INTRODUCTION

What makes for a successful political campaign on social media? While there is a consensus that social media is a critical feature of contemporary political campaigns, the literature remains conflicted about how and how much social media matters to voters and outcomes. The conventional approach calls for a focus on a candidate's use of social media for messaging and mobilization (Grant, Moon, and Grant Reference Grant, Moon and Grant2010; Gilmore Reference Gilmore2012). We know, for instance, that there is a strong correlation between a candidate's use of social media and electoral wins (LaMarre and Suzuki-Lambrecht Reference LaMarre and Suzuki-Lambrecht2013). Others, however, contend that frequency matters less than the quality of communication styles (Bennett and Segerberg Reference Bennett and Segerberg2011; Wells Reference Wells2015; Groshek and Dimitrova Reference Groshek and Dimitrova2011; Hong and Nadler Reference Hong and Nadler2012). Building on these insights, scholars are increasingly coming to the conclusion that the energy behind modern-day social media campaigns lies with users and supporters, not the candidates themselves (Gibson Reference Gibson2015). The principal research question thus is how candidates and their campaign managers can harness and amplify that energy.

It is perhaps here that the literature faces its greatest challenge. First, despite what we have learned about messaging, user engagement, and network building strategies, we are increasingly confronted with vivid demonstrations of how candidates with rudimentary Internet skills, replete with grammar and spelling mistakes, can conquer social media in ways that their more savvy and competent peers could only dream of. Moreover, the rise of paid trolling, fake followers, informal influencers, bot-based disinformation, and foreign intervention has raised uncomfortable questions over the degree to which candidates themselves are the primary agents behind social media campaigns, and whether the social media indicators we rely on are themselves contaminated by virtual manipulation.

In this article, we enter the fray by exploring the role of social media during the 2016 Philippine presidential election, a heated contest accompanied by one of the most contentious and noxious social media battles waged over the last five years (Buenaobra Reference Buenaobra2016). In that election, Rodrigo Duterte, an insurgent populist,Footnote 1 swept into office with what appeared to be an army of dedicated social media followers who embodied Duterte's own brutish sensibilities and dominated the virtual political landscape (Ressa Reference Ressa2016). Taking note of Duterte's prominent digital profile, many have tied his electoral success to his campaign's effective use and misuse of social media to get out the message and mobilize supporters (Ressa Reference Ressa2016). For others, however, the credit goes to Duterte's fervent fans and their decentralized, yet aggressive and effusive support for their champion (Arguelles Reference Arguelles2019).

Still, for many, the role of social media in the Philippine presidential election, like that in the United States, remains a murky domain, populated by paid trolls, bots, and foreign provocateurs (Bessi and Ferrara Reference Bessi and Ferrara2016; Wooley and Howard Reference Woolley and Howard2017). While it is perhaps convenient to attribute social media victories like Duterte's to manipulation and intervention, doing so risks diminishing, even side-stepping, the role of actual voters and their participation in the social media campaign. Moreover, a narrow focus on virtual manipulation ignores the potential synergies between online activity and grassroots political mobilization. Instead, we argue that grassroots support for a candidate will manifest in intense support for them online as well. The corollary, however, is not necessarily the case—a high octane or even counterfeit social media campaign may not be sufficient unless there is a stock of potential supporters waiting to be activated. When deployed in conjunction with offline support, however, social media operates as an amplifier, providing a platform for fans, influencers, and trolls alike, to organize, mobilize, and manipulate online sentiment and activity in support of their candidates.

Our insights are informed by a comprehensive review of social media activity during the election, accompanied by an original post-election survey of Filipino voters. In some respects, our findings mirror the conventional narrative. For instance, our analysis of Facebook activities and comments on the public pages of the five major presidential candidates—Manuel “Mar” Roxas, Grace Poe, Miriam Defensor Santiago, Rodrigo “Rody” Duterte, and Jejomar “Jojo” Binay—confirms that Duterte's online fans were the most active, engaged, and networked advocates. Moreover, a careful analysis of activity on these pages confirms that Duterte's digital fans were uniquely zealous, aggressive, and unrelenting in their support for Duterte, as well as in their abuse of his opponents. Such patterns seem consistent with the behavior of paid trolls and influencers.Footnote 2 Indeed, there is ample evidence that at least some of the pro-Duterte social media traffic was generated by influencers, bots, and foreign entities (Ong and Cabañes Reference Ong and Cabañes2018).

But were Duterte's digital fans simply a “keyboard army,” financed and manufactured by his campaign? Our analysis departs from the conventional narrative. First, we find that Duterte's own social media presence was relatively anodyne, his messaging was minimal, and his rhetoric far more reserved than the thuggish flair he displayed on television and in rallies. Indeed, Duterte's Facebook engagement was a textbook example for “how not-to-do online campaigning.” He wrote in the third person and barely posted any original content. In comparison to his rivals, he did not invite any input from Facebook users nor was he responsive to fan engagement. By contrast, his peers were much more active and savvier in their use of social media for messaging and outreach. Early frontrunner Grace Poe, for example, was very active and engaging on Facebook: she posted at least three times more than Duterte, responded to her supporters online, and regularly created ready-to-share content complete with hashtags across her four social media platforms. Yet Poe's Facebook campaign was the least popular of all major candidates in the 2016 election.

Looking beyond the candidate and their campaign activities, our survey findings suggest that Duterte's digital fans were distinct in more than just their online passion for Duterte. In particular, survey results show that Duterte supporters made up their minds earlier than supporters of other candidates, voted as groups, were more likely to split their ballots, and were also the most likely to join offline rallies. These findings are consistent with recent studies examining Duterte's strong grassroots offline support (Curato Reference Curato2017; Teehankee and Thompson Reference Teehankee and Thompson2016). At the same time, evidence of offline support does not negate the role of trolls, influencers, and informal actors in boosting Duterte's online profile. Indeed, it is quite likely that Duterte's trolls and influencers were driven by both material incentives and ideological enthusiasm for Duterte. Instead, by linking online and offline behavior our empirical findings validate the principal observations of previous research, which stresses the porous boundary between manufactured and authentic online support (Ong and Cabañes Reference Ong and Cabañes2018).

In making this observation, our study also echoes findings from comparative scholarship on digital campaigns and manipulation. A comprehensive review of the American presidential election of 2016, for instance, finds that the most important feature in the digital manipulation campaign was that Trump supporters proved to be enthusiastic consumers and propagators of misinformation (Jamieson Reference Jamieson2018). Moreover, in challenging conventional narratives about the 2016 Philippine election, this article makes several contributions to the broader literature on social media and elections. First, we show that an online campaign does not need to be professional, engaging or self-actualizing in order to succeed. Relatedly, we show that synergies between candidates and their digital fans can arise even if the candidate ignores their potential. Taken together, these findings add to an emergent scholarship aimed at the broader social media ecosystem, highlighting the role of supporters, influencers, trolls, and intermediaries (Groshek and Dimitrova Reference Groshek and Dimitrova2011; Hong and Nadler Reference Hong and Nadler2012), in addition to that of traditional candidates and campaign managers (Gilmore Reference Gilmore2012). Finally, by exploring the social media effect on elections in a developing country with a young democracy and intense social media penetration,Footnote 3 we shift the focus of attention from countries where social media is being incorporated into existing and well-established patterns of political competition to those where the Internet and social media are defining the way democratic contests are waged.

This article has three main sections. The first section discusses the three models of social media engagement, followed by a set of corresponding empirical expectations for each model. The second section provides background on the 2016 Philippine presidential elections, alongside a detailed account of the methodology and empirical strategy of our study and discusses its findings. The final section provides a summary of the main findings with a discussion of implications and suggestions for future scholarship.

SOCIAL MEDIA CAMPAIGNING AND ONLINE POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT

The Broadcast Model

Much of the extant literature on social media campaigning focuses on how political parties and candidates use social media during an electoral race (Vergeer and Hermans Reference Vergeer and Hermans2013; Kushin and Yamamoto Reference Kushin and Yamamoto2010; Larsson and Moe Reference Larsson and Moe2012). These top-down or ‘broadcast’ approaches analyze social media campaigns from the perspectives of the candidates or their political parties—seeking first and foremost to understand their online communication strategies (Grant, Moon, and Grant Reference Grant, Moon and Grant2010). Within the broadcast model of online campaigning, there are three sub-types: the savvy, active, or populist communication style. The ‘Internet savvy communication style’ espouses a positive relationship between active, frequent, and professionalized social media campaigning with higher levels of fan engagement (Williams and Gulati Reference Williams and Gulati2013; Larsson and Kalsnes Reference Larsson and Kalsnes2014). In their study of the 2010 US midterm elections, Autor and Fine (Reference Autor and Fine2018) argue that in competitive races, candidates who were more active on Facebook were able to solicit more donations and mobilize more supporters than their less active opponents. Still, others suggest that what matters is authenticity, typically in the form of a ‘populist’ communication style, rather than active and savvy usage. In comparing Hillary Clinton's and Donald Trump's Twitter activities during the 2016 US presidential campaign strategies, Enli (Reference Enli2017) argues that a more effective strategy is one of amateurism and portraying oneself as an ‘authentic outsider.’ Focus group participants in her study preferred the ‘gut-feeling tweeting’ over a highly professionalized one coming from a ‘controlled politician.’ In the 2013 Italian general election, negative campaigning on Twitter was found to be more effective in winning over voters than positive messaging (Ceron and d'Adda Reference Ceron and d'Adda2016). Whether savvy, populist, or authentic, top-down approaches to thinking about social media campaigning place agency in the hands of political candidates and their campaign organizers. Social media users, by contrast, play a passive role in the broadcast models, theoretically and empirically.

The Grassroots Model

In contrast to the top-down approaches, a small but growing subset of the literature argues that the main contribution of social media to election campaigns takes place in a bottom-up and decentralized manner (Jorge, Pimenta, and Farinha Reference Jorge, Pimenta and Farinha2014; Gibson Reference Gibson2015). According to this perspective, politicians and parties should step away from the broadcast model of communication, where they push out information and instruct the public to take particular actions (Wells Reference Wells2015). Gibson's concept of “citizen-initiated campaigning” argues that by devolving power over core campaigning tasks to the grassroots, political parties could mobilize more voters. Based on her study of the 2010 UK general election, this bottom-up approach to digital campaigning is particularly suitable for new parties with few resources. In Spain, the electoral victory of Podemos in the European Parliament in 2014 demonstrates the strength of its tech-savvy grassroots support, as the party itself came from the social media-driven anti-austerity 15-M movement just a few years before (Casero-Ripollés, Feenstra, and Tormey Reference Casero-Ripollés, Feenstra and Tormey2016). Insurgent benefits from willing and motivated followers also increase the likelihood of success when it comes to electoral manipulations. As Jamieson (Reference Jamieson2018) argues in her examination of the Russian influence operations in the US 2016 presidential election, the Russian discourse saboteurs were so effective because of the readily available pro-Trump supporters who were enthusiastically amplifying their messages.

The Self-Actualizing Model

More recent studies argue for an intermediate approach that focuses on the intersection between top-down messaging and bottom-up mobilization. For instance, under the “connective action” framework put forward in Bennett (Reference Bennett, Fine, Sifry and Rasiej2008), savvy politicians use informal messaging to foster “shared experience” by stimulating “self-actualizing” crowd input and engagement (Grömping and Sinpeng Reference Grömping and Sinpeng2018). Examples of this strategy include inviting crowd input for suggestions on actions to take, interacting with the crowd and providing inclusive and undirected motivation to take action, where the crowd could opt-in and out at will (Lilleker and Jackson Reference Lilleker and Jackson2010; Harfoush Reference Harfoush2009; Enli and Skogerbø Reference Enli and Skogerbø2013; Kreiss Reference Kreiss2016). Kruikemeier and colleagues (Reference Kruikemeier, van Noort, Vliegenthart and de Vreese2013, 53) find that “highly interactive and personalized online communication does increase citizens’ political involvement.” Bimber (Reference Bimber2014, 131) similarly argues that “personal political communication is crucial” to the successes of Obama in both the 2008 and 2012 elections. In sum, Facebook pages that rely heavily on crowd suggestions for action and fan-driven activities and content should elicit greater public support than those that do not integrate self-actualizing communications.

Expectations

To reiterate, the conventional perspective on social media campaigns is that online engagement is driven by polished top-down messaging and mobilization by candidates with the help of experienced online advertising and promotion agencies.Footnote 4 Our objective is to see whether the social media campaigns of the main presidential candidates were consistent with any of the three models outlined above. If the broadcast perspective is correct, we should expect social media activity to be driven by savvy top-down messaging from candidates and their online campaigns. In the Philippine context, we should thus expect the Duterte campaign to have been more engaged, more active, more populist, and more responsive to the input and contributions of its social media followers. Alternatively, if social media campaigning is a bottom-up process, we should not expect to see much interaction or directionality between candidate behavior and online support. Instead, a bottom-up approach would predict self-motivated and decentralized social media activity emerge in support of preferred candidates. Still, it could be that top-down messaging acts a catalyst for bottom-up mobilization, resulting in what is referred to as self-actualizing “connective action.” Under this interactive perspective, we would expect a high number of posts and replies to posts corresponding with a high frequency of likes, shares, and comments per posts. We would also expect a highly personalized and self-actualizing way of communicating through these posts, where the candidate would speak directly to his or her fan base (in the first person) and invite a lot of fan participation. For example, instead of giving information about a candidate's rally location, it would be asking supporters to come up with slogans for rallies and memes.

While each of the conventional models offers distinct expectations, we stress that they do not represent either a complete or a mutually exclusive account of social media effects on political engagement. For instance, the self-actualizing model, though emphasizing interaction, still places agency in the hands of candidates and campaign managers (Loader and Mercea Reference Loader and Mercea2011). This need not be the case, however. Intermediaries, such as influencers and trolls, can employ similar strategies by mobilizing or agitating their audience into engagement, without instruction or guidance from the campaigns themselves (Brown and Fiorella Reference Brown and Fiorella2013). Nowhere is this proposition more relevant than in the case of the United States, where numerous studies and government inquiries confirm that foreign influencers manipulated social media accounts in favor of one candidate during the 2016 presidential election, even if the candidate was broadly ignorant of how these strategies were pursued in practice (Jamieson Reference Jamieson2018; Benkler, Faris, and Roberts Reference Benkler, Faris and Roberts2018). Assuming this was also the case in the Philippines, however, how then do we characterize online engagement? Is it bottom-up, interactive, or simply manufactured?

While we lack the data to address this conceptual question directly, our theoretical approach does lead to different observational implications about online participation depending on whether we believe it is entirely fabricated or if we allow for the possibility that at least some of the fervor was driven by genuine devotion for the candidate. In particular, if digital participation was entirely fabricated, regardless of whether the effort came at the behest of the candidates or thanks to interference from other interested parties, we would expect it to be a relatively thin and narrowly virtual campaign, disconnected from offline political behavior. On the other hand, if social media fervor for Duterte was in part authentic, we should observe similar degrees of enthusiasm in measures of offline behavior.

EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

We draw on two sets of empirical data to evaluate the competing expectations outlined in the previous section. The first set of data draws from all Facebook activities (posts, comments, replies, reactions such as ‘likes’) across the public pages of Poe, Santiago, Duterte, Binay, and Roxas, totaling more than 20 million data points from February 9 to May 9, 2016—the entire official campaign period. The second set of data comes from a retrospective survey of 621 online respondents from 4 regions: 30% Manila, 15% Mindanao, 35% Luzon, and 20% Visayas, conducted in August 2017. Online political engagement includes Facebook activities such as posting, sharing, commenting, and liking. “Fans” are online supporters of candidates and constituted a majority of users who interacted with pages of the five main candidates.Footnote 5 Both sets of data have their own limitations, which we outline after each analysis. Considered together, however, the findings suggest that none of the conventional expectations fully account for the viral social media dominance enjoyed by Duterte in the 2016 contest.

Analyzing Facebook Presence

We chose Facebook as a site of online data analysis because of its dominance in social media arena in the Philippines, with a 94 percent penetration rate among the online population and its usage far outstripping other platforms. Filipinos also top the world's rankings for spending the most time on Facebook since 2013 (Kemp Reference Kemp2018). In short, if presidential candidates wanted to broadcast their political messages to as many people and as easily as possible, there was no superior platform than Facebook. We also conduct further analysis on 39,942 randomized comments and 6,141 replies to randomized comments, and we perform content analysis on 356 randomized replies. The Facebook data was extracted directly from Facebook using R and the Rfacebook package by Pablo Barbera.Footnote 6

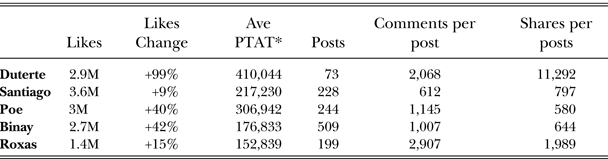

TABLE 1 Facebook Campaign Effectiveness in Comparison

Note: Authors’ own calculations. Average People Talking About This (PTAT) = average number of people interacting (posting, commenting, liking, sharing) per each post. It is a main measurement of interactivity used in social media analytics.

We use this data to conduct a comparative analysis of the effectiveness of social media campaigning across the official pages of the five main candidates. In line with previous research, we assume that campaign managers seek to generate a high degree of digital engagement with the campaign Facebook pages. According to this standard metric, our quantitative analysis shows that Duterte had the most effective Facebook. With the few posts he made, Duterte was able to gain the highest number of likes, engagement, and comments per post. Within the span of the three-month campaign period, his fan base grew 99 percent, in comparison to Poe's 40 percent and Santiago's 9 percent. The strongest indicator for campaign effectiveness was the average level of interactivity per post. For each post Duterte created, more than 400,000 people (unique Facebook user) interacted with it. This ratio far outstripped his rivals by at least 100,000 users. More than 11,000 fans shared his post each time it was written. Sharing is the most crucial indicator of “virality” for a social networking site like Facebook that relies heavily on interaction across networks. Duterte also elicited more than 2,000 comments per post—the most active form of engagement in the Facebook world. While Roxas may have elicited slightly more comments per post than Duterte, at least 3 percent of his top comments were Duterte supporters. In contrast, none of the supporters of other candidates were at all present in the top comments on Duterte's page.Footnote 7 His social media campaign was, by all accounts, the best performing and unmatched by his rivals.

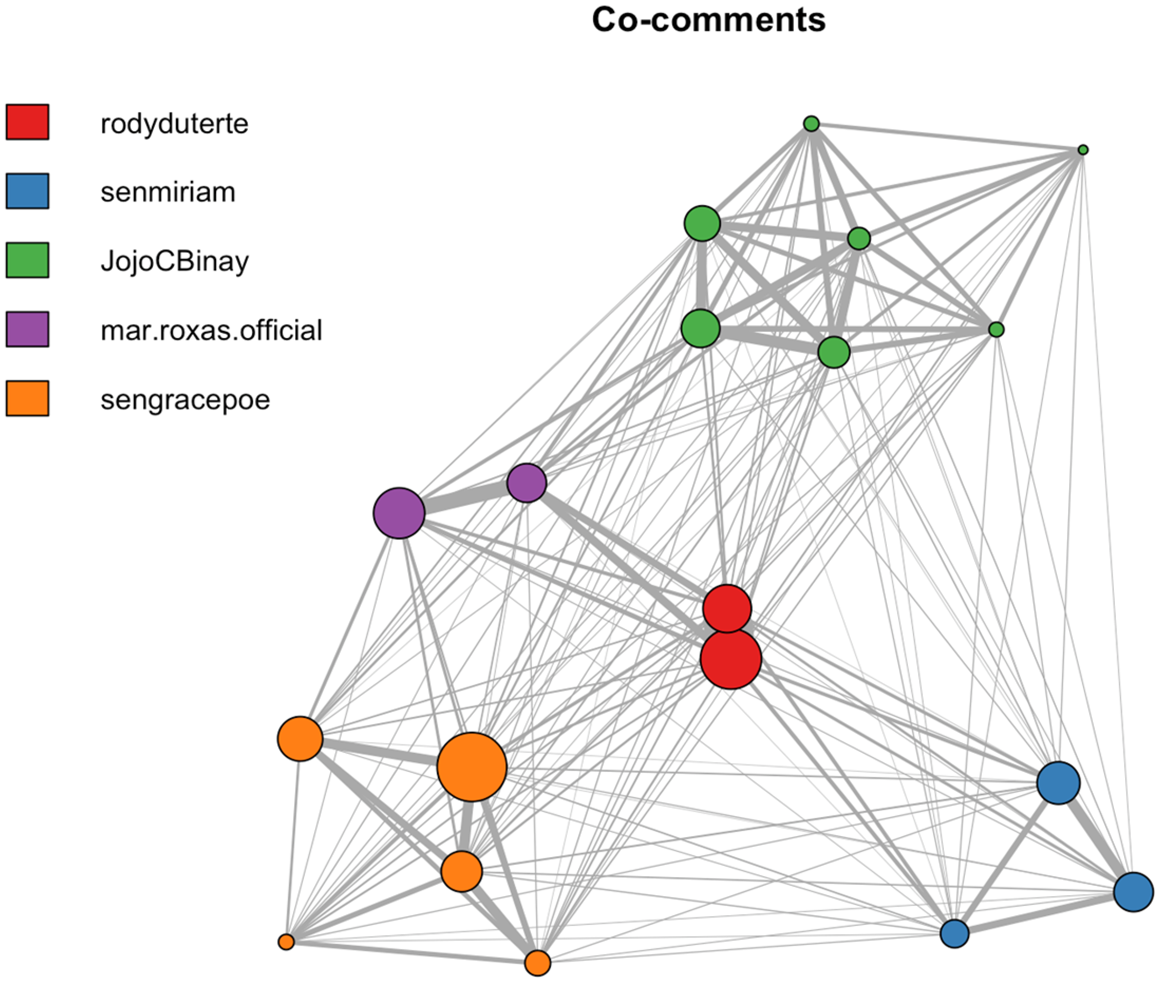

Duterte's viral campaign is further demonstrated by the centrality of his networks on Facebook. Our social network analysis across the five candidates demonstrates two important features of Duterte's Facebook campaign. First, his Facebook page was the most central candidate page among supporters of all candidates (Figure 1). By extracting the unique user ID of those who commented and replied to comments on all five pages, we were able to cross-reference users who liked a candidate, commented on that same candidate's page and also on another candidate's page. For example, we wanted to find out how many people who liked and commented on Roxas's page also commented on Duterte's page (but not liking him). This would indicate that this person was a supporter of Roxas but was also engaging with Duterte (but not necessarily supportive of him). We then visualized the networks of individual co-commenters on all five candidate pages with the highest number of co-commenters in the center of all networks.

FIGURE 1 Co-Commenter Networks Across Five Presidential Candidates

Note: Each node is a post on one of the five pages. The size of the node is the number of comments received by the post. The edges connecting the posts indicate how many users have been commenting under both posts. A color version of this figure is available in the online version of this article.

Figure 1 clearly demonstrates that Duterte (in the middle) was the most central page within the networks of his own fans and other candidates’ fans. Supporters of other candidates were talking about him the most—making his page popular as engagement created traffic to the page. The more interaction Duterte received, the more traffic and the greater his Facebook virality. As people (fans and non-fans alike) spent time talking about him on Facebook, Duterte's page had become the focal point of Facebook activity during the campaign period. Our findings support Facebook's own statistics released just a few weeks before the election that Duterte dominated 71 percent of all global conversations about the Philippines election (CNN Philippines 2016). That nearly 16 million people were talking about Duterte and creating 190 million interactions on Facebook—for good or bad—is the definition of “going viral.” Virality on Facebook means Duterte is more likely to appear on Facebook newsfeeds of most Filipino users than any other candidate.

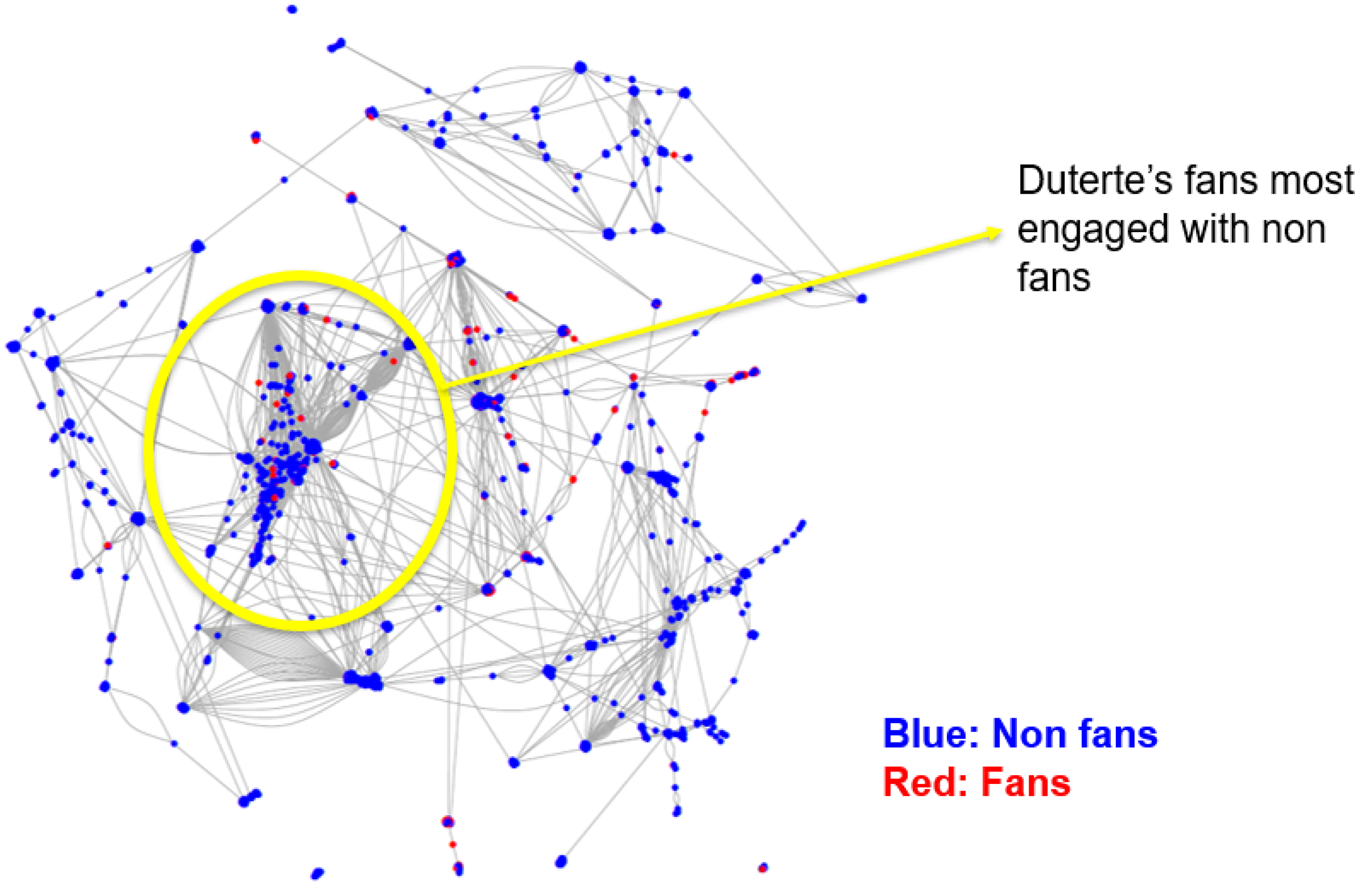

To get a better sense of how each candidate's supporters interact, we estimated network homophily—propensity to associate across dissimilar groups—for Duterte's commenters in relation to those of other candidates. This analysis permits us to assess how polarizing Duterte's networks were (Easley and Kleinberg Reference Easley and Kleinberg2010). If Duterte's supporters communicated only with one another, we would find a closed and rather segregated fan network. If the reverse, then we would observe a highly engaged network with a low degree of homophily. Figure 2 shows the latter case, with Duterte's fans (red) clustered around tight networks of non-fans—those who commented on Duterte's wall but did not like him. This is in stark contrast to networks of Poe, Santiago, Roxas, and Binay, which demonstrated a high level of homophily, in which fans were clustered together and not engaging with non-fans. Both social network analyses further show the distinctiveness of Duterte's Facebook campaign: not only was his page popular among his support base and observers alike, his own fans were the only ones who were actively engaged with those who did not support him. A manual review of some of the replies to comments suggested that most Duterte fans were defending their candidate from the criticism of non-fans. They were also the only groups whose pro-Duterte comments appeared in other candidates’ pages on a regular basis. Regardless of the sentiment of engagement, outward engagement helped to further increase the importance of Duterte's Facebook page to a level far beyond the influence of his page administrators.

FIGURE 2 Duterte's Social Network Homophily Analysis

Note: Each node is a user. Each connection indicates a reply to another user's comment. The size of a node is the number of comments posted by the user. Two nodes are close if they engage with a lot of replies. The same analysis was performed for the other four candidates but their visualizations are not included here. A color version of this figure is available in the online version of this article.

Yet Duterte's social media success does not appear to have come as a result of reasons posited in either the broadcast or self-actualizing models. Duterte was largely inactive, impersonal, and disengaged. He was barely active on Facebook—having posted only 73 times during the campaign period, in comparison to Binay's 509 and Poe's 244 posts. Duterte never replied to any comments or posts from fans. In sharp contrast to how Duterte presented himself in rallies and on traditional media, his most popular Facebook posts, reproduced in Table 2, were bland and impersonal.Footnote 8 Duterte posted mostly in the third person, suggesting that his campaign team did the writing and made a poor job of it. The posts lacked any of the tough-talking, pope-cursing style for which Duterte was famous and none capitalized on his viral YouTube videos. Duterte's Facebook page was, plainly speaking, boring and lackluster. In all categories, his rivals were far more active on Facebook. Grace Poe was a savvy campaigner: she posted her highly polished online campaign materials, with posters, slogans, and memes complete with sharing icons and hashtags. Binay was the active campaigner posting nearly fifteen times more often than Duterte. Santiago was the self-actualizing communicator—asking her supporters to engage with her online and frequently changing her background photos of herself with a group of young Filipinos in an apparent attempt to attract young voters. While most candidates conducted their social media campaigns in a top-down or interactive manner, Duterte's campaign was the only one that could cultivate the most engaged and active supporters despite being the least active, self-actualizing, and populist in comparison to his rivals. Our results seem to lend empirical support to the grassroots model of social media campaigning.

TABLE 2 Duterte's Most Popular Facebook Posts, 9 February–9 May 2016

Note: *popularity = highest interaction rate (likes, comments, shares)

While it seems that the bottom-up approach may explain Duterte's overwhelming grassroots support, the relationship between the candidate's campaign and his support base is less than clear. If Duterte the candidate was missing in action, then perhaps it was ordinary grassroots supporters who took it upon themselves to genuinely and voluntary mobilize support for their preferred candidate. We believe it would be naïve to assume that official campaign pages are either solitary islands or mountain peaks on the digital communications landscape. To be sure, there were hundreds of other, often informal, tribute sites and digital action groups set up alongside the official campaign, sometimes in coordination of traditional political actors, but often independently. Social media platforms like Facebook allow users to create “fan groups” or online communities that are necessarily the products of a candidate's social media efforts. During the campaign, for example, Facebook groups linking overseas Filipinos around the world proliferated and became venues for electoral campaigns of various presidential candidates.

Moreover, it is indisputable that the candidates benefited from these third-party platforms and vehicles. That being said, we have already shown that the Duterte campaign made little effort to connect to and network with these third-party activities. Insight into these decentralized supporters is thus necessary before drawing any conclusions about the extent to which the Duterte campaign was or was not involved with its digital fanbase. In the next two sub-sections, we explore these avenues using survey data on average netizens as well as a case-study of Mocha Uson, Duterte's most prominent online influencer.

Analyzing Facebook Users

The Duterte campaign's anemic social media presence is starkly at odds with the robust level of support his campaign received online. Why were Filipino Netizen's so active in their support for Duterte if he seemed hardly to notice their presence? The simple answer is that they were paid to be active. Yet, we also know that offline support for Duterte was remarkably strong as well (Arugay Reference Arugay2017), raising the possibility that at least some of the online fervor was genuine. To gain further insight into Duterte's digital fanbase and social media participation more generally, in 2017 we conducted a post-election survey of Filipino netizens. Generally, we were interested in the degree to which social media platforms played a role in voting decisions and in what way. More importantly, we were interested in whether or not Duterte supporters were systematically different from supporters of other candidates.

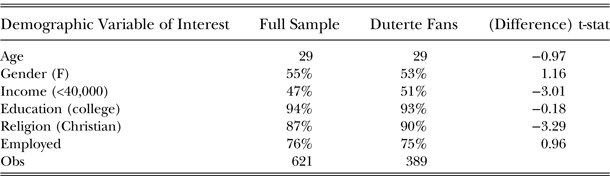

Our survey data comes from 621 online respondents recruited using a third-party service called Sampling Solutions International.Footnote 9 As with most online surveys, the sample is not representative of the general population. Moreover, because the survey took place a year after the actual election, it cannot be considered an accurate reflection of sentiments at the time of the actual ballot. Indeed, our sample suggests significantly more support for Duterte than what the electoral distributions produced in 2016. This partly reflects the “bandwagon effect,” of political support towards electoral winners (Atkeson Reference Atkeson1999), as well as increasing popular support for Duterte's administration which was hovering above 80 percent at the time of the survey. Instead, the sample reflects the online population more generally and is indicative of the type of voters who experienced the 2016 contest through social media. The typical respondent in our sample, as summarized in Table 3, is young, lower middle class, Christian, college educated, employed, and an active Facebook user. Their median age was 29 years old with a household monthly income of less than 40,000 pesos (US$750). This profile was similar to other existing surveys of the Facebook population in the Philippines (Kemp Reference Kemp2016).

TABLE 3 Respondent Profile

Note: The t-stat is based on a difference in means between Duterte supporters and non-Duterte supporters.

We evaluate Facebook importance via three subjective questions aimed at measuring a respondent's belief that Facebook was an Important platform during the campaign, that information found on Facebook Influenced their vote choice, as well as whether they generally Trust the information on Facebook. Overall, 85 percent of respondents “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that Facebook was Important, 70 percent thought Facebook influenced their vote, and a staggering 83 percent reported Trust in Facebook, “some” or “most of the time.” Looking across standard covariates in the only noticeable patterns are that younger voters were more likely to describe Facebook as “important” and “influential.” Unsurprisingly, more educated respondents seem less likely to find Facebook important, influential, or trustworthy, but the associations are not statistically significant. With respect to gender, women appear less trusting of Facebook, though they were statistically similar to men in terms of regarding Facebook as “important” and “influential.”

Finally, as a rough approximation of online participation, we explore the different ways in which respondents engaged with Facebook. For instance, although only 33 percent of respondents reported using Facebook to promote their preferred candidate, it is possible that they expressed their preferences in other ways, such as criticizing competing candidates or simply by sharing election-relevant posts within their networks. Accordingly, we asked respondents whether they ever shared or “liked” posts, posted their own comments, or published political messages on their profile walls. Overall, the only consistent association appears to be that older respondents are more likely to use Facebook to share, like, comment, and publish positive endorsements. The flipside of this relationship being that younger respondents were more likely to engage in negative behavior, targeting competing candidates.

Duterte's Digital Fans

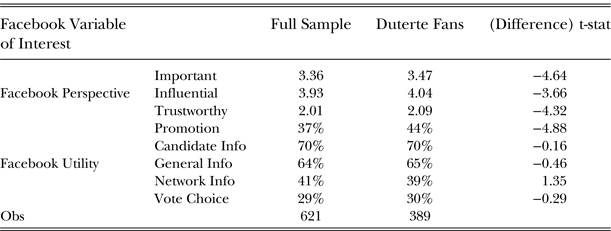

What do these general patterns reveal about Duterte's seemingly viral support base? By isolating Duterte voters from other respondents, we begin to see some notable differences.Footnote 10 In Table 3, for instance, we see that Duterte supporters in our sample are significantly poorer and more likely to describe themselves as “Christian” than the rest of the sample—demographic features which are consistent with qualitative accounts of Duterte's base as being relative poorer and religious, despite Duterte's hostility to the Catholic Church (Cornelio and Medina Reference Cornelio and Medina2018). In terms of Facebook utility, the second and third columns of Table 4 show that Duterte supporters were also far more likely to consider Facebook as Important, Influential, and Trustworthy than the supporters of other candidates. The activities engaged in by Duterte's fans were also somewhat different from supporters of other candidates. Whereas non-Duterte fans primarily used Facebook to gather general election news, read about candidates, and find out about what their friends are saying about the election, Duterte fans report using Facebook primarily to advocate and mobilize support for Duterte. In other words, whereas average netizens saw Facebook as a resource for making more informed electoral choices, Duterte supporters came armed with convictions and ready to fight for their champion.

TABLE 4 Facebook Utility

Note: Facebook Perspective variables are based on a five-point scale, with 0 representing none, and 4 representing most importance. The t-stat is based on a difference in means between Duterte supporters and non-Duterte supporters.

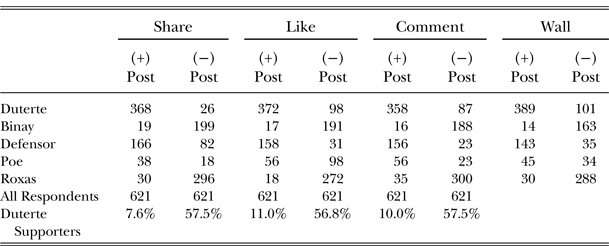

Unsurprisingly, Duterte supporters are also more deliberate in their promotion. Across our various measures of positive and negative interaction activity in Table 5, we observe that Duterte supporters were more likely to share, like, comment, and post positively about Duterte and negatively about other candidates. For instance, whereas only 50 percent of Binay supporters posted positive comments about Binay, roughly 84 percent of Duterte supporters did so. Likewise, whereas roughly 50 percent of Binay supporters also posted negative comments about Binay, only 8 percent of Duterte supporters said anything negative about Duterte.

TABLE 5 Facebook Activity

Note: Duterte supporters are identified based on the candidate they chose to promote on their Facebook Wall. The bottom row represents the positive (+) and (-) Facebook activities directed by Duterte supporters towards other candidates.

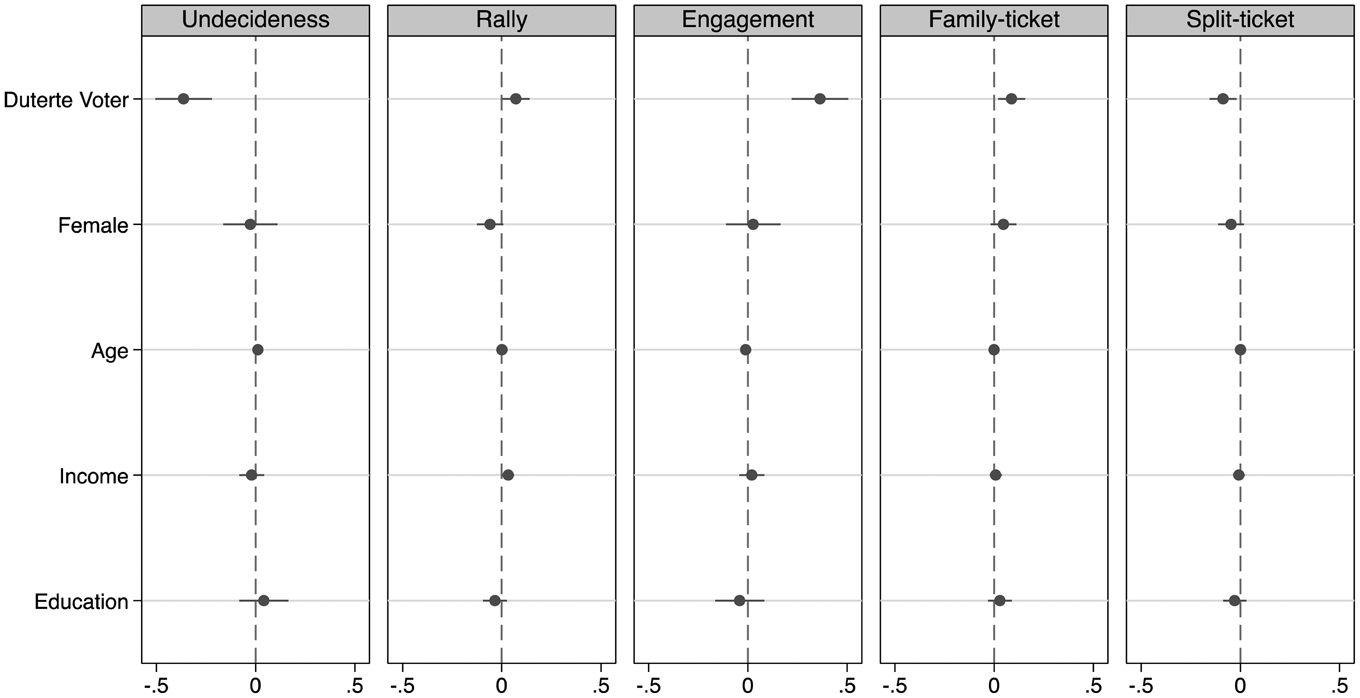

This kind of dedicated promotion was surely valuable for the Duterte campaign, but was it genuine or contracted? Certainly, paid trolls and boosters would have used Facebook exclusively to promote Duterte, which might explain our findings. However, this sort of contracted social media promotion should not travel to the offline environment. To put it simply, social media trolls do not vote, and they do not rally. Yet, that is exactly what we observe with respect to Duterte supporters in our sample, as summarized in Figure 3. First, Duterte supporters had also decided to support Duterte far earlier than other respondents. Duterte supporters were also far more likely to attend political rallies and to describe themselves as being more politically engaged than in the previous presidential election, and they were more likely to vote the same way as family members. At the same time, they were less likely to split their vote by choosing a candidate from another party for any of the other contests on the ballot, suggesting full devotion to Duterte. These findings suggest the Duterte's fan base was plausibly organic, voluntary, and zealously advocating for him.

FIGURE 3 Offline Engagement

Note: Duterte supporters are identified based on the candidate they chose to promote on their Facebook Wall. Undecidedness is based on when voters made their choice of who to vote for, ranging from 4–6 months before the election to the day of the election (most undecided). Rally is based on whether they participated in any political rallies. Engagement is based on self-reported engagement relative to the previous presidential election. Family-ticket is dichotomous, with positive values for anyone who voted the same way as a family member. Split-ticket voting refers to voting for president from one party and but voting for candidates from other parties for different seats.

The significance of our findings does not negate the possibility of paid support by Duterte and his team, but it provides an empirical confirmation that Duterte also had strong grassroots support. More importantly, the survey evidence shows that Duterte's fans were unique in the degree and methods of support for him they showed on Facebook in comparison with supporters of other candidates. Therefore, while Facebook was important to all the respondents in our survey when deciding to vote, only those supporting Duterte were using Facebook exclusively to advocate for him. Non-Duterte fans were not using the social media platform as a primary way to support their candidate. In addition, Duterte fans were the only ones active in offline rallies—suggesting that their commitment and endorsement went beyond a simple tap on a keyboard.

Grassroots Support or Influencers

Nevertheless, the role of intermediaries complicates our inquiry into top-down versus bottom-up modes of engagement. In particular, we have to accept the possibility that what seems like organic online mobilization might really be the product of paid-trolls and influencers hired and directed by the candidates. If that was the case, then it would perhaps be no surprise that Duterte's Facebook page was so anemic; his online campaign may have been playing a different ballgame altogether. To be sure, Duterte's online profile benefited greatly from social media influencers—individuals with the power to persuade others by virtue of their credibility, authenticity, and reach. Nic Gabunada, Duterte's social media campaign manager, even acknowledged having spent part of their budget on influencers and celebrities on Facebook (Gavilan Reference Gavilan2016), and some of these funds may also have gone to paid trolls and anonymous influencers. Moreover, as Ong and Cabañes (Reference Ong and Cabañes2018) demonstrate, the 2016 contest was flush with online political operators, media firms, and paid influencers, militarized by up to two million fake social media accounts set up to spread disinformation and mobilize public opinion (Ong and Cabañes Reference Ong and Cabañes2018, 13). Yet, as Ong and Cabañes point out, use of such services was widespread and not exclusive to the Duterte campaign. That being said, some of the most prominent influencers did happen to operate in the Duterte camp, and a closer examination of their background sheds additional light on the extent to which the campaign itself was orchestrating activities.

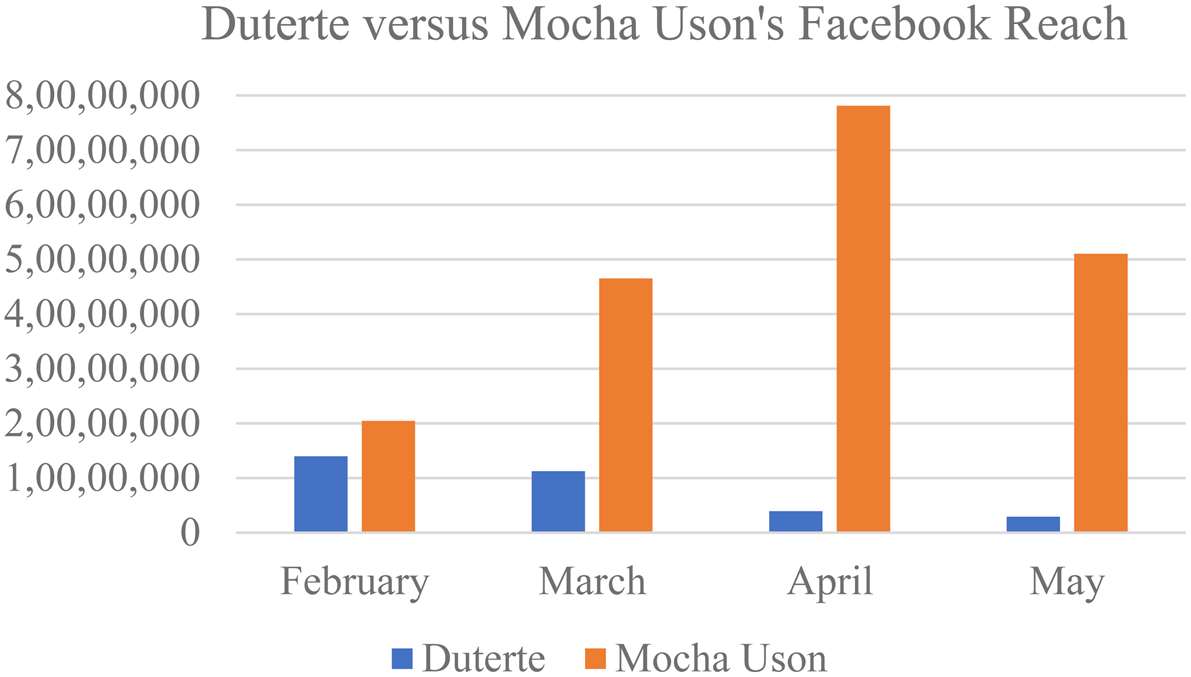

Consider the case of Mocha Uson, a former celebrity dancer and the most well-known digital influencer during the 2016 campaign period. Though Mocha eventually became an official member of Duterte's social media entourage, her entry into the Duterte fan base was highly instrumental and self-motivated.Footnote 11 Indeed, prior to attaching herself to the Duterte campaign, Mocha was at best a mediocre celebrity turned Internet personality; she used Facebook largely to promote her dance group, Mocha Girls, but rarely attracted much traffic or engagement from viewers. Once she started vlogging endorsements of Duterte, however, her online popularity sky-rocketed and her brand name became a lucrative asset. Yet, throughout the campaign period, up until the final month of the election, when Mocha was officially invited to join Duterte's media team, Mocha was firmly committed to promoting herself, never once linking her videos and endorsements to Duterte's web or Facebook page, redirecting all links instead to her own pages. Indeed, throughout the campaign Mocha's posts on Duterte outdid Duterte's campaign on a wide range of metrics: she posted three times more; had nearly four million shares, 4.3 million likes and over 600,000 comments. Upon further examination, we find that each time Mocha posted content related to Duterte, she reached six times more people than his own campaign did (see Figure 4), yet this massive audience was never directed towards Duterte's campaign itself.

FIGURE 4 Comparing Facebook Campaign Effectiveness between Duterte and Mocha Uson (Influencer)

Note: Because all of Mocha Uson's posts were videos, we calculated the number of viewers for all of Mocha Uson's Duterte-related videos and all of Duterte's videos during the official campaign period. “Reach” is calculated by the number of people who viewed each video. A color version of this figure is available in the online version of this article.

Mocha's case is admittedly peculiar, but the notion that intermediaries act on their own accord and in their own self-interest in support of political candidates is hardly new. Indeed, future electoral contests are bound to be complicated by an increasing range of informal social media actors who now have an efficient platform from which to influence political outcomes. Seen from this light, debates over top-down versus bottom-up campaign strategies seem antiquated. To be sure, the growing ambiguity will make it harder for researchers to pinpoint the strategic logic behind social media campaigns and elections, but this does not mean we cannot draw meaningful inferences how social media is likely to impact future contests. As Jamieson (Reference Jamieson2018) argues in her review of social media interference during America's 2016 presidential election, Trump supporters were uniquely susceptible to social media messaging in part because the candidate channeled their sense of cultural and economic insecurity (p. 119). Likewise, Russian interference was effective mainly because it worked to amplify those sentiments and coordinate them across platforms and networks.

In similar fashion, our review of the 2016 Philippine presidential election indicates that social media served mainly to amplify and exploit the existing groundswell of support for a tough-talking, populist who catered to the emotions and frustrations of a major part of the electorate taken for granted by the country's political establishment (Teehankee and Thompson Reference Teehankee and Thompson2016, Curato Reference Curato2016). These supporters, some calling themselves “Diehard Duterte Supporters (DDS),” were willing to look past Duterte's faults, and actively helped to propagate disinformation campaigns against Duterte's opponents. They went out of their way to express their support, and many even “trolled” his critics voluntarily. Some of these actors, like Mocha, had obvious self-interests motivating their behavior, but many, like those in our survey, appear to have done it voluntarily. The supporters printed their own Duterte t-shirts, decorated their cars and license plates, and organized community events to showcase their love for Duterte (Ranada Reference Ranada2016). Importantly, however, the broad base of fanatical support for Duterte was not the product of a calculated social media strategy. Indeed, grassroots enthusiasm for Duterte existed prior to his official campaign, and is easily observed in pre-election surveys as early as 2014 (Holmes Reference Holmes2016). By late 2015, when he launched his official campaign, Duterte was already a social media favorite.

CONCLUSION

With the rapid proliferation of digital platforms and outreach tools, one might be forgiven for discounting the role of physical connectivity in modern political campaigning. The hundreds or thousands of voters that might be moved by a successful street canvas or rally, for instance, pale in comparison to the millions that could be influenced by a viral meme or tweet. Similarly, it might seem natural to conclude that online political savvy is now a prerequisite for electoral success offline. Our analysis of campaigning and social media activity in the Philippines complicates this interpretation. On the one hand, our analysis confirms that Facebook played a critical role in the 2016 Philippine presidential election, and that Rodrigo Duterte dominated the Facebook frontier. At the same time, we find little evidence to suggest that Duterte or his campaign deserve much of the credit for their social media success.

From a supply-side perspective, Duterte's Facebook presence was underwhelming, unengaging, and generally unprofessional. Not only was Duterte's official campaign page anemic in its output, it failed to capitalize on or amplify the media buzz that surrounded the candidate. Observationally speaking, it seems as if Duterte's campaign either did not know how to make use of Duterte's Facebook presence or simply did not care. And yet, despite the ineffective management, Duterte's official Facebook page quickly emerged as a center of attention and reference for social media users in the country. Much of this was thanks to vocal digital supporters who cheered his mundane statements and rallied to his defense when competing candidates voiced criticism.

Conventional interpretations of digital campaigning that focus on the strategy of political candidates cannot explain the degree of digital fervor that backed Duterte's bid for power. Yet, while we can be sure that Duterte's digital campaign was not a purely top-down effort, it is unlikely to have been entirely grassroots driven either. Informal actors, including paid trolls and influencers, inevitably played some role in mobilizing and agitating digital communities. Nevertheless, our results also point to distinct patterns of behavior among Duterte supporters that are consistent with a deeply enthusiastic fanbase, one that took advantage of social media rather than simply being taken advantage by it. For instance, our survey findings suggest that Duterte supporters had made up their electoral minds far earlier than supporters of other candidates, they were more likely to attend rallies and agitate offline, and when it came to election day, they were more likely to vote in groups and split their down-ballot if necessary so as to support Duterte without compromising their local preferences. Once online, these same supporters were not interested in more information, they logged on to advocate for Duterte and attack his critics.

These ardent fans, alongside bots, trolls, and influencers, represent a broader, less structured, and less formal social media ecosystem, and one that is becoming increasingly difficult to study. Our findings make a small contribution, but they are by no means comprehensive or conclusive. In our attempt to model top-down strategy, we arguably focus too heavily on official Facebook pages. Future research will likely have to adopt more nuanced concepts about what campaigns look like, who is involved, and what kind of tactics are in play. Our reliance on post-election survey question likely involve some embellishment on the part of Duterte supporters. We may even have inadvertently surveyed some paid supporters. Yet, it would be wrong to write off the observed enthusiasm in both Facebook activity and survey responses as being entirely fabricated. Indeed, had Duterte's support not been at least partially genuine in 2016, how do we make sense of his and his party's soaring popularity and electoral support since? Social media and digital support, as chaotic as it is, remains a critical arena for modern political competition and confronting questions of agency and authenticity with an open mind will be crucial if scholars hope to understand and anticipate future contests, as well as for practitioners and administrators tasked with safeguarding democratic institutions.

These thoughts ring particularly true with regard to polities that have received far less attention by existing scholarship. For instance, whereas most contemporary literature on social media and politics has focused on advanced democracies with established modes of political contest, a large portion of the electoral world is still developing, politically unconsolidated, but remarkably well wired and networked. In these settings, social media platforms like Facebook might be most relevant in terms of harnessing and augmenting existing grassroots movements. They may also embody some of the fluidity and chaos of offline politics. In the Philippines at least, Facebook mobilization produced a notably toxic and crude digital fan base that reflected and amplified the insurgent and brutish personality of its champion.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Aim Sinpeng, Dimitar Gueorguiev, and Aries A. Arugay declare none.