INTRODUCTION

The wave of decentralisation reforms that began sweeping through Africa in the 1990s has led to a multiplication of decentralised units in several countries (Grossman & Lewis Reference Grossman and Lewis2014: 199; Hassan & Sheely Reference Hassan and Sheely2017: 1597). Scholars have studied the extent to which such proliferation has provided rulers with expanded patronage opportunities (Kraxberger Reference Kraxberger2004; Green Reference Green2010; Hassan & Sheely Reference Hassan and Sheely2017); prevented defection by local elites by giving them greater vested interest in the state (Grossman & Lewis Reference Grossman and Lewis2014); and at times undermined opponents when partitioning their constituency (Kraxberger Reference Kraxberger2004). Yet, there has so far not been any study of the extent to which the multiplication and relocation of structures of governance implied by decentralisation has affected the nature of ethnic representation in the state and, thereby, its legitimacy. To be sure, some authors have noted that the multiplication of decentralised entities has led to more ethnically homogeneous units in countries such as Uganda (Green Reference Green2008), Nigeria (Kraxberger Reference Kraxberger2004) and Indonesia (Kimura Reference Kimura2013). But nobody has yet investigated how such outcomes stand to reshape the functioning of multiethnic societies and, particularly, practices of balanced ethnic representation in the state that constitute the foundations of many African states (Young Reference Young1976; Rothchild & Chazan 1988; Rothchild Reference Rothchild1997; Neuberger Reference Neuberger and Chazan1999), thereby raising issues of state ownership.

In this paper, we present the first attempt to investigate empirically the effects of decentralisation policies on collective ethnic representation in Africa. Focusing on the experience of the Democratic Republic of Congo, which decentralised in 2006 and increased the number of provinces from 11 to 26 in 2015, we provide the first systematic documentation of the effects of the multiplication of provinces on their ethnic homogenisation, and analyse the effects of this transformation on practices of ethnic representativeness, a constitutional provision according to which the personnel of Congolese governing institutions and agencies must reflect the distribution of regions or ethnic groups within their area of jurisdiction. We find that the ethnic homogenisation of provinces has led to the ethnic takeover of provincial governments by dominant groups, leading at times to complete monopolies. While such takeovers might have beneficial effects in terms of collective action, they have also increased the proportion of groups and individuals who do not have collective representation in the state. Moreover, the necessity to apportion limited public employment opportunities at the provincial level according to ethnic representativeness has fostered, in places, the spread of autochthonous discourses and policies, which are excluding non-originaire provincial residents from the benefits of resource distribution, leading to a two-tier citizenship system that risks alienating and disenfranchising large segments of society.

CONCEPTS AND THEORIES

We use several concepts – ethnicity, autochthony, representativeness and decentralisation – that call for some clarification, at the onset, in the usage we make of them, their relevance to Congolese politics, and the theoretical approaches we follow. We take them in turn in this section.

Ethnicity

While Africanist scholarship generally sees ethnicity in constructive terms, as an identity whose political salience is a function of other variables,Footnote 1 many Congolese in contrast experience it in primordial ways, with a strong connection to land and presumed ancestry. This outlook seems to derive from Belgian colonial policies. A decree of 1910 imposed that all Congolese be identified with respect to a single ethnically defined chiefdom,Footnote 2 with the result that each had a territory and identity ‘of origin’. The purpose of this policy was partly to control population movements and to break up large kingdoms that covered multiple chiefdoms so as to better dominate them. Yet, it ended up establishing a ‘nexus … which has been constitutive for the Congo's political order’, characterised by ‘ethno-territorial imaginary’. To this day, voter cards – the only widespread identity document – still indicate one's sector/chiefdom/commune, territory/city and province ‘of origin’, separately from one's birth place. One need not be born in one's chiefdom of origin, but it is the place where one's ancestors, or last known ascendants, are deemed to come from, or, practically, where one's ethnic group is from. As a result, to borrow Vlassenroot's (Reference Vlassenroot2013: 10) words, ethnic identity, tethered to geography, has become ‘a directing principle of the social, political and administrative organization’ of Congo. The Congolese constitution, in turn, enshrines this ethnicity inside citizenship and colonialism into ethnicity, declaring in its Article 10 that ‘Is Congolese of origin, every person belonging to ethnic groups whose persons and territory constituted what became Congo … at independence’.

Congolese ethnic agency is often expressed through the work of ethno-cultural associations known as ‘mutuelles’ (Gobbers Reference Gobbers2016). One of the main purposes of these associations is to sponsor their members’ access to political office and then hold them accountable for patronage-based redistribution to their ethnic kin, as well as to provide welfare and support to their members. In Lubumbashi alone, there are more than a dozen mutuelles, such as Bulama-i-Bukata (for the Lubakat ethnic group), Sempya (Lemba) or Lwanzo (Sanga).

The primordial view of ethnicity that is prevalent in Congo tends to prefer the word ‘tribe’ over the more universally accepted notion of ethnic group. Although tribes are anthropologically different from ethnic groups in Western scholarship and its usage encounters occasional resistance, the term ‘tribe’ has been appropriated by the Congolese to refer to ethnic identities (although some Congolese legal texts waver between tribe and ethnicity). Since we study Congolese praxis in this paper, we use ‘tribe’ and ‘ethnic group’ indifferently. We also engage in the exercise of imputing every individual to a specific tribe in order to study the effects of decentralisation on ethnic representation. We recognise that ethnicity is flexible, dynamic, imagined and constructed. Yet, in order to study the mechanics of Congolese politics, particularly the notion of collective representation (to which we return below), we follow, as a matter of methodology, the more rigid view that prevails among the Congolese.

Autochthony

The connection established by the Congolese between ethnicity and land has led to the rise of autochthony discourses and practices, particularly in regions of significant internal immigration, such as the Kivu provinces,Footnote 3 Haut-KatangaFootnote 4 and Kongo-Central.Footnote 5 Congolese autochthony is first defined at the level of the chiefdom, where being autochthonous means being a member of the ethnic group that names the territory (e.g. Territoire Wanyanga, Collectivité Bahundé, etc.), then at the provincial level, where autochthony means belonging to an ethnic group whose territories of origin (and chiefdoms) are located in the province (Jackson Reference Jackson2006: 100).

The Congolese often use the word ‘originaire’ for autochthonous. Although being ‘originaire’ of one province does not provide any differential rights and being ‘non-originaire’ does not legally make one vulnerable to discrimination, provincial originaire status has acquired significant practical relevance with the rise of autochthony discourses arguing that originaires are entitled to more rights than non-originaires in their territory or province of origin.

By transferring significant authority to provinces, the decentralisation reforms launched in 2008 (see below) have raised the political currency of provincial autochthony. ‘The cake must be shared’, an ethnic Sanga chief told us in Lualaba province (Customary Chief and Provincial Deputy, Kolwezi, Lualaba, 21.6.2017). But who is entitled to share it? While this is rarely a controversial question at the national level, those who claim a share at the provincial level are less clearly demarcated, a problem compounded by the more diminutive size of the provincial cake. Although she would have the same rights in law as originaires, a Mongo from Equateur would have weaker grounds for claiming access to public resources in South Kivu. Autochthony thus provides informal parameters for access to resources: ‘to each first dib over his/her region [of origin]’ (activist and copper alliance member, Kolwezi, Lualaba, 17.10.2017). In the eastern part of the country, it is often land access that is ‘framed in the language of autochthony’ (Mathys & Vlassenroot Reference Mathys and Vlassenroot2016: 5). In former Katanga, where demographic pressures are lesser and agriculture secondary to mining, it is more likely to be access to public employment and resources, or simply political participation. Citizenship becomes thereby informally defined on autochthony grounds, a phenomenon that already arose during the transition of the 1990s (De Villers Reference De Villers1998: 88).

In most provinces, particularly the more rural ones, a large proportion of residents can plausibly claim originaire status. But in other provinces, especially those with large cities or mining activities, a greater proportion of people are considered non-originaire or fall into ambiguous categories. Such ambiguity most often arises when one group is known as originaire of a province where its presence is large, while having a small number of chiefdoms or sectors in another province. In the latter, a restrictive and arguably dominant interpretation of origin would deem only those people from those specific sectors or chiefdoms to be originaire, unlike their ethnic kin in the other province. For example, only those Lubakat who are originaire from the territories of Kasenga and Mitwaba would be considered originaire of Haut-Katanga under this interpretation, leaving the vast majority of the Lubakat living in Haut-Katanga as non-originaires.

It is worth noting that autochthony is neither unique to the current phase of Congolese history nor to Congo. Casper Hoffman shows it is embedded in governing strategies of ‘ethnogovernmentality’ dating back to the colonial era when chiefdoms were designed as ‘mutually exclusive ethnically discrete territories’ (Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2019: 3). The multiplication of new provinces in the wake of independence between 1962 and 1964 followed an autochthony logic with originaire groups demanding their own provinces. Similarly, the autochthony discourse was unleashed in the Katanga province in the early 1990s against the Kasaian Baluba migrants (De Villers Reference De Villers1998: 82). It is also the dominant discourse in eastern Congo against the Banyamulenge community and among mai-mai groups (Jackson Reference Jackson2006). Outside Congo, several scholars have studied its prevalence across Africa. Dunn, for example, traces its origins in the ‘ontological uncertainty of the postmodern/postcolonial condition’ and associated it to a longing for a ‘sense of primal security’ (Dunn Reference Dunn2009: 114–15), both of which no doubt conform to the ongoing experiences of many Congolese.

Representativeness

According to the principle of representativeness (‘représentativité’), people can expect to have individuals from their province, territory or ethnic group selected to positions of public authority in approximate proportion to their demographic weight in the relevant political or administrative unit (country, province, cities …). Such collective representativeness is a norm that dates back to the early days of the Mobutu regime in 1965 when national governments began systematically incorporating members from all provinces (Kabamba Reference Kabamba, Omasambo and Bouvier2014). Young and Turner (Reference Young and Turner1985: 151) documented its practice in governments from 1965 to 1975. Aundu Matsanza (Reference Aundu Matsanza2010) shows that it also applied to the Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution (MPR) single party under Mobutu, to the Union pour la Démocratie et le Progrès Social (UDPS) opposition party and to the governments of the first transition period (1990–97).

While it developed as a ‘practical norm’ (De Herdt & Olivier de Sardan Reference Herdt, & J-P and Sardan2016), probably as a response to the civil strife and secession conflicts of the early 1960s, representativeness has become the law since 2006, when it was enshrined in Article 90 of the Constitution, which states ‘The composition of the government takes national representativeness into account’. Similarly, Article 23 of the 2008 law on decentralisation stipulates that ‘the composition of the provincial government takes provincial representativeness … into account’. The meaning of these articles is not further elaborated in these texts, but they are frequently invoked by the Congolese to refer to the necessity of regional and ethnic balancing in the formation of national and provincial governments, irrespective of political alliances.

A fundamental component of Congolese politics, representativeness partly confers legitimacy to a state known for its dysfunctions and predation, and allows ethnicity to co-exist meaningfully with it (Aundu Matsanza Reference Aundu Matsanza2010). It guarantees access to the state by a plurality of ethnic elites and constrains practices of patronage, as captured by the notion that ‘you can eat in peace when you share’ (activist and copper alliance member, Kolwezi, Lualaba, 17.10.2017). In doing so, it might diffuse the balkanising effects of ethnic heterogeneity by maintaining what Benjamin Neuberger refers to as the ‘plural softness’ of the African state, that is, its availability for universal consumption instead of monopolisation by a specific group (Neuberger Reference Neuberger and Chazan1999). In this respect, whereas Berman et al. (Reference Berman, Eyoh and Kymlicka2004: 5–7) claim that tribalism is ‘essentially amoral’ because the maximisation of tribal self-interest implies a disregard for its negative externalities, representativeness prevents any group from increasing its representation at the expense of the proper weight of others.

While representativeness has similar underpinnings to consociationalism (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1977), its implementation differs. Consociationalism is an institutionalised form of group-based power-sharing, with quasi-corporatist balancing mechanisms. Representativeness is fluid, practiced informally and often shadowy, and regulates the sharing of state resources more than state power. It appears more as a mechanism of legitimation than one of genuine participation. And, although it is recognised in law, it remains devoid of any specific mechanism of implementation.

At the national level, the units of representativeness tend to be regions, provinces or large umbrella ethnic identities, such as ‘Kasaian’ or ‘Mongo’, that include multiple component groups. At the provincial level, the relevant units are usually tribes or territories (the administrative subdivision below the province). Territories become more significant the more ethnically homogeneous a province is. In Haut-Lomami, for example, where about 80% of the population is Lubakat, balancing among provincial authorities explicitly refers to politicians’ origin in one of the five provincial territories: Bukama, Kabongo, Kamina, Kaniama and Malemba-Nkulu. Hoffmann observed a similar pattern among the Batembo of South Kivu (Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2019: 12).

The norm of representativeness is not unique to Congo. In Nigeria, the ‘federal character principle’ calls for balanced representation of the federation's states in the nation's institutions and alternation of the main regions in power (Osaghae Reference Osaghae1988). Looking at data from 15 Sub-Saharan countries between 1960 and 2004, François et al. (Reference François, Rainer and Trebbi2015) have shown that proportionality of representation of ethnic groups in government is widespread, contrary to perceptions of winner-take-all politics. They even find diminishing returns to the size of ethnic groups, indicating a particular concern for representation of smaller groups as the size of the larger one increases. And Azam (Reference Azam2001) refers to the modal political system in Africa as a ‘federation of ethnic groups’, which ensures the ethnic redistribution of state resources, thereby generating compliance with the ‘rules of the game’ and reducing the risk of violence from excluded elites.Footnote 6

Autochthony dovetails with the notion of representativeness as it limits the number of contenders for representation at the provincial or local level. Although not a formal legal concept, autochthony de facto defines who is entitled to representation in provincial politics, a trend that Mobutu encouraged in the latter years of his regime in order to undermine the Kasaians, who largely supported his opponent Etienne Tshisekedi, and who tended to be more widely distributed across the country than other identities (De Villers Reference De Villers1998: 93).

Decentralisation and découpage

Decentralisation refers to the transfer of political, administrative and fiscal responsibilities in certain policy areas from central government to subnational units. In Congo, the 2006 Constitution and the 2008 Decentralisation Law transfer responsibilities in the areas of education, health, agriculture and rural development exclusively to the provinces, and confers on them shared responsibility with the central government in other policy areas. Provinces have governors, cabinets and assemblies, their own budgets, and the capacity to raise provincial taxes. In 2015, a law on découpage (literally, ‘cutting up’ in French) increased the number of Congolese provinces from 11 to 26, through the partition of six of the previously existing ones. These were divided as follows:

• Bandundu: Mai-Ndombe, Kwango, Kwilu.

• Equateur: Equateur, Mongala, Nord-Ubangi, Sub-Ubangi and Tshuapa.

• Province Orientale: Bas-Uele, Haut-Uele, Ituri and Tshopo.

• Kasai Occidental: Kasai and Kasai Central.

• Kasai Oriental: Kasai-Oriental, Lomami and Sankuru.

• Katanga: Haut-Katanga, Haut-Lomami, Lualaba and Tanganyika.

In contrast, Bas-Congo (renamed Kongo Central), North and South Kivu, Maniema and Kinshasa were not further subdivided, leading to a total of 26 provinces nation-wide.Footnote 7

Both decentralisation and découpage have had the effect of increasing the relative value of provinces for individual and collective strategies of representation and access to resources, and of smaller administrative units like territories and chiefdoms which form the basis upon which local elites compete for access to provincial positions. As a result, just as democratisation led to a ‘hardening of ethnic divisions’ in the 1990s (Vlassenroot 2013: 10), decentralisation and découpage have raised the salience of ethnicity at the provincial level, one of the trends we focus on in this paper.

METHODS AND DATA

In order to assess the effects of decentralisation on ethnic representation, we identify the distribution of ethnic groups by province, before and after the provincial break-up of 2015, as well as the distribution of ethnicities among some provincial governments. We also code individuals as autochthonous or not to their province of residence.

Data on Congolese ethnicity is not easy to come by. Congo has not had a population census since 1984. Population estimates vary from about 70 to 100 million (Marivoet & de Herdt Reference Marivoet and De Herdt2017; Thontwa et al. Reference Thontwa, de Herdt, Marivoet and Ulimwengu2017) and there are no official estimates of the size of ethnic groups. Fortunately, we were able to deduce ethnic data from a 2012 nationwide household employment and consumption survey of about 110,000 respondents (Enquête 1-2-3), which contains a variable where respondents were asked to identify their ‘tribe’ as well as the territory in which they reside (INS 2012).Footnote 8 However, when asked about their tribe, some respondents mentioned large recognised entities such as Mongo, Luba and Binza. Others referred to sub-categories such as Ekonda (a Mongo subgroup), Bakwa Kalonji (Luba) or Mbudja (Binza). A few even listed their clan, village, chief, ancestry or even some specific geographic location. As a result, Enquête 1-2-3 produced 394 ‘ethnic groups’. This number, which exceeds even the generous estimate of 365 ethnic groups of Ndaywel è Nziem (Reference Ndaywel è Nziem1998: map 14 between pp. 256 and 257), results in part from a lack of organisational consistency as groups are not identified in relation to each other (e.g. x and y might be listed separately although x is a subset of y), respondents are allowed to choose the level of their answer (from micro-identities to encompassing groups) and there seem to be many spelling problems (e.g. Bakwa Kalonji, Bakua Kalonji, Mukua Kalonji).

We cleaned up the data with the use of multiple ethnographic and historical sources (Vansina Reference Vansina1966; Ndaywel è Nziem Reference Ndaywel è Nziem1998; de Saint Moulin Reference de Saint Moulin2003; Bruneau Reference Bruneau, Omasombo and Bouvier2014; Simons & Fennig Reference Simons and Fennig2018),Footnote 9 as well as the available volumes of Belgium's Royal Museum of Central Africa's provincial monographs (Omasombo Reference Omasombo2014, Reference Omasombo2017), and with the assistance of Congolese colleagues from Lubumbashi, Kinshasa, Bukavu and Kisangani, with whom we held several working sessions. We were able to identify 330 groups. We then created a list of 84 larger ethnic groups that comprise all 330 groups. Not all these groups have many members but all of them constitute, culturally or politically, what the Congolese call a tribe at a conceptually similar level and a degree of aggregation.

We acknowledge that there is an impressionistic element to our method but the aggregation decisions were rarely controversial, as most of our sources converged. Given the fluidity of ethnic identity and the dated nature of some of our sources, we attempted to use categories that were as relevant as possible to contemporary politics. For example, we broke down the ‘Southern Katangese’ category used by Vansina into groups that are currently salient in Katangese politics such as the Bemba, Sanga, etc. Most of the time, we allocated smaller groups to their larger category. Thus, the Bakwa Kalonji are Luba and the Ekonda are Mongo. But there are times when a sub-ethnic identity has acquired sufficient political salience to be considered separately. For example, while they are historically and culturally related to the Mongo, the Tetela are widely seen as their own ethnic group.Footnote 10

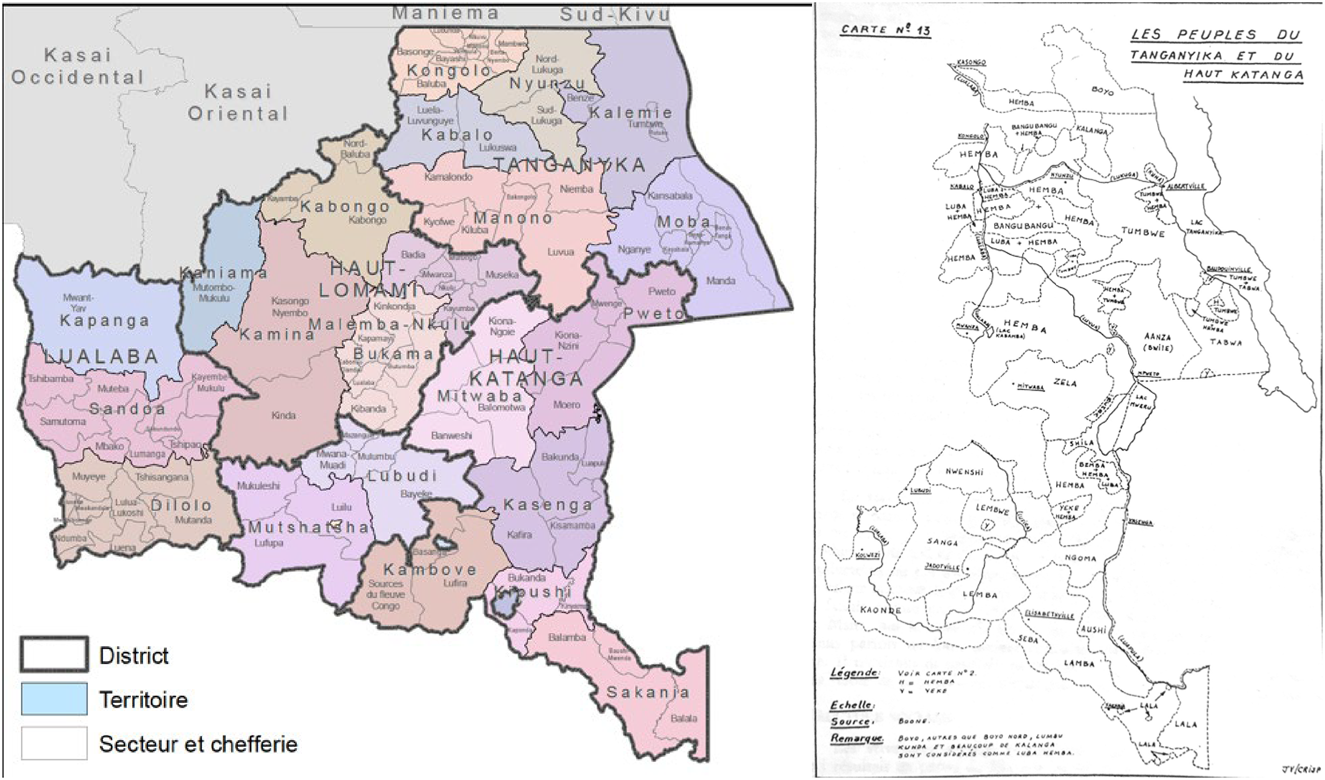

To assess the issue of provincial autochthony (i.e. whether people reside in their alleged province of ancestral origin), we identified the tribes that can claim originaire status for each of Congo's 145 territories and 21 towns. When people belong to such a tribe in the relevant province, we deemed them originaire; otherwise, not. We identified originaire tribes by matching the scale of the ethnic maps in Vansina's (Reference Vansina1966) opus Introduction à l'ethnographie du Congo with the maps of Congo's territories in the Atlas de l'organisation administrative de la République démocratique du Congo by de Saint Moulin and Kalombo Tshibanda (Reference de Saint Moulin and Kalombo Tshibanda2011). Figure 1 illustrates our process. This approach was necessary because Vansina maps out Congo's ethnic groups in 11 broad cultural areas as opposed to current administrative divisions. Although Vansina's work is dated, the notion of originaire refers to the presumed original inhabitants of a region and is thus not as fluid over time as ethnicity per se. Moreover, we supplemented this method with data from the Cellule d'Analyse des Indicateurs de Développement, a contemporary database connected to the Congolese Prime Minister's office, which frequently mentions autochthonous groups by territory.Footnote 11

Figure 1 Our identification method for originaires involved matching maps such as the one on the right (rescaled for this purpose), with the relevant parts of the one on the left and imputing groups to the corresponding administrative units.

While it is somewhat artisanal, our process produced categorisations with prima facie validity in view of local politics and in the eyes of our Congolese colleagues. Within a reasonable margin of error and despite a few possible glitches, we are confident that our data represent a broadly reliable overview of the distribution of ethnic groups across Congo and its new provinces and of those with bases for autochthony claims. To our knowledge, ours are the only such estimates.

In order to assess ethnic representativeness, we compared the proportion of an ethnic group in a province with the ethnic distribution of the provincial government. Over-representation implies a greater proportion in government than in population and vice versa for under-representation. A group without a member in government is unrepresented. We coded the ethnicity of provincial ministers from multiple sources, including Omasombo (Reference Omasombo2009), and information collected during fieldwork in the provinces of Haut-Katanga, Haut-Lomami, Kinshasa and Lualaba in May, June and October 2017, as well as June and November 2018. During these trips, we carried out some 80 elite interviews with politicians, administrators, scholars and civil society leaders, and we held work sessions with Congolese colleagues to collectively confirm the ethnicity of provincial political elites.

A SHORT PRIMER ON KATANGA

Much of the qualitative empirical material in this paper comes from the provinces of former Katanga, where we did most of our fieldwork. Katanga, rich in copper and cobalt among other minerals, is the region of the DRC that makes the largest contribution to GDP. The multiple mining companies that operate there, together with a vibrant artisanal mining sector and the attendant service industry, have attracted domestic and international workers over the years.

Katangese politics has been eventful. The province unsuccessfully seceded from the rest of the country from 1960 to 1963, provoking the first UN mission to the country. President Mobutu, who renamed it Shaba, sought to tame it politically but could not avoid additional insurgencies in the 1970s, one of which only ended after French paratroopers intervened. With democratisation in the early 1990s, Katanga saw significant violence against non-autochthonous populations and the expulsion of more than 100,000 Kasaians from the province.

From 1990 until the first provincial elections of 2007, Katanga was under the control of Lubakat politicians, an ethnic group from the north of the province to which Joseph Kabila traces part of his ancestry. With the election of Moïse Katumbi as Governor in 2007, provincial politics saw the rise of southern groups such as the Bemba and the Sanga. The découpage of 2015 led to particular acrimony in the province as it weakened the Lubakat in the new southern provinces, where the minerals are, and gave them control of the much poorer northern ones.

While we present ethnic data and provincial governors’ ethnicity for the whole country, most of our analysis focuses on Katanga. While the region has a special position in Congolese history, issues of provincial ethnic representation are not different there from elsewhere. Katanga mostly differs in terms of its large number of non-autochthonous populations, a difference which allows for greater salience of the autochthony issue and facilitates analysis.

DÉCOUPAGE AND PROVINCIAL ETHNIC HOMOGENISATION

Découpage was included in the 2006 Constitution and resulted from demands during the 1992–94 National Sovereign Conference and the 2003–2006 post-conflict transition for a thorough decentralisation of the state (Omasombo & Bouvier Reference Omasambo and Bouvier2014). In its 1964 constitution, Congo had already had a brief experiment in decentralisation with the creation of 22 relatively autonomous provinces (compared with six provinces at the time of independence in 1960), which were largely derived from colonial administrative units. Under the highly centralised Mobutu regime (1965–97), these provinces became districts within larger non-autonomous provinces, which numbered from six to 11 (de Saint Moulin Reference de Saint Moulin1988). By and large, these same 22 provinces form the basis of the new post-découpage provinces.

For the constituents in the 2003–06 transition parliament, to broadly return to the provinces that existed in the early 1960s was partly a matter of convenience, as designing new boundaries would have greatly taxed the state's limited capacity.Footnote 12 It was also politically motivated, as several of the 1964 provinces offered politicians more ethnically homogeneous home bases. Indeed, given the geographic clustering of ethnic groups, smaller administrative units are usually more ethnically homogeneous than larger ones. In the early 1960s, the chaos that had followed the country's independence had nurtured a desire among politicians for greater ethnic ownership of provincial structures. For example, the Katanga secession of 1960–63 was in part an act of rejection of Kasaians by Lunda and some other southern Katangese ethnic groups. In response, the Lubakat, opposed to the secession, set up the North-Katanga province in what is today Haut-Lomami. Similarly, the secession of South Kasai in 1962 was a Luba reaction to political competition with the Lulua. In the north, the Mongo – frustrated at their minority status in the Equateur province – pushed for the Cuvette Centrale province where they dominated. Progressively, from 1960 to 1962, 15 new provinces were created, many following the demands of particular ethnic groups. With its 22 provinces, the 1964 Constitution enshrined this evolution, until Mobutu put an end to this experiment (Young Reference Young1965).

By breaking up some of Congo's provinces and returning to a geographic provincial layout that largely emulates that of 1964, découpage reconfigured the territorial mapping of state institutions and reshuffled provincial ethnic distributions with the main result that it led unambiguously to an ethnic homogenisation of provinces. While only Bas-Congo, North Kivu and possibly Kasai Occidental (or up to 27% of existing provinces) had a majority ethnic group before découpage (respectively the Kongo, the Nande and the Lulua), 11 (41%) of the post-2015 provinces have a clear majority ethnic group, with one more (Tanganyika) coming close, for a grand total of 46% of the provinces (Table I). In the divided provinces, the ratio of the largest ethnic group to the second largest ethnic group went from 2.3 to 4.7. In every new province except Kasai and Haut-Katanga, the degree of ethnic heterogeneity fell compared with the previous province. As a result, the main post-découpage pattern is that ethnic groups that were dominant in their previous province generally see their dominance reinforced in the new ones, while groups that were a plurality or among the largest two or three of their provinces either become a dominant majority or see their plurality increase.

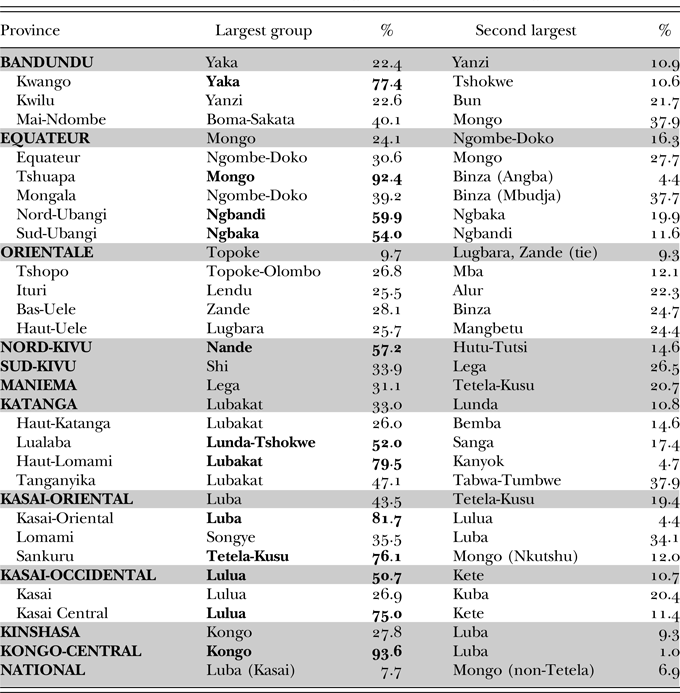

Table I Estimates of largest ethnic groups by old and new provinces.

Source: Authors' coding and estimations based on ‘tribu’ variable in INS (2012). Majority groups in bold.

Take the Tetela, for example. While they represented about 19% of the population of former Kasai Oriental, they are now 76% of Sankuru, which is, for all practical purposes, a Tetela province. Similarly, the Lubakat, once about a third of Katanga, are now 80% of Haut-Lomami, and the Luba, who were 43% of Kasai Oriental, are 82% of the new province of the same name. A similar pattern applies to most groups in Table I, although, for some, the rise is more limited. In every new province except Kasai and Haut-Katanga and Lomami, the dominant group has a larger proportion of the population than before découpage. In no province has the dominant group less than 22% of the population, and the average is 46%. Not only are all new provinces more ethnically homogeneous than the corresponding pre-découpage ones, all are also more homogeneous than the country as a whole. We calculated that for Congo, the ethnic fractionalisation index (using the Herfindahl formula) is a very high 0.97. For Tshuapa, for example, where most people are Mongo, it is 0.14.

DECENTRALISATION AS IMPEDIMENT TO ETHNIC REPRESENTATIVENESS

Past and national practices of representativeness

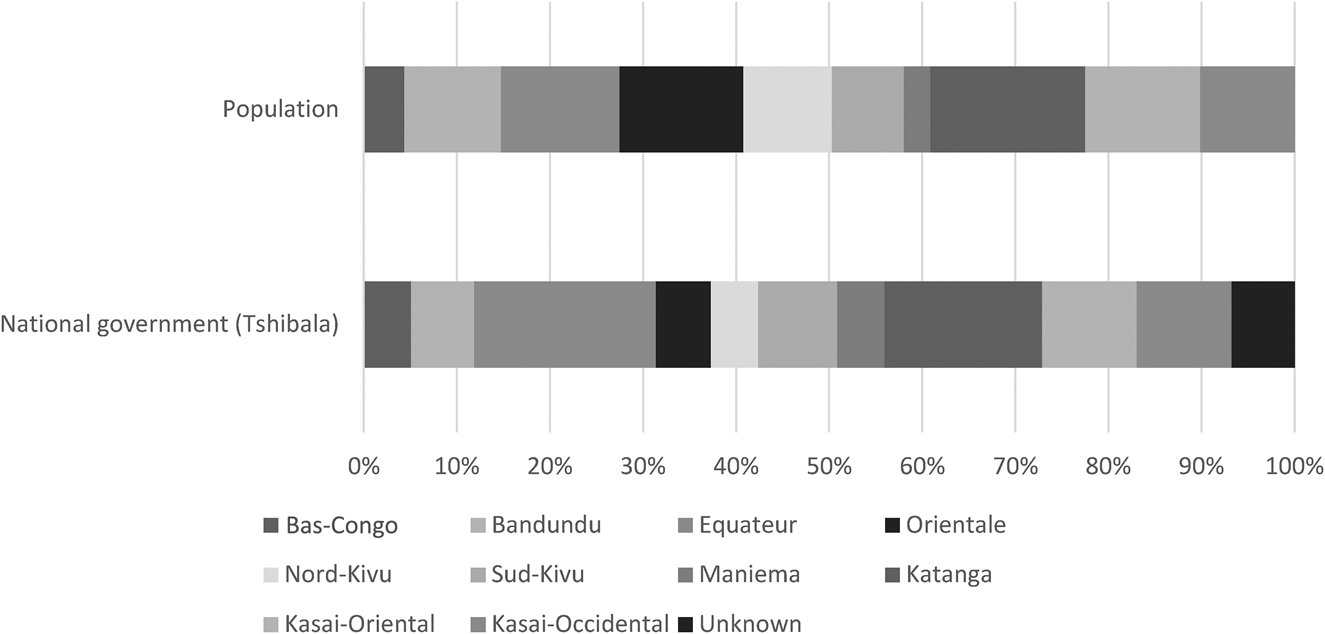

Figure 2 illustrates the practice of representativeness at the national level, comparing the provincial distribution of the 59 ministers in the 2017 Tshibala government with the corresponding provincial population distributions. For ease of presentation, it uses the 11 provinces (minus Kinshasa) that were in existence until 2015 and continue to carry significant weight for national representational purposes. Figure 2 shows the robustness of representativeness at the national level, as the proportion of ministers by province corresponds to their share of the total population. Some provinces are somewhat over-represented, like Equateur (which contains several important tribes at the national level, such as the Mongo, Ngombe, Ngbaka and Ngbandi, all of which are large enough to demand some representation). Others are somewhat underrepresented, like Province Orientale (that lacks dominant tribes) or conflict-ridden North Kivu, but, by and large, the two distributions match well.Footnote 13

Figure 2 Representativeness in national government, by former province (2018).

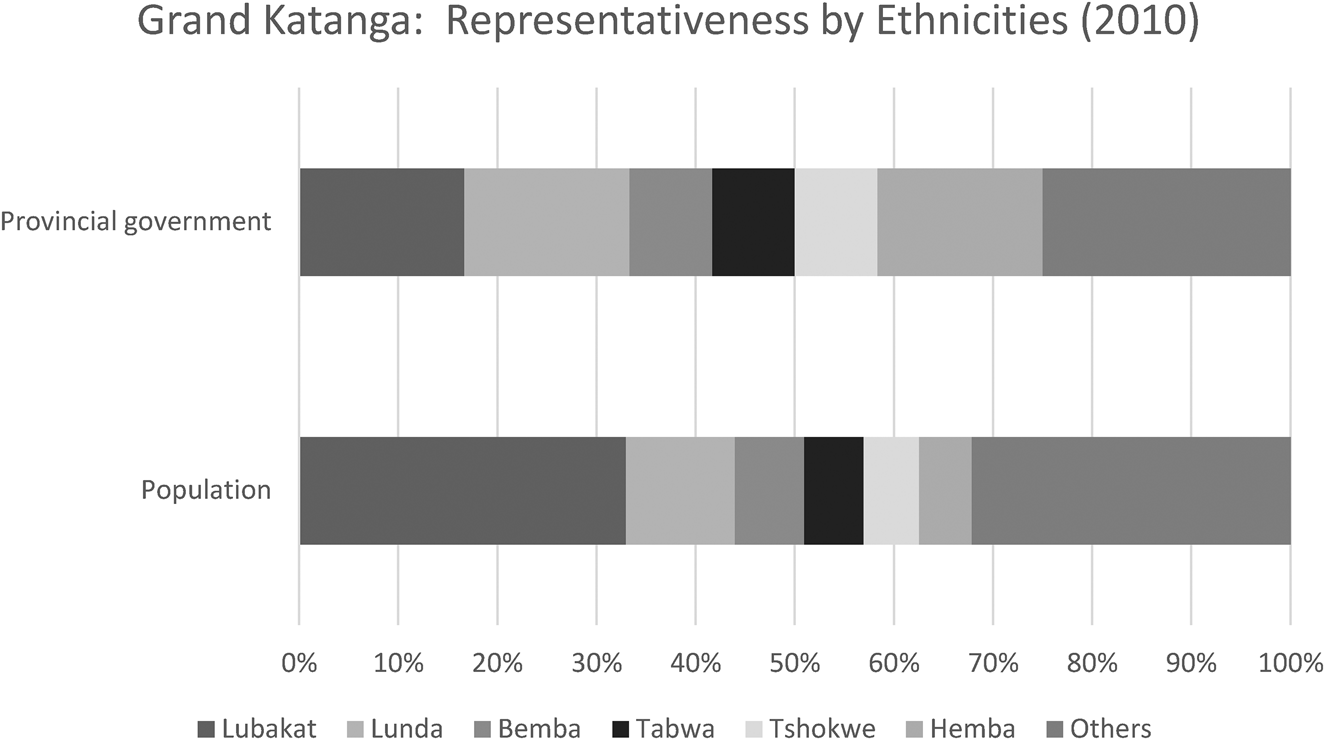

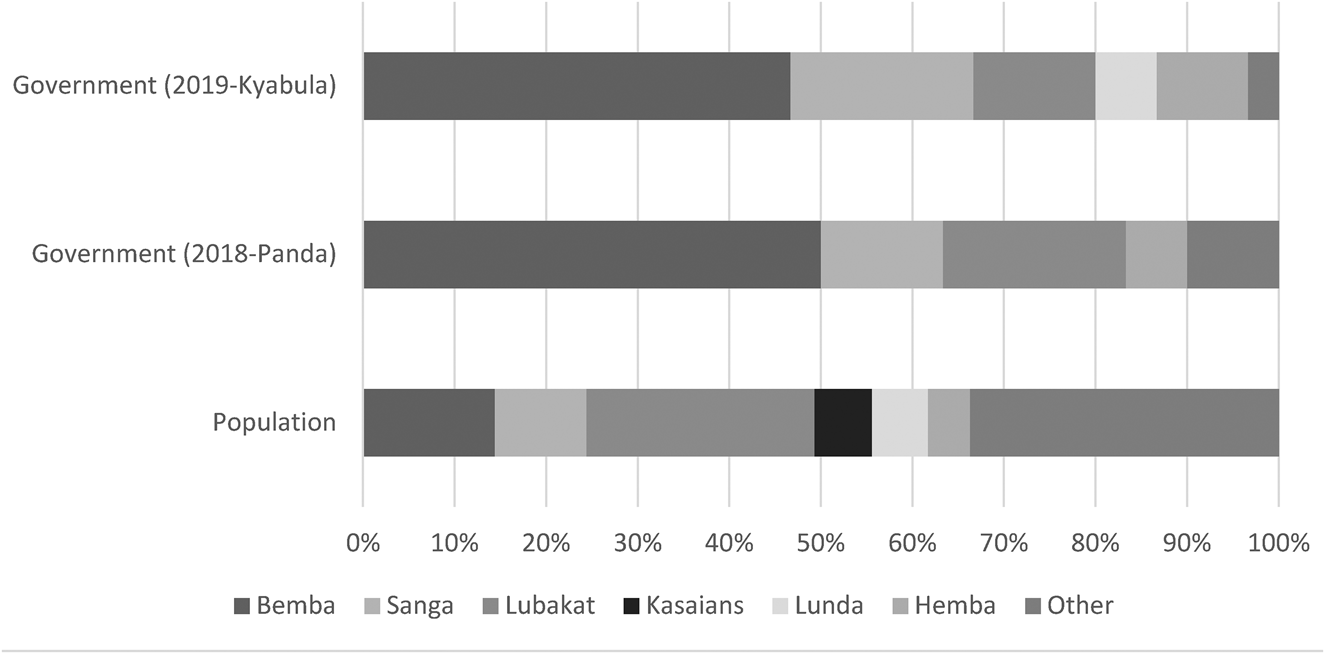

Using the example of the pre-2015 Katanga province, which contained almost 17% of the country's population, Figure 3 illustrates the application of ethnic representativeness at the provincial level (as of 2010). The Lubakat were underrepresented and the Hemba and Lunda overrepresented, each with two ministers. All the other large groups were represented (the category ‘Others’ included a Lamba, a Sanga and a Zela). While the governor's own ethnic group, the Bemba, only had the governor to represent them, his district of Haut-Katanga had four out of 12 positions.

Figure 3 Representativeness in Grand Katanga.

There are several practical or political reasons why the ethnic distributions in the populations and in the governments do not match perfectly. First, there are no official estimates of populations by ethnic groups. Hence, the practice of representativeness is based on impressionistic assessments, which might benefit more salient groups, like the Lunda. Second, with 12 government positions in Katanga, groups can only be represented in increments of 1/12 or 8.3%. Groups whose population proportion does not match a multiple of 8.3% are systematically under- or over-represented. Third, political influence tweaks the parameters of representativeness: a group with a strong connection to Kinshasa can expect to see its representation somewhat inflated. Correspondingly, groups associated with opposition politicians can suffer from under-representation. Normally, this phenomenon is mitigated by the fact that ethnic groups tend to have politicians on either side of the majority-opposition divide at any time. Fourth, representativeness is a repeated game. Despite ups and downs, all groups of sufficient size get representation over time. Hence, the apparent under-representation of the Lubakat in the 2010 Katanga executive obscures the fact that this ethnic group controlled the governorship almost without interruption from 1998 to 2006. Finally, while we focus on ministers, representation applies more broadly to other positions as well, such as those in the provincial assembly bureau (the speaker in 2010 was Gabriel Kyungu, a Lubakat) or in the top echelons of political appointments (Governor Katumbi's chief of staff (Directeur de Cabinet), Huit Mulongo, was also Lubakat).

Post-découpage ethnic monopolisation

By (re-)creating provinces that are more ethnically homogeneous, découpage has upended the practice of representativeness in two major ways. First, based on evidence from the provinces of former Katanga, new provincial governments eschew balanced representation and tend towards the ethnic monopolisation of provincial power by the dominant groups. Second, for the country as a whole, découpage has brought about a resurgence of autochthony discourses applied at the level of new provinces. The practice of ethnic groups claiming originaire status to a province derives from the perceived necessity of limiting the number of claimants to representation. It has been underpinned by the automatic rise provoked by découpage in the proportion of individuals who cannot claim ethnic autochthony to their province of residence.

Executive ethnic monopolisation

Découpage has caused a realignment of territories, politicians and ethnicities, which appears to be eroding or transforming the norm of representativeness. Although the findings we present here are limited to the four provinces that used to form Katanga, our data suggest that, as provinces get smaller and ethnically more homogeneous, the principle of representativeness becomes harder to implement. There are indeed fewer incentives for representativeness when one group accounts for more than 50% of the population. At the national level, where the norm originates, no single group has more than 7.7% of Congo's total population, giving many groups plausible grounds for claims of representation. But in many of the new provinces, majority ethnic domination fundamentally changes the game of representativeness and reduces incentives for inclusiveness, with the result that the demographically dominant groups move towards monopolising provincial institutions and the proportion of population unrepresented by ethnicity in these institutions increases. For parsimony, we focus here on the provincial governments of Haut-Katanga, Haut-Lomami and Lualaba, but Tanganyika displays a similar pattern.Footnote 14 Provincial governments are made up of the governor, vice-governor and a cabinet constitutionally limited to 10 members, but to which several provinces add ‘special commissioners’ with the rank of provincial ministers, to bypass the size limitation.

Evidence from these provinces hints at a deliberate effort by dominant groups (or, in Lualaba, a coalition of related groups) to expand their presence in government beyond their demographic weight, thereby increasing the size of the population that belongs to unrepresented groups, a significant departure from the past practice of representativeness. In Haut-Katanga (Figure 4), it is the Bemba and the closely related Sanga who have taken over control of the provincial government. Although they are not the largest tribes in the province, they are the largest ones that can claim autochthonous status, something the larger Lubakat cannot easily do (see next section). While the Bemba (former Governor Jean-Claude Kazembe's group) are about 14% of the province's population, and the Sanga (of current governor Jacques Kyabula) a mere 10%, they together made up 64% of the provincial government before the 2018 elections, and 66% of the one since then. The homogeneity of the provincial government contrasts with the heterogeneity of the population, with five groups (Bemba, Lubakat, Lunda, Sanga and Hemba) monopolising all positions,Footnote 15 leaving 40% of the province's population belonging to an ethnic group that is not represented in government.Footnote 16

Figure 4 Bemba-Sanga Takeover in Haut-Katanga.

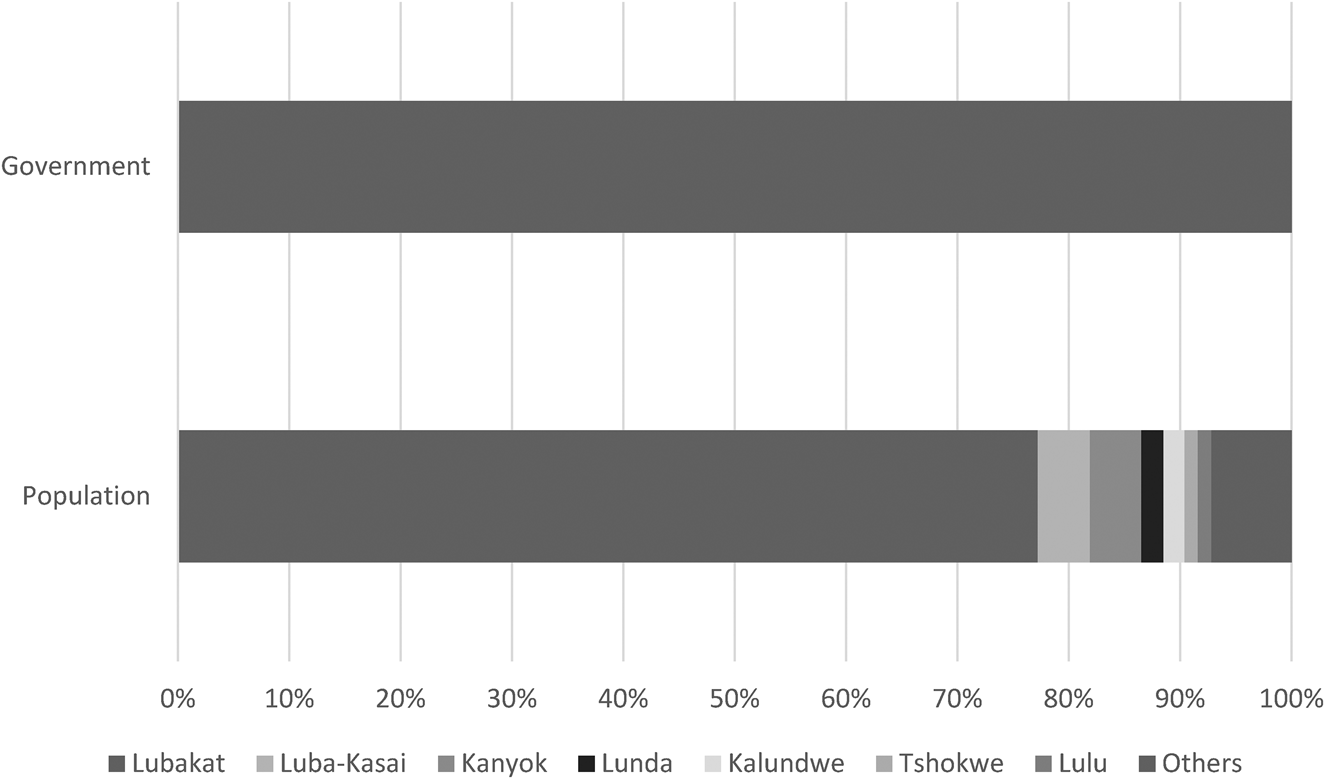

Given the reach of the Bemba, one can imagine the representation grab larger groups might launch in other provinces. Haut-Lomami provides a telling example, as it is the province where the institutional monopolisation process has reached the furthest. While that province already has a strong Lubakat majority (80%), this group has taken full single-ethnic control of the government (which has 14 positions available), leaving 21% of the population unrepresented and leading to ethnically homogeneous government (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Lubakat takeover in Haut-Lomami (2018).

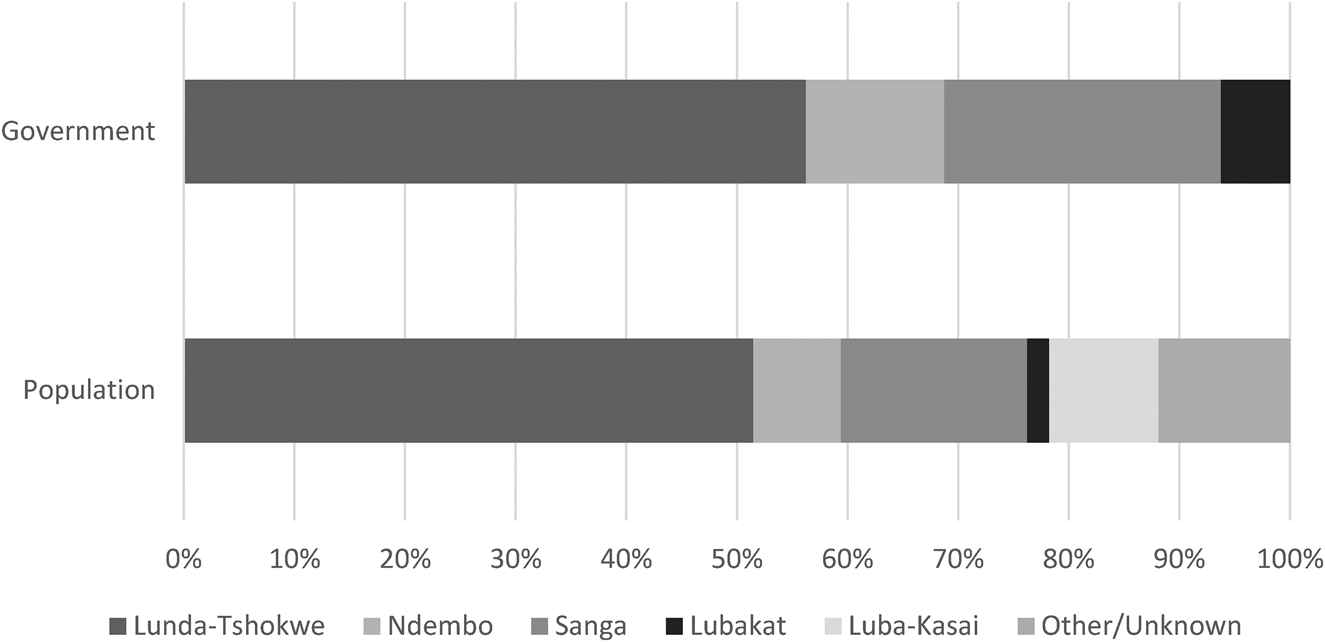

In Lualaba, the Lunda-Tshokwe are the dominant ethnic group. They are also very close to and politically aligned with the Ndembo (8.3%), the Lwena (1.3%) and the Minungu (less than 1%), with whom they form a coalition named Tshota. While the Lunda-Tshokwe control the majority of government seats on their own (and the governorship with Richard Muyej), their domination is expanded through the Tshota alliance, as they occupy 70% of the seats in the provincial executive with the Ndembo (for 60% of the population). The Sanga, who come from the Kolwezi region, wanted their own province and generally express grievances at their domination by the Lunda-Tshokwe in Lualaba. Their apparent over-representation (25% of government for 16% of the population) (Figure 6) appears to be the consequence of the co-optation (in more minor government positions) of some of their elites by the governor.

Figure 6 Lunda-Tshokwe takeover in Lualaba (2018).

Altogether, we can estimate the effects of découpage on representativeness by adding up the amount of people who belong to unrepresented groups. Before découpage, the total population of Katanga unrepresented in provincial government was 2.24 million. After découpage, it is 3.41 million. Altogether, 25% of Katanga's population is now ethnically unrepresented in provincial governments. This evidence suggests that découpage erodes tribal representativeness and promotes tribal monopolisation of provincial institutions to the benefit of the larger groups, particularly when the latter are an absolute majority.

The pattern we observe in former Katanga provinces seems to replicate across the country in all provinces that have an ethnic majority. Although we do not have ethnic data on all provincial governments, we have it for all provincial governors. As of 2019, all the governors of provinces with an ethnic majority came from the province's dominant ethnic group. Of the other provinces, 31% had a governor of the same ethnicity as the largest group in the province. This finding suggests a transformation of the political contract in ethnic-majority provinces, whereas the rest of the country continues to operate under the rules of pluralistic representativeness.

Given the historical prevalence of the norm of representativeness in Congolese politics, how can we make theoretical sense of the monopolisation of power by demographically dominant groups? Recalling the notion of ‘minimum winning coalition’ is a useful step (Riker Reference Riker1962). According to this concept, individuals choose, out of a given repertoire, the ethnic identity that maximises their chance of access to power while minimising the size of the coalition with which they must share its spoils. By virtue of the demographic size of their respected identities, some groups find themselves systematically excluded from winning coalitions (unless they can change the terms of the identity debate and introduce as politically relevant new cleavages that might give them access to a winning coalition).

With the principle of representativeness, Congolese politics largely eschews the exclusionary logic of minimum winning coalitions. It is possible that the trauma of exclusion that ushered the country into a rapid descent into civil war and secession attempts at independence made such politics too much of a threat to the very existence of the country and moved such coalition building to the realm of the politically unthinkable. Of course, some groups have dominated Congolese politics at one time or another (e.g. the Ngbaka and Equateur under Mobutu, the Lubakat and Katanga under Kabila), but they have included in their regime and government as wide a coalition of other groups as possible, as illustrated earlier. In short, the ‘plural softness’ (that is, its lack of ownership by any specific group) of a multiethnic African post-colonial state like Congo might have been crucial to its survival (Neuberger Reference Neuberger and Chazan1999).

Conflict and secessionism are not only features of national politics in Congo; they have also applied at provincial levels. Recall that when Katanga seceded from Congo in 1960 under the impetus of southerners such as the Lunda, northern Katanga and its Lubakat population in turn seceded from Katanga. Similarly, when the Mongo felt unrepresented in Equateur, they broke up and established the Cuvette Centrale province. And the Luba of Kasai set up the Great Mining State of South Kasai in 1960 partly as a reaction to Lulua domination of their province. By and large, the creation of multiple new provinces from 1960 to 1964 represented a secession-like process whereby groups that felt excluded or under-represented sought to acquire their own provinces. The rejection of this model (associated with a chaotic and violent period of Congo's history) and the reduction of the number of provinces by Mobutu starting in 1967, brought the necessity of plural softness to the level of provinces. If they were to endure, Congo's provinces had to be inclusive, like Congo itself (de Saint Moulin Reference de Saint Moulin1988: 218). Hence, the norm of representativeness spread to provinces.Footnote 17

The break-up of existing provinces in 2015 seems to have brought minimum-winning-coalition politics back into play, which has led to the exclusionary monopolisation of provincial governments by dominant groups. One can think of two reasons for this evolution. First, as discussed above, the demographic reconfiguration brought about by découpage has raised the number of groups that find themselves in provincial majority position, reducing incentives to share power. Second, these groups have been empowered to practice exclusionary politics because further sub-provincial division is not a realistic option. Although the possibility to further subdivide or merge existing provinces is acknowledged by Article 4 of the Constitution, it is hard to imagine a scenario wherein it would currently be feasible.

There are at least three reasons for this effective prohibition. First, as Table I indicates, with the possible exception of Tanganyika, there is no configuration of ethnic distributions in majority-dominated provinces where the second group is large enough to be able to sustain a plausible claim to having its own province. In addition, there is always more than one other group and these groups also tend to be in competition with each other, reducing opportunities for collective action among excluded groups. Second, unlike in countries such as Nigeria under military dictatorship or Uganda under Museveni where new states or districts were and are created at the apparent stroke of a pen, there is considerable rigidity in the Congolese provincial configurations, which mostly date back to the colonial period. Finally, and relatedly, the one case that has so far sought to produce a provincial territorial realignment – that of the Sanga of Lualaba province, on which more below – has not obtained any traction, despite the apparent validity of the Sanga's claims that they were forcibly included into Lualaba in violation of an earlier agreement that they would form part of Haut-Katanga. For these different reasons, un- and under-represented groups might have little agency in terms of exiting from current provinces, with the result that deviating from representativeness has become politically feasible in provinces dominated by one group.

DÉCOUPAGE AND SHRINKING PROVINCIAL AUTOCHTHONY

In addition to promoting ethnic homogenisation, découpage's reshuffle of provincial boundaries has also changed the provincial autochthony status of millions of Congolese, leading to serious political struggles over who is or is not originaire of their province of residence. Before découpage, for example, the Lubakat were all originaire of Katanga, where they constituted 33% of the population. Now they are unambiguously originaire of all of Haut-Lomami's territories and of most of Tanganyika's territories. But in Haut-Katanga, where they still constitute some 26% of the population, their status is ambiguous as they only claim chiefdoms in Kasenga and Mitwaba territories. Thus, the majority of Lubakat in Haut-Katanga, those without personal origins in these territories, are considered non-originaire by others in the province. In Lualaba, where they appear less numerous, with possibly as little as 2.5% of the population, Lubakat claim originaire status in Lubudi and Mutshatsha territories only (president of a socio-cultural association and professor at UNILU, Lubumbashi, Haut-Katanga, 3.6.2017), but this claim appears to be rejected by other provincial autochthonous groups. For example, the Rassemblement des Communautés du Lualaba (RCLU), an association of mutuelles of self-described originaire groups, does not include Lubakat representatives. Instead, they recognise a loosely related hybrid group, the Sanga-Luba (National Deputy, Kolwezi, Lualaba, 21.6.2017; Head of Provincial Tourism Division, Kolwezi, Lualaba, 22.6.2017). Tellingly, in our interview, the province's Vice-Governor, Fifi Masuka Saini, a Ndembo, referred to the Lubakat as ‘our brothers from next door’ (Vice Governor, Kolwezi, Lualaba, 19.10.2017), in reference to Haut-Lomami province. Thus, with representativeness construed in autochthonous terms, the Lubakat, who for years dominated Katanga politics, lose much of their case for representation in Haut-Katanga and Lualaba, the two richest Katanga provinces.

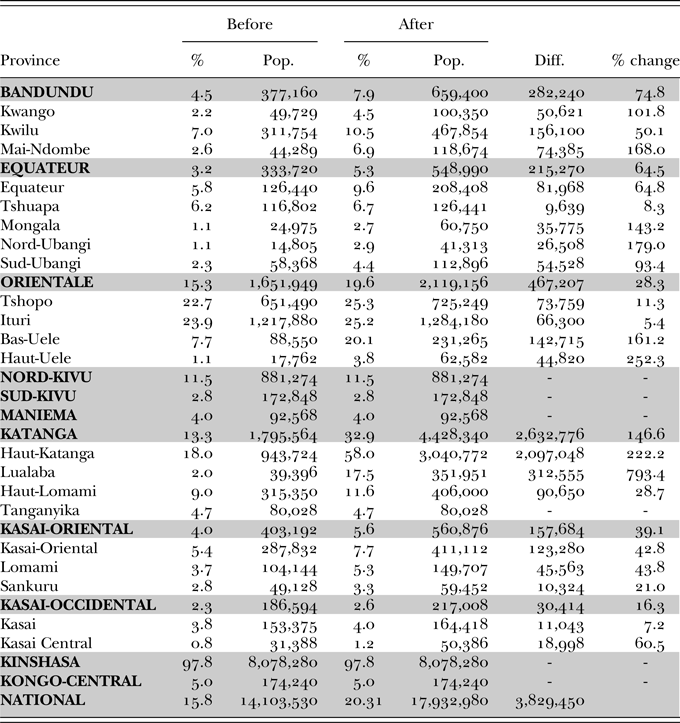

Our data suggest that this is a significant issue, as the proportion of non-originaires has increased in all provinces in the wake of découpage, leading to a rise in the proportion of Congo's population that is unrepresented, despite decentralisation's goal of bringing government closer to the people. Table II captures the rise of non-originaires in every province. We estimate the total amount of non-originaire Congolese before découpage at 15.8% of the population or about 14 million. After découpage, the number is 20.3% or about 18 million.Footnote 18 Thus, almost four million Congolese who were originaire in their former province no longer are in their new one.

Table II Estimates of non-originaire population by province before and after découpage.

Source: Authors' calculations, based on INS (2012).

In absolute terms, the rise in allochthony is largely a Katangese problem, as about 2 million of the new non-originaires are in Haut-Katanga (most of them are Lubakat). Another 300,000 are in Lualaba. In relative terms, however, there are eight provinces in which the number of non-originaires more than doubles and another four where the rise exceeds 50%. Although these provinces have smaller proportions of non-originaires than Haut-Katanga to begin with, their increases are not insignificant in local demographic and political terms. In three provinces of former Orientale Province, for example, more than one-fifth of the population are now non-originaire.

This evolution appears to have introduced a gradation in citizenship, which has resulted in a two-tier system of collective representation. Some groups, mostly larger ones that exceed 2% of the population at the national level, get their own province or are able to dominate one. They include the Kongo, Luba, Lubakat, Lulu, Lunda, Mongo, Nande, Ngbaka, Ngbandi, Ngombe, Tetela and Yaka. The population of these groups adds up to 66% of Congo's total population, with the consequence that one-third of the Congolese belong to an ethnic group without its ‘own’ province and thus with lesser provincial representativeness. It is an empirical question whether the under-representation of these groups and others will lead them to challenge the country's institutional structure or encourage identity adjustments and alliances. It is worth noting, however, that découpage represents a significant shock and has caused a disequilibrium of the system of tribal representativeness, which brings further potential instability for the country at least in the short to medium term. At a time when the institutions and rules of formal democratic representation have been largely hollowed out, the decline in collective representation stands to compound the political alienation of many Congolese and could undo the potential benefits of decentralisation in terms of local representation.

However, it is also worth noting that this evolution is not short of legitimacy for many Congolese, nor is it historically unprecedented. While leading to local monopolies, provincial tribalisation might reproduce a different form of national representativeness, in which provincial institutions are claimed by specific autochthonous groups. From a national perspective, this results in the most significant groups ending up with a stake in the state. In this sense, the current evolution marks a re-appropriation of the state by culturally meaningful categories of collective action at the local level and, as such, a degree of dis-alienation for many. But so far it is not without a high price for many others, who see their own vulnerability increase in the process.

Our fieldwork suggests that the exclusionary effects of autochthony are acutely felt in provincial administrations. After découpage, Haut-Katanga found itself over-staffed, as many former Katanga civil servants remained in Lubumbashi. Governor Jean-Claude Kazembe, a Bemba, reportedly posted lists of individuals who could keep their provincial employment in the new administration. According to Congolese interviewees claiming to have seen the lists (we did not), some 90% of those on them were from ethnic groups deemed originaire of Haut-Katanga. The prevailing discourse then was ‘It is our province. You can go get jobs in your province.’ In the words of an autochthonous ethnic leader, ‘unfortunately, our towns have Congolese from other provinces, thus we need to negotiate. … Now, … provincial natives are beginning to find their interest’ (National Deputy, president of a socio-cultural association, and church leader, Lubumbashi, Haut-Katanga, 6.6.2017).

With public employment at least partly based on patronage, there were few payoffs for Governor Kazembe to keep non-originaires in provincial positions. Given the material and human tolls this policy imposed, it triggered significant tensions and pushback. Non-originaires complained of the ‘tribalism’ of the Kazembe administration and often asked ‘who built Katanga?’ (vice president of a socio-cultural association, Lubumbashi, Haut-Katanga, 29.5.2017), in reference to their contributions to the province. Tensions even surfaced within the Kazembe cabinet as his Vice-Governor, Bijou Mushitu Kat, herself a Lunda from Lualaba, took issue with the governor's autochthonous discourse and claimed ‘I am at home [in Lubumbashi]’, before resigning (president of a socio-cultural association, Lubumbashi, Haut-Katanga, 31.5.2017). We found similar dynamics in Lualaba and Haut-Lomami.

It is worth noting, however, that the fluidity of ethnic identities implies that greater autochthony and ethnic domination might not always translate into effective provincial homogeneity. In Haut-Lomami, for example, where all provincial government positions are occupied by Lubakat politicians, there has been a degree of instability (with Governor Célestin Mbuyu impeached by the provincial assembly in May 2017) as a function of perceived unfair representation of the different provincial territories in the government. Thus, the line of cleavage appears to have moved from the ethnic level to the lower territory level, with Lubakat politicians stressing their territory of origin within the province as their salient identity.

CONCLUSIONS

Our research indicates that decentralisation has provoked considerable change to the Congolese political system. In addition to fostering more ethnically homogeneous provinces, it has led to frequent takeover of these provinces by dominant ethnic groups. This evolution runs generally counter to the Congolese, and more generally African, political norm of representativeness, according to which most ethnic groups can expect to have representatives in state institutions, and has heightened political exclusion for unrepresented groups. This exclusion has been compounded, particularly in some provinces of former Katanga, by the effects of découpage on autochthony, as an increased number of citizens belong to ethnic groups now deemed non-autochthonous of their province of residence.

There are significant risks to this exclusionary trend. There is indeed ample literature pointing to ethnic exclusion as both an element of state formation and a source of conflict (for example, Stewart 2008; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2012; Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug2013). Moreover, Eastern Congo's own experience with political violence, fed by autochthony narratives and practices, stands as a warning that the increased numbers of non-autochthonous in Congo's other provinces may fuel conflict in the future.Footnote 19 Although their motives are not always easy to identify, the recent violence of Kata Katanga, an insurgent group headed by Gédéon Kyungu Mutanga, a Lubakat, in Haut-Katanga, fits the pattern (MONUSCO 2020: 9–10). Similarly, Tanganyika has witnessed over the last few years conflict between unrepresented ‘Pygmies’ and so-called local ‘Bantu’ groups such as the Lubakat and Hemba. And in Lualaba, we met with Sanga activists who did not rule out resorting to violence in the future to fight off perceived Lunda domination.

On the other hand, the ethnic homogenisation of many provinces suggests the potential for greater state ownership by local communities, improved collective action and possibly better governance. This latter effect appears conditional, however, upon ethnically homogeneous provinces not splitting up along some sub-ethnic line of cleavage (such as clans or territories), as is increasingly the case in Haut-Lomami province, for example.

At any rate, decentralisation and the multiplication of provinces have largely upended the practice of politics in Congo. While the apparent paralysis of national politics and the continued dominance of the Kabila regime under the new presidency of Felix Tshisekedi since January 2019 have gathered most of the attention, it is provincial politics that affects the majority of the Congolese the most in their regular interactions with the state. Resources, patronage, access, representation and other modes of political action are exercised first and foremost at the local and provincial levels. It is too early to assess what kind of aggregate effects provincial ethnic domination might end up having. However, given Congo's weak institutional environment, the relative prevalence of political violence in several regions of the country, widespread poverty, and the salience of ethnicity, concerns over the increased exclusion and alienation brought about by découpage are not unreasonable.