The histories of the social sciences in the United States and Latin America have often intersected, leading to a knowledge-making process beyond national borders. This is apparent during the period running from Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor policy through the onset of the Cold War, when the United States cemented its global hegemony in the social sciences and the Americas witnessed more intense scientific exchange. When considering this international expansion, scholars have generally drawn attention to how US writings on Latin America have expressed teleological and ethnocentric viewpoints on the social change transpiring in this era, one example of which is the theory of modernization, which posed US society as a model of modernity toward which the world peripheries would inevitably march (Gilman Reference Gilman2003; Engerman Reference Engerman2003; Latham Reference Latham2011). But little is known about how these specialists were influenced by intellectuals residing on the margin of global circuits of knowledge production. Similarly, US academics did not attribute only one meaning to the modernizing changes underway in the Global South (Brasil Jr. Reference Brasil2013).

Countering the notion that modern science is exclusively a product of the North Atlantic, transnational studies have begun signaling how the transborder circulation of actors and ideas and the formation of intercountry and interregional networks have been constituents of past knowledge production (Chakrabarty Reference Chakrabarty2000; Sivasundaram Reference Sivasundaram2010; Raj Reference Raj2013). In the social sciences, traditional historiography’s “nationalist” methodological assumptions have been reevaluated, and the transnational flows that contributed to the development of disciplines like sociology are now beginning to be considered (Heilbron, Guilhot, and Jeanpierre Reference Heilbron, Guilhot and Jeanpierre2008). This endeavor may contribute to deprovincializing the social thought produced in countries of the Global South, such as Brazil (Costa Reference Costa2006; Brasil Jr. Reference Brasil2013; Maia Reference Maia2014; Lopes Reference Lopes2020), while also intersecting with researchers’ desire to push analyses of exchange beyond the notion of a one-way street in the Americas, where movement is only from North to South (Joseph, LeGrand, and Salvatore Reference Joseph, LeGrand and Salvatore1998; Shukla and Tinsman Reference Shukla and Tinsman2007; Rosemblatt Reference Rosemblatt2018; Lomeli and Rapport Reference Lomeli and Rappaport2018).

To explore these questions, this article looks at US sociologist Donald Pierson’s work in Brazil, particularly at his dialogue with the local intellectuals who informed his analyses of modernization and at the extent to which he saw social change as implying an “Americanization” of Brazilian society.

Pierson received his PhD from the University of Chicago with Robert Park as his advisor. In 1939, shortly after completing field research in Salvador, he became a professor at the São Paulo Free School of Sociology and Politics (Escola Livre de Sociologia e Política de São Paulo, or ELSP).Footnote 1 Settling in Brazil at a critical juncture in US cultural diplomacy, when the specter of war was fueling grave concern in Washington about Nazi-fascist influence in Latin America, the sociologist came to play a key role in inter-American academic exchange and the institutionalization of the social sciences in Brazil (Limongi Reference Limongi and Miceli1989; Peixoto Reference Peixoto and Miceli1989; Oliveira Reference Oliveira1995; Pierson Reference Pierson and Corrêa1987). Emerging out of close dialogue with local knowledge traditions, Pierson’s writing offers a prime resource for reexamining the nature of social scientific exchange between the two countries.

Although the topic of social change is a constant in Pierson’s work in Brazil, the literature has never duly explored his perspective on modernization. Instead, scholars have generally scrutinized his positions in the debate over race prejudice in Brazil without paying attention to the broader sociological approach through which he examined local race relations. Furthermore, in trying to pinpoint the sources of his interpretations, authors have at times focused too much on one specific national intellectual context at the expense of the other, emphasizing either Brazil or the United States (Vila Nova Reference Vila Nova1998; Brochier Reference Brochier2011). We argue, however, that Pierson’s studies on race relations are inseparable from the broader discussion about the construction of a modern social order in Brazil. More important, we believe his work can only be fully grasped if we take into account how it was influenced by the transnational intersection of ideas and authors.

The intellectual dialogue between the United States and Brazil makes itself felt at two key moments in Pierson’s work, each affecting his view of social change differently. In the 1930s, he analyzed the emergence of modernity in the country in his research on race relations in Bahia. Drawing from a perspective shared with authors like Robert Park and Gilberto Freyre, Pierson portrayed rural, patriarchal Brazil as an important piece in the construction of a more democratic and racially inclusive social order that actually held more potential than the United States to fulfill the liberal and modern ideals of a “multiracial class society,” in which individual effort and professional skills determined people’s social status more than did race.

In the 1950s, as a collaborator with the Smithsonian Institution’s Institute of Social Anthropology (ISA), Pierson began studying the social transformations suffered by traditional communities in the Brazilian interior. His research agenda centered on the study of traditional patterns of rural culture and social organization and on how metropolitan centers might be exerting a modernizing influence on these communities. In convergence with the sociology produced by such Brazilian authors as Florestan Fernandes and Luiz de Aguiar Costa Pinto, he came to regard the persistence of elements of the country’s past as an obstacle to modernity. This new perspective was evident during his participation in the debate on the relation between racism and modernity during the UNESCO Race Relations Project and the 1954 Conference on Race Relations in World Perspective. No longer ascribing the same potential to Brazil’s patriarchal, familialist order, he concluded instead that tradition might actually hamper the transformation of its society.

This new analysis bore similarities to that of the era’s Brazilian sociology, which had an implicit commitment to the construction of a more egalitarian society, the achievement of democracy, and the erasure of the country’s authoritarian, unequal past. By adopting this perspective, which likewise led him to a new stance in the Brazilian race debate, Pierson was reevaluating how the past might impact construction of the new society then emerging in response to urbanization and industrialization. In other words, rather than regarding social change as a continuation of the country’s history, he was now framing it as a break with the past.

From the prism of tradition: Race relations in the city of Salvador

Pierson’s best-known work is his study of Black-white relations in Bahia, written as his dissertation at the University of Chicago. Published in book form in the United States in 1942 (Pierson [1942] Reference Pierson1967) and in Brazil in 1945 (Pierson Reference Pierson1945a), the text garnered both praise and criticism, with the general consensus being that Pierson had painted an idyllic picture of race relations in Brazil. He became known as the author of the controversial thesis that discriminatory attitudes against “populations of color,” to use his own expression, had much more to do with class bias than race bias. According to his critics, when Pierson read expressions of racism in Salvador from a class perspective, he was being held hostage to the notion—associated with the work of Gilberto Freyre and with the ideology of the country’s ruling white strata—that the “Brazilian solution” to race conflict had been achieved through miscegenation and racial democracy (Hasenbalg Reference Hasenbalg1995; Guimarães Reference Guimarães, Chor Maio and Ventura dos Santos1996; Skidmore [1974] Reference Skidmore1993).

More recently, studies have pointed to links between Pierson’s research and the conceptual framework and investigative agendas of the Chicago school of sociology (Brochier Reference Brochier2011; Cavalcanti Reference Cavalcanti1996). His work was indeed part of an effort by Park and collaborators to broaden explorations of so-called race and culture contacts beyond the United States to encompass comparative analyses with other interethnic arrangements that arose following European colonization around the world (Pierson Reference Pierson1936, Reference Pierson1944; Valladares Reference Valladares2010; Silva Reference Silva2012).

Nevertheless, as we will argue, far from the product of a simple overlaying of US and Brazilian influences, Pierson’s interpretation of race relations in Brazil drew from points common to the ideas of Park and Brazilian authors like Freyre and Oliveira Vianna, with whom he had direct contact. Furthermore, rather than limiting his research to the phenomenon of racial prejudice, Pierson sought to understand the historical process of Black integration and what it might mean for Brazil’s entrance into modernity. Pierson’s depiction of Brazil was somewhat contradictory. Precisely because the country’s social life was organized around traditional, rural, and personal principles (defined by authors like Freyre as the Brazilian patriarchal, familial regime) and because of its miscegenationist ethos (an outgrowth of the specificities of Portuguese colonization), Pierson believed that Brazil actually stood a better chance than the United States of undermining color-based caste barriers and achieving aspirations identified with modernity. This would be an order grounded in “free competition” and equality of opportunities, in which a person’s status would be determined more by individual effort and ability than by race (Pierson [1942] Reference Pierson1967).

Within this process, Pierson did not believe the effects of urbanization and industrialization, visible especially in São Paulo, would disturb the slow, progressive, longer-term evolution of the national community into an increasingly integrated ethnic-biological and, especially, moral and political whole.Footnote 2 In Pierson’s eyes, this was in stark contrast with the situation in the United States. In the urban, industrial centers of the US North, individualism, economic struggles, and anonymity were feeding racial divisions and conflicts. In the South, Yankee-imposed abolition had abruptly altered local customs and ignited the Civil War, prompting extreme, segregationist reactions by whites, who felt doors were opening for Black social mobility. This had interrupted the construction of a shared moral order, woven organically at the community level and based on prolonged close contact between racial groups on the plantation, a process that—according to Pierson—had been taking place in the antebellum South despite these groups’ unequal positions in the social hierarchy ([1942] 1967, 345–346).

In examining Pierson’s positive assessment of the race situation in Brazil, we must bear in mind that these were the days of the Good Neighbor Policy. Latin America was sparking keen interest in the United States, particularly among its more liberal intellectuals, who were apprehensive about the possible harmful consequences of modern capitalism in their own country, such as excessive individualism and materialism. They turned an eye to their neighbors south of the Rio Grande, imagined as part of another America not yet wholly tinged by the woes of urban-industrial civilization. Traditionally seen as a place of primitivism and racial degeneration, Latin America was now cast in a positive light by reformist circles in the United States, that is, as the source of original societal experiences that could contribute to building a modern culture on renewed foundations across the continent (Schwarcz Reference Schwarcz1993; Pike Reference Pike1985).

This understanding of Latin America formed the backdrop of Pierson’s study in Salvador, which emphasized traditional aspects of local society over those resembling an urban-industrial order.Footnote 3 Pierson wrote that Salvador was a “relatively isolated city” and consequently a “culturally passive area.” It was attached to long-standing customs, and change transpired there slowly. Its “preindustrial” order was marked by “intimate ties” and the “close association of members of these large family groups,” which helped maintain the community’s “social cohesion” ([1942] 1967, 13–14). With the aid of tradition, racial antagonism was steadily mitigated and there were no acute manifestations of conflict.

In his research on Bahia, Pierson’s theoretical and conceptual framework originated in studies by Park, who deemed conflict intrinsic to interracial contact anywhere in the world. According to this perspective, the concentration of different ethnic groups within one territory inevitably triggered space- and resource-related disputes, which could be either unconscious (in the form of “competition”) or overt and racialized (“conflict”). However, because disputes like these could not persist indefinitely without jeopardizing the very fabric of society, more or less stable arrangements would be generated as each ethnic group found its specific niches and roles (“accommodation”) or as antagonistic groups merged to form a new ethnic and cultural unit (“assimilation”) (Park and Burgess Reference Park and Burgess1921, chaps. 8–11; Pierson Reference Pierson1945b; Chapoulie Reference Chapoulie2001).

Pierson concluded that Salvador was in an advanced process of racial amalgamation and Black integration, and this was helping to erode the color barriers typical of the caste system born of slavery. Even if Blacks’ skin color, nose shape, or especially hair texture still carried stigma from the days of slavery and subordination, Pierson thought this would fade away as miscegenation progressed and a growing number of Blacks and persons of mixed color rose into middle and upper strata, proving their worth and earning acceptance by whites. According to Pierson, color had little to do with determining an individual’s social position, as compared to such variables as wealth, education, intelligence, and professional skills. His more general hypothesis was that Bahia, like Hawaii, was a “multiracial class society,” diverging from the United States, where some Blacks had bettered their lot economically yet were still not accepted into the white world and thus formed a separate middle class comprising people of color. Likewise, this distinguished Brazil from the extreme case of India’s caste system, where individuals were assigned a rigid status from birth and intermarriage was highly restricted.

There is no doubt that the debate waged by scholars of the Deep South, concerning application of the conceptual pair “caste/class” to investigations of race relations, wielded considerable influence over Pierson (Pierson Reference Pierson1945b, 442–458; Warner Reference Warner193637). But the works of local interpreters of Brazil’s social formation such as Freyre and Oliveira Vianna were equally decisive in shaping the sociologist’s viewpoint. This was the case of Pierson’s argument that ongoing racial miscegenation, which dated to early colonization, would slowly “whiten” the population and thus contribute to the racial integration of society as a whole. While the census information on Salvador’s racial profile was incomplete and data were not conclusive, as Pierson himself recognized, he backed up the whitening thesis by citing authors such as Oliveira Vianna, who famously claimed Brazilians were undergoing “steady Aryanization.”Footnote 4 Francisco José de Oliveira Vianna, who had a background in law and was well known for his criticism of the liberal political order of Brazil’s First Republic, devoted himself to studying Brazil’s socially and racially heterogeneous reality in hopes of identifying the foundations for nation building.Footnote 5 While Pierson did not share Oliveira Vianna’s racist bias about the moral and intellectual superiority of whites, he appeared to align with him when he said that, generation by generation, Blacks were steadily growing less Black and more mixed, while those of mixed race were growing whiter, leaving the Brazilian population looking “more European, less negroid” (Pierson [1942] Reference Pierson1967, 123).

Even more important to Pierson’s reading of Brazilian society was the idea, advanced by Francisco Oliveira Vianna in Populações meridionais do Brasil (1920) and by Freyre in Casa grande e senzala ([1933] 2003, translated as The Masters and the Slaves, [1946] Reference Freyre and Putnam1966), that Brazil’s prevailing social relations were of a personalized nature. In his interpretation of the local race situation, the extended, patriarchal family was central to Brazil’s social formation. This helped explain why the process of group merger spurred by interethnic contact in Brazil had not been disrupted when abolition was decreed and Blacks gained formal citizenship—in contrast with the United States. In Pierson’s words: “Family ties … are tenacious. Loyalty to the clan still today transcends loyalty to the state, the church, or any other institution. There is strong personal attachment between white parents and colored offspring, both legitimate and illegitimate, and these ties obviously place the mulatto in an advantageous position for social advancement” (Pierson [1942] Reference Pierson1967, 123).

Pierson’s understanding of the weight of the patriarchal family in the Brazilian social formation owes much to the work of Freyre, who, unlike Oliveira Vianna, felt family had a socially constructive role (Oliveira Vianna [1920] Reference Oliveira Vianna1938). According to Freyre, these private groups had allowed the Portuguese to adapt to the environmental and demographic circumstances of colonization and build a new civilization in the tropics (Freyre [1933] Reference Freyre2003). Holding even greater sway for Pierson was Freyre’s thesis that miscegenation in the Brazilian mansion house had been a factor of “social democratization” (Freyre [1933] Reference Freyre2003, 33). Even if the land-use system, grounded in a slave-owning, plantation-based, one-crop economy, had produced a highly stratified society, these groups had been brought together when the scarcity of white women obliged colonizers to form families through unions with the local population, forging both blood and moral ties that crossed color lines (Freyre [1933] Reference Freyre2003; Bastos Reference Bastos2006; Araújo Reference Araújo1994).

Pierson’s analysis also drew support from Freyre’s argument that patriarchalism had succeeded in cementing a new and relatively united, cohesive society based on the racial heterogeneity of its member groups, while this also benefitted white-Black dynamics, for example, by affording slaves social protection and guaranteeing vertical mobility for their children, often born from illegitimate unions with masters (Freyre [1933] Reference Freyre2003). Of particular importance were Freyre’s thoughts on the entrance of mulatos into the nineteenth century’s new liberal professions, in pace with the growth of cities and the demise of the slave-owning regime, a topic explored in depth in Sobrados e mucambos (Freyre Reference Freyre1936, chap. 7; translated as The Mansions and the Shanties, Reference Freyre, de Onís and Tannenbaum1963). As Pierson reported to Park, Freyre’s book, based on ample archival research and rich in suggestions, provided insight on the long process of racial accommodation and assimilation in Bahia.Footnote 6 Slowly but surely, this process incorporated those of mixed ethnicity into ruling white circles, often with the blessings of their former masters with whom they had personal ties, and it did so without eliciting any adverse reactions.

The upward social mobility of people of mixed color is central in Pierson’s argumentation. Considering cases of vertical mobility, Pierson optimistically affirmed that color barriers were likely to crumble in Brazil as these individuals moved into middle and upper strata, nullifying former associations between color and slave status. This gradual process of social change sprang organically from inside society itself, paving the way for former slaves and their descendants to join the world of citizenship: “Miscegenation, particularly when linked with intermarriage, resulted in bonds of sentiment between parents and offspring which hindered the arising of attitudes of prejudice and at the same time placed the mixed-bloods in a favorable position for social advancement” (Pierson [1942] Reference Pierson1967, 345). The social rise of those of mixed color through marriage further reinforced Brazil’s tendency toward miscegenation.

Some aspects of Freyre’s interpretation regarding the importance of face-to-face interaction to racial integration also coincided with that of Pierson’s professors. In the case of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery in the United States, Park, for example, felt that the armed conflict had disturbed the moral order then being built by whites and Blacks through primary contact on plantations, where interpersonal relations had kindled mutual appreciation and inhibited abstract, impersonal categorizations of individuals as mere representatives of a given race. In the old South, the traditional etiquette of race relations had been irremediably altered by the sudden, top-down change in the legal status of Blacks. Accompanied by impacts of urbanization and industrialization such as anonymity of human interactions and fierce economic competition, this opened the road for racism and institutionalized segregation (Park Reference Park1914, Reference Park1919).

It was precisely these affinities between Freyre and Park that underpinned Pierson’s emphasis on how Brazilian family ties crossed color lines to engender a racial situation that left no room for race prejudice. Although Brazilian slavery was in principle a formal institution with a purely utilitarian view of individuals, over time it melded groups on a permanent basis. As in the antebellum South, in Brazil slavery had given rise to shared feelings and experiences that made “members of the different races [identify] with each other” and “appreciate their common human character” (Pierson [1942] Reference Pierson1967, 335). This moral order, which had not been cut short by social upheaval in Brazil, still reigned in the present. Thanks to citywide networks of friends, relatives, and acquaintances, people generally had more intimate knowledge of other people’s character—a kind of knowledge that prevented external, superficial markers like color from having an impact on their judgment of someone’s skills and conduct. Blacks and whites tended to maintain social ties and see each other more as individuals than as members of abstract categories like “race.”

Contrary to the conventional interpretations of the US view of Latin America, Pierson felt that Brazil, with its traditional pattern of social relations, had been more successful than the United States in readying the path for an “order of free competition” akin to what he called, in a letter to Park, a “pure democracy,” that is, a modern brand of social organization where personal effort was the preponderant factor in social stratification (Pierson Reference Pierson1936). In Pierson’s mind, the patriarchal world of primary contact had produced a society less susceptible to the racialization of conflict that might arise from the process of social change prompted by urbanization and industrialization. Western countries thus stood to gain by deeper study of the Brazilian experience, potentially contributing to their own effort to reform their societies along democratic lines.

Rural communities and social change in 1950s Brazil

After moving to São Paulo in 1939, Pierson continued his research agenda on the cultural and societal patterns of traditional Brazil. While his interest in race relations broadened in scope to include investigations into people’s life and culture, especially in Brazil’s vast interior, his chief focus remained on the original customs shaped at the time of colonization—still found, according to Pierson, in isolated regions of the country—and on how these patterns might eventually change in response to growing rural-urban contact. In rural areas, populations remained attached to long-standing habits and beliefs, handed down practically unchanged through the generations and contrasting sharply with the dramatic shifts occasioned by the inexorable technical and productive innovations typical of urban-industrial civilization.

At the same time, Pierson began looking critically at how tradition constrained the construction of a more egalitarian modern society. In a context of economic development propitious to improving standards of living for the poor, he also became more sensitive to possible color barriers to Black social mobility. This new appreciation of how Brazil’s rural, patriarchal past played into a changing society came hand in hand with his repositioning on the race relation debate in Brazil (Figure 1).

Figure 1. In 1945, under Donald Pierson’s supervision, the Black sociologist Virginia Leone Bicudo (1910–2003) concluded the first thesis on race relations, entitled “Atitudes raciais de pretos e mulatos em São Paulo,” at the Escola Livre de Sociologia e Política (São Paulo). Collection: Brazilian Psychoanalytic Society of São Paulo (SBPSP).

The theoretical framework underpinning Pierson’s view of social change in rural Brazil, perceived as a product of increased contact with urban centers, can be traced to the work of the Chicago anthropologist Robert Redfield. After conducting a series of studies in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula in the 1930s, Redfield suggested that communities could be situated along a continuum that reflected the linear, progressive course of human social evolution, a continuum that could also be thought of in spatial terms, that is, in terms of the population’s degree of isolation. At one end of the scale lay locally based “folk cultures,” or agrarian societies, characterized by face-to-face relations, proximity, and forms of magical-religious thinking. At the other end lay “urban-industrial civilization,” with complex, heterogeneous social structures governed by impersonal relations and utilitarian interests, incessant contact among different individuals and cultures, steady technological and material change, the secularization of beliefs and behaviors, and the expansion of individuals’ mental horizons (Redfield Reference Redfield1941).

Inspired by Redfield’s approach, Pierson thought Brazil offered fertile ground for studies of social change. It was home to different types of cultures and societies (rural and urban, archaic and modern) that represented distinct eras or periods in the history of human civilization. A journey into its vast interior was like a trip back in time.

Pierson began researching rural Brazil in the mid-1940s, when he became the Brazilian representative of the Smithsonian Institution’s Institute of Social Anthropology (ISA). Accompanying the momentum of the Good Neighbor Policy, the ISA was created in 1943 as a division of the Department of American Ethnology, in Washington, DC, and assigned the mission of fostering inter-American cooperation in the field of the social sciences (Figueiredo Reference Figueiredo2009; Pierson Reference Pierson and Corrêa1987, 42; Price Reference Price2008, 112). In the early 1950s under a cooperation agreement supported by the Brazilian government, which had a strong interest in regional infrastructure development, the ISA joined with the São Paulo Free School of Sociology and Politics (ELSP) to conduct a series of investigations in São Francisco Valley communities. Born in the state of Minas Gerais and branching across the Northeast on its way to the ocean, the São Francisco River had long been deemed economically strategic because of its potential as a source of hydroelectric power and water for irrigation and also as a means of communication and transportation within its gigantic watershed (Lopes Reference Lopes1955, 30; D’Araújo Reference D’Araújo1992, 40–55). The shift in Pierson’s thought on how traditional cultural patterns could enable the emergence of modern Brazilian society is apparent in the three-volume book published about this ambitious research project (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Donald Pierson in his office at São Paulo School of Sociology and Politics, 1940s. Centro de Documentação da Fundação Escola de Sociologia e Política de São Paulo (CEDOC/FESPSP).

In his research in the São Francisco Valley, which he conducted with the aid of current and former students, Pierson identified elements of Brazilian culture and society that might represent obstacles to modernization. He believed that the modernizing changes then underway were inevitable, even desirable, and—contrary to what he had concluded in Bahia—very unlikely to coexist with traditional patterns. In his Bahian studies, Pierson had judged rural patriarchalism to be socially constructive. It could, he felt, play a positive part in the transition from a slave-owning order to a society of free competition, offering alternative routes to modernity. But in the 1950s, he came to regard tradition as reflective of archaic forms of thought and behavior that had persisted into the present, habits that refused to let go and that hampered rather than aided the country’s entrance into modernity. This meant tradition was an obstacle to postwar regional development programs in rural extension, education, and health measures, initiated under US technical assistance policies aimed at the world’s poor, rural areas. Pierson, like anthropologists such as Redfield, expressed a certain “degree of understanding and sympathy” toward communities in the Brazilian interior (Pierson Reference Pierson1972, 447), where people’s ways of life were the product of cultural heritage combined with adaptive responses to the physical and geographical environment, and not simply a result of ignorance. At the same time, the São Francisco Valley studies foregrounded problematic aspects of rural standards of living, rudimentary agriculture, archaic beliefs about health and disease, illiteracy, and the pedagogical disconnect between classroom teachings and the rural world.

Pierson’s emphasis on development meshed with the political and intellectual agenda of the early years of the Cold War, when Washington was eager to better understand the living conditions of the world’s poor, rural populations, who were considered particularly susceptible to communist ideology. This context left its mark on the theory of modernization derived from Talcott Parsons. In their analyses of social change, Parsons’s followers ultimately embraced a teleological, linear view of history in which tradition and modernity were mutually exclusive, the former yielding to the latter in a process of economic development centered on industrialization, accompanied by transformations in practices, values, beliefs, and institutions. The United States stood as the civilizational model toward which the world’s former colonies would eventually converge (Berger Reference Berger1995; Gilman Reference Gilman2003; Sztompka Reference Sztompka1993).

But in addition to the intellectual atmosphere, Pierson’s new sociological belief that archaisms had to be overcome was heavily influenced by his decade-long contact with local intellectual and reformist circles and their modernizing outlook. As Brazil underwent redemocratization following the demise of Getúlio Vargas’s Estado Novo, a new generation of Brazilian social scientists was concerned with restructuring society on more egalitarian and democratic foundations and, thus, with overcoming the country’s long-term social inequalities and authoritarian history. Imbued with sociological optimism about the fruits of Brazilian development, sociologists such as Florestan Fernandes, Luiz de Aguiar Costa Pinto, and Alberto Guerreiro Ramos believed it crucial to discover how to address the transformations caused by urbanization and industrialization so that effective change could be achieved and Brazil’s populations could eventually enter the world of citizenship (Werneck Vianna Reference Werneck Vianna1997; Villas Bôas Reference Villas Bôas2006; Botelho, Bastos, and Villas Bôas Reference Botelho, Bastos and Villas Bôas2008; Brasil Jr. Reference Brasil2013).

Pierson’s planning of his research in the São Francisco Valley, in and of itself, hints at how much these Brazilian intellectuals and reformers impacted his work. His first step was to select pairs of locations that represented the region’s gamut of economic activities (mainly agriculture and livestock grazing), its physical and geographic environments, and its varying degrees of contact with urban centers. His main goal was to analyze “the character, dimension, and intensity of incipient social change in certain areas of the Valley,” and his hypothesis fell in line with Redfield’s conclusions in the Yucatán, that is, that the direction and degree of change in a given community could be assessed by ascertaining where the community lay along the folk culture-civilization continuum.Footnote 7

Pierson adopted the viewpoint for which Redfield is best known, that is, that tradition and archaisms had no place in urban-industrial civilization, which expanded as old rural, community worlds atrophied.Footnote 8 These assumptions about social change were nonetheless closely attuned to the concerns of Brazilian sociologists, who saw a good part of local traditions as linked to the country’s authoritarian, unequal past and who believed that modernity afforded an opportunity to reorganize society along entirely new principles. This desire to leave the past behind lay at the root of a trend in Brazilian sociological theorization that sought to unravel how traditional modes of behavior were able to renew themselves during the process of modernization, preventing modernity, with all its positive political, cultural, and social consequences, from fully emerging. This was a key investigative concern for sociologists such as Costa Pinto and Fernandes, who questioned dualist, disjunctive models like the theory of modernization, which viewed the traditional and the modern as mutually exclusive patterns of social organization, with the first being replaced by the second in due time. As history showed no signs that this would be the case for Brazilian society, some of its scholars started wondering why urbanization and industrialization were not accompanied by a truly new ordering of social relations and exercise of power in Brazil, consonant with the ideals that had guided classic forms of bourgeois revolution in the beginnings of the modern era (Fernandes [1964] Reference Fernandes2008; Costa Pinto Reference Pinto and de Aguiar1953, Reference Pinto and de Aguiar1963).Footnote 9

It was with these theoretical concerns in mind, about social change and its true scope and expression in Brazil, that Pierson studied the populations and forms of social and cultural organization in the São Francisco Valley. Subsequent to Portuguese colonization and conflict-rife encounters with local Indigenous peoples, the racially mixed human groups that established themselves in this region clung to magical and religious beliefs and practices regarding food, health, work techniques, and labor regimes that apparently derived from a blend of popular European peasant culture dating from the Middle Ages and the most rudimentary Indigenous and African traditions. Vast tracts of land lay in the hands of a few families, while large numbers of farmers remained landless and routinely migrated. Birth and death rates were high, especially infant mortality; most dwellings were wattle and daub; and subsistence farming, hunting, and fishing constituted the main economic activities. Family and kinship ties played a decisive role in shaping individual behavior, rules of social etiquette were well defined and rigid, and large landowners held great sway in political life and provided protection and assistance to the poorest farmers through clientelist networks. While the local elites followed events in distant urban centers closely, life generally transpired within narrow mental horizons (Pierson Reference Pierson1972).

According to Pierson, change was coming to this social and cultural world, where things had been relatively static since the arrival of the earliest colonizers. As the Paulo Afonso hydroelectric power plant expanded electricity distribution, new agricultural techniques improved local production. Similarly, exchange grew as roads were opened and air services extended. In commerce, regionally manufactured goods began to replace the handcrafted ones produced on farms. Broader use of radio enhanced communications between local communities and the world beyond. Keeping pace, the division of labor and types of occupations grew more complex; traditional ties between landowners and rural workers were replaced by more formal, impersonal relations; money became more important in trade and other interactions; and new urban professional categories appeared, such as physician, lawyer, civil servant, and teacher (Pierson Reference Pierson1972).

Change was also apparent in the cultural field. While folk medicine still predominated, it began disputing space with a set of “urban, more sophisticated” techniques and ideas (Pierson Reference Pierson1972, 452). Growing numbers of people felt antivenin serum was more reliable than curadores de cobra, or snake healers, and the public was increasingly skeptical about healers’ powers in general. In less isolated areas, there was excitement about government initiatives to fight the malaria-transmitting mosquito. These trends seemed to dovetail with the efforts of the government’s São Francisco Valley Commission to supply clean running water to riverside populations, even though, in the mind of inhabitants, scientific and secular notions of health still coexisted peacefully alongside traditional beliefs (Figueiredo Reference Figueiredo2009, chap. 3).

In the realm of behavior and social organization, Pierson saw growing individualism and a questioning of traditional kinship pride that suggested the family was losing its once nearly absolute power over the lives of its members. In the political arena, kinship was no longer enough when it came to securing and holding onto local power. Large farmers and ranchers watched their influence diminish as new leaders surfaced among the teachers and physicians who had trained in large urban centers. These new leaders could exercise greater independence in the political arena because they were less bound by familial obligations. Decreased violence and coercion through Brazil’s coronel system signaled changes toward political democracy (Pierson Reference Pierson1972, 290). The new leaders’ loyalty to community began to supersede loyalty to political factions linked to family groups, leaving more room for “less easily controlled voters” (including the poor) to enjoy effective political participation (Pierson Reference Pierson1972, 291).

For Pierson, these changes suggested that a traditionally rural social order “guided by hierarchy” was gradually being replaced by one based on “more egalitarian principles, with increased economic, political, and sociological differentiation” (Pierson Reference Pierson1972, 462). The characteristics of the emerging new society—industrialized, grounded in more rationalized and greater economic production, and displaying more secular beliefs and democratic values—fed into a vision of modernity similar to that expressed, implicitly or explicitly, by modernization theory. But the changes Pierson perceived, especially his emphasis on the realization of democracy, also converged with certain expectations about the reordering of the Brazilian society that were held by local postwar intellectual and reformist circles and that were enthusiastically embraced in the 1950s, when economic growth and industrialization seemed to suggest that Brazilians might make true social and political strides.

Pierson underscored various dimensions of modernization beyond transformations in technique and productive activities, because he believed all these dimensions were vital to achieving change. In this sense, he was in close step with the sociological views that stressed the systemic nature of society and culture, where interdependent parts constituted an organic whole. According to this theory, behavioral norms and religious beliefs about health and the body did not change swiftly or easily because they were heavily laden with the moral and emotional weight of tradition. But since they were part of a cultural whole, their failure to change could have negative repercussions on other spheres of social life, possibly impelling a return to old habits.

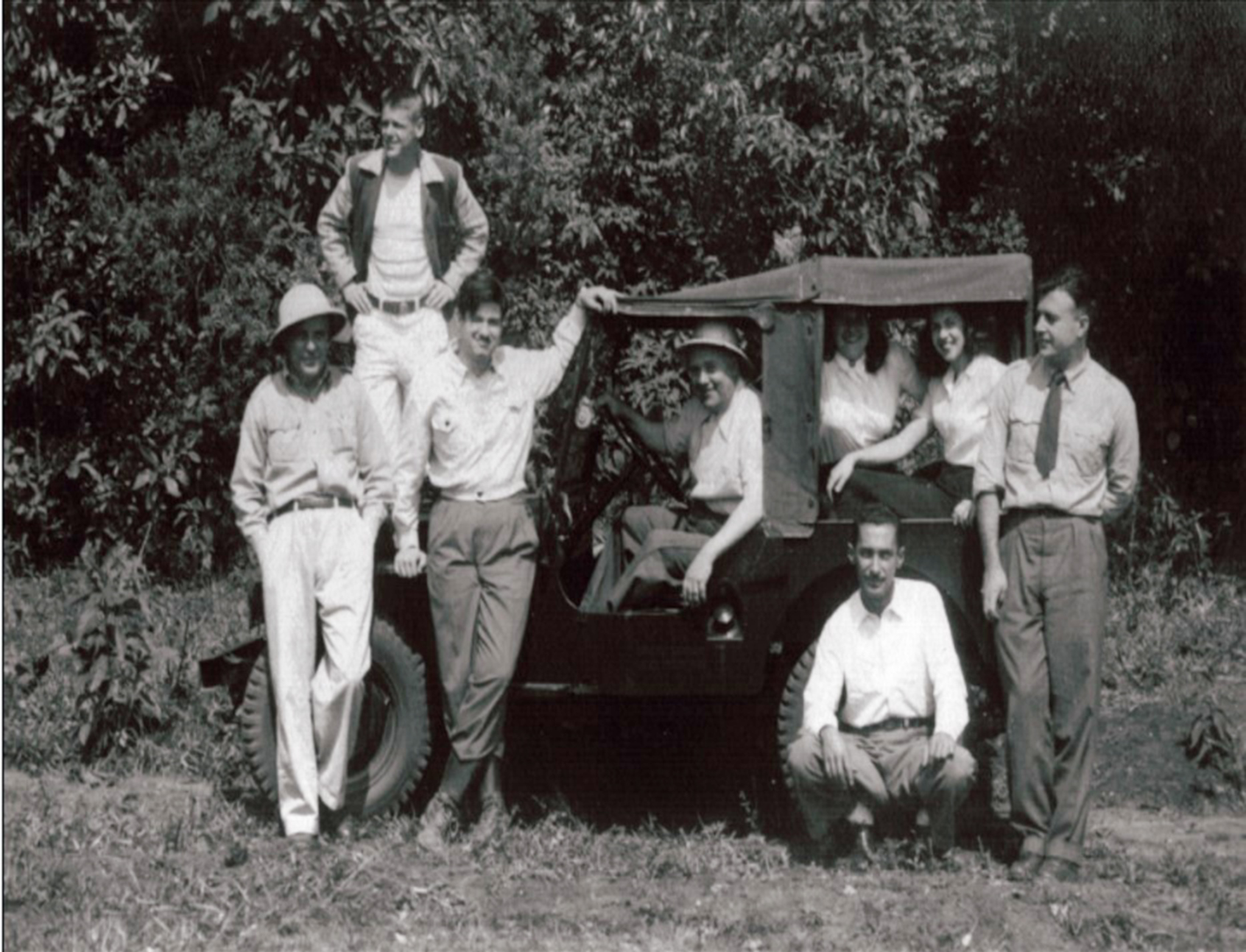

As Pierson argued, the social sciences had something special to offer here. By furnishing information on communities’ ways of life, traditions, and customs, social scientists could help planners and administrators introduce new practices in hygiene, health, and labor. Above all, communities themselves had to be involved in local development projects through “democratic planning,” so that values and behavior would be modified via social participation (Pierson Reference Pierson1972, 474; Foster Reference Foster1951). Drawing from experiences in the implementation of health programs on the world’s peripheries, such as those of anthropologists like the former ISA director George Foster, Pierson argued that tradition was so tenacious that it would unlikely be vanquished by intervention through force, such as the top-down social engineering projects identified with totalitarian regimes. When Pierson urged the participation of local populations, however, he was no longer thinking that their traditions might make a positive contribution to the implementation of change; rather, he assumed that community involvement was the best strategy for convincing those targeted by these programs to adopt new values and practices. In other words, working through and together with local cultures, rather than confronting them, would be the most effective means of transforming them according to modern patterns (Figure 3).Footnote 10

Figure 3. Donald Pierson and his research team during a field trip to the rural community of Araçariguama, São Paulo, 1940s. Centro de Documentação da Fundação Escola de Sociologia e Política de São Paulo (CEDOC/FESPSP). Left to right: Mauricio Segall, Carlos B. Teixeira, Kalervo Oberg, Donald Pierson, Juarez Brandão Lopes, Mirtes Brandão Lopes, Adelaide Hamburger, and Fernando Altenfelder.

The UNESCO Race Relations Project and Pierson’s new sociological perspective

In his work in the São Francisco Valley, Pierson did not tackle the problem of how Brazil’s traditional race relations pattern could be altered through modernizing changes in the region, but he ended up addressing the issue in the context of the UNESCO Race Relations Project, a set of investigations in Brazil carried out in the early 1950s under the auspices of the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization through its newly created Department of Social Sciences. This research was conducted at a time of doubt about the scientific validity of the concept of race, when a drive was on to fight racism and elucidate the roots of the conflicts between peoples and nationalities that had unleashed the war and the Holocaust. Echoing the notion that Brazil offered a unique laboratory of experiences in race and cultural contacts, the department decided to sponsor inquiries on race relations in different regions of the country. While not directly involved in the project—which included Charles Wagley, Thales de Azevedo, René Ribeiro, Roger Bastide, Florestan Fernandes, and Costa Pinto—Pierson was invited to serve as a consultant to the team of researchers working in São Paulo (Maio Reference Maio2001).

From the earliest drafts of the UNESCO project agenda, criticisms were flung at Pierson’s work in general, including the failure of his methodology to detect veiled forms of racial bias in Bahia. Bastide and Fernandes in São Paulo and Costa Pinto in Rio de Janeiro claimed Pierson’s approach had been insufficient because it was unable to capture the nuances and subtleties of racism in Brazil or reveal the asymmetries and violence characterizing Black-white relations. They argued that this racism lay hidden under the cover of the rural, slave-owning world’s benevolent old patriarchalism, which was eroding in urban and more industrialized areas. This threatened to introduce new, specifically racial conflicts, as Blacks began their ascent up the social and economic ladder and encountered barriers to the white world (Bastide and Fernandes Reference Bastide and Fernandes1955; Costa Pinto Reference Pinto and de Aguiar1953).

Pierson, however, seemed to hold to his hypotheses from the Bahia study, arguing that the UNESCO studies suggested his conclusions were applicable to Brazil as a whole, especially his ideas about the nature of race prejudice and the type of social stratification prevailing in the country, a multiracial class society rather than a caste society (Pierson Reference Pierson and Lind1955, 450). While Pierson continued to openly defend his interpretation, the way he chose to qualify his arguments suggests how much his thinking had moved toward that of Brazilian sociology in the 1950s, then intent on overcoming the country’s historical social inequalities, achieving democracy, and including the masses in the world of citizenship. This can be gleaned from the paper Pierson presented at the Conference on Race Relations in World Perspective, organized in Honolulu by Andrew Lind, another of Robert Park’s former students. Held in late 1954, some months before the Bandung Conference, when anticolonial independence movements in Africa and Asia were gaining center stage in international debates, the event was attended by scholars of race relations from around the world and was intended to encourage the use of the comparative prism when exploring the factors behind interethnic tensions (Lind Reference Lind and Lind1955; Conant Reference Conant1955).

In his talk, which examined Brazil’s race situation overall, Pierson reviewed his study on Salvador as well as the UNESCO project, endeavoring to show how the research team’s conclusions corroborated his own. But, in contrast with the research agenda he had presented at the end of his work in Bahia, written in the late 1930s, Pierson now urged deeper exploration of topics directly related to status hierarchies among ethnic groups, such as the aesthetic value and prestige of European traits among Brazilian people (Pierson Reference Pierson and Lind1955, 437). Similarly, in regard to the cases of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, he said that new hypotheses should be included to account for possible changing tendencies in the country’s “original racial situation.” These changes were occasioned by “new forces” of the modern world tied primarily to a “long-range trend” for the “underprivileged classes [to ascend] into increasingly greater economic and political power” in the wake of industrialization, urbanization, and the advent of new professional and educational opportunities for the Brazilian poor, where the Black population was concentrated (Pierson Reference Pierson and Lind1955, 460–461).

Pierson’s new concern with racial inequalities in Brazil came hand in hand with doubts about his original view regarding a smooth process of integration of Blacks into the middle and upper social layers of the country. While he had formerly underlined local society’s permeability to Black vertical mobility in Bahia, Pierson now highlighted the rigid class lines separating the different strata. This might, he argued, explain how color consciousness was taking shape in Brazil amid growing social mobility. Pierson also pointed to the asymmetrical nature of traditional personalized relations between Blacks and whites, in which the former often saw themselves as subordinated to the latter, their old masters. Concurrently, he perceived big city anonymity as a force capable of challenging old hierarchies, endowing people of color with “new conceptions about themselves and others” (Pierson Reference Pierson and Lind1955, 461). Pierson’s recent emphasis on tensions, conflicts, and their potential racialization in Brazil was characteristic of the global political and ideological disputes of the 1950s, when many intellectuals were concerned about the possible exacerbation of interethnic conflicts in the wake of anti-colonialist movements and of growing demands to raise the living standards of both rural and urban poor (Lind Reference Lind and Lind1955).

Pierson’s repositioning within the Brazilian race debate was also symptomatic of the shift in his sociological thought, especially how he viewed relations between tradition and modernity. Rural, patriarchal Brazil, which, according to his 1930s research, had left an important legacy for the construction of a modern social order in the country, was now viewed not only as the opposite of modernity but as unlikely to survive the torrent of change. As Pierson now had it, in line with the aspirations of 1950s Brazilian sociology, modernization represented much more a departure from the country’s traditions than a gradual transformation of the past.

Conclusion

An examination of Donald Pierson’s work on Brazilian society and culture sheds light on streams of thought and authors who took part in major, yet little-known theoretical debates on modernization. The transnational nature of his work, which entailed complex intersections of US and Brazilian intellectual traditions, likewise affords us the opportunity to revisit traditional understandings of the North-South flows that guided sociological knowledge-making processes in the past. While the theoretical and conceptual schemes developed by Robert Park and Robert Redfield remained a lodestar for Pierson in his research and reflections on the process of social change in Brazil, it was from the perspective of significant dialogues and proximities with the interpretations and concerns of Brazilian intellectuals that he explored how the country’s past and traditions might affect the construction of a modern social order. If his study of Salvador in the 1930s suggested, in tune with Gilberto Freyre, that patriarchal, rural Brazil could serve as a point of support in building a democratic, racially integrated country, Pierson evaluated the products of this same archaic world under a different prism during his São Francisco Valley research. The weight of kinship ties and the clout of large landowners and their families in local social and political life, which structured relations hierarchically according to particularist principles, were now seen as hindering the emergence of an economically more developed and also egalitarian and republican order, capable of guaranteeing the inclusion of the rural masses into the world of citizenship. This also led the sociologist to a reappraisal of the democratic impulses coming from traditional race relation patterns, forged in the rural and familistic world of slavery, and to a new concern about the possible conflicts triggered by white resistance to Black social mobility in more industrialized cities. Pierson’s shift in the 1950s was in tune with the aspirations of Brazilian sociologists and became apparent in the context of the UNESCO Race Relations Project and at the 1954 Honolulu Conference on Race Relations. His new views accompanied the transformation in the globe’s political and intellectual contexts and the ascendance of new voices on the social science scene in Brazil. If social change had once appeared to occur slowly and draw nourishment from tradition, now Brazilian society needed to break with the past to achieve modernity.