When campaigning for Congress in 1866, Congressman Hiester Clymer ran a now-infamous campaign advertisement that depicted a minstrelised Black man daydreaming of receiving Freedmen’s Bureau appropriations, while White men toil to pay the taxes which would fund those appropriations. The headline of the advertisement reads, “The Freedman’s Bureau! An agency to keep the negro in idleness at the expense of the White man.” The Freedmen’s Bureau, officially titled the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, existed from March 1865 to June 1872 to provide relief to newly freed persons and to help them become self-sufficient, among other duties (Foner Reference Foner2013). As such, the Bureau represented an early incarnation of social welfare aimed at poverty reduction, with later examples being state mothers’ pensions, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), and more recently, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), which replaced AFDC in 1996 under the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA). This Act aimed to make good on President Bill Clinton’s promise to “end welfare as we know it.”

While neither AFDC nor TANF were or are explicitly race-based, race is a defining feature of both programmes in Americans’ collective conscience, similar to early impressions of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Built into this racialisation – both historically (Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981; Tonry Reference Tonry2010) and more recently (Foster Reference Foster2008; DeSante Reference DeSante2013) – is the notion that White populations in the United States (US) face extraction from the welfare state. Such notions inflate stigmas surrounding Black welfare recipients as inherently untrustworthy, criminal, and immoral (e.g. Nadasen Reference Nadasen2007), which may inform how funds are allocated (e.g. Hardy et al. Reference Hardy, Samudra and Davis2019; Parolin Reference Parolin2021).

Consequently, there may be a historical thread connecting these assistance-providing programmes through the construction of their target populations (Kandaswamy Reference Kandaswamy2021), or those at whom the programmes are aimed (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993). We interrogate this, questioning whether areas that had a stronger Freedmen’s Bureau presence allocate TANF funds differently today than those states either not eligible to house field offices or with fewer. In a broader sense, we question whether prior policies, institutions, and constructions of target populations inform policy and policy implementation today in a form of path dependency. Central to this idea is the proposal that earlier events tend to shape policy trajectories much more than later ones (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2000; Pierson Reference Pierson2000), and as institutions and practices become entrenched, changing pathways becomes increasingly difficult. This appears to be especially true within the domain of welfare policy, as Pierson (Reference Pierson1996) describes. Therefore, as one of the US’s oldest institutions of social assistance, the Freedmen’s Bureau may be a foundational source of policy information for contemporary and future welfare state development. In this sense, the period of Reconstruction in which the Bureau emerged represents a critical juncture in the trajectory of the American welfare state, and such junctures are known to set institutions down self-reinforcing paths which are not easily veered from (Pierson Reference Pierson2011). Scholars such as Byman (Reference Byman2021) have similarly identified this period as a critical juncture in the development of structural racism in the US.

Our contemporary policy of interest, TANF, is a federalised, conditional cash-transfer programme whereby the federal government provides a fixed, 16.5 billion dollar block grant to states, which states then allocate among up to 20 different broad categories, largely as they choose. This decentralised design differs from TANF’s predecessor programme, AFDC, which gave substantially less latitude to the states. To receive the full federal TANF block grant, states are required to engage in “maintenance of effort,” which can be met through the implementation of new programming or by counting programming already in implementation. As a consequence of the shift from entitlement programme to the TANF block grant, states can shift basic, cash assistance to a variety of other uses as long as those uses conform to TANF’s statutory goals: “(1) provide assistance to needy families so that children may remain in their homes; (2) end the dependence of needy parents on government benefits through work, job preparation, and marriage; (3) reduce out-of-wedlock pregnancies; and (4) promote the formation and maintenance of two-parent families” (Congressional Research Service 2022).

We suggest that state-level allocation decisions under TANF can be traced to the historical origins of the US welfare state: The Freedmen’s Bureau. As a welfare institution that was (inaccurately) perceived by many to serve (Black) freedpeople at the expense of White communities (Bethel Reference Bethel1948; May Reference May and Thomas1973; Foner Reference Foner2013), the Bureau established a foundation upon which future iterations of social welfare programmes were built, carrying with it the same narratives concerning the construction of the target population of those programmes. This paved the way for the future design of associated programmes and future attitudes surrounding race and welfare in the states where it operated, thus exacerbating the racial inequities that inhere in the American federalist structure (Riker Reference Riker1964; Katz Reference Katz1993; Kettl Reference Kettl2020). We expect that states with a higher historical rate of Freedmen’s Bureau field offices will: (1) allocate more spending towards programmes that aim to correct perceived behavioural deficiencies, such as having children out-of-wedlock or the failure to maintain two-parent households and nonparticipation in labour markets (Coercive Allocation Hypothesis); and (2) allocate less spending towards programmes that explicitly confer benefits to recipients, such as cash assistance (Cash Allocation Hypothesis).

To test these expectations, we build a unique data set using a range of sources, including information on the rate of Freedmen’s Bureau field offices per 100,000 Black residents by state (Rogowski Reference Rogowski2018) and proportional TANF allocations for two types of programmes: those (1) aimed at coercing participants to adhere to traditional family structures and incentivising work and (2) providing basic cash assistance. Even when controlling for historical and contemporary covariates, we find that states with a higher historical rate of Freedmen’s Bureau field offices are linked to more TANF funding for coercive programmes on average. However, we do not find a relationship between the prevalence of Freedmen’s Bureau field offices and the proportion spent on basic assistance programmes. On balance, these results support the proposal that historical institutions impact modern policy in discernible, albeit limited, ways.

Our work builds on robust histories and qualitative work to show evidence that 150-year-old policies and their accompanying social constructions of target populations resonate in modern America, joining the growing literature empirically testing such connections (e.g. Acharya et al. Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016; Mazumder Reference Mazumder2018; Shoub Reference Shoub2022). Our findings suggest that stereotypes and norms, once established, may be exceedingly difficult to break, as such attitudes and constructions are passed down both informally, such as through learning from elders and bosses, and formally, such as through formal policies.

In doing so, this study extends our understanding of how historical policy and institutions relate to policy design and implementation today by highlighting the role historical definitions of target populations may play in bringing policy histories (e.g. Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981; Tonry Reference Tonry2010) into conversations with theories of policy process (e.g. Moynihan and Soss Reference Moynihan and Soss2014; Mettler Reference Mettler2016). Further, this study underscores and complements prior work on the racialised nature of social welfare in the US (Wright Reference Wright1977; Quadagno Reference Quadagno1994; Gilens Reference Gilens1996, Reference Gilens2009; Schram et al. Reference Schram, Soss, Fording and Houser2009). Finally, this work highlights how the roots of the modern American welfare state extend beyond perceived New Deal/Great Society origins to much earlier implemented policies – thinking encouraged by scholars such as Howard (Reference Howard, Mettler, Valelly and Lieberman2016) and Skocpol (Reference Skocpol1995) – and reinforces arguments that social welfare programmes can, at times, function as mechanisms for social control of the poor (e.g. Piven and Cloward Reference Piven and Cloward2012; Kandaswamy Reference Kandaswamy2021). In short, this article indicates that the disparities we see in contemporary, state-level TANF administrative choices – and the degree to which they are punitive – represent one of the lasting legacies of prior policy, at least in part. This raises equity concerns today and questions about how best to address disparities.

Historical institutions to today’s policy

Not only does “policy beget politics,” but it also begets future policy by informing and shaping institutions (e.g. Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1935; Lowi Reference Lowi1964; Moynihan and Soss Reference Moynihan and Soss2014), as no policy is introduced and implemented in a vacuum. Rather, it comes to be in a policyscape already structured by prior policies and institutions, such that what comes next either intentionally or unintentionally incorporates what came before – or directly confronts it (Mettler Reference Mettler2016). Prior studies have shown this with respect to historical institutional design and purpose (Knill Reference Knill2001; Yesilkagit and Christensen Reference Yesilkagit and Christensen2010; Shoub Reference Shoub2022), as institutions have been more broadly shown to shape outcomes and behaviour of those operating within them, such as members of Congress (e.g. Jackman Reference Jackman2014), executives (e.g. Krause and Melusky Reference Krause and Melusky2012), and street-level bureaucrats (e.g. Whitford Reference Whitford2002). This has also been seen regarding policy and policy outcomes as they stem from institutional design and often inaction in changing policy (e.g. Mettler Reference Mettler2016; Shoub Reference Shoub2022). Here, we contend that historical institutions may be able to guide contemporary policy, not only through the inheritance of design, structures and, goals, but also through the establishment and reinforcement of norms – specifically the definitions of target populations.

The intuition behind how the definition of target populations relate to policy design is that policy should deliver benefits to favourably viewed groups and burdens to disfavoured groups. The identification and definition of target populations are socially constructed and fundamentally rely on evaluations of group power (strong or weak) and valence (positive or negative image). Schneider and Ingram (Reference Schneider and Ingram1993) articulated this theory, while others have since quantitatively tested it (e.g. Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, De Boef and Boydstun2008; Rose and Baumgartner Reference Rose and Baumgartner2013), such as Boushey (Reference Boushey2016) who shows that when the target populations are viewed as deviants, punitive or burdensome policy is more likely to pass. Others have extended this framework, such as with the racial classification model (RCM), proposed by Soss et al. (Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2008). RCM is a microlevel theory of decisionmaker cognition that does not require decisionmakers to be explicitly racist nor does it make assumptions of the decisionmakers’ racial status. Instead, it proposes that: (1) policymakers and bureaucrats rely on salient social classifications when designing and implementing policy; (2) if racial minorities comprise a salient group affected by a policy, then race will be a salient classification; and (3) as the contrast grows between those designing or implementing a policy and those the policy affects, the greater the likelihood that disparities emerge. Schram et al. (Reference Schram, Soss, Fording and Houser2009) show evidence of this in how welfare case managers decide to sanction clients, finding that they sanction Black clients, stereotyped as lazy and poor by choice, at a higher rate than their less stereotyped White counterparts. We propose that these definitions or classifications have historical roots and can be traced to earlier incarnations of social welfare policy in the US.

Other literature similarly explores how historical institutions shape contemporary political attitudes (e.g. Acharya et al. Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016; Lupu and Peisakhin Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017; Mazumder Reference Mazumder2018; Payne et al. Reference Payne, Vuletich and Brown-Iannuzzi2019), with others arguing that sustained effects may not be present (Biggs et al. Reference Biggs, Barrie and Andrews2020). For example, Payne et al. (Reference Payne, Vuletich and Brown-Iannuzzi2019) find that areas formerly home to larger slave populations now house White residents that exhibit higher levels of anti-Black implicit bias. Similarly, Mazumder (Reference Mazumder2018) finds that White people living in counties which experienced US Civil Rights protests are more likely to support affirmative action policies. These studies propose that attitudes are formed in a given moment through interactions or experience with a highly salient institution or event and the zeitgeist of the time, which are then passed down through the generations. That transfer of ideas occurs both formally and informally through the stories told, the teaching of values, and communication of culture.

A similar process may happen in the transfer of norms and definitions associated with a policy to new policies in the same general policyscape – and likely occurs through multiple pathways. First, some of the same politicians and bureaucrats may be involved in both the design and implementation of a prior policy and a more recent one in the same space, bringing a similar understanding to the design and implementation of both. Second, even if the same people are not directly involved in the elimination or evolution of a policy, their understanding of who the target population is and how they should be characterised may have been codified in documents, manuals, or logics that are either directly, physically handed down or passed down through word of mouth. This means that while the people change, the logics and construction of the problem and target population remain relatively consistent. However, that logic and understandings may weaken or morph as they are passed down through an intergenerational game of telephone, as discussed by Alexander (Reference Alexander2020) in her examination of the criminal justice system in the US. Finally, such definitions may permeate society or specific groups beyond an isolated policy, allowing them to be passed down. Thus, we propose that not only can a specific policy or institution be passed down generationally, but also can the social constructions of the target populations.

We seek to understand a particular manifestation of this path dependence by focusing on social welfare policy in the US, which is widely recognised as a racialised and gendered policy domain (Foster Reference Foster2008; Michener and Brower Reference Michener and Teresa Brower2020). The Freedmen’s Bureau not only helped to establish norms regarding the appropriate function of welfare institutions but also helped to construct the image of the associated target populations (i.e. Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993; Soss et al. Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2008; Schram et al. Reference Schram, Soss, Fording and Houser2009; Boushey Reference Boushey2016) – namely the depiction of welfare recipients as lazy and Black, or undeserving and deviant, while those paying for the programme are seen as hardworking, middle class, and White, or deserving (e.g. Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981; Tonry Reference Tonry2010). This construction of the target population could then be passed on through a similar intergenerational transfer of ideas, as discussed above and by Acharya et al. (Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016) or Mazumder (Reference Mazumder2018). To that end, we trace the path of family social welfare nested within the Freedmen’s Bureau to one of its recent iterations in TANF, which is the specific programme of focus here. Additionally, we engage with racialised and gendered nature of welfare policy in the US more broadly. We argue that areas with greater historical Freedmen’s Bureau presence exhibit amplified ties between those racialised and gendered narratives with varied implementations of TANF in the form of differences in expenditure allocations to distinct programmes.

The Freedmen’s Bureau and TANF

White reaction to the Freedmen’s Bureau

As one of the federal government’s first welfare institutions, the Freedmen’s Bureau provided relief services, built schools and hospitals, and provided legal recourse to freedpeople. Despite its name, the Freedmen’s Bureau provided its services to both freedpeople and impoverished Whites (Franklin Reference Franklin1970), though these services were segregated (Colby Reference Colby1985). Further, a substantial portion of work performed by Freedmen’s Bureau agents was designed to get freedpeople into the active labour force (Harrison Reference Harrison2006; Kandaswamy Reference Kandaswamy2021). To that end, the War Department assigned General Oliver Otis Howard to be its commissioner, and he in turn assigned an assistant commissioner to each region (generally one per state). Each assistant commissioner was granted flexibility to divide his state into subdistricts and decide field office locations based on logistic considerations, including geography, funding, regional demand, and available personnel (National Archive 2021).

The balance between the Bureau operating as a relief agency and a means for labour coercion varied from state to state (Richardson Reference Richardson1963), shaped by the administrative quality and preferences of state assistant commissioners. One such assistant commissioner, Edward Gregory, speaking with planters and newly freedpeople, emphasised the Bureau’s role in uniting Whites with Blacks, or “capital with labor” (Neal and Kremm Reference Neal and Kremm1989), highlighting both the Bureau’s labour-coercive function and the racialised class structure it had set out to reify. Nevertheless, many White individuals perceived the institution to be oppressive to White people, encouraging laziness, resistance to work, government dependence, and vagrancy among freedpeople (Olds Reference Olds1963; Phillips Reference Phillips1966).

Similarities to contemporary welfare attitudes

Contemporary, racialised narratives surrounding TANF recipients mirror the reaction of White individuals to the Freedmen’s Bureau’s early experiments with welfare (e.g. Hancock Reference Hancock2003; Mucciaroni and Quirk Reference Mucciaroni and Quirk2006; Parolin Reference Parolin2021). Consistent with the idea of “deservingness” shaping policy outcomes along racial lines, research by Winter (Reference Winter2006) reveals that White conservatives positively perceive Social Security due to its association with Whiteness rather than Blackness. This echoes research by Gilens (Reference Gilens1996), which reveals that negative sentiments among Whites concerning welfare, cannot be explained by economic status, individualism, or suspicion of government alone. Instead, racial resentment plays a significant role in shaping their views. Beyond shaping attitudes of the public, additional research shows that Black and Latina social welfare participants experience higher sanction rates (Schram et al. Reference Schram, Soss, Fording and Houser2009; Monnat Reference Monnat2010).

In addition to being racialised, views of social welfare policy are also gendered; and these gendered views may similarly have an origin in early (White) reactions to the Bureau’s activities. Kandaswamy (Reference Kandaswamy2021) calls attention to these intersections by describing the historical connection between the Freedmen’s Bureau and contemporary TANF, illustrating how the gendered and racialised assignments by each are strikingly similar. She highlights how relief was secondary to the Bureau’s core responsibilities of establishing family structures and labour relationships that mirrored those of White Americans. This was especially true for freedwomen, who were tasked with the conflicting responsibilities of homemaker and out-of-home labourer.

That freedwomen were expected to adopt the behaviours of White homemakers while being prevented from full entry into this gendered social role represents a form of racing-gendering, the process described by Hawkesworth (Reference Hawkesworth2003, p.531) which involves the “production of difference, political asymmetries, and social hierarchies that simultaneously create the dominant and subordinate.” Freedwomen who prioritised the new role of homemaker at the expense of labour participation were often labelled as prostitutes or as “playing the lady” (Kandaswamy Reference Kandaswamy2021). The contemporary label of “welfare queen,” which is most often assigned to Black women living outside of the nuclear family structure, can be traced back to this same brand of historical derogation. Freedmen, while only being relegated to a labouring role, were similarly condemned as vagrants and risked legal sanction if they refused to work (Carper Reference Carper1976; Cohen Reference Cohen1976).

While prior work has examined public opinion and perceptions of welfare and welfare recipients (Shapiro and Young Reference Shapiro and Young1989; Papadakis Reference Papadakis1992; Goren Reference Goren2003; Schneider and Jacoby Reference Schneider and Jacoby2005; Shaw Reference Shaw2009), how the racial composition of the population relates to spending and requirements (Alesina et al. Reference Alesina, Baqir and Easterly1999, Reference Alesina, Glaeser and Sacerdote2001; Trounstine Reference Trounstine2016), and how descriptive representation relates to policy and spending (2007), here we turn to how the historical presence of institutions and policies may additionally inform practices today. We argue, like Kandaswamy (Reference Kandaswamy2021), that the Freedmen’s Bureau left its mark on contemporary public assistance generally and TANF in particular. It did so through the codification of specific narratives and construction of target populations. This manifests in ways that channel historical expectations of Black labour participation and stereotypes about uncouth private morality and home-life practices. In turn, this echoes the perspective that the institutionalisation of poverty is rooted not only in individual pathologies but also in the systems and processes which shape it across time (Katz Reference Katz1993). We contribute to this literature by utilising a quantitative approach to evaluate recent decisions to allocate spending towards programmes designed to motivate work, prevent out-of-wedlock pregnancies, and maintain two-parent families.

Consistent with the idea that the intersection of historical, institutional, and social arrangements can leave a mark on contemporary institutions of similar function, we propose that the historical rate of Freedmen’s Bureau field offices in a state will be related to how that state allocates welfare money today. We primarily expect that states with a higher historical rate of field offices will allocate more spending towards programmes that aim to correct nonheteronormative private behaviours and labour nonparticipation (Coercive Allocation Hypothesis). In other words, we expect a greater commitment to programmes specifically aimed at “correcting” the stereotypes caricatured by the “welfare queen.” For this, we specifically turn to TANF allocations toward the “Prevention of Out-of-Wedlock Pregnancies” and “Two-parent Family Formation and Maintenance” programmes, which we refer to as “traditional family” programmes,Footnote 1 and towards the “Work-related Activities and Expenses” programme, which are designed to assist in and encourage gaining a job.Footnote 2 Further, we expect that states with a higher historical rate of Freedmen’s Bureau field offices will allocate less spending towards programmes that explicitly confer benefits to recipients, such as cash transfers (Cash Allocation Hypothesis). Here, we turn to TANF allocations towards the “Basic Assistance” category. We do not examine allocation to other categories, such as transfers to Social Services Block Grants and administrative costs, as there are no clear expectations of how narratives surrounding the Bureau’s activities would leave a lasting mark on these allocation decisions. However, future scholars may find alternative, historical origins for these spending decisions.

Other poverty assistance programmes existed prior to the implementation of TANF, namely state mother’s pensions and later ADC/AFDC. Each of these programmes may have been informed by legacies left by the Freedmen’s Bureau, with their structures indicating that the legacy of the Bureau may wane over time akin to the process of the criminal legal system slowly changing over time with each incarnation being modestly more equitable than the last (Alexander Reference Alexander2020). This claim is consistent with work by Skocpol (Reference Skocpol1995), who traces the development of the American welfare state from post-Civil War veterans pensions, to the formation of a distinctive maternalist welfare state, to the New Deal/post-New Deal welfare state which represented a diminished form of maternalism.

First, with regard to mothers’ pensions, access was largely limited to White mothers who abstained from labour participation (Howard Reference Howard1992), with Black families representing only 3% of recipients in 1931 (Floyd et al. Reference Floyd, Pavetti, Meyer, Safawi, Schott, Bellew and Magnus2021). This was not accidental. One of the functions of mothers’ pensions was to keep White women at home and reinforce the social class structure (Leonard Reference Leonard2005). These gendered class conventions did not transcend race, and Black mothers were expected to take on an out-of-home labouring role. Caseworkers also enjoyed substantial leeway in determining whether a case met subjective, character-based prerequisites for (Leff Reference Leff1973) facilitating the further exclusion of Black families. As mothers’ pensions were kept largely out of reach from Black households, there is little variation for us to leverage in this study.

Second, unlike TANF, which grants states wide latitude in determining how its statutory goals are met, ADC/AFDC was focused primarily on the provision of cash assistance. The creation of TANF through PRWORA gave states the ability to use federal and state maintenance of effort funds for pregnancy prevention and two-parent family formation, two spending areas which factor heavily into our coercive allocation hypothesis. Further, unlike TANF, the participation requirements and benefit levels of AFDC were subject to federal guidelines and limitations. The same autonomy in allocation decisions enjoyed by states in the current, post-PRWORA era was simply not possible before it.

Data

To test these hypotheses, we need information on both the historical and contemporary context that may relate to TANF allocations today. In our widest analysis, we look at state allocations between 2001 and 2019 across the states that existed when the Freedmen’s Bureau was created. We begin in 2001 (as opposed to 1997, TANF’s first year) as information for multiple covariates is only publicly available from 2001 forward. For example, the proportion of single-parent households was not calculable using publicly available data prior to 2001.

The flexibility given to the states to determine how to spend federal TANF funds facilitates variation. To leverage that variation, we collected data on TANF expenditures from the Administration for Children and Family’s Office of Family Assistance from 2001 through 2019Footnote 3 and what was used by Parolin (Reference Parolin2021) (2001 to 2009). Of the possible programme allocations, we focus on three general types of programme funding: (1) funds aimed at discouraging lone-parenthood (i.e. reducing out-of-wedlock pregnancies and encouraging the formation of two-parent families), (2) funds for programmes facilitating and incentivising work participation, and (3) basic, cash assistance.

The first and second categories represent expenditures aimed at coercing specific types of behaviours from participants and are combined to form our broader measure of coercive funding. As sanctions are attached to failure to meet TANF’s requirements for labour market participation, we assume that the kinds of activating labour market policies built into category two are inherently coercive, even if some would be classified as enabling labour market participation as opposed to direct workfare – two often-intertwined approaches to welfare state design highlighted by scholars such as Dingeldey (Reference Dingeldey2007). Not only do they help to legitimise labour market participation as the only pathway to dignified subsistence, but also they enable the success of TANF’s more directly coercive workfare requirements. Other TANF programmes, such as those that assist participants in accommodating their child care needs, may contribute to one’s ability to work; but because this is more indirect than those that directly aim to facilitate work participation, we do not include these in our coercive allocation category.

Table 1 shows the summary statistics for these variables. We present the summary statistics both for only those 14 states that existed as of 1870 and that had Freedmen’s Bureau field offices in the top half of the table, and summary statistics for all 37 states that existed as of 1870 in the bottom half of the table. Our core unit of analysis is the state–year dyad for which we have 630 complete observations when including all states that existed in 1870. For additional information on the collection and categorisation of this information, please see our online appendix.

Table 1. Summary statistics of key variables

There are inherent challenges involved in the use of TANF spending data, particularly those data on some of the more complex categories that leave greater room for state interpretation. For example, while basic assistance is fairly straightforward, spending strategies to achieve greater work participation or a reduction in out-of-wedlock pregnancies (for example) vary across the states (Schott et al. Reference Schott, Pavetti and Floyd2015). Additionally, in some cases, states count third-party expenditures towards their maintenance of effort requirements (Government Accountability Office 2016). Despite these challenges, we still view these data as a useful tool for assessing a state’s spending category prioritisation. Even if allocations fail to change material or social outcomes of TANF participants due to misuse or inadequacy, they signal where the state’s policy priorities lie with regard to poverty assistance.

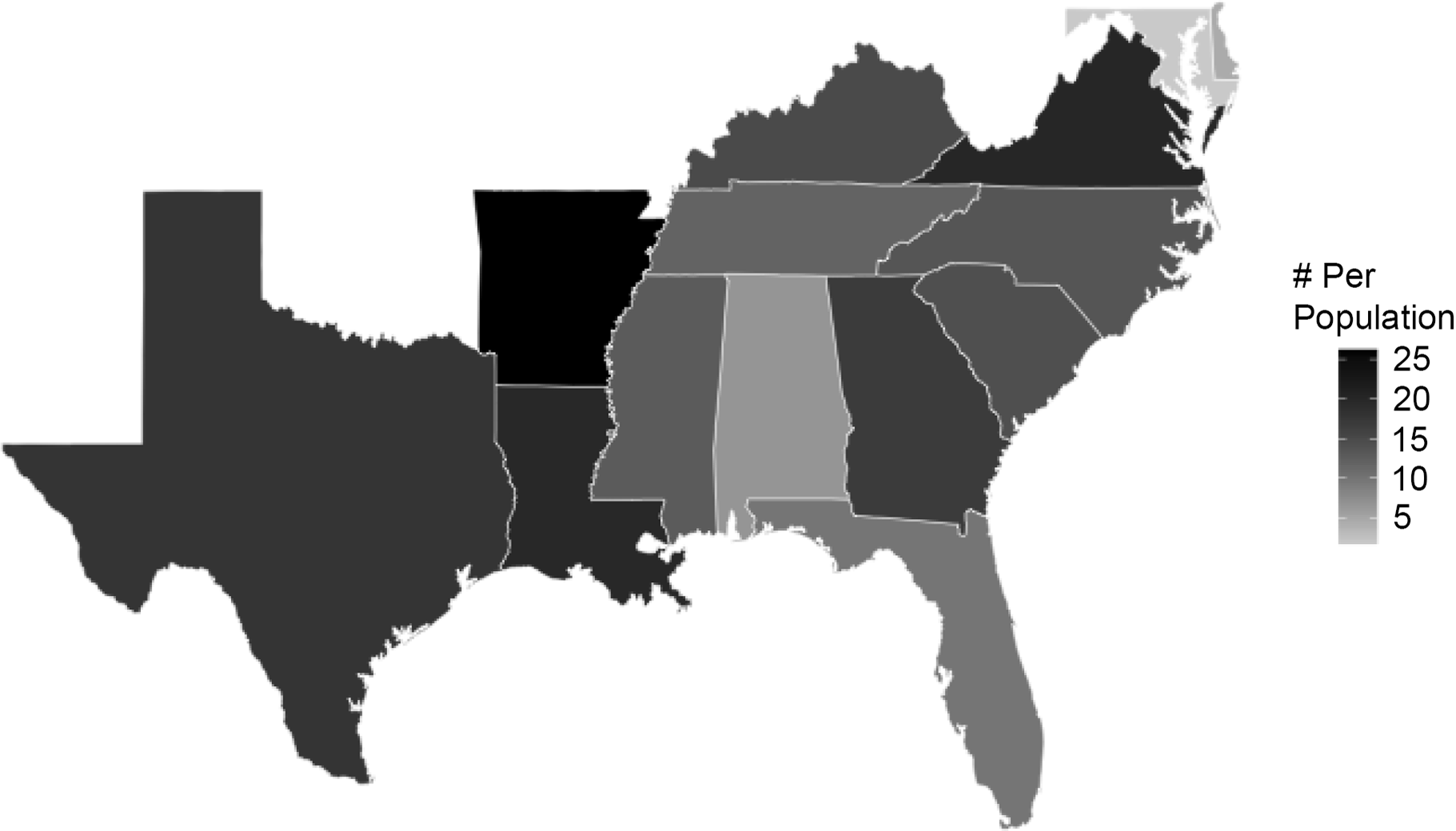

Our key explanatory variable is the relative prevalence of Freedmen’s Bureau field offices in each state, which existed as of 1870 or when Freedmen’s Bureau existed. Our measure is total number of field offices that were in use within a state between 1865 and 1872 per 100,000 Black residents as of 1870 in each state taken from Rogowski (Reference Rogowski2018). States that housed Freedmen’s Bureau field offices included the former Confederate states – South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina – and the border states of Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. However, there were no field offices located in the border states of West Virginia and Missouri (Rogowski Reference Rogowski2018). The Freedmen’s Bureau also operated within the District of Columbia (Harrison Reference Harrison2006), but due to the District’s unique role within the US federal structure, we do not include it in our analysis, leaving 14 states that previously housed field offices. We use the rate per 100,000 (1870) Black residents as our measure instead of the raw number of field offices for three reasons: first, the states had and have vastly different population sizes; second, as Rogowski (Reference Rogowski2018) shows, the number of field offices does not necessarily correlate with the number of freedpeople; and third, the salience of race when it comes to the transmission of welfare-related beliefs over time could be inferred to be higher in a state like Arkansas, since the Freedmen’s Bureau’s services – perceived to be biased in favour of freedpeople – would appear outsized compared to the Black population. The office rate ranges from 1.70 to 26.20 offices per 100,000 Black residents, with a mean of 13.60 offices and a standard deviation of 6.60. Figure 1 shows this variation across the states.

Figure 1. Freedmen’s Bureau offices per 100,000 Black residents (1870).

In the analysis that follows, we first consider the relationship between Freedmen’s Bureau field offices and TANF allocations only among those states that had offices. Then we consider the relationship within the broader sample of states that had statehood status in 1870 for a total of 37 states. This excludes 13 modern states from our analysis: Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

As a first look, we plot the proportion of TANF expenditures spent on basic assistance and on coercive programmes against the number of Freedmen’s Bureau field offices per 100,000 Black residents, both with only those states with Freedmen’s Bureau field offices and all those that existed in 1870. This is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Comparison of prevalence of Freedmen’s Bureau offices and TANF allocations.

Note: Lines show are LOESS regressions.

In Figure 2, the two left-hand panels show allocations to coercive programmes, while the two right-hand panels show allocations to basic assistance programmes, and the top row of panels include only states with Freedmen’s Bureau field offices, while the bottom row includes all states from 1870. In this initial look, we also plot the locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) regression, with the associated 95% confidence interval shown around the estimated regression line. As can be seen, there is a positive relationship between the number of bureau offices and proportion spent on coercive programmes: on average, the LOESS regression line increases across the observed range of Freedmen’s Bureau field officers per one-hundred thousand Black residents in a state. However, we observe a negligible relationship between offices and basic assistance spending. While this is suggestive that a relationship exists between historical Freedmen’s Bureau office prevalence and the allocation of TANF funds towards coercive programmes today, it is only a cursory, bivariate look, lacking controls for alternative and additional explanations.

Further, we include two sets of control variables to address two distinct concerns. First, we control for contemporaneous explanations that prior research suggests may shape TANF allocations (e.g. Clark Reference Clark2019; Parolin Reference Parolin2021). These include the percent of the population that is Black, Latino, and of another race, the percent of the population that is unemployed, the proportion of the labour force that are members of unions, percent of state legislators that belong to the Democratic party, whether the governor is a Democrat, and whether state government is divided. Information on the racial make-up of the state comes from the 5-year American Community Survey and state intercensal data,Footnote 4 while employment information and information on union membership come from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.Footnote 5 Data on the number of single-parent TANF households and the number of TANF participants under 18 years of age (used to calculate basic assistance spending per child) come from ACF TANF data and reportsFootnote 6 . Information on the partisan composition of state government comes from the National Conference of State LegislaturesFootnote 7 , and information on GDP per capita comes from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.Footnote 8 Finally, we include random effects for state and fixed effects for year, as there are likely omitted variables that may matter in explaining TANF allocations. However, as the number of field offices is static for each state, we cannot include (two-way) fixed effects.

Second, akin to the approaches taken by Acharya et al. (Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016) and Mazumder (Reference Mazumder2018), we consider whether the context from 1870 alternatively explain allocations, which we draw from the digitised version of the 1860 and 1870 censuses (Haines Reference Haines2010). These control variables include the slave population as recorded in 1860, as a key population the Bureau was supposed to serve was formally enslaved individuals, the proportion of the population that was not White in 1870, the proportion of the population that was unemployed in 1870, and the log of the total population in 1870. Finally, we should note that, while TANF expenditure and recipient data represent the fiscal year, the remaining covariates represent the calendar year associated with those fiscal years. For summary statistics of these variables, see the supplemental information.

Results

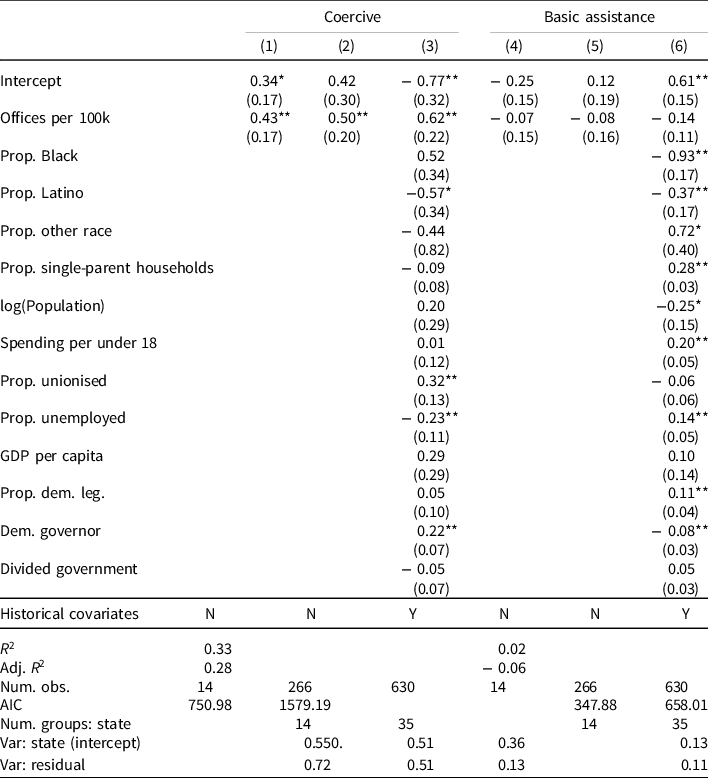

Using the data collected and described in the previous section, we first test the bivariate relationship for only states which had Freedmen’s Bureau field offices in two ways: with the mean proportions being predicted by offices per 100 thousand (N = 14, the states who had field offices) and the proportions by year and state explained by office prevalence with random effects for state and fixed effects for year (N = 266, complete cases of state–year dyads). Then we fit with both contemporaneous and historical controls, discussed in the previous section, and including all states that existed as of 1870 for which we have census data (N = 630, complete cases of state–year dyads). In the initial bivariate case, we fit ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions, while in our slightly expanded “bivariate” case and fully specified models, we fit hierarchical linear model (HLM) regressions with random intercepts for year and state and include all states that existed as of 1870. Additionally, we only show the overall allocations to coercive programmes. For the regressions explaining allocations to those categories of programmes, see the supplemental information. Table 2 shows these results. All V = variables are centred and scaled to produce more interpretable and comparable coefficients.

Table 2. Regressions explaining TANF allocations today

Note: **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1. Historical controls include the log of the number slaves, proportion of the population that was Black in 1860, the proportion of the population that was neither White nor Black in 1860, proportion unemployed in 1860, and the log of the population in 1860. Year-fixed effects included but not shown. West Virginia excluded from the full analysis due to missing data from 1860. Nebraska excluded as the state legislature is nonpartisan.

First, we evaluate whether these results show support for the Coercive Allocation Hypothesis. They would do so if the coefficients associated with the rate of Freedmen’s Bureau offices per 100,000 Black residents are positive and statistically significant in the coercive regressions (Models 1, 2, and 3). In line with our Coercive Allocation Hypothesis, we find that greater prevalence of Freedmen’s Bureau field offices is positively and statistically significantly linked to an increase in allocation towards coercive programmes. Substantively, this is a significant link in that a standard deviation increase in the rate of offices sees almost a two-thirds standard deviation increase in the proportion allocated, which is equivalent to an 8% shift in funding or approximately $104.6 million. Further, in the supplemental information, we present the results for each constituent programme and find reinforcing evidence for programmes discouraging single parenthood and in the bivariate case for programmes incentivising work.

Next, we turn to our Cash Allocation Hypothesis, which stated that higher rates of Bureau offices should be linked to decreases in funding allocated towards basic, cash assistance. We do not see support for this hypothesis as the bureau rate coefficient in the associated models (Models 4, 5, and 6 in Table 2) fail to reach statistical significance – though the results do point in the expected direction and reach a weak level of significance in the bivariate case. On balance, we find support for the Coercive Allocation but not the Cash Allocation Hypothesis.

Regarding our controls, our findings are consistent with other literature identifying a negative relationship between the proportion of the TANF caseload that is Black and cash transfers (e.g. Hardy et al. Reference Hardy, Samudra and Davis2019). Broadly, this aligns with other literature examining the role of state demographics in shaping TANF spending outcomes (e.g. Fellowes and Rowe Reference Fellowes and Rowe2004; Parolin Reference Parolin2021). Moving to our political variables, we find an inconsistent and in many cases statistically insignificant role for Democratic party strength and political contestation. Though, it is worth highlighting that this inconsistency is also apparent in the literature (Ewalt and Jennings Jr Reference Ewalt and Jennings2014, but see Rodgers Jr and Tedin Reference Rodgers and Tedin2006). However, we find that on balance the historical covariates rarely reach statistical significance.

One concern at this point is that our design decisions influenced the results. To that end, we reestimate our models in a number of ways. First, we question whether operationalising Freedmen’s Bureau field office prevalence as the rate per historical Black population rather than the proportion of counties with at least one field office in the state altered the results. To this end, we reestimate the regressions using this alternative independent variable. Again, the results remain the same (see supplemental information for these tables). Second, prior research indicates that partisanship and unionisation are intimately linked (Jacobs and Dixon Reference Jacobs and Dixon2010; Macdonald Reference Macdonald2021), which might affect our results – especially in the interpretation of those variables in the regressions. When we refit the full regressions iteratively holding out the proportion unemployed, Democratic proportion of the state legislature, and whether there is a Democratic Governor, our main results remain the same. In short, our modelling decisions appear to have not unduly influenced our results. We find robust support for our Coercive Allocation Hypothesis.

We have two final concerns about our approach: (1) that our choice to aggregate coercive programmes is masking differences between programmes; and (2) that we may be asking too much of our data set. To initially examine these points, we reestimate our models in two ways. First, we examine the components of the coercive spending individually. We see that the connection seems to be driven by the proportion allocated to promoting two-parent households (see the supplemental information for this analysis). Second, we alternatively estimate regressions using one set of controls – either the contemporary controls (N = 630) or historical controls (N = 36, allocations held at their means)Footnote 9 – at a time. In each case, the statistical and substantive results remain the same (see supplemental information for associated tables).

To further address these concerns, we fit three LASSOplus regressions (N = 630), a form of Bayesian LASSO regressionFootnote 10 , which selects and estimates effects while also returning credible intervals for discovered effects (Ratkovic and Tingley Reference Ratkovic and Tingley2017). The first of these regressions explains proportion of TANF funding spent on coercive programmes as in Models 1 and 2 in Table 2, while the second and third explain the component parts of coercive programmes as defined in this article: funding for programmes that discourage out-of-wedlock births and two-parent households (i.e. push for traditional families) and funding aimed at getting people back to work. The explanatory variables are the same as those included in the fully specified models presented in Table 2, but state and year-fixed effects are excluded, as the modelling strategy does not allow for random intercepts. However, if the selected variables are then used in HLM regressions, which is shown in the online supplemental materials, the results remain the same. As before, all variables are centred at zero and normalised.

This approach allows us to identify what variables are most predictive of TANF allocations to coercive programmes today, including questioning whether our key variable of interest, the prevalence of Freedmen’s Bureau field offices is selected. Figure 3 shows the result of these regressions. In the figure, each column indicates a different model and the associated dependent variable, while the groupings on the right-hand side indicate the cluster of variables, and the rows indicated on the left-hand side indicate the specific variable. For each model, only those variables selected by the given model are presented, with 90% credible intervals being shown and dots indicating the median values or point estimates. Note no lines cross or touch the dashed zero line. Tables associated with each model indicating the median, 5%, and 90% estimates are shown in the online supplemental materials.

Figure 3. Coefficient estimates of selected variables from Bayesian LASSOplus models explaining TANF allocations for coercive programmes.

Note: Three different Bayesian LASSOplus models are fit. The first explains the proportion allocated to coercive programmes generally, and the second and third explain the proportion allocated to the two component parts of coercive programming as defined in this article: funding for programmes that discourage out of wedlock births and two-parent households (i.e. push for traditional families) and funding aimed at getting people back to work. The possible variables the model could have chosen were: the proportion of the population that is Black, Latino, or of another race, the proportion of single parent households, the log of the population, spending per under 18-year-old, proportion unionised, proportion unemployed, GDP per capita, proportion of the legislature that are Democrats, Democratic governor, divided state government, the log number of slaves, the proportion of the 1870 population that was Black or of another race, and the proportion of the 1870 population that was unemployed. All variables are centred and normalised as in the regressions shown in Table 2. Ninety per cent credible intervals are shown as well as the median values. Only variables that are detected as different than zero on balance are shown for each model.

In Figure 3, we see that regardless of whether we aggregate or disaggregate the proportion of TANF expenditures spent on coercive programmes, field office prevalence is a key explanation for spending decisions. Further, we can see that across models the direction of the relationship is consistent: higher historical rates of Freedmen’s Bureau field offices are linked to greater proportions spent on coercive programmes. This again shows support for the Coercive Allocation Hypothesis.

To summarise our findings: across two different estimation strategies and approaches, we have found reinforcing evidence for our Coercive Allocation Hypothesis, but no support for the Cash Allocation Hypothesis. Further, we see support for the Coercive Allocation Hypothesis regardless of which form coercive allocation takes. These results again corroborate the hypothesis that the historical legacy of the Freedmen’s Bureau left its mark on contemporary welfare policymaking, at least in some respects.

Discussion

Despite serving as a vital source of material relief for newly freedpeople after the Civil War, the Freedmen’s Bureau’s activities were often just as coercive as they were liberating. The Bureau served as something of a middleman for the postwar labour market (Richardson Reference Richardson1963; Neal and Kremm Reference Neal and Kremm1989) and enforced norms regarding sexuality and gender relations (Kandaswamy Reference Kandaswamy2021). While performing these coercive activities, the Bureau faced widespread opposition – not because of its coercive behaviour, but because of perceptions that its services provided advantages for Black people at the expense of White people (Olds Reference Olds1963; Phillips Reference Phillips1966). As such, the Bureau laid the groundwork for the later role of welfare in the US – acculturating and labour-coercing – while providing a target for racialised welfare critiques which later foes of the American welfare state developed and expanded upon.

Here, we argued and showed evidence that the early construction of how people understood the target populations of welfare are linked to today’s TANF allocations. We identified the Freedmen’s Bureau as a point of origin for modern-day differences among states regarding spending allocations towards behavioural targets (e.g. discouragement of out-of-wedlock pregnancies and promotion of two-parent households) for today’s TANF recipients. Through a series of regressions, we found support for the claim that the Freedmen’s Bureau left a lasting, coercive mark on welfare outcomes within the states where its presence was most prevalent. Today, greater TANF funding is allocated into coercive programmes aimed at reinforcing behavioural norms, as well as those programmes which motivate labour market participation. These results do not come without limitations: as other studies examining how historical legacies continue to shape institutions (e.g. Charnysh Reference Charnysh2015; Mazumder Reference Mazumder2018) note, these analyses are limited in their generalisability and ability to rule out all possible additional and alternative explanations, in part due to our limited sample size.

Despite this, these findings are consistent with the idea that the social construction of target groups plays a role in public policy design, per Schneider and Ingram (Reference Schneider and Ingram1993), as well as predictions of the RCM, which centres the role of racial salience in the design and implementation of welfare policy (2008; 2011). Further, this work puts these ideas into conversation with scholars proposing that prior policy (e.g. Moynihan and Soss Reference Moynihan and Soss2014; Mettler Reference Mettler2016), even historical policies (e.g. Knill Reference Knill2001; Yesilkagit and Christensen Reference Yesilkagit and Christensen2010; Shoub Reference Shoub2022), can inform policy today. Devolution in poverty governance, such as was the case with the creation of TANF, often represents a racialised policy choice where the intersection of poverty and race manifests most strongly. Such decisions motivate the same kind of racial inequalities we see in the implementation of TANF today (e.g. Schram et al. Reference Schram, Soss, Fording and Houser2009; Monnat Reference Monnat2010).

Further, our findings reveal how state spending allocation decisions are linked to historical institutions with an overlapping, racialised social function, consistent with scholarship by Hardy et al. (Reference Hardy, Samudra and Davis2019) and Parolin (Reference Parolin2021), who identify race itself as a key determinant of those decisions. However, we find that the Bureau’s legacy appears to play little role in cash assistance allocation specifically. While the prevalence of field offices is not linked to this form of allocation, the proportion of today’s population that is Black or Latino is linked, suggesting that contemporary racial salience is more impactful than racialised historical legacies in the context of cash allocation. Thus, a possible explanation for this disparity, and for why we found robust support for our coercive allocation hypothesis but little for cash allocation, may be that coercive norms in poverty governance, once established, are difficult to break. Conversely, the denial of cash assistance is driven by the demographic salience of minority, particularly Black, populations, which varies across time.

Therefore, this article makes contributions to multiple literatures and raises questions for future study. First, this study adds to the growing conversation around racialised policy feedback (e.g. Michener Reference Michener2019; Garcia-Rios et al. Reference Garcia-Rios, Lajevardi, Oskooii and Walker2021). While much of the current research here focuses on the public’s response to feedback, this study focuses on the comparatively understudied evolution of policy motivated by this feedback. As such, there are questions as to how generalisable these findings may be to other programmes firmly ensconced within the realm of social welfare, such as Medicaid or funding for foster care systems, and to policies in other domains – although there is some evidence similar processes may be occurring as they relate to criminal justice policy (e.g. Alexander Reference Alexander2020; Shoub Reference Shoub2022).

Second, this piece diverges from prior work on policyscapes (e.g. Mettler Reference Mettler2016) by integrating work on the social construction of target populations (e.g. Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993; Boushey Reference Boushey2016). Further, we underscore the importance of history – prior policy, institutions, culture, norms – in understanding the current policy space and contemporary policy design and implementation, following up on work by Mettler (Reference Mettler2016) on policyscapes and others adopting an American political development approach to the study of policy and policy opinions (e.g. Acharya et al. Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016; Mazumder Reference Mazumder2018). In doing so, we raise new questions, such as how quickly the lingering legacy of a prior policy or institution may fade, and highlight the bounds of what this type of research design can do.

With respect to the former, one avenue for future future may be to quantitatively and qualitatively trace this across multiple policy areas or continuously over the time span, such as by directly connecting the Freedmen’s Bureau to mother’s pensions to ADC/AFDC to TANF. With respect to the latter, our approach can help establish a statistical connection, but it is limited in its ability to sort between and individually evaluate possible mechanisms and can only account for so much in the estimated models. For example, Missouri had no field office. Yet, the reason for this may be a lack of need given the considerable impact of benevolent societies which performed overlapping functions (National Archive 2004), rather than a lack of Black residents. However, further examination of these points is outside the scope of our current study but could provide the foundation for future avenues of study in this realm.

Perhaps the most important contribution of this article is that it provides additional support for the proposal that historical institutions can leave their mark on both attitudes and policies well into the future, and that this institutional legacy can help explain state-level variation across the US federal system which cannot be explained through an exclusively contemporary analysis. Where stereotypes against welfare participants saw national penetration throughout the 20th century, the transformation of those stereotypical attitudes into punitive policies saw much greater variance. The 1996 transition from AFDC to TANF represented an acceptance of anti-welfare stereotypes by policymakers, and what followed was a more coercive, less generous welfare state across the board, but this decline in quality was nonuniform. As we have shown, this lack of uniformity can, at least in part, be attributed to the enduring legacy of the Freedmen’s Bureau and its prevalence within a state. If a more productive welfare policy discourse, rid of racism and a lust for labour coercion, is to be achieved, then the roots of these policies and associated attitudes must be understood and confronted by policymakers and the electorate.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X23000168.

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/1R4WPB.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Cody Drolc and Todd Shaw for their feedback.