A specter is haunting the international community—the specter of the parastate. All the powers of the Westphalian system have passed dozens of nonbinding resolutions to exorcise this specter: politician and journalist, president and foreign minister, European Parliament and Security Council. Where is the group calling for self-determination that has not been decried as “separatist?” Where is the opposition that has not reproached secession with defense of state sovereignty and territorial integrity?

Nature, size, orientation, and scope notwithstanding, the number of territorial entities that perceive themselves to be states, nascent states, future states, or imagined states has been growing, and has provided a formidable challenge to the international system and conventional understandings of sovereignty.Footnote 1 Within this family of breakaway, disputed, de facto, semi-, quasi- and non-sovereign territorial units, the parastate is the most prominent and the most problematic. Parastates are neither sovereign countries with limited recognition like Israel, nor are they autonomous regions with local decision-making coordinated with a central government like South Tyrol, Hong Kong, or the Åland Islands. Parastates are not even administrative units within an existing state that threaten self-determination like Republika Srpska, Iraqi Kurdistan, or Catalonia. Rather, the parastate is a political entity that has officially declared some form of independence, is able to secure control over a given territory, and possesses many trappings of statehood similar to sovereign states. However, parastates lack formal international support and recognition to achieve full sovereign independence and thus remain a disputed territory perpetually stuck in a political, military, and diplomatic stalemate. With examples ranging from Kosovo to Northern Cyprus; from Nagorno-Karabakh to Abkhazia; and from the Donetsk People’s Republic to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), the parastate appears to be the least welcome member to the family of territorial entities in the Westphalian system and seems to be growing in numbers over the past two decades.

Like most disputed territories, parastates display features of various strengths and capabilities. Some privileged few like Kosovo, Northern Cyprus, Abkhazia, and Nagorno-Karabakh, have managed to achieve free to partially free elections with party turnover that matches the organization and functional capabilities of many UN member states. Some like Somaliland possess all the trappings of government including currency, an organized military, and informal contacts with multinational corporations, yet lack a single recognition of statehood. Other parastates like the breakaway regions in Donbas are little more than a collection of dilapidated towns and checkpoints run by a rag-tag group of militias united only in determination to avoid reincorporation into Ukraine. Still others seem relics of a bygone age, like Transnistria, which declared independence from Moldova in 1991, or Western Sahara, which may be the only inhabited no-man’s-land in the world. Yet all parastates, regardless of internal viability, share one trait: the nonnegotiable desire for statehood and international sovereign recognition regardless of the seemingly insurmountable obstacles that prevent this.

Our use of the term “parastate” is more than simply an attempt at adding another synonym to an established body of literature to denote disputed and legally contested territories.Footnote 2 Our work recognizes, and largely aligns with, existing studies of “de facto states” (Pegg Reference Pegg1998; Bahcheli et al Reference Bahcheli, Bartmann and Srebnik2004), “quasi states” (Kolstø Reference Kolstø2006), “contested states” (Geldenhuys Reference Geldenhuys2009), and “unrecognized states” (Caspersen Reference Caspersen2012). In this, we identify parastates as part of a larger family of disputed territories that: (1) hold de facto control over all, or most, of the territory it claims for at least two years; (2) possess the capacity to govern over a fixed and settled population; (3) seek sovereignty with the intention of expanding and deepening its legitimacy; (4) have the ability to enter into relations with neighboring sovereign states; (5) relies on at least one “patron state” for diplomatic support, economic assistance, and military defense.

However, we choose the “parastate” designation to emphasize a number of additional points for unique cases that previous studies on de facto states do not take completely into account. A parastate meets all the criteria of a de facto state defined above, but in addition, can be considered an entity that: (1) issued an official declaration of independence outside international law, and in violation of an existing state’s sovereignty; (2) produces a regional security dilemma between supporters and opponents that remain locked in frozen conflict that can last years, if not decades; (3) has almost no prospects of achieving international statehood and will continue to exist as a frozen conflict unless it is either recognized or retaken militarily by the parent, or “host” state. Thus, while our research remains indebted to previous studies, we feel that parastates identify a number of unique and exceptional cases around the world that go beyond existing understandings of “de facto” states.

First, parastates are not simply states in the making as preexisting literature seems to infer. They are entities that have unilaterally declared independence in contravention of international law. Additionally, a large number of parastates have forcibly, and in many cases violently, seceded from an existing sovereign country, and actively seek sovereign independence after having successfully supplanted the power of that country with decision-making of its own. Through its own institutions, parastates directly challenge the constitutional laws of the internationally recognized state it broke away from. Both of these actions place parastates in conflict with the majority of the international community as an open affront to the territorial integrity of an existing state. As such, a parastate is perceived not as much as a self-invited newcomer to the international system of states, as an aberration of it.

Second, whereas previous studies seem to leave open the question of whether any disputed territory will ever achieve international sovereignty, our understanding of parastates asserts such outcomes are rare and exceptional given the obstacles arising from the nature of their creation. The parastate’s quest for sovereignty is rooted in contentious politics, defiant refusals to compromise with the host state over anything less than independence, and is subsequently perceived as insurrectionary by opposing members of the international community. Not surprisingly, parastates generate international detractors with enough diplomatic leverage to prevent whatever de facto sovereignty it has acquired from becoming de jure. This is most clearly seen in the denial of United Nations (UN) membership, which is considered the ultimate benchmark for sovereign legality. Heading this opposition is the host state, which rarely extends recognition and, without strong international pressure, is under no obligation to do so.Footnote 3 Thus, while not impossible, the road to sovereignty for a parastate is as herculean as it is Sisyphean.

Third, while earlier studies question the long-term sustainability of disputed territories without a resolution in status, our understanding of parastates notes their tenacity to survive and adapt for decades by finding international allies, exploiting diplomatic loopholes, and maneuvering through the metaphoric cracks and crevasses of political and economic channels and backdoors created by the diplomatic stalemate that defines their existence. Analysts are wont to note the frozen conflict parastates find themselves in, but internally speaking, life goes on for the people who live there. Parastates come with a functioning government, security apparatus, and national symbols. They develop their own socio-political infrastructure, negotiate cross-border trade agreements, and some even issue their own passports. To that end, parastates have proven to be surprisingly resilient in the face of insurmountable odds. Northern Cyprus, Taiwan, and Western Sahara have all existed for more than forty years; Karabakh and Transnistria for more than twenty five; Kosovo and Abkhazia more than ten. Many have successfully resisted active attempts at reintegration with the host state, and short of a significant change in the international balance of power that weakens their leverage, a parastate can survive indefinitely.

Status aside, one critically important boon to a parastate’s stability and longevity is acquiring a powerful “patron state” to support their existence and speak on their behalf in international circles, as is already noted in existing studies on de facto states. In many respects, patron states provide an economic lifeline, a political voice, and most importantly a military defense (Florea Reference Florea2017). While this does affirm a significant degree of dependency and in more than a few cases turns the parastate into a veritable colony of its international sponsors, it does help explain why parastates last as long as they do. This is especially true if patronage comes with sovereign recognition, though it is not a requirement. Transnistria, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Somaliland lack even a single recognition but still rely on external guardianship. Regardless of strength and capability, supporting states view parastates as legal, sovereign, and irreversible. Though this patronage, parastates enjoy the piecemeal benefits of independent decision-making through external support and protection which ensures their existence on the map; albeit in a slightly different shade of color from the state it separated from.

Finally, we argue that the term “parastate” better captures the essence of these territories than previous terminologies such as “de facto states,” “quasi states,” or “unrecognized states” that may be “too fuzzy” a concept (Pegg Reference Pegg1998, 7). The “parastate” label removes any ambiguity associated with a larger and more random collection of disputed regions by limiting the study to a specific collection of contemporary territorial entities that have officially declared statehood as their ultimate objective and successfully dislodged the authority of an existing state from the region. This disqualifies previously cited de facto states like Republika Srpska, Iraqi Kurdistan, Puntland, and Catalonia; all of which remain autonomous—albeit contentious—provinces of their respective states.Footnote 4 Additionally, our criteria for parastates disqualify former nonincorporated territories like Republika Srpska Krajina in Croatia or Herceg Bosna in Bosnia which sought annexation and incorporation with Serbia and Croatia respectively rather than independence during the Yugoslav Wars of Secession in the 1990s. Finally, the seeming permanency of parastates eliminates a number of historical examples that lasted only a few years like Biafra, Katanga, Chechnya, or Bougainville; none of which developed any formal government beyond their wartime institutions, nor possessed an international sponsor to encourage one.Footnote 5

All parastates are functional de facto states, but many de facto states, defined as they are by their nonsovereign status, are not, and have never been, parastates. Republika Srpska and Iraqi Kurdistan may possess features of a state in the making, but neither has officially attempted to supplant the constitutional authority of the state they are a part of. We emphasize the distinct nature of parastates to denote their declaration of independence as an irreversible action, their seemingly intractable frozen conflict brought on by this fait accompli, and their equally apparent permanency in the international community. More than simply “de facto” due to their internationally disputed status on sovereignty; more than “unrecognized” due to their unique creation that belies any hope of achieving international sovereignty; and more than “contested” due to the perceived illegality of their existence; a parastate is, in so many words, an illegal parallel authority to a sovereign state. It operates alongside and closely resembles the functions and authority of the sovereign state, but it possesses attributes definitively absent from and abnormal to the sovereign state.

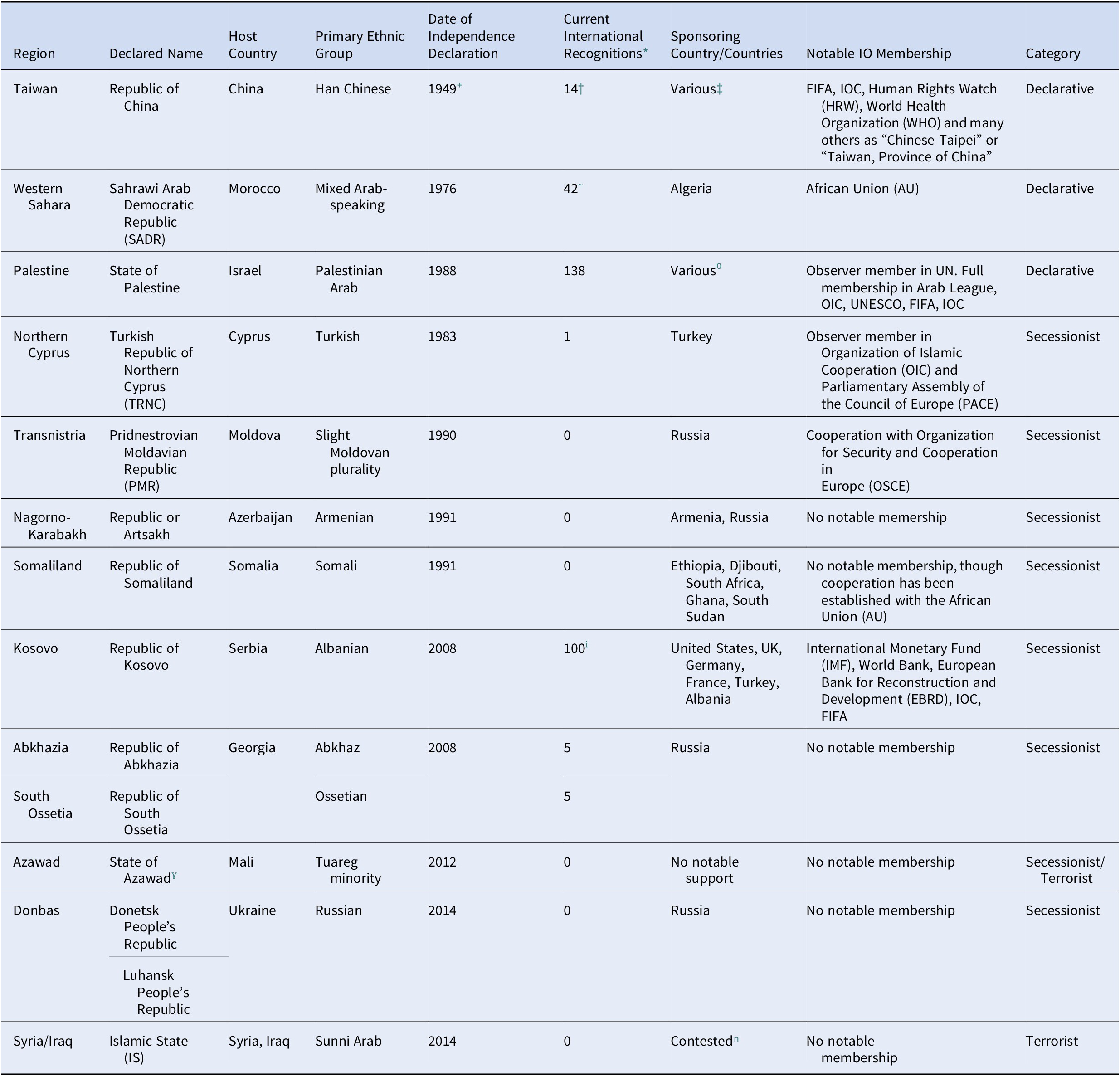

Our list of parastates only includes active cases as of 2019 (Table 1). While there is no official list of all disputed territories since 1945, a number of them have either been reincorporated into the host state such as Biafra in Nigeria, Katanga in Congo, Chechnya in Russia, and Tamil Eelam in Sri Lanka; or have managed to achieve independence like Bangladesh, Eritrea, and Timor Leste.Footnote 6 As with every disputed territory, their circumstances were unique to their origins. However, whether they qualify as parastates according to our criteria lies outside the scope of this study at current time. As this project develops and expands, an historical component examining these cases may indeed yield fruitful information in future publications.

Table 1. List of Parastates 2019.

* Listed recognitions only include recognitions from UN member states. Parastates often claim additional recognitions from nonstate actors. The parastates of Transdniestr, Karabakh, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia have all extended mutual recognitions to each other.

⁺ De facto sovereignty established December 1949 following defeat of Chinese Nationalists and evacuation to Taiwan. Offical sovereignty retroactively associated with founding of Republic of China in 1912.

† Taiwan is officially recognized as a sovereign state by 14 countries but maintains nondiplomatic relations with nearly 50 more, most from North and South America as well as the majority of western European states.

‡ The nature of Taiwan’s nondiplomatic relations with multiple states allows it access to multiple venues on the global economic market.

˜ Around 40 states have withdrawn their Western Sahara statehood recognition. This trend has been particularly significant since the late 1990s as a result of a successful counter-secessionist strategy pursued by Morocco.

⁰ The State of Palestine draws diplomatic support from most recognizing UN member states.

ⁱ The number of recognitions claimed by Kosovo is in dispute, as some of these have only been reported by Kosovo’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and not the recognizing country. At least ten states have withdrawn recognition.

ˠ The State of Azawad ceased to operate as a functioning parastate in 2013 after Malian and French troops recaptured the regions from control by Ansar al-Dine. The territory however tenuously remains under Bamako’s authority.

ⁿ It has been claimed that IS enjoyed unofficial support from a number of undisclosed countries via backdoor economic and military funding.

What all these “solved” cases tell us at least, is that contested status is eliminated by either one of two conditions: independence is achieved if, and only if, the host state recognizes the sovereignty of the disputed territory; or the parastate is destroyed if, and only if, the host state regains control over the disputed territory. While this naturally raises the question of whether any current parastates will also be “solved” one way or another, we feel most on our list have lasted long enough to be considered an indefinite frozen conflict and differ significantly in composition and capability from those mentioned above. Those that have endured for a decade or more enjoy at least one patron state powerful enough to sustain its existence against reincorporation into the host state, but not enough to counter international opposition that prevents its transformation into a de jure sovereign state. Two cases in our study—Azawad and the Islamic State—prove just that, both of which at the time of this writing have been militarily defeated and reincorporated back into their respective host states.Footnote 7 Yet both also show how much the international community is determined to “solve” the problem of parastates if they are either founded on, or in the case of Azawad taken over by, terrorist organizations. In this instance, international sponsorship falls almost completely on the side of the host state, which gives it the leverage necessary to retake the territory.

In this special issue we group parastates into three categories: secessionist, declarative, and terrorist. Secessionist parastates are the clearest types of parastates, while declarative and terrorist can be considered borderline cases in their own unique ways. Secessionist parastates form the first and most common group in international studies that include Northern Cyprus, Somaliland, Nagorno-Karabakh, Transnistria, Kosovo, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and the Donbas Region.Footnote 8 Though they have been previously researched as de facto and unrecognized states, we feel the additional criteria provided above set them apart as parastates. Secessionist parastates are breakaway territorial entities that exist at the expense of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of existing states. Most secessionist parastates begin as volatile and restless regions in weakening multiethnic states in which a compact ethnic group seeks to limit the authority of the central government that is perceived to be denying them certain political, economic, or cultural rights. These grievances can often give way to greater demands for self-determination if the central government seeks to reassert its authority against public wishes, and can quickly evolve into armed conflict if efforts are made by either side to forcibly seize control of the region. A parastate forms when authority of the central government is removed from a fixed territory and local leadership assumes control and declares some form of self-determination but the region still remains internationally recognized as part of the host state. The inability of the host state to reclaim control over the breakaway region yields a frozen conflict in which the parastate functions as the default and de facto authority. Thus, due to the nature of their founding coupled with the necessary sponsorship they need to stay alive, secessionist parastates are almost guaranteed to be long-term problems.

A second, smaller, category includes unique territorial anomalies like Western Sahara, Taiwan, and Palestine. These “declarative parastates,” as we call them, have either had their sovereignty usurped, as in the case with Taiwan, or denied, as with Western Sahara and Palestine. Whereas secessionist parastates are born out of weak and fragmented multiethnic states, declarative states are largely the residual product of disputed claims to former colonial territory. There is no “host state” to speak of because declarative parastates do not break away from existing countries. Rather, an internationally recognized sovereign state claims authority over the territory and uses its leverage to actively undermine the declarative parastate’s existence and deny it from achieving statehood. The official position of Taiwan as the successor to the pre-1949 Republic of China is perceived by the People’s Republic of China to be a violation of its sovereign authority, and though Beijing has never controlled the island, it lays claim to the territory just as it claimed Hong Kong and Macau. Likewise, Morocco controls much of the territory of Western Sahara claimed by the Sahwari Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), which sees itself as the only legitimate authority over the whole territory. But even though SADR’s main base of operations lies in neighboring Algeria, making it operate as a sort of state-in-exile, the territory of Western Sahara it does control is enough for Morocco to have worked for decades in preventing it from achieving any international legitimacy. Unlike secessionist parastates, declarative parastates, while contested, are not perceived to be as confrontational and illegal. Still, the uniqueness of each of their historical circumstances warrants consideration for their inclusion in our family of parastates, but their obstacles to statehood necessitate special categorization.

Lastly, parastates can be the result of international terrorist groups seizing territory and imposing their own authority and law. Here we specifically imply nonnational terrorist groups such as al Qaida and its various affiliates and offshoots around the world. In this, terrorist parastates differ from their “insurgent state” predecessors which use controlled territory as a base of operations to attack the central government and are frequently depicted as “terrorists” by host state media (McColl, Reference McColl1969). These groups may have employed terrorist tactics, but they operated within a larger socio-political framework of secessionism that had a specific target and a specific set of goals.Footnote 9 “Terrorist parastates” are those founded by terrorist organizations without any preexisting national affiliation for the purpose of creating new states and societies. Like their secessionist variants, terrorist parastates possess de facto authority parallel to the countries that claim its land, manage day-to-day operations in the regions they control, and even draw on unconventional international support for keeping it on the map. But a critical difference is that terrorist parastates understand territory in a flexible and malleable fashion and do not prioritize obtaining legal international recognition. Beginning with lofty visions by al-Qaida of a modern-day Caliphate that would replace the perceived decadent and Western-leaning states of the Middle East, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) came the closest to making this a reality by seizing large regions of Iraq and Syria and governing it as a state of their own.Footnote 10 In other words, the terrorist parastate violates the sovereignty and territorial integrity of multiple states at a time with the purpose of creating a super- or meta-state in their wake. Of the three groups, terrorist parastates might be the most problematic to include based on our criteria above. They lack formal international patronage and are neither interested in recognized sovereignty nor UN membership as secessionist and declarative states are. Moreover, their recent appearance makes studying their longevity and potential to exist in a frozen conflict somewhat problematic. The Islamic State exercised de facto control over territory in Iraq and Syria for little more than three years, although it existed as an organizational concept for at least a decade prior and continues to wield power and influence even today. Still, other examples like the takeover of the State of Azawad by al-Qaida affiliate Ansar al-Dine in 2012 show terrorist parastates can be defeated quite quickly. Nevertheless, in the short time they have operated, terrorist parastates function as de facto states that warrant additional study.

Amid the parastate’s perpetual stalemate in its quest to achieve international statehood, these papers make two conclusions. The first is that the very nature of parastates sows the seeds of their own diplomatic deadlock. Because leaders of contested and/or breakaway regions declare their independence outside of any coordinated agreements by international organizations, their claims to sovereignty over the territory, however definitive it might be, will remain indefinitely disputed. The nature of their creation, purpose of their existence, and ambiguity of their sovereignty make parastates intractable frozen conflicts because leadership in and interest groups associated with the breakaway region stand diametrically opposed to those supporting the host state’s claims to the territory. The second conclusion is that nearly all options for ending the impasse of parastates are either unrealistic to achieve or too costly to pursue. As mentioned above, one of the few possible options for ending the impasse of disputed territory is for the host state to retake it militarily, thereby destroying its authority and regaining control over the region. The cases of Katanga (1960–1963), Biafra (1967–1970), Chechnya (1991–2000), and Tamil Eelam (1984–2009) illustrate that the military solution may lead to a successful outcome for the host state (Florea Reference Florea2017). This however is a rare and risky strategy due to the costs of intervention, which in more than a few cases ended in deadlock or even defeat for the host state. Along with a near-guaranteed humanitarian crisis that would result from such incursion, even threats of intervention strengthens the resolve of the parastate authorities in seeking self-determination. Left within the status quo of a diplomatic and military stalemate, parastates survive by default.

The collection of articles that follow aims to address these issues and expand the general understanding of the parastate phenomenon by placing a number of its members within a broader comparative context of sovereignty, government and governance, trans-regional cooperation and diplomatic support, and the limited solutions available to opposing sides. The first paper by Michael Rossi provides the theoretical foundation for the entire study by noting the limited options available to parastates that are, by nature of their foundation, operating outside the formal structures of international law and recognition. Rossi notes that the primary obstacle for parastates transforming de facto statehood into de jure sovereignty is the nature of sovereignty itself and the critical importance that recognition from international governing organizations can grant. Left outside these groups, parastates remain disputed territories dependent on patron state sponsorship. This places parastates within a frozen conflict that allows it to indefinitely carry out day-to-day functions, but without being an equal member of the global community with access to and decision making in international organizations and governing bodies. Rossi concludes that while this outcome is not ideal to leaders of parastates, it is still lucrative enough to pursue because it provides more benefits and diplomatic leverage than accepting the status of autonomy or power-sharing with a host state that claims sovereign authority.

Mladen Mrdalj offers a unique examination of Kosovo, one of the best contemporary examples of parastates, by noting the long-standing policies of separatism that defined ethnic Albanian politics in the region since the late 1980s. Contrary to some conclusions that Kosovo’s separation from Serbia was predicated on abuses of human rights and ethnic conflict in the late 1990s, Mrdalj argues that ethno-national self-determination was a pursued and sustained practice by the majority of Kosovo’s Albanian community through systematic boycott of all Yugoslav political, economic, and social institutions since the late 1980s. This produced a type of virtual secession that facilitated the establishment of a number of parallel institutions that, under the leadership of Ibrahim Rugova, were seen to be a completely separate government that enjoyed support, albeit indirectly, from the United States. Kosovo thus offers a good example of how territories institutionally detach from their host state and seek external linkage to maintain some form of legitimacy. Alongside the refusal to cooperate on any negotiated solution that offered anything less than formal independence, Kosovo’s Albanian political leadership never lost support from the United States, which at any time between 1990 and 2008 could have ended all prospects for secession by forcing them to negotiate with authorities in Belgrade over status. Far from being sui generis based on the violence of the counterinsurgent conflict in 1999, as many tend to argue, Kosovo was a parastate in the making, years before hostilities erupted and independence was unilaterally declared.

Ion Marandici’s contribution on Transnistria explores the multiple dimensions of Transnistrian identity that had been crafted around the breakaway territory since 1991. While some scholars view the parastate’s nation-building strategy as a multicultural civic project, the analysis of recent demographic and educational data corroborated with the close examination of local media content and official discourses all point to the emergence of a distinct Russifying political culture of the public sphere away from Moldovan identity that existed throughout the Soviet period. Marandici documents the parastate’s politicization of collective identity and the attempts of Transnistrian elites to reimagine the political community as part of the Russkii Mir. These circumstances suggest that, in the long run, the breakaway region might function as the southeastern frontline of Russian irredentism with Transnistrian elites calling on the Russian Federation to annex it instead of seeking long-term constitutive sovereignty or a peaceful reintegration into Moldova.

The article by Irene Fernandez-Molina and Raquel Ojeda-García offers a rare look at Western Sahara, one of the oldest and least understood parastates in the world. The article argues that the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) claiming sovereignty over Western Sahara is better understood as a hybrid between a parastate and a state-in-exile, since it controls less than 25% of Western Saharan territory and its primary base of operations lies in neighboring Algeria. Despite its uniqueness, examining the case of Western Sahara/SADR in a comparative light reveals a striking number of similarities with both declarative and secessionist parastates. It exists within the context of a frozen conflict, where the stalemate has been reinforced by an ineffective internationally brokered peace settlement and the indefinite presence of international peacekeeping forces on the ground. Upon this background, many case-specific nuances surround the internal sovereignty of the SADR in relation to the first three criteria for statehood of the 1933 Montevideo Convention—territory, population, and government. When it comes to external sovereignty, the parastate of Western Sahara relies on four distinct partial forms of international (non)recognition: the fairly solid recognition of the Polisario Front as a national liberation movement and conflict party; the mixed “titular recognition” of the SADR as a sovereign state led by Algeria and around 40 additional states; institutional support from the African Union; and widespread nonrecognition of Morocco’s sovereignty claims over Western Sahara, which while it has been substantially reinforced in recent years, nevertheless holds similar characteristics to international opposition to Israel’s control and occupation of territory designated for the State of Palestine.

In their contribution, Edoardo Baldaro and Luca Raineri analyze Azawad, a region of northern Mali where a short-lived parastate of the same name was established in 2012 but had a longer history of conflict and separatism from the central government in Bamako. By investigating the history and the development of this relatively remote entity, the authors aim to problematize the distinction between secessionist and terrorist parastates, underlying the complex and evolving relations existing between nationalist Tuareg rebels and jihadist groups. Foreign military interventions and domestic state fragility play a crucial role in these dynamics. Despite the lack of any major international sponsor, Azawad was, at the very least, able to survive for a short while, mostly due to its remoteness and Mali’s inability of retaking the region. However, the frozen nature of the conflict was partly discontinued when the region fell under the control of jihadist armed groups. A French-led military intervention then helped Mali recover its sovereignty, thereby demonstrating the determination of international actors to eliminate parastates that harbor terrorist organizations. At the same time, state control remains contested. Thus, while the Republic of Azawad was dismantled, the authors stress that the region is far from reintegrated within Mali’s weak control and risks slipping away again. The case of Azawad sheds light on the declination of statehood in post-colonial Africa, showing the connections between parastatehood, hybrid governance, patronage politics, and statelessness on the continent. While it does not meet all the formal criteria for a parastate defined above, we include Azawad as a study of how would-be parastates fail and how its collapse was related less to our defined criteria and more because of its co-optation by a terrorist organization that attracted international attention.

The final article by Jaume Castan Pinos ventures into relatively uncharted territory though an examination of the terrorist parastate and its quintessential example of the Islamic State (IS), which controlled large swathes of Iraqi and Syrian territory between 2014 and 2017. One of the chief aims of the article is to understand how the terrorist attributes of the Islamic State cohabitate with its territorial ambitions. The core assumption is that the organization has prioritized, at least until 2017, the strategy of conquering—and controlling—territory in order to build a state-like project. In addition to analyzing the Islamic State’s intimate relation with territory and statehood, the paper will establish continuities and departures between this case and secessionist parastates. One notable feature is that without any specific region to claim, terrorist parastates can arise anywhere, even after the loss of territory in one location.

Suffice to say, parastates have been an inconvenient reality in contemporary regional security and stability for nearly 70 years. In just the last two decades, parastates have demonstrated the gains that could be made from acting outside international law and using the leverage gained through conflict in bargaining for a potentially better positon in regional politics and security. If anything, parastates also show how limited international law can be when faced with the Realpolitik of powerful states sponsoring their existence and keeping them as key players in any eventual peace agreement for the region. This gives reason to hypothesize that their numbers will increase in the near future, as would-be separatist movements look to current examples. As long as conditions allow for the parastate to exist, hope, however remote, that formal sovereignty is an eventual achievement remains alive. Even if that is never realized, the frozen conflict resulting from the diplomatic impasse lays the foundations of what its leaders and majority of citizens see as another country. By their very nature and increase in numbers, the parastate has challenged conventional understandings of the sovereign state and pushed existing studies of self-determination, models of citizenship, and rationales for vox populi in new directions of policymaking and scholarship; all of which have made a comparative study of this subject increasingly necessary.

Acknowledgments.

This collaborative project on parastates was first presented at the 23rd annual Association for the Study of Nationalities Convention, May 4, 2018, at Columbia University, New York. The authors would like to thank their fellow contributors for the initial collection of studies, the Nationalities Papers Editorial Board, and their manuscript viewers for their constructive criticism that helped emphasize the unique nature of parastates within the larger family to de facto states and territories.

Disclosure.

Authors have nothing to disclose.