“There are no distant points in the world any longer,” announced Wendell Willkie, the 1940 Republican presidential candidate, in the opening moments of his 1943 bestseller, One World. Wide use of the airplane and a global war had not only shrunk space, he argued, but also pushed Americans toward a new understanding of their nation's political responsibilities. “Our thinking in the future,” he declared, “must be world-wide.”Footnote 1

Willkie's book recounted the story of the much-followed round-the-world trip he made in the late summer of 1942. Carrying messages to Allied leaders from his former rival, President Franklin Roosevelt, Willkie flew 31,000 miles in 49 days, making extended stops in the Middle East, the Soviet Union, and China. Enlivened by his homespun charisma and his easy encounters with world leaders and ordinary citizens alike, Willkie's book enjoyed great popular success and brought Americans one of the most compelling examples of “world-wide” thinking to emerge from the war. The Willkie moment—a period of two years between his trip in 1942 and his abrupt death in the fall of 1944—marked the high point for American visions of wartime internationalism.

Willkie was no innovator. He picked up on internationalist ideas already in circulation, and used his sudden fame to offer Americans the most widely read, seen, and heard version of an emerging world picture—a new set of imagined geographies through which they might understand the changing cultural and political spatial relations of the planet. Not an intellectual, diplomat, or leader of a social movement, his capacious vision, couched in a populist politician's tone of optimism and sentimentality, nevertheless appealed to broad audiences.Footnote 2 He announced a shrinking world full of peril and promise in which the planet's peoples were being drawn closer together—a world in which the United States in particular had become inescapably enmeshed.

To critics of twenty-first century globalization, this language—a world made small, a world made one—reads as little more than naïve universalism or triumphalist globalism. But Willkie intended a more incisive critique. Americans, he wrote, had to forego both “narrow nationalism”—his term for the so-called “isolationism” that had loomed large in the country's domestic politics in the interwar years—and the “international imperialism” practiced by the European powers. They should instead support “equality of opportunity for every race and every nation.”Footnote 3 Americans, he believed, had to see the true stakes of the war against fascism. The aspirations of colonized peoples revealed that racial inequality everywhere was a form of imperialism; “we cannot,” he argued, “fight the forces and ideas of imperialism abroad and maintain any form of imperialism at home.”Footnote 4 Willkie's “world-wide” thinking, then, imagined not simply a homogeneous realm. It was a world simultaneously made one, a universalist space with no divisions, and a world altered, with particular new questions of global spatiality and political relations brought to the fore.

Many have treated Willkie and his trip as emblematic of a fleeting surge of progressive internationalist opinion that quickly dissipated when the immediate goal of winning the war was achieved.Footnote 5 While not entirely incorrect, such interpretations slight the larger cultural and political significance of Willkie's book and trip—and what it reveals about the range and nuances of American internationalism during the war. Some historians have noted Willkie's prescience about the “multiculturalist” future of the world, but sustained attention has yet to be paid to the way Willkie not only helped revive the internationalism of Woodrow Wilson, but also expanded its terms.Footnote 6 By arguing that internationalism would rise and fall in tandem with American attention to the linked forces of race and empire, he not only superseded the liabilities of Wilson's attachment to white supremacy; he also inaugurated a “Willkie moment” to rival the earlier “Wilsonian moment”—a wartime period in which an idealistic American made himself a medium for the freedom dreams of the world's colonized peoples.Footnote 7

To be sure, Willkie's moment never equaled Wilson's. Although “one world” became a slogan for postwar anticolonial movements, Willkie did not galvanize new uprisings; he reacted to well-established currents of anti-imperial thought.Footnote 8 Ultimately, Willkie's significance was more subtle. He offered an expanded frame for the old Wilsonian energies, bringing to full flower long-evolving networks of international connectivity, while also revealing the moment's central dilemmas. Did his vision recast the world as a field of mutually interdependent relations in which empire—European and American—could be confronted and undone? Or did his “one world” imagine the opening of a vast undifferentiated space for the extension of U.S. power?

The Willkie moment stood at the apex of a longer period, stretching from Roosevelt's and Winston Churchill's Atlantic Charter in August 1941, which pledged Allied support for self-determination for people across the globe, to the establishment of the United Nations in 1944 and 1945. In these years, many Americans actively debated and partially accepted a new international order, though historians disagree about the nature of the mid-century liberal internationalist ideals underpinning these developments. Some view Willkie as contributing to a “New Deal for the world” that underwrote new multilateralist ideals and humanitarian organizations.Footnote 9 Others view liberal internationalism (and liberal anticommunism) as vehicles for the wartime spread of a newly emergent form of U.S. empire and global hegemony—one that simply refigured older patterns of American hemispheric and Pacific territorial conquest.Footnote 10

In order to understand the complex contours of the Willkie moment, we need to be able to see both of these tendencies at work. The thorny relations between multilateralism and empire stood at the heart of wartime diplomacy and postwar planning. U.S. officials, from President Roosevelt to Vice President Henry Wallace and Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, were invested in progressive internationalism, and even, to varying degrees, in anti-imperialism. Like other progressive internationalists of the era, Roosevelt and his advisers hoped to unseat the British and other European empires and to create a new multilateral institution to replace the League of Nations. Behind the scenes, however, the president and others pushed for a postwar global order overseen by his “four policemen”—the United States, Britain, China, and the Soviet Union—to support free trade and the economic power of U.S.-led liberal capitalism.Footnote 11

Willkie brought these debates outside the closed channels of formal diplomacy and into the broader public culture. His popular global vision reveals how intertwined the “multilateral moment” was with the evolution of American imperialism. As the older world system of European territorial empires gave way to a new U.S.-dominated global order, Willkie's “one world” vision, with its explicit consideration of the interlinked problems of race and empire, was rivaled only by Henry Wallace's speech “The Price of Free World Victory” as the most concentrated and broadly popular representation of the wartime dilemmas faced by officials, intellectuals, and regular citizens alike. As Or Rosenboim has shown, the war years saw the reemergence of the “global” as a “political space” among a transatlantic network of intellectuals and policymakers—one in which empire was contested, new visions of democratic practice elaborated, and the plurality of the world confronted.Footnote 12 A close analysis of Willkie's world tour, however, suggests just how difficult this new global vision was to sustain and how ambiguous Americans remained, particularly when confronted with the fact of their own territorial empire. Internationalists had struggled for years with the rise of the nation-state, the spread of empires, and the global elaboration of race-thinking, ever since the advent of organized internationalist ideals in the nineteenth century.Footnote 13 Willkie's “world-wide thinking” reinvigorated these debates, stoking hopes that the new physical and imaginative closeness brought on by war and the airplane would usher in a new global realm of “equality of opportunity.” But a closer look at the imagined geographies of the Willkie moment instead illuminates the difficulties in realizing a world that was simultaneously “interdependent,” free of imperial domination, and subject to benevolent American influence.

The Willkie moment encompassed at least three imagined geographies, all of which ultimately turned on the specific question of how Americans should confront the idea and fact of empire. First was Willkie's titular universalism—a vision of a shrinking world that combined with other popular spatial imaginaries of his era to map and encourage the sense of global, non-imperial interdependence that would lead, with some dilution, to the founding of the United Nations. However, Willkie also knew that “one world” universalism required Americans to recognize the world as already shaped by empire and race—at home and abroad—and to support the claims for self-determination made by people in hitherto dominated regions of the globe.

And so Willkie's second imagined geography—mapped out in the final third of One World—was one of empire contested. All across the globe, Willkie argued, demands for self-determination had been encouraged by a war the Allies had defined as a war for freedom and against fascism. The true world war was against racism and empire. A “war of liberation” put both European colonialism and American segregation under scrutiny. The United States had to challenge Europeans to give up their empires and dissolve what he called “our imperialisms at home.”Footnote 14 Willkie yoked race to empire, and the domestic to the international, in ways unprecedented for a figure of his stature and recognition. He brought relatively obscure debates from the anti-colonial left and the anti-imperialist thought of the African American freedom struggle to a nationwide public—an audience of millions for whom such questions were novel and challenging.

At the same time, however, Willkie was less explicit about American empire than European. Most notable, in retrospect, is how his overt universalist and anti-imperial geographies disguised a latent current of ambivalence about the United States's role in the world, hinting at a third geography of empire obscured. Here, American energies abroad remain occluded and unmapped in the emerging “one world.” Willkie's visit to Puerto Rico—unmentioned in One World—suggests how his connections with the two chief institutions of U.S. empire on the island—the sugar industry and the U.S. military—produced mental maps of Willkie's own journey that slighted his glancing passage through the territories of an already existing U.S. empire. The intimate stories of individual conscience and family relations Willkie did tell about Puerto Rico—and its absence from his larger geopolitical concerns—mirrored the paradoxical manner in which many Americans both ignored and assumed the dependent status of the island and thus commonly overlooked their own investment in empire.

In the end, Willkie's worldwide adventure—the trip, his book, and the larger cultural moment it captured—signaled that his three popular geographies mapped not only an emerging globalism, but also the contested nature of American world understanding. The great popularity of Willkie's vision suggested that many Americans were open to a new, “smaller” world, but it also revealed that they were less prepared to accept an expansive worldliness that would dilute, rather than perpetuate and extend, American expansionary energy. In offering a global picture that obscured existing U.S. territorial empire, Willkie revealed how Americans were primed to accept and assume the contours of a new informal empire at the global scale.

Willkie's trip and the publication of One World capped a long-standing interest in international engagement. As a young lawyer and delegate to the 1924 Democratic national convention, Willkie tried to win domestic recognition for Wilson's ill-fated world organization, the League of Nations. Later, as chief executive of Commonwealth and Southern (a utilities holding company), he used congressional hearings on the Tennessee Valley Authority to make a name for himself as a plainspoken critic of New Deal business regulation. In 1939 a group of well-connected liberal northeast Republicans campaigned to enlist him as presidential candidate, betting that his internationalism would neutralize Republican anti-interventionists and win some liberals away from Roosevelt. Much to the chagrin of the conservatives, Willkie switched parties in early 1940 and won the nomination at the Republican convention after a prolonged floor fight. Throughout his losing campaign—which unfolded in the aftermath of the Nazi blitzkrieg across Western Europe that spring and summer—Willkie became ever more convinced that the United States could not go it alone as war spread across the world. After the election he burnished his internationalist credentials, visiting London during the Blitz and speaking out in favor of Lend-Lease. Willkie is remembered primarily for his role in helping to prepare Americans to enter World War II, but his true historical significance was greater than that: in the years after the campaign and before his untimely death, he encouraged his compatriots to embrace non-imperial relations with others around the globe.Footnote 15

Willkie's greatest opportunity to promote his vision of interdependent internationalism came in the summer of 1942. Three American journalists in Moscow, aware of how Willkie's London visit had boosted morale in Britain, sent a telegram suggesting he visit the besieged Soviet capital. Willkie convinced Roosevelt, who was grateful to his opponent for the support on Lend-Lease, to allow him to travel with government assistance. The trip made Willkie, already a famous figure in the United States, a sensation abroad as well. Between late August 1942, when he departed, and April 1943, when One World vaulted into the bestseller lists, millions of Americans followed his exploits and discovered his vision of a reconceived world. Reporters covered the trip in depth, allowing magazine and newspaper readers to track his journey from the Middle East to the Soviet Union to China. Upon his return Willkie himself penned articles for magazines, gave frequent radio speeches, and even contributed to a major Museum of Modern Art exhibit about the world at war. An estimated 36 million listeners heard his “Report to the People,” a radio address about the trip that he delivered on all the major networks in late October 1942. Millions also read One World; in fact, one estimate suggested that over four million people read the book in just the first few months after its release, making it the fastest selling book in American history. “One world” became one of the great slogans of the era, and while Willkie may not have invented it, the phrase became indelibly associated with him, his book, and his tripFootnote 16 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The cover of the newsprint edition of Wendell Willkie's One World (1943). Courtesy Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

The idea that the world was “one”—the basis of his universalist geography—rested on a conception of geopolitical space as a malleable artifact. Reflecting on his journey in One World, Willkie wrote that, “in the air, between stops, an airplane gives a modern traveler a chance to map in his mind the land he is flying over.”Footnote 17 The space of the world, Willkie implied, was not inert, but actively made. Its geography was not simply a matter of distance and physical features, a mere backdrop to human affairs. The world was instead dynamic, a product of human technologies—the way the airplane shrank space and time—and the capacity and propensity of the human imagination to “map” the relations between places and peoples. The map in Willkie's mind was thus an implicit symbol of the insight that, as Thongchai Winichakul puts it, any map is a “model for, rather than a model of” the physical and social features it claims to represent—a model that excludes just as it includes.Footnote 18

Just as important, however, Willkie's mental map was one that could be shared. As malleable features of human culture, the spatial relations such a “map” produced would have their own effects when an actor like Willkie took them up as geographic narratives and worked to shape popular understandings and drive political events. Willkie suggested that it was necessary not simply to know where places were on the map, but to know what the relations between them were and what they could be. He argued, in effect, that the space of the world could not only be observed but remade, and that Americans needed to take an active role in framing their own geography of the world, as well as America's role in the new world they were making.Footnote 19

In fact, he argued, the world was already being remade as its peoples were drawn closer together. “At the end of the last war,” he wrote in One World, “not a single plane had flown across the Atlantic. Today that ocean is a mere ribbon, with airplanes making regular scheduled flights. The Pacific is only a slightly wider ribbon in the ocean of the air, and Europe and Asia are at our very doorstep.” The airplane had made the air the new “ocean”—the medium of global travel and communication.Footnote 20

This transformation was social as well as physical. As the New York Times declared, upon Willkie's return from abroad, “there have been statesmen who met as many interesting people before, and there have been explorers who have traveled that far before, and there have been aviators who have flown that fast before, but I don't know whenever before in history so much has been packed over such a large space into such a short period of time.”Footnote 21 The pace and activity of Willkie's trip—he visited fourteen countries on three continents in seven weeks—revealed not only the physical fact of the collapsing space of the globe but also the sense that that collapse foretold a social transformation—a foreshortening of the distance between peoples as well as places.

Willkie's vision exemplified what historian Alan K. Henrikson has called “air-age globalism,” an imaginative paradigm for understanding new global connections prompted by air travel. President Roosevelt, a chief exponent of this ideal and a geography buff who once described himself as having a “map mind,” for instance used geographical terms to explain Allied war strategy in one of his most famous fireside chats, describing the war's “world-encircling battle lines” in order to draw “sound-pictures of the globe in the heads of a mass listenership.”Footnote 22

Roosevelt tapped into widespread interest in wartime geography, when mapmakers offered new kinds of maps reflecting how air travel and global battlefronts reorganized space. Both professional and popular cartographers began to offer world maps organized around the azimuthal equidistant, or polar, projection. Inspired by transpolar air travel, the polar projection positioned the map viewer above the northern hemisphere, with the North Pole and Arctic Ocean at the center of the map's two-dimensional plane and all the continents grouped around that central point. Lines of latitude rippled out in expanding circles, while the meridians radiated from that same central point. This vantage point communicated the impression of what historian Susan Schulten has called “globularity,” or the sense that the map mimicked the spherical properties of the earth itself. Like any projection the polar view distorted—it shrunk the southern hemisphere and stretched continents—but it revealed what the dominant Mercator projection—organized around the relations between continents and oceans at the equator—could not, namely that the air routes connecting the United States to the battle fronts in Europe and Asia had redrawn the map of the world. The scale of the planet had been reduced by speedy travel through the new “ocean of the air.” Now, as Willkie would write, Europe and Asia were at Americans’ “doorstep.”Footnote 23

The big mapmakers, like Rand-McNally and Hammond, added polar projections to their atlases in these years, but the most powerful renderings of this new “globular” perspective came from an amateur cartographer named Richard Edes Harrison, whose maps were published in Fortune and his bestselling 1944 atlas, Look at the World. Harrison created infographics depicting sections of the world seen from above, as if photographed from an aircraft at the edge of the atmosphere. These images, which conveyed the three-dimensional nature of the earth on the two dimensions of the page, showed the geographic relationships between critical war fronts as relays in the air across the curved arc of the globe. Controversial among professionals, the infographics’ disorienting perspectives and accompanying texts—which detailed the “approaches” to and from the United States, allied nations, and enemy territories—revealed the “flexible” properties of spatial relations. They suggested that the country was enmeshed in a series of vectored threats and opportunities, all of which demonstrated the irrevocable futility of trying to remain isolated from the world's conflicts. Harrison also produced a popular polar projection, prophetically titled “One World, One War,” for Fortune in 1942, which hung in many schoolrooms and homes during the war (Figure 2). These new world pictures made their way into popular imagery, proving especially useful for the airlines, which used simplified versions of polar projections to advertise the emerging global connections they would make possible after the warFootnote 24 (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Richard Edes Harrison's polar projection map “One World, One War,” 1942. Reproduced by permission of the estate of Richard Edes Harrison.

Figure 3. Consoldiated Airways print ad, 1943, featuring a polar projection map and a lesson in popular wartime geography. Courtesy of Lockheed Martin Corporation.

But perhaps no single figure represented this reworked world geography as fully as Willkie. In the summer of 1943, not long after One World appeared, the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) asked him to contribute to an exhibit called Airways to Peace: An Exhibition of Geography for the Future. On display was a series of images and objects that revealed the new air-age geography, including President Roosevelt's own “50-inch globe,” an eleven-foot polar projection showing “air routes of the future,” and the “Outside-In Globe,” a walk-in half sphere with a polar projection displayed on its inside walls in which visitors could stand and experience, all around them, the new relational space of the war.

Émigré designer Herbert Bayer—a veteran of the German Bauhaus school—gave the exhibit its immersive feel, encircling the objects with blown-up photographs, montages, and timelines. Visitors were supposed to feel themselves proceeding through a shifting panorama—a “surround,” Bayer called it—in which their individual perspective was central to the experience. They were not guided through the exhibit so much as provoked to make their own sense out of the array of globalist images, objects, and texts. Foregoing walls, Bayer used criss-crossing patterns of wires from ceiling to floor to delineate space and evoke the flight lines the exhibit surveyed. Enclosed yet expansive, it was a space that, like the exhibit's Outside-In Globe, helped visitors to bodily discover the flexible and relational geography of the new air age. The design evoked in gallery space the feeling of newly interconnected global space and its democratic possibilities. As MOMA exhibition director Monroe Wheeler exclaimed in the show's bulletin, “over our heads the airways have woven a web of intimacy, a new scene of mutual advantages, a world-brotherhood” (Figure 4).Footnote 25

Figure 4. The “Outside-In Globe” at the 1943 Museum of Modern Art exhibition, “Airways to Peace,” designed by Herbert Bayer and featuring text narration by Wendell Willkie. Gottscho-Schleisner collection, public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Willkie received top billing at the exhibit's entrance and contributed its primary explanatory text, which appeared on a series of floating panels throughout the gallery. His words framed the overall experience of Bayer's design. Drawing liberally on his speeches and One World, Willkie brought home the promise of the exhibit's form, delivering a lesson in the fungible nature of global spatial relations. Asking the exhibit's visitors to confront the “new geographical dimension” created by the “modern airplane,” he announced that “man must re-draw his world.” A series of “new realities” shaped both the war effort and the hope for “a world of peace and freedom” beyond the war. “A navigable ocean of air,” he wrote, “blankets the whole surface of the globe. There are no distant places any longer: the world is small and the world is one.”Footnote 26

Here and elsewhere Willkie stressed what was, for him, the key fact of the newly reordered world geography: its unified and universal shape. A world made “small” was also a world made “one.” The new map of the world—the model for reordered global relations—dispensed with the conventions of “natural and man-made geography” and eroded their divisive power. “We can stop thinking of the world today as a geographical map—splotches of color that stand only for nations and national possessions,” he said in a speech a few months later. “We can begin to think of the human beings who live within those splotches of color as living also within a larger map that marks a single world.”Footnote 27 This was the fundamental point of Willkie's lesson about the malleability of the world's spatial relations: as old divisions of national geography collapsed, a universal world space emerged.

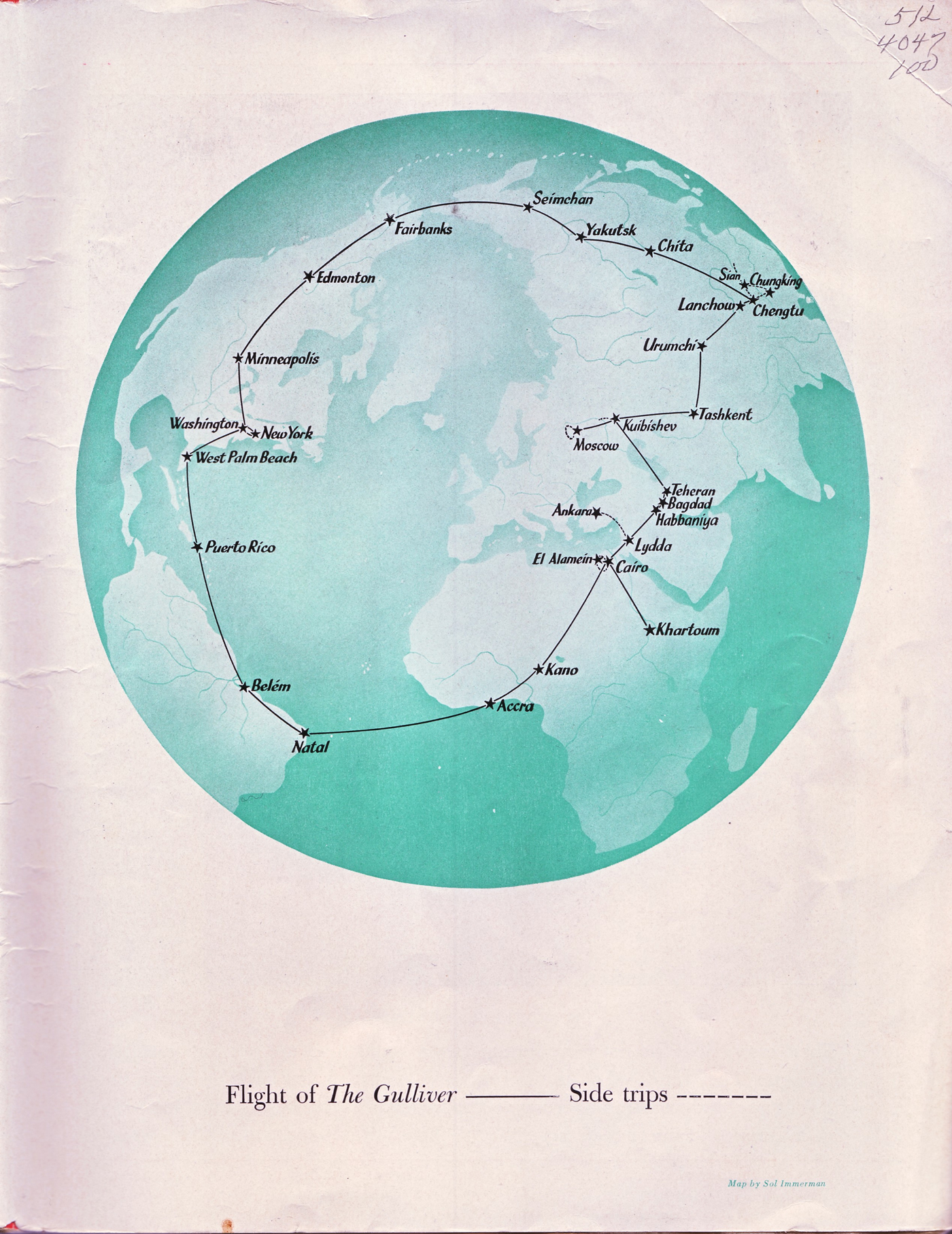

One World also offered a map of this transnational “single world.” The endpapers of the hardback edition and the back inside cover of the cheaper newsprint edition featured a modified polar projection. Called “Flight of the Gulliver,” the picture can be seen as the culmination of this new vision of universal globularity. Although a graphic image like Harrison's illustrated “approach” views, it showed the whole globe from on high rather than just a sliver of the earth, as Harrison's images often did. Combining Harrison's three-dimensional “globularity” with an improvisation on the polar projection, it placed the North Pole not at the center but rotated up slightly so that part of the southern hemisphere was visible as well. Harrison offered maps of war strategy, keen to reveal the relations between wartime nations and regions. Willkie's map did away with borders and those “splotches of color” that signified national collectivity. It showed instead a great blue-green spread of ocean and continents connected only by the vector of his voyage. The effect emphasized the global, universal nature of his trip and appeal. For Willkie, this new universal world space offered a clear political lesson: the “peace must be planned on a world basis,” making real the full interdependency that he hoped would dispel both isolation and empireFootnote 28 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. “Flight of the Gulliver.” Map insert from Wendell Willkie, One World (1943). Courtesy of Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

And yet, even as conceptual worldviews such as Willkie's imagined a new universalism, they also preserved something of the old nationalism, and lent themselves easily to an emerging tactical form of internationalism as well. Harrison's maps depicted nations in strategic relation to each other and stressed Americans’ vulnerability, or the fact that their nation's isolation had become an illusion unmasked by this radical new perspective. In fact, the new geography of interconnectivity—the polar projections, Roosevelt's globalism, Harrison's views—suggested that not only was the United States no longer sealed off by oceans, and thus not isolated, it was also poised to advance its own geopolitical interests in the emerging air age. MOMA exhibition director Monroe Wheeler acknowledged as much when he suggested that, in part, he aimed “to show how and why [American] fighting power … must be used all over the earth,” a comment that hinted at the dilemma of American influence that Willkie would try to get Americans to confront: if American might was to be used “all over the earth,” would it be for the “peace” of the MOMA exhibition's title or for the sake of its own perpetuation? “Air-age globalism,” in short, offered from one perspective a brief and a blueprint for seeing American power as the condition for the new global universality that Willkie heralded.Footnote 29 Indeed, all of these new mapping conventions would, as Timothy Barney has shown, become key ways to envision U.S. power in the Cold War era. As corporate and state institutions made new maps instruments of strategy for promoting the geopolitical space of American interests, the propsects for an open, universal space began to dissolve.Footnote 30

Willkie's universalist vision likewise depended on the centrality of the United States to world affairs. His journey, he often said, convinced him that the newly small world offered the United States a unique opportunity. If technology and war had shrunk space, only ideas, he argued in One World, could make up its connective fibers. The world had “become small not only on the map, but also in the minds of men,” he declared. Chief among the ideas “which millions and millions of men hold in common,” he continued, was “the mixture of respect and hope with which the world looks to this country.” The nation enjoyed an unprecedented “reservoir of good will.”Footnote 31 Just as the United States sat at the center of the new polar projection, it sat at the heart of the world's expectations. The “reservoir of good will,” Willkie said, had accrued to the United States as a result of the nation's professed support for the universal right to self-determination offered in the Atlantic Charter. The nation was in this sense exactly indispensable—it held the fate of all in its hands. The very rhetoric of “good will” that Willkie deployed suggested that the new universalist interdependence could be vouchsafed only by the presence and power of the United States to protect it.

Was Willkie's universalism simply a kind of proxy for empire, just a new way to extend American influence? “American geopolitical and economic imperatives,” the geographer Cindi Katz has argued, “have been smuggled in and authorized by lofty aspirations such as democracy and freedom, which conceal the geographic ambit of U.S. power.”Footnote 32 The universal abstractions of U.S. democracy, Katz and other critics have argued, assume a segmented spatial form, unevenly applied in order to satisfy the geopolitical imperatives of a world system dominated by an American empire that rules abroad not primarily by conquest but market share, economic dominance, and the extension of free trade and the “open door.” Was U.S. empire in its late-twentieth century phase, when it was so often cast as a dominion of liberty opposed to formal territorial colonialism, that much more effective at mobilizing and inspiring the benevolent forms of universalism deployed by idealists like Willkie? If so, Willkie's universal globularity—his “one world”—would appear little different from his contemporary—and political supporter—Henry Luce's “American Century” or other internationalist geographies that promised to install the United States as a successor to the European powers in the postwar era.Footnote 33

Alongside his universalist “one world,” however, Willkie offered a second imagined geography. Forced to avoid occupied Europe in late 1942, Willkie toured instead the Middle East, the Soviet Union, and China, charting a path that encouraged Americans to reorient their conceptions of the world away from Europe, which was the center of the imperial world system and the source of many American immigrant pasts. This itinerary challenged Americans to forego more traditional framing devices for the non-European world—exoticism, racism, or paternalism—for the possibilities of fraternity and cooperation, while also asking them to confront a host of questions that otherwise remained secondary in most of the public discussion of the war.

By these lights, “Flight of The Gulliver”—the map that decorated One World’s endpages—depicted not only the “single world,” but a new sense of its contents. During this “war of liberation” Willkie argued, perhaps ” the most significant fact” was “the awakening that is going on in the East.”Footnote 34 Responding to his trip, the columnist Anne O'Hare McCormick put it this way: the traveler recognized that “the world he knew—the world of the West—is small and self-centered compared to the immense and populous regions he traversed in his flight from the Nile to the Volga and across the great width of Asia.” He saw too that “the New World … is no longer here but there, in ancient nations being reborn in the profound convulsions of war and change.”Footnote 35 How would the United States receive that awakening?

Willkie argued that the territory he covered—he called it “that vast and ancient portion of the globe which stretches from North Africa around the eastern end of the world's oldest sea and up to Bagdad on the road to China”—was “more than a battleground.” It was “also a great social laboratory where ideas and loyalties are being tested.”Footnote 36 Chief among these tests would be the West's commitment to the freedom for which it claimed to fight in the East and other regions where it nevertheless continued to claim imperial prerogatives. Willkie's new geography, then, was one that contended with empire and its increasingly contested racial regimes, a space through which his fellow citizens could recognize the emerging freedom dreams of the East.

Willkie had long seen the war as “anti-imperial,” greeting with anticipation the promises of self-determination that Roosevelt and Winston Churchill delivered in the Atlantic Charter. In a 1942 speech to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) he argued, “we of the democratic nations are fighting an anti-imperialistic war. We covet no territory. We want no more power than is necessary to … maintain a world in which men can be free. We seek to liberate, not to enslave.”Footnote 37 Willkie's trip, however, would test his faith in the Allies’ commitment to a non-imperial future and convince him that if the United States wanted to live up to these lofty claims it would have to contest European colonialism abroad and dismantle racial segregation at home. Colonized peoples, Willkie understood, now demanded that the “war of liberation” be their liberation, too. Meanwhile, as his address to the NAACP suggested, Americans’ fitness for world power would be measured according to how well their nation aligned its intentions with demands for freedom, not just abroad but at home, too, where domestic racial injustices undermined the nation's credibility.

Willkie's conviction on these fronts irked some American officials, who feared angering British and French allies. He was little more than a well-connected tourist, the charge went; his sentimental and naïve idealism blinded him to the complexities of internal politics along his route. While Willkie sometimes saw what his hosts wanted him to see—particularly in the Soviet Union and China—this lack of particularity and complexity, ironically, allowed him to draw general lessons about freedom, empire, and race that domestic commentators or diplomats were less prepared to appreciate.Footnote 38

Willkie struck some as just another in a long line of American innocents abroad, but that innocence was turned to unconventional ends. Most white, middle-class Americans—the core of Willkie's constituency—came to the world with demands or expectations like many Americans before them. Since the late eighteenth century American tourists and other travelers—particularly to the Middle East and Asia—had looked for forms of Eastern exoticism that satisfied their own desires. “Orientana,” as historian Susan Nance calls it, supplied doses of fantasy and fancy that helped Americans to escape, transform, or revivify their experience of an increasingly rationalized capitalist society.Footnote 39 But by the twentieth century, their innocence increasingly took other guises. Many Americans continued to go abroad convinced of their own superiority and the rightness of mainstream American conceptions of liberty, individualism, and free enterprise. But by World War II, a time of urgent consensus building at home, more and more Americans imagined that it was national virtue, inclusiveness, and democracy that distinguished the United States from the rest of the world with its constant wars of empire. This sense of removed purity inspired both the desire to be a passive beacon of democracy—to stay free of overt entanglements and only “interfere by example,” as a New York Times editorial put it, commenting on Willkie's trip—and the opposite impulse: to go overseas with tutelary intent.Footnote 40 Either way, Americans brought their demands to the world.

Willkie, by contrast, challenged Americans to hear the East's demands. “I am only passing on an invitation which the peoples of the East have given us,” he wrote in the closing moments of One World. From the Middle East to China, Willkie made himself into a medium for the growing arguments that territorial arrangements of empire, mandate, or colony should be abandoned. He discovered, he wrote, a rising world, propelled by “a vast leaven which is now working deep in the lives of something more than half the human race.”Footnote 41

This conviction arose from the conversations, letters, editorials, and radio broadcasts that greeted him at each of his stops, many of which attacked European empire and hailed Willkie as a herald of freedom. For instance, an Egyptian student wrote to announce his solidarity: “We feel the same things, and our hearts beat on the same tune of liberty.” Their shared goal was “to fight this total war and to gain total peace.” That “total peace,” he implied, was impossible without a peace that guaranteed freedom for all.Footnote 42 Likewise, an anonymous Baghdadi argued that Allied “pledges” to the Arabs “leave no room for manipulation in the destiny of the Arab countries … which opposed the policy of imperialism for over twenty years and demanded her natural national rights for freedom and independence against great sacrifices.” Willkie, the writer hoped, would see to it that the Allies “leave nothing undone in helping the Arab nation to achieve her aspirations for freedom and independence in conformity with the Atlantic Charter.”Footnote 43

In Al-Hawadith, an Arabic newspaper in Baghdad, Salman Al-Shaikh Daoud, a prominent Iraqi journalist, similarly urged the traveler to help secure “the Arab's share of freedom and independence.” They had suffered since that last world war from “foreign ambition and imperialistic designs.” With the Atlantic Charter, though, their “full hopes” might be realized. “The Arab countries are for the Arabs,” Daoud continued, “and no people on earth have the right to claim our country.”Footnote 44 For these writers, and others like them, Willkie appeared as proof of Allied goodwill, and an affective—and effective—conduit for the most basic of political aspirations. Widely seen as Roosevelt's emissary—despite the fact that he spoke for himself and not the president—Willkie appeared to many as the embodiment of their Atlantic Charter hopes. As Edmund Stevens, an American journalist who followed Willkie in the Middle East, put it, “to the semicolonial nations of the Middle East, desiring emancipation above all other things, Willkie was the Four Freedoms taken out of the realm of the abstract and clothed in a rumpled blue suit.”Footnote 45

Greeted with this fervor, Willkie returned the favor, communicating to his audience the root concerns he encountered. “Men and women all over the world,” he wrote in One World, “are on the march, physically, intellectually, and spiritually.… Old fears no longer frighten them.… They are no longer willing to be Eastern slaves for Western profits. The big house on the hill surrounded by mud huts has lost its awesome charm.” For people everywhere, “in Africa, in the Middle East, throughout the Arab world, as well as in China and the whole Far East,” he wrote, “freedom means the orderly but scheduled abolition of the colonial system.”Footnote 46

Almost unique for someone at his level of American public life, Willkie embraced the demands of the peoples “on the march” across the Middle East and Asia. “Idealistically,” he wrote of European empire, “we must face the fact that the system is completely antipathetic to all the principles for which we claim we fight.”Footnote 47 In a widely transmitted speech that he gave during his stop in Chongqing, parts of which he reproduced in One World, he urged the United States government to make a statement that he imagined was “already clear … to most Americans: We believe this war must mean an end to the empire of nations over other nations.”Footnote 48

In Chongqing and again upon his return home, Willkie argued that the “peoples of the East” looked to the Atlantic Charter as a form of leverage, a tool by which the colonized could pry themselves loose from imperial domination. But he found this “deep draft of public opinion” moving ahead of Allied leaders. People he met everywhere wondered if the Atlantic Charter applied to “all the world.” They were troubled, if not surprised, by reports that Winston Churchill imagined its terms to be restricted to Europe and lands conquered by the Nazis. Soon after Willkie's return Roosevelt affirmed his belief that the Charter had meant to apply to the entire globe. Churchill, however, inflamed by Willkie's anti-imperial rhetoric, announced that he would not budge. “In case there should be any mistake about it in any quarter,” the Prime Minister declared in a notorious London speech, “we mean to hold our own. I have not become the King's First Minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire.” Willkie knew that this would be seen across the world for what it was—a “defense of the old imperialistic order.” The war and the demands of the colonized had issued a challenge to any form of internationalism that defended empire. The new conceptual geography sparked by the “renaissance of the East” reformulated what it meant “to think in global terms.” To reassert the privileges of imperial domination in this new world, Willkie said, would be “to accept Hitler's philosophy of a superior race” and to “return to the old white man's burden philosophy.”Footnote 49

By linking Nazism and fascism to racism and empire, Willkie issued a challenge not only to European imperialists, but also to Americans. In order to realize a “new society of independent nations” that recognized the interdependency of the world—his one world—Americans had to learn to live without their own closely held racial order. “The moral atmosphere in which the white race lives is changing,” he wrote late in One World. “It is changing not only in our attitude toward the people of the Far East. It is changing here at home.” The United States, he charged, had long “practiced inside our own boundaries something that amounts to race imperialism. The attitude of the white citizens of this country toward the Negroes has undeniably had some of the unlovely characteristics of an alien imperialism—a smug racial superiority, a willingness to exploit an unprotected people.”Footnote 50

Many knew the Atlantic Charter threatened European colonialism, but few white commentators recognized that it applied at home, too. “Our very proclamations of what we are fighting for,” he argued, “have rendered our own inequities self-evident. When we talk of freedom and opportunity for all nations, the mocking paradoxes in our own society become so clear they can no longer be ignored. If we want to talk about freedom, we must mean freedom for others as well as ourselves, and we must mean freedom for everyone inside our frontiers as well as outside.”Footnote 51 If the war provided opportunities for the African American freedom movement to question domestic and international color lines, Willkie was virtually alone as a white, national political figure with access to literally millions of American homes, in taking up that cause by labeling domestic segregation as “imperialism at home” and thus implicitly revealing it as based in the hierarchical visions of race and civilization that propped up empire abroad.Footnote 52

This double vision, of a United States confronted by challenges within and beyond its borders, asked Americans to embrace a subtle geography of reciprocity with the world. Willkie encouraged them to accept what we might call, following Charles Bright and Michael Geyer, “sovereignty in connectivity.”Footnote 53 American power and independence in the postwar world, Willkie argued, would require interdependence. This interdependence with the world was in turn dependent on the independence of “subject peoples” both at home and abroad. And so Americans’ independence, their freedom to act in the postwar world, required them to work to end colonialism and racism—both at home and abroad. “The way to make certain that we do recover our traditional American way of life with a rising standard of living for all,” Willkie declared in Chongqing, “is to create a world in which all men everywhere can be free.”Footnote 54 In powerful ways, Willkie's interdependent universalism called into question assumptions of American—or even “Western”—dominance and the hierarchies of race and civilization that supported such belief. The United States, in this imagined geography, relied on its attachment to the freedom of the peoples of the globe rather than simply the United States's promise to be the guarantor of that freedom.

What then of Willkie's take on U.S. empire itself? Several reviewers of One World, from Max Lerner in PM to Earl Browder in The Daily Worker to Walton Hamilton in The Progressive, took Willkie to task for failing to see what Lerner called “the imperialism of our corporations and cartels.” They appreciated his global vision, but thought him naïve about the character of American power. Browder particularly singled out the expansionist idealism of Willkie's supporter Henry Luce, while Lerner argued that on his trip Willkie had “judged most things as he went by an American yardstick.”Footnote 55 According to these critics, residual Americanism had left Willkie ill-equipped to appreciate the impact of U.S. power in its economic as well as territorial manifestations, at a time when the older settler, hemispheric, and Pacific empires the United States had erected were gradually giving way as the focus of American expansion to a new, global space of informal empire. The critique identified the way that Willkie, like so many Americans, mistook the nation's gradual retreat from foreign territorial conquest for an abandonment of empire altogether, and suggested that Willkie's “one world” obscured rather than revealed the great emerging force of the era: American power itself.Footnote 56

Of course, Willkie was on the record against territorial American empire. While in China he had decried the “treaty ports” through which Americans and Europeans had controlled the China trade in the nineteenth century, exploiting the so-called “Open Door.” He had also explicitly condemned “dollar diplomacy”—the practice in which American financial advisers left smaller nations with troubled economies in debt, dependent on U.S. capital and political advice, and sometimes occupied by a U.S. military force tasked with restoring “order” to a nation destabilized by U.S. financial intervention. He had criticized Roosevelt's “Good Neighbor” policy with Latin America as too vague, based on “pretty adjectives,” rather than forthright plans to move away from the Monroe Doctrine and toward trade policies designed to benefit the United States and its southern neighbors. He had long advocated “free trade,” but he was careful to say that he opposed “one country entering another with its superior economic power in order to dominate it politically.”Footnote 57

And yet, in One World American empire appeared as an afterthought. It was there, but largely as a figure of absence, a power that the United States had abjured or abandoned. “It has been a long while,” he wrote, “since the United States had any imperialistic designs toward the outside world.”Footnote 58 With the war, the United States had stored up a “vast reservoir of good will” in the world. Everywhere people believed that the United States did not fight “for profit, or loot, or territory, or mandatory power over the lives or the governments of other people.” The result was that “all the people of the earth know that we have no sinister designs upon them.”Footnote 59

Such sweeping assurance was due in part to a peculiar disjuncture between Willkie's itinerary and the story he told in One World. The book begins in Egypt and continues through the Middle East, the Soviet Union, and China, regions relatively untouched by American empire, while skirting Latin America and the Pacific, where public opinion about the United States was likely to be divided. His actual itinerary, however, featured stops in Puerto Rico, Brazil, and West Africa on his way to Egypt. This route was largely a matter of necessity—many flights used it to avoid occupied Europe—and the layovers were short, planned largely for refueling. But this sweep through the Southern Hemisphere represented a missed chance to measure the legacy of American power in Puerto Rico against European colonialism in the Middle East and Asia.Footnote 60

Willkie did, however, make one significant connection in Puerto Rico, a brief visit with his son Philip, who was stationed at a U.S. Navy base on the island. He spent only a few hours there—landing at Borinquen Air Field in the morning, taking in a sightseeing tour with his son on a U.S. military plane, and departing for Brazil and Africa that evening—and he did not even mention it in One World. Still, Willkie's momentary familial connection to one of the fundamental arrangements of American sway over Latin America suggests another angle from which to see Willkie's engagement with empire—as well as the third, obscured geography of his world vision.

Recent accounts of the culture of U.S. empire have suggested that imperial power is maintained and extended through forms of intimacy—both discursive and actual—that are imagined to bring colonizer and colonized into personalized, human relations of affinity and cooperation across unequal power divides. These cultures of intimacy were deployed both to create and shore up the racial differences and gender hierarchies upon which that imperial power fundamentally rested. This is true of all imperial relations, but it has had particular importance for stories of U.S. empire due to the nation's purported anti-imperial ideology.Footnote 61

The paradoxical effect of this ideology for Puerto Rico was a particular state of exception expressed in ambiguous formal status. In the 1901 decision Downes v. Bidwell, the most important of the “insular cases” that decided the fate of U.S. possessions abroad, Supreme Court Justice Edward Douglass White labeled the island “foreign in a domestic sense.” Puerto Rico (along with the Philippines), the Supreme Court ruled, was a possession of the United States but not incorporated into the Union. Puerto Ricans were granted voting rights and some other individual Constitutional rights, and eventually U.S. citizenship in 1917, but in matters of trade, this meant that Congress could enact tariffs on Puerto Rican imports that were normally imposed on foreign goods. Ever since, two of Puerto Rico's historians argue, the island has been a part of the United States's “orbit of nonincorporation.” Held as a territory that the United States will not quite admit is a colony, it has nonetheless never been granted full statehood.Footnote 62

In Willkie's narrative, Puerto Rico was just that: “foreign in a domestic sense.” Somewhere between home and abroad, it was at once familiar and ignored, intimate and overlooked, a blurry spot on his mental map. His son served in the military that was, for many Puerto Ricans, an occupying power, but for him the paternal regard in which he held his son was analogous to the form of benign protectoracy in which he and many other Americans imagined they held Puerto Rico. As part of the only-partially-acknowledged American empire, the island appeared simply part of his own family life, not an episode in the great geopolitical drama of empire and freedom his travels were intended to reveal. Furthermore, if Willkie showcased the particular culture of imperial intimacy in which Puerto Rico rested, these “tense and tender ties” (to borrow Ann Laura Stoler's formulation) also worked to keep Willkie's full history with Puerto Rico outside the narrative.Footnote 63

This was not, in fact, Willkie's first visit to Puerto Rico. He had spent a summer there in 1915, working, along with his brother, as a chemist in a lab run by the U.S.-owned Fajardo Sugar Company. One of four American companies that dominated the island's major export industry, Fajardo directly benefitted from the tariff regime. Over the first two decades of the twentieth century Congress authorized low tariff barriers to Puerto Rican sugar (and high rates for sugars imported from outside the United States) and a system of land and property taxes that gave mainland corporations an advantage over indigenous smallholders. This helped big companies like Fajardo to invest in new production facilities and pursue vertical integration of the growing and refining process. It also displaced smaller farmers, many of whom were forced into wage-work on the new sugar plantations.Footnote 64

Demand for cheap sugar boomed on the mainland. The colonial product emerged as the great emblem of industrial civilization, speeding up work tempos, sweetening leisure time, and helping industrialize food production, while in the islands it promised to bring efficiency, modern work discipline, and uplift to a racialized population deemed as yet unfit for self-government. The sweetness of sugar, April Merleaux has argued, quickened the process of commodity fetishism, veiling with new forms of pleasure and adrenaline the inequalities and brutalities of the corporate plantation labor regime needed to extract processed sugar from cane.Footnote 65

For Puerto Ricans, however, the new world of sugar was a less giddy rush. Consolidation in the industry brought new wealth to the islands, along with urbanization and professionalization in the cities, but it tended to reduce indigenous food production, break up small farms, intensify traditional social hierarchies, and create a growing class of landless workers with stagnant wages. The result was a generation of political upheaval and labor organizing, culminating in a series of sugar worker strikes as World War I approached. In 1915, just as the young Willkie arrived, 17,000 cane workers struck, martial law was declared, and at least seven workers died.Footnote 66

More than twenty-five years later, on his return to Puerto Rico, Willkie remembered little of the events of the summer of 1915, save the extreme poverty surrounding Fajardo's mill, and one brutal incident. Out on horseback with a plantation manager, Willkie saw a destitute cane worker—a fugitive, likely, hiding out in the aftermath of the cane strike—stumble out of the brush by the side of the path. The manager, Willkie remembered, slashed at the man with his cane knife, nearly severing his arm at the shoulder. Already prone to sympathy for workers—his father was a liberal labor lawyer—Willkie was horrified. He would always remember that moment as the birth of his social conscience. It was, he later said, the reason why he was such an unorthodox social thinker for a wealthy businessman. The memory “kept him from thinking like a typical American millionaire,” his friend Joseph Barnes remarked.Footnote 67

When Willkie returned in 1942, another cane strike had recently concluded. Two workers had been killed, and food shortages caused by wartime disruptions in imports increased the suffering, but this time the island's government, headed by the reformer Luis Muñoz Marín, who had allied himself with Willkie's New Deal rivals, helped the cane unions win higher wages. Muñoz Marín and the U.S. governor appointed by Roosevelt, Rexford Tugwell, had laid out an ambitious land reform program to reduce the power of the big landowners and sugar companies and return some land to workers—called agregados—who by tradition lived on property owned by their bosses. Hoping to secure more reforms, Muñoz Marín avoided demanding independence and pledged support for the U.S. war effort in the name of the Atlantic Charter, while Tugwell hoped to win Puerto Rican compliance for another great infrastructural undertaking on the island: a military base-building boom.Footnote 68

The U.S. Navy had long regarded Puerto Rico as a strategic site on the sea lanes approaching the Panama Canal, but disastrous Nazi submarine attacks on shipping in the South Atlantic pushed the military to invest in a new series of naval and air bases on the island. Construction for the new facilities was ongoing in 1942, as were the hardships it caused. Erecting the “Gibraltar of the Caribbean”—as one U.S. official called it, in homage to British strategic hegemony over the Mediterranean—required a program of property takings that would undo some of the good effects of the planned land reform and usher in results not unlike that of the sugar consolidation a generation earlier. The military took land by eminent domain, paying landowners fixed prices but evicting the agregados, who, by the traditions of U.S. property law, were seen as merely “squatters.” At Punta Borinquen alone, the U.S. military took 1,877 cuerdas (about 1,823 acres) in September 1939, evicting the residents of two small rural communities. Two thousand Works Progress Administration workers arrived from the mainland to begin work on the Borinquen air base, which would serve as a vital link in the cross-Atlantic air route that Willkie followed several years later.Footnote 69

Willkie arrived in 1942 at a hinge moment in Puerto Rican history. Prosperity ushered in by wartime investment would partially free the territory from dependence on the sugar industry that had sponsored Willkie's previous youthful visit, but it would cement the sway of another institution of U.S. empire—the U.S. military, the very power that made possible his second visit, and which would lead to several generations of conflict on the island over claims to land and sovereignty. For Willkie, Puerto Rico played a formative role in his coming of age story. The episode with the cane worker revealed the casual violence and racial discrimination enforcing the poverty and misery of plantation life. The incident spurred his sympathy. But as a minor functionary in the larger imperial system the sugar companies had erected, the memory of it did not push him to explicitly critique the particular political and military arrangements that kept that economic system in place. As he and his son flew over the island almost thirty years later, he made no public note of the consequential impact of the two American institutions that underwrote his visits. Puerto Rico never became an explicit ingredient in the anti-imperial geography he mapped in One World.

Of course, by the time of his trip Willkie was an anti-imperialist. And he was aware of the American territorial empire. But like many of his fellow Americans at mid-century he believed that it was disappearing. The 1934 U.S. guarantee of eventual independence for the Philippines convinced him that the United States was moving toward the end of its ill-fitting turn as an imperial power. He admitted in One World that the United States had “not yet promised complete freedom to all the peoples in the West Indies for whom we have assumed responsibility,” but those promises seemed inevitable.Footnote 70 It may have been the imperatives of scheduling, or even his assumption that freedom for Puerto Rico was inevitable, that sidetracked him in 1942 from following up on the scenes of exploitation he had witnessed in 1915. But his benign formulation also revealed that he believed that American power over Puerto Rico had little bearing on the United States's standing as the repository of the world's “good will.”

With his “tender ties” to his son mirroring the paternalist “responsibility” the United States showed for Puerto Rico, Willkie did not reveal how the linked forces of race and empire presented a domestic as well as international challenge. He could see how domestic racial inequality should be condemned in the same terms as European imperialism—even when it happened in a United States territory like Puerto Rico. That was a matter of individual conscience, of the sort his Puerto Rican story primed him to develop. But he could not quite see what one of his allies, John Robert Badger, the “World Views” columnist for the African American newspaper The Chicago Defender, could: Puerto Rico was to the United States as Ireland or India was to Britain. As long as “Puerto Rico fails to obtain self-rule,” Badger wrote in 1942, “the United States will be regarded with suspicion by the world's colonial and semi-colonial peoples.” The island's status fed the “suspicion and hatred of Yankee imperialism which has been Hitler's most potent ally.” Badger, picking up on Willkie's popular language, warned that Puerto Rico was the “main test” of the nation's commitment, “for, as Wendell Willkie said, our reservoir of good will in Europe and Asia is leaking.”Footnote 71

Willkie's ties to Puerto Rico led him into a paradox. Like the island itself in U.S. political culture, they were both closely held and taken for granted, a source of both awakened conscience and assumed domestic tranquility that encouraged his conscience to turn away from explicit critique of American empire. His relation to the island conflated several registers of affective attachment—the domestic, the familial, the national—that combined to suggest that places like Puerto Rico could not occupy the role in his anti-imperial global geography that Badger argued they should. In that sense, Willkie's story of intimacy encouraged a view of Puerto Rico familiar to many Americans. Like the sweet sugar extracted from the fields Willkie knew in 1915, the story both normalized and naturalized the existence and inevitable inequality of empire, leaving Puerto Rico's existence as a territory paradoxically acceptable and invisible, simultaneously ignored and simply assumed as an American ward.

This geography of empire obscured assured his audience that American empire was receding from the world. It therefore disguised Americans’ ongoing innovations in imperial power at just the moment when the dispersed empire of economic influence that the United States would perfect in the postwar era had begun to reshape the European imperial system that Willkie hoped to undermine. Willkie's ties to Puerto Rico helped to protect, for him and his audience, a particular kind of innocence from full consideration of American expansionary energies—a power that would endanger the interdependent internationalism he so favored.

The Willkie moment represents an underappreciated episode in the history of “globalization.” Seizing the wartime opportunity to travel the world, Willkie prodded many Americans into a renewed era of planetary awareness, one that echoed and prefigured other episodes of globalization in human history: the age of “discovery” and encounter across the oceans in the early modern period; the high-water years of industrial capitalism, nationalism, migration, and Western empire in the nineteenth century; or our own post–Cold War, postcolonial years of intensified technological and financial speed-up and interdependence, migration, and “deterritorialization” of capital.Footnote 72 Willkie's work might have suggested to some Americans that they had long been enmeshed in the world—even if he himself did not make the link to past eras of global connection explicit—but he and other internationalists believed that there was something fundamentally new, or newly intense, about their moment of interrelation. As the foremost proponent of wartime popular internationalism, and an advocate watched by millions, Willkie announced not merely a new round of contact among disparate societies, but also an era in which human spatial imagination had to “map” a planet whole and one. The territorially un-bounded maps in Willkie's mind represented a new form of global connection, one that began to eclipse the very state-based internationalism with which he was associated and prefigured our current concept of a world remade by “transnationalism.”Footnote 73

Willkie's “one world” linked two overlapping kinds of spatial experience—one marked by greater interdependence between nations and their distinctive peoples (think, again, of the founding of the United Nations in 1945, a few years after Willkie's trip and book) and the other distinguished by accumulating “instruments of international interaction,” to use Lynn Hunt's phrase, which intensified connections that transcended national borders. Some would say the time of “air-age globalism” marked no new moment in planetary relations since it arrived in the wake of the Great Depression, a time of decelerating economic connectivity. And yet, Willkie clearly saw, and encouraged millions of others to see, that the expansive stakes of the moment pressed upon Americans heightened dilemmas of global relation that their national politics could not yet confront. The airplane and the world war, as well as the increasingly dispersed networks of telegraphs, radio waves, and movie screens in which Willkie moved, were the “instruments” of a remade world picture—one in which the inter-national and the un-bounded global were entwined on a planet that was coming to be imagined, in a proto-environmental sense, as one whole earth.Footnote 74

And yet Willkie went further still. Unlike many other Western globalists, Willkie's round-the-world narrative cast the rediscovered world as already shaped by empire. He depicted the universalist “one world” as not achieved, but precarious, realizable only by way of an interdependency that recognized what Edward Said has termed the “separate sovereignty” of those peoples subject to the power of empire and the racial hierarchies accompanying and bolstering it.Footnote 75 Willkie's worldwide thinking was prescient not only because it showed how the isolationist versus internationalist frame that structured American domestic politics obscured this longer history, but for the way that it heralded the struggles already underway in the dawning age of decolonization.

But the ambiguity at the heart of Willkie's treatment of American empire itself suggested that many Americans would struggle to recognize those decolonization campaigns as battles in which they, too, were implicated. For while Willkie's mind-map revealed the constitutive power of empire in the making of global connectivity, it remained imprecise about the United States's evolving role in shaping the empire-made world. Despite his own best intentions, Willkie's conceptual geography did in effect serve to “conceal the geographic ambit of U.S. power”—to return to Cindi Katz's formulation—from the vast popular audience he attracted. Even as Willkie objected to some of the particular effects and policies of that “ambit” as they happened, his imagined geography revealed how the evolution and transformation of an American empire could remain obscure for Americans themselves. The actual places of American empire in Willkie's narratives are not so much ignored, but, like Puerto Rico—swaddled as it was in ties of familial intimacy—simply naturalized, thereby rendering the modes of territorial empire-making Americans had already practiced as disappearing pasts, while simultaneously obscuring the emergence of a U.S. imperial “ambit” whose geography was coming to be mapped not primarily in territory, but in global economic, military, and cultural power. This new imperial reach shared the universalism that Willkie heralded, but it was one based in the practice of establishing a worldwide prospect for the exercise of American influence.

Would Willkie's urgent call for interdependence eventually have placed him and his audience directly athwart the advance of this emerging form of American empire? Perhaps. At his most expansive Willkie offered a vision of an alternative global future, one that hoped to head off competition between the Soviet Union and the United States and recognized the possibilities offered by the anti-colonial energies collecting in what would later come to be called the Third World. And yet the very fact that Willkie, the most popular of American internationalists, could not untangle the dilemmas of U.S. imperial culture suggested how difficult it was—and would continue to be beyond Willkie's own sudden death in 1944—for many Americans to recognize and confront this most chimerical and persistent mode of national power and the threats it posed to the more open, democratic “one world” Willkie himself imagined.