Introduction

What is the difference between weakness of will and compulsion? The two phenomena are similar in that they both involve an agent acting in a way that is other than what she, in some sense, takes to be the thing to be done. However, the felt experience of an agent going to a party when she has decided to study appears to differ significantly from the felt experience of an agent relapsing into drug addiction despite her best efforts, which suggests that they are, in fact, distinct. Making the distinction is important because we tend to think that when people merely act in a weak-willed manner their behavior is their fault, but when they act out of genuine compulsion it is not. There is a significant literature dedicated to trying to distinguish the two phenomena (see, for example, Watson Reference Watson1977; Audi Reference Audi1979; Mele Reference Mele1987, Reference Mele2002, Reference Mele2012; Buss Reference Buss1997; Tenenbaum Reference Tenenbaum1999; Wallace Reference Wallace1999; Kennett Reference Kennett2001; M. Smith Reference Smith, Stroud and Tappolet2003; Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker2003; Zaragoza Reference Zaragoza2006; Strabbing Reference Strabbing2016).

Philosophical orthodoxy holds that the difference lies in the degree of resistibility the agent in question has over resisting her tempting impulse. Kevin Zaragoza (Reference Zaragoza2006: 251) calls this the ‘standard view’ of the distinction, and Hanna Pickard (Reference Pickard2015) catalogues the ubiquity of the notion that compulsions are irresistible throughout the philosophy of action. This line of thought is called into question, though, by a recent turning of the tides that challenges the view that control is the hallmark of agency. An important competing current holds that we ought instead to look to the agent's psychic structure in the actual sequence of events that leads to her action in order to tell whether or not the agent was agentially involved in the right sort of way in the production of her action to be seen as authoring it. Attributable actions, it is thought, are produced by motivational states that have some sort of privileged position in the agent's psychic set such that it makes sense to say that the agents identify with them in some way. On such identificationist views, when actions are attributable to agents they can express features of the agent such that she can be blamed or praised on their basis (Watson Reference Watson1996; A. Smith Reference Smith2012; Talbert Reference Talbert2016). These views are promising in part because they sidestep long-standing debates about the compatibility of control with determinism, and they seek to make sense of the fact that behavior that people are genuinely exempt for performing is often accompanied by an experience of agential alienation. This current at least suggests an alternative conception of the distinction between weakness of will and compulsion: the difference lies not in the degree of control the agent has over her action, but rather in the source of the impulse in the agent's psychic structure.Footnote 1

Despite the promise of this kind of alternate approach, most identificationist views surprisingly tend not to be constructed to make fine-grained distinctions among the set of actions that agents perform that run counter to what they take to be the thing to do. Instead, they tend to hold that an agent's not acting in line with what she has determined is the thing to do is sufficient to count as non-agentially involved action. In this way, they fail to offer a way to distinguish compulsion from weakness of will, holding, counter to what most think, that both are non-attributable. The inability of identificationist views to distinguish between weakness and compulsion, it has been alleged, is a fatal flaw for the identificationist approach.

In this article, I provide a solution to this problem by offering an original identificationist conception of the difference between weakness of will and compulsion that isolates a way in which weak-willed, but not compulsive agents, are psychologically aligned with their courses of action. In short, the view is that a compulsion is an action that is motivated by a desire that an agent acts on in order to expunge it rather than because she approves of its object. A compulsive desire is compulsive not because an agent cannot control whether she acts on it, but because its source is in tension with her agency. By contrast, a weak-willed action is an action that an agent undertakes in part because of the fact that she would reflectively give at least some weight to acting on it due to some aim of hers (other than the aim to get rid of her motivation to so act). An agent who ‘gives weight’ to a desire in my sense need only desire to some (possibly outweighed) degree to act on it even when she is aware of the alternative conflicting desires she has that she could act on. (Taking oneself to have a pro tanto reason to act on a desire is neither necessary nor sufficient to distinguish the phenomena in question.) Making the distinction in this way not only provides a genuine identificationist alternative to the orthodox view, but it also provides unique resources for explaining the ethics of managing one's compulsions.

1. Preliminary: Clarifying the Subject

Standardly, weakness of will is taken to be akrasia, acting against one's better judgment. This has been challenged by, for example, Richard Holton (Reference Holton1999, Reference Holton, Stroud and Tappolet2003, Reference Holton2009) and Alison McIntyre (Reference McIntyre2006), who take weakness of will to instead be acting against what one resolves or commits to doing. As I discuss below, recent views that take a person to exercise her agency by aligning what she does with what she most cares about doing or conatively endorses doing suggest other candidate accounts of weakness of will. In order to keep all of these views on the table I take weakness of will to refer to an agent acting against what she herself takes to be the thing to do in whatever the relevant sense ends up being.

The term compulsion is more unwieldy. It has a variety of meanings in common parlance, mental health practice, and in psychology. In philosophy, it is used almost as a term of art, which, as far as I can tell, does not neatly map onto any definition one might find in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. When I speak of compulsion I refer to what I believe is a genuine psychological phenomenon that is discussed by philosophers in which an agent decides that a certain action would be the one to perform but feels pulled to and ends up doing something else, where she is not at fault for the outcome. This phenomenon then makes sense to be contrasted with weakness of will, understood as a phenomenon in which an agent chooses to do one thing but feels pulled to and ends up doing something else due to their own weakness, or fault.

This philosophers’ sense of compulsion seems to describe only some proper subset of the behaviors primarily displayed by people with mental health disabilities like addiction, obsessive-compulsive disorder, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, trichotillomania, eating disorders, Tourette syndrome, provisional or persistent tic disorder, agitated depression, and misophonia. It is also possible for someone without any of these mental health conditions to act compulsively sometimes. Complicating matters even more, there is some evidence that the cases that philosophers have assumed to be paradigm cases of the philosophers’ sense of compulsion may not be at all.

For example, the prototypical person with obsessive-compulsive disorder who feels the need to check repeatedly that the oven is turned off before leaving the house, making her late for her meeting, may not be being pulled against her will to check the oven after all. Instead, she may be acting on the pathologically acquired belief that she is doing what is necessary to prevent the horrific outcome of her apartment building burning down which she believes would be all her fault (Cougle, Lee, and Salkovskis Reference Cougle, Lee and Salkovskis2007). The prototypical person with a drug addiction may not be being overcome by an overpowering desire she resists but rather making use of the only effective coping mechanism she has access to for managing distressing symptoms of her comorbid psychiatric disorder (Pickard Reference Pickard2012, Reference Pickard2016). Studies show that people with eating disorders often self-report purging to seek a sense of control or self-punishment to cope with a core belief about their social desirability (Dingemans, Spinhoven, and van Furth Reference Dingemans, Spinhoven and van Furth2005).

Given this, some may worry that all cases are explicable in such terms, such that philosophers who are engaged in the project of distinguishing compulsion from weakness of will are engaged in a fool's errand, as there is no real phenomenon corresponding to the philosopher's notion of compulsion and thus nothing that is even prima facie difficult to distinguish from weakness of will. But I think this takes the worry too far. First, these sorts of agential experiences are surely heterogeneous; some people certainly do experience an overwhelming pull to take drugs that they wholly disavow, which is enough to make it a phenomenon well worth discussing. Secondly, even if the philosophers’ sense of compulsion only corresponds to the experience of some minority of drug users or people diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder, there are less commonly discussed cases that might serve as more accurate paradigmatic cases, including people with Tourette syndrome and misophonia (Gorman Reference Gorman and Shoemaker2019). In what follows, I use compulsion to refer to compulsion in the philosophers’ sense. Accordingly, when I give cases of addiction, I assume that the addiction of the agent in question is volitional rather than cognitive, leaving open the question of just how many instances of action motivated by addiction fit this profile.

I mention this at the outset because when I offer my account of the distinction between compulsion (in the philosophers’ sense) and weakness of will, it can seem that I am saying that cases in which people who do meet the criteria of some folk-notion of compulsion who do not fit the criteria for my account of compulsion are responsible and thus ought to be blamed for what they do. But my aim in this article is just to identify a sense of compulsion that, unlike weakness of will, exempts an agent from responsibility by virtue of her action's being non-agential. Agents who are not so-exempted may yet be exempted or excused for other reasons, or else responsible but not blameworthy because they do what they subjectively morally ought to do, given their epistemic situation.

2. A New Account of the Distinction

The orthodox view is that what makes compulsions compulsive is that they consist in irresistible urges for which agents cannot be held responsible since they, in some sense, could not have acted otherwise (at least in normal situations). They are thus distinguished from weak-willed actions by some notion of ability or control that can explain why weak-willed actions are, by contrast, ‘resistible’ in some sense (M. Smith Reference Smith, Stroud and Tappolet2003). I believe that a more promising route to distinguishing weakness from compulsion looks at the kinds of psychological incentives that underlie what agents actually do instead of looking at what they could have done.

The main alternative to control-based accounts of agency is the identificationist framework, which locates agency not in an agent's control over her actions but in the expression of her aims through her actions. As the focus is on agents’ relationships to the psychological processes that in fact cause them to act rather than on an agent's ability to do otherwise, the identificationist framework ought to be a natural fit for constructing such an alternative account of the distinction between weakness and compulsion. Somewhat surprisingly, though, identificationists have failed to produce a leading competitor account of the distinction. In fact, the identificationist's inability to adequately distinguish weakness from compulsion has been seen as one of the major downfalls of the identificationist program, even as a nail in its coffin (Vihvelin Reference Vihvelin, Luper-Foy and Brown1994; Haji Reference Haji1998, Reference Haji and Kane2002; Fischer Reference Fischer2012a, Reference Fischer2012b; McKenna Reference McKenna and Kane2011, Reference McKenna, Coates and Tognazzini2019; McKenna and van Schoelandt Reference McKenna, Van Schoelandt, Buckareff, Moya and Rosell2015; Strabbing Reference Strabbing2016). John Martin Fischer (Reference Fischer2012b: 131), for example, calls the problem of weakness of will ‘decisive’ for Harry Frankfurt's flagship identificationist view. As such, my main goal here is not to provide an original or knockdown objection to control-based accounts, but rather to show that it is possible to draw an identificationist distinction between weakness of will and compulsion and to articulate a version of such an account that can act as a competitor to the orthodox control-based view.

What is it about the identificationist program that has made it difficult to distinguish weakness from compulsion? According to the identificationist, most of our actions express something about what we are like as agents, which opens us up as agents to be the proper targets of assessment on the basis of what we have done. What goes wrong in cases of compulsion, according to the identificationist, is that the production of action circumvents the normal channels through which an agent comes to act in a way that expresses something about what she is like as a person. The motivational state on which she ultimately acts comes from outside the bounds of her agency and interferes with the motivational states she is identified with. A person who struggles with substance abuse who wants to remain sober after rehab might decide to partake in sober activities only. Nevertheless, at any particular moment her compulsion to take drugs instead might move her to action.

Most identificationists give the following kind of explanation for why her resultant action is in fact compulsive and does not genuinely express what she is like as an agent: while she chose to participate in a sober activity, a rogue desire to use drugs overpowered the normal agentially involved process of following through on her choice. Different theorists cash out the nature of this choosing in different ways. For example, on views like Michael Bratman's (Reference Bratman2003) planning view, it amounts to her committing herself to treating her reasons to stay sober as decisive in these sorts of scenarios (see also Frankfurt Reference Frankfurt and Schoeman1987). On views like Harry Frankfurt's (Reference Frankfurt1971) endorsement view it amounts to her reflecting on her desires and picking her desire to do a sober activity as the one she most wants to act on. And on views like Gary Watson's (Reference Watson1975) valuing view it amounts to her deciding that her all-things-considered best option is to stick with the sober activity since she values it most, which, if nothing were awry with her agency, would have a decisive motivational pull of its own.

The problem is that these explanations of what makes these actions compulsive overextend to cases we tend to think of as mere weakness of will cases, in which we do think that agents reveal what they are like for the purposes of appraisal on the basis of what they are like as agents. (This is why, for example, Bratman has clarified that his identificationist view should not be taken as minimal condition for one's action to be able to speak for her, but, instead, as an account of full-fledged autonomy or self-governance.) Consider a familiar case:

Sam's Exam: Suppose Sam knows she should be studying for her final exam, even though there is a party going on that night that she really wants to go to. She judges that it would be best for her to study for her exam, endorses her desire to study for her exam, plans to study for her exam and cares about studying for her exam, and yet somehow she ends up going to the party anyway. Sam does not act on what she judges it best to do, or in line with what she plans to do, or on the desire she higher-order endorses.

Common sense tells us that Sam's action, while weakly willed, was still self-expressive. Of course, we could tell a version of this story in which Sam just has a compulsion to go to parties, but there are versions of the story in which that is not the case and something much more ordinary is going on. The identificationist seems to misclassify these weakness of will cases as compulsive, since the agent in question is moved to act counter to what she chooses in each of the major senses of choosing that the traditional identificationists have in mind.

What has gone wrong? Part of the problem is that these identificationist views fail to be able to account for the fact that an agent's will is not revealed only through her executive choosing power. They are not able to acknowledge the fact that, at any given time-slice, an agent can be identified with more components of her psychic set than just the desire that she has, after deliberation, picked out and decided to act on. Since Sam is already identified with her desire to study, they are unable to acknowledge that she might also be identified with her desire to go to the party.

Instead, in order to make the distinction, we need a view of which part(s) of an agent's psychic structure get to count as self-expressive that allows for coexisting conflicting states. As Chandra Sripada points out, this requires acknowledging that the agential self is ‘mosaic’ and that ‘conflict can and often does extend all the way to our very practical foundations’ (2016: 24). Examples of mosaic views include caring views (Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker2003; Sripada Reference Sripada2016), on which the criterion for identification is that an agent acts in the promotion of what she cares about, in which she may encounter conflicting motivations due to having an imperfectly cohering set of cares; and whole self views (Arpaly and Schroeder Reference Arpaly and Schroeder1999), on which the criterion for identification is that the motivation the agent acts on is sufficiently (but perhaps not entirely without conflict) integrated into her psychic set.Footnote 2

But I do not think Sripada's diagnosis and proposed remedy to the problem go far enough. Consider the following case:

Sam's Pacing: Suppose Sam has decided to stay home and study for her exam and is overtaken by a sudden whim to pace around her dorm room instead.

Following Jada Strabbing (Reference Strabbing2016: 16), it seems strained to say that Sam cares about pacing around the room or that her desire to do so would be suitably related to any sorts of distinctive caring states she has. Likewise, it does not seem that her desire to do so need be particularly well integrated with the rest of her psychology. But it is likely that Sam's desire to pace around the room is not just a random fluke either. In fact, it may be that whimsical desires always stem from subconscious intrinsic desires. As Nomy Arpaly and Timothy Schroeder argue, ‘in each case [involving someone acting on a whim] it is easy enough to imagine credible intrinsic desires that each person might have such that the person's whim is instrumental toward, or a realizer of, the content of the intrinsic desires.’ It seems plausible that there will always be similar stories to tell about whimsical desires even if the agents themselves do not always have access to the explanations (Arpaly and Schroeder 2013: 10).

But, given the dialectic, care theorists cannot appeal to presence of a mere intrinsic desire to show that these are weakness of will cases rather than compulsive ones, because they are at pains to show that caring states are not reducible to mere intrinsic desires, and instead involve a complex set of dispositions. Sripada does take caring states to be partially constituted by intrinsic desires, and so he may tell a similar story to show how the presence of these intrinsic desires is evidence that the agent's whimsical desires are suitably related to her caring states. However, it is just not clear that the sorts of intrinsic desires for which these sorts of whimsical desires are instrumental towards or realizer desires of need always be related to what she cares about in Sripada's sense. Similarly, just because a whim may be instrumental towards or a realizer desire of some intrinsic desire does not mean that this intrinsic desire is especially well integrated into the agent's psychology at all.

It is plausible that Sam's pacing around the room is caused by a subconscious fear of failure that is suitably related to the fact that she cares about being a good student, or some other of her deeply held psychological states. But it is equally plausible that her motivation to pace is generated by a spontaneous and fleeting intrinsic desire to not think so hard; she is moved to act on a desire that realizes an intrinsic desire that she has no long-term or emotional investment in whatsoever.

It is interesting to note that David Shoemaker, who also advances a care theory, seems to embrace openly the fact that according to his view these sorts of whims are not attributable to agents (Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker2015: 113). The costs of this move are mitigated by the fact that, according to his picture, agents who act on whimsical desires may be candidates for answerability responsibility or accountability responsibility, for which reactive attitudes can be fitting even in the absence of attributability. But for the project of distinguishing weakness of will from compulsion based solely on whether or not the action is rightly said to be attributable to the agent, this is a more significant cost to the view. Instead, I take the lesson here to be that we have to accept that there are aspects of our genuine agential selves that are spontaneously held, fleeting, or happenstance. Identificationist views fail to be able adequately to distinguish weakness of will from compulsion not just because they often don't allow for competing strands of attributable agency, but because they conflate agential involvement or attributability with some notion of agency par excellence. If we are to use degree of agential involvement to distinguish weakness of will from compulsion, we will have to make the cut-off point much lower than most identificationist theories would have it, allowing that an agent can have quite minimal attachment to the desire she ends up acting on without it counting as compulsive.

This leads me to my positive proposal. On my view, an agent's will is revealed through aspects of her self-reflexive conative personality that are present at the time of action. These conative aspects of the agent may be diachronically extended or not, they may be aspects that the agent is herself aware of or not, and they may or may not be aspects of her agentive personality that she puts great stock in. In order for an action to be rightly classified as weakly willed rather than compulsive the agent just needs to have some aim in acting on the desire she does that does not stem entirely from the force of the desire itself. This aim need not amount to her taking herself to have a good reason to act as she does, but rather she must have some higher-order state that functions as her approving to some degree to act on the desire, and not just because it would be good to rid herself of the desire by acting on it. Compulsive desires, by contrast, are desires that have their own motivational force that the agent does not in any way conatively align herself with.

Because this notion of conative alignment is somewhat obscure, I will say a bit more about what I mean by this. To illustrate, the conative alignment that I take weak-willed acts to have that compulsive acts do not is perhaps best explained by way of contrast with Frankfurt's (Reference Frankfurt1971) notion of endorsement. On Frankfurt's theory, an agent endorses a desire to ϕ by reflecting on her potentially conflicting first-order desires (desires to do something or other) and forming a second-order desire (a desire about a first-order desire) that she most wants to act on her desire to ϕ, what he calls having a ‘second-order volition’ (Frankfurt Reference Frankfurt1971: 10). Like Frankfurt, I am interested in desires that agents have about whether or not they want to act on other desires of theirs. But unlike Frankfurt, I think that merely partial endorsement of acting on a desire is enough to count. When an agent desires only to some small degree to act on her first order desire to ϕ, the ϕ-ing that results from this can still be attributable to her. Crucially, this means that in weakness of will cases where an agent wants to act on a first-desire to ϕ to some degree but wants to act on her first-order desire to ψ more, if she ends up ϕ-ing instead this can still be agentially self-expressive.

The notion I am after also differs in that I do not think that an agent need actually have an occurrent desire to act on her desire to ϕ at the moment of action, but rather she needs to be such that in the relevant worlds she would give some weight to her desire to ϕ at the time of action if she were to reflect on her first-order desires. Importantly, it is part of the view that the worlds at which we evaluate whether or not she gives weight to her desire to ϕ are the worlds in which we hold fixed everything else about her psychology at the moment except for the fact that she has reflected. A weak-willed frustrated tennis player who throws her racquet is likely to be such that she would give some weight to her desire to act as she does in the moment if we hold fixed the psychological mechanisms that lead to her desire to do so, even if she would not in a cooler, calmer moment. So, unlike the valuing view, it can hold that these sorts of weak-willed actions are attributable.

Finally, on Frankfurt's notion of endorsement, an agent's wanting to act on a certain desire of hers for any reason whatsoever is sufficient for identification with that desire. In contrast, while I think that agents can come to be identified with desires for almost any reason (or lack thereof) whatsoever, I do think the agent must give weight to her first-order desire for some aim other than eliminating her desire. This is because I think it is the source of the agent's motivation more so than the executive authority the agent has over the desire that is relevant to identification. When an agent acts on a desire just to manage the motivation internal to that desire itself, I do not believe that this changes the source of the motivation or generates its own sense of conative approval. So, for example, when a person wants to act on her desire to perform her compulsive action because the psychological pain of not doing so is so great that she acts before the urge overtakes her, she still acts compulsively, on my view. These further aims will often be, but need not necessarily be, aimed at goods the desire seeks. An agent could be weak-willed, for example, by being tempted to act on a desire to hit someone because she wants to know how it would feel to act on her passing urge to hit someone. Elsewhere (Gorman (Reference Gorman and Shoemaker2019) I refer to this kind of endorsement for a further aim than elimination ‘approval’ and the weak sort of hypothetical and partial approval ‘minimal approval.’ The weak-willed agent, but not the compulsive agent, minimally approves of acting on the desire that ends up moving her to action.

Formally expressed, the view is as follows:

An agent acts out of compulsion iff she wants most to act on a desire to ϕ, but acts on a desire to ψ instead AND her doing so comes about either via the sheer force of her desire to ψ absent any further aim she has in ψ-ing, or via the mere management of a desire to ψ (prototypically: ψ-ing in order to rid herself of the desire to ψ).

An agent acts out of weakness of will iff she wants most to act on a desire to ϕ, but acts on a desire to ψ instead AND the sequence of mental states that lead her to ψ are suitably related to the fact that if she were to reflect on her desire to ψ at t, she would want to act on it with some further aim in doing so other than merely eliminating her ψ-desire.

Note that in this formulation I say that the agent's coming to act as she does needs to be ‘suitably related’ to her approval of acting on her effective desire. What is the nature of this relationship? I suspect the relevant notion is something like the fact that either (a) whatever it is in the agent's psychology that disposes her to be such that she would have (or form) a second-order desire of this sort in most close worlds also plays some role in the causal sequence of her action production (even if it is overdetermined that she would act as she does without it); or (b) the second-order desire itself plays a role in the production of her action. The intuitive thought is this: Suppose there is a person who has experienced pervasive gambling compulsions over the course of many years and desperately wants to stop. If, one day, she acquires a slight sense of intrigue at the prospect of winning money at the slot machine to pay for something, but this desire is wholly unrelated to the psychological mechanism of her gambling addiction and plays no causal role whatsoever in her coming to gamble that day, we ought to be able to say that she is still acting compulsively rather than being weak-willed.

3. Managing Compulsions

How does this new identificationist account of the distinction between weakness of will and compulsion fare compared to the more orthodox control-based views? One worry that may surface is that there seems to be something deeply intuitive about the importance of difficulty resisting an urge that seems crucial to the way we ought to divide weakness from compulsion, and, furthermore, that to forgo the importance of this would be to classify people for the purposes of praise and blame unfairly.

First, I want to speak to the broad charge that any account of the distinction between weakness and compulsion ought to be able to explain why experiencing compulsions prototypically makes agents feel like they are out of control and why this, at least on the face of it, seems to have moral import. I think my account can offer a powerful error theory for this intuition. If it is almost always the case that when agents act on a desire to ϕ, their doing so is related to the fact that they want to act on a desire to ϕ for some further aim, then cases in which this is not the case will likely often take agents by surprise. Having genuinely compulsive desires can be a deeply alienating experience for the agent, both because the compulsive desires may be felt to be alien, but also because ideas about how one should relate to compulsive desires often fall outside of the purview of the general societal norms and advice about how one ought to interpret and orient their behavior appropriately. This could easily lead to a sense of feeling out of control. It would also not be surprising if it was the case that as a matter of empirical fact, it will often feel more difficult to get oneself not to act on a desire that has no correlation to what you approve of doing than to a desire whose motivational force is sensitive to your aims and priorities. So there may be fairly substantial overlap in the extensions of the two theories. The difference is that the difficulty one has in resisting a piece of behavior is not essential to what makes something a non-attributable compulsion on my view.

While my view can offer this error theory to the general charge, when the views do diverge my view may seem to have unintuitive or unfair consequences. Of course, the very nature of the project of finding an identificationist account of the distinction between weakness and compulsion is such that if you are accustomed to a control-based account of the distinction between weakness of will and compulsion, there will be upshots of any account that will diverge from what may have come to be thought of as our common-sense pronouncements about different cases. Nevertheless, worries may linger about some of the particular upshots of the account. First, the view may seem especially austere in classifying the vast majority of cases in which agents act against what they most want to do as cases of weakness of will rather than compulsion. One might, for example, wonder whether it is really true that a person who has a very strong desire to act on her desire to drink in order to get rid of the urge, but is also motivated to some very small degree by a desire that she endorses for some further aim (say: she thinks it will help her relax and wants to relax), is really weak-willed rather than compulsive if she has the drink. Since this is enough to meet the threshold that I identify for weakness of will, I am committed to saying that her action does reveal or express something about her for which we can blame her. However, I need not be committed to the view that as much is revealed about her as would be the case if her action were solely motivated by a weak-willed desire for relaxation. Although developing this idea fully is beyond the scope of this article, I find it somewhat plausible to speak of attributability of actions as a gradable notion that corresponds to the ratio of attributable to non-attributable desires that motivate the agent's action. On this view, weak-willed actions could be considered more or less compulsive without being deemed compulsive actions full stop. This may help somewhat to mitigate concerns that the view is unnecessarily harsh in some of the verdicts it delivers.

On the other side of the coin, the view might seem to classify as compulsive too many things that are under our control, exempting us in cases in which it intuitively seems like we ought to be held responsible. I am committed to the claim that it can be the case that a person's compulsive action is non-attributable even if she could have done otherwise had she resisted, making it so that we cannot judge her on its basis. On my view, compulsions need not even be particularly difficult to resist to make a person exempt from their resultant actions being attributable. Not only might this seem to classify too many things as compulsions, but one might also worry here about desert. In cases in which moral wrongdoing could have been prevented easily, the thought goes, the agent seems to deserve blame. A related worry concerns the fairness of not blaming such agents when the view simultaneously holds that people can be blameworthy for weakly willed actions that would have been very difficult to control.

The view, however, has the resources to show that in some cases, while agents are not directly responsible for acting in pursuit of the objects of their compulsive desires, they may nevertheless be responsible for the management of their compulsive psychology. Since the view focuses on the agent's approval of the content of the desires that she acts on rather than her ability to act other than she does, we can come to a more fine-grained analysis of her orientation towards the action. For example, suppose there are two agents who utter a slur in public. While one tries but fails to suppress her negative feelings towards a particular minority, which motivate her to utter the slur, the other has Tourette syndrome (a condition that in rare cases causes the urge to utter slurs) and no negative feelings towards minorities. The agent who has Tourette syndrome, let us suppose, is able to suppress her urge to say a slur, temporarily, with some amount of psychological effort. She could, in this case, suppress her urge to say the slur until she is out of public earshot. Due to the fact that it would be uncomfortable, though, she chooses not to wait and discharges the ticcing urge in public earshot. On my view, both agents could, in theory, be blamed for something they do, but the former would be blameworthy for acting on her desire to say the slur and the latter would only be responsible for failing to forestall her compulsive urge.

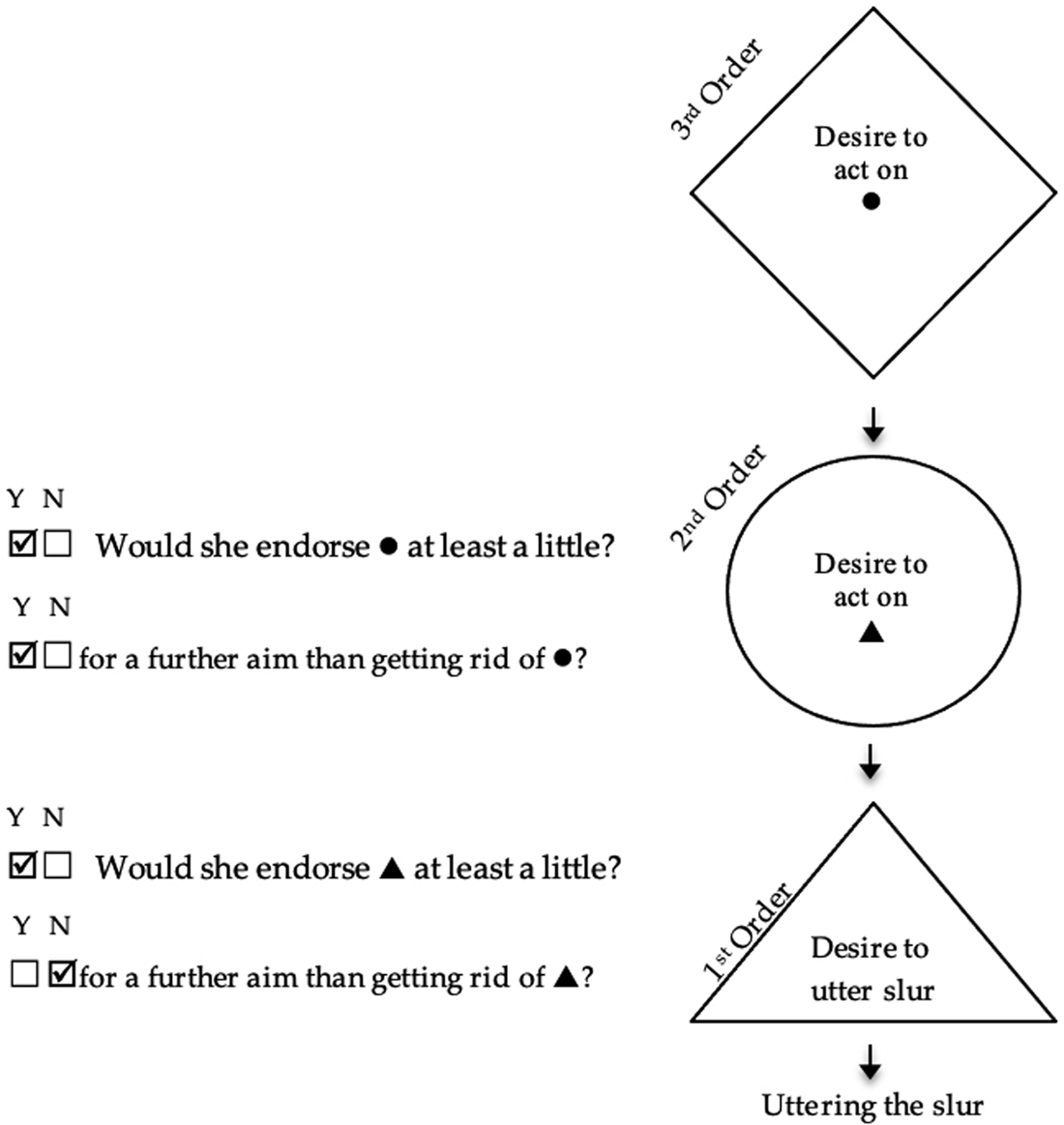

One way to understand how to distinguish the desires on which the two agents act is hierarchically. While the person with Tourette syndrome who fails to forestall her tic to utter a slur acts compulsively in regard to her first-order desire according to the theory, she is not compulsive in regard to her second-order desire. An agent who acts on a desire that she approves of acting on with the aim finding comfort in relieving her painfully felt compulsive urge opens herself up to appraisal on the basis of this second-order desire, even if not on the basis of the content of compulsive urge (see figure 1).

Figure 1 The psychological profile of an agent who acts compulsively in regard to her first-order desire but not her second-order desire.

When a person makes a choice to act on a desire in order to get rid of it, she will usually endorse the desire to relieve herself of the urge for some further aim like comfort, an increased ability to focus on other things, or the like. This is what I think we ought to say about most cases involving itches, for example. We scratch itches purely to get rid of the discomfort of having the urge to itch, but we approve of getting rid of that discomfort. Suppose there is a deeply important ceremony in which remaining absolutely still is a sign of respect, but you give in to an easily resistible urge to scratch an itch. While you might not be responsible in just the way that someone who waves her arms about just to interrupt the ceremony would be, you can be responsible for approving of a desire to relieve yourself of the discomfort of your urge when the integrity of the ceremony was at stake. We are, admittedly, not used to thinking about itches as compulsive, but some of this strangeness may simply come from the fact that itches rarely cause the same kinds of social strife that compulsions do since they are usually innocuous. This gives us a way to appraise agents for the management of their compulsions (and itches) without the cases collapsing into descriptions of cases in which agents are appraisable for what they do in the ordinary way, which involves their expressed approval of the content of their first-order motivating desire. This is important since the factors at play in the ethics of managing one's psychology are different from those at play in the ethics of uttering slurs (see also Gorman Reference Gorman and Shoemaker2019).

It is the case that an agent will almost always non-compulsively act on a desire for comfort, or something of the like, in cases in which she is deciding to act on a desire in order to get rid of it. This might raise the worry that extending the account to take these approvals of second-order desires into consideration risks making people responsible for the management of their compulsions too often to be plausible. But I think that the correct normative ethical theory should just tell us that in most cases acting on a compulsion now rather than letting it take over later for the sake of our own comfort is not a bad thing to do, since the timing of the action will often make no difference. Furthermore, our conventional norms about when a person ought to have to manage her compulsion ought to be set in a just way. Setting these norms in such a way may even give difficulty some role to play, but only at the first-order normative level.

Once we recognize that our social norms regarding the interpretation of compulsive behavior likely need revising, allowing that people may be appraised for the management of their compulsions in many cases is not a hard bullet to bite for a supporter of the view. In fact, it can help explain how someone could be praiseworthy for forestalling acting on a compulsive urge until a more appropriate time (say when one person who her slur targets will be in earshot rather than two) without also having to simultaneously be deemed directly blameworthy for acting on the object of her compulsive desire to say a particular slur. In this way, the ability to appraise the agent on the basis of her behavior at this finer level of granularity gives the identificationist a unique advantage for approaching the ethics of managing one's compulsions.

4. Conclusion

Cases of weakness of will can be distinguished from cases of genuine compulsion by making use of an identificationist criterion rather than on a notion of control. In order to make such a view feasible, I have shown that there is a quite minimal, but nevertheless crucially important sense in which weak-willed agents do identify with acting on the desires that they do. Weak-willed agents, but not compulsive agents, are such that they would at the time of action approve to some degree of acting on the desire they in fact act upon for some aim of theirs. This explains why we are permitted to take their actions to be self-disclosing despite the fact that they have chosen elsewise. This view of the distinction between weakness and compulsion has sophisticated resources for engaging with the ethics of managing one's compulsion. While it might have initially seemed that the view would unfairly exempt people for easily resistible compulsions, these worries are ameliorated by the fact that the view can distinguish questions about the ethics of the management of one's compulsions from general questions about the ethics of, say, uttering slurs.

Taking my account of the distinction between weakness of will and compulsion on board requires to some degree ceding ideas we may have had about what it means to be an agent.

In order to be acting agentially, you need not exercise control, and, contra some other identificationist views, you need not make effortful attempts to act according to what you think best. To be an agent is, on my view, to take on a less dignified role than many have thought. It is crucially important that we are able to act on desires that we want to act on because they align with our aims, but our human aims have no essential dignity to them. The aims we approve of can be fleeting, arise in us spontaneously, and be directed at things that we know we should not do or even try to steel ourselves against doing. But acting in accordance with them nevertheless exposes us, as individuals, for who we are. All of the aims that we give some weight to via our approval are really us, not just the aims we consciously see as or attempt to make central.

In accepting that acting on even fleeting and faint desires that we approve of can express our agency just as acting on our long-term convictions can, we will also have to forego a belief in the tight connection between praiseworthiness and acting out of strength of will. Acting to banish negative influences or develop the skill of steeling oneself against them in order to act more reliably in accordance with the Good can itself be praiseworthy, and, as such, it may still make sense to say that it is virtuous to cultivate strength of will. Acts of willing our better impulses to win out may themselves be praiseworthy, but actually acting on those impulses is, on this view, no more praiseworthy for our having been more resolute in our conviction to do so.

Rather than see these alterations in our conception of agency as concessive, though, I think they can help us understand the ways in which, while we can express parts of ourselves in much of what we do, we are not deity-like creatures. I have aimed to show how we can be responsible even when we do not fully endorse the objects of the desires we act on. That said, the picture of agency I have sketched also seems to imply a kind of agential fragility that might nevertheless inspire a virtue of mildness in our appraisals of one another.