No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

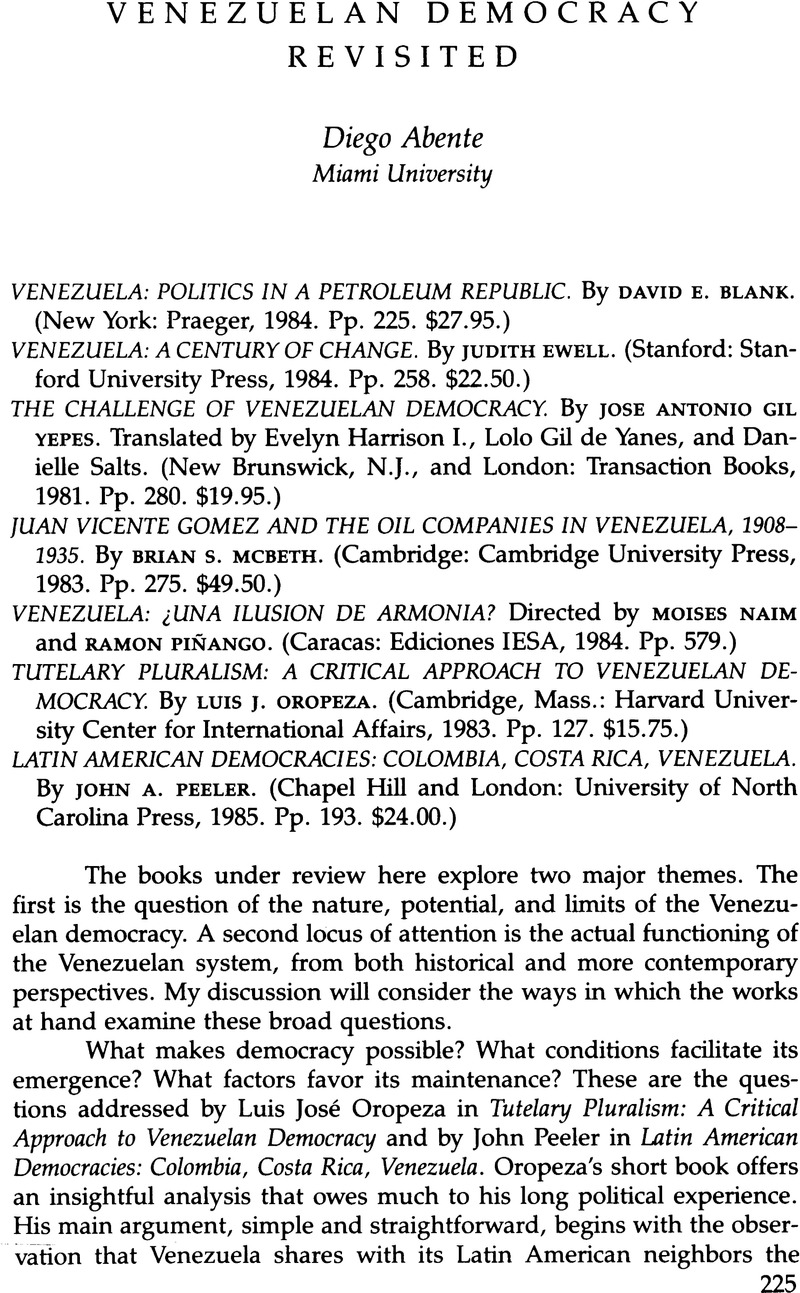

Venezuelan Democracy Revisited

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1987 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. I have found the same to be true in my own analysis of tax reform in Venezuela. See Diego Abente Brun, “Economic Policy Making in a Democratic Regime: The Case of Venezuela,” Ph.D. diss., University of New Mexico, 1984.

2. An example is the excellent comparison of the Argentinian and Chilean cases made by Karen L. Remmer in Political Competition in Argentina and Chile (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1984).

3. See Terry Karl, Petroleum and Political Pacts: The Transition to Democracy in Venezuela, Wilson Center Working Paper no. 107 (Washington, D.C.: Latin American Program, The Wilson Center, 1982).

4. In the case of the neoconsociarional democracies under study (especially Venezuela), one could hypothesize the development of elite coalescent behavior in game-theory terms as the result of a change in players' strategies, a shift away from a dominant strategy that consistently yields Pareto-deficient outcomes toward one that is susceptible of producing Pareto-optimum outcomes. One would then have to examine just what generates a shift in political strategies, then how and why such a shift occurs, and hence identify the conditions under which this kind of scenario is likely to emerge.

5. Perhaps even more important than the stereotypes is the subtler epistemological assumption underlying them. In fact, these culturalist perspectives tend to embrace a methodological individualism that reduces the complexities of social aggregates to the inner characteristics of the individual or individual values. Some of the far-reaching implications of this approach are well known, thanks in part to the works of Friedrich von Hayek and Milton Friedman. Less well-known, but equally important, are the political implications of this reductionistic perspective for the understanding of Latin American societies. In this context, methodological individualism tends to provide the theoretical rationale for the simultaneous pursuit of immobilism in the social sphere, “freedom” in the economic realm, and authoritarianism in the political arena—all of these ironically coming from no less than the apologists of the “open society” and their Latin American epigones.

6. Cesar Balestrini, Los precios del petróleo y la participación fiscal de Venezuela (Caracas: Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Sociales, Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1974), 35–36.

7. Alejandro Portes, “Modernity and Development: A Critique,” Studies in Comparative International Development 9 (Spring 1973):251.

8. James L. Payne, Patterns of Conflict in Colombia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968). For an excellent critique, see Albert Hirschman, “The Search for Paradigms as a Hindrance to Understanding,” World Politics 22, no. 3 (Mar. 1970):329–43.