No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

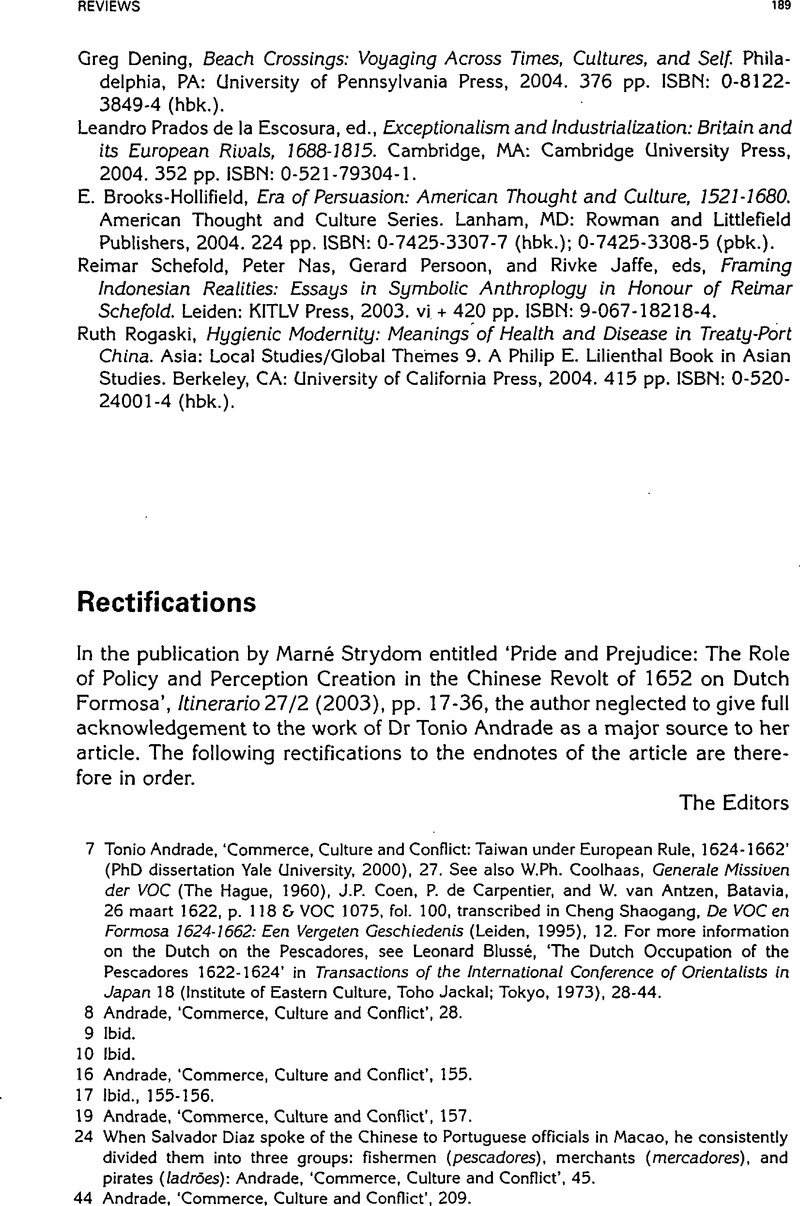

Rectifications

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 June 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Rectifications

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Research Institute for History, Leiden University 2005

References

7 Andrade, Tonio, Commerce, Culture and Conflict: Taiwan under European Rule, 16241662 (PhD dissertation Yale University, 2000), 27.Google Scholar See also Coolhaas, W.Ph., Generate Missiven der VOC (The Hague, 1960)Google Scholar, J.P. Coen, P. de Carpentier, and W. van Antzen, Batavia, 26 maart 1622, p. 118 VOC 1075, fol. 100, transcribed in Shaogang, Cheng, De VOC en Formosa 16241662: Een Vergeten Geschiedenis (Leiden, 1995), 12.Google Scholar For more information on the Dutch on the Pescadores, see Blusse, Leonard, The Dutch Occupation of the Pescadores 16221624 in Transactions of the International Conference of Orientalists in Japan 18 (Institute of Eastern Culture, Toho Jackal; Tokyo, 1973), 28–44.Google Scholar

8 Andrade, ‘Commerce, Culture and Conflict’, 28.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

16 Andrade, ‘Commerce, Culture and Conflict’, 155.

17 Ibid., 155–156.

19 Andrade, ‘Commerce, Culture and Conflict’, 157.

24 When Salvador Diaz spoke of the Chinese to Portuguese officials in Macao, he consistently divided them into three groups: fishermen (Pescadores), merchants (mercadores), and pirates (ladrōes): Andrade, ‘Commerce, Culture and Conflict’, 45.

44 Andrade, ‘Commerce, Culture and Conflict’, 209.