Introduction

With the workload of courts in most developed countries drastically rising over the last century, the number of law clerks as well as their tasks and duties have increased substantially. Hence, Richard Posner (Reference Posner2008, 61) proclaimed that, in the United States (US), we are currently in the “age of the law clerk.” This prominent role of law clerks forces judges to reconsider their own position and function. On the one hand, judges can benefit from law clerks assuming more duties as well as from the input of law clerks as sounding boards. On the other hand, judges may have to confront writing practices and decisions by law clerks that conflict with the judges’ own interests and beliefs while retaining ultimate responsibility for judicial decisions.

A large part of the literature on the involvement of law clerks in administering justice focuses on detecting and problematizing their ideological influence on court case outcomes. In these studies, principal agent theory is often used to explain how judges (“principals”) try to control the unwelcome risk of influence by law clerks (“agents”). The most influential studies that have applied the principal agent theory examined the position of law clerks at the US Supreme Court. From such research, it has emerged that the influence of law clerks on Supreme Court Justices’ decisions is larger as the political attitudes of Justices and law clerks converge then when they diverge (for references, see Mascini and Holvast Reference Mascini and Holvast2020). This appears to indicate that judges manage to prevent unwelcome political opinions from intruding into the decision-making process when they delegate tasks and responsibilities to law clerks. One way in which judges control the political influence of law clerks is by playing a decisive role in the annually recurring recruitment and selection of law clerks (on clerk selection, see, e.g., Ward and Weiden Reference Ward and Weiden2006, 55–108), who are appointed as Justices’ interns, typically for a period of one year. For Justices, political party preference is an important selection criterion (Peppers and Zorn Reference Peppers and Zorn2008). This focus on the political opinions of law clerks in American principal agent theory research is defensible within the strong and increasingly politicized context of the US Supreme Court (Ward Reference Ward, Epstein and Lindquist2017; D’Elia-Kueper and Segal Reference D’Elia-Kueper, Segal, Epstein and Lindquist2017).

However, research in a Dutch context has shown that the generalizability of this American research to other court settings – for example, the Dutch judiciary – is limited. In district courts in the Dutch civil law jurisdiction, the political views of law clerks are not decisive in terms of determining how much influence judges allow them. Rather, the degree of judges’ confidence in law clerks’ professionalism, the degree to which judges see greater benefits versus risks associated with the deployment of law clerks, and the extent to which judges are open to considering managerial skill, such as efficiency, are more germane to the extent to which judges allow law clerks influence on the decision-making process (Mascini and Holvast Reference Mascini and Holvast2020). Moreover, Dutch administrative law judges do not attempt to control the risks associated with the deployment of law clerks by interfering with the recruitment and selection of new clerks, but they do attempt to control the collaboration with law clerks in day-to-day practice. The lack of generalizability of the findings of the US Supreme Court studies to the Dutch context is understandable given the fact that, in the Netherlands, administrative justice is generally not considered to be politicized. Judges also do not directly employ law clerks for a limited period of time as their personal clerks. Rather, clerks are employed by the court organization, and they regularly obtain permanent contracts. This Dutch study demonstrated that the legal context is important for understanding how judges attempt to control the influence of law clerks on judicial decision-making.

Another line of research also primarily focused on the US Supreme Court investigated the influence of law clerks on the writing styles of opinions and judgments. Judge and legal scholar Richard Posner (Reference Posner1985, 104) was one of the first to maintain that the delegation of drafting duties to law clerks “transforms the judge from a draftsman to an editor.” From this point of view, this transformation of the role of the judge in drafting renders opinions and judgments less appealing and candid than if the judge had personally written them (for other references, see Choi and Gulati Reference Choi and Gulati2005, footnote 3). Posner attributed this change in the writing of opinions and judgments to two mechanisms (see also Posner Reference Posner2006, 32). First, by serving as editors, judges exclude themselves from the writing process; however, according to Posner, the act of writing is important for judges to arrive at conclusions about court cases. With judges serving as mere editors, therefore, opinions and judgments can become less deliberative when law clerks play a larger role in the drafting process (see also Wahlbeck, Spriggs, and Sigelman Reference Wahlbeck, Spriggs and Sigelman2002, 167).

Second, law clerks are less likely than Justices to put their own stamp on opinions and judgments because, as temporary interns, their experience is much more limited. Posner claimed that this lack of experience results in a greater need for certainty on the part of clerks. Inexperienced clerks may attempt to derive this certainty by writing extensive justifications that include an abundance of references to caselaw and a reliance on standardized judgments (Posner Reference Posner1985). These characteristics tend to reduce the usefulness of these judgments as a guide for future judicial decision-making (Posner Reference Posner1985, 109; for a problematization of the role of law clerks and the writing style of judgments, see also Rosenthal and Yoon Reference Rosenthal and Yoon2011).

The concerns that Posner and others have expressed about the influence that the delegation of drafting duties may have on the writing of opinions and judgments is most comprehensible in the context of the US Supreme Court. In this setting, it is a given that Justices possess much more experience than law clerks. In the US Supreme Court, clerks complete temporary internships, while judges typically have had long legal careers before appointment to the Supreme Court. At the same time, it is again questionable whether claims regarding the influence of law clerks on the writing style of judgments pertaining to the US Supreme Court are generalizable to other judicial contexts. Other jurisdictions feature lifelong clerkships – the so-called scribe model (Sanders Reference Sanders2020). Jurisdictions that rely on the scribe model often employ more experienced law clerks, in addition to clerks with limited experience. If Posner was correct in his assertion that the writing style depends in part on experience, then it would naturally follow that opinions and judgments written by experienced law clerks would reflect a greater degree of confidence in terms of writing style. More specifically, it might be expected that such judgments would be succinct, contain minimal legal references, and reflect minimal reliance on standardized language when written by experienced law clerks.

The aim of our research was to investigate the relationship between the level of experience of law clerks and the confidence that is expressed in the writing style of their drafted judgments. To accomplish this, we conducted our research in a jurisdiction in which the experience of the law clerks can differ significantly. This is the case in the Netherlands because, in the Dutch judiciary, law clerks – commonly after a first period of temporary employment – regularly enjoy permanent appointments to the courts. The composition of law clerk corps is diverse. In the past, a substantial number of law clerks were internal transfers (e.g., from administrative positions) who did not receive extensive legal education but learned on the job. More recently, the majority of clerks are entrees from outside of the judiciary. A law clerkship has become a rather popular way for law school graduates to start their career, with various of these clerks leaving after a number of years for a position outside of the court (Holvast Reference Holvast2017, 48–49). In addition, law clerks in the Netherlands commonly serve as part of a pool that is available to all judges. Judges in the Netherlands also vary in terms of their legal experience; there are different routes to becoming a judge, some of which require only a few years of prior legal experience. Thus, law clerks and judges with diverse experience work together in varying combinations.

Another feature of the Dutch judiciary, and more specifically the administrative law divisions, that made it a suitable setting for this study is that judges in the Netherlands largely delegate the drafting of judgments to law clerks (Holvast Reference Holvast2017). On this basis, it can be assumed that law clerks leave an important mark on final judgments. Our research was based on all judgments published in the Netherlands in the year 2020 on administrative law cases. We used computational analysis and self-learning algorithms for the coding of the data.

This study contributes to the literature by testing the tenability of the assumption that the delegation of drafting duties to law clerks renders the written judgments less appealing and candid and therefore less useful for future judicial decision-making than those written by more experienced legal professionals. It has been posited in the literature that the lack of appeal in terms of the writing style of judgments is a direct result of law clerks’ inexperience. This would mean that concerns about the writing style of judgments would be less significant in jurisdictions in which clerks have permanent instead of temporary appointments. After all, in such jurisdictions, clerks regularly possess more legal experience. Indeed, clerks in such jurisdictions may have experience (in terms of years worked in the legal field) that even exceeds that of some judges.

In the next section, we discuss our stylometric research into the fingerprint that judges and law clerks leave behind on judgments and the role that law clerk experience plays in this influence. This discussion is followed by sections detailing our data, methods, and results. We close with a conclusion and discussion.

Stylistic “fingerprints”

There is a long tradition of research into the writing styles of all types of authors. One example is the research that attempted to distinguish whether a poem had been accurately ascribed to Shakespeare. Only relatively recently have researchers begun to use stylometric analysis to study the authorship of judicial decisions. It is not an obvious choice to apply stylometric analysis to judgments, as judges work in an institutional environment that imposes particular restrictions unlikely to lead to the development of an individual writing style like that of novelists (Choi and Gulati Reference Choi and Gulati2005). However, due to the digitalization of legal decisions and the development of self-learning algorithms, it has become easier to detect subtle stylistic differences by analyzing large quantities of text in terms of multiple style characteristics (Kantorowicz-Reznichenko Reference Kantorowicz-Reznichenko2021).

The interest in detecting authorship and analyzing the writing style of legal judgments originates from the discussion about how the delegation of drafting duties by judges to law clerks transforms the work of judges and affects the writing style of judgments. Several authors have suggested that a judge’s personal style is more recognizable when he or she plays a larger role in the drafting of the judgments than when that role is confined to editing and commenting on a law clerk’s draft. After all, notwithstanding the directions given by judges, clerks have to make stylistic decisions about the choice of words, the structure of judgments, and the references to caselaw. Indeed, there is a small body of empirical literature that focuses on the particularities of clerks’ writing styles (Wahlbeck et al. Reference Wahlbeck, Spriggs and Sigelman2002; Choi and Gulati Reference Choi and Gulati2005; Rosenthal and Yoon Reference Rosenthal and Yoon2011; Bodwin, Rosenthal and Yoon Reference Bodwin, Rosenthal and Yoon2013; Carlson, Livermore and Rockmore Reference Carlson, Livermore and Rockmore2016; Pelc and Pauwelyn Reference Pelc and Pauwelyn2019).

The existing literature almost entirely focuses on the US Supreme Court and the (in various administrative respects) comparable Canadian Supreme Court (with the exception of Pelc and Pauwelyn Reference Pelc and Pauwelyn2019, who studied the World Trade Organization). Using computational linguistics, various studies have demonstrated that delegation is indeed recognizable in the writing style of legal judgments. First, stylometric studies have used variations in the writing styles of all judgments for which a judge is responsible as a proxy for law clerks’ influence in the drafting process, assuming that the writing style of judgments varies depending on whether one or several clerks are involved in the drafting process. These studies have shown a steady increase in the variation of writing styles, which suggests that, in an era of rising numbers of clerks, judges have become increasingly inclined to delegate parts of judgment drafting to law clerks (Bodwin et al. Reference Bodwin, Rosenthal and Yoon2013; Carlson et al. Reference Carlson, Livermore and Rockmore2016).

Second, other studies have found that the writing style of judgments attributed to individual judges varied over time. This suggests that, during some years, clerks made a more significant contribution to the style of final judgments than in other years. A likely assertion that can be derived from this finding is that, given that the clerks in these studies commonly clerked for one year, some clerks authored larger parts of judgments than others (Bodwin et al. Reference Bodwin, Rosenthal and Yoon2013). Third, Wahlbeck et al. (Reference Wahlbeck, Spriggs and Sigelman2002) showed that the personal writing style of law clerks was more detectable in opinions attributed to a judge who was known to provide clerks with significant autonomy in the preparation and drafting of opinions versus those by a judge with a reputation of closely monitoring and directing the drafting process. All these studies suggested that the “fingerprints,” or unique stylistic characteristics, that judges leave on their judgments decrease when their role shifts from that of author to editor.

Why this interest in judges’ fingerprints on judgments? First, style differences have been presented as evidence that judges indeed delegate (to different degrees) the drafting of judgments to law clerks. Second, differences in writing style are themselves considered relevant as judgments drafted by law clerks are often considered less appealing and candid than judgments written by judges and therefore less likely to be used in future judicial decision-making. It is commonly assumed that, due to their inexperience, young clerks write comparatively more elaborate judgments and use more complex words than judges (Posner Reference Posner1985; Choi and Gulati Reference Choi and Gulati2005; Pelc and Pauwelyn Reference Pelc and Pauwelyn2019). Administrative staff, especially young staff members, “feel compelled to dissect every issue and argument to the fullest extent … write extensive background paragraphs, broadly state the law, and venture opinions on matters that need not be decided in the pending dispute” (Pelc and Pauwelyn Reference Pelc and Pauwelyn2019, 34).

Similarly, law clerks are also assumed to rely heavily on precedent. According to Posner (Reference Posner1985, 109), “many law clerks feel naked unless they are quoting and citing cases and other authorities.” Moreover, some commentators have asserted that clerks, as novice attorneys, rely extensively on multipart balancing tests in the opinions they write (Kronman Reference Kronman1993; Posner Reference Posner1996).

Without exception, these authors have suggested that the differences in writing styles between judges and law clerks are related to experience. “Judges, who tend to have been experienced lawyers or academics earlier in their careers, are likely to be more confident in their writing than their clerks, who tend to be fresh out of law schools” (Choi and Gulati Reference Choi and Gulati2005, 1102). Substantiating decisions with elaborate arguments, using unnecessarily complex words, making many references to caselaw and other authorities, and extensive balancing of values can provide inexperienced clerks with a kind of certainty that experienced judges do not require (Posner Reference Posner1985, 115; Estreicher Reference Estreicher1986). Rosenthal and Yoon (Reference Rosenthal and Yoon2011) suggested that, if the primary problem is indeed the delegation of duties to less experienced persons, the clerk selection process could be altered to hire more experienced clerks for longer durations than the common one-year positions.

Research in settings other than the US Supreme Court indeed has suggested that the experience of law clerks (or comparable judicial staff members) has an effect on how they write judgments. For instance, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) is known for its impressive number of staff members, whose positions are typically life-long careers. Cohen (Reference Cohen, Nicola and Davies2017) and Kenney (Reference Kenney2000) both referred to the asymmetry that can arise when assisting staff members (“référendaires”) have much more experience at the institution than the judges themselves.Footnote 1 Kenney (Reference Kenney2000, 614) stated that “longevity gives référendaires power, particularly when their knowledge of EC law and the institutional workings of the CJEU is paired with the lack of experience of a new judge.” Cohen (Reference Cohen, Nicola and Davies2017, 74) also mentioned this point, and, relative to judgment writing, one of her interviewees stated the following:

There are old référendaires who have 20 to 25 years of experience and will no longer take editing suggestions. You can send them edits and when it [the draft judgment] comes back, they haven’t picked up any. As a result, the judge isn’t aware [of the neglect of editing suggestions] because he has so much trust in his référendaire.

These studies indicated that, when clerks gain experience, their stylistic capabilities are more clearly visible in their drafted judgments.

This claim was supported by Holvast (Reference Holvast2017, 151), who concluded, regarding judicial assistants working at Dutch first instance courts, that the more experienced an assistant is, the more likely he or she is to develop an individual writing style. Stated differently, inexperienced assistants tend to conform to the norm when writing judgments, whereas more experienced assistants develop their own approach to judgment writing. In the Dutch judiciary, judicial assistants receive training in how to write and structure judgments. As Holvast (Reference Holvast2017, 151) put it, “While judicial assistants in the beginning quite strictly follow the style and format they were taught in the trainings, various senior assistants mention that they later on developed individual styles.” The scarce literature on delegating drafting duties in courts other than the US Supreme Court thus indicates that, once law clerks gain experience, they are less inclined to follow editing suggestions learned in classes and offered by judges. In other words, they appear to become more confident – similar to experienced judges – in writing draft judgments.

Based on the American literature that suggests that law clerks, due to inexperience, are less confident draftsmen than judges as well as the literature from other court settings that suggests that more experienced clerks are more confident draftsmen, we formulated the confidence hypothesis. We expected to find that judgments written by experienced law clerks would be a) shorter, b) less standardized, and c) contain fewer legal references than judgments written by less experienced clerks.

Methods

Data

The dataset that we used to test our hypothesis consisted of all 4,961 judgments issued in 2020 from Dutch administrative law courts in first instance and appeal that were published on Rechtspraak.nl on February 4, 2021.Footnote 2 A total of 322 unique judges and 519 unique law clerks were involved in these cases. The dataset was limited to all cases from a recent year – 2020 – and it was limited to the specific legal domain of administrative law to control for variability of court cases (as recommended by Choi and Gulati Reference Choi and Gulati2005). We selected administrative law because it enabled us to build on our prior studies that investigated the influence of law clerks in the Netherlands that also focused on administrative law (Mascini and Holvast Reference Mascini and Holvast2020; Holvast and Mascini Reference Holvast and Mascini2020).

We retrieved the dataset from the website of the Netherlands Council for the Judiciary.Footnote 3 In 2012, the Netherlands Council for the Judiciary decided to make the criteria for the publication of judgments on Rechtspraak.nl concrete and objective (Raad voor de Rechtspraak Reference voor de Rechtspraak2021c). The criteria prescribe the publication of the following judgments. First, all judgments at the highest courts and some specific court divisions are published (unless they have been declared inadmissible and/or have been dismissed with a standard formulation). Second, all judgments in which European or international treaties have been invoked are published. The same applies to judgments that have been published in earlier or later instances, relate to serious criminal cases, or to the recusal of judges. Third, judgments that meet criteria that are less easily objectifiable are published. This concerns judgments that relate to hearings that have received media attention, that have been published or discussed in a professional medium, or that are expected to have judicial precedent. Fourth, judgments that do not meet the aforementioned criteria are published as much as possible, when they do not solely consist of standard formulations or belong to categories that are prioritized by courts. The majority of the judgments do not meet the publication criteria, as our dataset contained 5.9% (4,961/83.740*100% = 5.9%) of all administrative law cases that were handled by district courts and high courts in 2020.Footnote 4

From these criteria can be derived that our dataset is not representative of all administrative law cases that were published in 2020. Judgments that do not meet one of the publication criteria (for instance, because they use standard formulations, do not fall in a category of prioritized cases, or do not have any expected judicial precedence) are underrepresented in our dataset. Given the publication criteria, the cases that are underrepresented in the dataset are the more run-of-the-mill routine cases. It is to be expected that judgments on routine cases are relatively short, standardized, and contain few legal references (if any at all). The underrepresentation of routine cases in our dataset may have limited the range of our dependent variables that pertained to the writing style of judgments: judgment length, references to caselaw, and judgment standardization. However, we do not know what impact this underrepresentation had on the correlation between law clerks’ experience and writing style.

Apart from underrepresenting routine cases, our dataset may be selective in another respect. Even after implementing the new publication criteria in 2012, judges and clerks still maintained discretion in deciding whether or not to publish judgments in relation to publishing criteria that are hard to objectify such as whether a case has precedence potential. Individual judges and clerks may differ in how they use their discretion in publication decisions that deal with these more subjective criteria, and these differences may even be linked to law clerks’ experience. For instance, it cannot be ruled out that more experienced clerks may prefer to publish opinions that are longer (or that are based on more complex cases), or that have fewer references, or that are less standardized.Footnote 5

A second dataset was used solely to measure the control variable of judge experience. It consisted of the public register of judges that is managed by the Netherlands Council of the Judiciary (Raad voor de Rechtspraak Reference voor de Rechtspraak2021a). From this register, the starting dates of judges’ professional careers were derived (see below). As there does not exist a public register of law clerks, the experience of law clerks had to be measured differently, which is explained below.

Writing style

The dependent variable consisted of the writing style of the judgments. The focus was on style characteristics that may be linked to the confidence that is associated with drafting duties. The literature suggests that relatively short and unstandardized judgments that contain few legal references indicate a confident writing style. These three style components – judgment length, level of standardization, and number of legal references – were measured independently.

Judgment length was measured by counting the number of unique characters in each judgment. A high score indicated a long judgment.

Judgment standardization measured the similarity of judgments to a corpus of other judgments: the more similar a judgment was to this corpus of other judgments, the more standardized it was. In previous studies, different indicators have been used to measure stylistic differences between legal texts. For example, Wahlbeck et al. (Reference Wahlbeck, Spriggs and Sigelman2002) used token ratio (the number of different words in an opinion as a percentage of the total number of words) (see also Cheruvu Reference Cheruvu2019), once-words (relative frequency of words that appeared exactly once in an opinion), text length, average word length, average sentence length, footnote frequency, and footnote length. Rosenthal and Yoon (Reference Rosenthal and Yoon2011) used the frequency of a set of 63 function words (words such as “a,” “all,” “also,” “an,” “and,” and “any”) to measure judgment standardization. These earlier studies were all based on bag-of-words models. These models convert texts into fixed-length vectors by simply counting the number of times a word appears in a document, a process referred to as vectorization.Footnote 6 The bag-of-words approach has two disadvantages: it loses all information about word order, and it does not encode any information about the context of words.

According to Deyevre (Reference Dyevre and Verbruggen2021), these disadvantages explain the recent turn toward the so-called distributed linguistic approach. The basic idea of the distributive linguistic approach is to encode information about the words appearing around the target word. It is based on the principle that “a word is defined by the company it keeps” (Firth Reference Firth1957). Building on this intuition, researchers at Google released Word2Vec in 2013 (Mikolov c.s. Reference Mikolov, Sutskever, Chen, Corrado and Dean2013). Word2vec is a neural network with a single hidden layer that uses word co-occurrence for learning a relatively low-dimensional vector representation of each word in a corpus, a so-called distributed representation (Hinton Reference Hinton Geoffrey1986). The neural network is trained by an unsupervised self-learning algorithm to predict the surrounding words given the target word. The vectors representing words are positioned in a high-dimensional space in such a way that vectors representing words sharing the same contexts are closer to one another. The vector length varies and depends on the consistency and frequency of word use, whereby vector length is longer as words are being used more consistently in different contexts and are being used more frequently. Vector length also depends on the interaction between these two factors: a word that is consistently used in a similar context will be represented by a longer vector than a word of the same frequency that is used in different contexts. Conversely, for fixed context, the vector length increases with term frequency. This means that vector length indicates the significance of words in documents (Schakel and Wilson Reference Schakel and Wilson2015).

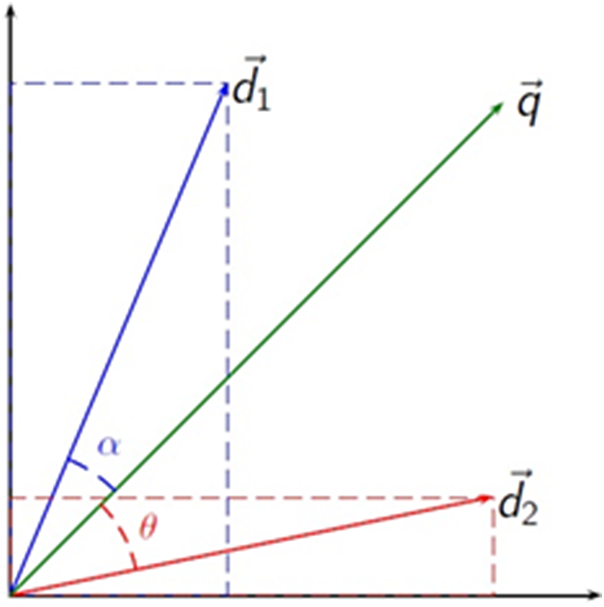

We used Doc2Vec to calculate vectors for entire documents. Dyevre (Reference Dyevre and Verbruggen2021) explains that Doc2Vec rests on the same neural network architecture and learning strategy as Word2Vec but learns document vectors on top of the word vectors. Like word vectors, document vectors are positioned in the high-dimensional space so that documents that are more similar have more proximate locations. The distance between document vectors becomes a measure of textual similarity. In our study, we calculated a document vector for each separate judgment in which a law clerk was mentioned and a vector for the corpus of all other judgments in which he or she was mentioned. In other words, we used a one-to-many comparison to establish the similarity between the specific judgment and the corpus of other judgments (Wang and Dong Reference Wang and Dong2020). The difference between each judgment and the corpus was calculated by the cosine similarity score (denoted by α or θ in Figure 1). We used the cosine similarity score because several comparative studies have shown that it usually outperforms other metrics of vector similarity (see, for example, Bullinaria and Levy Reference Bullinaria and Levy2007, 523, Reference Bullinaria and Levy2012, 891; Pennington c.s. Reference Pennington, Socher and Manning2014, note 4, 1537–8). The cosine similarity score is standardized and ranges between 0 and 1. A higher score indicated greater standardization.

Figure 1. Visual representation of the vector space model, where vector q is the judgment that was checked and vector d1/d2 is another document or a corpus (Riclas 2010).

The number of legal references was measured by counting the number of references to caselaw and legislation. The number of references to legislation was retrieved from the linked data portal of the Dutch government for each legal case.Footnote 7 References to previous ECLI cases were found using pattern matching.Footnote 8 A high score indicated that a judgment contained many legal references. References to other legal sources such as law reviews and learned materials have not been included in this measurement as these sources are referred to only in a minority of cases and are not listed in the data portal.

Law clerk experience

Our independent variable was the extent of law clerk experience, which was established in two steps. In the first step, we identified all clerks who co-signed a judgment and were mentioned in administrative law cases in 2020. In the second step, we determined the experience of these clerks. We used a machine learning model trained on Dutch news data from the open-source machine learning library spaCy to recognize the law clerks’ names (spaCy 2021). To prevent the machine learning library from identifying lawyers, experts, or judges as law clerks, the names were derived from the designated part in which the judgment was written rather than the integral text of the court case. A random manual check was performed on 150 cases that were tagged by the machine learning model. The model was retrained on 100 cases from which the law clerks’ names were derived manually.Footnote 9 This was done by feeding the manually checked names into the existing model. The untrained spaCy model proved to be accurate in 93% of the judgments. The retrained model had an accuracy score of 99%,Footnote 10 which means that the algorithm correctly identified the law clerk who co-signed the judgment.

We excluded two types of cases from the analysis. First, cases in which the judge’s and clerk’s names were identical were excluded.Footnote 11 This could happen in cases in which an aspirant judge was still operating as a law clerk, when a clerk became a judge in 2020, or simply by sheer coincidence. Second, cases were excluded from the analysis when the names of two different clerks were identical.Footnote 12 This occurred when clerks sharing the same name were working in different courts. The dataset contained 519 unique law clerks. The highest number of cases co-signed by a clerk was 64. Various clerks co-signed only one case. On average, clerks co-signed 9.6 cases.

The clerks’ experience levels were determined by taking the first occurrence of their names in any published judgment on the website of the Netherlands Council for the Judiciary. The date of this first occurrence was taken as the starting point of their professional experience. Clerk experience was calculated on a per-case basis by subtracting the date of the first occurrence of a name on the website of the Council for the Judiciary from the date on which the sample legal case was issued. Law clerk experience was measured in days. Some clerks’ names occurred only once in the dataset. In these cases, the law clerk experience was set at zero days. The indicator for clerk experience was a proxy for actual experience because it was likely that a clerk had been working for some time before the first judgment in which her/his name occurred was published online. However, we assumed that this unreliability evened out between law clerks in our sizeable dataset. Also, with this variable we measure the work experience as a law clerk and not the more general legal professional experience. For most clerks, their clerk experience will correspond with their legal professional experience, as for most clerks their clerkship is their first employment within the legal field. However, some clerks might have gained professional experience prior to starting their clerking position.

Control variables

The first control variable was the duration of judges’ experience. We included this control variable because judge experience may be linked to the extent to which a judge allowed law clerks to leave their fingerprints on judgments. As such, judge experience could have had an impact on the strength of the correlation between law clerk experience and the writing style of the judgment, but not necessarily its direction. There was some evidence that suggested that the extent to which judges permitted law clerks to influence the judicial decision-making process depended on the judge’s experience, but the results were inconclusive. Some studies have found that judges allowed law clerks less influence as the judges are more experienced (Black and Boyd Reference Black and Boyd2012; Yoon Reference Yoon2014; Holvast Reference Holvast2017), but the research by Black, Boyd, and Bryan (Reference Black, Boyd and Bryan2014) did not reach such a conclusion.

Judge experience was established by identifying the starting date of each judge’s professional career as reported in the public register of judges that is managed by the Netherlands Council of the Judiciary (Raad voor de Rechtspraak Reference voor de Rechtspraak2021a). Elasticsearch’s fuzzy string matching method (Elasticsearch match query 2021) was used to search for identical names and for names that were very similar to the names from the public register. The matching query accommodated spelling mistakes that were common in the language of the text; for example, the names “Thomspon” and “Thombson” were both recognized as “Thompson.” Judges with identical names were removed from the register because it was impossible to determine which judge had issued the judgment.Footnote 13 Judge experience was calculated on a per-case basis by subtracting the starting data as retrieved from the public register from the date on which the sample judgment was issued. For cases that were decided by a panel of judges, the experience of the presiding judge was used. A high score indicated that the judge had significant experience.

Second, we controlled for the court level that issued the judgment because it could have been linked to the writing style of the judgments. We expected that judgments made by first instance courts would be more elaborate than judgments by appellate courts, as the latter courts often refer to the first instance judgment to, for example, establish the facts of a case. Also, litigants regularly only appeal selected facets of a case. As judgments on first instance cases are typically more encompassing than judgments on appeal cases, such judgments were also expected to be longer, less standardized, and contain numerous legal references.

Third, we controlled for whether a case was decided by a single judge or a panel of judges. Again, we assumed that this variable was linked to the writing style of the judgments. Less complex cases are typically decided by a single judge, while more complex cases are often decided by a panel of judges. We expected that simple cases would result in short, standardized judgments containing few legal references. We coded judgments that mentioned the name of one judge as single-judge cases, while judgments that mentioned three or five judges were coded as panel cases. Twenty cases were discarded in which more than five judges were identified.Footnote 14

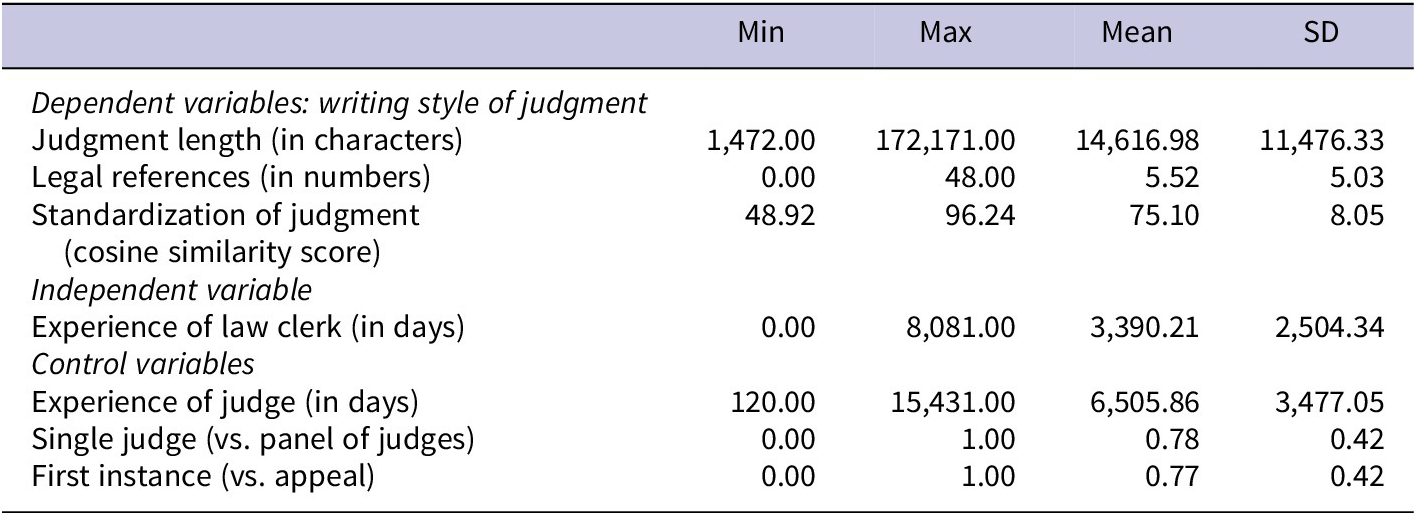

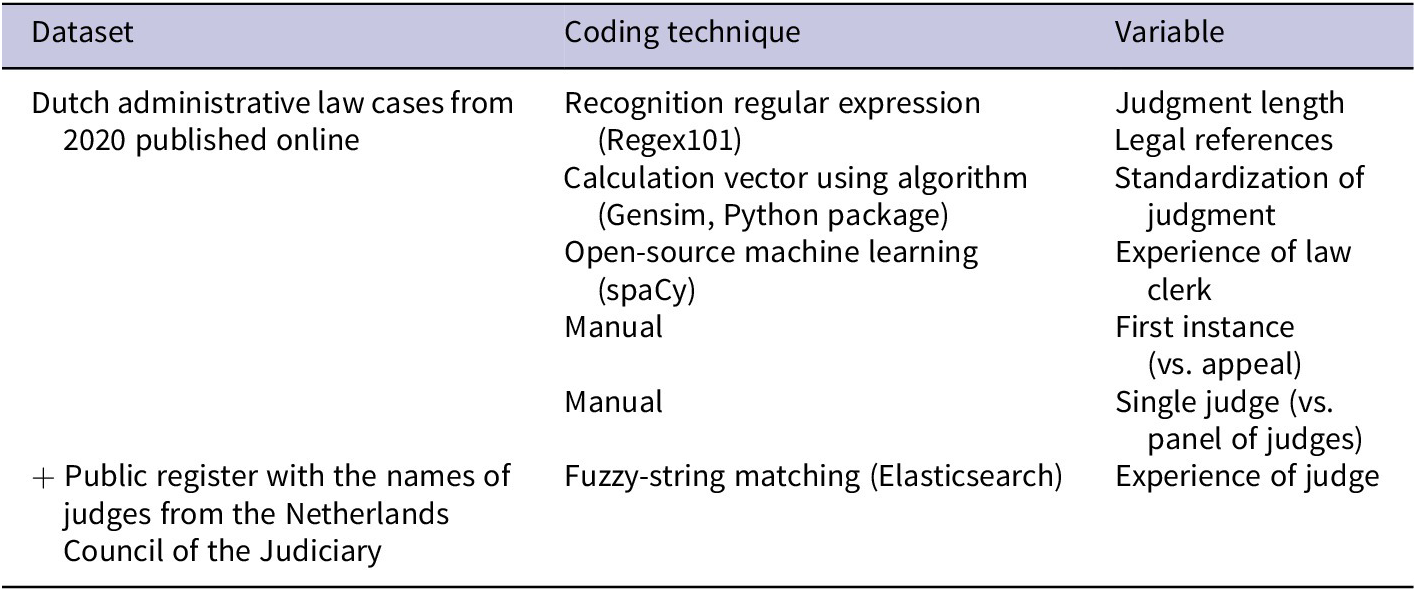

Finally, we controlled for the two style components that were not the dependent variables in any of the three regression analyses because the three components may have been correlated. To prevent variance being attributed to the wrong component of the writing style of judgments, we controlled for the two components that were not dependent variables in the multivariate analyses. For instance, in the analysis explaining the judgment length, we controlled for standardization and number of legal references. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of all variables. Table 2 lists the datasets and techniques that were used to code all variables.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of All Variables (N = 4,643)

Table 2. Description of the Dataset and Technique Used to Code Variables

Analysis

The analysis consisted of two steps. The first step involved calculating the bivariate Pearson correlations between all variables. The second step consisted of conducting three separate multivariate analyses in which law clerk experience was regressed against one of the components of the judgment writing style – judgment length, judgment standardization, or number of legal references – while controlling for six variables. The regression equations were based on ordinary least squares.

Results

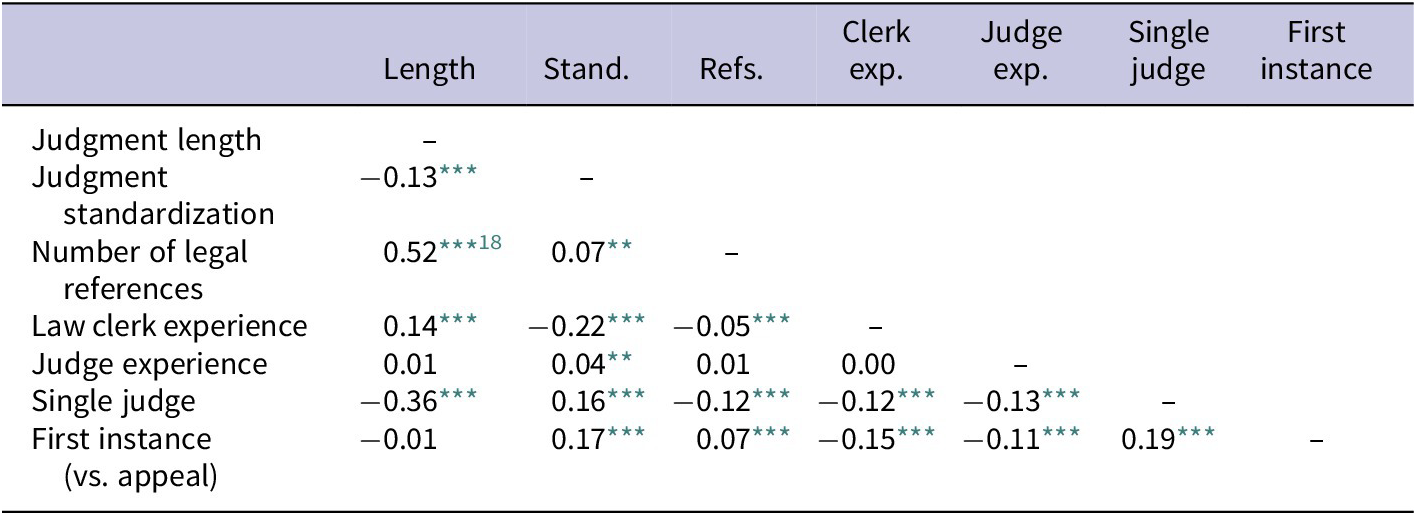

Table 3 shows the bivariate Pearson correlations (two-tailed) between all variables. The correlations between judicial experience and the three components of judgment writing style gave a first indication of the test results of the confidence hypothesis. In terms of this hypothesis, negative correlations were expected between law clerk experience and judgment length, judgment standardization, and number of legal references. In fact, law clerk experience was positively correlated to judgment length (r = 0.13, statistically significant at the 0.1% level) and negatively correlated to judgment standardization (r = −0.22, statistically significant at the 0.1% level) and the number of references (r = −0.05, statistically significant at the 0.1% level). These findings were not supportive of part a of the confidence hypothesis, while they were supportive of part b and c of the hypothesis. However, the bivariate correlations were not controlled for potential confounding variables, as was done in the multivariate regression analyses.

Table 3. Correlation Coefficients (N = 4,642)

Note: As it was theorized that confidently written judgments would be indicated by short and unstandardized judgments that contained few legal references, high scores for the components of the writing style indicated short judgments, unstandardized judgments, and judgments containing few legal references.

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01

*** p < 0.001

Table 3 also shows how the three components of the writing style correlated with the control variables and with one another. The judge’s experience was not correlated to any of the three components of the writing style. This was consistent with the presumption that a judge’s experience may determine how much influence he or she allows law clerks in drafting judgments, but not how that influence may be manifested. Furthermore, several of the court case characteristics correlated significantly with one or more components of the writing style. Judgments of single judges were shorter (r = −0.36, statistically significant at the 0.1% level), more standardized (r = 0.16, statistically significant at the 0.1% level), and contained fewer legal references (r = −.012, statistically significant at the 0.1% level) than cases decided by a judicial panel. As such cases are typically not complex, these correlations were as expected. First instance cases were not shorter or longer than appellate cases, but they were less standardized (r = 0.16, statistically significant at the 0.1% level) and contained more legal references (0.07, statistically significant at the 0.1% level). As first instance cases are expected to be judged more comprehensively than appeal cases, this finding was not surprising.

The results also showed that the three components of the writing style were correlated. Judgment length was negatively correlated to judgment standardization (r = −0.13, statistically significant at the 0.1% level) and positively to the number of legal references (r = 0.52, statistically significant at the 0.1% level), while judgment standardization was positively correlated with the number of legal references (r = 0.07, statistically significant at the 1% level). This means that longer judgments were less standardized and contained more legal references, while more standardized judgments also contained more legal references. These correlations make sense because longer judgments increase the potential for expressions and legal references, while references to court cases and legislation are likely to be referred to in similar ways across multiple judgments. However, except for the correlation between judgment length and number of legal references, the correlations were weak. In the next multivariate regression analyses, we show to what extent the correlations were affected by the control variables.

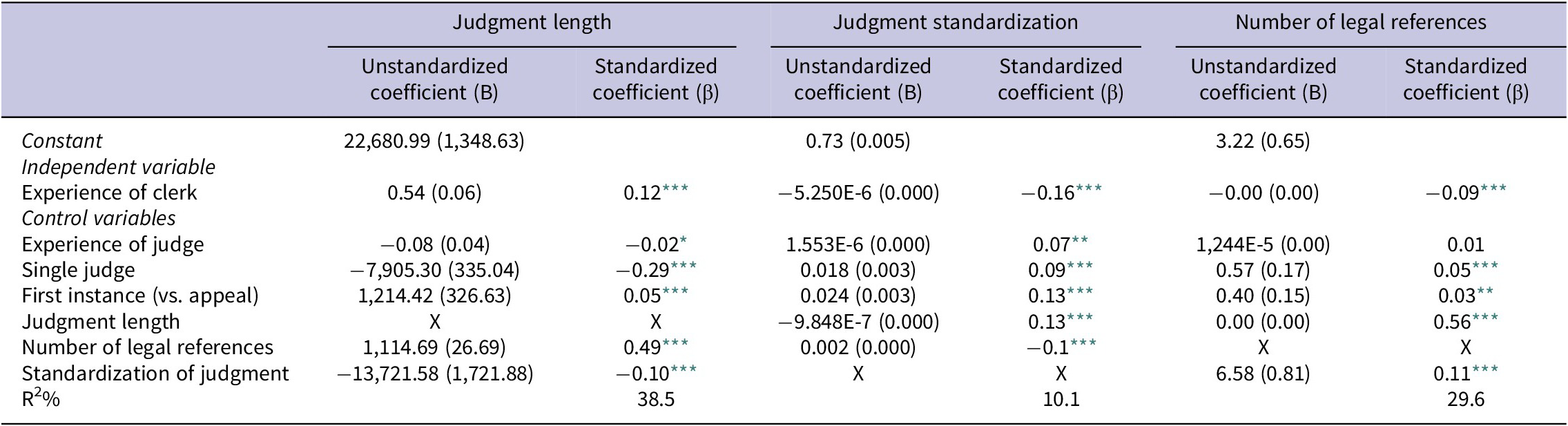

Table 4 presents the separate regression equations for each of the three components of the writing style. It contains six columns: the first two columns explain the variation in judgment length, with the first column showing the unstandardized coefficients (B) and the second column showing the standardized coefficients (β). The following columns concern the unstandardized and standardized regression coefficients for judgment standardization and the number of legal references. The results of the separate regression equations will be discussed in conjunction because the confidence hypothesis addresses all three components of judgment writing style at the same time.

Table 4. Regression of the Three Components of Judgment Writing Style (Length, Standardization, and Number of Legal References) against the Law Clerks’ Experience, Controlled for Five Variables (N = 4,642)

Note: Table entries are ordinary least squares coefficients (unstandardized and standardized) with standardized errors on components of the writing style in parentheses.

For standardization of judgments, the unstandardized coefficients (B) cannot be interpreted meaningfully because the cosine similarity score is already standardized.

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01

*** p < 0.001

The standardized regression coefficients (columns 2, 4, and 6) show that whereas the regression coefficient between clerk’s experience and judgment length is positive (β = 0.12, statistically significant at the 0.1% level), the regression coefficients between clerk’s experience and judgment standardization (β = −0.16, statistically significant at the 0.1% level) and clerk’s experience and number of legal references (β = −0.09, statistically significant at the 0.1% level) are negative. This means that judgments were longer, while at the same time less standardized and contained fewer legal references as law clerk experience increased. The unstandardized regression coefficients (columns 1 and 5) show that, for each 100 days of experience, judgments became approximately 53 words longer, while the decrease in the number of references to caselaw or legislation was negligible. In other words, although both highly significant, the connection between experience and writing style was much more discernible in terms of judgment length than the number of legal references. These findings contradicted part a of the confidence hypothesis but supported parts b and c of the hypothesis; more experienced clerks wrote longer judgments that were much less standardized and contained slightly fewer legal references.

A potential explanation for the finding that judgments written by experienced law clerks were longer can be found in the differences in terms of complexity of cases that law clerks work on. Possibly, more experienced law clerks work on more complex cases, which also demand more words to explain the judicial decision. We controlled for a number of case characteristics (single-judge or panel, first instance or appeal decisions, standardization of judgments, and number of legal references). However, given the large variation of administrative law cases, it is conceivable that we omitted other variables that could co-determine the complexity of cases: for example, the ambiguity of the relevant legislation, the number of litigants involved, or the financial complexities. It is plausible that the variables of judgment standardization and number of references were also connected to case complexity. However, we suspect that these connections were less strong than the one between length of judgments and case complexity. That is, clerks are likely to have more discretion in determining the level of standardization or the number of references than in determining the length of judgments. For judgment length, we expected law clerks to have less of a choice; a judgment in a very complex case that deals with many different legal issues naturally will be longer than the judgment for a clear-cut case.

Yet, it remains to be seen to what extent our finding that experienced law clerks write longer judgments can be explained by them working on more complex cases. What speaks against this explanation is that, in the Dutch judiciary, at least formally, cases are usually randomly assigned to judges (and law clerks), based on the availability of the judges/clerks.Footnote 15 It is only in certain cases that exceptions to the rule of random allocation can be made.Footnote 16 This suggests that it is not likely that the greater complexity of cases worked on by experienced law clerks compared to inexperienced law clerks explains why experienced law clerks write longer judgments. However, the Dutch judiciary has been critiqued for not being very transparent about the allocation process (Van Emmerik and Schuurmans Reference Van Emmerick and Schuurmans2016), which means that, in practice, it may still make a difference.Footnote 17 Further research is needed to test whether experienced law clerks write longer judgments because they work on more complex cases.

Table 4 also shows the regression coefficients between the control variables and the components of the writing style. The regression coefficient between judge experience and judgment length was negative (β = −0.02, statistically significant at the 5% level), and the regression coefficient between judge experience and judgment standardization was positive (β = 0.07, statistically significant at the 0.1% level), while the regression coefficient between judge experience and the number of legal references was not significant. However, the regression coefficient between judge experience and judgment length was weak (8 fewer words per 100 days of experience) and significant only at the lowest level (5%). These findings suggest that judges not only adjust the amount of stylistic influence they allow law clerks when delegating drafting duties but also that judges leave their own stylistic fingerprints on judgments.

The different case characteristics were also connected to different components of the writing style. Single-judge cases were (on average, 7,905 words) shorter, more standardized, and contained more legal references (0.57) than cases decided by a panel of judges. As single-judge cases are typically less complex than judicial panel cases, the direction of the regression coefficients were as expected in terms of length and standardization but not in terms of number of references. It is possible that single judges are inclined to refer to all case law and legislation they deem relevant for court cases, while panels of judges may be inclined to only refer to legal sources when panelists agree on their relevance. Furthermore, first instance cases were (on average, 1,214 words) longer, more standardized, and contained more references (0.40) than appeals. Because appeals on administrative law cases can refer to the reasoning of the first instance judgment and do not always deal with all the legal issues that were initially raised, these correlations were as expected.

The regression coefficients between the different components of the writing style of the judgments were similar to the correlations reported in Table 3: the lengthier the judgment, the less its language was standardized and the more legal references it contained (each additional reference added approximately 1,115 words to a judgment), while judgments contained more legal references the more standardized they were. As mentioned above, these connections suggested that words are needed to refer to court cases and legislation, while legal references increased judgment standardization because such references were made in similar ways across multiple judgments.

The total amount of variance in judgment length that was explained by all variables included in the model was 38.5 percent. The total amount of explained variance in judgment standardization was 10.1 percent, and the total amount of explained variance in the number of legal references was 29.6 percent.

Conclusion and discussion

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that experienced law clerks are more confident in terms of drafting judgments than relatively inexperienced law clerks. Our findings showed that judgments co-signed by law clerks were less standardized and contained fewer legal references as law clerk experience increased, which supported our hypothesis. However, contrary to our confidence hypothesis, we established that judgments co-signed by more experienced law clerks were also longer. We suggest that experienced law clerks write longer judgments because they are involved in more complex cases than inexperienced clerks, while complex cases require longer judgments than simple cases. While we controlled for several case characteristics, we may still have omitted variables that would indicate the complexity of court cases. If our assumption is correct that experienced law clerks write comparatively lengthy judgments because they are involved in relatively complex cases, then this finding is unrelated to the level of confidence in terms of writing judgments. We conclude that the level of experience of law clerks who are involved in drafting judgments affects the writing style of judgments and that this may well be due to clerks’ confidence in drafting judgments.

In addition to the potential omission of control variables that were related to case complexity, two limitations of the research should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the actual process of conceiving a judgment has remained a “black box” in our study. We know from previous research that, in administrative law courts in the Netherlands, law clerks are regularly involved in judgment writing, and it is common practice that law clerks conceive first drafts (Holvast Reference Holvast2017, 148). As such, it may be safe to assume that the majority of judgments are drafted by law clerks. However, it remains unknown how much feedback judges offer on writing style and/or how many style amendments are made by judges.

Second, we conducted our analysis on all published administrative law judgments in the year 2020. Even though this provided us with a large dataset of 4,961cases, in which 322 unique judges and 519 unique law clerks were involved, the dataset contained only 5.9% of all administrative law cases that were decided in 2020. Therefore, our findings may not be representative of all administrative law decisions. As relevance to the development of law is a criterion for publication of court cases, our dataset is particularly likely to underrepresent routine cases. We are unable to speculate about how this underrepresentation of routine cases may have affected our findings.

Bearing these limitations in mind, our study contributes to the literature by contextualizing the concerns expressed in studies on the US Supreme Court about the delegation of drafting duties to inexperienced law clerks. While researchers are concerned that, in the US Supreme Court, delegating drafting duties to law clerks is accompanied by a writing style that lacks the confidence of judgments written by Justices, our findings demonstrated that this concern is not necessarily justified for courts that employ a scribe model of clerking. In jurisdictions in which law clerks can be as experienced as judges (in terms of years worked in the legal field) because they occupy permanent positions rather than temporary internships, law clerks appear to increasingly rely on their own writing style as they gain experience. This means that, in such a setting, experienced lawyers leave their own stylistic “fingerprints” on judgments, regardless of whether they are law clerks or judges.

Adding to previous research on the manner in which judges try to control the undesired influence of clerks on judicial decision-making (Mascini and Holvast Reference Mascini and Holvast2020), this study suggests that the findings of the extant research on law clerks’ influence in the US Supreme Court cannot necessarily be generalized to other jurisdictions. This confirms the importance of considering the differences between court structures and procedures when interpreting research findings. It also emphasizes the relevance of conducting research in different court settings and jurisdictions (see also the special issue of the International Journal for Court Administration on Empirical Studies on the Role and Influence of Judicial Assistants and Tribunal Secretaries, vol. 11, issue 3, 2020). Furthermore, results from research in various settings can enrich the academic debate regarding the US as research suggests that the negative impact of delegating drafting duties may be mitigated by appointing experienced clerks or extending the period for which they are appointed (see also Rosenthal and Yoon Reference Rosenthal and Yoon2011).

One could object to our study by arguing that transforming the judge from a draftsman to an editor takes away from the judge the opportunity to reconsider his or her reasoning by writing a judgment. This argument may be true when it comes to the judge, but it overlooks the possibility that the very same opportunities that are offered by writing judgments are transferred from the judge to the law clerk when drafting duties are delegated. Hence, it raises the question whether law clerks (who are clearly involved in writing judgments in a different capacity) can gain similar insights via judgment writing. If the answer is in the affirmative, then the concerns related to this objection are not necessarily justified.

From our discussion, we derive three avenues for follow-up research. First, it would be valuable to replicate this research in different areas of law and in different jurisdictions that employ a scribe model of clerking. This would help determine the robustness and reach of our findings. Second, it is worthwhile to explore how factors other than experience, such as language proficiency (see, for instance, Cheruvu Reference Cheruvu2019), may be related to writing style characteristics. Last, our confidence hypothesis could be tested on a more similar set of specific cases than those used in this study. Limiting the dataset to cases that are more alike in terms of case characteristics such as complexity could avoid the risk of establishing spurious relationships because of the variance in the experience of clerks involved in different types of cases.

Acknowledgments

Jonathan was involved in this study as a third researcher. He collected and coded the data on which this article is based for his master’s thesis. Jonathan was offered but declined co-authorship and did not want his surname to be revealed in the acknowledgments. He did, however, grant his approval for publication by the authors. We thank him for that, as well as for all the work he completed for this study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The replication materials are available at the Journal’s Dataverse archive.