Introduction

A discussion of nationalism theory might begin by returning to first principles: what is the purpose of nationalism theory? The objective of theory, I suggest, is to provide guidance for scholars examining a new case study. No one starts off as an expert in anything; the historical record is complicated; reality always holds surprises. Scholars pondering a particular national movement for the first time will inevitably have false preconceptions: scholars must inevitably make initial assumptions on the basis of sketchy, incomplete data and a provisional understanding of how the world works. Even in the ideal case, scholars undergo an unavoidable period of confusion and adjustment before they overcome mistaken preconceptions. In the worst case, however, scholars may never see their mistakes. Good theory should help overcome such problems: it should help us rid ourselves of false preconceptions, giving us better instincts for how nationalists think, how national movements develop, and more generally enabling us to better appreciate what historical evidence reveals.

Theories of nationalism might be judged on two criteria. Firstly, nationalism theory should align with the historical record: a theory of nationalism at variance with evidence must be discarded. Nationalism theory, of course, will never be physics. Quantum electrodynamics makes predictions that agree with experiment to a precision better than one part in a trillion, but the study of nationalism is neither nomothetic nor particularly quantitative. The historical record, furthermore, poses so many hermeneutical difficulties that scholars of nationalism cannot falsify an incorrect theory with a single decisive experiment. In other words, a theory of nationalism can provisionally survive an exceptional case. History, anthropology, and political science nevertheless remain empirical disciplines, and a theory of nationalism that repeatedly disagrees with evidence must be adjusted or discarded.

Secondly, nationalism theory should shed new insight. A theory of nationalism that explains the obvious remains preferable to an inaccurate theory, but scholars actually want theory to provide insights a naïve beginner would fail to grasp. Good theory should debunk common misconceptions, providing a short cut on the otherwise arduous path to understanding. In this sense, a good theory of nationalism should be surprising: the more unexpected a theory’s insights, the better it is.

By declaring nationalism a “modern” phenomenon, the so-called “modernist” school of nationalism, offers just this sort of surprise. The word “modern” has only a contextual meaning, of course, and nationalism scholars working in the modernist tradition do not agree precisely about when or where to locate the origin of nationalism. Ernst Gellner (Reference Gellner1983, 40) thought nationalism spread in tandem with the industrial revolution, since he believed the latter caused the former. Benedict Anderson (Reference Anderson1983, 64) looked to the Americas “between say, 1760 and 1830.” Eric Hobsbawm (Reference Hobswawm1992, 44–45, 102) depicted nationalism evolving in phases, proposing different chronologies for each phase, but dated “the principle of nationality” to “the period from 1830 to 1878.” Elie Kedourie (Reference Kedourie1960, 9–10) located nationalism at both “the turn of the eighteenth century” and “the beginning of the nineteenth century.” Miroslav Hroch (Reference Hroch1985, 23, 27) proposed a three-stage model, arguing that different nations entered different stages at different times, but mostly proposed 19th century chronologies. Nationalism theory is not physics: neither the origins of nationalism nor “modernity” can be dated to the millisecond, or even to a single year. Nevertheless, modernist scholars of nationalism agree that there was no nationalism in 1750; and that the era of nationalism was well underway by 1850. For the purposes of the “modernist” theory of nationalism, and thus for the purposes of this article, the emergence of nationalism, and the transition to “modernity,” occurred during the decades before and after 1800.

Modernist chronologies contradict popular opinion, which routinely projects national origins back into distant times. The theory that nations have ancient origins, usually called “primordialism,” has few supporters among nationalism theorists. Primordialism is nevertheless widespread in academia; indeed, far too ubiquitous for an exhaustive or comprehensive documentation. A few examples may nevertheless prove illustrative. Magnus Magnusson’s Scotland: Story of a Nation (Reference Magnusson2003, 34) described Dunadd, a medieval fort, as the “birthplace of the Scottish nation.” Ioan Pop (Reference Pop1999, 33) also dated “the formation of the Romanian nation” to the early Middle Ages. John Hoskin (Reference Hoskin1993, 17) posited “the 13th-century birth of the Thai nation.” Simon Payaslian (Reference Payaslian2008, 8, 40) traced the “emergence of the Armenian nation” to “the eighth and sixth centuries B.C.,” and perceived “national identity,” “national culture,” and “a distinct national cultural identity” in Roman times. In a comparative study, Margarita Díaz-Andreu (Reference Díaz-Andreu1996, 68) found that “throughout the two centuries of nationalism’s existence undoubtedly the most popular option has been to establish the germ of each nation in the medieval period.” Such chronologies are not reconcilable with modernism theory.

Indeed, modernization theory consciously contradicts popular ideas about the origins of nationalism, and several modernist scholars consciously present themselves as debunking popular misconceptions. Anderson (Reference Anderson1991, 5) contrasted “the objective modernity of nations to the historian’s eye vs. their subjective antiquity in the eyes of nationalists.” Kedourie (Reference Kedourie1960, 9) wrote that while nationalist ideas “have become fully naturalized … what now seems natural was once unfamiliar, needing argument, persuasion, evidences of many kinds; what seems simple and transparent is really obscure and contrived…” Gellner (Reference Gellner1983, 55) emphasized that “nationalism is not what it seems, and above all it is not what it seems to itself. The cultures it claims to defend and revive are often its own invention, or are modified out of all recognition.” In a passage approvingly cited by Hobsbsawm (Reference Hobswawm1992, 10), Gellner (Reference Gellner1983, 47) also wrote that “nations as a natural, God-given way of classifying men, as an inherent though long-delayed political destiny, are a myth; nationalism, which sometimes takes preexisting cultures and turns them into nations, sometimes invents them, and often obliterates preexisting cultures: that is a reality.” Hobsbawm (Reference Hobswawm1992, 14) himself not only argued that “the basic characteristic of the modern nation and everything connected with it is its modernity,” but that “the opposite assumption, that national identification is somehow so natural, primary and permanent as to precede history, is … widely held.” Hobsbawm (Reference Hobswawm1992, 54) took a similar position on the supposedly primordial criteria of nationalism, suggesting for example that “national languages are … almost always semi-artificial constructs and occasionally, like modern Hebrew, virtually invented. They are the opposite of what nationalist mythology supposes them to be, namely the primordial foundations of national culture.”

I consider modernism theory not only surprising but correct, and place myself firmly in the modernist school. Scholars of nationalism who remain skeptical or unpersuaded, however, rarely call themselves primordialists. Perhaps the most popular alternative is something called “ethnosymbolism,” an approach whose “founding father,” according to leading historiographer of nationalism theory Umut Özkırımlı (Reference Özkırımlı2003, 341), is Anthony D. Smith (1939–2016). A prominent and widely cited scholar, Smith wrote several books on nationalism; he also founded and edited the prestigious journal Nations and Nationalism.

Not all skeptics of modernization theory gather under Smith’s ethnosymbolist banner. Some scholars, including Smith (Reference Smith2010, 53–54) perceive an alternate approach called “perennialism” (Özkırımlı Reference Özkırımlı2003, 50–51, 58, 66–67; Spencer and Wollman Reference Spencer and Wollman2002, 27; Connor Reference Connor and Leoussi2006, 20–21). Other scholars prefer their own buzzwords: Walker Connor (Reference Connor1994), for example, formulated his approach as “ethnonationalism.” Several political scientists posit a tripartite theoretical division between “primordialism, instrumentalism, and constructivism,” (Young Reference Young and Young1993, 21–25; Tilley Reference Tilley1997; Muro Reference Muro, Porta and Diani2015, 186–191). Notoriously, the literature cataloging and classifying the various theories of nationalism is voluminous, and grows ever more lengthy (Özkırımlı Reference Özkırımlı2003; Ichijo and Uzelac Reference Ichijo and Uzelac2005; Lawrence Reference Lawrence2005; Kuzio Reference Kuzio2007).

Smith’s contrast between modernism and ethnosymbolism nevertheless enjoys a unique position in the historiography. Ephraim Nimni (Reference Nimni, Breen and O’Neill2010, 21) thought the “two main conceptual frameworks that dominate the study of nationalism” are “modernism and ethnosymbolism,” and several scholars have described nationalism theory as a debate between “modernists and ethnosymbolists” (Hutchinson Reference Hutchinson2005, 33; Uberoi Reference Uberoi2007, 149; Murray Reference Murray2015, 36). Let us then consider the origins of nationalism in terms of these two schools.

Smith’s Critique of Modernism Theory

Smith spent most of his career criticizing modernism theory in fairly strident terms. Though he started off, in his own phrase, as “a slightly unconventional modernist” (Hall Reference Hall2016, 16), he began attacking modernism in his 1986 The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Thereafter, I suggest, Smith’s voluminous works on nationalism can be analyzed as a single and somewhat repetitive corpus. Indeed, in an interview shortly before his death, Smith denied that he would ever “have a ‘third period’ or whatever the people like to do” (Hall Reference Hall2016, 17–18).

Smith objected to modernism because he emphasized the importance of traditions from pre-modern times. He objected to the “basic premise that nations were ‘modern,’” perceiving the roots of nationalism in the Middle Ages or, as suggested by the title of his The Antiquity of Nations (2004), even in ancient times. He thought scholars should look at “not merely the processes of modernization, but also to earlier pre-modern identities and legacies that continue to form the bedrock of many modern nations” (Smith Reference Smith1995, 47). “By and large,” Smith (Reference Smith2009, 30) argued, “nations tend to emerge, as we shall see, over long time spans through the development of particular social and symbolic processes … nations are also constituted by shared memories, values, myths, symbols, and traditions.” Smith (Reference Smith2009, 32) emphasized the “need to take into account pre-existing traditions, memories and symbolism among non-elites,” arguing that “a realistic account” of nationalism must start with “its ethnic past, with the memories, myths, symbols and traditions of cultural communities” (Smith Reference Smith1995, 47), since “we best grasp the character, role, and persistence of the nation in history if we relate it to the symbolic components and ethnic models of earlier collective identities (Smith Reference Smith2000, 77). Smith’s emphasis on the symbols of a pre-modern ethnic past explains the term “ethnosymbolism.”

The core of ethnosymbolism, and Smith’s main contribution to nationalism theory, is the concept of an ethnie, a French word Smith (Reference Smith2000, 65) usually preferred to the English alternative “ethnic community.” The ethnie is Smith’s catchall term for the pre-modern basis for the nation. He described “nations being based on, and being created out of, pre-existing ethnies” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 196). He conceded that “nationalism is part of the ‘spirit of the age,’” (meaning the “modern” age), but insisted nevertheless that “it is equally dependent upon earlier motifs, visions and ideals … it is impossible to grasp its impact on the formation of national identity without exploring its social and cultural matrix, which already owed so much the presence of pre-modern ethnies” (Smith Reference Smith1991, 71–72). Smith’s ethnie, in effect, is something pre-national, and thus non-national, that transforms into a nation. The transformation ethnie → nation forms the essence of Smith’s theory: the ethnie is the tadpole to the national frog.

Smith’s ethnosymbolism differs from straightforward primordialism, I suggest, only insofar as the ethnie differs from the nation. Primordialism posits old, premodern nations, Smith’s ethnosymbolism posits old, premodern ethnies that transform into nations. To whatever extent the equation ethnie = nation holds, to that extent the transformation ethnie → nation collapses indistinguishably into primordialism.

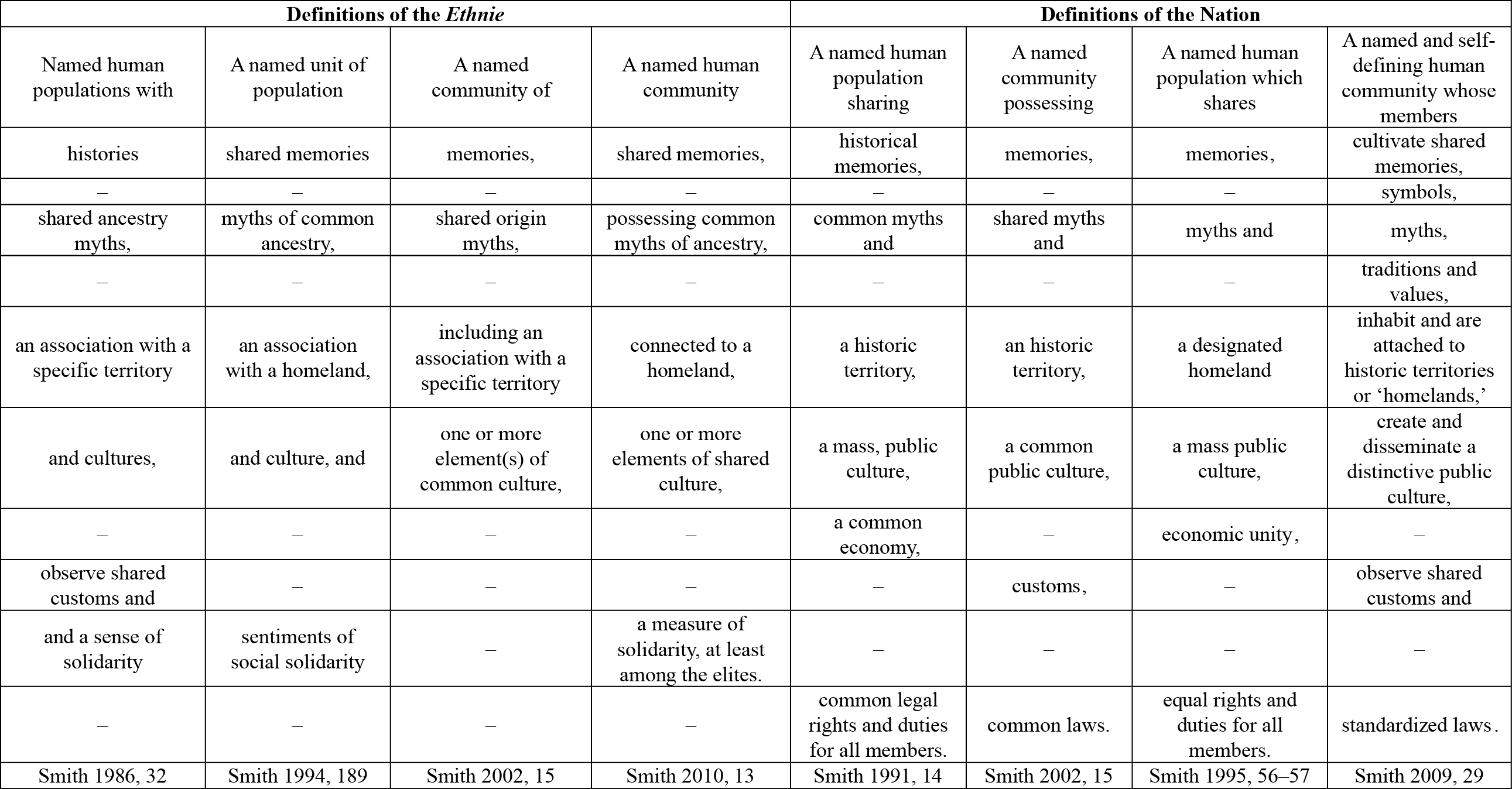

How, then, did Smith distinguish the nation from the ethnie? A precise answer is complicated, because Smith proposed many different definitions for both terms over the course of his career. I nevertheless suggest that Smith’s various definitions resemble each other closely. Figure 1 compares four of Smith’s different definitions of the nation, and four of his different definitions of the ethnie. To facilitate comparison I have sometimes rearranged the order of clauses, which means that some definitions no longer read correctly within an individual column. However, I have always retained Smith’s exact wording.

Figure 1. The Arctic route through Moscow to the North, 2015–2016.

Some similarities are undeniable. Smith (Reference Smith2009, 29, 30) himself acknowledged that his definition of the nation “overlaps to some extent with the definition of ethnie,” and specifically “in respect both of naming and self-definition and of the cultivation of shared symbols, myths, values and traditions.” Smith (Reference Smith2002, 16) elsewhere admitted that “the line between ethnies and nations cannot be drawn too sharply.” The extensive overlap, Smith thought, demonstrated the “significant and often close relationship between ethnic communities and nations” (Smith Reference Smith2009, 30).

The only consistent difference appears at the bottom of the chart. Smith defined the ethnie through “a sense of solidarity” (Smith Reference Smith1986, 32), “sentiments of social solidarity” (Smith Reference Smith1994, 189) and “a measure of solidarity, at least among the elites” (Smith Reference Smith2010, 13), but the nation in terms of “legal rights and duties” (Smith Reference Smith1991, 14), “equal rights and duties” (Smith Reference Smith1995, 57) and “standardized laws” (Smith Reference Smith2009, 29).

The transformation from “solidarity” to legal rights and laws comes close to equating the ethnie → nation transformation with the foundation of a state, though Smith, admittedly, often had the example of Jewish religious law in mind. If taken literally, Smith’s definitions imply that state collapse would transform a nation back to an ethnie, and thus that Poland ceased to be a nation for the duration of Nazi occupation. Smith’s own work contradicted such a definition. In his attempt to devise a typology of nationalism, for example, Smith (Reference Smith1983, 223, 228) perceived the absence of “independence, i.e. de facto sovereignty” in eight different sorts of nationalism; specifically, colonial heterogeneous nationalism, colonial cross-cultural nationalism, “mixed” nationalism, ethnic succession nationalism, ethnic secession nationalism, ethnic diaspora nationalism, ethnic irredentism, and ethnic pan-nationalism.

Some readers may find the gap between Smith’s ethnie and Smith’s nation compelling. Others may find the difference between his different definitions of the nation equally compelling. Montserrat Guibernau (Reference Guibernau2004, 129), for example, characterized the shift from “common legal rights and duties” to “common laws and custom” as a “significant change.” I am, however, mostly struck by continuity. Indeed, I suggest that the diversity in wording or criteria between the Smith’s various definitions for the nation, or between his various definitions of the ethnie, is similar to the difference between his nation and his ethnie.

Smith repeatedly criticized modernism theory for its disinterest in the ethnie. For example, Smith (Reference Smith1995, 47) attacked modernists for “their refusal to link the consequences of modernity with an understanding of the continuing role played by cultural ties and ethnic identities which originated in pre-modern epochs.” He proclaimed “a greater continuity between pre-modern ethnies and ethnocentrism and more modern nations and nationalism than modernists of all kinds have been prepared to concede” (Smith Reference Smith1991, 52), and thought “modernist approaches critically undervalue the local cultural and social contexts” (Smith Reference Smith1995, 42). Indeed, he once attacked modernism for not replicating his own “ethnie → nation” model: “Modernist theories such as Gellner’s,” Smith (Reference Smith1998, 46) argued, “fail to account for the historical depth and spatial reach of the ties that underpin modern nations because they have no theory of ethnicity and its relationship to modern nationalism.” Yet insofar as the ethnie closely resembles the nation, to that extent Smith was in effect criticizing modernists for rejecting primordialism.

In addition to propounding a pre-modern ethnie that closely resembles the modern nation, however, Smith also described an ethnie → nation transformation that strikingly resembles modernist theories of nationalism. For example, Smith (Reference Smith1983, 191) suggested “it was only after the French Revolution that … the total population, and not just the aristocrats and clergy, now constituted the ‘nation,’ the sole fount of legitimacy and authority.” When Smith (Reference Smith1998, 126) argued that “the period from 1790 to 1820 saw the formation and dissemination of nationalist ideas throughout Europe and the Americas,” he proposed a modernist chronology.

One can often juxtapose a “modernist” Smith with a “primordialist” Smith. Note that Smith’s modernist side and his primordialist side do not come together to form a synthesis, or even a middle ground: they simply contradict each other. Modernist Smith (Reference Smith1995, 58) admitted that “the evidence for pre-modern nations is at best debatable and problematic,” but primordialist Smith (Reference Smith2000, 65) invoked “the premodern continuities of at least some nations” [emphasis in original]. Primordialist Smith (Reference Smith1995, 39) once condemned modernism’s alleged “instrumentalist approach” for supposedly failing “to account for the dynamic, explosive, sometimes irrational nature of ethno-national identity,” elaborating that “‘Rational choice’ theory has sought to overcome this difficulty in terms of rational individualist strategies of maximizing public goods for the culturally defined population, but it still comes up against the uneven, explosive angular quality of so much ethnonationalism.” Just a few pages previously, however, modernist Smith (Reference Smith1995, 34) had rejected primordialism on the grounds that “ethnic solidarities are often the result of perfectly rational strategies of benefit maximization on the part of individuals.” Smith’s work, in short, straddles contradictory positions; it is in turn both critical of modernism and indistinguishable from it.

Even in his intermittent modernist moods, however, Smith consistently attacked modernist theorists, modernist jargon, modernist buzzwords, and modernism as a school of thought in nationalism studies. While Smith often distanced himself from primordialism by propounding ideas indistinguishable from modernism, the overall tenor of Smith’s work remains stridently critical of modernism. He wrote book chapters with titles like “The Modernist Fallacy” (Smith Reference Smith1995, 29–50), “Beyond Modernism?” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 199–220), and “the Myth of the ‘Modern Nation’” (Smith Reference Smith2004, 33–61). Why, then, does Smith take such a consistently hostile stance toward modernism?

Smith’s corpus on nationalism is too voluminous to analyze line by line, but one can usefully analyze Smith’s hostility to modernism through his engagement with prominent modernist scholars. Smith often presented his thoughts in contrast to those of other theorists; several of his books take a frankly historiographical approach (Smith 1993; Smith Reference Smith1996; Smith Reference Smith2000). Let us concentrate on two prominent scholars that Smith (Reference Smith1998, 220) himself identified as key figures in modernist nationalism theory: Benedict Anderson (1936–2015) and Eric Hobsbawm (1917–2012).

Smith and the “Imagined Community”

Benedict Anderson’s reputation as a nationalism theorist rests on his 1983 masterwork Imagined Communities, cited here from a revised edition first published in 1991. This classic of western Marxist thought pursues many provocative arguments and resists concise summary. Most readers of this journal, however, are probably familiar with the book already. As noted during a 2016 symposium devoted to Anderson’s work, Imagined Communities is “the fifth-most cited book in the social sciences and by the far most cited text in the study of nationalism,” boasting “about 64,000 citations to date (May 2016) on Google Scholar” (Breuilly et al. Reference Breuilly2016, 626). Indeed, it boasted more than 96,000 Google Scholar citations as of June 2019.

In light of Smith’s insistence that modern nations have pre-modern roots, it is perhaps worth emphasizing that Anderson (Reference Anderson1991, 37–44; 12–22) not only discussed the role of pre-modern linguistic culture at some length, but also, in a chapter on “cultural roots,” argued that “nationalism has to be understood by aligning it … with the large cultural systems that preceded it,” namely “the religious community and the dynastic realm [emphasis in original].” Anderson (Reference Anderson2001, 33) subsequently recalled that “One of the central arguments of my book Imagined Communities is that nationalisms of all varieties cannot be understood without reflecting on the older political forms out of which they emerged: kingdoms, and especially empires of the pre-modern and early modern sorts.” As Özkırımlı (Reference Özkırımlı2003, 342) noted in his own critique of Smith, Anderson “devotes more than half of his Imagined Communities to the historical conditions that gave rise to nations and nationalism.” So if Smith (Reference Smith2000, 58) argued that “Anderson overplays the ruptures with premodern societies and cultures [emphasis added],” he advocated at most a shift of emphasis.

Since, as Thomas Eriksen noted, “many of those who quote Anderson … seem not to have made it beyond the title” (Breuilly et al. Reference Breuilly2016, 28), it deserves emphasis that, despite popular misconception, Anderson did not define the nation as an “imagined community.” Instead, he proposed “the following definition of the nation: it is an imagined political community—and imagined as both as inherently limited and sovereign.” He devoted a paragraph to four elements of this definition. Anderson’s nation is (1) imagined “because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.” Anderson’s nation is (2) limited because it has borders: “the most messianic nationalists do not dream of a day when all the members of the human race will join their nation in the way it was possible … for, say, Christians to dream of a wholly Christian planet.” Anderson’s nation is (3) sovereign because its rise occurred when “Enlightenment and Revolution were destroying the legitimacy of the divinely-ordained hierarchical dynastic realm.” Anderson’s nation, finally, is (4) a community because of its “deep, horizontal comradeship” (Anderson Reference Anderson1991, 5–7).

Anderson’s ruminations about how a community is “imagined” have profoundly influenced scholarship on nationalism. Spencer and Wollman (Reference Spencer and Wollman2002, 37) rightly noted “it has become one of the commonest clichés of the literature, although invocation has, in some cases, been a substitute for analysis.” If the word “imagined” has become an almost technical term in nationalism studies, its popularization may have been Anderson’s most far-reaching contribution to the field.

Scholars have, by contrast, not always appreciated the great insight Anderson showed by defining the nation as “limited.” Scholars considering possible definitions of nationalism have long struggled with the phenomenon that different nationalists emphasize different criteria when defining nationhood. Armenian and Albanian nationalists cultivate myths of common descent in ways that American and Australian nationalists do not; religion plays a more central role for Iranian, Irish, and Israeli nationalists than for their Canadian or Chinese counterparts; Slovak and Somali nationalists emphasize a shared language where Swiss and South African nationalists celebrate linguistic plurality. Individual nationalists may even posit exotic criteria relevant only to a particular cultural context. Serbian geographer-patriot Spiridion Gopčević (Reference Gopčević1889, 18) once defined the Serbs through the krsno ime, a celebration of baptismal names: “we Serbs, alone … celebrate the krsno ime. Whoever celebrates it may ten times proclaim that he is Bulgarian or Chinese – the krsno ime gives him away!” The diversity and instability of possible criteria explains why, as Sutherland (Reference Sutherland2012, 9) put it, “theorists mostly agree that it is pointless to try to identify an objective ‘checklist’ of nationhood criteria.” By refusing to endorse any particular checklist, however, Anderson’s definition not only encompasses nations imagined through different criteria, but directs attention to the various criteria of inclusion and exclusion as profitable sites of comparative analysis.

Smith treated this great strength of Anderson’s definition as a weakness. Anderson’s definition, Smith (Reference Smith1998, 138) asserted, “has no room for … criteria like ethnicity, religion, or colour.” Overlook, for a moment, that Anderson’s definition actually encompasses these criteria and consider Smith’s subsequent conclusion:

This means that, provided it is political, finite, and sovereign, any imagined community—be it a city-state, a kingdom or even a colonial empire with a single lingua franca—can be designated by its members as a nation. For a definition of the nation, this is rather too large a trawl of political communities for comfort.

I suggest, on the contrary, that the ability of Anderson’s definition to encompass such diverse political communities shows its value. Evidence of “nationalism” in city-states, kingdoms, and colonial empires, furthermore, is easily gathered. Several scholars have, for example, studied nationalism adhering to the city-state of Singapore (Hill and Lian Reference Hill and Lian2013; Han Reference Han2013; Lau Reference Lau, Frey and Pruessen2015); or to imperial states united by a lingua franca, such as the British Empire (Wellings Reference Wellings2002; Kutzer Reference Kutzer2002; Thompson 2014) or the Soviet Union (Tromley 2009; Fragner Reference Fragner2001; Tromly, Reference Tromly2009; Nikonova Reference Nikonova2010). Thinking of a kingdom “designated by its members as a nation” could be left as an exercise for the reader, but it might be more useful to pose a challenge instead: can readers think of any kingdom that during the last 100 years has not been “designated by its members as a nation?”

Smith elsewhere objected the study of the imagination because he could perceive no link between imagination and political action. “The nation,” he argued, “is not only known and imagined: it is also deeply felt and acted out” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 137). Özkırımlı (Reference Özkırımlı2003, 348) has eloquently rebutted this particular objection: “The fact that something is constructed or imagined does not make it less real in the eyes of those who believe in it … The fact that our feelings are the products of some complicated cognitive processes does not make them less real to us.”

Many of Smith’s objections to the “imagined community” rebut straw men. Smith (Reference Smith2009, 12) summarized the “imagined community” as a “discursive formation of linguistic and symbolic practices” (Smith Reference Smith2009, 12),” and criticized Anderson’s “excessive emphasis on the idea of the nation as a narrative of the imagination” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 138). Anderson’s book in practice analyzed the interaction of capitalism with printing technology and the career aspirations of subaltern bureaucrats. Indeed, Smith (2010, 86), after objecting that for Anderson “nationalism is mainly a form of discourse,” conceded in the following sentence that in Anderson’s work “nations are based on vernacular ‘print communities,’ that is, reading publics of vernacular print-languages and literatures,” which were in turn “nourished by the rise of the first mass commodity, printed books.” How can the rise of a mass market for books, or the spread of literacy in vernacular print-languages, be characterized as “mainly a form of discourse?”

Over the course of his work, Smith frequently criticized Anderson on contradictory grounds. Smith once alleged that Anderson’s approach means “the nation possessed no reality independent of its images and representations,” objecting that “such a perspective undermines the sociological reality of the nation” (1998, 137). Yet he elsewhere admitted that Anderson “explores literary texts to establish the sociological content of the imagined community that they evoke” but “does not enquire into the visions of the nation, or the ideologies of self-determination” (Smith Reference Smith2009, 83). He thus criticized Anderson both for emphasizing “images” at the expense of “sociological reality,” but also for studying “sociological content” at the expense of “visions” and “ideologies.” Smith (2010, 87) elsewhere proclaimed that nations “are as much communities of emotion and will, as of imagination and cognition,” while simultaneously acknowledging—in the same paragraph!—that Anderson addressed the “problem of passion and attachment to the nation.” The only constant feature in Smith’s analysis appears to be his tone of disapproval.

Indeed, Smith even managed to project disapproval when he agreed with Anderson. In one curious two-sentence passage, Smith (Reference Smith2000, 59) presents Anderson’s definition as a rebuttal to Anderson’s definition: “It is, of course, perfectly true that the nation as a community of people, most of whom will never know or meet one another, is an imagined community. But, as Anderson points out, so is every community above the face-to-face level.” Smith here proclaimed Anderson’s correctness in two consecutive sentences, but somehow presents concordance as a criticism. Anderson’s full definition, of course, answers the implicit objection: Anderson, recall, did not claim all “imagined communities” were nations, he specified the additional criteria “inherently limited” and “sovereign.” Indeed, it seems possible that Smith had actually read Anderson’s criteria carefully, but assumed his readers would only remember the famous words in Anderson’s book title. If so, then this particular objection to Anderson’s thought rests on a deliberate misrepresentation.

The issue of deliberate misrepresentation arises elsewhere in Smith’s critique of Anderson. According to Smith (Reference Smith1998, 141), “the modernist framework employed by Anderson is in need of considerable revision, especially in its tendency to over-generalize from the Western experience.” Many nationalism theorists have indeed overgeneralized from the Western experience, but Anderson, a specialist in southeast Asia, if anything overgeneralized from southeast Asia. To explain the new mental worlds imagined in the novel and the newspaper, Anderson cited Philippine and Indonesian authors. To illustrate the importance of maps, he discussed Thailand. To discuss the importance of census categories, he considered Malaysia, British India, the Philippines, and Indonesia. South American creoles also play an unusually prominent role in his overall narrative. While his account of “official nationalism” considers Germany and Britain, he analyzes Britain partly from the Indian perspective, and then discusses Japan at greater length.

Smith not only attacked Anderson for things he pretended Anderson wrote, he also criticized things he himself admitted Anderson did not write. “Anderson’s synthesis is only partly successful,” Smith claimed, because it “can always be detached from its modernist moorings. In the hands of his followers, this is what has tended to happen” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 142). Anderson is here held responsible for unnamed and uncited scholars who drew inspiration from Imagined Communities, scholars elsewhere characterized as “the many theorists in the postmodernist traditions who have drawn inspiration from a partial reading of Anderson’s work” and “the many postmodernist writers influenced by his vision” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 142). Smith also rejected the phrase “imagined community” because the term may be used “in just those senses from which Anderson wishes to distance himself: it is so easy to slide from ‘imagined’ in the sense of ‘created’ to ‘imaginary’ in the sense of ‘illusory’ or ‘fabricated.’” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 137). I suggest that no scholars can be held responsible for wayward disciples, much less for ideas from which they consciously distance themselves.

Overall, then, Smith criticized an inaccurate caricature of Anderson’s work without engaging seriously with Anderson’s actual arguments. His criticism rests on misrepresentation, contradictions, and a certain unignorable bad faith. The interesting question, however, concerns motive. Smith’s stated objections to Anderson make little sense, yet something about his work clearly rubbed Smith the wrong way. Why did Smith devise this avalanche of specious arguments? What in Anderson provoked such distaste? The conclusion will address this central question, but for now note that a conflict of personality appears an unlikely explanation, since Smith’s critique of Hobsbawm suffers from similar weaknesses.

Smith, the “Invented Tradition,” and “Proto-Nationalism”

While Eric Hobsbawm is perhaps best remembered for a three-volume history of Europe during the “long nineteenth century,” his reputation in nationalism theory rests on his 1991 Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality and on an 1983 volume co-edited with Terence Ranger, The Invention of Tradition. The idea of “invented traditions” struck quite a chord among nationalism scholars. Much as Anderson introduced the word “imagined,” Hobsbawm and Ranger popularized the word “invented” as a shorthand for the processes of social construction.

In the introduction to The Invention of Tradition, Hobsbawm (Reference Hobsbawm, Hobsbawm and Ranger1983, 1) defined the “invented tradition” as follows:

‘Invented tradition’ is taken to mean a set of practices, normally governed by overtly or tacitly accepted rules and of a ritual or symbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behaviour by repetition, which automatically implies continuity with the past. In fact, where possible, they normally attempt to establish continuity with a suitable historic past.

Note how Hobsbawm accepted the possibility of continuity with a “suitable past,” even if he also insisted that “the historical past into which the new tradition is inserted need not be lengthy, stretching back into the assumed mists of time” and that “insofar as there is such reference to a historic past, the peculiarity of ‘invented’ traditions is that the continuity with it is largely factitious” (Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm, Hobsbawm and Ranger1983, 2).

Where Smith stressed the importance of continuities, Hobsbawm was largely indifferent. Hobsbawm (Reference Hobsbawm, Hobsbawm and Ranger1983, 7) consciously chose not to investigate “how far new traditions can … use old materials, how far they may be forced to invent new languages or devices, or extend the old symbolic vocabulary beyond its established limits.” Instead, Hobsbawm (Reference Hobsbawm, Hobsbawm and Ranger1983, 2) focused on the contrast “between the constant change and innovation of the modern world and the attempt to structure at least some parts of social life within it as unchanging and invariant.” Hobsbawm’s focus on the moment of invention or reinvention led him to emphasize “the break in continuity which is sometimes clear even in traditional topoi of genuine antiquity” (Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm, Hobsbawm and Ranger1983, 7).

Smith objected to the term “invented tradition” partly on the grounds that the term “often carries connotations of fabrication and/or creation ex nihilo—something that Hobsbawm is at pains to repute” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 130). Once again, Smith here objected not to Hobsbawm’s actual argument, but rather to his own deliberate misreading of Hobsbawm. As with his critique of Anderson’s “imagined community,” furthermore, Smith attacked a deliberate misreading that, according to Smith himself, Hobsbawm specifically repudiated.

Addressing the “the notion of ‘invention,’” Smith (Reference Smith1998, 140) elsewhere argued that the nation “is not only an abstraction and invention, as is so often claimed. It is also felt, and felt passionately, as something very real, a concrete community, in which we may find some assurance of our own identity and even, through our descendants, of our immortality.” Smith (Reference Smith2010, 88) also found “Hobsbawm’s analogy … patently mechanistic; nations are constructs or fabrications of social engineers, like technical inventions. They are planned and put together by elite craftsman. There is no room for emotion or moral will.” The logic of this strange argument wrongly presupposes that social constructs cannot be felt passionately, and that things felt passionately cannot be socially constructed.

Smith, in a primordialist mood, argued that only political structures can be “invented,” not nations themselves. Even when discussing emerging nationalisms in the African and Asian colonies of European powers, Smith (Reference Smith1998, 130) argued that mobilization “generally proceed on the basis of memories myths, symbols and traditions of the dominant ethnie … on the basis of the pre-existing culture of the dominant ethnic community.” Smith concluded “the element of ‘invention,’ where it exists, is therefore confined to the political form of that reconstitution, and is misleading when it is applied to the sense of cultural identity which is the subject of reinterpretation” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 131).

Elsewhere, however, modernist Smith conceded the invention of culture, and thus the heart of Hobsbawm’s argument, but maintained his disapproving tone while making these concessions. Smith (Reference Smith1998, 129) insisted upon analyzing “the complex interweaving of relationships between old and new cultural traditions, something that Hobsbawm and Ranger’s concept of ‘invented traditions’ ignores or simplifies,” yet in the immediate following sentence conceded that “it is certainly true, as Hobsbawm and his associates underline, that modern elites and intellectuals deliberately select and rework old traditions, so that what appears today under the same banner is very different from its ostensible model.” What distinguishes “interweaving old and new cultural traditions” from “selecting and reworking” them?

As in his analysis of Anderson, then, Smith proposed at most a slight shift of emphasis. “To see nations as composed largely of ‘invented traditions,’ designed to organize and channel the energies of the newly politicized masses,” Smith (Reference Smith1998, 130) argued, “places too much weight on artifice and assigns too large a role to the fabricators” [emphasis added]. When Smith (Reference Smith1991, 71) argued “nations and nationalism are no more ‘invented’ than other kinds of culture, social organization or ideology,” he in effect admitted that they are invented, though he again presented concurrence as a disagreement.

As it happens, Hobsbawm, like Anderson, emphasized that nationalism had pre-modern roots, analyzing them under the heading of “proto-nationalism.” In Nations and Nationalism, Hobsbawm (Reference Hobswawm1992, 46–47) grouped “proto-national bonds” under two main headings:

First, there are supra-local forms of popular identification which go beyond those circumscribing the actual spaces in which people passed most of their lives: as the Virgin Mary links believers in Naples to a wider world … Second, there are the political bonds and vocabularies of select groups more directly linked to states and institutions, and which are capable of eventual generalization.

Hobsbawm discussed several “supra-local” forms of popular identification, including language, ethnicity, and race, before concluding that “the consciousness of belonging or having belonged to a lasting political entity” was most important (Hobsbawm Reference Hobswawm1992, 51–63, 63–66, 66–73, 73–76).

Hobsbawm’s “proto-nationalism” superficially resembles Smith’s ethnie in that both predate nationalism proper. The two concepts nevertheless differ in that Smith posited a much more direct relationship between the ethnie and the nation. Smith assumed an ethnie → nation transformation by default. Hobsbawm (Reference Hobswawm1992, 77) knew that “existing symbols and sentiments of a proto-national community could be mobilized behind a modern cause,” yet explicitly denied “that the two were the same, or even that one must logically or inevitably lead into the other.”

Perhaps geographic extent most strikingly illustrates the difference between Hobsbawm’s “proto-nationalism” and Smith’s ethnie. Sticking with Hobsbawm’s Neapolitan example, quoted above, the wider world implied by the Virgin Mary extends to Christendom, or, at least, to world Catholicism. As Hobsbawm (Reference Hobswawm1992, 72) put it, “the Virgin Mary is difficult to confine to any limited sector of the Catholic world.” In Naples, the “political bonds linked to states and institutions” would meanwhile evoke the Bourbon and/or Habsburg monarchies, with their courts in Madrid or Paris. Since the geographic extent of such proto-national communities does not anticipate Italian nationalism, Hobsbawm (Reference Hobswawm1992, 47) thus rightly denied that such proto-nationalist loyalties “can be legitimately identified with the modern nationalism that passes as their lineal extension, because they had or have no necessary relationship with the unit of territorial political organization which is a crucial criterion of what we understand as a ‘nation’ today [emphasis in original].” Hobsbawm, observe, accepted that some relationship between proto-nationalism and nationalism was possible: “existing symbols and sentiments of proto-national consciousness could be mobilized behind a modern cause.” He merely denied “that the two were the same, or that one must logically or inevitably lead into the other” (Hobsbawm Reference Hobswawm1992, 77).

Smith criticized Hobsbawm by attacking an oversimplified misrepresentation of Hobsbawm’s arguments. Smith criticized “those who, like Hobsbawm, recognize the importance of ‘proto-national’ communities and sentiments … yet refuse to connect them in any way with subsequent modern political nationalisms [emphasis added] (Smith Reference Smith1995, 40).” In his survey of modernism theory, Smith (Reference Smith1998, 129) claimed Hobsbawm had “precluded an account based on pre-existing ethnic ties (‘proto-national’ bonds) [emphasis added].” Hobsbawm’s approach, according to Smith, “is to reject in advance any links between the ‘proto-national bonds’ of the masses, whether regional, religious or linguistic, and modern nationalisms” [emphasis added] (Smith Reference Smith2010, 88), though Smith admittedly also conceded that “Hobsbawm does not deny the importance of old traditions adapting to meet new needs” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 118). While Smith (Reference Smith2000, 33) once grudgingly acknowledged that Hobsbawm discussed “cultural traditions of community—regional, religious, or linguistic,” he still insisted that for Hobsbawm “these proto-national bonds are irrelevant to the subsequent modern political movement of nationalism” and “cannot be regarded in any sense [!] as ancestors or progenitors of nationalism ‘because they have no necessary relation with the unit of territorial political organization.’” Where Hobsbawm proclaimed “no necessary relationship,” in short, Smith read and criticized “no possible relationship.”

Only in his 2008 Cultural Foundations of Nationalism did Smith acknowledge the qualifier “necessary,” and thus the nuance of Hobsbabwm’s thought. Smith (Reference Smith2008, 108) depicted that nuance as a concession that undermined Hobsbawm’s argument:

Hobsbawm, in his Nations and Nationalism since 1780, after telling us that ‘proto-national’ bonds of region, language and religion have no necessary connection with the rise of the modern territorial state, admits that membership of a historic state … may act directly upon ‘the consciousness of the common people to produce proto-nationalism.’

It remains unclear why Smith perceived a contradiction between Hobsbawm’s “no necessary connection” and Hobsbawm’s “may act.”

In his more modernist moods, however, Smith acknowledged that some pre-modern ethnies fail to become nations, the very position he found so objectionable when articulated by Hobsbawm. Smith (Reference Smith1995, 57) specifically wrote that “many earlier ethnies disappeared, or were absorbed by others or dissolved into separate parts,” suggesting only that “some ethnic ties have survived from pre-modern periods, at least among some segments of given populations, and these have often become the bases for the formation of latterday nations and nationalist movements.” In a later work, he suggested that it “is, then, not difficult to show nations being based on, and being created out of, pre-existing ethnies. At least, some nations. There is, of course, no necessity about this transformation; otherwise nationalism and nationalists would be superfluous” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 196). Where primordialist Smith denounced Hobsbawm’s “protonationalism,” modernist Smith claimed it was identical to his own ethnie, suggesting that “Hobsbawm has overlooked the possibility that his popular ‘proto-national’ bonds are, in fact, the very ethnic ties that he dismissed as a basis for nations” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 128). The gap between Smith and Hobsbawm here vanishes almost entirely.

In the context of nationalism theory, however, Smith’s ethnie differs significantly from Hobsbawm’s “proto-national bonds:” the ethnie very closely anticipates the nation into which it eventually transforms. As noted above, Hobsbawm’s proto-national bonds generally fail to coincide with subsequently imagined national territories. By contrast, Smith linked the ethnie to the territory of the future nation. He defined the ethnie to include “an association with a specific territory” (Smith Reference Smith1986, 32), or “an association with a homeland” (Smith Reference Smith1994, 189), or, alternatively, that ethnies “are usually connected to a particular territory, even if they do not reside in it” (Smith Reference Smith2010, 12–13). Smith (Reference Smith1991, 70) also insisted that nations possess “long associations with particular stretches of territory.” Insofar as the territory of the ethnie is the territory of the nation, the equation ethnie = nation holds, and Smith’s theories collapse into primordialism.

As noted above in Figure 1, Smith defined the ethnie in terms of many criteria, not only on the basis of a territory or homeland. Smith sometimes conceded that these other elements too might be socially constructed, but presented this concession reluctantly and with qualification:

In arguing against social constructionism and invention as valid categories of explanation, I do not mean to deny the many instances of attempted ‘construction’ and ‘fabrication.’ My point is only that, to be successful, these attempts need to base themselves on relevant pre-existing social and cultural networks”

(Smith Reference Smith1998, 130).Smith’s final point, however, raises an important methodological question: how can scholars know which preexisting networks are “relevant?”

Smith’s assumption that some ethnie “generally” lies behind nationalism shows why his approach is less helpful than straightforward modernism. Hobsbawm’s Neapolitan example reminds us that relevant pre-existing social and cultural networks might not coincide with the future nation: Hobsbawm encourages us to look for surprising discontinuities, helping us see what we might not otherwise see. Smith’s theory, by contrast, offers a comforting reassurance that an ethnie existed in the pre-modern past, coinciding nearly exactly with the nation, simply waiting for the right moment to transform into a nation. Both Hobsbawm and Smith acknowledge continuity with pre-national structures, but Smith emphasizes precisely those sorts of continuities a naïve primordialist would expect to find. His theory is not surprising: it conceals the surprising insights of modernization theory in order to highlight the obvious.

Ethnosymbolism as Theoretically-Respectable Primordialism

By emphasizing continuities between modern nations and their pre-modern predecessors, Smith lacks originality. Despite Smith’s insinuations and misrepresentations to the contrary, modernists have repeatedly analyzed such continuities. As Özkırımlı (Reference Özkırımlı2003, 342) noted, “very few theorists claim explicitly that the nation has been created ex nihilo and that nothing like it existed before.” On matters of substance, Smith offers at most a small shift in emphasis in contrast to modernism. His shift in emphasis, furthermore, lies in an unhelpful direction: he emphasizes unsurprising continuities and downplays surprising discontinuities.

Smith consistently criticized modernists, even for arguments he himself espoused, but mostly criticized misrepresentations of modernist thought. Even Smith (Reference Smith1998, 23) himself admitted his “ideal-type dichotomies” that he had “deliberately magnified the differences” between himself and his modernist opponents. Özkırımlı (Reference Özkırımlı2003, 342) observed that ethnosymbolists made their argument against modernists “partly by a misreading of the theories in question and partly by a conscious attempt to exaggerate the differences.” While Özkırımlı worried that “too much magnification may amount to distortion,” I find his criticism too restrained: Smith’s critique rests on bad faith. His thought also abounds in misrepresentations and contradictions. Indeed, the only constant feature in Smith’s work appears to be his desire to delegitimize modernism.

Why then did Smith choose to spend his scholarly life attacking a modernism he himself intermittently espoused? Career ambition provides one possible explanation. If Smith wagered he could more easily win a scholarly reputation as modernism’s gadfly than as its disciple, then his gamble certainly paid off. Such considerations, however, hardly suffice to explain an entire career. The interesting question, therefore, concerns Smith’s motive.

Smith offered a historiographical justification for his work: he presented ethnosymbolism as a corrective to the excesses of modernism, much as modernists presented their work as debunking mythical primordialism. Smith (Reference Smith2000, 27) lamented that “today’s dominant orthodoxy is thoroughly modernist,” and repeatedly attacked what he called the “dominant modernist paradigm” (Smith Reference Smith2000, 4; Smith Reference Smith2008, 182). He lamented both “the rising tide of modernism” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 18) and that “the main assumptions of modernism have been so firmly entrenched” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 145). He claimed to offer “a useful supplement and corrective to the dominant modernist orthodoxy” (Smith Reference Smith2008, xi), alternatively “a radical but nuanced critique of the dominant modernist orthodoxy” (Smith Reference Smith2009, 13). Indeed, Smith (Reference Smith1983, 41–64) might have meant the religious metaphor of “orthodoxy” literally: he once wrote a book chapter called “The Religion of Modernisation,” posing as a prophet casting down false idols.

The putative modernist orthodoxy, however, enjoys dominance mostly in Smith’s imagination. Modernism is not even hegemonic in academic circles. Even assuming for the sake of argument that most nationalism theorists are modernists, nationalism theorists are only a minority of scholars, and, as noted above, primordialism remains widespread in case study history writing. Indeed, Smith himself conceded the ubiquity of primordialism: he acknowledged that primordialism “is a common view among nationalists” (Smith Reference Smith1995, 31), arguing merely that modernism is “the most common belief in the field” (1995, 29). He elsewhere attacked modernism as “a semi-ideological account … that chimes with modern preconceptions and needs, especially with those of a mobile, universalist intelligentsia” (Smith Reference Smith1995, 41). Do more people, and more influential people, belong to the category “mobile, universalist intelligentsia,” or to the category “nationalists?”

Primordialism perhaps enjoys such overwhelming support in the world beyond academia not least because it dominates school curricula. Scholars studying textbooks have found “a primordialist, ethno-culturally essentialist vision of national identity” across east Asia (Vickers Reference Vickers, Lall and Vickers2009, 27), an “openly primordialist view” across the former Soviet Union (Shnirelman 2009, 117); and observed “the recourse to primordialism” in southeast Asia (Aguilar Reference Aguilar2017, 142). Jana Šulíková (Reference Šulíková2016, 30) reports that in Slovakia “self-evident application of the primordialist narrative … permeates all volumes of history textbooks.” Tomasz Kamusella (Reference Kamusella2010, 128) has similarly found “the myth of a centuries-long tradition of national statehood” ubiquitous in school atlases.

Furthermore, scholarship adopting a modernist perspective can arouse public vitriol. When Ronald Grigor Suny proposed “a more constructivist understanding of nationness in place of the primordialist convictions of the nationalists” at a Yerevan conference, the next day an angry crowd gathered outside the lecture hall to shout insults at him (Suny Reference Suny2001, 864). Irina Culic (Reference Culic2005, 13, 14), noting that in Romania “the public space and the political class are dominated by a primordialist understanding of the nation,” reported that textbooks containing “sections titled such as The Invention of the Modern Nation or Ethnogenesis: How Romanians Imagine the Origin of Their people” were ceremoniously burned in public by Romanian politicians. As Gellner (Reference Gellner1997, 92) rightly observed shortly before his death, “commonsense popular belief is on the side of the antiquity of nation.”

Perhaps the question of Smith’s motive is more psychological than historiographical. If, as Michael Oakshott (1962) argued, conservatism is “not a creed or a doctrine, but a disposition” inclined “to prefer the familiar to the unknown,” then perhaps Smith’s distaste for Anderson and Hobsbawm reflects a conservative’s suspicion of a surprising theory arising from Marxist analytical traditions. Smith’s work elsewhere reflects a conservative’s acceptance of nationalism. In a chapter written “in defence of the nation,” Smith (Reference Smith1995, 160) argued that nationalism alone offered “collective faith, dignity and hope,” as well as “collective but terrestrial immortality, outfacing death and oblivion.” He also articulated a personal loathing of cosmopolitanism:

A global culture is without time. Forever pursuing an elusive present, an artificial and standardized universal culture has no historical background, no developmental rhythm, no sense of time and sequence. Contextless and timeless, this artificial global culture … refuses to locate itself in history. Stripped of any sense of development [!] beyond the performative present, and alien to all ideas of ‘roots,’ the genuine global culture is fluid, ubiquitous, formless and historically shallow (Smith Reference Smith1995, 21–22).

A “truly non-imperial ‘global culture,’” he later wrote, “must be memory-less and hence identity-less, or fall into a postmodern pastiche of existing national cultures and so disintegrate into its component parts” (Smith Reference Smith1998, 195). Smith, in other words, wrote not just to understand nationalism, but to defend it. As Özkırımlı (Reference Özkırımlı2003, 339) put it, “ethnosymbolism is more an attempt to resuscitate nationalism than to explain it.”

Smith’s fundamental support for the nation perhaps explains his unshakable conviction that genuine loyalty could not adhere to an “imagined” or “invented” nation. As a conservative and as a nationalist, he personally conflated antiquity and authenticity. Though Smith (Reference Smith2000, 62) claimed that “constructionists … are unable to grasp and credit the emotional depth of loyalties to historical nations and nationalisms,” I suggest, on the contrary, that Smith was unable or unwilling, despite abundant counter-examples, to accept that recently constructed communities may inspire loyalties with emotional depth. He could not admit to himself that the object of his own veneration was socially constructed.

For theorists of nationalism, however, Smith’s ethnosymbolism remains functionally equivalent to primordialism. Smith read modernization theory deeply enough to appreciate how persuasively it had debunked primordialism, but did not want to accept its ramifications. He therefore spent the rest of his career intermittently conceding modernist arguments, attacking misrepresentations of modernist theory, and using the nearly national ethnie to restore primordialist antiquity. Thus ethnosymbolism was born.

Ethnosymbolism found a ready audience. Ubiquitous primordialist narratives provide a comforting sense of authenticity, and many emerging scholars are emotionally unprepared to acknowledge how recently cherished national tropes have been imagined or invented. Indeed, scholars aspiring to theoretical sophistication, particularly case study scholars emotionally connected to the particular national history they choose to study, often read the famous names of nationalism theory with dismay: the modernist chronologies of Anderson and Hobsbawm challenge and undermine deeply held personal convictions. Ethnosymbolism fills the resulting empty space with the ethnie, which for most purposes is functionally equivalent. Smith’s ethnie thus restores the comforting sense of antiquity that naïve primordialism once bestowed. Smith’s approach enjoys particular popularity among case-study scholars who do not specialize in nationalism because it satisfies the emotional gap that primordialism’s collapse has left behind. In this reading, Smith’s slightly modified primordialism caters to nationalism scholars who have already read the classics of modernization theory, and thus ought to know better.

Nevertheless, serious scholars who study ethnicity before the modern era can be forgiven a certain impatience with modernization theory. Hobsbawm worked on the “long nineteenth century,” and Anderson on the 20th. However insightful they may have been depicting the emergence of nationalism as discontinuity with pre-modern history, they remain modern historians studying problems in modern history, and devoted little attention to the problems of early modern or medieval history. If ethnosymbolism is debunked primoridialism, but modernization theory provides little guidance to pre-modern history, does nationalism theory have anything to offer medieval or early modern scholars?

Brubaker’s research agenda, however, transcends the chronological limitations of modernization theory. Though modernization theory argues that “nations” did not exist before the modern era, Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2000, 5) proposes that scholars should not study “nations” at all, but rather “appeals and claims made in the name of putative ‘nations.’” Brubaker asks not whether a nation exists, but how it functions socially “as a practical category, as classificatory scheme, as cognitive frame.” Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2004, 13) later generalized his insight in a memorable discussion of “categories:”

We can analyze the organizational and discursive careers of categories—the processes through which they become institutionalized and entrenched in administrative routines and embedded in culturally powerful and symbolically resonant myths, memories, and narratives. We can study the politics of categories, both from above and from below … A focus on categories, in short, can illuminate the multifarious ways in which ethnicity, race, and nationhood can exist and ‘work’ without the existence of ethnic groups as substantial entities.

Categories such as “English,” “Hungarian,” or “Arab,” today understood as “national” categories, have long histories, and their social meanings have changed over time. Their study does not depend on any particular threshold for “nationalism.” Brubaker’s emphasis on categories, classification, and cognition moves nationalism studies forward. Scholars of nationalism have only begun to reap the benefits of Brubaker’s approach.

Acknowledgments.

Thanks to Sacha Davis, Daša Ličen and László Vörös for encouraging me to write this article.

Disclosure.

Author has nothing to disclose.