Introduction

Post-neoliberalism is a philosophy and movement that represents a backlash to the laissez-faire economic policies, privatisation, fiscal austerity, deregulation, free trade and state reduction promoted by the Washington Consensus. While neoliberalism sought to ‘thin’ many aspects of the state and strengthen the non-interventionist market economy, post-neoliberalism advocates wealth redistribution by the state and asserts the state's central role in planning and development. This has certainly been true in Ecuador. Between 2007 and 2017, Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa undertook a series of post-neoliberal counter-reforms, strengthening the state, increasing its regulatory and economic planning power, and broadening its social influence, as a means of promoting his government's ambitious plan of buen vivir, or ‘good living’. As in other countries, Correa's project of political, economic and social transformation was possible only through a profound process of institutional reform. How exactly did the Ecuadorean government pursue its post-neoliberal project, and what generalisable lessons does Ecuador's experience teach? Further, what does this experience say about the process of institutional change outside advanced industrial democracies?

Scholarship on post-neoliberalism tends to focus on the economic consequences of the Washington Consensus, especially privatisation, deregulation, trade liberalisation, the role of social actors opposed to neoliberalism, and the subsequent rise of the New Left. However, the majority of this literature has not examined the counter-reform of the state in a bureaucratic-institutional sense. We contribute to this literature by arguing that institutional reform is a necessary prerequisite for post-neoliberal economic and social change. Although some scholars have analysed constitutional reforms in post-neoliberal contexts,Footnote 1 with the exception of Catherine Conaghan,Footnote 2 they have not concentrated on constitutional reform as an economic or social tool. Jean Grugel and Pía Riggirozzi,Footnote 3 for instance, explain change in post-neoliberalism's economic model and renewed attention to social demands as a paradigm shift for society in the role of the state and its development model. However, they focus on describing the return of the state and the tenets of post-neoliberalism in Latin America without defining the specific instruments that these governments have used to achieve their goals. We address this lacuna here.

Our central contribution is to show that, just as state reform was necessary for the implementation of neoliberalism, institutional reform is also a necessary prerequisite for post-neoliberal economic and social change. Building on the framework established by neo-institutional scholars, we argue that there are four preconditions for governments to pursue the economic and social change of post-neoliberalism: (1) state transformation through legal-constitutional change; (2) empowerment of a national planning office to manage developmental policy; (3) growth of the size and capacity of the state; and (4) government revenue to make the previous steps possible. Regardless of its sustainability, we maintain that post-neoliberalism is a model of structured transformation driven by social sectors and politicians, and not merely a secondary effect of the commodities boom of the late 2000s and early 2010s.

To show this, we draw attention to the way President Correa changed the role of the state in Ecuador from minimal to omnipresent, and we analyse the tools used by his government to do so. These included: the adoption of a new legal-constitutional framework to legitimise state policies; the establishment of a planning body to develop, manage and oversee the role of the state in economic and social affairs; and the growth and reorganisation of the public sector to add new employees and agencies and improve state capacity. Although the impetus for post-neoliberalism was independent of an increase in government revenue, we also show how the commodities boom, increased tax income and a substantial increase in government spending made many of these changes possible.

This argument indicates that the sustainability of post-neoliberalism depends on an appropriate combination of political willpower and economic fortune. First, dependency on a centralised planning agency is entirely at the discretion of the politicians in power. A change in political administration could easily disrupt the predominant developmental paradigm. A new president may even seek legal-constitutional changes to undo the state transformation of post-neoliberalism. Second, this paradigm is likely to be limited in places where commodity dependency and fickle international markets cannot guarantee sufficient government revenue to sustain a large state or offer civil service salaries large enough to draw talent away from the private sector. The legal-institutional framework and state planning agencies would remain – at least for a short while – but without any guarantee that the bureaucracy would be able to carry out their directives. Lastly, since the post-neoliberal experiment requires not only reorganisation of the administrative apparatus but also high state capacity, challenges to this capacity through factors like corruption may also threaten its continued viability.

Beyond Neoliberalism

‘Post-neoliberalism’ is a term scholars have used to classify a range of development models proposed by governments and discontented citizens in Latin America as a response and alternative to neoliberalism.Footnote 4 Grugel and Riggirozzi define it as a set of political aspirations centred on reclaiming the authority of the state and a body of economic policies to rebuild the capacity of the state to manage both the market and citizens’ demands.Footnote 5 Although it maintains elements of neoliberalism's export-led growth model, post-neoliberalism also advocates wealth redistribution by the state and asserts the state's central role in planning and development. Indeed, post-neoliberalism marks a re-conceptualisation of the state, based on a view that governments have a moral responsibility to respect and deliver inalienable citizens’ rights alongside economic growth. As such, this developmental paradigm incorporates elements of embedded liberalism and neoliberalism, as well as post-materialism. In fact, it goes beyond facile state-versus-market paradigms to consider ways in which the state and market may complement each other.

Existing scholarship on post-neoliberalism tends to focus on its roots, specifically the backlash against privatisation, deregulation, trade liberalisation and other elements of the Washington Consensus;Footnote 6 the social actors involved in advocating for and sustaining change;Footnote 7 and the policy consequences of this new developmental paradigm.Footnote 8 Some scholars focus on the backlash against neoliberalism and why certain social sectors and groups in some countries oppose the market economy more than others.Footnote 9 Eduardo Silva, for instance, argues that neoliberal contention depends on the development of group associational power, as well as the creation of horizontal linkages between new and traditional social movements.Footnote 10 Others, meanwhile, grapple with the variety of responses to neoliberalism and examine their compatibility with it.Footnote 11

One commonality among all of these works is that they view post-neoliberalism not as a single process but as a diversity of national growth models. Just as neoliberalism is a diffuse collection of measures,Footnote 12 its conceptual counterpoint is similarly segmented. Nicola Seckler sees it as a multi-front struggle waged by distinct social groups against axiomatic neoliberal positions, while Francisco Panizza argues that there are a variety of manifestations of post-neoliberalism, from grass-roots protests to top-down populist mobilisation and institutionalised forms of representation.Footnote 13 While these descriptions and analyses are well explored, the literature on the institutional preconditions of post-neoliberalism is weaker.

For example, what makes the implementation of post-neoliberalism – not just the contention of neoliberalism by social groups – possible at a political level? What institutional changes are necessary? With few exceptions, the existing literature has not examined the counter-reform of the state in an institutional-bureaucratic sense as a prerequisite for the application of post-neoliberalism. Laura Macdonald and Arne Ruckert propose that post-neoliberalism is characterised ‘mainly by a search for progressive policy alternatives arising out of the many contradictions of neoliberalism’, although Macdonald, Ruckert and Proulx also recognise there is no clear consensus.Footnote 14 Building on existing theoretical frameworks for neoliberal state reform, we argue that one commonality beyond merely adopting policy alternatives is that post-neoliberalism requires profound institutional change. However, whereas neoliberalism sought to adapt the state's structure and function to a market economy and liberal democracy by shrinking many of its features, post-neoliberalism seeks institutional change to grow the size of the state.

Following Wolfgang Streeck and Kathleen Thelen,Footnote 15 we understand institutional change to be a transformation in the purposes, roles and capacities of political economic institutions. This is especially true of state infrastructural power, the state's capacity to penetrate civil society and then to use this penetration to enforce policy throughout its entire territory.Footnote 16 Unlike policy adjustments that are the fruits of the legislative process involving parties, deliberative courts or organised interest groups, institutional change is characterised by a shift in both the quality and quantity of state interaction with social life, including all efforts made by the government to transform its organisational structure, with the goal of improving its capacity to control or intervene in political, economic or social affairs.

Like the movements towards post-structuralist developmentalism in the 1960s and 1970s, or neoliberalism in the 1980s and 1990s, post-neoliberalism certainly fits the definition of institutional change. All three movements represent conscious shifts in the state's developmentalist paradigm and its fundamental relationship to the market and society. This type of deliberate transformation, which Streeck and Thelen call ‘conversion’, represents the redeployment of old institutions to new purposes and requires coordinated government planning and favourable political and economic circumstances.Footnote 17 The level of coordination also depends on the type of institutional change being pursued. In one sense, increasing the size of the state should be more difficult than decreasing it, since the former requires sufficient public money while the latter does not. However, as Paul Pierson points out, shrinking the state may also be challenging, since institutions in the social welfare state may be subject to lock-in effects, whereby each client creates additional vested interests in maintaining the system.Footnote 18 Popular mobilisation may result, meaning that shrinking the state may also require a great deal of coordination and compromise between the government and social actors.Footnote 19

Tools to Bring the State Back In

While group associational power or the creation of horizontal linkages between social movements may help determine where post-neoliberalism emerges as a viable policy, institutional change requires bureaucratic transformation and an increase in state capacity. We argue that among post-neoliberalism's necessary, but not independently sufficient, prerequisites are: (1) an adequate legal-institutional framework to support the state's policies; (2) the empowerment of a planning body to make these policies; and (3) the creation of a bureaucratic structure large enough and diversified enough to successfully implement and regulate these policies. These three elements are necessary because the institutional conversion that characterises post-neoliberalism requires coordinated government planning and favourable political and economic circumstances in order to adapt existing institutions to serve new goals or new actors’ interests.Footnote 20

The first step, legal/normative alteration, is not unique to post-neoliberalism: scholars agree that neoliberalism requires constitutional-legal reforms to give politicians the tools to shrink the state, promote privatisation and deregulation, and implement a legal framework to prevent the reforms from being easily dismantled (such as Carlos Menem's Law 23.696 of State Reform in Argentina).Footnote 21 The same goes for post-neoliberalism, but in the opposite direction. Legal changes allow political leadership to give more power to actors it deems relevant, while they may also reflect a new social consensus. Such reform is necessary, since institutional change may be legally or constitutionally prohibited. Failing to first undertake these constitutional changes could result in challenges in court, in the legislature and, perhaps most worrisome for governments, in the streets.

The second step, the creation or empowerment of a planning body and expansion of the public administration, separates post-neoliberal change from classical liberalism or neoliberalism. While neoliberalism shrinks the state, post-neoliberalism grows it. This is evident in the differing roles of planning agencies. Technical teams exist under neoliberalism, but they are few and primarily used as a demolition team to lessen the role of the state.Footnote 22 By contrast, they flourish under post-neoliberalism as the state requires a body to design its policies and execute its project. From the president's perspective, it is more politically efficacious to utilise a centralised agency with little insulation from the president that can design developmental policy consistent with the political elite's vision. Most often, this body assumes the form of a planning agency. However, regardless of type, any post-neoliberal project that promotes greater state interventionism in society and the market will require a policy-making body.

For the third step, in order to implement desired changes, state reformers require an apparatus large enough to execute or implement their development project. Again, this is not necessarily true for the neoliberal model, where the market in many respects replaces the public sector as policy executor, essentially shrinking the public sector. However, increasing the role and importance of the state necessitates a large and strong bureaucracy – which means creating a larger and more capable state. To accomplish this, the government must increase public spending, add new employees (and agencies) to the public sector and otherwise reorganise the public administration to meet its new policy needs. If any one of these three steps fails (legal foundation, planning agency, growth of bureaucracy), then the larger project also stalls.

As a last necessary condition, the government must enjoy sufficient resources to finance not only the developmental policies but also the growing public administration needed to implement them. Without adequate revenue, governments will find it hard to increase the size of the state or its role in social and economic life. This differs substantially from implementing an orthodox neoliberal political economic model, which may require a legal basis for action but not a large planning body or bureaucracy, and whose success does not depend on fortuitous economic circumstances. And while this should be a necessary condition for undertaking post-neoliberalism, it is not an independently sufficient one, since many wealthy governments around the world do not pursue this model of development. While not independently sufficient, adequate government revenue, an appropriate legal-constitutional framework, a planning body and a larger bureaucracy are jointly sufficient conditions for post-neoliberalism.

Other factors, such as a concentration of power in the figure of the president, state control over other branches of government or an increase in social welfare spending, may help determine the modality of institutional change; however, none is a necessary or sufficient condition for post-neoliberalism's success. For instance, there are many governments throughout the world that cannot be called post-neoliberal where constitutions concentrate power in the executive, where the president enjoys control over other branches of government or where the government makes social spending a priority. In fact, a concentration of power in the executive is characteristic of a wide variety of state-building projects and developmental paradigms, from embedded liberalism (Juan José Arévalo, for example) to neoliberalism (Menem and Alberto Fujimori, for example), and unique to none. Similarly, a dedication to social spending and growth through a combination of market and state is more characteristic of Scandinavian-style socialism than the recent autochthonous development projects of Latin America. However, the concentration of power in the executive in many non-advanced industrial democracies suggests that institutional change might be less constrained and therefore more sudden than scholars suggest.

Rafael Correa's Ecuador

To demonstrate how the legal framework, reliance on planning, and growth of the state are necessary tools for the post-neoliberal paradigm, we study the presidency of Rafael Correa and his Alianza Patria Altiva I Soberana (Proud and Sovereign Fatherland Alliance), also known as Alianza PAIS (Country Alliance), in Ecuador (2007–9, 2009–13, 2013–17). The Correa administration's anti-neoliberal Constitution (combined with constraints on freedom of speech and neo-extractivist policies) polarised both the RightFootnote 23 and the social-movement Left,Footnote 24 but its institutional and political break with the past is undeniable. The president and his administration were able to reverse many of the country's neoliberal state policies while undertaking a unique statist development project.

Our goal in focusing on a single case is to provide greater description, explicative detail and intension than would be possible with a small-N comparison of three or four countries (or, needless to say, a larger-N study). We chose Ecuador in part because it fits what John Gerring calls a representative ‘pathway case’.Footnote 25 Ecuador's experience has been unlike that of Argentina and Brazil, which are federal states, or Bolivia, where there has been a greater degree of opposition to post-neoliberal reforms. In what follows, we describe Ecuadorean post-neoliberalism, then highlight the tools that allowed the president to pursue this project.

A Return to the State in Ecuador

Ecuador's post-neoliberal project is a response to its neoliberal antecedents. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Ecuadorean political and economic elites adopted various degrees of neoliberal reforms, reducing the state's interventionist power. Beginning in 1984, successive governments shrank the public sector and attempted privatisations of telecommunications, highways and electricity, deregulation of the financial sector and labour market, and other state reforms consistent with the Washington Consensus.Footnote 26 Although not as complete or extreme as the neoliberal shock reforms instituted in Argentina, Brazil, Peru and Venezuela, nor as dependent on privatisations as those economies, these policies still managed to generate substantial opposition from certain social sectors, resulting in various moments of social protest and political instability.

On top of this, a weakly representative political party system provided many groups with limited channels for formal political contestation. Frustrated by its lack of political representation and low government responsiveness, the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) emerged as a socio-political actor. In June 1990, CONAIE launched a massive levantamiento (uprising), shutting down the country for a week and forcing the government to negotiate, also staging similarly large uprisings in 1992 and 1994. In conjunction with political elites and the military, social groups played a key role in helping to remove three consecutive elected presidents from office. Workers’ syndicates, indigenous groups and others marched against Abdalá Bucaram in 1997; CONAIE was a protagonist in the coup against Jamil Mahuad in 2000; and the middle-class (and later indigenous) forajido movement helped push congress to take action to remove Lucio Gutiérrez in 2005.Footnote 27 It was in this context that voters elected political outsider Rafael Correa in November 2006.

Correa campaigned on a left-wing platform of social, political and economic change, through his Revolución Ciudadana (Citizens’ Revolution) and the Plan Nacional de Buen Vivir (National Plan for Good Living, PNBV). According to former Foreign Minister Ricardo Patiño, the Revolución Ciudadana is a socialist process based on a supportive economy and more equitable wealth redistribution, as well as one that privileges production and attacks speculation – goals that could perhaps be achieved through policy change and minimal alterations to the state itself.Footnote 28 However, the national development policy of buen vivir, or ‘good living’, based on the Kichwa concept of sumak kawsay (and analogous to existing indigenous cosmovisions in Bolivia, Peru and elsewhere), requires profound institutional change in the way it proposes to repurpose existing institutions.

Buen vivir describes a way of social and political life that is community-centric, ecologically balanced and culturally sensitive, and it focuses on development around living well, rather than merely orthodox Western visions of modernisation.Footnote 29 One of its central tenets is that the state must play a larger role in economics, politics and society. Beyond this, Ecuador's version of post-neoliberalism reflects ample debate within the country, perhaps likewise reflecting post-neoliberalism's multitudinous roots.

Alberto Acosta, the 2008 Constituent Assembly president turned government critic, presented buen vivir as the continuation of a search by popular movements for alternative, particularly indigenous, forms of development, representing a new way of life and a vision of ‘harmonious living from the periphery’.Footnote 30 Correa acolyte René Ramírez argues that it means: ‘free time for contemplation and emancipation, and the broadening or flourishing of real liberties, opportunities, capacities, and potentialities of individuals/collectives to bring that which society, territories, diverse collective identities, and everyone – as a human being or collective, universal or individual – values as key to a desirable life …’Footnote 31

By contrast, ex-Secretary of Planning Fander Falconí proposes a dichotomous model that oscillates between ‘twenty-first century socialism’ and a classical, inclusive developmentalism.Footnote 32 He adds that these models possess common characteristics; although twenty-first century socialism has disrupted the bases of political power through constitutional reforms, like the classical development model it emphasises the need to transform the economic structure, and to incorporate topics such as the environment, a new conceptualisation of development and plurinationality. In other words, rather than representing a well-defined policy, development model or way of life, buen vivir is a catch-all term that denotes a type of development that deviates from the neoliberal status quo.Footnote 33

These visions of the state are common in Latin America, especially among structural Marxists who argue that the state is an essential element of capitalist hegemony.Footnote 34 They incorporate elements of Latin American developmentalist thinking, which conceives a state model oriented towards selective economic interventionism to promote a rapid accumulation of capital and industrialisation.Footnote 35 This model argues that the acceleration of underdeveloped economies is not a spontaneous phenomenon that results exclusively from market forces, but is the result of vigorous state involvement in strategic sectors through planning, structural reforms and the promotion of vigorous industrialisation in the context of a mixed economic system.Footnote 36

This amalgamation of strategies is clearly reflected in the objectives of the Revolución Ciudadana. This model suggests that the ideal state is based on a planning system that allows the economy to satisfy people's basic necessities through a wide range of interventions. Although the economy is not completely planned, the market takes a secondary role to strong state guidance. Further, one of the fundamental purposes of the state is to promote economic development, not just from a political economic perspective but also by establishing an adequate developmental model for each phase of socialism.

Consequently, the post-neoliberal model proposed by the Ecuadorean government is similar to the developmentalist model, insofar as it considers the state to be a central protagonist in economic and political planning processes. It differs, however, through the inclusion of post-materialist elements, such as respect for human diversity and the environment. The Revolución Ciudadana also seeks to include ‘democratic components of the state’, where democracy is plebiscitary and majoritarian rather than liberal and pluralist, and where leaders and projects gain legitimacy through national referenda and winner-take-all elections.

Yet this model contains a number of internal contradictions. One is the tension between the predominantly extractivist economic model and constitutional protections for the environment (through the concepts of ‘Pachamama’, or ‘biosocialism’). Another contradiction is that of popular participation versus technocratic expertise, since the former does not lend itself to technical solutions, while the latter represents a vision of limited political participation.Footnote 37 This ‘technopopulist’ proposal incorporates the importance of charismatic leadership so common in definitions of classical populism, while depending on government technocrats to form and implement policy following the rational instruments of science and technology.Footnote 38 Planning therefore becomes the jurisdiction of experts rather than politicians, gaining legitimacy through its scientific pretensions and supposed representation of all citizens rather than disparate individual interests.

The ‘Counter-Reform’ of the State through the Montecristi Constitution

One of the principal elements to pursue state reform is establishing the requisite legal-constitutional foundation to either remove the state from economic and social affairs (classical liberalism, neoliberalism) or integrate it into them (embedded liberalism, post-neoliberalism). Doing so allows politicians to change the status quo and provide the political, social and economic project with institutional footing and legitimacy. Beyond playing a symbolic role in national re-foundation and plebiscitary ratification of presidential proposals, this process allows a government to mould a new political-institutional order. As Detlef Nolte and Almut Schilling-Vacaflor point out, this has been a strategy pursued throughout Latin America.Footnote 39

In Ecuador, Correa convened a Constituent Assembly immediately upon election in 2007 in order to change the rules of the game. The country's sprawling 2008 Montecristi ConstitutionFootnote 40 created a strong, interventionist state that used planning as a lynchpin in the national economy and public management system.Footnote 41 It also marked a sharp contrast to constitutional reforms carried out during the 1980s and 1990s that reduced the state's rigid institutional control over certain strategic sectors and political economic processes. For the first time, the Constitution recognised a wide catalogue of individual, collective and historical rights and guarantees. It also incorporated the rights of nature and respect for other cosmovisions, and integrated the concept of buen vivir as a basis of rights and the central axis of the country's development model (Articles 71–4). The need to guarantee and enforce these rights meant giving the state greater political and institutional capacities.

Other fundamental characteristics of the neoliberal model were retracted or limited, as demonstrated by changes to Central Bank independence, labour liberalisation and free trade. The 1998 Constitution guaranteed Central Bank independence by delegating to it certain tasks and giving it an administrative structure in which the government played no role.Footnote 42 Correa was highly critical of this set-up, especially the supposed lack of democratic legitimacy in the Central Bank's decision-making, and the lack of control over monetary policy.Footnote 43 As a result, one of the government's chief goals with the 2008 Constitution was the recovery of monetary, credit, exchange rate and financial policy formulation, all of which became exclusive faculties of the executive branch (despite a dollarised economy).Footnote 44 The Central Bank, meanwhile, was relegated to an instrument of the executive.

The Constitution also modified labour flexibilisation, another key aspect of the neoliberal agenda, by creating a framework in which the state plays a more active role in its regulation. Prior to the 2008 Constitution, the National Constituent Assembly published Order No. 8, which prohibited outsourcing and some forms of hourly contracts. Article 327 of the new Constitution explicitly prohibits ‘forms of job insecurity and instability’ inherent in the neoliberal model of labour flexibilisation, determining that the relationship between workers and employers must be ‘bilateral and direct’.Footnote 45 It blocks labour brokerage and outsourcing by an enterprise or employer for core activities of their business, hourly contracting and any other form of employment that violates the individual or collective rights of workers.

Furthermore, it regulates international trade by making commercial agreements more difficult to negotiate. Article 422 prohibits any treaty or international instrument in which the Ecuadorean state cedes sovereign jurisdiction in matters of international arbitration, in contractual controversies or commercial matters, or between the state and natural or legal entities. Consequently, in contrast to other countries in the region, Ecuador does not rely on a free trade agreement (FTA) with the United States, and it held out on brokering one with the European Union until the beginning of its economic recession in 2014.Footnote 46

The Constitution also explicitly established the president as the most important actor in developing and promulgating the country's post-neoliberal National Development Plan. Article 147 defines 18 presidential responsibilities, including ‘to submit to the National Planning Council the proposal for the National Development Plan’ (subsection 4); ‘to direct public administration with a decentralised approach and to issue the decrees needed for its integration, organisation, regulation and monitoring’ (subsection 5); and ‘to create, change, and eliminate coordination ministries, entities and bodies’ (subsection 6). In short, the Constitution gives the president the power to dictate and define the country's National Development Plan, to organise executive agencies to carry out that plan and to determine the precise role that distinct government bodies will play in that plan. This is not merely academic: between 2007 and 2014, Correa issued 4,200 presidential decrees, nearly two-thirds of which pertained to administrative issues or the public administration.Footnote 47

Further legal changes and political manoeuvring reinforced the Constitution while limiting political and social veto players. Notably, the government pursued a number of policies, aimed at the media, civil society organisations and higher education, which enlarged the scope of regulation and enhanced the powers of the executive branch.Footnote 48 In June 2013, the National Assembly passed the Organic Law on Communication, a controversial measure that subjects public information to government oversight and regulation through the newly created Superintendency of Information and Communication (SUPERCOM). In the same month, Correa issued Presidential Decree No. 16, which establishes strict government control of the structure and activities of all social organisations, while circumscribing their political participation. While a weak and fragmented political oppositionFootnote 49 and a lack of judicial independenceFootnote 50 do not proactively require increased regulation or state intervention, they limit opposition to policy planning and implementation.

In sum, the Montecristi Constitution marks a shift from legal norms guaranteeing certain aspects of the neoliberal agenda to difficult-to-change constitutional laws increasing state planning, intervention and regulatory power, all while placing politics above the economy. Subsequent laws have fortified these rules. These legal and constitutional changes do not only codify the new state, but also institutionalise the changes to ensure they endure beyond a single president or congress.

A Return to the Planning State: SENPLADES

The second major step in promoting post-neoliberalism is the empowerment of a national planning office or other bureaucratic body to advance, manage and oversee developmental policy. This planning body is necessary for three reasons. First, unlike market-oriented plans that operate under the assumption that the state is incapable of making vast decisions in an objective and rational fashion, post-neoliberalism requires an instrument of intervention. Post-neoliberal state management of the economy and society requires sufficient state capacity to design, implement, evaluate and adjust a variety of policies. Second, the instrument needs to be technocratic, since this type of planning understands policy-making as the product of technical rather than political debate and therefore limits the validity of ideological or political disagreement and dissension.Footnote 51 However, unlike neoliberal technocrats with links to private financial institutions and international organisations, post-neoliberal technocrats come from academia and non-governmental organisations.Footnote 52 Third, this bureaucratic body within the executive branch is not beholden to the types of opposition lawmakers and other veto players that could thwart or significantly alter the policy.

The change in the role of planning offices over time in Ecuador is illustrative. The conservative government of President Sixto Durán Ballén (1992–6) made a great effort to implement neoliberalism and improve what the president deemed the ‘shameful structure of privilege of the inefficient public sector’.Footnote 53 Perhaps the most consequential of that administration's market-oriented reforms was the Law of State Modernisation, which permitted the state to privatise potable water, sanitation, electricity, telecommunications, roadways, port facilities, airports, train stations and the postal service.Footnote 54 The law also created the National Council for the Modernisation of the State (CONAM), a planning body affiliated to the presidency that sought decentralisation, divestment, privatisation and neoliberal state reform in general.

There was little participation by subnational governments, autonomous entities or social organisations in planning, and by the mid-1990s CONAM's role practically disappeared as a result of changes in the law and the reduction of the state. Large-scale development plans from the pre-neoliberal era were diluted into small-scale investment goals, objectives and tendencies incomparable in scope or ambition. Befitting its reduced use, the 1998 Constitution eliminated CONAM altogether and created the Office of Planning (ODEPLAN), a smaller technical body affiliated to the presidency. In 2004, President Lucio Gutiérrez transformed the body into the Secretaría Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo (National Secretariat of Planning and Development, SENPLADES) – an agency that shares a name with the current planning agency, but that had radically fewer responsibilities. All of this changed with the election of Rafael Correa.

The Correa government's PNBV is an ambitious national strategy that situates the state at the centre of national development. Article 280 of the Constitution establishes that the PNBV: ‘is the instrument to which public policies, programs and projects, the programming and execution of the State budget, and the investment and allocation of public resources shall adhere. It shall coordinate the exclusive areas of competence between the central state and decentralised autonomous governments …’Footnote 55 In other words, the PNBV reasserts planning as a political space for public policy design and a manifestation of the state's new interventionist capacity, setting out guidelines for the state to reinsert itself into the country's political and economic (if not social) policy.

The institution in charge of reforming the state apparatus, training public servants and writing the PNBV is the National Planning Council and its technical secretariat, SENPLADES. Since state public policy must be aligned with the objectives set out in the PNBV, SENPLADES is fundamental to Ecuadorean post-neoliberalism. Through the PNBV, the agency helps to carry out the state's economic plan, as well as wide-ranging policies in the domains of labour, social affairs, justice and global affairs. In particular, its foundational documents emphasise the institutional representation of society and define the reach of public goods provision to achieve efficiency and the sustainability of buen vivir. This gives the state a prominent role in the direction of the economy, as well as in planning, investment and redistribution.

Success has been more evident at the national level. In many ways, the PNBV has been more effective as a mechanism of control (via access to resources) than in achieving its myriad goals. On the one hand, as a bureaucratic agency above the other ministries in the organisational hierarchy, it dictates the framework under which public investment projects can seek funding via SENPLADES. However, the PNBV's local effectiveness has been mixed. While national poverty has decreased and health and education have improved, José Prada-TrigoFootnote 56 uses fieldwork in three Ecuadorean cities to show that social participation in many places remains low, and that real change in local administration and governance through the PNBV has been at best limited. What is more, he finds that local officials in charge of implementing the PNBV often have limited knowledge of the territory, staff rotation is often high, and there are no associations to link the local and supralocal administrations.

At the national level, however, the government staffed SENPLADES with some of the country's top technocrats. For instance, Pablo Andrade uses Peter Evans and James Rauch's methodologyFootnote 57 to calculate ‘weberianness’ (agency capacity) scores for six Ecuadorean government entities.Footnote 58 The survey consists of ten questions, including an evaluation of the role of the institution in formulating the government's political economic plans, the proportion of officials who entered the institution via merit-based examination, the time the typical official spends working at the institution and other queries related to promotion and salary. As one would expect for one of the state's most important agencies, SENPLADES scored the highest of the six surveyed.

Under Correa's rule, the average ministerial tenure was just 400 days, among the lowest in Latin America.Footnote 59 However, SENPLADES secretaries have lasted far longer. Fander Falconí was secretary from January 2007 to December 2008, after which Correa named him minister of foreign relations. His replacement, René Ramírez, ran SENPLADES from December 2008 to November 2011 and then led the Secretariat of Higher Education, Science, Technology and Innovation for six years. To replace Ramírez, Correa brought Falconí back to SENPLADES from November 2011 to August 2013. The third secretary of the organisation, Pabel Muñoz, lasted more than two years in office. None of these secretaries served fewer than 700 days in office – nearly twice the duration of the average ministerial tenure. Moreover, the fact that Correa rotated these individuals to other portfolios (and in Falconí’s case, back again) indicates that he only entrusted the position to loyalists.

SENPLADES was responsible for developing a number of policies aimed at transforming the state's developmental model, including the Organic Law of Regulation and Control of Market Power, the Law of Higher Education, the Code of Planning and Public Finance, and the updated National Development Plan. In addition, the body implemented a number of critical policies, including the State at Your Side strategy, the installation of the National Council of Competencies, and the National Plan of Decentralisation. Moreover, the agency exercised de facto control over a number of ministries by coordinating public service planning among the ministries of Education, Public Health, Economic and Social Inclusion, Sport, Interior, Justice, Human and Cultural Rights, and the Integrated Security System. However, while the relative power of the agency remained steady or grew over the course of the Correa presidency, its absolute economic power was tied almost directly to the price of petroleum: while its budget increased nearly every year between 2007 and 2012, it flattened in 2014 and 2015 and actually decreased by 34 per cent in 2016.Footnote 60

A weak or non-existent developmental planning agency would fundamentally hinder efforts to pursue post-neoliberalism. Unlike laws or judicial decisions generated by deliberative bodies, SENPLADES is endowed with the power to consult with citizens on planning policy and yet hierarchical and centralised enough to push forward policy with a limited amount of deliberation; in neither case is it forced to consult with the powerful veto players who might significantly alter developmental policy or push it from the path pursued by the president and the social groups advocating post-neoliberal policies.

Increasing State Size and Capacity

Third, since the post-neoliberal project is a state-led policy, it is necessary to create an administrative apparatus large enough and capable enough to successfully implement and regulate it. Consequently, the state should tend to increase public spending, add new employees (and agencies) to the public sector and reorganise the public administration to meet its new policy needs. In the Correa administration's quest to remake Ecuadorean political, economic and social life, it increased the size of the state, promoted its centralisation and, in many cases, improved the administrative capacity for public agencies to get things done.

To begin, Correa's government increased the number of public servants and the amount of money directed towards them. Although official government statistics are difficult to obtain, the Inter-American Development Bank finds that the number of civil servants more than doubled between 2003 and 2011, from 230,185 to 510,430.Footnote 61 While some of these hires filled new agencies, the majority were sent to staff existing administrative bodies in strategic policy areas. According to Correa himself, 97 per cent of the positions created were in just five sectors: public education, public health, the judiciary, policing and social welfare. An overwhelming percentage of these were street-level bureaucrats providing front-line services to citizens: between 2006 and 2015, the government added 26,328 teachers (a 15 per cent increase, from 197,000 to more than 230,000) and 31,407 healthcare workers (marking an astounding 81 per cent increase, from 28,626 to 70,033).Footnote 62 Moreover, total public sector salaries more than tripled, from US$3.161 billion in 2006 to US$9.6 billion in 2014, representing an increase from 7 per cent of the country's GDP in economically lean times to 9.5 per cent in more prosperous ones.Footnote 63 The state's prioritisation of improvements to social services was clear.

There was concomitant growth in the number of bureaucratic bodies. Admittedly, the state also grew under neoliberalism: in 1976, the executive branch consisted of a mere 11 ministries and 37 other public agencies; by 1999, this had grown to 15 ministries and 112 agencies. However, the scale of the expansion under Correa was unprecedented, with the number of ministries and other agencies ballooning to 28 and 152, respectively, under his watch.Footnote 64 Figure 1, which shows the evolution of ministries between 1979 and 2017, clearly illustrates the relative magnitude of ministerial expansion under the Correa administration and how it compares to previous growth of the executive branch – as well as the decrease in ministries with the election of Lenín Moreno in 2017.

Figure 1. Cabinet Ministries in Ecuador (1979–2017)

That is not all. Correa also added an array of new secretariats during his time in office, bringing the number from three to 11.Footnote 65 In fact, the cabinet more than doubled in size from 2007 to 2017, from 16 ministries and three secretariats to 28 ministries and 11 secretariats.Footnote 66 Some of these new agencies were designed specifically to help design and implement the state's PNBV, including SENPLADES, the National Secretariat of Public Administration and the Secretariat of Good Living. Others, however, were broken off from existing ministries or elevated to cabinet-level status by the president. Table 1 shows the evolution of cabinet ministries from 2005 to 2017.

Table 1. Evolution of Cabinet Ministries (2005–17)

Source: Santiago Basabe-Serrano, John Polga-Hecimovich and Andrés Mejía Acosta, ‘Unilateral, Against All Odds: Portfolio Allocation in Ecuador (1979–2015)’, in M. Camerlo and C. Martínez-Gallardo (eds.), Government Formation and Minister Turnover in Presidential Cabinets: Comparative Analysis in the Americas (London: Routledge, 2018), pp. 182–206.

In addition to the regular ministries and secretariats, the president created an additional bureaucratic layer in the form of ‘coordinating ministries’. These bodies, linked to different dimensions of the National Development Plan, were in charge of managing a common fleet of ministries and affiliated agencies, while coordinating between the central government and local governments. For instance, the Coordinating Ministry of Strategic Sectors managed the Ministry of Electricity and Renewable Energy and the Ministry of Telecommunications and Information Society, as well as at least eight other public agencies and corporations dealing with energy and telecommunications issues. These agencies and the new administrative structure assisted the government in centralising policy-making and policy implementation.

The president also engaged in other changes to the administrative apparatus, as shown in Table 2. Through executive reorganisation, he eliminated some 79 public entities without clear responsibilities or which suffered from bureaucratic redundancy. Correa and his ministers also reorganised or transformed 59 agencies and created 53 new public institutions.Footnote 67 Additionally, the creation or reorganisation of 24 public enterprises, 16 regulatory agencies and two new superintendencies complemented the growth of state presence in the economy and society as a tool of counter-reform to the neoliberal model.Footnote 68

Table 2. Structure of the Ecuadorean Executive Branch, January 2017

Source: Office of the Ecuadorean Presidency (www.presidencia.gob.ec).

The government also centralised authority. Despite the adoption of fiscal decentralisation rules and decentralised political competition, the commodities boom under Correa undermined devolution, allowing the central government to re-centralise the allocation of fiscal transfers and gain greater political leverage over the country's ‘decentralised autonomous governments’.Footnote 69

Finally, the government attempted to increase its administrative capacity, or its ability to carry out programmes in accordance with previously specified plans. Prior to Correa's ascendance, the country suffered from unsatisfactory bureaucratic quality, with one study ranking it fifteenth out of 20 countries surveyed in Latin America.Footnote 70 Similarly, Laura Zuvanic and Mercedes Iacoviello place Ecuadorean bureaucracy in, at best, the middle tier regionally.Footnote 71 Nonetheless, organisational capacity in Ecuador's public agencies increased between 2002 and 2012. Iacoviello found improvements in four of the five categories she analysed (efficiency, merit, structural consistency, functional capacity), and no change in the fifth (integration capacity).Footnote 72 On average, scores jumped by more than 40 per cent over the ten-year period. This is reflected by new demands for training and educational requirements in certain ministries or positions, as well as organisational learning from agencies such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which helped improve coordination within the Ministry of Education.

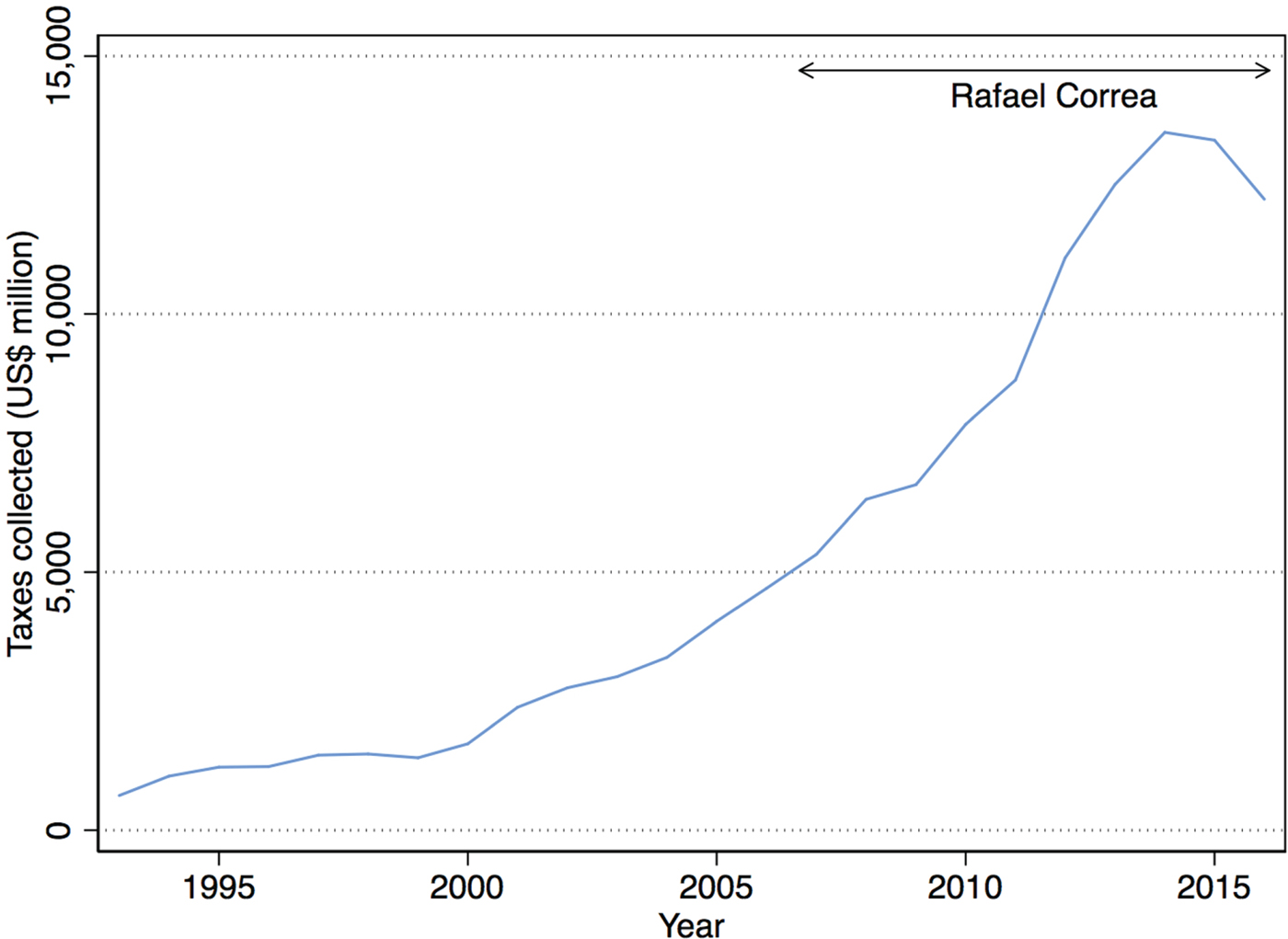

The ability of a specialised agency to carry out its administrative tasks in a timely and efficient manner provides a suitable measuring stick. The evolution of the reach of Ecuador's tax authority, the Servicio de Rentas Internas (Internal Revenue Service, SRI), is a good example.Footnote 73 Figure 2 shows the evolution of the SRI's national income tax collection over a 23-year period (1993–2016). Part of the increase is certainly due to a wider tax base and higher incomes, but the slope of the line also indicates better coverage and less tax evasion, as the amount of revenue more than doubles between 2007 and 2016. What is more, this reflects the Correa government's greater investment in technology and infrastructure for the SRI in an effort to crack down on tax evaders and improve agency efficiency.

Figure 2. Tax Revenue in Ecuador (1993–2016)

Of course, other forces, specifically corruption, threaten to undermine this improved capacity and the continued feasibility of the post-neoliberal project. A number of Correa administration officials have faced accusations of gross corruption and bribery, including former Hydrocarbons Minister Carlos Pareja and former Attorney General Galo Chiriboga, as well as former Vice-President Jorge Glas, who the National Assembly removed from office on a technicality as he faced impeachment, and who was later criminally convicted for receiving bribes from the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht.Footnote 74 On the one hand, revelations of corruption are indicative of the lack of oversight and failures of accountability mechanisms as a consequence of the centralisation of power. On the other hand, they undercut the state's project and explicitly weaken the ability of the state to get things done efficiently.

In short, Correa significantly increased the size of the Ecuadorean bureaucracy and its interventionist power, while simultaneously encouraging the use of merit-based criteria for the selection of bureaucrats and more flexible management of human resources in many agencies. These changes allowed the president and his administration to better pursue their developmental and policy goals through a stronger, more capable and more omnipresent state. Of course, this says nothing about the effectiveness of buen vivir policies or their implementation; simply that these steps of institutional change were necessary for subsequent economic and social changes.

Propitious Economic Conditions and Government Spending

The re-centralisation of power into SENPLADES and the National Planning Council, the dizzying growth of the bureaucracy, and increases in public servant salaries were made possible in large part due to favourable economic conditions. While neoliberal state reforms, such as eliminating agencies, reducing the number of public employees and allowing the market to play a larger role, should result in the lower expenditure of public resources, post-neoliberal reforms that seek to increase the role of the state, both in markets and in society, require higher expenditure. As Levitsky and Roberts argue, it should come as no surprise that the export boom allowed political parties of the Left to finally govern as they wanted, rather than be constrained by balance-of-payments and fiscal pressures.Footnote 75 This rise in commodity prices was accompanied by other sources of revenue, as well as deficit spending.

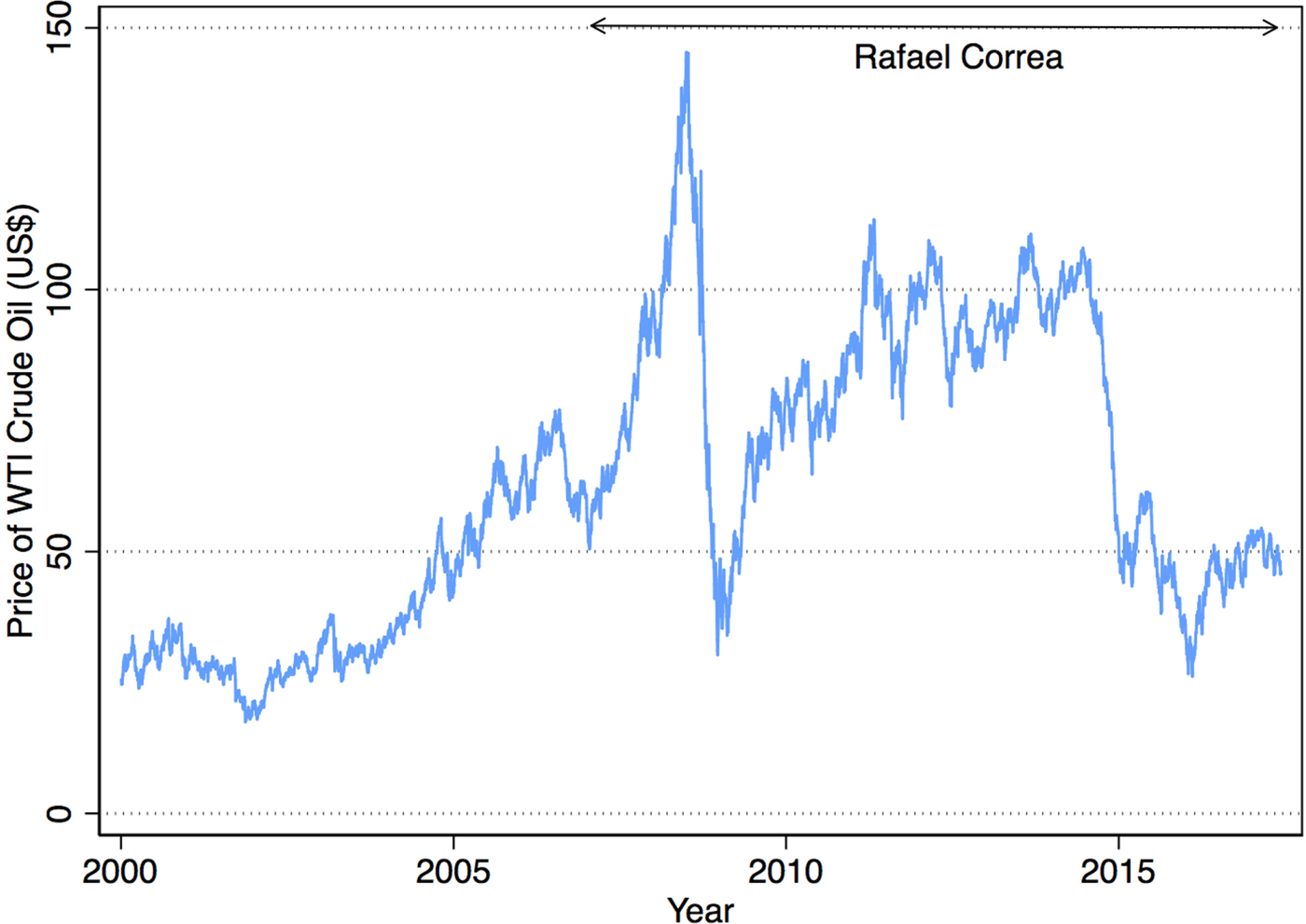

President Correa and his government combined the good luck of favourable commodity export conditions with a proactive tax collection policy. Ecuador's primary source of export earnings is petroleum, a commodity whose value skyrocketed between the mid-2000s and around 2013. As Figure 3 illustrates, Correa entered office when the value of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate crude oil was approximately US$50. By mid-2008, that price had nearly tripled, to US$145. Despite a drop in 2009, the price soon recovered. It follows, therefore, that ambitious reorganisation and growth of the state would have been more difficult in Ecuador in the early 2000s, when oil prices were around US$30 per barrel, and much easier between 2009 and 2013, when prices oscillated between US$70 and US$110 per barrel.

Figure 3. Price of West Texas Intermediate Crude Oil (2000–17)

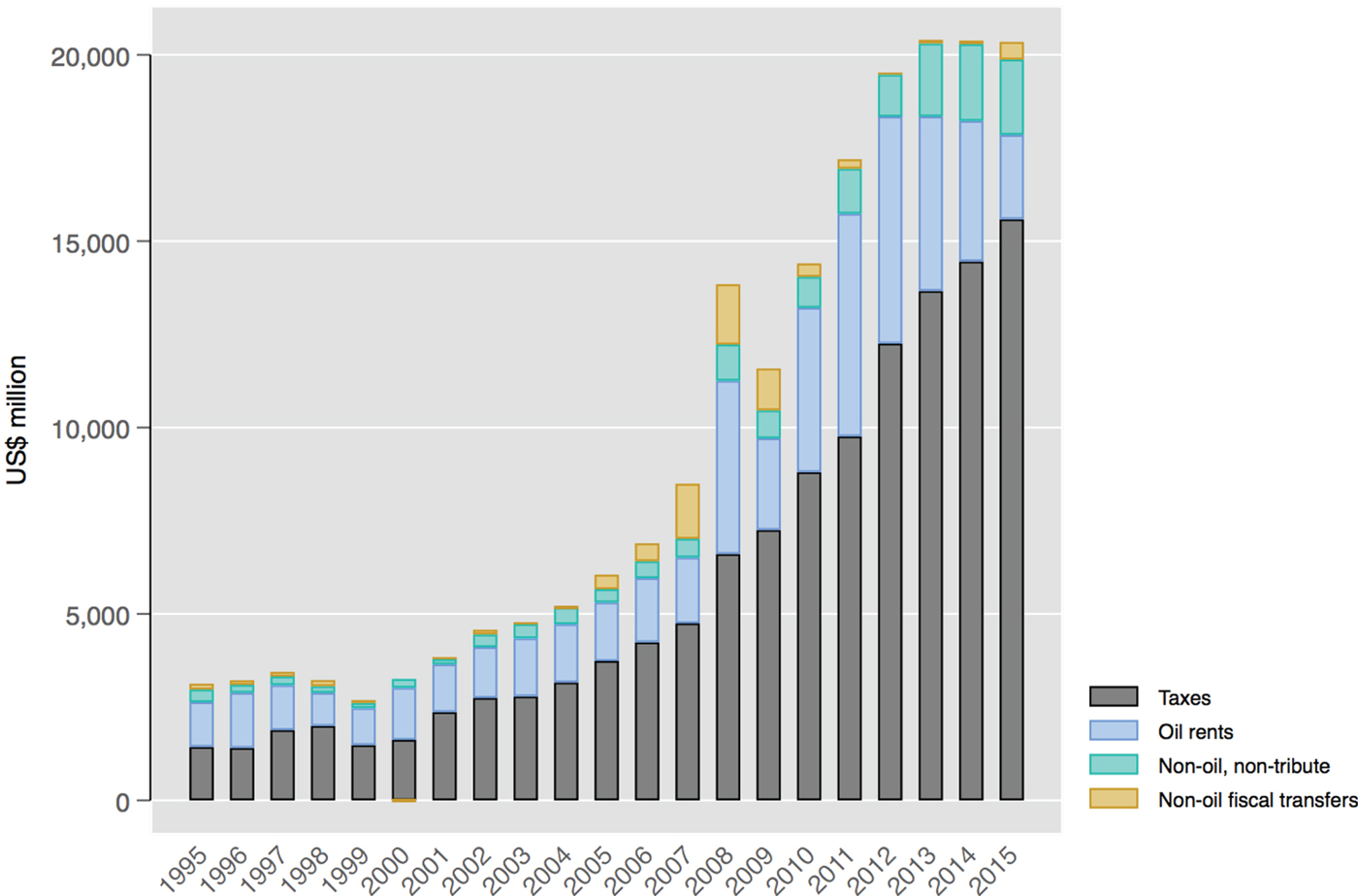

To minimise the boom-and-bust effect of volatile oil prices on revenue, the government also increased progressive tax collection coverage and sought a series of billion-dollar loans from China.Footnote 76 This tax revenue is a product of a bevy of duties levied on citizens and on business, but it also reflects greater collection efficiency on the part of the SRI. These monies are a necessary complement to – and buffer against – volatile oil rents. Figure 4 shows government revenues between 1995 and 2015 broken down by taxes, oil rents, non-oil fiscal transfers, and non-oil, non-tribute income. While oil income was markedly higher from 2008 to 2015 under Correa than it had been prior to his taking office, tax revenue increased monotonically over the entire period and accounted for a proportionally larger stake of overall revenue than sales of oil. While non-oil fiscal transfers (proceeds from state utilities and enterprises) remained a small proportion of revenue, non-oil, non-tribute proceeds (money from the state's decentralised and autonomous territorial units, and from international assistance) grew significantly over the course of Correa's time in office.

Figure 4. Breakdown of Ecuadorean Government Revenue (1995–2015)

In concert with the country's development plan, the government in 2008 passed the Law of Fair Taxation, which maintained a 25 per cent income tax but progressively raised it to 35 per cent based on income, and which included deductions for housing, health, education and clothing. The government also increased the inheritance tax, from a flat 5 per cent to a variable rate of up to 35 per cent, and it raised the tax on foreign currency exchanges from 0.5 per cent to 5 per cent in 2011.Footnote 77 In all three cases, the taxes placed a proportionally larger fiscal burden on wealthier households than on poor ones. Nonetheless, the regressive value added tax (VAT) of 12 per cent accounted for more than 50 per cent of total tax earnings, and its share increased precipitously between 2009 and 2014.Footnote 78 In sum, although Correa doubled down on extractivism during his time in office, he also recognised that the viability of his post-neoliberal plan depended on non-oil money, and he pursued a tax policy at least partially consistent with the PNBV.

As a result, government revenues and expenses both increased between 2009 and 2014. This money still went to social welfare and infrastructure projects that formed parts of the government's development plan,Footnote 79 as well as to the agencies and administrative bodies that managed, oversaw and implemented these policies. Without this sudden and unexpected influx of cash afforded by an oil boom, along with duties imposed on the local population, it is doubtful that the country's post-neoliberal project – or any post-neoliberalism project – could boast sufficient resources to remake the state, staff it and engage in the types of socio-economic policies that Ecuador has been able to implement.

Post-Neoliberalism's Sustainability

The implementation of post-neoliberalism in Ecuador – and more broadly, in Latin America – is not a secondary effect of the commodities boom of the late 2000s and early 2010s or a self-sustaining developmental paradigm, but instead represents the transformation of the state via institutional conversion. This post-neoliberal reform requires the confluence of a number of necessary (though not independently sufficient) conditions: changes in the legal-constitutional status quo, empowerment of and dependence on a state planning agency, and growth of the state and its capacities, all of which are sustainable only through high government revenues.

While the type of institutional change present in Ecuadorean post-neoliberalism follows the pattern of conversion proposed by Thelen,Footnote 80 the speed with which it was carried out contradicts dominant theories of institutional change. These are largely based on advanced industrial democracies and stress the transformative effects of incremental modifications.Footnote 81 In such cases, institutions constrain the preferences and policy choices of elite actors as they attempt to cultivate change. By contrast, post-neoliberalism's rapid rise and entrenchment by Rafael Correa and other leaders demonstrates that this is not always true. In places like Ecuador, many existing political institutions are weak and inchoate, and there may be fewer constraints on actors seeking such an institutional transformation. As such, this case suggests that processes of institutional change in the developing world may differ from those of developed democracies.

Ecuador's reality also demonstrates post-neoliberalism's limitations. Although President Lenín Moreno, Correa's vice-president from 2009 to 2013, was elected in 2017 in part to continue his predecessor's developmental model, its sustainability is in jeopardy. In fact, the same concentration of powers that allowed Correa to pursue post-neoliberalism has been similarly beneficial to Moreno. For example, in response to fiscal austerity pressures, Moreno used his first presidential decrees to shrink the size of the state rather than increase it. Nonetheless, this impetus for change is counterbalanced by a path dependency that makes weaning citizens off the post-neoliberalism state difficult. As a result, the president appears to be walking a fine line between eliminating parts of the state and trying to maintain the most important elements of the new social welfare reality. For instance, while the Secretariat of Buen Vivir was among the first wave of public administration casualties, Moreno replaced it with the Plan Toda Una Vida (A Lifetime Plan) Technical Secretariat aimed at his own pet social welfare project of the same name.

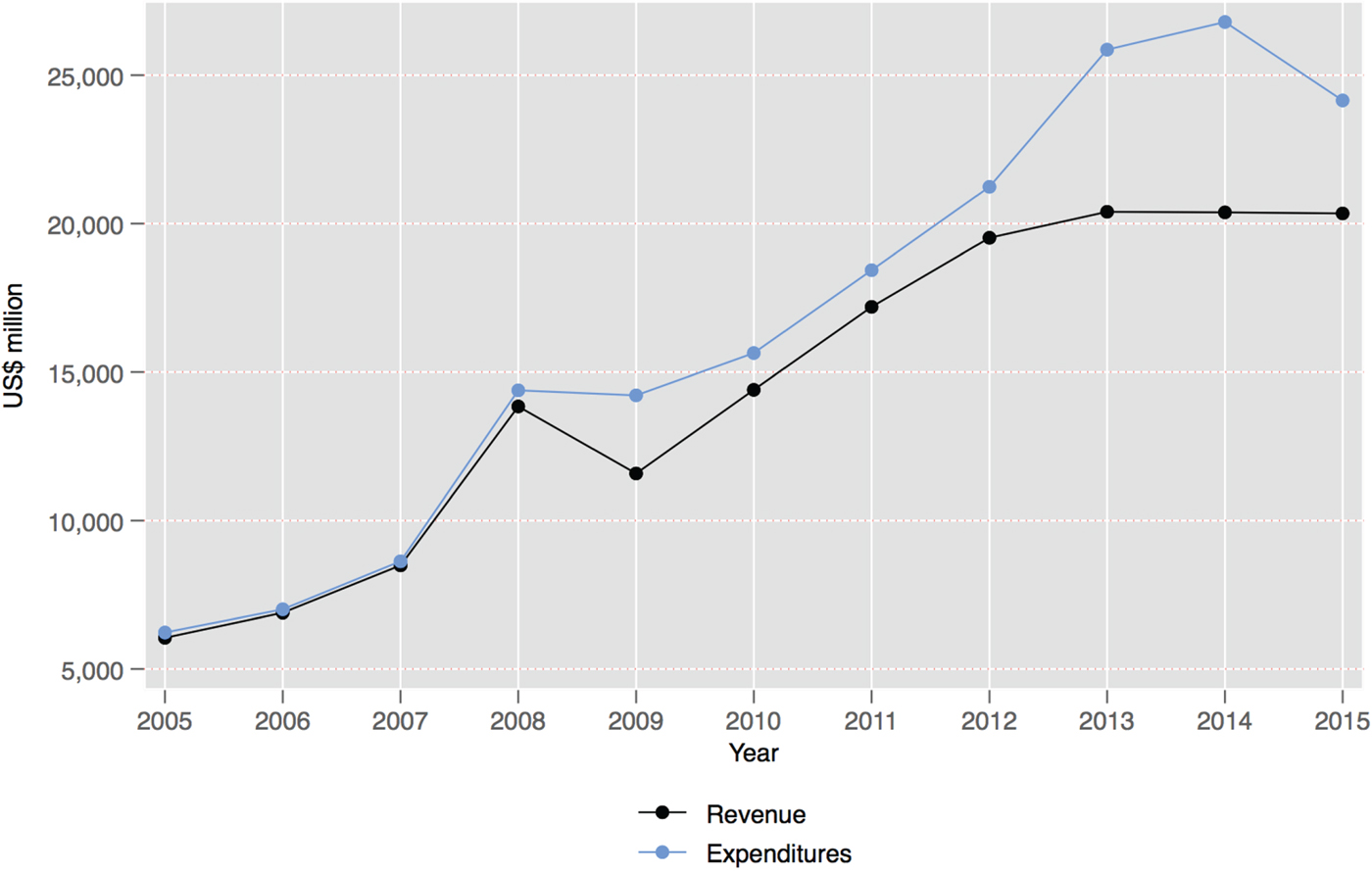

The significant drop in oil prices since 2015 has hurt the country's ability to maintain such a large state on top of its social spending requirements.Footnote 82 Although the economic shock has been somewhat mitigated by an increase in tax revenues collected by the state, maintaining the size of the state is proving unsustainable. As Figure 5 shows, government expenditures outstripped revenue for nearly the entire Correa administration, and the fiscal deficit was especially large from 2013 to 2016. Correcting this imbalance – or simply avoiding larger, less manageable annual deficit figures – will require a trade-off, and shrinking social spending and the size of the state is easier than growing revenue from a dollarised, commodity-dependent economy. Although short-term deficit spending may increase GDP growth, in the long term this will contribute to increased indebtedness. In response, Moreno has already been forced to decrease the size of the planning state, eliminating all six coordinating ministries upon taking office – and offering yet another example of institutional conversion.

Figure 5. Ecuadorean Government Revenue and Expenditures (2005–15)

This also demonstrates the vital role that healthy government revenue played in permitting post-neoliberal projects in Argentina, Bolivia, Venezuela and possibly Brazil. If political administrations hope to move their countries away from neoliberalism, they will be forced to increase spending on planning and public administration. Further, as states’ ambitions increase, their fiscal requirements also grow, demanding even higher government revenue. It is no surprise, then, that leaders of commodity-dependent states were able to contest neoliberalism in the 2000s at the height of the commodities boom. However, the centrality of this condition to the viability of post-neoliberalism also implies that the end of the boom has marked the decline in social spending in many of these places (in addition to the effects of profound government corruption in places like Brazil, Venezuela and others). Without ample government reserves or foreign loans, maintaining the state's role in various spheres becomes more difficult.

We maintain that all post-neoliberal states were moved to undertake similar institutional reforms, even if their logic differed substantially from case to case. For example, even though in Bolivia the rationale for post-neoliberalism had more to do with de-colonising the state, Bolivian political leadership still saw fit to enshrine buen vivir in its 2009 Constitution, to establish the Ministry of Development Planning and to charge that ministry with writing and carrying out its Comprehensive Development Plan for Good Living under the aegis of a larger state.Footnote 83 Likewise, although Argentine federalism dictates that education, health and other basic public policies be made at a provincial level, the federal government under Néstor Kirchner nonetheless pursued a highly active state in response to the perceived failures of neoliberalism, following the basic guidelines we establish here.Footnote 84

Differences between these states, however, may point to variability in terms of post-neoliberalism's sustainability. Steven Levitsky and Kenneth M. Roberts’ typology of the Latin American Left, based on the combination of party institutionalisation (institutionalised vs. new movement) and the locus of political authority (dispersed vs. concentrated), may offer some insight.Footnote 85 These authors place Ecuadorean correísmo alongside Venezuelan chavismo on the ‘populist left’, where authority is concentrated and the movement is new and un-institutionalised. Since the leadership in these countries is not anchored in coherent social mobilisations or representative institutions, but concentrated in an individual, the political will to sustain post-neoliberalism depends to a greater extent on the individual in power, rather than the population. A change in leadership may therefore amount to a change in the development pattern. By contrast, leftist governments growing out of established party organisations or anchored by coherent social organisations may have brighter prospects for sustaining the political will to drive post-neoliberalism. In those places, post-neoliberalism would be more likely to survive beyond the president's tenure.

Future scholarship should evaluate these propositions and their implications in other contexts. Governments across Latin America have used variations of post-neoliberal reform. However, the academic literature has tended to focus on constitutional or economic change, rather than the bureaucratic-institutional consequences. This must be studied if scholars are to understand the true characteristics and consequences of post-neoliberal reform. The Ecuadorean case demonstrates that the political will to present and undertake a post-neoliberal project must be accompanied by a number of other necessary elements, without which political resolve alone may not be enough.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Iván Llamazares Valduvieco, Manuel Alcántara Sáez, Felipe Burbano de Lara, and Santiago Basabe-Serrano for their comments and criticism. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not represent the views of or endorsement by the US Naval Academy, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the US government. All errors are, as always, our own.