INTRODUCTION

Today Hokkaido is one of Japan’s four main islands. It was called Ezochi until 1869, when it officially became Japanese territory and was renamed Hokkaido. Ezochi means the land of “the Ezo”, or “the barbarian”, which referred to the indigenous people, now called the Ainu. While Ezochi referred to Hokkaido in general, the term broadly included what are now known as Sakhalin, Hokkaido, and the Kuril. In this article, I have therefore used the term “Ezo Islands” to refer to the latter. While the Ezo Islands were not officially part of Japan in the early modern period (1603–1867), the Japanese believed that they were under Japanese control regardless of their actual relations with the Ainu and whether the Ainu recognized their claim. The ambiguous status of the Ezo Islands came to an end during border negotiations with Russia, which began in 1853. Based on the above view, Japan asserted territorial rights over all the Ezo Islands. However, Japan then lost Sakhalin under the Treaty of St Petersburg in 1875, when Hokkaido and the Kuril Islands became Japanese territory.

Many scholars of modern Japanese history have regarded Hokkaido as a frontier within the Japanese national border. Meanwhile, the status of Hokkaido after 1869 has rarely been disputed, for, as Mason points out, “Hokkaido’s status as a colony is commonly denied, implicitly or explicitly […] in colonial and postcolonial research”.Footnote 1 However, in his lectures on colonial studies at Tokyo Imperial University given in the mid-1910s, Inazo Nitobe treated Hokkaido as a colony together with other Japanese colonies such as Taiwan (1895–1945), Southern Sakhalin (1905–1945), and Korea (1910–1945). More recently, Hiroyuki Shiode has argued that Hokkaido had been a dependency until 1903, when it was officially incorporated into Naichi, or the mainland.Footnote 2 The Japanese mainland consists of the three islands of Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu, which have been Japanese territory since the beginning of the early modern period.

Even many of the scholars studying Hokkaido have failed to remain free of national ideology, and there was a contradiction between what the Japanese government did and what it said. The focus of this article is Hokkaido’s role as a penal colony. I shall therefore consider here the transition in Hokkaido’s status within the Japanese process of building first a nation state, and then an empire. The first treaty with Russia was concluded in 1855 and drew the Japanese-Russian border between the islands of Iturup and Urup in the Kuril. Subsequently, both the Tokugawa Shogunate and its successor Meiji government (1868 onwards) considered the introduction of penal transportation as a means to facilitate the rapid settlement of Japanese people on Ezochi. Both regimes were aware that one of the strategies of Russia, as much as of Western countries, was to expand by means of colonization, and that awareness, in turn, implies that, at that time, Hokkaido was not thought of as part of the Japanese mainland.

Although it is well known that penal transportation and convict labour were implemented in Hokkaido in the late nineteenth century, it has always been regarded by historians as being less important than other forms of migration. Penal transportation has traditionally been seen as a temporary labour system used in the very early stages of the Japanese project to develop HokkaidoFootnote 3 and as a measure to deal with the shortage of prison space resulting from the aftermath of anti-government movements and revolts from the 1870s to the 1880s.Footnote 4 Certain scholars mention, too, its broader context, which required revision of unequal treaties, for which it was necessary to establish a Western-style penal system.Footnote 5 The Japanese were also anxious about further Russian incursion southward,Footnote 6 and scholars have tended simply to conflate all those background considerations so that the relationships among various demands have not been well described. Moreover, previous researchers have tended to dwell on how penal transportation was introduced, rather neglecting the abolition process, which has consequently not been well studied. This article serves to clarify the relationship between the Japanese penal system and its empire building by describing Hokkaido’s place in the Japanese criminal justice system, from the introduction to the abolition of penal transportation.

During the late nineteenth century, when the Japanese began to build a nation state and an empire along Western lines, within the European countries that had provided the colonial template attitudes to penal transportation were divided broadly in line with colonial policies. France and Portugal continued penal transportation, but Britain discontinued it and, for their part, Germany never introduced it,Footnote 7 for incarceration was regarded as a more civilized and suitable punishment than transportation.Footnote 8 Meanwhile, Japan’s choice of mode of punishment mirrored contemporary Western debate as its nation building involved drastic reform of social and judicial systems in which the decision was made to deal with both domestic and diplomatic matters. In terms of its penal system, Japan first followed the French model in implementing penal transportation to Hokkaido and then, in the early 1890s, decided to follow the German model and so abolished it. However, Hokkaido continued to be a place of punishment for long-term prisoners. In describing how events unfolded, this article will show the fluidity between transportation and incarceration.

The history of Hokkaido’s shift from having the status of a colony to becoming part of the Japanese mainland set a precedent for subsequent Japanese colonial rule. Naichi enchō shugi, or “extending homeland ideology”, is the term usually applied to Japanese policy in colonial Taiwan and Korea, and, in general, Japanese colonies were regarded as places that, once fully assimilated, would eventually be incorporated into mainland Japan. The term first appeared sometime after 1919, applied to colonial policy relating to Taiwan, but the case of Hokkaido can be seen as the first true instance of it, indicating continuity between nation-state building and empire building in Japan. This article will show, too, how the penal system of the mainland affected that of colonial Taiwan and Korea in the sense of “extending homeland ideology”.

PENAL TRANSPORTATION TO HOKKAIDO

It was in the late eighteenth century that Japan first faced foreign expansion southwards into northeast Asia when Russian territorial growth began to encroach on the Ezo Islands. Although, at that time, the islands were not formally Japanese territory, many officials of the Tokugawa Shogunate and contemporary intellectuals felt strongly that the islands were nevertheless Japanese territory. The Ainu and the Matsumae-han, the northernmost domain of early modern Japan, had long enjoyed trade relations, with Japanese merchants gaining permission from Matsumae to establish fishing grounds around Ezochi and the southern coast of Sakhalin, employing the Ainu as labour. Then, from 1799 to 1821, the shogunate took direct control of Ezochi for reasons of national defence against Russia. Garrison forces were dispatched and the Ainu were ordered to cooperate in securing the islands against the Russians.Footnote 9 However, the Japanese government did not actually enforce annexation of the Ezo Islands and the shogunate abandoned its migration policy as soon as direct control began. As a result, the policy to assimilate the Ainu was also abandoned.Footnote 10 Tributary trade, called omemie, was carried on between the Ainu chiefs and shogunate officials (or Matsumae-han officials) and that, at least for the Japanese, implied that the Ainu were subject to Japanese authority. That, then, was the basis for Japanese rule over the Ezo Islands, as far as the Japanese were concerned.

On the other hand, until the early nineteenth century, many Japanese intellectuals, among them Toshiaki Honda and Nobuhiro Satō, advocated a national defence policy. They made reference to Western imperialism and asserted that Japanese migration, including transportation of convicts to the Ezo Islands, was necessary to Japan’s defence.Footnote 11 Indeed, they also called for further expansion into Kamchatka and North AmericaFootnote 12 and, still in the name of national defence, promoted the idea that Japan should occupy territory far beyond its actual borders. That, however, did not become government policy.

By the late nineteenth century, the Ezo Islands had been divided between Japan and Russia. In 1855, a border was drawn between Iturup and Urup, part of the Kuril Islands, but negotiations over Sakhalin took another twenty years to resolve. Until then, Sakhalin was left open to settlement by both nations, and the Japanese and Russians competed to settle their own people on the island with the intention of strengthening their claims to territorial rights. In the end, Russia prevailed, and in 1875 Japan and Russia concluded the Treaty of St Petersburg under which the whole island of Sakhalin became Russian territory.Footnote 13

It was through those processes of division and formalization that Japan gained Hokkaido and the Kuril Islands as new territory, but lost Sakhalin, part of the empire it had imagined for itself. In its first experience of international territorial dispute, the Japanese government therefore recognized the significance of migration as a way to secure territory against Western imperialism. The Japanese had enjoyed trade relations with the indigenous people of Sakhalin long before the Russians came, but because they failed effectively to settle a Japanese population on the island they lost any territorial rights to it.

Hokkaido became the island of Japan’s northern border. Having learned from experience, as soon as it assumed power, the Meiji government not only recruited free migrants to go to Hokkaido, but sent vagrants there too, and finally sought to introduce transportation of convicts. In 1868, the Meiji government designated what was then still known as Ezochi as the sole destination for transportationFootnote 14 and began to compile a penal code. From the early stages of the project, certain government officials were interested in the French model, so in 1872 the Japanese Ministry of Justice dispatched officials to Europe, specifically France, to investigate legal systems there. During that visit, the Japanese delegation succeeded in recruiting the French jurist Gustave Emile Boissonade as an adviser. In 1880, drafted by Boissonade, a new penal code was promulgated under which five categories of punishment for felony were prescribed: the death penalty (shikei), penal servitude (tokei), transportation (rukei), imprisonment with hard labour (chōeki), and imprisonment without hard labour (kingoku). Those sentenced to penal servitude or transportation were to be transported to an island for life or a finite term of from twelve to fifteen years. Although the penal code did not indicate any specific island as the destination, the prison code that was revised in 1881 stated that convicts who were sentenced to penal servitude or transportation were to be confined in shūchikan prisons on Hokkaido. Those sentenced to imprisonment with or without hard labour were to serve terms of six to eleven years in mainland prisons.

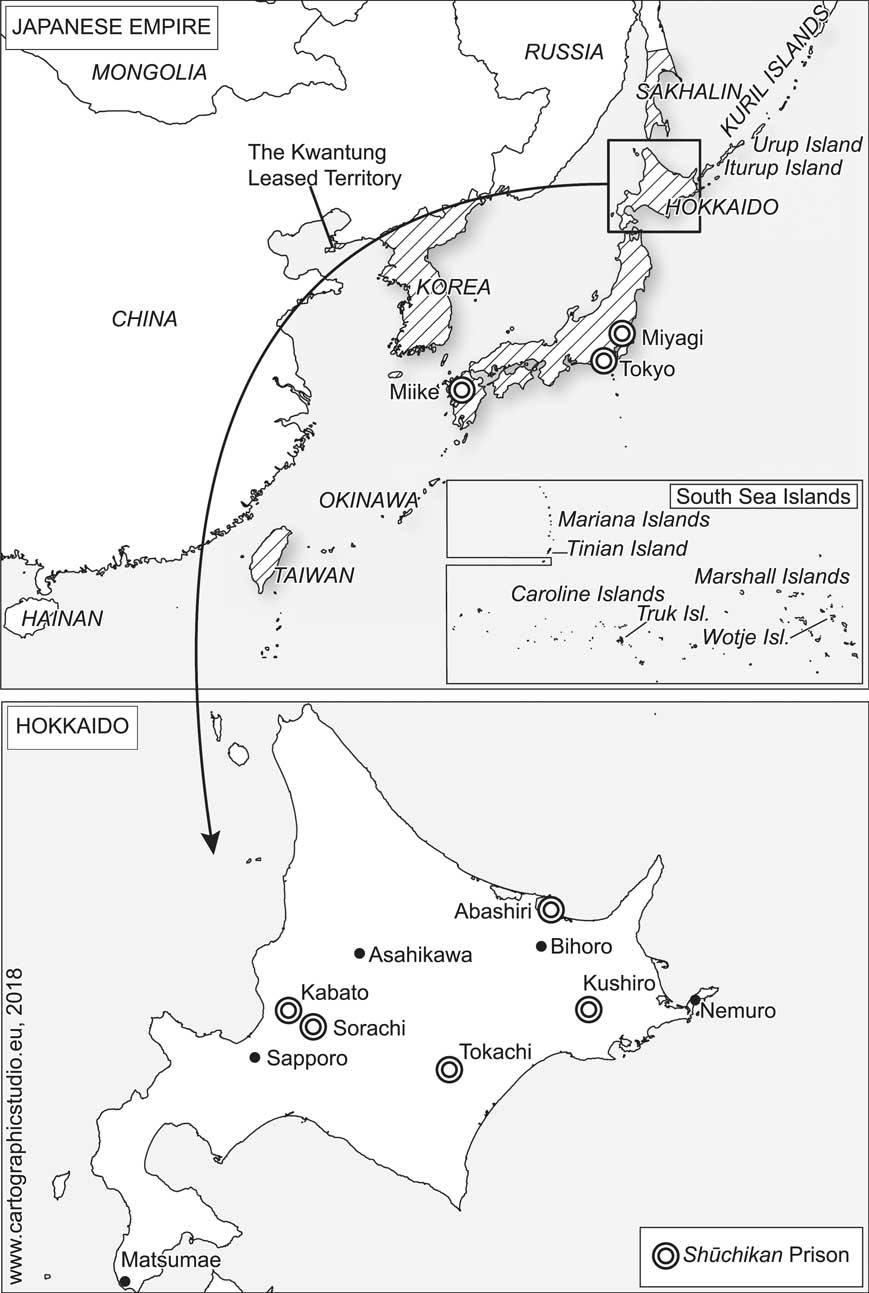

Shūchikan prisons were for convicted felons and political offenders. There were three shūchikan on the mainland, at Tokyo, Miyagi, and Miike, and there were five on Hokkaido at Kabato, Sorachi, Kushiro, Abashiri, and Tokachi. The shūchikan on the mainland held convicts sentenced to imprisonment without labour and, temporarily until they could be transported to Hokkaido, convicts sentenced to penal servitude and transportation.

Figure 1 Locations of shūchikan prisons on the Japanese mainland and Hokkaido. Map based on a sketch by the author. Produced with reference to Ramon H. Myers and Mark R. Peattie (eds), The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895–1945, (Princeton, NJ, 1984), p. 53; Tanaka, Nihon shihonshugi, p. 119.

Transportation to Hokkaido began in 1881. Among the five Hokkaido prisons four were built inland where the Japanese had not yet settled. The convicts were used to clear the land, for agriculture, and in mines. Furthermore, they were initially expected to become settlers themselves after completing their terms, in order to supplement the limited numbers of free migrants. Prisons offered business opportunities which attracted merchants and craftsmen to the prison sites, and Kabato, Sorachi, and Kushiro prisons, surrounded by dense forests, were rapidly transformed into towns.Footnote 15 From 1886 to 1893, a road across Hokkaido from east to west was constructed by convict labour to connect Sapporo, the island’s capital, with the prison towns. Twenty-five tondenhei (farmer-soldier) towns were built along the road, with the result that it became possible for settlers on Hokkaido to move inland, and the migrant population rapidly increased in the 1890s.

TOWARDS THE ABOLITION OF TRANSPORTATION

The fluid status of Hokkaido in penal code reform

Penal transportation to Hokkaido did not last long. The penal code was revised in 1907 when the principal punishments were categorized as the death penalty (shikei), imprisonment with hard labour (chōeki), imprisonment without hard labour (kinko), a fine (bakkin), and custody (kōryu). Those sentenced to imprisonment with or without hard labour were incarcerated for life or for a finite term of between one month and twenty years. Those given custodial sentences were detained for between one day and a month. Transportation to an island was officially abolished under the new penal code and, in a sense, the code’s revision was part of the process of the ideological incorporation of Hokkaido into the mainland.

One of the major backgrounds to the revision of the penal code and the elimination from it of transportation was the establishment of the constitution, work on which began in 1882 and which was modelled on the constitution of the German Empire because that constitution preserved the royal prerogative. France had become a republic and Britain’s parliament retained strong authority, so that the Japanese, wishing to both preserve the emperor’s prerogative and to introduce a Western-style legal system to gain respect as a “civilized nation”, considered the German legal system to be ideal. Later, in 1886, the Japanese government began to formulate other laws and to amend the penal code,Footnote 16 and to promote consistency with the constitution those new laws, too, were modelled on German ones. Because the German penal code did not prescribe transportation, the Japanese eliminated from their new code articles relating to penal colonies.

Another background to Japan’s turn towards anti-transportation was its revision of the unequal treaty that the Tokugawa Shogunate had concluded with Western powers in the mid-nineteenth century. During negotiations in 1886, Britain and Germany had asked Japan to enact Western-style laws, which they demanded should include a revised penal code as a condition for revision of the treaty. The Ministry of Justice had launched a revision of the penal code as early as 1882, early drafts containing articles envisaging enhancements of the penal colony system, such as permission to be given to the transported to settle in the penal colony with their families after a number of years of imprisonment.Footnote 17 However, under the influence of the legal reforms mentioned above, that provision was deleted from the 1887 draft. Another amendment involved the deletion of terms such as shimachi (island) and naichi (home territory or the mainland), and that was significant because the term shimachi distinguished Hokkaido as a destination for transportation from the mainland. Deletion of those terms therefore implied erasure of that distinction. The penal code did not fit the reality of punishment, according to the Ministry of Justice, which justified the changes as follows:

[In the previous draft,] the destination of transportation was specified as “an island”. However, Japan does not have appropriate islands. Thus, in the case of transportation, it is necessary that administrators designate a destination. The current penal code also prescribes transportation to an island. However, it does not actually seem to have occurred.Footnote 18

The comment that “transportation to an island” did not seem to have occurred is surprising and seems to have stemmed from a series of comments on the Japanese penal code written by a German jurist named Albert Friedrich Berner. Berner remarked that the current Japanese penal code was too complicated and pointed out that the German penal code referred to just four categories of imprisonment. Berner suggested, too, that no distinction was necessary between shimachi and naichi, because Japan is an island country anyway. Furthermore, an “island” for transportation should be sufficiently remote to deprive deportees of the freedom to return to their home country. Berner certainly seems to have regarded Hokkaido as part of the Japanese mainland and to have assumed that any regulation of the destination of transportation was irrelevant.Footnote 19

According to Berner’s view, the movement of convicts, which had been practised in Japan over the previous few years, was not seen as “transportation”, which allowed for an easy shift of the penal system from the French model to the German model because transportation was easily re-interpreted as imprisonment. A simultaneous advantage was that the changed thinking suited the Japanese doctrine that Hokkaido was “historically” Japanese territory, which was further correlated with the reason for deleting the term naichi from the penal code. The 1880 penal code had prescribed that imprisonment with and without hard labour were to be served “in mainland (naichi) prisons”, while the 1887 draft says simply that sentences with and without hard labour were to be served “in prisons”. The Ministry of Justice explained the change by saying that it was because all Japanese islands were now part of the mainland, so that it was unnecessary to make a distinction. If imprisonment were restricted to naichi prisons, convicts sentenced to imprisonment with or without hard labour in Sapporo, Nemuro (both prefectures in Hokkaido), or Okinawa could not be incarcerated in prisons there.Footnote 20 Surprisingly, that comment implies that the Ministry of Justice regarded Hokkaido and Okinawa as equivalent to the mainland, although strictly speaking they were not.

The Ministry of Justice took the view that transportation to an island had not occurred because their view was that Hokkaido was equivalent to the mainland. The distinction between servitude and transportation originally designed as sentences for Hokkaido, and imprisonment with or without hard labour which were sentences originally designed for the mainland, therefore made no sense. In other words, the difference between transportation and imprisonment had become blurred. In the 1890 draft submitted to the Imperial Diet, servitude and transportation were eliminated and absorbed into imprisonment with or without hard labour. The Ministry of Justice explained the changes as follows:

In the first place, the distinction between islands and the mainland is not clear in our country. […] In countries which have colonies, this prescription means removal of undesirable people from the mainland to the colonies, and it must contribute to the development of colonies. However, in our country, this is nothing but a nominal clause. Hence, in this revision, we deleted the designation of the place of punishment.Footnote 21

It was seventeen more years before the new penal code was promulgated, but following the 1890 draft the abolition of servitude and transportation as forms of punishment and the deletion of expressions such as “transportation to an island” and naichi were formalized under the Japanese penal code.

Shimachi, an island, under the penal code

The reform of the penal code effectively exposed Hokkaido’s ambiguous status as colony and region of the mainland, an ambiguity caused by a gap between ideology and reality. Although the 1880 penal code did not indicate a specific destination island for transportation, it was obvious in the late nineteenth-century context which island was meant. Transportation to Hokkaido was one of the policies the Meiji government sought to introduce as soon as they assumed power, and the members of the committee drafting the 1880 penal code assumed it would be the destination.Footnote 22 The 1881 prison code prescribed that shūchikan prisons in Hokkaido should hold convicts sentenced to servitude and transportation,Footnote 23 but in 1889, prior to the 1907 revision of the penal code along the lines of the German code,Footnote 24 that clause was modified to specify shūchikan as the prison for those sentenced to penal servitude, transportation, and imprisonment with hard labour according to the old law.Footnote 25 Hokkaido was now omitted as the destination of transportation,Footnote 26 a revision reflecting prison administration at the time. Shūchikan prisons in Hokkaido had become full and were unable to receive all the convicts who were supposed to be transported. Inevitably then, shūchikan on the mainland continued to confine them. Nevertheless, in his Nihon kangokuhō kougi [A Lecture on the Japanese Prison Code] published in 1890, the jurist Shigejirō Ogawa explained that convicts sentenced to penal servitude and transportation were to be transported to an island – Hokkaido.Footnote 27 Although shūchikan prisons on the mainland, too, held such convicts, they did so in their capacity as Kariryūkan, prisons the function of which was to confine convicts temporarily until they could be transferred to Hokkaido.Footnote 28 According to Ogawa’s understanding, the expression “an island” in the penal code was not intended geographically but was a political concept based on the binary opposition of “island” and “mainland” (naichi). In practice “island” meant nothing other than Hokkaido, which was obviously not included in the mainland.

On the other hand, the revision of the prison code in 1889 allowed for a literal interpretation regarding the place of punishment for penal servitude and transportation. In his Nihon keihō ron [Theory on the Japanese Penal Code, 1894], the jurist Asatarō Okada had the following to say:

The prison code (1889) designates shūchikan prisons as facilities for the incarceration of convicts sentenced to servitude, transportation, and imprisonment with labour according to the old law. Three shūchikan prisons are built on the mainland. Therefore, although the penal code prescribes the transportation of convicts sentenced to servitude and transportation to an island, this is not necessary according to the prison code. In practice, transportation has not always been used.Footnote 29

According to Okada, “an island” in the penal code referred to Hokkaido.Footnote 30 However, as shūchikan prisons on the mainland functioned as kariryūkan (temporary prisons for those sentenced to servitude and transportation), their status became unclear.Footnote 31 Okada took the view that reference to transportation should be deleted as mainland shūchikan in practice confined convicts sentenced to penal servitude and transportation. Shigejirō Ogawa, by contrast, considered that it was mainland shūchikan which ought to be abolished.Footnote 32 Although Okada recognized the benefit of convict labour for the development of Hokkaido, he concluded that the penal code, which prescribed penal transportation, should be revised in view of the high cost of transportation and prison management in a barren land.Footnote 33 While Ogawa and Okada held opposite views on penal transportation, both thought that “island” (shimachi) in the 1880 penal code referred to Hokkaido, which both viewed as being distinct from the mainland.

As mentioned earlier, the Japanese had regarded Hokkaido as their territory since the early modern period based on the doctrine that places inhabited by the Ainu were Japanese. In reality, to secure the island against Russian expansion the Japanese government found itself obliged to introduce strategies similar to those used by Western countries in their colonies. Kentarō Kaneko, who investigated Hokkaido in 1885 and proposed a policy plan for its development, which included the use of convict labour, was referring to Western colonial policies when he asserted that mainland policies and systems should not be adopted for Hokkaido.Footnote 34

Jurists and Kaneko, the government official, clearly regarded Hokkaido as distinct from the mainland, so that Hokkaido’s status as decreed by the Ministry of Justice in its reform of the penal code was not the commonly understood view of it. Only by assuming that Hokkaido was equivalent to the mainland would it be possible to deny that transportation was being practised in Japan, by re-designating as “incarceration” the continued sending of convicts to Hokkaido. In the next section, we shall see how that was done. The process of eliminating transportation in name only from the penal code therefore came about because the Japanese government sought consistency between national ideology and the legislative system.

Demand for convict labour and criticism

From 1880 to the early 1890s, just when articles concerning penal transportation were being deleted as a result of reform of the penal code, extramural convict labour was at its peak on Hokkaido. Even so, although the migrant population was steadily increasing, it was far from being enough to make up for the labour shortage. In about 1891, Teruchika Ōinoue, the Governor of Kabato prison in Hokkaido, proposed that male convicts serving sentences of imprisonment with hard labour should be sent to Hokkaido so that they could be utilized as a labour force.Footnote 35 In 1891, a petition was submitted to the House of Peers proposing transportation to Hokkaido of those convicts sentenced to more than two years’ imprisonment.Footnote 36 Both those instances testify to the high demand for and poor supply of cheap labour on Hokkaido, and in the House of Peers certain members were sympathetic to the petition, for the number of migrants had not increased sufficiently. However, other members were against it, arguing that it would make Hokkaido a land of vice. That turned out to be the view of the majority, so that in the end the bill was not sent to the government.

By that time, criticism of transportation of convicts and of extramural prison labour was increasing. In 1892 and 1895, a number of members of the House of Representatives claimed that the policy was propagating an unfavourable image of Hokkaido as a place where felons were sent, so that potential free migrants might be disinclined to move there. Transportation was, they said, an obstacle to the development of Hokkaido.

What caused settlers’ antipathy to shūchikan and convicts in general were the crimes of the convicts and their tendency to escape. The number of escapes from shūchikan in Hokkaido was much higher than from other prisons in Japan, and the more extramural prison labour was used the more convicts escaped. In 1891, 136 escapes were recorded out of a population of 6,850 convicts, and forty per cent of them were never recaptured.Footnote 37

The government recognized the harmful effect of the transportation system. In 1893, after his inspection tour to Hokkaido, the Home Minister Kaoru InoueFootnote 38 proposed the gradual abolition of shūchikan prisons on Hokkaido Island and the establishment of a prison on another island if necessary, and that convicts due to complete their terms within a year should be sent back to mainland prisons. Inoue gave two reasons for his proposal. One concerned prison administration. He explained that the number of convicts sentenced to penal servitude and transportation was increasing annually. Shūchikan prisons on Hokkaido had reached capacity and could not receive all of them. Therefore, the prison code had been revised to enable mainland shūchikan to house such convicts. Inoue concluded that, despite what the penal code said, convicts sentenced to penal servitude and transportation were not always transported to Hokkaido. The minister’s other reason concerned migration policy. Inoue argued that, at that time, the number of free migrants was increasing in Hokkaido, but that they were prone to threats and even harm from escaped convicts. Moreover, he claimed that if convicts were to be officially released on Hokkaido they too might harm settlers. The cabinet approved Inoue’s proposal in 1894.Footnote 39

In fact, the transportation system went into almost complete decline following the aforementioned government decision and a subsequent amnesty offered on the occasion of the Empress Dowager’s death in 1897. After 1897, the total number of convicts transported dropped by two thirds (Table 1), while repatriations meant that the number of convicts on Hokkaido shūchikan decreased too. That, in turn, affected the development of Hokkaido insofar as it depended on convict labour for work, such as clearing land. Indeed, by 1899, the governor of Hokkaido shūchikan,Footnote 40 Kingo Ishizawa, was writing to the head of the prison bureau of the Home Ministry to inform him that convicts in Hokkaido’s shūchikan now amounted to fewer than 3,000, meaning a shortfall of 2,800 from the prison’s full capacity. Ishizawa further complained, “[w]e will have difficulties to accomplish projects in the next fiscal year. Land clearing will get much more behind”, and went on to request transportation of convicts from the mainland.Footnote 41 In the event, 500 convicts were sent to Hokkaido that year from Tokyo, Miyagi, and Miike shūchikan, but, given that fewer convicts were sentenced to penal servitude and transportation, it was impossible to prevent a chronic shortage of convicts on Hokkaido.Footnote 42

Table 1 The number of convicts sentenced to servitude and transportation.

Sources: Naimushō (ed.), Dainihonteikoku naimushō tōkei hōkoku dai 10 kai (Tokyo, 1895); Shihōshō (ed.), Shihōshō kangokukyoku tōkei nenpō dai 1 kai (Tokyo, 1901); Shihōshō (ed.), Shihōshō kangokukyoku tōkei nenpō dai 2 kai (Tokyo, 1905).

Repatriation of convicts was an extremely financially inefficient policy. Criticism of transportation had initially arisen on the grounds of cost,Footnote 43 and repatriation only made the whole operation more expensive. From 1895, Home Ministry officials sought a way to settle convicts in HokkaidoFootnote 44 and, in 1899, the prison bureau inquired with Hokkaido’s government about the possibility of releasing convicts on the island who had expressed a willingness to settle and seek proper employment. The Ministry explained that many of the convicts sent back to the mainland subsequently moved back to Hokkaido, so the suggestion was that the state was incurring unnecessary expense for repatriation. The Ministry claimed that, unlike in the past, freed convicts could be expected to contribute to the development of Hokkaido and would be unlikely to harm free migrants. The Ministry further complained that the decline in the number of convicts on Hokkaido was causing delay to projects requiring their labour. However, the Director General of the Hokkaido government rejected the plan because there were still too few policemen on Hokkaido.Footnote 45 In fact, the Hokkaido government did not want convicts to settle there, because the number of free migrants was increasing sharply from the 1890s, and it had no real expectation that convicts would become good settlers.

Ineffectiveness of transportation as punishment and rehabilitation

In the Imperial Diet of 1895, in a reply to an inquiry from members of the House of Representatives who opposed transportation, the government explained its position on that and on the gradual closing of shūchikan and the repatriation of convicts.Footnote 46 That change in policy, along with the penal code reform proposed in the first Imperial Diet convened in 1890, was seen as an admission by the government that penal transportation to Hokkaido had been a failure. In the Kangoku zasshi [Prison Journal] in 1895 a writer, Kaneshirosei, wrote that although transportation to Hokkaido was inevitable under the circumstances of the time, “it is established knowledge that the transportation of criminals to overseas or islands is not a wise policy. As readers might admit, cases of France and Russia are such examples”.Footnote 47 He briefly introduced a French jurist’s essay against transportation, which argued that the appropriateness of the system should be considered from three aspects: rehabilitation of convicts, its effect on the place of imprisonment, and problems for the mainland. The essay concluded that transportation was ineffective as a means of rehabilitating convicts, that it threatened public safety, and that it placed a financial burden on the state.

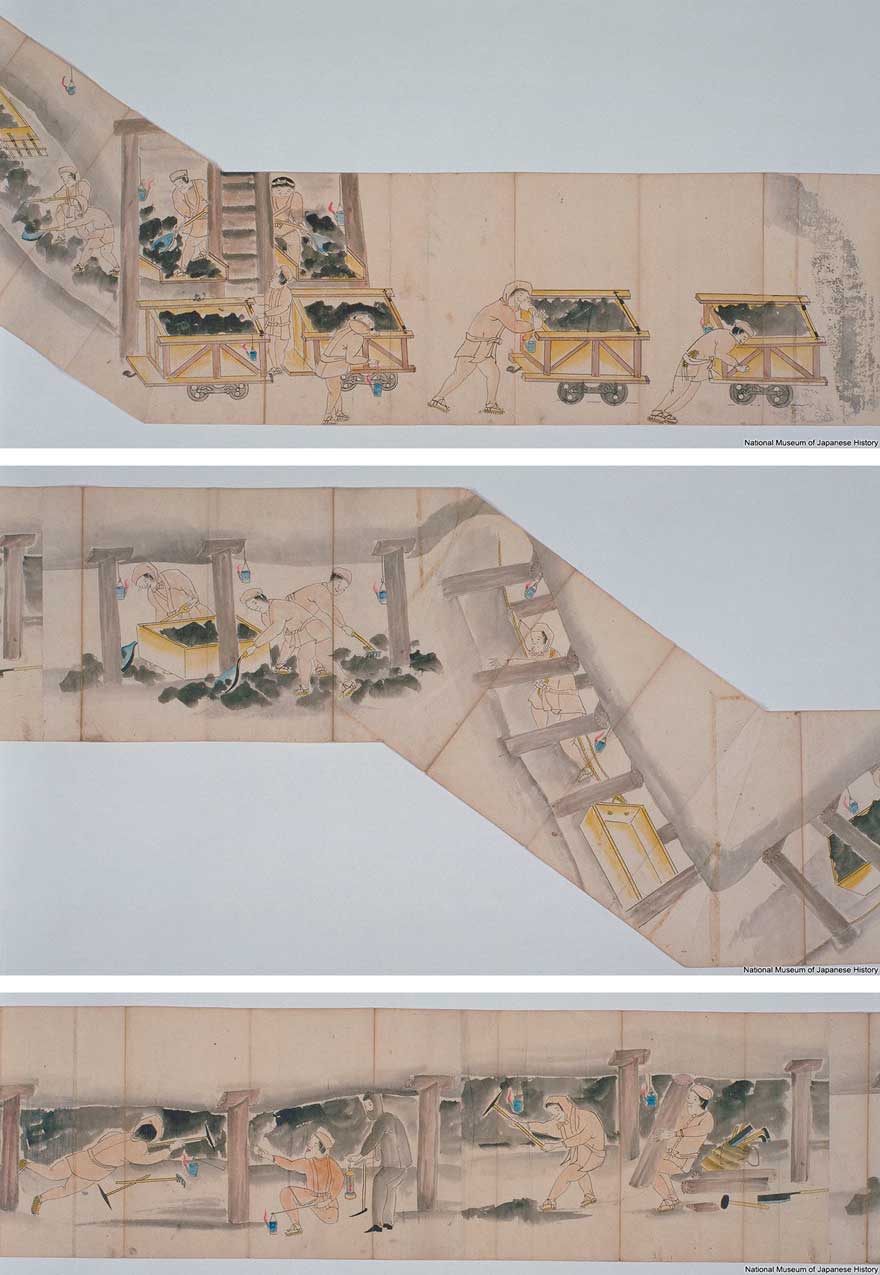

Although Kaneshirosei’s statements were about theoretical debates, the above points were precisely the problems mentioned in connection with the evaluation of transportation to Hokkaido, which were going on both within and outside the Japanese government at that time. We have already encountered critical voices addressing the second and third points, but on the first point I will now examine the contribution of Asataro Okada, who discussed the effects of convict labour at the Horonai coal mine (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Shūjin rōdō emaki [Illustrated Handscroll of Convict Labour], c.1881–1889. Painted by a convict in Sorachi shūchikan. It depicts the mining process at the Horonai coal mine. Courtesy of the National Museum of Japanese History.

Okada visited Horonai in 1893. He first described the dreadful working environment at the mine, in which many convicts were suffering from disease and injury because of poor hygienic conditions and frequent accidents there. Okada met many convicts who had lost limbs and discovered that more than fifty people had been blinded. However, to his surprise, there were many convicts who were happy to work in the mine.

Okada then noted that the mine included many long and narrow galleries, which were rarely frequented by guards, and where convicts could therefore do as they liked – not least escape. For example, on one occasion, a group of convicts drove a tunnel up to ground level and absconded. If they did not care to escape, the convicts could still eat and drink in peace in the bowels of the mine; they brought rice to one of tunnels and used it to brew sake, while abandoned galleries were used to store tobacco, food, and illicit liquor. Gambling and sexual activity took place too.

Okada concluded that the mine had become a kind of paradise, where certain types of impenitent convicts might want to go. He saw, too, that convicts wishing to mend their ways would be exposed to the deadly situation.Footnote 48 Similar observations may be seen in official reports by the Home Ministry and in the memoirs of prisoners.Footnote 49 In general, then, shūchikan prisons on Hokkaido were considered ineffective or even harmful as a means of punishment and provided no rehabilitation.

FROM HOKKAIDO TO COLONIES

After the incorporation

In 1903, the vote was given to migrants to Hokkaido, which meant the completion of Hokkaido’s incorporation into the mainland.Footnote 50 In the same year, the shūchikan prison system was abolished and each penal colony site became a general prison. Extramural prison labour was abolished around 1904, the penal code was revised in 1907, and the already dying penal transportation system was officially abolished in 1908. Hokkaido was the first successful example of the incorporation of a new territory into the Japanese mainland, a forerunner of an approach to Japanese territorial expansion later called “extending homeland ideology”.

After the incorporation of Hokkaido, the concept of “the mainland” became more problematic. Even after the abolition of transportation, long-term prisoners were continually sent to prisons there. Under the new penal code promulgated in 1907, terms of imprisonment with or without hard labour became longer, with a maximum of twenty years, rather than the fifteen years of the 1880 penal code. As a result, the convict population increased,Footnote 51 leading, for example, Chohei Minota, a Chief Warder at Kosuge prison (the former Tokyo shūchikan), to write in his memoir about his experience of escorting 150 prisoners to Abashiri in 1911.Footnote 52 However, that custom was not referred to as penal transportation, because officially Hokkaido was by then part of the mainland and the transportation system no longer existed.

Extramural prison labour had been abolished, but in 1933 it was revived on Hokkaido,Footnote 53 first for railway construction by convicts from the Abashiri prison on the former penal colony site and then at Asahikawa prison, which was the successor to the Kabato shūchikan, closed in 1919. Asahikawa city was in central Hokkaido, and, in the late nineteenth century, was the site of a camp for convicts who built roads and military barracks. After the Seventh Division of the Japanese Army was formed in 1900, Asahikawa became a garrison city and the convicts were employed not only for public works, but for construction and farm work for the army too.

That period did not see a significant number of instances of escape attempts among the convict labourers, nor was there much convict crime. Rather, their diligence and the quality of their work impressed many people. For example, on 13 June 1938, a newspaper noted that the quality of the Asahikawa prison convicts’ work on the construction of a bank far exceeded that of general labourers.Footnote 54 However, as background to such a positive evaluation we should take into account various illegal forced labour practices in use at the time on Hokkaido in the aftermath of the abolition of extramural convict labour. To supplement labour shortages, agents illegally sent Japanese vagrants and paupers to Hokkaido, who were then confined and forced by contractors to work, under violent supervision. Compared with such forced labour, convicts appeared to be more disciplined and more highly motivated. Convict labour was therefore revived not simply as a form of severe punishment for felons, but also as a kind of rehabilitation programme. Aiming to reintegrate prisoners into society, the Ministry of Justice introduced the progressive stage system in 1933, under which more diligent convicts could work towards greater freedoms in prison. In Hokkaido, extramural prison labour was rediscovered as one means to that end.Footnote 55

After the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937, the mainland, too, experienced a shortage of labour, so that, following the example of Hokkaido, extramural prison labour was reintroduced in other parts of the mainland.Footnote 56 From 1937 to 1940, convicts in Urawa prison (Saitama prefecture) constructed a rowing lake for the Games of the Twelfth Olympiad, which had been scheduled for 1940 but was not held – although, incidentally, the same lake was later improved and used in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.Footnote 57

After 1938, convicts became an important source of labour for the construction of naval installations. The Navy requested the use of the Abashiri prison population to construct a naval airbase at Bihoro in eastern Hokkaido; in the end, more than a thousand convicts were sent there from prisons all over Japan to join the 200 convicts from Abashiri.Footnote 58 The success of that project led to a series of instances of the use of convicts to construct naval installations and, in 1939, the Naval Ministry decided to employ convicts to construct air bases in the South Sea Islands. The Ministry requested only healthy, strong, and non-violent prisoners with few dependants and whose remaining terms were less than eighteen months.Footnote 59 The specification of “few dependants” suggests that the Navy was allowing for the possibility that convicts might die in service. In total, 2,400 Japanese convicts were sent to Yokohama and then to Tinian Island and Wotje Island (1939–1941),Footnote 60 while 1,300 were sent to the Truk Islands (Chuuk Islands) (1941–1945).Footnote 61 In the Truk Islands, construction work continued during the Pacific War, and US air raids after 1944 cut Japanese supply lines, which caused serious food shortages.Footnote 62 In such circumstances, many convicts died of starvation and, to reduce pressure on provisions, a number were killed by prison guards for trifling offences such as petty theft as well as for trying to escape. According to Sei Kubota, who survived, only fifty of 490 convicts were still alive at the end of the war.Footnote 63 Later, Akira Masaki, who was head of the penal administration bureau at the Ministry of Justice at the time, admitted that the treatment of convicts in the Truk Islands was as inhumane as it had been in nineteenth-century Hokkaido.Footnote 64 During the Pacific War, the Navy employed convict labour for shipbuilding, too, and the army began to use convicts to build air bases.

Taiwan and Korea

As in the case of Hokkaido, neither Taiwan, nor Korea were officially referred to as colonies, although, in time, the term Gaichi (outer territory) was introduced to refer to Japanese territories “not yet” included as part of the mainland. Gaichi included Taiwan, Korea, Karafuto (Southern Sakhalin), Kwantung Leased Territory, and the South Sea Islands.

In Taiwan and Korea, the Japanese mainland penal code was not formally enforced, with Governors General instead promulgating their own ordinances concerning punishment. Such ordinances were principally identical to the mainland penal code although with certain additional provisions, for example one which authorized flogging,Footnote 65 but neither transportation, nor extramural prison labour were introduced. Basing its approach on the 1880 penal code, the office of the Governor General of Taiwan sought to send convicts to Miike shūchikan, but when the Home Ministry refused, the focus moved to the construction of prisons.Footnote 66 At the time of Korea’s annexation, transportation had already been abolished on the mainland so that in both Taiwan and Korea the chief form of punishment was imprisonment and all convict labour was principally intramural.

Throughout the war, and after its resurgence on the mainland, extramural prison labour was introduced in Taiwan and Korea, where it seems that construction work by convicts began in 1942.Footnote 67 In Taiwan, it seems to have begun in 1943,Footnote 68 when Taiwanese and Korean convicts were sent to Hainan Island to work in mines and to construct a railway for the Navy.Footnote 69

As Japanese convicts were sent to the South Sea Islands, Korean and Taiwanese convicts were selected based on certain criteria, such as, in the case of Koreans for example, that they should be from twenty to forty years old, healthy, strong, and non-violent and with remaining prison terms of between eighteen months and three years. Those sentenced for political crimes were not selected.Footnote 70 For naval installations, relatively “good” convicts were selected whose remaining terms were reasonably short while still being long enough to complete the work.

The idea that extramural prison labour might be effective for prisoners’ rehabilitation was spreading among prison officials in Korea too. The adoption of extramural labour in Japanese colonies was regarded not as the introduction of a new style of punishment, but as a new means of rehabilitation to turn convicts into good Japanese citizens. In the journal of the Bureau of Legal Affairs of the Korean Governor General, a number of writers argued that extramural prison labour was more effective than imprisonment for rehabilitation and that, through such labour, convicts could contribute to the Japanese Empire and become diligent imperial subjects.Footnote 71 However, it seems obvious that convicts in the colonies were exposed to harsher labour conditions. While the South Sea Islands had been a Japanese colony since 1919, Hainan was occupied by Japan in 1939 and, in 1943, conflict between the Japanese Army and Chinese guerrillas was ongoing. Prisoners in Japanese colonies were sent to more dangerous sites than their Japanese mainland convict counterparts. We also know from the testimonies of eyewitnesses and survivors that convicts were exposed to violence and ill treatment by the Japanese Army. It is unclear how many convicts were able to return from Hainan. One Korean convict said that he was sent to Hainan with 150 other convicts, and that most of them were dead.Footnote 72

Through extending homeland ideology, transportation and extramural prison labour were initially not introduced to the colonies, but, following the same reasoning, they were introduced in World War II. Hokkaido was the point of departure of the wartime convict labour regime, which, in turn, was a legacy of nineteenth-century convict labour practice.

CONCLUSION

Japanese territorial expansion began with Hokkaido. Although Hokkaido had been regarded as a Japanese territory long before its actual annexation, the Japanese government resorted to colonial policies similar to those of the Western powers in order to incorporate the island into mainland Japan. Penal transportation was one such strategy, which enabled rapid settlement of a Japanese population to secure the new territory at its northern border. That fact betrays Hokkaido’s initial status as a colony, but, in the sense that it was transformed into homeland territory through colonial policies, Hokkaido amounted to the first step towards Japanese nation-state building and the imperial expansion achieved through “extending homeland ideology”.

It was in the peak period of convict extramural labour in Hokkaido that the Ministry of Justice launched a reform of the penal code and deleted clauses concerning transportation. However, the revision was not initiated in response to the practical problems of penal transportation. In fact, the Japanese were more concerned about amending their legal system from the French to the German model, and with diplomatic matters such as the revision of an unequal treaty. During the course of penal code reform, the status of both Hokkaido and penal transportation itself were redefined. That said, even after Hokkaido’s incorporation into the mainland, long-term prisoners were still sent to Hokkaido. Their sentences were now seen as amounting to imprisonment on the mainland.

High demand for labour and its low supply were continuous challenges for Hokkaido’s politicians and administrators. During the 1930s, the former penal colony sites reintroduced extramural prison labour for the same reason that it was first introduced in the late nineteenth century, namely the shortage of labour resulting from a small population. However, it was not a simple revival of punitive hard labour for felons in a colony; it was reintroduced in the guise of a rehabilitation programme that had been newly introduced in mainland prisons as a part of penal reform. In a practical sense, transportation and extramural convict labour on Hokkaido continued even after the penal code’s revision in 1907.

After Hokkaido’s incorporation into Japan proper, the penal transportation and convict labour that had once held sway there were reframed as an imprisonment and rehabilitation programme. During wartime, the system spread from the mainland to other areas, and, in accordance with the approach of “extending homeland ideology”, was introduced in Korea and Taiwan too. It was introduced not as a particular punishment for convicts in colonies, but as an extension of the new rehabilitation programme extended from mainland prisons. It was presented rather as an opportunity for convicts to contribute to the development of the Japanese Empire and thereby to become good imperial subjects.