Introduction

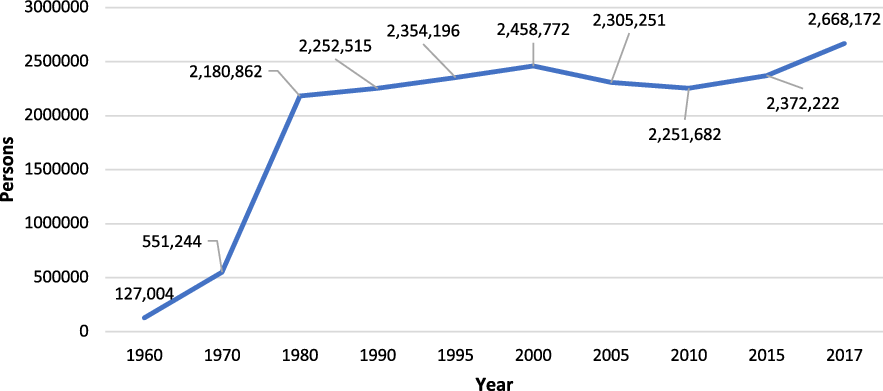

A migration destination is the best place among different possible locations that can more-or-less satisfy all of a migrant’s potential needs, i.e. the place offering the highest expected utility (Geis et al. Reference Geis, Uebelmesser and Werding2015). For decades, besides countries like Australia, Canada, the USA, and those in the Gulf, Europe has been a popular migration destination for Turkish people (İçduygu and Kirişçi Reference İçduygu, Kirişçi, İçduygu and Kirişçi2009). Turkish migration stock (by country of birth) in EU member states has been increasing since 1960 (UNDESA 2017b; World Bank 2011): in 2017 there were 2,668,826 peopleFootnote 1 from Turkey in the EU-28 (see Graph 1), with more than 1.5 million in Germany alone.

We hypothesize that the favorable labor market conditions in the destination is no longer the strongest driver of the migration destinations of Turkish citizens. Instead, security-based, social, and geographical drivers may also play a key role. This article empirically investigates the main motivations for Turkish people to migrate to EU destinations and contributes to the literature by paying special attention to Turkish newcomers in the twenty-first century.Footnote 2

Unlike previous studies (Dedeoğlu and Genç Reference Dedeoğlu and Deniz Genç2017; Fafchamps and Shilpi Reference Fafchamps and Shilpi2013; Jennissen Reference Jennissen2003; Mayda Reference Mayda2010; Nica Reference Nica2015; Pânzaru Reference Pânzaru2013; Tabor et al. Reference Tabor, Milfont and Ward2015; Van Der Gaag and Van Wissen Reference Van Der Gaag and Van Wissen2008; Winter Reference Winter2019) which relied on migration stock data, this article aims to identify the relevant drivers of Turkish migrants’ EU destinations in the 2000s and 2010s using migration flow data at the macro level. The scope is limited to Turkish people in the EU-28 who obtained their first long-term residence permits (i.e. for more than 12 months) between 2008 and 2018, the longest period data permits. The article uses evidence-based research through security-based, labor market, social, and geographical drivers blending data from Eurostat, UNDESA, the OECD, and the World Bank. The regression analysis shows that Turkish newcomers are mostly attracted to EU countries because of social networks and a demand for democracy.

The next section reviews the literature, after which the focus turns to the history of migration from Turkey to Europe in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Then the method and data are described. The findings are presented and discussed before the conclusion is presented in the final section.

Literature review

The drivers of choosing a migration destination

Several studies (De Jong and Gardner Reference De Jong, Gardner, De Jong and Gardner1981; Faist Reference Faist2000; Hagen-Zanker Reference Hagen-Zanker2008; Hemmerechts et al. Reference Hemmerechts, De Clerck, Willems and Timmerman2014) have categorized the drivers of migration decision as follows: (1) societal-level (macro) studies explain aggregate migration trends as a part of the social, political, and economic development of a country; (2) household-level (meso) studies link migration cause or perpetuation to household or community based on social ties and networks; and (3) individual-level (micro) studies examine individual values, desires, and expectations focusing on the cost-benefit calculation of potential immigrants. Since this article focuses on the macro level, it adopts the word “drivers” commonly used for the macro level analysis (Carling and Collins Reference Carling and Collins2017). Based on these works (Carling and Collins Reference Carling and Collins2017), we adopt Dudu’s (Reference Dudu2018) re-categorization which divides the characteristics of migration destinations into four groups: security-based, labor market, social, and geographic drivers (see Figure 1).

Security-based drivers

Security-based drivers have links with migration caused by obligations (human insecurity) due to the public or private actions (like war conditions, slavery, and human trafficking) and environmental disasters (like climate change or destructive earthquakes) (Dudu Reference Dudu2018; De Jong and Gardner Reference De Jong, Gardner, De Jong and Gardner1981; George Reference George and Clifford1970). A valid legal residence status is a security measure (Eurostat 2011) that eliminates the fear of deportation (Fasani Reference Fasani2014). Gaining a legal residence document is easier in a destination country with an open border immigration policy (Bartram Reference Bartram2010; Velasco Reference Velasco2016), therefore, potential immigrants may consider a country’s immigrant-friendly policies when choosing a destination (Carling Reference Carling2002; Ozcurumez and Yetkin Aker Reference Ozcurumez and Yetkin Aker2016). An immigrant with a work permit can enjoy the opportunity to work, unemployment benefits, and bargaining power over wages and working conditions (Bailey Reference Bailey1987; Fasani Reference Fasani2014; Kossoudji and Cobb-Clark Reference Kossoudji and Cobb-Clark2000; Rivera-Batiz Reference Rivera-Batiz1999).

Despite the visa restrictions, “a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country based on their race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group” (UNHCR 1951) is the reason for seeking asylum. However, these people can also apply for long-term residence permits abroad if they meet the requirements.

Running away from social and/or political pressure is a strong security-based migration motivation. For example, LGBTQ+ people may want to leave their home countries due to social pressure and choose a country with broader democratic rights. Similarly, highly skilled women suffering from gender inequalities may decide to migrate abroad (Elveren and Toksöz Reference Elveren and Toksöz2019). Some minority groups might face social exclusion such as alienation and lack of freedom (Bhalla and Lapeyre Reference Bhalla and Lapeyre1997) and social coercion, that is, the constraint experienced as a result of people’s attitudes and opinions (Aseh Reference Aseh1955; De Crespigny Reference De Crespigny1964), which hinder their participation in daily social and economic activities (Chakravarty and D’Ambrosio Reference Chakravarty and D’Ambrosio2006). People may wish to emigrate to a country where they can avoid social exclusion (Abrahamson Reference Abrahamson1995), even if this means becoming a minority multiple times (e.g. being an immigrant LGBTQ+).

People may desire to immigrate when their home country does not provide democratic conditions—the right to be protected, the right to participate in the political process, and the right to equal status (Cedefop 1998; Lawson Reference Lawson1991; Sirkeci and Eroğlu Utku Reference Sirkeci and Eroğlu Utku2020). Escape through emigration from social coercion and political oppression is related to identity (Benson and O’Reilly Reference Benson and O’Reilly2016) because of the emigrants’ desire to express themselves freely.

The EUMAGINE project conducted a survey and in-depth semi-structured interviews in Morocco, Turkey, Ukraine, and Senegal between 2010 and 2013. The results demonstrated the role of perceptions on human rights and democracy over migration aspirations (Carling and Schewel Reference Carling and Schewel2017; Hemmerechts et al. Reference Hemmerechts, De Clerck, Willems and Timmerman2014). It showed that the EU has a positive image in terms of democracy and human rights in the migration-impacted districts of Turkey (Timmerman et al. Reference Timmerman, Hemmerechts and De Clerck2014).

Labor market drivers

The labor market drivers are more employment opportunities, higher wages, lower cost of living, and better working conditions (like fewer working hours) (Tabor et al. Reference Tabor, Milfont and Ward2015). According to Jennissen (Reference Jennissen2003), Keynesian economic theory attributes international migration to employment rate differences (Piore Reference Piore1979), while neo-classical economic theory (Sjaastad Reference Sjaastad1962) explains it as the consequence of wage differences, which lead to differences in income (Harris and Todaro Reference Harris and Todaro1975).

Social drivers

Social drivers include cultural similarities. For example, interviews with people who migrated from the UK to New Zealand revealed that cultural similarities affected the migration destination. They believed that living in New Zealand is similar to living in the UK due to the cultural overlap, but ultimately life there is better than in the UK (Tabor et al. Reference Tabor, Milfont and Ward2015).

Another advantage for easier adaptation is speaking the language of the destination country or having linguistic proximity between the immigrant’s language and the language of the destination country so as not to face a language barrier (Eurostat 2009; Tabor et al. Reference Tabor, Milfont and Ward2015). If newcomers cannot speak the primary language in the destination country, then they generally work in the enterprises of earlier immigrants from the same region. These migration networks can help the newcomer integrate more quickly (Dudu Reference Dudu2018).

Migration networks are created through kinship or cultural ties (Guilmoto and Sandron Reference Guilmoto and Sandron2001; Hagen-Zanker Reference Hagen-Zanker2008). Such networks help newcomers to adapt by providing support regarding jobs, housing, education, and cultural issues (Beine et al. Reference Beine, Docquier and Özden2010). Another feature of migration networks is remittances from the destination to the origin country (Day and İçduygu Reference Day and İçduygu1999). Migration networks also provide information to newcomers before they arrive (Hagen-Zanker Reference Hagen-Zanker2008; Roseman Reference Roseman1983).

Geographical drivers

A moderate climate (De Jong and Fawcett Reference De Jong, Fawcett, De Jong and Gardner1981; European Commission 2006; Lee Reference Lee1965; Tabor et al. Reference Tabor, Milfont and Ward2015; Thompson Reference Thompson2017) and environmental quality, including landscape (Berger and Blomquist Reference Berger and Blomquist1992; Tabor et al. Reference Tabor, Milfont and Ward2015), cause retirement migration from powerful economies to countries with moderate climates to reduce the risks of living on a low retirement income (Karakaya and Turan Reference Karakaya and Turan2006; Özerim Reference Özerim2012; Südaş Reference Südaş2009; Williams et al. Reference Williams, King and Warnes1997). It also includes lifestyle migration, which refers to migration to achieve a more fulfilling lifestyle (Torkington Reference Torkington2010). For example, UK citizens living in Portugal’s Algarve region have migrated for lifestyle reasons, including a moderate climate, slower pace of life, healthier diet, more sociable culture, and more leisure opportunities (Torkington Reference Torkington2010). Interestingly, Turkish migration stock in the Mediterranean-European countries like Italy, Spain, and Portugal—presumably attractive due to their moderate climate—has been increasing slowly but steadily in recent years (UNDESA 2017b).

The destination choice is also affected by the distance between the destination and the country of origin (Dedeoğlu and Genç Reference Dedeoğlu and Deniz Genç2017). Distance increases travel costs and time, and limits the available means of transportation. Thus, a nearby destination country may be attractive for feeling close to the home country, while a potential immigrant is more likely have options to travel by road, rail, or sea.

Modeling the drivers of migration destinations

Linear regression is a commonly used technique for modeling migration destination (Rogers Reference Rogers2006). Some studies (Nica Reference Nica2015; Pânzaru Reference Pânzaru2013; Winter Reference Winter2019) showed the importance of economic drivers such as the cost of living, income opportunities, GDP, and the unemployment rate. Others (Geis et al. Reference Geis, Uebelmesser and Werding2015; Mayda Reference Mayda2010; Tabor et al. Reference Tabor, Milfont and Ward2015) demonstrated the significance of non-economic factors such as quality of life, safety, environment, and cultural similarity, as well as a migrant-friendly perception, good education and health systems, and the existence of migration networks.

Dedeoğlu and Genç (Reference Dedeoğlu and Deniz Genç2017) examined Turkey as a home country, focusing on migration drivers for 31 European destination countries. They drew on the gravity model, which emphasizes distance over migration destinations. Their main findings were as follows: better economic conditions strengthen Turkish nationals’ migration to that country; populations in the home and destination countries increase migration stock; Turkish migration stock in Europe significantly influences the migration choices Turkish nationals make; and “volume of immigration decreases with distance and conversely increases with contiguity” (Dedeoğlu and Genç Reference Dedeoğlu and Deniz Genç2017, 14).

Migration destinations: history of migration from Turkey to Europe

Turkish migration stock (by country of birth) has been increasing in EU member states since 1960 (UNDESA 2017b; World Bank 2011). Historically, this migration flow was stimulated by demand for labor, predominantly in Germany due to the “guest-worker scheme” of 1961 (Abadan-Unat Reference Abadan-Unat2017; Çağlar and Soysal Reference Çağlar and Soysal2003; Erdoğan Reference Erdoğan2015; Toksöz Reference Toksöz2006), which allowed workers to migrate for as long as there were jobs for them, on the condition that they returned to their home countries when demand dropped (Hansen Reference Hansen2003), but also in other countries like France (in 1965), Austria (in 1964), the Netherlands (in 1964), Belgium (in 1964), and Sweden (in 1967). The Turkish government of the 1960s thought that this agreement provided an opportunity to increase Turkey’s skilled labor force by its predominantly low-skilled workers undergoing training in Germany (Abadan-Unat Reference Abadan-Unat2017), while increasing Turkey’s remittance earnings (Martin Reference Martin2012). These agreements are one reason for these countries’ large Turkish populations today. After Turkish workers came to Europe, applications from Turkey for family reunifications increased.

During the 1970s, however, Turkish immigrants to Europe were equally motivated by political as by economic factors due to conflict between the political left and right. Escalating political polarization in Turkey led to the 1980 military coup, and in that year alone, more than 60,000 people applied for asylum in the EU-15, almost all of whom (59,424 people) chose Germany as their destination (Sirkeci and Esipova Reference Sirkeci and Esipova2013; UNHCR 2001). Given that potential immigrants tend to prefer a destination country with a strong migration network, they may have preferred Germany because of its massive Turkish migration stock (75 percent of the total number in Europe) (UNHCR 2001).

In the mid-1980s, a conflict erupted in Turkey between the Turkish government and the separatist militant Kurdish Workers’ Party, due to the Turkish state’s long-standing assimilation policies towards the Kurdish minority (Sirkeci Reference Sirkeci2003). This resulted in an increase in the number of asylum seekers during the 1990s. In 2002, following the 2001 economic crisis, the AKP (the Justice and Development Party), with a democratic Islamic identity, took power (Yavuz Reference Yavuz, Byrnes and Katzenstein2006). During its early years in government, during a period of economic stability (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2013), the emigration of Turkish citizens slowed. In the 2010s, however, the number of highly skilled migrants from Turkey to the EU increased as a result of two main factors: the authoritarian policies and practices of the AKP and the loss of economic stability. In particular, highly skilled Turkish citizens emigrated due to increased state interference and authoritarian policies (Sánchez-Montijano et al. Reference Sánchez-Montijano, Kaya and Sökmen2018). Several studies, which used in-depth interviews and online surveys (Elveren Reference Elveren2018; Ozcurumez and Yetkin Aker Reference Ozcurumez and Yetkin Aker2016; Sunata Reference Sunata2010; Yanasmayan Reference Yanasmayan2019), investigated the migration of highly skilled workers from Turkey to developed regions like the countries of the EU, the USA, and Canada in the 2000s and 2010s. They concurred that drivers other than labor market factors, such as social networks, familial consideration, quality-of-life explanations, the social-cultural-political context in the destination country, and demand for better governance and civic society also impact individuals’ migration destination choices. During this period, the war in Syria (started in 2011) and terrorist attacks, such as the Suruç bombing (in 2015), the Istanbul Atatürk Airport attack (in 2016), the 15 July coup attempt (in 2016), and the Reina Nightclub shooting (in 2017), increased instability in Turkey.

Since each organization collects data using different sources and methods, the number of Turkish migrants in Europe is a matter of dispute today. For example, UNDESA (2017b) declares that Turkish migrant stock numbered 2,668,172 people in the EU in 2017. On the other hand, Turkey’s Ministry of Labor and Social Protection reported the Turkish migrant population at 4,933,598 in 2015 (including 2,544,141 dual citizens) in 14 EU member states (see Graph 1) (DİYİH 2015).Footnote 3

Up until recently, Turkish people have been able to gain legal residence status in the UK under the Ankara Agreement, signed in 1963. However, this Agreement was never implemented in other European countries due to several economic and political obstacles, including German concerns about increasing numbers of Turkish immigrants, thus, the rights gained remain limited (Cesarz Reference Cesarz2015; Düzenli Halat Reference Düzenli Halat2010; Oğuz Reference Oğuz2012; Yalincak Reference Yalincak2013). From 1973, the UK implemented the Ankara Agreement by offering Turkish nationals one-year work visas (extendable for three more years). Each year, thousands of Turkish citizens applied for a UK visa. For example, in 2017, 2,925 Turkish people applied for the Ankara Agreement visa, but only 1,430 visas were granted. In total, 77,220 visas were granted through the Ankara Agreement between 1997 and 2017 (Migrants’ Rights Network 2018). Since the UK is no longer a member of the EU as of the end of 2020, this Agreement does not apply anymore.

Aside from the demand for workers from European states, Turkey’s insecure labor market has played a crucial role in this migration flow. The lower unemployment rate in many Western European countries compared to Turkey during 2008–2018 (Eurostat 2019a) encouraged Turkish immigrants to remain in Europe even if Europe’s demand for their labor had decreased. Since 2009, however, due to the global economic crisis, many countries with labor force agreements with Turkey have reduced the number of first permits and visas for 12 months or longer for Turkish citizens (Eurostat 2019b). The economic slowdown caused job losses, with immigrants facing the inevitability of returning home (Skeldon Reference Skeldon2010).

To sum up, the most significant drivers for Turkish emigrants choosing a destination in Europe have changed over the decades. In the 1960s, the labor market was the most significant driver, while security-based drivers became equally important in the 1970s before predominating in the 1980s–1990s. Due to Turkey’s economic and political stability in the 2000s, emigration to Europe stagnated.

Data and methods

Data

This article uses panel data blended from the databases of the OECD, Eurostat, and the World Bank. The central hypothesis is that the labor market, which was a key factor during the twentieth century, is no longer the only significant driver for choosing a migration destination in the twenty-first century. This hypothesis is tested with data for four drivers: security-based, labor market, social, and geographic drivers.

The article focuses on documented (i.e. legal) immigrants. The dependent variable is the number of first residence permits issued (i.e. for more than 12 months; the abbreviation is “FirstPermit”) to Turkish nationals (Eurostat 2019b). Since people prefer to immigrate to countries where they can more easily obtain a residence permit, the security-based drivers are effective over the documented immigrants. A person who fears persecution in Turkey can apply for and hold a long-term residence permit in the EU because the line between the concepts “voluntary” and “forced” migration is blurred (De Haas Reference De Haas2021) (see Table 1).

Table 1. First permits issued for Turkish nationals by the member states which signed labor force agreements with TurkeyFootnote 4

Source: Eurostat (2019b).

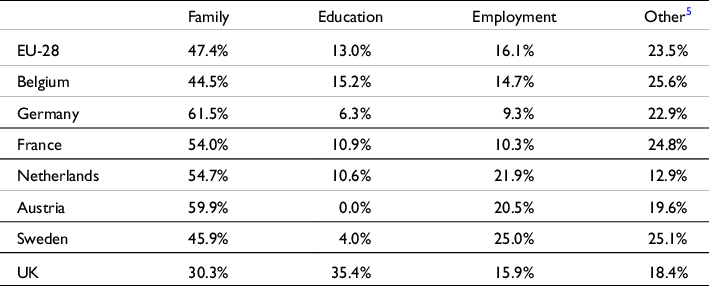

In 2018 almost half of the first residence permits received by Turkish nationals were issued for family reasons, which is a social driver resulting from the connection with migration networks. In contrast, although labor migration used to be an important reason for Turkish nationals entering Europe, only around 16 percent of the permits were issued for labor reasons (Eurostat 2019b) (see Table 2). Other studies (Kirişçi Reference Kirişçi2007; Kulu-Glasgow and Leerkes Reference Kulu-Glasgow and Leerkes2013; Timmerman et al. Reference Timmerman, Lodewyckx and Wets2009) also report that currently many Turkish immigrants continue to move to the EU for family reasons.

Table 2. Reasons for first permits issued for Turkish nationals in 2018 by EU member states that signed a labor force agreement with Turkey

Source: Eurostat (2019b).

The following are the independent variables:

Security-based drivers

-

Freedoms: The democracy index percentile ranks each country compared to others on, among other things, the freedom to elect the government, freedom of expression, freedom of association, and having a free media (World Bank 2019). Since democracy, which is the fundament of human rights (Kirchschlaeger Reference Kirchschlaeger, Grinin, Ilyin and Korotayev2014), includes being free from fear, we use this variable as a security-based driver. This variable controls the possibility of whether Turkish citizens emigrate due to the authoritarian policies in the given period or not.

Labor market drivers

-

Emp: Employment rate (OECD 2018). It is highly correlated to earnings and GDP. Since the prerequisite for earning well is to have a job, we chose the employment rate instead of earnings and GDP.

-

Wage: Compensation of employees (Eurostat 2020). Since the data were in national currencies and some countries are not in the Eurozone, compensation in these countries was converted to Euros according to the currency rate in the December of each year (Trading Economics 2020). Compensation in Euros was then divided into the number of employees (Eurostat 2020).

-

WorkHour: Average usual weekly hours worked on the main job (OECD 2019). Employment itself is not enough since a worker takes account of the quality of employment, including working conditions.

-

LivingCost: Price-level ratio of the PPP conversion factor (GDP) to the market exchange rate (World Bank 2020). It provides a comparison between the USA and another country regarding how many dollars are needed to buy a dollar’s worth of goods (World Bank 2020).

Social drivers

-

TMigSt2005: Immigrant stock level from Turkey in EU member states in 2005 (UNDESA 2017b). These data represent the migration stock related to Turkey, which refers to all native-born persons, whether citizens or foreigners, who emigrated to Turkey and returned from Turkey thereafter, and all Turkey-born persons, including citizens born in Turkey who immigrated. Even if a number of these people are not ethnically Turkish, these data represent the network between an EU country and Turkey.

-

ExOttoman: Dummy variable represents whether an EU member state was a part of the Ottoman Empire in any time of its history. It shows the cultural/historical link between Turkey and that country. The values are 1 for the ex-Ottoman countries (Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Hungary, Greece, and Romania) and 0 for the other EU countries. Many people of Turkish origin in the Balkans lack Turkish nationality. The Turkish/Muslim population in the Balkans is estimated at 1.3 million (55,000 in Romania, 200,000 in Greece, and 750,000 in Bulgaria) (Cole Reference Cole2011). The Ottoman legacy and kinship construct a migration network. Besides, this variable is both a social and geographic determinant because it refers to the geographical proximity to Turkey of the destination country. The ex-Ottoman countries are closer to Turkey than other EU countries like Germany, Spain, France, Portugal, and the UK.

Geographical driversFootnote 6

-

ColdDays Footnote 7 : Heating degree days (number of cold days) (Eurostat 2019c; General Directorate of Meteorology of Turkey 2020). This variable represents a measure of how cold the temperature was during a year for a country. Countries with lower heating degree days have more moderate climates. Following the literature, this article hypothesizes that this variable might explain why Turkish migration stock has been increasing in the Mediterranean-European countries in recent years.

Methodology

The panel data included 11 years (from 2008 to 2018) and 28 EU countries (including the UK), yielding 308 observations. After transforming the model into log-log form, all the independent variables for Turkey (EmpT, WageT, WorkHourT, LivingCostT, FreedomsT, and ColdDaysT) were subtracted from all the independent variables for the member states (EmpMS, WageMS, WorkHourMS, LivingCostMS, FreedomsMS, and ColdDaysMS). Since using data at the macro level does not allow the development of a more complex approach to the interaction of macro and micro levels, we assume that the differences between the home country and destination are highly correlated with migration motivation (Dudu Reference Dudu2018; Sirkeci Reference Sirkeci and Uğuzman2018). For example, if the difference in employment rates between the two countries is high, the probability of migrating for employment reasons to the country with a high employment rate from the country with a low employment rate is likely to be high. Thus, while the dependent variable remained the same, new independent variables were created considering these differences:

The estimation was made using the ordinary least square (OLS) model. The following model was used for the estimation:

\begin{align}{\rm{ln}}\left( {{\rm{FirstPermit}}{_{ijt}}} \right) &= {{{\rm{\beta}} _0}} + {{\rm{\beta}} _1}{\rm{ln}}\left( {{\rm{EmpDif}}{_{jt}}} \right) + {{\rm{\beta}} _2}{\rm{ln}}\left( {{\rm{WageDif}}{_{jt}}} \right) + {{\rm{\beta}} _3}{\rm{ln}}\left( {{\rm{WorkHourDif}}{_{jt}}} \right)\\

&\quad + {{\rm{\beta}} _4}{\rm{ln}}\left( {\rm{LivingCostDif}}{_{jt}} \right) + {{\rm{\beta}} _5}\left( {{\rm{FreedomsDif}}{_{jt}}} \right)\\

&\quad + {{\rm{\beta}} _6}{\rm{ln}}\left( {{\rm{ColdDaysDif}}{_{jt}}} \right) + {{\rm{\beta}} _7}\left( {{\rm{ExOttoman}}{_{ij}}} \right)+ {{\rm{\beta}} _8}{\rm{ln}}\left( {{\rm{TMigSt2005}}{_{ij}}} \right)\\

&\quad + {{\rm{\varepsilon}} _{ijt}}\end{align}

\begin{align}{\rm{ln}}\left( {{\rm{FirstPermit}}{_{ijt}}} \right) &= {{{\rm{\beta}} _0}} + {{\rm{\beta}} _1}{\rm{ln}}\left( {{\rm{EmpDif}}{_{jt}}} \right) + {{\rm{\beta}} _2}{\rm{ln}}\left( {{\rm{WageDif}}{_{jt}}} \right) + {{\rm{\beta}} _3}{\rm{ln}}\left( {{\rm{WorkHourDif}}{_{jt}}} \right)\\

&\quad + {{\rm{\beta}} _4}{\rm{ln}}\left( {\rm{LivingCostDif}}{_{jt}} \right) + {{\rm{\beta}} _5}\left( {{\rm{FreedomsDif}}{_{jt}}} \right)\\

&\quad + {{\rm{\beta}} _6}{\rm{ln}}\left( {{\rm{ColdDaysDif}}{_{jt}}} \right) + {{\rm{\beta}} _7}\left( {{\rm{ExOttoman}}{_{ij}}} \right)+ {{\rm{\beta}} _8}{\rm{ln}}\left( {{\rm{TMigSt2005}}{_{ij}}} \right)\\

&\quad + {{\rm{\varepsilon}} _{ijt}}\end{align}

A high employment rate indicates a high probability of finding employment (Ortega and Peri Reference Ortega and Peri2009). Similarly, higher wages (European Commission 2006) attract immigrants, so here the expected relationship is also positive. Better working conditions in a country, like more leisure time, is a positive motive (De Jong and Fawcett Reference De Jong, Fawcett, De Jong and Gardner1981). Accordingly, countries with lower-than-average normal weekly hours in the main job are more attractive, so a positive relationship is expected. On the other hand, a higher cost of living (Berger and Blomquist Reference Berger and Blomquist1992; Cedefop 1998) is negatively related to applying for a work permit.

The perception that Europe supports democracy and human rights increases the probability of migrating there (Timmerman et al. Reference Timmerman, Verschragen, Hemmerechts, Timmerman, Clycq, Levrau, Van Praag and Vanheule2018). Likewise, since Turkey has greater cultural/historical proximity with countries ruled by the Ottoman Empire and Turkish nationals still have relatives in these countries, a positive relationship is expected. Conversely, since a moderate climate increases immigration, a negative relationship is expected.

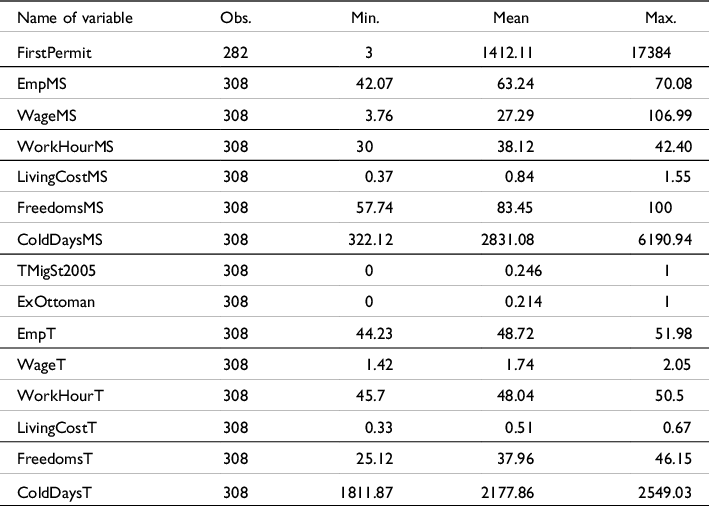

The descriptive statistics show a wide range of residence permits issued yearly for Turkish people by each member state. For example, one country issued only three long-term residence permits per year whereas another issued more than 17,000 (see Table 3). The total number of residence permits issued follows a similar trend to the number of residence permits issued for Turkish nationals from the countries with labor force agreements with Turkey (see Graph 2).

Graph 2. Number of first permits issued for Turkish nationals from EU member states.

Source: Eurostat (2019b).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics

Turkey’s employment rate, wages, working hours, and democracy level are lower than those in EU member states, whereas its climate is more moderate. Turkey’s employment rate has gradually increased since 2008, reaching a peak of 51.98 percent in 2018 (OECD 2018), although this was still lower than the EU-28 average. Wages are also lower in Turkey. Average weekly working hours range from 30 to 42 hours in the EU, while they had decreased from 51.7 to 47 hours in Turkey by 2018 (OECD 2019). Turkey’s democracy level, which was already lower than any EU country, has fallen sharply from 46.15 to 25.12 since 2008 (World Bank 2019). When comparing the average heating degree days with countries in the EU, like Greece, southern Italy, and Spain, Turkey has a moderate Mediterranean climate (Spinoni et al. Reference Spinoni, Vogt, Barbosa, Dosio, McCormick, Bigano and Füssel2017) (see Table 3).

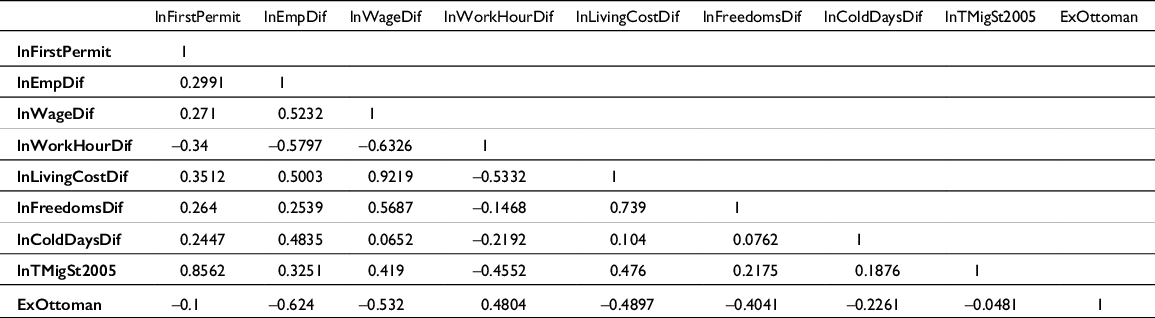

Table 4 shows us that some variables are highly correlated. For example, FirstPermit and TMigSt2005 are highly positively correlated at 0.85. Signing a labor force agreement with Turkey significantly strengthens the migration network between two countries, encouraging a significant number of Turkish citizens to live in these member states. Another high correlation is between lnWageDif and lnLivingCost at 0.92. The reason for this high correlation is that people can adopt different product search strategies to buy a similar product with a different brandmark (Committee on Finance US Senate 1995) thus paying less when they cannot afford that product anymore.

Table 4. Correlations

Empirical findings and discussion

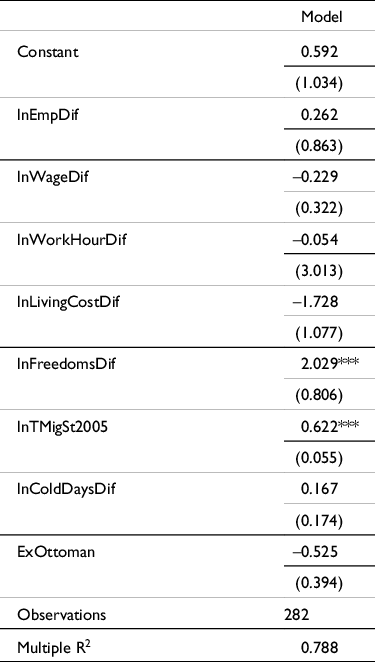

The independent variables (EmpDif, WageDif, WorkHourDif, TMigSt2005, FreedomsDif, ColdDaysDif, and ExOttoman) explain 78.8 percent of the variance—R2 is 0.788—in the dependent variable, FirstPermit. The estimation shows that FreedomsDif and TMigSt2005 are positively and highly significant in determining FirstPermit, and the density of migration networks and differences in freedoms between Turkey and the EU-28 are significant drivers for Turkish migrants’ EU destinations.

FreedomsDif is significant in determining FirstPermit. The estimation shows that a 1 percent rise in the freedom difference between Turkey and the EU-28 increases the number of first permits issued for Turkish nationals by 2.02 percent (see Table 5). This article focused on 2008–2018, when Turkey’s democracy level deteriorated sharply from 46.15 to 25.12 (World Bank 2019) and demand for greater democracy increased. Turkey ranked lower than any EU country: 110th among 167 countries in 2019 (The Economist 2020). This finding suggests that increasing state interventions and authoritarian policies have motivated more Turkish people to emigrate (Sánchez-Montijano et al. Reference Sánchez-Montijano, Kaya and Sökmen2018) as suggested by the EUMAGINE project (Timmerman et al. Reference Timmerman, Verschragen, Hemmerechts, Timmerman, Clycq, Levrau, Van Praag and Vanheule2018). Although the level of democracy in Turkey has decreased consistently each year between 2005 to 2018, people in Turkey have repeatedly elected AKP governments since 2002 (as of 2020) (World Bank 2019). The war in Syria and terrorist attacks in the 2010s also damaged democracy in Turkey. Accordingly, many young people in Turkey think that there is a democratic deficit (SODEV 2020).

Table 5. Coefficients of the estimation (OLS)

Note: Standard errors adjusted for 28 clusters in the country. Robust standard errors in brackets; significance denoted by ‘***’ at 1%, ‘**’ at 5%, and ‘*’ at 10%.

TMigSt2005, the number of Turkish people in EU countries in 2005 just before the period covered in this article, significantly influenced Turkish nationals’ migration destinations. It represents the power of migration networks because a larger Turkish population in a member state means having a more powerful migration network to provide support to newcomers. Like other studies (Dedeoğlu and Genç Reference Dedeoğlu and Deniz Genç2017), the findings show that migration networks make that country a more likely migration destination. The estimation indicates that a 1 percent rise in Turkish migration stock in a member state in 2005 increases the number of first permits issued for Turkish citizens by 0.62 percent (see Table 5).

The findings of this study using macro data—the influence of social networks and demand for democracy on the Turkish nationals’ migration destinations—support the findings of other studies (Elveren Reference Elveren2018; Ozcurumez and Yetkin Aker Reference Ozcurumez and Yetkin Aker2016; Sunata Reference Sunata2010; Yanasmayan Reference Yanasmayan2019) which benefited from in-depth interviews and survey. This study filled a gap in the literature by focusing on the drivers of migration destinations of Turkish newcomers in the EU by using macro data.

Conclusion

The drivers of Turkish newcomers’ migration destinations to the EU-28 in the twenty-first century are different from those in the twentieth century. Until the 1990s, Turkish immigrants were motivated by political and economic factors. Although Turkish citizens’ emigration to the EU slowed due to Turkey’s economic stability in the first years of the twenty-first century, it stepped up again towards the second decade. This article confirms that a country’s migration network and freedom level were significant drivers of Turkish migrants’ EU destinations between 2008 and 2018.

This study’s novel significance is its exclusive focus on Turkish newcomers to the EU. The article drew on data collated from OECD, Eurostat, and World Bank databases. The regression analysis produces two main findings: the size of an EU country’s Turkish migration stock significantly increases the number of Turkish immigrants receiving a long-term residence permit because of familial ties, and the greater the difference in freedom levels (in the meaning of being free from fear as a security-based driver) between an EU country and Turkey, the larger the number of Turkish immigrants. Thus, the analysis confirms that the sharp decrease in Turkey’s democracy level due to state interventions and authoritarian policies is a significant driver of destination choice. This is such that the effect of a possible rise in the difference between the freedom levels of Turkey and the EU-28 is greater than the effect of the possible rise in Turkish migration stock in Europe.

Security-based (democracy level) and social (migration networks) drivers have become highly relevant in the twenty-first century because the profile of Turkish immigrants has changed. Unlike in the 1960s, labor market drivers are no longer the strongest motives. Thus, this article presents the drivers of migration destinations of Turkish newcomers in the EU in the twenty-first century at the macro level. For further studies, we will consider examining the link between highly skilled newcomers and the demand for more democracy, which contributes significantly to brain drain studies, and the migration networks from the perspective of identity studies.

Acknowledgements

We thank Adem Yavuz Elveren, Bryan Stuart, and Ünal Töngür for their valuable comments.

Conflicts of interest

None.