INTRODUCTION

In recent years, numerous national governments have attacked international courts (ICs) with a human rights mission.Footnote 1 Burundi withdrew from the International Criminal Court (ICC), the Philippines is in the process of withdrawing, and Gambia, Kenya, and South Africa have threatened to follow (Alter, Gathii and Helfer Reference Alter, James and Laurence2016). Venezuela dropped out of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR), the Dominican Republic appears to have one foot out the door (Soley and Steininger Reference Soley and Silvia2018), and in 2012 a group of states sought to rein in the power of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACmHR). That same year, the United Kingdom led a similar effort against the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) (Madsen Reference Madsen2016).

As states have sought to weaken or simply withdraw from various international human rights judicial bodies, scholars have turned their attention to “backlash” (Voeten Reference Stiansen and Erik2020). Backlash attracts attention in academic and practitioner circles because it poses far more significant dangers to the integrity of ICs than a leader’s occasional sovereigntist tantrum, criticism of a court’s work, or refusal to comply with specific rulings. As Alter and Zürn (Reference Alter and Michael2020, 2) put it, “backlash politics” have a “(1) retrograde objective as well as (2) extraordinary goals and tactics that have (3) reached the threshold of entering mainstream public discourse.” Backlash against ICs is institutional: it targets a court’s formal authority, that is, its range of competences and jurisdictional reach. Following Sandholtz, Bei, and Caldwell (Reference Sandholtz, Yining, Kayla, Brysk and Stohl2018, 159), backlash “can include a range of actions, from pruning a court’s competences, to withdrawing from a court’s jurisdiction, to shutting a court down altogether.” The backlash we have in mind is therefore orchestrated by members of the executive or legislative branches of states under a court’s jurisdiction, who are the ones who draft, sign, amend, and ratify the legal instruments that give life to and govern the behavior of ICs.Footnote 2

Scholarship on backlash has focused mainly on its definition and causes. This article takes a different tack, starting with the observation that the human rights ICs that have been subject to backlash have, so far, been able to avoid reductions in their authority.Footnote 3 We know from institutional theories that institutions display a degree of stickiness or inertia. In other words, institutions often remain in place even as the world around them changes, and even when they are subject to attacks by those who created them. We refer to this phenomenon as resilience, a term that signals continuity and steadfastness in the face of external pressures. In the context of this article, resilience therefore refers to a court’s ability to avoid reductions in its authority or competences. We present a framework for identifying and analyzing the sources of resilience in human rights ICs, that is, the factors that can enable them to withstand backlash and emerge from these political struggles with their authority and competences intact. We explore the framework in the context of the Inter-American System of Human Rights (IASyHR).Footnote 4

To be sure, stating that a court is resilient does not necessarily imply that it never changes or adapts to environmental cues, especially when it finds itself under extreme duress. In fact, both international and domestic courts tend to be painfully aware of their institutional precarity, and often act strategically in the face of external constraints, pressures, or attacks. It is well known that judges wary of the prospect of noncompliance or retaliation rule in ways that minimize risk (Vanberg Reference Vanberg2001; Reference Vanberg2005; Botero Reference Botero2018), departing from (or watering down) preferred jurisprudential outcomes (Ferejohn Reference Ferejohn1998; Epstein and Knight Reference Epstein and Jack1998; Epstein, et al. Reference Epstein, Jack and Olga2001; Helmke Reference Helmke2005). Common tactics include resorting to forms of argumentation that narrow the scope of legal outcomes (Baum Reference Baum2006); affording politicians or bureaucrats ample degrees of freedom for ruling implementation (Spriggs Reference Spriggs1997; Staton and Vanberg Reference Staton and Georg2008); or granting victories to different parties in the same case or across related cases (Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg, Kapiszewski, Silverstein and Kagan2013).

For example, Madsen (Reference Madsen2007; Reference Madsen2012; Reference Madsen2016) has argued that until the mid-1970s the ECtHR, constrained as it was by the lack of a robust corpus of international human rights law and a limited membership, adopted this cautious approach to legal construction. Its judges displayed a high degree of statesmanship, only gradually entrenching the Court’s authority and emboldening its jurisprudence. More recently, leading up to the 2012 Brighton Conference, a few states criticized the ECtHR for insufficient deference to member states and launched (ultimately unsuccessful) efforts to constrain the Court (Glas Reference Glas2020). In response, the Court may have reduced the rate at which it found violations by consolidated democracies that had been critical of it (Madsen Reference Madsen2016; Stiansen and Voeten 2020). The IACtHR, in light of the acrimonious debate sparked by its initial formulation of the conventionality control doctrine, which mandated national judges to review legislation in light of the American Convention on Human Rights and relevant jurisprudence, used formal and informal mechanisms to soften its implications (Gonzalez-Ocantos Reference Gonzalez-Ocantos2018).

This capacity to adapt “at the margins” in order to minimize the consequences of external pressures or attacks and preempt new ones, is one way in which ICs retain their formal authority, competences, and jurisdictional reach during moments of political contestation. But for strategic adaptation or deference to remain marginal and not morph into permanent subservience or institutional atrophy, especially once backlash has already materialized, ICs need more than good political instincts. They need allies. Taking cues from research on the creation and functioning of ICs and institutionalist theory, our central contention is that resilience is fundamentally a function of a court’s embeddedness in domestic institutions and networks and with domestic actors (Helfer Reference Helfer2008; Alter Reference Alter2014; Sandholtz Reference Sandholtz2015). In the absence of embeddedness, strategic concessions or displays of deference are unlikely to be enough to neutralize or appease angry principals. In other words, under conditions of low embeddedness we are more likely to observe successful attempts at weakening or destroying a court’s institutional powers despite timely attempts to adapt.

We focus on the following types of interconnections between an IC, states under its jurisdiction, and domestic actors and constituencies: (1) incorporation of international treaties into domestic law; (2) presence of independent courts; (3) acceptance and use of IC jurisprudence by domestic judiciaries; (4) presence of strong accountability agencies supportive of human rights, in particular, national human rights institutions (NHRIs); (5) incorporation of international law into legal training and academic research; and (6) presence of civil society organizations (CSOs) that rely on ICs and their jurisprudence (Soley and Steininger Reference Soley and Silvia2018, 254). These interconnections indicate the domestic embeddedness of international human rights law. They unleash social and institutional forces that reduce the likelihood that executive and legislative actors will attack ICs and limit their fire power if they do decide to attack. Because embeddedness refers to how an IC has entrenched itself in other institutions or networks, it helps account for why interested actors mobilize in its defense, disarming or dissuading the attackers, and amplifying or legitimizing a court’s arguments against a fundamental reduction of its competences. Put differently, embeddedness shapes the interests of actors who are structurally connected to the Court, and hence their willingness to mobilize to protect those interests.

We do not argue that an IC that has developed multiple strong domestic linkages can weather any storm. International institutions, including courts, can never be invulnerable to widespread, large-scale shifts in state interests and preferences. If enough states decide that they no longer want or need a particular IC, that court cannot survive, as shown by the demise of the South African Development Community Tribunal (Alter, Gathii, and Helfer Reference Alter, James and Laurence2016). But the larger the number and the greater the diversity of an IC’s sites of embeddedness with actors and within institutions of the legal complex, the greater its resilience is likely to be. Understanding the nature and sources of IC resilience will become increasingly important if resurgent authoritarianism, populism, and nationalism continue to erode states’ support for international institutions.

EMBEDDEDNESS AND INSTITUTIONAL RESILIENCE

Numerous scholars have emphasized the importance of domestic connections for the effectiveness of international institutions in general, and the human rights regime in particular. Reacting to realist skepticism about the structuring power of international law, they have shown that in the absence of a world Leviathan, it is domestic actors and processes that give bite to the international legal order. “Enmeshing” (Keohane Reference Keohane1992) international law in domestic institutions is a key pathway to making commitments between states self-enforcing and compliance routine (Koh Reference Koh1996; Goldstein, et al. Reference Goldstein2000; Keohane, Moravcsik, and Slaughter 2000; Helfer Reference Helfer2008). International rules “alter the incentives, not merely for states conceived of as units but for interest groups, organizations, members of professional associations, and individual policymakers within governments” (Keohane quoted in Koh Reference Koh1996, 2633, ft. 176).

Some actors value international rules or think they can benefit from local enforcement, leading them to champion treaty ratification (Moravcsik Reference Moravicsik2000; Pevehouse Reference Pevehouse2005; Alcañiz Reference Alcañiz2012) and to become “compliance partners” (Kahler Reference Kahler2000; Alter Reference Alter2014). For instance, research shows that when groups with significant electoral influence support international legal standards, leaders comply with those standards (Dai Reference Dai2005). If certain audiences value a treaty, abiding by it may embellish a president’s reputation (Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2014), boosting her political leverage. Social movements also exploit the “expectations gap” generated by membership in certain human rights treaties to pressure states to change their practices (Risse, Ropp, and Sikkink Reference Risse-Kappen, Ropp and Sikkink1999; Simmons Reference Simmons2009). Finally, ordinary courts are sometimes attracted to international sources of law, including the jurisprudence of ICs, because they empower them vis-à-vis national governments or their superiors in the judiciary (Helfer and Slaughter Reference Helfer and Anne-Marie1997; Alter Reference Alter2001).

When it comes to ICs, the literature on the domestic roots of regime effectiveness tends to focus on issues of compliance, in particular compliance with specific rulings (Alter Reference Alter2001; Reference Alter2014). Given the absence of robust means to guarantee ruling enforcement (Staton and Moore 2011), scholars observe great variability in compliance (Hawkins and Jacoby Reference Hawkins and Wade2010; Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2014). Moreover, international judges care about compliance “because it conforms to their understanding of who they are and what law is” (Huneeus Reference Huneeus, Romano, Alter and Shany2014; 441) and helps build judicial authority (Kapiszewski and Taylor Reference Kapiszewski and Matthew2013).

Yet, to understand the resilience of ICs we need to look beyond their ability to achieve compliance. ICs are usually able to survive and maintain influence amidst some level of noncompliance. Indeed, some degree of noncompliance with rulings is a permanent reality for all international human rights courts. By contrast, the kind of backlash that motivates this article is a more serious affair. If, as international relations scholars have shown, ICs depend on domestic actors for their proper functioning and effectiveness, open hostility from a national leader or parliament can become an existential threat to judicial authority. We are therefore interested in understanding how an IC’s roots in domestic institutions and linkages to domestic actors can enhance resilience in the face of these extraordinary attacks on their authority by domestic elites.

Historical institutionalism offers a useful foundation because it theorizes both institutional continuity and endogenous processes of institutional change (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2000; Pierson Reference Pierson2004; Streeck and Thelen Reference Streeck, Kathleen, Streeck and Thelen2005; Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney, Kathleen, Mahoney and Thelen2010; Rixen and Viola Reference Rixen, Lora, Rixen, Viola and Zürn2016; Zürn Reference Zürn, Rixen, Viola and Zürn2016; Fioretos Reference Fioretos2017). Given our interest in resilience, the focus on continuity—explaining why institutions are resistant to authority-reducing change even when the conditions that led to their creation have altered—is apropos.

The core theoretical concept for our analysis is institutional “embeddedness.” Institutions are often embedded in “a broader institutional complex or ‘configuration’” (Büthe Reference Büthe, Rixen, Viola and Zürn2016, 41–42; see also Pierson and Skocpol 2002). The more embedded an institution is in frameworks, associations, and networks of other institutions, the more resistant it will be to attempts to challenge or modify it (Jepperson Reference Jepperson, Powell and DiMaggio1991, 151). Embeddedness increases with centrality and time. The more central an institution is within its context, the more numerous are other institutions that interact with, rely on, or support it. The longer an institution has been in place, the more “other practices have adapted to it” (Jepperson Reference Jepperson, Powell and DiMaggio1991, 151–52). Furthermore, the more an institution is embedded in broader social and cultural structures—including, for example, common “principles and rules” or “exogenous (transcendental) moral authority”—the more resistant to change efforts it will be (ibid.). Finally, legalization is in itself a form of embeddedness. As Moe argues with reference to domestic arrangements, institutions that are “embedded in the law will be durable” because “the legal status quo is so difficult to change” (Moe Reference Moe1990, 242).

For example, the key institutions of the IASyHR, the IACtHR and the IACmHR, would register as highly embedded on each of those dimensions.Footnote 5 They are centrally located within the regional human rights context, functioning as custodians of the region’s principal human rights instrument (the American Convention of Human Rights (ACHR)) and as a central point of reference for various actors in the human rights domain. Both institutions have also been in place for a sufficiently long time—over half a century in the case of the Commission, and more than thirty years in the case of the Court—that other actors and practices have adapted to them. They are also embedded within the international human rights regime, which has the character of a transcendental moral authority given its anchoring in universal rights and the inherent dignity of every human being. Finally, the IASyHR has become embedded in domestic legal institutions, networks, and organizations—the focus of our framework.Footnote 6 That embeddedness, we argue, constitutes a source of resilience for the IACtHR and IACmHR.

We identify six sources of embeddedness of ICs within state institutions and in domestic society, which can help resist and survive efforts by presidents and legislatures to trim IC authority and competences: (1) incorporation of relevant international treaties into domestic law; (2) presence of independent courts; (3) acceptance and use of IC jurisprudence by domestic judiciaries; (4) presence of strong accountability agencies supportive of human rights, in particular, strong NHRIs; (5) incorporation of relevant international law into legal training and academic research; and (6) presence of CSOs that rely on ICs.

These domestic sites of embeddedness and the IASyHR have shaped each other in a recursive process. Receptive domestic constituencies have expanded the influence of the IASyHR by carrying the jurisprudence of the Commission and the Court into domestic contexts, and Inter-American institutions have strengthened the hand of those domestic actors by providing them with normative and legal tools they could use in pressing for domestic change. In particular, as Latin America began in the 1980s to emerge from a period of authoritarian rule and large-scale state atrocities, the mutually reinforcing efforts of domestic activists and the IASyHR became integral parts of the regional movement toward democracy, human rights, and the rule of law (Huneeus and Madsen Reference Huneeus and Mikael2018; Lutz and Sikkink Reference Lutz and Kathryn2000).

Internal state sites of embeddedness include the constitutional text, NHRIs, and the judicial branch. These sources of embeddedness strengthen and formalize the relationship between key state officials and international human rights law (Soley and Steininger Reference Soley and Silvia2018, 255), routinize attention to human rights standards in policymaking and judicial decision-making processes, and sound official alarm bells when politicians challenge or ignore such standards. Nonstate sites of embeddedness, by contrast, can be found in the realm of civil society. In particular, human rights NGOs and law schools are instrumental in nurturing legal cultures that are more (or less) aware, respectful and welcoming of international human rights law and courts. In so doing, they create a fertile pipeline of committed aspirants to positions in the aforementioned internal sites of embeddedness. Furthermore, NGOs and universities play a key role in supplying social support in the event of backlash from executive and legislative actors. Overall, the presence of potential allies inside and outside of state structures makes it harder for political elites within states to speak in a unified voice when it comes to backlash. Apart from undermining the political resolve behind such efforts, ICs can leverage this dissonance to undermine the case for institutional weakening, and rely on domestic allies to legitimize the status quo and produce counterproposals for IC reforms that are more cosmetic.

The extent to which these forms of embeddedness bolster IC resilience is obviously a function of the strength of formal institutions (e.g., the legal prerogatives of NHRIs or the independence of constitutional courts), as well as of the levels of organizational density in civil society (e.g., number of resourceful NGOs or human rights legal clinics). But more informal processes and norms also play a role because they shape the predispositions and practices of the actors that populate formal institutions and organizations. In fact, it is often the interaction between formal/organizational and informal forms of embeddedness that bolsters resilience. For example, strong constitutional courts staffed by judges who are ignorant of international human rights law, or who resist turning to this source of law as part of their daily routines, are unlikely to offer the kind of domestic roots or support that an IC needs. This is true both in terms of internalizing acceptance of, or acquiescence to, international jurisprudence and mobilizing support in the event of sovereigntist attacks against international adjudication. Similarly, the place of human rights law in legal education, and perhaps by implication the extent to which it is invoked as a matter of course in juridical discourse and not considered foreign or invasive, is likely to be more prominent in the presence of constitutions that formally elevate the status of human rights treaties in the domestic legal order.

Furthermore, resilience is more likely when the institutional and social processes that favor embeddedness are replicated across all or most of the countries that fall under the jurisdiction of an IC. There are two reasons for this. First, regional embeddedness can isolate those national leaders who advocate backlash. Changing international agreements to trim the authority and competence of a court requires some degree of consensus. This is harder to achieve when embeddedness is widespread rather than geographically limited. For example, if domestic NGOs mobilize to defend an IC in a large number of countries, they may prevent a critical mass of governments from joining the backlash or remaining indifferent to it. Moreover, gaps in embeddedness strengthen the argument of national leaders seeking to limit the intrusiveness of international courts and other institutions. As we shall see in our main case study, a crucial argument of leaders critical of the Inter-American Commission during the 2011–2014 backlash episode was the fact that the United States and Canada never accepted the jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court. Uneven embeddedness opened the door for the politics of “hypocrisy.” Second, regional embeddedness matters because it helps aggregate national support structures into transnational networks. These networks, which often include international NGOs, are essential when it comes to defending embattled ICs because they can speak louder than individual domestic organizations. They also share information, expertise, and legal strategies across borders, and are thus better able to coordinate advocacy efforts in the summits or intergovernmental fora where backlash-inspired reforms are usually debated.

We make a conscious decision to locate sources of resilience among institutions and elite actors that make up the “legal complex” (Halliday, Karpik, and Feeley Reference Halliday, Lucien and Malcolm2007). To be sure, public opinion, in particular mass attitudes toward international courts, can help catalyze or minimize backlash (Dinas and Gonzalez-Ocantos Reference Dinas and Ezequiel2021). For example, in the literature on domestic judicial politics, some authors argue that should interbranch conflicts occur, public support for courts provides an important source of leverage vis-à-vis presidents and legislatures (Vanberg Reference Vanberg2005). Public opinion could thus be a source of resilience for the IASyHR, to the extent that the System and its work are recognized and valued by the broader public. In other words, it can become embedded in society at large. By the same token, in an age of rising populism, broad public disapproval of international institutions could enable governments to mount backlash attacks on those institutions. That said, the incorporation of public opinion in our framework is not feasible. Most crucially, systematic, cross-temporal, cross-national public opinion data on attitudes toward the IASyHR do not exist, which would make any arguments regarding it purely speculative.

Moreover, the analytical power of our framework is unlikely to suffer by the exclusion of public opinion, for several reasons. First, though the public can in principle play a central role in legitimizing backlash against, or support for, international courts in elections or referenda, citizens are often “cue takers” whose views (including toward ICs) are shaped by elite discourse (Zvobgo Reference Zvobgo2019). Second, “diffuse institutional support” (Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Gregory1995) for the IASyHR in the broader public is likely to build gradually and over an extended time. This is especially true for the IASyHR, where even the most involved states have had only a few dozen cases decided by the Court over a period of some forty years. Finally, attitudes toward regional courts tend to be highly derivative of attitudes toward other institutions, including domestic courts (Voeten Reference Voeten2013). In any case, public attitudes toward ICs are an area begging for deeper scholarly attention.

Actors and institutions of the legal complex are, by contrast, more likely to provide autonomous and stable sources of resilience. Because of their presence inside the state or their close connections to it, these actors can routinize a drive toward acceptance of and compliance with international human rights obligations, or at least undermine from within the state’s resolve to pursue backlash. And conversely, where such state and civil society actors are indifferent or opposed to subjecting the state to international human rights obligations, their legal expertise and authority can be weaponized to legitimate backlash.

In what follows we discuss each of the six sources of IC embeddedness and analyze the extent to which they are present across Latin America. We then use a case study of backlash to show how some of these forms of embeddedness were instrumental in bolstering the resilience of the IASyHR.

Incorporation in Domestic Law

Constitutions establish a country’s fundamental norms and institutions, so the more human rights instruments are constitutionalized, the greater the resilience of ICs is likely to be. The constitutionalization of treaties or conventions such as the ACHR limits the scope for legal debates about the authority of the institutions that make up the IASyHR and opens a path to compliance and deference. Like all law, constitutional law is a tool that actors of all types—in government, the judiciary, the legal profession, the media, and civil society—can use to steer policies in a more compliant or acquiescent direction. That is, just as human rights treaties empower domestic actors through litigation and political mobilization (Simmons Reference Simmons2009), so too can constitutions, to the extent that they provide a more robust legal basis for invoking international human rights standards and obligations. Furthermore, the constitutionalization of human rights treaties can decisively contribute to legal cultural change by spurring academic debates about the application of international law (Huneeus Reference Huneeus2016). Such reforms also make it harder for law schools to minimize the exposure of future lawyers and judges to public international law. This, in turn, makes it more likely that judges will be open to relying on ICs as a source of law and that civil society organizations will develop the capabilities for using them (and thus solidify the perceived payoff of defending ICs).

A common feature of Latin America’s new and updated constitutions has been their incorporation of international human rights treaties into domestic law (Dulitzky Reference Dulitzky, Abregú and Courtis2004, 39; Uprimny Reference Uprimny2010, 1592; Brewer-Carías Reference Brewer-Carías2009). In some cases, top courts constitutionalized international human rights treaties through their jurisprudence (Góngora Mera Reference Góngora2011, 85–136). In others, change followed more formal channels. The Peruvian constitution of 1979 and the Argentine constitution of 1994 were the first in Latin America to place international human rights norms on the same legal plane as the constitution itself (Góngora Mera Reference Góngora2011, 66). These treaties were sometimes explicitly incorporated in the constitution, including the 1994 Argentine constitution (which names the ACHR specifically and other treaties) and the 1999 Venezuelan constitution (which constitutionalized human rights treaties ratified by Venezuela) (Góngora Mera Reference Góngora2011, 69–83). A few reformers took a different approach, amending to include new interpretive guidelines designed to elevate the status of international human rights law. For example, though Article 133 of the Mexican constitution had long incorporated international instruments into the domestic legal framework, the Supreme Court usually treated this body of law as infraconstitutional. This changed in 2011 when a reform to Article 1 of the Constitution established that “Human rights norms shall be interpreted in accordance with the Constitution and the relevant international treaties, always providing people the greatest protection possible.”Footnote 7

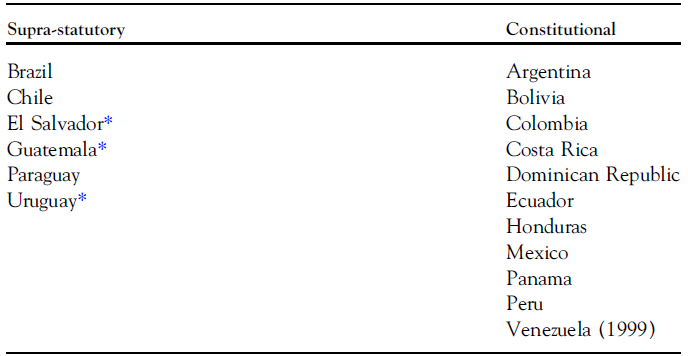

For our purposes, the key point is that the ACHR, either specifically or as a ratified human rights treaty, has been incorporated into national constitutions across Latin America. In some states, the ACHR (and other human rights treaties) has constitutional rank; in others it ranks below the constitution but prevails over statute. Table 1 summarizes the place of human rights treaties in domestic legal hierarchies.

TABLE 1. Status of human rights treaties in the domestic legal hierarchy

* Top courts in Guatemala and Uruguay view rights included in human rights treaties as constitutional rights; the Constitutional Court of El Salvador includes human rights treaties “in the parameter of constitutionality” but has not explicitly given them constitutional rank (Góngora-Mera 2011, 160).

Yet the constitutionalization of international human rights treaties does not alone produce resilient ICs, as shown in Venezuela. Under Hugo Chávez, the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (and the Venezuelan judiciary in general) was brought under the control of the government. The Chamber subsequently refused to apply international and Inter-American human rights law despite the changes introduced in the 1999 constitution. A sufficiently powerful and determined authoritarian executive can thus hollow out the institutions that are meant to embed international human rights norms. Constitutional law, in the absence of independent courts and other supportive state actors, cannot by itself ensure respect for rights.

Constitutionalization must therefore be explored together with other sources of resilience, in particular, the formal independence and informal practices of top courts. Courts can reinterpret the status of international law in the domestic legal order in the absence of formal constitutional change (and thus spark debates about the need for constitutional reform). For example, a 1992 ruling by the Argentine Supreme Court is often credited with adding momentum to the debate about the legal status of international law that culminated with the 1994 constitutional reform. In Ekmekdjian v. Sofovich (1992) the judges ruled that the ACHR takes primacy over domestic law, and that the treaty ought to be interpreted in light of Inter-American jurisprudence. And when constitutional change does take place, it is also the courts that operationalize what this means in practice. For instance, immediately after the 2011 constitutional reform, Mexico’s Supreme Court required all judges to consider IACtHR jurisprudence when deciding on cases, thus giving a clear practical meaning to the new Article 1 (Expedientes Varios 912/2010). Without judicial enforcement or internalization of the change, constitutionalization likely remains inert.

Independent Courts

International human rights instruments can be a tool in the hands of those who seek to vindicate or advance human rights domestically. But victims, advocates, and activists need courts and judges that are independent enough that they can rule against the state when the law and the facts warrant, and thus make it harder for governments to eschew their international legal obligations. Judicial independence is therefore part of the constellation of interrelated supports that can lend resilience to ICs. In this section, we assess judicial independence in the states that have accepted the IACtHR’s contentious jurisdiction.

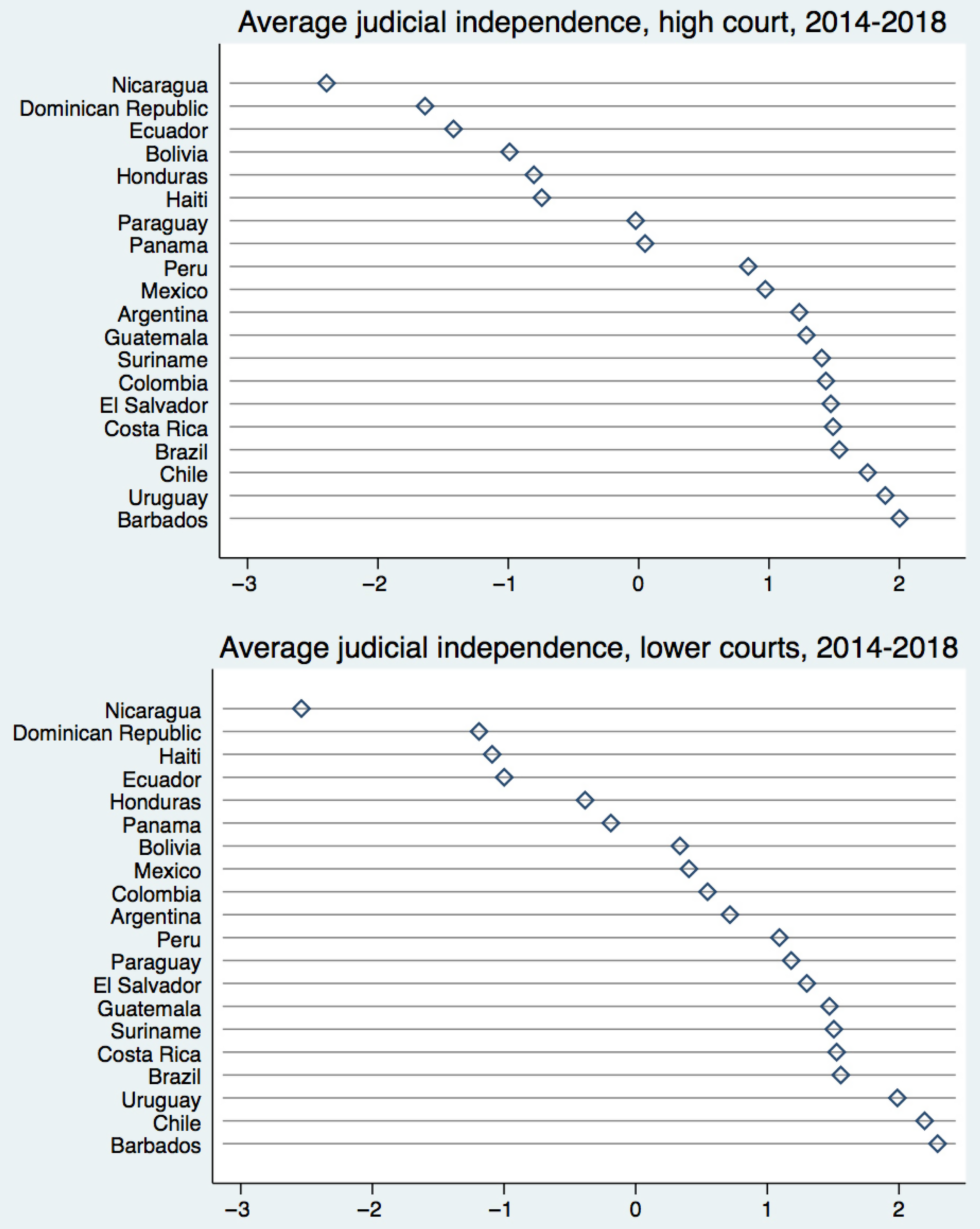

The Varieties of Democracy data project (V-Dem) includes variables for “high court independence” and “lower court independence” (Coppedge, Gerring, et al. Reference Coppedge and Gerring2019b). The indicators are designed to capture not de jure judicial independence (what the constitution says about court autonomy) but rather judicial independence in practice. The scores assigned to countries reflect assessments of the degree to which a court makes “decisions that merely reflect government wishes regardless of its sincere view of the legal record” when deciding cases “that are salient to the government” (Coppedge, Gerring, et al. Reference Coppedge and Gerring2019a, 156–57). To evaluate the level of judicial independence in IACtHR member states, we averaged scores for both high courts and lower courts for the five-year period from 2014 to 2018. Figure 1 displays the data. The “0” on the x-axis is analogous to an overall global mean. Negative numbers represent low levels of judicial independence and positive values represent high values.

FIGURE 1. Judicial independence in Latin America (2014–2018).

The figures present a mixed picture. A majority of countries (twelve out of twenty) have strongly positive scores for high court independence and fourteen out of twenty have positive scores for lower court independence. However, at each level (high court and lower courts), six states show low scores for court independence. Perhaps not coincidentally, among those states are the Dominican Republic, where the Supreme Court has thrown the country’s relationship with the IACtHR into doubt, and Bolivia and Ecuador, which led the effort in 2012 to undermine the integrity of the IASyHR (see below). It is likely that in the absence of judicial sources of resilience, the leaders of those states found it easier to mount backlash against the region’s human rights system.

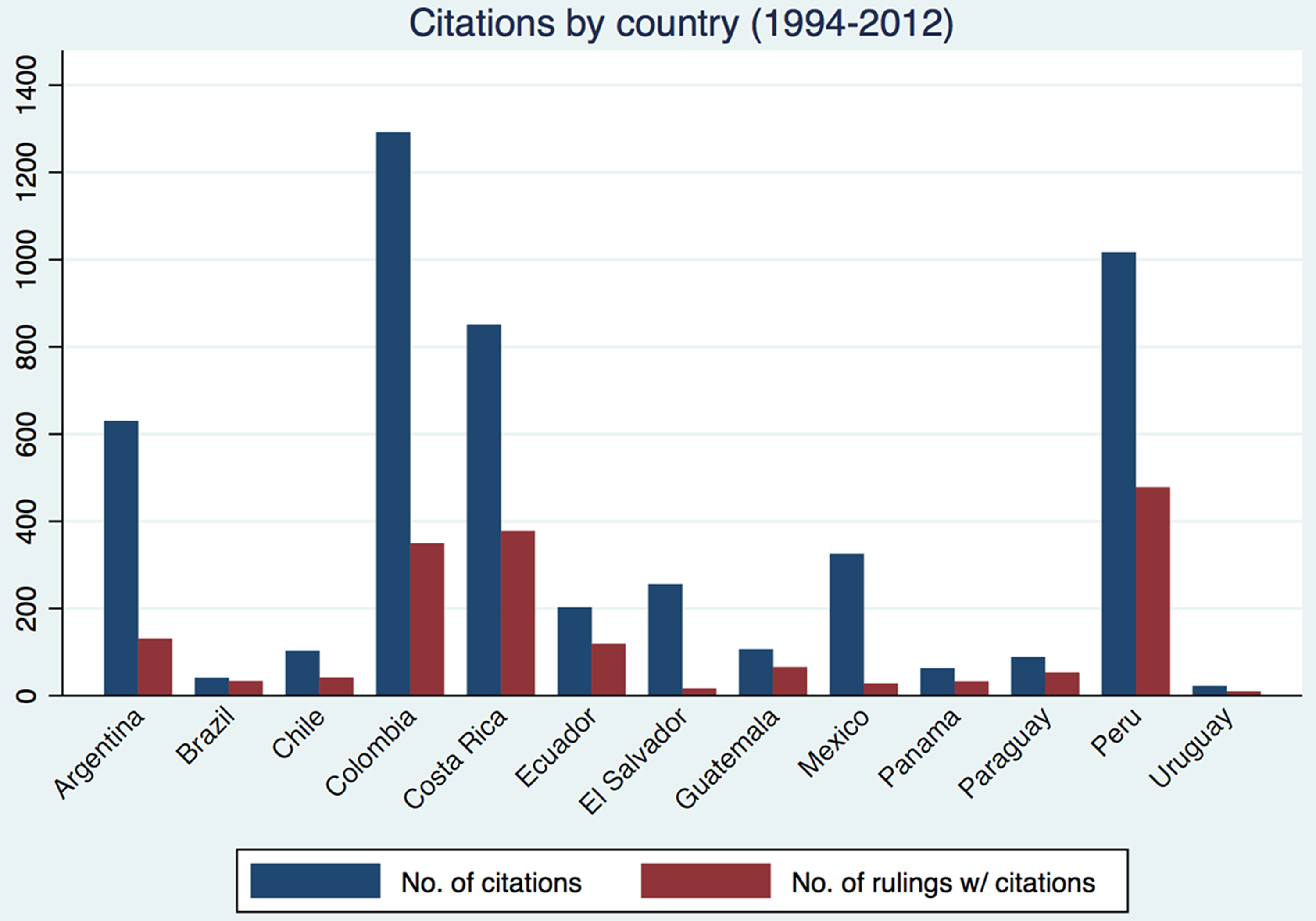

To gain a fuller picture, we also examine V-Dem data on government compliance with court decisions. Judicial independence will have limited effects if governments routinely disregard judgments (Coppedge, Gerring, et al. Reference Coppedge and Gerring2019a, 157). Figure 2 depicts the averages for 2014–2018, with x-axis values having the same interpretation as in the previous figure. Average compliance, at both levels, is higher than for the judicial independence measures, indicating that in a solid majority of states, governments generally comply with court rulings. Nicaragua, Haiti, and Ecuador show negative scores for compliance and were also among the countries with negative scores on judicial independence. Ecuador and Nicaragua both supported the 2012 attempt to weaken the Inter-American Commission.

FIGURE 2. Compliance with court rulings in Latin America (2014–2018).

In sum, regarding formal judicial independence, we see some basis for concluding that the IASyHR maintains respectable levels of embeddedness. One important caveat, however, is that courts can be formally independent and enjoy high compliance rates, but still reject the authority of Inter-American institutions or remain unaware of the standards set by them. We must therefore look beyond formal independence to assess the actual judicial practices and philosophies that shape the behavior of judges when it comes to rights enforcement and the IASyHR.

Reception of International Jurisprudence

Even highly independent domestic judiciaries can only be relied upon as a source of resilience when they accept the legal authority of IC jurisprudence and make use of it (Alter Reference Alter2001; Slaughter Reference Slaughter2003). The direct, voluntary, and routine application of international human rights standards by local courts not only enhances the prestige and effectiveness of ICs, but also adds a layer of democratic legitimacy to what might be seen as “foreign” standards. This can serve as a powerful counterargument to those wishing to marshal nationalist rhetoric to orchestrate backlash. Coming to accept the legal authority of an IC is not just a function of formal institutional change; it is also a function of arduous transformations in informal judicial practices and legal preferences.

Although Latin American high courts have become globally recognized for their innovative jurisprudence on fundamental rights, this progressive reorientation is a relatively new phenomenon. Until the 1990s, judicial branches were home to a formalistic version of legal positivism (Hilbink Reference Hilbink2007), which engendered “a deferential understanding of the role of the courts” (Couso Reference Couso, Couso, Huneeus and Sieder2010, 152) and hostility toward nontextualist readings and nonstatutory sources of law. This positivist “habitus” thus stifled the development of creative, rights-oriented, constitutional jurisprudence (López-Medina Reference Lopez-Medina2004). International human rights law did not do well in this environment, and it was largely absent from courts’ opinion-writing toolkits. Relying on international human rights law to interpret statutes or the constitution often implies a departure from plain-meaning interpretation, which itself requires familiarity with quite complex hermeneutic techniques that were generally alien to Latin America’s highly formalistic judges (Cepeda Reference Cepeda2006).

This started to change in the 1990s with the inflow of “neo-constitutionalist” ideas (Nolte and Schilling-Vacaflor Reference Nolte, Almut, Nolte and Schilling-Vacaflor2012). Debates over constitutional reforms in Costa Rica (1989), Colombia (1991), and Argentina (1994) favored the incorporation of international legal ideas into domestic law. The reforms not only gave voice to progressive sectors of the legal complex that until then had been marginalized (Huneeus Reference Huneeus2016), but also led to the appointment of judges committed to neoconstitutionalism (Nunes Reference Nunes2010; Couso and Hilbink Reference Couso, Lisa, Helmke and Ríos-Figueroa2011; Brinks and Blass Reference Brinks and Abbey2018). Civil society was also an important force of change in judicial decision making, introducing new adjudication frameworks via strategic litigation (Gonzalez-Ocantos Reference Gonzalez-Ocantos2016). The judicial field thus became a more hospitable site for the development of resilience capabilities.

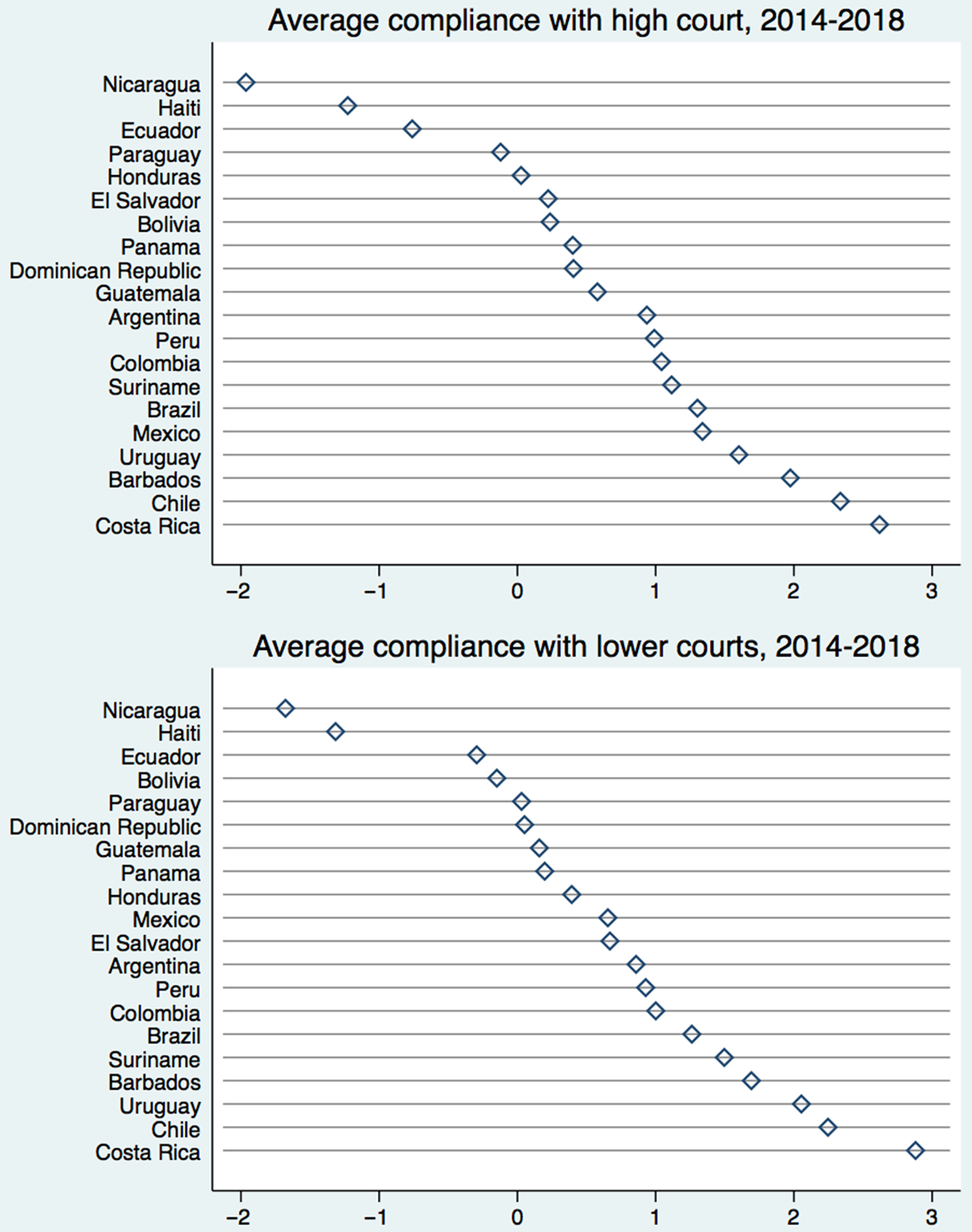

During this period, high courts began to recognize the authority of the IASyHR. Between 1994 and 2012, we found that thirteen high courts in the region cited the IACtHR 4,999 times in 1,736 rulings.Footnote 8 High court judges cite a broad array of Inter-American precedents, including those that do not generate direct international responsibilities for their own country (only 21 percent of all citations refer to cases in which the citing court’s country is a party). To be sure, considering that most of the courts in our sample issue hundreds of thousands of rulings every year, references to the IACtHR’s jurisprudence were relatively rare during this period. Moreover, there is huge cross-country variation in levels of receptivity and familiarity with Inter-American case law (Figure 3). Notably, countries with a more robust constitutionalization of international human rights law—Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Peru—feature more citations. This indicates that formal institutional change may induce more far-reaching changes in informal interpretative practices, turning high courts in these countries into more reliable sources of resilience.

FIGURE 3. Citations to IACtHR case law by country (1994–2012).

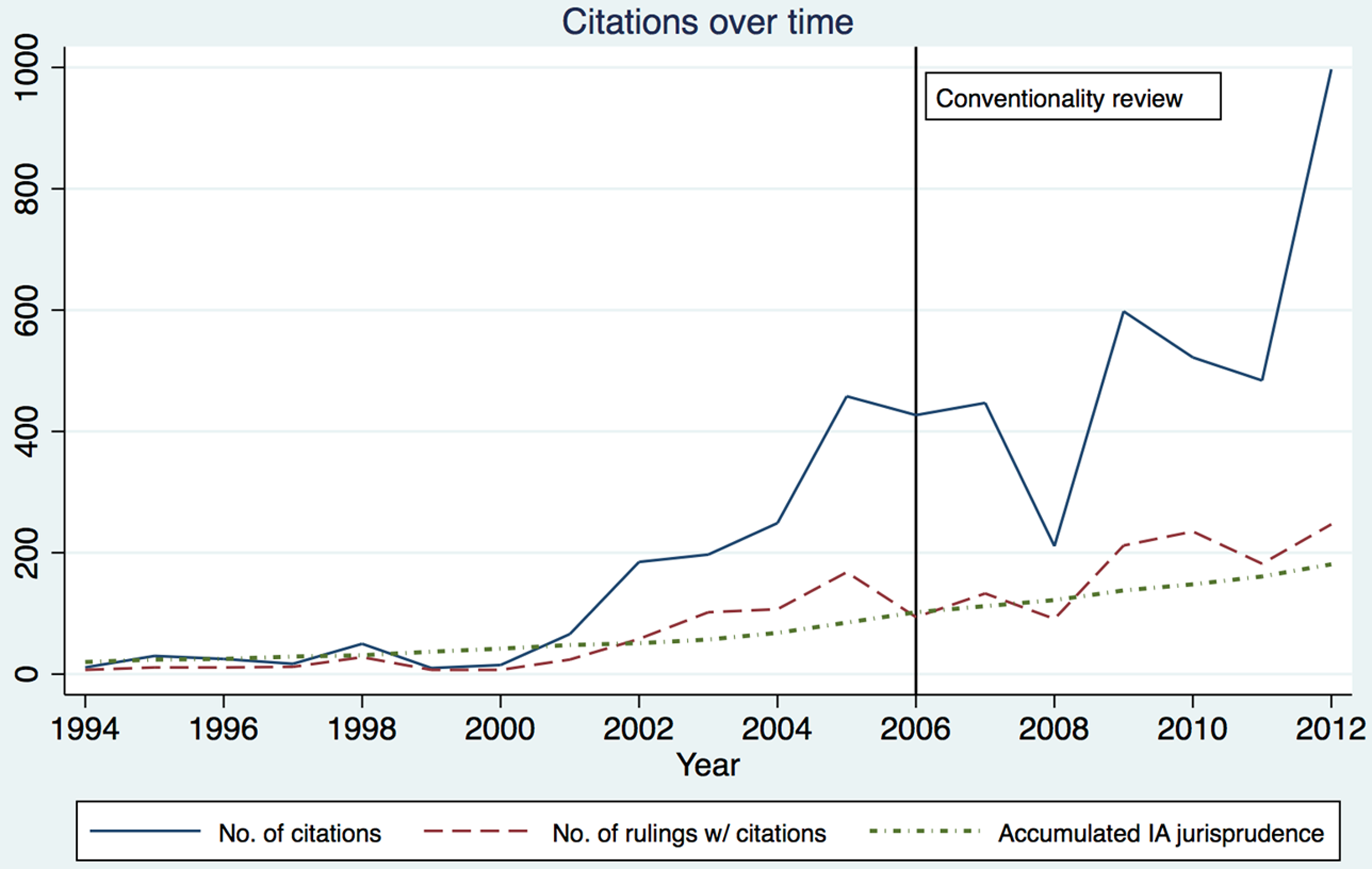

Overall, however, the regional trend is clear, with all courts in the sample paying more attention now than before to human rights standards that emanate from the IASyHR. Figure 4 shows that while citations were extremely rare in the 1990s, they became increasingly common after the turn of the century. The trend accelerated toward the end of the series, especially after the IACtHR developed the “conventionality review” doctrine, precisely with the goal to trigger this kind of transnational judicial dialogue, and thus turn local courts into allies in the enforcement of human rights standards (Gonzalez-Ocantos Reference Gonzalez-Ocantos2018).

FIGURE 4. Citations to IACtHR over time (1994–2012).

Growing recognition of Inter-American case law as a legitimate source of law solidifies countries’ relationship with the IASyHR, and can be a valuable source of resilience in the presence of backlash. More generally, to the extent that high courts establish a symbiotic relationship between constitutional and international law, they make it procedurally harder to engineer backlash, as this might then require costly constitutional bargains. Moreover, high courts that base high-stakes jurisprudence in Inter-American case law are likely to see backlash against the IASyHR as an affront to their institutional identity, and therefore engage in efforts to resist such moves. Finally, courts that are well-versed in Inter-American case law, and willing to engage with Inter-American institutions, are better positioned to translate and operationalize the international legal responsibilities created by the Court and Commission. Translation is important because it helps adjust abstract human rights standards to local conditions, rendering compliance more viable, and signals domestic ownership of otherwise foreign standards, thus adding a layer of legitimacy to international law. These dynamics in turn help reduce the chances of observing backlash against, or mere lip service to, Inter-American human rights institutions.

National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs)

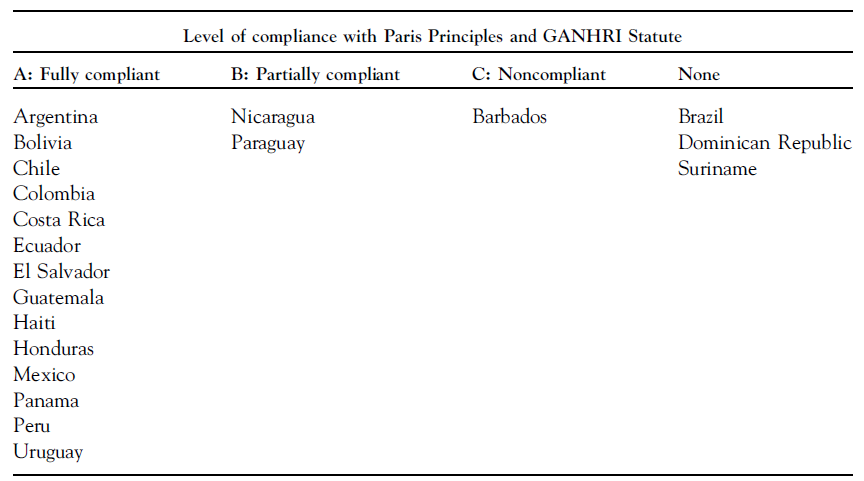

Even if domestic law and courts provide means for people to vindicate rights and defend ICs, support for international human rights institutions will be greater to the extent that other state institutions also promote rights. We focus here on NHRIs (Linos and Pegram 2017). The Paris Principles (UN standards for the establishment and functioning of NHRIs) declare that NHRIs are to be official bodies that operate independently of the government. They can hear complaints of rights violations, promote education about rights, and recommend legal reforms, among other functions. The Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI) accredits national institutions based on their level of compliance with the Paris Principles. We make use of the GANHRI accreditation status ratings to assess the state of NHRIs in IACtHR member states. Table 2 presents the classifications as of November 2019.Footnote 9

TABLE 2. Accreditation status of National Human Rights Institutions

Source: GANHRI 2021

A strong majority of states are deemed “fully compliant” with the Paris Principles. Four countries currently do not have NHRIs that are members of the GANHRI and therefore have no accreditation status. Though the ratings may not reveal much about how active and effective the institutions are in practice, most countries have created NHRIs that, at least formally, meet global standards. NHRIs can establish linkages between governments and CSOs, and between domestic legal institutions and regional human rights systems (Smith Reference Smith2006). Latin American NHRIs do this in various ways: submitting petitions to the Commission on behalf of claimants; submitting amicus briefs and serving as expert witnesses at the IACtHR; tracking cases in process in the IASyHR; monitoring national compliance with IASyHR provisional measures and remedies; and reporting on national compliance to the IACtHR (Pegram Reference Pegram, Goodman and Pegram2012; Pegram and Herrera Rodríguez Reference Pegram, Nataly, Engstrom and Molyneux2019).Footnote 10 NHRIs are thus a site of embeddedness because their actions can preempt behavior or policies that might put states on a collision course with the IASyHR.

Legal Academy and Training

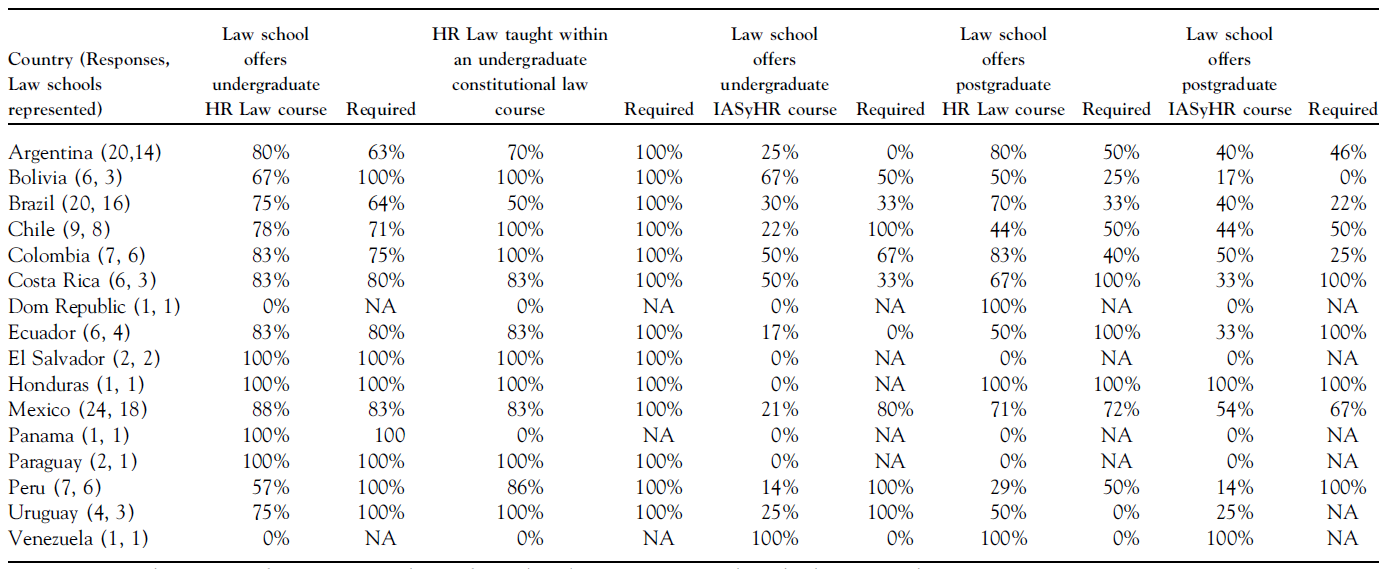

Human rights law, having been integrated into constitutional law across most of Latin America, has been incorporated into legal education as well. In an online survey of law professors from across the region,Footnote 11 we found that a majority of respondents in most countries reported that their institutions offer human rights law as a stand-alone undergraduate course or as part of standard constitutional law courses (fewer offer a course specifically on the IASyHR or teach these subjects at the postgraduate level, see Table 3). Venezuela and the Dominican Republic, countries that have been the site of recent backlash efforts, are the exception. Interestingly, we found that most institutions that offer a course on human rights law, started to do so from the mid-1990s onward, possibly reflecting the wave of constitutional change and accompanying the trend toward greater embeddedness in other dimensions.Footnote 12

TABLE 3. Human Rights and the IASyHR in Latin American Law Curricula

Source: Authors’ survey of Latin American law professors (2021). 117 responses, 88 law schools represented.

Incorporation of the IASyHR and the jurisprudence of the IACtHR in law school curricula in Latin America has advanced the “Inter-Americanization” of legal cultures in the region (Morales Antoniazzi and Saavedra Alessandri 2017, 267), diffusing knowledge and acceptance of Inter-American legal standards among future lawyers, clerks, and judges. In this sense, some studies show that young clerks trained in international human rights law play an instrumental role in changing judicial decision-making cultures in top courts (Cortez Reference Cortez2020).

In addition, a number of law schools in Latin America have recently established legal clinics, furthering the embeddedness of the IASyHR in the academy. Their work offers law students a form of practical, experiential learning about the law and procedures of the IASyHR. Moreover, clinics promote litigation and thus are an integral part of the IASyHR’s support structure (Epp 1998). Crucially, the professors and students who take part in these initiatives are in a privileged position to respond to backlash both within their own states and internationally, filing briefs and orchestrating public campaigns of support for ICs.

The first law school clinic with a focus on human rights appears to be the Clínica de Acciones de Interés Público y Derechos Humanos at Universidad Diego Portales (UDP) in Santiago, Chile. The clinic was created in the 1990s and operates under the umbrella of the Centro de Derechos Humanos.Footnote 13 The purpose of the clinic is to train students and future lawyers in the skills needed in the area of human rights. Students work on actual cases, preparing strategies and documents and submitting them at the relevant courts, under the supervision of clinic attorneys. The clinic has supported cases in the IASyHR. For example, it was one of the petitioners’ representatives in the submission to the IACmHR in Atalo Riffo and Daughters v. Chile.

Similar clinics with activity in the IASyHR have been established at the Universidad del Rosario in Bogotá, Footnote 14 the University of Santiago (Cali),Footnote 15 the University of Buenos Aires,Footnote 16 the University of Palermo (Buenos Aires), the University of San Francisco (Quito), and the Autonomous National University of Mexico.Footnote 17 At a transnational level, the Latin American Legal Clinic Network is an association of law school clinics dedicated to practical, public interest legal training. Created through an initiative of Diego Portales University, the Network includes universities from Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru. Its stated objective is to strengthen clinical instruction and participate in “the defense of the public interest and of human rights through strategic litigation.”Footnote 18

In light of the different ways in which the academy can serve as a national and transnational site of embeddedness, it is not surprising that the institutions of the IASyHR take their relationship with universities seriously. For example, when the IACtHR holds in-country hearings, it makes sure the sessions are open to the public, mainly law students. Inter-American judges also meet with prominent academics and participate in roundtables or seminars. These meetings help solidify institutional links, and often result in formal cooperation agreements that create knowledge-exchange initiatives. According to the Court’s annual reports, it has signed at least forty-nine cooperation agreements with universities from twelve Latin American countries.

Civil Society

A final form of embeddedness is found in civil society organizations (CSOs) that engage with the IACmHR and IACtHR, and push for compliance with their judgments. The ultimate subjects—and intended beneficiaries—of Inter-American human rights law and jurisprudence are the region’s people. International law exerts its most potent effects when it empowers those who suffer violations to vindicate their rights through legal and political mobilization (Simmons Reference Simmons2009). But most of the citizens who live under the umbrella of the IASyHR are probably not aware that it exists, that it defines rights and freedoms to which they are entitled, and that states are obligated to ensure those rights are realized. Many also lack the knowledge and resources to pursue legal remedies for rights violations or force the state to acquiesce to its international obligations.

CSOs help fill the knowledge and resource gaps that inhibit access to national courts but, even more so, to the IASyHR. They educate people about their rights, inform them about where to seek recourse, advise them as they seek access to justice, assist them in preparing and filing the necessary documents, and represent them in judicial proceedings. CSOs that know and work within the IASyHR are also likely to be a crucial source of support for the Commission and the Court. They often work at the level of national institutions, advancing litigation in domestic courts and pressuring governments to meet their constitutional and human rights treaty obligations. Moreover, like human rights clinics, CSOs are key stakeholders, and therefore have a vested interest in defending the system whenever backlash materializes. As a result, it is fair to assume that the stronger the presence of CSOs that work with the IASyHR across the region, and the stronger the transnational ties between them, the greater the resilience of the IASyHR.

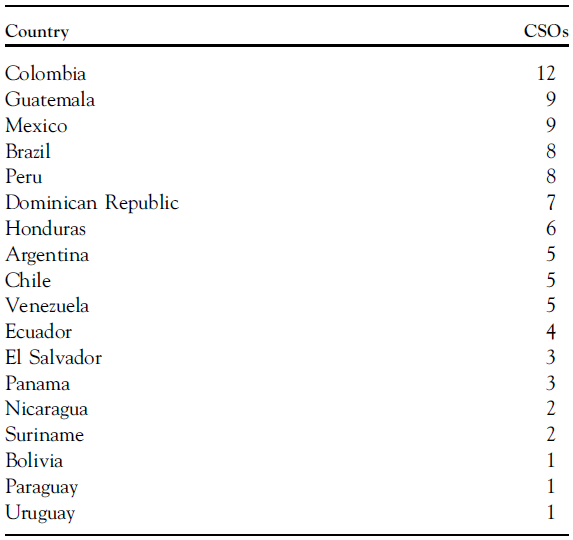

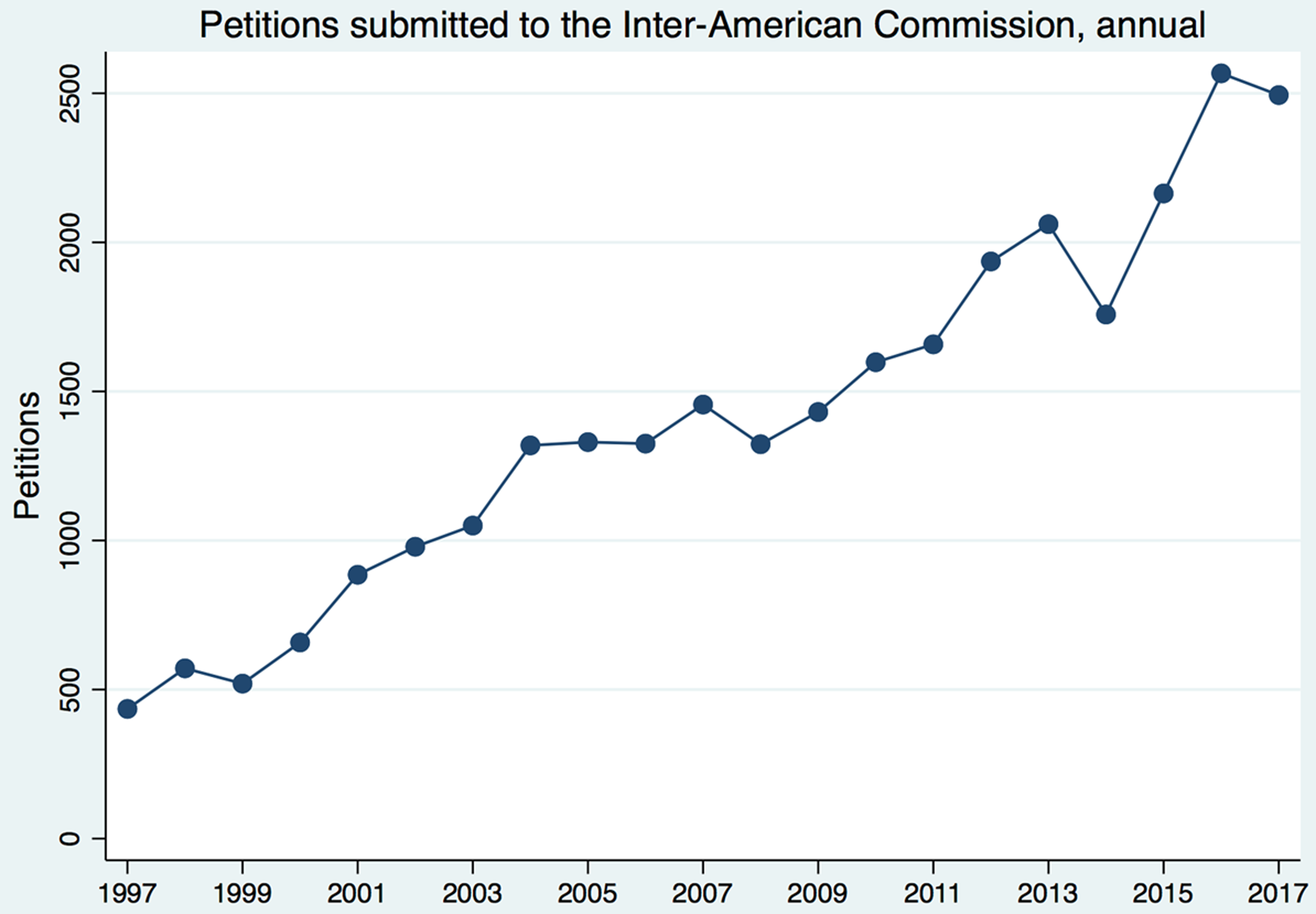

Because CSOs operate at so many levels and in diverse arenas, it would be impossible to evaluate comprehensively the degree to which they build connections between publics and the IASyHR. We focus on one important means of observing the degree to which CSOs serve that function: the representation of petitioners. By examining briefs submitted to the IACtHR, we constructed a list of CSOs that have served as representatives of petitioners. We included briefs filed in relation to judgments on the merits at the IACtHR in the last ten years (2010 or later).Footnote 19 Our review almost certainly understates the extent of CSO participation in litigation. Only a small fraction of petitions submitted to the Commission end in judgments issued by the IACtHR. For instance, in 2017, the Commission received about 2,500 petitions and the Court handed down ten judgments on the merits. A systematic view of the petitions submitted to the Commission, however, is impossible because they are generally not available on the Commission’s website. Our data include all CSOs listed as petitioners’ representatives on petitions submitted to the Commission or briefs filed at the Court, in cases that produced a judgment on the merits at the IACtHR. A far larger number of CSOs have almost certainly participated in petitioners’ briefs at the Commission.

We identified eighty-eight different CSOs that represented petitioners either at the Commission or the Court (or both) in 119 cases that reached a judgment on the merits since 2009. The cases came from twenty different countries, including Venezuela. That count excludes organizations that are not based in the region or are not civil society based. For instance, a few human rights clinics from North American law schools appear in the overall list but are not counted among the region’s CSOs. We did not count state agencies, like Argentina’s Ministerio Público de la Defensa or Bolivia’s Ombudsman, which appear on the briefs. We also left out the Asociación Interamericana de Defensorías Públicas, which has represented a number of petitioners, because it is an organization of state public defenders. We did include the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL) which, though headquartered in Washington, DC, has offices in Buenos Aires, Río de Janeiro, and San José. CEJIL represented petitioners in thirty-three of our 119 cases. The next most frequently participating CSOs were the Comisión Ecuménica de Derechos Humanos, based in Ecuador, with six, and Peru’s Asociación Pro Derechos Humanos, with five.

The CSOs in our data are not spread evenly across countries. Table 4 shows the number of CSOs appearing on briefs in cases from each state. With few exceptions, the CSOs counted here appear to be based in the countries listed. Countries at the top of the list are relatively dense with IACtHR-active local organizations. Some countries (Haiti, Paraguay, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Bolivia, Uruguay) have few. To be sure, these numbers do not take into account characteristics of the countries, like their population, how often they are subjects of Commission petitions and IACtHR judgments, or the general vibrancy of civil society. In other words, we do not mean to imply anything about whether a country total is high or low, given its domestic context. The point is that nearly all of the countries have at least some CSOs that connect people to IASyHR, and many have quite a few.

TABLE 4. CSOs per country

The picture with respect to CSOs that work with the IASyHR should be considered in light of the rising rate of petitions submitted to the IACmHR. CSOs can be a greater source of support to the extent that the demand for their assistance and services is increasing. Where more victims seek to access the system, CSOs can exert a more powerful effect. In fact, the number of petitions filed at the Commission has risen dramatically over the past two decades, as shown in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5. Petitions submitted to the IACmHR, by year.

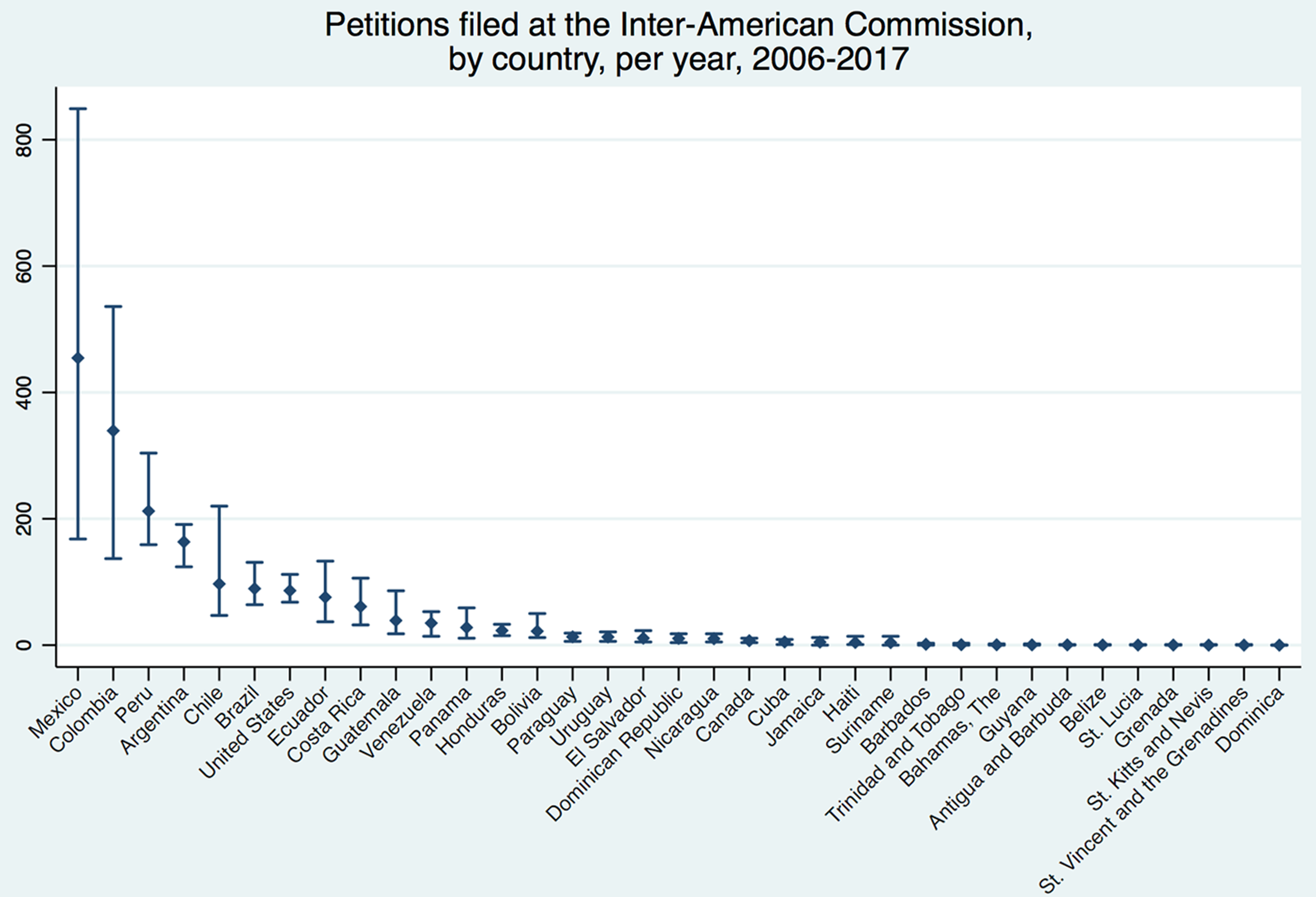

Not surprisingly, the rate of submission varies across countries and over time. Figure 6 displays petitions filed at the Commission by their country of origin over the period 2006–2017. The top stem indicates the largest number of petitions for a given country in any year and the bottom stem denotes the smallest number of petitions in any year. The diamonds represent the average for 2006–2017. A pair of facts stands out. First, fewer than half of the countries are responsible for the vast majority of petitions. Citizens of Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Argentina, and Chile have submitted over one hundred petitions per year on average, with Mexico the source of more than four hundred per year on average. Second, the countries whose citizens have submitted the largest number of petitions are also among the countries with the largest number of CSOs that have participated in IASyHR proceedings (compare Table 3).

FIGURE 6. Petitions submitted to the IACmHR, by country.

Despite wide cross-country variation in the engagement of CSOs with the IASyHR, it is fair to say that the system counts on a solid CSO support structure with a foot in most countries. While often critical of the system, these are also the actors with the greatest vested interest in preserving and defending it from backlash. In fact, as we shall see in the case study below, CSOs were the main protagonists of the resistance movement that successfully defended the integrity of Inter-American human rights institutions when several member states launched a sustained attack on the system between 2011 and 2014.

A CASE STUDY OF BACKLASH AND RESILIENCE

In this section we offer a case study of backlash against the IASyHR during the early 2010s, when some states sought to undermine the independence and power of the IACmHR, a move that could have eroded the functionality of the entire system. Yet they failed, and the IASyHR survived.Footnote 20 The states that spearheaded the backlash—Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela—were each the subject of IACtHR and IACmHR decisions that challenged key domestic policies. If embeddedness indeed played a part in neutralizing or diminishing the virulence of their attack, we should observe a number of things in response to the challenge. At the very minimum, we should observe CSOs and academics mobilize in support of the system, contributing to the international debate via briefs, press releases, and so on. Even stronger evidence would come from instances in which lobbying by these actors correlates with changes in states’ support for backlash, or a decline in their indifference vis-à-vis the behavior of hostile states. Furthermore, we should see forms of embeddedness such as the constitutionalization of the ACHR or domestic jurisprudence receptive of Inter-American case law, shaping or constraining the way states respond to backlash.

In what follows, we explain why this backlash effort failed. A resistance movement led by national and international CSOs, as well as some governments, was activated thanks to the presence of the forms of embeddedness discussed above. Our case study also underscores that individual forms of embeddedness do not operate independently but benefit from interactions and synergies with others.

Origins of the Backlash

During the July 2011 General Assembly of the OAS, states voted to create a Special Working Group (SWG) to discuss the work of the IACmHR with the stated goal of “strengthening” the IASyHR.Footnote 21 The decision to put the IACmHR under review was taken against the backdrop of a row between the Brazilian government and the Commission. Earlier that year, the Commission had issued a precautionary measure ordering Brazil to suspend the construction of a dam in the Amazon region on the grounds that the project could produce irreparable damage to the livelihoods of indigenous communities. This was by far the most important infrastructure initiative of Dilma Rousseff’s administration. When finished, the dam would become the world’s third largest source of hydroelectric power (Cassell Reference Cassell2014). In retaliation, Brazil recalled its OAS ambassador, removed its candidate for a seat in the IACmHR, and withheld payment of its annual contribution. Brazil subsequently launched a diplomatic offensive to make sure the SWG reviewed the use of precautionary measures, one of the most important tools at the Commission’s disposal to protect human rights.Footnote 22

Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, which were members of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA), seized upon Brazil’s position to express long-held grievances against the IASyHR, and fully supported the creation of a SWG. During the 2000s, both the IACmHR and the IACtHR had trained their eyes on these countries, denouncing illiberal practices and threats to democratic stability. For the Bolivarian nations, the various rulings and reports issued by these two institutions constituted unacceptable intrusions into their internal affairs.Footnote 23 The IASyHR was simply, in their view, another tool of US imperialism. During the second half of 2011, they intervened in the debates of the SWG to voice a series of demands.Footnote 24 First, diplomats from all three countries repudiated the system’s lack of universalism, pointing out that neither the US nor Canada had ever ratified the ACHR. Second, Venezuela took the lead in attacking the Commission’s reporting practices. In Chapter 4 of its annual report, the IACmHR usually singles out those countries where it observes the most egregious human rights violations. Venezuela was keen to promote changes in the reporting “methodology,” for example, arguing that the Commission should discuss the human rights situation in all member states rather than in a few carefully selected targets. At times it even implied that the practice should be discontinued. Third, toward the end of 2011, Ecuador proposed a series of reforms to the Commission’s system of special rapporteurs. This is because the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression, by far the better funded and most active in the IASyHR, had previously irritated the Correa administration (see below). Ecuador wanted the Commission to distribute financial resources equally among special rapporteurs and ban the practice of earmarked contributions by states and donors so that no special rapporteur received a disproportionate share of the funds.

The SWG presented the conclusions of this initial period of debate in December 2011.Footnote 25 While it recommended an increase in the annual financial contributions of member states, most recommendations were addressed to the Commission. For example, it encouraged the IACmHR to establish clearer, more objective criteria to determine which situations merit the use of precautionary measures, and work closely with states to monitor the need for maintaining existing ones. The more extreme recommendations, including those put forward by Venezuela and Ecuador, however, did not gain momentum. In the January 2012 meeting of the OAS Permanent Council, during which member states debated the conclusions of the SWG, there was support for the work of the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression. It was also made clear that none of the recommendations should be interpreted as a mandate; the Commission had independence to decide what to do about them. Ecuador even ceased its call for the creation of a mechanism to monitor the implementation of the recommendations (Amato Reference Amato2012).

The Initial Response to Backlash

It is highly likely that behind-the-scenes diplomatic efforts by supportive member states helped lower the tone of the recommendations (see below for a discussion of the role of Uruguay and Mexico). Furthermore, the IACmHR was quick to appease the Brazilian government: in July 2011, the same month the General Assembly created the SWG, the Commission softened the reach of the precautionary measure that triggered backlash. Brazil may have therefore estimated that it did not need a full-blown attack to keep commissioners on a leash. But in addition to realpolitik, the presence of various forms of embeddedness enabled the activation of resilience mechanisms, most notably, via the intervention of CSOs from across the continent.

According to CELS, a leading Argentine human rights NGO, the initial debate “was centralized in Washington, DC, and took place in a less than open way. The discussions did not allow for widespread participation and monitoring by the organizations that use the IASHR or victims” (CELS 2013, 453). CELS nevertheless developed a strategy to influence the discussions in coordination with other CSOs from across the region: “The strategy involved the production of documents, periodic meetings by each intervening organization with the foreign ministries of their respective countries, and meetings with members of the IACmHR, the diplomatic missions of the member states and the General Secretary of the OAS” (ibid., 453–54, ft. 34).Footnote 26 CSOs were especially vocal toward the end of this initial debate, defending the IACmHR against some of the most radical recommendations, including those tabled by Ecuador.Footnote 27 It is hard to establish the extent to which these early interventions really mattered for the outcome; the evidence is simply suggestive. But as we shall see later on, when backlash escalated between 2012 and 2014, these same organizations, most notably CELS from Argentina and Conectas Direitos Humanos from Brazil, played a crucial role in deactivating the revolt against the Commission.

While the authority of the IACmHR was not ultimately compromised, the pressure exerted by member states between July 2011 and January 2012 was unprecedented. The usual Bolivarian critics of the system were joined by more powerful, fully democratic states like Brazil, thus opening up an unusually wide window of opportunity for undermining the integrity of Inter-American human rights institutions. Given the tone of the grievances voiced during these discussions, the timid recommendations of the SWG could still easily morph into more existential threats. Would member states respect the Commission’s autonomy to consider the recommendations, or would they try to impose the changes? Would member states create parallel human rights institutions via other regional organizations to undermine the authority of the IASyHR? Would some countries abandon the IASyHR or stop funding it?

The Bolivarian states subsequently launched some of these threats and prolonged the discussion. They failed, however, because the allies they needed to succeed, especially Argentina and Brazil, did not in the end support these calls for more severe backlash. The activation of domestic resilience mechanisms in Argentina and Brazil partly explains why this was the case. At the time, Argentina and Brazil were governed by left-of-center administrations sympathetic to the Bolivarian cause. Their support for backlash, or even their acquiescent silence, could have sealed the fate of the IASyHR. The anti-US, anti-imperialist rhetoric of Chavez, Correa, and Morales certainly appealed to presidents Kirchner of Argentina and Rousseff of Brazil.Footnote 28 But the political equation was not so straightforward. Dismantling a regional human rights regime was certainly not fitting for a country with global leadership ambitions like Brazil. In the case of Argentina, doing so would be at odds with its identity as a leader in the development of human rights norms (Sikkink Reference Sikkink2008). In this sense, it is worth remembering that the Kirchner administration took special pride in its policy of widespread human rights prosecutions (Roehrig 2009). This process was in part made possible by the work of both the IACmHR and the IACtHR. For example, the IACmHR’s 1979 in loco inspection of the human rights situation in Argentina during the dictatorship is often mentioned as a milestone in the country’s trajectory from “pariah to global protagonist” in the field of transitional justice (Sikkink Reference Sikkink2008, 5). Similarly, the IACtHR’s jurisprudence on amnesty laws played a key role in allowing the Argentine Supreme Court to declare the unconstitutionality of amnesty laws in 2005, and thus catalyze the aforementioned wave of criminal prosecutions. These factors were key when it came to activating resilience mechanisms, and helped veer the position of both countries to one of open support for the autonomy of the Commission.

Intensification of the Backlash

After the meeting of the Permanent Council in January 2012, the Commissioners had to decide how to respond to the “recommendations” of the SWG. In February, the Commission issued another precautionary measure, this time against Ecuador.Footnote 29 The Ecuadorian judiciary had ruled in favor of President Correa in a libel suit against a leading newspaper and imposed a fine of US $40 million. For the Commission, these developments put freedom of speech in jeopardy. The Commission’s intervention had Correa fuming, and he and his Bolivarian allies took advantage of the June OAS General Assembly in Bolivia to launch a full-frontal attack. As Rivera-Juaristi (Reference Rivera-Juaristi2013, 1) describes, “in his opening speech at that General Assembly, Bolivian President Evo Morales said that the OAS had two options: “it either dies as a servant of the [US] empire or revives to serve all of the nations of the Americas.” The Bolivarian nations thus managed to put the reform of the IASyHR back on the agenda. In fact, the General Assembly instructed the Permanent Council to come up with a series of reform proposals and called for a special meeting of the General Assembly in 2013 to evaluate the plan.Footnote 30

Furthermore, in subsequent months, Correa and his allies used other regional venues such as CELAC and UNASUR to propose the creation of human rights institutions outside of the “imperialist” orbit of the OAS. While these proposals did not gain traction, in November 2012 UNASUR member states, “with the exception of Venezuela, approved a proposal to request the OAS Secretary General to convoke a meeting of the 25 States Parties to the American Convention [which does not include the US] to be held prior to the upcoming March 2013 OAS Special General Assembly, with the purpose of discussing reforms to the Inter-American System” (ibid., 2). Venezuela did not support this move because it had formally removed itself from the jurisdiction of the IACtHR in September and continued to insist on more radical alternatives outside the OAS framework.

Resilience

The months following the June meeting of the General Assembly saw the activation of resilience mechanisms throughout the region, which ultimately helped isolate the Bolivarian nations and protect the IASyHR. The Commission made sure the debate became much more public than in the initial period and that it took place across the region, rather than within the narrow confines of the OAS in Washington, DC. This served to legitimize its response to the recommendations of the SWG, and crucially, to build a social support shield. According to the President of the IACmHR, the processes included: “98 position documents, with the points of view of more than one thousand organizations, individuals, academic institutions, and other non-governmental entities; a hemispheric seminar; five regional fora (Bogota, Santiago, San Jose, Mexico and Puerto España), with the participation of more than 150 speakers from civil society and representatives of 32 states; three hemispheric public hearings at the Commission, with the participation of OAS member states and more than 70 civil society organizations; briefs by the Inter-American Juridical Committee and the Inter-American Institute of Human Rights; … [and] two public hemispheric consultations” (Orozco Reference Orozco2014, 4). The Permanent Council also created mechanisms for civil society participation. Argentina’s CELS and other organizations devised strategies to take advantage of these multiple fora and submitted briefs throughout (CELS 2013, 456–57).Footnote 31

Forms of embeddedness at the level of individual member states also played a role. Several countries had a long history of commitment to the IASyHR and provided unwavering support for the Commission. For example, the Uruguayan government made clear its support for “all those recommendations that do not limit the autonomy and independence of the IACmHR and the IASyHR. The autonomy and independence of the IACmHR is an essential factor to maintain its credibility, legitimacy, and functionality.”Footnote 32 Mexican support for the system was also strong and consistent throughout.Footnote 33 For instance, observers recognize the contribution of Mexican Ambassador to the OAS Joel Hernandez who served as president of the SWG: he “performed an excellent job as mediator and consensus builder” (Amato Reference Amato2012, 4; Cassell Reference Cassell2014, 23). Mexico’s position can be partly attributed to a greater degree of embeddedness achieved immediately prior to backlash. Indeed, its new active role in the IASyHR coincided with the 2011 constitutional reform that elevated the legal status of international human rights treaties and enshrined the pro homine principle as a pillar of the country’s constitutionalism. Shortly after, the Supreme Court deepened the country’s Copernican legal revolution when, in Expedientes Varios 912/2010, it accepted the IACtHR’s conventionality review doctrine. Given these changes, it would have been odd for Mexico to adopt a supportive or indifferent position vis-à-vis backlash.

Although by early 2012 Brazil had abandoned its openly antagonistic position, its failure to provide explicit support for the Commission emboldened the Bolivarians. This sounded alarm bells among Brazilian NGOs. At the start of the reform process in 2011, Conectas Direitos Humanos, one of the leading NGOs in the country, made use of a new freedom of information act to ask the government to publish all telegrams sent between the Foreign Ministry and Brazil’s OAS diplomatic mission. The goal was to pressure the government to adopt a public stance against backlash. According to Conectas officials, while the ministry denied the request, the move

was important to open a channel of communication between the Foreign Ministry and Brazilian organizations around the positions adopted by the state during the reform process. In the initial response to the request, the Foreign Ministry proposed a meeting with civil society to clarify Brazil’s position. … These meetings helped demand that Brazil made its positions public and that it previously discussed them with civil society. As part of this process, Brazil later on pronounced itself: 1) in favor of the autonomy and independence of the IACmHR; 2) in favor of keeping Chapter IV of the IACmHR’s annual report; and 3) to reject a reform of [the Commission’s internal] guidelines carried out by the states and also to reject a reform of the Statute (Kweitel and Cetra Reference Kweitel and Raisa2014, 50).

In other words, at least according to this account, domestic forms of embeddedness contributed to a change in Brazil’s public position and to the open repudiation of the most radical reforms promoted by Bolivarian nations.Footnote 34

A similar process took place in Argentina. During the SWG debates in 2011, Argentina did not support the most radical reform initiatives. But like Brazil, it did not openly oppose them either. Moreover, in the debate that took place after the June 2012 General Assembly, Argentina persisted in objecting to the Commission’s use of precautionary measures. In response, CELS intensified its already regular exchanges with the Foreign Ministry:

[I]n addition to the regional work, from the start of the discussions in 2011, CELS sought a periodic dialogue with the [Foreign Minister], as well as with ministry staff following the debates. At different moments during the process, [CELS] sent formal letters and working papers, and held meetings. At the same time, [CELS] made a series of public interventions [in the Argentine press] (CELS 2013, 459, ft. 56).

In a November 2012 brief, the Argentine government changed the tone of its public position. Like Brazil, it now explicitly stated the importance of protecting the autonomy and independence of the Commission, and among other constructive proposals, it suggested a system of compulsory financial contributions to the IASyHR. The following passage from the brief is worth quoting at length:

The Argentine state’s policy of cooperation with the institutions of the [Inter-American] system … has had an enormous impact on the development of public policies within the state as well as in terms of positioning Argentina as a leading state in the region with regards to the promotion and protection of human rights. In this context, respect for the autonomy and independence of the system … is … an element of its human rights policy. In addition, the jurisprudence of the system has constitutional status in Argentina, and has been the main source of law used to eradicate impunity for crimes against humanity, starting with the decisions of the National Supreme Court of Justice. Argentina sees its experience as an example of a country for which the system of individual cases, positively interpreted, could be transformed into an early alert mechanism that, rather than [constituting an] intrusion into internal affairs, became a tool for institutional improvement that produced very important results.Footnote 35

In addition to referencing the country’s identity as a leader in the development of international human rights norms, the passage reveals how a series of domestic forms of embeddedness shaped, and perhaps ultimately constrained, Argentina’s position vis-à-vis the reform process. Like in the case of Mexico, the internalization of international human rights law both via the constitutionalization of relevant treaties and receptive judicial practices, framed the kind of public positions finally adopted in international fora. It is likely that CELS leveraged these forms of embeddedness when lobbying foreign ministry officials for a change of approach. The NGO’s claim to influence is credible because during this period it had a very close relationship with the government, in part because of the Kirchner administration’s support for criminal prosecutions.

As a result of these changes in the public stances of both Argentina and Brazil, the Bolivarian position at the 2013 special meeting of the OAS General Assembly was much weaker. In fact, according to Spanish newspaper El País, ALBA nations were now “isolated.”Footnote 36 The assembly debated the Commission’s official response to the SWG, which only made cosmetic changes to internal procedures.Footnote 37 The new internal guidelines of the Commission incorporated some of Brazil’s recommendations regarding precautionary measures. For example, the document provides a relatively detailed explanation of the meaning of terms such as “urgency,” “gravity,” and “irreparability,” key parameters for deciding when to apply such measures. In addition, the Commission made a commitment to include the promotion of the universal ratification of the ACHR as a key pillar of its Strategic Plan, a nod to the Bolivarian nations. Yet countries like Ecuador were still not satisfied and threatened to vote against the resolution. At this stage, Argentina, which was still on excellent terms with ALBA nations but had also publicly declared interest in preserving the IASyHR, brokered an agreement: the Commission’s new guidelines would receive a stamp of approval, but the debate would not end there. The fact that the General Assembly approved the document was important because it meant that the Commission was still sovereign when it came to drafting its own new internal guidelines.