Introduction

The popularity of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and support for it among stakeholders are higher than ever (Ramasamy & Yeung, Reference Ramasamy and Yeung2008), owing to increased awareness and understanding of CSR in society as a whole (Reverte, Reference Reverte2009). In response to social demands, companies have tried to achieve business goals as well as maintain social legitimacy for continued existence in a society by focusing on what interests stakeholders and how to engage with them (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Freeman, Reference Freeman1984). The resulting social pressure facilitates isomorphism among companies, a process by which those in similar social environments come to resemble each other. Isomorphism may lead to the diffusion of CSR practice, although considerable differences exist among companies in the timing of CSR adoption and the level of CSR implementation, even within the same country (Reverte, Reference Reverte2009). In this study, we explore how two different external factors, competitive pressure and institutional (mimetic) pressure, can help explain differences in the timing of CSR adoption behavior and thus the diffusion of CSR adoption.

Past empirical studies based on both economics framework (competitive pressure) and institutional theory (mimetic isomorphism) used the number of other firms to measure follow-the-leader behavior. These theories explain the same behavior, but the explanations differ. While the adoption of CSR behavior is supposed to be motivated by the company's willingness to support the wellness of society and a desire to gain social legitimacy, we refined measurements of follow-the-leader behavior and show that a strong economic motivation to adopt CSR exists alongside the social motivation. This economic motivation arises from a desire to remain competitive in the market.

The approach from the institutional perspective offers an explanation for the corporate isomorphism phenomenon – that is, the development of a resemblance between corporate behaviors in a similar social environment – which is fostered by an uncertain external environment (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983). Isomorphism enables companies' efficient use of resources by minimizing their initial cost of investigation (Cyert & March, Reference Cyert and March1963), and it provides legitimacy through recognition and approval from society and from other organizations (Meyer & Rowan, Reference Meyer and Rowan1977). From a sociological perspective, the concept of isomorphism explains organizational behaviors such as market entry, organizational structure, and investment decisions (Lieberman & Asaba, Reference Lieberman and Asaba2006; Salomon & Wu, Reference Salomon and Wu2012). Because a company's decisions regarding CSR adoption and implementation can be influenced by actions of other companies, this process is also considered to exemplify isomorphism. In other words, isomorphism is a means of adapting to the institutional environment.

On the other hand, many prior studies have recognized similar organizational behaviors among companies, and analyzed diffusion mainly as the outcome of the competitive process (Haleblian, McNamara, Kolev, & Dykes, Reference Haleblian, McNamara, Kolev and Dykes2012; Knickerbocker, Reference Knickerbocker1973), rather than the result of social pressure. For rivalry reduction or risk minimization, firms tend to intentionally make strategic decisions based on competitors' prior actions (Knickerbocker, Reference Knickerbocker1973; Leary & Roberts, Reference Leary and Roberts2014; Lieberman & Asaba, Reference Lieberman and Asaba2006). Oligopolistic reaction literature, a representative body of competitive reaction studies, has focused on various types of follow-the-leader behaviors.

So far, only a few studies have examined how competitors' CSR implementation influences a firm's own CSR behavior. For example, some research has revealed (positive) effects of peer firms' CSR policy (Lin & Chih, Reference Lin and Chih2016), gender equality information disclosure (García-Sánchez, Minutiello, & Tettamanzi, Reference García-Sánchez, Minutiello and Tettamanzi2022), adoption of CSR proposals at annual shareholder meetings (Cao, Liang, & Zhan, Reference Cao, Liang and Zhan2019), and the CSR performance level (Yang, Ye, & Zhu, Reference Yang, Ye and Zhu2017). In most of these studies, however, peer pressure from industry rivals has been assessed on the basis of industry average values rather than each rival company's behaviors (Tuo, Yu, & Zhang, Reference Tuo, Yu and Zhang2020), and the possible influence of institutional environment has not been considered. As Leary and Roberts (Reference Leary and Roberts2014) and Tuo, Yu, and Zhang (Reference Tuo, Yu and Zhang2020) noted, the use of industry average values and the omission of institutional environmental variables can lead to possible empirical problems that may hinder determining whether a firm's specific behavior is led by its rival firms' similar behaviors, since none of those studies has simultaneously examined the potential effect of the institutional environment. Moreover, since most studies have not paid attention to each rival's prior actions, they have not investigated diffusion and adoption of CSR behaviors from a competitive reaction perspective based on game theoretic framework. In other words, the existing CSR literature has not yet fully considered a competitive reaction perspective. Although CSR can be considered as non-market behaviors (Sirsly & Lamertz, Reference Sirsly and Lamertz2008), firms would also make strategic decisions in terms of CSR adoption or its timing, considering their rivals' prior actions or its resulting benefits and costs.

The outcomes of CSR have received more research attention than its preconditions or drivers (Höllerer, Reference Höllerer2013). Research on the preconditions or drivers of CSR has only recently appeared (e.g., Höllerer, Reference Höllerer2013). In recent years, some of the frequently identified drivers of CSR include firm-level characteristics such as firm size (Hahn & Kühnen, Reference Hahn and Kühnen2013; Li, Lu, & Nassar, Reference Li, Lu and Nassar2021), ownership structure (Dalla Via & Perego, Reference Dalla Via and Perego2018; Höllerer, Reference Höllerer2013), and managerial attributes (e.g., McCarthy, Oliver, & Song, Reference McCarthy, Oliver and Song2017). External factors have also been examined as drivers of CSR, including environmental incidents such as the BP oil spill (e.g., Heflin & Wallace, Reference Heflin and Wallace2017) or stakeholder pressure (Huang & Watson, Reference Huang and Watson2015). However, sufficient knowledge is still lacking with regard to how and why firms adopt CSR and how this behavior may spread across firms facing the same or similar institutional pressures (Caprar & Neville, Reference Caprar and Neville2012; Fransen, Reference Fransen2012). Specifically, simultaneous competitive pressures and institutional factors have not yet been fully explored as potential determinants of CSR adoption and diffusion. Thus, our study builds upon prior literature on the diffusion of CSR by incorporating its adoption by competitors as a potential influence. Using this perspective, we investigate whether two pressures – competitive and mimetic – work as main drivers of a firm's CSR adoption decision, possibly leading to diffusion across firms in the same institutional context. In doing so, our study provides a new perspective on the determinants of the spread of voluntary CSR adoption.

Owing to its multifaceted nature, which encompasses different ranges or aspects of responsibility, CSR has been defined and conceptualized from various perspectives, rather than one unified point of view (Aguinis & Glavas, Reference Aguinis and Glavas2012; Gjølberg, Reference Gjølberg2009; Höllerer, Reference Höllerer2013; Lu & Abeysekera, Reference Lu and Abeysekera2017; van Marrewijk, Reference Van Marrewijk2003). It should be noted that the inherent difficulties and complexities in defining CSR have led to the development and application of multiple ways to measure it (Campbell, Reference Campbell2006; Gjølberg, Reference Gjølberg2009). Consequently, various approaches have been used to observe and measure whether, when, and how companies have adopted CSR and how they are implementing and performing it (Gjølberg, Reference Gjølberg2009; Orlitzky, Schmidt, & Rynes, Reference Orlitzky, Schmidt and Rynes2003). One way that firms communicate their CSR-related actions to their stakeholders is through voluntary disclosure of their involvement and performance. Accordingly, we operationalize the measurement of CSR adoption by using firms' own CSR reporting because it officially conveys their specific actions and outcome, not merely declarative commitment, which can be made before actual adoption (Caprar & Neville, Reference Caprar and Neville2012). In particular, we regard firms that have previously reported their CSR performance and its outcome as having adopted or implemented CSR.

This research defines the diffusion of CSR adoption as the expansion of the phenomenon of voluntary CSR reporting from the first reporting firm to other firms in a market. Therefore, our focus is on differences in the timing of CSR adoption based on the year in which each firm's initial CSR report is published. CSR or sustainability reports have been used as a main conduit for companies to officially communicate their CSR activities, performance, and outcomes to their stakeholders, despite the lack of any standardized rule or mandatory requirement for doing so (Reverte, Reference Reverte2009). However, this framework should be applied to different institutional contexts with care, because several countries have legislation that establishes reporting requirements (Christensen, Hail, & Leuz, Reference Christensen, Hail and Leuz2021) based on a firm's size or on a specific industry. Regulatory mandates may accelerate CSR practice adoption within those countries (Haberberg, Gander, Rieple, Martin-Castilla, & Helm, Reference Haberberg, Gander, Rieple, Martin-Castilla and Helm2007), which include Denmark, France, India, Indonesia, Japan, Nigeria, South Africa, and the United States (KPMG, 2013). Therefore, we view companies as having officially adopted and implemented CSR when they voluntarily disclose their CSR information.

To analyze the potential determinants of CSR diffusion, we focus on two different types of factors simultaneously: competitive pressures and institutional (mimetic) pressures. The competitive pressures accrue from the preceding behavior of a firm's competitors within the same industry. Institutional (mimetic) pressures potentially include the behavior of non-competitor companies outside the industry. This research therefore investigates whether and how these two types of pressures are associated with the CSR adoption decision within the same country context leading to the diffusion of CSR adoption.

Research framework and hypotheses

Determinants of the diffusion of similar organizational practices, such as the adoption of CSR, diversification in different industries, and the entry into new foreign countries, have been investigated and analyzed from multiple perspectives. Many researchers studied the determinants based on institutional perspectives such as mimetic isomorphism, which explains the existence of similar organizational practices as the outcome of efforts to gain social legitimacy and mitigate risk while responding to uncertainty in the given environment (e.g., DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983). Mimetic isomorphism refers to mimicking the behavior of another organization that is perceived as a legitimate and successful way of handling problems with ambiguous causes or unclear solutions (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983). It emphasizes behavior based on social considerations (social legitimacy); competitive interaction, such as game theoretical payoff consideration, is not the first focus.

In terms of the research on imitative behavior of CSR-related practices, the mimetic isomorphism approach has been used to further study various CSR adoption decisions. Comyns (Reference Comyns2016) showed how firms respond to institutional pressures regarding the greenhouse gas disclosure in the extractive (oil and gas) industry. Similarly, Fierro, Sanagustín-Fons, & Alonso (Reference Fierro, Sanagustín-Fons and Alonso2020) investigated the drivers of environmental and social reporting, identifying the role of mimetic isomorphism in the context of the energy industry.

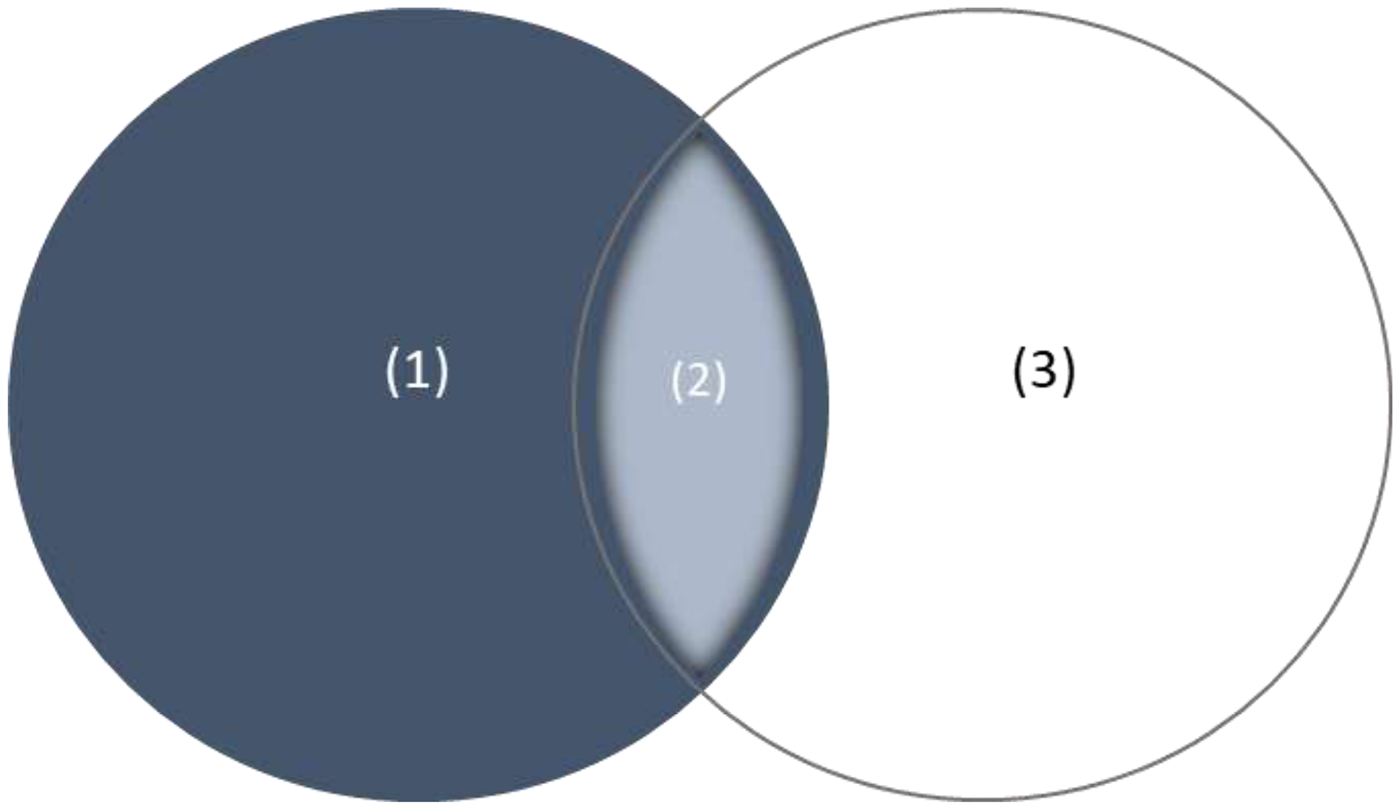

However, a survey conducted by the United Nations Environmental Program found that competitive pressure was one of the most important reasons for firms to make a CSR reporting decision (Levy, Brown, & De Jong, Reference Levy, Brown and De Jong2010). Other studies, such as Nikolaeva and Bicho (Reference Nikolaeva and Bicho2011), considered the pressure from stakeholders (e.g., competitive pressure) as part of institutional pressure and did not distinguish between them. Thus, further study is needed to obtain insights from a more integrated approach including both mimetic isomorphism and competitive pressure perspectives. Past empirical studies based on the two different perspectives used the same measurement (the number of other firms) to measure the imitative behavior. To clarify these two similar but different aspects of follow-the-leader behavior, we refine the measurements and tease out each contributing factor's effects (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Competitive pressure and Institutional mimetic pressure. (1) = Non-leader rivals in the same industry (pure competitive pressure). (2) = Industry leader rival in the same industry (potential dual pressure). (3) = Non-rivals in other industries (institutional mimetic pressure). H1a: (1) + (2) Competitive pressure from the same industry rivals. H1b: (1) Pure competitive pressure from non-leader rivals only, controlling for potential dual pressure from industry leader. H2a: (3) Institutional mimetic pressure from non-rivals in other industries (all prior years). H2b: (3) Institutional mimetic pressure from non-rivals in other industries (immediate prior year).

Competitive interaction literature in economics, such as research on the oligopolistic reaction (Knickerbocker, Reference Knickerbocker1973), does not consider social legitimacy as a primary explanation for the follow-the-leader phenomenon. In this body of literature, rivals' behavior – whether they are large or small, successful or unsuccessful, socially legitimate or not – may affect the focal company's bottom line because the rivals may learn some new skills, gain knowledge about technologies developed in a host country, get the first-movers' advantages in a new market, and so forth. The focal company's performance may be affected negatively if it does not follow its rivals (Knickerbocker, Reference Knickerbocker1973). Given the expected underperformance of non-adopters, competitive bandwagon pressure can occur among firms in the same industry (Abrahamson & Rosenkopf, Reference Abrahamson and Rosenkopf1993) and lead remaining non-adopters to follow. Furthermore, rivals are not always ‘socially legitimate’ from this perspective because non-leader rivals are not necessarily considered to be ‘successful’ in the same industry.

Prior literature defines competitive pressure primarily as pressure arising from the intensity of market competition (e.g., Dupire & M'Zali, Reference Dupire and M'Zali2018; Frias-Aceituno, Rodríguez-Ariza, & Garcia-Sánchez, Reference Frias-Aceituno, Rodríguez-Ariza and Garcia-Sánchez2014) or pressure induced by the previous actions of competitors (e.g., Knickerbocker, Reference Knickerbocker1973; Li, Yin, Shi, & Yi, Reference Li, Yin, Shi and Yi2020; Liu & Wu, Reference Liu and Wu2016). Similarly, most of the empirical research on inter-organizational imitative CSR behaviors has until recently included competitive pressure as a moderator or a control variable, rather than as a main predictor, with the assumption that it has indirect or limited influence on firms' willingness to adopt or follow (e.g., Cano-Rodríguez, Márquez-Illescas, & Núñez-Níckel, Reference Cano-Rodríguez, Márquez-Illescas and Núñez-Níckel2017; Nikolaeva, Reference Nikolaeva2014). Although previous studies have provided some useful knowledge, we observe that relatively little attention has been paid to the role of competitive pressure, particularly as a main predictor of the spread of CSR adoption. A limited number of recent studies have investigated the effect of rivals' behaviors on various CSR behaviors through a competitive lens, but they were only centered on the effect of market competition itself or competitors' actions and therefore did not simultaneously consider the potential effect of mimetic isomorphism. Furthermore, there remains an unexplained aspect regarding how competitive pressure from competitors' previous actions could prompt the imitative CSR adoption as a reaction by firms in the same industry sector that eventually leads to the diffusion. Therefore, we aim to complement the literature about the determinants of the spread of CSR adoption.

Competitive pressure

One of the first empirical studies of the follow-the-leader phenomenon was done by Knickerbocker (Reference Knickerbocker1973), and it was followed by a stream of research on imitative behavior in foreign direct investment. Previous international business literature refers to such behavior by multinational enterprises as an oligopolistic reaction, which is also known as bandwagon effect, herding behavior, or bunching behavior (e.g., Head, Mayer, & Ries, Reference Head, Mayer and Ries2002; Knickerbocker, Reference Knickerbocker1973; Yu & Ito, Reference Yu and Ito1988). These behaviors involve each focal firm following or copying the actions or decisions of other firms that are rivals in the same industry. Thus, imitative behaviors of competing firms are observed. In very competitive markets, companies seek to strengthen their positions by checking themselves against competitors in the same industry. Yu and Ito (Reference Yu and Ito1988) reported that firms' reactions to competitors' behavior depend on the types of competition within an industry. Rose and Ito (Reference Rose and Ito2008) analyzed Japanese automobile manufacturing firms' overseas investment decisions in terms of location and timing. Contrary to previous studies, they found that Japanese automobile firms tend to avoid overseas markets where competitors already exist. Moreover, the timing of entry into an overseas market is likely to be delayed if the foreign market is crowded with competitors. In other words, competitive rivalry within the same industry does not always lead to mimetic behavior; it may instead prompt an opposite response. Thus, although they are similar pressures exerted by the external environment, competitive rivalry (oligopolistic behavior) and mimetic isomorphism (social legitimacy) can differ in nature and be measured separately.

Within the research on inter-organizational imitative CSR behavior, a limited number of studies have considered competitive pressure (exerted by industry competitors) as a potential separate force. For example, Cano-Rodríguez, Márquez-Illescas, and Núñez-Níckel (Reference Cano-Rodríguez, Márquez-Illescas and Núñez-Níckel2017) analyzed how the intensity of competition plays a role in moderating individual firms' willingness to imitate other rival firms' CSR information disclosure practices. The researchers reported that firms are more likely to follow those practices when operating in more competitive markets. Through conducting a survey, focus group study, and interviews, Park and Ghauri (Reference Park and Ghauri2015) found that competitors' CSR practices constituted one of the primary motivators inducing CSR behavior of small and medium-sized MNE subsidiaries in Korea. Studying the peer effect of CSR, Liu and Wu (Reference Liu and Wu2016) documented a positive relationship between the level of rivals' CSR and CSR behavior of firms. Tyler et al. (Reference Tyler, Lahneman, Beukel, Cerrato, Minciullo, Spielmann and Discua Cruz2020) examined how firm managers' perceptions of competitive pressure are associated with the adoption of environmental practices in the wine industry context. Interestingly, they found a negative relationship in that SMEs' adoption of environmental practices is expected if weaker competitive pressure to adopt such practice is perceived by their managers.

The strand of literature emphasizing the strategic nature of social behavior of firms suggests that CSR behaviors may be initiated with strategic purposes (Dupire & M'Zali, Reference Dupire and M'Zali2018). If CSR is considered as part of a competitive strategy (Flammer, Reference Flammer2015), the effort to implement CSR can contribute to corporate profits and competitiveness (Gueterbock, Reference Gueterbock2004; Juholin, Reference Juholin2004). That is, even though profit is not guaranteed at the outset, a rival's adoption and implementation of a CSR strategy can motivate other firms within the same industry to do the same (Lieberman & Asaba, Reference Lieberman and Asaba2006; Liu & Wu, Reference Liu and Wu2016). Based on their strategic considerations, follower firms would try to make an appropriate decision on whether or not to adopt CSR, when to do so, and so forth in an effort to improve its competitiveness since firms recognize that it may be possible to achieve a competitive advantage in economic and social aspects through a CSR initiative (Sirsly & Lamertz, Reference Sirsly and Lamertz2008). In other words, firms are expected to make a decision to behave or react in a way to protect their competitive position in a market (Head, Mayer, & Ries, Reference Head, Mayer and Ries2002; Knickerbocker, Reference Knickerbocker1973).

Follower firms may view a non-adoption decision as potentially leading to unavoidable penalties or threats to their performance (Haberberg et al., Reference Haberberg, Gander, Rieple, Martin-Castilla and Helm2007; Haberberg, Gander, Rieple, Helm, & Martin-Castilla, Reference Haberberg, Gander, Rieple, Helm and Martin-Castilla2010; Nikolaeva, Reference Nikolaeva2014). To avoid such predictable disadvantages or unfavorable outcomes, firms may choose to follow the adoption behaviors (Abrahamson & Rosenkopf, Reference Abrahamson and Rosenkopf1993). Meanwhile, some pioneering firms may aim to provoke competing firms to become involved in CSR activities, expecting them to pay a similar additional cost from CSR practices (Vogel, Reference Vogel2005) or encouraging them to contribute to improve the overall reputation of the industry (Kopel, Reference Kopel2021). Consequently, initiation by the first movers is likely to result in the attention and participation of a group of rival companies in the same industry and thus lead to quicker diffusion among them.

Hypothesis 1a. Earlier adoption of CSR by industry competitors is related to quicker adoption by the focal firm in the same industry.

Among an industry's rival companies, however, industry leadership status of specific competitors might affect a firm's reaction behavior in different ways (Giachetti & Lampel, Reference Giachetti and Lampel2010). More specifically, an industry leader, as the largest and strongest competitor within the same market, can be targeted for competition or challenge (Smith, Ferrier, & Grimm, Reference Smith, Ferrier and Grimm2001); however, it can simultaneously be a role model and a reference for imitation (Giachetti & Lampel, Reference Giachetti and Lampel2010; Verbeke & Tung, Reference Verbeke and Tung2012) because it is perceived as using best practices. That is, if an industry leader initiates a specific action as an early mover, other firms within the industry would be expected to respond, not only because the action is that of a rival, but also because it is the action of a successful or exemplary player to benchmark or follow (Haveman, Reference Haveman1993; Verbeke & Tung, Reference Verbeke and Tung2012). An industry leader's behavior is expected to exert dual pressure as the action of the biggest rival and a socially legitimate, successful reference. Therefore, to additionally focus on purely rivalry-driven factors, the actions of the industry leader need to be viewed separately from those of other competitors in the same industry. Previous researchers have also noted that a leader firm's actions are perceived to be more serious than those of other firms (Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer, & Welch, Reference Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer and Welch1998; Elnathan & Kim, Reference Elnathan and Kim1995; Giachetti & Lampel, Reference Giachetti and Lampel2010; Ito, Reference Ito1997).

However, if the action is undertaken by non-leader competitors that are not necessarily considered prominent or successful, the reaction by the focal company can be explained as being rooted in more purely competitive rivalry (Figure 1). The behavior of non-leader competitors is still likely to motivate firms within the same industry to respond in an attempt to compete against rivals and to match their actions, even though their actions are not always considered to be best practices. The preceding discussion suggests further refinement of the industry competitor variable for additional analysis of Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1b. Earlier adoption of CSR by non-leader competitors in the same industry is related to early adoption by the focal firm.

Mimetic pressure: non-competitors' behavior

Firms may follow or imitate other firms' behavior, even without competitive consideration, if the other firms are perceived to have exemplary good performance. That is, firms sometimes aim to behave in a manner that conforms to the various rules and norms of the social and institutional environment (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Haveman, Reference Haveman1993). Institutional theory explains the relationship between an organization and its environment (Meyer & Rowan, Reference Meyer and Rowan1977). To deal with uncertainty in a given environment, firms observe and follow the previous actions of other firms as a way to minimize risk (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Haveman, Reference Haveman1993).

This corporate effort to adapt to the social and institutional environment through mimetic behavior shows that firms face various types of social and institutional pressure (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983). Accordingly, as a business organization in a society, a firm may be willing to increase its resemblance to other firms in the same context (Haveman, Reference Haveman1993) and may seek to do so for reasons that go beyond attaining a competitive advantage. Previous literature on imitative business behavior has examined various topics and phenomena across different industries (Lieberman & Asaba, Reference Lieberman and Asaba2006), including imitation of acquisition activities (Haunschild, Reference Haunschild1993), online market entry (Bhatnagar, Nikolaeva, & Ghose, Reference Bhatnagar, Nikolaeva and Ghose2016), product technology (Giachetti & Lanzolla, Reference Giachetti and Lanzolla2016), the adoption of new formats by radio stations (Greve, Reference Greve1995), and the adoption and implementation of total quality management (Westphal, Gulati, & Shortell, Reference Westphal, Gulati and Shortell1997).

In earlier studies, institutional framework was applied in an effort to understand and explain CSR as a means of attaining social legitimacy (Campbell, Reference Campbell2007; Husted & Allen, Reference Husted and Allen2006; Ozdora-Aksak & Atakan-Duman, Reference Ozdora-Aksak and Atakan-Duman2016; Yang & Rivers, Reference Yang and Rivers2009). That is, CSR adoption or implementation by a company can also be understood as a response to pressures created by other firms' CSR practices. If CSR adoption by other firms is frequently observed in a society, firms are likely to behave in a similar way to gain social legitimacy. Firms' CSR adoption decisions can proceed from their mimetic isomorphism, even without coercive or normative pressure, which thereby promotes CSR diffusion within the larger business community.

In addition, by observing non-competing firms' CSR behaviors in other industries (Figure 1), firms can learn that this new management approach is readily acceptable or applicable to their own corporations. The potential adopters can therefore make a more informed decision to change their corporate behavior to adopt CSR. The early adopters' behavior thus serves to assure other potential adopters about the compatibility of CSR, reducing the risk of uncertainty.

Hypothesis 2a. More adoption of CSR reporting by non-competitors in all prior years is cumulatively associated with quicker diffusion of CSR adoption among firms.

Meanwhile, this isomorphism can proceed and be enhanced in the presence of ongoing recent social fads (Bikhchandani et al., Reference Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer and Welch1998). By observing how other firms recently change their corporate decisions and behaviors without considering sufficient evidence, firms would be more likely to imitate the newly accepted business practices of others.

Hypothesis 2b. More adoption of CSR reporting by non-competitors in the immediate prior year is associated with quicker diffusion of CSR adoption among firms.

Methodology and data

The main research task of this study is to examine the potential determinants of whether or not a company adopts CSR, leading to CSR diffusion across companies in a country, and if CSR is adopted, how many years elapse before that occurs. To incorporate the time-to-adoption factor, this study employs event history analysis methods using a discrete-time logistic regression model (Allison, Reference Allison1982). This approach accounts for the longitudinal relationship between the potential determinants and the diffusion of CSR adoption, incorporating the dynamics of the change in firms' behavior due to CSR adoption. This research therefore explores the factors that are associated with earlier CSR adoption for each company and thus lead to eventual diffusion across firms within the same country context.

In addition, firms are nested within particular industries that are characterized according to products and services. To account for the potential lack of independence in the error structure resulting from the nested nature of the firm-level data, this study also uses a hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) approach, which includes industry effects based on the 110 different industry groups classified by the KRX (Korea Exchange) industry code, to estimate the models. The multilevel and multiple effects random-parameter HLM models are estimated using a maximum simulated likelihood approach (Greene, Reference Greene2007).

Empirical study on the potential determinants of earlier voluntary CSR adoption leading to diffusion across firms includes two main explanatory variables and seven control variables: industry competitors' behavior, non-competitors' behavior, industry leadership status, firm size, firm profitability, firm age, average years working for a company, international listing, and industry's environmental and social sensitivity. Except for the industry-level control variable, all independent variables and firm-level control variables in our models are time-varying variables observed annually. Throughout the analysis, a 1-year time lag between the independent variables and the CSR adoption (dependent variable) is assumed unless otherwise noted. For instance, a firm's CSR adoption decision in 2012 may be affected by CSR behavior of its competitors and non-competitors in 2011.

In addition to the firm characteristics, for firms that belong to environmentally and socially sensitive industries, the potential effect of the industry sensitivity on firms' CSR needs to be considered (Reverte, Reference Reverte2009). Thus, a separate set of discrete-time logistic regression models with a control variable of industry sensitivity are estimated.

Data and sample

Our data consist of a sample of 711 Korean publicly traded firms, including 90 firms with CSR reporting experience and 621 firms with no reporting experience. A total of 7,085 firm-year observations corresponding to the sample firms are available for the observation period of 2003 to 2014. As a country without a mandatory CSR implementation or reporting requirement, Korea provides an opportunity to focus on the determinants of a firm's voluntary adoption, eliminating alternative explanations relating to the direct influence of governmental requirements.

The longitudinal data were collected from multiple archival sources: (a) corporate annual reports, (b) the DART (Data Analysis, Retrieval, and Transfer system provided by Financial Supervisory Service in Korea; http://englishdart.fss.or.kr), (c) the Mergent online database (http://www.mergentonline.com), (d) company websites, (e) stand-alone CSR reports, (f) the Global IPO guide by Samil PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC; http://www.pwc.com/kr/en), and (g) press releases. All publicly traded companies in Korea are required to disclose their financial information in accordance with Korean laws or regulations.

Annual reports of sample companies were used as the main source of firm-level data. The DART, an official repository of Korea's corporate filings, provided the list of companies in the stock market, basic corporate information, and companies' electronically disclosed filings, including annual and audit reports, financial statements, and so forth. In addition, the Mergent online database was used to supplement historical data. In terms of the international listing data, the information was initially collected from the Global IPO guide by Samil PwC and later cross-checked with annual reports. The guide provides a list of Korean companies on major foreign stock exchanges, such as New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), London Stock Exchange (LSE), Japan Exchange Group (JPX), Singapore Stock Exchange (SGX), and so forth, between 1994 and 2014. As of 2015, Chinese stock exchanges had not yet allowed foreign companies to list shares on their stock markets.

For the CSR reporting information, most reporting firms publicize and post their annual stand-alone CSR reports on the company website. Information on whether a company has ever reported, and, if so, when reporting began, was initially collected from each company's official website or from media sources and was cross-checked with CSR reports. Regarding the format of CSR information disclosure, no standardized requirement exists. Whether or not the CSR reporting follows the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the most widely used reporting guidelines, is thus not included in our analysis. According to the KPMG survey (2013), however, 78% of global firms apply this universal GRI framework. In terms of the firms in the sample, more than 85% of reporting firms in Korea voluntarily referred to the GRI guidelines in their initial CSR reports.

The original sample included 742 companies listed in the KOSPI (Korea Composite Stock Price Index) market as of 2014. Our final sample of 711 unique companies includes 90 companies (12%) that had initiated CSR performance reporting at any point before the end of 2014, as well as firms that had not yet initiated CSR performance reporting by then. The majority of the final sample thus consists of firms that did not initiate CSR adoption. The sample includes companies from 110 industries including both the manufacturing and service industrial sectors: Food & Beverages, Textile & Apparel, Paper & Wood, Chemicals, Metal, Machinery, Distribution (Wholesale & Retail), Electricity & Gas, Construction, Transportation, Communication, Finance, and so forth. In our sample, 95 out of 110 industries have no more than 12 listed companies each.

The period of observation for this study was from 2003, when three companies in Korea published their first CSR report, to 2014. Since the observation period starts with the first year of CSR reporting in Korea, there is no left-censoring issue in this study. For the 90 companies adopting CSR, our observations continue until the point of adoption; for the remaining companies, they continue until the end of the study period. The observations for remaining companies are treated as right-censored observations in our data. Information regarding either the cessation of reporting or the cycle of reporting was not considered in this study.Footnote 1

Variables

Dependent variable

The dependent variable is the initiation of CSR reporting during the observation period, which captures the CSR adoption by a company, and if CSR was initiated, how many years elapsed between the pioneering firms' initial reports and when the focal company began reporting. It was measured from the initiation of CSR reporting and recorded categorically as either 0 or 1, for non-reporting years or for the reporting year, respectively. In Korea, the first year of CSR reporting was 2003 by Hanwha Chemical, Hyundai Motor Company, and Samsung SDI. Therefore, in 2003, among the sample companies, only those three firms have a value of 1 for their dependent variable, while all other firms have a value of 0. During the observation period, each of the 90 companies with CSR-reporting experience in the sample have a single 1, corresponding to the commencement of CSR reporting. Firms without any CSR reporting experience, on the other hand, have only values of 0.

Consistent with the definition of CSR in this study, we judge whether a firm is voluntarily involved in the CSR effort of communicating its commitment to responsible business to its stakeholders by observing its voluntary CSR reporting. This measurement is appropriate because it is readily measurable and comparable across companies. More importantly, the CSR behavior included in this study should also be identifiable and noticeable by competitors or other companies in the market since we are exploring those main external forces.

In previous studies, frequently used proxies for CSR include CSR ratings or scores provided by third-party agencies (Attig, Boubakri, El Ghoul, & Guedhami, Reference Attig, Boubakri, El Ghoul and Guedhami2016), such as MSCI ESG data, previously known as the KLD database (Kinder, Lydenberg and Domini Research and Analytics, Inc.), for firms listed in the United States (Attig, El Ghoul, Guedhami, & Suh, Reference Attig, El Ghoul, Guedhami and Suh2013; Barnea & Rubin, Reference Barnea and Rubin2010; Siegel & Vitaliano, Reference Siegel and Vitaliano2007); the reputation index (e.g., Fortune rating) (Cochran & Wood, Reference Cochran and Wood1984; Luo & Bhattacharya, Reference Luo and Bhattacharya2006); CSR spending or charitable expenditure (Fombrun & Shanley, Reference Fombrun and Shanley1990; Lev, Petrovits, & Radhakrishnan, Reference Lev, Petrovits and Radhakrishnan2010); and CSR initiative membership or CSR reporting or nonfinancial information disclosure (Abbott & Monsen, Reference Abbott and Monsen1979; Anderson & Frankle, Reference Anderson and Frankle1980; Cho, Lee, & Park, Reference Cho, Lee and Park2012).

However, using secondary data such as CSR ratings offered by third-party agencies, which represent one of the popular measurements of CSR in prior studies, cannot eliminate the potential for arbitrary judgment or subjective interpretation. Further, measuring CSR adoption based on a firm's launch of a CSR program does not allow for comparisons because the format, contents, range, and focus of CSR programs can vary across firms and industries. It may also be even harder to pinpoint CSR initiation unless the information is officially disclosed.

Independent variables

Industry competitors' behavior: This study measures the number of competitors in the same industry (Competitors) that adopted CSR in previous years. Based on the industry categories assigned by the Korean stock exchanges, all companies in our sample were assigned a six-digit industry code. Companies with the same industry code were considered competitors in the same industry (Figure 1). The sample firms were classified into 110 different industry groups based on the KRX industry code. Within the same industry group, the number of reporting firms increased from 0 in 2003 and grew each year in which CSR-reporting firms appeared in the same industry.

Among the industry competitors, an industry leader may exert dual effects associated with (1) its sheer size as a major competitor whose actions affect the economic performance of smaller rivals and (2) its socially legitimate status (Han, Reference Han2018). The industry leader's behaviors may be regarded as socially legitimate (in addition to the competitive rivalry consideration), while a non-leader's actions may not be considered socially legitimate by other rivals because of the non-leader's lower social status within their peer industry group. This potential concern leads to further refinement of the industry competitor variable and to additional examination for the effect of pure rivalry.

In this study, an industry leader is defined as a firm with the largest sales volume within an industry in a given year. Thus, the CSR adoption behavior of a leader firm and that of non-leader rival firms within the same industry were measured separately. The Leader variable is assigned a value of 1 if it adopted CSR previously, and 0 otherwise. The remaining competitors are regarded as non-leader rivals (see Figure 1); the Non-leader rivals variable was measured by the cumulative number of the non-leader competitors that adopted CSR each year. Incorporation of both variables allows isolation of the purely competitive pressure by non-leader competitors and a focus on how it plays a role, controlling for the potential dual effect of the industry leader's behavior (Han, Reference Han2018). Among the 110 industry leaders in our sample, 22 industry leaders were CSR adopters.

Mimetic behavior: Two different measurements of mimetic behavior were used. First, to discern the potential influence of mimetic behavior, the cumulative number of CSR adoptions for all firms outside the industry (Mimetic All) was observed and measured. Non-competitors have industry codes that differ from the focal company's code. The number of CSR-reporting firms among the non-competing firms was counted each year cumulatively going forward from 2003. Second, to identify mimetic behavior related to the more recent action or ‘social fads’ in firms' CSR adoption behavior, the total number of newly reporting firms in a prior year among non-competing firm groups (Mimetic Prior) was separately observed and collected for the second measurement.

Control variables

A set of firm-level and industry-level control variables that might be related to firms' CSR behavior were considered in our empirical models.

Firm size: We controlled for the effect of a firm's size. The literature reveals that most, though not all, previous empirical studies have documented a positive association between firm size and CSR (Reverte, Reference Reverte2009; Udayasankar, Reference Udayasankar2008). Since our sample consisted of many different types of industries, including the manufacturing and service sectors, the number of employees in the prior year was selected as the measurement for each firm's size. Logarithmic transformation was used to provide the model with stability.

Firm profitability: Prior literature reveals inconsistent results, with many types of relationships possibly existing between CSR and profitability of the firm, such as positive or negative, insignificant, U-shaped or inverted U-shaped, and asymmetric (Grewatsch & Kleindienst, Reference Grewatsch and Kleindienst2017). Thus, we controlled for firm profitability. Return on assets in the prior year was used as a proxy for profitability.

Firm age: Firm age was included as another control variable. Previous studies have provided inconclusive evidence (Badulescu, Badulescu, Saveanu, & Hatos, Reference Badulescu, Badulescu, Saveanu and Hatos2018), with both positive and negative relationships being reported between corporate age and various CSR behaviors (e.g., Cano-Rodríguez, Márquez-Illescas, & Núñez-Níckel, Reference Cano-Rodríguez, Márquez-Illescas and Núñez-Níckel2017; Salehi, Tarighi, & Rezanezhad, Reference Salehi, Tarighi and Rezanezhad2019). Each firm's age was defined as years of operation since its establishment and measured by ‘the year of observation minus the year of establishment,’ which is standardized for estimation and interpretation.

Average years working for a company: A positive association between CSR and a firm's employee management has been demonstrated in many empirical studies (Albinger & Freeman, Reference Albinger and Freeman2000; Backhaus, Stone, & Heiner, Reference Backhaus, Stone and Heiner2002; Peterson, Reference Peterson2004; Turban & Greening, Reference Turban and Greening1997). Branco and Rodrigues (Reference Branco and Rodrigues2008) showed that CSR can reduce staff turnover and save on costs for recruitment and training. Thus, employee tenure – employees' average years working for a company – was controlled in the study. Each firm reported employee-related information, including employees' average years working for a company, which shows how long employees stay at a company on average. The average period may differ by industry, gender composition, or job function; however, such differences were not considered in this study. The Working years variable was standardized for the model stability.

International listing: We controlled for international listing effect because cross-listed firms, as foreign firms in the stock market, are required not only to observe and implement the mandatory regulations in foreign regulatory environments, but also to make serious efforts to be better recognized in the market beyond the stakeholders' expectations due to an increase in corporate visibility (Cooke, Reference Cooke1989; Saudagaran, Reference Saudagaran1988; Shi, Magnan, & Kim, Reference Shi, Magnan and Kim2012). These factors can facilitate voluntary disclosure of financial and nonfinancial information by firms (Cooke, Reference Cooke1989; Meek & Gray, Reference Meek and Gray1989) as a way to demonstrate responsible performance (Cooke, Reference Cooke1989). This variable was measured based on whether or not a focal firm was listed on foreign stock markets each year during the observation period. We thus assigned the value of 1 if a firm was listed on one or more of the foreign stock exchanges and 0 if it was not listed on any of the foreign stock markets. During the observation period, 16 out of a total of 711 sample companies had ever been listed on the international stock exchanges; none of them were delisted in the middle of the study period.

Environmental and social sensitivity of the industry: In order to consider industry-specific characteristics that might affect a firm's CSR adoption behavior (Chiu & Wang, Reference Chiu and Wang2015), this study included an industry-level control variable. According to past research, some industries are more environmentally and socially sensitive: mining, oil and gas, chemicals, pulp and paper, steel and other metals, electricity, alcohol and tobacco, and transportation and utilities (Adnan, van Staden, & Hay, Reference Adnan, van Staden and Hay2010; Chiu & Wang, Reference Chiu and Wang2015; Liu & Anbumozhi, Reference Liu and Anbumozhi2009; Reverte, Reference Reverte2009). Firms operating in these industries tend to be more involved in various CSR practices, including CSR information disclosure (Aerts, Cormier, & Magnan, Reference Aerts, Cormier and Magnan2008; Liu & Anbumozhi, Reference Liu and Anbumozhi2009; Reverte, Reference Reverte2009). Thus, this research controlled for the industry effect of environmental and social sensitivity. Firms belonging to environmentally and socially sensitive industries were assigned a value of 1, and rest of the firms were all assigned 0 for analysis.

Procedure

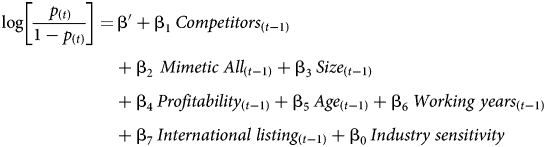

The empirical analysis is intended to estimate a discrete-time logistic regression model, specifying how the CSR adoption decision may depend on the two explanatory variables. Since the research question focuses on how likely it is that the earlier CSR adoption decision is made, this method is useful in terms of capturing every firm-year observation until CSR is adopted by each company during the observation period. In particular, in the event history analysis, the hazard rate should be considered a key concept for model development (Allison, Reference Allison1984). This rate is defined as the probability of the occurrence of an event at a given point of time. In this study, hazard rate, p (t), refers to the probability of making a CSR adoption decision within a particular year for firms that have not previously adopted CSR.

The model is assumed to follow a logit function:

where t indicates the year of observation, β' refers to the intercept, and β1…k indicates the coefficients for each explanatory variable for each year of observation. The odds ratio is calculated for easier interpretation by exponentiating the coefficients. With regard to the coefficients β1…k for the time-varying explanatory variables, each provides the information on the change in log-odds for one-unit change in each of the independent variables. The coefficient β0 is for a time-constant explanatory variable, which does not change over time. The industry-level control variable is the only time-constant variable in the study, and it can be added at the end if needed. Thus, the full model for testing the hypotheses is as follows:

In addition, the Competitors variable is replaced with the Non-leader variable when controlling for the Leader variable. Moreover, to analyze the effect of social fads, the Mimetic Prior variable is included instead of the Mimetic All variable.

Results

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics of the sample data and correlation matrix among the variables. Because of a concern about high multicollinearity, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated. The highest VIF in the model with main independent predictors was less than 10, the threshold value suggested by Neter, Wasserman, and Kutner (Reference Neter, Wasserman and Kutner1985), indicating that multicollinearity is not a significant concern in the study. Also, due to the same concern between Mimetic All and Mimetic Prior – two different measurements of institutional mimetic pressure due to non-competitors outside the industry – the variables are separately modeled in the analyses.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations

Note: 3 = Firm size (log), 5 = Firm age (standardized), 6 = Working years (standardized).

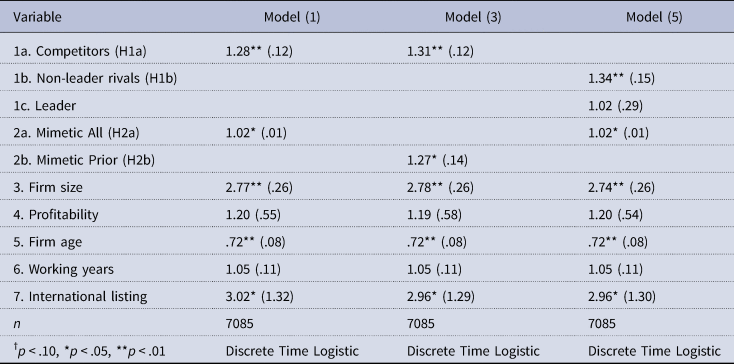

In Table 2, Models (1), (3), and (5) report the results of discrete-time logistic regression, and Models (2), (4), and (6) show the results of random parameter HLM discrete-time logistic regressions, which incorporate 110 different industry effects, respectively. The results of the two methods are very similar. The coefficients associated with Competitors are positive and significant (p < .01) in Models (1)–(4), thereby lending support to Hypothesis 1a. That is, each firm's adoption of CSR, which can lead to diffusion of CSR, is accelerated by its industry competitors' CSR adoption. In particular, the coefficients of Models (1) and (3) indicate that, for a one-unit increase in Competitors in each model, an increase of 1.28 and 1.31 in the odds of CSR adoption is expected, respectively, holding all other predictors constant. Therefore, with each additional CSR adoption behavior among a focal firm's competitors, the odds of CSR adoption by the focal firm increase by 28% and 31%. The Appendix includes the results of odds ratio for all explanatory variables. Furthermore, after controlling for the presence of the industry leader's CSR and for possible mimetic isomorphism, additional examination with non-leader competitors' CSR adoption behavior in Models (5) and (6) presents consistent results, suggesting that the firm's socially responsible behavior may also be motivated by purely competitive rivalry. Exponentiating the log odds coefficient yields a 1.34 increase in the odds of CSR adoption (Appendix). That is, CSR adoption by non-leader competitors has a strong positive effect, increasing the odds of a focal firm's CSR adoption by 34%.

Table 2. Discrete-time logistic regression analysis (1) (standard errors in parentheses)

The coefficients associated with Mimetic All in Models (1) and (2) and Mimetic Prior in Models (3) and (4) are also positive and significant at p < .05. These results support Hypothesis 2a, which holds that mimetic behavior associated with earlier adoption by non-competitors is related to quicker adoption by the firms. Mimetic isomorphism resulting from non-competitor's CSR, however, increases the odds of CSR adoption by only 2%. Also, the test result of Mimetic Prior suggests that a focal firm's CSR adoption decision is likely to be prompted by a more recent social fad given by the prior year's CSR behaviors by non-competitors. With each additional CSR adoption behavior among a group of non-competitors in a prior year, a 27% increase in the odds of a focal firm's CSR adoption is expected (Model (3) in Appendix).

Among the control variables related to firm characteristics, the coefficient associated with the size of the firm is positive and significant (p < .01) in all models. The larger firms listed in Korea tend to adopt CSR earlier than smaller firms. The coefficients associated with a firm's profitability, however, are not statistically significant (p > .10) in all models. Contrary to the assumption, the coefficients associated with the firm age variable are negative and significant (p < .01). The results suggest that younger firms with relatively shorter corporate histories are more likely to adopt CSR than are older firms with longer histories, thereby leading to quicker diffusion across firms. The coefficients associated with employee tenure are not statistically significant (p > .10). The results from the models indicate that international listing is positively related to earlier adoption of CSR.

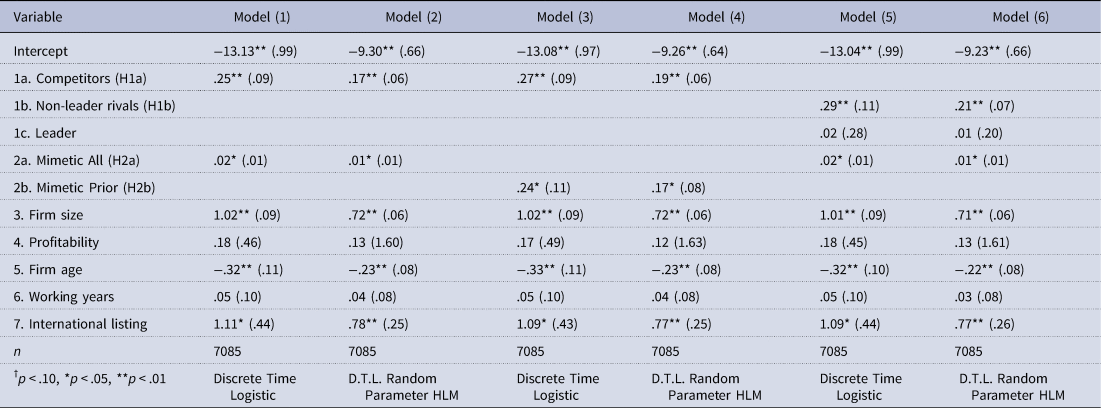

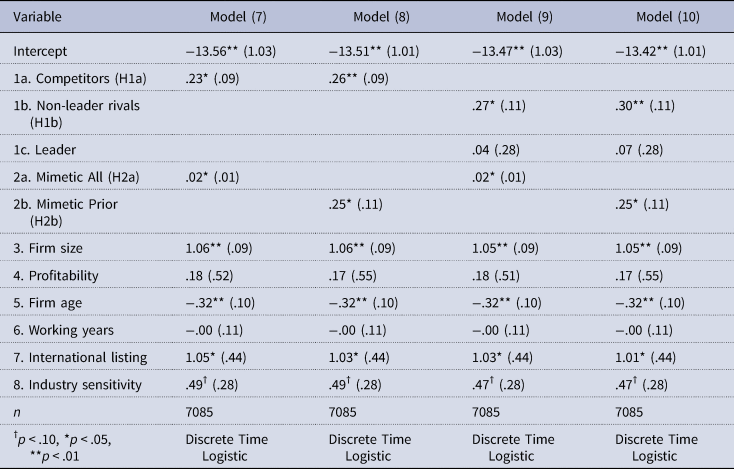

Table 3 reports the results of regressing the explanatory variables on earlier CSR adoption, including the industry-level control variable. When we control for environmental and social sensitivity of industry, the analysis results remain mostly the same. Industry sensitivity itself is found to be positively associated with a firm's earlier CSR adoption and moderately significant (p < .10).

Table 3. Discrete-time logistic regression analysis (2) with an industry-level control variable (standard errors in parentheses)

Competitive pressure from rivals is a significant variable throughout the set of models, at least at the 5% level. In terms of purely rivalry-driven competitive pressure, the results strongly support Hypothesis 1b, showing positive and significant correlation with earlier CSR adoption.

The estimated coefficients for institutional pressures from non-competitors (Mimetic All) are also positive and significant (p < .05) in Models (7) and (9), controlling for the industry sensitivity and firm characteristics. These findings support Hypothesis 2a, which assumes a positive association with earlier adoption of CSR. In Models (8) and (10), the influence of recent social fads, non-competitors' CSR behavior in the prior year, is additionally found to be significantly related to a focal company's earlier CSR adoption, leading to quicker diffusion. Thus, the results lend support for Hypothesis 2b.

Discussion and conclusions

This study proposes that both competitive pressure and institutional mimetic pressure play a role in the spread of CSR adoption practice. To test the hypotheses, we empirically examined CSR adoption behaviors of Korean publicly traded companies between 2003 and 2014, using the first disclosure of CSR performance as a proxy. By focusing on the analysis of individual companies' decision of whether to officially disclose their CSR-related information and incorporating time-to-adoption factor, we investigated the diffusion of voluntary CSR adoption among companies.

Consistent with expectations, our findings suggest that firms' earlier CSR adoption is positively associated with the behavior of rival firms in the same industry. The results indicate that competitors' adoption of CSR, as a competitive pressure, may induce other firms to initiate adoption themselves, which eventually speeds the diffusion of the practice. We further found that purely competitive rivalry also leads firms to exhibit socially responsible behavior, as shown by the positive coefficient of non-leader rivals, controlling for industry leader's potential dual influence as a role model. This finding supports and extends previous research concerning oligopolistic reaction (e.g., Knickerbocker, Reference Knickerbocker1973). That is, a firm's CSR adoption decision can also be understood and explained as a competitive reaction to its rivals' behavior, as found in previous studies that primarily focused on oligopolistic reaction to foreign direct investment decisions. In addition to competitive pressure, institutional pressure prompted by institutional mimetic isomorphism appears to have a positive relationship with earlier CSR adoption, thereby leading to quicker diffusion of CSR within a country. The more CSR adoption of firms outside the industry is frequently observed in a society, the more a focal firm imitates the behavior in an effort to gain social legitimacy. This finding indicates that social pressure is an important factor in the adoption and diffusion of CSR across firms within the same country context, which is consistent with the institutional theory (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Haveman, Reference Haveman1993). In other words, firms are still likely to imitate ‘doing something good’ behavior of other firms in the market in addition to other types of organizational behaviors or practices (Lieberman & Asaba, Reference Lieberman and Asaba2006). Interestingly, in terms of social fads, which are exerted by recent behavioral changes of non-rival companies, their influence was shown to be strongly associated with quicker diffusion of CSR adoption behavior. The results imply that firms tend to be attentive and vigilant to responding to the newly adopted practices of other firms.

This study is not without limitations. For the purpose of this study, we needed an observable and comparable CSR indicator, and we chose to use the adoption of CSR reporting; thus, the level or range of CSR activities are not considered. The CSR behavior used for this study also had to be identifiable and noticeable by competitors or other companies in the market, since we are exploring those main external forces. If the quality of CSR practices or the range of CSR activities becomes publicly available, this is a fruitful direction in the future, since there are some concerns related to no (or less) significant correlations between CSR disclosure (quality) and actual CSR performance (Michelon, Pilonato, & Ricceri, Reference Michelon, Pilonato and Ricceri2015; Nazari, Hrazdil, & Mahmoudian, Reference Nazari, Hrazdil and Mahmoudian2017).

Contributions

This research extends the competitive reaction and oligopolistic reaction literature by analyzing CSR adoption and diffusion as a matching reaction to the CSR behavior of competitors in the same industry. In our analysis, using the observed industry competitors' previous CSR behavior up to the prior year, we applied the ‘competitive action-reaction’ and ‘competitive move-countermove’ explanations based on previous oligopolistic reaction literature to elucidate the firms' CSR adoption decision. By considering competitive pressure exerted by direct rivals as a separate pressure, we reveal that firms are likely to make a strategic decision based on rivals' previous behaviors even when they are adopting a social behavior.

Moreover, some prior literature suggests that competitive pressure may not always lead to followers' imitative behaviors (Rose & Ito, Reference Rose and Ito2008). However, for CSR adoption behaviors, we find that firms are willing to be responsive to their rivals' prior behaviors along with institutional pressures. This finding implies that whether firms follow certain behaviors of their rivals depends not only on the existence of competitive pressures but also on the types of behaviors.

Another theoretical contribution is related to purely rivalry-driven competitive pressure. By separating out the potential mimetic isomorphism factor, which may be part of the dual effect of an industry leader, from the same industry competitors' pressure, we identified and examined the purely rivalry-driven competitive pressure from non-leader competitors. Thus, the explanation from the competitive reaction perspective is further supported with the analysis of the role of the non-leader rival's CSR as a purely rivalry-driven factor in a firm's earlier adoption of CSR, which can lead to the diffusion of CSR across firms.

Lastly, most of the previous CSR studies so far have mainly explained the phenomenon from an institutional perspective, focusing on its efforts to gain social legitimacy. This research enhances our understanding on the diffusion of voluntary CSR adoption behavior by incorporating and examining potential determinants of CSR adoption and diffusion from multiple perspectives, both competitive pressure and institutional mimetic pressure simultaneously.

Appendix

Results of discrete-time logistic regression models in odds ratios (standard errors in parentheses)