Introduction

This article analyses the construction of monumental Muslim tombs in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century South Asia, asking how stoneworkers adapted their labouring practices in contexts of contested religious authority and emerging forms of technical oversight. In Muslim-led ‘native’ or ‘princely’ states, quasi-autonomous polities under colonial oversight, monumental-tomb patrons borrowed earlier practices of Indo-Islamic stonework to articulate dynastic authority. These patrons also employed new classes of technically educated intermediaries—increasingly drawn from British Indian technical schools, rather than local master craftsmen—to oversee major monumental-tomb projects. Stoneworkers incorporated the technologies and materials preferred by institutionally educated overseers into tomb-construction projects. Although stoneworkers rapidly adapted to new technical demands, the labouring identities that they fashioned through work at these sites increasingly diverged from the role imagined for them by their overseers and patrons.

Patrons, technical overseers, and workers all engaged with monumental-tomb construction as a means of fashioning or articulating their own religious, professional, or social positionalities. The article therefore centres the tensions between divergent class understandings of the role of the monumental Muslim tomb in colonial-era India. In part due to the homogenizing impacts of technical education, intermediary understandings of monumental tombs increasingly aligned with state narratives. State elites and middle-class intermediaries positioned new technologies as capable of improving monumental-tomb construction, but viewed them as largely detached from the religious meanings and practices reflected by the tomb. Stoneworkers, on the other hand, engaged with narratives that positioned technological and material change not as the ‘modernization’ of labour, but as reflective of their own religious and cultural practices. In order to study the contradictions and overlaps between these interpretations of tomb construction, the article turns first to systems of elite tomb patronage in native states. It then analyses shifts in the educational systems of technical intermediaries, before finally asking how stoneworkers fashioned distinct labouring, religious, and social identities through their employment on monumental-tomb projects.

Patronage and the ideals of tomb construction in Muslim-led native states

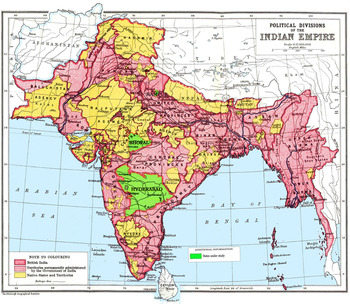

In the late nineteenth century, courtly patrons across Hyderabad, Bhopal, and Rampur (Figure 1) characterized tomb construction and repair as demonstrative of renewed Muslim authority. At the same time, they argued that monumental construction could be improved through technologies and materials associated with emerging colonial industrial ‘modernity’.Footnote 1 State administrators expressed this ‘modernity’ through references to the ‘development’ (taraqqī) of ‘industry’ (ṣanʿat) and the training of technical overseers in ‘new sciences’ (ʿulūm-i jadīd) and ‘new education’ (taʿlīm-i jadīd) represented by colonial institutions.Footnote 2 For patrons in Bhopal, Hyderabad, and Rampur, the technical practice of ‘modernity’ was divorced from the Muslim heritage and authority represented by tombs, but could nonetheless be used to improve their physical form. To this end, they engaged what Faisal Devji framed as the apologetics of Muslim debates on ‘modernity’, which allowed conceptual room for Muslims to ‘accommodate’ modernizing discourses without necessitating systematic transformations of Islam.Footnote 3 But, as we shall see, stoneworker understandings of technological adaptation at tombs belied not only these apologetics, but also narratives of technical ‘modernity’ themselves.

Figure 1. Rampur, Bhopal, and Hyderabad highlighted on a 1916 map of the political division of India, including the divisions between British Indian and native state territories. Source: R. V. Russell and Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, vol. 1 (London: MacMillan and Co., 1916), front piece, edited to highlight Rampur, Hyderabad, and Bhopal by Lamya Mohsin Khan.

Hyderabadi, Bhopali, and Rampuri courtly patrons all sought to assert regional Islamic authority and to portray technical parity with British India through monumental-tomb construction. Nonetheless, the differences in tomb positionality between the three states allow us to analyse the relevance of localized religious, political, and social movements to the work of tomb construction. In Rampur, elites focused on developing new regional sites for pilgrimage and religious mourning. In Bhopal, state nobles emphasized parallels with Mughal monuments to demonstrate political legitimacy. And, in Hyderabad, members of the state bureaucracy and court used tomb repair and reconstruction to articulate new claims on regional Muslim pasts. These projects overlapped across states, but preferred styles of construction and technical expectations placed on workers were informed by the localized political concerns of patrons.

In endowing tombs and shrines, native state elites positioned themselves within long traditions of Muslim-tomb patronage across the subcontinent. From at least the thirteenth century CE, Muslim rulers in South Asia used monumental-tomb construction to demonstrate political and religious authority. Rulers ranging from the Delhi Sultanate's Shams al-Dīn Iltutmish (r. 1211–36) to Ibrāhīm Qulī Quṭb Shāhī of Golkonda (r. 1550–80) to the last Mughal emperor, Bahādur Shāh II (r. 1837–57) used monumental tombs to make physical claims to regional authority and dynastic historicity.Footnote 4 Likewise, over the course of the nearly 700 years of varying forms of Muslim dynastic rule on the Indian subcontinent, rulers patronized the construction of tomb shrines for members of Sufi lineages.Footnote 5 Indian Muslim rulers relied on their relationships with prominent regional Sufi lineages to build and articulate dynastic authority. Reflecting the integration of the patronage of Sufi shrines and the construction of noble tombs, Bahādur Shāh II constructed his palace and intended burial grounds adjacent to the dargāh (tomb shrine) of Quṭb al-Dīn Bakhtīarī in Delhi's Mehrauli neighbourhood. In a moment in which his political power was circumscribed, the site allowed him to borrow from what Catherine Asher termed the ‘inherent authority’ of the dargāh.Footnote 6

The Mughal empire was not formally disestablished until 1857 but, by the mid-eighteenth century, several prominent regions of the subcontinent formerly under its direct rule were led by autonomous local dynasties. Throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, these Mughal ‘successor states’ were increasingly subject to colonial oversight by the British East India Company.Footnote 7 Nonetheless, in prominent states like Hyderabad and Awadh, Muslim leaders continued to use tomb construction to demonstrate political autonomy, piety, and their relationship with prominent Sufi lineages. This practice also continued in the subcontinent's remaining Muslim-led native states following the consolidation of the British Raj in the wake of the Uprising of 1857.Footnote 8

For instance, Nile Green has argued that, in Hyderabad, members of the Āṣaf Jāhī dynasty (r. 1724–1948) sought at various points to construct a ‘saintly heritage’ for the state, providing patronage to new Sufi shrines to demonstrate the state's Indo-Islamic authority.Footnote 9 Hyderabad city, the dynasty's capital from 1763, lacked the authority wrought by association with major Sufi pilgrimage sites, leading state elites to endow new shrines to demonstrate the city's regional prestige.Footnote 10 Rampur city, the capital of the only remaining Muslim-led state in the populous North Indian region of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh after 1858, similarly lacked a long history of Sufi shrine pilgrimage. In Rampur, the impulse to create a ‘saintly heritage’ was if anything more intense and more central to state construction into the twentieth century, because it allowed a comparatively minor regional dynasty to claim religious and political influence.

Reflecting the state's engagement with this construction of saintly heritage, the Rampuri Nawab Kalb ‘Alī Khān (r. 1865–87) set aside funds to construct tombs for his own spiritual advisers.Footnote 11 According to an early twentieth-century Urdu-language history of the state, Kalb ‘Alī Khān ‘brought together the greatest craftspeople and workers of the area to begin the construction of new buildings in Rampur’.Footnote 12 Moreover, although Kalb ‘Alī Khān apparently embraced the views of his primarily Sunnī Naqshbandī Sufi religious advisers, for much of its history, Rampur was one of a few Shīʿa-led states in colonial India. Even under Kalb ‘Alī Khān, state construction reflected the attempts of members of the Rampuri court to portray the state as a site of continuity for North India Shīʿa Muslims, many of whom migrated to the state from the formerly Shīʿa-led Awadh after the British annexation of that state in 1856. Kalb ‘Alī Khān's court employed stoneworkers not only to build tombs for Sufi saints, but also to construct a new central imāmbāṛā (a site for Shīʿa mourning and commemoration) and a shrine for a relic of ‘Alī, the Prophet Muhammad's son-in-law, seen as his rightful successor by Shīʿa Muslims.

Rampur's longest-reigning Nawab, Ḥāmid ‘Alī Khān (r. 1889–1930), was more directly informed by European architectural models, employing a British chief engineer and patronizing buildings that borrowed stylistically from British Indian models.Footnote 13 His reforms to Rampuri architecture shared much in common with those in states like Mysore and Jaipur, where Hindu princes also built religiously symbolic dynastic monuments, made claims on the Mughal past, and borrowed new British Indian styles.Footnote 14 His chief engineer, W. C. Wright, was retired from British Indian service and was responsible for the construction of a new city gate, a new jail, a new canal system, and a new hospital, among many other notable local structures. Most famously, he designed the Ḥāmid Manzil, Rampur's central palace complex, which, since 1957, has housed the city's renowned Raza Library.Footnote 15

Wright's projects in Rampur largely derived from architectural styles preferred by contemporary architects in British India.Footnote 16 Thomas Metcalf has shown that, by the late nineteenth century, British engineers like Wright had shifted from ‘transplanting’ European modes of architecture to evolving new styles of building and design unique to South Asia.Footnote 17 In their appointments in native states, they adapted stylistic practices meant to evoke both an imagined Indian past and the power and influence of the British empire.Footnote 18 But, even with the influence of Wright and other British Indian engineers, a major source of work for stoneworkers during Ḥāmid ‘Alī Khān's reign was the maintenance and construction of monumental tombs.Footnote 19 By the early twentieth century, many workers moved fluidly between European-modelled public-works projects and religious architecture, and, as we shall see, technical overseers increasingly expected them to apply techniques used in public-works projects to monumental tombs.

Native state patrons also used tomb construction to demonstrate dynastic legitimacy and visually connect themselves to earlier regional dynasties. In Bhopal and Rampur, unlike in Hyderabad, the local dynasty lacked a historical connection to the defunct Mughal state, the most recent precolonial large-scale Muslim power on the subcontinent. Members of Hyderabad's Āṣaf Jāhī dynasty were first appointed by the Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar (r. 1713–19) and maintained an ostensible association with the empire even as they established themselves as the primary local authority. In contrast, although the Bhopali dynasty was established in 1709, its members were descended from Afghan mercenaries, not Mughal-appointed nobles.Footnote 20 From 1819 to 1926, Bhopal also held the distinction of being one of the only female-led native states in India.Footnote 21 The Islamic acceptability of women's rule was affirmed by qaz̤īs (judges) in Bhopal, but Indian Muslim writers occasionally remarked on their gender as a sign of weakness in regional Muslim rule.Footnote 22 Bhopali elites were conscious of their perceived lack of inherent regional authority and therefore used tomb construction to claim connections with earlier South Asian dynasties. To build state legitimacy, state elites developed what Barbara Metcalf termed ‘Mughal revival’ architecture under the Nawab Shāh Jahān Begum (r. 1868–1901).Footnote 23

Shāh Jahān Begum seems to have drawn inspiration for her urban policy from her namesake, the Mughal emperor Shāh Jahān (r. 1628–58), considered a great patron of urban architecture and the force responsible for the opulence of Mughal Shahjahanabad. The Tāj ul-Masājid (today the largest mosque in India), the ornate Mūtī Masjid (Pearl Mosque), and her Tāj Mahāl palace all reflected the Bhopali Mughal revival.Footnote 24 To this end, Bhopali architecture, while meant to evoke the religious authority of a women-led monarchy, was also clearly in conversation with contemporaneous trends in British India. In adapting a generalized Indo-Islamic style that borrowed primarily from the Mughal heartlands of North India, rather than regional, Central Indian styles, Bhopali elites mirrored the homogenizing discourses of British Indian studies of Indo-Islamic architecture. Termed ‘Saracenic’ by the Scottish architectural historian James Fergusson, in European narratives of the mid-nineteenth century, Indo-Islamic architecture was meant to exist in contrast with an indigenous ‘Hindu’ style.Footnote 25 This conceptualization of Islamic architecture in British India likely contributed to Bhopali elites’ preference for a style evocative of Mughal Delhi and Agra. Borrowing between British India and Bhopal extended in both directions, with British Indian officers of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) deputed to the state while planning New Delhi to study contemporary ‘authentic’ Indian architecture.Footnote 26

Even as they engaged in Mughal-modelled-tomb construction, Bhopali elites worked closely with so-called reformist movements that responded to the decline of Muslim political power in British India, including several that debated the permissibility of monumental tombs. The tomb of Ṣiddīq Ḥasan Khān (d. 1890), a prominent religious intellectual who married the ruling Nawab Sultan Jahān Begum of Bhopal in 1871, is a large white-marble complex featuring extensive carved marble jālī (a style of perforated screen) work (Figure 2). It is today surrounded by signs in Hindi and Urdu that identify it as the mazār-i sharīf (exalted shrine) of Nawab Ṣiddīq Ḥasan Khān.Footnote 27 The appearance of the tomb belies the fact that it was constructed for a reformist intellectual who saw tomb-based worship as bid‘ah (innovation) and unlawful, and discouraged monumental tombs.Footnote 28 The trend among some Sunni Muslim reformers to reject large tomb and shrine complexes was rooted in a revaluation of popular Islamic practices among Indian Muslim intellectuals. By the mid-nineteenth century, members of reformist movements challenged the popular practices of Indian Muslims as insufficiently rooted in early Islamic teaching, criticizing perceived innovations at Sufi shrines and tombs.Footnote 29 These reformists argued that prayers performed at tombs were addressed to the interred, rather than God himself, undermining the monotheistic nature of Islamic worship. In Bhopal, as suggested by Ṣiddīq Ḥasan's tomb, the construction of monumental tombs continued largely unabated even where reformist critiques dominated, because the elites of these states were equally concerned with establishing post-Mughal symbols of authority. We shall see, however, that the spread of reformist ideas shaped the work available to stoneworkers created small-scale tombs at local cemeteries.

Figure 2. Despite Ṣiddīq Ḥasan Khān's ambivalent attitude towards monumental-tomb construction, his tomb in Bhopal is a white-marble mausoleum replete with jālī work.

As in Bhopal and Rampur, tomb patrons in Hyderabad sought to establish new sites of pilgrimage and claim the Mughal past, and they too often navigated reformist ideologies. However, they also placed a unique emphasis on the reconstruction of tombs of earlier dynasties to assert localized Indo-Islamic authority. In 1870, Mīr Turāb ‘Alī Khān, Sālār Jung I, the prime minister of Hyderabad from 1853 to 1883, set aside state funds to make repairs to domed tombs of the Quṭb Shāhī dynasty (r. 1518–1687).Footnote 30 Hyderabadi stoneworkers and masons applied new plaster, reconstructed bases and domes, and refurbished marble inlays on several of the tombs.Footnote 31 Through this work, Hyderabadi elites like Sālār Jung patronized physical manifestations of state claims to an Indo-Islamic heritage that cut across sectarian and regional lines.

Through the reconstruction of the tombs of previous Shīʿa dynasties, stonework was incorporated into a discourse of Islamic ecumenicism that characterized elite Hyderabadi attempts to position the state as a Muslim-led space surrounded by British territory. By reconstructing Quṭb Shāhī and other Shīʿa tombs, Hyderabadi state elites of the largely Sunnī Āṣaf Jāhī court made physical claims that their state represented a regional haven for Muslims from diverse sectarian backgrounds.Footnote 32 They also used the restoration of these tombs to develop a public association with a pre-Mughal Deccani past: the Āṣaf Jāhī Nizams were descended from Mughal appointees and their ancestors had participated in the Mughal conquest of the Deccan.Footnote 33 In doing so, they defeated the Quṭb Shāhī dynasty, which had developed a strong local association with the Deccan despite its Iranian descent. By restoring the Quṭb Shāhī tombs (Figure 3), Nizami elites claimed the Deccani past, seeking to paper over historical differences between dynasties to integrate the native state into a narrative of unbroken Muslim rule in the Deccan.Footnote 34

Figure 3. As of 2019, the Quṭb Shāhī tombs were again under restoration, with conservators seeking to undo damage done by plasters used in earlier repairs.

Hyderabadi repairs to the Quṭb Shāhī tombs occurred roughly contemporaneously with the rise of major conservation projects in British-administered India, but Hyderabadi discourses surrounding tomb reconstruction differed significantly from British depictions of tomb repair. British depictions of the architecture of past dynasties contrasted the perceived excellence of precolonial Islamic architecture with narrative of decline that highlighted the supposed failure of contemporary Indians to build or appreciate structures of worth.Footnote 35 British writers also compared Indian stoneworkers negatively to their predecessors, with portrayals of the supposed decline in artisan skill mirroring the discourse of urban decline that characterized colonial writing on Indo-Islamic monuments.Footnote 36 When British administrators began to pursue concerted policies of conservation starting in the 1860s and 1870s, they focused on historicizing buildings and diminishing evidence of their continued use.Footnote 37

In contrast, in locally authored histories of Hyderabad state, stoneworkers were positioned as capable of restoring the work of their regional predecessors and engaging with emerging techniques of tomb construction.Footnote 38 To the chagrin of twenty-first-century conservators, in Hyderabad, there was little emphasis on diminishing evidence of nineteenth-century influence on the tombs or the continued use of their surrounding mosques and public complexes.Footnote 39 From the perspective of modern conservators, Sālār Jung's repairs and updates contributed to ‘damage’ to the tombs but, for early twentieth-century Hyderabadi writers, the repairs applied ‘modern’ materials to the local heritage of Hyderabad city.Footnote 40 Funding new plasters for the tombs’ domes and the creation of raised floors, Hyderabadi elites ensured that the tombs and adjacent mosques and shrines continued to act as living sites of Muslim—particularly Shīʿa—practice in Hyderabad. They argued that it was possible to appropriate and apply ‘modern’ materials and technologies to tomb work, just as they might apply these materials to palaces or administrative buildings. State administrators positioned the religious meaning of the tombs as largely distinct from these ‘modernizing’ practices, and we shall see that this was a significant point of difference with many of the labourers who worked on the projects.

What Christopher Bayly termed ‘elite expenditure’ as an ‘expression of legitimacy’ within the contested space of late Mughal-era North India thus had an afterlife in Muslim-led states, where elite patronage of tombs contributed to regional legitimacy.Footnote 41 Models of expressing legitimacy through tombs included the creation of a regional ‘saintly heritage’, claims on an imagined Mughal past, and the preservation of older tombs to articulate local histories. Local political, social, religious concerns shaped which of these models were emphasized. Nonetheless, in all three states, elites negotiated what they saw as an intrinsic divide between authority wrested in the Islamic past and that rooted in the technological practices of colonial modernity. As we shall see, they often employed intermediaries trained in British Indian industrial and engineering schools to oversee the application of ‘modernizing’ technologies to these projects, ultimately creating new educational and cultural hierarchies within tomb construction.

Technically educated intermediaries and monumental-tomb construction

Prior to the late nineteenth century, most individuals employed to direct the labour of stoneworkers on monumental-tomb construction projects in Rampur, Bhopal, and Hyderabad were drawn from the families of prominent regional craftsmen, particularly masons. However, the rise of technical, engineering, and arts schools in British India—and later also in native states—meant that these local lead masons were increasingly displaced by engineers, architects, and others with training from state-led educational institutions.Footnote 42 The technical practices of master craftsmen and their middle-class technical intermediary successors were often aligned, meaning that they expected similar physical work from the labourers they oversaw. Nonetheless, the divergent cultural content of their education informed how each group of overseers made sense of their role in defining and presenting regional Islamic heritage. Apprenticeship-trained master craftsmen and lead masons positioned new technologies of construction within narratives of the local—and often Islamic—development of their trades. On the other hand, institutionally trained overseers, like many state elites, articulated an inherent divide between Muslim authority and the technologies of ‘modernity’, even as they sought to use the latter to preserve or build the former. We shall now contrast the experiences of these master craftsmen and new middle-class technical intermediaries, analysing how their differences in educational backgrounds shaped their engagement with monumental-tomb construction across the three states.

Allah Jilayah, a lead mason in Bhopal State who oversaw projects of monumental-tomb construction, is representative of the class of intermediaries that most native state stoneworkers encountered before the turn of the twentieth century. Employed by the state in the early 1890s, Allah Jilayah designed and oversaw the construction of several of Bhopal's most prominent buildings, including the Ṣadar Manzil, the state's public-audience hall.Footnote 43 Descended from a family of Agra masons who had moved to Bhopal as part of the migration of skilled craftspeople to that state after 1857, Allah Jilayah was educated at home and went on to teach his son his craft.

While Allah Jilayah was grounded in the practice of a familial craft, he engaged closely with new technologies and materials. For instance, he employed stoneworkers to work with new plasters and styles of carving to expand the Shaukat Maḥal, a city palace originally designed by French architects.Footnote 44 While records list Allah Jilayah as a mistri (supervisor or lead craftsman) and lead mason, until the early twentieth-century professions of oversight were flexibly defined in most native states. Allah Jilayah engaged in drafting and planning work that was later more closely associated with institutionally trained positions like architects and engineers.Footnote 45

However, Allah Jilayah differed from his successors due to the form and cultural content of his technical education. An 1869 Urdu-language text entitled Dastūr al-Banā’ (The Rules of Building) reflects the cultural context through which family-educated master craftsmen like Allah Jilayah likely understood technological and material changes in tomb construction. Dastūr al-Banā’ adapted content from popular British Indian engineering textbooks while also rooting discourses of construction in a regional Indo-Islamic idiom, including the explicit connection of masonry work to Sufi lineages and shrines.Footnote 46 Reflecting the demand for this style of writing in native state cities, the printed treatise was purchased by both the Rampuri and Bhopali state libraries, and likely also circulated among master craftsmen there.

The author of the Dastūr al-Banā’, Sayyid Muḥib ‘Alī Khān, narrated the exploits of saints and elites who left behind major tombs and also described the precepts of modern construction. Muḥib ‘Alī Khān informed his readers that he moved to Bihar to work as a ḥakīm (a doctor of ūnānī medicine). There, he became fascinated by the design of historic shrines and mosques in nearby Phulwarī Sharīf. He developed his knowledge of their construction to the point that a local landholder asked him to compose a treatise on building.Footnote 47 Alongside chapters that seem to borrow from contemporary engineering textbooks—‘On building walls of baked brick’, ‘On the laying of floors’—Dastūr al-Banā’ discusses the author's education at the shrine of Sayyid Makhdūm Rāstī at Phulwarī Sharīf.Footnote 48 He explained new technical practices by integrating them with narratives of the saintly or miraculous content of tombs and shrines, rather than divorcing them from the religious content of tombs. Sayyid Muḥib ‘Alī Khān did not perceive a divide between new technologies of construction and Muslim religious practice. To the contrary, he asserted an explicitly Muslim craftsmanship, in which his ability to incorporate materials, tools, and technologies of labour was rooted in his study at Sufi shrines.

Vernacular-language periodicals on construction also contributed to the adaptation of European-derived precepts of construction within local knowledge systems. For instance, Indian Architect (written in Urdu as Indian Arkitīkt) was an Urdu-language journal printed in Lahore and aimed at Indian architects, masons, and engineers (Figure 4). The journal was supported financially by native state courts and counted among its readers students at British Indian and native state engineering colleges, as well as apprenticeship-educated masons.Footnote 49 A May 1891 article entitled ‘The use of stones for constructing buildings’ instructed readers on how to use a mason's hammer, chisel, and straight edge, and gave directions on measuring and modifying the angles and corners of stone blocks. It went on to teach readers to use a mason's trowel to apply plaster to create a level base when beginning a large-scale masonry project.Footnote 50

Figure 4. Indian Architect encouraged masons, architects, and engineers to study earlier Indo-Islamic architecture including the Chaurāsī Gumbad in Kalpi. Source: Indian Arkitīkt, 11:7 (Lahore, July 1895), p. 110.

A note that graced the cover of each issue explained that the magazine provided ‘all types of engineering articles and drafts of old and new buildings, both English and Indian, are rendered into the Urdu language’.Footnote 51 The choice of Urdu was in part due to the magazine's centre of publication in Punjab, where colonial administrators elevated Urdu as a language of vernacular education over Punjabi well into the twentieth century.Footnote 52 It also reflects the late nineteenth-century reality that Urdu connected readers across the subcontinent's many political, social, and regional divides, enabling the magazine to reach diverse Indian audiences. Throughout the journal's run, the architectural style and methods of construction used in Mughal-era and earlier periods of Islamic rule in North India were popular topics. The journal emphasized an understanding of an Indo-Islamic past as a potential source for the renewal of Indian building practices and styles.

The journal also suggests a space of overlap between apprenticeship and home-educated master craftsmen and the institutionally trained intermediaries who increasingly displaced them in the oversight of construction around the turn of the twentieth century. The journal was aimed in part at Urdu literate craftsmen and masons who sought to independently develop their knowledge of colonial state preferences and practices in architecture and construction. At the same time, it allowed middle-class intermediaries who had trained in engineering and technical colleges and subsequently accepted postings across the subcontinent to remain abreast of the latest developments in their field.

As Gail Minault has argued in the case of Urdu-language women's magazines aimed at middle-class Muslim women, late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century periodicals contributed to a sense of shared class identity. They allowed individuals who lacked easy or frequent direct contact with each other to develop cohesive norms.Footnote 53 Intermediary professionals working in different regions across India similarly developed shared practices and identities through trade periodicals. In the case of Indian Architect, this meant that trained architects, engineers, and other associated professionals maintained similar standards even as they found employment across the subcontinent.

Lead masons like Allah Jilayah likely developed some shared norms with the graduates of British Indian technical and engineering schools through periodicals like Indian Architect, but their educational and social milieus remained distinct. Unlike apprenticeship-educated master craftsmen and lead masons, the emerging class of technical intermediaries was often drawn from middle-class or service-gentry backgrounds. They studied using formal British Indian engineering and construction manuals. Texts aimed at their craftsmen predecessors, like Dastūr al-Banā’, did demonstrate a familiarity of British-authored engineering textbooks. However, they communicated this knowledge through in an Indo-Islamic idiom that did not assume a contradiction between Muslim practice and new technologies and materials. On the other hand, textbooks aimed at institutionally trained technical intermediaries saw new technologies and materials as ‘modernizing’ in nature. They promoted a uniform middle-class professionalism that could be applied equally to state public-works and tomb construction. These new intermediaries therefore increasingly understood their role as applying ‘modern’ technological and material practices to ‘traditional’ Muslim spaces like tombs.

Formal vernacular textbooks used in colleges were in part translations of British texts, although they also integrated discussions of local materials.Footnote 54 For instance, the compilers of an 1873 work, Building Materials, borrowed from British texts in their discussion for the division of types of stone, noting that, for engineers, the important distinctions are between granular free-stone, slab-stone, and rubble-stone, which differ from each other in terms of their hardness and strength.Footnote 55 The authors then addressed local materials, including the use of slab stones to construct Indian courtyards and terraces, and regional styles of stone moulding.Footnote 56 These textbooks were primarily used in British Indian engineering and technical colleges, but they circulated within smaller technical schools founded in native states in the late nineteenth century. Texts like Building Materials thus contributed to an evolving set of expectations shared by newly prominent, institutionally educated middle-class technical overseers across states.

Of the three states under study here, the preference for the new class of institutionally educated intermediaries over home- and apprenticeship-educated master craftsmen consolidated most rapidly in Hyderabad, beginning in the 1870s. This was first because the state's robust internal bureaucracy relied heavily on North Indian migrants—many educated in British Indian institutions—who brought members of their own class to oversee state construction projects.Footnote 57 In addition, the state integrated many of its most prominent tomb-repair and -construction projects with its Public Works Department (PWD) and borrowed from PWD hierarchies in the oversight of tombs. Finally, Hyderabad was one of a small number of native states to host its own engineering college, founded in 1869. This led to a hierarchy that gave preference to graduates from British Indian institutions at the highest levels but also relied on local engineering graduates at the lower levels of oversight. Under Sālār Jung I, Hyderabad state enforced preferences for graduates of British Indian schools (and Europeans) at the highest levels of the state's PWD.Footnote 58 The local engineering college trained sub-surveyors, sub-overseers, and draftsmen, to work under civil engineers, surveyors, and overseers graduated from Thompson Civil Engineering College in Roorkee (f. 1847) or the Guindy College of Engineering in Madras (f. 1794).Footnote 59

Hyderabad elevated Indian engineers to more prominent technical positions than they could secure in British India. The state also developed a locally educated class of sub-surveyors, sub-overseers, and draftsmen who oversaw many facets of monumental construction. However, state preferences for members of these classes across the public-works system eventually led to the displacement of master craftsmen as overseers and intermediaries in local monumental-tomb construction. Hyderabadi records suggest that apprenticeship-trained intermediaries retained positions in monumental-tomb construction and repair through the early twentieth century, but they were pushed down the emerging hierarchy of technical work.Footnote 60 Their educational backgrounds meant that they maintained a cultural alignment with many of the labourers that they oversaw, but they found themselves increasingly alienated from the preferences of the state bureaucracy and institutionally educated supervisors.

Rampur state formalized preferences for institutionally educated oversight of tomb construction significantly later than Hyderabad. As noted above, the state's engagement with European-led construction projects began in earnest under Ḥāmid ‘Alī Khān (r. 1889–1930). Even then, the state's lack of local industrial schools, and the fact that it was often a less alluring post for institutionally trained overseers from British India, meant that some apprenticeship-educated lead masons retained high-ranking positions in tomb construction. Urdu-language manuals like the Dastūr al-Banā’ remained popular between the 1870s and 1920s, suggesting the continued relevance of local apprenticeship models of education—and their accompanying cultural content—in tomb construction.

Although craftsmen who had trained outside of formal institutions retained influence over tomb construction for a longer period in Rampur than in Hyderabad, by the 1910s, Rampuri elites often imposed British India-trained overseers on their projects. As a result, the education of the remaining master craftsmen and lead masons increasingly emphasized adaptation to the technical preferences of institutionally trained overseers. Sayyid Taṣdiq Ḥussain, the author of an Urdu manual entitled Engineering Book (transliterated as Injinīring Buk), explained that he ‘saw the need for contractors (thīkīdār), supervisors (mistrī), and other people who work in construction… to have a book like this in which they can learn … all the key aspects of engineering’.Footnote 61 His work, which circulated in Rampur state in the 1910s, focused on explaining the practices of British Indian PWDs to construction supervisors who worked and trained outside of that context. The treatise was published by a local Shahjahanpuri publisher, the Nāmī Press, better known for its collections of Urdu poetry and a periodical journal entitled Muraqqaʿ (The Album), which often included reflections on Islamic practice and piety.Footnote 62 Though it retained some markers of the local religious and cultural rooting of apprenticeship-trained intermediaries, its focus turned more explicitly towards the technologies and materials preferred by PWDs, for instance through a discussion of new plasters.Footnote 63

As we have seen in the case of Allah Jilayah, in Bhopal, some apprenticeship-educated lead masons and master craftsmen continued to supervise tomb construction through the 1890s. Although Bhopal did employ British India-trained engineers, architects, and supervisors in its PWD beginning in the 1870s, state elites’ emphasis on ‘Mughal revival’ led them to develop a bifurcated system of construction and oversight. From 1875, a European chief engineer oversaw the construction of Bhopali roads, waterworks, bridges, and ‘major district works’, and led a PWD office comprising Europeans and Indians educated in British Indian industrial and engineering schools.Footnote 64 At the same time, the state appointed a Bhopali muhtamim-i taʿmīrāt (superintendent of building), who oversaw the construction of state palaces and public offices, as well as most state-sponsored religious construction.Footnote 65 The office of the muhtamim-i taʿmīrāt, while also occasionally employing individuals educated in British Indian industrial and engineering schools, provided greater space for lead masons like Allah Jilayah to direct work on monumental-tomb construction.

State elites in Bhopal promoted individuals like Allah Jilayah, descended from a family of Agra masons, as part of their efforts to lay claim to the Mughal past. At the same time, as in both Hyderabad and Rampur, the consolidating influence of the new class of technical intermediaries, educated primarily in formal British Indian institutions, ultimately extended to the realm of tomb construction. Even when master craftsmen and apprenticeship-educated lead masons maintained some role in tomb construction, their models of education and understandings of the projects that they worked on were increasingly marginalized.

As locally trained master craftsmen were pushed downwards in an emerging hierarchy of technical oversight, their modes of interpreting tomb construction and fashioning identities through their work at these sites became increasingly marginalized. This marginalization led to a divergence in how stoneworkers and their institutionally educated supervisors understood the role of tombs and the relevance of their own labour in monumental-tomb construction. As we shall see, however, the increased alignment of master craftsmen with labourers, and their marginalization from the state, ultimately contributed to the circulation of narratives connecting technological adaptation and religious practice among stoneworkers themselves.

Monumental tombs as sites of labour

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, stoneworker labour at tomb sites was increasingly subsumed within native state adaptations of what Gyan Prakash termed the ‘technologizing exercise of state power’.Footnote 66 As a result of the consolidation of new technical intermediary classes, state and elite projects were represented to labourers and the public as processes of ‘improving technics and their application’.Footnote 67 Through the adaptation of new practices mediated by these intermediaries, stoneworkers encountered technologized expressions of adaptive ‘modernity’. At the same time, they developed their own narratives of the role of labour and technical change at monumental Muslim tombs. These remained distinct from the claims articulated and enforced by the state and middle-class intermediaries.

Stoneworkers engaged new technologies and materials through narratives of the saintly or miraculous content of tombs and shrines, or by integrating the acquisition of new technical knowledge within prayer and demonstrations of piety. Not all stoneworkers who laboured at monumental native state tombs were Muslim. But, in the urban areas of the three states studied here, large masonry workshops comprising primarily Muslim workers were contracted for these projects.Footnote 68 Workshop composition reflected the demographics of the neighbourhoods in which they were based, as well as the partially hereditary nature of apprenticeships.Footnote 69 Through their employment on tomb construction, masonry workshops in Hyderabad, Bhopal, and Rampur cities provided space for Muslim stoneworkers to fashion new understandings of the intersections of their labouring and religious identities. We will turn now to the physical and material adaptations that stoneworkers made in response to the technologizing demands of each state. Ultimately, however, we will see that, even as they necessarily responded to state claims on technology, stoneworkers fashioned their own labouring identities, which occasionally contradicted state narratives of monumental construction.

As we have seen, in Rampur, the state's preference for institutionally educated technical intermediaries consolidated later than it did in other states, and apprenticeship-educated lead masons continued to oversee tomb construction into the twentieth century. Nonetheless, due to the state elite's increased emphasis on adapting the materials and technologies of colonial modernity, even at tomb projects directed by local lead masons, stoneworkers rapidly adapted to new technical preferences. Stoneworkers and other artisans who engaged in tomb construction necessarily cultivated a technical fluidity, enabling their movement between state PWD projects and tombs and monuments patronized by regional elites. Sayyid ‘Azzat ‘Alī, a stone-carving calligrapher of early twentieth-century Rampur, is representative of this fluidity: between 1903 and 1918, he was hired to engrave dates, names, and verses on projects as diverse as a small Sufi shrine that adjoined the city's central bazaar and the city's Municipal Office, designed under the watch of a European engineer.Footnote 70 He was trained by his family to carve in the Urdu nasta'līq script and did most of his carvings at tombs in Urdu but, after his talents attracted PWD attention, he also began engraving in English and Hindi.Footnote 71 For Sayyid ‘Azzat ‘Alī and other Rampuri stone-carvers, engaging with the state's ‘saintly heritage’ meant maintaining knowledge of the stones and styles preferred by the patrons of tombs. Simultaneously, however, they expanded their practices to take advantage of economic opportunities in the construction of administrative buildings.

Even when they worked under apprenticeship-trained master craftsmen and lead masons, by the early twentieth century, Rampuri stoneworkers were also expected to incorporate new materials into tomb construction. New plasters were the most notable materials incorporated into tomb construction. The 1913 Urdu-language Engineering Book shows that, by the twentieth century, even home- and apprenticeship-trained intermediaries enforced material practices borrowed from colonial PWDs. The text was used in Rampuri technical intermediaries in a period when concrete plastering was rapidly becoming the go-to method of erecting edifices and repairing older structures. It included a lengthy chapter entitled ‘About concrete’, which explained:

the concrete mix must first be well wetted with water, then mixed with lime. Ensure that all imperfections are removed before the pouring of a foundation or roof… If the prepared concrete is still absorbing water, or if multiple imperfections remain deeper than one inch, then the quality of the concrete is poor and unusable.Footnote 72

The section went on to describe measurements for concrete foundations and roofs, and the concrete–lime–water ratios that one should use for each. These measurements were borrowed from the United Provinces Public Works Department manuals, reflecting the influence of public-works regulations in even ostensibly non-state construction manuals.Footnote 73

For labourers in Rampur, the circulation of these texts among their immediate supervisors and overseers meant that, in order to retain employment, they necessarily learned and incorporated the properties and uses of new concrete plasters. This experience seems to have been nearly universal in tomb construction among stoneworkers, regardless of whether they laboured under institutionally or apprenticeship-trained intermediaries. Indeed, in Hyderabad, the pressure to rapidly adapt to new plasters was likely even more pronounced, and shaped the expectations placed on stoneworkers by intermediaries at all levels of the emerging technical hierarchy. Beginning in the 1880s, Hyderabadi administrators developed the state's extensive limestone deposits around the area of Shahabad near Gulbarga.Footnote 74 The development of these new quarries sometimes meant an increase in workshops’ profits, as reliance on cheaper local stones brought down workshop overheads; it is unclear, however, whether this translated into an increase in salaries for most stoneworkers.Footnote 75

New mines may have driven down the prices of some popular stones, but of equal consequence for stoneworkers were new practices of plaster-making: although cement did not become popular in Indian native states until the late 1910s, in the preceding decades, Hyderabadi engineers began experimenting with new mixtures of lime mortar and clay plasters, taking investigative trips abroad to Europe and the United States of America.Footnote 76 In the realm of plasters and other new materials, we can identity how the hierarchy of intermediaries and labourers contributed to the translation of elite ideologies of tomb architecture. High-level intermediaries like state engineers and others educated at British Indian institutions like Roorkee were responsible for developing the mines around Gulbarga.Footnote 77 Members of this group carried out experiments with new plasters using locally mined lime and mandated the use of these plasters to state public-works and railway projects. Locally educated intermediary groups like lead masons learned to use these new materials through their engagement in state projects and were responsible for directing labourers in their use. When these lead masons and sub-overseers were contracted to work on projects of tomb architecture, they required the labourers that they oversaw to adapt the technological practices popular elsewhere in state construction to the aesthetic preferences of tomb patrons.

In addition, emerging elite engagement with European architectural aesthetics in Hyderabad, combined with the high level of influence of institutionally educated intermediaries from the 1870s, meant that stoneworkers necessarily rapidly adapted to new stylistic preferences. For instance, at Shāh Khāmūsh dargāh, constructed beginning in 1871 in Hyderabad's Nampally neighbourhood, stoneworkers encountered European stylistic elements borrowed from gothic architecture. They were expected to incorporate these gothic architectural elements into the specific Sufi milieu of Nampally's popular shrines. The dargāh received patronage from Āsmān Jāh, a local noble with a penchant for gothic architecture, who expected the stoneworkers to adapt European styles to a Hyderabadi religious context.Footnote 78 Overseers required the site's cadre of stoneworkers to incorporate arches and pillars modelled on European churches and palaces.Footnote 79 However, the expectations for the style of the dargāh were also based on the vision of the shrine's caretaker, who worked to ensure that the design was accepted by worshippers in a neighbourhood crowded with more prestigious Sufi shrines.Footnote 80

Stoneworkers in Bhopal likewise negotiated localized elite and intermediary pressures to incorporate new materials, styles, and techniques into tomb construction. The state's emphasis on ‘Mughal-revival’ architecture, alongside the efforts of some state elites to reform tomb and shrine construction and practice, heightened the importance of stoneworker technical fluidity. As noted above, reformist ideas about the appropriateness of large tombs promoted by elites like Ṣiddīq Ḥasan Khān did not seem to impact the styles of stonework at the prominent noble tombs in Bhopal. Nonetheless, they ultimately shaped the employment available to stoneworkers who laboured on more modest graves throughout Bhopal. Reformist ideas on the questions of tomb style were popularized through manuals advising pious ordinary Muslims on funerals. These texts explained the style of graves preferred by early Muslims and were printed cheaply across India.Footnote 81 A popular mid-nineteenth-century text on death and burial, Zād al-ākhirah (Provisions for the Hereafter) argued that a simply engraved tombstone with the deceased's name and verses indicating the date of death was acceptable, but the construction of large tomb complexes was to be avoided.Footnote 82 Proscriptive texts like Zād al-ākhirah had the greatest impact on the work that carvers were commissioned for in local cemeteries. Cemetery boards in Bhopal sometimes accused local Muslims of embracing elaborately carved gravestones similar to those found in local European Christian graveyards and discouraged this practice.Footnote 83 As a result, the workers who carved these stones negotiated cemetery-issued proscriptions on the style of gravestones and local demand that both informed and occasionally contravened those regulations.

While the carvers who were employed to create tombstones in these Bhopali cemeteries encountered state, elite, and intermediary-informed stylistics, they did not face the same level of technical scrutiny as those employed in monumental construction. In Bhopal, efforts to evoke Mughal Delhi and Agra meant that stoneworkers were required to engage most closely with red-sandstone and white-marble work.Footnote 84 Work in these materials had a long genealogy in South Asian monumental and tomb construction but, prior to the nineteenth century, they were relatively rare in Bhopal, with red-sandstone construction especially unusual. In part, this was because the Mughal state had maintained close control of the sandstone deposits near Agra, limiting access to the material among other regional potentates. As a result, Bhopali stoneworkers were required to rapidly adapt their physical labour not only to the popularization of newly developed plasters, but also to materials that were prominent elsewhere in India but previously rare in local construction.

The particular materials, practices, and styles that stoneworkers were expected to adapt to differed across the three states, depending on the political, religious, and social concerns of the courts and the intermediaries that they employed. In all three cases, stoneworkers exhibited the ability to rapidly incorporate new technologies, styles, and materials into their labour, likely because their continued employed relied on this degree of flexibility. However, as Nita Kumar has posited, artisans ‘do not always consciously adopt’ the momentum of ‘urban expansion and … technological development’. They nonetheless manage to build lives and livelihoods within these processes, self-fashioning new cultural and labouring identities through their work.Footnote 85 Even as stoneworkers incorporated new technologies into their work on monumental tombs, they fashioned new labouring identities that complicated and contradicted the state's understanding of the role of new technologies and practices in monumental-tomb construction.

As we have seen, state elites and new classes of technical intermediaries argued that it was possible to apply the technologies of colonial modernity to spaces evocative of a Muslim past and, in doing so, ‘modernize’ the skill sets of workers who laboured in Muslim spaces. The models of training used by most home- and apprenticeship-trained master craftsmen often embraced an alternative narrative, in which the adaptation of technologies was portrayed as part and parcel of Muslim labouring culture. Both these master craftsmen and their models of education were marginalized around the turn of the twentieth century across all three states. However, this model of understanding the relationship between religion and labour, and particularly the role of new technologies at sites of Muslim mourning and monumentality, persisted among the stoneworkers responsible for physically erecting tombs. Indeed, as master craftsmen and lead masons were pushed downwards in local hierarchies of construction, they likely engaged more closely with artisan labourers, contributing to the spread of narratives that integrated technological change with the Muslim past.

For instance, an 1875 treatise on construction entitled Tazkirah al-Aīwān (Recollections of Buildings) used relatively short poems, prayers, and verses to explain the principles of construction. This suggest that its contents may have been used in masonry workshops and apprenticeships where most training was oral, rather than dependent on high levels of literacy.Footnote 86 To establish his authority in construction, the author, an architect named Riyāsat ʿAlī Sarshār, borrowed the Sufi parlance of the murīd–murshid (teacher–disciple) relationship to describe his own apprenticeship.Footnote 87 He also noted his role in the construction of an imāmbāṛā near the town of Fatehgarh in the North-Western Provinces.Footnote 88 Although some portions of the technical contents of the Tazkirah al-Aīwān suggested a familiarity with the contents of British Indian construction manuals, its cultural assumptions diverged significantly. Sarshār explicitly integrated new technical knowledge with prayer and demonstrations of piety, noting in verse that ‘the construction of buildings are described here, but they cannot be made but for the intercession of God’.Footnote 89 Versified sections explained how one should create ‘dividing walls’ through the combination of ‘wood strips and plaster’, but also suggested religiously auspicious dates for construction and claimed that ‘artisans who build structures glorifying God have received His blessing’.Footnote 90

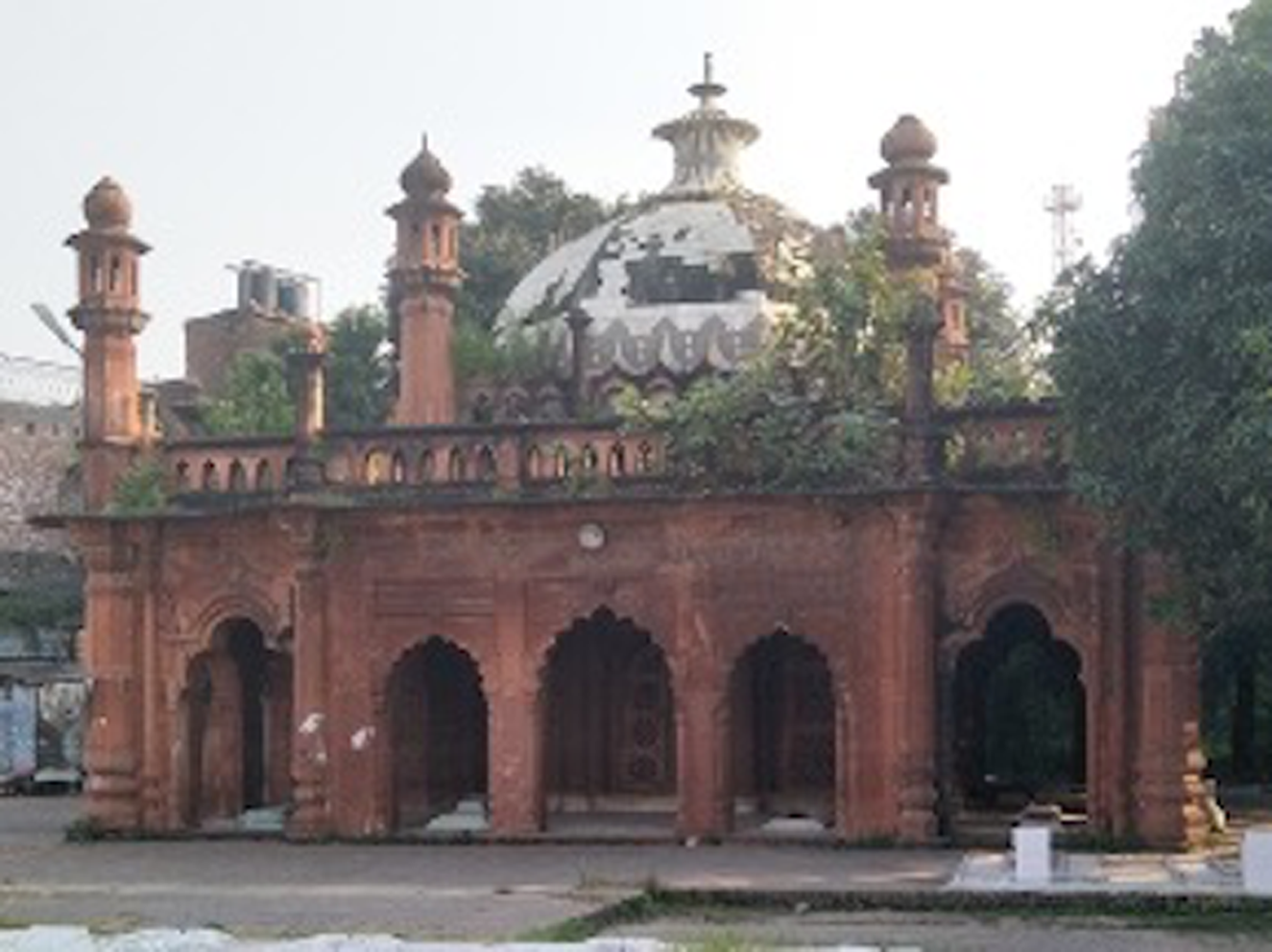

Rather than portraying new technical practices as distinct from a regional Muslim social milieu, or necessary for the ‘modernization’ of work, Sarshār integrated technical and material change into a continuous telling of the practices that he associated with Muslim construction. Stoneworkers engaged with these narratives in the context of local masonry workshops, where verses on construction precepts were likely read aloud and memorized. Masonry workshops were often led by lead masons and master craftsmen who, by the turn of the twentieth century, no longer occupied official state positions, but were contracted by the new middle class of technical intermediaries for work in tomb construction. The organization and work of the workshop of Sheikh Kallū Mistrī, a Rampuri lead mason active at the turn of the century, is suggestive of the ways in which stoneworkers incorporated their own labouring identities into tomb construction in a context of technical change. Sheikh Kallū Mistrī and his workshop were employed in the construction of a large tomb complex, begun around 1900 and intended to house the remains of a wife of the state's former Nawab.Footnote 91 Cadres of Rampuri stoneworkers created the intricate carving and jālī work that dominated the exterior of the structure and the walls surrounding the grave, and created a complex marble inlay atop the tomb's dome. Known in Rampur as the maqbarah janāb-i ‘āliyah, the complex was expanded over the following decades to house the remains of several other female members of the Rampuri royal family, an imāmbāṛā, and a small primary school (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The maqbarah janāb-i ‘aliyah, constructed beginning in 1900 in Rampur.

The labourers of Sheikh Kallū Mistrī's workshop, and other similar large masonry workshops, can broadly be grouped into three specializations: masons responsible for building the structures; carvers engaged in ornamental decoration; and calligraphic carvers, who wrote the inscriptions on both gravestones and monumental tombs. There was of course a significant overlap between these groups in many Indian cities, but larger workshops nonetheless maintained specializations and stoneworker hierarchies.Footnote 92 At the maqbarah janāb-i ‘āliyah, workers from Sheikh Kallū Mistrī's workshop were employed to grind the lime plaster, cut and lay the red-sandstone blocks, smooth the stone, cut jalīs, and carve calligraphy. Masonry apprentices in these large workshops began their careers as largely limited to plastering work, but many worked their way up to slightly higher-paid positions in middling cadres of masons.Footnote 93 Similarly, carving apprentices all engaged in ‘rough’ carving, but those who successfully trained in inlay work could receive higher wages and command greater prestige.Footnote 94

Although they maintained professional and social hierarchies, large masonry workshops that were contracted for major tomb-construction projects provided space for the consolidation of shared religious and labouring identities. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, institutionally trained intermediaries and state elites together asserted a greater degree of ‘technologizing’ authority over both lead masons and the stoneworkers who laboured under them.Footnote 95 As a result, lead masons increasingly occupied what Dipesh Chakrabarty has termed a ‘grey zone’ between authority and labour.Footnote 96 Their increased marginalization from the state, and alignment with the other members of their workshops, provided space for the rearticulation of identities that positioned technical adaptation as inherent to Muslim craftsmanship.

Masonry workshops ultimately provided a space for labourers to engage with the poetry, prayers, and historical narratives reflected in texts like Tazkirah al-Aīwān and Dastūr al-Banā’. Their popularity within apprenticeship and workshop contexts suggests that stoneworkers engaged with technological and material change as inherent in their own religious and cultural practices. Rather than seeking to ‘modernize’ construction, stoneworker modes of learning integrated new technologies into their telling of Muslim labouring practice. Likewise, rather than positioning the physicality of tomb construction as distinct from religion, equivalent in technical content to any PWD project, Muslim stoneworkers learned tomb construction as a reflection of their own religious practice.

Conclusions: stonework and stoneworkers between technical change and Islamic authority

Monumental tombs and Sufi shrines are popular sites of historical and anthropological research in South Asia because they are spaces in which a popular spiritual experience is intimately linked to the built environment.Footnote 97 Despite often holding miraculous associations, tombs and shrines are not rarefied sites that burst into being without the physical intervention of builders and funders. Craftspeople, labourers, and technical intermediaries are vital to their production and maintenance. This article has sought to redress the fact that the stoneworkers who constructed and maintained monumental Muslim tombs are often missing from scholarly narratives that focus either on patrons or worshippers. Both British Indian and native state archives subsume stoneworkers within elite Muslim narratives about the application of technologies and materials of colonial modernity to sites of Indo-Islamic heritage and authority. But, just as tomb patrons used these sites to articulate new forms of authority in colonial-era India, so too did technical intermediaries and stoneworkers fashion new religious, class, and labouring identities through their work on monumental tombs.

Stoneworkers at native state tomb projects found that their continued employment necessitated engagement with the technological and material change endemic in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century construction. But adapting to new articulations of state authority did not necessarily mean adapting or embracing state narratives about the role and meaning of technological and material change in Muslim-tomb construction. State elites and institutionally trained intermediaries positioned new technologies and material practices as inherently distinct from Muslim practice. They nonetheless appropriated them to ‘modernize’ physical spaces of Muslim heritage. In contrast, many stoneworkers and ‘grey-zone’ intermediaries learned new technologies as part and parcel of an Islamic history and Muslim practice for their trade. Due to the continued, though marginalized, influence of ‘grey-zone’ intermediaries like Sheikh Kallū Mistrī and Allah Jilayah, understandings of new technologies as inherent to the Muslim experience of labour at religious sites spread within workshops. The experiences of stoneworkers in Muslim-led native states reflect Chitra Joshi's argument that, among labourers, ‘identities of the workplace’ were forged through a communal navigation of the ‘conditions of work’.Footnote 98 Even as they were subordinated within new elite articulations of state power, stoneworkers constructed working practices that responded flexibly to the technologizing claims of the state.

Stoneworker modes of education and labour complicated state narratives by positioning technical change as inherent to Muslim labour at sites like tombs. Stoneworkers’ engagement with the intersection of their own labouring and religious identities undercut elite narratives of an inherent division between the ‘modernizing’ technical practices and the Islamic nature of the sites to which they were applied. State elites and institutionally educated intermediaries often viewed tombs as sites for the expression of authority and piety, but they saw the ‘modernizing’ techniques used on them as largely unrelated, equally applicable to tombs and PWD projects. Stoneworker integration of the religious with the material and technological subverted this understanding, reflecting an alienation of many labourers and craftsmen from state narratives of both religious authority and technical change. Ultimately, the experiences of stoneworkers at native state tombs suggest that labourers rapidly adapted to the technical demands of the state and its representatives, while maintaining distinct understandings of the relationships between religion, work, and technology.