Introduction

Ambassador Nimetz, the foreign official most associated with the near three-decade long effort for the settlement of the Macedonia name dispute, has queried in a recent article “Why did it take us so long?” (Nimetz Reference Nimetz2020). What was seen to most outsiders as an incomprehensible diplomatic spat that should not exist in the first place, became one of the most persistent disputes in the Balkans since the collapse of Yugoslavia in 1991. It was eventually settled on June 17, 2018, when Greece and North MacedoniaFootnote 1 signed the so-called Prespa Agreement.Footnote 2 To account for why it took the two countries twenty-seven years to resolve this dispute requires the examination of multiple actors and processes.

Recent scholarship has already started offering insights, often critical, into the process of the final settlement (Heraclides Reference Heraclides2018a; Armakolas and Petkovski Reference Armakolas and Petkovski2019; Chryssogelos and Stavrevska Reference Chryssogelos and Stavrevska2019; Hagemann Reference Hagemann2019; Loizides Reference Loizides2020; Vankovska Reference Vankovska2020). In contrast, in this article we take a step back from contemporary developments and investigate the obstructive policy environment that prevented the two sides from reaching an agreement earlier. We argue that such an analysis advances our understanding of the trials and tribulations of the process that led to the signing of the Prespa Agreement and the turbulent ratification process (Armakolas et al. Reference Armakolas, Bandovic, Bechev and Weber2019). It could also point to the challenges of implementation as well as explain efforts to resist the construction of a strong partnership between Greece and North Macedonia (Armakolas, Petkovski, and Voudouri Reference Armakolas, Petkovski and Voudouri2020).

In this article we focus on a factor that is often stated as important, but which has curiously received little attention in Greek foreign policy literature: the role of Greek public opinion in making the policy environment more challenging by insisting on an unrealistically maximalist agenda. In contrast to previous studies that have handled the issue incidentally or presented anecdotal evidence, we will delve deeper into the measurable aspects of public opinion by offering systematized evidence. We probe dimensions of public opinion that the theoretical literature considers important for eliciting its potential impact on foreign policy making. More specifically, we focus on the salience of the issue, the actual content of the attitudes, and the coherence across groups in society, in an effort to scrutinize the disposition of Greek public opinion. We provide original data from the first ever comprehensive survey exclusively focused on the name dispute. The survey was conducted in 2016, at a politically neutral period, before the issue was re-introduced in the policy agenda.

Notwithstanding three decades of diplomatic wrangling, we argue that at the outset of the negotiation process the Greek public remained highly rejectionist, opposing any compromise solution. The issue continued to be very salient for Greeks, despite not having been in the policy agenda for a long time. We also identify high levels of coherence of attitudes across societal sub-groups, with an exception being the political-ideological orientation dimension. We discuss the policy implications for the period immediately subsequent to the survey, a period of negotiations for the settlement of the dispute.

The article is structured into three parts. In the first part, we review the literature on the relationship between foreign policy and public opinion and we insist that the equilibrium theory provides the appropriate framework for understanding the dynamics among different political actors in influencing foreign policy decisions. In part two, we track the influence of Greek public opinion on the name dispute. We start this discussion by recounting the early phases of the diplomatic dispute and focus on the actual impact of public engagement in the policy setting. We also provide a brief overview of polling data since the early 1990s. In the final part, we introduce an eclectic framework for analysis that draws on the theoretical insights presented in the first part. We test that framework by presenting data from a survey conducted in 2016, a few months before the start of the negotiations that led to the Prespa Agreement. The concluding section brings the discussion together. It highlights the crucial role of public opinion and implications for policy, and proposes avenues for future research.

1 Public Opinion Influences and Foreign Policy

Contemporary scholarly literature suggests that public opinion should be regarded as a factor that influences the foreign policy decision making process (Holsti Reference Holsti1992; Shapiro and Page Reference Shapiro and Page1988; Foyle Reference Foyle1997; Eichenberg Reference Eichenberg and Eichenberg2016). This thesis rejects the previous dominant Almond-Lippmann consensus (Lippmann Reference Lippmann1922; Almond Reference Almond1977) that viewed public opinion as either shaped or ignored by decision-makers. The rationale of the previously dominant framework was based on an understanding of public opinion as volatile, incoherent, or simply not interested in remote issues that are of trivial importance for citizens’ everyday lives. That framework is challenged at multiple levels. At first, with regards to the argument of stability and coherence, Shapiro and Page (Reference Shapiro and Page1988) presented empirical evidence showing that the American public opinion formed concrete attitudes about international affairs. This was also confirmed in the European context (Isernia, Juhász, and Rattinger Reference Isernia, Juhász and Rattinger2002).

Similarly, regarding the “trivial and remote issues” argument, the way the government deals with foreign affairs has been found to affect the incumbents (Aldrich et al. Reference Aldrich, Gelpi, Feaver, Reifler and Sharp2006; Rottinghaus Reference Rottinghaus2007). Aggestam and Johansson (Reference Aggestam and Johansson2017) suggest that the relationship between followers and leaders is critical for understanding the foreign policy process. Leaders and followers collectively formulate a common goal and set desired outcomes (Avery Reference Avery2004). Leaders are influenced by their followers’ traits (Post and George Reference Post and George2004), or the conditions in the domestic agenda (Hill Reference Hill2003). Thus, the way that elites perceive potential electoral gains or losses is crucial. Increasingly important is the understanding that the present electoral agenda includes questions of global interest, such as immigration, trade, or terrorism. These, while innately international in nature, at the same time they crisscross the international-domestic divide (Holsti Reference Holsti2004).

If public opinion matters in the foreign policy decision making process, a subsequent question rises to query the nature of this interaction. Graham (Reference Graham and Deese1994; Reference Graham1989) identifies four dimensions that may play a role in determining the direction of policy: the degree of public support for an issue, the efficacy of elite communication strategies, the stage of the policy process, and the elites’ awareness of the role of public opinion. Powlick (Reference Powlick1995) finds a linkage between public opinion and foreign policy that is related to elites, interest groups, businesses, academia, media vendors, or elected officials. These efforts constitute more of a mapping attempt, rather than a solid explanation of what the direction of linkage actually is.

In fact, the exploration of the specifics of this relation is not of paramount importance. What actually matters is the balance of power of all the participating actors. Baum and Potter (Reference Baum and Philip2008) outline a marketplace analogy, that changes the focus of the second question. This “equilibrium model” parallels the struggle to identify the driver in the decision-making process with the futile effort to explain whether demand drives supply, or vice versa, in the market. Thus, it is irrelevant to understand whether consumers propel manufacturers to produce more, or whether it is manufacturers who push consumers to purchase more. What actually matters is the interaction’s outcome. In the case of the foreign policy decision making process this takes the form of a policy output. In fact, the analytical response to the question of whether public opinion is a cause or an effect in the decision-making process remains unclear.

Entman (Reference Entman2003; Reference Entman2004) attempts a typological categorization that involves the administration, the elites, the media, and the public. In his “cascade model,” he outlines that information travels from elites to the media, and then from the media to the public. Also, in Baum and Potter’s framework, there are three driving forces that form a “marketplace” of “coequal” players in interaction: the leadership, public opinion, and the media. While the first two are the main protagonists, representing respectively the top-down and the bottom-up levels of interaction, the dynamic is enhanced by the mediating role of the mass media. The course of influence from or to the media is not fixed. For starters, the advantage of the information provider belongs to the leadership. Subsequently, the media could feed either the demand side (public opinion) or back on the supply side (leadership).

Probably the most important element in this balanced relationship is to understand the attributes of public opinion. Doeser (Reference Doeser2013) shows that public opinion can be ignored when an issue is of low salience for the public, there is elite consensus for a policy course, and incentives exist for notable international dividends. Eichenberg (Reference Eichenberg and Eichenberg2016) proposes a set of four “tests” that could be instrumental for a better understanding of the relationship. He queries the findings of the polls, or what public opinion actually believes, questions how rational public opinion is in terms of volatility and coherence, calls for identifying the factors that influence the formation of beliefs, and questions whether there are any universal determinants of public opinion beliefs. Finally, Powlick and Katz’s “activation model” (Reference Powlick and Katz1998) predicts that public opinion often remains lethargic and disinterested to receive information about international affairs (“information-averse”). Similarly, public opinion is an “involvement averter” that will likely remain disinterested to form an opinion about a foreign affairs problem if not mobilized in that direction (“involvement-averse”). But it could also be activated, triggered by elite debates, the media, or other factors that could potentially lead to raising public opinion’s interest.

2 Greek Public Opinion and the Name Dispute

In this part, we review the main developments that shaped the Greek stance at the early phases of the name dispute and their political implications. In brief, we highlight the Greek society’s pre-existing socio-political atmosphere of insecurity and existential fear, which was aggravated by the dramatic events of the Yugoslav wars. We focus on the emergence of political opportunity and its instrumentalization by certain prominent political actors and the constant reproduction of the threat narrative by newly established, highly commercialized media. Also, we highlight the efforts made by civic actors to shape the political agenda bottom-up. The outcome of these distinct but converging influences, the balance point of the equilibrium, was the unprecedented public fixation with a seemingly remote foreign policy issue that was quickly and astonishingly transformed into an existential identity question. This emotional involvement increased the stakes for political elites leading to a maximalist strategy and, subsequently, to a foreign policy impasse.

2.1 The Making of the Problem

The 1980s was a period of political change and turmoil in Greece. The country was run for the first time by a party that resembled a radical left force. Although it initially openly flirted with radical solutions to various policy questions, eventually it gradually and reluctantly transformed into a more pro-European and center-left political option. Most of the 1980s was a period of severe party polarization, populism, and anti-Western rhetoric, often with thinly veiled nationalist overtones. The decade ended in a deep political and economic crisis, amidst high profile corruption scandals implicating the top tier of the governing elites and political uncertainty after repeated elections had failed to produce a stable government.

The political and economic crisis was deeply felt by Greeks who entered a period of earth-shattering global change after 1989, feeling insecure and uncertain about their future. What for other nations was the start of a period of hope and promise, for Greeks was one of profound concern amplified by an ostensible crisis of identity (Lipowatz Reference Lipowatz1993). The collapse of Yugoslavia brought Greeks’ fears closer to home. For many Greeks – elite members, opinion makers, and ordinary citizens alike – the war in Yugoslavia rekindled fears over their country’s security. These fears had never totally gone away since relations with Turkey kept reaching boiling points at regular intervals for decades. The specter of full return to instability in the wider region and a renewed concern about territorial integrity of their homeland made many Greeks fearful and emotionally involved in their reaction to the Yugoslav collapse. At the same time, age-old stereotypes about the West’s hostility towards Greece and the perceived insidious role of Germany, the United States, and the Catholic Church started making their way to mainstream interpretations of the Yugoslav crisis. A “civilizational reading” of the Yugoslav imbroglio aggravated the pre-existing atmosphere of insecurity and existential threat.

When the question of the independence of a new neighboring state bearing the name Macedonia surfaced, perceptions of existential threat and “civilizational” misreadings of the Balkan crisis converged to heighten Greeks’ anxiety over the course of events. The narrative of the quintessentially Greek name and heritage of Macedonia that is being “stolen” by a neighbouring Slavic nation came to dominate public discourse. The question of Macedonia shook the very foundations of Greeks’ ability to respond rationally to international political change and questioned the Greek society’s commitment to values intrinsic to modernity (Armenakis et al. Reference Armenakis, Gkotsopoulos, Demertzis, Panagiotopoulou and Charalampis1996). Cataclysmic predictions and deeply held fears of Muslims and Slavs, as well as a lack of trust towards the West, came to sit comfortably on a prevalent underdog culture in Greek society (Diamantouros Reference Diamantouros and Clogg1993) projected onto foreign policy (Tsakonas Reference Tsakonas2010; Armakolas and Triantafyllou Reference Armakolas and Triantafyllou2017). The outcome was an emotional reading of the Balkan crisis that pitted Greeks, politicians, and the wider society alike against traditional EU and NATO partners. Greek intransigence extended to numerous issues that, despite pertaining to foreign policy, were experienced by Greeks as involving their identity and culture: support for Serbia, perceptions of responsibility for the breakout of the Yugoslav war, negative assessment of the role of West, alienation from Bulgaria and hostility towards Albania, perceived encirclement by enemy Muslim populations, and existential fears over mass migration from Balkan neighbors (Koppa Reference Koppa, Arvanitopoulos and Koppa2005; Wallden Reference Wallden1994; Reference Wallden and Tsakonas2003).

However, it would be impossible to understand how the name dispute came to dominate the public’s emotions without referring to instrumentalization by political elites. Antonis Samaras, the first Minister for Foreign Affairs to have dealt with the name issue, is widely seen as having stoked nationalism for both domestic political and diplomatic negotiation reasons. On the one hand, Samaras, a young and promising conservative politician, became almost overnight a household name and one of the most popular politicians in the country. On the other hand, Samaras routinely invoked the popular mobilizations for strengthening Athens’ negotiating power. It was also used as an argument to resist pressure by European partners for a compromise: “see the pressure and anger of public opinion” was reportedly an argument typically invoked to foreign officials (Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012, 184–185) by Greek politicians. Thus, a combination of a promise for political-electoral gain and an erroneous perception that maximalism would strengthen Greece’s bargaining power led to unintended political consequences (Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012, 225; Tziampiris Reference Tziampiris2003, 78). As Konstantinos Mitsotakis, the Greek Prime Minister at the time, has put it, “politicians helped create a climate of extreme nationalism and now the public is pushing politicians to go further than they would themselves have liked on Macedonia” (quoted in Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012, 200).

In a matter of only few months, massive grassroot mobilization brought the Macedonia issue to the center of every Greek’s attention. In the process, public opinion and the people’s protests formed the backdrop against which foreign policy outcomes were assessed. The milestone events were the massive rallies in support of the Greek ownership of the name Macedonia and against its “stealing” by neighboring Slavs: first in Thessaloniki in February 1992 and then throughout Greece. The momentary massive gatherings had set the tone. But there was also the widespread and diffuse engagement of virtually every societal group in the same direction of pushing a maximalist agenda on the name dispute: the rejection of any reference to the term “Macedonia” in the name of the newly independent state.

A crucial dimension of the problem was that, once mobilized, the Greek public’s reactions revealed that the whole problem was experienced as something much greater than just a foreign or security problem. The mass mobilization showed that it was a “collective response of people personally affected by the issues at hand, namely their sense of identity and their perception of heritage” (Kofos Reference Kofos and Pettifer1999, 250). Emotionally charged, and perceiving the diplomatic battle as having at stake the very core of its identity and culture, the Greek public and its nationalist entrepreneurs ensured that any divergence of opinion would be portrayed as undermining the struggle for the nation’s survival (Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012; Skoulariki Reference Skoulariki and Kontochristou2007).

Public opinion was influenced immensely by nationalist and populist reporting by the Greek media. The media played a key role in the initial forming of negative stereotypes that confirmed the perception of a nation under threat by aggressive neighbors (Armenakis et al. Reference Armenakis, Gkotsopoulos, Demertzis, Panagiotopoulou and Charalampis1996; Demertzis, Papathanassopoulos, and Armenakis Reference Demertzis, Papathanassopoulos and Armenakis1999; Skoulariki Reference Skoulariki2005; Reference Skoulariki and Kontochristou2007). The period of the Macedonian frenzy coincided with the first “wild” period of the liberalization of the electronic media market. The previously highly controlled public broadcasters that had been the exclusive media vendors, got marginalized by new private TV stations, which aggressively competed for greater portions of the media market. In the process they excelled in biased reporting and stoking the fears of the public over the developments in Yugoslavia and the Macedonia question. Very early on in the name dispute, the entire landscape of electronic and print media framed the name question as an existential battle for the nation’s identity, by constantly repeating nationalist clichés that solidified a perception of a victimized nation under threat (Skoulariki Reference Skoulariki and Kontochristou2007).

Moreover, influential civic actors got involved in the issue, shaping the public perceptions in ways that further reinforced the nationalist sentiment. Among these actors, a central role was played by the official Orthodox Church, which led the popular mobilization against the use of the term Macedonia by the newly independent state. It also actively shaped the public’s understanding of the entire Yugoslav imbroglio in a particular pro-Serb, anti-Muslim, and anti-Western manner, through constant presence in media and by actively using its vast local network in the entire country to propagate and mobilize. The Orthodox Church saw itself as a guardian of the Greek and Orthodox identity under threat. It also seized the opportunity to reverse nearly twenty years of weakening influence in Greek politics and successfully return to political and societal centerstage.

Other conservative and nationalist circles, especially in Northern Greece, mobilized in response to the rekindling of the century-old Macedonian question, which in the past had brought war and instability. Greece’s age-old fear of minority separatism was instinctively recruited as a frame for understanding the new developments, stoking fears and nationalist reactions. Still, it is important to stress that these fears could be identified mostly among local elites and conservative circles in Northern Greece, and not in the rest of the country. The wider Greek public had virtually no knowledge of the complex historical and ethno-political reality of Greece’s North. Its mobilization was rather in response to the elusive sense of threat to their identity and a concern over the territorial integrity of the country, the risk to which was constantly propagated as a possibility by media and nationalist entrepreneurs.

Notwithstanding the initial clear guidance and inducement of the popular sentiment by officials and state institutions (Skoulariki Reference Skoulariki and Kontochristou2007; Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012), soon the decision makers were transformed into followers and prompted to follow the maximalist tone set by public opinion. The official endorsement of this was confirmed during an all-party leaders’ meeting intended to set Greece’s negotiating framework on the name dispute. This antagonistic line was later reaffirmed in a second party leaders’ meeting. This cross-party commitment set a highly constraining framework “for maneuver by all subsequent governments, at least at the level of public discourse” (Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012, 197). Or, to put in extremis, the Greek government was taken “hostage by public opinion” (Voulgaris Reference Voulgaris2013, 134).

The overwhelming influence of public opinion in the decision-making process was acknowledged by top decision makers at the time (Papakonstantinou Reference Papakonstantinou1994; Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012; Tziampiris Reference Tziampiris2003; Kofos Reference Kofos and Pettifer1999; Skylakakis Reference Skylakakis1995; Tarkas Reference Tarkas1995). Both Prime Minister Konstantinos Mitsotakis (Tziampiris Reference Tziampiris2003, 79) and the successor to Antonis Samaras, Minister Michalis Papakonstantinou (Reference Papakonstantinou1994), have openly expressed their frustration about their inability to correct the maximalist policy due to the constraints imposed by an emotional public opinion. Mitsotakis was evidently against the highly emotional involvement of the masses in complex foreign policy issues. In his view, the maximalist stance challenged national interest, which was served better by reaching a quick and mutually beneficial compromise that would stabilize the new state and would prevent the Yugoslav wars from spreading southwards and closer to the Greek borders. But as he claims, in the course of the dispute “things got out of hand. An uncontrollable dynamic was created in the people that showed great sensitivity on this issue. A wave [of popular protest] arose and covered us” (Mitsotakis quoted in Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012, 183, n.11). Mitsotakis went as far as describing the public’s maximalist stance as “group insanity” and “nationalist frenzy”, which pushed Greece into policy self-entrapment (Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012, 183, n.12 & 196). As Tziampiris illustrates, the political leadership failed to change the maximalist position even though it “saw it as a dead end and ineffective policy” (Reference Tziampiris2003, 78).

Τhe maximalist line remained the official position of the Greek government until 2007.Footnote 3 After Samaras’ departure, all efforts at moderating Greek policy seemed to encounter the major obstacle of an obstinate public opinion. Successive preliminary ideas proposed by mediators, and not rejected outright but rather accepted as a basis for negotiations, were along the lines of a compromise, in other words clearly at odds with the official Greek position. Still, Greece’s domestic entanglement meant that every attempt at a diplomatic breakthrough through compromise would clash with the accusations by media and the public for “selling out” and a national treachery (Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012, 197; Skoulariki Reference Skoulariki and Kontochristou2007). In fact, Greece’s first and foremost preoccupation in diplomatic negotiations was ensuring that the issue was removed from the limelight, since “only on the condition that the influence of the popular factor would be diminished and subsequently the amount of political cost would be limited, it was estimated that any negotiation could proceed” (Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012, 216). In practice, maximalism was only damaging Greece’s diplomatic position. The public was applauding the Greek government each time it was acting upon the official maximalist position, but such measures, including the introduction of repeated economic embargoes against the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, were weakening Greece’s diplomatic negotiating hand (Sekeris Reference Sekeris1995). Greece’s weakening diplomatic position was such that by 1993 Athens had accepted as a basis for negotiations a compromise solution previously proposed by international mediators, which included the proposed new name Nova Makedonija (New Macedonia) (Kofos Reference Kofos and Pettifer1999, 247).

For a “protagonist factor” (Tziampiris Reference Tziampiris2003, 70) in influencing Greek foreign policy on the name dispute, public opinion does not enjoy adequate attention in the relevant literature. Classic Greek foreign policy compendiums (Coufoudakis, Psomiadis, and Gerolymatos Reference Van, Psomiadis and Gerolymatos1999; Tsakonas Reference Tsakonas2003b, Reference Tsakonas2003a; Arvanitopoulos and Koppa Reference Arvanitopoulos and Koppa2005), more recent collections (Litsas and Tziampiris Reference Litsas and Tziampiris2017; Valinakis Reference Valinakis2010) or studies on “emerging actors” (Tsakonas Reference Tsakonas2007) do not focus much on the role of public opinion.

Only a handful of studies have engaged with public opinion as a key factor influencing Greek policy on the name dispute. Ioakeimidis (Reference Ioakeimidis and Tsakonas2003), a former expert of the Greek MFA, advances a critical assessment of the Greek foreign policy making process, which, he sees as severely under-institutionalized and crucially dependent on individual leaders. This state of affairs allows public opinion to crucially influence foreign policy, pushing maximalist agendas. For Ioakeimidis, the name issue was a case par excellence where such policy deficiencies were at work. Mavroidis (Reference Mavroidis1999) explored plausible scenarios for the interplay of leadership and public opinion in the Macedonia name dispute. His analysis points to the bottom-up scenario, showing the strong influence of public opinion on policy in the 1990s. Similarly, Tziampiris’ extensive scholarship on Greek foreign policy and the Macedonia name dispute (Reference Tziampiris2000; Reference Tziampiris2003) offers plentiful examples when the increasingly powerful public opinion constrained, if not defined, official policy. However, these studies do not elaborate how the influence of public opinion is measured, how its technical aspects are operationalized, and conclusions about strength and appeal systematized.

2.2 Exploring Past Empirical Data: Greek Public Opinion, 1992–2016

From the start of the name dispute poll data has shown that the overwhelming majority of Greeks refused to accept any name for the new state that would include the term Macedonia. Skoulariki (Reference Skoulariki2005) reports rejection rates ranging from 64.3% to 83.4% between in April 1992 and November 1995. A time series survey for the period 1992–2002 also showed that the rejection of a “composite name” (some reference to the term Macedonia in the country’s name) remained a majority stance throughout. The rejection rate reached record levels of 91.3% at the height of the diplomatic crisis in June 1992. It went down to 65.6% in December 1994, it increased again after the signing of the Interim Accord in 1995, and remained high for the remainder of the decade (details in Kofos Reference Kofos2005, 206–209). A poll commissioned by the Greek Ministry of Defense in 2001 was the only time in the last thirty years when attitudes opposing any reference to the term Macedonia and those favoring a name accepted by both sides seemed to be on equal footing, with 45.4% each (quoted in Kofos Reference Kofos2005). Even in that case it is unclear whether this was a function of the particular phrasing of the question or reflected some momentary, and still unexplored, moderation of the Greek public.

By the mid-2000s, the attitudes of public opinion were again highly uncompromising and remained so until the period of the Prespa negotiations. A December 2004 poll found that 56% of respondents opposed a composite name that would include the term “Macedonia” and 41% supported it (quoted in Kotsovilis Reference Kotsovilis2005, 33). A series of polls in the period around NATO’s Bucharest Summit, when Greece effectively blocked the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia’s entry to the Alliance, showed that the prospect of vetoing Skopje’s accession to organizations enjoyed overwhelming support between 81% and 84% (Pieridis Reference Pieridis and Mavris2010). Moreover, in February 2008, 52% of respondents declared their willingness to participate in rallies about the name dispute (Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012, 367-n.130), more than fifteen years since the controversial mass rallies that cornered the political class into a maximalist position on the issue. When in February 2008 a range of names, all containing the term Macedonia in some form, were polled, respondents’ rejection rates ranged between 53% (by far the lowest) to 86%. The name that would be agreed upon ten years later, North Macedonia, polled at 43% and was rejected by 53% of respondents (Kathimerini, 25-27.2.2008). Finally, it is important to mention that, to the best of our knowledge, there was no reference to the name dispute in polls conducted between 2008 and 2016. That period includes the start and the climax of severe economic crisis in Greece which brought dramatic political and social developments in the country (Marantzidis and Siakas Reference Marantzidis and Siakas2019). The issue is simply entirely absent from the policy agenda and not included in the polls conducted at the time.

An Unprecedented Engagement

The high rejection rates for any compromise do not reveal the full picture of the public’s engagement. Loulis (Reference Loulis1995), reviewing polling data from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s, shows how the popular mobilization around the name dispute heralded an increase in significance of foreign policy issues for public opinion that was unprecedented for many years. Greece had not seen such awareness and involvement in foreign policy issues by the public since the mass demonstrations in support of the Cypriot anti-colonial struggle in the 1950s (Heraclides Reference Heraclides2018b, 173; Kofos Reference Kofos and Pettifer1999, 250).

In June 1992, at the height of the diplomatic battle, foreign policy was for the first time ranked as the 2nd most important problem for public opinion, up from 9th place where it had ranked in November 1991, shortly before the start of the diplomatic battle. Furthermore, in June 1992, the name dispute was considered as the most important foreign policy problem by 60.2% of respondents, dwarfing by comparison the “perennial” problem of relations with Turkey that received only 28.7%. This was despite the fact that, during the same period, public opinion still considered Turkey to be the main threat for Greece at a rate of 63.3%.

The heightened emotions over foreign policy issues toned down in 1994. The importance assigned to foreign policy by public opinion declined as the Greek public grew more frustrated over the realistic prospects of a diplomatic victory. In March 1994, nearly three quarters of Greeks expected that the international community would eventually recognize Skopje under a name that would contain the term “Macedonia” (Loulis Reference Loulis1995, 124). At the same time, with public opinion’s rapidly decreasing interest in the name dispute, Greek-Turkish relations was reinstated as the foremost foreign policy question (Loulis Reference Loulis1995).

Emotionality and Political Implications

The emotional aspect of the problem was clearly manifested whenever it was measured in polls since the early 1990s. In a December 1993 poll, the international recognition of the new state under a name that would include the term Macedonia was described in dramatic terms by over 80% of respondents: 33.9% as a “serious national failure,” 31.1% as a “diplomatic failure,” and 20.5% as a “national disaster,” while a meagre 6.5% did not view such a development as some sort of a tragedy (Skoulariki Reference Skoulariki2005). Skylakaki (Reference Skylakaki2018) also reports that in April 1993 over 90% of public opinion was against the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia’s accession to the United Nations; they described their feelings as “anger” and “disgrace” and considered even the provisional name (FYROM) as a “defeat” and “betrayal,” Overall, especially since the problem was ostensibly not connected to a perceived security threat, “it was not fear or anxiety that was caused by the outburst of the Skopje issue, but some other factors that touch the emotion, and which turned this issue into a nationwide crusade” (Loulis Reference Loulis1995, 127).

No less than fifteen years later, and around the time when the diplomatic clash at NATO’s Bucharest Summit took place, two successive polls (February 2008 & October 2008) asked about sentiments that a potential Greek recognition under the name Macedonia could generate (in the October 2008 poll as “North Macedonia”). The responses were “rage and anger” by rates of 34% and 21%, “sadness and grief” by 28% and 35%, and “shame” by 22% and 14% in February 2008 and October 2008, respectively. Sentiments “indifference” and “relief” scored very low, though still much better in October 2008 when combined they reached 24% (Kathimerini 25-27.2.2008 & 10.10.2008).

A final point of interest here is that in the rare occasions when it was measured, the Greek public’s frustration with the failure to achieve maximalist goals appeared to correlate with assigning responsibility to and turning against their political class. In December 1992, 38.8% of respondents assigned responsibility to all Greek governments for their policies in dealing with the Macedonian issue, while in January 1994, when the diplomatic failure of Greece was becoming more evident, this view went up to 69.6% (Panagiotopoulou Reference Panagiotopoulou1996). In March 1994, when nearly three quarters of respondents expected that the international community would eventually recognize Skopje under a name that would contain the term “Macedonia,” seven in ten respondents apportioned the blame for this failure to their political leadership (Loulis Reference Loulis1995, 124; Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012, 235). Several years later, in 2007, almost four in five Greeks (79%) believed that the Greek governments had not managed the Macedonia name dispute satisfactorily since the 1990s (Pieridis Reference Pieridis and Mavris2010). Back in the early 1990s, the Greek public, which had traditionally been pro-European, appeared to be severely estranged from Greece’s European partners. In a May 1994 poll, nearly nine in ten Greeks assessed European partners’ stance towards Greece as being “hostile,” “wary,” “critical,” or “indifferent,” with the positive evaluations being under 10% (Loulis Reference Loulis1995, 125–126, 134).

3 Greek Public Opinion as an Obstacle to the Settlement of the Name Dispute: Empirical Evidence

3.1 Operationalizing the Measurement of Greek Public Opinion in the Name Dispute

We focus here on three key dimensions of public opinion’s involvement in foreign policy questions and investigate them against the backdrop of the Greek public’s attitudes on the Macedonia name dispute. Firstly, following Powlick and Katz’s (Reference Powlick and Katz1998) “activation model,” we examine issue salience. International matters are significant for the public in varying degrees. Some issues have higher importance, while others remain insignificant. And some issues will shift from unimportance to prominence and vice versa. Thus, for public attitudes to matter, salience is of the essence. Otherwise, public opinion could be easily disregarded by decision makers (Doeser Reference Doeser2013). The salience of an issue is the activator or the booster that brings the focus on a specific topic. When it comes to the name dispute, the salience is not easily extrapolated. As we saw above (Loulis Reference Loulis1995), there is enough evidence for issue salience during the highpoint of the diplomatic battle during the first half of the 1990s. There is also scattered evidence that the matter continued to be prominent in the following twenty years. But whether an issue, which remained unresolved but was low on the policy agenda for two decades, could maintain public opinion salience to significantly matter has not been investigated heretofore. In this study we present data measuring the extent to which the name issue was perceived as salient by public opinion as well as the threat perception it generated.

Secondly, following Eichenberg (Reference Eichenberg and Eichenberg2016) we scrutinize the actual content of attitudes by exploring the actual public opinion beliefs on the matter. The cursory view, which was reiterated on various instances, was that the Greek public held a rigid stance on the name dispute. This perception, however, was largely based on anecdotal understanding of the Greek sentiment, without anyone ever dissecting in depth the attitudes of public opinion on the matter. The lack of clarity could be explained by the dearth of scholarly studies actually measuring the public’s true views on the matter. Even if one were to assume a degree of rigidness on the part of public opinion, much remained to be accounted for, what was the extent of rigid public attitudes on the issue?

Thirdly, following Shapiro and Page (Reference Shapiro and Page1988; Reference Shapiro and Page1983) as well as Isernia et al. (Reference Isernia, Juhász and Rattinger2002), we explore the coherence of public opinion on the name dispute by examining issues of consistency. Two core issues can potentially be put to scrutiny. The first core issue concerns time coherence, which could focus on variation across time and over the lifespan of this diplomatic discord. As we have seen above, despite the lack of a single longitudinal survey covering the topic since the early 1990s, there is sufficient evidence to highlight a consistent rejection of the compromise on the name dispute by the majority of the Greek public for the entire period since 1991. Despite the partial and not-always-comparable data, an overall, across time, outlook points to consistency in rigid and uncompromising attitudes. The second core issue concerns public opinion’s internal coherence. This issue questions the homogeneity of attitudes across population subgroups. The data presented in this study allow us to delve deeper and infer whether at the particular point in time, which in retrospect we may consider as crucial for the settlement of the dispute, Greek public opinion attitudes were uniform or at least exhibited considerable similarity across a wide array of sub-groups in society.

3.2 Evidence from a Comprehensive Survey on the Name Dispute

The data we analyze come from the first ever comprehensive survey in Greece focusing entirely on the name dispute and exploring nationwide attitudes and beliefs. The survey took place between February and March 2016 on a sample of 1000 adults, age 18 and above in all the geographic regions of Greece (Armakolas and Siakas Reference Armakolas and Siakas2016). The mode of the data collection was Computer Assisted Telephone Interviews (CATI) and the sample design was based on multistage stratified sampling. The survey was conducted in a period that could be considered neutral, as no significant event or series of events related to the issue had occurred. Still, the survey offered information about the attitudes of public opinion a few months before the issue was re-introduced in the policy agenda, and while no noteworthy political developments related to the issue had occurred between data collection and the renewed focus on the name dispute.

The three issues under exploration – issue salience, the position or actual content of beliefs, and coherence of these beliefs – were measured by closed-ended questions. The design of the questionnaire followed the “concept towards items” approach (Krosnick and Presser Reference Krosnick, Presser, Marsden and Wright2010; 2003). In particular, issue salience was measured by closed-ended questions on an item response format related to the imminent character of resolving the issue. Regarding the format of the questions, respondents were asked to identify the perceived importance of the matter and if it should be resolved the soonest possible; potential answers included a four items scale, with response items “very, somewhat, neutral, and not at all important”. Following, respondents were asked whether they consider that any delay on the solution is harmful for Greece’s interests, with a Yes/No format. Additionally, in order to identify the threat factor respondents were given the statement, “Some people express fear that the use of the term ‘Macedonia’ as part of the name of the neighboring country may constitute a future territorial threat for our country” and they were asked to place themselves using the Strongly Agree/Strongly Disagree continuum. The rationale behind this question is that this argument in the affirmative, often uttered in the exact same words, is a standard position heard in public discourse in Greece and by the Greek diplomacy in international contexts.

The position on the matter was measured using an item-specific question with three mutually exclusive options. The respondents were asked to endorse their preferred solution among the following options: (a) the rejection to any reference to the term Macedonia as part of the name of the country, (b) the acceptance of a composite name with a geographic qualifier, and (c) the acceptance of the constitutional name “Republic of Macedonia.” After data collection, the above three items were encoded to two options: (a) remained as the measure of the “non-compromising” stance, while (b) and (c) were combined to measure the “compromising” stance. Finally, respondents were asked to offer their assessment on the neighboring country, indicating a positive, negative, or neutral opinion.

Finally, in order to measure the coherence, the survey considered data from demographic questions (age, gender, education, geographical region) as well as questions about self-identification on the Left-Right axis in order to detect differences across groups. Specifically, for the Left-Right placement, we argue that the distinction can add nuance to the analysis of the data, especially given the existence of some divergence in positions of Greek parties on the Macedonian question as well as the Left-Right polarization in Greece that is also reflected in attitudes over public policies.

Issue Salience

Greek public opinion considered the name issue as a matter of great importance and supported the imminent resolution. In particular, 58% of the respondents believed that the issue is “extremely important” and 19% that it is “somewhat important,” while in contrast only 10% stated that it is “not important at all.” Also, 71.5% believed that any delay on the solution harms Greece’s interests. Moreover, the Greek public considered the use of the term Macedonia may constitute a future territorial threat for Greece. Specifically, 42% strongly agreed and 13% somewhat agreed with the future threat statement. In short, public opinion perceived the name issue not only of symbolic emotional and historical meaning but also as a potential future security threat.

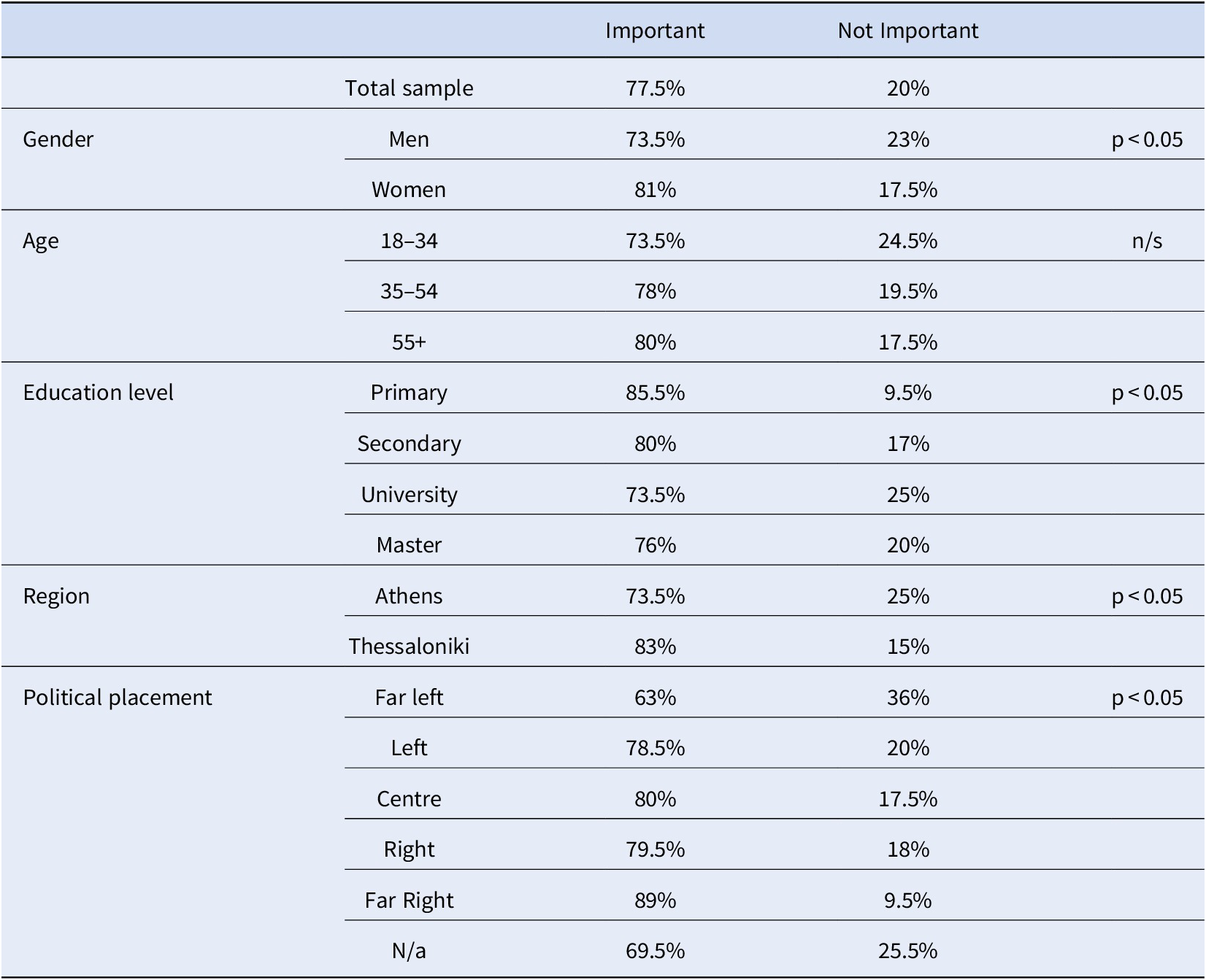

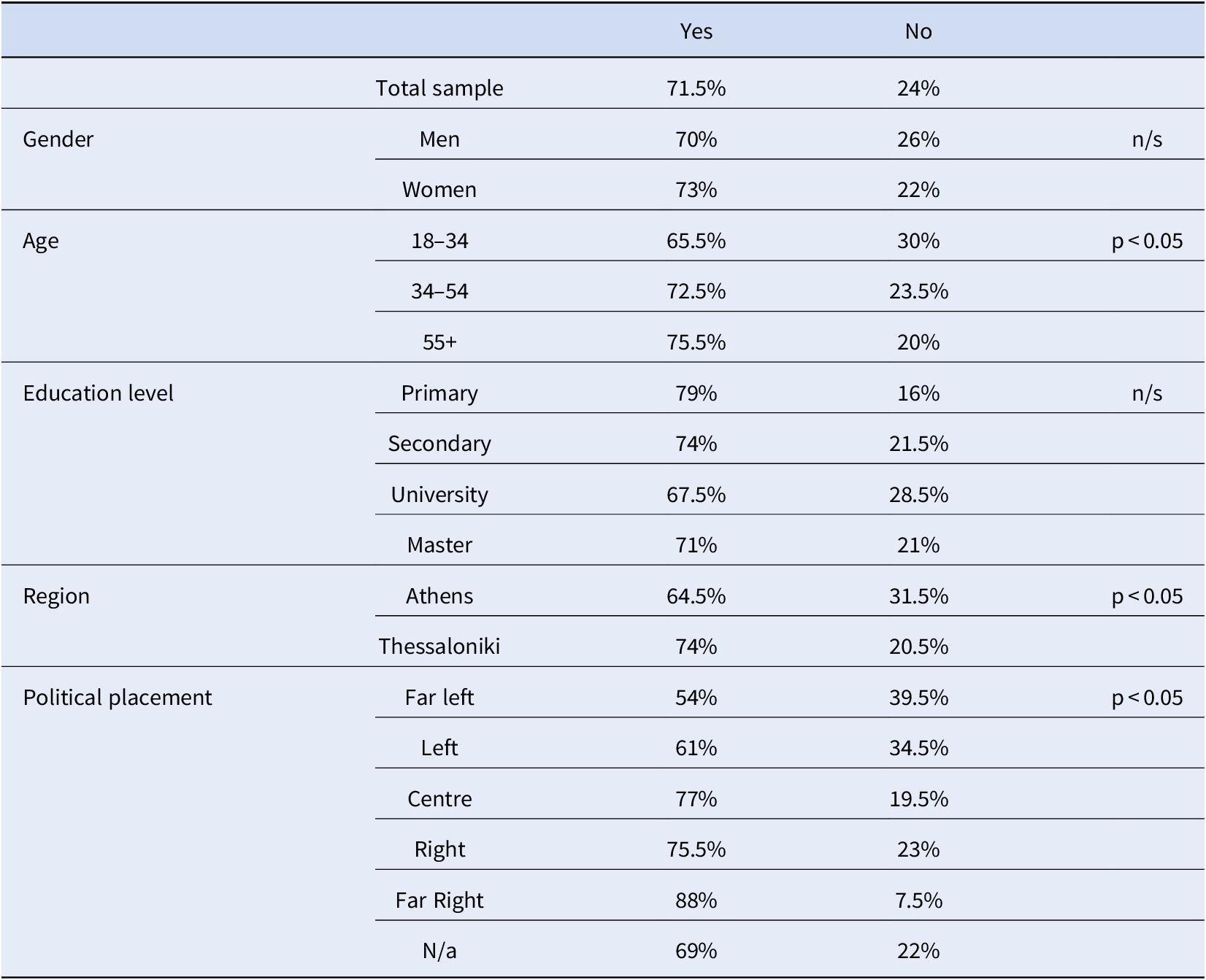

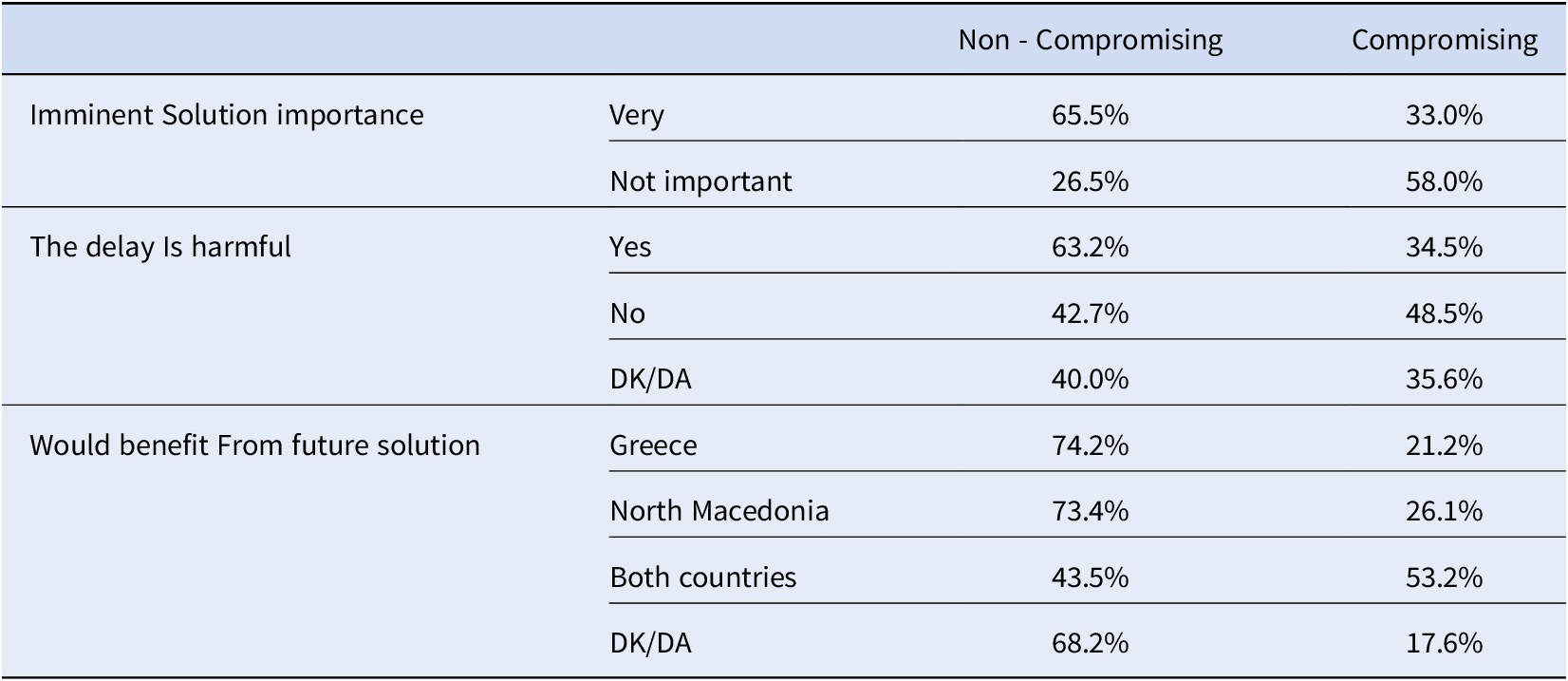

Table 1 presents the findings of the salience argument, along with the groups’ comparison on the grounds of statistical significance. Specifically, the association with gender (χ2 = 8.89, df = 1, p < 0.05), educational level (χ2 = 18.67, df = 6, p < 0.05), and region – between Attica and Thessaloniki – (χ2 = 6.34, df = 2, p < 0.05) present statistical significance, whereas age groups comparison fails to pass the test. The findings of the delay argument are presented in Table 2. The delay argument is associated with age groups (χ2 = 9.73, df = 4, p < 0.05), as elderly people tend to support more the view that any delay harms Greece’s interests, and region of residence (χ2 = 6.63, df = 2, p < 0.05). The association of the region is present on the two first factors, while it does not establish any correlation with the threat factor. This strong association of the arguments on the harmful character of the delay as well as the salience of the issue has strong face validity. Unsurprisingly, people in Northern Greece were more sensitive towards the issue.

Table 1. “How important is it to address immediately the naming issue?”

Table 2. “Do you think that the delay in the resolution of the name issue is harmful to Greece?”

The territorial threat question presents a similar variation. Particularly, it presents statistically significant association with gender (χ2 = 12.46, df = 3, p < 0.05), age (χ2 = 15.32, df = 6, p < 0.05), educational level (χ2 = 19.96, df = 9, p < 0.05) but not with the region of residence. As depicted in Table 3 the threat factor is supported more by women, rather than men, by respondents in the age group 35-54 and those who have completed secondary education.

Table 3. “The use of the word Macedonia in the name of the neighbor country could result in a future territorial threat.”

Position

Respondents were asked to choose among three options, each of which represented a different preference of a potential solution. 57% of respondents rejected any use of the term Macedonia in the name of the neighboring country. A composite name containing the term Macedonia was endorsed by 28% of respondents, while another 10% opted for accepting the country’s constitutional name “Republic of Macedonia.” Only 5% chose no answer/do not know. After classifying the three options into two categories, the balance between uncompromising and compromising attitudes was found to be 57% versus 38%. It is important to recall that this 57% majority of the population were at odds with the official position of the Greek government, which since 2007 had opted for the compromise of accepting a composite name with a geographic qualifier

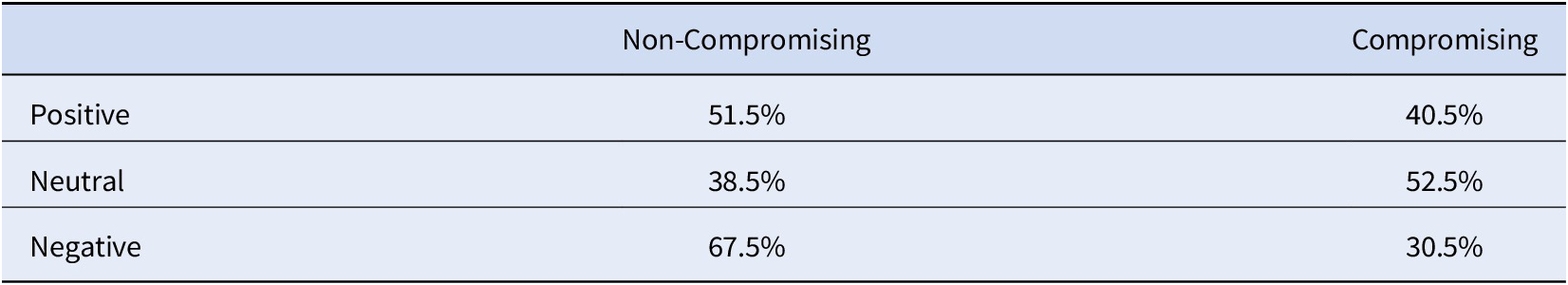

In a different setup, respondents were also asked to provide a general positive or negative assessment of the neighboring country. The majority shared a negative attitude towards North Macedonia: 61.5% negative and very negative, 29.5% neutral and 7.5% positive and very positive. These three approaches could also be related to the position towards the solution efforts. As we notice in Table 4 the only category that supports a compromise solution are those respondents who adopt a neutral position towards North Macedonia.

Table 4. Public opinion stance towards potential solutions, according to the overall outlook towards North Macedonia.

Coherence

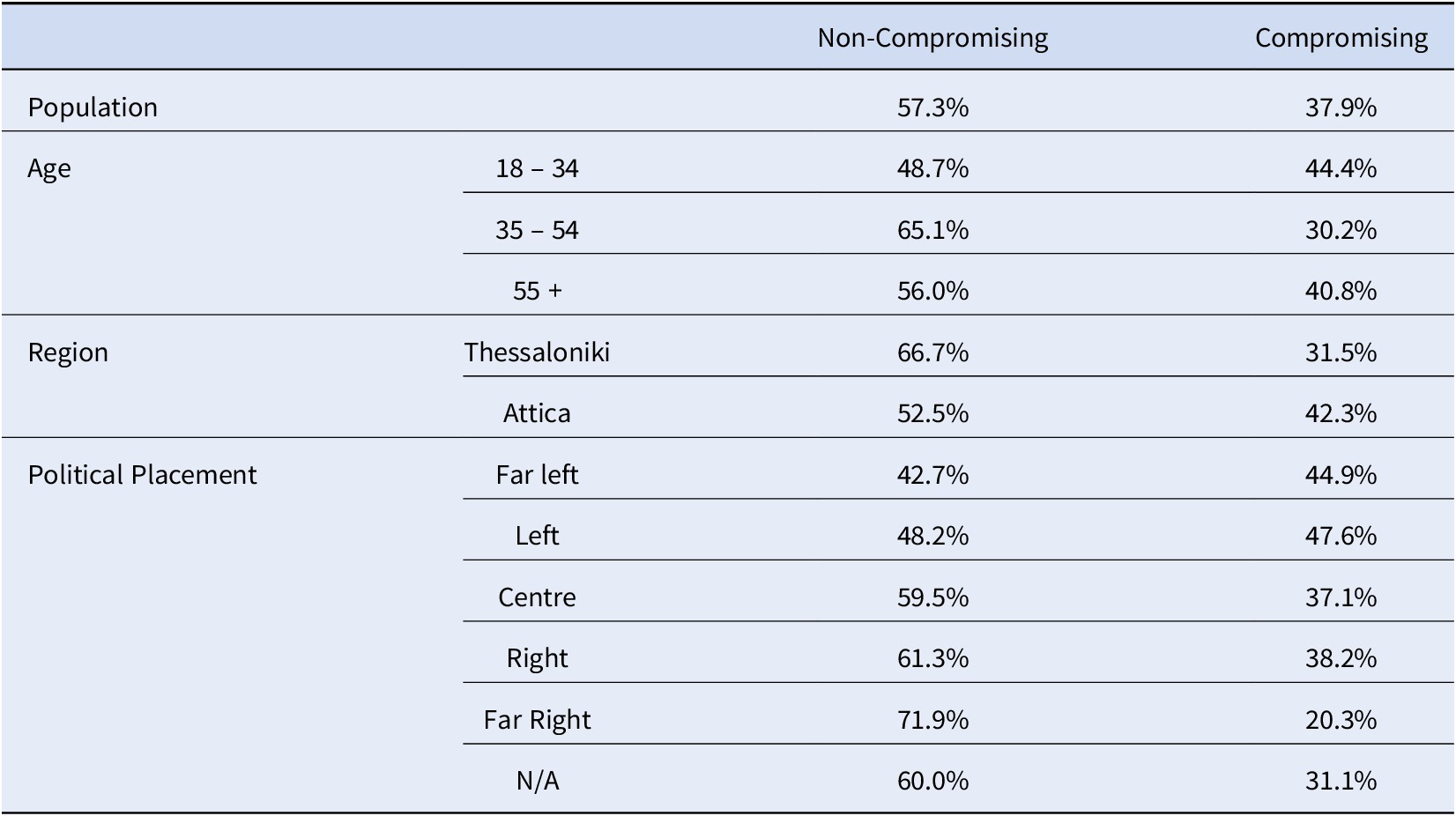

We have identified some degree of homogeneity of opinion across population subgroups, however with some important divergencies. Indeed, as shown in Table 5, age and solution views seem to be associated (χ2 = 16.80, df = 2, p < 0.05). Younger generations are more amenable to a solution, as the accommodating stance meets its highest percentage in younger age respondents (18–34). On the contrary, the lowest rates are in the age group 35–54. The difference could be attributed to the varying exposure to high profile media coverage and political events related to the issue, such as mass rallies and grassroots mobilization. Besides, the age group 35-54 was in their highly formative years in the 1990s when the issue was high in the policy agenda. Additionally, the uncompromising attitudes in all three groups constitute the majority. But compromise for the younger cohort is more popular by about 50% compared to the middle age cohort. Moreover, the gap between the two stances (compromising versus uncompromising) is about 4% for younger respondents, while it reaches about 35% in the 35–54 group.

Table 5. Contingency tables for variables of statistical significance (p<0.05).

No association to the solution could be established with gender and educational level. In other words, respondents are uniformly against a compromise solution irrespective of their gender or educational level. Conversely, respondents’ area of residence and solution views seem to be associated (χ2 = 6.65, df = 1, p < 0.05). Particularly, divergence of scale between residents of Thessaloniki and Athens were found. Majorities in both cities were against a compromise solution, but the rejection rates in Thessaloniki were much higher. Also, a noteworthy difference is related to the Left-Right axis self-placement. Respondents that placed themselves on the left side of the axis adopted a less rejectionist approach than the ones placed on the right side. Indeed, the Left-Right placement and attitudes towards a solution are associated (χ2 = 20.78, df = 5, p < 0.05). Still, the respondents of far-left self-placement were the only ones with a small majority for compromise, while even respondents self-identifying with the left supported marginally more the non-compromise. Moving towards the right side of the Left-Right (LR) spectrum the uncompromising positions were more rigid, as the opposite applies on the left side of the spectrum. Respondents that refused to place themselves into the LR placement present a higher uncompromising stance compared to the average population mean (66%).

The perceived importance and the imminent character of the solution were associated with solution perspectives. All three variables were statistically significant (a. χ2 = 107.28, df = 4, p < 0.05, b. χ2 = 22.99, df = 2, p < 0.05, c. χ2 = 101.03, df = 3, p < 0.05). In particular, people who considered the name solution of extreme importance adopted the most uncompromising stance (72.6%), whereas the most compromising one was expressed by those who did not consider the issue of great importance (70.4%). On reflection, this could be interpreted more as an apathetic stance rather than an actual involvement in the issue. So, the principal driver here is the insignificance of the issue, rather than the actual belief that the issue should be resolved, and that the way of resolving it is by a mutual compromise. Nevertheless, these groups are not of equal importance as the most popular choice is anyway the non-compromise, endorsed by 57.3% of the population.

Apart from different demographic categories, deviation from the general attitude could be reported with respect to differentiation of the perceived issue salience. As the perceived importance increases, the rejectionist approach also levels up. As reported in the Table 6, those who supported that the on-going dispute harms Greece adopt a more rigid stance comparing to those that do not share the same view. Also, a different view is reported by those who consider the issue as somewhat important. Finally, only those who consider that both countries would mutually benefit from a solution are, by a rate of 53.2%, ready to accept a compromise solution.

Table 6. Contingency tables of perceived importance variables (p<0.05).

Summarizing the empirical findings, we can draw the overall conclusion that the Greek public opinion showed clear evidence of a serious obstacle to the settlement of the Macedonia name dispute at the outset of the negotiation process. Beyond the partial and anecdotal data that informed analysts’ understanding of the Greek public on past occasions, our data illustrate the significance of Greeks’ opposition. By comfortable majorities, Greek public opinion stood against any compromise on the Macedonia name dispute and remained highly rigid in its stances. Furthermore, these rejectionists were coupled with a perception of the issue as being highly salient. Finally, the findings illustrate that the rejectionist attitudes were to a large extent coherent across most population sub-groups, however with few notable exceptions.

Overall, we conclude that in the period not long before the start of the negotiations for settlement, Greek public opinion remained highly rejectionist. During the decade since the NATO Bucharest Summit not much had changed in the attitudes of the Greek public, which continued to oppose a compromise and continued to consider the name dispute as a highly important problem.

Conclusions and Implications for Research

This article discussed the role of Greek public opinion on the Macedonia name dispute. Repeated “snapshots” of the mood of public opinion since the early 1990s point to a particular direction when it comes to what the Greek public thought. Nonetheless, nearly three decades since the start of a dispute that captured the public imagination and enflamed popular sentiment, there had been no comprehensive investigation of how it was influenced by public attitudes.

We engaged in a theoretically informed investigation of public opinion at the critical moment, not long before the onset of negotiations that led to the settlement. Our analysis showed that Greek public opinion maintained a pattern of attitudes and the dynamism to turn public support into a critical parameter. As a result of the emotional character and high salience of the issue, uncompromising attitudes, and population sub-group coherence, public approval of the negotiations clearly became one of the largest challenges to the solution of the problem. The findings also partly explain the highly polarized debates during the period of negotiations, as well as the high levels of citizens’ mobilization.

The above findings also illustrate that one of the possible defining factors in political parties’ strategic assessment and tactical moves, between government and opposition as well as intra-government, could have been the divergent attitudes on the issue, on the basis of respondents’ self-placement in the Left-Right continuum. This dimension likely set the parameters for the highly polarized party wrangling in the last couple of years. For example, issue salience differed between respondents of the right and those of the left. Similarly, this is also partly the case for the actual content of attitudes, as left-wing respondents were more accommodative than the people placed on the right side of the spectrum.

In strategic terms, this could partially explain different tactical approaches in the political game during and after negotiations on the settlement of the dispute. The parties of the right would be expected to react to a potential compromise, as their electorate was evidently much more sensitive to this issue. In contrast, left wing parties could have a different approach, as their electorate was more open to a potential compromise solution. Moreover, the audience of the left was more susceptible to leadership influence, once the strategic decision to push for a settlement was made within the government. This issue also points to the background of the divergent approaches that the two governing coalition parties (leftist Coalition of the Radical Left-SYRIZA and right-wing Independent Greeks) had on the issue, since their electoral audience largely diverged in Left-Right identification.

The above findings also point to avenues for future research. Given the highly constraining factor that public opinion was expected to be, even with the caveat of Left-Right partial divergence, more research is required for understanding the process that led the Greek government to the decision to resolve the Macedonia name dispute. Surely, considerations of the overall political strategy, international dividends, and personal political calculations have to be considered. Moreover, more research will be required to understand the particular effects of polarization in Greek politics and society and how this has impacted, or may impact in the future, foreign policy decision making. It will be interesting, for example, to understand why and how the Greek government of the time refused to seek consensus and instead opted for a political strategy of confrontation with the opposition (Triantaphyllou Reference Triantaphyllou2018), despite clearly negative trends in public opinion (Armakolas and Siakas Reference Armakolas and Siakas2016; Reference Armakolas and Siakas2018).

Another research path may be to investigate the factors and processes that maintained issue salience as well as uncompromising attitudes, despite the fact that the Macedonia name dispute had remained very low on the policy agenda for years. There are analyses that have shown that the lack of open and sincere debate about the issue, as well as the refusal to challenge the “sacrosanct” original maximalist aim, have had the effect of keeping public opinion highly rigid (Skoulariki Reference Skoulariki and Kontochristou2007; Kalpadakis Reference Kalpadakis2012). But more research is required to establish this thesis, and especially for elucidating the mechanism at work and the interactions between foreign policy planning, elite considerations, and public attitudes. Similarly, more research beyond the few existing works (Heraclides Reference Heraclides2018b; Triantaphyllou Reference Triantaphyllou2018) is needed to explicate the process that creates ethnocentric biases in the way that the Greek public perceives foreign policy issues. As a result of the latter, maximalist positions are typically considered natural and justified, while any compromise or backpedaling is considered at best a failure, or even national treason. The same quest would also have interesting theoretical implications. In the relevant literature outlined above (for example Powlick and Katz Reference Powlick and Katz1998), the scholarly emphasis is on the triggers that initially mobilize public opinion over international problems, and less on the factors that sustain its engagement and interest for longer than would be expected by policy makers.

Disclosures

Authors have nothing to disclose.