In 1992, a storyteller riffed on a famous incident from the old Chinese story cycle and novel Water Margin (Shuihu zhuan 水滸傳).Footnote 1 One of the outlaw heroes, Wu Song, dedicated equally to drink and to good works, had become extremely drunk. When someone warned him that a tiger was eating people along the road he had to travel, he laughed it off.

Our hero hurried ahead, taking advantage of the moonlight. He discovered something beside the road. When he took a closer look, he saw there was a Temple of Earth at the roadside, and on the eastern gable a snow-white thing was hanging. What was it? At this moment our hero was stepping up in front of the Temple of Earth, and availing himself of the moonlight, he fixed his eyes on it. Oh, it turned out to be a proclamation from the local authorities. How could he know? Because a notice had been put up, and at the bottom it was stamped with a neat square seal of the local authorities. As for the characters on the proclamation, Wu Song was even able to recognize some of them too. Although Wu Song had never been to school, he had studied a bit on his own, memorizing and asking meanings. Skimming through this from the beginning to the end, he couldn't fail to notice a sentence like “A tiger obstructs the road.”Footnote 2

The story-teller then recites the whole poster, from the titles of the authorities posting the notice in the first line through the concluding date and place of posting. Wu Song himself could read just enough of the notice to understand that the authorities were warning of a tiger in the area obstructing the road. This written warning he believed, and he berated himself for his foolhardiness in rejecting the earlier oral one.Footnote 3

The anecdote suggests that the language and ideology of government were familiar to the many people living under the Ming dynasty who like the fictional Wu Song had begun but not finished their studies. Posted, inscribed, and printed messages from the state included not only the idea that subalterns should respect and obey their seniors and betters, but also the ancient ideal that Confucian governance meant serving subjects by preserving their lives and livelihoods in accordance with the advice of the wise. One genre of texts in which state service appears more salient than the obedience of subjects is stone inscriptions commemorating premortem shrines. Composed by elite literati, the steles not only publicized the duty of good magistrates and prefects to work for the people, but also legitimated the locals, including commoners, passing judgment on officials—a kind of popular participation in politics.Footnote 4 The central question of this article is whether people less literate than the highly educated gentry authors could have seen those two political messages in the steles.

It is notoriously difficult, if not impossible, to know what the “common reader” thought. This article will describe a digital humanities tool that may take us one small step closer to understanding what that “common reader” could understand from elite texts. In addition to praising the sponsors of the project and those honored by it, essays engraved as steles used a style designed to demonstrate to other gentrymen the erudition and compositional skill of the writer. They display an elegant structure or bristle with allusions and esoteric words. The Late Imperial Primer Literacy Sieve strips the essays of vocabulary that a partially literate reader would not have understood, allowing the historian to think about what messages would come across.

I will first briefly introduce late imperial primer literacy and the primers themselves, scholarly views of the relation of literacy to elite dominance, and the facts about Ming premortem shrines and steles. I will then explain how the Late Imperial Primer Literacy Sieve works, inviting use by other scholars.Footnote 5 Next comes an analysis of three premortem texts using the Sieve, followed by consideration of weaknesses and complications in using the Sieve for this kind of work. I conclude that the complications are not fatal. The tool can be useful, and the message I was testing for could indeed have reached the partially literate Ming reader.

Primer Literacy in Late Imperial China

In Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) times only a tiny percentage of the population was fully classically literate, able to read and write elegant classical-Chinese prose and poetry full of complex illusions and antiquated vocabulary. Yet as Craig Clunas has documented in loving detail, “Ming streets were noisy with text,”—text permanent and fleeting, giving a voice to authorities and to rebels, to seekers and to sellers.Footnote 6 The civil service examinations’ openness, in theory, to men of almost any family background, and the vibrant commercial economy, led many Ming families to pursue elementary education. A reader might know only enough characters to keep accounts, show a travel permit, or pick up a basket of food in prison; perhaps he could enjoy and learn from the vernacular fiction, almanacs, instruction manuals, encyclopedias, joke books, and simplified versions of Zhu Xi's Family Rituals that were published in such abundance; perhaps he could struggle through more difficult literary texts.Footnote 7 Since the Ming state routinely communicated with the population through printed sources, as in the story of Wu Song and the tiger, the public must have included a number of people who could read aloud the important points to neighbors; Clunas comments that one extant printed decree from 1422 was designed to be “easily readable by a crowd at a distance.”Footnote 8

Scholars have reached no firm conclusions on the number of literate Ming people, partly because one cannot draw a clear line between the literate and the illiterate. The path to education was roughly the same for all, only some abandoned it earlier, with a primer or two under their belts, while others continued on to learn the Four Books, Five Classics, and histories required for the civil service examinations. Wilt Idema distinguishes the “highly literate” few who actually read widely, from the “fully literate” who read only to study the examination curriculum, and from the “moderately literate,” who could more or less understand a simple book; he estimates that together these readers made up 10 percent of the male population.Footnote 9 Yuming He, writing of the numerous ways the Ming public interacted with books, prefers “a looser and broader notion of conversancy with the printed page that encompasses both high-level scholarly mastery of ancient and modern texts and various sorts of ‘knowing what to do with books’ that might or might not include full reading mastery.”Footnote 10 Benjamin Elman has offered the concept of “primer literacy.” The term makes sense because most scholars agree that five texts predominated in Ming and Qing primary education: The Hundred Surnames (Bai jia xing 百家姓), The Trimetrical Classic (San zi jing 三字經), The Thousand Character Essay (Qian zi wen 千字文), The Classic of Filial Piety (Xiao jing 孝經), and Zhu Xi's Elementary Learning (Xiao xue 小學).Footnote 11

The Trimetrical Character Classic, Thousand Character Essay, and Hundred Surnames form a group, sometimes referred to as Three-Hundred-Thousand. Used by “almost all families and local schools,” in Elman's words, together they taught 1,496 characters.Footnote 12 Either writing or aural/oral memorization may have come first, given the rhymed structure.Footnote 13The Hundred Surnames lists about 500 single- and double-syllable Chinese surnames, arranged in verses of four lines of four characters each, rhyming abcb. The Thousand Character Essay introduces the cosmos, the basics of history, and Confucian morality. No character repeats in its four-character lines, an effect achieved by stripping to naught the already barebones grammar of classical Chinese; the four-line stanzas usually rhyme abcb.

The Trimetrical Classic (or Three-Character Classic) consists of lines of three characters each, in stanzas usually of four lines. It opens with the fundamental Confucian credo that “People at their start/have natures originally good./ By nature they are close;/they diverge through habits.”Footnote 14 After a lecture on the importance of learning, the text covers basic moral and practical knowledge, matching the “three bonds” of moral obligation (righteousness between ruler and minister, closeness between parent and child, husband and wife getting along) with the Three Luminaries of Sun, Moon, and Stars, for instance; and the Five Elements with Five Virtues. It lists grains, animals, objects, and important books and thinkers. It runs through all of history dynasty by dynasty, introduces exemplars who studied hard (including two girls, to shame boys into better habits), and then concludes with exhortations to study.

The Classic of Filial Piety and Elementary Learning are more sophisticated texts that nevertheless were sometimes used as primers, as Ming and Qing objections to that practice demonstrate.Footnote 15 Ming educators also used other texts for elementary education, but these were the common ones (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 An encyclopedia section that might have been used to teach basic literacy shows a mother leading a new pupil to bow to the teacher. 1612 Wanbao quanshu.

Literacy, Domination, and Liberation

Globally, literacy has been promoted and theorized as a means of both domination and liberation.Footnote 16 With the exception of The Hundred Surnames, the five primers may fairly be called Confucian ideological works. Whether the new reader continued onto the civil service examination track, or into vernacular literature read for pleasure and professional texts read for knowledge, the primers and their teachers, often government students, would have reinforced Confucian ideals common in oral tales, pictures, family practice, and so on.

Some scholars have concluded that learning to read in Ming and Qing times basically legitimated elite dominance, shaping non-elite consciousness to accept state and ruling-class Confucian values of hierarchy and obedience.Footnote 17 Limin Bai's main explicit argument fully agrees with Benjamin Elman and David Johnson that late-imperial education for both gentry children and farm or urban commoner children was part and parcel of the domination of the ruling class, legitimated by classical education. Johnson argues that the examinations and the “official culture” they promulgated among the ambitious so effectively shaped “popular consciousness” as to make ordinary people “become willing participants in their own subjection.”Footnote 18 Not mere word-books or stories of exemplars for children, the primers of late imperial times were Neo-Confucian ideological texts; and they were aimed not merely at elite children, but perhaps even more at the potentially dangerous children of farmers, who were unlikely to be civilized at home.Footnote 19 In this view, elementary education was intended to, and did, strengthen ruling-class domination.

Certainly, the primers taught Confucian ethics along with basic elements of knowledge about the world. But there are objections to the view that education merely reinforced domination. First, as J.P. Park points out following Roger Chartier's observation that publishers had to strategize about sales, the existence of a wide variety of books suggests that no one segment of Ming society wholly dominated publishing decisions. It is hard to see how books of the kind Park discusses—like one that promised that “when readers open this book, the sentiments of people, the principles of nature, cities and wilderness, victory or defeat, poverty or prosperity, the capital city or the rural inn are completely available at a glance”—could be sending a simple, top-down message that led to meek accession in elite domination, even to those who spent their days reading while working a treadmill. Park cites Bourdieu to note that “although the reading public may accept generally the leadership of the dominant group, arguably this is because they have reasons of their own for doing so, not because they are ideologically subordinate or indoctrinated.”Footnote 20

Second, even if all texts promoted Confucian values, those values included far more than mindless obedience. They included responsibilities of the senior party in each relation and remonstrance by the junior party if the senior party was wrong. Confucianism also stressed the primacy of popular lives and livelihoods amongst the ruler's and gentleman's concerns, and put representations of the commoners front and center in representations of the polity.Footnote 21 Within the Mandate of Heaven ideology, the dynasty's legitimacy hinged on its assuring the people's security, along with carrying out rituals to keep the cosmos humming along and heeding the words of the wise—who would advise the ruler not only on his personal uprightness but also on how to govern. The responsibility of the government for the people, and the people's talking back when superiors were wrong, were also Confucian values in Ming times.

Finally, a real or fabricated popular voice could be heard alongside imperial and elite voices in Ming texts. As many scholars have pointed out, some Ming literati valorized an alternate, popular, voice as expressed in folksongs and imitated in elite-authored vernacular literature.Footnote 22 The popular voice could be adopted to express and focus on elite men's own sense of responsibility for, or self-representation as responsible for, the popular livelihood.Footnote 23 Cynthia Brokaw writes that even though primers taught ruling-class values, other kinds of books, like short stories, songbooks, plays, and manuals for telling fortunes, “satirized the existing power structure and celebrated heroes and heroines who regularly violated orthodox norms” even as they simultaneously lent support to “orthodox morality.”Footnote 24

The question of whether primer literacy in Ming times meant only more effective elite domination or some degree of subaltern liberation or empowerment, therefore, is still open.

Premortem Shrines and Steles

One particular type of text that might teach more than subservience was the focus of my interest when my team developed the Late Imperial Primer Literacy Sieve. Shrines to living men could flatter the powerful, but the legal and normative living shrine or premortem shrine of Ming times honored a departing county or prefectural official and was sponsored by local residents, especially commoners (those without rank or gentry status), to express Confucian ideals of gratitude and reciprocity for his good government.

The paradigm meant that locals, not the emperor or his central bureaucracy, were deciding which officials deserved gratitude, which did not, and why, and were announcing those decisions in public. The genre of premortem steles licensed local people, including commoners, within the autocratic, bureaucratic Ming monarchical system, not only to laud officials for specific local policies, but also to criticize the policies and behavior of earlier officials who were sometimes also still alive; it provided opportunities to put quite explicit pressure on current officials in the area and even to support those who were out of favor with the court and lodge protests against central policies.

Like me, literati at the time may mainly have read steles transcribed into print, and some steles were awkwardly placed for reading. But others were perfectly legible, and Ming writers described the purpose of steles as remembrance over generations, beyond what the “oral steles” of local knowledge could assure: remembrance of the honoree's contributions and virtues. If a primer-literate visitor to a living shrine, or someone passing by such a shrine, tried to read a stele, how much would he have understood?

The Problem of Reception

How can we know how specific texts were read? Scholars studying the vernacular literature and other texts of the Ming and Qing have no systematic way to ascertain which texts the primer-literate could read or how well they could understand them. Anne McLaren has pointed out that it is quite impossible to know how most readers read texts. She writes that Japanese scholarship on the major Ming novels has associated them with specific readerships from an elite and/or wealthy stratum to a middling group of government students, village schoolteachers, and merchants. But we must postulate a variety of readerships, not only because the novels appeared in multiple forms from elaborate to simple, but also because “reading practices”—different (mis)understandings of literary conventions—coexisted and changed over time.Footnote 25

To approach the problem, McLaren offers a very careful analysis of one fictional character's account of his reading of a known episode from the Sanguo zhi tradition, concluding that the fictional reader accepted the guidance of the commentary and proverbs included in the edition he read to reach an interpretation that differs from the standard literati interpretation of the story. She then presents how publisher Yu Xiangdou repackaged Sanguo zhi as a manual of military and life strategy. Two clues point to a less-elite audience: discussion of how poor commoners evade corvée demands by contracting with elite households for protection; and a demonstration of how virtuous elite men can win people's hearts.Footnote 26

With all her wide and careful reading, even McLaren has not found a way to determine the audience from the text, or to see how the audience understood the text. Both are basically impossible tasks. Yet they are so important to history that responsible speculation is better than nothing at all.

The Late Imperial Primer Literacy Sieve

We can take one speculative step towards understanding how the primer-literate might have read complex texts. Together with computer programmer Joshua Day and historian Jenny Huangfu Day, I created a digital tool called “The Late Imperial Primer Literacy Sieve.”Footnote 27 The Sieve eliminates from the stele whatever Chinese characters do not appear in one or more primers. The researcher can then “read” what remains. The Sieve has three elements:

First, the primers. Built into the Sieve are the basic primers discussed above—the Trimetrical Classic, Hundred Surnames, Thousand Character Essay, Elementary Learning, and Classic of Filial Piety—as well as the Great Learning (Dai xue), required for the examinations, and two Buddhist texts (the Heart Sutra and the Guanyin Sutra) as a way to address female partial literacy. The researcher selects one or more of the primers, and can load in others.Footnote 28 We also added numbers and directions, because those were probably often taught.Footnote 29 Again, a researcher can add in specific Chinese characters, such as place names for a local study. Choosing these primers oversimplifies the Ming learning landscape, but it was my best guess for a manageable approach.

The second element in the Sieve is the target texts. These are the texts being studied: the texts about whose reception the researcher is curious. In my case, these are premortem essays. The process for loading target texts, if they are not already available in machine-readable form, is to scan them, convert them with optical character recognition (OCR) software to be machine-readable, and check the OCR'd version for accuracy.

The Sieve program runs the chosen primer(s) against the target text, and sifts out of that text any Chinese characters that do not occur in the selected primer(s). The result, or output, is the third element: the “depleted text.” Depending on the display mode chosen for the depleted text, characters in the target text that do not appear in the selected primers may be shown as red in black boxes or as grey and italicized, or they may be completely invisible.

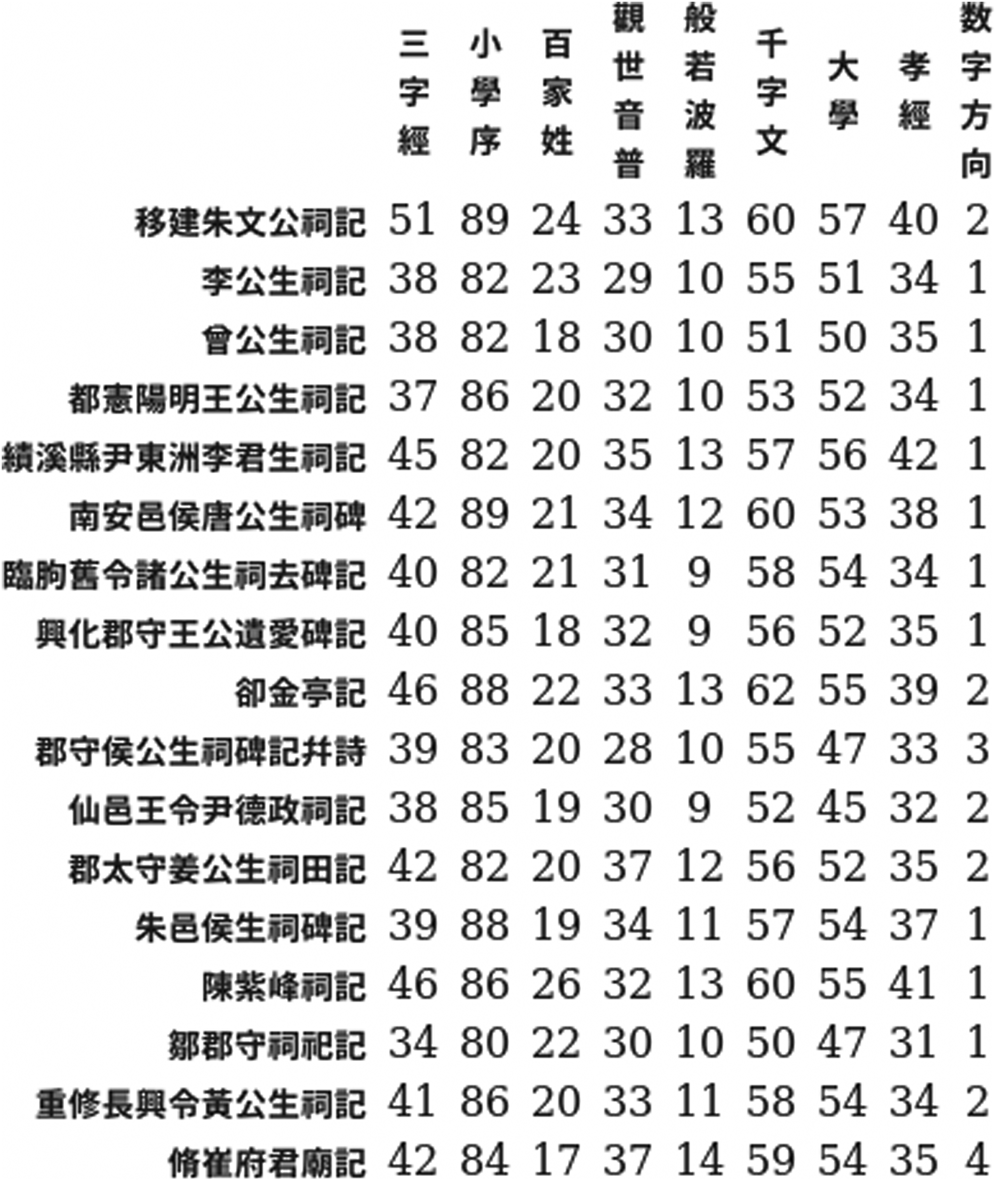

The Sieve has some statistical functions, and one unexpected general result of these was that the discovery that the percentage of readable characters based on knowledge of a particular primer was quite consistent across steles in the genre. Figure 2 presents the data for fifteen of the seventeen target texts we ran, and Table 1 summarizes the results. If one had memorized only The Hundred Surnames, one could recognize about one-fifth of the characters in a premortem stele; if one had memorized The Classic of Filial Piety, one could recognize about one-third; if The Trimetrical Classic, over one-third; if The Great Learning with Zhu Xi's commentary, about half; if The Thousand Character Essay, just over half; if The Elementary Learning, 80 percent or more. Moreover, as I will show below, in these cases enough characters are connected that one could put together meaning, in a sense reading the depleted text. Having memorized only the Heart Sutra, one could recognize only about one-tenth, and the words are not connected enough to make sense. That might not seem surprising, since the target texts in this case are very Confucian in their language and outlook. Nevertheless, with the Guanyin Sutra one could recognize about one-third of the characters, better than with the Hundred Surnames.

Figure 2 Percentage of target text in depleted text varying by primer. The titles of the primers run across the top; the titles of fifteen target steles run down the left.

Table 1. Rough Legibility Percentage with Knowledge of One Primer

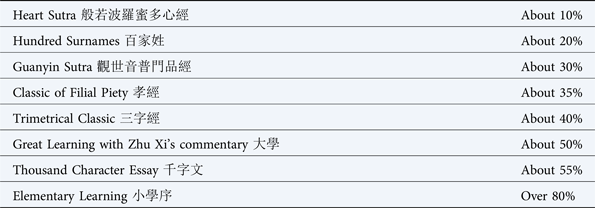

Other kinds of statistical questions could be explored using the Sieve. For instance, a preliminary look at how primers overlapped shows that a reader who could recognize characters from one primer was not particularly well able to read others. The highest percentage of transfer legibility was between the two Buddhist texts: a person who knew the (long) Guanyin Sutra could read 69 percent of the (short) Heart Sutra. For the standard primers, transfer legibility ranges from 16 percent to 67 percent. Someone who had learned the Classic of Filial Piety would recognize only about a fifth of the Hundred Surnames, and at the other extreme, a Thousand Character Essay reader would know two-thirds of the characters in the Classic of Filial Piety (see Table 2). The interpretation of these results and answers to other such questions await further research.

Table 2. Percentage of Legibility of One Primer (Vertical Axis) with Knowledge of Another (Horizontal Axis).

The statistics are intriguing, but my research question focused on the legibility of the message of my target texts. Out of the dizzying array of possible combinations of one or more primers with target texts, I decided to study how one primer interacted with one stele, by “reading” the depleted text. This creates a fourth element: a translation into English of an imaginary text created by an imaginary reader. Here, I offer three examples. In each case I first summarize the full target text and then give or summarize the depleted text, in three slightly different ways. The readings both demonstrate one way to use the Sieve and suggest an answer to my particular research question.

At One-Third Comprehension: Zhu Laiyuan in Jiaxing Prefecture

First, I will present a premortem shrine stele for Magistrate Zhu, at one-third comprehension through The Classic of Filial Piety (see Appendix A). The target text is Yao Hongmo's stele record for a shrine to an outgoing magistrate of his home county. It recounts that Zhu Laiyuan 朱來遠 had administered “our Xiushui” for six years. He was loved and respected by the clerks and people of the jurisdiction. When he was promoted to a central post and was about to leave, the elders first blocked the road and held the shafts of the carriage, begging him, with tears, not to leave—but in vain. (A ubiquitous trope.) Next, they sent a letter asking that he be promoted in rank and rewarded with money and kept in place to govern there for the long term; but this request was also denied. When both of these appeals had failed, the elders made an image of Zhu and made offerings to it on the west side of the city. The people came in such numbers with their hoes and spades to work on the shrine that their feet ground against one another, so the shrine was soon finished. The shrine being finished, a stele was only proper.

To go beyond these tropes and shape an elegant essay, Yao focused on Magistrate Zhu's native place. Yao writes that he himself has climbed Mount Lu and looked out over Lujiang; he has seen its broad views and harmonious customs, which naturally produce the kind of impartiality and benevolence that its native sons exhibit in office. Yao fills out his essay with two other Lujiang natives, both officials of Han times whose stories frequently appear in the genre as demonstrations of a deep connection with the people of a jurisdiction. First there was Wen Weng 文翁. He governed Sichuan, and when he died there the clerks and people set up a shrine to him and sacrificed at certain times of year in perpetuity. Second, Yao writes about Zhu Yi 朱邑, who had served as bailiff of a district called Tongxiang when he was young and asked his sons to bury him there. They did, and the offerings continued: until today, Yao writes.Footnote 30

Now, what would a reader who had learned only the Classic of Filial Piety understand from the essay? In the translation/reading below, words that I think the reader could reasonably interpolate are in italics. Where a group of characters could make sense together, even if it did not work out grammatically, I put those in brackets summarizing the idea. Illegible characters that the reader could interpret as a gap in an otherwise meaningful sentence are marked as … . I also assumed that the reader would know from the location that the stele was about the shrine. The imagined reading goes something like this:

Milord has commanded our Xiushui for 6 years. When he came did not have? know that by which. The commoners loved and respected him. In time, Milord because his governing behavior was lofty, was made … thought of him like a father and accompanied him along the road, tears falling. Milord. [Locals tried twice to retain him, but it was not permitted.] [Commoners cooperated to serve him and finished a shrine to the west of the city.] [Observing and teaching using texts to transform oneself to be fair.] To have virtuous yielding is the air of a gentleman thereby already. And he changes their customs in order to make the place better; thus his loving kindness is the Heavenly nature. Observing Milord his … as if he had something to hide in and retreat into. His behavior to others was sensitive, as if his own name were at stake. He is able to get from the small to the large. Therefore he carries it out and has fame. He does not respond to those who require him with their reasons. He has reasons of his own that are weighty, as each does.

There was one person who wrangled and would not submit to Milord. He responded to him saying: “Your reasons, what kind of reasons are they? I know the neighbors, which family among one hundred you are hiding something; do what you ought!” The person feared and submitted. The commoners greatly feared? admired? wondered?, not knowing by what means he knew. His divine discernment was like this! His governance treated commoners like children. At completion, it was a peaceful time.

As for his prohibitions: one day the commoners and people together told him about the criminal great clans, how they … He led and sent down orders to make the big families not dare to do their things in order to do wrong. He sternly prohibited so they could not do it. And Milord used harmony to make the name and the nature. Although they ought to help the poor they had not yet done so. He disgraced the rich ones according to the time and the poor ones together made requirements. Those who did not yet do what he required were made to … their feelings. Some are permissible, some were impermissible. Levelled them. Himself saying: “That by which the commoners survive is land. How can I use three feet of their property?”

After he had been Magistrate for 6 years, the people were all transformed by him. In the night there were no robbers or other scary things. Above, his governing behavior was number one in the whole empire. The Son of Heaven took Milord as the ultimate leader and made him serve in some other post. That the gentry and people thereupon made a shrine to make offerings to him was because they missed him.

This text about his governing the commoners set up at the shrine hall, at times making sacrifices and offerings and “North Sea” at the last said to his sons “You must … Later generations’ sons will not be as good as the commoners.” His sons accorded with his words. The commoners made a shrine. The shrine offerings until now are not stopped.

The saying says, “If you do not know the official look at his commoners.” Is this not about Milord? Thus, three people all from antiquity were leaders like this, no? But if we look at the generation's people, the gentry are not their equal? Inferior? Those not in office one and all have this culture therein, and thus those who use their endowment to be like Milord's cultivated behavior … Such are gentlemen. They will have glory in the world. Now, Milord's surname was …, he came from … as a native, Wanli year metropolitan degree-holder.

In this imagined and necessarily tentative reading, the imaginary primer-literate reader misses the whole focus of the essay on the place, Lujiang. The stories of Wen Weng and Zhu Yi, woven into Yao's essay in two separate places, also more or less dissolve. When the reader came to the end, and saw “Milord” followed by a character, he might go back and pick out that character as referring to Milord in other appearances, but it still would not be clear that the essay discussed three different men, since two share a surname. The stele would seem to be almost all about one person: the one whose image the reader could walk into the shrine and see.

What does the reader understand, overall? The emphasis is clearly on the unmediated relationship between the official and commoners. The commoners’ opinion of him, or more precisely their emotions about him, come even before the objective fact of his excellent governing. This is accurate to what Yao wrote, but the clerks, mentioned in the original because Yao is drawing on the Han History where this word for lower officials is normal in the context of sponsoring living shrines, drop out entirely. The elders—wealthy or literate or well-connected or respected commoners—also vanish. They turn into a reference to the very common “parental metaphor” used to refer to resident administrators (magistrates and prefects) as the father and mother of the people. Even the magistrate's recognition by the emperor comes in second to his recognition by local commoners themselves, and mainly has the effect of removing him from them against their will. When the petitions to retain the magistrate have been rejected, in the depleted version, the commoners are the only actors initially mentioned in the building of the shrine. They are working together, with no apparent direction from anyone else, although later the gentry do appear as shrine-builders.

In the depleted version, Milord exhibits loving kindness and exercises his own judgment. One obstreperous character was finally cowed by the magistrate's amazing understanding of circumstances, beyond what ordinary people know—and it was the commoners who bore witness to this. Part of his treating the commoners as his children involved effectively prohibiting gentry abuses. The wealthy appear to be taken to task, told that they ought to be helping others. Harmony appears as a result of this focus on charity, even levelling. The general message, therefore, is that the magistrate was good, largely because he was good to commoners, and had superhuman perspicacity. Commoners appreciated him, they expressed their views, and they set up a shrine to him on their own initiative.

This reading is particularly interesting in light of Ho Shu-yi's recent argument that shrines to the living in this prefecture in particular (Jiaxing, Zhejiang) served primarily gentry purposes.Footnote 31 The take-home message of this stele, therefore, went directly against the reality of gentry domination in this wealthy prefecture. Messages of empowerment should be noted, responding to the historiographical debate noted above, even if conditions of domination were such that they could not take practical effect.

At Forty Percent Comprehension: Zeng Xian in Liaodong

As well as resident administrators, living shrines commemorated scary generals at the beginning and end of the dynasty, those who fought pirates in the Jiajing period, palace eunuchs, and other high officials. In 1535, Zeng Xian 曾銑 (1499–1548, js. 1529), who had been Regional Inspector of Liaodong for about fifteen months, learned that soldiers in Liaoyang had mutinied against the governor of Liaodong, who was making their lives a misery and also harming ordinary civilians. James Geiss comments that the court simply could not get any good information as the situation developed.Footnote 32 Some officials favored dealing harshly with the soldiers, but Zeng tried to limit punishment to a few and to spare the civilians who had been caught up in the violence. He wrote emotional appeals to the Jiajing emperor, who himself felt torn about the best way to handle the affair.

Zeng Xian won the emperor over to his approach and Jiajing praised and promoted him. Three living shrines were set up to him in Liaodong (in Liaoyang, Ningyuan, and Qiantun), and several steles commemorated them. The emperor figures more prominently in these steles than in most, because of the situation. The three separate “Praising Loyalty Shrines” 嘉忠祠 got their name from the phrase “The emperor praised his loyalty,” which occurs in one of the steles (by Ye Yingcong); and as that name suggests, the emperor's positive response to Zeng's approach was absolutely critical to his success, in a way that was not ordinarily true for magistrates and prefects.

One of the steles was by Lu Qiong. He was living back home elsewhere, in Fuliang, but he was known in the Liaodong area because he had been exiled there for a decade just before this, having opposed Jiajing in the Great Ritual controversy.Footnote 33 So the teachers, students, and elders who set up the shrine asked him for an essay. Lu's essay, “Record of the premortem shrine to Mr. Zeng,” is elegantly constructed. (For the full and depleted texts, see ctext.org/static/contrib/literacy/sieve.html.) In outline, it looks like this:

I. Introduction: three hard things in the Way of the gentleman, with short quotations from Shu jing (The Book of Documents).

II. Mutiny and pacification by Zeng, including memorials. → #1 “rectify the will”

III. Pre-pacification court debate, and Zeng's victory → #2 “establish a strategy”

IV. Pre-mutiny bitter lives of soldiers and civilians, Zeng's rescue → #3 “extend benevolence to all.”

IV. Teachers, students, and elders built shrine; justification of living shrines.

V. Comparison with two Song-era premortem enshrinees

VI. Names, native place of Zeng.

Lu's theme is: “The way of the gentleman is three-fold: rectifying the will, stabilizing a strategic plan, extending benevolence to the masses.” In Section I, he elaborates on each of these three with short quotations from The Book of Documents, quotations that constitute complex comments on the negotiations between the court and Zeng over how to handle the incident. In each case, also, Lu first says that the action of the way of the gentleman (rectifying the will, making a stable strategic plan, extending benevolence to the masses) is difficult indeed; then he goes on to say how much more difficult it is under such-and such circumstances, which Zeng faced. To achieve even one of these establishes a man's reputation, Lu argues, but Zeng has done all of them together, and that is why the Liaodong people offer him premortem worship.Footnote 34

Section II narrates how Zeng settled the mutiny, repeatedly memorializing for lenience for most of the soldiers and for the civilians who had gotten caught up in the violence. The narrative evinces Lu's first theme by illustrating how Zeng “rectified the will”—But not his own will, which is how we would typically understand this phrase—but the will of the mutineers, and of the court and the emperor, by talking convincingly to both sides. Lu concludes the narrative: “Was this not loyally rectifying the will?” Section III narrates the earlier court discussion and illustrates the saying in the Documents that if you allow yourself to be frightened by the cowardly counsels of other courtiers, bending your body, you will pervert your mind. Lu represents unnamed courtiers who deployed bad historical analogies, afraid to take any action lest the situation only worsen. It was Zeng who figured out what to do, and he did it: he talked directly to the rank and file and rounded up the ringleaders. Difficulty number 2: was this not having the knowledge to establish strategy?

Section IV moves back another step chronologically. Lu lays out the misery of lives under cruel commanders and cruel officials of the troops and civilians of Liaodong, which had caused the mutiny in the first place. Zeng, he says, dealt with the whole situation, so that:

Today, when they plough and thus can eat, they call it Milord's feeding. When they weave and thus are clothed, they call it Milord's clothing. Fathers point to their sons, grandfathers point to their grandsons, and say: Milord gave them life. Is this not benevolence that reaches to everyone?

QED. Zeng did all three difficult things. 1. He swayed the emperor's will to his policy of lenience, and the mutineers’ will to obedience; 2. He out-argued and out-planned the cowardly, yammering, body-bending and mind-twisting courtiers to cheaply calm the strategic border area; and 3. He won over the locals, as the shrines attest.

Section V of Lu's stele essay describes how the teachers, students, and elders together requested permission from two named local commandants, gathered wood and cut stone, set up a shrine to the left of the school building, drew His Honor Zeng's image, and requested a text from Lu. Then Lu then poses a rhetorical objection to the institution and answers it.

Some may ask: Are living shrines ancient? I reply: they are ancient; they accord with ritual propriety; they are righteous.

Explaining how Zeng took responsibility for the people's good and bad fortunes upon himself, forcefully and efficaciously requesting lenience from the emperor, Lu continues:

The commoners, having received his grace, not only wish to look upon his face each morning and evening, but also wish to make their sons or grandsons know all about it. Originating in ritual propriety and arising from righteousness—this is the Way of antiquity.

Even if living shrines were unknown in ancient times, they are ritually correct because they arise from right emotion, as described in the Record of Rites. This is a common argument in the Ming premortem genre.Footnote 35

Section VI offers further proof, not only that premortem shrines are a well-established kind of institution, but also that Zeng deserves one. In keeping with his “X alone is hard, but Zeng did X doubled-in-spades and backwards-in-heels” tone, Lu argues that Zeng's achievements certainly match or surpass those of two named Song-era officials whose originally premortem shrines still exist. One had controlled bandits so that the Sichuan people drew images of him; but settling a mere incursion of outside bandits is nothing compared with the complexities of a mutiny. Lu ends (Section VII) with Zeng's names and native place.

I will give just one example of how Lu is complexly manipulating the Documents. Lu's passage (Section IV) on the third difficult thing in the way of the gentleman (extending benevolence) refers to “Pan Geng III,” but in effect reverses the meaning of the passage. Lu writes: “[The Documents] also says: ‘Reverently display your virtue in behalf of the people. Forever maintain this one purpose in your hearts.’” In the original passage in The Book of Documents, Zhou dynasty ancestor Pan Geng is exhorting his subordinates to reverently plan for the people's settlement and livelihood instead of enriching themselves. They should do this because they are the ruler's delegates, he has chosen them, and it should be their reverence for him that leads them to succor the people. The semi-autonomous relation of resident administrators to local subjects—what I call the Minor MandateFootnote 36—does not appear in the original passage.

Lu, by contrast, comments: “People-cherishing is difficult. But how much more difficult to earn their long-term yearning! It takes true benevolence to reach the masses!” (民懷難也。而況久思乎。維仁以及眾耳。). The original passage suggests that it is difficult for the ruler to convince officials to unselfishly care for the people. Lu, by contrast, uses the language of the repertoire of honors, using the trope of the eternal longing that leads to the people's keeping the memory of the magistrate in their bosom, not vice versa. Lu makes “people-cherishing” mean officials being cherished by the people, not the official keeping them in his bosom. Zhong (everyone, the masses) is an especially apt term here, since it originally meant troops, and Zeng was dealing with a mutiny. Lu's comment on this passage thus puts the focus firmly on Zeng's relation to the Liaodong garrison folk he protected, and whose yearning for him is demonstrated precisely by the premortem shrine being commemorated. The ruler is out of the picture; Zeng is not a mere delegate. This kind of subtle use or abuse of the classic would be evident, and perhaps arresting, to a classically literate reader, but not necessarily to a primer-literate one, as we will see.

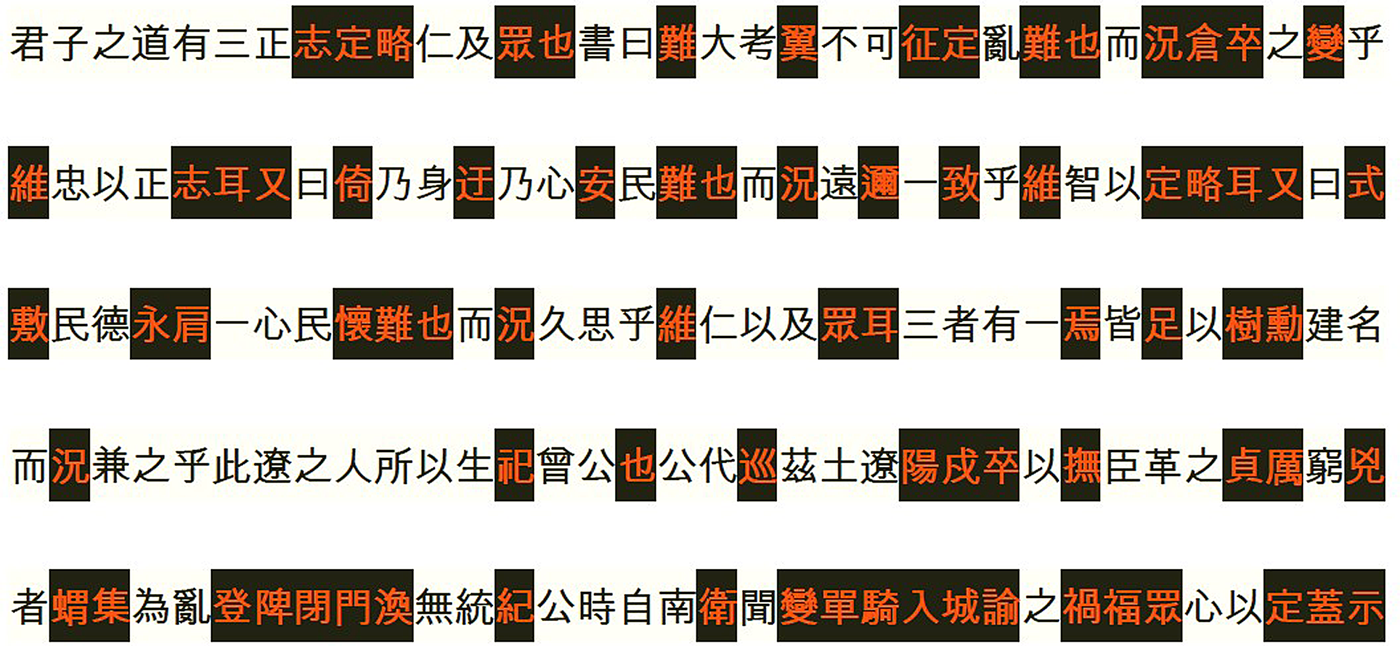

When this complicated essay is sifted using the Trimetrical Classic as the primer, 38 percent of the characters are legible, or just over one-third (See Figure 3).

Figure 3 Lu Qiong, Section I of “Zeng gong shengci ji” depleted to include only characters found in the Trimetrical Classic. The sifted-out characters appear in red, in black blocks. The primer-literate reader who knew only the Sanzi jing would be able to recognize only the black characters on the white background.

What remains of Lu's introduction (Section I) in this depleted text reads something like this (again, words I think the reader could easily guess at are in italics, as is the title Shu):

The way of the Gentleman has three correct things.

(1) Documents says: the great test of the Gentleman is that he cannot tolerate? create? disorder but must show his loyalty with correctness.

(2) It also says: One's body, one's heart-mind: are they distant from or united with the people in knowledge?

(3) It also says: The people are virtuous. Unite your heart-mind with the people and will they not long miss you? Benevolence takes reaching everyone.Footnote 37

These three all have one thing in common: Do they not all take building a reputation on uniting with them (meaning everyone)?

This is why the people of Liao live-enshrine Milord Zeng.

Compared with elaborate comments on the relation of ruler to courtiers, the depleted version focuses much more clearly on the people. Loyalty and correctness do appear. But more salient are uniting with the people, the people's missing you, and the virtue of the people; and the thing that ties all three together is not the difficulty facing the would-be gentleman as he tries to achieve even one, but the idea that all three gentlemanly things boil down to uniting with the people. Zeng has done that; that earned him a shrine.

In the depleted text, sections II, III, and IV, which narrate the events moving backwards in time, become hard to make sense of. The depleted text falls into two halves. The first half gives the impression that officials were being moved around in office in some unclear way; that poor people were making disorder and could not be controlled (readers of the stele for at least a generation after the event would have known that there had been a mutiny); and that Zeng heard about it and brought it to the court's attention. The emperor says very little in the original text. In the depleted text, he rants at some length about wicked people opposing him, showing no regrets, bragging of their exploits, ignorantly, fulfilling their desires if only for a day, committing crimes, and making all kinds of racket. The emperor apparently insists to Zeng, “Making chaos must stop!” and rants a bit more; he finishes up in self-exculpation: “The disorder is not of the dynasty's brewing!” In the second half of sections II, III, and IV in the depleted text, Zeng seems to respond, “It is wrong,” and talk about the thousand, the ten thousand people involved, both rebelling and suffering. The reader might guess it says something of his military movements from east to west without resting at night, perhaps leaving the bodies of bad guys in the hills. But it is not very clear.

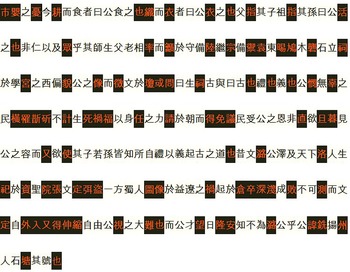

The next part of the depleted text, however, is very clear. Long sentences survive intact (See Figure 4).

Figure 4 Lu Qiong, End of Section IV through Section VII of “Zeng gong shengci ji” depleted to include only characters found in the Trimetrical Classic. The sifted-out characters appear in red, in black blocks. The reader who knew only the Sanzi jing would recognize only the black characters on the white background.

What would a person who had learned only the Three-Character Classic have been able to read of this section of Lu Qiong's essay? That Zeng is getting credit for assuring the people's livelihood, and that they are talking about it and telling the younger generations about it. That it is the fathers and grandfathers who declare that Zeng's benevolence reached to all, not the elite stele writer in his own judgment. (Again, the words in italics are those I think the reader might well guess.)

Today now, those who eat say, “It is Milord's feeding!” And those who … say, “It is Milord's …!” Fathers tell their sons. Grandfathers tell their grandsons, saying: “Milord is a case of benevolence reaching to …, isn't he?”

It is also clear who built the shrine: teachers (local or outside gentrymen) and local students (possibly from gentry families), and elders, meaning basically respected or wealthy commoners. The group asked permission of a local military official, but they prepared all the materials themselves.

The teachers, students, and father-elders mutually approached the Commandant … and continued by preparing east (huh?) wood and stone and set up at the school's west side Milord's shrine and a text at it (i.e. right here) that said: “Living shrine.”

Then one can read the question raised: are living shrines ancient? What makes them proper? The end of the stele might read roughly like this, if one knew only the characters of the Trimetrical Classic:

Are they ancient? They are ancient, they are ritually proper, they are righteous. Milord without hesitating? feared the people would not live. He used his own body's strength at the court and the people received Milord's grace and did not forget, but desired to see Milord's face and desire their sons, yea their grandsons all to know why. Ritual arises from righteousness: this is the ancient Way in old writings. Milord's moist fertility reaches the whole world. Human life is in the sages’ writings. In one place the people of Sichuan. In benefitting Liao's … it started in … When completed it was not permitted, but the writings themselves speak of freedom. Milord's great trial Footnote 38 and Milord's talent daily we remember. To know but not to do—that was not Milord, was it? Milord was from Yangzhou and the people's stone records his name.Footnote 39

We receive the distinct impression that the ancient way, as recorded in the old books, includes subjects deciding which officials are good and commemorating them on their own say-so. These are the sentences least injured by depletion; these are the ideas that stand out most distinctly. Whether or not the real sponsors of the shrine were commoners, the depleted stele text suggests that they ought to be the ones passing judgment in this very public and permanent way: setting up a shrine and a stone inscription explaining what the shrine rewarded.

At One-Fifth Comprehension: A Refuse-Gold Pavilion in Fujian

As a final example, I will present a stele for a related kind of institution, called a Refuse-Gold Pavilion. These were built to commemorate the departure of an official who was so upright that he would not accept a parting gift of money. This particular stele is from Fujian. It was written by Fu Zhen in 1540, but it commemorates a pavilion that had been built about 60 years earlier, in about 1478, to honor departing Magistrate Zhang Yi 張遜 for refusing to accept the money offered him by grateful commoners as he travelled out of the county. (For the full and depleted text see Appendix B.) The pavilion, built by a group led by Elder Su Cunming, originally had only a very simple stele reading “Mr. Zhang loved the people [like a] parent,” (張公愛民父母). In 1540, Censor Wang from Zhang's native place came through, saw the pavilion and stele, and correctly identified the recipient, having coincidentally heard about him from a third fellow townsman, Qin Fengwen.Footnote 40

Knowing the Hundred Surnames would give a reader only 22 percent of the characters in this text. Such a reader would miss about fifteen elements of the stele. He would miss

1. Why this location

2. Name and native place of Zhang

3. Date he arrived

4. His announcing his style of governance publicly

5. A sentence reading “His public-spiritedness was such that he could judge clearly; his incorruptibility was such that the people were not troubled: these are enough to know about his governing.”

6. The account of his promotion (people here might well have understood 福 correctly as referring to nearby Funing or Fuzhou)

7. The description of his send-off

8. The description of the earlier inscription that read only “Mr. Zhang Loved the People Like a Parent”

9. Who set up the earlier stone inscription

10. How it lacked detail and got lost among other steles

11. How through various gentry–official connections it was recovered and is now being expanded upon, in part through asking locals about Zhang

12. A reference to an episode in the official Han History in which a thank you gift is offered without being morally suspect

13. A long criticism of corrupt officials today, who demand such gifts and whom the people fear and hate

14. The role of the emperor in selecting magistrates, punishing the corrupt ones, and displaying the good ones

15. The end of Mr. Zhang's career

Missing all that, what would the reader who recognized only characters in the Hundred Surnames understand? I have re-ordered some characters within groups that would be meaningful together, and I have put in italics words that I think the reader would guess at and interpolate.

About five li to the east of town on the road together someone accompanied Magistrate Mr. Zhang and offered him some gold. Magistrate Mr. Zhang refused the gold. His Honor had completed some years here and had always steeped people in his grace. Above and below were in harmony. He was stern, pure, and able. His Honor was able to bring forth bright purity. His governance was in charge of blessing the hundred surnames. So when he departed there were people with gold following His Honor to the shady side of the hill. There was Mr. Zhang cherishing father-like. So in Ming times, able Mr. Zhang's governance is recorded on stone; we have on stone his methods. No-one has been able to match them for years as if he were a King in the classics we look back to. Yang. Gold. Time. Old man Qin Feng said “My worry lies in …” Mr. Fu has heard the shengyuan (government students) say that he purely cherished the people like children, as a bird broods over eggs. I record the outline: the fathers worked together, the seniors got rich with money, gold, and money. In response the commoners and elders together teach what they have heard to their sons: the magistrate shepherded the people, the sprouts in the kingly black hundred fields all hundred have benefitted from his, Mr. Zhang's, governance. Many times at many places there will be historians after this recording his deeds for the sons. Liu. Each autumn the people bless Mr. Zhang [or vice-versa].

The primer-literate reader would see that Zhang had looked after the people like a father, specifically by enriching them with money, while being incorrupt himself, and that they felt they should pay him back. That his good actions and methods of government are recorded on stone, certainly here but maybe also in other inscriptions, to be passed down to children and in history. That blessings should be or are called down upon Zhang every autumn.

A few surnames and one given name are legible, but unnamed commoners appear several times, as if they were the ones sponsoring the stele. Gentry and dynasty have dropped out entirely. It is also worth noting that Zhang appears less as a general moral exemplar than as someone who made people rich, and whom they therefore reward with long commemoration and gratitude.

Taking these three examples together, primer-literate readers certainly missed many elements of the elegant essays adorning the premortem steles. But the populist thrust of the steles comes through very clearly even when details are lost. The depleted steles argue, less logically and elegantly than the full versions but even more forcefully, that officials should serve the people, and that the people themselves decide which officials have done that, rewarding them with enshrinement.

Readings by Colleagues

To check for my own bias, I asked two colleagues to read depleted steles for me, using versions that did not show the sifted-out characters at all.

Tomoyasu Iiyama read a version of Yao Hongmou's “Stele record for Magistrate Zhu [Laiyuan's] Living Shrine,” sifted with The Trimetrical Classic. He concluded that he would have known from the title and terms like “benevolence” and “conscientious governance” that Lord Zhu had been a good former administrator, but not precisely why. Iiyama's reading clearly expresses that locals, including elders, wanted to submit a petition; that they collaborated to complete a shrine (indeed, since the names of the Han-era men drop out this seems to happen three times), and then wanted an inscription for it; and that Zhu's benevolent and wise governance consisted in “treating people as his own children.” The Son of Heaven appears, but the emphasis is on the judgement of elders, literati, and others, as manifested in the shrine.

Charles Sanft read a premortem stele essay by Zhan Ruoshui, sifted with The Thousand Character Essay.Footnote 41 The essay compares people's hatred of bad officials to their appreciation of those few who (in their judgement) act as “father and mother to the people,” and condemns corrupt officialdom generally. Given his practice of lecturing to commoners, Zhan may have been writing specifically to reach less-literate readers.Footnote 42 For the gist of his essay comes across in the depleted version, according to Sanft's reading. While antique edicts cared for the people like children, contemporary edicts rob them; and locals happily sang, attributing their clothing to “Mother Li” and their food to “Father Li.” The local people appear as “children,”—it is true: but children who righteously judge the officials who rule them, as the shrine itself evinces.

Caveats

Of course, the examples also show that using the Sieve gives only a rough guess at possible readings. Even more than with the translation of texts that actually exist, the interpretation of these imaginary texts could be debated in many ways.

One problem comes in my assumptions about how readers would deal with the characters they could see, but did not recognize. Psychologists offer several models explaining how the partially literate deal with texts, but surely people would not simply ignore the characters they did not know; rather, they would make guesses. So my imagined readings of depleted texts sometimes form sentences with the characters that remain, but sometimes make sense of groups of readable words that do not form grammatical sentences. This process—readers using the characters they can read to make out a general idea of what the text said, rather than worrying about creating sentences—is an observed phenomenon in the case of spoken language, called “good-enough processing.” In Wu Song's case, good-enough processing worked: he realized out that there was a tiger on the ridge ahead of him. In other cases, the reader's “good-enough processing” might mislead him as to what the full target text actually said.

A committed reader tries hard to read characters from their radicals or phonetics.Footnote 43 This is called “bottom-up-ing” the text or “data-driven processing, which would give the viewer an active role in perception.”Footnote 44 Limin Bai shows that some late imperial teachers did explain radicals and phonetics to their pupils, equipping them for this strategy, but I decided that I could not systematically allow for such guesses.

Finally, the primer-literate reader might use what is called “top-down” or “hypothesis-driven” processing. That means purposely using any knowledge of the world or about language to work out roughly what the target text says.Footnote 45 Surely the primer-literate reader would do some of this “top-down processing,” using knowledge of language (four-word phrases, for instance) or knowledge of the events recorded. Ordinary people did know about the state, history, morality, and so on, often from drama, Huang Xiaorong has argued. For example, one drama lists the Ming provinces, another lists how many years each Ming emperor reigned, and a third reports that “Grandpa Yongle moved the capital to Beijing” and relates the functions of the six ministries, the Hanlin Academy, and the Embroidered Guard.Footnote 46 Again, I could not systematically put such individual knowledge into my analysis. A researcher who wanted to make a fuller set of guesses at how a particular text was read could not only sift with different primers but also generate a range of possible readings based on different assumptions.

A second problem is genre, for Classical Chinese words vary in their meaning. Would the reader assume that this was a Confucian-type text or a deity-shrine type text, or be genre-savvy enough to distinguish? Would she or he be thinking in the local vernacular instead of in Classical Chinese? I have assumed that students would expect Classical Chinese in an inscription on an impressive stone, and the primers themselves slant towards Confucianism.

A third problem is that I am envisioning a single reader. Theories differ on the “interpretive community” and how far its readings are or are not constrained by the text itself.Footnote 47 More practically, as the ubiquitous commenting and gossiping crowd in Ming stories suggests, a group of kibitzers is far more likely than a solitary reader. Indeed, the most overt political importance of my findings would come from such a group—not only what they read, but where the discussion went after that. Of course, their understanding of the text would include what they already knew about their former and current magistrates and other political matters. Furthermore, once the group had decided on a reading, it might be hard to shake. The next person in the reading community might simply be told what the group thought the stele said, and he might find it hard to shake that off and start from scratch himself.

But as reader-reception theory shows, it is hard to know how any text was really read. As one scholar put it as far back as 1938, “each encounter between a reader and the text is a unique event.”Footnote 48 The Sieve's very imperfect approach to the important question of how less-literate late imperial people read is better than nothing.

Conclusion

Considering whether and how literacy learned from the standard late-imperial primers might challenge, as well as support, scholar-official dominance of political and moral authority, this article has presented three readings of steles depleted to contain only the characters in certain primers. It has presented slightly different ways in which researchers might imagine readers to fill in meaning in the characters they did not know. I have pointed out some of the limits of this highly imperfect method of ascertaining reader reception. Readers can decide for themselves whether, in an area of historical inquiry in which we all want answers, this speculative method is better than nothing.

Although it has proved to have other uses, the Late Imperial Primer Literacy Sieve was originally designed by Joshua Day to answer a particular research question for me. The question was whether a primer-literate reader in Ming times could have gleaned from premortem shrine steles one idea that many of them embedded. That idea, as I established in my wider study of living shrines, was that Ming people who were neither officials nor gentry had a right to a certain kind of political participation, namely the right to publicly, explicitly, and through a potentially long-lived institution, pass judgement on the men assigned by the emperor's bureaucracy to rule them. I conclude that, indeed, that message could have come across.

What readers did with the message is another question. But perhaps reading the message on public steles contributed to the picture Lynn Struve painted thirty years ago:

in the late Ming in virtually every social sector one can find evidence of severe strain on traditionally accepted relations between superiors and inferiors—for instance, landlords and tenants, masters and servants, employers and workers, literati and nonliterati. The first half of the seventeenth century stands out in Chinese history for the frequency and virulence of such things as: revolts of indentured servants against household heads, from whom goods, freedom, and self-humiliation were demanded; rent-withholding against landlords, which was incited by a variety of unfair practices; strikes by mining, industrial, and transport personnel, stemming from both government mismanagement and regional or periodic economic disjunctions; counterattacks by religious sects and illegal, underground organizations against the suppressive authorities; … army mutinies and mass rural uprisings … and banditry of every kind … the late Ming is distinctive [among periods of dynastic decline] for the blatancy and pervasiveness of the spirit of revolt in its society.Footnote 49

If premortem steles’ legitimation of popular participation in politics did reach the primer-literate reader, then literacy may have empowered commoners.

Appendix A: Full and depleted text for Yao Hongmo 1584 with the Classic of Filial Piety. The normal and black characters are those that appear in the primer.

朱邑侯生祠碑記 姚弘謨

廬江朱侯令吾秀水六年勞來不怠所部吏民愛敬之已而侯以治行高第召入為選曹郎當去父老遮道攀轅泣下願侯毋行不可則僉欲上書借侯願得賜璽書進秩賜金令侯長治秀水不可則竊竊然肖侯而俎豆於城之西民之荷鋤插以相事者趾相錯而祠遂成焉祠成宜有記余每覽觀往籍覩古所稱述循吏文翁朱邑之屬多自廬江文翁以寬仁化蜀而朱邑則廉平不苛亦率廩廩有德讓君子之風焉已余登廬山而望廬江其俗寬緩闊達以為地固宜然其慈仁蓋天性也今觀朱侯其外恂恂常若有所避退其中疏朗洞達其為人精敏有智略自部署名曹什物能以小致大因力行之有名實不應必之其所繇常有所更徭既已定輕重各有差有一人獨前爭弗肯服侯應謂之曰爾某所陂山田幾何某所樓臨某街幾何家直累數百金爾避弗任誰肯當任者某人皇恐謝服吏民大驚不知所出咸稱其神明然其治視民如子務在成就全安之時禁網日密民人抵冒相告言罪大姓或以氣力漁閭里吏長短而下戶之猾亦多為懻忮躪大家吏或鼠首不敢詰其虎而冠者以為非武健嚴酷不能勝任而侯獨用寬和為名性仁恕雖當徵斂亦未嘗轻為笞辱其富者以時輸委而貧者與為要期亦未嘗乏絕其奏讞疑獄必前為根株其情實可出者出之即不可者亦傾意停平之嘗自稱曰吏民所以嘆息愁恨者苦吏急也奈何妄用三尺羅織之耶為令前後凡六年民皆化之夜無犬吠之盜監司上其治行為天下第一天子以侯終長者迺召拜為吏部郎士民因為祠祀之以志思也常攷文翁治蜀吏民立祠堂歲時祭祀而朱北海至謂其子必葬我桐鄉後世子孫奉嘗我不如桐鄉民其子如其言民果為起冢立祠祠祭至今不絕語云不知其官視其民以侯方之一何左券不爽也然三人皆自廬江廬江故多長者良然哉然余比觀世之達人賢士非其貪頑不稱職者一切亦皆彬彬質有其文武焉然頗用殊輔其資如侯之篤行脩潔斯鞠躬君子也其蒙顯號於世有以也夫侯姓朱諱來遠廬江人為萬曆丁丑進士云

Appendix B: Full and depleted text for Fu Zhen 1540 with the Hundred Surnames. The normal and black characters are those that appear in the primer.

卻金亭記 傅鎮

廬江朱侯令吾秀水六年勞來不怠所部吏民愛敬之已而侯以治行高第召入為選曹郎當去父老遮道攀轅泣下願侯毋行不可則僉欲上書借侯願得賜璽書進秩賜金令侯長治秀水不可則竊竊然肖侯而俎豆於城之西民之荷鋤插以相事者趾相錯而祠遂成焉祠成宜有記余每覽觀往籍覩古所稱述循吏文翁朱邑之屬多自廬江文翁以寬仁化蜀而朱邑則廉平不苛亦率廩廩有德讓君子之風焉已余登廬山而望廬江其俗寬緩闊達以為地固宜然其慈仁蓋天性也今觀朱侯其外恂恂常若有所避退其中疏朗洞達其為人精敏有智略自部署名曹什物能以小致大因力行之有名實不應必之其所繇常有所更徭既已定輕重各有差有一人獨前爭弗肯服侯應謂之曰爾某所陂山田幾何某所樓臨某街幾何家直累數百金爾避弗任誰肯當任者某人皇恐謝服吏民大驚不知所出咸稱其神明然其治視民如子務在成就全安之時禁網日密民人抵冒相告言罪大姓或以氣力漁閭里吏長短而下戶之猾亦多為懻忮躪大家吏或鼠首不敢詰其虎而冠者以為非武健嚴酷不能勝任而侯獨用寬和為名性仁恕雖當徵斂亦未嘗轻為笞辱其富者以時輸委而貧者與為要期亦未嘗乏絕其奏讞疑獄必前為根株其情實可出者出之即不可者亦傾意停平之嘗自稱曰吏民所以嘆息愁恨者苦吏急也奈何妄用三尺羅織之耶為令前後凡六年民皆化之夜無犬吠之盜監司上其治行為天下第一天子以侯終長者迺召拜為吏部郎士民因為祠祀之以志思也常攷文翁治蜀吏民立祠堂歲時祭祀而朱北海至謂其子必葬我桐鄉後世子孫奉嘗我不如桐鄉民其子如其言民果為起冢立祠祠祭至今不絕語云不知其官視其民以侯方之一何左券不爽也然三人皆自廬江廬江故多長者良然哉然余比觀世之達人賢士非其貪頑不稱職者一切亦皆彬彬質有其文武焉然頗用殊輔其資如侯之篤行脩潔斯鞠躬君子也其蒙顯號於世有以也夫侯姓朱諱來遠廬江人為萬曆丁丑進士云