The Nuosu (Nosu) Yi language, or Northern Yi (北部彝语), is spoken by approximately two million people in southern Sichuan Province and northern Yunnan Province, China, the majority of whom are monolingual. Yi is a member of the Yi Branch of the Lolo-Burmese subgroup of the Tibeto-Burman family (Benedict Reference Benedict and Matisoff1972/2009, Bradley Reference Bradley1979), which includes some 50 languages, also called the Nisoic languages (Lama 2012) or Ngwi Group. The large (5 million) ethnic Yi nationality groups of Yunnan Province are distantly related. The third author, Lama Ziwo, who was 31 at the time of recording, produced, translated and transcribed the recorded audio data phonemically and participated in the laryngoscopic filming of the video data. He is a native speaker of the Suondip/Suondi dialect, and a fluent speaker of the Shypnra/Shengza dialect. It is the Shypnra/Shengza standard dialect that is being represented in this paper. The most distinguishing phonetic feature of Northern Yi is its systematic vocal register contrast (Matisoff Reference Matisoff1972, Dai 1990) between two settings of the laryngeal constrictor mechanism, which are referred to as a lax (unconstricted) series and a tense (constricted) series (Edmondson et al. Reference Edmondson, Esling, Shaoni, Harris and Ziwo2000, Reference Edmondson, Esling, Shaoni, Harris and Ziwo2001). The contrast is realized as a distinction in resonance (spectral quality) rather than as contrasting phonation types as in some other forms of Yi or in other Tibeto-Burman languages (e.g. Bai). The consonantal inventory is large, with complex vocalic interactions, including interactions with two pairs of fricativized vowels. Northern Yi has 43 initial consonants, five pairs of vowels (or syllable rhymes), and three tones: 55, 33, and 21. Relevant reports on voice quality in related languages can be found in Maddieson & Ladefoged (Reference Maddieson and Ladefoged1985) and Sun & Liu (Reference Lu1986).

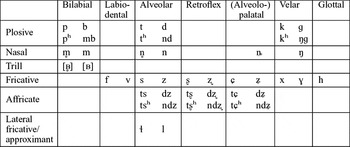

Consonants

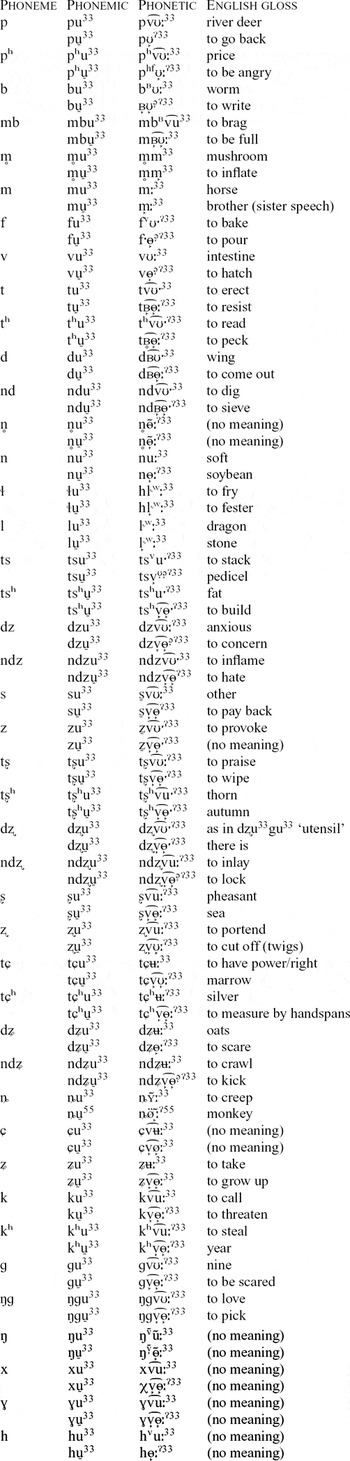

In the consonant list, two examples are given for each phoneme, the first with a lax vowel /u/, and the second with the corresponding tense vowel /

![]() /. All examples in the list are words with 33 tone (except for one at 55). All paradigmatically possible CV syllables are represented with these vowels in order to fully illustrate the auditory quality of the laryngeal phonetic contrast, even though there are gaps in the lexicon where these syllables have no meaning. Some systematic incompatibilities may limit these vowels occurring, particularly with /ŋ x ɣ h/. In the narrow phonetic transcription, small superscripts generally signify a less intense or shorter incidence of a sound. The bilabial trills identified in the consonant chart in square brackets occur phonetically following bilabial and alveolar stops, as discussed under Conventions. These trills vary in intensity and are not intended as a component of the root initial. Where two consonant symbols appear in the phonetic form, such as [

/. All examples in the list are words with 33 tone (except for one at 55). All paradigmatically possible CV syllables are represented with these vowels in order to fully illustrate the auditory quality of the laryngeal phonetic contrast, even though there are gaps in the lexicon where these syllables have no meaning. Some systematic incompatibilities may limit these vowels occurring, particularly with /ŋ x ɣ h/. In the narrow phonetic transcription, small superscripts generally signify a less intense or shorter incidence of a sound. The bilabial trills identified in the consonant chart in square brackets occur phonetically following bilabial and alveolar stops, as discussed under Conventions. These trills vary in intensity and are not intended as a component of the root initial. Where two consonant symbols appear in the phonetic form, such as [

![]() m], they are not meant to imply double syllables but rather a long nasal with shifting voicing properties. The realizations of laterals /ɬ/ and /l/ have both a lateral and central approximant feature in /u/ and /z/ vowel contexts, transcribed as [l˞] to indicate a quality between /l/ and /ɹ/. The superscript /ʷ/ indicates roundedness on the syllable. The alveolo-palatal nasal is transcribed with the /ȵ / symbol used in the Sino-Tibetan tradition, in parallel to the symbols for the other alveolo-palatal sounds and in preference to the palatal nasal symbol [ɲ]. Some vowels, especially in front-consonant contexts, may acquire a more fronted quality: [ɵ], [ʉ], or even [ʏ] or [ø]. Laryngeally tense syllables exert an effect on the CV string, particularly on vowel quality, but also, for example, /x/ realized as [χ], or closing the syllable glottally [ˀ]. The [v] component is a function of this particular /u

m], they are not meant to imply double syllables but rather a long nasal with shifting voicing properties. The realizations of laterals /ɬ/ and /l/ have both a lateral and central approximant feature in /u/ and /z/ vowel contexts, transcribed as [l˞] to indicate a quality between /l/ and /ɹ/. The superscript /ʷ/ indicates roundedness on the syllable. The alveolo-palatal nasal is transcribed with the /ȵ / symbol used in the Sino-Tibetan tradition, in parallel to the symbols for the other alveolo-palatal sounds and in preference to the palatal nasal symbol [ɲ]. Some vowels, especially in front-consonant contexts, may acquire a more fronted quality: [ɵ], [ʉ], or even [ʏ] or [ø]. Laryngeally tense syllables exert an effect on the CV string, particularly on vowel quality, but also, for example, /x/ realized as [χ], or closing the syllable glottally [ˀ]. The [v] component is a function of this particular /u

![]() / vowel pair, as discussed under Vowels.

/ vowel pair, as discussed under Vowels.

Vowels and register

The vowels of Northern Yi (or syllable rhymes) are characterized by both oral quality differences and laryngeal register quality. Laryngeal register is a distinction between ‘lax’ and ‘tense’ settings of the laryngeal constrictor mechanism (Esling & Edmondson Reference Esling, Edmondson, Braun and Masthoff2002), where lax is defined by an open or unconstricted epilaryngeal tube and tense is defined by a narrowed or constricted epilaryngeal tube. The lax/tense register distinction does not affect phonation type as much as it changes the resonance characteristics of the lower pharyngeal vocal tract. In terms of laryngeal ‘valves’, the mechanism for tense constriction in Yi is valve 3 – the aryepiglottic sphincter at the top of the epilaryngeal tube (Edmondson & Esling Reference Edmondson and Esling2006). There is not an appreciable difference in phonatory (vocal fold vibration) quality between the vowels of the two series. In terms of voice quality description, the pharyngeal resonance quality of the lax series may be described as ‘modal voice’ (or on a continuum between modal voice and breathy voice), and the voice quality of the tense series may be described as ‘raised larynx voice’ (Laver Reference Laver1980, Esling Reference Esling and Brown2006). There is, however, a difference in the oral articulation of the vowels of the two series. Both the difference in vowel quality and laryngeal register quality are marked on the vowels of the constricted ‘tense’ series, with the ‘Retracted’ diacritic /-/ marking tense phonemic status and the diacritic for ‘Retracted tongue root’ [

![]() ] under the phonetic symbol(s) for each tense vowel. The symbolization is meant to be equivalent, and either diacritic captures the parallel between Yi register and the retracted quality feature found in many other language groups (Edmondson et al. Reference Edmondson, Padayodi, Hassan, Esling, Trouvain and Barry2007). There are five pairs of vowels in Nuosu Yi – each pair with a lax and a tense counterpart. Three pairs span the vowel space, with the lax vowel closer in the vowel space and the tense vowel more open: / i

] under the phonetic symbol(s) for each tense vowel. The symbolization is meant to be equivalent, and either diacritic captures the parallel between Yi register and the retracted quality feature found in many other language groups (Edmondson et al. Reference Edmondson, Padayodi, Hassan, Esling, Trouvain and Barry2007). There are five pairs of vowels in Nuosu Yi – each pair with a lax and a tense counterpart. Three pairs span the vowel space, with the lax vowel closer in the vowel space and the tense vowel more open: / i

![]() /,/ ɯ

/,/ ɯ

![]() /, and /o

/, and /o

![]() /. Phonetically, the vowels tend to be long, or sometimes slightly diphthongized in the tense series, especially in citation form out of context: [iː

/. Phonetically, the vowels tend to be long, or sometimes slightly diphthongized in the tense series, especially in citation form out of context: [iː

![]() ], [

], [

![]() ː

ː

![]() ː], and [

ː], and [

![]() ː

ː

![]() ː]. It should be noted that the close vs. open specification of the lingual/mandibular setting for the vowels is exactly inverse to the open vs. narrow (constricted) specification of the laryngeal setting for the same vowels. The more open lingual vowels (towards the lower-right, retracted, corner of the vowel space) are those which have greater laryngeal constriction (Esling Reference Esling2005). There are two pairs of ‘fricativized vowels’. The /u

ː]. It should be noted that the close vs. open specification of the lingual/mandibular setting for the vowels is exactly inverse to the open vs. narrow (constricted) specification of the laryngeal setting for the same vowels. The more open lingual vowels (towards the lower-right, retracted, corner of the vowel space) are those which have greater laryngeal constriction (Esling Reference Esling2005). There are two pairs of ‘fricativized vowels’. The /u

![]() / set, which has also been represented as /v

/ set, which has also been represented as /v

![]() /, is used in the illustration of the consonant list (above), and the /z

/, is used in the illustration of the consonant list (above), and the /z

![]() / set is illustrated below. Thus, /

/ set is illustrated below. Thus, /

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() / can be regarded as the raised-larynx, tongue-root-retracted, epilaryngeal-tube-constricted counterparts of /i ɯ o

u

z/, respectively.

/ can be regarded as the raised-larynx, tongue-root-retracted, epilaryngeal-tube-constricted counterparts of /i ɯ o

u

z/, respectively.

Laryngoscopic video data

Nasendoscopic videos show the articulatory activity in the larynx for four minimal pairs to illustrate the lax/tense paradigm.

The five pairs of isolated vowels are also illustrated with nasendoscopic videos.

Vowel conventions

The vowels /u

![]() / are most often realized as labiodental fricativized vowels [v

/ are most often realized as labiodental fricativized vowels [v

![]() ] in combination with a close back vowel [ʊ] which is more reduced [

] in combination with a close back vowel [ʊ] which is more reduced [

![]() ] in the tense series than in the lax series. When this vowel occurs after bilabial and alveolar stops /p

pʰ b

mb/ and /t

tʰ d

nd/, it is accompanied by bilabial trilling [

] in the tense series than in the lax series. When this vowel occurs after bilabial and alveolar stops /p

pʰ b

mb/ and /t

tʰ d

nd/, it is accompanied by bilabial trilling [

![]() ʙ]. In our analysis of register quality, it is important to note that there are in parallel a laryngeal setting, a lingual feature, and a labial feature; thus, the labiodental fricative features and close back vowel quality of /u

ʙ]. In our analysis of register quality, it is important to note that there are in parallel a laryngeal setting, a lingual feature, and a labial feature; thus, the labiodental fricative features and close back vowel quality of /u

![]() / after bilabial and alveolar stops can be said to induce bilabial trilling in the syllable. Most significantly, the bilabial trilling tends to be more dominant in laryngeally tense syllables than in lax syllables, as shown in the narrow phonetic transcriptions. The occurrence of bilabial trilling in Nuosu Yi is important to document especially in light of Ladefoged & Everett's (Reference Ladefoged and Everett1996) contention that such sounds are phonetic rarities in the languages of the world. The vowels are placed in the raised (close back) corner of the vowel chart, to represent the [ʊ

/ after bilabial and alveolar stops can be said to induce bilabial trilling in the syllable. Most significantly, the bilabial trilling tends to be more dominant in laryngeally tense syllables than in lax syllables, as shown in the narrow phonetic transcriptions. The occurrence of bilabial trilling in Nuosu Yi is important to document especially in light of Ladefoged & Everett's (Reference Ladefoged and Everett1996) contention that such sounds are phonetic rarities in the languages of the world. The vowels are placed in the raised (close back) corner of the vowel chart, to represent the [ʊ

![]() ] quality of the lingual component. In bilabial nasals, the vowel assimilates to a nasal. The tense (constricted) context often has the effect of making the vowel sound more reduced (i.e. towards the retracted quadrant of the vowel chart).

] quality of the lingual component. In bilabial nasals, the vowel assimilates to a nasal. The tense (constricted) context often has the effect of making the vowel sound more reduced (i.e. towards the retracted quadrant of the vowel chart).

The front lingual fricativized /z

![]() / vowels are placed in the close front portion of the vowel chart, as the tongue position is between [i] and [ɨ] (although more apical). They are voiced alveolar fricative syllabic continuants, often with a schwa offglide. Their articulation is more open (approximated) than the usual fricative consonant [z] is understood to be; that is, they could be transcribed as [

/ vowels are placed in the close front portion of the vowel chart, as the tongue position is between [i] and [ɨ] (although more apical). They are voiced alveolar fricative syllabic continuants, often with a schwa offglide. Their articulation is more open (approximated) than the usual fricative consonant [z] is understood to be; that is, they could be transcribed as [

![]() ]. In Chinese phonetics, the traditional symbolic representation is [ɿ] (Karlgren Reference Karlgren1915–26). Following bilabial nasals or laterals, they assimilate to the consonant. Following retroflex consonants, they assimilate to a retroflex fricative. Following alveolo-palatal consonants, the syllabic fricative becomes a front rounded vowel in the lax series and a rhoticized central vowel in the tense series. The /z

]. In Chinese phonetics, the traditional symbolic representation is [ɿ] (Karlgren Reference Karlgren1915–26). Following bilabial nasals or laterals, they assimilate to the consonant. Following retroflex consonants, they assimilate to a retroflex fricative. Following alveolo-palatal consonants, the syllabic fricative becomes a front rounded vowel in the lax series and a rhoticized central vowel in the tense series. The /z

![]() / syllabic rhyme does not occur with the velar or glottal consonants. Some consonants may cause slight onset devoicing of the /z

/ syllabic rhyme does not occur with the velar or glottal consonants. Some consonants may cause slight onset devoicing of the /z

![]() / vowels, which may not always be noted in the narrow phonetic transcription. A similar situation applies for the retroflex pair /ʐ

/ vowels, which may not always be noted in the narrow phonetic transcription. A similar situation applies for the retroflex pair /ʐ

![]() /, which are voiced moderately retroflexed slightly-open (approximated) fricative syllabic continuants, often with a schwa offglide. They could be transcribed as [

/, which are voiced moderately retroflexed slightly-open (approximated) fricative syllabic continuants, often with a schwa offglide. They could be transcribed as [

![]() ]. In Chinese phonetics, the traditional symbolic representation is [ʅ] (Karlgren Reference Karlgren1915–26). The motivation for treating both fricatives as approximated versions parallels the principles expressed by Martínez-Celdrán Reference Martínez-Celdrán2004).

]. In Chinese phonetics, the traditional symbolic representation is [ʅ] (Karlgren Reference Karlgren1915–26). The motivation for treating both fricatives as approximated versions parallels the principles expressed by Martínez-Celdrán Reference Martínez-Celdrán2004).

Tones

There are three lexical tones in Nuosu Yi, 55 (high level), 33 (mid level), and 21 (low falling), whose pitch is basically the same in either register (lax or tense). There is a 44 (high mid level) tone sandhi realization, which often results from either tone 33 or tone 21 in syllable combination, for example, dza33 ‘food’ + dzɯ33 ‘to eat’ → dza44 dzɯ33 ‘to eat (food)’, and ndʐa33 ‘to examine’ + hɯ21 ‘to see’ → ndʐa33 hɯ44 ‘to test’. This tone sandhi also appears as a connector of phrases or clauses, for example, si44 and tɕo44, which occur in the narrative. Tone sandhi in Yi is complex. Generally speaking, if tone [44] appears as the first syllable of a two-syllable word or phrase, then it is very likely that this sandhi tone originally comes from tone /33/; for example, a44ʑi33 in the narrative, where the sandhi tone [44] is phonemically tone /33/. If it appears on the second syllable of a two-syllable word or phrase, then the sandhi tone might be originally tone /21/; for example, dʑz33kɯ44, where the sandhi tone [44] is phonemically tone /21/. In the case of emphasis, a classifier tone can be read as tone [44], for example, ma44, where tone [44] is originally tone /33/. For a detailed discussion of tone 44, see Lama (1991).

Transcription of recorded passage

The narrative is an unscripted telling of a picture story (a sequence of four visual images). The spontaneity of the task results in some hesitations, intonational phrases in short groups, and some disfluencies. The prosodic marker | indicates pauses between breath groups, and ‖ marks major intonation group boundaries. Each breath group is given a separate line in the phonemic/morphemic transcription. On occasion, /i/ can be reduced to [ɪ], and /u/ to [ʊ]. The lateral flap [ɺ] is a function of fast speech. Tones are first given phonetically, with tone sandhi changes shown as derived from their original form (33>44 or 21>44) in the phonemic transcription. Phrase-final creaky voice is marked phonetically.

Semi-narrow phonetic transcription

Phonemic forms and inter-linear morphemic gloss

Abbreviations used in the gloss: clsf = classifier; 3 = third person; poss = possessive; aux = auxiliary; pl = place; mkr = marker; pl = plural; p = person; V = verb; dsfl = disfluency; perf = perfective.

English translation

A boy with his two friends were watching an acrobat playing on the field.

The child was playing plates in his kitchen, mimicking what he saw after he finished watching the game and came back home.

But he was not so skillful to play acrobatics, and dropped all the plates on the floor.

When his mother came back home and saw all the smashed plates on the floor, she got angry and scolded her child.

Acknowledgements

The laryngoscopic research leading to the analysis of the laryngeal register series in Tibeto-Burman languages was carried out with the assistance of grants to the second author from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. We are grateful to Christopher Coey for enabling the IPA LS Uni phonetic font, to Victoria Simmerling for keyboard entry using the font, and to Philip Payne of Linguist's Software for creating the font with such extensive IPA symbol coding. We appreciate the comments of three anonymous reviewers in improving the clarity and accuracy of this paper.