Introduction

In 2015, first Portugal and shortly after Spain passed laws outlining processes for descendants of Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula after 1492 to “reclaim” citizenship. The displaced Jews, known as Sephardim, had largely settled in the Ottoman Empire. Modern Turkey is home to a large Sephardic community, and numerous members applied for Iberian citizenship. While many had previously applied for Spanish citizenship through an esoteric process (explained later), Spain’s 2015 law brought immediate approval to pending applications. Neither Spain’s nor Portugal’s law required residency, and applications could be completed almost entirely from abroad. New citizens were not expected to relocate or pay taxes on income earned abroad. A key difference between the two countries is the more stringent expectations of Spain: applicants were required to pass language and citizenship tests. The Spanish process came with an expiration date and closed in October 2019, having granted citizenship to fewer than 10,000 descendants, only half of whom went through the newly established procedure (Kern Reference Kern2019). In contrast, by 2020, Portugal had approved 17,000 people for citizenship with more than 50,000 applications pending (Cruz Çilli Reference Cruz Çilli2020).

Since the only significant difference is the application process, these laws present a valuable comparison to examine bottom-up perspectives in citizenship studies, a field that has focused largely on the perspective of the state, particularly in political science (Pogonyi Reference Pogonyi2019). The cases allow us to examine how applicants perceive these offers, why they choose to engage, and on what terms. Do applicants feel emotionally attached to one country over another? Do they view citizenship as a recognition of their identity? Is such recognition desired? Why have more people applied to Portugal than to Spain? What about taking up both offers?

To answer these questions, I conducted semistructured interviews with citizenship-eligible Sephardim from Turkey, who constituted a large share of the applicants. Contrary to the rhetoric from the Iberian states, I argue that the great majority of applicants did not have emotional motivations for obtaining citizenship. Even when applicants felt a cultural connection—often only to Spain—they separated these sentiments from citizenship. While I expected speakers of the traditional Sephardic language Ladino to have stronger identity attachment, this was not the case. Ladino- and Modern Spanish–speaking applicants all displayed similar compartmentalization, separating language familiarity from citizenship. Applicants were not particularly interested that this process came about as part of historical reconciliation. In fact, many were suspicious of state motives. They were not convinced that states would grant citizenship to rectify their ancestors’ expulsion. They believed (correctly, it may be argued) that Iberian states must have other motivations.

Practical advantages, often for applicants’ children, were the main motivators. As the relevant literature suggests, applicants had a strategic (or instrumental) mindset. I identify three major practical benefits and argue that applicants were motivated by a combination of these. The Jews of Turkey are a discriminated minority well acquainted with outbursts of (at times violent) antisemitism. Thus, the first motivator, in the background for many applicants, was having a new citizenship as an “insurance policy,” in case Turkey becomes unlivable for Jews or the state decides to expel them outright, a possibility mentioned by some interviewees even while acknowledging its unlikelihood. Another motivator was visa-free travel: avoiding hassles, fees, and humiliation at consulates and airports. Finally, the third motivator, which some applicants stressed, was moving up in the global hierarchy of mobility. Iberians can live and work anywhere in the European Union (EU). Though none of the applicants had plans to relocate at the time of application, they wanted to have the option to do so. Older applicants wanted these freedoms for their children: for affordable education or “building new lives” in Europe, not necessarily in Spain or Portugal. This final motivation was underlined more by wealthier applicants. With regard to choosing between the two states, applicants were strategically minded and simply chose the path of least resistance. The Portuguese process, with no tests or language expectation, became more popular. While participants expressed and demonstrated a lack of emotional attachment to either Iberian state, many were vocal about their attachment to Turkey, their primary citizenship and (for most) current residence. Some wanted to expressly dispel any notion that getting Iberian citizenship made them less Turkish or less bound to their country of origin.

This study contributes to the literatures on transnational justice and citizenship by taking a bottom-up approach to citizenship restitution. I begin with an overview of the citizenship literature. Then, I explain my methodology and note my positionality. Next, I explain the development of the application processes and the steps involved. I then turn to applicant motivations, starting with cultural reasons. Finding these to be virtually irrelevant, I move on to the three strategic motivations described earlier: fears relating to Jewish identity, ease of travel, and the desire for advanced global mobility. Finally, I discuss the new citizens’ perceptions. I find that participants still take a strategic approach to their “restored” citizenship. I conclude by summarizing my findings.

Changes in Citizenship Politics: An Overview

Since the 1990s, multiple-citizenship holding has increased and become more acceptable (Aneesh and Wolover Reference Aneesh and Wolover2017; Pogonyi Reference Pogonyi2019). Conceptions of citizenship increasingly emphasize individual rights over duties to the collective. The end of conscription, the rise of supranational communities like the EU, and increased global migration have contributed to this shift (Balta and Altan-Olcay Reference Balta and Altan-Olcay2016). This change has occurred in Western democracies to such an extent that “toleration of multiple citizenship has become the norm” (Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019a, 1). Citizenship has thus been “de-nationalized,” becoming “‘lighter’ in symbolic and emotional content” (Joppke Reference Joppke2019; Harpaz and Mateos Reference Harpaz and Mateos2019, 834).

The citizenship system is concretized in “the passport—that little paper booklet with the power to open international doors” (Torpey Reference Torpey2000, xi). It is such a distillation of citizenship that some refer to naturalization as “getting a passport” (Bauböck Reference Bauböck2019; Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019a; Pinto and David Reference Pinto and David2019). Passport holding is intimately connected with rights and living standards (Shachar Reference Shachar2009). Harpaz (Reference Harpaz2019a) systematizes this in a three-tiered global hierarchy of citizenship, with Western members of the EU, the United States, Canada, settler Oceania, Japan, and South Korea at the top. Citizens of these countries enjoy higher standards of living and global mobility, able to visit or move to other top-tier countries and countries of lower standing. However, citizens of middle- and lower-tier countries must obtain (often expensive) visas, which require extensive questioning and documentation for mere visitation, let alone residency in a top-tier country. Harpaz’s three-tiered hierarchy is the framework for this study.

Individuals with middle- and lower-tier citizenship, especially class and ethnic elites, have formulated ways to respond to this global inequality. Migration is the most visible and heavily studied. However, a smaller group has been using the increased acceptability and accessibility of multiple citizenships to move up in the global hierarchy without relocating. This strategy of obtaining compensatory citizenship to compound rights is mostly employed by elites in middle-tier countries who face barriers to participating in global networks of prosperity (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1992; Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019a). Using existing privileges of wealth and, as this study shows, ancestry, they obtain global mobility. This phenomenon is called strategic, instrumental, flexible, or compensatory citizenship, or “citizenship à la carte” (Balta and Altan-Olcay Reference Balta and Altan-Olcay2016; Harpaz and Mateos Reference Harpaz and Mateos2019; Joppke Reference Joppke2019).

There are different methods of strategic citizenship acquisition. Direct purchase, offered by countries including Malta and Portugal (Aneesh and Wolover Reference Aneesh and Wolover2017), and strategically giving birth in jus soli countries are the first two routes (Baltan and Altan-Olcay Reference Balta and Altan-Olcay2016; Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019a; Ong Reference Ong1999). A third strategy is restitution of citizenship through ancestry, an extension of jus sanguinis (citizenship by blood). Some states allow for broken chains of citizenship inheritance to be repaired, particularly when this was caused by an injustice like the Holocaust. These arrangements expand ancestry into a type of capital, which, when combined with wealth, upgrades one’s position in the global mobility hierarchy.

Laws restoring citizenship to former citizens and descendants appeared in the post–World War II era. The relatively recent legality of multiple citizenships brought renewed interest to these schemes (Toby Axelrod, “Thousands of Jews from Around the World Expected to Seek Austrian Citizenship,” Times of Israel, September 2, 2020; Dumbrava Reference Dumbrava2014). While some states require repatriation, others do not even necessitate a visit (Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019b; Joppke Reference Joppke2019). Some have language requirements, but many do not. One of the earliest examples of citizenship restoration is Germany, which granted citizenship to those deprived of it by the Nazi regime (Basic Law 1949). Enacted “in the context of post-communist restitution,” Romania’s restoration law is based on its former borders and allows people in neighboring countries, particularly Moldova, to become citizens (Iordachi Reference Iordachi, Bauböck, Perchinig and Sievers2009, 178; see also Dumbrava Reference Dumbrava2019; Liebich Reference Liebich, Bauböck, Perchinig and Sievers2009). Romania’s process can be done remotely without giving up other citizenships (Liebich Reference Liebich, Bauböck, Perchinig and Sievers2009, 36). Similar attempts to “undo historic wrongs” of communist regimes have been implemented in Poland and Hungary. Some laws purposefully exclude certain groups, such as the Czech restitution, which excludes ethnic Germans and Hungarians (Liebich Reference Liebich, Bauböck, Perchinig and Sievers2009), despite claiming to “remedy injustices” (Barsova Reference Barsova, Bauböck, Perchinig and Sievers2009).

As of 2014, 14 EU countries allowed citizenship restitution to redress historical wrongs, though not all allowed dual citizenship (Dumbrava Reference Dumbrava2014). Austria, which allows restitution, demanded single citizenship until September 2019. This change caused a wave of Jewish applicants for Austrian citizenship restitution (Axelrod Reference Axelrod2020). Thus, Spain and Portugal are far from unique: European “states often grant citizenship to wrongfully deprived persons” (Dumbrava Reference Dumbrava2014, 2351). In fact, Spain had already implemented restitution for those displaced by its civil war. However, Sephardic restitutions are outliers in that the displacement happened centuries before any other case. Most laws deal with loss of citizenship in the twentieth century, when formal documents of citizenship could be lost or revoked. Sephardic restitution pulls back the examples from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

While states implement restitution for a variety of reasons, this study investigates why individuals apply for and how they perceive restitution. Applicant motivations can be grouped into strategic/instrumental and sentimental/emotional categories (Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019a; Pogonyi Reference Pogonyi2019). While some scholars argue that identity concerns are important (Goldschläger and Orjuela Reference Goldschlager and Orjuela2021; Pogonyi Reference Pogonyi2019), they concede that strategic concerns like obtaining a “premium passport” predominate (Bauböck Reference Bauböck2019; Dumbrava Reference Dumbrava2014; Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019b; Harpaz and Mateos Reference Harpaz and Mateos2019; Joppke Reference Joppke2019). Some scholars note that motivations can differ by age: older individuals may apply for sentimental reasons, while younger applicants are motived by strategic benefits (Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019a; Pogonyi Reference Pogonyi2019). For Spain and Portugal, sentimental attachment is important as both laws expect demonstration of “a genuine link to the country” (David Alandete, “La oferta de nacionalidad a sefardíes satura los consulados españoles en Israel,” El Pais, February 10, Reference Alandete2014). Genuine links are pervasive in citizenship thinking by states, though individuals appear comfortable carrying passports that benefit them without identifying with that nationality (Bauböck Reference Bauböck2019; Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019a).

An individual’s position in the global mobility hierarchy is critical to understanding strategic motivations. People in each tier qualify for ancestry-based citizenship restitution, yet it is overwhelmingly those from the middle and lower tiers who apply (Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019a). Applicants for Romanian citizenship are mostly those lacking free movement in Europe. Many Italian-descended Argentines apply for Italian citizenship, while Canadians and Americans rarely do so. Applicants attempting to climb the hierarchy are strategic, while the fewer applicants making lateral moves could be emotionally motivated. For Iberia, far more of the eligible people applied from Israel, Turkey, and Venezuela than from the EU and United States.

Acquiring citizenship as insurance is another prominent motivation that comes up in interviews (Balta and Altan-Olcay Reference Balta and Altan-Olcay2016; Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019b; Joppke Reference Joppke2019; Harpaz and Mateos Reference Harpaz and Mateos2019; Tintori Reference Tintori2011). Phrases like “just in case” or por las dudas (due to doubts) express similar ideas. These phrases reveal a general unease, often connected to political events, economic expectations, or minority status. This is particularly salient for Jews, for whom unease in one’s own country is a familiar concept. It is no coincidence that many citizenship restitution laws (e.g., Spain, Portugal, Germany, Austria, Poland, Hungary) explicitly or implicitly concern a large population of Jews. Harpaz (Reference Harpaz2019a) highlights that this Jewish insecurity does not dissipate even in Israel; it becomes a national security mindset—applying for restitution out of fear for the destruction of their country.

Studies looking specifically at Sephardic restitution tend to focus on applicants for Portuguese citizenship, and few have interviewed applicants from Turkey. One such study (Pinto and David Reference Pinto and David2019), based on 25 applicant interviews with Jews from Turkey, argues that applicants want citizenship as insurance against deterioration of political conditions in Turkey, particularly informed by local Jewish history. In another interview-based study of 28 Portugal applicants, Kerem (Reference Kerem2021) argues that practical advantages convinced applicants who had no preference between Iberian states. Despite overwhelmingly interviewing Israelis, Kerem generalizes to applicants from the United States and Turkey. He equates applicants from Turkey with Venezuelan ones: looking for an immediate exit. I contest this conclusion. A third study focuses on assisting industries around restitution. Goldschläger and Orjuela (Reference Goldschlager and Orjuela2021) argue that emotional attachments dominate for those for whom application processes constitute identity building, while acknowledging that some are motivated by EU benefits. Since nine of their ten interviewees were US citizens, already at the top of the global mobility hierarchy, their privileging of emotional factors is unsurprising (Goldschläger and Orjuela Reference Goldschlager and Orjuela2021). While conceding that their sample is not representative, they use Pinto and David (Reference Pinto and David2019) and news articles (none in Turkish) to generalize their claims.

Another study by two Sephardic researchers used 55 applicant oral histories from 12 countries, including Turkey. This is the only one to include applicants under the esoteric process (Benmayor and Kandiyoti Reference Benmayor and Kandiyoti2020). They argue that while the Iberian laws focus exclusively on bloodlines, applicants have broader conceptions of identity. They problematize the Iberian insistence that the Sephardim retain a nostalgia for Spain. Their focus is not on uncovering applicant motivations. While they include applicants holding different passports, my spotlight on Turkey makes untangling applicant motivations easier.

Methodology

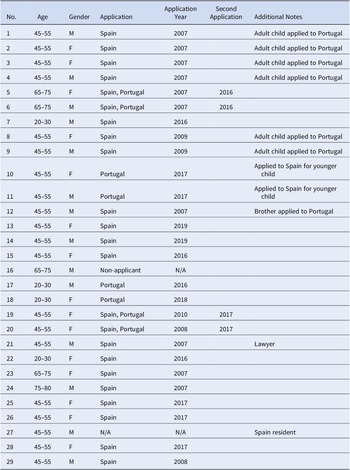

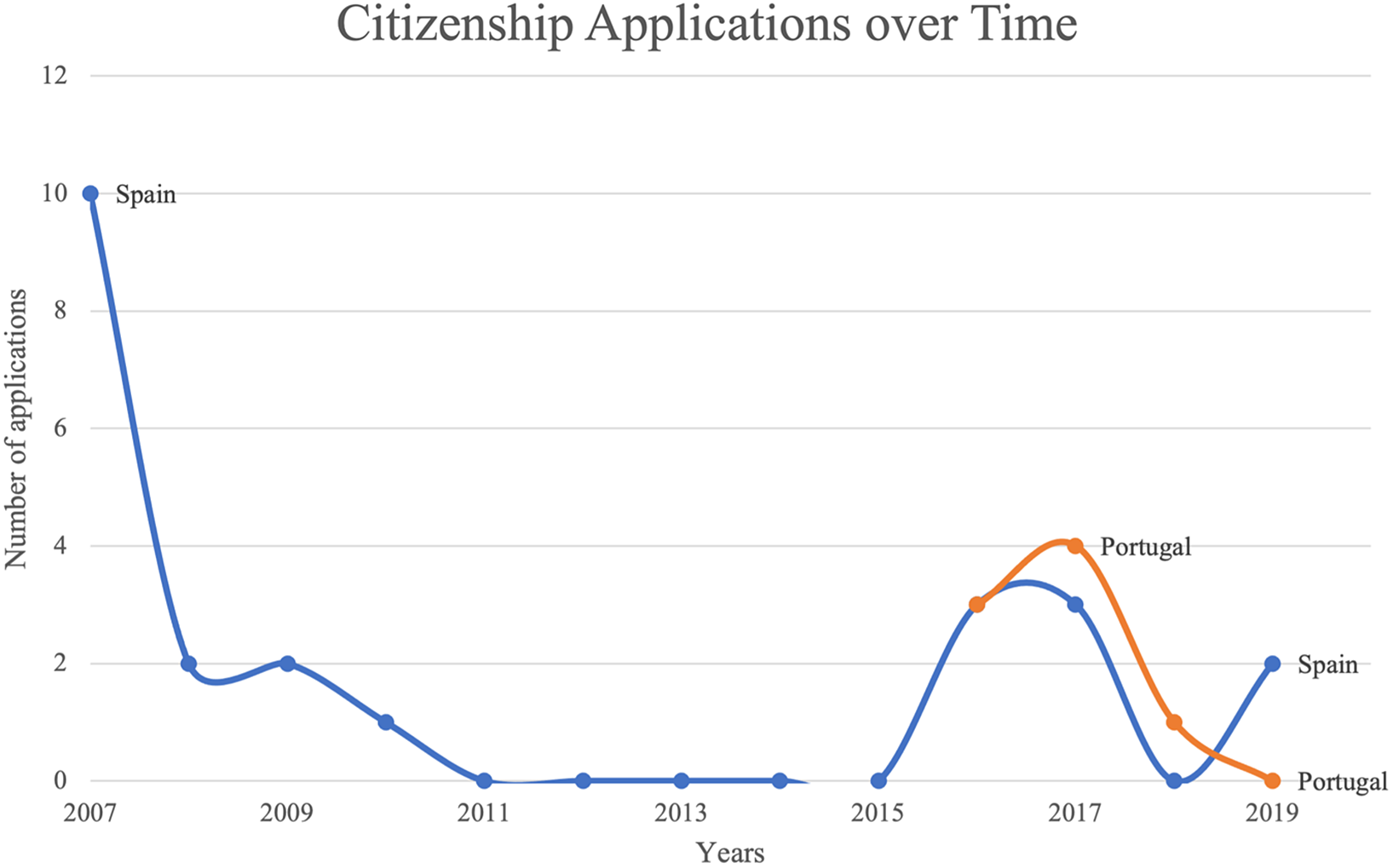

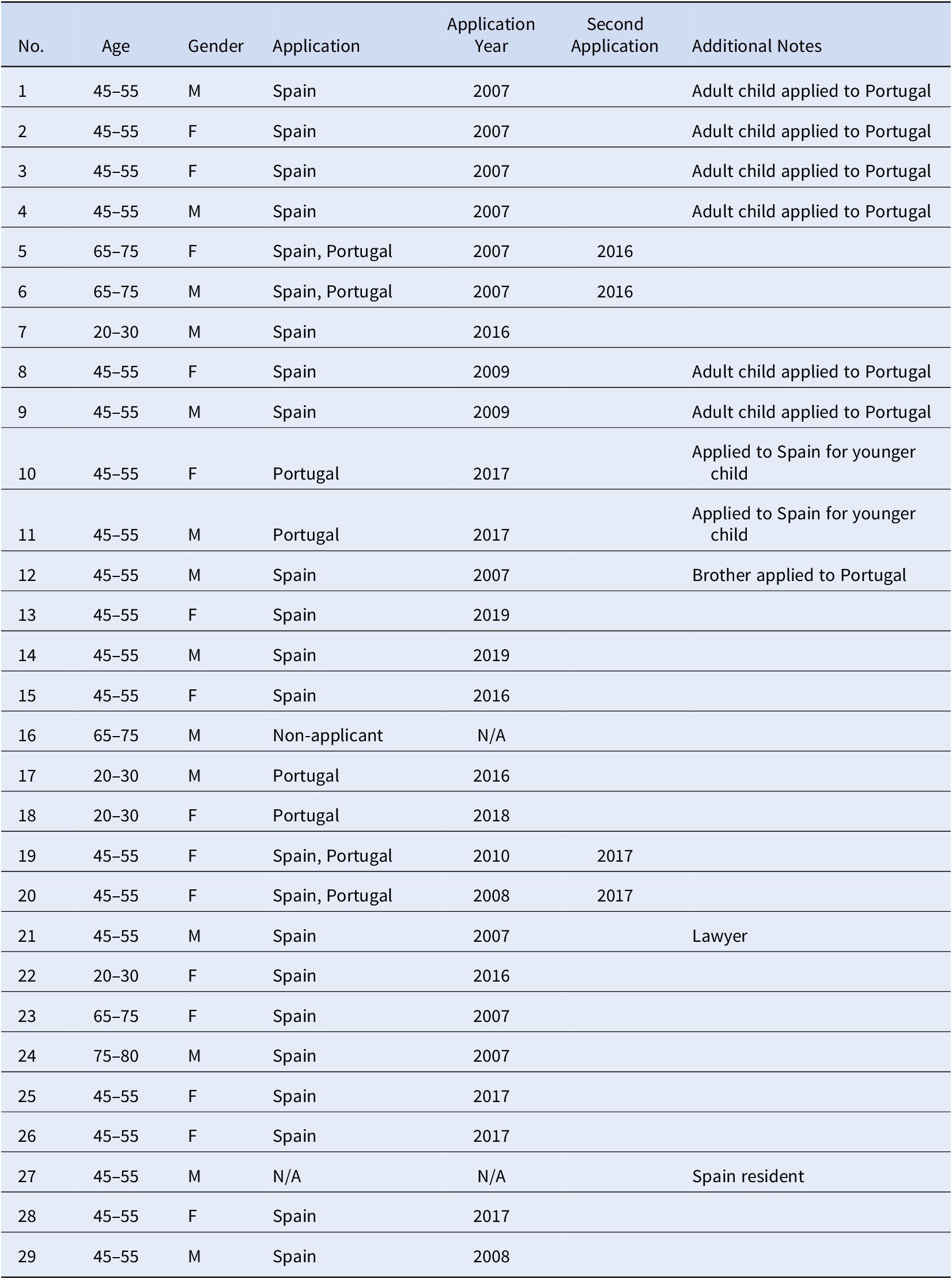

This study is a work of oral history based on interviews conducted in February and March 2021 with 29 Sephardic participants, 15 women and 14 men, aged 20 to 80. In all, 27 successfully applied for citizenship. All participants (except one) were born and raised in Turkey. Two resided in the United States and one in Canada (all on temporary visas). One lived in Spain when we talked but has since left. One participant, who had lived in Spain for decades, assisted restitution applicants. Another was a lawyer who assisted applicants to both countries and was an applicant himself. One eligible participant chose not to apply. His reasoning provides context for applicant motivations. To enable participants to speak more freely, names are omitted. Participants are identified by number; demographic information is summarized in Table 1. Fifteen applicants got citizenship from Spain and four from Portugal. Four applicants got citizenship from both countries, a situation that appears common but so far unremarked in the literature. The pace of applications is shown in Figure 1 (applicants who applied to both countries are counted twice). Of the 24 participants living in Turkey at the time, two lived in Izmir, one in Bursa, and the rest in Istanbul, home to most of the Jews in the country. The participants included eight married couples who were interviewed together, as they applied jointly. Virtually all couples had differences of opinion on their primary motivations. Interviews were conducted in Turkish and, due to the pandemic, online. All translations are mine.

Figure 1. Progression of citizenship applications from participants

Table 1. Demographic information and additional notes of participants

Previous studies had difficulty recruiting applicants or simply did not talk to applicants from Turkey (Goldschläger and Orjuela Reference Goldschlager and Orjuela2021; Pinto and David Reference Pinto and David2019). I was able to recruit a substantial number of applicants with relative ease because of in-group membership as a Sephardic Jew from Istanbul who personally went through the restitution process. Using snowball sampling, I expanded from familiar names to people I had not met before. However, as the Jewish community of Turkey is quite small and densely networked, all participants either knew or knew of members of my close family. The fact that I had been an applicant eased the flow of conversation: participants often sprinkled explanations with comments such as “I am sure you have had this too.” My in-group status helped establish trust, recruit participants, and make conversations more honest. My positionality is important to note since “oral history is a dialogic process; it is a conversation in real time between the interviewer and the narrator”; it influences the content and form of the data generated (Abrams Reference Abrams2010, 19; see also Portelli Reference Portelli2006).

Oral histories can help researchers uncover micro-level perceptions, especially among minorities ignored by the mainstream. This framing is relevant for Jews in Turkey, whose grappling with national identity has been contentious (Neyzi Reference Neyzi2005b, Reference Neyzi2008). Participant narratives allow us to understand how applicants perceived their motives and belonging at different points of the restitution process. It must be noted that oral histories reveal memory—participants are recalling with the benefit of hindsight. Their ideas of the past are colored by their present.

The Restitution Process from the Applicant’s Perspective

This section explains how the Iberian restitution processes unfolded and places these cases into historical context. I show that many participants began hearing about restitution earlier than previous studies mentioned, going back to the 1990s. Applications to Spain began in 2007 and to Portugal in 2015. During the restitution processes, Jews of Turkey did not experience intense questioning (or self-questioning) about their identity, unlike applicants from less consolidated Sephardic communities.

The Prehistory of Spanish Citizenship Restitution

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Iberian states gave extraterritorial status to some (Ottoman) Sephardic Jews. Portugal, later Spain, and other European states gave thousands of these papers in Ottoman cities. Kerem (Reference Kerem2021) notes this connection, though he erroneously labels these papers as “citizenship.” Acquiring these papers were “creative means Jews employed to manipulate state law to their advantage” (Abrevaya Stein Reference Abrevaya Stein2016, 12); a similar argument can be made today. Ottoman Sephardim sought papers to alleviate political insecurity, avoid conscription, travel with ease, and participate in global networks of prosperity (Abrevaya Stein Reference Abrevaya Stein2016, 18). My interviews show that some of these papers transformed into citizenship and some, holding Spanish or Italian citizenship, did not bother with contemporary restitution. Spain’s contemporary law uses the same phrase, Españoles sin patria (Spaniards without country), that philosemitic Spanish senator Ángel Pulido Fernández used in the earlier era. Spain’s philosemitic efforts were met with ambivalence, if not suspicion. One Izmir lawyer wrote to Spain in 1904: “I can assure you that the Jews of the Orient have no special sympathy for your country” (Phillips Cohen Reference Phillips Cohen, Cohen and Stein2014, 207). While interviews reveal some affinity for Spain (but barely any for Portugal), Sephardic Jews in Turkey profess no special interest in “Spanishness.”

Unlike previous studies, I find that for most participants, the restitution process started long before the 2015 laws. The 1924 Spanish decree allotting Sephardim status papers expired in 1930, and a similar practice by Portugal (started in 1913) ended after António de Oliveira Salazar came to power (Abrevaya Stein Reference Abrevaya Stein2016; Benmayor and Kandiyoti Reference Benmayor and Kandiyoti2020, 229). Papers already given by Spain and Portugal could be revoked, expired, and not renewed, but sometimes they evolved into citizenship and got passed down (Abrevaya Stein Reference Abrevaya Stein2016, 4). One participant’s husband had this status: his family had obtained Spanish passports in the early twentieth century and “for multiple generations they never took up Turkish citizenship” (Participant 26). Dual citizenship had been banned in Spain until recent changes for the Sephardim—hence the husband and his father were not citizens of Turkey.

The Jewish past in Spain became a topic of greater interest, especially for the royal family, in the late twentieth century. According to both a participant from Spain and an Istanbul-based lawyer, the king was personally influential in the restitution process. It was King Juan Carlos’s much-publicized first visit to a synagogue in Madrid in 1992, on the day that the Edict of Expulsion had been signed in 1492, that started talk of historic reconciliation and restitution. Some in Turkey said that conversations intensified when the king visited Turkey in 1993. Participant 4 explained, “When the king came to visit [Turkey], all this talk started going around.” An Istanbul participant with business connections to Spain explained, “I heard about this [citizenship] stuff in 1992, but it was only in 2002 that I heard it seriously for the first time” (Participant 14).

The lawyer described the situation that he saw starting in 2006: “There was no special law then. There was the process of granting citizenship to foreigners by cabinet decision; every country has this. This is usually a privilege reserved for scientists, athletes, and the like” (Participant 21). While the 1924 decree had expired, there remained precedent for preferred status for the Sephardim. Thus, there was a possibility to apply for consideration through this specialized process. According to the lawyer, and independently corroborated by a Spain-based participant, using this process for “normal” Sephardic people was a legal innovation by a handful of enterprising and well-connected Spanish lawyers. They (correctly) predicted that wealthy Sephardic individuals would pay high prices. Benmayor and Kandiyoti’s (Reference Benmayor and Kandiyoti2020, 229) statement, that after 1930 Spain “continued to grant special dispensations to a limited number of applicants, until the 2015 law,” obscures this fact. This was a legal innovation of the 2000s, not a vestige of the 1920s. Looking to expand operations from Venezuela to Turkey, a Spanish lawyer reached out to Participant 21. At the time, applications cost 15,000 euros per person, exorbitant even for Turkey’s upper-middle class. However, “there were some who were ready to pay fifty thousand” (Participant 21). Since this process was not formalized, there were no guarantees or appeals.

Most participants mentioned that when they first heard of the process, the cost was prohibitive. “We had heard about it for years, with exorbitant prices, so we didn’t think about it” (Participant 10). There was also widespread uncertainty. Many participants said that they, or their friends and family, refused to even believe that getting Spanish citizenship was possible. Almost none personally knew of a successful application. Thus, during the early years, applications from Turkey were few and far between—yet the overall number kept increasing and wait times extended. For the already skeptical, the years-long wait confirmed the unlikelihood of success. One participant explained that once they heard, “we told our friends, and no one wanted [to apply]. It cost fifteen thousand per person. They thought ‘they’d never give it [citizenship].’ Izmir people aren’t easily convinced” (Participant 3). This sentiment was shared by many others.

Jews in Turkey were suspicious of citizenship restitution. It did not make sense to them that a European state would give them a passport simply because their ancestors had been expelled five centuries ago. Only one participant mentioned that “it didn’t sit right with me to get a passport from the country that threw us out,” though this was immediately followed by a discussion of the cost and uncertainty (Participant 14). Once these barriers were removed, this participant applied. Participants recalling this period perceived Spanish citizenship as a commercially sold privilege rather than viewing it through the lens of emotional attachment or restitution.

Proving Identity

As costs fell, the number of applicants from Turkey jumped from the tens to the thousands, mirroring increases from Venezuela and Israel. The process hinged on proving Sephardic identity, yet Spanish law was mum on criteria. Jews in Turkey had an easy answer: Every Jew born in Turkey is registered as such by the government and belongs to a Sephardic chief rabbinate. Despite the smaller numbers of Aramaic, Arab, and Ashkenazi Jews, the community is overwhelmingly Sephardic. In Turkey, “Jewish and Sephardi are often viewed as equivalent” (Benmayor and Kandiyoti Reference Benmayor and Kandiyoti2020, 237).Footnote 1 However, there was still a practical challenge: what document would demonstrate this communal membership? The lawyer participant developed a procedure and a document checklist, and the chief rabbinate invented a Sephardic certificate (Participant 21). By accepting this document, the Iberian states essentially outsourced genealogical confirmation to the chief rabbinate of Turkey. Thus, Jews of Turkey did not have to engage in genealogical research or hire genealogical “experts” (Benmayor and Kandiyoti Reference Benmayor and Kandiyoti2020, 233–235; Goldschläger and Orjuela Reference Goldschlager and Orjuela2021). Other documents like subscription to the community newspaper became supplementary evidence. Language proficiency—in Ladino or Modern Spanish—was not required but could be considered evidence of a connection to Spain. By the time most participants applied, the process had become regularized.

One participant had converted to Judaism following her marriage to a Sephardic Jew. When she first heard of the process around 2008, “We didn’t even think that I could apply. Because I’m a convert, not Jewish by birth” (Participant 28). She applied after the 2015 law with various documents, including “the Sephardic certificate [from the chief rabbinate] with the dates I got married and converted,” and even then “I was not sure it would happen” (Participant 28). A year later, “I got the passport with tears in my eyes” (Participant 28). Yet even this applicant had entirely pragmatic motivations. While “those acculturated into Sephardi communities but who are not of exilic Iberian Jewish descent are technically not eligible,” her case reveals flexibility in practice (Benmayor and Kandiyoti Reference Benmayor and Kandiyoti2020, 232). Other technical “violations” include acculturated Aramaic or Arab Jews from eastern Turkey receiving Sephardi certification from the chief rabbinate, an institution to which they equally belong. Unlike applicants in secondary diasporas (e.g., in North America), the densely networked community in Turkey was already secure in its Sephardic identity. Members felt no need for external recognition and pragmatic motives predominated compared with those from less consolidated Sephardic communities.

The Slowdown, the Laws, and the Emergence of the Portuguese Option

After 2010, approvals slowed down and there was a lull in applications. The cost of applications to Spain had fallen to 2,000 euros. Initially, “once or twice a month, 20–30 names were granted citizenship by cabinet decision” (Participant 21). However, as the number of applications increased, the process became backlogged. Venezuelan applicants’ pleas of urgency led to Spain prioritizing them (Participant 21). Wait times stretched, “cases would take 5, 6, 8 years” (Participant 21). The slowdown was also caused by a plan to introduce a standardized procedure; the exceptional process had become untenable as a result of the volume. “The state [Spain] paused it and got into the preparation of a law” (Participant 21). “There had long been talk of such a law, it was always ‘almost coming’ since 2004” (Participant 27). In 2012, it was announced that a law was in the works (Flesler and Perez Melgosa Reference Flesler and Pérez Melgosa2020, 21). Seemingly, Portugal passing its 2013 restitution law, which took effect in March 2015, pushed Spain to finally pass its own law. Some participants began hearing about the Portuguese law in 2015, but most learned of it in 2016.

The Portuguese and Spanish laws were similar: both passed unanimously and targeted the same population. The new Spanish law brought a list of required documents. For applicants from Turkey: the aforementioned chief rabbinate certificate, a certificate of membership to the Federation of the Jewish Communities of Spain (available for purchase online; FCJE n.d.), and “regular” documentation such as a criminal background check. Portugal had much the same list. While decision-making was delegated to notaries in Spain, it was taken up by Portugal’s Jewish institutions in Porto and Lisbon (Kerem Reference Kerem2021).

Spain’s law came with immediate approval of 4,535 pending applications (Benmayor and Kandiyoti Reference Benmayor and Kandiyoti2020, 229). By then, Venezuelan applications had mostly been approved; the majority of pending applicants approved in October 2015 were from Turkey. Of the 23 applicants to Spain whom I interviewed, 15 had applied before the 2015 law. Only 2 had received approval before the lull. The rest, 13 individuals, were approved collectively in 2015. Their years-long wait had suddenly and, according to them, unexpectedly, ended. One unplanned outcome concerned the new citizens’ children. When they applied under the esoteric process, their children would have received citizenship alongside them. However, wait times had been so long that many applicants’ children had become legal adults, removed from their parents’ applications. These individuals had to (re)apply under the 2015 law.

Spain’s 2015 law had a few critical differences from the Portuguese law. Both sought evidence of “genuine links,” but Spain asked applicants to take tests to prove this link, requiring applicants to pass the A2 Modern Spanish exam (DELE) and a citizenship test. The latter, la prueba de conocimientos constitucionales y socioculturales (the constitutional and sociocultural knowledge test or CCSE), was created by the 2015 law. Both exams require sizable fees in euros and are administered by the Cervantes Institute (Spanish cultural missions), which has an Istanbul branch. Many applicants said they “understood” these expectations. “It made sense” that Spain demanded demonstrated ability in national language. However, for others, this requirement clashed with reconciliation, the supposed purpose.

During the seven-month period between the Portuguese law taking effect and the passage of the Spanish law, three participants with pending applications to Spain decided to apply to Portugal. “Years passed without any resolution, [so] in the meantime we applied to Portugal. Then all of a sudden Spanish [approval] and right after it came Portugal, so we got that too” (Participant 5). According to the participant, this was not rare; everyone in their circle did the same. “I had given up hope [for Spain] then let’s apply for Portugal before the kids turn 18. But before Portugal came Spain, the kids were 17. Then, when we got approval from Portugal too, we thought why not?” (Participant 20). Unremarked in the literature, a considerable number of Istanbul Jews followed this pattern: having given up on Spain, they applied to Portugal in early 2015, and then received Spanish approval in October 2015 and Portuguese approval in 2016. Having already paid all the fees, none turned down Portuguese citizenship. They summed up this approach with the saying fazla mal göz çıkarmaz (an abundance of goods does not poke out an eye). Double applicants’ attitudes illustrate the low emotional investment in the applications—if not Spain, why not Portugal?

The approval of thousands of pending applications ended skepticism about the process; virtually all Jews in Turkey knew someone who had received citizenship. The difference between the two laws became important at this juncture. Because of the heightened requirements of Spain, the larger trend has been strongly in favor of Portugal. Spain had only approved 5,800 new citizens as of October 2019, with 132,226 applications still pending (Miguel Gonzalez, “‘Los sefardíes ya no son españoles sin patria,’ proclama el presidente de la comunidad judía,” El Pais, October 2, Reference Gonzalez2019), far below Spain’s expectation of half a million (“El Gobierno amplía un año el plazo para que judíos sefardíes adquieran la nacionalidad Española,” La Vanguardia, March 9, 2018). As of August 2020, Portugal had approved 20,000 new citizens, with 100,000 pending (Itay Mor, “Abraçar a história e olhar para o futuro: Portugal e a oportunidade Judaica,” Publico, August 23, Reference Mor2020). “Portugal had surpassed Spain in the race for passports for Sephardim” (Kerem Reference Kerem2021). Eight participants I interviewed had applied to Spain under the new law and eight had applied to Portugal, which is not a representative split. One applicant to Spain commented that “the [language] exam didn’t seem like a burden to me; I thought learning the language would be useful” (Participant 22). However, they noted that the citizenship test, which “ask[ed] things even most Spanish people wouldn’t know,” was a nuisance. Three couples who got Spanish citizenship during the mass approval had adult children who instead of applying for Spanish citizenship under the new procedure, got Portuguese citizenship. Avoiding tests was the main motivation for their choice. Another applicant to Spain who was approved in 2015 said that his brother applied for Portugal. One couple and their adult child applied to Portugal but opted for Spain for their child under 18, for whom exams are not required. Numerous adults applied to Portugal for themselves and to Spain for their children. These examples suggest, ceteris paribus, a lingering preference for Spain, which some attributed to the fact that Spain is a larger, “more important” country.

Applicant Motivations: Cultural or Strategic

What motivated applicants to spend thousands of euros to obtain these citizenships? I first show that emotional reasons were not important and constituted a major motivation for just one participant. A combination of three strategic motivations was the trigger. I begin with fears about Jewish safety, especially relating to uncertainty about the future. Then, I turn to visa-free travel, and lastly to global mobility. Educated individuals facing uncertain (economic) futures use existing advantages to create options like working or going to school in any EU country. While travel or mobility motivations seem to be linked to class, age, and education, Jewish fears were omnipresent.

A Cultural Connection?

Nostalgia or “love of Spain” mentioned in restitution preambles did not play a role for the applicants I interviewed. Only one participant, whose spouse did not share his opinion, expressed feelings of national belonging to Spain as a motivation:

I’ll speak for myself, EU citizenship sure, but a country is apologizing to you, essentially. And we feel very connected to Spain, through Ladino, our food, our everything, and I feel very close to Spain personally. So, I got this very enthusiastically. Of course, there are many advantages […] but these were not the main thing for me. (Participant 1)

Interestingly, this applicant conceived of the process as an apology. Another applicant from the 2000s noted that they liked the idea of an apology: “They are apologizing to us, saying ‘you are our old people.’ That is nice” (Participant 6). However, this did not motivate him to apply.

Most respondents were ambivalent about, if not outright suspicious of an apology. It is important to note that although the preamble to Spain’s law expresses regret for “historic injustice,” there was no official apology (Flesler and Perez Melgosa Reference Flesler and Pérez Melgosa2020, 18–19). Portugal officially apologized in 1996. Yet this had no impression on Jews of Turkey, a major component of the (supposed) intended audience (Flesler and Perez Melgosa Reference Flesler and Pérez Melgosa2020, 32). Participants were unconvinced that states cared about injustice from 500 years ago, which for them did not have sentimental value. This was not because they undervalued Sephardic identity but because they ascribed their culture to the place they inhabited at the time. Sephardic culture as they practiced it was perceived as part of Ottoman and later Turkish lives. Participants wondered out loud in interviews: since the expulsion of their ancestors did not concern them, why would it concern these states? When Participant 3 asked, “The apology thing is silly, why would they apologize?” her spouse, Participant 4, responded, “An apology could have some meaning, but I do not see this an apology.” Another remarked skeptically, “They supposedly gave this to clean off a historical stain, as if they just remembered!” (Participant 7). Most participants looked for economic motives: “I don’t think they gave this as an apology, I thought they’re doing this for their economy” (Participant 10), a position backed up by recent scholarship (Flesler and Perez Melgosa Reference Flesler and Pérez Melgosa2020, 22). Others agreed: “I am suspicious of how sincere this apology is. It came right after an economic crisis. Seems to me they were trying to draw investment” (Participant 14).

Many believed that Spain was interested in presenting a positive cosmopolitan image. Some dismissed restitution at first by claiming that it would be betraying their ancestors but then applied once the extent of advantages and certainty of success became clear. One applicant fitting this description remarked, “We wouldn’t want to offend our grandparents, so forgive but do not forget” (Participant 23). Another criticized this mindset: “Some said stuff about the apology [özür geyiği] but that was an excuse: they all got it later. As if taking this citizenship means accepting an apology from Spain. If it [the citizenship] is useful, why not?” (Participant 20). Thus, even the small number who claimed to refuse the apology were later convinced by practical benefits. The lack of interest in an apology did not differ by gender, class, or age. The dominant view was that “theoretically it’s nice but in practice, I am suspicious of this apology” (Participant 14).

Many remarked on cultural similarities with Spain. Active in Sephardic cultural activities, Participant 16 mentioned that he felt a similarity when he traveled to Spain: “I said, this one resembles my aunt, and that one looks just like my uncle; the way they walk, wear a hat, their hand gestures.” Despite this, he added, “But there are religious differences, cultural differences.” He did not apply. “I did not feel the need; to me everyone is comfortable in their own country, and I am not too into traveling.” The affinity during visits did not rise to the level of national belonging. “We went to Valencia and there were people who looked like Madame Rashel [generic Sephardic name]. I said I guess we came from here; I belong here. The people look just like us” (Participant 14). Yet it was the practical benefit for his child—affordable education in Europe—that convinced him. Only one applicant to Portugal who visited during the application process and another who visited after becoming a citizen expressed similar sentiments for that country. Overall, these sentiments did not have a bearing on applicant behavior.

The most common connection participants brought up was language—mostly Ladino, though a significant number had experience with Modern Spanish as well. None had any exposure to or interest in Portuguese. Younger participants and parents mentioned gravitating toward Spanish among second foreign languages, over German or French. The interest in Spanish often predated restitution, though some learned the language because of the new law. “Seven or eight women, we got together [for this challenge] and for a year took a Spanish classes together” (Participant 25). Only one participant connected language familiarity to citizenship. Two younger participants decided to apply to Portugal to avoid the Spanish language requirement despite having learned some Spanish in school. While I expected a link between Ladino or Modern Spanish proficiency and emotional motivation, this was not the case at all. The most Ladino-proficient participant was the nonapplicant, and several others conversant in the language did not present emotional motivations.

There was essentially no connection expressed to Portugal. Most Sephardim cannot trace their point of Iberian departure, and none are familiar with the Portuguese language, while Ladino is close enough to Spanish for intelligibility. In modern times, “Portugal played more of a background role in the Sephardic consciousness,” especially for those in (post-)Ottoman lands (Kerem Reference Kerem2021). One young applicant to Portugal explained, “If I had any emotional reason to apply, I would’ve researched ‘where are my people from?’—Spain or Portugal” (Participant 17).

Strategic Motivations: Travel, Jewishness, Mobility

Participants overwhelmingly focused on the practical or strategic benefits of an “EU passport.” There are three different practical motivations to be disentangled: (1) insurance against potential Jewish persecution in Turkey, (2) ease of travel, and (3) global mobility. While other cases also involve instrumental citizenship as insurance against political instability, in my cases, this was explicitly linked to fears about Jewishness. Ease of travel is a narrow motivation about avoiding visa applications and fees, while the desire for global mobility is more expansive, concerned with rights to work and live in the EU. Global mobility allows the professional subject—an educated elite bound to place by a weak passport—to have choices. All participants noted ease of travel as well as Jewish-specific insurance concerns to differing degrees, although not everyone brought up global mobility. Mobility was more important for wealthier participants, as using this benefit often requires financial means. Younger participants and those with children were also more likely to mention global mobility.

Fears Relating to Jewish Identity

The uneasy position of Jews in Turkey is summed up by a Ladino saying: El turko no aharva al djudio, ma si lo aharva? (The Turk does not hit the Jew, but what if he does hit?) Turkey is a place where many Jews cannot see a future. Pinto and David (Reference Pinto and David2019, 2, 5) call this ontological insecurity “caused by perceived de-secularisation, authoritarianism and anti-Semitism” and believe that the acquisition of a second citizenship thus becomes “an opportunity to cope with a highly stigmatized identity and manage ontological insecurity.” They argue that current political developments—in addition to antisemitism—cause Jews to perceive higher risk for themselves and motivate applicants (Pinto and David Reference Pinto and David2019, 5). However, the fear of the de-secularization that Pinto and David identify is largely shared by secular Turks. In that sense, they overemphasize Jewish specificity and obscure a larger phenomenon of educated secular middle-class citizens of Turkey seeking global mobility through passport acquisition (Balta and Altan-Olcay Reference Balta and Altan-Olcay2016).

In my interviews, virtually all the participants brought up fears regarding Jewishness. Many named specific antisemitic incidents that had affected their families. For some, citizenship restitution was an unexpected Jewish inheritance that must be passed on. Taking a long view, Participant 29 noted, “If you look at the last century, there is always migration, often from pressures some of which are economic. In the process that begins with the Wealth Tax there is the expulsion of the Greeks [in 1923–1924, 1964, 1974], tensions over Israel-Palestine…To me, being in diaspora means you need to have alternatives.” The comparison to the once-populous Greeks shows that fear of expulsion is not far outside the Jewish imagination.

Like Pinto and David (Reference Pinto and David2019), participants tied Jewish-specific fears to Turkey’s political trajectory. Participant 15 explained, “Where is Turkey going? There are some worries, in case we were forced to leave, this is a plan B.” “Ours is a country where one day doesn’t match the next and as a member of the Jewish community, to have a B plan is comforting” (Participant 25). This opinion was shared by younger applicants as well: “Turkey’s politically pessimistic, especially for Jews, and to have a way out is good” (Participant 7). Many participants summed up this motivation as insurance or bulunsun (just in case), as mentioned in previous literature. The cultural particularity of the Jews of Turkey is apparent from this remark: Allah lazım etmesin ama bulunsun (May Allah not make us need it, but just in case) (Participant 3).

Insurance was not always about fleeing; “It gives us a sense of security: Maybe Spain would back us up [if something bad happened]” (Participant 6). The phrase used (sahip çıkar) connotes ownership—that Spain could assert its possession of Jews to protect them from their other “own” government in Turkey, where they are supposedly equal citizens. Some participants believed being foreigners might make them more secure, just like the protection papers era. These fears reveal how unconvinced Jews are by state discourse insisting that they are accepted as equals; their experiences show them otherwise. Yet participants also wished to underline their Turkishness throughout interviews, as I discuss later.

Another advantage of Iberian citizenship that some participants mentioned was avoiding conscription. Turkey has mandatory service for men, which plays a significant social organizing role in the majority society (Altınay Reference Altınay2004); this role appears weak, if not nonexistent, for non-Muslims, who tend to perceive conscription as a burden. This is partially because military service continues to be a space of heightened discrimination. Both in World War I under Ottoman “worker battalions” and during World War II in Turkey’s “public worker military service,” non-Muslims were used as free menial labor in lieu of military service (Bali Reference Bali2008b; Neyzi Reference Neyzi2005a). In addition to such episodic humiliations, non-Muslims experience discrimination in regular service (Bali Reference Bali2011). Sevag Balıkçı, an Armenian, was murdered by a fellow soldier in 2011 on Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day. Thus, Jewish interest in avoiding conscription is unsurprising. While dual citizens do not receive full exemptions, they are eligible for shorter service and long deferments.

There was a notable lack of attention to Israel within the insurance discourse. Often, Israel is positioned (and positions itself) as the ultimate insurance policy for diaspora Jews. While participants expressed sympathy for Israel and have relatives and friends living there, only one mentioned “Israel as insurance”: “For us the emergency situation idea is not [Spain]” (Participant 8). One mentioned an aunt for whom Israel played such a role, while another said that her sister, who was an Israeli citizen, did not feel the need to apply. Israel was possibly discounted because its passport cannot be acquired without leaving Turkey: “Israel exists of course but to become an Israeli [without moving] is very difficult” (Participant 29).

It appears that for many elderly Jews who do not travel internationally, the insurance policy motivation was not enough to prompt application, even as their children and grandchildren applied. This is noteworthy since older Jews personally experienced the worst antisemitic episodes. The mismatch hints that Jewish fears are ultimately a background motivation. “As a family, the idea of insecurity in Turkey was present in the background, so just in case” (Participant 18). Ease of travel and global mobility were more important draws.

Ease of Travel

For the Izmir couple, “the difficulty of obtaining visas was important. We looked at other countries as possibilities; it was too difficult to get [citizenship from] Canada. Getting visas was becoming more difficult” (Participant 4). They were thinking about this in the late 2000s, when, after 9/11, getting visas became harder and holding a passport from a Muslim-majority country—regardless of Jewish identity—added to the difficulties. “Our goal wasn’t moving but living here [in Turkey] as Spanish citizens so we could go abroad with ease” (Participant 12). To travel as Spanish citizens was more advantageous.

One participant recounted his experience traveling during the global pandemic: “The importance of [this passport] increased in the pandemic. We were going to Bulgaria. One [Turk] had a Bulgarian passport, he was a dual citizen, he passed. The ones holding TC [Turkish passports] couldn’t pass, they had to turn back” (Participant 12). Other participants also remarked that passport power became more apparent during the pandemic. When borders hardened in 2020–2021, participants noticed they had more freedom as Europeans. Some had children studying in EU countries and were able to largely come and go when Turkish citizens could not.

Most participants in their forties and fifties said that their parents did not apply: they did not travel, and so they did not need this passport. “I asked my mom and dad and they said we can’t be bothered with this. They were 65–70, [and said] ‘what do we need this for?’” (Participant 12). Participants over 60 did report that they enjoyed traveling and that it was an important consideration for them. This might hint toward a class cleavage: while older middle-class people who did not regularly travel abroad were uninterested, upper-middle-class Sephardim traveling frequently applied. The Spanish passport “has benefitted us greatly, we don’t have the burden of getting visas is anymore, we have become like Europeans. We can also travel to the US more easily. First of all, we considered the possibility of easier travel” (Participant 23). Another agreed, “traveling visa-free is a delight, you feel good” (Participant 5).

Many participants mentioned that they did a mental accounting comparing the price of restitution with the many visas they would have to get in their lifetime on a Turkish passport. Once the application became cheaper than a lifetime of visas, applications increased. Eligible Jews already holding top-tier passports were initially uninterested in restitution (e.g., relatives, friends, and one participant himself, who held Italian, Israeli, or Canadian citizenship). However, as application costs decreased, those holding non-EU premium passports also applied, motivated specifically by EU freedoms. Overall, travel freedom was a central motivation.

Desire for Global Mobility

It must be noted that at the time of application, none of the participants intended to relocate to Spain, Portugal, or any EU country. Participants over age 40 consistently stressed that they would not settle outside Turkey unless they were forced to do so. In such a context, what does global mobility mean? One participant explained,

If the outlook is ‘I won’t live anywhere else’ this could appear needless, but if the vision is ‘I want the ability to choose our future, we could use this’ then it [restitution] is a godsend. No one can get EU citizenship from where they’re sitting for a couple thousand euros like this. (Participant 21)

What this participant qualified as “vision” is essentially acting as “an entrepreneur of possibilities […] provisionally buying the person [they] must soon become” (Mirowski, quoted in Houghton Reference Houghton2019). This vision involves buying—or acquiring—citizenship to become more mobile and attractive as human capital—to become “freer” by having more abstract “options.” This desire for movement is not simply insurance; it is about following global networks of wealth. As Bauman (Reference Bauman1998) explains, while capital can move freely in search of better opportunities, labor is left to face economic crises. The premier passport, when combined with wealth, allows individuals to chase capital in an unending hunt for lasting prosperity. Such individuals “actively seek to invest in their selves are securing their own futures, while those who do not are left to face the consequences alone” (Houghton Reference Houghton2019, 623). Activating the global mobility advantages of a top-tier passport requires wealth, and it was often wealthier participants who expressed this “vision.” Combining their “ancestry capital” allowing citizenship restitution with financial capital, some Jews of Turkey can reconstitute themselves—and, more importantly for most participants, their children. This desire comes most of all from a place of economic insecurity and uncertainty.

Younger participants stated this conception directly, often based on migration experience. Having gone to university abroad, they wanted options: “After graduating, I looked for work in the US, but I wasn’t too excited to stay so I applied to some schools in Europe” (Participant 22). Another explained that “after living in the US, I like the idea of possibly working in Europe, closer to home [Turkey]. For my field France is a more viable option, but I could consider Portugal” (Participant 18). The same participant said that young relatives had applied with intentions of starting businesses based in Europe or possibly living in Europe: “There is a lack of opportunity [in Turkey], in the economic sense and you sort of have to go abroad to pursue professional opportunities” (Participant 18). Another participant similarly said that becoming a Spanish citizen “has decreased my stress of ‘can I stay in the country I went to university in?’ There is now an opportunity, if I wanted, for a fresh start somewhere else, and I think this is especially important for young people. You get the chance to get your foot in the door” (Participant 7). One participant who already had a non-EU strategic passport said, “As time went on, we thought having an EU citizenship would be an added advantage” (Participant 17).

Older participants expressed similar ideas for their children. This was also an explanation offered by the nonapplicant: “I don’t have kids. If I was a dad, I’d have a responsibility to maybe provide this opportunity” (Participant 16). For some past prime working age, and some without university degrees, the abstract choices were already closed off or perhaps simply undesirable. However, they wanted to impart this vision to their educated, English-speaking children. In fact, some saw this as their responsibility, to bequeath such freedoms to their children. Access to affordable university education and professional opportunities in the EU were dominant reasons. None of the applicants brought up possibly retiring in the EU, mentioned in previous studies (Benmayor and Kandiyoti Reference Benmayor and Kandiyoti2020; Kerem Reference Kerem2021). This might signal how deeply rooted older Jews are in Turkey: “I have no intention of leaving; all my social relations are here” (Participant 12).

For their children, however, they want options. “For our son, at some point in the future he could need it [işi düşer], if an opportunity arises in Europe” (Participant 1). This sort of vague signal of uncertainty often came up: “For the kids someday [yarın öbür gün] it would be easy to study or work. For example, our daughter went on Erasmus and her [Turkish] friends had a hard time with visas. It’s good to have [EU citizenship] in your pocket” (Participant 10). These ideas mirror those of non-Jewish citizens of Turkey, who also “strategically combine privileges” (Balta and Altan-Olcay Reference Balta and Altan-Olcay2016, 939). Balta and Altan-Olcay’s (Reference Balta and Altan-Olcay2016, 952) Turkish interviewees “saw themselves as ‘global citizens,’ but the difficulties they had in crossing borders contradicted this claim.” Participant 25 summarized her outlook: “I am giving my kids an inheritance that cannot be bought.”

Global mobility advantages were also clearly front of mind for the Russian Jewish oligarch Roman Abramovich, who was granted Portuguese citizenship in April 2021 despite no publicly known Sephardic connection. The government inquiry into this possible case of fraud upended the continuing process in Portugal in 2022, leading to a pause and the withdrawal of the Porto community from its role in the citizenship-granting process. This ongoing debacle is testing the commitment to reconciliation of both the Portuguese government and the public as they realize just how instrumentally applicants (deserving or fraudulent) view restitution (Nesi Altaras, “The Rotten Saga of Roman Abramovich’s Portuguese Citizenship, and Its Repercussions,” Haaretz, March 30, Reference Altaras2022).

Living Iberian Lives?

Participant interactions with Iberian officialdom partially shaped their perceptions of new citizenships. As external citizens, their connections to Iberia or the EU (or lack thereof) reveal that the instrumental outlook continues after receiving citizenship. Many applicants granted citizenship during the mass approval later visited Spain to obtain ID cards. These participants reported exclusively positive interactions with bureaucratic offices in Spain, even when they spoke English. Many used this opportunity to vacation in Spain and enjoyed visits to Madrid and/or Barcelona. Despite arriving with a local passport, they interacted with the country as tourists. Invoking the insurance notion, Participant 19 said, “When I visited Spain I thought: if one day something happened, I could live here.”

Despite not having planned it, two participants ended up living in Spain, both in Barcelona. One studied abroad there for a semester, while the other moved for a graduate degree and stayed another year. The latter participant explained, “I applied to schools in Europe, including one in Barcelona. I was not a citizen at the time. It just happened coincidentally that I ended up going to this school in Barcelona, and I became a citizen that summer, few months before I moved” (Participant 22). She said that she did not develop national belonging to Spain. The other participant, who spent five months in Spain, said that he enjoyed it, but without knowing fluent Spanish and with Spain’s current economic circumstances, moving there was undesirable.

New citizens of Portugal were not legally required to visit Portugal, though many did so to speed up the process. Like those visiting Spain, they had positive interactions with the local bureaucracy despite speaking English. Others visited after becoming citizens to see their new country. Visitors to Spain or Portugal did not note particular interest in Jewish sites, except for the long-term resident of Barcelona. Some mentioned that they became more sympathetic to their new country, while others became more interested in learning Modern Spanish. Only one reported interest in learning Portuguese after receiving citizenship. None initiated new investments in Iberia or in the EU.

During Turkey’s slow rollout of a Chinese vaccine for COVID-19, participants hoped EU citizenship could get them Western-produced vaccines quicker. “I wish there was some EU vaccine right, but no such thing exists” (Participant 1). “We thought about going even, to get the vaccine or we were curious, maybe the consulate could have some information about vaccinating us. But then we got vaccinated here anyway so we dropped this” (Participant 5). Soon after my interviews, hundreds of Jews holding EU passports used their freedom of travel to drive from Turkey to Bulgaria and get the Western vaccine of their choice. This continued for some weeks until the Bulgarian government announced that it would limit vaccination to full-time residents (Klein Reference Klein2021).

While external citizens have the right to vote through consulates in Spain and Portugal, no participant voted in any election despite having had the chance to vote in at least one national election. Only one participant attempted to vote but was ultimately deterred by administrative hurdles. Another explained, “I read up a bit but then thought I don’t live there; I don’t know enough” (Participant 17). The lack of electoral participation once again signals the lack of emotional connection. “We don’t particularly care what goes on over there” (Participant 26).

Contrary to experiences in Spain, almost all Spanish citizen participants complained about the Istanbul consulate. The consulate suddenly had thousands of local citizens to serve. According to the participants, it has not done well. Consulate employees often refused to speak English or Turkish and sniped when participants’ Spanish was not good enough. Many participants noted consulate officers’ rudeness. In one case, the consulate refused to reschedule an automatically assigned swearing-in ceremony (the final step to become a citizen) for children who were competing in an international sporting event on that day. None of the participants ascribed emotional value to this ceremony. Numerous participants did not even mention it in their recollection of the process. Participant 7 said that a consular employee assisting his mother told her, “We are here doing you a favor and you still complain.” One participant qualified consulate behavior as “disgusting,” another as “frankly rude,” while a third said, “At the consulate they make us [Jews] feel that they [staff] are displeased that we have been granted equal rights” (Participant 14). No such complaints were voiced by Portuguese citizens, though they did not express national belonging either.

Many participants qualified their status as “like Europeans” and “almost like Spanish,” or “it is like you’re from there” (Participants 23, 19, and 7). Even after having citizenship for many years, participants still did not describe themselves as Spanish, Portuguese, or even European. Europeanness functions both as a legal status allowing mobility and a discursive upgrade. Discourses of Europeanness in Turkey are politically charged, and Jews appear reluctant to assert themselves as European as this could be perceived as defining themselves against or outside of Turkishness (Keyman and Icduygu Reference Keyman and Icduygu2013; Kosebalaban Reference Kosebalaban2007). The identity they did express—explicitly and implicitly—throughout interviews was their Turkishness. Throughout our conversations, participants often referred to Turkey as “our/my country” or simply as “home.” Participants exhibited a strong rootedness, highlighting, “all my social relations are here [Turkey]” (Participant 12) and that “everyone is comfortable in their own country [Turkey]” (Participant 16). While such sentiments were more explicit for participants over age 40, the worry for the political direction of Turkey cut across generations, which Participant 25 summarized as “Ours is a country where one day doesn’t match the next,” while Participant 7 saw Turkey as “politically pessimistic, especially for Jews.”

Many participants made sure to underline their continuing commitment to Turkishness despite taking up new passports. The desire to perform Turkishness, even to an in-group researcher, underscores how Jewish loyalty is under constant questioning in Turkey. They coveted the benefits of EU citizenship but still wanted to appear to be dutiful Turkish subjects. These demonstrations of Turkishness in no way contradicted the participants’ vocally expressed Jewishness. While they saw themselves as belonging to Turkey, they were obviously aware that many of their fellow citizens disagreed: “We are Turkish citizens but always from the outside they see you as djudyo [Ladino: Jewish], am I wrong? If you ask your folks, they’ll give the same answer” (Participant 12). The participant looks for confirmation of this marginalized status from the in-group researcher and conceptualizes it as a communal predicament. Jews in Turkey understand their position as legal citizens outside the bounds of the contract of Turkishness—only Muslim-Turks can ever obtain first-rate status in this social contract (Ünlü Reference Ünlü2018). They attempt to secure themselves and their future (or their children’s) in this outsider role by acquiring another passport, but this in no way constitutes a break in the belonging they feel to Turkey. As explained earlier, participants wanted the protection or insurance of a European passport more often to continue their lives in Turkey in peace, not to leave it behind. Participants were aware that Turkish public opinion already discounts them as equals. As Participant 12 explained, they feared that Turkish society could mark them as disloyal for getting Iberian passports and wanted to dispel such a notion—hence the performance of Turkishness to the researcher. This performance is so regularized among Jews in Turkey that it is arguably not a conscious one but a repeated script.

This desire to avoid the disloyalty label and appear “grateful” to the Turkish state is especially exhibited by communal leadership (Baer Reference Baer2020), and the arena of Iberian restitution was no exception to this pattern. Chief Rabbi Ishak Haleva has publicly and explicitly refused Iberian restitution; on a trip to Portugal, he felt the need to declare “I’m a Turkish Jew, period” (Liphshiz Reference Liphshiz2016). For him, being Turkish was his reason for not applying for Portuguese citizenship—otherwise he would be (or at least appear) disloyal. This loyalty theater is ironic, as his rabbinate prints certificates for his congregants to seek restitution. While participants stress their belonging to Turkey and their desire for Iberian passports for the three reasons outlined here without contradiction, communal leaders like the chief rabbi are deterred by potential charges of disloyalty. Yet, they are unable to slow the tide of applications and in fact materially aid them by dispensing certificates. The position of the chief rabbi (and the participant who did not apply) suggest that if there is a cultural motivation regarding citizenship restitution, it is the pressure of Turkishness, the expectation to perform gratitude to Turkey, that leads to nonapplication or even public refusal of Iberian restitution. A pressure to which the majority of the Jews of Turkey have not succumb to, as demonstrated by the thousands acquiring Iberian passports.

Conclusion

Over the last decade, Spain and Portugal have been granting citizenship to Sephardic Jews. The processes were formalized by laws that took effect in 2015, following a pan-European lightening of citizenship norms. My interviews with Sephardic restitution applicants from Turkey show that while some feel affinity to Spain (not so for Portugal), this is not why they applied. Interest in Spanish citizenship began in the mid-2000s, but when Portugal became an option in 2015, interest shifted there. Application decisions were guided by price and practical benefits. Unlike Sephardim in secondary diasporas, applicants from Turkey did not engage in genealogical research to prove identity, and the process did not constitute identity building. Applicant motivations were a combination of Jewish fears, ease of travel, and global mobility. Desires to insure against possible antisemitic persecution was in the background for many but the other two reasons were predominant. Holding an EU passport meant avoiding visa applications and possible mistreatment at consulates and airports, summed up as ease of travel. In addition, some applicants sought to give themselves or their children as much choice as possible to run after economic prosperity; referred to as global mobility. Jews of Turkey did not develop national attachments to Spain or Portugal after acquiring citizenship. Applicants had been interested in affordable education and ease of travel, and that is how they utilized their passports. The way they view restitution shows the wide gap between top-tier and middle-tier citizenships. Middle-tier citizens grasp at the advantages of premier passport when previously trivial ancestry allows for access to such benefits. Descent-based restitution is only a minor edit to the complex system of citizenship inequality, though it does greatly affect the circumstances of its beneficiaries.

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without the guidance and support of Professor Juliet Johnson. The support of my parents, Betsi and Ceki Altaras, was essential. Thank you to them and to the participants who shared their experiences with me.

Disclosures

None