Leaders sometimes express sentiments with clear and explicit racial bias. Richard Nixon, for example, was well known for invoking racial stereotypes while in the White House, including use of antisemitic and other tropes.Footnote 1 In recently declassified White House tapes, for instance, Nixon combines racial and gender stereotypes in describing women of India as “the most unattractive women in the world,” adding, “the most sexless, nothing, these people. I mean, people say, what about the Black Africans? Well, you can see something, the vitality there.”Footnote 2

As jarring as such language is, racial bias may also affect the foreign policy views and behavior of states in more subtle ways. Scholars of race outside of international relations (IR) have long argued that, even if more explicitly racist commentary is suppressed, racialized stereotypes often subtly affect perceptions and political conduct.Footnote 3 Examples of implicit racial appeals, also from Nixon's presidency, can be found in a pair of written intelligence items from 1969. One passage about Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser describes a newspaper's criticism of the United States but claims such rhetoric “is probably another of Nasir's celebrated tantrums.”Footnote 4 A week later, another intelligence item notes a history of assassinations and predicts that the Jordanian king's “current conflicts with the Palestinian terrorists have increased the possibility that some rabid Arab may put a bullet into Husayn.”Footnote 5 In both, language interpreting events and people in the Middle East implies violence, irrationality, and a lack of control. While the second example certainly uses stronger language and mentions an ethnic or racial category (Arab), the racialized nature of “rabid” is not readily apparent without taking into account the historical dehumanization of non-Western Others as animal-like.Footnote 6 The use of a term like rabid to invoke a stereotype, then, can be considered an implicit racial appeal.Footnote 7

These two examples come from the President's Daily Brief (PDB), a daily and highly classified intelligence compilation prepared for top US leaders since the early 1960s. The PDBs are among the closest-held national security documents. In 2016, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) completed a dedicated declassification review of PDBs created for presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, and Ford. Our data are built from the resulting 4,978 separate PDBs covering seventeen years (1961 to 1977). We find that assessments of events and actors in parts of the world that were considered “racialized Others” are more likely to reference animal-based analogies or otherwise use language that implies infantilism, belligerence, and irrationality. While the language in such tropes can be used in nonracialized ways, our analysis accounts for how terms and metaphors can be “read onto” different actors as part of White supremacist and patriarchal systems of thought.Footnote 8 Building on previous work, we argue such racialized tropes reflect how attributes of human individuals or groups become associated with broader categories of social organization.Footnote 9 We find that such tropes appear more commonly in items about developments in the Global South, for newly independent states emerging from decolonization, and for specific regional groupings such as Asia. We also assess changes over time and find that the peak use of the four racial tropes in our data varies and, in general, such tropes remain prevalent into the late 1970s.

Our findings are especially striking because they feature highly vetted intelligence summaries specifically designed for four very different American presidents. Off-the-cuff remarks, like Nixon's, do not show whether or how racial biases are baked into the administrative mechanics of the state. But if events and leaders in some places in the world are systematically portrayed as irrational or belligerent in carefully edited intelligence documents, then this provides unique evidence of the deep internalization of such belief systems. Moreover, while some scholars have focused on regime type as a source of perceptual bias (dictators and other autocrats are seen as unpredictable and unreasonable), our findings suggest that racial difference influences such trope usage above and beyond regime type. In general, the patterns we find hold across foreign policy topic and issue areas, suggesting a pervasive tendency to lean on racialized tropes in interpreting a range of foreign developments in international affairs. Overall, the patterns in racialized language we identify are robust to the inclusion of numerous variables that could plausibly account for differences in language across regime type, geopolitical relationship with the United States, presence of conflict, and topic/issue discussed.

Our analysis advances scholarship in three ways. First, we contribute to the study of race and racism in IR by drawing particular attention to implicit expressions of racial bias in bureaucratized settings. We show the prevalence of language that invokes racial tropes of irrationality, belligerence, and analogies to children and animals within a highly bureaucratized foreign policymaking process. Our approach builds on a robust literature in the study of American domestic politics about the racialized nature of public policy and the role of racial tropes in everything from welfare to gun control.Footnote 10 Yet we differ in highlighting private deliberations within the foreign policy bureaucracy and implicit racial constructs that are applied to foreign countries, populations, and leaders.Footnote 11 Our article therefore complements a growing literature in IR and long-standing work in American politics on explicit racism in more public rhetoric and government policy.

Second, we demonstrate the promise in combining text-based tools at scale and a corpus of unique archival material to identify subtle but important biases in originally classified deliberations. Our article is the first (to our knowledge) to use supervised machine learning techniques on declassified bureaucratic outputs to analyze racial stereotypes or any stereotype-driven interpretation regarding foreign affairs. Assessing language patterns in tens of thousands of individual pieces of national security writing—using tools that use but also go beyond dictionary-based measurement—allows us to detect forms of implicit racial bias that would be simply impractical to measure with exclusively manual review. Our data and approach can be straightforwardly adapted to documents from other bureaucracies and also to assess gender, sexuality, class, and other forms of bias in foreign policy analysis.

Finally, our findings have significant practical implications. We build on research that has firmly established how racially biased perceptions affect foreign policy behavior. As Búzás summarizes, “by coloring the perceptions of decision makers, racial identities can exert a direct influence on state behavior.”Footnote 12 Racial stereotypes and bias have been linked to a range of state behaviors, including territorial expansion and empire building,Footnote 13 alliances and other inter-state agreements,Footnote 14 decisions to revise the balance of power,Footnote 15 the severity of wartime atrocities,Footnote 16 the validity of the democratic peace,Footnote 17 and threat perceptions.Footnote 18 Racial stereotypes have also been linked to international tradeFootnote 19 and economic aid.Footnote 20 Most recently, implicit racial bias played an important role in responses to COVID-19.Footnote 21 The significance of our findings on analogies is also underscored by the separate literature on the impact of analogies on foreign policy decision makingFootnote 22 and the fact that the intelligence community considers the PDB “our most important product.”Footnote 23 This article therefore helps establish how implicit racial tropes structured the way the American foreign policy bureaucracy understood events and informed leaders at the highest levels of government during the Cold War.

Race, Perceptions, and the Foreign Policy Bureaucracy

Despite inattention to issues related to race and racism in the mainstream study of IR,Footnote 24 the foundations of the field feature important work on race. This work begins with Black scholars addressing issues of race and politics in the twentieth century. Academics like Merze Tate, Alain Locke, Ralph Bunche, and W.E.B. Du Bois wrote extensively on the role of race in international affairs and global conflicts.Footnote 25 Drawing on these early innovators, more recent work critically analyzes paradigmatic concepts and theories in the discipline. These authors find that many foundational theories suffer from Eurocentric biases.Footnote 26 Such biases remain despite advances in critical theories of race and racism.Footnote 27 While race is not a biological reality, race as a global norm or idea has both ontological and material consequences across the global and international context.Footnote 28 Beyond these critiques and corrections to foundational theories, more contemporary work explores the role of race in explaining specific empirical phenomena in subfields such as international law,Footnote 29 political economy,Footnote 30 security,Footnote 31 and the liberal international order more broadly.Footnote 32

A prominent way that scholars analyze racially biased perceptions is through discourse. We take a similar approach by focusing on racial tropes in the internal appraisal of foreign affairs by a state. We define racial tropes as “single words or short phrases that only hint at familiar stories” with some form of racial link or connotation.Footnote 33 Racial tropes often invoke “hegemonic stories where there is little ambiguity and everyone agrees on meaning.”Footnote 34 The word trope—which encompasses stereotypes and analogies—is useful for two reasons. First, it highlights how stereotypes, analogies, and narratives can be activated with short words or phrases. We intentionally include linguistic markers that feature analogies as well as ones that invoke stereotypes without analogies. Thus we can identify racial bias in a passage about a foreign leader even if the text features no analogies or metaphors. Second, tropes are a useful lens for identifying implicit rather than explicit moments of racialized thinking or writing.

The distinctions between explicit and implicit racial tropes are subtle. For Mendelberg, explicit racial communication requires the use of racial nouns or adjectives to express sentiments against racialized Others, while implicit racial communication conveys similar messages but “replace[s] racial nouns and adjectives with more oblique references to race.”Footnote 35 Such language invokes ostensibly race-free positions while alluding to racial stereotypes or perceived threats from racialized Others. While the words themselves may not always be associated with racial bias, it is the application of these words with reference to certain identity groups that makes implicit language racialized.Footnote 36 Attending to more implicit ways in which racism operates is important since “the activation of implicit evaluations and associations can influence, often without the individual's awareness or intention, nonverbal behavior in systematic ways.”Footnote 37 We think this is especially relevant when assessing race in writing composed by the foreign policy bureaucracy, where a professional or technical ethos combined with a bureaucratic vetting process may make explicitly racist language rare. Within these contexts, scholars of race have recognized that racialized thinking and racism operate through “organizational procedures” as well as social behaviors.Footnote 38

Racial tropes are often specific to both place and time.Footnote 39 While our focus is foreign policy in the 1960s and 1970s, scholars have long analyzed how US domestic policy can become explicitly and implicitly racialized, as in debates on domestic welfare policy, health care, and gun control.Footnote 40 Moreover, the tropes we assess during the Cold War period have deep roots. Doty, for example, shows that similar racial stereotypes were routinely invoked regarding the Philippines during American colonial occupation at the turn of the twentieth century.Footnote 41 In what follows, we strike a balance between analyzing racialized lenses that likely operated at a high level of generality across a broad variety of racial Others (the entire Global South) as well as more particular groupings (disaggregating by region). We also assess variation over time of each of the racial tropes we develop.

Four Racial Tropes

Building on scholarship in political science, sociology, and psychology, we identify a set of hypotheses about racialized tropes that may appear in foreign policy bureaucracies. We focus on four distinct themes, informed by earlier work on common stereotypes regarding racialized others.Footnote 42 We argue that these racial tropes should be more likely to be invoked in interpretations of foreign leaders and events in racialized places. Thus, the final subsection discusses our expectation that tropes will be used more frequently when analyzing developments in the Global South compared to the Global North, for newly independent countries, and for particular regions traditionally treated as racially different by US elites.

Infantilization. A common trope applied to subordinated social groups and classes is what we refer to as infantilization. This is the attribution of concepts, behavioral tendencies, and other features associated with children to a person or group. While racialized Others are not the only marginalized groups that certain actors may infantilize,Footnote 43 scholarship spanning a diverse set of disciplines has established that superordinate groups often stereotype racialized Others as childlike, usually to justify subjugation or outside control.Footnote 44 Research on racial discourses in foreign policy has further confirmed this discursive pattern of comparing subordinated groups to children.Footnote 45 It can include implicit or explicit assumptions about mental abilities (childlike wonder or naïveté) as well as more behavioral tendencies (throwing a “tantrum”).Footnote 46 For example, a 1967 PDB item observed that the president-elect of El Salvador, Fidel Sánchez Hernández, would attend a meeting of American heads of state in Punta del Este, Uruguay, allowing the current president, Julio Adalberto Rivera, to “baby-sit at home with his vice president, whom he is afraid to leave in charge.”Footnote 47 To be clear, some qualities or behaviors potentially associated with children, such as emotional outbursts, may appear in other categories. We therefore define infantilization narrowly as instances when such traits are explicitly linked to children or child-related concepts.

Animal Analogies. A second trope applied to racial or other subordinated groups is dehumanization (the application of concepts and behavioral tendencies associated with nonhumans to a person or group of people), specifically in the form of invoking animal and animal-related analogies to behavior.Footnote 48 Animal comparisons are a consistent theme in work on the dehumanization of groups based on racial or ethnic identity.Footnote 49 Such animal-related connotations or comparisons may be literal (as in an attack during war being described as “like shooting fish in a barrel”) or implied. One example from the PDB corpus on South Vietnamese leadership notes, “A number of leading Khanh subordinates continue to growl about the way the general is running things.”Footnote 50 Use of the word growl in this case—an action associated with aggressive and uncontrollable animals—is a less obvious but similarly important linguistic choice. An item from 1961 is especially blunt in describing Iraq's Abdul Karim Qasim as “half cuckoo and half fox.”Footnote 51

Belligerence. Another important trope characterizes a racialized Other as belligerent—that is, bellicose, aggressive, or unusually prone to violence. This trope has been noted in work in IR on international policing and counterinsurgencyFootnote 52 and in the view of racialized Others in the American domestic political context.Footnote 53 Scholarship on the history of British and French empires specifically notes stereotypes of the colonial Other as rebellious and belligerent.Footnote 54

In the American domestic context, many scholars have noted the ways in which stereotypes of Black Americans as belligerent and/or more violent have directly impacted individual policy preferences, especially among White respondents.Footnote 55 Examples of aggressiveness or belligerence in the PDB corpus we analyze include an entry on Cuba–Africa relations where a speech by Fidel Castro criticizing South African presence in Angola “was couched in belligerent language.”Footnote 56 In another entry on “political deterioration in Singapore,” the entry describes the Malayan prime minister as being “in a hostile mood.”Footnote 57

The link to belligerence and racialized Others is complex. In fact, some racial stereotypes feature the racialized Other as weak, lazy, or docile. For example, American views of the Japanese before, during, and after World War II attributed martial belligerence and docility in different eras.Footnote 58 Other work on colonial history notes that colonial powers had different perceptions of the degree of “martialness” for different races and ethnicities.Footnote 59 In one recent study that also focuses on patterns in texts, Charlesworth, Caliskan, and Banaji find that the word belligerence is more associated with the White identity group than the Black identity group in some eras while rebellious and unruly have the reverse association.Footnote 60 Despite these findings, on balance, we expect attributions of belligerence to be positively associated with measures of racialized Otherness in general, given that past research—especially works that analyze colonialism and resistance to it—emphasizes this form of racial trope. We then move beyond this basic expectation and provide some predictions for regional variation in the attribution of belligerence.

Irrationality. As noted, critical scholarship on the West/non-West binary points to the attribution of greater rationality to the West.Footnote 61 Again, although attributions of irrationality are not applied solely to racialized groups, the association often serves to support systems of racialized oppression.Footnote 62 In one of the earlier examples of scholarship on this subject, Edward W. Said delineated the association between the colonized or racialized Other and irrationality.Footnote 63 Specifically, European discourse depicts Europe as a “model of masculinity and modern rationality and order”Footnote 64 while excluding others “from the realms of thought and rationality,”Footnote 65 concealing the emotional aspects of thought and reason.

We therefore assess the frequency of attributions of irrationality itself, in addition to the irrationality implied by child- and animal-like comparisons. PDB entries that showcase this stereotype may directly attribute irrationality—or related concepts such as loss of temper or volatility—in the interpretation of events and specific actors. If rationality assumes actors take into account all possible actions, outcomes, and probabilities of success associated with these actions, PDB items may implicitly or explicitly portray irrational actors as deviating from such a process. One example from the PDB invokes the trope of irrationality by expressing surprise at what it views as out-of-character rational behavior on the part of Laotian General Phoumi: “Phoumi discussed the defense and interior posts problem in a rational manner for the first time.”Footnote 66 Another entry attributes paranoia to Cambodia: “The most disturbing aspect of this dispute [between Cambodia and South Vietnam] is that it will deepen Cambodia's persecution complex.”Footnote 67

Where and When? The Global South, Newly Independent States, Regions, and Temporal Variation

Which kinds of events, people, and groups are most likely to be assessed using these racial tropes? Tropes are about social collectives, yet the work of national security bureaucracies is often structured in terms of governments. Indeed, state-centric analysis is common in our data source, the PDB. We therefore need to operationalize these constructs in the context of classified national security analysis that assesses individual leaders, social groups, and states.

We do this in several ways, aiming for a balance between generality and specificity. First, we explore how developments in countries in the Global South are described versus those in the Global North. Work on security and North–South relations has found that Western states have constructed a binary identity in relation to the non-West.Footnote 68 While the dichotomous construction of West/non-West is overly simplified and strewn with contradictions in practice, this binary construction is an important theoretical starting point. We are interested in how this binary opposition may appear in relatively “modern” US foreign intelligence discourse even if these categories are not mutually exclusive. The term “Global South” is not “a directional designation or a point due south from a fixed north” but rather “a symbolic designation meant to capture the semblance of cohesion that emerged when former colonial entities engaged in political projects of decolonization and moved toward the realization of a postcolonial international order.”Footnote 69 As we use the term, it refers to the actors, individuals, states, or other entities living and acting in the geographic areas comprising the Global South.Footnote 70 We stress that our use of the terms “Global North” and “Global South” is descriptive rather than prescriptive.Footnote 71

The Global South comprises a multitude of political, social, and cultural traditions and identities. To account for this variation we also use two other operationalizations. In one, we focus on states in the Global South that were formerly colonized, using the years since independence of the government being analyzed. Research suggests that America's own colonial past laid the foundation for some racial tropes, such as the childlike qualities of Filipinos during the American colonial occupation of the Philippines.Footnote 72 These historical roots may have left a legacy in how American officials interpreted events in recently decolonized polities. Postcolonial studies in IR also note the importance of tropes about immaturity regarding formerly colonized peoples and their connections to irrationality and naïveté. During decolonization, Western observers often dismissed the legitimacy and abilities of newly independent leaders.

Our third tactic is to analyze regional differences. Some racial tropes have been conceptualized as universal, applied to any group categorized as a racial “Other.”Footnote 73 Other racial tropes are unique to, or vary in strength regarding, different racial groups and regions of the world. Our discussion of belligerence notes a history of differential application across groups. Whether this differentiation will appear at a regional level is an important empirical question with unclear implications. For example, we analyze a period in which the United States fought adversaries in Asia in World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. This might have sharpened the salience of belligerence or other racial tropes regarding East and Southeast Asian states compared to other regions. Yet at the same time, an important and large literature on the particular salience of the Black-versus-White racial binary in American political culture suggests that tropes are especially common for developments in majority-Black countries in Africa.Footnote 74 Finally, geographic proximity could reduce the frequency of racial trope usage if it generates a greater perceived closeness to “Whiteness.” It is possible that some racial tropes are less associated with regions geographically closer to Europe and North America, such as Latin America and the Middle East.

In addition to considering where such tropes will be applied, we address when they may appear. It is important to assess whether their use varies over time, especially given work on the malleability of racial categories over time in the United States.Footnote 75 This is especially relevant for our data given the important milestones in the domestic politics of racial discrimination in the 1960s and 1970s, including the American civil rights movement and shifting immigration patterns.Footnote 76 Given these milestones, we might expect racial tropes to become less common over our study period. With the legal advances made during the civil rights era, it is possible that language in the foreign policy bureaucracy became more sensitive to racialization and therefore used fewer tropes in the mid-1970s than in the early 1960s. However, the persistence of such tropes even after formal legal reforms is consistent with earlier work, discussed previously, on the durability of racial bias and implicit racism. We assess these possibilities in a later subsection on temporal variation.

Methodology

Our present task is to assess whether racial tropes are more prevalent in private, bureaucratized assessments by American officials of events, leaders, and peoples in states of the Global South, in newly independent states, and in particular regions. We use a unique corpus of intelligence assessments, tailored to four US presidents during the Cold War, which provides a window into possible implicit racial bias in a key part of the foreign policy bureaucracy.

To assess this at scale and to maximize our ability to categorize the documents of interest, we use dictionary-based and supervised machine learning models that combine qualitative assessments of text with quantitative modeling. Many scholars have addressed the fundamental tensions between quantitative social science and studies of race. As Carbado and Roithmayr note, “On many occasions, social science and its classifications have served the ideology of white supremacy.”Footnote 77 We contend that because our text analysis process focuses on “the social processes that make race a salient social category”Footnote 78 rather than treating race as an uncomplicated independent variable, we avoid some of the basic issues with using quantitative analyses to better understand race and processes of racialization. We agree with earlier scholarship that quantitative social science is one method among many that scholars can use to understand the role of race in IR. Furthermore, there is some precedent for using machine learning methods to study racialized and gendered language in ways that are attentive to these contradictions.Footnote 79 To that end, we investigate a critical government document now known as the President's Daily Brief.

The President's Daily Brief

The PDB is a type of intelligence report created by the CIA in 1961 and designed to synthesize multiple information streams from around the world into a succinct and accessible overview of new developments in global affairs.Footnote 80 Each day, raw information from a range of intelligence and diplomatic reporting—including local media, reports from US outposts abroad, clandestine activities, and other efforts of countless people—is gathered by the CIA. Items deemed the most pressing with respect to global affairs are distilled into entries in the PDB. The document is delivered to the president and a narrow circle of senior officials the following day, with follow-up oral briefings taking place at a reader's request.Footnote 81

For much of their history, the PDBs have remained highly classified. This changed dramatically in 2016, when the CIA declassified several thousand PDBs dating from the Kennedy through the Ford administrations: from 17 June 1961 (the first PDB) through 20 January 1977 (the final day of Gerald Ford's presidential tenure).

The language in the PDB is ideal data by which to assess racial tropes for three reasons. First, the PDB has been one of the most sought-after products of the intelligence community. Its content was especially likely to influence how leaders perceived and acted. It is therefore an ideal corpus in which to study racial tropes. Second, the daily nature of the PDB permits granular quantitative analysis not as readily tractable with other sources. Third, the PDB presents a remarkably “hard case” for our hypotheses. Racial bias is most likely to appear in intimate and off-the-cuff commentary. While its production process evolved over time, the PDB was an all-source intelligence document built on inputs from hundreds of individual analysts and carefully vetted by officers with an editorial role. Finding racial tropes in this kind of material would show how deeply racial bias was ingrained in the everyday bureaucracy of foreign policy during the 1960s and 1970s in one of the most influential states in the international system.

Data Processing

The CIA released the PDBs as a series of images. Each PDB was converted into computer-readable text using optical character recognition software. While the particular format of the PDB varied over time, all documents were structured around what we call “entries.” The vast majority of entries are short and separate updates about developments in a particular country, ranging from one sentence to several paragraphs. A small fraction are much longer analyses of pressing situations, typically included as annexes at the end of a PDB. We use a combination of automated processes and manual review to split each PDB into its constituent entries. Our data include 4,978 PDBs comprising 45,872 individual entries.Footnote 82

The average PDB in our data contains about 8.7 redactions, most of which are one or two lines long. The CIA has made clear that redactions in historical documents are intended to protect national security interests—not to conceal material that may be normatively “inappropriate.”Footnote 83 Indeed, over 90 percent of these redactions have classification codes that explicitly indicate the need to conceal names of or details on sources, and not the core information itself.Footnote 84 Redactions should therefore not be correlated with the prevalence of racial tropes.

Each entry discussed the activities in or involving at least one country or organization. We harnessed a combination of automated methods and manual coding to identify these states or organizations. In total, 34,420 unique entries exist across our PDBs, and these entries are converted into 89,446 country-entries, which serve as our primary unit of analysis.

Identifying and Measuring Racial Tropes

Our goal is to identify language that uses tropes to reflect implicit racial biases. A fully manual process where human coders classify over 34,000 entries covering seventeen years for implicitly racialized language is prohibitively cumbersome and likely to introduce large amounts of human error.Footnote 85 We instead deploy two different techniques to measure the presence of racial tropes without having to manually evaluate each entry.

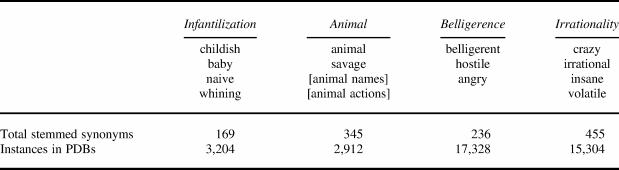

The first is a dictionary-based approach. Words like crazy, hostile, or rabid are some of the clearest reflections of racial tropes written on the page. For each trope, we identify a small set of words most directly associated with the concept of interest (Table 1). We then use a thesaurus to find all words and phrases synonymous with the core terms.Footnote 86 In the case of animal-based language, we also include a list of animals and words associated with their actions (such as “crawl,” “howl,” and “slither”). We take all the original terms and synonyms and convert them into their stemmed formats. We then count the number of times any of these terms occurs in the stemmed version of the PDB entries. This constitutes a dictionary- (and thesaurus-) based count of racial tropes.

TABLE 1. Original terms used with thesaurus to create dictionaries

Straightforward counts of term instances are an intuitive measurement strategy but likely underestimate the quantity of interest. Racial tropes can take a form that is more subtle and based on broader linguistic context. For instance, an entry regarding Uganda reports that Prime Minister “Obote has alienated every political grouping in the country. He is being kept in office almost solely by the army and security forces, to whom he must increasingly cater.”Footnote 87 Obote's alienation of all civilian supporters and his falling subject to military pressure suggest a lack of political calculus. However, the entry uses no words that our dictionary relates to irrationality.

To better measure this more complex expression of racial tropes, our second method uses supervised machine learning. Three undergraduate researchers and two graduate researchers were trained to manually code PDB entries for whether they represented the tropes of interest (coded 1) or not (coded 0). The research assistants were instructed to code an entry as featuring a trope irrespective of what particular actor—such as a head of state, other policymaking elite, political party, labor union, or large mass of people—was being described. Each entry is therefore associated with four binary variables, each of which indicates whether one of four tropes is reflected in the text. Some, all, or none of these four tropes may be present in a given entry. Our training data ultimately include 2,340 PDB entries that were manually classified.Footnote 88

We generate numerical representations of our entry texts using both a bag-of-words approach and several forms of document embedding (which produce vector representations of text that account for sequencing and semantic features of words). To maximize predictive performance, we trained and tested a total of thirteen representations of the PDB data on five different supervised learning models with five-fold cross-validation. Each trope is therefore predicted in sixty-five different ways. Further technical details on these two steps are available in Appendix 2.2.3.

The American civil rights movement, decolonization following World War II, Cold War dynamics, and shifting immigration patterns over our period of study may shape the language and norms Americans wielded when interacting with apparent foreigners.Footnote 89 To account for these fluctuations, all predictive models include a cubic spline for time. As we have already intimated, presidents’ differing personal beliefs, personalities, and styles may also impact the degree to which bureaucrats opt to use racial tropes in their reports. We account for this possibility by adding president fixed effects to all models.

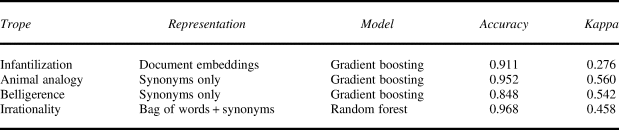

Table 2 displays which combination of the PDB entry data and supervised models produced the best predictions in terms of out-of-sample performance as measured using kappa coefficients. These numbers reflect rather strong performance given the difficult nature of coding for such implicit and intangible concepts. Appendix 2.2.4 supplies more information on model metrics and performance.

TABLE 2. Performance of the highest-quality predictive models

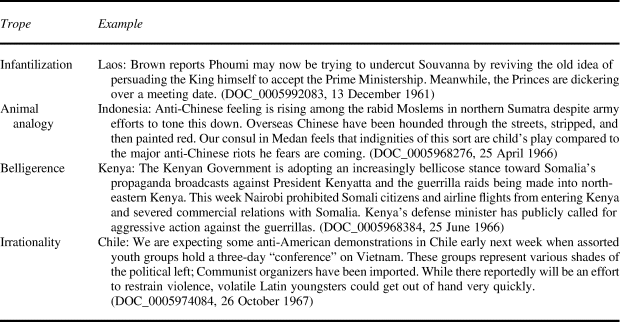

A more substantively meaningful way to validate the models’ performance is to review the entries that score high on the predicted likelihood of racial tropes. For each of the racial tropes, Table 3 displays a PDB entry that is predicted with a high probability to reflect it. Each example aligns well with our intended concept. The item on Kenya, for example, uses language (“bellicose,” “aggressive action”) which, in this context, implies a tendency to use immediate violence in reaction to nonviolent actions. The item on Chile references “volatile Latin youngsters” when describing anti-American demonstrations. Both capture belligerence and irrationality well.Footnote 90

TABLE 3. President's Daily Brief entries with high predicted probability of exhibiting key tropes

Research Design

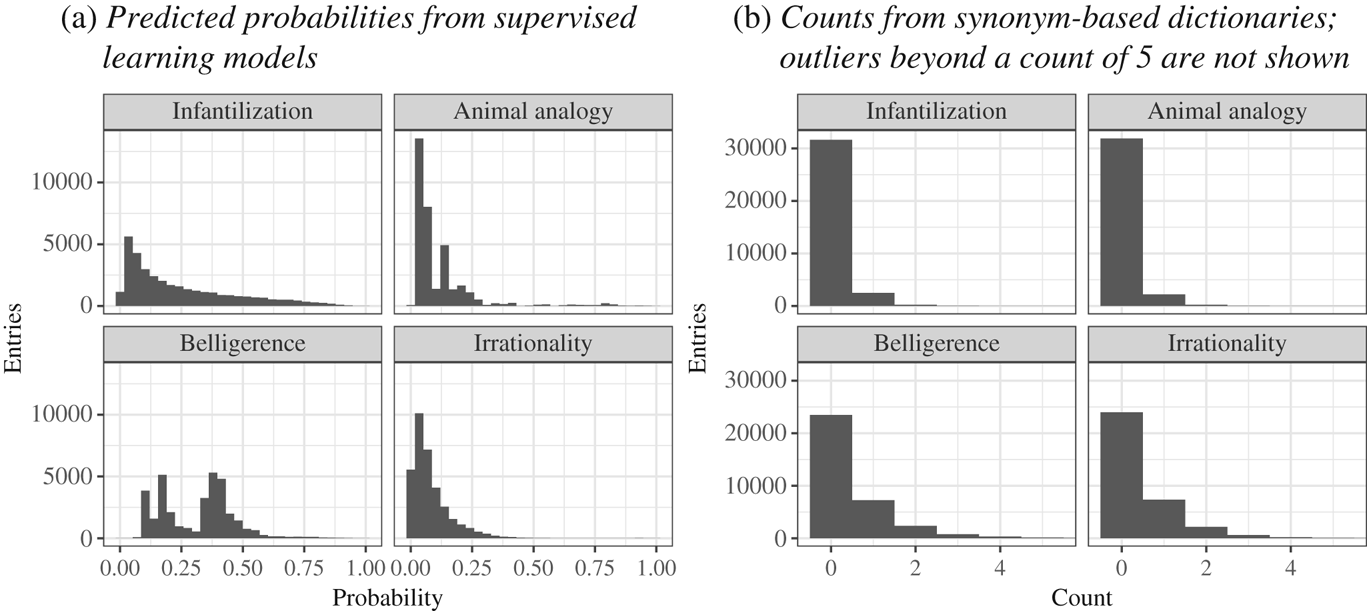

We test our argument using two sets of dependent variables. The first is the predicted probabilities of each trope from our supervised learning models. Since these values are between 0 and 1, we analyze them with quasibinomial regression models. The second is the raw counts of keywords and synonyms associated with each trope. Poisson models are used to explore these values. Figure 1 displays the distributions of these measures.

FIGURE 1. Histograms of dependent variables

Explanatory Variables

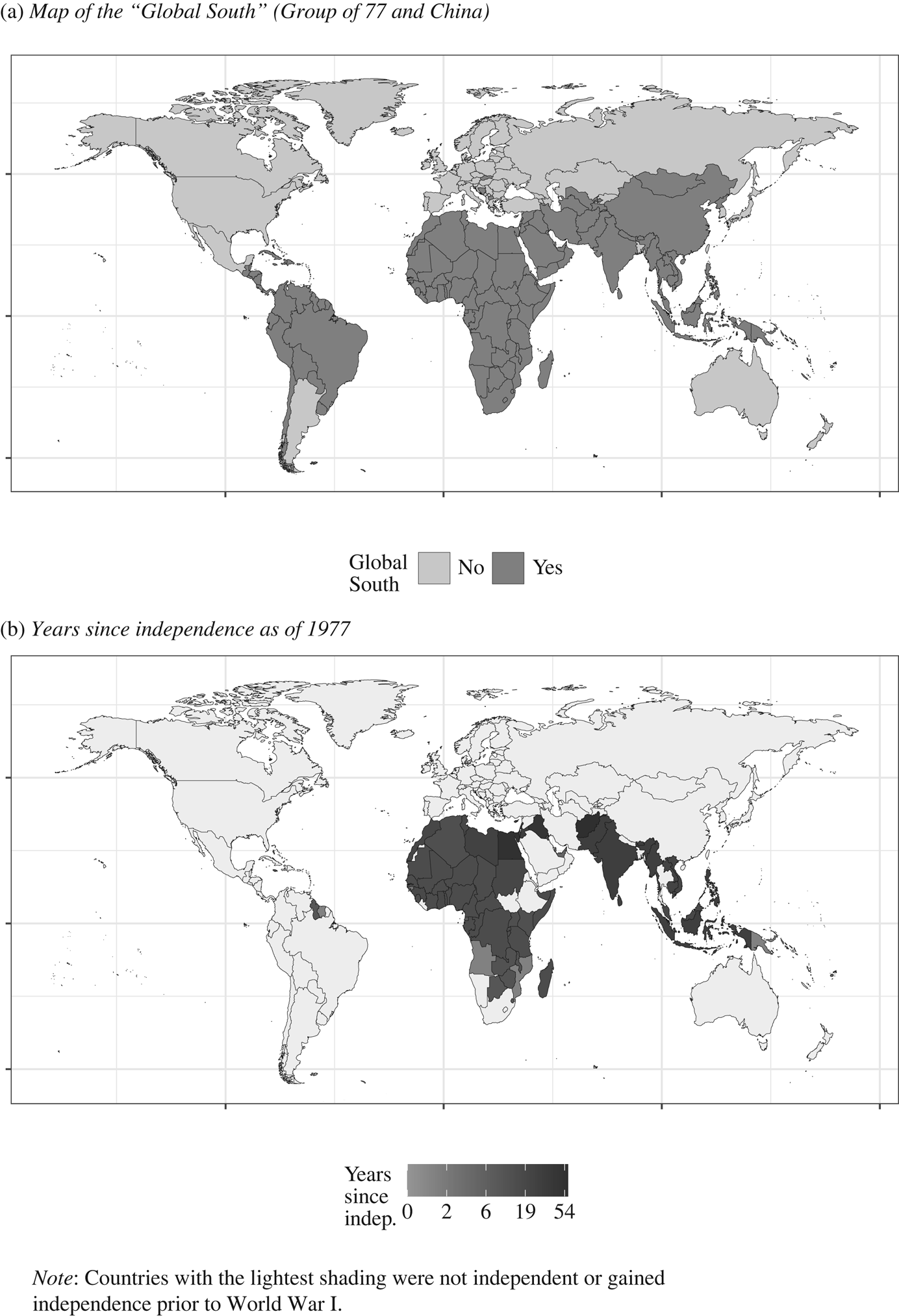

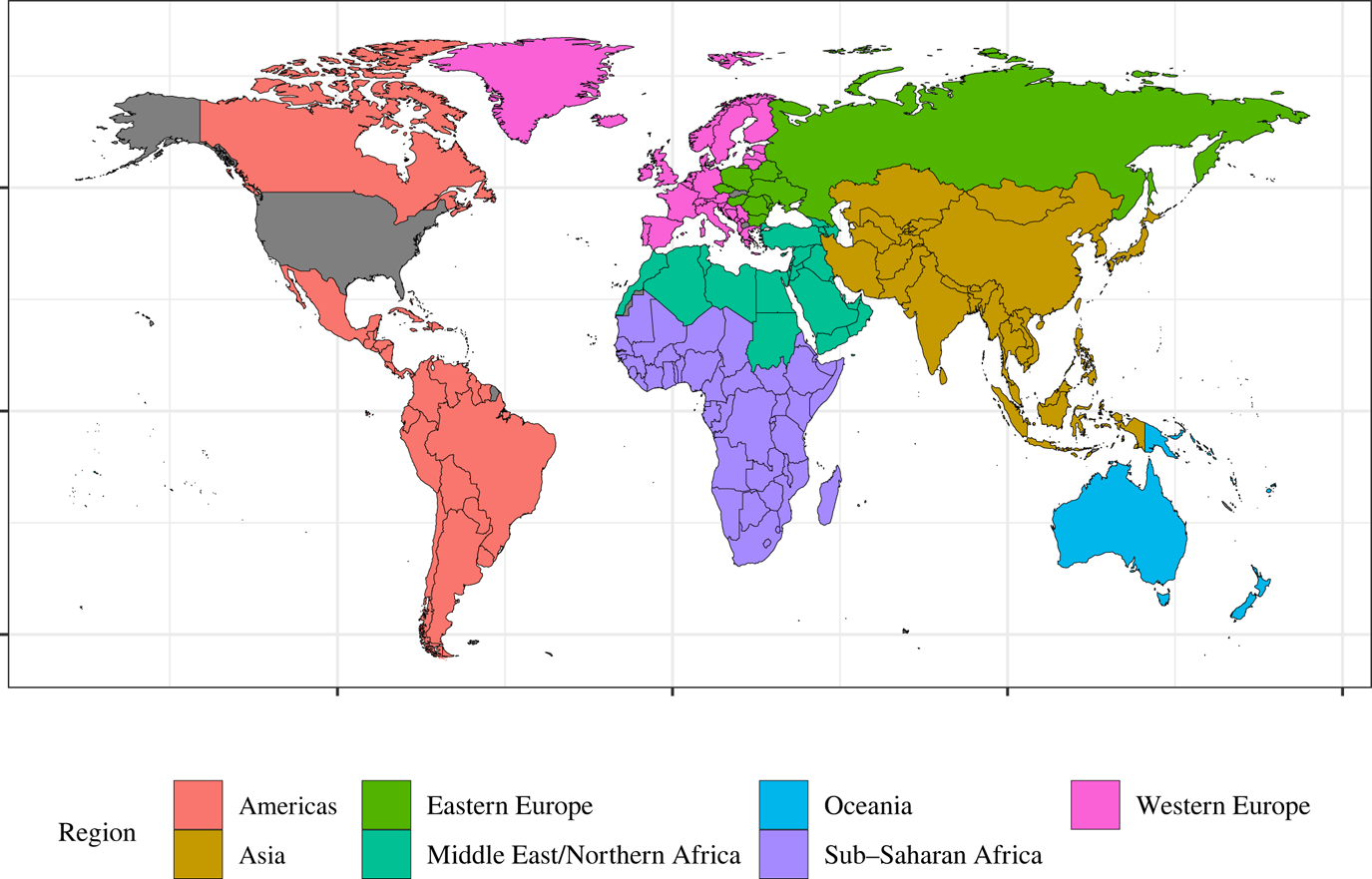

Our overarching explanatory variable is the presence or absence of racialized Others as the object of analysis by national security intelligence professionals. As noted, we operationalize this concept in several ways. We first focus on whether a given intelligence summary is addressing developments in countries associated with the global south (Figure 2a). This list encompasses members of the Group of 77 and China, as listed by the United Nations. About 76 percent of our entries mention at least one country in the Global South.

FIGURE 2. Depictions of explanatory variables

We also consider how recently the country obtained independence. Here we expect that recently decolonized states are more likely to be described using racial tropes than states with a very distant (or no) colonial history, in part because of the ideas about readiness to govern or (im)maturity noted earlier. We thus identify the country assessed in a given item, its status in or outside the Global South, and the year in which it is assessed compared to its year of independence. For each country-year, we calculate the (logged) number of years since independence using the Issue Correlates of War Project's Colonial History Data Set.Footnote 91 We do this only for states that obtained independence after World War I.Footnote 92 Figure 2b illustrates this measure of years since independence. A subsequent section assesses racial trope prevalence across different world regions.

Control Variables

The fully specified versions of our models control for various factors that could influence whether descriptions invoke our tropes of interest independent of implicit racial bias. First, we account for any conflict that may have occurred in countries around the world because such events could easily lead to different language. We use the Uppsala Conflict Data Program's PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset.Footnote 93

Second, we address differences in regime type. The literature suggests that non-democratic states may be perceived by elites in democracies as especially aggressive, irrational, or unpredictable. In an influential constructivist reformulation of the democratic peace, for example, Risse argues that leaders in Western democracies judge foreign threats based on regime type and view autocratic states as part of an Otherized collective identity with a “predisposition toward violence and, hence, the feeling of being threatened.”Footnote 94 Another account argues that “liberal elites view other liberal states as reasonable, predictable, and trustworthy” while “illiberal states…are seen as unreasonable, unpredictable, and potentially dangerous.”Footnote 95 We therefore include a measure of the regime type of the country being assessed in the PDB. We use the Polity data set,Footnote 96 creating a dichotomous variable that is 1 for a country that is a democracy (with a score of 6 or higher) and 0 otherwise.

Third, we add additional controls that account for leaders. Intelligence assessments about specific individuals with dominant domestic control may be more likely to highlight psychological dispositions (such as irrationality) or personality traits (depending on context, belligerence), or invoke analogies.Footnote 97 We capture personalism using the Autocracies of the World Dataset.Footnote 98 For each country-year, the data set uses a three-tier measure for the degree of personalism in the regime. Similarly, entries that specifically mention the leader of a state may use different descriptive and perhaps intimate language. We use the Archigos data set to identify any instances of a leader mention.Footnote 99

Fourth, we account for each country's relationship with the United States. Those with extensive interactions with American officials could be discussed more sympathetically and with more nuance. For example, the foreign policy bureaucracy may be more likely to give allies the benefit of the doubt. Using data from Lebovic and Saunders, we include measures of us trade and us military aid, and a binary variable for whether the country has a us defense pact.Footnote 100

Fifth, longer passages inherently contain more words, and thus more room for racial tropes or themes. We therefore include a measure of (logged) entry length.Footnote 101 Finally, all our models include country fixed effects and cluster standard errors by country.Footnote 102

Results

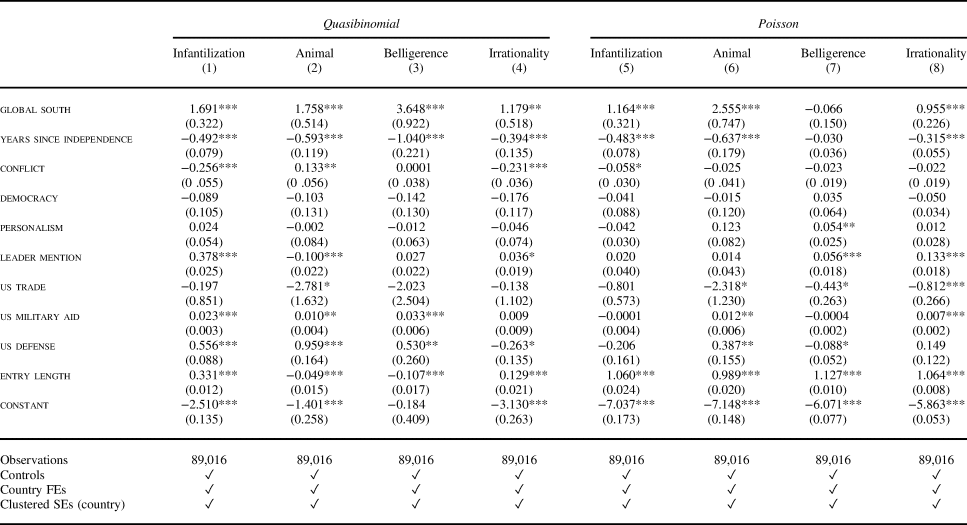

Table 4 presents our primary findings for Global South and newly independent countries.Footnote 103 Models 1 through 4 reflect quasibinomial regressions where our predicted probabilities from the supervised learning models are the dependent variable; models 5 through 8 report Poisson regressions using counts of words and phrases synonymous with each trope. We first interpret the findings for our main independent variables of interest, including substantive significance. We then discuss notable findings regarding several control variables.

TABLE 4. Results of regressions on relationship between racial tropes in PDB entries and measurements of racialized Otherness

Overall, we see compelling evidence supporting most of our expectations. Across nearly all specifications, we find the expected direction of association for analysis of foreign policy development in Global South states and in newly independent states. PDB entries discussing developments in countries associated with the Global South are far more likely to contain language that invokes infantilization, animal qualities, belligerence, or irrationality compared to discussions of Global North countries. The negative coefficient for years since independence suggests that racialized language is more commonly used when interpreting developments in polities with fewer years of independent rule. On average, as this interval increases, the four racialized tropes appear less frequently. This is strong and consistent evidence of systematic differences in how the US foreign policy bureaucracy interpreted developments in states they saw as racialized “Others,” as defined by the Global North/South binary and by years since decolonization.

The sole model which does not conclusively conform to our predictions is model 7, which assesses belligerence using a dictionary approach. Unlike the other tropes, items associated with the Global South or newly independent states do not appear to be associated with a greater number of dictionary-based belligerence terms in this specification. There could be two reasons for this. First, given that model 3—which relies on supervised learning methods to measure the presence of the belligerence trope—does show a strongly positive correlation, a dictionary-based approach may simply be insufficient to properly capture the concept and associated terminology for belligerence.Footnote 104 For example, there may be too much overlap in terminology between items about conflicts in general and items that showcase the belligerence trope. Second, this result may reflect the more complex relationship between racial tropes and belligerence. Implicit bias may lead some groups of racialized Others to be characterized in PDBs as effeminate or docile rather than belligerent. Such an interpretation would cut against language that implies belligerence even though implicit racial bias was having effects. Either way, we find quite strong support overall for our theoretical predictions.

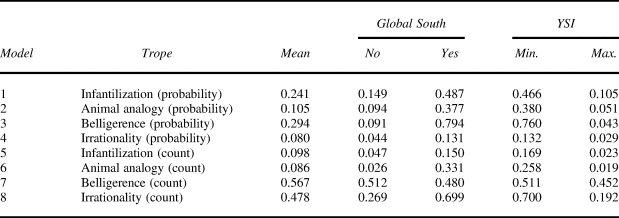

In terms of substantive significance, Table 5 presents results based on these main effects, which speaks to the difference in racial trope frequency made by our core independent variables. Assessing both global south and years since independence, we take each model from Table 4 and ramp an explanatory variable of interest from its minimum to maximum values while holding all other factors constant at their mean values.Footnote 105 The quasibinomial models, which use probabilities as the outcome, offer the most intuitive evidence of meaningful effects.

TABLE 5. Predicted values from models in Table 4

First consider the global south variable. The likelihood of seeing a racial trope is between three and nine times higher for entries discussing the Global South than for items about events in the Global North. In the Poisson models, which use counts, the number of dictionary terms associated with racial tropes—with the exception of belligerence—increases by a factor of between 2 and 13 for interpretations of Global South events and people compared to developments in the Global North.

Now consider the column labeled YSI (years since independence). Here the minimum refers to the first year after decolonization, while the maximum refers to the longest observed duration after decolonization. The predicted values suggest that states see dramatic declines in PDBs’ use of racial tropes as they accumulate years since independence. For example, the propensity to see any of the four racial tropes in internal American assessments falls by between 70 and 90 percent (again, with the exception of model 7) as a state advances from initial independence to a few decades of self-rule.

Several control variables merit discussion as well. Most surprising, we find a conspicuous absence of explanatory power for regime type. As noted, some scholars of the democratic peace posit that democratic observers see nondemocratic leaders as unpredictable or unreasonable. One recent study specifically found that dictators like Saddam Hussein have helped build an association “between regime type and perceptions of madness.”Footnote 106 Our findings suggest irrationality and other tropes have racial rather than regime-related roots. After accounting for whether countries in question are in the Global South or are newly independent states, regime type does not seem to affect the likelihood that American foreign policy observers perceive irrationality, belligerence, or related qualities. This null result is potentially quite significant because it suggests that what has previously been attributed to domestic-institutional difference was likely driven by racial difference. Put differently, when it comes to invoking child-related metaphors or attributing irrationality, it may matter more that Saddam Hussein is perceived as a racialized Other than that he is an autocrat.

Beyond regime type, we find evidence that the invocation of leaders, in general, affects the likelihood of reaching for racial tropes.Footnote 107 In more than half of our models, entries that explicitly mention leaders are likelier to feature racial tropes, with particularly consistent evidence for irrationality. One interpretation is that writing which focuses on heads of state highlights a specific person and their actions, to which they are more likely to assign trope-related qualities than a large group or a less personalized institution (that is, the government). Note that even after accounting for heads of state, our results for global south and years since independence persist.

We also assess whether geopolitics influence the way foreign policy events are interpreted. We find that countries receiving military aid from or in defense pacts with the United States consistently see more use of racial tropes. This is at odds with an intuition that overlapping preferences and dense interactions might reduce the use of stereotypes. One possible explanation is the frequent power asymmetry between the United States and its allies. Compared to a random dyad, allies with a security dependency on the United States during the Cold War might be more likely to be seen as inferior and trigger an attitude of paternalism. We also assess whether such tropes are more prevalent in PDB discussions of geopolitical conflict. Our results here are mixed. In four of the eight models, we observe a negative relationship between presence of conflict and racial trope usage. In the others, no statistically significant relationship exists. The former offers mild support for a counterintuitive relationship in which more peaceful periods feature more frequent references to irrationality, belligerence, and the animal- and child-related metaphors.

Robustness

One potential concern with our results is that what appears to be racialized use of tropes is a byproduct of an association between countries and particular subjects or topics in the PDB. For instance, discussions of certain topics (domestic unrest, student-led protests, labor strikes) could be more common for Global South and newly independent countries and more likely to feature language that implies belligerence or irrationality.Footnote 108 Accounting for the relative prevalence of topics would allow a more precise estimate and address a possible false positive.

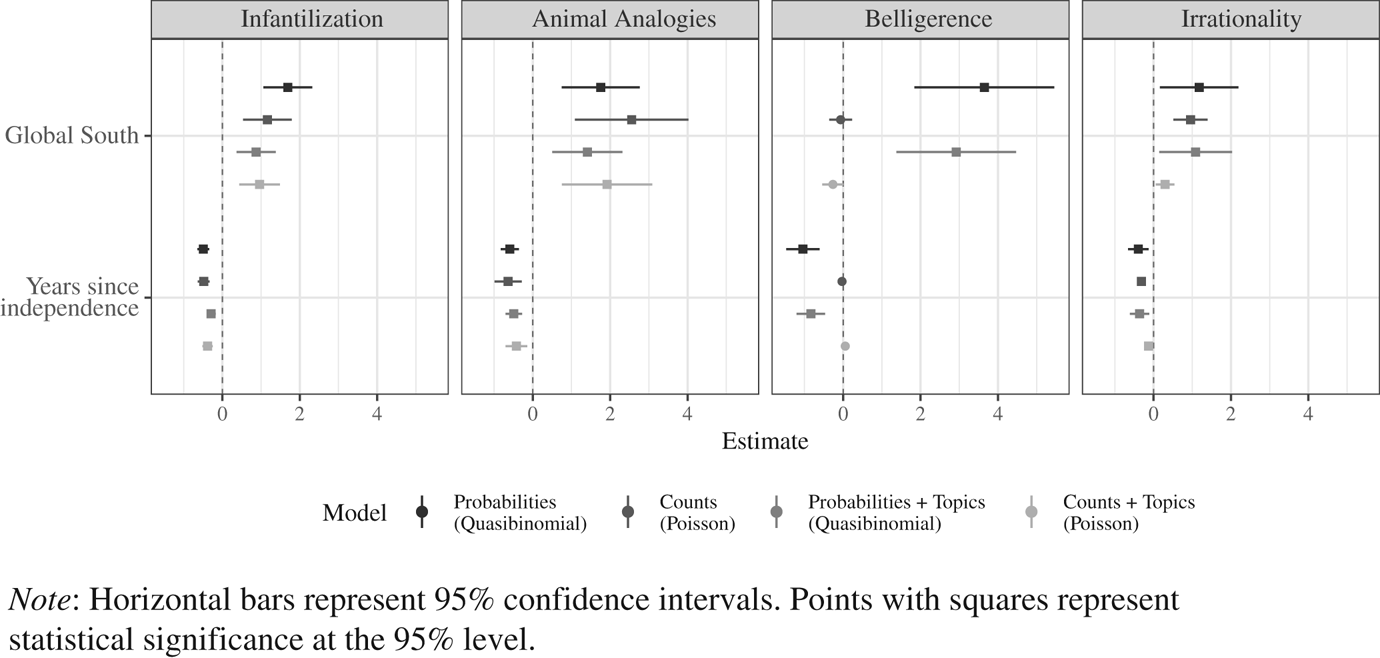

As a robustness check, we address the frequency of substantive topics in the PDB by incorporating the results of a sixty-five-topic structural topic model (STM) for the text of the items in the PDBs.Footnote 109 Our STM identified an array of substantive topics, including naval affairs, ministerial politics, coups, oil, monetary affairs, and missiles. We performed two tests to validate the coherence of our topics, as well as the labels we created for each topic. Accuracy for both tests was around or above 90 percent. In our statistical analysis, we include propensities for twenty-seven of the sixty-five topics from the STM. The remaining thirty-eight topics were not included because they were synonymous with countries (which we already capture using country fixed effects) or identified technical aspects of the PDB rather than substantive items.Footnote 110 Figure 3 features both the estimated coefficients from the previous models in Table 4 as well as coefficients from new models which include the topic-prevalence measures. Our findings are unchanged by this addition.

FIGURE 3. Coefficient plots of regressions in Table 4 and additional models that include topic-prevalence measures from the structural topic model

A second concern with our approach is specific to decolonizing states. It is possible that any linguistic patterns in remarks about these countries that we attribute to racial tropes are actually driven by a view about new versus seasoned leaders that is unrelated to race.Footnote 111 This could mean that tropes are linked to individual people and based on time in office rather than racial bias, though we suspect the latter still plays a role. In Appendix 4, we show that our results are unchanged after accounting for leader tenure. We also demonstrate that our results for years since independence remain unchanged when we analyze only countries that were formally decolonized, which omits PDB entries where our measure of years since independence may be less reliable.

Regional Variation

We now assess the potential for heterogeneity in the use of racial tropes in reference to different regions of the world. Doing so allows us to go beyond the more global-level groupings in our previous analysis. Regional variation could reflect how some racial stereotypes are about specific racial groupings. A belligerence trope may be less likely in PDB discussions of states with a majority population that has been historically stereotyped as peaceful or lazy. We also note the specific history of racialized stereotypes of East Asians in the United States, both from its colonial period and from later conflicts. Region-specific analysis also allows us to assess whether the particularly salient Black-versus-White racial binary in American domestic politics generates a more prevalent use of tropes for majority-Black countries in Africa. Figure 4 depicts our initial disaggregation of countries by geographic region.Footnote 112

FIGURE 4. Geographical regions used in the analysis

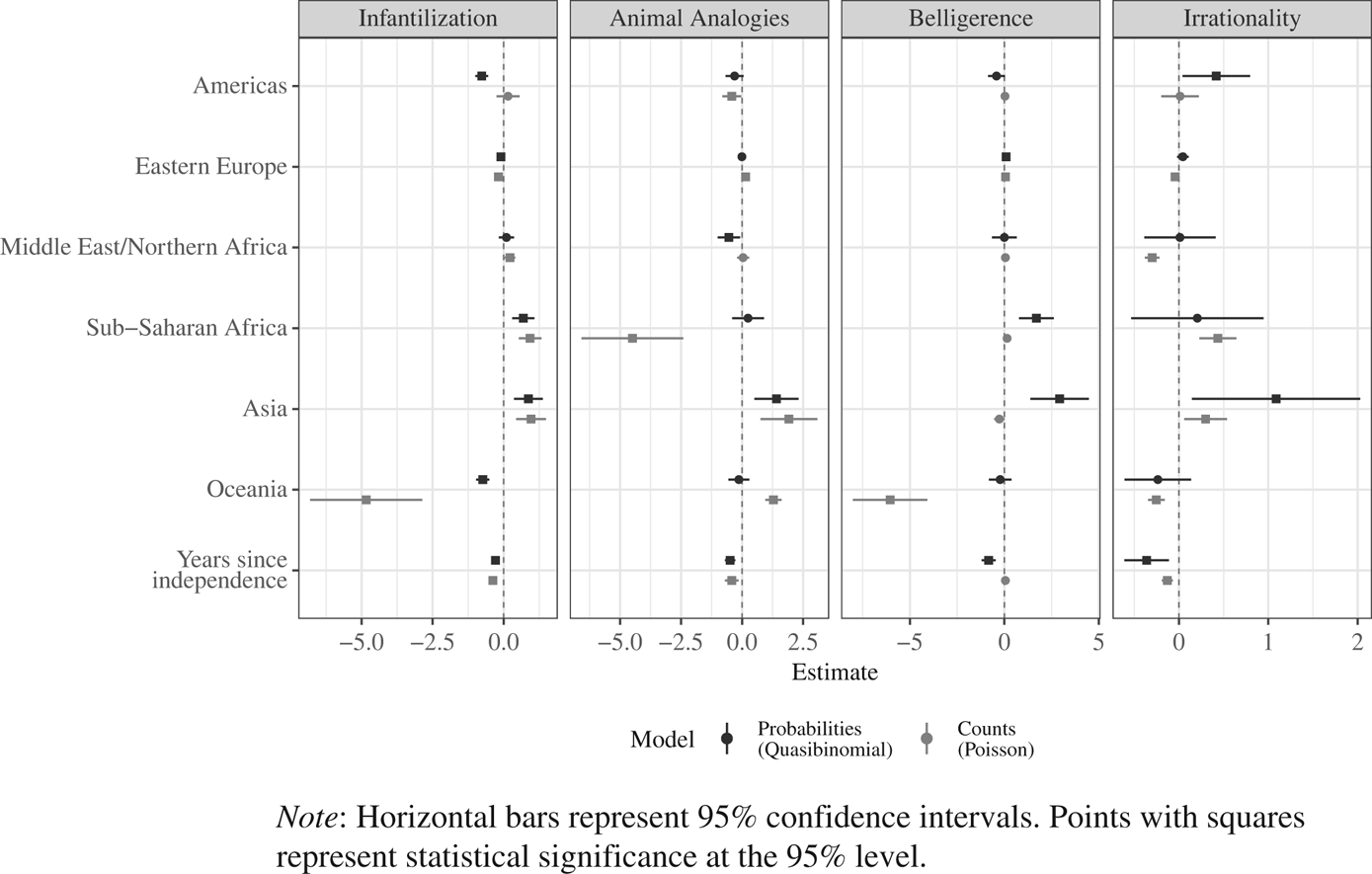

The region-level results for our four tropes appear in Figure 5. The coefficient plots are from regressions using region as the independent variable.Footnote 113 While the full results are in the appendix, we address several regions of interest here.

FIGURE 5. Coefficient plots of regressions disaggregating countries by region

Interpretations of events in Asia appear to drive much of the positive findings. Across all four tropes, the coefficient for Asia is especially positive. Regarding belligerence, these findings also suggest that a stereotype of passivity or pacifism is far less potent than a racial trope of aggression and belligerence, perhaps influenced by US conflicts before and during our study period. These results may be due to the concentrated US foreign policy focus in the region at the time, particularly concerning the Vietnam War.Footnote 114

The relative lack of racial tropes regarding two regions—the Americas and the Middle East and North Africa—is important to note. For all four racial tropes, the Americas display largely null or slightly negative coefficients for trope prevalence. This provides some evidence that developments in Latin America, with its longer history of independence and more complex racial categorization, are less subject to racial tropes in the 1960s and 1970s. We also find evidence that racial tropes are no more prevalent in the Middle East and North Africa. The specific focus of the US foreign policy establishment on East Asia at the time may explain this null finding. However, the particular time period also matters. We can only observe writing from the middle of the Cold War, but highly salient racial tropes relevant to immigration from Latin America and the attacks on 9/11 arise after our data.Footnote 115

The results for Sub-Saharan Africa are mixed. For some tropes, such as infantilization, PDB items are more likely to reach for a racial trope when discussing events in this region. We also see inconsistent evidence of greater likelihood to invoke belligerence tropes (supervised learning model) and irrationality (dictionary-based model). For other models and for animal analogies, there is a null effect or even a negative correlation.

Temporal Variation

Racial tropes and racial categories themselves are not immutable or permanent. In the United States in particular, research on racial formations suggests the importance of temporality in the categorization of racialized Others and the salience of particular features and stereotypes. While our measures and analyses make efforts to account for time's impact on these overall prevalences, assessing temporal variation is especially important given our study period. The rise of the civil rights movement and changes in immigration patterns during the 1960s and 1970s may have diminished or altered the racial tropes in circulation within the US foreign policy bureaucracy.

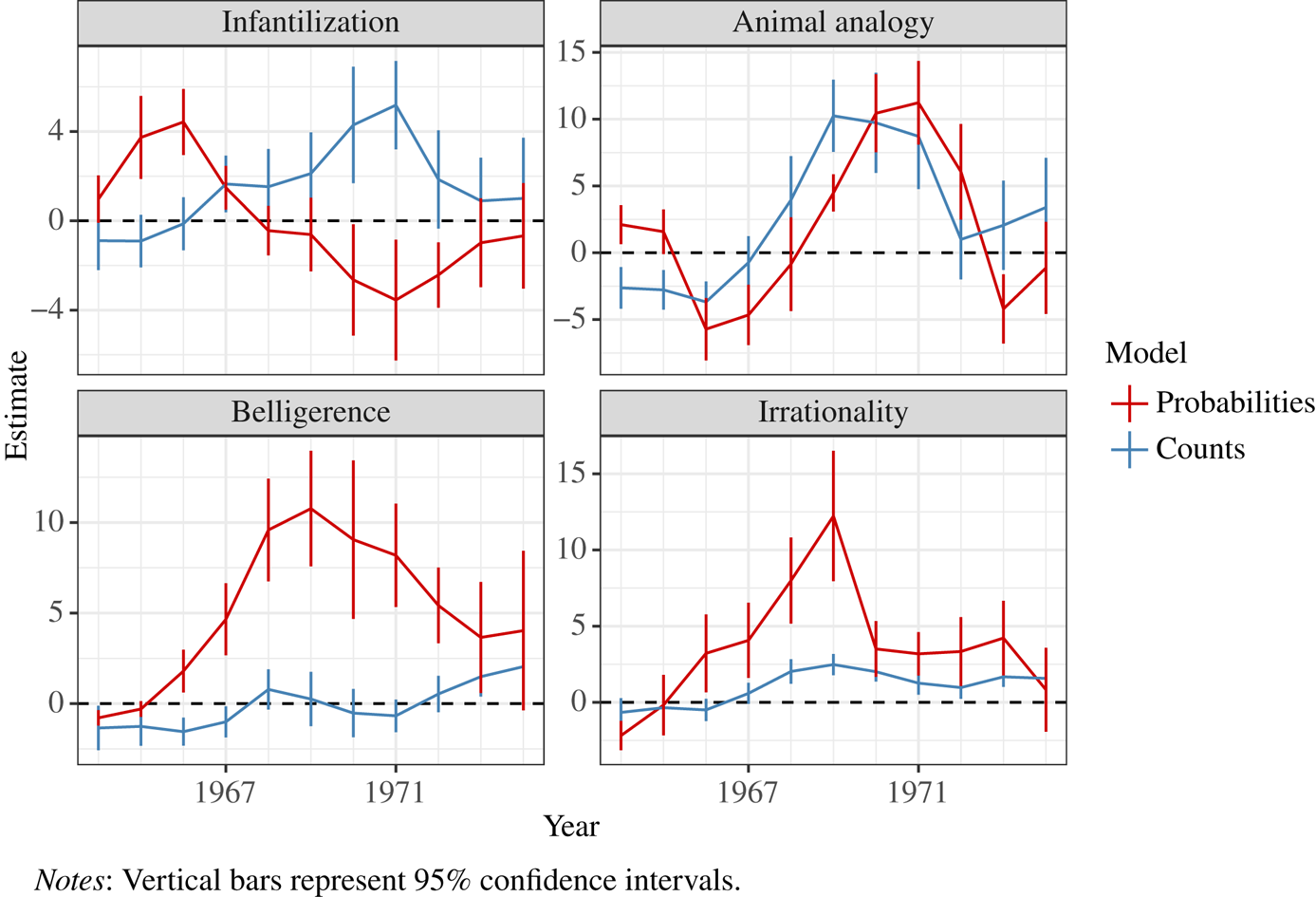

To address this, we perform a rolling window regression. We repeatedly apply a subset of our aforementioned models to all entries inside a seven-year window, shifting it one year at a time from 1961–1967 to 1971–1977. Doing so allows us to assess how a coefficient changes in a continuous manner across the temporal span of the data. We focus here on the Global South operationalization.Footnote 116

Figure 6 plots the series of coefficient estimates we obtain through this exercise, including both supervised learning model and dictionary-based measures. We find no clear evidence of a secular decline over time in the use of racial tropes to interpret events in the Global South. The peaks of the four tropes differ in important ways. We also see a continued positive correlation into the mid-1970s and, in some cases, an increase in prevalence in this period.

FIGURE 6. Coefficient estimates for the global south variable, using a moving seven-year window and full models accounting for topics

Beyond these overall patterns, we find interesting results across measures and within specific tropes. For most tropes, we see distinct patterns for the separate measures from probability-based and count-based models. While results largely overlap for animal analogies, we observe stronger effects for belligerence and irrationality measures derived from the supervised learning model approach. This suggests that nations associated with the Global South were discussed using subtler expressions of these tropes. A diverging pattern arises for infantilization, which may reflect a shift from more implicit forms of racial bias to more overt ones that can be identified through the use of specific words—an unexpected trend.

The temporal fluctuations for animal analogies, belligerence, and irrationality are striking. Given the rising prominence of the civil rights movement and associated changes in racial norms in the United States, we may expect high or even peak usage of these tropes in the early 1960s. Instead, we often find null or even slightly negative effects over this period; many of the strongest positive findings emerge in the late 1960s and into the 1970s. For several of the tropes, the coefficients related to the Global South peak around 1969–1971. A provisional interpretation is that some constellation of events and American policy initiatives—for example, the turn to exiting Vietnam and the rise of detente with the Soviet Union—created conditions in which the use of tropes was more common.Footnote 117

Conclusion

This article reports important and systematic evidence of implicit racial biases across seventeen years of the President's Daily Brief. Even when controlling for a range of circumstances and other features that can affect language used in a foreign policy bureaucracy, we find consistent evidence that foreign policy events are interpreted using common racial tropes. Across several dimensions and using multiple measures, we show that material crafted for top leaders in the United States was more likely to use analogical and non-analogical expressions of immaturity, animal-like qualities, belligerence, and irrationality when describing events in the Global South, newly independent states, and for some regions.

Identifying such patterns in bureaucratic artifacts like the PDB is especially powerful evidence of how deeply ingrained racial tropes were in elite American views of foreign affairs during the Cold War. We provide a unique form of evidence, using a novel empirical method, that race and racism structured international politics at the level of the foreign policy bureaucracy. Previous research has done much to establish the consequences of racialized perceptions for state behavior, including in domestic policies, alliance dynamics, conflict behavior, and economic policy. Our findings complement these, helping establish the particular form of racial bias and its appearance in highly bureaucratized settings in the 1960s and 1970s. While we do not test the downstream causal impact of these tropes, other work suggests that they could have important effects on how leaders interpreted and responded to foreign developments.

Beyond the academy, our findings are relevant to modern foreign policy debates. When he was president, Donald Trump used explicitly racist language and supported White nationalist groups in the United States. More subtle use of racialized and gendered tropes also appears in contemporary foreign policy debates. These include the themes we analyze, such as infantilization, animal analogies, irrationality, and belligerence. For example, a Foreign Policy article on rebel group activity in the Democratic Republic of the Congo said that low-ranking rebels “taking up arms and being combatants is also simply what they do.”Footnote 118 Even the language of the United Nations can invoke related tropes. Former UN secretary-general Kofi A. Annan adopted a paternalistic framing in saying that Haiti was “clearly unable to sort itself out” and therefore required continued UN intervention.Footnote 119 Scholarship has also shown the role of racially inflected framing in the American wars in Iraq.Footnote 120 This and other studies which offer new ways to identify subtle forms of racial bias can help inform the development of analytic and decision-making tools that counteract these effects.

Our data and findings suggest several directions for future research. First, scholarship could assess the generalizability of these findings to other parts of the foreign policy bureaucracy and with respect to other dimensions of identity. The same methods could be used on different corpora of declassified texts to assess the prevalence of tropes in diplomatic correspondence within the State Department, in private communications to allied foreign leaders or in embassy dispatches, and in military writing. Such work could also help begin to trace how language infused with bias based on race, gender, sexuality, or other dimensions moves within government deliberations. Our findings cannot assess whether these racial formulations migrate to venues like the National Security Council;Footnote 121 future work could use linguistic similarity to connect patterns across bureaucracies and within internal deliberative settings.

Second, subsequent work should build on our findings to better understand region-specific stereotypes and their change over time. For example, while we find null results regarding PDB writing about Latin America, this is at odds with a long history of American hegemony and racism toward Latin American countries, leaders, and immigrants.Footnote 122 A more focused analysis of this history and the tropes and language it gave rise to might be able to identify other forms of implicit racism we do not address. Similarly, research has noted a range of traits associated with East Asian societies and immigrants, as triggered by the “yellow peril” construct in early-twentieth-century America.Footnote 123 Prospective work could focus more attention on the varied, even contradictory tropes for this specific region. The addition of text corpora specific to such regions, such as State Department regional desk records, would help in this regard.

Third, scholars can do more to assess how racial tropes evolve. We find evidence of distinct patterns among the four tropes we analyze from the early 1960s to the late 1970s, including several that peak around 1969. However, our ability to assess change is limited by the seventeen-year period that our data capture. To address how racialized thinking regarding foreign affairs has evolved, future work could identify corpora of declassified materials, such as the Foreign Relations of the United States series, which speak to a much longer period in American history.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EVKPL3>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818324000146>.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors and anonymous reviewers, as well as the attendees at the 2021 annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, the 2021 annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, and the 2023 University of Notre Dame Race in International Relations Workshop for valuable feedback. We are grateful to Allen Abbott, Joshua Byun, Austin Christhilf, Matthew Conklin, Casey Epstein, Lucia Geng, Andy Hatem, Ethan Hsi, Viivi Jarvi, Sophia Kierstead, Jonathan Kim, Peyton Lane, Russell Legate-Yang, Jordan Pierce, Diego Quesada, Spencer Reed, Sania Shahid, Ivanna Shevel, and Ari Weil for research assistance. Authors are listed in alphabetical order to reflect equal contribution.

Funding

We are grateful for financial support from the Center for International Social Science Research at the University of Chicago.