I

The setting is a lavish, high-ceilinged, wood-panelled study in a Russian dacha near the town of Kuntsevo, close to Moscow. Evening has fallen, and a moustachioed man in black knee-high boots and a large grey overcoat removes a freshly pressed record from its paper sleeve. He opens his record player, sets his new disc in motion, and the opening bars of Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 23 in A major, K. 488, begin to sound. With a relaxed smile, he starts unbuttoning his overcoat, but quickly notices something unusual on the rug: a handwritten note, addressed to him, had unexpectedly slipped out of the record sleeve. Leaning on his desk for support, he bends to retrieve it. Straightening himself, he reads: ‘Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin, you have betrayed our nation and destroyed its people. I pray for your end and ask the Lord to forgive you. Tyrant.’ Stalin bursts into laughter, but soon his laughter turns to panic. His eyes widen. His hand desperately clutches the desk. Gasping for air, he collapses face-first onto the floor of his study and dies of a brain haemorrhage, while his two bodyguards stand motionlessly outside, too fearful for their own lives to investigate the sudden bang.

This is the story of how the pianist Maria Yudina inadvertently killed Joseph Stalin. It was her interpretation of Mozart’s concerto that accompanied his demise, and it was she who penned the note lambasting his dictatorship. It is a scene taken not from the history books but from Armando Iannucci’s 2017 lampooning black comedy The Death of Stalin. Footnote 1 As a fictional film, it makes no claims to complete historical accuracy, and Yudina’s role in the affairs leading up to and following Stalin’s death are grossly exaggerated: in the film, Yudina’s father and brother have been killed under Stalin’s regime, she is on personal terms with Nikita Khrushchev, she plays at Stalin’s funeral, and her note becomes wrapped up in the political machinations that ensue in the power vacuum left by the dictator’s death. All of these plot points, and the idea that Yudina had any role in Stalin’s death, have no basis in actual historical evidence. Indeed, the separation of fact from fiction in Yudina’s legacy has never been clean, something Elizabeth Wilson has probed in her recent illuminating biography of the pianist.Footnote 2

Instead, Yudina’s role in Iannucci’s comedy, however dramatized, prompts larger questions about the visibility of performers in histories of classical music. In a Soviet context, we might immediately wonder about the many paths that performers took in their attempts to navigate confusing and at times contradictory expectations in musical life, both under and after Stalin’s reign. I am also thinking more generally than that, because the history of music in the Soviet Union, as it is usually told, is no different to most histories of classical music, which, in the words of Nicholas Cook, ‘are really histories of composition’.Footnote 3 I will return to the many ways in which this point needs to be nuanced for much recent excellent work in Soviet music history. But for current musicology — a discipline in which the practice turn is nothing new and in which actor-network approaches have refigured the scope of historical research — this plea might seem outdated, even regressive. Georgina Born has pointed to limitations in the practice turn, arguing that the musicological ‘concern with performance can be a way of addressing the social in music without really addressing it’.Footnote 4 In Born’s diagnosis, musicologists such as Cook looked to ethnomusicology for a model of ‘a non-essentialist, non-notation-focused socio-cultural analytics of music’. But her vision was — is — more ambitious: for her, a cross-disciplinary social-theoretical stance makes possible ‘a macro-social analytics of music, bringing to the fore the large-scale political, economic, institutional and cultural processes that condition musical experience’, whereas the ethnomusicological model can (but does not necessarily) ‘fall back on overly micro-social, social-interactionist conceptions of musical practice’.Footnote 5

Similar broadening horizons occupy music history.Footnote 6 ‘Whatever music might be,’ writes Benjamin Piekut, ‘it clearly relies on many things that are not music, and therefore we should conceive of it as a set of relations among distinct materials and events that have been translated to work together.’Footnote 7 Drawing chiefly from Bruno Latour, Piekut adopts actor-network theory (ANT) and underscores the importance of casting the historical net widely: ‘By not deciding ahead of time what we are going to find in the world, we allow entanglements to emerge in all of their messiness.’Footnote 8 That is how he configures experimentalism, for instance, positioning it as ‘a network produced through the combined labour of composers, performers, audiences, patrons, critics, journalists, scholars, venues, publications, scores, technologies, media, a particular means of distribution, and the continuing effects of race, gender, class, and nation’.Footnote 9 Similar to Born (who is not an actor-network ‘theorist’), Piekut envisages an ANT approach to history as one that can move beyond the practice turn, the latter of which he explains through Carolyn Abbate’s rallying call for a form of music studies that centres the drastic sensation of musical performance.Footnote 10 ‘Although music’s drastic qualities lie beyond texts,’ Piekut argues, ‘a more expansive understanding of performance would complicate the isolatibility of the ineffable moment of musical performance.’Footnote 11 What this promises is a leap to a fully relational, emphatically social, and explosively distributed form of music history, one in which performance features among any number of other activities and materials that enliven musical networks.

A relational musicology would appear to have moved well beyond the need either to rethink the place of performers or attenuate the imposing figure of the ‘composer-hero’, to use Born’s words.Footnote 12 More than this, its sprawling agential scope makes the dualism of my initial musings seem hopelessly narrow, but I have two points to make to support what follows in this article. The first is that the practice turn — certainly of the Abbatean kind — has had relatively little impact on most music histories, which remain primarily concerned with composers. This is true, for instance, of Soviet music history, even recent examples of which are based around compositional practice, or the lives of composers, or the reception of particular musical compositions. And the second is that ANT approaches, in their move towards an ever-more-totalizing and empirically enriched construction of history, line performance up in a much longer list of actors and circumstances in a way that necessarily evacuates some of the gains of the practice turn in their move beyond it. I should stress Piekut’s own sensitivity to the contributions of performers in his work on experimentalism (David Tudor, Charlotte Moorman), though it is important that the terms of engagement there were at least in principle conditioned by a dismantling of traditional notions of composerly authority.Footnote 13 Retaining the gains of the practice turn may be more vital in contexts where such notions are more secure.

That is my intention in this article, the goal being to permit sustained attention to the work undertaken by a performer like Yudina — soon to return as this article’s protagonist — to make music happen. The simplicity of the word ‘work’ here massively belies the activities, time commitment, energy, and persistence necessarily involved in performing contemporary music in the Soviet ‘Thaw’, an arena in which she was central. I intend to highlight both the untrivial administrative labour required (such as sourcing scores and liaising with composers) and the specifically artistic demands and decisions bound up in actual acts of musical performance. The former I access chiefly through Yudina’s bountiful correspondence with key Soviet and international figures in these years.Footnote 14 The latter are more evasive, both ontologically and evidentially. But they are key components to studying performers in ways that do not perpetuate by now well-critiqued and yet remarkably resilient conceptions of musical performance as an iterative process, an act of presenting something that is, in substance, supposedly already there. For a history inclusive of performers, then, this means more than the recognition of their agency, and should, I argue, include a more active troubling of what Cook has called the paradigm of reproduction.Footnote 15 I share Piekut’s aim for ‘a more expansive understanding of performance’, but I am perhaps approaching it from a different (hopefully complementary) perspective.

What might it mean to try to refocus the intense palpability of musical performance and channel this through history? For a start, it would require paying attention to what John Rink straightforwardly refers to as ‘the work of the performer’, the purpose of which ‘must surely be not to reproduce the music, but rather to create it as if from scratch’.Footnote 16 This applies to all classical performance, but is perhaps especially recognizable in the domain of contemporary music, when compositions are often performed or heard for the first time. Anthony Gritten clarifies what is at stake by thinking through performance in McKenzian terms — as a challenge, namely ‘to enact this world as a performer, to cause transformations to happen, and to be part of the transformations’.Footnote 17 But Gritten also sharpens our sense of the nature of this work by calling attention to both ‘disciplinary exercises’ — in short, ‘all effortful activities that help the performer to come to terms with what the [musical] work requires for its performance’ — and the process of ‘ripening’, which characterizes the qualitatively different type of ‘energetic expenditure’ involved in the aesthetic event of music performance.Footnote 18 (He is thinking here of private practice and live performance respectively.) His reflections conjure images of bodily exigency, and I will return to them in my conclusion. Framed like this, there is nothing automatic about performing, nor in how performances come to happen. ‘Musical sounds’, as Abbate reminds us, ‘are made by labor.’Footnote 19

We can access Yudina’s artistic practice through her recordings, which form important components of both my case studies. Yet recordings themselves are no guarantor of such access, and I attempt here to fulfil Mine Doğantan-Dack’s wish that recordings ‘be recognised not merely as documents of performances that took place in some specific time and place, in one or several takes, but also as documents of the performer’s musical voice and expert knowledge’.Footnote 20 We must listen to recordings, but also listen through them. This requires the ‘virtues of close listening’ that Daniel Leech-Wilkinson has advocated, the corrective empirical supports that Cook has emphasized, and sensitivity to the kind of document any particular recording is.Footnote 21 And in considering Yudina’s correspondence and recordings together, my line of thinking picks up on one of Born and Andrew Barry’s criticisms of Latourian ANT: its empiricism does not, they argue, attend to the slippery relationship between discourse and practice (whereas such attention is, they contend, one of the strengths of anthropological ethnography). Simply put, ‘what occurs in practice and what humans say or write about this are not identical’.Footnote 22 I will argue here that performance studies can invigorate a model of music history that probes the relations between discourse and practice.

I said I would come back to Soviet music history, which acts as a stomping ground of sorts in which I put these larger aims to work with Yudina. As Boris Schwarz put it several decades ago, ‘composers speak on behalf of all Soviet music’: they constitute ‘the creative élite among musicians’ whose ‘privileged position has been preserved, and even enlarged, in the Soviet Union’.Footnote 23 Performers, he tells us, were excluded from the Union of Composers and thus have traditionally occupied a lower, less prestigious cultural rung.Footnote 24 His history reflects that hierarchy, and Patrick Zuk reminds us of just how influential Schwarz’s work has been: it ‘has not only shaped our view of the period, but also established the terms of engagement for much subsequent scholarship’.Footnote 25

Performers have not been wholly neglected, but they have existed on the margins, as Daniel Barolsky would put it.Footnote 26 For when it comes to the many ways in which composers navigated confusing and at times contradictory expectations in Soviet musical life, there is no shortage of illuminating research. Studies of Yudina’s one-time classmate Dmitri Shostakovich, to pick the obvious example, are a case in point: his life has been painstakingly investigated and furiously debated since Solomon Volkov’s now widely discredited memoir of the composer.Footnote 27 But the point also goes for studies with a broader purview than individual musicians. Much research of this kind has been concerned with rethinking the legacy left by Schwarz and contesting some of its historiographical imprints, especially the notion that the Soviet regime implemented a top-down, long-term, coherent policy of socialist realist ‘regimentation’ of musical life from 1932 onwards.Footnote 28 Zuk writes:

There is, moreover, a dearth of evidence to indicate that systematic attempts were made to coerce composers to write in any particular fashion, even if music couched in certain kinds of modernist idioms (such as dodecaphony) stood no chance of being published or performed for several decades.Footnote 29

By the same token, many have sought to nuance our understanding of what musical life in the Soviet Union was actually like. Marina Frolova-Walker’s groundbreaking study of the Stalin Prize, for instance, traces the evolution of socialist realist musical values; as she puts it, since ‘the Stalin Prize jurors avowedly attempted to shape the Socialist Realist artistic canon, we are able to see from their discussions not only which works were awarded but also why’.Footnote 30 Peter J. Schmelz uses the anthropologist Alexei Yurchak’s concept of vnye (literally, ‘outside’) to conceptualize the ambiguous place that new music held under the tenures of Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev.Footnote 31 And Pauline Fairclough’s pioneering work on the performance history of the Moscow and Leningrad Philharmonic orchestras during Stalin’s rule has persuasively recast our understanding of the kind of music that Soviet audiences were exposed to. In particular, she has challenged ‘the easy assumption that, after 1932, concert life in the years of High Stalinism constituted two decades of anti-Western, anti-modern, provincial and dull music-making dominated by socialist realism’.Footnote 32 The upshot is that official Soviet musical values were emergent rather than predetermined, and composers navigated a much less prescriptive aesthetic terrain than has often been assumed to be the case.

So far, performers have been largely incidental to this line of rethinking — though not entirely absent. Frolova-Walker includes an insightful chapter on performers and the Stalin Prize, while Schmelz’s book, though at heart a history of the generation of Soviet composers who came of age after World War II, pays testament to many of the performers (including Yudina) who played post-war new music.Footnote 33 Similarly, as Fairclough’s work is underpinned by reception studies, there is an obvious sense in which she engages directly with performance, but with a view to accessing how various composers and compositional styles, both contemporary and historical, were valued at the time. As Frolova-Walker notes, ‘reception studies are still most often focused on particular works, as in traditional musicology’, even if the concept of the musical work is refigured as ‘something mutable, subject to reinterpretation in each society that receives’ it.Footnote 34 These are observations, not criticisms, and one of the purposes of this article is to stake out a space in which performers are centred in these discussions.

What renders this somewhat more pressing is that Soviet performers, as Maria Razumovskaya has pointed out, have tended to be studied ‘as strategic commodities in the USSR’s wider propaganda machine’, if at all.Footnote 35 Such research is vital, of course, but what of performers as creative agents who were crucial to making contemporary music happen and implicated should certain works, composers, or styles suddenly fall into disfavour? There was, in this respect, a particular bravery to performers who opted to interpret and showcase contemporary music of any kind (whether western or Soviet), given the existence of a well-trodden lineage of ‘safe’ repertoire. After all, performers ‘often found themselves in more direct confrontation with authorities’ than composers did, as Schmelz reminds us.Footnote 36 Such performers are remembered and researched far less readily than the composers whose music they played. There are, of course, important biographical studies of some Russian performers, but these (as with most performer biographies) have ‘long stood outside the musicological arena’, to borrow Christopher Wiley and Paul Watt’s phrase.Footnote 37

Razumovskaya’s work on Heinrich Neuhaus is an important recent precedent. Neuhaus was by no means entirely compliant with Soviet cultural impositions: he continued to perform Nikolai Medtner’s music after it was banned in the 1930s and was openly critical of Soviet music composed under the banner of socialist realism.Footnote 38 As Razumovskaya has shown, he suffered grave consequences for the latter position in particular in 1941–42, when he was accused of anti-Soviet agitation, for which he was eventually convicted and expelled to one of the USSR’s restricted areas for more than two years.Footnote 39 Yet Neuhaus’s interest in new music did not extend to the more culturally off-limits repertoire of western modernism. As Razumovskaya notes, his stances ‘never seemed to cause [him] any significant political repercussions’, at least relative to the height of the Stalinist purges in the 1930s.Footnote 40 Yudina on the other hand was among the most ardent supporters and performers of avant-garde music in the Soviet Union. This support, coupled with her unwillingness to subdue her Russian Orthodox faith, led her to a position of deep marginalization in an atheistic state where ‘formalism’ in contemporary music was treated with official disapproval.

In what follows, I explore the years 1959–63 in Yudina’s life, tracing her fervent dedication to new music and how this came at great personal and professional cost. I first examine Yudina’s preparation for, premiere, and subsequent performances of the first Soviet twelve-tone composition, Andrei Volkonsky’s Musica Stricta: Fantasia Ricercata, in 1960–61. Second, I investigate Yudina’s advocacy of Igor Stravinsky and his music through her recordings of his piano works and her involvement in his repatriation in September 1962. I then conclude with Yudina’s visit to the Khabarovsk School of Music in March 1963, offering some thoughts both on what her experiences can tell us about performing in the Soviet cultural ‘Thaw’ and the wider music-historical implications of my study.

The ‘Thaw’ is the backdrop for this episode in Yudina’s life. The last five years of Stalin’s reign were conditioned, from a musical perspective, by Andrei Zhdanov’s 1948 ‘Resolution on Music of the Central Committee of the Soviet Union’, which chiefly condemned six Soviet composers (Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich, Aram Khachaturian, Nikolai Myaskovsky, Vissarion Shebalin, and Gavriil Popov) for their ‘formalist’ music. Their careers ‘were badly dented, their music no longer to be heard on concert platforms or seen at the printing presses, and their teaching positions lost or restricted’.Footnote 41 From that point onwards, too, musicologists ‘had to avoid all mention of Western influences on Russian music’.Footnote 42 Fairclough has argued that ‘Russian musical life was never again as limited as it was between 1948 and 1953’, pointing out that

compared with the dazzling internationalism of the late 1920s and the mid-1930s, Leningrad and Moscow Philharmonia programmes in the late Stalin era are marked by a dull conservatism, an extreme anti-western attitude towards most twentieth-century art, and a firm entrenchment of older western and Russian classics.Footnote 43

For Yudina, as Wilson remarks, ‘much was contradictory and paradoxical in those years’.Footnote 44 As a performer, she was closely associated with formalist tendencies, and she was barred from performing in Moscow for two years after Zhdanov’s resolution.Footnote 45 But shortly after this ban was lifted, Yudina was asked to travel to Leipzig and East Berlin as a member of a large Soviet delegation for a festival celebrating the two-hundredth anniversary of J. S. Bach’s death in 1950 — one of the rare occasions upon which she was permitted to leave the Soviet Union.Footnote 46 At the same time, Zhdanovshchina was also a much broader public campaign against ‘rootless cosmopolitanism’, a vector for what Frolova-Walker has called a ‘thinly veiled anti-Semitism’.Footnote 47 Yudina, a Jewish woman whose real musical sympathies lay with the ‘formalist’ tendencies of Western Europe’s avant-garde composers, was an obvious target, and her dismissal from the Moscow Conservatory in 1951 on the dubious grounds of lacking students is a conspicuous manifestation of this kind of discrimination.Footnote 48

Stalin died in 1953 and was succeeded by Khrushchev, whose reign ushered in the Soviet ‘Thaw’. His defining moment in power was perhaps his ‘Secret Speech’ in February 1956, in which the new leader acknowledged and denounced the horrors of his predecessor’s era. The ‘Thaw’ is typically associated with the totality of Khrushchev’s tenure, lasting from 1953 to his removal in October 1964, but as with the Stalin years, this designation can misleadingly suggest a kind of top-down coherence to cultural policy at that time. Schmelz is more specific than that: he has argued that due to ‘a general resistance to change within the system, the restrictive atmosphere provoked by the 1948 resolution persisted well into the next decade’.Footnote 49 Rather, it was ‘during the late 1950s and early 1960s’ that something ‘more critical and oppositional, however qualified, was possible’, even more so than in later years of the Thaw.Footnote 50 This period is bookended by the 1958 Declaration of the Central Committee on one side and the ‘Meeting of Party and Government Leaders with Writers and Artists’ on 8 March 1963 on the other. Schmelz calls the former the ‘real watershed moment for music’, which finally ‘amended and canceled’ the 1948 resolution, while the latter saw Khrushchev denounce ‘cacophony in music’ in a direct attack on twelve-tone techniques.Footnote 51

I mentioned that Schmelz uses the Russian word vnye to characterize the ambiguity and ‘outsideness’ of the unofficial musical circles that sprang up and began to explore ‘formalist’ compositions in this period. ‘This music was criticized throughout the 1960s because it did not fulfil official socialist realist requirements,’ writes Schmelz, ‘yet it was not, strictly speaking, illegal to perform it.’Footnote 52 He elaborates:

After the May 1958 declaration that revoked the 1948 resolution, a broader range of works by Soviet composers became available. This restoration of the musical past was the true beginning of the Thaw in music, as it also allowed more pieces by a wider range of domestic and foreign composers to be heard […] The works of the leading European modernists, the scores of Schoenberg and other composers of serial music, continued to be officially condemned and their access restricted into the 1960s, but, like the outlawed literature, they were available through a variety of other channels, from official Soviet sources to visiting foreign musicians and composers.Footnote 53

Yudina had played the music of the likes of Arnold Schoenberg, Paul Hindemith, and Igor Stravinsky in the 1920s and 30s, but it was from the late 1950s onwards in particular that she intensified her commitment to new music.Footnote 54 In 1958, she began to record much more twentieth-century music than she had previously, reflecting her newly sharpening musical priorities.Footnote 55 And in 1959, she connected with Pierre Souvtchinsky, an acolyte of Stravinsky with whom she built up a rich and wide-ranging correspondence from September onwards.Footnote 56 She was put in touch with Souvtchinsky by Boris Pasternak, and through Souvtchinsky she learned more about, acquired the scores of, and personally contacted many western composers around the turn of the 1960s. Their correspondence was especially frequent until 1963, and it was through these exchanges that many of Yudina’s aesthetic values were elaborated, negotiated, and shaped. ‘I will say (and I have gradually come to this conclusion)’, wrote Yudina to Souvtchinsky on 27 May 1960, ‘that music which is old (and still immense, like Schubert, Mozart and so on) is no longer “ours”, as Stockhausen put it; I can play it, but I only want to explore new or little-taken routes…’.Footnote 57

This rhetoric reverberates through her other letters in this period. It undergirds her correspondence with Stravinsky and is a feature of her exchanges with like-minded composers in the Soviet Union. In a letter to Volkonsky of 22–23 December 1960, Yudina wrote that she was playing the music of ‘Stravinsky, Hindemith, [Ernst] Krenek at all costs’ and was desperately trying to keep up with developments in serialism, mentioning Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Olivier Messiaen by name.Footnote 58 And months later, she wrote to Arvo Pärt:

I must admit that even the greatest of old music is nothing more than a museum to me […] but to play among the people and for the people can be done only in the language and tension of this era, and if it involves the music of your compatriots, even better.Footnote 59

All of this is to say that the period that Schmelz identifies as of greatest possibility for those with ‘formalist’ tendencies was that within which Yudina was most active as a performer of contemporary and avant-garde music. And because Yudina was so determined to perform new music up to and including the likes of Messiaen, Boulez, and Stockhausen, she is exceptionally useful for exploring the limits of vnye for performers in this volatile period.

II

I begin in earnest with Yudina’s first letter to Souvtchinsky, of 16 September 1959. ‘With the humility of an elderly person who doesn’t have long to live’, Yudina wrote, ‘I beg you to send me certain new works — I should say — scores’, naming compositions by Stravinsky, Boulez, Anton Webern, and Bohuslav Martinů and offering to pay Souvtchinsky ‘whatever the amount’ they would cost.Footnote 60 On 21 September, Souvtchinsky replied enthusiastically, providing Yudina with the addresses of Messiaen, Boulez, and Stockhausen so that she could write to them personally.Footnote 61 He followed this up with a package on 30 September containing ‘the scores of Boulez and Stockhausen’, promising to send on ‘the music of Stravinsky, Webern and Messiaen’ in due course.Footnote 62 A new musical vista thus opened up for Yudina, though the transferral of this music was not straightforward, and she immediately worried for its secure passage. Writing to Souvtchinsky on 10 October, she noted that she had not yet received the music: ‘If the package of music by Boulez does not arrive, this will mean that it will be necessary to avoid sending anything by post from now on, and to privilege more favourable options.’Footnote 63 Yudina was thankful when the package arrived a few days later, but evidently the vagaries of international post weighed on her mind.Footnote 64

Yudina was eager to convey her enthusiasm for these western composers, but she was equally concerned with highlighting some of the achievements of Soviet composers, particularly the young Andrei Volkonsky.Footnote 65 As might be expected of a close friend of Stravinsky, however, Souvtchinsky was dismissive of Soviet music, though he was not familiar with the young Volkonsky.Footnote 66 Yudina singled him out for praise: ‘He is very talented and extraordinarily cultured […] Among the young and relatively young, no one else, I believe, comes to mind.’Footnote 67 And no doubt eager to inform Souvtchinsky that Soviet composition could keep up with western developments, she informed him that Volkonsky was ‘currently writing twelve-tone music’.Footnote 68

Yudina, then, saw Volkonsky as a herald of sorts for a new era of Soviet avant-garde music, and his Musica Stricta: Fantasia Ricercata for solo piano ‘is usually acknowledged as the first Soviet twelve-tone composition’.Footnote 69 Volkonsky composed the work in 1956–57 and subsequently dedicated it to Yudina, and though he performed it himself for a small affair in late 1957 or early 1958, it was Yudina who gave the public premiere in the Gnessin Institute on 6 May 1961 — an event that Schmelz designates as the beginning of ‘postwar Soviet New Music’.Footnote 70 Yudina is thus inextricably bound up with this beginning, and Musica Stricta is a key example of the great efforts incumbent on her as a performer to make new music happen, her creative authority over that music, and the repercussions she faced for performing it.

As the three-year gap between Volkonsky’s completion of the manuscript and Yudina’s first performance indicates, securing an official premiere proved difficult. In a letter to Pierre and Marianna Souvtchinsky written from 13 to 19 March 1961, Yudina informed them that the first performance was scheduled for 26 March.Footnote 71 But we know from Yudina’s first letter to Souvtchinsky that she had been learning Volkonsky’s music ‘systematically’ since before September 1959, and this no doubt included Musica Stricta. As well as this, Yudina had clearly held the score in her possession for some time: ‘Don’t blame me for disappearing with your marvellous manuscript!’ she wrote to Volkonsky on 22–23 December 1960.Footnote 72 She certainly hoped to perform it on a planned trip to Paris, as a prospective set of programmes in her letter to Souvtchinsky of 10 March 1960 indicates.Footnote 73 It is telling that Yudina was seeking at this stage to debut Volkonsky’s work in France; if she had been trying to perform Musica Stricta in Moscow or Leningrad up until that point, her efforts had clearly been frustrated. Ultimately, the Parisian route met the same fate: after corresponding with the composer André Jolivet, whose Concerto for Piano she was invited to perform there, Yudina was denied permission to travel.Footnote 74 She told Volkonsky:

I was intending to play this work [Musica Stricta] in France, because besides performing Jolivet’s Concerto I was invited to give two programmes of my choice on the radio. […] Three weeks ago it became apparent that our Minister had cancelled my trip. I rang Paris — they intend to ‘attack again’, but for now everything still belongs to the ‘world of the uncertain and the unresolved’!!Footnote 75

No doubt the delay also stemmed from other difficulties Yudina was encountering at the time. In the same letter to Volkonsky, she wrote about the obstacles she was facing to rehearse the twelve-tone and serialist repertoire she wanted to work on:

As for Boulez and Stockhausen, I don’t have time to learn them for the moment, nor even to look at them. I don’t even have time to sleep, because as soon as a good new work for two pianos presents itself, we have to rehearse by night, because, as you know, I’ve been dismissed from the [Gnessin] ‘Institute’ precisely because of the new music […] so we rehearse in different settings and at crazy hours.Footnote 76

Yudina, as she mentions here, was sacked from her professorship at the Gnessin Institute on 1 July 1960, in large part because of her commitment to new music.Footnote 77

Programming Musica Stricta — or any new music — seemed necessarily to invite struggle. In a letter to the German musicologist Fred Prieberg of 21 January 1962, Yudina informed him of how she went about curating her programmes when requested to give concerts: ‘I always say: “it’s like this, and this alone!”, and I remind them that “I have dedicated my life to contemporary music” and, thank God, in 80% of cases I get my way!’Footnote 78 Given that the choice of repertoire was negotiated between concert organizers and performers, the burden inevitably fell on the latter to advocate for the living composer in question. The larger point is the effort involved here: between smuggling in scores of western composers, trying and failing to go abroad to perform, negotiating with official Soviet venues to secure permissions, and rehearsing at inconvenient times, Yudina faced considerable difficulty in bringing this music to the stage.

Then there is the work of performing. It might seem curious that Yudina would end up premiering Musica Stricta in the very institution that had recently let her go, but as Wilson notes, Yudina’s dismissal ‘had been orchestrated by the Ministry of Culture’ against the wishes of Yuri Murmantsev, the director of the Gnessin Institute.Footnote 79 And so, on 6 May 1961, in a recital which also consisted of Bach, Hindemith, and Bartók, the premiere of Musica Stricta finally took place. Yudina performed it twice after the interval to an audience that was deeply curious and enthusiastic about the prospect of this new music.Footnote 80 Several subsequent performances quickly followed, including in Leningrad at the Concert Hall at the Finland Station on 11 May and at the Leningrad House of Composers on 12 May. As Schmelz has pointed out, Musica Stricta was disguised on the programme at the second Leningrad concert, identified only as ‘Fantasia’.Footnote 81 Perhaps inevitably, the work began to pick up negative reviews, as in Sovetskaya muzïka in July 1961.Footnote 82 But Yudina continued to perform it alongside other contemporary music by the likes of Stravinsky, Hindemith, and Witold Lutosławski.

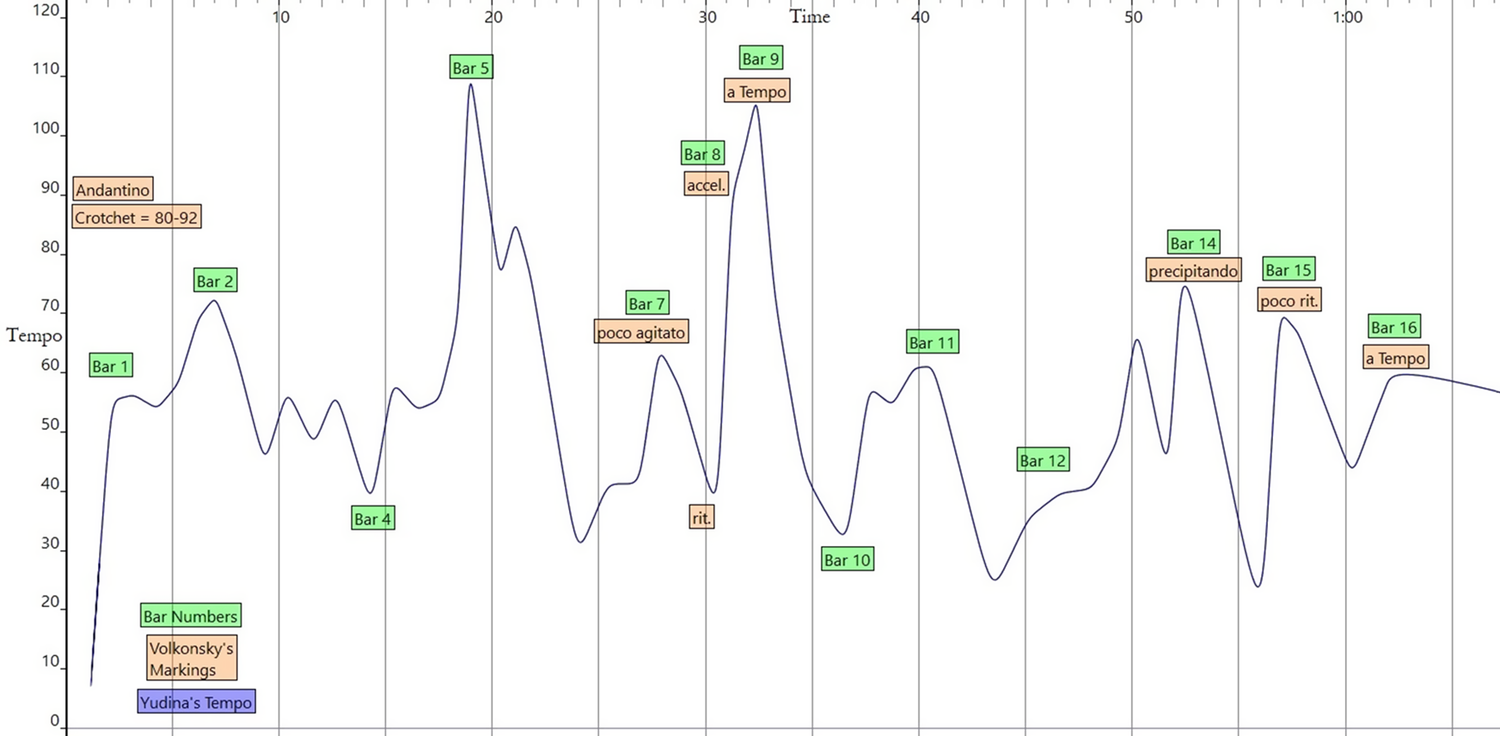

A live recording has recently been released of Yudina performing this work on an unspecified date in 1961 at the Scriabin Museum, and this of course opens up a crucial window onto her musical contributions.Footnote 83 I examine here her approach in the opening of the first movement of Musica Stricta, the first eight bars of which appear in Example 1. The tempo marking of ♩ = 80–92 leaves room for flexibility, but Yudina’s approach is much looser than this: she begins more slowly and varies the tempo freely, rushing in bars 2 and 7 and speeding up considerably in bar 5. The only marked tempo increase on the first page is at bar 8, but here Yudina continues to speed through the ‘a Tempo’ marking in bar 9. Figure 1 gives a bird’s-eye view of her tempo in the first sixteen bars, alongside Volkonsky’s relevant markings. As well as simply verifying the fluctuations, it also confirms something else that we hear: that there is no trace of Volkonsky’s suggested tempo in her interpretation, which instead meanders around the region of 40–70 bpm, never settling. Something similar could be said of Yudina’s dynamics: at bars 5, 7, and 13, for instance, she ignores Volkonsky’s directions, playing loudly rather than attending to the subtleties of his hairpins and p and mp markings. This seems to be true of Yudina’s other performances too: Schmelz has documented (through eyewitness accounts of the first public Musica Stricta performance) how Yudina ‘took liberties with [Volkonsky’s] dynamic markings’ and that even the composer commented ‘on the numerous wrong notes in her performance’.Footnote 84

Example 1. The first movement of Volkonsky’s Musica Stricta, bars 1–8. © M.P. Belaieff Musikverlag. Reproduced by permission. All rights reserved.

Figure 1. Representation of Yudina’s performance of the first movement of Musica Stricta, bars 1–16.

There is, in other words, nothing neutral about Yudina’s performance here: her lurching tempos and jagged dynamics bounce the listener from one extreme to another in what comes across as an especially provocative interpretation of Volkonsky’s score, one perhaps intending to shock or astonish those in attendance. This requires some qualification, not least because I am to an extent describing aspects of Yudina’s interpretation that are more general hallmarks of how she liked to perform: powerful dynamics, a heavy touch, and fluctuating tempos can be found on many of her recordings (especially of live performances). She was a notoriously idiosyncratic pianist, but the circumstances here are important. First is the very fact that she was performing Volkonsky’s work at all, rather than, say, something by Beethoven. Second is the venue: the Scriabin Museum, as Schmelz notes, for many years ‘fell “outside” — vnye — official jurisdiction due to the laxity of those ostensibly responsible for its oversight’.Footnote 85 Schmelz here is referring to the electronic music studio that was founded in 1966, but Yudina’s performances of Webern and Volkonsky there indicate that it functioned as an outside space before that. In such a venue, Yudina’s interpretative approach takes on a particularly exciting flavour. Third, Yudina had a habit of reading the out-of-favour poetry of Boris Pasternak and Nikolai Zabolotsky at her recitals, including those at the Scriabin Museum.Footnote 86 As she revealed to the Souvtchinskys, she would read these ‘at the end of her concerts as a kind of “encore”’:

Lots of listeners are very happy and approve; lots are ‘horrified’ because ‘it is not done’… But I intend to work the ground and establish the right, or at least the possibility, to break down the barriers facing soloists… We’ll see.Footnote 87

To dramatically read such poetry was thus intentionally provocative in ways that politically intensified her musical performances.

But there is a fourth reason, one that requires a little more explanation but which sets my argument against a larger empirical backdrop. Yudina’s interpretation of Musica Stricta noticeably breaks from the kind of performance tradition that came to represent the aesthetics of the post-war avant-garde and the Darmstadt School in particular. This aesthetic, as Cook has shown, is exemplified by the recording history of Anton Webern’s Piano Variations, op. 27. Though this work was composed in 1935–36 and published in 1937, the intervention of World War II meant that it was not established as part of the concert repertoire until the 1950s — a context which, as Cook says, was ‘very different in its aesthetic assumptions and performance practices from those of pre-war Vienna’.Footnote 88 It was then that quite a different image of Webern was consolidated by the Darmstadt avant-garde, one which championed ‘a highly selective, scriptist, even fundamentalist appropriation of Webern’s music’.Footnote 89 There were nevertheless those who argued that this idea of Webern was a wrong-headed reimagining, chief among them the pianist Peter Stadlen, who was coached by Webern when the composer was still alive and whose 1948 recording captures a pre-war, or perhaps pre-Darmstadt, conception of Webern performance.

Cook builds on Miriam Quick’s observation that there were ‘in the late 1940s, 50s and 60s […] not one but two Webern performance styles: the Viennese tradition and the avant-garde “Darmstadt” practice’.Footnote 90 He shows there to be considerable continuity between these styles, but broadly confirms the existence of two separate camps before their eventual convergence towards the end of the 1960s. The pre-war style was characterized by ‘slow tempos, the rather disjointed B section […] and the noticeably more tranquil playing of the A2 section’, whereas pianists in the Darmstadt style shared certain common features — such as fast tempos and what Cook calls a ‘quality of understatement’ — but on the whole are best described as having ‘distanced themselves from the overtly expressive playing inherited from the pre-war years’.Footnote 91 (The first movement is in a straightforward ternary shape: A1BA2.)

All of this matters because Yudina often programmed Webern’s Piano Variations alongside Musica Stricta at these recitals. Her exposure to his music came in early 1960, when she had the chance to listen to a record with Volkonsky.Footnote 92 As she wrote to Souvtchinsky in March 1960:

And now most importantly: lately, I managed to listen to a number of works by Anton Webern on record, in good condition, with a music lover passionate about this composer. We listened to everything once up until his Op. 16 (the Concerto which you sent me, thanks!) starting at the beginning, and we intend to continue with the rest soon. Piotr Petrovitch [Souvtchinsky]! For a few days, I was fascinated, shaken, devastated and resuscitated all at the same time. It seemed to me that the music had arisen in my heart like a spring, a key, a path towards Eternity…Footnote 93

Which record was she listening to? Collot has identified it as a Columbia Masterworks release from 1957 containing the complete music of Webern under the direction of Robert Craft. Among the tracks listed is Leonard Stein’s 1954 recording of the Piano Variations, a significant inclusion given that, as Cook put it, his performance ‘is generally seen as epitomising Darmstadt literalism’.Footnote 94 But Yudina’s interpretation of the Piano Variations is nothing like Stein’s. Overall, her performance is a slow one (clocking in at 2 minutes 4 seconds), her middle section reaches larger extremes in comparison to the outer material, and her interpretation of A2 is more subdued than A1, especially in the respective opening bars.Footnote 95 Instead, the range of general characteristics that Cook describes of the Stadlen tradition maps onto Yudina’s performance.Footnote 96

A simple explanation would be that Yudina, as a pianist of an older generation to Stein, embodied a pre-war performance style. But she also espoused the values of modernist discourse in relation to new music — most clearly, as we shall see, in connection with Stravinsky — and was certainly capable of performing in a more expressively frugal manner. Not all of her recordings traverse such extremes. And so the difference between Yudina and, say, Glenn Gould (who performed the Piano Variations in Moscow in 1957) was not just that they were pianists from different generations — one vitalist, the other geometrical, as Richard Taruskin might have put it — but that to perform Webern in Russia meant different things to them and their respective audiences.Footnote 97 The composer Boris Tishchenko, who heard both Gould and Yudina perform in these years, put it like this: ‘Maria Venyaminovna also played Webern’s Variations — here one could talk of “perpendiculars” — Gould’s performances were transparent and crystal-clear — Yudina’s active and protesting!’Footnote 98 This certainly chimes with Yudina’s professed attempts ‘to break down the barriers’ in reading Pasternak and Zabolotsky at her recitals.

Repercussions lay in wait. On 19 November 1961, Yudina performed both Musica Stricta and the Piano Variations in the Small Hall of the Leningrad Philharmonia, a venue staunchly within the realm of officialdom in a city that was ‘not as open as […] Moscow in the post-Stalin years’.Footnote 99 Recalling the event in 1970, not long before she died, Yudina wrote:

When the public ostensibly refused to leave at the end of my concert in the Glinka Small Hall, and I had already come back several times to play encores, I returned to the stage once again and… everyone was still seated!! ‘What, you’re still here?’ — I ask; and then they all start clapping! So, I tell them: ‘In that case, I’m going to read you some poetry’. […] I read ‘Yesterday Reflecting upon Death’ by Zabolotsky and ‘Lessons of English’ by Pasternak, and another burst of applause ensued. But the stupidity and vengeful spirit of someone in the audience earned me a ban on giving concerts in Leningrad.Footnote 100

Even if we allow for a certain amount of retrospective embellishment in her account, what is certain is that Yudina’s performance earned her a permanent ban from the Leningrad Philharmonia — she did not perform in concert there again.Footnote 101 In that sense, Yudina’s Volkonsky and Webern were verifiably provocative, because at least someone in the audience that night reported her performance to the authorities. This pays testament to her precarity as a performer: encores were a common means of pushing boundaries in ways that went undetected, but one displeased individual held the power to reassert those boundaries retrospectively.Footnote 102 While Yudina succeeded in giving a few further performances of Musica Stricta after 19 November, from 1962 Volkonsky’s music became — in the composer’s own words — ‘definitely banned’.Footnote 103

III

Yudina valued Volkonsky highly among young Soviet composers in particular, but in her mind Stravinsky’s musical achievements ranked above all others in the twentieth century. She spoke of him with an almost religious sense of devotion, one which grew as she began receiving his scores, performing his music more regularly, and corresponding with him directly. This devotion culminated in (and was forever ruptured during) Stravinsky’s historic return to Russia to mark his eightieth birthday in September 1962, an event to which Yudina made important contributions that have only recently been acknowledged.Footnote 104 It was Souvtchinsky who provided the link between them: as Tamara Levitz notes, the correspondence between these three figures ‘documents Stravinsky’s first tentative contact with Soviet colleagues during the Thaw’ in what would culminate in his first return to Russia ‘after almost half a century’.Footnote 105

Stravinsky’s music featured heavily on Yudina’s list of requests from Souvtchinsky in her first letter to him of 16 September 1959, in which she asked for the scores of his Piano Sonata, Elegy for Solo Viola, and the Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments.Footnote 106 On 30 September, Souvtchinsky replied that he would soon send on the requested scores and that he had passed Yudina’s kind words on to the composer, adding that Stravinsky ‘reacted warmly and showed great interest in [Yudina’s] letter’.Footnote 107 Thus began a huge influx of Stravinsky’s music into the Soviet Union via these channels, though not always successfully: that same month, Stravinsky sent Yudina a package of his scores from London, but their non-arrival became apparent only when Souvtchinsky asked Yudina why she hadn’t yet acknowledged them: ‘I have just received a letter from Stravinsky. He is very surprised (and worried) not to have received confirmation from you that the scores he sent from London in September arrived safely.’Footnote 108 She telegrammed Stravinsky on 19 February 1960 to inform him of the bad news that the scores had never reached her.Footnote 109 Souvtchinsky resolved to ask Stravinsky that the composer should send him any and all scores, which Souvtchinsky would then pass on to Yudina himself.Footnote 110 This happened very quickly: ‘I just received 28 (!) scores’, Souvtchinsky wrote to Stravinsky on 22 April 1960, ‘which I will start sending to Yudina.’Footnote 111

Right from the beginning of Yudina’s correspondence with Souvtchinsky, then, he and Stravinsky made concerted efforts to export the latter’s music into the Soviet Union for Yudina to distribute and perform. Yet such an activity was by no means a safe one for Yudina, even in the ‘Thaw’, and it contributed directly to her dismissal from the Gnessin Institute in the summer of that year. One of those who denounced her, the music theorist Pavel Kozlov, claimed that ‘her propaganda of composers of an evidently anti-Soviet nature, such as Jolivet and Stravinsky, is completely out of place in a musical-pedagogical Institute’.Footnote 112 So performing Stravinsky was certainly a risk, though one that Yudina gladly shouldered. In a letter from 29 April 1960, she told him that ‘before you, I turn into a shy schoolgirl’, and that ‘the very thought of being in contact with you seemed to me […] inconceivable, and this feeling has not left me for a long time’.Footnote 113 Quite simply, she considered Stravinsky to be a genius. Scanning her lengthy letters to him, virtually at random, reveals quotations like the following:

If I were without arms, without legs, without eyes, like many victims of war, if I were subjected to the strict discipline of a remote monastery, if for the good of future generations, I suffered in a burning desert or in icy lands, then no doubt I would have experienced something that is inaccessible to you, but it is not so, and I cannot help but remain silent, I who am only your pupil!Footnote 114

In the same letter, Yudina raised an even more tantalizing prospect with Stravinsky: ‘I desperately want you to come and visit us [in the Soviet Union].’Footnote 115 Thus the seeds for Stravinsky’s repatriation were sown, at least in the composer’s mind. Yudina brought it up with Souvtchinsky too, and both men seemed to see Yudina as the key figure through which to rehabilitate Stravinsky’s reputation in his homeland, both by performing his music and lobbying for his return. As Souvtchinsky put it to Stravinsky, ‘Perhaps M. V. Yudina’s appearance is providential.’Footnote 116 At least at this stage, both men were as unaware of Yudina’s unfavourable position in the Soviet musical scene as they were of ‘the courage she displayed in disseminating his music’, as Levitz puts it.Footnote 117

Yudina frequently updated Stravinsky on her performances of his compositions and sent him programmes of her concerts, telling him, ‘I strive to play your works as often and as well as possible, to make them known to others.’Footnote 118 But relations also became strained. He disappointed Yudina by informing her that he wouldn’t make the trip in 1961, and she became exasperated with his unhelpful pronouncements upon Soviet musical life.Footnote 119 In an interview with the Washington Post in December 1960, Stravinsky spoke very critically of music in the Soviet Union:

They’re bad. Poor Shostakovich, the most talented, is just trembling all his life. Russia is a very conservative and old country for music. It was new just before the Soviets. Under Lenin they invited me. I couldn’t go. Stalin never invited me.Footnote 120

His negative remarks were reported in Sovetskaya kul’tura in February 1961, and Yudina wrote to Souvtchinsky to demand an explanation:

About two or three weeks ago, it was reported in Sovetskaya kul’tura that Igor Fyodorovich had made extremely negative comments about us, the Soviet Union, that he declared that ‘over there, there is no culture or cultured people, neither in music, in interpretation, in choreography, or in anything’. […] I can’t be certain whether or not Stravinsky truly said this […] [but] if it turns out after all that I. F. said something of this sort, then why, why?!Footnote 121

As well as finding these comments offensive — after all, she valued much contemporary Soviet composition and was in many ways proudly nationalist — Yudina felt them to be fundamentally detrimental to securing the composer’s official return, and she didn’t know how to proceed.Footnote 122 Tensions rose further in Souvtchinsky’s response. He informed Yudina that, when it came to Stravinsky’s disagreements with Soviet composers, he was entirely on his side.Footnote 123 But more critically, he gave Yudina a musical command of sorts:

This is why it is necessary and indispensable, whatever happens, that you don’t stop playing Stravinsky throughout Russia. Writing to I. F., or involving him in polemical discussions, makes no sense; that would be bad. What matters is the playing, the playing, the playing. […] Writing to him in general terms is something to be avoided. We must be grateful and only grateful to him, and we must rejoice in the fact that we live at the same time as him on this Earth.Footnote 124

In other words: don’t talk, just play. This is a crucial intervention, one which sets into relief the one-sided dynamic to Souvtchinsky’s and Stravinsky’s relations with Yudina. Yudina’s counsel is dismissed, and she emerges more conspicuously as a useful outlet for the composer’s work.

At the same time, Yudina was preparing to record Stravinsky’s music. Unsurprisingly, her adulation was matched by an anxiety to do justice to his music in performance, and her letters indicate that her sense of responsibility was especially acute in the studio. Telling in this respect is the protracted process through which she recorded his Piano Sonata and his Serenade in A major. Though Stravinsky composed these works in the 1920s, Yudina received a copy of the score of the Sonata from Souvtchinsky only in December 1959 and, it seems, started learning the Serenade around November of the following year.Footnote 125 As we shall see, she wouldn’t begin putting them on tape until the end of 1961.

On 13 July 1961 — just under a month after Stravinsky’s formal invitation to the Soviet Union — Yudina wrote to the directors of Melodiya’s recording studios to complain about their facilities, citing external noise, poor hygiene conditions, and sub-par instruments:

Both of the instruments were practically out of tune. At a pinch, they could be used for pieces with pedal, which would conceal their complete lack of timbre. Impossible to record Stravinsky in these conditions, because the music is transparent, in some places the music is only written for two voices, the defects of the instrument are glaring, the non-existent timbre doesn’t help, in particular in the Sonata, but in large part as well in the Serenade. Footnote 126

Yudina used these reasons as excuses not to record the Sonata and Serenade in the summer, but her dissatisfaction with the studio conditions was not the whole truth behind the postponement. Almost a month later, on 6 August, she informed Souvtchinsky that she was encountering phrasing problems with both compositions and that she desperately sought clarification from the composer.Footnote 127 In other words, she was grappling with specifically musical questions.

Yudina’s letters indicate how heavily this burden of interpretation weighed on her mind. On 13 September, she attempted to bypass Souvtchinsky by sending a telegram directly to Stravinsky in Helsinki:

Please let me know your address for September and October so that I can write a detailed letter to you because, among many other things, I must bother you with questions related to the performance of the Sonata and the Serenade because I have to make this recording and I wish to play exclusively following your conception.Footnote 128

Her telegram missed Stravinsky by about three hours, and an increasingly agitated Yudina wrote to Souvtchinsky to implore him to pass on her original message to the composer.Footnote 129 She also asked them to send her ‘the places where he will be staying and the dates’ so that she could write to him afterwards.Footnote 130 At the start of December, Yudina still had yet to record the Sonata, but she mentioned to Prieberg that the recording session was imminent.Footnote 131 And on 26 December, she informed the Souvtchinskys that she had ‘just recorded [the Serenade], but without having been able to exchange questions and answers with Stravinsky, I simply had to record it in 1961, and I waited until the very last minute, or rather, the studio waited for me!’Footnote 132

Perhaps Yudina was compelled to record these works by the end of 1961 at the very latest and did her best to stall until she could incorporate Stravinsky’s thoughts. The answers she desperately sought never materialized, and on 30 April 1962 Yudina attempted to address these worries to the composer:

I will not share with you my conception of [the Serenade], but you should know that I have forged my own interpretation (yes, I allowed myself!!) beyond that which you may have said about it… I play it, it seems, in a rigorous way. It wasn’t possible to wait any longer for your advice or postpone the recording date, you were on tour for too long.Footnote 133

Yudina is hedging here. On the one hand, she describes her interpretation as ‘rigorous’, a quality she elsewhere associated with the composer and which resonates with Stravinsky’s outspoken, ethically charged demands that performers of his music be ‘executants’ rather than ‘interpreters’.Footnote 134 On the other, she is anticipating and attempting to excuse any aspects of her recording that might not be to his liking. Both of these currents run through her subsequent correspondence about these works, as when she discovered that there were printing errors in the scores she had been using. ‘Alas, I didn’t get the chance to correct the printing errors in Stravinsky’, she wrote to the Souvtchinskys. ‘I hope that they won’t disfigure his thinking too much. I absolutely do not understand how, with his demand, his rigour and his sense of detail that he let slip such misprints and why the editors don’t have more control.’Footnote 135

There is an obvious discourse of fidelity at play, but the point worth emphasizing is just how laborious this burden of fidelity was: Yudina negotiated with Melodiya, postponed recording sessions, and wrote repeatedly to both Stravinsky and Souvtchinsky with her musical concerns, all in the name of this faithfulness. One could argue that the drawn-out nature of this process was self-inflicted, but that would be to underestimate the sheer aesthetic — or perhaps ethical, to follow Stravinsky’s philosophy — importance of getting things right.

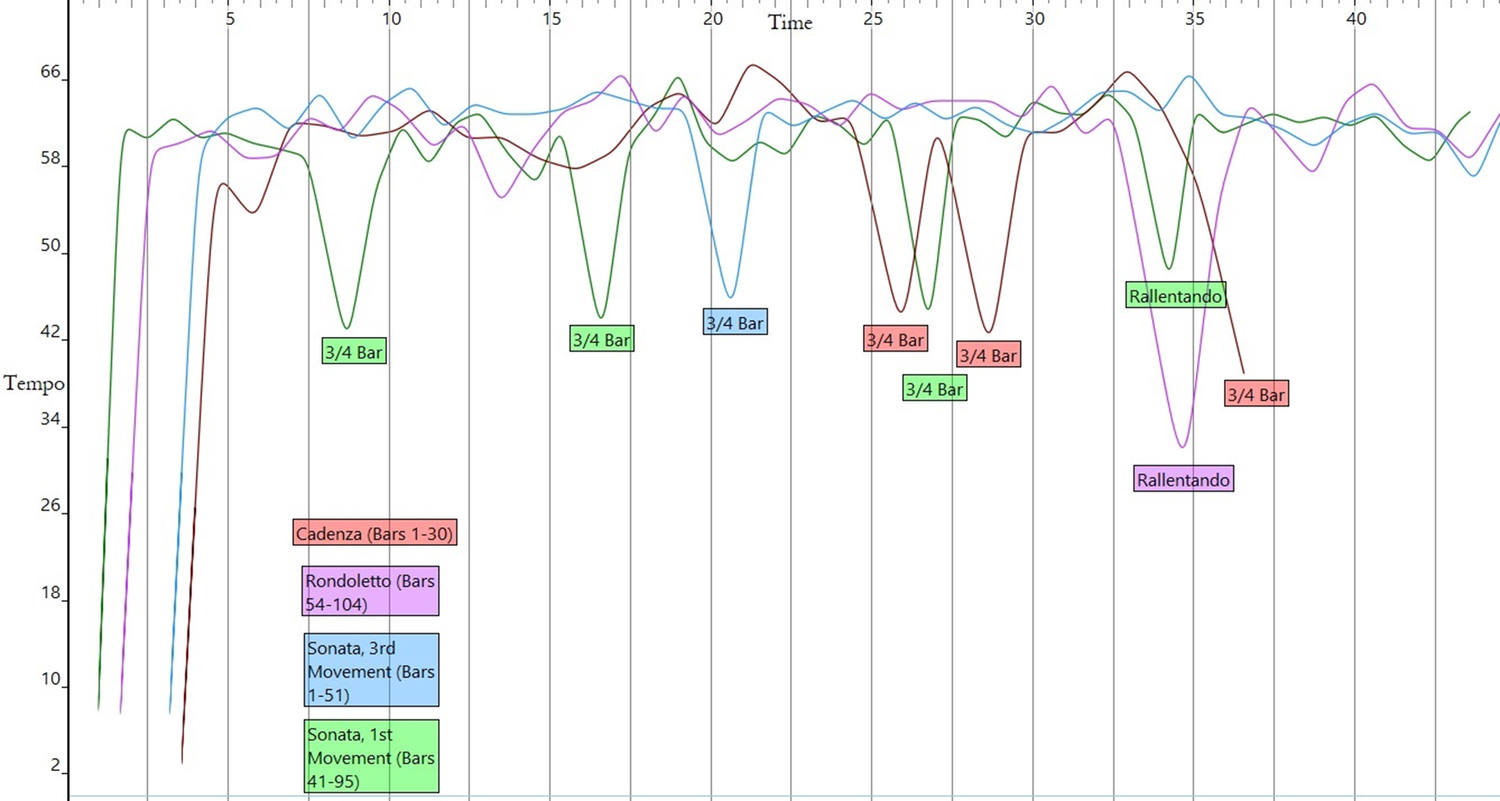

What does ‘rigour’ sound like? Unlike her live performance of Musica Stricta, here textual accuracy and attention to musical details emerge as much more important considerations for Yudina. Especially striking about her recording of the Piano Sonata is her care with Stravinsky’s spectrum of articulation markings, which vary widely, change frequently between phrases, and differ between right and left hands in many passages. But across both works, Yudina’s use of tempo is especially instructive, even though she admitted to playing faster than indicated.Footnote 136 Figure 2 contains passages from four movements — two from the Sonata, two from the Serenade — that are representative of Yudina’s approach to tempo more generally in these recordings. They are as follows: bars 41–95 of the first movement of the Sonata (in green); bars 1–51 of the third movement of the Sonata (in blue); bars 54–129 of the Serenade’s Rondoletto (in purple); and the first thirty bars of the Serenade’s Cadenza (in red). Each of these movements is predominantly in 2/4, and this is what makes them especially useful to compare. Having said that, Stravinsky changes time signature frequently, which is why I have chosen the passages in question: they are largely characterized by 2/4, with occasional, momentary diversions into other time signatures, which I have flagged in the graph.Footnote 137

Figure 2. Combined graph of Yudina’s tempos in selected passages of her Stravinsky recordings.

The fundamental point is quite a simple one: not only is Yudina’s approach to tempo remarkably strict and consistent, but there is effectively a common bar-length pulse of around 60 bpm. (The only moments of serious deviation from this in the graph are those in which the time signature changes, but Yudina’s actual tempo does not waver.) This is a signal marker of her self-proclaimed ‘rigorous way’ of playing Stravinsky, itself the result of several months of creative hard work and indeed hand-wringing over the correct way to perform this music. That backdrop is especially revealing given Yudina’s idiosyncrasy as an interpreter. Her Stravinskian efforts here are quite different from those involved in her loose tempos and jagged dynamics in Musica Stricta, something we can make sense of at least in part through the drastically opposing contexts in which the recordings were made. Her Musica Stricta captures a live performance, at a private affair, unintended for commercial or public release, and unedited after the fact — in other words, a ‘true’ live recording, if such a claim can be made. Her Stravinsky recordings were made in the studio, with its by then sophisticated editorial capacities, intended for stereo LP release in advance of the composer’s return to Russia and fashioned with the burdens of durability (and hence posterity) and fidelity in mind. It is worth remembering that both sets of recordings were made at most a matter of months apart in 1961: the intimacy of the Scriabin Museum afforded the flagrancy of Yudina’s Musica Stricta, while the controlled atmosphere of the recording studio made room for her disciplined Stravinskian tempos. We have moved, in other words, from provocation to rigour, the processes behind both of which involving considerable musical efforts, if in very different ways.

In June 1961 — not long before Yudina’s complaint to Melodiya about their recording conditions — Tikhon Khrennikov, the head of the Union of Composers, travelled to the United States to attend the first International Los Angeles Music Festival. Here, he proposed to Stravinsky that he celebrate his eightieth birthday in Russia.Footnote 138 After this, Souvtchinsky slowly began to realize just how precarious Yudina’s position in the Soviet Union really was. On 12 March 1962, he pressed her on this issue with respect to Stravinsky’s return:

From your last letter I see that you have fairly ‘complicated’ relations with the Composers’ Union. This fact worries me for two reasons: 1) Won’t you get in trouble when I. F. S. comes to visit; and 2) How will you ‘share’ him (that is, I. F.) between you, his friends, and the officials? For he is invited, unless I am mistaken, specifically by the ‘Soviet Composers Union’? Write me about this.Footnote 139

Around this point, Yudina’s place in the entire enterprise of Stravinsky’s repatriation begins to become much more peripheral. By February 1962, Stravinsky had had a change of heart, asserting to Souvtchinsky that he would refuse to go to the Soviet Union, referring to the Union of Composers as mrakobesï (obscurantists).Footnote 140 Souvtchinsky — whose exchanges with Stravinsky appear increasingly sycophantic — agrees with him, asking:

Is it really worth it for you, you in particular, to begin to argue and debate with all of these mrakobesï and all of these fools?—— Of course, I believe and know that an entire generation of musicians is expecting you there, but—— let them figure things out themselves and find their own way. When a real musician finally appears in the Soviet Union, he should come visit you, despite all obstacles.Footnote 141

Souvtchinsky does not specify what kind of musician he has in mind, but the implication is that Yudina — as a woman and a performer, rather than a male composer — is not worth the trouble of dealing with the Soviet officials. Stravinsky, however, reverses his decision, writing back that ‘it seems that I will nevertheless have to make an appearance there’ and that ‘if I don’t go, I will upset many (which I don’t want), for whom my appearance there is essential (and not just desirable — Yudina)’.Footnote 142

Stravinsky’s reasons for visiting the Soviet Union, then, were ultimately much more about pleasing officials than meeting Yudina and younger Soviet composers. And yet Souvtchinsky continues to play a double game, telling Yudina on 26 March 1962: ‘Apparently, thanks to you, he has taken to heart the importance of this visit; he speaks of you in the best terms.’Footnote 143 But this is the same Stravinsky who, only weeks later, wrote to Souvtchinsky,

I’m sending you this hysterical, 25-page letter by dear Yudina. Once again, I’m simply becoming afraid to travel there. I fear that I have neither enough strength nor nerves to bear this mixture of admiration, provincialism, and ‘cultural exchanges’ with Western Marxists.Footnote 144

In less than a year, the prospect of linking up with Yudina had become, for Stravinsky, more of a repellent than an incentive.

This exposes the exploitative logic, whether intentional or not, underpinning Souvtchinsky’s and Stravinsky’s relations with Yudina. She was always more important as a means of promoting Stravinsky. And when it became clear that she held far less official sway than they initially thought, she remained effective as a devoted performer of his music, even if such devotion came at her own professional cost, as we have already seen regarding the Gnessin Institute. It also came at great financial cost: as well as regularly performing his music, Yudina painstakingly curated and personally funded the ‘Stravinskyana’ exhibition, hosted at the Leningrad House of Composers during his visit.Footnote 145

By the time of Stravinsky’s return to the Soviet Union, between 21 September and 11 October 1962, Yudina had become an afterthought. As Levitz puts it, she ‘fell through the cracks’ of the composer’s visit, and as neither ‘Stravinsky’s close friend, nor a valued male competitor, nor an official representative of the state’, she was ‘excluded from Stravinsky’s social calendar’.Footnote 146 His visit to the ‘Stravinskyana’ exhibit on 4 October was her one chance to interact with him substantially, though the structured nature of the guided walk through the House of Composers no doubt inhibited any form of intimate or free-flowing conversation.Footnote 147 Otherwise, Yudina appears to have barely spent time with him.Footnote 148 She was devastated; she wrote to the Souvtchinskys directly after his visit to complain that Stravinsky

was surrounded by a multi-person entourage the barbed wire of which was impossible to penetrate; add to this countless paparazzi, reporters, and also simply onlookers insolently barging in (to rehearsals), pseudo-artists, insolent musicians with stupid things to say, ladies of various ages with bouquets; the main thing is that I was in Leningrad almost the whole time preparing the exhibit, and when he was there himself— I was feverishly learning the Septet.Footnote 149

Yudina had several activities planned for herself and Stravinsky, which included visits to Zagorsk, the Rublev and Scriabin museums in Moscow, and tea with her and Lina Prokofiev, but as she put it, ‘Everything I planned didn’t work out.’Footnote 150

The wound festered over time as Stravinsky grew more distant from Yudina and his trip faded into the past, resulting in an emotional outpouring following her unreturned telephone call to him when he left for Milan with Vera Stravinsky and Robert Craft. It is worth reproducing large extracts of her letter to the Souvtchinskys of 22 July 1963 that detail this change of heart:

About I. F.—— Perhaps the only correct way of living is: ‘not to get offended’—— But it is impossible not to be upset—— I phoned Milan twice, at the Hotel Continental. At first I was told: ‘We are expecting them, but they haven’t arrived yet’ (June 18); the second time: ‘They have arrived but are rehearsing’ (June 19); then I sent a telegram letter (because of the cheaper price), those take twenty-four hours, no longer, that was on the 20 or 21st [of June]. It was not returned to me—— that means they received it—— In it were congratulations, respects, and kisses to all three, a request for a ‘little message’ and my new address— all very detailed —— Until now he (I. F.) has always answered me.

[…]

—— So, he ‘exchanged’ me with those who are at the helm—— I did everything that was possible and impossible—— and am no longer needed and, ergo, can be disregarded. When something like this happens to another, one can talk a lot; when it happens to oneself, one can only step aside and be silent—— To be honest, there were analogous touches when he was here, too, but I looked at them ‘over the barriers,’ but now I have somehow—— lost all desire—— no one should have to aufbinden one’s friendship and one’s—— understanding——Footnote 151

On further reflection, Yudina told Souvtchinsky that her heart had ‘grown cold’ towards Stravinsky, concluding that ‘by small, successive touches, his perspicacity and his “experience” allowed him to understand what my official situation really was here… and yet he decided… to stay outside of it all… to keep his distance from me… given the situation, a genius of another calibre might have had precisely the opposite reaction!!’Footnote 152

Yudina’s fate was a particularly cruel one: her advocacy for Stravinsky, whose music she so faithfully and regularly performed, played no small part in her cultural ostracization and the repercussions she felt. And yet it was precisely because of her outsider status that the composer avoided spending any meaningful time with her. Once her initial utility for spreading his music was exhausted, and it became clear that she held no sway in the official musical circles of Khrennikov and Co., she was easily dispensed with — though her previous adoration for Stravinsky was not enough to blind her to the manner in which she was treated, as her later exchanges with Souvtchinsky make clear. The fallout Yudina experienced, while hardly the result of a maliciously designed plot by Stravinsky and Souvtchinsky to use and then exclude her, was certainly afforded by the combined musical and gendered hierarchy that animated their thinking: as a woman and a performer, she was always secondary, not only to the Union of Composers, but to the wider network of contemporary composition more generally — both of which, it hardly requires saying, were male-dominated. Yudina may not have understood this episode in those terms, but she felt its effects to the point of embitterment and disillusion — though by September 1963, in those last exchanges with Souvtchinsky about Stravinsky’s visit, Yudina was reeling from another setback.

IV

The story of what could be called Yudina’s avant-garde years came to an abrupt end in 1963. In late February, she flew to Khabarovsk in southeast Russia for a series of appearances, performing Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto on 24 February and giving a solo recital three days later, which consisted of works by Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Hindemith, and Stravinsky.Footnote 153 As part of this trip, Yudina was invited to the Khabarovsk School of Music, an occasion which proved catastrophic for her career: it resulted in her denunciation in an open letter intended for the Soviet newspaper Izvestia, signed by the faculty of the school on 7 March 1963 and spearheaded by Comrade Mirsky, the Director.Footnote 154 The accusations towards Yudina were several: first, that although she had been invited to give a recital at the faculty, she began by announcing categorically to a packed hall ‘that she would not play and would only speak’, a decision that allegedly shocked those in attendance; second, that Yudina spoke ‘with enthusiasm of foreign composers like Berg, Hindemith, Schoenberg, Stravinsky’ but did not have ‘a single kind word to say about Soviet music’, with the exception of Volkonsky; third, that Yudina presented her ‘extremely subjective’ views on contemporary music as ‘indisputable’; fourth, that she openly disparaged the music of Rachmaninoff; and fifth, that she requested permission ‘to read three poems that turned out to be by Pasternak’.

What all of this amounted to was a condemnation on the basis of typical socialist realist logic: the letter described the Khabarovsk School as supportive of ‘art for the people — in the name of the people’ and ‘united towards one main objective: to instil in the student a love of REALISTIC ART’. Yudina’s purported goal, by contrast, was to distance the youth ‘from the realistic positions of contemporary Soviet art’. But Mirsky delivered this accusation by throwing the gauntlet down to the authorities, in two ways. First, he suggested that the cultural ‘Thaw’ of the last few years had gone too far: ‘at the present time,’ the letter concludes, ‘when the ideological struggle is becoming increasingly acute, when the enemies of communism are not afraid to spend billions to surreptitiously deploy their strategy of propagating bourgeois ideology — Soviet music propaganda cannot be left to chance.’ But second, and more tellingly, he also pointed out that the more remote parts of Russia, such as the Far East, did not benefit from the same kind of musical enrichment as Moscow, Leningrad, or cities abroad. Mentioning the likes of Richter, Oistrakh, and Gilels, he asked, ‘Is it not strange that these musicians, who play all over the world and regularly fly over Khabarovsk, do not allow the Far-East to benefit from their art?’

What is really going on in this letter, then, has much more to do with larger domestic tensions around artistic provision in east and west Russia than with a single musical event. Since the mid-1950s, it was widely felt that leading Soviet artists found international touring to be ‘far preferable to tramping about the far reaches of the Soviet Union’, as Kiril Tomoff puts it.Footnote 155 Seen in this light, Mirsky’s letter was an opportunistic backlash, and the scapegoat was to be Yudina. Though the letter was not published in Izvestia, a copy was sent to Alexander Kholodilin, the head of the music division of the Committee for Artistic Affairs in the Ministry of Culture.Footnote 156 He wrote to Yudina requesting more information, and on 17 May 1963 she replied, rebutting several of the original letter’s claims, but was unsuccessful in clearing her name.Footnote 157 Kholodilin handed her an indefinite ban on all public concert performances, a devastating outcome that placed enormous musical and financial restrictions on her.Footnote 158 In the end, the ban lasted for three years, far longer than she could have initially envisaged.Footnote 159 She never recovered her sustained focus on contemporary music.

Of the many documents that Yudina deposited in the Russian National Library in St Petersburg, there is one letter that Volkonsky sent to her in January 1962 that is especially illuminating. In fact, it is not the letter itself but a note that Yudina attached to it, which she wrote in 1965 and explicitly intended for posterity. In it, she addressed both her dismissal from the Gnessin Institute in 1960 and the performance of Musica Stricta which led to her ban from the Leningrad Philharmonia, but given the year, we know that Yudina wrote it from the wilderness of her larger concertizing ban that came on the back of the Khabarovsk denunciation. Speaking of Volkonsky’s precarious position as a composer around the time of Musica Stricta, Yudina wrote that ‘today, thankfully, everything is back in order… Not for me, however… Since this date, and also since I read two poems in concert as an encore [on 19 November 1961] […] my concert activity has been stopped.’Footnote 160 ‘Everybody loses,’ she lamented, ‘both she who is rejected, and society.’ It is in its conclusion a blistering indictment of how she was treated, and particularly of her colleagues at Gnessin, though she could equally have spoken of the faculty at Khabarovsk or indeed of Stravinsky. But couched in the middle of her note is a simple plea:

that this fact [of her injustice], or rather the recollection of this fact, should also be transferred to the Manuscripts Department of the Russian National Library, because it is not so much a question of an event in my personal biography, as one ‘of cultural history’.Footnote 161

I wish to conclude in the spirit of Yudina’s plea, both in relation to the Soviet context and in more general terms. In the Soviet ‘Thaw’, performers who chose to experiment with new music, western or otherwise, voluntarily accepted unusually demanding responsibilities to bring such music to life while also putting themselves in a position of vulnerability. From Leningrad to Khabarovsk, Yudina’s journey in the ‘Thaw’ bears this out. Her championing of Musica Stricta and her commitment to Stravinsky’s music required extraordinary efforts stretching across several years. Here, the usually mundane administrative practicalities of acquiring scores and booking venues became struggles in their own right. And that she suffered materially is borne out by the bare facts of her dismissal from the Gnessin Institute in 1960, her exclusion from the Leningrad Philharmonia in 1961, and her more general concertizing ban from the Ministry of Culture in 1963. In the final decade of her life, after almost forty years as a professor in various institutions, she was left without a stable academic post, having been made redundant on dubious grounds for the third time in her career. She was subsequently deprived of her other main possible source of income on the official concert circuit.Footnote 162

Yudina’s experiences also highlight the sheer unpredictability of the repercussions that performers could face for pushing the boundaries of what was musically permissible. Her Leningrad Philharmonia ban for performing Musica Stricta and reciting poetry exemplifies this in the respect that she had already performed the work multiple times with no pushback. And the repatriation of Stravinsky speaks to a kind of inversion of these conditions, in the sense that her loud advocacy of the composer’s music became acceptable only because it changed in tandem with the official national position. But the Khabarovsk denunciation is the clearest example of this: here, Mirsky politically leveraged her appearance at the School of Music to fashion a sense of his institution’s nationalist commitment, all as a precursor to condemning the cultural authorities’ neglect of Russia’s Far East. Perhaps even more than this, the Khabarovsk denunciation is a strong testament to the primacy of discourse over practice in the distribution of punishment: Yudina received a devastating ban not on the basis of performing contemporary western music, but of talking about it.