INTRODUCTION

In March 1878, Emília Soares do Patrocinio and other food vendors published a petition in the Brazilian newspaper Jornal do Commercio opposing the exorbitant increase in rents at the local market.Footnote 1 For decades, Emília had been selling vegetables and poultry at many different stands at the port market (Mercado da Candelária), and, by doing so, had become relatively wealthy.Footnote 2 When she died in 1885 she bequeathed three houses, twenty slaves, jewellery, and money to her heirs.Footnote 3 It was a remarkable career for a West African woman shipped to Brazil in the first half of the nineteenth century and who had spent a great part of her life in slavery before buying her freedom in 1839. Emília Soares had hired a stand at the market, which meant a move to formalized areas of food selling. It required capital and was the mark of a relatively high social position for a woman like her. The case of Emília's upward mobility is indeed remarkable in its rarity, since most of the Quitandeiras had only a stand at the beach or worked as small ambulant traders under precarious living conditions. African women involved in the street-food sector were called Quitandeiras. At this point it is helpful to take a linguistic sidestep to clarify the origin of the word. Quitanda is a loan word adopted from Kimbundu, the second largest Bantu language, and means “to sell”.Footnote 4

Most of those who sold food with a permit (licença municipal) were male slaves.Footnote 5 There was a great variety among vendors. Some were slaves who went out to sell foodstuffs in their free time, on Sundays, or at night, while others worked on the streets with their masters’ permission. Some free and unfree persons worked with an official licence (licença municipal), many as unlicensed vendors. As slaves, they had the opportunity to accumulate sufficient money to buy their freedom, often through activities in the food sector. Then, many of them continued with this business.

In recent decades, female street vendors have been studied by a number of Brazilian scholars, who have shed light on urban slavery, domestic slavery, and other forms of unfree labour. From a micro-historical perspective, these studies incorporated labourers who were neglected by traditional historical studies and showed through both the study of particular cases and qualitative studies the agency of both enslaved and free/freed African women who took part in local trade, relying on their transatlantic experiences. These studies commonly focus on community building among urban slaves and the formation of a West African diaspora. The group of Mina vendors and their social mobility is the most studied group of these women.Footnote 6 The Mina came from the West African Coast, were sold in great numbers from Bahia to Rio de Janeiro, and “stood out from the rest of the slaves and freed persons for their strong ethnic links and ethnic-based organizations”.Footnote 7

There are, however, few studies that explore street-food vending in Rio de Janeiro as a social, everyday practice that was central for feeding the labouring population of the port city. Since cooking is not only one of the most time-consuming and widespread kinds of labour in history, it should not be underestimated how labour intensive the provisioning and feeding of a fast-growing port city probably was.Footnote 8 Furthermore, the focus on reproductive labour hints at another aspect often overseen in earlier studies of labour history, namely the fact that “not every kind of work aims at a market and not every kind of work is arranged on a market”.Footnote 9 Especially in the food sector, different kinds of labour existed in parallel to one another (slaves, former slaves, wage-earning slaves, free and semi-free wage labourers, self-employed women, and women as unpaid reproductive workers within a household).Footnote 10 In general, according to Rockman, all of “these workers lived and worked within a broader system that treated human labor as commodity readily deployed in the service of private wealth and national economic development”.Footnote 11 Food sellers were not merely passive victims of slavery and marginalization, but a disparate group of capable actors, who created a gendered niche of economic opportunity, through the capitalization of their cooking and vending skills.Footnote 12

Both the absence of an effective government food infrastructure and the inability of the police to control public spaces offered opportunities for small (informal) businesses, especially in the port area.Footnote 13 These businesses had a huge impact on the development of and change in the city's food culture. As in other port cities, European culinary customs were very influential in the nineteenth century, but through Rio de Janeiro's special role in the late transatlantic slave trade the Quitandeiras brought with them their own knowledge and culinary practices.Footnote 14 This article explores, in particular, the ways in which they not only introduced African cuisine, but also created city spaces for workers, despite the forces opposing them. The vending environment became an important space of sociability, for multi-ethnic inhabitants, port labourers, and foreign visitors.

This article argues that, despite all their efforts to modernize and control the city space, the city's authorities were unable to prevent the selling of food on the streets, since their intentions were undermined at a local level.Footnote 15 On the contrary, the street-food vendors became a highly visible part of the life of the city. The planning of Rio de Janeiro into a modern metropolis was forced to adapt to the Quitandeiras, who refused to relinquish their space in the city. Furthermore, since Rio de Janeiro was a globally connected port city, the reputation of the Quitandeiras, as a highly visible part of the city, reached distant parts of the world. The Quitandeiras can be regarded as part of a larger heterogeneous group of street working women who gained visibility and recognition in parts of contemporary popular culture, an aspect that until now has been completely overlooked.

In contrast to studies that focused on the ethnic diversity of workers, a perspective that highlights the differences between the vendors, this study concentrates on the similarities between very heterogeneous groups of free and unfree workers in their everyday struggles for survival on the streets, which was a result of their shared marginalized status.

The first part focuses on food, consumers, and the labour process of selling food on the streets. The second part centres on the urban space of Rio de Janeiro. Street vendors constantly had to fight for their spaces in the city against municipal authorities, the police, but also against other vendors, because public space then, as now, was an “indispensable resource of income”.Footnote 16 The third part is focused on the gendered nature of street food, because the popularity of female hawkers was closely connected to their being women. I will combine recent approaches in research on aspects of street vending in urban contexts, case studies from Rio de Janeiro, and new sources mainly from contemporary Brazilian newspapers.

Rio de Janeiro, but also many other port cities, relied on the reproductive labour of women; this is often overshadowed by the much more studied male port labourers and sailors.Footnote 17

STREET FOOD

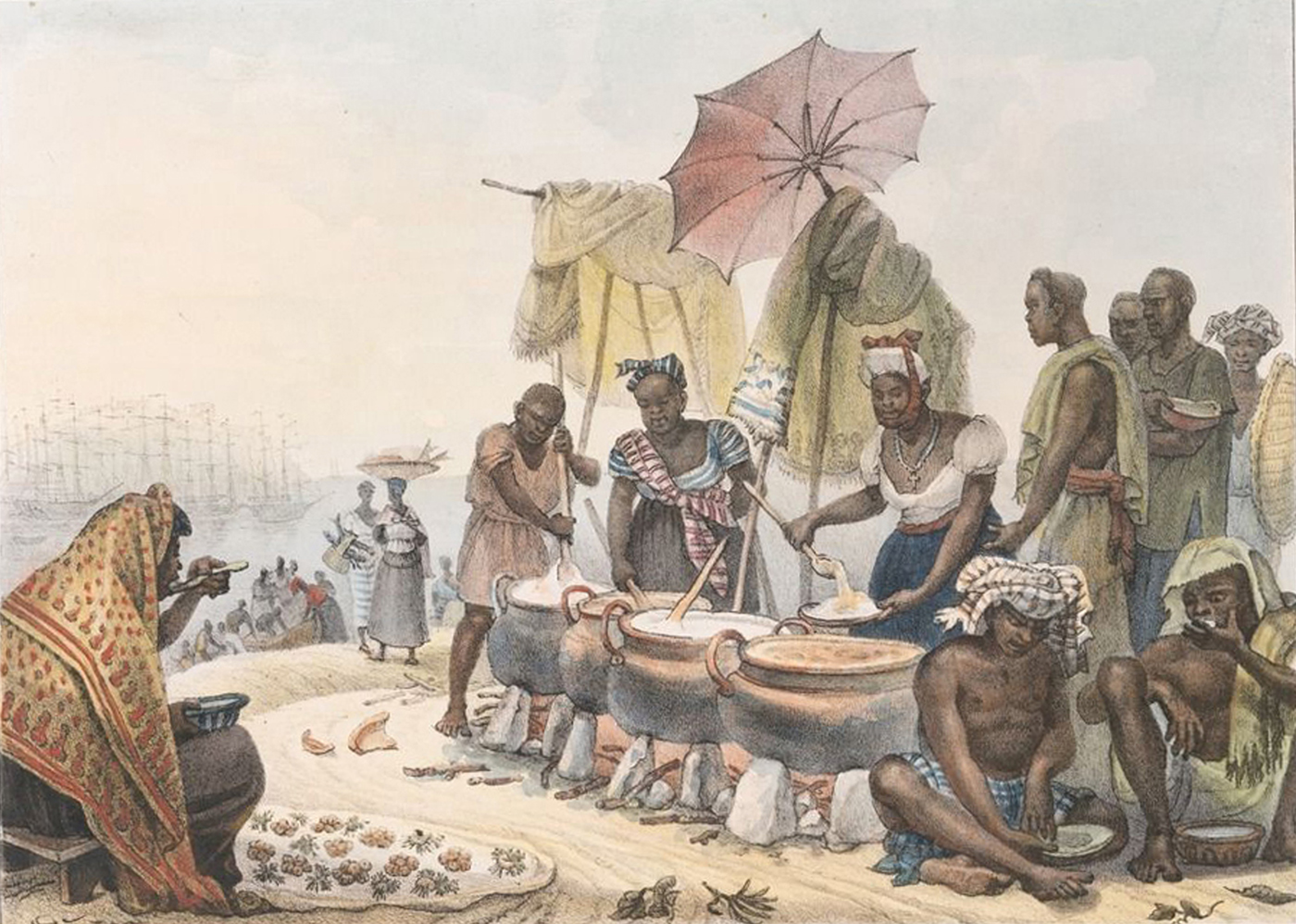

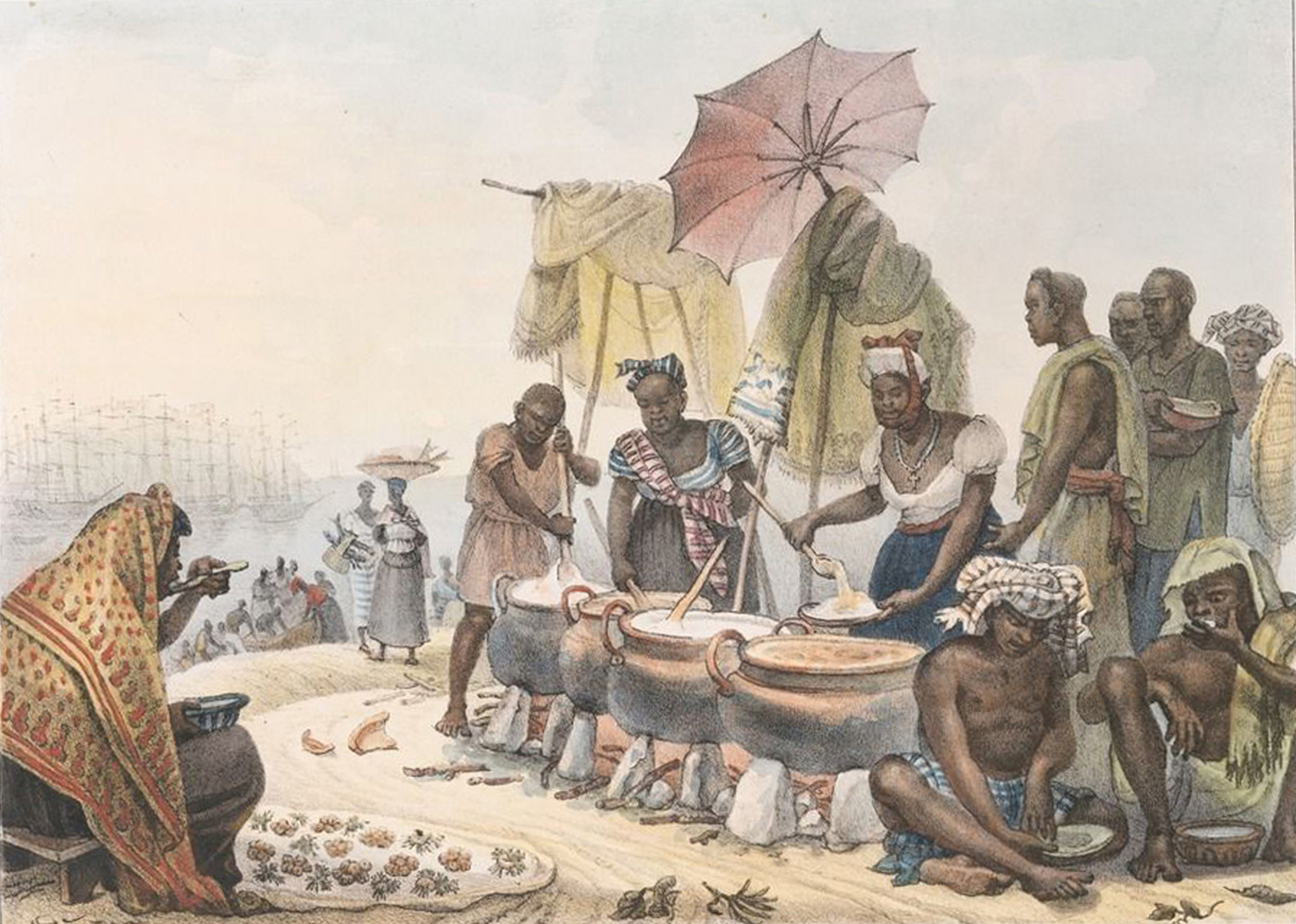

The description given by a Parisian woman who travelled to Rio de Janeiro in the mid-1800s provides a closer view of the everyday business going on near the port. “There stand, under large linen umbrellas, negresses, who serve you, for two cents, […] some angú”.Footnote 18 A painting by Jean-Baptiste Debret (Figure 1) depicts a scene similar to what the Parisian women witnessed. Three vendors at a makeshift stand are preparing angú in cauldrons stabilized by large rocks over an open fire prepared in between them, constantly stirring with large wooden spoons and ladling the angú onto a plate, in order to serve it to the customer.

Figure 1. Jean-Baptiste Debret, Négresses marchandes d'angou [Negress angú vendors].

The sociocultural background and the place of residence were and still are decisive for where and how people take their meals. In the port area the habit of eating out, as a form of providing the highly mobile working class with food during their worktime and beyond, was very common. During the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth century, the city of Rio de Janeiro grew from a small village into the biggest city in South America and one of its most important commercial centres (Figure 2). The population expanded rapidly, nearly doubling in size from 50,000 to 100,000 inhabitants in the period 1808–1838 to 200,000 people in 1850.Footnote 19 The history of Rio de Janeiro in the nineteenth century in many ways resembles the story of other fast-growing cities in different parts of the world.Footnote 20 What makes Rio de Janeiro special is the fact that its growth was largely interlinked with the history of the late transatlantic slave trade. Providing slave voyages to Africa with food was an important part of the infrastructure of the transatlantic slave trade. Food production and provision was one of “the labour-intensive ancillary activities” to the rise of which the slave trade contributed.Footnote 21 Even though Rio de Janeiro had been a slave society since the seventeenth century, fundamental changes were taking place regarding its political and economic importance at the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century. Having been the capital of the Brazilian Empire since 1763, its political importance rose with the transfer of the Portuguese crown and administration as a consequence of the invasion of Portugal by Napoleon's army in 1807. During the 1820s and even more so the 1830s, its economic importance relied on the extremely profitable coffee zones situated in central-south Brazil, and most of all in the Vale do Paraíba.Footnote 22 According to Dale Tomich and Michael Zeuske and their concept of the Second Slavery, central Brazil was one of the “highly productive new zones of slave commodity production” and became the biggest exporter of coffee in order to meet the demand from Europe and North America.Footnote 23 This demand also stimulated the import of new slaves, and Rio de Janeiro functioned as a link between the wider world and the Brazilian hinterland.Footnote 24 Even after the official prohibition of the transatlantic slave trade to Brazil in 1831, slaves were still entering the port up until at least 1850 (and some ships even arrived afterwards).Footnote 25 Of all the slaves imported to Brazil, 2.1 million arrived during the nineteenth century.Footnote 26 Between 1820 and 1860, 803,815 of these captives arrived in the surrounding ports of Rio de Janeiro in the central-south of Brazil.Footnote 27 It was also mainly after the suppression of the transatlantic slave trade in 1850 that the internal slave trade in the Brazilian Empire gained new relevance.Footnote 28 Slaves from the northern and southern provinces were lucratively resold to the central-south provinces, where labourers were more needed than in other parts of Brazil. Brazil's economic development was possible only through the workers performing the necessary “hidden labour” in the port area, such as provisioning and feeding.Footnote 29

Figure 2. Rio de Janeiro in the nineteenth century.

Street vendors were able to do business because their customers, who lived and worked near the harbour, were very often mobile, staying in the city only for a while. For them and for the many other workers on the streets of Rio de Janeiro, eating out was practical or even necessary. The food-selling women were able to offer lower-priced meals especially for working and poor residents, who were often without access to a kitchen. Among the most important customers were seamen who stayed in the city for just a few days and did not always have a fixed address on land, which meant that they lived onboard their ships. After weeks at sea, with its monotonous diet, the crews often spent their wages on food and alcoholic drinks in the port areas. Other important customers were wage-earning (ganhadores) and fugitive slaves, who often shared a room with others, sometimes without access to a kitchen, or even slept on the streets, and in boats at the beach – like the forty-eight-year-old man from São Tomé known to sleep in a canoe at D. Manuel beach.Footnote 30 Another example of housing for slaves was inside the Rio de Janeiro market, where the market slaves could get permission from their masters, who rented the stand, to stay overnight.Footnote 31 As it was forbidden by law to sell pre-prepared dishes inside the market, these slaves had to find their meals elsewhere.Footnote 32

Wage-earning slaves and former slaves were important consumers, and their preferences were observed by vendors.Footnote 33 They had specific expectations regarding what buying food from Quitandeiras meant, which in return induced the Quitandeiras to adjust their behaviour in order to meet these expectations.Footnote 34 The marketing strategies were part of a performance and interaction with the consumer.Footnote 35 To attract the customer's attention, vendors would holler and sing.Footnote 36 Thomas Ewbank, who travelled around Brazil in the late nineteenth century, vividly described his impression of life on the streets of Rio de Janeiro: “The ‘cries’ of London are bagatelles to those of the Brazilian Capital. Slaves of both sexes cry wares through every street. Vegetables, flowers, fruits, edible roots, fowl, eggs, and every rural product; cakes, pies, rusks, doces, confectionery, ‘heavenly bacon,’ etc., pass your windows continually.”Footnote 37 Through such immensely crowded streets the Quitandeiras walked; they were described as elegant, with a basket or a tray, and wearing characteristic clothing – such as a coloured dress, a turban, and a pano da costa over the shoulder.Footnote 38 The atmosphere surrounding the act of eating was also important for the overall experience, since dining is a multi-layered experience appealing to all senses.Footnote 39

Toussaint-Samson and other travellers described angú as the slaves’ staple food.Footnote 40 The labour-intensive dish angú, in other regions of the Atlantic world called fufu, is made by boiling either manioc or maize in water and then mashing it while stirring continuously until it is sticky. Its consistency is similar to, but thicker than, mashed potatoes. It is served with various ingredients.Footnote 41 Angú is still advertised as the ideal food for giving workers energy in order to get through their day without hunger.Footnote 42 It was typically consumed in West Africa. Since angú was normally eaten without cutlery, as can be seen on the painting by Debret (Figure 1), the food had to be prepared in such a way that it did not stick to the fingers. The preparation of the dish varied considerably depending on the availability of ingredients.Footnote 43 Manioc or maize were the core ingredients in preparing angú, but to achieve a tasty meal a starchy sauce with the aforementioned ingredients would be served as well.Footnote 44 The preparation of the sauce, using palm oil (azeite de dendê) from West Africa and spices, was central to the specific taste of the dish. Toussaint-Samson notes that “the negroes, who are most dainty, even season everything with a sort of fat they call azeite de dindin”.Footnote 45 Daily newspapers in Rio de Janeiro frequently advertised palm oil to angú sellers.Footnote 46 It was already being produced in Brazil, but it was also common to import it from West Africa.Footnote 47 Intermediaries, travellers, and ships’ crews frequently crossed the Atlantic and through their access to various markets were able to engage in trade in the commodities requested.Footnote 48 Food could function as a strong “agent of memory”, which is very important for diasporic groups in order to feel connected with their homeland.Footnote 49 As Pierre Bourdieu pointed out, taste in food has an undeniably strong influence on our identities. “It is probably in tastes in food that one would find the strongest and most indelible mark of infant learning, the lessons which longest withstand the distancing or collapse of the native world and most durably maintain nostalgia for it.”Footnote 50 Therefore, it was not surprising that the influx of thousands of forcibly immigrated people changed consumption habits in the cities.

In her description, Toussaint-Samson also specifies the customers, saying that the habit of eating out is above all a consumption behaviour maintained by those who are members of the lower classes: “[…] a negro's repast, and even that of the white people of the inferior classes”.Footnote 51 As shown in Figure 3, a scene from the Largo do Paço (palace square), where seamen and officers are using their afternoon breaks to buy sweets and drinks from the Quitandeiras, street food was consumed not only by the lower classes. Angú da Quitandeira could be found not only on the streets but also on menus – “O bello e succulente almoço” – at a ball at the Casino Fluminense in 1886 and as part of a theatre piece alluding to the fact that the dish was very prominent.Footnote 52 In the play, social class differences in food consumption were used to produce an ironic effect.Footnote 53 In the Portuguese version the play was entitled O angú da quitandeira, which was clearly meant as an allusion to the exotic origin of the dish. In Brazil, however, angú da Quitandeira was far from extraordinary and, therefore, the play was called O angú do barão. The plot can be summarized as follows: An old baron, who is married to a beautiful young woman (a dualism), invites a colleague of his to his house for dinner. Instead of offering his guest a dish that would correspond to his social rank, he serves him angú (another dualism). Due to the palm oil, which is one of the typical ingredients of angú, the dish is apparently highly seasoned. Therefore, the baron drinks a considerable amount of alcohol, which inevitably makes him drunk. His guest, however, is more interested in his host's wife than in the taste of the meal. While the baron's body temperature is rising due to the spicy angú, his guest also feels the heat of his body because of the presence of the young woman, who is described as a dish too. Since the baron, who is clearly drunk, soon retires to his chambers his colleague is able to fulfil his emotional and amorous desire, although the details are left to the spectator's imagination.Footnote 54

Figure 3. Jean-Baptiste Debret, Les rafraîchissements de l'après-dîner sur la place du palais. [After-dinner refreshments on the palace square].

For the middle and upper classes, eating at home was the most common way of taking their meals. Most well-off households had servants who prepared dishes for them.Footnote 55 In these social classes, eating at home – though frequently in the company of their kin, colleagues, or acquaintances – was a central element of domestic sociability.Footnote 56 However, the ingredients for these meals had to be bought at the local food markets or from vendors selling products door-to-door, in ways that effectively connected them with the street-food sector.

To understand the street-food sector, it is important to look at the Quitandeiras’ networks and to explain the local underground food distribution. The majority of foodstuffs arrived in the city from other parts of the province and other parts of Brazil.Footnote 57 A number of free blacks and slaves were part of this trade. Some worked on boats, others on small canoes, like João, a canoe man from Mozambique, who used to transport goods between Gamboa and Prainha.Footnote 58 Sometimes slaves would steal canoes in order to start a business.Footnote 59 In the port area, canoe men and street vendors came together, as in the case of a thirty-to-forty-year-old Quitandeira, who likely escaped with one of her seamen friends.Footnote 60 In another case, the grass-selling slave Antonio, well-known at D. Manuel beach, escaped. Sometimes, he could be seen with a little canoe near the food stall kept by his mother, a Quitandeira.Footnote 61 Sources that mention individual cases like these allow a glimpse of underground networks between street-food vendors and workers who supplied the city with food. The port area was a natural place to sell fish and shellfish, and for this reason slaves and free(d) men like the famous “pica peixe” went fishing in their canoes.Footnote 62 They could sell the fish they caught to vendors (at the market or outside of it). Through the implementation of high hygienic standards inside the market, any fish not sold the same day they were caught had to be thrown away.Footnote 63 It is conceivable that some of these leftovers could have been sold to ambulant vendors at a lower cost. Home-produced goods such as alcoholic drinks, jams, cakes and sweets, crops and fruits planted by slaves in small gardens, and chickens and other small farm animals raised on the same land were also sold on the streets. Fixed commercial establishments had their own vendors who sold the products in the streets.Footnote 64 João, for instance, a slave who escaped in 1824, had stolen from his master before and was selling the items on the streets.Footnote 65 A similar case was that of Cesario Coelho Paredes, who was convicted in 1855 for selling eleven stolen chickens and a rooster to a Quitandeira.Footnote 66 The atmosphere of the chaotic city with mule trains and other animal transports arriving from distant farms and women carrying large baskets of chickens on their heads made the city susceptible to missing animals, which could be taken by others.Footnote 67

In addition to street-food vendors, over 1,000 taverns, small establishments where labourers could eat and drink, and over 700 corner stores could be found in the city around 1850.Footnote 68 Members of the economic and social elite consumed items imported from Europe, which were increasingly advertised in the daily newspapers.Footnote 69 French cuisine became the standard in the nineteenth century, and for this reason French chefs and the French restaurant concept were imported to Brazil after the middle of the century.Footnote 70 Most high-end restaurants would even announce in French “huitres fraiches, potage aux huitres frites, branlade de morue, et tout ce que l'on peut désirer dans un hôtel”.Footnote 71 Portuguese and Italian restaurants also opened during this time, where it was commonly male chefs, recently emigrated from France, Portugal, and Italy, who ran the kitchen.Footnote 72 In comparison to street vendors and taverns that offered inexpensive foods and drinks, haute cuisine was not strongly represented in urban areas in the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 73

URBAN SPACE

Contemporary visitors to Rio de Janeiro left behind a narrative of the chaotic street commerce and narrow and highly frequented streets.Footnote 74 Although the provisioning of the city and its inhabitants relied, to a large degree, on a high number of food-selling women and the work they did, survival in the urban milieu was difficult. The study of contemporary newspapers sheds light on the everyday problems and struggles of the street sellers.

The authorities tried to regulate the city space and the places where vendors were allowed to sell foodstuffs because such spaces were intended as representative public spaces of the growing modern city. The food market was one of these projects – coined by a contemporary journalist as a place “capable of challenging the jealousy of Europe's important cities”.Footnote 75 For this reason, enslaved purchasers were ordered to spend only a minimum of time at the market and to leave as quickly as possible.Footnote 76

As in the case of Emília Soares, even vendors at the top of the food-selling hierarchy were not immune to the profit-maximizing interests of private investors or the state, both of which monopolized selling areas with the aim of increasing rents to make more money off the Quitandeiras’ labour, hoping workers would accept the new conditions because there were no alternatives. The stallholders at the market formed a union and tried to combat the unequal power relationship by making their protest public in the local Rio newspapers.Footnote 77

Hiring a stand on the market required more capital than most Quitandeiras could afford. Therefore, many of them sold their goods in other places, where they were the subject of regular complaints by city officials and/or citizens – oftentimes published in local newspapers.

The expulsion of food-selling women from certain parts of the city was justified by reference to those complaints, which related to noise, the accumulation of garbage and leftover foodstuffs from the vending sites, as well as criminal and immoral acts, such as prostitution.Footnote 78 These complaints show a typical perception of street-food vendors and poor people in general as a nuisance and a threat. Even today, such statements are used as justification for the treatment of people doing business on the streets.Footnote 79

In 1863, for example, an anonymous citizen complained about a Quitandeira who worked at the Largo do Rocio in front of a building and sought to have her banned from the site because her numerous customers disturbed the neighbourhood regularly between five and ten o'clock in the evening by blocking both the front door and the sidewalk.Footnote 80 The complaint shows that the vending stalls were also places where people met, shared news, and grouped together. The vendors were deeply enmeshed in the everyday occurrences on the streets of their neighbourhood. Slaves who managed to escape had often begun building their networks before they escaped. This was a common occurrence on the streets, for example, when some of them visited Quitandeiras. Apparently, masters knew about their contacts, friendships, and visits, as in the case of the slave Benedicto, who had been in contact with the community of Mina slaves for some time before his escape.Footnote 81 Against the background of the Age of the Atlantic Revolutions and several slave rebellions such as the Malê revolt in Bahia in 1835, meetings of slaves and former slaves at places in the city could cause fear among the city's authorities.Footnote 82

Another much-cited complaint from 1776 shows that the struggle for urban space had a long history in Rio de Janeiro. In this case, the complaint nearly caused the expulsion of the Quitandeiras from their selling point in front of the town hall.Footnote 83 The presiding judge of the town council (a Portuguese judge directly appointed by the Portuguese crown) had decreed the closing of the Quitandeiras’ stands due to the constant noise the selling produced. Some Quitandeiras appealed to the town council attorney against their expulsion from their selling point, since they had been providing the inhabitants of the place with foodstuffs for years and – in contrast to other vendors – had an official licence. Their complaint convinced the town council attorney to support their claim to stay; he agreed to represent them and, in the end, was responsible for repealing the new law. He drew attention to the fact that the numerous illegal vendors probably would not be banished by a decree. The law would have ended up punishing the wrong vendors without solving the original problem. This incident sheds light not only on street vendors’ struggles, but also on the chances that their voices would be heard, if they united. For vendors, to group together offered them protection. As a result of the street vendors’ mobility and knowledge of narrow streets and alleys, as well as of hiding places, city authorities found it difficult to monitor their enterprises. They were also unable to stop the Quitandeiras from engaging in other commercial activities on the side, which in some cases were more profitable than the act of selling food. An article in the Diário do Rio de Janeiro mentions that a Quitandeira who worked as a fortune teller in the Rua da Carioca and earned 5,000 réis per customer continued with this work although she had been asked to end it.Footnote 84 The street-selling women were a visible part of society, but certain activities had to happen out of sight of the authorities. Clandestine meetings happened in taverns, specialized in providing drinks, or in the casas de angú, “small establishments where slaves and freed persons converged to eat”.Footnote 85 Some of these rooms also functioned as hiding places. The authorities recognized their strength, considered them a threat to their power, and attempted to control them by invading their establishments.Footnote 86 They became important places of social interaction and also a place to practice African-Brazilian religions, which stressed female knowledge of the rituals of cooking and healing.Footnote 87 In these religions, preparing ritual dishes fed the different eating preferences of the spirits in order for them to release their energy into the world, and it was traditionally a space for women.Footnote 88 Members of the community would meet up at night to share meals, celebrate religious events, make music, gamble, or have their fortune told.Footnote 89

Numerous newspaper articles contain reports of robbery, poverty, or violence. The bodies of many women showed marks of slavery and violence, like the one of “a black woman […], who had a scar of a stab wound on her face and sold angú at the Praia do Peixe”.Footnote 90

Furthermore, many articles focus on acts of violence among poor people.Footnote 91 A certain Luiz Gonçalves was arrested because he had stolen money from a Quitandeira who was selling fruits. In another case, two people attempted to kidnap the son of Quiteria, a Quitandeira at the Prainha, and sell him into slavery even though he was a free person. Rodrigues, a forty-two-year-old coach driver from the province of Maranhão and a fifty-year-old Quitandeira, Maria Nacisado Espirito Santo, were sentenced to ten and eight years respectively in prison because the first raped a thirteen-year-old girl, Leopoldina Carolina, the granddaughter of Maria, who sold him Leopoldina's virginity.Footnote 92 Although sexual abuse and violence were part of the everyday life of enslaved and freed women in the Atlantic world, the newspaper article about this specific case highlighted it as being from the lowest and most immoral parts of society.Footnote 93 In many instances, the alleged moral profligacy of these people served as an explanation for the violence among them, a global phenomenon. The poor were described in a way that contributed to an intense fear of these parts of the society and led to their further dissociation.Footnote 94

Some dangers on the street are connected to their being women. Women could benefit from relationships with wealthy men who supported them financially.Footnote 95 Many of these relationships were formed through coercion, and numerous enslaved women resorted to prostitution to earn money for their master. Freed women prostituted themselves as a result of poverty and lack of other opportunities. In small-scale disputes, women developed strategies to defend themselves against some attacks. Camille de Meirelles, for instance, accused a twenty-year-old Quitandeira Mina, a slave woman owned by João de Oliveira Lima, of hitting him across the face as an insult. He claimed that the event took place in a tavern. The court found her not guilty, after she was able to prove that her accuser had made up the story after she had rejected his advances.Footnote 96 The reaction of the accuser is hardly surprising when put against a backdrop of a society that privileged white men. With regard to the European colonies and particularly to the plantations in nineteenth-century America, Jürgen Martschukat and Olaf Stieglitz have adapted Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari's concept of the “desire machine” (machine désirante), where they emphasize that

the colonial expansion, as machine of conquest, subjugation, and government, was also a “machine désirante”, a desire machine […]. The colonies and especially the slave plantations in the Americas of the nineteenth century appeared as places in which everything was possible for the colonizers and specifically for the masters. Sex was an instrument and a technique of violent subjugation of the “other”.Footnote 97

The personal cases described by the newspaper illuminate the social problems in a slave society where manumission was not unusual but the marginalized status was very difficult to escape.Footnote 98

GENDER

Several examples clearly illustrate that slaves preferred to work on the streets, and even tried to convince their masters to send them there to work. For example, a reward announcement for the capture of the runaway slave Dionizia, published in the Diário do Rio de Janeiro in 1825, shows that this slave woman begged her master to let her work as a Quitandeira on the streets. Dionizia's master refused her plea, whereupon she fled the confines of the household and tried to survive on her own.Footnote 99 Working in the food sector allowed women to combine domestic with productive labour in a job that offered them and their families a certain food security. In contemporary newspapers, slaveholders advertised female slaves mostly as general domestics with the addition of being very skilled at selling goods.Footnote 100 Female slaves were employed for general household duties, but these could easily be combined with occasional, or part-time, street vending.Footnote 101 For families or people with only one or a few slaves, it could be economical to buy one slave to keep the house clean and additionally make some money on the streets.

The work of men was more valued in Brazil. As a consequence, female slaves were easier to acquire and especially interesting for less wealthy groups. Investments in slaves indicated socio-economic mobility and were the easiest form of wealth to acquire.Footnote 102 In the 1840s, Quitandeiras were worth on average 300,000 réis according to the Jornal do Commercio. Comparing the cost with the potential income generated in the vending sector, it is obvious that purchasing a healthy female slave could be extremely profitable. In most newspaper announcements, being characterized as “Mina” was a positive description used to drive the price up and quicken the sale. Only in very few cases were Mina slaves not preferred but seen as rebellious.Footnote 103 Foreign visitors who came to the city in the nineteenth century highlighted the Mina's proficiency in trade and distinguished the food-vending women from the ordinary mass of the slave population.Footnote 104 Their reputation as good vendors was not only earned on the basis of skills acquired in their regions of origin in Africa, it was part of a discourse about the Mina's superiority known throughout many parts of the Atlantic world.Footnote 105 Food preparation, cooking, and selling were traditionally female enterprises in West and Central Africa.Footnote 106 In Luanda, Quitandeiras also sold their products in ways similar to those adopted by the women in Rio de Janeiro, but they did not enjoy the same reputation as the Mina women.Footnote 107 Certain advertisements boasted that the slaves were capable of paying their master up to 640 réis per day.Footnote 108 According to the paper, the average payment to the owner was 496 réis a day, i.e. around 150,000 réis a year.Footnote 109 Based on this calculation it was possible for a Quitandeira to earn her selling price within two years. It can therefore be assumed that owners bought women to use them as Quitandeiras because male slaves would have been more expensive, and not necessarily more successful as street vendors, while women could also carry out other, even more profitable tasks. The most successful vendors would have started their businesses as slaves, and self-employed people earned enough money to buy their freedom, hire a stand at the market, and eventually invest in slaves.Footnote 110 Quitandeiras also occasionally advertised slaves in local newspapers. A Mina woman who sold angú across the Santo Antonio Street invested in slaves and resold a slave woman called Thereza to another owner.Footnote 111

These women created female spaces throughout the city, integrated their slaves into their communities, and were sometimes even regarded as part of the family (fictive kinship).Footnote 112 As Farias has pointed out in her study on Mina market women in Rio de Janeiro, this form of kinship could lead to the emergence of strong networks between women and the passing on of wealth from woman to woman (Casamento de mulheres).Footnote 113 However, it would be wrong to assume that these women always acted in solidarity with each other. On the contrary, one woman tried to sell her slave through a newspaper announcement, adding that the slave woman was behaving in a rebellious way and would not follow the orders of a “black” woman.Footnote 114 Sometimes, even poor “white” women could be part of the female spaces formed by the street-vending women. In the Jornal do Commercio an old white woman was advertised as a domestic servant. At the time, she was living in one of the Quitandeira’s houses, which illustrates contacts between white women and Quitandeiras that go beyond the “normal” hierarchy with white women at the top.Footnote 115

Through its interconnection as a port city, Rio de Janeiro was strongly linked with other parts of the world. A European reader interested in contemporary literature might have heard of the Quitandeira even though he or she had never been to Brazil. Because street vendors were typical figures of the nineteenth-century city landscape, they also appeared in these forms of entertainment. Natasha Korda shows that in early modern London both forms of entertainment, the performance of women selling on the streets and professional theatre plays, competed with each other.Footnote 116 A great number – but not all – of these novels and plays could trace their origins to France, more specifically to Paris, and were published in Brazilian newspapers or played at the theatres in Rio de Janeiro.Footnote 117 The highly successful social novel Les mystères de Paris, written by Eugène Sue and originally published in the French newspaper Le Journal des débats between June 1842 and October 1843, was a description of nineteenth-century Paris, showing the social problems and the living and working conditions of the poor parts of the city's population.Footnote 118 Female workers, such as prostitutes and street vendors, are also featured in this novel. It was translated into Portuguese and published in the Jornal do Commercio in 1844. The novel was highly successful in Rio, attracting the interest of Brazilian readers.Footnote 119 Despite male vendors also existing, the plays and stories gave female characters a prominent role and a much higher degree of fame. The popularity of street-life representation in plays, with their diverse characters, ensured that the character of the Quitandeira appeared in theatre pieces like The Boy and the Quitandeira and in serialized novels published in the newspaper written by Brazilian authors.Footnote 120 The fictitious figure of the Quitandeira was created through these novels and plays but also through travel accounts, poems, and songs written in this period.

In Europe, the demand for travel accounts with stories about far-off lands and exotic characters was high, and, because of this, published accounts had a large number of readers. Contemporary descriptions by foreign visitors highlighted the beauty and seductiveness of the slave women. The announcements in contemporary newspapers confirm this view. In some of these announcements the beauty of the slave women is highlighted and gives an idea of “the quotidian monstrosity of the desire to which she was subjected”.Footnote 121 This exoticism is reminiscent of the image of the women of colour in other parts of the Atlantic world in the nineteenth century.Footnote 122

Eduard Duller, a contemporary Austro-German author, became so familiar with the Quitandeira through travel accounts that in 1834 he wrote a short story, “The Quitandeira from Rio Janeiro”, without ever having visited Brazil.Footnote 123 The main character, a Quitandeira, is defined by the love she has for a certain slave.Footnote 124 This love can never be, because the slave has already been promised to someone else in his home country. During his attempt to escape slavery and return to Africa, he trusts his former king, the father of his fiancée, to help him and ignores the advice of the Quitandeira not to trust the king. After the Quitandeira recognizes that the man she loves cannot be convinced of the king's false intentions, she accepts the advances of a rich white man. In this passage from the story, the power white men hold over the Quitandeira is clearly evident.Footnote 125 In the end, she saves the slave from slavery and drowns herself in the ocean. In the story, bourgeois virtues such as self-sacrifice, fidelity, and chastity are discussed.Footnote 126 The storyline is similar to that of the widely read novel The Last Days of Pompeii, also published in 1834 by Edward Bulwer-Lytton.Footnote 127 A female enslaved flower vendor plays a key role in the story. Even though she is blind, she leads her would-be lover and his lover through the streets of the city to the harbour where they escape before the volcano erupts, while thousands are killed. Because her would-be lover never loved her, Nydia the flower girl drowns herself just like the Quitandeira. This story presents Nydia not as a passive slave, but as a capable actor who, in spite of her blindness, knows the streets of the city better than anyone else. A sculpture of Nydia was made in 1859 and became very popular during the nineteenth century.Footnote 128 Since it is highly probable that Duller knew Bulwer-Lytton's novel, it does not seem far-fetched to assume that he constructed the character of the Quitandeira in allusion to Nydia and presents the Brazilian woman not as a helpless slave but as a capable actor.

Furthermore, during the World Exhibition in Vienna in 1857 the Brazilian commission decided to integrate the picture Fruchtverkäuferin in Rio de Janeiro into their exhibition (Figure 4).Footnote 129 The picture was taken by a well-known German photographer, Alberto Henschel, in his studio in Rio de Janeiro. In the picture, a saleswoman, dressed in a clean white dress and a turban, smokes a pipe while she is sitting in front of her stall, which is decorated with exotic fruits. The background is that of a tropical landscape. Altogether, fruits, dress, stall, and background were designed to evoke “feelings of exotic authenticity and mysterious foreignness” among the visitors to the World Exhibition.Footnote 130 In a companion volume to the World Exhibition, it was stated that, as a sign of progress, slavery in Brazil would soon be gone without rebellions or damage to the private property of the slave owners since the “release of slaves was common”, which “confirmed the mild mind and the philanthropy of the Brazilian people”.Footnote 131 As highly visible workers, the Quitandeiras would be a clear sign of this progress for visitors. Of course, her clean and perfect dress, as well as the absence of visual signs of violence or hunger, romanticized her life and work on the streets.Footnote 132

Figure 4. Alberto Henschel, Fruchtverkäuferin in Rio de Janeiro [Fruit seller in Rio de Janeiro], c.1869. Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde, Leipzig (Germany).

Beginning in the 1880s, the women who were actually working as Quitandeiras on the streets were increasingly driven off the streets of Rio de Janeiro.Footnote 133 Paradoxically, the end of slavery also meant the end of the relatively autonomous branch of the economy in which these women had previously been able to work and live.

The Quitandeiras displayed a high degree of visibility during a period in which female vendors attained a public profile not only in Brazil but also abroad. This connects them to other poor working women in the urban milieus of nineteenth-century cities. As we can see from the serialized novels and theatre plays that appeared in Paris, London, Rio de Janeiro, and elsewhere, the figure of the female street vendor had entered popular culture. However ambivalent in their portrayal, and despite the sexual and exotic connotations that are frequent features of these stories, some of them also give their female characters a considerable degree of agency and power.

CONCLUSION

Research on street food has increased dramatically in recent years, with several case studies from different historical periods and cities around the world. These studies highlight street food as a typical source of income for women in urban areas. In the port city of Rio de Janeiro, many women of colour worked in a wide range of activities linked to the food sector in which free and different forms of unfree labour co-existed. These women created a niche of economic opportunity in a place dominated by men. The local food markets were economically significant and inextricably linked to Rio de Janeiro's role in the late transatlantic slave trade. Despite their economic importance, they aided the development of urban cultures in Rio de Janeiro, which have to be seen in an Atlantic context. Street food not only helped to preserve the eating habits of the diaspora, it also gave rise to a consumer culture for the working class. Despite their different statuses, workers met up at taverns, casas de angú, or at meeting points on the streets to socialize.

Street vendors worked under conditions that were always hard, often dangerous, and financially precarious. To walk through the streets of the city for the whole day carrying a tray with several bottles of liquor, a large basket of fruits, and live chickens, for instance, was extremely exhausting; such work reflected absolute necessity rather than choice. The vendors engaged in different forms of protest and sometimes supported each other in order to find ways out of their marginalized status. Some of these struggles received public attention. Others were part of the everyday activities of the women and happened in the shadows of the port city. Despite all their efforts, the city's authorities were unable to prevent the selling of food on the street, since their intentions were undermined at a local level. The co-existence of different labour forms produced a very flexible labour market in Rio de Janeiro and resembles the “width of the forms of labour and exploitation in capitalism” in general.Footnote 134 Rather than banding together in a mutual struggle against these forces, women working in the food sector also fought against one another, in a competition for survival. Some women were themselves slaveholders.Footnote 135

The Quitandeiras were highly visible and therefore defined the widespread image of the city. Their reputation extended to distant parts of the world due to the fact that Rio de Janeiro was a globally connected port city. This article has demonstrated that the Quitandeiras can be seen as part of a larger heterogeneous group of street working women who, in many parts of the world, gained visibility and recognition on the streets of growing cities and in popular culture in the first half of the nineteenth century.