With the future of liberal internationalism in question, how will China's growing power and influence reshape world politics? The question of whether a rising China can be peacefully integrated into existing international institutions and norms is not new. Yet many studies have taken for granted the presence of a stable or liberalizing international order, one that the United States as the leading power would seek to preserve or deepen, rather than relinquish or dismantle.

New uncertainties about the willingness of the United States to support the Liberal International Order (LIO) have amplified anxieties over China's rise.Footnote 1 Some say that the system is resilient and will outlast a decline in US power because rising powers such as China have derived significant benefits from the LIO and can prosper within it,Footnote 2 as long as their economic aspirations are not stymied.Footnote 3 To the extent that participation in international organizations has socialized and habituated their participants,Footnote 4 rising powers such as China may strive for greater authority and rights within the LIO rather than overturning its core principles.Footnote 5

We argue that views of the LIO as integrative and resilient have been too optimistic, for two reasons. First, China's ability to profit from within the system has shaken the domestic consensus in the United States on preserving the existing LIO. As the LIO expanded after the Cold War, it grew to include many illiberal states.Footnote 6 But only China's rise has fused economic and security concerns about the consequences of letting an illiberal state prosper within the system. China's persistent illiberalism and growing military and economic power have helped call into question the adequacy of existing institutions, from the World Health Organization to the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Second, the literature has not adequately addressed how the rise of a nationalist, authoritarian power such as China will reshape the LIO, given the very different “social purpose,” identity, and institutions that characterize state–society relations in the People's Republic of China (PRC).Footnote 7 Both illiberal and liberal states, including the United States, have selectively chosen which international institutions to join and be bound to.Footnote 8 That variation, along with variation in the willingness of the United States and other core democratic members to champion the more liberal components of the international order, makes it difficult to summarize China's approach to international order as either “revisionist” or “status quo.”Footnote 9

In this article, we propose a research agenda for understanding how China's domestic characteristics infuse its international efforts vis-à-vis the rules, norms, and institutions of the existing order. Major features of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule include a prioritization of the state over the individual, rule by law rather than rule of law, and a renewed emphasis on ethnic rather than civic nationalism. These features chafe against many of the fundamental principles of the LIO, but could coexist with a return to Westphalian principles and markets that are “embedded” in domestic systems of control.

The LIO has always been less liberal in practice than in theory,Footnote 10 reflecting persistent tensions between liberal norms and the Westphalian emphasis on noninterference into the domestic affairs of sovereign states.Footnote 11 Rather than being a frontal challenge to the existing international order, greater Chinese influence will likely shift the international order in a more Westphalian direction, as Beijing continues to support the principles enshrined in the UN Charter of state sovereignty, equality, and noninterference, while circumscribing the liberal emphasis on individual political freedoms and movement toward more intrusive international institutions.Footnote 12

To illuminate the domestic parameters of China's interests and efforts across the variety of issues, norms, and institutions that make up the international order, we suggest and illustrate a framework that highlights two domestic variables: centrality and heterogeneity. In so doing, we sketch an agenda for researchers to examine where China's rise entails more incremental or more fundamental challenges to the existing international order.

The rest of this article proceeds as follows. First, we discuss the twin challenges that China's rise has posed for the LIO. Second, we present the implications of centrality and heterogeneity for China's international efforts across different issue areas, illustrated with examples of China's approach to climate change, trade and exchange rates, Internet governance, territorial sovereignty, arms control, and humanitarian intervention. Finally, we conclude by considering how the international order might evolve in the shadow of China's influence.

China's Rise and the LIO

Canonical accounts of the LIO were optimistic that rising powers such as China could be peacefully integrated into the system and discouraged from overturning it. As Ikenberry notes, the LIO was designed to allow “rising countries on the periphery of this order—to advance their economic and political goals inside it.”Footnote 13 As China joined dozens of international organizations and multilateral agreements, its behavior was also shaped by social pressures, helping explain Chinese cooperation even in the absence of obvious material benefits.Footnote 14 China's stature within these institutions was also expected to constrain and shape China's choices, encouraging Beijing to channel its grievances into “rules-based revolution” rather than a violent bid for hegemony.Footnote 15 Many officials who supported China's accession to the WTO argued that greater trade and economic interdependence would have politically liberalizing effects.Footnote 16

In our view, these accounts have given insufficient attention to the role of domestic politics, both in the rising state (China) and in the globally preponderant power (the United States). Centering the role of domestic politics leads to a more varied, and relatively less optimistic, set of expectations about China's rise and the future of the LIO.

A Shaken Consensus

Growing concerns about China's domestic and international trajectory have undermined support for continued engagement with China and institutional agreements that facilitated China's rapid economic growth. A surge in Chinese exports after its accession to the WTO helped fuel a backlash against globalization in developed democracies across the West, although scholars have debated whether economic hardship or perceptions of status threat was the dominant driver of electoral support for isolationist politicians.Footnote 17 In the United States, both Republican and Democratic officials charged China with unfair trade practices, poor compliance with WTO rulings, and exploiting open markets and scientific exchange to gain an advantage in next-generation technologies with national security implications.Footnote 18 China's persistent and increasingly personalistic form of authoritarianism led some in the US policy community to concede that China's increased integration had not produced greater political or economic liberalization.Footnote 19

The political cohort that took office under the Trump administration linked this disenchantment to broader attacks on the premise of the LIO.Footnote 20 Playing to widespread social, economic, and racial anxiety, Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election on a nativist, America-first platform.Footnote 21 In office, not only did the Trump administration seek to alter the bilateral trading relationship by levying successive rounds of tariffs on virtually all Chinese-made goods, it also moved to expand the set of commercial activities deemed a risk to national security, accused the WTO of showing favoritism toward China, and began “decoupling” the supply chains of the two countries. By invoking national security to restrict trade, blocking WTO appellate appointments, and withdrawing from a range of multilateral agreements on climate, arms control, health, and trade, the Trump administration mounted a frontal assault on the once-US-led international order.

Without reference to US domestic politics, theorists of liberal internationalism have difficulty explaining why the United States chose to undermine the best way to protect its values and interests even as China closed the relative power gap with the United States. Although recognizing that the leading state may not want to bind itself to rules that others do not follow, Ikenberry predicted that the United States as global hegemon would continue to invest in the LIO in order to create “a favorable institutional environment for the lead state as its relative power declines.”Footnote 22 Despite a wave of new research into the domestic sources of unraveling US support for liberal internationalism, these studies have not focused on concerns about China's rise.Footnote 23

Yet it is important to note that the US-led attack on the LIO was not an inevitable outcome but a choice by the Trump administration. A counterfactual US administration led by Hillary Clinton would have been more likely to use multilateral pressure and institutional levers to confront and constrain China, as the United States had under President Obama.Footnote 24 Indeed, bipartisan concerns over China's ability to flout the rules while maintaining other privileges within the international system suggest that different political coalitions could succeed in making the case for renewed US investment in multilateral leadership, with more stringent requirements on China should it wish to enjoy the benefits of access.Footnote 25 Alternatively, US policies to encourage firms and laboratories to decouple their supply chains and research efforts could herald a return to more closed or preferential economic blocs reminiscent of the Cold War.Footnote 26 In short, domestic coalitions, identities, and ideological beliefs matter in shaping the choices of the leading state.Footnote 27

China's Persistent Illiberalism and Tensions with the LIO

How do the domestic politics of an authoritarian state such as the PRC affect whether it seeks to engage or reshape the international order as it grows in power and influence? Do the CCP's ambitions extend beyond changing “the distribution of authority and rights” to challenging the “underlying principles of liberal order,” as Ikenberry asks?Footnote 28 At a basic level, the PRC is likely to follow the United States in privileging its own domestic interests and relative power within the global hierarchy.Footnote 29 Yet the PRC is undeniably different from the United States in a number of ways that put it at odds with core principles of the LIO.Footnote 30 On the one hand, the PRC has been a staunch defender of Westphalian principles of respect for territorial sovereignty as well as the UN charter, the principle of non-intervention, and the present configuration of the UN Security Council (UNSC). The PRC also helped shape, and ultimately signed on to, a more narrow conception of the “Responsibility To Protect” (R2P) principle authorizing international intervention to prevent genocide and crimes against humanity.Footnote 31 On the other hand, four characteristics of contemporary CCP rule are at odds with the LIO as a rules-based order that privileges democracy, free enterprise, and individual political freedoms.

First, the CCP has emphasized the role of the state over private enterprise, even though it was the introduction of markets and economic liberalization after Mao's death that unleashed China's economic miracle. China's brand of state capitalism—including subsidies, nonmarket barriers, and other preferential policies that have curtailed reciprocal market access—has been responsible for much of the international backlash against China's trade practices and participation in the WTO. China has also made financial, technical, and infrastructural assistance available to governments that do not meet the liberal political and economic conditions set by traditional lenders.Footnote 32

Second, the CCP has opposed the elevation of individual political rights and has regarded civil society organizations and transnational nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and activists with suspicion, fearing that they might challenge the CCP's domestic rule. In opposing the 1997 Ottawa Treaty banning land mines, for example, the Chinese government viewed the involvement of NGOs in the negotiation of a key document with distrust.Footnote 33 In the development arena, Chinese loans and grants have also sought to enhance state capacity. As one study of China's information and communications technology (ICT) investments in Africa noted, other donors typically select the most appropriate actors to advance a particular development objective, “be it a local NGO, a private company, or a specific ministry,” whereas China “has preferred an actor-based approach, seeking to increase the capacity of the state”—including the installation of AI-powered surveillance systems.Footnote 34

Third, the CCP has demonstrated a clear preference for “rule by law” over “rule of law.” Laws in China have proliferated, but the CCP has redoubled its commitment to using the law to carry out its objectives rather than allowing the law to constrain its discretion.Footnote 35 On 30 June 2020, following a months-long standoff with a broadly popular movement for the defense of Hong Kong's freedoms, the PRC National People's Congress passed a national security law penalizing secession, subversion, organization and perpetration of terrorist activities, and collusion with foreign actors, including acts committed by anyone, anywhere in the world. By operating above the Basic Law, Hong Kong's mini-constitution, the National Security Law has been widely regarded as ending the “one country, two systems” model that was expected to provide Hong Kong with a “high degree of autonomy” until 2047.Footnote 36 In response to British accusations that China had violated its commitments under the 1984 Joint Declaration, Chinese Ambassador Liu Xiaoming insisted that China has always upheld its international obligations and that “the copyright of ‘one country, two systems’ belongs to Chinese former leader Deng Xiaoping, not the Sino-British Joint Declaration.”Footnote 37 As developments in Hong Kong show, the CCP's willingness to refine and reinterpret its legal commitments indicates that it is unlikely that the CCP will rely heavily on rule-based restraints to legitimize its international leadership.

Fourth, the CCP has promoted a more ethno-nationalist vision of its rule: suppressing expressions of ethnic and religious identity with foreign ties, particularly Islam and Christianity, and appealing to foreign citizens of Chinese descent to love the motherland. This turn toward ethnic nativism rather than civic nationalism raises concerns about the CCP's willingness to tolerate individual differences and identitiesFootnote 38 and respect foreign governments’ sovereignty over their putative citizens. And it feeds doubts that a hegemonic China will want to preserve an interconnected world in which international actors and ideas have opportunities to “penetrate” the leading state and shape its choices in ways that render them more acceptable to other states.Footnote 39

These attributes suggest that the CCP's interests fundamentally conflict with the more demanding components of political liberalism, particularly the elevation of individual political rights above state sovereignty. That said, the leaders of post-Mao China have not sought to export a universal ideology or form of government, avoiding an irreconcilable conflict between China's rise and the defense of democracy.Footnote 40 As for economic liberalism, there are greater tensions between China's state-led mode of authoritarian capitalism and the first form of economic liberalism, premised on unfettered domestic markets, free trade between countries, and few constraints on international capital and foreign investment. But a form of re-“embedded” liberalism in which states have discretion to cushion the impacts of free trade could be more compatible with the CCP's desire for a stronger state role in the economy.Footnote 41 Finally, with regard to liberal institutionalism—governance via principled multilateralism—China has had a mixed record, working within some institutions to advance its interests (the World Bank, International Monetary Fund [IMF], UNSC, WTO, for example) while flouting others (including the rejection of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea [ITLOS] ruling on the South China Sea).Footnote 42 The CCP's preference for bilateral negotiations over multilateralism suggests that although China may become an increasingly ambitious stakeholder within existing institutions, its major new international initiatives, such as the Belt and Road Initiative, are unlikely to take the form of self-binding multilateral agreements that limit sovereign discretion.Footnote 43

Although some might see persistent differences between China's interests and the LIO as a failure of socialization, Johnston allows that these international processes do not necessarily subsume domestic interests.Footnote 44 Moreover, one must also consider the patterns of appropriate behavior into which China has been socialized. Namely, China has risen within a considerably less liberal version of international order in East Asia, where “American-led order is hierarchical but with much fainter liberal characteristics.”Footnote 45 Finally, as Lake, Martin, and Risse note in this issue, China is not the only state to reject many international intrusions on sovereignty; all states—liberal and illiberal—pick and choose which parts of the LIO to uphold.

Authoritarian Domestic Politics and International Order: Centrality and Heterogeneity

How does an illiberal state like China pick and choose the shape and extent of its engagement with the international order? What does China want from the array of structures, norms, and expectations that constitute the international system? Following Moravcsik, we consider state preferences—the outcomes that a state seeks in the international system—to be shaped predominantly by domestic interests, ideas, and the institutions that aggregate them.Footnote 46 State preferences cannot be deduced from the structure of the system or the distribution of power and capabilities but are determined first and foremost by domestic politics.Footnote 47

Authoritarian regimes are not monolithic, coherent, or static polities. As Wallace notes, the character of authoritarian politics at any given time is affected by “who is in power, how do they rule, and why they do so.”Footnote 48 Just as US investment in the LIO has been buffeted and shaped by shifting domestic coalitions and ideas as well as by systemic changes in the distribution of power in the system,Footnote 49 so are Chinese politics subject to domestic and international contestation.Footnote 50

The international context can also create incentives to alter domestic institutions and practices and foster the diffusion of norms and ideas.Footnote 51 International interactions have domestic consequences and can sometimes trigger domestic realignments.Footnote 52 Developments at the international level can create opportunities that empower certain domestic interests and ideas. International pressures can help accelerate domestic reforms but also generate domestic backlash, thereby strengthening hard-liners.Footnote 53 Ultimately, domestic structures and state–society relations condition how international ideas and practices are perceived and adopted.Footnote 54

Research on China's approach to international order has largely focused on the extent of China's compliance and integration with existing institutions and norms, although more recent work has examined China's impact on international institutions.Footnote 55 Crucially, these works have not systematically focused on what a rising authoritarian power such as China will seek to achieve, nor have they systematically examined the role of domestic politics in shaping these interests and strategies. Where and on what issues will China lead a “rules-based revolution,” in Goddard's terms?Footnote 56

We argue that two characteristics—centrality and heterogeneity—shape the domestic politics of a given international issue area in an authoritarian state. In the next section, we discuss each characteristic of the general framework and then discuss its implications for China.

Centrality

Centrality describes how closely an authoritarian government sees an issue affecting its survival prospects. Issues that are readily linked to a government's self-identified pillars of domestic support are more central than those that are not. Central issues are more likely to galvanize mass attention and conflict among regime elites, jeopardizing the regime's survival. Because authoritarian regimes can be challenged or ousted at any time, the leadership places high priority on preempting or extinguishing threats as they emerge, using a mix of repression and performance to suppress or placate domestic grievances. The costs of repression and the risk that it backfires increase with the centrality of an issue, giving authoritarian regimes more reason to rely on performance to address central issues. Performance can include policies that change outcomes, side payments to losers, and symbolic or rhetorical appeals that signal the regime's morality and affinity with domestic constituents.

Importantly, the centrality of any particular issue to the regime's pillars of support is contested. One of the leadership's main preoccupations is anticipating, pre-empting, or responding to links between seemingly minor issues and central pillars of regime support. Aggrieved individuals and interest groups often couch their demands in the same language that the regime uses to present its rule as legitimate.Footnote 57 By borrowing from and mirroring the regime's language, political entrepreneurs and activists magnify the resonance of their claims. In addition, a major challenge for the leadership is managing issues that touch upon multiple sources of regime support. Many policy choices involve trade-offs that may bolster support in one domain but harm it in another.

International issues vary in how closely they affect these pillars of regime support. A government is more likely to devote resources and attention to international issues that are domestically central than to those that are not. The greater the domestic centrality of an international issue, the more likely the government is to pursue unilateral policies that serve its domestic interests in shoring up these pillars.Footnote 58 In addition, international pressure is more likely to backfire when the changes demanded threaten to topple these central pillars of regime support. The greater the domestic centrality of an international issue, the harder it is for the government to concede internationally without suffering a potentially destabilizing domestic backlash.

In turn, the domestic centrality of an issue affects the government's bargaining position at the international level, in the spirit of a two-level game.Footnote 59 On central issues, a government that is more willing to “go it alone” in breach of existing norms and institutions is more likely to have leverage to demand international reforms on that issue or to build its own like-minded coalition of states to advance its views in an alternative set of institutions.Footnote 60 Ultimately, whether these investments entail greater cooperation or conflict depends on the prevailing norms and practices within a given issue area and the willingness of other stakeholders to make concessions to the government's domestic imperatives.

We next define the central pillars of CCP rule and then illustrate how the domestic positionality of different international issues have affected China's behavior. During the first twenty-five years of CCP rule, adherence to Mao's interpretation of communism and nationalism was the central pillar of regime support; potential challengers were deemed counter-revolutionaries or revisionists. With Mao's death and the move away from a planned economy in the 1970s, the CCP staked its legitimacy on three pillars: nationalism, economic growth, and public safety.

Nationalism

The CCP's ability to secure the nation's defense and territorial integrity has been critical to justifying its rule since the founding of the PRC, when Mao declared that “ours will no longer be a nation subject to insult and humiliation. We have stood up.”Footnote 61 As the last two Chinese regimes were ousted by nationalist movements, CCP leaders are especially concerned about defending the nation's sovereignty against foreign encroachment and returning to China the status and privileges of a great power.

Economic growth

The CCP has used growth and a litany of economic statistics, gross domestic product (GDP) in particular, to claim competence and justify its rule in the post-Mao era. Under Deng, the CCP moved away from communist ideology as a barometer of good performance, instead touting slogans such as “To get rich is glorious” and “black or white, as long as it catches mice it is a good cat.” In addition to creating opportunities for rents and patronage, economic growth has funded the levers of CCP rule, particularly the coercive apparatus and information control systems that undergird domestic support, enabling the regime to stamp out challenges, co-opt potential rivals, or prevent alternative centers of influence from emerging.

Public safety

The CCP's ability to keep its citizens safe from disease, disaster, crime, and terror has also been a central pillar of its rule. Public health issues commonly trigger domestic outcry and social mobilization, particularly when government malfeasance or inattention leads to the deaths of innocents.Footnote 62 The Chinese government's initial failure to disclose and act on the danger posed by the 2002–2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak triggered a wave of public concern and what the political scientist Yanzhong Huang has called “the most severe socio-political crisis for the Chinese leadership since the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown.”Footnote 63 The COVID-19 pandemic retraced these steps, with the government's initial delays in confirming evidence of human-to-human transmission, and the silencing of local doctors who tried to inform their colleagues about a new SARS-like virus, eliciting sharp critiques of Chinese-style authoritarianism and calls on Chinese social media for Xi Jinping to step down.Footnote 64 Only by silencing domestic critics and outperforming the many other countries that struggled to contain the virus did the Chinese government turn the tide of domestic discontent.Footnote 65

Many international issues are unlikely to impact these central domestic pillars. At the United Nations, most issues are peripheral to these domestic pillars of support. Even though China became a veto-wielding member of the UNSC in 1971, Beijing was relatively slow to take on an active role at the United Nations, reluctant to use its veto power, and often willing to compromise or cooperate with existing frameworks.Footnote 66 Some issues, such as sovereignty, have been more domestically sensitive. But even an issue such as sovereignty bundles a number of issues,Footnote 67 some of which are more central than others.

Our framework expects that the CCP will invest in and insist rigidly on facets of sovereignty that are more closely linked to central pillars of regime support, particularly the defense of the nation's territorial integrity and activity within its borders, and that are more likely to show flexibility and invest less in other facets, such as peacekeeping and international intervention.Footnote 68

Sovereignty over Taiwan is central to the CCP's nationalist claim that the island is rightfully part of China and that its de facto separation reflects an unfinished civil war. Taiwan is the major unresolved legacy of what party propagandists have termed China's “Century of Humiliation” at the hands of foreign powers, dating from the Opium Wars of the mid-1800s to the state's founding in 1949. As such, the leadership has regarded any moves that would make it appear “soft” on Taiwan independence as potential political liabilities. As Shirk notes, “No matter what public opinion actually is on this matter, the widespread belief that the CCP leaders would not survive politically if they did not fight to prevent Taiwan independence creates its own reality.”Footnote 69 Johnston concurs: “The party leadership appears to have calculated its more concrete ‘interests’ in retaining power: Anyone who ‘loses’ Taiwan not only will encourage a domestic domino effect among unassimilated minorities in Xinjiang and Tibet, but also will lose power.”Footnote 70

Given the domestic centrality of the Taiwan issue, the Chinese government has invested heavily in keeping Taiwan out of the international system. It has opposed official participation by Taiwan in international organizations, worked to peel away Taipei's diplomatic allies, and sought to limit the character of US diplomatic and military relations with Taiwan. Beijing reacted angrily to advanced US arms sales and staged live-fire missile exercises to protest the visit of former Taiwan President Lee Teng-hui to give a speech at his alma mater, Cornell University, in 1995. Beijing has made its economic assistance to third-party states conditional on adherence to “one China.” Beijing has also forced foreign corporations, particularly airlines and the Marriott hotel chain, to avoid language on their websites that could be construed as treating Taiwan as a country, allowing “Taipei” instead.

Internet governance also directly affects the CCP's survival prospects and sovereignty over activity within its borders.Footnote 71 Xi Jinping has publicly framed the issue of cyber security and cyber sovereignty as necessary to defend the nation from internal and external threats and to ensure a stable economy: “Without web security there's no national security, there's no economic and social stability, and it's difficult to ensure the interests of the broader masses.”Footnote 72 The CCP has also portrayed the Internet as a modern battleground against foreign efforts to weaken and divide the nation. As Xi put it, “Western anti-China forces have continuously tried in vain to use the internet to ‘pull down’ China.”Footnote 73 The Chinese leadership has made clear that controlling activity on the Internet in China is a matter of life or death, regarding it as “the main battleground of struggle over public opinion” and warning that “winning or losing public support is an issue that concerns the CPC's survival or extinction.”Footnote 74

Given the domestic centrality of the Internet, the Chinese government has been determined to embed “respect for cyber sovereignty” into international discussions of Internet governance. Xi Jinping laid out China's position at the 2015 World Internet Conference in Wuzhen, where he emphasized “respect for cyber sovereignty” as the first principle needed to advance “the transformation of the global Internet governance system.”Footnote 75 China's 2016 national cyber strategy also listed “respecting and protecting sovereignty in cyberspace” as the first principle. Support for state sovereignty in cyberspace is not uniquely Chinese; the independent Tallinn Manuals also agree that “the principle of sovereignty applies to cyberspace.”Footnote 76 But at the fourth meeting of the UN Group of Governmental Experts Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security, China worked with Russia to “expand the statement of the sovereignty norm.”Footnote 77

On less central facets of sovereignty, such as humanitarian intervention and peacekeeping, the CCP has been more willing to compromise. On peacekeeping, Wuthnow writes that China's stance evolved from “principled opposition in the 1970s, to begrudging acceptance in the 1980s, to limited participation in the 1990s, to active contributions in the early twenty-first century.”Footnote 78 On international intervention, China dropped its initial opposition to the R2P principle, ultimately endorsing its application in multiple countries, including Darfur, Libya, Yemen, and Mali.Footnote 79 In Syria, Beijing supported a number of UNSC resolutions and abstained on several others, initially reserving its veto for actions it associated with the threat of forcible regime change, and later seeking to preserve host state consent.Footnote 80 As Börzel and Zürn, note, this “pushback is different from full rejection or even dissidence.”Footnote 81 Along with Russia, China has sought to defend the authority of the UNSC as an institution, while countering the most intrusive applications of the R2P principle, particularly after the 2011 intervention in Libya led to the extrajudicial killing of its long-standing dictator, Muammar al-Qaddafi.

That there are international issues that touch on central pillars of regime support does not necessarily mean that the government is unable to make concessions, particularly as part of an international agreement that helps the government's interest regarding another central issue. For example, Fravel shows that the CCP has been willing to make territorial compromises with neighboring states in order to shore up domestic security and control over minority populations.Footnote 82 Similarly, many international issues affect multiple pillars of regime support, meaning that shifting conditions and emerging crises can galvanize unexpected changes in the government's strategy.

China's changing stance in international discussions on carbon emissions is a prime example of an international issue that touches on two central pillars: economic growth and public health. Initially, the CCP viewed international efforts to limit carbon emissions as threatening to domestic economic growth. Chinese negotiators echoed the developing world's chief refrain: that rich countries bear primary responsibility because of their historical emissions.Footnote 83 China's resistance to bearing the costs associated with carbon limits persisted through the Copenhagen meetings in December 2009, where its behavior “appeared calculated to frustrate progress.”Footnote 84 During this period, the domestic centrality of growth imperatives drove China's international opposition to binding emissions targets.

As high levels of air pollution threatened public health, the Chinese government strenuously tried to repress domestic awareness of the issue. In 2007, the World Bank estimated the number of Chinese killed every year by pollution to be 750,000, but this figure was scrubbed from initial public pronouncement after pressure from Chinese government officials.Footnote 85 It was not until the scale of the catastrophe was revealed and galvanized mass and elite outrage that the Chinese government shifted strategies, emphasizing public welfare over growth and investing in international efforts to limit carbon emissions.

In April 2008, the US Embassy began collecting samples of small particulate matter and publishing the results hourly on Twitter, ignoring the Chinese government's objections that this was “interfering in the internal affairs” of the PRC. In October 2010, the account tweeted that Beijing's air was “crazy bad,” twenty times the World Health Organization's guidelines. Programmers had jokingly coded that label for scores beyond index, not expecting it to be triggered.Footnote 86 In the fall of 2011, the US Embassy's monitoring equipment again registered scores so polluted that they were “beyond index,” even though the Beijing city government had reported that the air was only “slightly polluted.”Footnote 87 Real estate developer Pan Shiyi sent multiple messages to more than 16,000,000 followers on Weibo calling for the Chinese government to monitor PM2.5 rather than just PM10, including a poll in which more than 90 percent of 40,000 respondents agreed. Days later, Premier Wen Jiabao acceded, saying that the government needed to improve its environmental monitoring and bring its results closer to people's perceptions.Footnote 88 The government added PM2.5 to a more restrictive set of standards in February 2012, with monitoring stations broadcasting hourly reports installed in dozens of cities by the end of that year.Footnote 89

The domestic centrality of air pollution as a public health crisis spurred the Chinese government to shift gears. As Xi Jinping explicitly noted: “our environmental problems have reached such severe levels that the strictest measures are required … If not handled well they most often easily incite mass incidents.”Footnote 90 A documentary on the health consequences of China's toxic air by former CCTV journalist Chai Jing garnered more than one hundred million views in forty-eight hours before being abruptly censored by Chinese authorities.Footnote 91

Because sources of smog—principally coal—also emit substantial amounts of carbon dioxide, the Chinese government's efforts to combat air pollution simultaneously sought to reduce carbon emissions.Footnote 92 As Wu put it, China “shifted from a climate free-rider to a climate protector.”Footnote 93 In November 2014, Presidents Barack Obama and Xi Jinping reached a historic agreement setting “new targets for carbon emissions reductions by the United States and a first-ever commitment by China to stop its emissions from growing by 2030.”Footnote 94 Leading up to the Paris Conference of Parties (COP)-21 meetings, bilateral cooperation between the two largest emitters continued with the United States–China Joint Presidential Statement on Climate Change. China's support was indispensable to making the Paris meetings successful, where countries promised to make nationally determined contributions (NDCs) without a punishment process.

China's climate strategy shifted again as concerns about economic growth came to the fore in 2018, following the United States–China trade war and efforts to constrain credit expansion. These economic pressures pushed the Chinese government to loosen regulations on industrial pollution, leading firms in Beijing's environs to increase production, and Beijing's air pollution returned with a vengeance in the winter of 2018.Footnote 95

Seen through our framework, China's international climate leadership is less the result of a principled stance than the byproduct of shifting domestic imperatives between growth and public health.Footnote 96 Curbing emissions became a critical task for the government once Chinese citizens identified smog as air pollution rather than “fog.” The quantification of air pollution provided a focal point for mass and elite criticism. Growing social pressure on the government to protect public health, even at the expense of slower economic growth, helps explain China's about-face on climate change within a span of 10 years. Yet as the Chinese economy slowed in 2018 and then contracted for the first time in decades with the onset of COVID-19, the government refocused its efforts and prioritized domestic growth and employment over clean development.

Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity describes the degree of domestic division and contestation over government policy regarding a given international issue. Divergent interests and ideas about how to achieve those preferences can arise at both the mass and at the elite level, often rooted in geographic, economic, institutional, and ideological differences.Footnote 97 Even in authoritarian regimes, one can discern heterogeneity in surveys of public opinion, private and public commentary by policy elites and experts, and the statements and actions of state-owned and private industries, local governments, and central ministries. Leaked documents and archival material indicate that divisions within the regime's inner circle or politburo are often critical to authoritarian decisions, but may not become publicly available until much later.

Although most subnational actors in authoritarian systems lack formal veto power, their preferences and the implicit or explicit threat of noncompliance or disruptive protest may still affect the leadership's decision making, constrain implementation, and require side payments to minimize opposition. Even in authoritarian systems such as China's, power is fragmented and contested.Footnote 98 Central and local leaders face distinct incentives and possess different levels of information, making principal-agent problems pervasive.Footnote 99 Central decisions must be interpreted and implemented by multiple agents of the state at various levels of government, who in turn face the challenge of curbing the behavior of powerful industries and economic interests. In addition, when state leaders set out a general direction but leave the specifics to be hashed out, concentrated domestic interests can dominate both the design and implementation stages of the policy process. For example, Xi Jinping's signature Belt and Road Initiative has provided an encompassing but vague slogan that “makes it easy for domestic interest groups to use a national policy as cover to pursue their own agenda.”Footnote 100

The heterogeneity of domestic interests varies widely across international issue areas. An issue characterized by low domestic heterogeneity means that there is relatively little contestation over what the government should do at the international level. Low heterogeneity can arise when there is a mass–elite consensus in favor of a particular outcome, with minimal or weak dissent. Low heterogeneity also characterizes issues about which a small set of actors has an outsized stake in the outcome, and the majority is indifferent. In such cases, concentrated domestic interests can dominate or capture the policy process without opposition. In turn, the preferences of those concentrated interests can directly shape the government's international stance.

On issues characterized by high heterogeneity, both masses and elites may be divided over what international outcome the government should seek to achieve, with multiple stakeholders arguing at cross purposes. The higher the heterogeneity of domestic preferences and mobilized interests, the greater the likelihood that policies benefit some at the expense of others, whose opposition may need to be defused with side payments. On issues with high domestic heterogeneity, international commitments are likely to face compliance and enforcement challenges. As such, the anticipation of partial implementation may be necessary in order for national-level negotiators to reach international agreements.Footnote 101

Low- and high-heterogeneity issues carry different domestic risks and rewards for the regime. Issues that unite a mass–elite consensus make it difficult for the government to show flexibility in the face of foreign pressure, as it risks a wider domestic backlash and defection or punishment of other elites. But international success on a low-heterogeneity issue can also give the government a larger boost in domestic support, as masses and elites are united in supporting that outcome.

In contrast, issues characterized by significant domestic divisions are challenging because some constituency will feel aggrieved that the government did not prioritize its interests. Side payments may defuse some of this opposition in the short run, but also give those actors resources and reasons to continue their efforts to lobby, petition, or protest in the future. If the government instead uses targeted repression against disgruntled losers, it can clear short-term obstacles but increase long-term resentment. In short, the downside risk to the regime is typically lower when an issue is characterized by high heterogeneity because domestic divisions reduce the likelihood of a united challenge to its rule. But the upside rewards are also lower for high heterogeneity issues because the government must use costly side payments or targeted repression.

Turning now to China's international interactions, a number of issues are characterized by low domestic heterogeneity. The reunification of Taiwan with mainland China is a goal that unites both masses and elites in China. Involvement in UN peacekeeping operations and the safety of Chinese citizens overseas are also issues on which there is relatively little domestic disagreement. On these issues, the Chinese government has set policy without much mass or elite dissent. As for low-heterogeneity issues about which a concentrated domestic interest dominates the policy process, a prime example is China's refusal to join the Ottawa Treaty banning landmines. As Johnston notes, it was the Chinese military's interest in continuing to use land mines that drove the government's refusal to sign the treaty despite international pressure.Footnote 102

On many other international issues, the Chinese government faces substantial domestic divisions. For example, export-oriented industries that benefited from a stable, undervalued renminbi (RMB) have fought against revaluation, arguing that it would undermine social stability by leaving millions of Chinese workers without jobs. To pursue RMB appreciation, the Chinese leadership had to placate these interests with subsidies and other preferential policies.Footnote 103 On cyber sovereignty, the strength of domestic interests in having access to an open and unfiltered Internet has meant partial and porous implementation of Chinese government efforts to control cyber activity within its borders.Footnote 104 The government has tolerated widespread use of virtual private networks (VPNs) to jump the Great Firewall. Periodic crackdowns have made it harder for users with Chinese-made VPNs to access the outside Internet, while still allowing elites with access to foreign-made and purchased VPNs to browse freely.Footnote 105 And some intensive forms of monitoring, such as real-name IP registration and mandatory “Green Dam” filtering software on new computers, were stymied by opposition from the public and private businesses.Footnote 106

High domestic heterogeneity has also characterized China's engagement with international efforts to address climate change, with particular opposition from polluting industries and the local governments that benefit from those revenues. These divisions have caused difficulties with the implementation and enforcement of China's international environmental commitments. Local officials have often resisted central directives to shut down polluting firms, as economic development remains of primary significance in cadre promotion evaluations.Footnote 107 Chinese officials and industries are also adept at gaming the system and providing as-if compliance with environmental regulations and incentives. Two examples are fudging pollution counterfactuals to gain resources through the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) as well as cheating on chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) agreements. One study found that more than 85 percent of CDM projects had a low likelihood of “emission reductions being real, measurable, and additional.”Footnote 108 China is also a party to the Montreal Protocol banning the production of CFC-11, which depletes atmospheric ozone and has “a global warming potential 4,750 times that of carbon dioxide.” However, international investigators in 2018 traced an increase in CFC-11 to numerous chemical plants in China, which had resorted to producing the banned substance because its replacement was more expensive and less effective.Footnote 109

At the same time, the interests of China's renewable energy industries have shaped its efforts to combat climate change in more positive ways. China's investments in renewables served to help its firms establish a leading position in a growing sector, but these policies have also generated positive externalities to help global efforts to combat climate change. In 2017, China accounted for more than half of global solar installations and 37 percent of wind turbines, and China's dominance is even stronger in manufacturing.Footnote 110 Because of the falling cost of Chinese-subsidized renewables, other countries have become “more confident that a gradual shift towards a low-carbon economy will not necessarily harm their long-term growth strategies.”Footnote 111

Nevertheless, the type of renewable energy technology that China is exporting has more to do with its industries’ interests than with what is needed abroad. Take, for example, China's global promotion of ultra-high-voltage electricity grids developed by one of its gargantuan state-owned enterprises, State Grid. Although lauded from a climate-change angle as a potential solution for reducing intermittency problems of renewables by linking more distant power sources with less wasted current, the actual grids being constructed are mostly in countries where fossil fuels dominate.Footnote 112

As these examples illustrate, heterogeneity does not have a straightforward relationship with international cooperation or confrontation. Rather, it helps explain the nature of the domestic constraints and incentives that a government brings to the international table. Greater heterogeneity is likely to produce tougher and more drawn-out international negotiations as well as increasing the likelihood of implementation failure, requiring more monitoring and possibly enforcement in international agreements. Partial compliance may in turn make it more difficult for other governments to assess Beijing's intentions to determine whether Beijing reneged after negotiating in bad faith or simply lacked the capacity to bring wayward domestic actors in line.

Centrality and Heterogeneity: Malleability and Movement

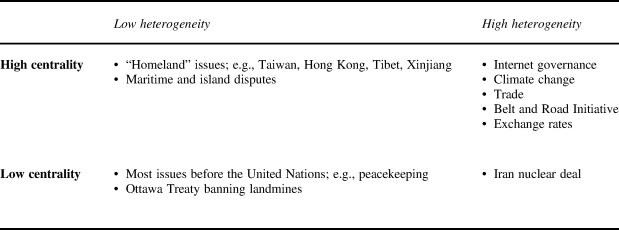

As Table 1 illustrates, centrality and heterogeneity do not map neatly onto one another. Some highly central issues are also highly heterogeneous, such as cyber sovereignty and climate change. Some highly central issues are characterized by relatively low heterogeneity, such as Taiwan. Some issues are characterized by low centrality and low heterogeneity, such as most issues before the United Nations and China's involvement in international peacekeeping. Finally, some low-centrality issues are characterized by a high degree of heterogeneity, like nonproliferation agreements to halt the spread of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and related missile technology. These are not issues that directly affect the core pillars of regime legitimacy; therefore, China has not invested much international effort in addressing them,Footnote 113 but national-level cooperation has been undermined by subnational Chinese actors with a strong countervailing interest. For example, Johnston notes that China “played an important role in the 2015 Iran nuclear deal (helping redesign a key reactor to reduce Iran's future plutonium output),” but also failed to halt the export of ballistic missile technology to Iran.Footnote 114

TABLE 1: Domestic centrality and heterogeneity in China's international approach

Yet no static representation (as in Table 1) depicts the malleability and movement of issues as domestic actors try to manipulate the apparent centrality and heterogeneity of a given issue. For example, subnational actors may link their demands to a central pillar in order to increase the likelihood of side payments or loopholes that protect them from international commitments. In a bidding war for government attention, subnational actors that amplify the centrality of their interests are more likely to succeed than those whose interests remain peripheral and parochial.

For example, during protracted negotiations over China's admission to the WTO, an array of industries, ministries, and provincial governments lobbied heavily for continued protection, some more successfully than others. The telecommunications industry and its affiliated ministry, the Ministry of Information Industries, succeeded by linking demands for protection to the national interest rather than a desire to avoid market competition. As Pearson notes, “Industry officials claimed foreign Internet providers would use access to China's Internet markets to steal economic information, disseminate propaganda via email, and use the Internet to support dissidents or undermine the party. Such arguments tapped into deep worries about loss of Chinese sovereignty to foreign powers. Widespread fear of social unrest made such arguments especially potent.”Footnote 115

In addition, the government may also try to increase the centrality of an international issue in order to reduce domestic dissent and demonstrate resolve in international negotiations. For example, by framing resistance in Hong Kong and the United States–China trade war as part of a national struggle reminiscent of the Opium War, Korean War, and other protracted disputes in which China eventually prevailed, the Chinese government has built public support for the costs of conflict, raised the domestic cost of international concessions, and signaled its intent to stand firm against foreign pressure. As Shi and Zhu note, the Chinese government has used its propaganda powers to frame the United States–China trade war as an existential struggle for the Chinese nation's development. When framed as a geopolitical struggle with the United States, Chinese survey respondents were much more supportive of the government's handling of the trade war than when the trade war's economic costs were mentioned.Footnote 116

Conclusion

Can the LIO survive the challenge of China's growing influence and desire to reshape global governance? China's authoritarian character is at odds with key aspects of the system, particularly the emphasis on political liberalism and rules-based multilateralism. At the same time, the CCP has not spent significant energy defeating these liberal principles internationally except where they threaten its domestic survival and sovereignty. China has profited from its participation in the LIO and remains a staunch defender of the Westphalian order on which it was built. Indeed, at times the Chinese government has appeared more invested in preserving existing arrangements than the United States has, hence the irony of Xi Jinping defending free trade at Davos and COVID-19 cooperation at the World Health Assembly.Footnote 117

The CCP has behaved strategically, investing in reshaping or rejecting international arrangements in issue areas that are central to its domestic rule and being more willing to free ride or defer to international practices on issues that are more peripheral. China's domestic “social purpose” does not require the wholesale destruction of the existing international order, although it favors a more conservative version that emphasizes Westphalian norms of sovereignty and noninterference. Within the United Nations, for, example China has sought to alter international obligations on human rights to emphasize the primacy of state sovereignty, oversight of civil society, and economic development.Footnote 118 At the same time, under international pressure, the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank adopted rhetoric about the environmental and social consequences of its policies similar to those led by developed countries. And the IMF applauded China's announcement of a debt-sustainability framework in response to international criticism of the Belt and Road Initiative.

To understand the variation in China's approach to international order, we have proposed a framework grounded in the domestic politics of authoritarian rule. Two factors, centrality and heterogeneity, shape the PRC's approach to various issues in the area of international order. The more closely an international issue touches upon one or more of the central pillars of the regime's rule, the more the regime will invest internationally in that issue and resist international pressure. The greater the heterogeneity of domestic interests regarding an international issue, the more the regime will face competing demands from different subnational actors, requiring offsetting policies and partial implementation to appease countervailing interests. Although these characteristics are distinct, they can be strategically linked. For example, the CCP's nationalistic framing of the trade war aimed to reduce domestic heterogeneity by increasing its centrality.

Foregrounding the role of domestic politics is essential for understanding why and on what issues a powerful state chooses to invest in international leadership, and when it might choose to walk away from or shirk previous commitments. Our framework suggests that China's international leadership is more likely to be a byproduct of the CCP's domestic self-interest than a principled effort to provide public goods, although that was often the case for the United States. Acknowledging the primacy of domestic drivers also cautions against optimism that naming and shaming will lead to greater Chinese convergence with the LIO or hopes for a ratcheting-up of voluntary commitments and compliance.Footnote 119

Domestic politics affect a state's preferences and negotiating strategies in ways that system-level factors, such as the balance of outside options or position within international networks of influence, cannot wholly predict. The strategic setting matters, but these system-level attributes are often endogenous to domestic calculations.Footnote 120 Although developed here in reference to authoritarian states, centrality and heterogeneity can provide a generalized framework to study the domestic pressures that governments across the spectrum of regime types face in relation to the LIO.

The future of the international order will depend on domestic political shifts not only in China but also in the United States and other leading members. China is not alone in shifting toward more ethno-nationalist policies; such trends are also apparent in democracies from India to Israel.Footnote 121 And many countries, including the United States, share China's ambivalence about some of the more intrusive elements of the liberal order, such as the International Criminal Court and International Court of Justice.Footnote 122

On the other hand, the United States and other “like-minded” democracies could choose to build an enhanced but less universal set of institutions, with demanding standards of membership that would likely exclude China and other illiberal states.Footnote 123 China might be willing to change its practices in order to participate in some of these new arrangements, but only if the domestic price was not too high.

Our framework suggests that China would be more likely to show flexibility on issues that are less central. But even on issues that are highly central, such as trade, investment, intellectual property, technology, and the environment, their high heterogeneity means that the CCP may still be willing and able to make progress toward a set of international commitments. These negotiations are likely to be difficult and would require domestic side payments and risk partial enforcement to accommodate competing domestic interests. In contrast, on issues that are more central and less heterogeneous, the CCP is more likely to go it alone, forge an alternative coalition of states,Footnote 124 or work to shift norms in a less liberal direction.

Illiberal pressures from leading authoritarian states, along with populist challenges from within leading democratic states, might combine to produce a more minimalist version of the LIO. Reweighting international norms to privilege national sovereignty would require tolerating more political and ideological diversity than the “postnational liberalism” that blossomed after the Cold War.Footnote 125 A less domestically intrusive but still open and rules-based international order would help satisfy the Chinese government's desire for a world safe for autocracy alongside democracy.Footnote 126 Without such modifications, China's growing influence will likely lead to more conflict outside the system than competition over the rules inside it.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors, two anonymous reviewers, David Lake, Lisa Martin, Thomas Risse, and participants in the Madison and Berlin workshops for feedback on earlier drafts, and Eun A Jo for research assistance.