INTRODUCTION

There is an ongoing debate about whether informal institutions, such as the particularistic interpersonal relationship called guanxi, become more or less important as formal institutions are established (Guthrie, Reference Guthrie1998; Horak & Restel, Reference Horak and Restel2016). This debate focuses on China's transition from a planned to a market economy over the last four decades, during which the state's role in coordinating economic activities declined, and formal and legal institutions were developed (Guthrie, Reference Guthrie1997; Nee, Reference Nee1992; Walder, Reference Walder1992). Guanxi is a set of interpersonal connections that facilitate exchange of favors between people (Bian, Reference Bian1997). The cultural view suggests that guanxi persists in Chinese society no matter how the institutional environment changes because its roots reside in the Confucian culture (Yang, Reference Yang1994). Consistent with this argument, previous research has found that the effect of guanxi on entry-level wages in the Chinese labor market persisted after the reform (Bian & Huang, Reference Bian and Huang2015a), and the role of guanxi in finding jobs increased after the reform (Bian, Reference Bian1997, Reference Bian2002; Bian & Huang, Reference Bian and Huang2015b), especially in the state sector (Tian & Lin, Reference Tian and Lin2016). However, the institutional view argues that the importance of guanxi has declined in China as the development of rational and legal system has resolved the institutional uncertainty that fosters guanxi behavior (Guthrie, Reference Guthrie1998). A meta-analysis study supports this argument by showing that, although guanxi with business partners remains important for organizations, the importance of guanxi with the government has declined over time (Luo, Huang, & Wang, Reference Luo, Huang and Wang2013).

Previous research has focused on the development of formal institutions in the market, which has influenced guanxi behavior outside of organizations. However, few studies have investigated how the development of formal institutions influences guanxi behavior within organizations (Lin, Reference Lin2011a). Walder (Reference Walder1983) suggests that the underdevelopment of formal institutions in socialist enterprises stimulates employees to cultivate personal relationships with their supervisors. How does the supervisor-subordinate guanxi evolve with the development of formal institutions in state-owned enterprises? In this article, I investigate how socialist institutions influence supervisor-subordinate guanxi as these institutions have been gradually abolished during the privatization reform in China.

Building on institutional logics theory (Thornton, Ocasio, & Lounsbury, Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012), this article suggests that supervisor-subordinate guanxi has become an institutionalized practice of SOEs, which results in the collective identity of employees. To the degree that this identity is abolished, employees’ guanxi behavior will decline, as well. Utilizing a unique sample in the reform context of China, I study employees’ guanxi behavior in three types of organizations having different degrees of state ownership – SOEs, public firms, and joint ventures. Joint ventures construct a collective identity that embodies the market capitalism logic among employees who display less guanxi behavior than do SOE employees. In contrast, because public firms do not dissociate from the SOE identity, their employees did not differ from SOE employees in guanxi behavior. This study shows that the agency of organizations in managing their collective identity has implications for employee behavior and is constrained by their ownership structure.

This study makes important contributions to the research of guanxi. First, it explores how the institutions adopted by organizations influence guanxi behavior within those organizations. Previous theorists have debated the influence of newly established formal institutions on informal institutions such as guanxi (Guthrie, Reference Guthrie1998; Horak & Restel, Reference Horak and Restel2016; Yang, Reference Yang1994). Institutional theory argues that the development of rational and legal institutions will reduce organizations’ guanxi practices (Guthrie, Reference Guthrie1998), whereas the cultural perspective suggests that individuals’ use of guanxi will persist (Yang, Reference Yang1994). Related empirical research has examined guanxi behavior between organizations, such as developing ties with business partners and the government (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Huang and Wang2013); or individual guanxi behavior outside organizations, such as finding jobs through guanxi (Bian, Reference Bian1997). In contrast, little is known about employees’ guanxi behavior within organizations. The cultural perspective would suggest that organizations adopting different institutions in China will exhibit similar guanxi behavior among their employees. In contrast, the institutional theory would predict declining guanxi behavior with the establishment of formal institutions in organizations. Thus, this study will examine these predictions on intra-organizational guanxi.

Furthermore, this study investigates the mechanism of how the institutions of organizations may influence employees’ guanxi behavior. Besides the mechanism of formal institutions replacing informal institutions, suggested by the previous research (Horak & Restel, Reference Horak and Restel2016), I suggest that the institutional logics dominant in organizations influence individual guanxi behavior through constructing a collective identity for individuals. This mechanism contributes to resolving the debate about how institutional transition influences the importance of guanxi in China. This study suggests that whether guanxi persists or declines depends on whether the collective identity underlying guanxi behavior is changed. If the identity is not changed, guanxi behavior will persist, despite the establishment of formal institutions.

Finally, this study explores the antecedents of guanxi behavior within organizations, which has widespread impact on organizational outcomes. In traditional Chinese organizations, such as SOEs, guanxi with one's supervisor is a typical motivator for employee commitment and organizational citizenship behavior (Hui, Lee, & Rousseau, Reference Hui, Lee and Rousseau2004). Although good guanxi benefits some employees, its use can engender negative effects for workplace justice and the ethical climate (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2009; Chen, Friedman, Yu, Fang, & Lu, Reference Chen, Friedman, Yu, Fang and Lu2009; Han & Altman, Reference Han and Altman2009). Previous research on the antecedents of employees’ guanxi behavior has focused on two levels – the cultural level and the individual level. At the cultural level, Lin (Reference Lin2011a) finds that since Taiwan preserves more of its Confucian culture, it tends to put more emphasis on guanxi than mainland China does. At the individual level, previous research on the antecedents of supervisor-employee guanxi has investigated individual factors – such as motivation (Zhang, Deng, Zhang, & Hu, Reference Zhang, Deng, Zhang and Hu2016), personality (Zhai, Lindorff, & Cooper, Reference Zhai, Lindorff and Cooper2013), skills (Wei, Liu, Chen, & Wu, Reference Wei, Liu, Chen and Wu2010), and values (Taormina & Gao, Reference Taormina and Gao2010) – as predictors of their guanxi behavior. However, previous research has seldom examined organizational factors that influence employees’ guanxi behavior. This article fills that gap and investigates how organizations can change employees’ guanxi behavior.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

Institutions and Guanxi Behavior

The institutional perspective suggests that guanxi behavior is an important reaction to the pre-reform institutions in China (Guthrie, Reference Guthrie1998). Since formal institutions in China, including procedures and laws for allocating economic resources, are underdeveloped, managers and organizations resort to informal institutions, such as guanxi, to coordinate economic activities and secure resources (Peng, Reference Peng2003; Xin & Pearce, Reference Xin and Pearce1996). This perspective also applies to the situation of SOEs, which are managed by a centralized hierarchy based on personal and positional power (Lin & Germain, Reference Lin and Germain2003). Although the allocation of wages follows a formal standard, and wages are allocated equally among workers (Giacobbe-Miller, Miller, & Zhang, Reference Giacobbe-Miller, Miller and Zhang1997), the distribution of other benefits is subject to managers’ subjective decisions. Managers have power not only over the allocation of a wide range of rewards – including bonuses, promotions, admission to the Party, job assignments, housing, ration coupons for scarce goods, personal leaves – but also over a series of punishments. The subjectivity and flexibility in the reward system motivate employees to access these benefits by cultivating personal relationship with their supervisors – i.e., engaging in guanxi behavior (Walder, Reference Walder1983).

Based on institutional logics theory, I suggest that the need to build guanxi is not only due to the low formalization of SOEs, but also is deeply related to the state socialism logic underlying SOEs. Friedland and Alford (Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991) define institutional logics as supraorganizational patterns of activities rooted in material practices and symbolic systems by which individuals and organizations produce and reproduce their material lives and render their experiences meaningful. According to institutional logics theory, institutions contain not only material practices, but also symbolic systems that imbue material practices with beliefs and meaning (Friedland & Alford, Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991; Scott, Reference Scott2001). China's institutional transition has involved a shift from state socialism logic to market capitalism logic (Greve & Zhang, Reference Greve and Zhang2017; Guthrie, Reference Guthrie2008). These two forms of logic not only specify different formal procedures and practices, but also contain different identities and schemas for individual actions. State socialism logic relies on state planning to allocate resources, with the state controlling product prices, organizational budgets, and manager appointments (Naughton, Reference Naughton1996). In the state distribution system, SOEs have historically faced soft budget constraints and access to government loans and purchases (Bai & Wang, Reference Bai and Wang1998; Walder, Reference Walder1984). Under the state's protection, managers have not felt strong pressure to reward individual performance. Instead, the culture of SOEs has emphasized group solidarity and interpersonal harmony (Burawoy & Lukacs, Reference Burawoy and Lukacs1985), and the relationship between managers and employees has emphasized communal sharing (Chen, Reference Chen2018). Under such an institutional logic, good guanxi with supervisors has become the basis of subordinates’ trust in their supervisors (Farh, Tsui, Xin, & Cheng, Reference Farh, Tsui, Xin and Cheng1998; Wong, Ngo, & Wong, Reference Wong, Ngo and Wong2003) and has enabled them to engage in an open-minded dialogue (Davidson, Van Dyne, & Lin, Reference Davidson, Van Dyne and Lin2017). Supervisors’ relationship with their subordinates has, indeed, influenced their allocation decisions, and employees’ guanxi behavior has influenced allocation outcomes, including bonuses, promotions, and challenging jobs (Chen & Tjosvold, Reference Chen and Tjosvold2007; Law, Wong, Wang, & Wang, Reference Law, Wong, Wang and Wang2000). Therefore, building guanxi with their supervisor became an important way for employees to achieve their career development in SOEs (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Liu, Chen and Wu2010).

In contrast, the market capitalism logic that was established during China's transition leads organizations to adopt a series of different institutions to manage their employees. The institutional logic of capitalism is the capitalization of human activities based on the prices generated from competition among private owners, and it emphasizes efficiency and compensates individuals for the value they create (Friedland & Alford, Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991). Following this logic, some SOEs have been partially privatized through public listing on the stock exchanges or through joint ventures with multinational companies (Walder, Reference Walder1995). The privatized companies enjoy fewer privileges than SOEs, facing tighter budget constraints and stronger market pressure (Zahra, Ireland, Gutierrez, & Hitt, Reference Zahra, Ireland, Gutierrez and Hitt2000). In addition, the reduction in state ownership emancipates privatized companies from the political constraints of government and allows them to adopt institutions that enhance their competitiveness and productivity, such as pay for performance (O'Connor, Deng, & Luo, Reference O'Connor, Deng and Luo2006). Compared to SOEs, privatized companies adopt more strategic human resource management practices (Ngo, Lau, & Foley, Reference Ngo, Lau and Foley2008), which emphasize individual performance in the allocation of rewards and promotions (Giacobbe-Miller, Miller, Zhang, & Victorov, Reference Giacobbe-Miller, Miller, Zhang and Victorov2003; Zhao & Zhou, Reference Zhao and Zhou2004). These universal personnel practices apply to all employees, regardless of their guanxi with supervisors (Pearce, Branyiczki, & Bigley, Reference Pearce, Branyiczki and Bigley2000).

The new institutions adopted by privatized organizations make guanxi behavior of employees less prevalent than in SOEs. As the institutional transition moves from a relationship-based, personalized exchange structure to a rule-based, impersonal transaction regime, the strategy of organizations shifts from being network-centered to market-centered (Peng, Reference Peng2003). Accordingly, the importance and prevalence of managers’ guanxi behavior declines (Gold, Guthrie, & Wank, Reference Gold, Guthrie and Wank2002; Guthrie, Reference Guthrie1998). The same logic applies to intra-organizational guanxi – i.e., supervisor-subordinate guanxi. With the development of formal institutions for labor recruitment, performance evaluation, and reward allocation in privatized companies, the flexibility and subjectivity of the incentive system that Walder (Reference Walder1983) refers to are reduced. As a result, employees do not need to resort to guanxi with supervisors to secure the outcomes that are important to them. Furthermore, the relationship between employees and their managers changes from a communal sharing model to a market pricing model, which emphasizes fair compensation for individual performance (Chen, Reference Chen2018). As the interaction between managers and employees focuses more on individual performance and productivity, their personal guanxi does not address the main concern of their interaction. Accordingly, in international joint ventures, employees’ trust in their supervisors is based less on their guanxi than it is in SOEs (Wong, Reference Wong2018). Therefore, guanxi will become less prevalent in privatized companies compared to SOEs. I hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1: The employees of privatized companies will exhibit less guanxi behavior than the employees of state-owned enterprises.

SOE Identity and Guanxi Behavior

This article also argues that an important mechanism underlying the prevalent guanxi behavior in SOEs is the collective identity held by their employees. According to institutional logics theory, institutions influence organizational and individual behaviors through constructing and activating identities (Meyer & Hammerschmid, Reference Meyer and Hammerschmid2006; Rao, Monin, & Durand, Reference Rao, Monin and Durand2003); focusing attention and formulating goals (Thornton, Reference Thornton2004); and providing schemas and scripts for symbolic interaction (Barley & Tolbert, Reference Barley and Tolbert1997; Seo & Creed, Reference Seo and Creed2002). Thus, different institutional logics construct different identities, goals, and behavioral scripts for organizations and individuals. One key mechanism by which institutions influence organizations and individuals is through constructing collective identities (Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012). ‘A collective identity is the cognitive, normative, and emotional connection experienced by members of a social group because of their perceived common status with other members of the social group’ (Thornton & Ocasio, Reference Thornton, Ocasio, Greenwood, Oliver, Suddaby and Sahlin2008). Collective identities usually emerge among populations of organizations that adopt a particular organizational form (Haveman & Rao, Reference Haveman and Rao1997). The collective identity embodies the institutional logic and becomes a target for the organization's members to identify with (Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta, & Lounsbury, Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011).

In the context of a transition economy, SOE is an important organizational form that creates a collective identity among employees (Peng, Bruton, Stan, & Huang, Reference Peng, Bruton, Stan and Huang2016). Under the institutional logic of socialism, the power of the state in coordinating economic activities is an important reason that organizations tend to build guanxi with government. A review of previous research consistently shows that guanxi is more important in the state sector than in the non-state sector (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Huang and Wang2013; Tian & Lin, Reference Tian and Lin2016). Because SOEs rely more on government protection to access scarce resources, SOE managers develop more government ties (Li, Yao, Sue-Chan, & Xi, Reference Li, Yao, Sue-Chan and Xi2011). These ties play a more important role in the firm performance of SOEs than in that of non-SOEs (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Huang and Wang2013). Guanxi with government authorities can even help SOE managers save their positions during downsizing (Ma, Reference Ma2015). As a key component of the centralized socialism economy, SOEs are regarded as ‘branch plants of a single giant firm’ (Groves, Yongmiao, McMillan, & Naughton, Reference Groves, Yongmiao, McMillan and Naughton1994). When members of a group are bonded together in a coherent social unit, a stereotype about the group tends to form (Crawford, Sherman, & Hamilton, Reference Crawford, Sherman and Hamilton2002; Rydell, Hugenberg, Ray, & Mackie, Reference Rydell, Hugenberg, Ray and Mackie2007). As a representation of state socialism logic, the stereotype of SOE is well accepted in transition economies: shortages and overemployment; workers who don't work hard; effort that is not rewarded; and workers who depend on managers for the allocation of benefits (Burawoy & Lukacs, Reference Burawoy and Lukacs1985).

Since the identity of SOE has been deeply intertwined with guanxi, it directly shapes the behavior of individuals who hold that identity. Institutional theory suggests that practices are more likely to be institutionalized – they become instilled with value and taken-for-granted as normatively appropriate – if they are upheld by supra-organizational belief system that offers a positive interpretation of the practice (Zajac & Westphal, Reference Zajac and Westphal2004). In the context of a state socialism economy, guanxi behavior has been closely intertwined with the state socialism logic that validates the communal relationship between supervisors and subordinates and becomes a taken-for-granted way of how people should behave in SOEs. Once a stereotype is formed, its persistence defies organizational reality (Burawoy & Lukacs, Reference Burawoy and Lukacs1985). Even if the incentive system of SOEs changes, the stereotype of SOE remains deeply held and resistant to change (Greenwood & Hinings, Reference Greenwood and Hinings1996). Previous research has found that the reform in China has tightened SOEs’ budget constraints and delegated more control to managers (Dong & Putterman, Reference Dong and Putterman2003). As result, SOEs are increasingly establishing formal rules and adopting market-driven labor practices, such as piece-rate wages (Groves et al., Reference Groves, Yongmiao, McMillan and Naughton1994; Keister, Reference Keister2002). In addition, the development of the labor market has given workers bargaining power that may potentially alleviate the burden of engaging in guanxi behavior (Guthrie, Reference Guthrie2002). Despite these changes in formal institutions, there is still inertia in people's conception of SOEs, and employees still perceive guanxi as an important behavior (Gu & Nolan, Reference Gu and Nolan2017; Wu, Chen, & Leung, Reference Wu, Chen and Leung2011). When individuals identify as SOE employees, they will behave according to what they believe a typical SOE employee does – i.e., build guanxi with supervisors. I hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2: Identification with SOEs will be positively related to employees’ guanxi behavior.

Organizational Ownership and SOE Identity

Because of the strong association between guanxi and SOE identity, the extent to which this identity is changed with the introduction of market capitalism logic will have implications for employees’ guanxi behavior. Institutional logics theory suggests that the complexity of institutional logics in which actors are embedded enables them to perform agency in choosing how to respond to different institutional logics (Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012). Previous research suggests that identity work mediates the process of institutionalization (Lok, Reference Lok2010) and is the mechanism underlying the way that organizations resolve institutional contradiction (Creed, DeJordy, & Lok, Reference Creed, DeJordy and Lok2010). In the context of China, the introduction of market capitalism logic through the privatization process creates institutional contradiction, which needs to be resolved through identity work. Such identity work will have implications for employee guanxi behavior, which has been institutionalized as a practice of state socialism logic and associated with the identity of SOEs.

Furthermore, I argue that the form of identity work that organizations choose is constrained by their ownership structure. An important factor that influences how organizations react to institutional complexity is their ownership structure and corporate governance (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011). The gradualistic reform in China has created different types of organizations, with varying ownership structures (Nee, Reference Nee1992; Nee, Opper, & Wong, Reference Nee, Opper and Wong2007). In this study, I focus on SOEs that were partially privatized via public listing on stock exchanges and joint ventures formed between state-owned parent companies and multinational companies, two of the primary ways to transfer property rights to private holders (Walder, Reference Walder1995). Specifically, I suggest that the ownership structure of different types of organizations will influence how they respond to the competing state socialism and market capitalism logics in China.

Joint ventures’ ownership structure and corporate governance allow them to construct a new identity that is more aligned with the market capitalism logic. A successful transition requires dissociation from old identities and construction of new identities (Biggart, Reference Biggart1977; Fiol, Reference Fiol2002). In order to construct a new identity, the power of the representative of new institutional logics is very important (Greenwood & Hinings, Reference Greenwood and Hinings1996; Tilcsik, Reference Tilcsik2010) because it enables actors to utilize the cultural resources inherent in new institutional logics to reconstruct and transform their identities (Friedland & Alford, Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991). Multinational companies, which represent the market capitalism logic of developed countries, have advanced technology, management experience, and abundant capital (Guthrie, Reference Guthrie2005). Because of their advantages, they usually play a dominant role in the establishment of joint ventures and control half of the shares of such ventures (Clark & Geppert, Reference Clark and Geppert2006; Guthrie, Reference Guthrie1999). Their dominant position helps joint ventures construct a distinctive identity – ‘joint venture’ – as a target for individual identification (Jane & Oded, Reference Jane and Oded2001). Although state-owned parent companies are also shareholders of joint ventures, their influence in joint ventures weakens. As a result, the role of SOEs in employee identity will be weakened, as well. The collective identity of a joint venture can assimilate individual behaviors with the market capitalism logic, which emphasizes meritocracy and rewards for individual performance, regardless of employees’ guanxi with supervisors. As employees of joint ventures adopt this new identity, they will dissociate from the behavioral pattern of SOEs. Therefore, I hypothesize that the difference in guanxi behavior between joint ventures and SOEs will be mediated by the degree to which their employees identify with SOEs.

In contrast, due to the ownership structure and corporate governance of public firms, their employees may maintain SOE identity. After the establishment of stock markets in Shanghai and Shenzhen in 1990 and a series of regulations (National People's Congress, 2001; The Fifth Meeting of the Standing Committee of the Eighth National People's Congress, 1993), public listing on the stock market became an institutionalized approach for privatizing SOEs. However, this approach to privatization allows the state – as represented by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) – to maintain the majority share and play a dominant role in public firms (Guthrie, Xiao, & Wang, Reference Guthrie, Xiao and Wang2009). Typically, public listing of an SOE allows the state to retain between 40% and 50% of the company's shares. Between 20% and 30% of the shares are designated for institutional shares, and the remaining approximately 30% are designated for public consumption as free-floating shares (Guthrie, Reference Guthrie1999; Xu & Wang, Reference Xu and Wang1999). The state's dominant ownership of and influence in public firms are stronger and less counterbalanced by alternative power than those in joint ventures. Therefore, it is harder for employees of public firms to develop distinctive identities and to dissociate from the SOE identity. Since the employees of public firms still identify with SOE, they may exhibit the related behavioral pattern – i.e., building guanxi with supervisors. Taken together, organizations’ identity work in resolving institutional contradiction is constrained by their ownership structure: unlike joint ventures which can construct an identity coherent with market capitalism logic, public firms are more likely to maintain the SOE identity, and, hence, their employees’ guanxi behavior will be similar to that of SOE employees. Therefore, I hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3: SOE identification mediates the difference between privatized organizations and SOEs in terms of employee guanxi behavior.

In summary, this article compares employees’ guanxi behavior between SOEs and privatized organizations, including public firms and joint ventures. I hypothesize that employees of privatized organizations will exhibit less guanxi behavior than will SOE employees, and such a difference is mediated by identification with the SOE. Since joint ventures construct a distinctive collective identity, their employees exhibit less guanxi behavior than do SOE employees. In contrast, because employees of public firms still identify with SOEs, their guanxi behavior does not differ from that of SOE employees. This study examines this identity mechanism after controlling for the impact of formal institutions, as suggested in the previous literature.

METHODS

Through a unique sample and research design, this study attempts to capture the institutional diversity in China by looking at the continuing evolution of the state sector, holding some key institutional variables constant while allowing others to vary. Looking at organizations under SASAC's supervision in one city holds the macro-level environment constant to a certain extent. Due to the gradualistic nature of the reform, some SOEs are not privatized and still persist in the post-reform Chinese economy (Lin, Reference Lin2011b). Under the same institutional context, this study compares individual behavior in firms that are (1) still state-owned, (2) publicly-listed, and (3) joint ventures. These three types of organizations have different degrees of state ownership and control – highest in SOEs and lowest in joint ventures.

Sample and Procedure

I acquired access to the field through a consulting project for Shanghai SASAC. First, I randomly selected 12 of the 40 business groups in which to conduct interviews with top managers. Among the 12 business groups, four agreed to participate in the survey study. These business groups covered multiple industries: food, commercial, chemical, and automobile. For each business group, I included different organizational types, resulting in four SOEs, three public firms, and five joint ventures. The proportion of state ownership of SOEs were all above 0.90. The proportion of state ownership for public firms varied between 0.39 and 0.57. The five joint ventures were all formed between SOEs and foreign companies, and their proportion of state ownership varied from 0.30 to 0.70, with the majority at 0.50. The sample design is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The sample structure

Between 50 and 100 respondents from each firm (800 in total) were selected; of these, 721 submitted the survey, resulting in a response rate of 90%. The sample was evenly distributed among the three types of organizations: 282 from traditional SOEs, 230 from public firms, and 209 from joint ventures. In order to form a stratified random sample of each firm and to ensure comparability between firms, I requested a universal composition of employees at different hierarchical levels among all the firms. I calculated the number of employees at each hierarchical level to be chosen for each firm. The firms randomly selected respondents at each hierarchical level from the directory of employees. The survey was conducted anonymously at the companies. The researchers explained to the participants that the purpose of the study was scientific research and that their responses would not be disclosed to their managers.

Measures

In order to explore what identities individuals actually held, I included an open question at the beginning of the survey: ‘Imagine you are attending a party of old classmates. How would you introduce yourself’? This question was adapted from the Twenty Statements Test, which asks respondents to write 20 answers to the question ‘Who am I’? on a situation that is familiar to Chinese respondents (Rees & Nicholson, Reference Rees, Nicholson, Cassell and Symon1994).

Independent variables

Public and joint venture were dummy variables to represent different types of organizational ownership. The dummy variable SOE was used as the benchmark for comparison.

Dependent variable

Guanxi behavior was measured by six items widely used in previous research (Law et al., Reference Law, Wong, Wang and Wang2000). Respondents were required to indicate the extent to which they agree with these statements on a five-point scale, such as ‘During holidays or after office hours, I would call my supervisor or visit him/her’. (1 = ‘strongly disagree’, 5 = ‘strongly agree’)

Mediating variables

In order to measure the extent to which participants incorporate the collective identity of SOEs into their identities, I measured SOE identification by adapting the target in Mael and Ashforth's (Reference Mael and Ashforth1992) organizational identification scale to ‘SOE’. An example item is: ‘Working at an SOE is important to the way that I think of myself as a person’. Respondents answered the five items using a five-point scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’, 5 = ‘strongly agree’).

Control variables

Demographic variables such as gender and education were included because these factors may influence individuals’ chances for career advancement and their probability of engaging in guanxi behavior (Walder, Li, & Treiman, Reference Walder, Li and Treiman2000; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Liu, Chen and Wu2010). Hierarchical position was also included because it may affect the importance of political factors in promotion (Li & Walder, Reference Li and Walder2001), such as guanxi behavior. Since organizational tenure may influence individuals’ chances of promotion (Zhao & Zhou, Reference Zhao and Zhou2004), it was also included.

This study also controlled for alternative explanations of guanxi behavior. First, the formalization of organizational procedures may reduce the need to engage in guanxi behavior (Walder, Reference Walder1983), so it was included and measured by five items from a previous study (Pugh, Hickson, Hinings, & Turner, Reference Pugh, Hickson, Hinings and Turner1968). An example item is: ‘The organization keeps a written record of nearly everyone's job performance’. In order to rule out the impact of management style on guanxi behavior, I controlled for hierarchy of organizational structure because Walder (Reference Walder1983) suggested that the power of managers is an important driver of employee guanxi behavior. Hierarchy was measured by four items from a previous scale (Pugh et al., Reference Pugh, Hickson, Hinings and Turner1968), such as ‘There can be little action here until a supervisor approves a decision’. Respondents used a five-point scale (1 = ‘not at all’, 5 = ‘very closely’) to indicate the extent to which these statements described the situation in their organizations.

Instrumental variables

In order to address the endogeneity concern – those who engage in guanxi behavior are more likely to join SOEs than public firms and joint ventures – I used instrumental variables that are related to the independent variables. I chose pride in their organization and self-esteem as instruments for public firms and joint ventures. Because they generally have higher firm value than SOEs (Wei & Varela, Reference Wei and Varela2003), their employees should have higher pride and self-esteem. Furthermore, pride in one's organization and self-esteem are not theoretically related to guanxi behavior because this behavior has both positive and negative connotations (Han & Altman, Reference Han and Altman2009). Therefore, they qualify as instrumental variables in this study. I measured pride with an existing scale containing five items, such as ‘My company is one of the best companies in its field’ (Blader & Tyler, Reference Blader and Tyler2009) (α = 0.85), and measured self-esteem with the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (Reference Rosenberg1965) (e.g., ‘I feel that I have a number of good qualities’; α = 0.84).

RESULTS

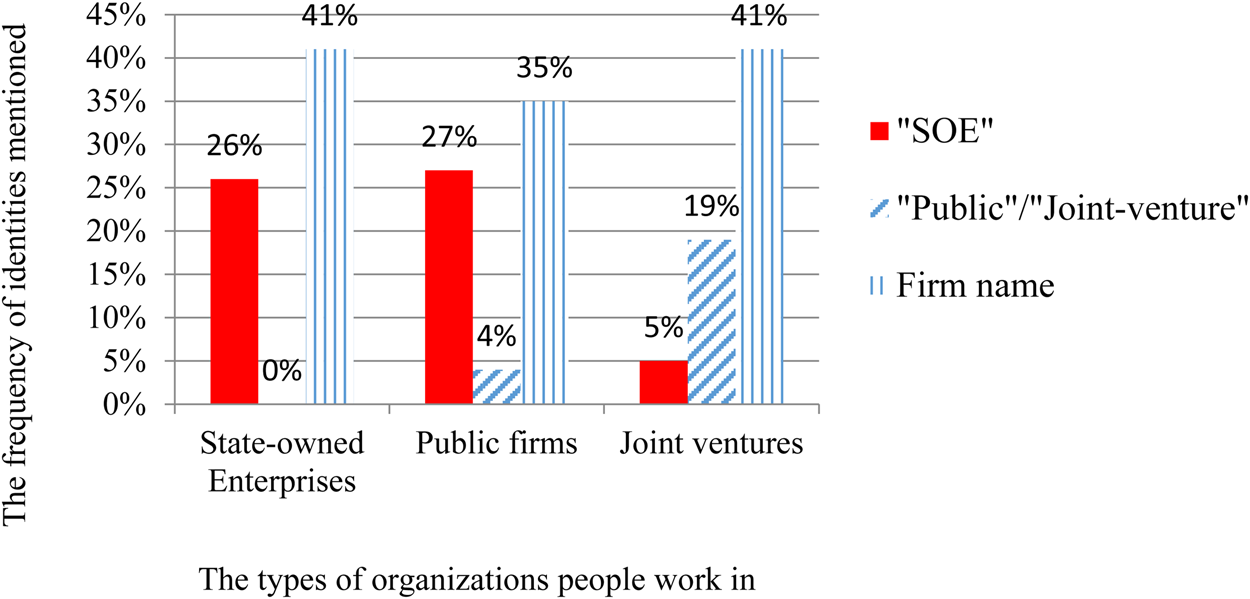

In order to explore the salience of different categories and groups in individual identities, I summarized the frequency of mentioning ‘SOE’, ‘public firm’, ‘joint venture’, and firm names in respondents’ self-introduction to the open question in Figure 2. To analyze whether employees from different types of organizations used each category differently, I conducted a multinomial logistic regression. Employees working at SOEs (b = 1.86, s.e. = 0.76, W (1) = 5.94, p = 0.015, Odds = 6.41) and public firms (b = 1.85, s.e. = 0.77, W (1) = 5.74, p = 0.017, Odds = 6.34) were more likely to use the term ‘SOE’ in their self-introduction than were employees working for joint ventures (χ2 (2) = 9.93, p = 0.007). These results indicate that the public firms’ employees still identified with SOEs. Furthermore, public firm employees’ usage of ‘public firm’ was lower than joint venture employees’ usage of ‘joint venture’ (b = -1.78, s.e. = 0.72, W (1) = 6.04, p = 0.014, Odds = 0.17), showing that joint ventures are better than public firms at establishing a distinctive identity. In addition, the frequency of mentioning firm names in self-introduction was not significantly different across the three kinds of organizations (χ 2 (2) = 0.67, p = 0.72), indicating that identity difference focused on the collective organizational form, rather than on the specific organizations.

Figure 2. The frequency of mentioning different identities in self-introduction by employees working in different types of organizations

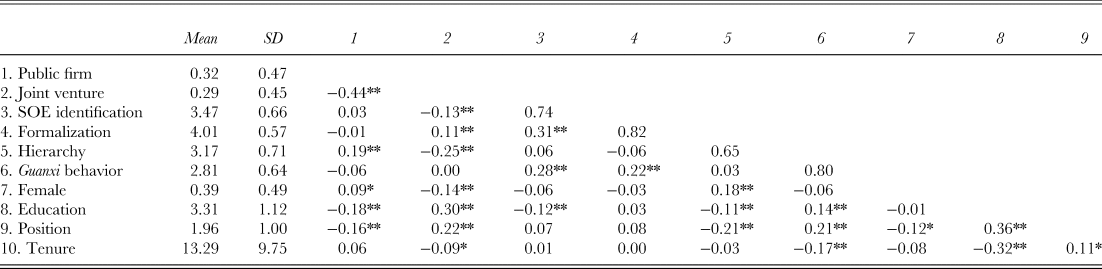

I further conducted confirmatory factor analysis to examine the measurement validity. The measurement model, which included formalization, hierarchy, SOE identification, and guanxi behavior as factors, fit very well with the data (χ2 (145) = 432.50, p = 0.000, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.05, PCLOSE = 0.21, SRMR = 0.05). The factor loadings of variables are presented in Table 1. In order to examine whether common method bias was driving the relationship between variables, I conducted the single-factor test with confirmatory factor analysis (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon and Podsakoff2003). The model that loaded all the items onto one factor did not fit the data (χ2 (152) = 2593.70, p = 0.000, CFI = 0.40, TLI = 0.33, RMSEA = 0.15, PCLOSE < 0.001, SRMR = 0.13). Therefore, the common method cannot explain the relationship between variables. The descriptive analysis results are presented in Table 2.

Table 1. Factor loadings of measured variables in confirmatory factor analysis

Table 2. Correlations and descriptive statistics a

Notes: a Entries on the diagonal are Cronbach's alphas. For position, 1 = Employee, 2 = Supervisor, 3 = Middle manager, 4 = Top manager. For education, 1 = Middle school, 2 = High school, 3 = College, 4 = Bachelor, 5 = Master or higher.

* p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01

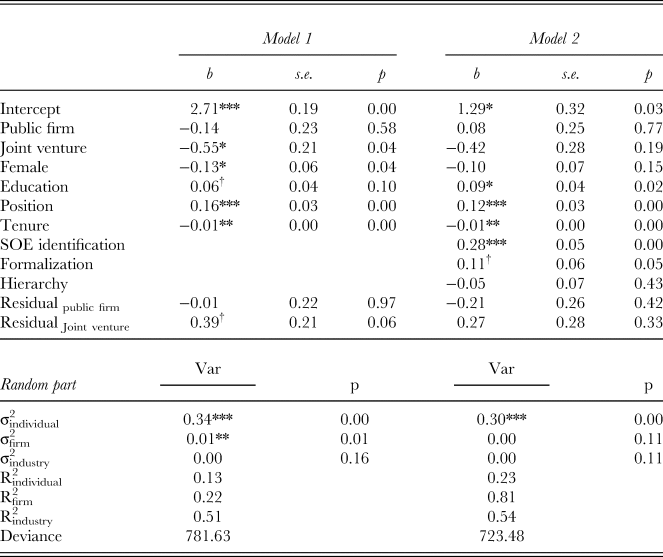

Given the nested nature of the data, I used HLM7 to test the hypotheses (Hox, Reference Hox2010). I constructed a three-level model to control for firm-level and industry-level variances. Because public firm and joint venture were binary variables, I used the two-stage residual inclusion method to address the endogeneity issue (Terza, Basu, & Rathouz, Reference Terza, Basu and Rathouz2008). Specifically, I performed a logistic regression of public firm and joint venture on the instrumental variables – pride and self-esteem – and all the other variables. As expected, public firm employees were prouder of their organizations than SOE employees were (b = 0.87, s.e. = 0.20, p = 0.000); and joint venture employees had higher self-esteem than SOE employees (b = 0.99, s.e. = 0.25, p = 0.000). The residuals from these logistic regression models were included in the hierarchical linear models. The results on guanxi behaviors are presented in Table 3. The residuals did not have a significant effect on guanxi behavior, indicating that the selection of individuals to different types of organizations was not a serious issue. In Model 1 of Table 3, females and employees with longer tenure engaged in less guanxi behavior. Employees with a higher education level or position engaged in more guanxi behavior. Compared to SOEs, public firms did not have a significant effect on guanxi behavior (Odds = -0.28), whereas joint ventures had a significant negative effect on guanxi behavior (Odds = -1.1), partially supporting H1. These variables explained 13% of variance at the individual level, 22% of variance at the firm level, and 51% of variance at the industry (business group) level. The model fit was calculated according to the procedure of reduced variance suggested by Hox (Reference Hox2010), so no significance test could be conducted. In Model 2 of Table 3, formalization had a marginally significant positive effect on guanxi behavior, and the effect of hierarchy was non-significant. SOE identification had a significant positive effect on guanxi behavior, supporting H2. These variables explained an additional 10% of variance at individual level, 59% of variance at the firm level, and 3% of variance at the industry level. After SOE identification was included, the effect of joint ventures became non-significant, indicating the existence of a full mediation effect.

Table 3. Hierarchical linear models of Guanxi behaviora

Notes: a Entries are unstandardized regression coefficients. SOE was the reference category.

†p < 0.10, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

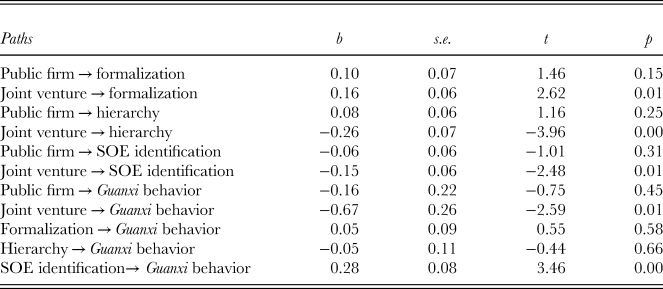

In order to test the mediating effect of SOE identification, I used the bootstrapping approach of the structural equation model, with a significant indirect effect representing the existence of the mediation effect (Kline, Reference Kline2005). The data were analyzed in Mplus. The coefficients of the structural equation model are presented in Table 4. Joint ventures were more formalized and had a lower hierarchy than SOEs. Neither formalization nor hierarchy had a significant effect on guanxi behavior. Joint ventures had a negative effect on SOE identification, but the effect of public firms was non-significant. Through SOE identification, the indirect effect of joint ventures on guanxi behaviors was significant (indirect effect = -0.04, s.e. = 0.02, t = -1.99, p = 0.046), but the indirect effect of public firms was not significant (indirect effect = -0.02, s.e. = 0.02, t = -0.91, p = 0.36). The indirect effect through formalization was non-significant for joint ventures (indirect effect = 0.01, s.e. = 0.02, t = 0.52, p = 0.60) or public firms (indirect effect = 0.01, s.e. = 0.01, t = 0.43, p = 0.67). Nor was the indirect effect through hierarchy significant for joint ventures (indirect effect = 0.01, s.e. = 0.03, t = 0.42, p = 0.68) or public firms (indirect effect = -0.00, s.e. = 0.01, t = -0.33, p = 0.74). These results support H3, which states that SOE identification mediates the effect of joint ventures on guanxi behavior.

Table 4. The coefficients of structural equation model of mediation effects

Note: the coefficients of control variables were not reported in the table.

DISCUSSION

This article aims to understand how the development of formal institutions in organizations influences intra-organizational guanxi. Building on institutional logics theory, I argue that the institutions that organizations adopt construct the collective identities of employees. These collective identities embody institutional logics and develop into a stereotype of how individuals behave in the collective. To the extent that individuals identify with the collective, they will behave according to its stereotype. In the setting of China's transition economy, the state socialism logic has generated the stereotype of prevalent guanxi among SOEs. This study finds that the more that individuals identify with SOE, the more guanxi behavior they engage in within their organizations. The way in which privatized organizations manage this collective identity is contingent on their ownership structure.

The formation of joint ventures leads to a significant deviation from the SOE identity. Employees of joint ventures identify less with SOEs and exhibit less guanxi behavior than SOE employees do. The construction of the new identity ‘joint venture’ transforms employees’ mindset and helps them unlearn the behavioral script of the state socialism logic. An important reason for the radical deviation of joint ventures from the SOE identity is the presence of a counter-balancing power – multinational companies. Therefore, successful institutional transition requires counterbalancing power, which enables the construction of new identities and a change in behavior. Public firms, on the contrary, have not deviated from the SOE identity as joint ventures have. The continued influence of the state sustains individuals’ identification with SOEs and constrains the extent to which public firms can freely construct a distinctive identity. Since employees of public firms still identify with SOEs, their guanxi behavior does not differ from that of SOE employees. Overall, this article suggests that in order to fully actualize the potential of organizational transformation, identity management must accompany ownership change.

It is noteworthy that these organizations do differ in organizational structure and procedures, as evidenced by the increased formalization and decreased hierarchy of joint ventures compared to SOEs. However, these structural elements have not reduced guanxi behavior significantly. On the contrary, formalization has had a positive association with guanxi behavior. This finding is consistent with previous research (Horak & Klein, Reference Horak and Klein2016) showing that guanxi complements formal institutions in coordinating economic and social exchanges (Horak & Restel, Reference Horak and Restel2016). The development of formal institutions resolves part, but not all, of the uncertainty regarding these exchanges, thus leaving room for informal institutions to play a role – a phenomenon that has been found across cultures (Bian & Ang, Reference Bian and Ang1997; DiTomaso & Bian, Reference DiTomaso and Bian2018; Liu, Keller, & Hong, Reference Liu, Keller and Hong2015). For instance, the formal procedure of performance measurement provides a common standard by which to evaluate individual performance, but it may require supervisor evaluation and still leave room for individuals to pursue competitive advantage through guanxi. Indeed, previous research has viewed guanxi behavior as a strategy to enhance one's career development (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Liu, Chen and Wu2010), and people who engage in guanxi behavior tend to attribute their success to their own actions (Taormina & Gao, Reference Taormina and Gao2010). This study also finds that guanxi is used more by people with a greater chance of career advancement, such as employees with higher education and position (Walder et al., Reference Walder, Li and Treiman2000; Zhao & Zhou, Reference Zhao and Zhou2004), and less by those with less chance of career advancement, such as female and senior employees (Li & Walder, Reference Li and Walder2001; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Liu, Chen and Wu2010). This finding suggests that the development of formal institutions may precipitate, rather than reduce the use of guanxi in organizations.

Theoretical Contributions and Practical Implications

This study makes important contributions to the research. First, it extends the explanation of employees’ guanxi behavior to the organizational level. This article suggests that employees’ guanxi behavior is a reaction to the socialist institutions adopted by SOEs. The more that individuals identify with SOE, the more they enact the behavioral scripts of state socialism logic and build guanxi with their supervisors. That is, guanxi behavior has been institutionalized as a strategy to develop one's career in SOEs, and employees deploy this strategy to different degrees in different types of organizations. This systematic difference between organizations within the same culture complements the previous explanations of guanxi behavior through national culture or individual differences. Therefore, this article highlights the institutional origin of guanxi behavior within organizations and contributes to a deeper understanding of this important organizational phenomenon.

This article also sheds new light on the debate about the persistence or decline of guanxi in transition economies, such as China's. There are various arguments addressing whether guanxi has persisted or declined with the reform in China. The cultural argument is that guanxi has persisted, notwithstanding the reform (Yang, Reference Yang1994). The institutional argument is that guanxi has declined with the reform that establishes formal institutions in China (Guthrie, Reference Guthrie1998). This article focuses on the micro level and suggests that the importance of intra-organization guanxi follows the prediction of institutional theory and is lower in transformed organizations than in SOEs. The institutions that individuals have long been embedded in become part of their identity and have direct implications for how they should behave. Therefore, the SOE identity has been the cognitive pillar of the state socialism institution (Scott, Reference Scott2001), which happens to share the values inherent in the traditional culture of Chinese society (Farh, Hackett, & Liang, Reference Farh, Hackett and Liang2007). Cultural transformation is not easy to achieve because it requires a change in people's identity and mindset (Creed et al., Reference Creed, DeJordy and Lok2010; Seo & Creed, Reference Seo and Creed2002). Thus, this article resolves the debate by suggesting that guanxi persists if no identity change happens, and guanxi declines if identity change takes place. This insight can potentially be applied in explaining the persistence of guanxi behavior in Chinese culture – i.e., due to the deeply-held collective identity of the Chinese people and its guanxi-heavy stereotype.

In addition, this study makes an important contribution to the micro-mechanism of institutional transition. Previous research has recognized the importance of identity movement for institutional change (Rao et al., Reference Rao, Monin and Durand2003; Thornton & Ocasio, Reference Thornton, Ocasio, Greenwood, Oliver, Suddaby and Sahlin2008). However, empirical investigation of how organizations construct different identities, as well as their effect, has been lacking (Gioia, Patvardhan, Hamilton, & Corley, Reference Gioia, Patvardhan, Hamilton and Corley2013). This study suggests that organizations’ approach of identity management depends on their ownership structure and corporate governance. The dominance of multinational companies allows joint ventures to reconstruct their identity, so that their employees can identify with a different collective and dissociate from the SOE behavioral script. Public firms, on the contrary, maintain the SOE identity due to the continued influence of the state and, hence, are less effective in transforming the behavior of individuals. Lok (Reference Lok2010) suggests that actors can preserve an old favorable and autonomous identity, while fully adopting practices associated with the new logic. This study highlights the difficulty of doing so because of the deep coupling between the old identity and behavioral scripts.

Beyond the theoretical contributions, this study also holds implications for management practices. The implication for general management is that organizations should be very cautious in choosing the categories to affiliate with, as the categories will become part of their members’ identity, which further influences their behavior. For transition economies, this study uncovers the micro mechanism of why continued state dominance postpones reform progress. A special characteristic of China's reform is the continued influence of state (Lin, Reference Lin2011b). Previous research has shown that guanxi is prevalent in the state sector and has even displayed an increasing trend (Tian & Lin, Reference Tian and Lin2016). According to the findings of this study, the continued influence of the state maintains the SOE identity and its related behavioral pattern. In order to achieve the objective of institutional transition, an identity shift must accompany structural changes. Therefore, privatized organizations should reconstruct the identity of their employees to deviate from the SOE identity.

Limitations and Future Research Implications

Despite its contributions, this study has some limitations. This study used self-report to measure guanxi behavior because individuals are best informed of such private behaviors. I acknowledge that self-report may cause common method bias in testing the relationship between SOE identification and guanxi behavior, although the single-factor test has suggested otherwise. Controlling for other variables measured in the same way, such as formalization and hierarchy, helps mitigate this problem because control variables have already accounted for the variance caused by the method (Siemsen, Roth, & Oliveira, Reference Siemsen, Roth and Oliveira2010). Nevertheless, future research should measure guanxi behavior through other sources (such as supervisor evaluation) or methods (such as experiment) to replicate the findings (Horak, Reference Horak2018).

The absence of a pre-test of behavior before organizational change limits my capability to make causal predictions about the effect of institutional logics. The long-lasting reform process makes it difficult to track individual behaviors from the beginning of the reform, but previous studies demonstrate that the management practices of SOEs were homogeneous before the reform (Walder, Reference Walder1983). Therefore, under the old institution, one can assume that guanxi behavior was similar among organizations before the reform. In addition, because the assignment of organizations to different ownership change is based primarily on strategic considerations such as firm size, reverse causality – the firms with less guanxi behavior among employees were selected for reform – is not a plausible explanation for the findings of this study. However, future research can adopt an experimental approach to examine the causal effect of institutional logics (Horak, Reference Horak2018).

Finally, this study focused on privatization through public listing and building joint ventures, which are the prevalent approaches to transforming large SOEs in Shanghai. One neglected approach to privatization is the transfer of property rights to private holders. Previous research has found many similarities between private companies and foreign-controlled joint ventures in management practices and employee motivation (Chiu, Reference Chiu2002; Gong & Chang, Reference Gong and Chang2008). Moreover, such radical privatization engenders stronger market pressure and deviation from the SOE identity. Therefore, the inclusion of wholly privatized companies would increase the variance of independent variables and provide a more lenient test of the hypotheses. Future research could follow individual behaviors in firms that become controlled by private owners and test the generalizability of this study's conclusions.

CONCLUSION

To summarize: focusing on the reform context, this study investigated the impact of different institutions adopted by organizations on individual guanxi behavior. The reform in China generates complexity on the institutional logics and associated formal institutions adopted by organizations. This study found that compared to SOE employees, joint venture employees showed less guanxi behavior, mainly through reduced identification with SOEs. Because employees of public firms maintained their SOE identity, their guanxi behavior did not show a significant difference from that of SOE workers. These results suggest that guanxi behavior has been deeply coupled with the state socialism logic of SOEs and highlight the challenges of institutional transition.