Introduction

The excavations at the Roman-era city of Antiochia ad Cragum on the Turkish south coast have been ongoing since 2005, and since the beginning inscriptions have been discovered that shed helpful light on the history of the city. However, 2018 was an exceptional year for epigraphical discoveries in which several inscribed stones were found that challenge long-held notions about the city and add significantly to the historical record. Two of the inscriptions found that year offer the first instances on stone of a novel toponymic epithet for the city rather than the commonly held toponymic ad Cragum. The editiones principes of both, dealing solely with physical autopsy and textual reconstruction, have appeared separately.Footnote 1 The current paper addresses the historical context of these inscriptions – civic nomenclature and possible imperial patronage in particular. The first section considers the formation of the city under Antiochus IV of Commagene and how these new inscriptions and known civic coinage reveal a different name than that by which the city is commonly known. In the second section, epigraphical evidence from one of the inscriptions is used to build a circumstantial case for a proposed visit to the city by Hadrian and Sabina in 131 CE as part of their westward journey from Egypt to Athens.

The city name of Antiochia in Rough Cilicia

In 1810 Francis Beaufort, commanding the frigate HMS Fredrikssteen, was ordered to survey the coastlines of the southeastern Aegean Sea and eastward along the south Turkish coast of the Mediterranean. The British Admiralty, engaged in the Napoleonic Wars, was keenly interested in charting potential harborages that could be used to shelter enemy ships, especially in case of French adventurism. Beaufort departed Smyrna late in the sailing season of 1811 and wintered at Malta before resuming his voyage in spring 1812. This mission afforded him the opportunity to explore the coastline of Asia Minor for something more than a military purpose, principally archaeological exploration. The observations and documentation resulting from the two-year mission served as the first major European survey of the ancient remains on these coasts.Footnote 2 Such a survey would naturally dovetail with strategic naval observations, since advantageous anchorages would probably have changed little since antiquity. It should therefore be expected that Beaufort came to Asia Minor armed with geographical texts such as Strabo and Ptolemy; indeed, references to them are peppered throughout his account.

Beaufort's report of his arrival in late (?) spring 1812 at Antioch in western Rough Cilicia is instructive. Following his visit to Selinos, as he is traveling east, he writes: “We next came to the ruins of an ancient town, which, I apprehend, must have been the Antiochia ad Cragum of Ptolemy.”Footnote 3 Ptolemy (5.7.2) is the first ancient source (late 2nd c. CE) to mention the city, using both its eponymous name and its toponymic epithet, Ἀντιόχɛια ἐπὶ Κράγῳ, by which in its Latinized form, Antiochia ad Cragum, the city is commonly known today. However, he situates Antioch between Selinos (modern Gazipaşa) and Nephelis, even though the city lies east of Nephelis, not west (Figs. 1–2). Moreover, the next city Ptolemy lists moving eastward is Anemurion, while Beaufort – correctly – gives Charadros as the next coastal city he comes to while sailing eastward. Beaufort, therefore, is not following Ptolemy blindly, for otherwise he would have confused Charadros with Nephelis. It is possible that Beaufort also had a copy of the Stadiasmus maris magni, a 3rd-c. CE maritime survey of Mediterranean shores, which not only gives the sequence of cities correctly but provides fairly accurate distances between them.Footnote 4

Fig. 1. Major coastal sites of southern Turkey from Pamphylia to Cilicia. (Map by B. Cannon.)

Fig. 2. Western Rough Cilicia. Ancient cities and major river basins. (Map by B. Cannon.)

When Rudolf Heberdey and Adolf Wilhelm visited Antioch in 1891, they appear to have accepted Beaufort's designation implicitly: “Die eigentliche Stadt Antiocheia am Kragos, von Beaufort nur kurz erwähnt, liegt bedeutend höher.”Footnote 5 Subsequently, Roberto Paribeni and Pietro Romanelli mentioned an inscription “rinvenuta ad Antiochia ad Cragum (Günei) da Heberdey e Wilhelm.”Footnote 6 By the time George Bean and Terence Mitford arrived for their epigraphical survey of Rough Cilicia in the early 1960s, they too accepted the identification, citing Heberdey and Wilhelm only in passing.Footnote 7 In fact, since most archaeological and historical references to the site use the Ptolemaic formula, Beaufort's use of it – and the Latin epithet ad Cragum – seems to mark the origin of the commonly accepted name of the city today. But from where did Ptolemy derive the name, and is it the city's original, official title?

The formal foundation of the Roman-era city and the origin of the eponymous name Antiochia belong to the mid-1st c. CE (see below). Occupation of the site, however, can be traced back to the Cilician pirates who preyed upon shipping in the coastal waters in the 2nd and 1st c. BCE. The earliest reference to the location is made by Strabo (early 1st c. CE). In his description of the coast of western Cilicia, he refers to a place east of Selinos as the “Kragos, a rock which is precipitous all around and near the sea.”Footnote 8 Appian (writing in the 2nd c. CE) mentions that the Cilician pirates operated bases on the Kragos and Antikragos when Pompey arrived to deal with the pirate threat in 67 BCE, the two redoubts serving as their “largest citadels” in Cilicia.Footnote 9 Ptolemy's and Appian's toponyms both match Strabo's, Appian adding the name “Antikragos,” which corresponds closely to the topography. The three sources appear to be referring to the same place, with the latter two relying on Strabo or another, even earlier account for the nomenclature.

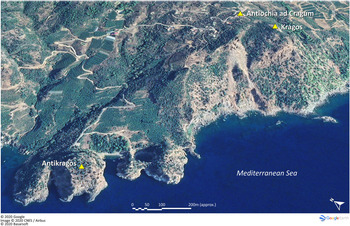

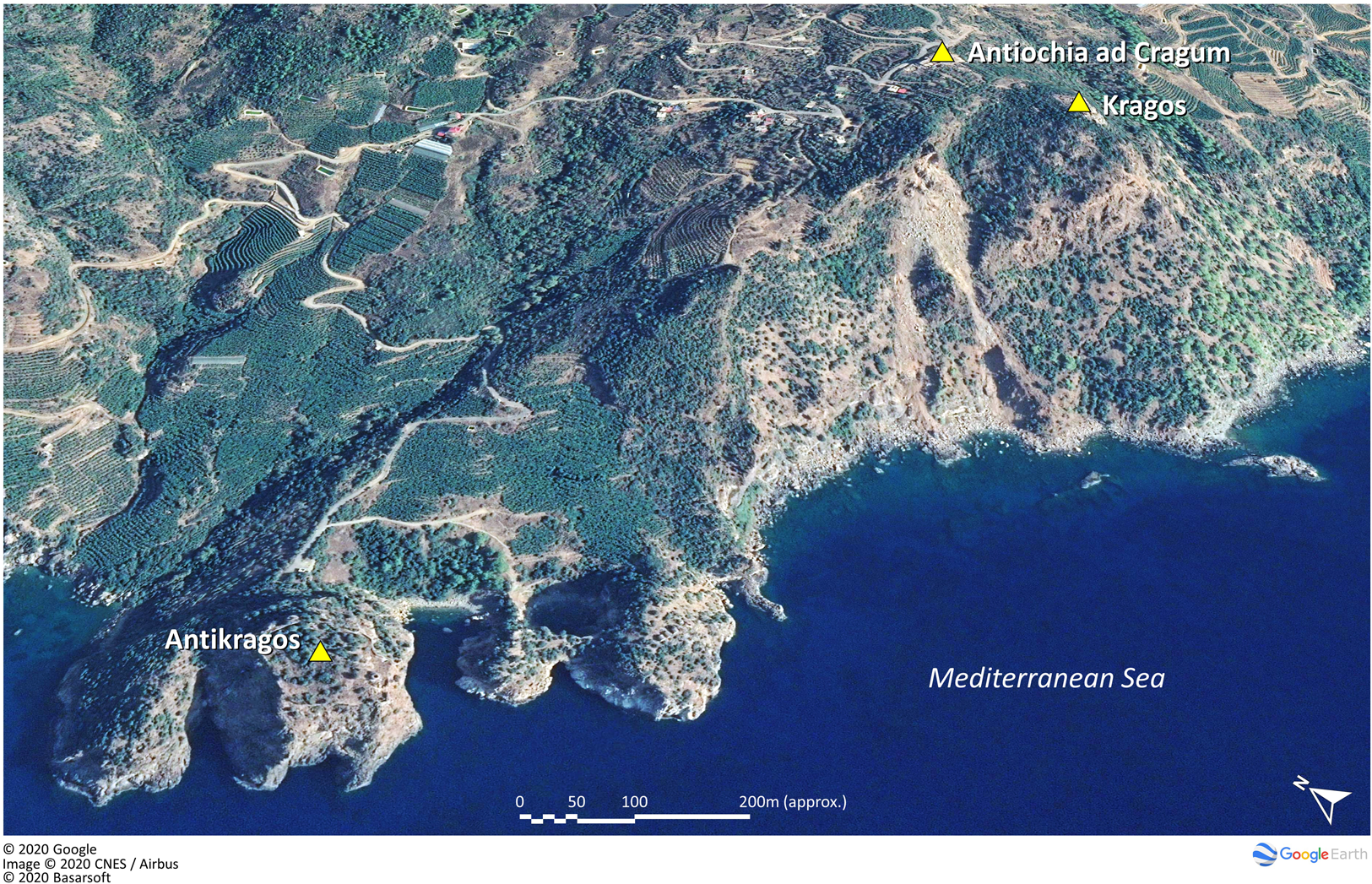

Strabo's and Appian's “Kragos” should be identified as the acropolis of the later, Roman-era city of Antioch in the modern village of Güney where the Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project has been conducting excavations since 2005 (Figs. 3–4).Footnote 10 Excavations carried out atop the acropolis, known locally as Kaleş Tepe, have uncovered a Late Roman/Byzantine Christian complex that adjoins a church. Archaeological remains of any pre-Christian structures have so far eluded detection, although some walls contain large blocks that could have been utilized in pre-Roman constructions. The Antikragos is identified as the promontory that juts out into the sea c. 1 km west of the Kragos (Fig. 5). The promontory is ringed with a Byzantine-era fortification wall, but no standing structures datable to the Hellenistic or Roman era are observable, and preliminary pedestrian surveys conducted in the late 1990s failed to locate pre-Roman concentrations of habitation.Footnote 11

Fig. 3. Aerial view of Antikragos (left) and Kragos (right). (Google, © 2020 CNES/Airbus, Basarsoft.)

Fig. 4. General view of Kragos, from the west. (Courtesy ACARP archives.)

Fig. 5. General view of Antikragos, from the northwest. (Courtesy R. Frank.)

Such lack of remains is unsurprising given the transitory nature of pirate activity. Buildings were not likely to be constructed of durable stone, but instead would be built of more perishable materials such as wood, which would naturally leave less visible footprints. Plutarch (Pomp. 28.1) in fact informs us that the pirates maintained fortresses in the higher elevations of the Taurus mountains, where their families and treasures could be relatively safe. Appian (Mith. 96) also speaks of the “mountain Cilicians.” Such higher-altitude sites probably served as their more permanent domiciles. In 2004–5, underwater survey was undertaken in the small bight adjacent to the Antikragos that is assumed to have served as the anchorage of the Roman city. This investigation did produce several finds that may be associated with the period of pirate activity: they include a fragment of a Will Type 10 amphora that is generally dated to the 1st c. BCE and a bronze socket decorated in the form of the winged horse Pegasus, a type attached to the ends of ship timbers. Wood material recovered from the socket indicates an approximate calibrated radiocarbon date of 125 BCE, which would place the socket during the pirates’ heyday.Footnote 12 While not conclusive, these stray finds offer tantalizing evidence that the anchorage, and thus likely the site as well, were occupied at the time that Appian places the pirates here.

After Pompey defeated the pirates at Korakesion (modern Alanya) in 67 BCE, he relocated many of them throughout Cilicia, mainly in Cilicia Pedias to the east. Appian claims (Mith. 96) that the pirates who were ensconced within the citadels of the Kragos and the Antikragos were among the first to surrender. Can we assume, then, that the former pirate facilities and the site were completely abandoned until Antioch was founded in the mid-1st c. CE? Given that it was useful at least as an anchorage, possibly some sort of occupation continued during this transitional period. Strabo's use of a toponym to identify the locale, rather than a place name as with all the other settlements he cites in this region (14.5.3–6 = §669–71), perhaps indicates that the Kragos was a well-known landmark even if it lacked a formal designation.

Following Pompey's operations, all of Cilicia technically became Roman territory. In 36 BCE, M. Antonius ceded to Cleopatra the territory of Rough Cilicia (Cilicia Tracheia), whose cedar forests and other timber could be used to augment her fleet that was to be used against Octavian at Actium.Footnote 13 After Octavian defeated Antonius and Cleopatra in 31 BCE, he gave Rough Cilicia to Amyntas, king of Galatia and Pisidia. Following the death of Amyntas in 25 BCE, its rule was first given to Archelaus I of Cappadocia, then to his son, Archelaus II (Cass. Dio 54.9.1–2). Rome's policy toward problematic areas often involved the use of client-kings, quasi-independent warlords whose role was to serve as surrogates to moderate peripheral areas while Rome's military could be engaged in more significant operations elsewhere.Footnote 14 In keeping with this policy, after Archelaus II died in 38 CE, Caligula awarded his friend and confidant Antiochus IV of Commagene the territory of Cilicia Tracheia and at least part of LycaoniaFootnote 15 in 38 CE.Footnote 16 However, Antiochus’s relationship with the mercurial Gaius quickly soured and he soon lost power, only to see it restored by Claudius in 41 CE.Footnote 17 Antiochus then embellished the already established Greek cities on the coast with a goal of aggrandizing his own reputation while diminishing that of local elites.Footnote 18 He allowed such cities – among them Selinos, Anemurion, Kelenderis, Korykos, Lakantis, and Elaiussa Sebaste – to mint coins, helping to solidify their role as primary urban centers in his kingdom.Footnote 19 As all these cities are coastal, Antiochus seems to have been looking outward economically, not inward, particularly with respect to trade. His rule over western Rough Cilicia, however, was not complete, as Seleucia on the Kalykadnos was not under his control.Footnote 20

Antiochus also founded several new cities within the client-kingdom. Although the ancient sources do not mention their foundation, their dynastic nomenclature makes it fairly certain that Antiochus was responsible. Some 30 km northwest of Antioch, he founded Iotape, which he named after his sister-wife or (less likely) his daughter.Footnote 21 The other new coastal city that Antiochus created, Antioch, is eponymously named. Although their precise foundation dates are undocumented, it seems untenable that Antiochus could have established these cities in the short period when he was king under Gaius, a reign that probably lasted only a few months. It is more likely that they were founded after he returned to the throne in 41 CE. Eirenopolis, Germanicopolis, and Philadelphia, high into the middle reaches of the Taurus mountains, are also believed to be his foundations,Footnote 22 presumably part of a concerted effort – with Roman help – to suppress the marauding tribes in the even higher elevations of the Taurus range.Footnote 23 His good relationship with Rome is perhaps best underscored by his role in defusing an insurrection in 52 CE, when the Cietae laid siege to Anemurion.Footnote 24 Although the Roman military was poised to end the situation with force, Antiochus solved the problem through diplomacy. The foundations of the three mountainous cities within Isaurian territory should be seen in the context of containment.Footnote 25

Antiochus presumably continued to maintain control of his realms by virtue of his good relationships with both Claudius and Nero. His rule in Cilicia Tracheia lasted for 31 years, but it came to an end in 72 CE when Vespasian removed him from his rule of both Commagene and Cilicia.Footnote 26 Emanuela Borgia suggests that his removal was not due to Vespasian's displeasure with his performance, but because of a broader political strategy of removing client-kings to allow Rome to exert direct authority over its provinces.Footnote 27 As evidence of this policy, the province of Cilicia was definitely formed in 72 CE.Footnote 28

No ancient source specifically records that Antiochus founded an Antioch (or Iotape); it is only the confluence of various threads of circumstantial evidence that led Beaufort (and all since) to match the site he came to after sailing past Selinos with Ptolemy's Ἀντιόχɛια ἐπὶ Κράγῳ. These threads are:

a) the name Ἀντιόχɛια ἐπὶ Κράγῳ given by Ptolemy;

b) the correction of Ptolemy in the Stadiasmus, which gives the proper sequence of cities along the coast;Footnote 29

c) the association of Appian's epithets Kragos and Antikragos with the distinctive topographical features of the large ancient Roman city located within the modern-day village of Güney;Footnote 30 and

d) the association of the eponymous name Ἀντιόχɛια given by Ptolemy with Antiochus IV of Commagene. Ptolemy is crucial in this linkage; he is the only source to combine the eponym, Antiochia, with the toponym, ἐπὶ Κράγῳ. Even the Stadiasmus refers to the site by its epithet only.Footnote 31

Ptolemy appears to be yet more singular: numismatic and epigraphical evidence gives an entirely different toponymic epithet, referring to the city as Ἀντιόχɛια τῆς Παραλίου (Antioch-on-the-Coast). The reverses of the city coins carry the name in the genitive plural, ΑΝΤΙΟΧΕΩΝ ΤΗC ΠΑΡΑΛΙΟΥ, either whole or in abbreviated form (Fig. 6).Footnote 32 Until the recent excavations, which have discovered more examples, these coins numbered fewer than 50 specimens,Footnote 33 ranging in date from Hadrian to Gallienus, with the majority in the 3rd c. CE.Footnote 34 Modern scholars seemingly accept the connection with Ἀντιόχɛια ἐπὶ Κράγῳ without comment.Footnote 35

Fig. 6. Antiochia ad Cragum. Valerian (117–38 CE), bronze alloy. Rev. Eagle, frontal, head turned towards left; ANTIOXEΩN THC ΠAPAΛIOY. BM 1979,0101.2561. (© The Trustees of the British Museum.)

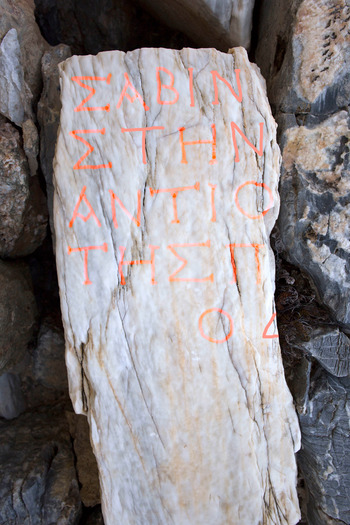

This name also has been recognized on two inscriptions found recently. One inscription, built into a Late Roman/Byzantine wall on the acropolis, belongs to a statue base dedicated by the Demos to Sabina, wife of Hadrian (Fig. 7).Footnote 36 Although only part of the inscription survives, the complete restoration of the city name is unequivocal. (The complete description of this inscription is provided in the second section.)

Fig. 7. Antiochia ad Cragum Inscription 18.4, embedded in late wall (lettering outlined). (Courtesy ACARP archives.)

The other, a small fragment of a molded stele, reused in a late wall near the Bouleuterion, contains the truncated name of the city.Footnote 37 In both cases, the complete city name parallels the numismatic evidence: Ἀντιόχɛια τῆς Παραλίου. A third inscription is relevant here, one noted by Bean and Mitford within the village of Güney. The final line of the inscription honors an embassy from the city to an emperor: [Ἀντιο]χέων πόλ[ɛως].Footnote 38 The editors’ description, along with its photograph, constitutes its only surviving record. Since neither epithet is present, it seems that the use of an epithet was not necessarily required; “the city of the Antiochenes” appears sufficient. These inscriptions represent the only known use of the city name on stone. The two inscriptions that include an epithet have the toponym τῆς Παραλίου, as do coins, suggesting that this was the city's formal name, rather than Ptolemy's ἐπὶ Κραγῳ. But the historical relationship between the two names remains intriguing. It should also be emphasized that neither coins nor any inscription known so far bear the epithet ἐπὶ Κραγῳ.

That the name Ἀντιοχέων τῆς Παραλίου belongs to the site located in the modern village of Güney is beyond dispute. Although circumstantial, and despite the lack of numismatic or epigraphical examples, the evidence for the association of this same site with the Ἀντιόχɛια ἐπὶ Κράγῳ of Ptolemy is also convincing. The reason for two different epithets, however, is less clear. The toponym Kragos appears to have identified the locale before it achieved urban status. From the late Hellenistic era or earlier, the Kragos, with its prominent cliffs, promontory, and anchorage, all clearly visible from the sea, was well known, especially while serving as a pirate enclave.Footnote 39 The second epithet, τῆς Παραλίου, appears only on stone and coins from the 2nd c. CE onwards. Perhaps when Antiochus IV founded his eponymously named city, he created a new, independent epithet, τῆς Παραλίου, to serve as its official civic name. Was it Ptolemy, then, who created the hybrid Ἀντιόχɛια ἐπὶ Κράγῳ, bringing together the eponymous name with the old toponym? The contrasts in medium and type of document are curious: written, secondary sources, on the one hand, speak of Ἀντιόχɛια ἐπὶ Κράγῳ; inscribed, primary sources, on the other, refer to Ἀντιόχɛια τῆς Παραλίου. Is this an imaginary or chance distinction, or might it have to do with how the city was known to foreigners versus the local administration and inhabitants? Whatever may be the case, it appears to be an example of “old habits die hard,” for the graphic epithet ἐπὶ Κράγῳ outlived the less colorful and less memorable τῆς Παραλίου.

Antioch honors Hadrian and Sabina

Among the inscriptions described in the previous section was a statue base (AI 18.04) honoring Sabina, wife of Hadrian. Also discovered in 2018 was another statue base, this one dedicated to Hadrian, which had been reused as wall material for a Late Antique structure. These two statue bases represent the only known imperial dedications yet found in the city. But they are hardly unique; similar dedications have turned up in other cities in the region. This section argues that, taken as a group, the inscriptions may mark the itinerary of the imperial couple as they made their way from Egypt to Athens in 131 CE.

Statue base of Hadrian (AI 18.06; Fig. 8), 117–38 CE

Marble statue base reused in east wall of Peristyle Building. Remains in situ. Base l. 0.65 m; base w. 0.40 m; letter h. 0.03 m.

Fig. 8. Antiochia ad Cragum Inscription 18.06, embedded in east wall of Peristyle Building. (Courtesy ACARP archives.)

Text

ΑΥΤΟΚΡΑΤΟΡΑΚΑΙΣΑ[ΡΑΘΕΟΥ] Αὐτοκράτορα Καίσαρ[α, θɛοῦ]

[ΤΡΑ]ΙΑΝ[ΟΥΠΑΡΘΙΚΟΥΥΙΟΝ] [Τρα]ιαν[οῦ Παρθικοῦ υἱόν,]

[ΘΕΟΥΝΕΡΟΥΑΥΙΩΝΟΝ] [θɛοῦ Νέρουα υἱωνόν,]

Τ[ΡΑΙΑΝΟΝΑΔΡΙΑΝΟΝ] Τ[ραιανὸν Ἁδριανὸν]

5 [ΣΕΒΑΣΤΟΝΤΟΝΚΥΡΙΟΝΚΑΙ] 5 [Σɛβαστόν, τὸν κύριον καὶ] ?

[ΕΘΕΡΓΕ]Τ[ΗΝΤΗΣΟΙΚΟΥΜΕΝΗΣ] [ɛὐɛργέ]τ[ην τῆς οἰκουμένης,]

[ΟΔΗΜΟΣ] [ὁ δῆμος]

Publications: Unpublished.

Commentary: Much of the inscription has been worn away; only the first two words of line 1 are legible enough to warrant a clear reading. Line 2: only IAN is readable but enough to allow a reconstruction of ΤΡΑΙΑΝΟΥ. Lines 3–6: we reconstruct the rest of the text to be the same as that on the Kestros 1 base (see below). We observe on line 6 a tau whose position would fit with EUERΓΕΤΗΝ of Kestros 1.

Statue base of Sabina (AI 18.04; Fig. 7), 128–37 CE

Embedded as spolia in the northwest wall of Building 5 on the acropolis are five fragments of a statue base of white marble. The largest fragment contains the upper left half of the block's dedicatory inscription; the fragment is split laterally, preserving much of the original lettering. The exposed face shows heavy pitting due to weathering. Remains in situ.

Fragment l. 0.65 m; w. 0.20 m; letter h. 0.027 m.

Text

ΣΑΒΙΝ[ΑNΣΕΒΑ]Σαβῖν[αν Σɛβα]−

ΣΤΗΝ[ΘΕΑΝ]στὴν [Θɛὰν]

ΑΝΤΙΟ[ΧΕΩΝ]Ἀντιο[χέων]

ΤΗΣΠ[ΑΡΑΛΙΟΥ]τῆς Π[αραλίου]

5 ΟΔ[ΗΜΟΣ]5 ὁ δ[ῆμος]

Publications: Hoff and Howe Reference Hoff and Howe2020.

Commentary: The late wall in which the statue base fragments were incorporated is located at the western extremity of the Acropolis, which consists of a Late Roman/Early Byzantine settlement with a series of churches, outbuildings, and towers. Sabina is here spelled without an epsilon, a departure from the normal nomenclature but not unknown. At Ephesos there is an honorific inscription for Sabina, where her name is similarly spelled without an episilon (Σαβῖναν; IEph 278=McCabe Reference McCabe1991, 1010). The date of the inscription at Antioch can be placed after 128 CE, when Sabina was given the honorific title of Augusta (Σɛβαστή), probably at the same time that Hadrian accepted the title pater patriae.Footnote 40 Our restoration in line 2 of θɛάν following Σɛβαστή is speculative, but the word conforms to the need for similar spacing in lines 2 and 3 based on parallel construction (eight and nine characters, respectively). The use of θɛά may be in reference to Hera as a counterpart to Hadrian Olympios. Sabina is described as θɛά in several inscriptions at Ephesos, but not elsewhere.Footnote 41

These two inscriptions can now be added to the corpus of honorific statue bases dedicated to Hadrian and Sabina that have so far been identified in western Rough Cilicia.Footnote 42 Table 1 indicates the distribution of inscribed Hadrianic statue bases in the region among the known Roman-era cities (see also Fig. 9). The table shows that half of the urban sites (poleis) in the region contain at least one Hadrianic base, and in two cities there are paired bases to Hadrian and Sabina. Several of the bases are recorded to have been found in situ or close to in situ. In all of these cases the original locations appear to have been within or close to an imperial temple or a walled enclosure for the purpose of displaying imperial statuary. For example, at Iotape the statue base was observed by Bean and Mitford as standing in the “small temple, seemingly that of Trajan.”Footnote 43 Hadrian's nomenclature is normative, although the text does refer to him as “despot of the earth and sea.”Footnote 44

Fig. 9. Major sites of western Rough Cilicia with distribution of Hadrianic bases. (Map by B. Cannon.)

Table 1. Distribution of Hadrianic statue bases in western Rough Cilicia

Sources: Iotape: Paribeni and Romanelli Reference Paribeni and Romanelli1914, 181–82, no. 128. Kestros 1: Bean and Mitford Reference Bean and Mitford1970, 159, no. 163; AÉpigr 1972, 648; Hagel and Tomaschitz Reference Hagel and Tomaschitz1998, 149–50 Kes 17. Kestros 2 (with Sabina): Bean and Mitford Reference Bean and Mitford1970, 159–60, no. 164; AÉpigr 1972, 649; Hagel and Tomaschitz Reference Hagel and Tomaschitz1998, 150 Kes 18. Lamos: AÉpigr 2005 (2008), 1549; SEG LV 1518; Rauh et al. Reference Rauh, Wandsnider, Ozaner, Hoff, Townsend, Dillon, Korsholm and Caner2018.

Kestros, approximately 14 km northwest of Antioch, sits atop a ridge (376 m a.s.l.) approximately 1 km from the coast. Inscriptions at the site were earlier studied and published by Bean and Mitford, who visited on several occasions in the 1960s. They identified a structure at the southern extremity of the visible ruins as an imperial temple that included no fewer than six statue bases. The base centered at the rear of the cella honored Vespasian, leading Bean and Mitford to assume that the temple belonged to him; other bases along the side walls belonged to Titus, Nerva, and Trajan.Footnote 45 The final two bases closest to the doorway were dedicated to Hadrian; that on the east side also contains a dedication to Sabina. The two Hadrian statues thus stood facing each other.

Kestros 1 (west base)

Αὐτοκράτορα Καίσαρα, θɛοῦ Τραιανοῦ

Παρθικοῦ υἱόν, θɛοῦ Νέρουα υἱωνόν,

Τραιανὸν Ἁδριανὸν Σɛβαστόν, τόν

Κύριον καὶ ɛὐɛργέτην τῆς οἰκουμένης,

5 ὁ δῆμος.

Kestros 2 (east base)

Αὐτοκράτορα Καίσαρα, θɛοῦ Τραιανοῦ Σαβɛῖναν

Παρθικοῦ υἱόν, θɛοῦ Νέρουα υἱωνόν, Σɛβαστήν

Τραιανὸν Ἁδριανὸν Σɛβαστόν, π(ατέρα) π(ατρίδος),

τὸν κύριον καὶ ɛὐɛργέτην

5 ὁ δῆμος.

Bean and Mitford proposed that the two dedications were made at different times. They posit that Kestros 1 was dedicated at the beginning of Hadrian's reign (c. 117 CE), while Kestros 2 dates no earlier than 128 CE, when Hadrian received the title of pater patriae. They further suggest that Kestros 2's dedication may have been prompted by a visit to the region by Hadrian, a suggestion echoed by Simon Price.Footnote 46 Kestros 2 is composed of a single block of marble, 1.64 m long, on which statues of both Hadrian and Sabina stood. The nomenclature of the Antioch base exactly matches that of both Kestros examples up to the word Σɛβαστόν. From this point there is a departure of nomenclature to allow for custom phrasing.

The site of Lamos is situated atop a long ridge that parallels the coastline, approximately 11 km inland (see Fig. 2). The statue base dedicated to Hadrian was discovered by the Rough Cilicia Survey Project in 2001 within a 36-m-long, rectangular enclosure to the northeast of and overlooking the agora.Footnote 47 Several sites within the region contain such walled enclosures, which appear to have been constructed for the express purpose of displaying statues, many of them imperial.Footnote 48 The text of the inscription has appeared in Année Épigraphique and SEG, but as the inscription has never been discussed, it is worthwhile reproducing it here:Footnote 49

Αὐτοκράτορα Καίσαρα Τραια[νὸν]

Ἁδριανὸν Σɛβαστόν, πατέρα

πατρίδος, τὸν κύριον καὶ τῆς [ο]ἰκου-

μένης vacat

5 ὁ δῆμος.

Again, the nomenclature follows common protocols for other dedications to Hadrian found in the region. He is described as “Lord of the inhabited world,” a similar title to that found on the Kestros examples, and echoing Iotape's “despot of the land and the sea.” He is named as pater patriae, thereby suggesting a terminus post quem of 128 CE.

Imperial visits to provincial cities were often the catalyst for various sorts of reciprocal dedications such as these, part of the practice of euergetism in the Roman world.Footnote 50 The Historia Augusta (13.6–7) mentions that Hadrian dedicated temples and altars during his travels in the east; and Cassius Dio reports (69.5.2–3) that cities Hadrian visited often received imperial benefaction. It is well known that the peripatetic emperor toured most of the provinces of the empire, and much has been written about his itineraries.Footnote 51 Although the literary sources are silent regarding a visit to Cilicia during his third itinerary, we know one must have occurred – or was expected to have occurred – as coins commemorating it (Adventus) were issued, probably in Tarsus, with Hadrian on the obverse and the personification of Cilicia on the reverse.Footnote 52 The date when Hadrian appeared in Cilicia has been open to question, but recent scholarship appears to have settled on 131 CE, during his westward journey from Egypt.Footnote 53

If the date of the trip is generally accepted, the exact itinerary is not.Footnote 54 The only sure signposts are that Hadrian spent the winters of 130/1 CE in Alexandria and 131/2 CE in Athens. This time frame therefore gave him just over six months of optimum weather to make the journey. As for stops en route, dedications found in the cities of Cilicia and elsewhere provide evidence of the imperial entourage as it proceeded along the coastline, first in the Levant, then to the south Asia Minor coast, and then along the Aegean coast in Asia.Footnote 55

Scholars have also differed on whether Hadrian traveled by land or by sea.Footnote 56 Clearly, the sea route was more direct and had the advantage of avoiding the difficult mountainous terrain. T. Corey Brennan suggests a hybrid approach for the itinerary; westward progress occurred by the sea route, with stops at predetermined locations and occasional forays inland to visit more remote locales.Footnote 57 Surviving documentation suggests that, as might be expected, organizing an itinerary for an emperor and retinue required considerable advance planning.Footnote 58 The destinations would have been announced perhaps months beforehand, in order to provision the large entourage, but also to allow provincials to prepare for the ceremony of the imperial adventus. A sea voyage along the coast must have involved a sizable contingent of ships, and these would have required suitable anchorages convenient to the cities where the emperor could stop. The evidence for harbors in western Rough Cilicia is limited.Footnote 59 Iotape had a naturally enclosed harbor, but it was very small. Selinos preserves no remains of a constructed harbor per se, but the Hacımusa river, which empties into the sea at Selinos, is thought to have been canalized before the time of Trajan, suggesting that ships did put into port there.Footnote 60 A number of sources refer to Charadros as a port.Footnote 61 Antioch does not appear to have had a constructed harbor but did possess a relatively sheltered anchorage. Of these sites, Hadrianic dedications have been found only at Iotape and Antioch (Table 1); of the two, Antioch (the larger city) would have been the more logical choice for an imperial visit. One can imagine a scenario where the emperor disembarked at Antioch, and then either met with embassies from other communities in the area, including inland cities such as Lamos and Kestros, or else visited those communities directly by traveling overland, in the hybrid fashion suggested by Brennan.

All indications are that Sabina accompanied Hadrian. There is no doubt that she was in Egypt with her husband, as she left behind a graffito carved on one of the statues of Memnon in the necropolis of Thebes as testimony to her presence.Footnote 62 Scholars who claim Sabina's presence in the entourage point to dedications in Asia Minor, in both single or joint dedications along with Hadrian, including Kestros in Rough Cilicia (referenced above); Magydos in Pamphylia; Rhodiapolis, Patara, and Tlos in Lycia; Tralles in Caria; Hierapolis in Phrygia; Pisidian Antioch; and Magnesia in Ionia.Footnote 63 Clearly, the closest relevant example to the Antioch dedication is the double dedication to Hadrian and Sabina at nearby Kestros. The formula is simpler than that found at Antioch, with Sabina referred to only as Sebaste. But the inscription adds to the considerable epigraphic testimony that the empress was present for the journey.

Possibly accompanying the imperial couple was Julia Balbilla, an acclaimed poet and a member of the Roman elite.Footnote 64 We know that she was present along with Hadrian and Sabina in Egypt because she too left her mark on the Colossi of Memnon with verse graffiti that have long been known and studied.Footnote 65 It appears she had been a friend of Hadrian and Sabina perhaps for several decades, along with her brother, C. Iulius Antiochus Epiphanes Philopappos.Footnote 66 Since the entourage was headed to Athens, it seems reasonable to assume that Balbilla, like her brother a resident of that city, would have accompanied Hadrian and Sabina. Moreover, Balbilla would have had a familial interest in visiting western Rough Cilicia, as it was her grandfather King Antiochus IV of Commagene who founded Antioch and nearby Iotape shortly after 41 CE.Footnote 67 There is no evidence that Balbilla had ever visited the region previously, and thus we can imagine the citizens of Antioch being as excited to greet Balbilla as they were to host Hadrian and Sabina in the city, a visit that must have been celebrated by Antioch's citizenry, especially in the accompaniment of the imperial couple.

Another example of the effect that Hadrian's visit in 131 CE had on the region may be seen on coinage. The mechanism that provided the privilege of minting coins by provincial cities is not well understood, but, in the case of at least some of the cities of western Rough Cilicia, it may be that the emperor himself granted this privilege.Footnote 68 Prior to Hadrian, the only cities in the region that minted coins were Anemurion and Selinos. Beginning with Hadrian, however, the cities of Antioch, Iotape, Kestros, and Lamos minted coins.Footnote 69 Curiously, no coin of Hadrian survives from Kestros, but there is a single issue that features Sabina, with the inscription ΣΑΒΕΙΝΑ ΣΕΒΑΣΤΗ, the same minimal titulature as on the statue base from the city.Footnote 70

Finally, it is tempting to think that Hadrian would have wished to visit one city in particular in western Rough Cilicia. In 117 CE the emperor Trajan suffered a medical emergency while sailing westward along the Rough Cilicia coast. The ship put into the nearest anchorage, which turned out to be Selinos, and it was there that Trajan died. Recently it has been argued that Trajan's body was cremated while still at Selinos, and subsequently the ashes were carried to Rome to be deposited inside the Column of Trajan.Footnote 71 It is further argued that a temple was constructed over the exact location of the ustrinum to honor the deceased emperor.Footnote 72 One can imagine that Hadrian would have insisted on viewing the location where his adoptive father literally became divus, and where he himself was elevated to the emperorship. The name of Selinos was, in fact, changed to Traianopolis to reflect the honor given to it by Trajan's death within its walls.Footnote 73

Western Rough Cilicia would have made for some nostalgic and poignant memories for Hadrian, Sabina, and Balbilla, perhaps providing sufficient enticement to include this rugged region in their itinerary. We can therefore imagine that, for a brief, shining moment in 131 CE, the citizenry of Antioch, a normal, everyday provincial city nestled in the far reaches of the Roman world, very possibly witnessed the power and pageantry of the Roman Empire in their own backyard.

Conclusions

Until recently, little was known about Antioch save its name and location. Now, after 15 years of excavation and study, discoveries abound. Artifacts that are found each excavation season help to shed light on the city, as well as adding to the growing knowledge of the region of Rough Cilicia more generally. This paper has presented recently discovered epigraphic material, together with the evidence of civic coinage, to demonstrate that the city's “official” name likely was quite different from what the ancient sources related, Ἀντιόχɛια τῆς Παραλίου (Antioch-on-the-Coast) rather than Ἀντιόχɛια ἐπὶ Κράγῳ (Antioch-on-the-Cliff). Again, through epigraphy, it has shown that the city honored Hadrian and Sabina, possibly in 131 CE during an imperial visit to the region.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge with gratitude the annual excavation and research permits granted by the Archaeological Directorate of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of Turkey. We are grateful to private donors, the Merops Foundation, and the many students and volunteers who annually participate in the field school program that have made our research possible. For this particular paper, we would like to thank the School of Art, Art History & Design and the Hixson-Lied College of Fine and Performing Art of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln for their generous subvention support, and we appreciate the comments of the anonymous reviewers. Most especially, we acknowledge John Humphrey, whose final work as editor of JRA included, at least in part, this paper; we dedicate it to him, with humble thanks.