Within the year of the election of President Rodrigo Duterte in May 2016, the competing Bangsamoro armed formations of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) separately but simultaneously engaged the government in a new round of peace processes. Both formations are moving closer to finalise a comprehensive peace agreement for a territorial autonomy with the Philippine government and to end nearly half a century of violent secessionist warfare that in turn repeatedly displaced millions of people in the Muslim enclaves of the southern island of Mindanao in the Philippines (Ahmad, Reference Ahmad and Gutierrez2000; Oquist, Reference Oquist2002). Coincidentally, however, these remarkable initiatives were overshadowed by a fresh round of violence launched by new rebel formations such as the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) in the villages of Maguindanao and North Cotabato on the one hand, and the so-called Maute Group in the Islamic City of Marawi in May 2017 on the other.

The continuing cycle of war-and-peace accords laid bare the intricate dynamics of the Moro secessionist movements in ways that also raise the question of how the Muslim constituencies that they seek to represent align as well as disentangle themselves from two long-standing but sharply competing ethno-nationalist revolutionary projects. This article examines these configurations by looking at how Muslim communities associate and disassociate themselves with the internal politics of secessionism in the immediate aftermath of the 2013 Zamboanga violence and the forging of the 2014 peace agreement. The latter was signed by former Philippine President Benigno Aquino III as the Comprehensive Agreement for the Bangsamoro. The agreement proposed a Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL), establishing a self-governing territory for Islamised ethnic groups in Mindanao. The proposed law asserted the unified identity of Muslim constituencies in Mindanao as a ‘bangsa’ Moro (Moro nation), with the goal of ending intergroup violence between Christians and Muslims in the southern region of Mindanao (Majul, Reference Majul1973).

Historically, peacebuilding efforts in Mindanao have focused on formation and training that helped increase cultural understandings and tolerance of each other's religions. We believe that understanding the nature of peace and conflicts in Mindanao entails looking beyond the conventional clash-of-religions narrative. Behind this so-called religious divide is an ethnopoliticalFootnote 1 discourse that surfaced in the course of impassioned debates on the outcomes of the peace negotiations and the BBL debates that underpin detailed territorial dominion over land ceded by the dominant Christian state (Montiel, de Guzman, & Macapagal, Reference Montiel, de Guzman and Macapagal2012).

The discourse during peace talks has traditionally been about a single Muslim territory referred to as the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), associated with the Tausug-led MNLF or the Bangsamoro Juridical Entity (BJE) in the 2008 failed peace agreement with the Maguindanao-influenced MILF. The Comprehensive Agreement for the Bangsamoro calls for the creation of an autonomous political entity named ‘Bangsamoro’, replacing the ARMM. Thus, the history of Mindanao peacemaking in the Philippines seems to assume a common identity for Muslims and does not seem to recognise the underlying political and tribal contours in Muslim Mindanao. The current study looks into these ethnopolitical as well as religious social identities of Muslims in Mindanao in the Southern Philippines. It also looks into an emerging superordinate identity, the Bangsamoro identity.

Social Identities and Territorial Conflict

Social identity refers to one's psychological position on any social dimension; this position is shared and is therefore not defined individually. Social identity theory (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1978; Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979) assumes that people strive to maintain positive self-esteem. Because groups contribute to one's self-definition and self-evaluation, people's psychological attachment to their ingroups is an important way in which self-esteem is regulated (Martiny & Rubin, Reference Martiny, Rubin, McKeown, Haji and Ferguson2016).

Simon and Klandermans (Reference Simon and Klandermans2001) theorised about a particular kind of social identity called politicised collective identity. They claim that this type of politicised identity emerges when social actors move as members of a group and are involved in power struggles involving wider contexts beyond the protagonists and antagonists. Politicised collective identities are likewise defined in relation to the public-at-large (Simon & Klandermans, Reference Simon and Klandermans2001) and are saturated with history and culture (Huddy, Reference Huddy2001; Schwartz, Dunkel, & Waterman, Reference Schwartz, Dunkel and Waterman2009; Seul, Reference Seul1999). In Mindanao's war-and-peace historical narrative, politicised collective identities have been evoked as groups grapple with each other in power contestations and also struggle to win over local populations as well as global audiences (Tan, Reference Tan1993).

In territorial conflicts, politicised collective identities are closely attached to the land. Such identities pertain to groups that occupy the contested land, or groups that are seen as invading or grabbing the contested territory. Political identities that arise during territorial conflicts are often associated with religious and ethnic categories. During conflict, politicised religious identities provide moral frameworks, institutions and rituals that meet the psychological and political needs of warring groups. Seul (Reference Seul1999) emphasised the intricate meshing of religious identity and conflict as he claims that ‘the peculiar ability of religion to serve the human identity impulse thus may partially explain why intergroup conflict so frequently occurs along religious fault lines’ (p. 553). One example of a territorial conflict saturated with religious identities is the Israel-Palestine conflict, which evokes the religious categories of Jews versus Muslims, not only within the geographical boundaries of the conflict, but also in a global narrative of Jews versus Muslims.

However, identities evoked during territorial conflicts may not be predominantly religious, but rather ethnic. Ethnic identity is a social identity of group members who are bound together by some combination of common ancestry, shared history, language, and valued cultural traits (Chandra, Reference Chandra2006; Gurr & Moore, Reference Gurr and Moore1997). The largest conceptual subcategory of ethnic identity is a classification that encompasses descent-based attributes (Chandra, Reference Chandra2006). Because ethnic identities are linked with descent and ancestries, such identities hold meaningful implications vis-a-vis two factors crucial in territorial conflicts: territory and religious identities.

First, territory is closely associated with ethnic identity (Buendia, Reference Buendia2005). Individuals who share a common descent and set of ancestors tend to share proximal space; hence, ethnic groups coagulate within defined territorial boundaries (Chandra, Reference Chandra2006). Carrying this argument further, then, territorial discourses evoke ethnic identities.

A politicised ethnic identity emerges when one's reference group shares ‘some combination of common descent, shared historical experiences, and valued cultural traits . . . (activated when making) claims on behalf of their collective interests against either a state or other groups’ (Gurr & Moore, Reference Gurr and Moore1997, p, 1081). The element of common descent is important in politicised ethnic identities, but not in politicised religious identities. The notion of common descent in ethnic identity can be elaborated to include sharing a common ancestral language, place of origin, tribe, or religion. Further, a geographical category can be an ethnic category only if this territorial category includes the place of origin of one's ancestors (Chandra, Reference Chandra2006). We take this argument further and point out that in territorial conflicts, ethnic identities may be evoked more passionately by groups who have had centuries-old attachments to the contested land, rather than by the migrant or settler groups. In the case of Mindanao, the Muslims would be more tied to their ethnic identities than the migrant Christians. Thus, the current research only focuses on Muslims in Mindanao.

In past decades, the concept of politicisation of social identity helped guide social psychological conceptualisation of the idea of ethnopolitical consciousness and its inherent contradiction. The politicisation of identity unfolds when subjective forces move to deploy distinctive narratives of culture and history as strategic issues that define themselves as a collective and rationalise their struggle for power (Huddy Reference Huddy2001; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Dunkel and Waterman2009; Seul, Reference Seul1999; Simon & Klandermans, Reference Simon and Klandermans2001). Politicising social identity to establish ethnopolitical consciousness necessitates that subjective forces differentiate their interest from other ethnopolitical subjectivities in a manner that at times spurs ‘inter-ethnic’ difference and tensions (Ellis, Reference Ellis2010). These views echo earlier analysis illustrating how ethnonationalistFootnote 2 and separatist political formations mobilised specific historical narratives and ethno-linguistic distinctions to evoke the sense of difference so great to the extent that they can never be expected to share a territory, let alone power (Hobsbawm & Ranger, Reference Hobsbawm and Ranger1992; Turton, Reference Turton1998). Moreover, these ideas offer yet still useful analytical frames of understanding identity formations that activate primordial (cultural) and instrumental (material) conditions in defining themselves as a political collectivity with a distinctively political identity.

Competing Identities in Muslim Mindanao

Distinctive language groups in Mindanao, which were subsequently referred as tribes by Bangsamoro scholars, were present even before the arrival of Islam in Mindanao (Jubair, Reference Jubair1999). At around the time Islam arrived in Mindanao through commercial traders, three dominant yet territorially distant tribes had risen to politico-economic superiority and had formed two sultanates. The Tausugs, alongside with ethnic groups such as the Sama and the Yakan, occupy areas across the Sulu Archipelago and some parts of the Zamboanga Peninsula (Frake, Reference Frake1998). The Maguindanao (Magindanw'n) people thrived in the riverine plains of the Cotabato region, covering the present day Maguindanao and North Cotabato provinces, while the Maranao (M'ranaw) lived in areas surrounding Lake Lanao and the coastal areas of the Lanao provinces. A Maguindanao Sultanate had arisen along the downstream banks of the Pulangi, the main river in Cotabato, in the 17th century but soon declined afterwards (Warren, Reference Warren2002). The decimation of the Maguindanao Sultanate paved the way for the rise of a Sulu Sultanate with Tausug speakers as the core of its leadership in the 18th century until its disintegration two centuries later following U.S. occupation of the Philippines (Warren, Reference Warren1981). In the run-up to the Philippine nation-state building following the country's independence in 1946, the clear-cut tribal dividing lines of these ethnolinguistic groups have softened due to intermarriages and migration to each other's communities and the formalised national education introduced by the government, even as they largely retained their respective ancestral languages, lands, and sense of identification to their genealogical roots.

The actual emergence of current secessionist forces, however, can be tracked back to the rise of the Mindanao Independence Movement (MIM) in Cotabato in the 1960s (McKenna, Reference McKenna1998). Udtog Matalam and Salipada Pendatun organised the MIM when communal violence began spreading, pitting Muslim and Christian communities in the region (McKenna, Reference McKenna1998). Events unfolded in the midst of growing Muslim social actions in Manila and elsewhere over deepening poverty, dislocation, underdevelopment, and increasing cases of unsolved killings across the Muslim enclaves of Mindanao.

MIM lasted a few years after Matalam and other leaders secured deals with the Marcos government to end the fighting and earned political posts in the dictatorship (Lucman, Reference Lucman2000). The movement's demise, however, unleashed sentiments for secession by restive Muslim students and intellectuals. The youth of the MIM transformed the group into a fiercer and better organised Moro National Liberation Front, with Nur Misuari as chair and Salamat Hashim as his deputy in 1972 (Jubair, Reference Jubair1999). Under the banner of the MNLF, Misuari, Hashim, and their followers fashioned the Moro struggle in the likeness of the growing nationalist movements elsewhere in the Middle East (McKenna, Reference McKenna1998). In articulating the idea of a Moro nation, the movement imagined Morohood as a collective identity of 13 Islamised ethnic communities across the Southern Philippine region of Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan islands (Jubair, Reference Jubair1999).

Eventually, though, under the auspices of the Islamic Conference of Foreign Ministers, the precursor of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, the MNLF negotiated peace with the Marcos regime and sealed a deal in 1976 in Tripoli, Libya (Majul, Reference Majul1985). The deal was clinched after the MNLF refined their demands from secession to autonomy for a few provinces in Mindanao and Sulu. Shortly after, however, the deal collapsed over sharp disagreement with the central government's insistence on holding a referendum before delivering its commitment of implementing the accord (Delos Santos, Reference Delos Santos1986). The government unilaterally went ahead with the plebiscite, prompting the MNLF to resume fighting for an independent Bangsamoro state but under a radically changed organisational circumstance. Immediately following the peace accord, fissures shook the MNLF leadership, which led Hashim to break off and form the MILF in the 1980s (Gowing, Reference Gowing1988; Mastura, Reference Mastura1984).

On the surface, the fragmentation appears to follow ethnic fault lines, given that the secessionist movement itself built up the idea of the Moro as constituted by diverse Islamised communities and that their leaders are closely associated with their ethnic origins, with Misuari being a Sama-Tausug native from Sulu and Hashim a Maguindanao from Central Mindanao (Bertrand, Reference Bertrand2000; Buendia, Reference Buendia2005; Frake, Reference Frake1998; Montiel et al., Reference Montiel, de Guzman and Macapagal2012). Some commentators went as far as arguing that the idea of the ‘Bangsamoro . . . unifies the various Moro groups only to a small degree. It is relevant politically in order to be heard by the Philippine government or the international donor community . . . In terms of content, the bands are weak, the Muslims see themselves as members of their clans and ethnic group, and only secondary as Muslims’ (Kreuzer, Reference Kreuzer2005, p. 22). They underscore the ethnic dimensions of the Mindanao conflict but in a manner that underplays the broader relations permeating its secessionist politics.

Dissecting the realignments of the subjective forces of secessionism in Mindanao following its many episodes of splintering, however, suggests an even more complex configuration wherein association by ethnicities, religion, and political interests converge and overlap even while they also disconnect. The MILF subsequently built a core leadership run by the ulama, with Hashim as simultaneously chief cleric and amirul (leader) of the movement (Gutierrez, Reference Gutierrez, Gaerlan and Stakovitch1999). The group expanded and gained widespread following in Central Mindanao, a Maguindanao and Maranao populated region. In contrast, the MNLF thrived through a system of territorial revolutionary committees led primarily by secular military and political strategists or traditional village leaders, even as it continued to concentrate on community organising and military work in enclaves populated by different Islamised ethnic communities (Mastura, Reference Mastura1984). At the helm of the MNLF leadership was Misuari, an ethnic Sama-Tausug political science professor. Nonetheless, when the MNLF further split apart in the 2000s, Misuari's loyal armed following narrowed down to specific villages of Sulu and Basilan provinces in the Sulu archipelago, reflecting in part the ethnic contours pointed earlier (Torres, Reference Torres2014; Canuday, Reference Canuday and Torres2014).

The foregoing discussion illustrates the tangled relationships of ethno-politics and religion in Mindanao. While fundamentally unified in imagining an independent Bangsamoro and a shared Moro identity for all of the region's Muslim communities, competing movements have mobilised and integrated, or were forced to contend with ethnopolitical and religious forces as they positioned themselves in the contested political environment of the periphery. These processes, however, leave the question of how communities in whose name Bangsamoro independence is fought have come to accept or reject, associate or dissociate themselves from such an agenda. In what ways are religious and ethno-political identities becoming inclusive in the context of the Bangsamoro question? In what ways do they intersect and overlap?

Overlapping Social Identities

Are religious and ethnopolitical identities mutually exclusive during social conflicts? On a theoretical plane, it may be easy to disentangle religious and ethnic identities, because each type of social identity is marked by its own set of characteristics. For example, during conflict, the emergence of ethnic identities inspires political talk about group territorial rights and social recognition of the marginalised group. On the other hand, the rise of religious identities triggers proselytisation and the unpacking of the social conflict along the language of one's religion. Further, the recent rise of political cyber-communication has made a religious narrative rather than an ethnic storyline more likely to facilitate widespread support among like-faithed groups globally.

But, on the ground, religious and ethnic identities are more difficult to distinguish and may not be mutually exclusive. During territorial conflict, both types of social identities arise side by side with each other because territorial spaces of conflicting groups likewise mark the faultlines along which ethnic groups and religions divide. For example, the Bosnia-Croatia-Serbia conflict in the former Yugoslavia was divided along Muslim-Catholic-Orthodox lines (Powers, Reference Powers1996), and the ongoing Tamil-Sinhalese conflict in Sri Lanka is also a conflict between Christians and Buddhists (DeVotta & Stone, Reference DeVotta and Stone2008).

It is possible for ethnic social identities to overlap under conditions when common ingroup identity does not demand forswearing subordinate ethnopolitical identity (i.e., being Tausug, Maguindanaon or Maranao). In this premise, it is possible to think about persons pursuing multiple identities. This is particularly important in societies with sustained ethnic conflict where it may be challenging to abandon one's original group membership (Gaertner, Dovidio, & Bachman, Reference Gaertner, Dovidio and Bachman1996).

Moreover, conditions marked by violent ethnopolitical conflicts can motivate people to adopt two or more strategic socio-political identities that place them in a position to express their inclusion in a broader formation, as well as the distinctiveness of their immediate ethnic and cultural affiliation (Brewer, Reference Brewer1991). Minority motivation to associate with a superordinate identity loses importance when a favourable socio-political condition emerges. One way of dealing with such a circumstance is to understand the political conditions that made it important for an ethnic minority to maintain more than one strategic ethnopolitical identity. On this premise, this article proceeds with the examination of overlapping subgroup or ethnic social identities and common in-group or superordinate (Bangsamoro) social identities. Overlapping social identities refers to the superordinate identity similarity, which is whether they perceive their ethnopolitical social identity as intersecting with the emerging superordinate Bangsamoro identity.

The Bangsamoro Identity: An Emerging Superordinate Identity

Having overlapping social identities suggests that it is possible for the conflicting ethnopolitical groups to accept a superordinate social identity. Based on the common ingroup identity model developed by Gaertner and Dovidio (Reference Gaertner and Dovidio2000) to account for the dynamics of intergroup contact, previously distinctive groups on some occasions recategorise themselves into a singular group welded together by a superordinate identity. If the secessionist discourse of historic political and cultural amalgamation of Islamised ethnic identities of Mindanao holds, the Tausugs, Maguinanaoans and Maranaos should see themselves as constituents of emerging superordinate identity, which this study regards as an ethnopolitical Bangsamoro form of identification.

While identification to a superordinate identity potentially ameliorates intergroup solidarity, such an outcome nonetheless hinges on knowing how an individual attitude develops toward a particular superordinate identity within a given political context (McKeown, Reference McKeown2014). Given the tenuousness of individual identification to intergroup solidarity, it is also possible to find variances in the degree to which people who regard themselves as Tausug, Maguindanaon and Maranao associate with a Bangsamoro superordinate identity. In this study, we investigated the attitude and the extent of identification of Tausug, Maranao and Maguindanaon ethnopolitical constituencies to the Bangsamoro as a shared national identity.

Accepting a superordinate identity may be challenging in societies with salient ethnic categorisations (Hewstone, Rubin, & Willis, Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002). Historically competing groups and minorities are likely to resist what they see as assimilation into a superordinate category dominated by a majority ethnic formation, or in the Bangsamoro case, a politically dominant outgroup (Hewstone et al., Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002). In this situation, it is possible to imagine a superordinate identity being regarded as a threat, in particular by a low status group that harbours fears of the superordinate identity undermining subordinate constituency (Saguy, Dovidio, & Pratto, Reference Saguy, Dovidio and Pratt2008). In the context of the Bangsamoro peace talks, armed formations with strongholds in Maguindanao province and its proximate areas underpinned the leadership of the MILF. MILF leaders, whose armed base hails mainly from areas predominantly populated by Maguindanaon speakers, set the terms of the negotiations with the government and claim to represent the broader interest of the Bangsamoro people. The MNLF, the competing secessionist force with strongholds in the Tausug-predominated areas of Sulu, have found themselves precluded from the government and MILF negotiations. ARMM constituents in areas with stronger allegiances to the MNLF are within the low status group. In this case, the negotiations for the 2014 Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro left behind the constituencies of Sulu, a predominantly Tausug-speaking area. In this connection, we posit that the attitude of the respondents from Tausug-predominated areas of Sulu would hold a degree of connection towards a Bangsamoro superordinate identity.

Research Objectives

The present study aims to examine the different social identities in Muslims in Mindanao, particularly their religious and ethnopolitical identities. We also examine the possible overlap between the Muslim's ethnic/tribal identity and the emerging superordinate Bangsamoro identity. As past literature has suggested, having overlapping identities is possible and even particularly important in societies with sustained ethnic conflict, where it may be challenging to abandon one's original group membership. Finally, we posit that the low status group in the peace talks, the Tausugs, will have less overlap with the emerging Bangsamoro identity compared to Maguindanaon and Maranao ethnic tribes. Moreover, the Tausugs will have less favourable acceptance of the emerging superordinate Bangsamoro identity, having been excluded in the recent peace talks and Agreement on the Bangsamoro.

Method

Sample

Our survey included 394 residents from selected political centres of the ARMM (autonomous region), specifically the cities of Jolo (n = 157), Cotabato (n = 151), and Marawi (n = 89). In terms of gender distribution, about 53% of the respondents of the study were females and 47% males, with a mean age of 32.6 years old and standard deviation of 13.3 years.

The minimum sample size required to conduct the statistical analysis (i.e., t test and ANOVA) for a Cronbach's alpha of .05 and 90% power is set at 67 (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988). Moreover, our sample distribution takes into account the population sizes of three of the largest Islamised ethnopolitical groups in the autonomous region that observers often cite as the more dominant Bangsamoro constituencies in Mindanao (Kamlian, Reference Kamlian2003; National Statistics Office, 2002; Tan, Reference Tan1993). Our sample considers these broader population variations by proportionately assigning Tausug and Maguindanaon speaking groups the greater number of respondents, being the more populous ethnopolitical formation among the Bangsamoro constituencies. This proportion also takes into account that the armed bases of the main Mindanao secessionist formations are located mainly in provinces where both ethnopolitical groups predominate. As discussed above, critical areas of Tausug-predominated Sulu served as the citadel of an MNLF faction while strategic parts of Maguindanoan-dominated Maguindanao province have been reported as an MILF stronghold (Kreuzer, Reference Kreuzer2005). Furthermore, we factored Maranao-speaking respondents into the study on the premise that they are often regarded as a major Muslim ethnic ‘tribe’ (Kamlian, Reference Kamlian2003).

Local researchers from colleges and universities in these three areas recruited respondents from varied social classes and occupations (e.g., teacher, student, government employee, businessman, driver, soldier, nurse, social worker). The respondents were categorised into the three ethnopolitical groups based on self-report. All respondents extended their informed consent and were assured of confidentiality and anonymity.

Measures

Respondents from the three sites were asked to reply to a series of questions concerning their beliefs, thoughts, and feelings about themselves and their ethnic tribe, religion, and Bangsamoro. Specifically, they answered the following three measures:

Social identity scales

Many social scientists have relied on multi-item scales to measure social identity (Huddy, Reference Huddy, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013). As such, to measure the respondents’ salience of identification with their ethnopolitical ingroup (Tausug, Maguindanaon, or Maranao) and religion (Muslim), we adapted Cameron's (Reference Cameron2004) scale of social identification. Respondents were asked to rate on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) on nine items for the ethnic identity. Sample items include: ‘I often think about being [Tausug, Maranao or Maguindanaon]’; ‘I often regret being a [Tausug, Maranao or Maguindanaon]’; ‘I don't feel a strong sense of being connected to [Tausugs, Maranaos or Maguindanaons]’. A similar scale for Muslim identity was used with 10 items (e.g., ‘I often think about being a Muslim’; ‘I often regret being a Muslim’; ‘I don't feel a strong sense of being connected to Muslims’).

A high score on the scales indicates strong identification with their ethnopolitical or Muslim identity. Both scales are highly reliable (α = .81 for ethnic identity and .75 for Muslim identity). An array of studies on intergroup behaviours and ethnic identity use the same scale, which is known to be a valid measure of social identification (McKeown, Reference McKeown2014; Obst, White, Mavor, & Baker, Reference Obst, White, Mavor and Baker2011).

Attitude towards Bangsamoro superordinate identity

To determine the extent to which respondents associate the Bangsamoro as an identity that they can easily adopt, a four-item, 5-point Likert scale was used with the following items: (1) ‘I would feel happy belonging to one Bangsamoro’; (2) ‘All Tausugs/Maguindanaon/Maranaos would be happy belonging to one Bangsamoro’; (3) ‘A single Bangsamoro identity is an identity that I could personally accept’; (4) ‘A Bangsamoro identity is an identity that all Tausugs/Maguindanaons/Maranaos could accept’. The scale was patterned after McKeown's (Reference McKeown2014) superordinate inclusion scale and was found to be reliable (α = .91) and valid, with the four items loading onto a single factor accounting for 79% of the variance.

Overlapping ethnic and Bangsamoro identities

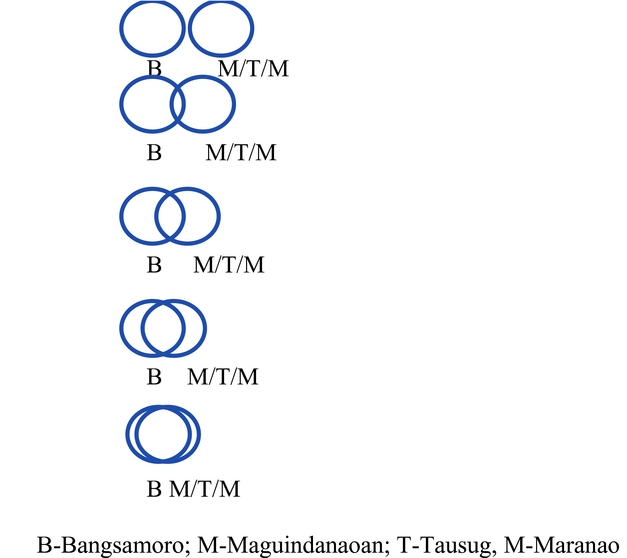

To determine whether the Bangsamoro identity is perceived as being similar to or intersecting with their ethnopolitical social identity, participants were asked to rate the extent to which they felt Bangsamoro and Tausug/Maguindanaon/Maranao identities overlapped. This followed the inclusion of self-in-other approach of Aron, Aron, and Smollan (Reference Aron, Aron and Smollan1992) by using Venn diagrams (see Figure 1). The more the circles overlapped (numbered 1 to 5), the more similar the identities of their ethnic group and the emerging superordinate Bangsamoro identity were perceived.

Figure 1 Venn diagram of overlapping ethnic and Bangsamoro identities

All the instruments were translated to the local dialect, but the English translations were retained. Moreover, our survey instrument also ran an open-ended item that asked: ‘What does Bangsamoro mean to you?’

Results

A paired samples t test was conducted to compare the ethnic identity and Muslim identity salience of the respondents. A series of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was also conducted to compare the ethnic and religious identity saliences scores, overlap between ethnic and Bangsamoro identity scores, and attitude towards Bangsamoro identity across the three ethnic tribes.

Social Identity of Muslims in Mindanao

Our sampled respondents identified rather strongly with both their Muslim and ethnopolitical identities, as evidenced by mean scores closer to the highest possible rate of 5. The results showed that Muslims do identify themselves more strongly with their religious or Muslim identity (M = 4.41) compared to their own ethnic group (M = 4.16), t(393) = -9.04, p = .00. In comparing the ethnic groups, the Tausugs have a significantly more salient Muslim identity (M = 4.49) compared to Maguindanaoans (M = 4.30), F(2,392) = 4.50, p = .01. Common to all three groups is the lack of significant differences in ethnic identity scores among Tausugs, Maguinandaoans, and Maranaos, F(2,392) = 1.00, p =.36. In other words, respondents from the three ethnopolitical groups share the same ethnopolitical identity salience (refer to Table 1 for the mean scores per ethnic group).

Table 1 Mean and Standard Deviation Scores for Ethnic and Muslim Identity Salience Across Ethnopolitical Groups

High positive correlations between their ethnic and Muslim identities were also obtained for the three groups, with Maranaons and Maguindanaons having similar correlations (r = .63 and r = .64) but the Tausugs having the lowest correlation (r = .55). See Table 2.

Table 2 Correlations Between Muslim Identity, Ethnic Identity and Bangsamoro

Note: Pearson r is significant, p = .00.

Overlapping Social Identities

The mean overlap scores of the respondents was 3.52 (out of 5), suggesting a moderately high intersection between their own ethnic identity and the emerging superordinate Bangsamoro identity. There was a significant difference of overlapping social identities between the Tausugs (M = 3.00) and Maguindanaons (M = 4.05) at p = .00. Maguindanaons showed the most overlap of social identities. As expected, the Tausugs showed the least similarity between their own ethnic identity and the Bangsamoro identity (Table 3).

Table 3 Overlapping Identity Mean Scores per Ethnopolitical Group

The correlations in Table 2 also reveal that ethnic identity was significantly correlated with their attitudes toward the Bangsamoro identity (r = .27, p = .00).

Ethnic Differences and Attitudes towards Bangsamoro Identity

The Muslims in our sample showed generally favourable attitudes toward the emerging superordinate Bangsamoro identity, with an overall mean score of 3.81 out of 5 (Table 4) . A significant difference was found between the attitudes of Tausugs (M = 3.34) and Maguindanaoans (M = 4.16), with F(2,386) = 34.74, p = .00, but not between the other ethnic groups.

Table 4 Attitude Toward an Emerging Superordinate Identity Per Ethnopolitical Group

We also correlated Muslims’ ethnic identity, their Muslim identity, and attitudes toward the Bangsamoro identity. It is interesting to note that only the Maranaos did not have a significant correlation between their Muslim and Bangsamoro attitudes (r = .18) as well as their ethnic and Bansamoro attitudes (r = .16). It is the Maguindanaons who have the strongest link between their Muslim identity and acceptance of the Bangsamoro identity with r = .51 (see Table 2). These differences in correlations reveal that the ethnopolitical groups do not perceive the compatibility between their Muslim and overarching Bangsamoro identity equally.

Ethnopolitical Group and Bangsamoro Identity

On the question of which ethnopolitical affiliation they think the Bangsamoro identity today is mostly associated with, the majority (57%) said all Islamised groups in Mindanao, indicative of their openness to include all ethnopolitical formations in the Bangsamoro identity. However, there are quite a number who still think that certain ethnopolitical groups are more associated with the Bangsamoro identity: 23% regard themselves as Maguindanaoan, 12% see themselves Tausugs, and 5% identify themselves as Maranaos (Table 5.)

Table 5 ‘I think the Bangsamoro identity is mostly associated with . . .’

Segregating the data according to ethnopolitical groups, it can be seen in Table 6 that one's own ethnic group is still associated with the emerging superordinate Bangsamoro identity.

Table 6 Responses to ‘I think the Bangsamoro identity is mostly associated with . . .’ According to Ethnopolitical Group

Note: Chi square is significant, df = 8, 157, p = .00.

Meaning of Bangsamoro

In constructing the subjective meaning of the term Bangsamoro, our survey instrument also ran an open-ended item that asked: ‘What does Bangsamoro mean to you?’ We avoided precoding responses to this item in order to tap the broad spectrum of subjective understandings of this crucial term.

Our data analysis relied on quantifying qualitative text through text mining procedures. We investigated the words paired or uttered together with Bangsamoro. We then calculated for weights or how often each word-Bangsamoro pair appeared together. The higher the weight, the more the word was associated with the term Bangsamoro. For example if the word pair Mindanao-Bangsamoro obtained a weight of 58, this meant that the word Mindanao appeared 58 times in the same response as the word Bangsamoro. Table 7 presents the top five (5) words associated with Bangsamoro, ranked from highest to lowest weights.

Table 7 ‘What does Bangsamoro mean to you?’ Top Five Words Associated with Bangsamoro

Word association calculation is akin to taking a picture of the ideas linked with the concept of Bangsamoro. The procedure enjoys the benefits of mixing qualitative data with quantitative procedures. By avoiding precoded responses, the instrument avoids priming the respondent with a set of predefined choices. Allowed to speak freely, the respondent creates his or her own unadulterated reply to a question about subjective meaning. On the other hand, quantitative analyses were imposed on the lexical responses in order to control for the interpretative gap, as researchers interpret open-ended prose. More specifically, computations of word association weights — rather than some kind of thematic analysis — showed which words contributed to the meaning of Bangsamoro, with the accuracy and precision of mathematical calculations.

Our findings in Table 7 show that Bangsamoro means a fusion of Mindanao, Muslim/Islam, and peace/unity. Examples of these texts include ‘Bangsamoro is the coming together of the tribes towards peace and progress of Mindanao’ (from a Maranoan); ‘People with different ethnic groups but with the same faith to Islam unite together to form a bond between each other in order to influence peace and harmony’ (from a Maguindanaon); and ‘Bangsamoro is the coming together of Tausug with the desire to be united for the entirety of the Islam religion’ (from a Tausug). Hence, this pivotal term possesses features that define it geographically, ethnically, and procedurally. In summary, Bangsamoro means bringing peace to Muslim Mindanao. While the calculated weights specify what Bangsamoro implies, one can stretch the findings further and likewise define what Bangsamoro excludes, semantically or meaningfully. Our research results show that Bangsamoro is not about the entire Philippine archipelago, nor does it include Christians; and it is an antidote to war and divisions.

Discussion

The objective of this research was to look into the religious, ethnic, and emerging superordinate identity that is the Bangsamoro identity of Muslims in Mindanao in the southern Philippines. The present study is the first to examine such perceptions of this new and emerging identity and how acceptable this identity will be among Muslims in Mindanao. We compared the ethnic and religious social identities of the Muslims to examine which was more salient. We also looked at how their ethnic identity influenced their perceived overlap of ethnic and Bangsamoro identities and consequently their acceptance of this emerging identity.

Social Identity of Muslims in Mindanao

Results of this particular survey did not exactly resonate with at least two streams of widely cited assessments of Muslim identity issues in Mindanao. They do not reflect narratives that Muslim communities identify themselves rather strongly with their ethnic sense of connection shaped by broadly extended kindred relations, more than their religious conviction (Frake, Reference Frake1998; Kreuzer, Reference Kreuzer2005). Moreover, they do not fully support assertions of a Muslim ethnopolitical formations congealing toward an Islamic political consciousness that emerged out of a long historic struggle to defend Islam against colonial and postcolonial aggressions (Laiq, Reference Laiq1988; Macasalong, Reference Macasalong2014; Rabasa, Reference Rabasa2003). Instead, the responses gathered in this study suggest yet another understanding of identity of a Mindanao Muslim constituency that does not cast Islam as a secondary element to family or ethnopolitical affiliation imagination but rather is the essence of it. This constituency identifies themselves rather strongly with conviction to Islam, but not necessarily as a basis for an ethnopolitical identity assertion. To some extent, this finding resonates with broader observations of shifting terms of solidarity, from unfettered allegiance to ethnicity or the nation toward stronger adherence to religion, particularly of Islam and its sacred texts, in dealing with extraneous structural forces in several other contexts of separatist struggles (Ghanem & Mustafa, Reference Ghanem and Mustafa2014; Yemelianova, Reference Yemelianova2014). The responses from our respondents in Mindanao align with observations of deepening connections to Islam as a significantly important component of individual and collective identity, rooted in an idea that speaks about the oneness of faith (Foley, Reference Foley2008). Our study shows that the salience of their religious identity may be a unifying factor in a conflict-ridden context in Mindanao.

Overlapping Social Identities

Consistent with our hypothesis, responses from our survey show a moderately high overlap of individual allegiance to their own ethnic identity and the emerging Bangsamoro superordinate identity. These responses suggest that native ethnopolitical and the Bangsamoro superordinate identities are not mutually exclusive. On the contrary, association with the superordinate identity is buttressed by even stronger attachment to local ethnic identity. In this case, our respondents retained their salient ethnic identity (i.e., being Tausug, Maguindanaon, or Maranao). They did not abandon their original ethnic membership but maintained identification to both identities, possibly motivated by their need for the inclusion of both into the new superordinate identity (Brewer, Reference Brewer1991).

Moreover, as expected, Tausug respondents showed the least association between their own ethnic identity and the Bangsamoro. This finding tells us that the low status ethnic group among the three ethnopolitical groups included in this study takes a more critical, and to some extent cautious, approach in assimilating with the new superordinate identity, the Bangsamoro, which is more associated with the competing ethnopolitical group. These results concur with previous literature, which stated that historically competing groups are likely to resist what they see as assimilation into a superordinate category that is dominated by a politically dominant outgroup (Hewstone et al., Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002).

Ethnic Differences and Attitude Towards Bangsamoro Identity

From our sampled respondents, on the one hand we point to generally favourable attitudes toward the emerging superordinate Bangsamoro identity. On the other hand, the contours of ethnopolitical relations are evident, as indicated by the ambivalence of the Tausug-speaking respondents in our sample in accepting the Bangsamoro identity. Other respondents associate the Bangsamoro identity with their own ethnic formation rather than the reverse.

Conclusion and Implications for Peacebuilding and Further Research

The findings of the current research suggest how religious identity provides a unified sense of belonging and serves as a unifying element in the conflict-ridden context of the Southern island of Mindanao in the Philippines. What ethnic identity fragments, religious identity unifies. The Muslims in our study strongly identified with their Muslim identity, significantly more than their own ethnopolitical or tribal identity. Moreover, the current research studied a new superordinate identity, the Bangsamoro identity. Our findings show that it is indeed an acceptable identity for the Muslims in Mindanao. As McKeown (Reference McKeown2014) has pointed out, adopting a superordinate identity does not necessarily mean that people must abandon their subgroup identity. A dual identity may be a more realistic option.

By understanding ethnopolitical and religious social identities and perceptions of a superordinate identity (in this case, the Bangsamoro), it is possible to examine whether this social identity can lead to improved intergroup relations and further the cause of peacebuilding, especially for Mindanao. Our research offers suggestions toward making the Bangsamoro identity a workable solution acceptable to Mindanao Muslims, regardless of their ethnic origins. Understanding is part of the key to actualising the dream of achieving peace in Mindanao. The examination of how Muslims perceive the emerging Bangsamoro identity reveals to us a psychological diversity even among Islamised ethnopolitical groups in Mindanao. This poses a challenge, but more importantly a possible solution to the dilemma facing the Mindanao peace process. Finding a way to build a superordinate Bangsamoro social identity that all Islamised Moro ethnic groups can identify with is crucial to establishing a common Moro front in the Mindanao peace process.

Our results also show how identities are dynamic and context-dependent. Negotiators may want to determine the groups they are dealing with. For example, when dealing with a high-power group, a low-power group may want to highlight religious identities to present a more unified front. In the context of peace agreements, ethnopolitical countours may become more salient when one group appears to take the lead vis-à-vis another group. Overlapping social identities may also influence support for, and participation in, various peacebuilding initiatives.

The politics in Mindanao goes beyond Muslim-Christian relations in the Philippines. Power plays among ethnopolitical formations affect the way these Islamised Muslim groups accept the emerging Bangsamoro identity. Reconciling the different Moro subgroups may pave the way to smoother Muslim-Christian peace negotiations. Appealing to the superordinate identity of Bangsamoro in order to reach a common standpoint between the ethnopolitical groups may prove helpful in the creation of a united Moro front during Mindanao peacebuilding. Thus, peacebuilding efforts must continue to crystallise the unifying function of religious identity and seek to transcend ethnic divisiveness.

Limitations of the Study and Future Directions: Bangsamoro in the Midst of Globalisation

Our study examined the meaning of Bangsamoro, a word coined from one's sense of being a Filipino Muslim. This article elucidated the religious dimension of Bangsamoro, emphasising the importance of one's Islamic identity as distinct from the Christian identity of other Mindanaoans. By some unexpected historical twist, however, and as we write this paper, another threat has emerged to the Bangsamoro identity. As of this writing, a Muslim-dominated city in Mindanao is undergoing an intense city-wide ground and aerial war, due to the emergence of ISIS forces in the area. Armed attacks include forces of foreign Islamic fighters, in the name of a global Islamic cause.

One primary research limitation lies in the study's sole focus on the Muslim dimension of Bangsamoro and its failure to interrogate the national Filipino identity of a Filipino Muslim. The question for future studies may likewise ask: What is a Filipino Muslim identity, as distinct from a non-Filipino or global Muslim identity? Understandably, such a question has not been asked before, perhaps because Mindanao has not been under siege by foreign Islamic forces in the past. New historical developments place upon the research community new identity issues that arise with the globalisation of a religiously coloured war.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ateneo de Manila Institute of Philippine Culture Merit Research Award. Dr Macapagal and Dr Canuday would also like to thank the Ateneo de Manila School of Social Sciences for the research load. The authors wish to thank Miguel Karlo Abadines, Arvin Boller, Dr Alma Berowa of Mindanao State University-Marawi City, Janice Jalili of Notre Dame in Jolo, Sulu, and Dr Ma. Theresa P. Llano and the University Research Center of Notre Dame University in Cotabato City.