Between 2012 and 2015, more than 20,000 rural people in Mexico organized and armed themselves against drug cartels. The groups they formed were mostly, but not exclusively, composed of men who called themselves autodefensas; that is, self-defense organizations, known in English as vigilantes. By 2014, an armed vigilante group existed in at least 9 of Mexico’s 32 states (see Pérez-Armendáriz and Duquette-Rury Reference Pérez-Armendáriz and Duquette-Rury2021). In many cases, these groups detained people suspected of working for a cartel and then turned them over to the local authorities. In some instances, however, vigilantes organized unofficial trials of their captives, while in others they carried out summary executions. Some vigilantes also engaged cartel members and even local police suspected of working for a capo in full-scale firefights. In some cases vigilantes disarmed and detained police. More than 100 people died in vigilante-related violence during this period.

The central question motivating this research is, Why did armed vigilante movements emerge in some states in Mexico but not others? To answer this question, this study focuses on those organized groups that declared they were providing security for their communities and whose collective actions were sustained beyond a single event between 2012 through 2015. In contrast to recent work that does not find a relationship between homicides and organized vigilantism, this research shows that there is such a relationship and accordingly offers evidence consistent with state capacity theory. In addition, it demonstrates that wealth inequality also helps to explain the emergence of vigilante organizations capable of sustaining collective action over time. The findings contribute to the scholarship on organized vigilante movements in highly unequal societies with low-capacity states.

To make the case, this article first outlines the general theories explaining organized vigilantism and offers contextual information about Mexico. Then it describes the sources and methods for two distinct quantitative analyses. The third section presents the findings, then fleshes them out with more contextual information. The fourth section offers a discussion and conclusion.

The Scholarship on Organized Vigilantism

Organized vigilante movements that sustain collective action over time are distinct from episodic “rough” justice events insofar as swift justice actors demobilize after meting out punishment, such as a flogging or a lynching.Footnote 1 Swift justice events tend to be rather spontaneous in Latin America (Huggins Reference Huggins1991), mobilizing after a community member shouts or rings a bell, rather than through organized deliberative bodies. In contrast, when people develop organizations for collective mobilization, they are better able to sustain group action over time and in ways that are comparable to social movements. But unlike social movements, vigilante groups do not mobilize to bring about or resist social change according to an ideology.Footnote 2 Instead, they claim to enforce law and order in their community, and thus in a spatially delimited way (Baker Reference Baker2004:173).

Although armed, organized vigilantes also differ both from militias, organized “on behalf of a political actor” (Schuberth Reference Schuberth2015:306), and from paramilitaries supported and trained by some faction of the state (Mazzei Reference Mazzei2009:4). Vigilantes, in contrast, self-organize to defend their communities, albeit in violent and illegal ways. Yet precisely because they see themselves as substitutes for the police—the most visible face of the state—their very existence where they emerge calls into question the state’s legitimacy and its specific claim to a monopoly on coercive force (Zizumbo-Colunga Reference Zizumbo-Colunga2017;990).Footnote 3 In short, the emergence of organized vigilante groups has political ramifications even when the actors involved do not share an ideology or have policy goals (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2003; Tankebe Reference Tankebe2009; Guerra Reference Guerra2018).

Of the four general theories explaining the rise of organized vigilante movements, the dominant view is that they emerge where states are (or are perceived as) too weak to provide basic security in a universal, competent, and accountable way.Footnote 4 Theories of “state capacity” argue that low-capacity states are unable to implement political decisions in all areas of their national territory (Mann Reference Mann1984) or are unable to provide basic public goods such as schooling and security within their jurisdiction and to all people, including those at the bottom of the stratification system (see Lee and Zhang Reference Lee and Zhang2017). For example, O’Donnell argues that most Latin American states have limited institutional capacity to implement policy or administer justice—including by policing—in all areas of their national jurisdictions (2004, 38). He refers to the areas where the rule of law is absent (where “the law’s writ does not run”) as “brown areas” (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell2004, 37). Short of state absence in “brown areas,” states may struggle to implement policy, administer justice, or offer basic security to all citizens for a number of reasons, including the lack of law enforcement resources, corruption, poor training of authorities—including the police—or all of the above. Regarding the efficacy of law enforcement, Durán-Martínez tells us that it varies according to what she calls the degree of state fragmentation or cohesion, as indicated by the “ability to coordinate enforcement actions” across levels of government (2015, 1382; also Dell Reference Dell2015, 1747). Durán-Martínez argues that highly fragmented states are a factor explaining cartel violence, including homicides.

Although there are multiple measures and descriptors of state capacity, the specific research on vigilante movements consistently shows that citizens self-organize into vigilante movements when extreme violence is perceived as having been caused by weak, distant, or absent states (Hernández Navarro Reference Navarro2020; Felbab-Brown Reference Felbab-Brown2016; Zizumbo-Colunga Reference Zizumbo-Colunga2015; Arellano Reference Arellano2012; Grayson Reference Grayson2011b; Burrell and Weston Reference Burrell, Weston, Pratten and Sen2007; Ungar Reference Ungar2007; Goldstein Reference Goldstein2003; Godoy Reference Godoy2006). To illustrate, Cruz and Kloppe-Santamaría (Reference Cruz and Kloppe-Santamaría2019) demonstrated that “people who support the use of extralegal violence are more likely to live in societies with elevated murder rates and fragile states” (2019, 60, my emphasis).Footnote 5 In such contexts, ordinary citizens substitute themselves for the police as a form of “self-help” aimed at addressing a real or perceived security gap (Ungar Reference Ungar2007).Footnote 6 Their doing so expresses distrust of the police or the central state, which, many believe, only protects the wealthy (Phillips Reference Phillips2017).Footnote 7 Thus, according to the dominant view emphasizing state capacity, any or all of the following factors operate when armed and organized vigilante movements sustain mobilization over time: ineffective police forces, high levels of homicides per capita, and high levels of distrust in the police (Smith Reference Smith2015).

A second general explanation of organized vigilante movements emphasizes income inequality (Phillips Reference Phillips2017; Ungar Reference Ungar2007). In this view, wealthy members of a community have the financial resources to pay for the labor, training, and weapons necessary for organized vigilante groups. While there are well-documented cases of wealthy citizens paying for private security, vigilantes, and in some instances, “social cleansing” groups, one recent study suggests that even moderate amounts of financial resources enable vigilantism where there is a demand for it (Ley et al. Reference Ley, Ibarra Olivo and Meseguer2019).Footnote 8

Irrespective of the minimum level of financial resources necessary to pay for weapons and labor, inequality itself creates social dynamics that facilitate patron-sponsored vigilantism because at least some chronically poor, unemployed, or otherwise low-income people will accept high-risk, violent, and illegal jobs (Phillips Reference Phillips2017, 1366). Phillips (Reference Phillips2017) further explains that the wealthy also magnify the perception of security threats with their gated communities, private security guards, and surveillance devices. In this context, poorer citizens may see themselves as relatively insecure and may support organized vigilantism in response. Income inequality, in short, contributes to a heightened sense of insecurity and creates the social conditions for patron-sponsored vigilantism. Either or both of these two mechanisms would lead us to expect organized vigilante movements where income inequality is greater.

A third approach stresses the role of either cultural or political socialization.Footnote 9 Some scholars suggest that Indigenous people have their own cultural notions about what constitutes a crime or an adequate punishment (Handy Reference Handy2004). Handy notes that Indigenous groups may seek swifter and, at times, rough justice when they become impatient with the slow workings of a state. Other scholars focus on the cultural legacies of violent but effective collective action, arguing that even temporally distant experiences with successful armed resistance to a repressive government can shape both intergenerational discourse about and an affinity for armed responses to subsequent threats (Osorio et al. Reference Osorio, Isabella Schubiger and Weintraub2019). In this view, a successful armed uprising in Michoacán, Mexico in the early twentieth century left a legacy about the efficacy of armed resistance against external threats. This legacy, Osorio et al. argue, explains why many in Michoacán turned to armed vigilantism against the cartels nearly one hundred years after the Cristero uprising (Osorio et al. Reference Osorio, Isabella Schubiger and Weintraub2019). Socialization into the efficacy of violent tactics is theorized to occur in other ways, as well (Della Porta and LaFree Reference Della Porta and LaFree2012). Bateson, for example, observes that people are more accepting of mano dura (strong-arm) punishments for criminals if they have lived through wartime experiences (2017, 643).

Network theory inspires a fourth approach to organized vigilante mobilizations. Network theory predicts that people are more likely to engage in high-risk collective action when others in their trust networks mobilize with them. Therefore, in contrast to theories stressing the culture of Indigenous groups, Mendoza argues that it is their co-ethnic solidarity—rather than their notions of justice—that makes coordination possible, especially when that coordination is aimed at providing a public good, such as local security (2006, 8–9).

About Mexico’s recent vigilante mobilizations, Pérez-Armendáriz and Duquette-Rury (Reference Pérez-Armendáriz and Duquette-Rury2021) find that vigilante groups are more likely to form in municipalities where social networks developed from the collaboration of local state authorities and civic hometown associations (in providing public goods). Osorio et al. (Reference Osorio, Isabella Schubiger and Weintraub2019) add that networks of trust can endure from prior experience with successful armed conflict—even if such conflict occurred in decades past—when the collective memory of prior armed mobilization is maintained. Others explain that support for organized vigilantism increases when trust in community is high but when, at the same time, trust in law enforcement effectiveness is low (Zizumbo-Colunga Reference Zizumbo-Colunga2015, Reference Zizumbo-Colunga2017).

Hypotheses

Any of these arguments could, in theory, apply to Mexico. First, when the country transitioned to electoral democracy in the 1990s, the ruling party, and eventually the central state, lost the ability either to discipline cartels or to provide protection from organized crime (Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2018; Knight Reference Knight and Wil2012, 129). Because of the country’s weak policing institutions (Uildriks Reference Uildriks2010; Grayson Reference Grayson2011a), the state failed to curb the power of and conflict between the cartels. On his election, President Felipe Calderón responded to the increasing lack of governability in some places by declaring a war against drug cartels in December 2006. His military strategy, however, only provoked a counteroffensive. To defend their multibillion-dollar businesses, cartels engaged in firefights with the military and executed uncooperative chiefs of police, political candidates, mayors, and even some military generals; they also terrorized civilians, even threatening an elementary school.

As the military weakened powerful cartels, their rivals fought for larger shares of the markets in drug and human trafficking (Durán-Martínez Reference Durán-Martínez2015), as well as to wrest control of valuable territory from their weakened competitors (Dell Reference Dell2015). Subsequent administrations have not significantly deviated from Calderón’s military strategy. Campaign promises notwithstanding, even President López Obrador’s newly created National Guard (circa 2019) “deepened the militarized nature of public security…. And made civilian policing at the federal level nearly obsolete” (Meyer Reference Meyer2020). The National Guard’s leadership is mostly former military; the rank and file are mostly transferred soldiers; and the military funds and equips the new security force (Meyer Reference Meyer2020; Felbab-Brown Reference Fini, Benítez and Gaussens2019).

As a result of the militarization of law enforcement, cartel-related homicides exploded, reaching the level of a noninternational armed conflict (Lessing Reference Lessing2015; Lambin Reference Lambin and Bellal2017). While the criminality associated with the cartels also manifests in higher rates of kidnapping for ransom, oil theft, weapons and human trafficking and more, homicides constitute the overwhelming majority (85 percent) of drug-related violence (Dell Reference Dell2015). Consequently, more than 200,000 people have been killed in Mexico since 2007 (Reuters 2018). While some criminal organizations—especially those without major rivals—will seek to reduce violence to avoid attracting the attention of uncooperative authorities, intercartel disputes over valuable areas became common as a result of President Calderón’s drug war (Dell Reference Dell2015). And despite some strategic and rhetorical shifts adopted by Calderón’s successors, violence and insecurity remain high 14 years since 2007. The insecurity has resulted in the internal displacement of roughly 345,000 people as of 2019, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center (IDMC 2019). It has also led to distrust in both the federal government and the police (see appendix).

While drug-related violence has affected large swaths of the country, qualitative research about Mexico’s vigilantes indicates that two states, Michoacán and Guerrero, were the epicenter of their movement between 2012 and 2015 because the central state’s absence in both places enabled extremely violent cartels. For example, Trejo and Ley argue that the central state’s abandonment of these two local states led to what they call “criminal governance” (2016, 42–44).Footnote 10 Similarly, Felbab-Brown argues that vigilantes in Michoacán and Guerrero are “an expression of both the absence of the state and its continual rejection by locals who find it remote, irrelevant, undependable, or outright corrupt” (2016, 174; see also Althaus and Dudley Reference Althaus and Dudley2014). Rosen and Zepeda go further, observing that Michoacán and Guerrero could be “classified as a failed state as many of the zones within the region are controlled by drug traffickers and the state is virtually absent, which has led some residents to take the law into their own hands” (2016, 84–85).

Qualitative studies clearly converge on the point that the central state was absent in these two local states. Indeed, traffickers in Michoacán even influenced local elections to engage criminality with impunity. While violence is practiced with impunity throughout the country (Dell Reference Dell2015), and while “criminal governance” is not always violent, these two local states are described as extremely violent by scholars emphasizing the central state’s absence there.

The qualitative research is, thus, consistent with the theory of low-capacity states, since there is no better indicator of low capacity than absence—a situation that creates the lawless “brown zone” conditions described by O’Donnell. But while the qualitative research suggests that Mexico’s absent central state both enabled extremely violent cartels and motivated vigilantism to fill the security gap, three recent quantitative studies do not find a statistically significant relationship between homicide rates (per 100,000) and organized vigilantes, at least not at the municipal level (Phillips Reference Phillips2017; Pérez-Armendáriz and Duquette-Rury Reference Pérez-Armendáriz and Duquette-Rury2021; Ley et al. Reference Ley, Ibarra Olivo and Meseguer2019).

I suggest that the homicide results in these three studies are questionable, since they relied on municipal-level murder rates. Their measures do not capture the fact that high murder rates create insecurity outside of the specific municipalities in which the crimes occurred (Villarreal and Yu Reference Villarreal and Yu2017, 794–98). For example, Villarreal and Yu found that increases in the state-level homicide rate in Mexico had “a significant effect on fear even after controlling for the municipal homicide rates,” probably because people read and watch media reports (2017, 794–95). And just as people feel anxiety about murders that occur in their states, they are also affected by surges in the homicide rate over time, and thus beyond what happens in a single year. Because Phillips’s study (2017) looks at homicide rates in 2012, as well as the change between 2011 and 2012, his findings about the murder rate are limited. My research, in contrast, assesses whether state-level homicides over several years of cartel violence in Mexico predict the rise of organized vigilante movements. Positive results would be evidence consistent with the theory of low state capacity, per the first hypothesis:

H1. Higher homicide rates per state will predict higher counts of vigilante action, all else equal.

As noted, both Mann and O’Donnell hold that a state’s ability to implement policy, administer justice, and police all areas of its territorial jurisdiction are among the many possible indicators of “state capacity.” Given that the theory argues that organized vigilante movements emerge to fill a real or perceived security gap created by the state’s inability to provide security, it follows that law enforcement resources allocated to local states are a comparable measure of state capacity at the subnational level. In Mexico, about 90 percent of local state and municipal budgets are financed through federal transfers (Dell Reference Dell2015, 1763), and thus, all police forces are paid (if poorly) to engage different functions of law enforcement from the federal budget. Yet the number of police varies by state, and this policing inequality could affect homicide rates, or the perception of security, in a local state. A second hypothesis follows:

H2. A higher number of state police forces per capita within states will correlate with lower counts of vigilante action, all else equal.

Police trustworthiness also gauges state capacity, albeit subjectively. As Jackson et al. (Reference Jackson, Huq, Bradford and Tyler2013) observe, when the police have legitimacy, the people accept their monopoly on rightful force in society. Police legitimacy, in turn, “crowds out” interpersonal violence. Cross-national research offers evidence consistent with this view (see Dawson Reference Dawson2018, 846; Zizumbo-Colunga Reference Zizumbo-Colunga2017). The scholarship on vigilantism similarly shows that distrust of police leads to support for extralegal actions to punish alleged criminals (Godoy Reference Godoy2004; Tankebe Reference Tankebe2009; Zizumbo-Colunga Reference Zizumbo-Colunga2017; Goldstein Reference Goldstein2003, 30; Handy Reference Handy2004). In Mexico, trust in the police has historically been low for many reasons, among them ineffectiveness, as well as high levels of corruption. It is possible, therefore, that the deep distrust of the Mexican police (see appendix) is what drives the self-organization of vigilantes independently of the homicide rate. A third hypothesis follows:

H3. Higher levels of distrust in the police per state will predict higher counts of vigilante action, all else equal.

The inequality thesis emphasized by Brian Phillips (Reference Phillips2017) also plausibly explains the rise of organized vigilante movements in Mexico. As noted, he argues that wealthier patrons supply vigilantes with weapons or pay for their labor as armed patrols. News stories, as well as interviews with hundreds of people from the state of Michoacán recorded by the Consejo Nacional de Derechos Humanos (CNDH), indeed report that business owners, including large landowners and owners of mining companies, financed the vigilante movement in that state. Did inequality also contribute to the rise of vigilante movements in other unequal states in Mexico, as Phillips suggests, or was the phenomenon unique to Michoacán? Phillips’s theory suggests a fourth hypothesis:

H4. States with higher levels of wealth inequality will have higher counts of vigilante action, all else equal.

The thesis about Indigenous cultures could apply in Mexico because many Indigenous groups in the country legally administer justice according to their traditions, which are recognized in law as usos y costumbres (i.e., customary law). In fact, some such Indigenous community police forces were the prototypes for many of the armed vigilante groups under study, according to the CNDH’s reports (CNDH 2013, 54, 2016, 140–41; Wolff Reference Wolff2020). For example, many of the roughly twenty thousand people who participated in Guerrero’s autodefensa movement (Fini Reference Fini, Benítez and Gaussens2019, 63–64) said that they were engaging in local policing practices consistent with Indigenous customary law (CNDH 2013, 12–2l; Fini Reference Fini, Benítez and Gaussens2019). Hernández Navarro (Reference Navarro2020) argues that Indigenous folk outside of Guerrero similarly responded to the dispossession of their lands (and other natural resources) by drug lords with community policing groups. Hernández Navarro (Reference Navarro2020) observes that when Indigenous groups responded to cartel threats, they often did so by creating community policing groups as an expression of the broader Indigenous rights movement inspired by the neo-Zapatistas in Chiapas during the 1990s. It thus could be that Indigenous conceptions of justice led to strong support of the organized vigilante movement in the country. Alternatively, it could be their trust networks, rather than their views of justice, that explain vigilante mobilizations. The following hypothesis follows from either proposition about Indigenous communities:

H5. States with higher percentages of self-organized Indigenous communities will have higher counts of vigilante action, all else equal.

Given the theory that armed conflict socializes people—directly or intergenerationally—to embrace armed struggle to neutralize threats, my analysis controls for armed insurgency in the last fifty years. Recall Osorio et al.’s thesis (2019) that Michoacán’s armed vigilantes were inspired by the Cristero rebellion of the early twentieth century. A question that arises from this thesis is, Why not other successful armed rebellions? After all, folks could find inspiration from the Revolution of 1910, the collective memory of which is central to Mexico’s national identity. But armed vigilante movements did not happen everywhere, not even in the state of Chihuahua—the revolution’s birthplace—which faced an extreme threat from the cartels, as evidenced in the highest number of homicides per capita there between 2009 and 2015. Nor did an armed vigilante movement occur in Chiapas, a state that had the most recent success with an armed uprising during the 1990s. That said, the other state with high numbers of vigilante actions, Guerrero, does have a recent history of armed insurgency, though the story there is not one of categorical success (Trevizo Reference Trevizo2014). The fact that organized vigilante actions occurred in other states beyond Guerrero and Michoacán suggests that something other than a recent history of armed insurgency matters. To assess what that is, this study controlled for two armed guerilla movements since the 1950s.

Data Sources, Research Methods, and Operationalization

A dataset was created using news sources, census figures, and survey data from the National Statistical Institute, INEGI. For the vigilante data, mostly Mexican news articles were identified via keyword searches for vigilantes and autodefensas conducted in Google and LexisNexis. While media coverage is not strong in the rural areas, the rise of an armed movement did focus media attention (including international media) such that I could glean data from the following five Mexican news sources: Proceso, Milenio, Reforma, El Universal, and Excelsior.

Less than 10 percent of the cases were coded from English-language news sources, such as the New York Times, the BBC, or the Guardian. The number of news sources coded for the vigilante data should mitigate against political bias by media outlets. Furthermore, while government advertising contracts with Mexican media influence press coverage of government officials (González Reference González2018), the reports in this study focused on public vigilante actions. The topic thus gave journalists more autonomy than they typically have when covering political elites. In fact, most of the Mexican media sources offered more details about public vigilante events than did the international sources.

That Mexican newspapers sustained coverage of vigilante movements is noteworthy considering the antipress violence that affects news reporting there. Research shows that criminal cartels and corrupt officials target journalists—typically local reporters—for reporting on their illicit activities (Correa-Cabrera and Nava Reference Correa-Cabrera, Nava, Tony, Staudt Kathleen and Kruszewski2013; Brambila Reference Brambila2017, 314; Bartman Reference Bartman2018, 1101; González Reference González2018, Reference González2021). For example, between 2010 and 2015, roughly 41 journalists were murdered in such retribution (Brambila Reference Brambila2017, 312). Given the vulnerability of journalists covering cartel violence or official corruption, reporters have become very cautious about their reports, and newsrooms have also changed their reporting practices (González Reference González2018). Some print media sources stopped using bylines in reports about criminal violence; many avoid identifying criminals by name or cartel affiliation or offering details about their operations (González Reference González2021; Correa-Cabrera and Nava Reference Correa-Cabrera, Nava, Tony, Staudt Kathleen and Kruszewski2013). Because most murdered journalists worked for local media outlets, many local reporters opt for self-censorship (Correa-Cabrera and Nava Reference Correa-Cabrera, Nava, Tony, Staudt Kathleen and Kruszewski2013, 105).Footnote 11

The news stories from which I created a database of vigilante events, however, were not directly focused on cartel activity or government corruption, and were therefore less likely to expose journalists to cartel or official retribution. These vigilante events were newsworthy because activists typically mobilized hundreds of armed individuals to caravan to towns in which they did not live. There they invited townsfolk to the public square and then erected armed roadblocks staffed with new recruits. In some instances they even exchanged gunfire with the police, the army, cartel agents, or other vigilantes. In other words, their collective actions were highly visible, carefully planned spectacles that drew both national and international media attention.

This does not, however, mean that journalists would face no political intimidation. A journalist was threatened (probably by local government officials) for publishing several stories on vigilante activity in Veracruz, a state with the highest number of murdered journalists in the period under study (Bartman Reference Bartman2018, 1098; Brambila Reference Brambila2017). But national news sources continued to report on vigilante collective actions even there.

I am confident that I captured most of the relevant information about vigilante collective actions, since the states I identify as having been the epicenter of vigilante activity are those identified as such in the extant scholarship (Phillips Reference Phillips2017; Felbab-Brown Reference Felbab-Brown2016; Osorio et al. Reference Osorio, Isabella Schubiger and Weintraub2019), as well as Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) reports (2013, 2016). Still, because media sources are imperfect, I do not interpret the magnitude of the coefficients. I only report their signs and statistical significance.

Focusing on collective actions initiated by vigilantes, my student and I coded news reports for the years 2012 through 2015 in two stages. In the first stage, my student coded where and when an event occurred, the vigilantes’ tactic, and their target, as well as the number of injured, killed, or arrested. In the second stage, I double-checked every entry to ensure that no event was counted twice. I coded 125 events of high-risk mobilizations by state, including armed blockades of roads or entrances to towns, rallies or demonstrations, shoot-outs with cartels or police forces, and cases where the vigilantes disarmed or detained others. I excluded cases in which groups were reported to have formed but did not act. The dependent variable therefore uses counts of the number of these types of collective actions per state between 2012 and 2015.

The dependent variable not only captures high-risk mobilization, but it does so across four years in time. As such, my data go beyond studies that measure attitudes toward vigilantism (Zizumbo-Colunga Reference Zizumbo-Colunga2017; García-Ponce et al. Reference García-Ponce, Young and Zeitzoff2021) or attitudes toward the use of violence (Cruz and Kloppe-Santamaría Reference Cruz and Kloppe-Santamaría2019). My dependent variable also offers more variation than either Phillips’s (2017) or Osorio et al.’s (Reference Osorio, Isabella Schubiger and Weintraub2019) dummy variable measuring whether at least one vigilante group existed in a Mexican municipality in just one year. Since Pérez-Armendáriz and Duquette-Rury (Reference Pérez-Armendáriz and Duquette-Rury2021) and Ley et al. (Reference Ley, Ibarra Olivo and Meseguer2019) utilized Phillips’s vigilante data, their dependent variable also lacks much variation.

I rely on three independent variables for each of the three hypotheses derived from the low-capacity state thesis. To assess H1, I use annual data on homicide rates per state (per 100,000) for the years 2012 through 2015 as reported by INEGI. My variable improves on previous measures that are either too local in scale or too static in time to capture the full effects of rising homicide rates in a state or region or over time.

A second measure of low state capacity (per H2) is from INEGI’s annual census of the number of state police per capita. As INEGI’s annual count of federal police forces has too many missing cases, I use only their counts of state police forces for the years 2012–2015, per state. This is a good measure because homicides fall under the auspices of the state police. To assess the third hypothesis derived from the low-capacity state thesis, I use the variable percent of people 18 years or older who perceive the state police as being “somewhat effective or very effective” when surveyed by INEGI in 2012–2015. Since trust attitudes toward the federal and state police forces are highly correlated in the period under study (r =.72 in 2012, r =.77 in 2013, r =.75 in 2014, r =.81 in 2015), the results from this independent variable will reflect overall trust in both the state and federal police.

Gini coefficients are standard measures of inequality, and while INEGI reports them annually at the national level, it reports them only every other year subnationally. Therefore, to assess the fourth hypothesis, I averaged the Gini coefficients of household disposable income per capita by state for the years 2012 and 2014 (the state-level Gini coefficients for 2013 and 2015 were not reported by INEGI). To examine the role of Indigenous communities per the final hypothesis (H5), I use the percentage of people (5 years of age and older) per state who speak an Indigenous language in school, as captured by INEGI’s 2010 census. Speaking an Indigenous language at school, as opposed to at home, at church, during festivals, or for commerce, suggests a significant degree of community autonomy.Footnote 12 It is precisely in such places that the community is likely to control its own judicial affairs and engage community policing. Such communities also have the kind of strong trust networks theorized to increase collective mobilization.

I created an ordinal variable to control for success with armed conflict since the 1950s. I code the state of Chiapas 2 because the EZLN’s relatively successful armed insurgency resulted in land reform and community autonomy (Harvey Reference Harvey, Foweraker and Trevizo2016; Eisenstadt Reference Eisenstadt2011). I code Guerrero 1 because the people there have a collective memory of armed insurgencies in their state since the 1950s, even though the guerrilla movements there have been brutally repressed (Trevizo Reference Trevizo2014). All other states are coded 0 because they did not experience significant or lasting armed insurgencies since the 1950s. I also control for each state’s percentage of small towns because the vigilante movements occurred primarily in rural areas, places defined as having 2,500 or fewer inhabitants. INEGI data for this variable are based on the decennial census.

Because the dependent variable is overdispersed count data, I use a negative binomial regression model for the analysis. The first model is a cross-sectional analysis that uses averaged data from 2012 to 2015. To control both for time trends and regional differences, the second model uses panel data with fixed effects. The regional data are from INEGI, which defines four regions (Center, Center West, North, and Southeast). In addition, secondary sources inform my analysis, and the supplementary opinion data in the appendix are from Latinobarómetro.

Findings

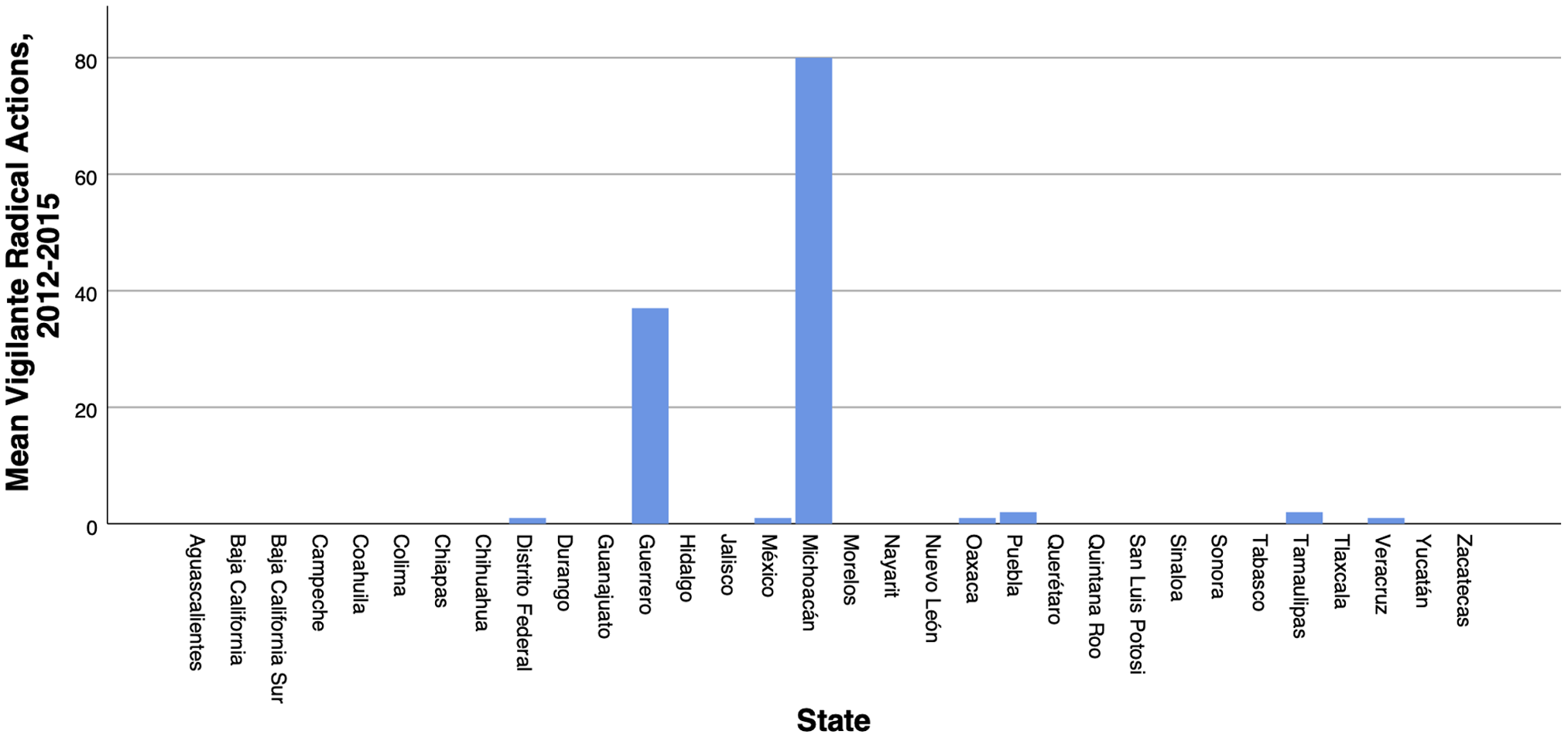

Table 1 offers descriptive statistics by year based on news reports, and table 2 offers information about variables in the regressions. As table 1 makes clear, an armed vigilante movement both spread quickly and became deadlier with time. The federal government stopped the movement in 2015 through a combination of force, negotiations, and cooptation. Also, the movement lost support from locals after some rival cartel agents (from the Jalisco New Generation cartel, or CJNG) infiltrated some autodefensa groups, especially in Michoacán, to weaken their rivals, the Knights of Templar (Templarios) (CNDH 2016; Wolff Reference Wolff2020). The story of the armed vigilante movement is therefore complicated, dynamic, and violent. As figure 1 shows, its mobilizations were geographically concentrated in the neighboring states of Michoacán and Guerrero, a finding consistent with Phillips (Reference Phillips2017), Felbab-Brown (Reference Felbab-Brown2016), Osorio et al. (Reference Osorio, Isabella Schubiger and Weintraub2019), and the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH 2013, 2016).

Table 1. Number of States per Year with Vigilante Movements

a Vigilante or vigilante target.

b Legal arrests or “detained” by vigilantes.

Note: Numbers are approximate.

Source: Author’s dataset.

Table 2. Means, Medians, and Standard Deviations for Key Variables per State, 2012–2015

N = 32

a Author’s data based on 125 cases of vigilante-initiated collective actions (multiple newspapers).

b Censo Nacional de Gobierno, Seguridad Pública y Sistema Penitenciario Estatales.

c 2010 INEGI census.

d Author codes gleaned from secondary sources cited in narrative. All other data from INEGI.

Notes: Data cover 31 states and Mexico City. Regions in Mexico: North (9 states); Center West (9 states); Center (8 states); South East (6 states).

Figure 1. States Where Radical Vigilante Actions Occurred, 2012–2015.

To assess the theories of organized vigilante movements, I model two distinct negative binomial regressions, shown in table 3. Model 1 provides a cross-sectional analysis using state averages of my key variables from 2012 to 2015. As is clear from model 1, the only variable that is statistically significant is trust in the state police. The negative coefficient indicates that greater trust in the police is associated with fewer collective vigilante actions, all else equal. Put differently, the greater the distrust in the state police, the greater the odds of an organized vigilante movement. As noted, this hypothesis is consistent with the low-capacity state thesis.

Table 3. Explaining Vigilante Collective Actions, 2012–2015

***p < .01 (one tailed test), **p < .05 (one tailed test), *p < .10 (one tailed test).

a 32 states × 4 years = 128.

Note: Results from two negative binomial regression models: cross-sectional and panel fixed effects.

The fixed effects regression shown in model 2 uses panel data with 128 state-year observations (32 states x 4 years = 128). This model includes region and year fixed effects to account for mean differences in vigilante action across time and region.Footnote 13

Consistent with the results from model 1, those in model 2 also show a statistically significant negative relationship between trust in police and organized vigilante actions. The panel data, however, show that the positive coefficient for homicides is statistically significant. This suggests that once we control for Mexico’s regional differences, annual homicides correlate with annual vigilante mobilizations in a statistically significant way. This finding is not only consistent with the theory of state capacity, but it departs from three recent studies (Phillips Reference Phillips2017, Pérez-Armendáriz and Duquette-Rury Reference Pérez-Armendáriz and Duquette-Rury2021, and Ley et al. Reference Ley, Ibarra Olivo and Meseguer2019) that do not find that homicide rates at the municipal level explain the emergence of vigilante organizations in a municipality. As noted, these studies neglected state-level homicides and looked at only one year of the movement. In contrast, if we look within regions over time, homicides predict which years in a region we can expect to see more or less organized vigilantism within regions.

While my regional control variables are greater in scale than a local state, my findings are still consistent with Villarreal and Yu (Reference Villarreal and Yu2017), who argue that homicides create insecurity both inside and outside the municipalities in which they occur. The sense of insecurity, in short, is not contained in the locations where they happen. As such, homicides predict more or less vigilante activity when we look at regions over time, a finding that is consistent with the theory of low state capacity. While the number of police per state was not statistically significant, as predicted by H2, the panel data still support the argument that low-capacity states that cannot control homicides and that inspire distrust in the police enable organized vigilante movements.

In addition to supporting the dominant theory of organized vigilante movements, the panel data model shows that the Gini coefficients are positive and statistically significant, as predicted by the inequality thesis (H4). I conclude, in accordance with Phillips (Reference Phillips2017), that the regions with higher income inequality had higher counts of armed vigilantism, all else equal.

In contrast, neither model offers evidence that Indigenous groups are more likely to engage in acts of organized vigilantism, as predicted by theory that focuses on either Indigenous culture or its social networks. In both regression models the coefficient associated with Indigenous autonomy is negative but statistically insignificant. This nonfinding is consistent with the fact that it was primarily mestizo (non-Indigenous) groups that mobilized as vigilantes in Michoacán. While qualitative research indicates that many Indigenous communities mobilized as autodefensas in Guerrero, Indigenous people did not mobilize in other states where they have community autonomy, such as Oaxaca and Chiapas. As such, the evidence here suggests that it is neither their cultures nor their high-trust networks that explain the vigilante movement in Mexico, as predicted by the fifth hypothesis.

Furthermore, neither the armed guerrilla conflict nor the small town control variable is statistically significant. Other factors simply do a better job of explaining why vigilantes mobilized during this period, net of percent small towns and net of prior experience with armed conflict. This latter point is noteworthy, considering Osorio et al.’s argument (2019) about the role of collective memory of armed insurgency in Michoacán nearly one hundred years earlier. While vigilantes also mobilized in Guerrero—a state with a more recent history of armed insurgency than Michoacán—they did not do so in Chiapas, where theory would have expected vigilantism, given their recent success as armed guerrillas during the 1990s.

In sum, results from the model using panel data indicate that armed vigilante movements occur in regions with local states that could not respond effectively to rising homicide rates and where there was considerable income inequality. Contextual information further describes low state capacity and income inequality.

The quantitative evidence indicating that high homicide rates predict organized vigilante reactions after controlling for regions, and especially where police are distrusted, is consistent with what vigilantes themselves have said about their uprisings to many journalists. Here is how one leader described his community’s actions in Guerrero: “an increase in violence in the region and the absence of government intervention have left the community with no choice but to arm even its children” (Linthicum Reference Linthicum2020). To give another example, José Manuel Mireles, a vigilante leader in Michoacán, was quoted as follows: “None of the authorities had been able to fulfill their duties because all of them [municipal, state, and federal] were part of the cartels or were on their payroll. We did not know that at the moment, but we assumed it” (La Jornada 2013, cited by Zizumbo-Colunga Reference Zizumbo-Colunga2017, 995; Hernández Navarro Reference Navarro2020).

The scholarship similarly observes that the federal government essentially abandoned Michoacán and Guerrero. While explaining the exact causes of the state’s purported absence in the region is beyond the scope of my argument, two studies in addition to the CNDH’s reports observe that the federal government did not coordinate security with the local governments of Michoacán and Guerrero, despite the appeals for help by some mayors in the region. According to Trejo and Ley (Reference Trejo and Ley2016, 40–43) and Felbab-Brown (Reference Felbab-Brown2016, 175–77), the federal government’s absence in the region made it possible for an especially ruthless cartel, the Templarios, to become the de facto authority in large parts of Michoacán—for example, in the city of Apatzingán, the Apatzingán Valley, and the low-elevation Tierra Caliente region (which is ripe for poppy production). Trejo and Ley (Reference Trejo and Ley2016) further explain that after the 2011 elections, when the Templarios’ candidates won Michoacán’s governorship and many local elections, a capo (called “La Tuta”) demanded that three-fourths of all mayors in that state turn over 30 percent of their municipal government budgets to the cartel (Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2016; Althaus and Dudley Reference Althaus and Dudley2014). The Templarios’ orders (dictados) were enforceable at that time because they had members in various mayorships, in city councils, and in local police forces (Felbab-Brown Reference Felbab-Brown2016, 176). According to Trejo and Ley,

the Knights of Templar took advantage of the increasing vulnerability of mayors in the Apatzingán Valley and the Tierra Caliente region and sought to capture local governments through lethal coercion and establish new forms of criminal governance in the cities, seizing control of municipalities and their local budgets and taking control of local businesses (e.g., lime and avocado producers) and intimidating citizens via extortion and kidnapping. (2016, 42)

While the Templarios established criminal hegemony in Michoacán during the period under study (until another cartel, the CJNG, challenged their monopoly), intercartel warfare was intense in Guerrero just before the rise of the vigilantes (Hernández Navarro Reference Navarro2020; Zepeda Gil Reference Zepeda Gil2018; Felbab-Brown Reference Felbab-Brown2016).Footnote 14 Intercartel battles were especially pitched over the port city of Acapulco and over Guerrero’s second-largest city, Chilpancingo (see Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2015; Felbab-Brown Reference Felbab-Brown2016. Also see Blume Reference Blume2017). The city of Iguala was relatively stable (until the police forces there disappeared 43 students), but only because Iguala’s mayor and police worked for a cartel.

Trejo and Ley (Reference Trejo and Ley2015) argue that the federal government was absent in Guerrero, and Felbab-Brown (Reference Felbab-Brown2016) similarly observes that large expanses of the Tierra Caliente region within Guerrero had minimal state presence. A journalist recently put it this way: “the sprawling municipality of Chilapa de Álvarez is one of the most lawless areas of Mexico. Government authority has all but disappeared, leaving criminal cartels and self-proclaimed ‘community police’ groups to compete for control” (McDonnell Reference McDonnell2020). Consequently, lethal violence in Guerrero would remain much higher than the national average between 2007 and 2015. The cartels in this state even made it difficult for the federal government to fully distribute disaster relief aid to the communities and cities that were devasted by a cyclone in September 2013 (Zizumbo-Colunga Reference Zizumbo-Colunga2017, 1000).Footnote 15

In sum, while cartel violence was not unique to Michoacán and Guerrero, an especially ruthless cartel was able to establish criminal governance in large parts of the Tierra Caliente region straddling three local states, where scholarly, journalistic, and folk accounts say that the central state was absent. There is no stronger indicator of low state capacity than state absence. The criminal enclaves that took hold in the region with low-capacity local states and an absent central state proved especially violent. This, in turn, provoked people into defending themselves through organized vigilante movements.

Inequality also mattered. Numerous journalists and at least two scholars report that avocado, lime, and mango exporters and ranchers, as well as many shopkeepers, financed the vigilantes in Michoacán, where at least twice as many vigilante mobilizations occurred as compared to Guerrero (see figure 1) (see Guerra Reference Guerra2018; Wolff Reference Wolff2020). Large and small business proprietors—including mining, ranching, logging, and transshipment companies—financed the vigilantes because the Templarios levied taxes on their businesses and did so using the threat of arson (Felbab-Brown Reference Felbab-Brown2016; Althaus and Dudley Reference Althaus and Dudley2014, 8).Footnote 16 Farmworkers also paid a price when their rancher (ganadero) bosses were extorted (Guerra Reference Guerra2018, 109). The poor in this agricultural region reported that the Templarios “taxed” their wages and subjected them to extortion, to kidnapping for ransom, and to rape. Like other newly ascendant cartels, the Templarios violated tacit norms guiding cartel-civilian relations (Guerra Reference Guerra2018). Their doing so motivated citizens from all socioeconomic backgrounds to free themselves from their terror. In addition to the patronage provided by the wealthier businesspeople, inequality mattered because there were many poor people ready to accept payment for their efforts to “cleanse” the community of the Templarios.

Both the quantitative and qualitative evidence helps us to understand why there were no sustained vigilante mobilizations in Chihuahua, which had one of the worst homicide rates in the country. There were two mitigating factors in that state. First, inequality decreased between 2008 and 2014 (OECD 2014) as this northern state saw “an important decrease of 4.5 percentage points in multidimensional poverty” (OECD 2014, 9). Second, Calderón’s government supported Ciudad Juárez’s mayor and the state’s governor, and their intergovernmental cooperation weakened the cartels, if only temporarily. According to Trejo and Ley (Reference Trejo and Ley2016), President Calderón’s support strengthened both the local police and the local governments of that state. Specifically, Ciudad Juárez’s local police forces were purged of their criminal elements, if only for a period (Ainslie Reference Ainslie2013). Trejo and Ley argue that intergovernmental cooperation with Chihuahua’s local governments “weakened both the Juárez and Sinaloa cartels and empowered local governments to resist the violent attempts to capture local governments and civil society” (2016, 46).

In sum, the degree of intergovernmental support from the federal government may well have strengthened or weakened the local states, forcing some to manage cartels without much support from the federal government. Vigilantes themselves say as much. Whatever the exact causes behind the central government’s absence in the region, it is clear from the quantitative evidence that organized vigilante movements emerged where there was greater distrust in the effectiveness of the state police, where homicide rates were high, and where income inequality was greater.

Discussion and Conclusions

In contrast to three studies that do not find that homicides at the municipal level matter for the vigilante movement, results from my regression using the panel data with regional and year fixed effects show that high levels of murder per state correlate with their armed collective actions when the model controls for region and year. This positive relationship is an expression of low state capacity because higher homicide rates indicate violent criminal enclaves, the kind that take root where local governments and police are either too weak or too corrupt to dismantle them. It is not, therefore, surprising that my second measure of low state capacity, police distrust, also correlates with the rise of organized vigilante movements in both models. Qualitative accounts suggest why: the scholarship is consistent with journalistic reports that cartels do employ some police forces, which probably explains some of the distrust in Mexico’s state police.

My third indicator of low state capacity, the number of state police, is not statistically significant. Future research could refine these results by assessing whether law enforcement type, or tactics, matter for predicting the odds of organized vigilante movements. What is clear from the panel results and qualitative reports is that organized vigilantism in Mexico was a defensive response in which ordinary people attempted to substitute themselves for the police forces that they distrusted. In other words, people sought to fill a security gap created by the state’s inability to provide this basic public good.

As evidenced in Michoacán and Guerrero, low-capacity states make it difficult to govern. Worse, when the local police forces, local mayors, or governors are on the payroll of the cartels, policing and thus the “state,” are practically nonexistent. As Guillermo O’Donnell argues, such spatial or territorial gaps in the state’s presence (or “brown areas”) affect both the quality of citizenship and democracy. As demonstrated here, the security gaps in the brown areas cost people their lives.

Although President Enrique Peña Nieto’s government attempted to regain control of the region by offering to deputize vigilantes, most groups in Guerrero refused on the grounds that the Mexican state was untrustworthy (Althaus and Dudley Reference Althaus and Dudley2014, 16). For a very short period, the federal government had more success in Michoacán, but vigilantes there refused to disarm on the grounds that putting down their arms would make them vulnerable to cartel retaliation. As Felbab-Brown observes, that the federal government could neither prevent nor dismantle the vigilantes is “glaring evidence of the weakness of the state in the rural areas of Mexico” (2016, 179; also Hernández Navarro Reference Navarro2020). Building state capacity by creating functioning police forces and generally improving the justice system are clearly necessary for democracy to work for all citizens, including those who cannot afford private security.

As evidenced both by the quantitative panel results and journalistic reports, income inequality facilitated the vigilantes’ mobilizations. Journalists report that wealthier patrons in Michoacán financed the vigilantes’ weapons. Agricultural exporters, as well as large and small shopkeepers in that state, also paid for some of their time on patrol. But rural folk there and in Guerrero also had a stake in retaking control of their communities, and they contributed to the movement by providing their labor, food, organizational and moral support. (When vigilantes themselves began to commit crimes, this support was withdrawn, a topic beyond the scope of this analysis.) Therefore, policy that reduces extreme poverty would also reinforce the rule of law by making it less likely that people would be available and willing to join vigilante movements.

Inferences drawn from my case study suggest that sustained vigilante movements can occur in societies with low-capacity states that foment distrust in the police and that have highly unequal income distribution. Like Mexico, there are other Latin American states that cannot administer justice everywhere. Such low-capacity states create the potential for armed vigilante movements because the “brown areas” within their national territories create the kind of insecurity that motivates people to substitute themselves for the police. They may even do so illegally when states fail to provide this public good. Research on some societies in Africa points to similar dynamics (Tankebe Reference Tankebe2009; Smith Reference Smith2015). Since many Latin American societies are also highly unequal, the social conditions are ripe for patrons to finance vigilante movements where rampant insecurity creates a demand for them.

Appendix

Figure 2. Relationship Between Homicides, Perceptions of Insecurity, and State Legitimacy: Percent of People Over Time Reporting “No Confidence at All” in Government or Police

Sources: Author’s elaboration with data from Latinobarómetro and INEGI. Note that the missing opinion datapoints about confidence in the government and the police are due to the fact that Latinobarómetro did not conduct a survey in just two years, 2012 and 2014. INEGI’s homicide data begin in 2009 and insecurity data in 2011 (National Survey of Victimization and Perception of Public Security [ENVIPE]).