Introduction

Training for ordained ministry within the Anglican Church in England and Wales has undergone considerable shifts during the past fifty years. Although the role of the training incumbent has remained a constant feature, this role has taken on a new significance and a revised set of expectations in the twenty-first century. In the 1970s there was a clear distinction between initial ministerial education rooted in a theological college and post-ordination training rooted in a parish-based curacy. At that time the emphasis during the college-based experience was placed on academic and theological education, while the emphasis during the curacy was placed on the practical aspects of ministry. On ordination to the diaconate, the curate was placed under the oversight of an experienced vicar or rector designated as training incumbent. The selection of training incumbents was largely influenced by their experience and the size of the church they led. In the decades immediately after the Second World War, it was still common for an established training incumbent to have oversight of several curates.

During the early years of the twenty-first century the changing role of the training incumbent and the increasing professionalization of that role has been reflected in the reconceptualization of Initial Ministerial Education (IME) to embrace two distinct but connected phases. Phase one IME (years 1–3) remains within a theological college (generally for full-time training) or within a theological course (generally for part-time training) and embraces aspects of practical ministerial formation within church and other context-based placements. Phase two IME (years 4–7) is placed within the oversight of the diocese and in the hands of a designated training incumbent. With the added responsibilities for delivering phase two of IME it has become uncommon for training incumbents to have oversight of more than one curate at the same time.

Such changes in the role of training incumbents was heralded by the report, Formation for Ministry within a Learning Church,Footnote 2 colloquially known as the Hind Report. This significant document identified the need for an overhaul of attitudes to parish-based training. In turn, this report was succeeded by Shaping the Future,Footnote 3 which attempted the important task of bringing rigour to the selection of training incumbents. Shaping the Future moved away from using ministers whom the bishop happened to like or was seeking to reward; away from the use of busy parishes that needed an extra pair of hands to assist with the ministerial workload; and towards appointing reflective practitioners, who were skilled trainers and could demonstrate an aptitude for the role. In Appendix 4, Shaping the Future set out clear criteria for those appointed to the role of training incumbents, and did so under the two following headings: training incumbent proforma, and future expectations.

Training incumbent proforma:

-

1. Models strategic, reflective, theological thinking in parish leadership;

-

2. Engages regularly in in-service training and takes time for reading and reflection (Study week?);

-

3. Takes time for prayer and reflection (Daily Office, Retreats);

-

4. Is self-aware, secure but not defended, vulnerable but not fragile;

-

5. Has demonstrated a collaborative approach in discussion, planning and action in the parish;

-

6. Has been able to let go of responsibility to others, after appropriate training and supervision;

-

7. Has shared ministry, including difficulties and disappointments, with colleagues;

-

8. Has a personal theological and spiritual position which is creative and flexible so as to be able to engage and work constructively with different theological and spiritual positions;

-

9. Has a record of allowing colleagues to develop in ways different from their own;

-

10. Has an ability to interpret the social dynamics of the parish and to develop a strategy for mission and the implementation of change;

-

11. Has a genuine desire to be part of the training team rather than wanting an assistant and is therefore willing to agree to enable training experience that makes use of prior experience;

-

12. Has the ability to help the curate in the process of integrating their theological studies with ministerial experience.

Future expectations

-

1. Will undertake further study to function as a Training Incumbent;

-

2. Will give time to supervision and planning of training;

-

3. Is willing to receive supervision in the role of the Training Incumbent;

-

4. Will invest effort in mobilizing available resources, outside as well as within the parish for the training of a curate;

-

5. Will give the Initial Ministerial Education, IME, programme a high priority and work in partnership with diocese and bishop’s officers.

Several of these criteria illustrate a clear change of thinking. ‘A willingness to undertake further training’ recognized both that additional skills were necessary to be effective in the training role, as well as signalling the importance of employing ministers who paid more than lip service to the concept of life-long learning. A reference to self-awareness and vulnerability in the criteria suggests a recognition that some ministers may be insecure or otherwise unstable and make unsuitable training incumbents, but does not go so far as to acknowledge that personality fit might be an issue to consider: that a potential training incumbent might do very well with one curate but far less well with a curate of a different psychological type. The criteria also include an expectation that the newly appointed training incumbent will have the ability to help the curate integrate their theological studies with ministerial experience. This is a further signal that in-parish training is no longer seen as merely a set of practical skills to be acquired. It is worth noting that neither report thought it necessary to conduct research among either curates or training incumbents to evaluate current provision.

Researching the Experiences of Curates

The importance of researching the experience of curates is highlighted by BurgessFootnote 4 and Tilley,Footnote 5 who in largely qualitative research report widespread unhappiness with the quality of training provided to curates, amounting in Burgess’s case to as many as half of all respondents. Similarly, an anonymous letter to The Church Times (29 January 2010) complained:

As a curate, I had a bully for a training incumbent. It took 30 months of a 36 month curacy to realise this, and 34 months of 36 months to be seconded to another parish…. Furthermore, the working relationship between curate and incumbent is unique and intense. This needs to be seriously reviewed at national level…. My situation was not unique. There were many curates with muted cries for help. (p. 15)

The point about the uniqueness and intensity of the relationship is a crucial one. The working relationship between training incumbent and curate can bring two individuals together, who may well have met only a handful of times prior to the relationship being formalized, with the expectation that they will work closely together day in, day out. It does not always go wrong, but when it does, the scope for it to go seriously wrong for the curate should be of considerable concern to the Church.

Prior to the research cited below, no quantitative study had been undertaken with curates or training incumbents to identify how often relationships break down and what the underlying factors might be. Conversely, the Church’s understanding of what might make for a good training incumbent and successful training outcome is reliant on instinct and anecdote. Even if those instincts are largely reliable, when a curate is difficult to place, the temptation to ignore warning bells and place vulnerable learners in an unsuitable setting just because there is an available house or a willing trainer, may not be easily resisted. Solid research is a corrective that ensures that the instincts of the bishop or diocesan director of ordinands are not given more weight than they can reasonably carry.

It is also of some importance to distinguish what factors may assist in predicting the probability of a successful training relationship in advance in contrast to those factors that may be addressed through training. Training incumbents can be trained in the use of supervision skills, stress management and even theological reflection. But their sex, age, church tradition and psychological type are givens. The Church may need to discover how these factors play themselves out in the training setting. In the same way, as the Church evolves to minister in a rapidly changing world, it needs to understand whether the best training incumbents are those with highly developed skills in areas such as mission or providing online worship or those who possess other innate qualities.

Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework for the present empirical enquiry has been shaped by three fields drawing on sociological, psychological and theological theories.

Sociological theory draws attention to two core personal characteristics that have played an established part in the early science of clergy studies.Footnote 6 Historically a male preserve, priesthood was opened to women in the Church of England in 1994.Footnote 7 Twenty-five years later roughly equal numbers of men and women are being ordained, although overall there still remain significantly more male priests than female priests. This is reflected and indeed exaggerated in there being many more male training incumbents than female training incumbents. The second core characteristic, age, notes considerable diversity in age among both training incumbents and curates. Both sociological categories of age and sex may be worth taking into consideration in exploring the performance of training incumbents.

Within the field of psychology, personality psychology in general and Jungian psychological type theory in particular,Footnote 8 have begun to play an important part in the developing science of clergy studiesFootnote 9 and in the developing science of congregation studies.Footnote 10 The basic building blocks of psychological type theory distinguish between two orientations (extraversion and introversion), two perceiving functions (sensing and intuition), two judging functions (thinking and feeling), and two attitudes toward the outer world (judging and perceiving).

The two orientations are concerned with where energy is drawn from; energy can be gathered either from the outside world or from the inner world. Extraverts (E) are orientated toward the outside world; they are energized by the events and people around them. They prefer to act in a situation rather than reflect on it. They may vocalize a problem or an idea, rather than think it through privately. They may be drained by silence and solitude. In contrast, introverts (I) are orientated toward their inner world; they are energized by their inner ideas and concepts. They may feel drained by events and people around them. They prefer to reflect on a situation rather than act in it. They enjoy solitude, silence and contemplation.

The two perceiving functions are concerned with the way in which people receive and process information; this can be done through use of sensing or through use of intuition. Sensing types (S) tend to focus on specific details, rather than the overall picture. They are concerned with the actual, the real and the practical and tend to be down-to-earth and matter-of-fact. They are frequently fond of the traditional and conventional. In contrast, intuitive types (N) focus on the possibilities of a situation, perceiving meanings and relationships. They focus on the overall picture, rather than specific facts and data. They follow their inspirations enthusiastically, but not always realistically. They often aspire to bring innovative change to established conventions.

The two judging functions are concerned with the way in which people make decisions and judgements. Thinking types (T) make judgements based on objective, impersonal logic. They value integrity and justice. They are known for their truthfulness and for their desire for fairness. They consider conforming to principles to be of more importance than cultivating harmony. They may consider it to be more important to be honest and correct than to be tactful. In contrast, feeling types (F) make judgements based on subjective, personal values. They value compassion and mercy. They are known for their tactfulness and for their desire for peace. They are more concerned to promote harmony, than to adhere to abstract principles. They are able to take into account other people’s feelings and values in decision-making and problem-solving, ensuring they reach a solution that satisfies everyone.

The two attitudes towards the outside world are concerned with the way in which people respond to the world around them, either by imposing structure and order on that world or by remaining open and adaptable to the world around them. Judging types (J) have a planned, orderly approach to life. They enjoy routine and established patterns. They may find it difficult to deal with unexpected disruptions of their plans. They prefer to make decisions quickly and to stick to their conclusions once made. In contrast, perceiving types (P) have a flexible, open-ended approach to life. They enjoy change and spontaneity. They prefer to leave projects open in order to adapt and improve them. They may find plans and schedules restrictive. Indeed, they may consider last minute pressure to be a necessary motivation in order to complete projects. They are often good at dealing with the unexpected.

Alongside psychological type theory, the science of clergy studies has also drawn on other recognized models of personality, including the Sixteen Personality Factors proposed by Cattell, Cattell and Cattell,Footnote 11 the Three Major Dimensions of Personality proposed by Eysenck and Eysenck,Footnote 12 and the Big Five Factor Model of Personality proposed by Costa and McCrea.Footnote 13 All three of these models of personality agree on including a higher order factor of emotionality or neuroticism, a dimension not embraced by measures of Jungian psychological type theory, but one which can helpfully complement psychological type theory as a predictor of individual differences in clergy behaviour and well-being.Footnote 14

All four components of psychological type theory and emotionality may be worth taking into account in exploring the performance of training incumbents.

Within the field of empirical theology, church orientation (or churchmanship) has begun to play an important part in the developing science of clergy studies. The Church of England has produced a number of distinct groups that owe their origins to religious revivals and reforms since the early nineteenth century. The most obvious of these are the Anglo-Catholic and Evangelical wings, which interact with other identities shaped by traditionalism, liberalism and charismaticism. The result is a rich mix of ecclesiologies existing within a single Church.

Anglican evangelicalism began with the revivals of the eighteenth century,Footnote 15 especially those associated with George Whitefield and the Wesleys.Footnote 16 BebbingtonFootnote 17 identified the core marks of Evangelical religion in England as ‘conversionism’, the belief that lives must be changed, ‘activism’, the idea that the gospel must be expressed in action, ‘biblicism’, a particular regard for the centrality and authority of Scripture, and ‘crucicentrism’, a stress on the work of Christ on the cross. Anglican Evangelicals share these core beliefs, but also have an identity shaped by their particular struggle to keep the Church of England close to its Reformed roots. Although Evangelicals were a minority in the Church of England during the early part of the twentieth century, the Evangelical wing currently has a central role within the Church of England,Footnote 18 and currently also embraces growing diversity.Footnote 19 There seem to be an increasing number of Evangelical clergy who may be relatively conservative theologically, but more socially liberal.

The Anglo-Catholic movement in the Church of England can be traced to a small group of Oxford clerics, who in 1833 began publishing tracts that denounced the growing liberalism and Utilitarian politics of the time.Footnote 20 They promoted church order, sacraments and dogmatics in ways that sought to move the Church back to its Roman Catholic roots. The movement clashed with Evangelicalism, because it seemed to be trying to undo the Reformation and introduce Roman Catholic ritual. The heyday of the Anglo-Catholic movement was in the years after the First World War, but it remains a significant minority within the Church of England.

These groupings within the Church of England are by no means uniform, and have been influenced by movements such as liberalism and charismaticism. Liberalism in the Church of England is often traced to Charles GoreFootnote 21 and the collection of essays Lux Mundi, which tried to help the Church embrace the emerging disciplines of biblical scholarship and natural science. Although Gore was a High Churchman, his Liberal Catholic approach was in sharp contrast to the Anglo-Catholics of his time, and he resented the adoption of conservative thinking and Roman practices.Footnote 22 Despite his views, liberalism in the Church of England has tended to be associated with Anglo-Catholicism more than any other tradition. The Charismatic Movement, on the other hand, was most enthusiastically adopted by Evangelicals during the latter part of the twentieth century,Footnote 23 and today it is mainly but not exclusively associated with those who inhabit that wing of the Church.

An empirical approach to ecclesiology within the Church of England is one that seeks to investigate beliefs, attitudes and practices of people who self-identify with particular church orientations. In terms of empirical investigation, for example, a series of recent studies has examined the power of church orientations to predict individual differences in the beliefs, practices and attitudes of Anglican clergy and lay people in England.Footnote 24 These studies demonstrate the predictive power of church orientations across a range of issues to do with religious belief, with moral values and with church practice. These components of church orientation may be worth taking into account in exploring the performance of training incumbents.

Research Aims

Against this background the present study set out to address two core research questions. The first research question was concerned to identify characteristics of curates’ experiences that could provide an operational definition of what characterizes a good curacy, and then to construct and to establish the psychometric properties of a reliable measure of curates’ attitude toward their training incumbent.

The second research question was concerned to identify the extent to which curates’ attitudes toward their training experience and toward their training incumbent may systematically vary according to personal, psychological or religious characteristics of the curate, or according to personal, psychological or religious characteristics of the training incumbent.

In shaping this second research question, attention was placed on two personal factors (sex and age), two psychological factors (the four components of psychological type theory and emotionality) and three religious factors (Catholic-Evangelical, Liberal-Conservative, and Charismatic-non-Charismatic). Each of these three areas engage significant wider literatures.

Method

Procedure

On two successive years (2009, 2010) questionnaires were sent to all curates serving within the mainland dioceses of the Church of England in the year after they had been ordained to the priesthood. At the same time, a complementary questionnaire was sent to the training incumbent with whom the curates were working. The participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity and that no personal information would be stored. Each questionnaire was numbered so that the responses of curates and their training incumbents could be linked. All told, 1004 surveys were mailed to curates and 592 responses were received, making a response rate of 59%. All told, 1004 surveys were mailed to training incumbents and 457 responses were received, making a response rate of 46%. In 416 cases completed questionnaires were returned by both the curate and the training incumbent. It is on these 416 paired responses that the present research questions can be addressed.

Instrument

Personal factors of curates and training incumbents were assessed by two fixed choice questions. Sex was coded: male (1), female (2). Age was coded: under 30 (1), 30–39 (2), 40–49 (3), 50-59 (4), 60 and over (5).

Psychological factors of curates and training incumbents were assessed by the Francis Psychological Type and Emotional Temperament Scales (FPTETS). This 50-item instrument comprises the four sets of ten forced-choice items proposed by the Francis Psychological Type Scales (FPTS)Footnote 25 related to each of the four components of psychological type theory: orientation (extraversion or introversion), perceiving process (sensing or intuition), judging process (thinking or feeling), and attitude toward the outer world (judging or perceiving). Recent studies have demonstrated this instrument to function well among clergy. For example, Francis and VillageFootnote 26 reported alpha coefficients of .84 for the EI scale, .74 for the SN scale, .68 for the TF scale, and .74 for the JP scale. Additionally, the FPTETS contains a fifth set of ten forced-choice items designed to assess emotionality.

Religious factors of curates and training incumbents were assessed by the set of three seven-point semantic grids developed from RandallFootnote 27 designed to assess church orientation (anchored by the poles of Catholic and Evangelical), theological orientation (anchored by the poles of Liberal and Conservative) and influence by the Charismatic movement (anchored by the poles of positivity and negativity).

Curates’ evaluation of their training incumbent was assessed by a series of items rated on a five-point Likert scale: disagree strongly (1), disagree (2), not certain (3), agree (4), and agree strongly (5).

Participants

Among the curates, the 416 participants comprised 201 men, 209 women and 6 of undisclosed sex; 14 were under the age of 30, 92 in their thirties, 106 in their forties, 124 in their fifties, 75 aged 60 and over, and 5 of undisclosed age. Among the training incumbents, the 416 participants comprised 326 men, 85 women and 5 of undisclosed sex; 12 were in their thirties, 93 in their forties, 217 in their fifties, 89 aged 60 or over, and 5 of undisclosed age.

Analysis

Analysis was undertaken using the SPSS statistical package, employing the correlation, factor, reliability, and regression routines.

Results

Religious Profile

The first step in data analysis explored the religious profile of curates and training incumbents as recorded on the three seven-point semantic differential grids. In Table 1 these data are presented by collapsing scores 1 and 2 into the first category, scores 3, 4 and 5 into the second category, and scores 6 and 7 into the third category. By these criteria, 22% of the curates and 27% of the training incumbents are classified as Catholic; 30% of the curates and 38% of the training incumbents are classified as Evangelical; and 48% of the curates and 36% of the training incumbents are classified as occupying the middle territory. In other words, there are significantly more Evangelicals among training incumbents than among curates (χ2 = 5.69, p < .05). By these criteria, 31% of the curates and 33% of the training incumbents are classified as Liberal; 18% of the curates and 21% of the training incumbents are classified as conservative; and 51% of the curates and 46% of the training incumbents are classified as occupying the middle territory. In other words, theological orientation is significantly more defined among training incumbents than among curates (χ2 = 6.38, p < .05). By these criteria, 31% of the curates and 38% of the training incumbents are classified as positively influenced by the Charismatic movement; 12% of the curates and 9% of the training incumbents are classified as negatively influenced by the Charismatic movement; and 57% of the curates and 53% of the training incumbents occupy the middle territory. In other words, the Charismatic movement has positively influenced a significantly higher proportion of the training incumbents than curates (χ2 = 4.63, p < .05).

Table 1. Religious factors

Note: TIs = training incumbents.

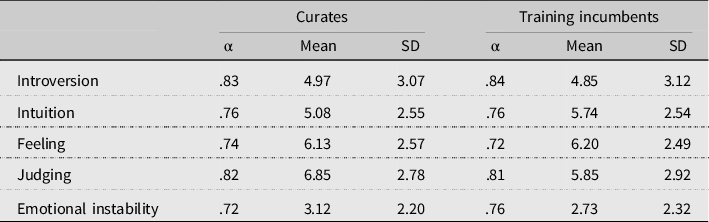

Psychological Profile

The second step in data analysis turned attention to the psychological profile of curates and training incumbents as assessed by the Francis Psychological Type and Emotional Temperament Scales. Table 2 presents the psychometric properties of the five component scales of this instrument that are subsequently employed in the correlational analysis and the regression models, for curates and for training incumbents separately, in terms of the alpha coefficient,Footnote 28 the means and standard deviations. These data confirm that all five scales recorded satisfactory levels of internal consistency reliability among both samples.

Table 2. Psychological factors

Table 3 draws on the data generated by the psychological type scales to produce and compare the psychological type and temperament preferences of the curates and training incumbents. The following features emerge from these data, employing the self-selection ratio (I) to test for the statistical significance of differences between the two groups.Footnote 29 There is no significant difference in the preferred orientation of the two groups: 45% of curates were classified as extraverts and so were 48% of training incumbents. There is no significant difference in the preferred judging function of the two groups: 61% of curates were classified as feeling types and so were 64% of training incumbents. The two groups differed significantly in their preferred perceiving function: while 59% of curates were classified as sensing types, the proportion fell to 44% among training incumbents, with the corollary that 56% of training incumbents were classified as intuitive types compared with 41% of curates. The two groups differed significantly in their preferred attitude toward the outer world: while only 17% of curates were classified as perceiving types, the proportion rose to 27% among training incumbents, with the corollary that 73% of training incumbents were classified as judging types, compared with 83% of curates.

Table 3. Psychological type and temperament preferences for curates and training incumbents

Note: TIs = training incumbents; I = self-selection ratio; NS = not significant.

These significant differences between curates and training incumbents in preferences in the perceiving functions and in the attitudes toward the outer world are reflected in a significant difference in the temperament profiles of the two groups. Among the curates there is a significantly higher proportion of the SJ temperament (54% compared with 41%) and a significantly lower proportion of the NF temperament (25% compared with 35%).

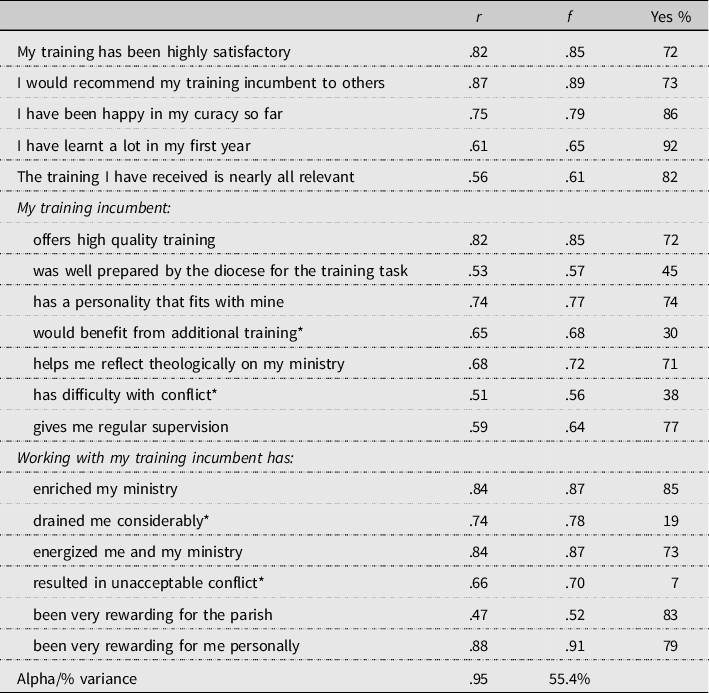

Evaluating the Curacy

The third step in data analysis involved exploring the items in the curates’ questionnaire in order to construct a scale of attitude toward the training incumbent. The relevant items in the survey that explored various aspects of the curates’ experience of working with their training incumbent were subjected to a series of exploratory factor analyses, resulting in the identification of one strong principal component of 18 items accounting for 55% of the variance. The scaling properties of these 18 items were then explored by the reliability routine, resulting in a highly satisfactory alpha coefficient of .95. The correlations between the individual items and the sum of the remaining 17 items were all above .50, indicating a high level of internal consistency reliability (see Table 4).

Table 4. Smith Attitude toward Training Incumbent Scale (SATIS): Scale properties

Notes: * These items were reverse coded to calculate the factor loadings and the correlation between individual items and the sum of the other 17 items.

r = correlation between individual item and sum of the other 17 items; f = factor loading.

The item endorsement suggests that, overall, the experience of their curacy and the experience of working with their training incumbents had been positive. For example, 92% felt that they had learnt a lot during their first year, 86% had been happy in their curacy so far, and 85% felt that working with their training incumbent had enriched their ministry. Nonetheless, the picture was not entirely positive and optimistic. Fewer than half of the curates felt that their training incumbent was well prepared by the diocese for the training task (45%) and 30% said that their training incumbent would benefit from additional training. One in five of the curates felt that working with their training incumbent had drained them considerably (19%), and 7% said that working with their training incumbent had resulted in unacceptable conflict.

Factors Related to Attitude toward Training Incumbent

In order to address the second research question, Table 5 presents the results of a sequence of eight regression models in which the potential effects of eight factors were introduced in the following fixed order: personal factors of curates (model 1), personal factors of training incumbents (model 2), psychological type of curates (model 3), personality of curates (model 4), psychological type of training incumbents (model 5), personality of training incumbents (model 6), religious factors relating to curates (model 7) and religious factors relating to training incumbents (model 8). In view of the sample size and number of predictor variables included, probability was set at the 1% level. From these models, the personal profiles of both curates and training incumbents are significant: a more positive attitude toward the training incumbent is associated with the curate being older and with the training incumbent being younger. The personality profile of the curates was significant, but not of the training incumbents: a more positive attitude toward the training incumbent is associated with the curate being emotionally stable. The psychological type profiles and the religious profiles of neither the curate nor the training incumbent were statistically significant predictors of attitude toward the training incumbent.

Table 5. Multiple regressions

Note: ** p < .01; *** p < .001

Discussion and Conclusion

This study set out to address two core research questions. The first research question was concerned to identify characteristics of the curates’ experience that could provide an operational definition of what characterizes a good curacy, and then to construct and to establish the psychometric properties of a reliable measure of curates’ attitude toward their training incumbent. In response to this research question, the study has developed and tested the new instrument that we style the Smith Attitude toward Training Incumbents Scale (SATIS). Three conclusions arise from the new data addressing this first research question.

The first conclusion is that the SATIS has been shown to work with a high level of internal consistency reliability according the alpha coefficient of .95 (Cronbach, 1951) and each of the 18 items has been shown to contribute to the homogeneity of the construct assessed (high correlations between each individual item and the sum of the other 17 items). The items selected to comprise this measure from a wider bank of items all have good face validity. On these grounds the SATIS can be commended for application in further studies.

The second conclusion is that close examination of the 18 individual items helps to construct a picture of the characteristics of the training experience and of the training incumbent that curates value most highly in forming a positive evaluation of their training incumbent. The six items that correlated above .80 with the sum of the remaining 17 items help to define the features that stand at the heart of a positive evaluation of the training incumbent. Of such training incumbents the curates say:

-

working with my training incumbent has been very rewarding for me personally (.88);

-

I would recommend my training incumbent to others (.87);

-

working with my training incumbent has enriched my ministry (.84);

-

working with my training incumbent has energized me and my ministry (.84);

-

my training incumbent offers high quality training (.82);

-

my training has been highly satisfactory (.82).

Around this core of items, for a successful curacy, curates feel that they benefit from working with a training incumbent who has a personality that fits with theirs, and who has been well prepared for the training task by the diocese. They value regular supervision and being helped to reflect theologically on their ministry. They like to feel that they are learning through the relationship with their training incumbent, and that the training they have received is really relevant for their ministry. Curates are also concerned that the training experience should be rewarding for the parish as well as for them personally. The warning signs that things are not going well include feeling that working with the training incumbent is draining them considerably, that working with the training incumbent has resulted in unacceptable conflict, and that the training incumbent has difficulty dealing with conflict.

The third conclusion draws on the percentage endorsements of the 18 items to provide an overall assessment of the health of the relationship between curates and training incumbents. These item endorsements suggest that, overall, the experience of their curacy and the experience of working with their training incumbent had been positive for the majority of curates. For example, 92% felt that they had learnt a lot during their first year, 86% had been happy in their curacy so far, and 85% felt that working with their training incumbent had enriched their ministry. Nonetheless, the picture was not entirely positive and optimistic. Fewer than half the curates felt that their training incumbent had been well prepared by the diocese for the training task (45%) and 30% said that their training incumbent would benefit from additional training. One in five of the curates felt that working with their training incumbent had drained them considerably (19%) and 7% said that working with their training incumbent had resulted in unacceptable conflict. These levels of exhaustion and of unacceptable conflict have to be read against the information that by the time the questionnaire was sent out some training relationships may have already broken down.

The second research question was concerned to identify the extent to which curates’ attitudes toward their training experience and toward their training incumbent may systematically vary according to personal, psychological or religious characteristics of the curate or according to personal, psychological or religious characteristics of the training incumbent. In sharpening this second research question, attention was placed on two personal factors (sex and age), two psychological factors (the four components of the psychological type theory and emotionality) and three religious factors (Catholic-Evangelical, Liberal-Conservative and Charismatic-non-Charismatic). In response to this research question, the study has developed a series of regression models that demonstrated that the most satisfactory experience of curacy was associated with older, emotionally stable curates working with younger training incumbents. Five conclusions arise from the new data addressing this second research question.

The first conclusion is that older curates report a more favourable attitude toward their training incumbent compared with younger curates. With the current attention given by the Church of England to attracting a greater number of young vocations, further research may need to be invested in exploring the distinctive needs and expectations of younger curates.

The second conclusion is that the emotional stability of curates is a significant factor in shaping attitude toward their training incumbent. More emotionally labile curates are prone to experience their curacy in less favourable terms. This finding is consistent with the broader research on the personal and social correlates of individuals scoring high on measures of emotionality and neuroticism. Further research may need to be invested in exploring how better to equip training incumbents to deal effectively and creatively with curates across the spectrum of normal individual differences in levels of emotionality.

The third conclusion is that younger training incumbents are rated more highly than older training incumbents. This finding may be related to a range of factors, including perhaps the tendency of some dioceses to re-employ training incumbents whom they have previously used without a robust system of evaluation or appraisal; the tendency for workloads and responsibilities to increase with age, leaving less time for the supervision of curates; a failure to understand that what worked well with one curate may not work so well with another; and the tendency for personal levels of energy and vision to decline with age. Further research may need to be invested in exploring how better to resource older clergy for fulfilling the role of training incumbent; and reviewing the appropriateness of repeatedly using the same training incumbents without conducting an evaluation.

The fourth conclusion is that female training incumbents and male training incumbents were rated equally, and that female curates and male curates rated equal levels of satisfaction with their experience of training. This non-significant finding is important because it challenges any assertions that either clergymen or clergywomen may provide a better training experience for curates. It also challenges any assertions that either female curates or male curates may be easier to please within the context of their experience of training.

The fifth conclusion is that neither the psychological type profile of curates nor the psychological type profile of training incumbents predicted significant difference in the curates’ attitudes toward their training incumbent. This non-significant finding is important because it challenges any assertions that some psychological types may be better equipped than others to serve as training incumbents. It also challenges any assertion that some psychological types may be better predisposed than others to respond positively to the experience of serving as curates under the supervision of a training incumbent.

The present study represents the first systematic attempt to employ quantitative research techniques to model and to measure curates’ evaluation of their experience of training and their experience of their training incumbent. The limitations with the present study include the sample size (restricted to 416 pairs of curates and training incumbents who participated in the survey), the generation in which the research was conducted (restricted to two cohorts of curates ordained deacon in 2009 and in 2010), the failure to distinguish between the experiences of curates serving in stipendiary and self-supporting capacities, and the failure to follow up on the curates’ evaluation of their experience of training and their experience of their training incumbent after the completion of their curacy. The findings may, nonetheless, be sufficiently intriguing and useful to deserve further replication and extension.

In building on this initial study, there would be value in designing a project that surveyed both curates and training incumbents during the year after priesting over four consecutive years (compared with the two consecutive years employed in the present study). This would generate sufficient data to allow detailed independent investigation of the experiences of curates serving in stipendiary and self-supporting capacities. There would be added value also in designing a follow-up survey among curates a year or more after the completion of their curacy.

Statistical Glossary

Quantitative studies of this nature are constructed on two core principles. The first principle concerns measurement by means of scales. To trust scales we need to know that the individual items comprising these scales work together in a consistent and coherent way. To test this we employ measures of reliability, like the alpha coefficient (α). The second principle concerns testing associations between measures. In the present study the association between two variables is expressed by the correlation coefficient (r), and the cumulative association between a set of predictor variables and the dependent variable (the variable that we are interested in explaining) is expressed by multiple regression and beta weights (B). The scientific aim of such statistics is to test the strength of the association against what we could anticipate happening by chance. This is expressed as the probability level (p <). Convention expresses three probability levels where an association could have occurred by chance five times in a hundred (*), once in a hundred (**), or once in a thousand times (***).