path for future research is the move to conduct experimental work on the relationships between women and political violence at both the individual and group levels. There are at least three options for experimental studies to understand the mechanisms that connect women, gender, and war: priming, lab experiments, and field experiments (including randomized controlled trials).

First, scholars can use survey experiments to prime gender identities and see what effect they have on preferences for violence. Primes could focus either on gender conformity or on the hierarchical nature of gender identities. For the former, survey experiments might randomize male or female agents performing a feminine or masculine task to better understand how strongly respondents adhere to gender stereotypes. In the latter, primes might elicit the relative importance of performing masculinity. For example, a recent survey conducted in several countries asked male and female police officers and military personnel to rate their masculinity/femininity.Footnote 122 The treatment then included a statement by the enumerator to the respondent that their score was above, the same as, or below the average, priming a sense of hypermasculinity (if told they scored above the average) or emasculation (if told they scored below the average).Footnote 123 Subsequent questions asked about the appropriateness of the use of violence, allowing researchers to test whether the prime led to changes in beliefs.

Second, experimental methods can also be used to conduct lab experiments or lab-in-the-field experiments. In a series of studies with the Liberian National Police, scholars have examined how the sex composition of groups affects group behavior. All-women groups are not more or less collaborative than groups that include men; rather, when men are outnumbered by women, groups’ behavior becomes slightly more hostile.Footnote 124 These techniques can also be used to test micro-level mechanisms that explain whether escalation is more likely against certain types of elites. In such a study, researchers would randomize the gender and/or sex composition of players to see whether playing against (masculine/feminine) men or (masculine/feminine) women affects escalation. Incorporating an intersectional lens, one could vary the racial/ethnic identity of the elites as well.

Finally, field experiments offer an opportunity to better understand whether women help legitimize state institutions in the aftermath of war. For example, experiments in the field can reveal how individuals react to women as agents of security. One study assessed how civilians respond to female versus male police officers, finding that negative perceptions of police violence declined with visits by police officers of either sex.Footnote 125 Karim concludes that future experiments ought to include at least four treatment arms—feminine women, feminine men, masculine women, and masculine men—to understand how beliefs and behavior about violent and nonviolent conflict resolution change when individuals are exposed to any of these four types of security agents. Other field experiments might randomize programs aimed to mitigate the more toxic elements of hypermasculinity and determine whether this makes a difference in participants' involvement in violent or nonviolent activities.Footnote 126

Overall, the turn to the micro and subnational levels helps address some of the feminist critiques mentioned earlier, as well as critiques from quantitative scholars. Micro-level analysis ensures that researchers are careful about the use of sex or gender because they do not have to rely on available proxy measures or fixed indicators to test theories. They have more flexibility in selecting a research design that tests the appropriate concepts. Moreover, micro-level studies help better account for intersectionality, by enabling a more complete understanding of how individual identities and beliefs about identities shape behavior.Footnote 127

In terms of the quantitative critiques, micro-level studies can at least partially address concerns about causal inference. Causal inference is easier to implement when the unit of analysis is at the subnational, group, or individual level. Researchers cannot randomize gender equality or women's rights across different countries, but as the unit of analysis becomes smaller, the researcher can leverage fine-grained data and the opportunity to implement a more rigorous research design.

Conclusion

We conclude by returning to the initial question: does more equality for women mean less war? The authors of all seven books would likely agree that under certain conditions, sex and gender inequality can serve to increase the likelihood of war, and that under certain conditions, war can either ameliorate or worsen (some forms of) sex and gender inequality. Taken as a whole, these findings caution against simplistic associations, and create an opportunity for analyses that take seriously the roles of sex and gender in fundamental questions of international security, including the causes and consequences of war.

While feminist IR scholars and scholars who use quantitative methods challenge core statistical associations linking sex and gender inequality to war, we have highlighted two important avenues for a renewed research agenda that mitigates many of these collective concerns. These include focusing on the strategic and structural mechanisms that underlie the central correlation between sex and gender inequality and war, rather than the correlation itself, and shifting from cross-national analyses to the micro level to study individuals and groups.

Paying close attention to mitigating the critiques from both feminist theorists and quantitative scholars will allow the research agenda to move forward from where debates have stalled. While the nexus of sex and gender inequality and war is undoubtedly challenging to study, quantitative scholars of international security ought to engage more directly with questions of sex and gender. To do so will enliven our theoretical debates and enrich the policy discourse with robust evidence.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Matthew Evangelista, Valerie Hudson, Sarah McLain, Laura Sjoberg, Elisabeth Wood, Reed Wood, and the IO reviewers and editors for feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript.