Introduction

Since the war began in Syria in 2011 there has been an unprecedented number of refugees coming to Turkey.Footnote 1 Initially, the Turkish state handled the matter without receiving humanitarian aid; however, as the refugee arrival continued, humanitarian assistance to Turkey from external resources progressively increased. This led to significant changes in the structure of the Turkish state in terms of migration management, starting from passing the Law on Foreigners and International Protection and establishing a Directorate General of Migration Management (Göç İdaresi Genel Müdürlüğü, DGMM)Footnote 2 to changes in the existing welfare system.Footnote 3 There have been studies regarding the relationship between civil society organizations (CSOs) and the state,Footnote 4 yet few have empirically examined the way in which the relationship between state and civil society has been shaped in the context of migration and evolved as the state takes greater control of humanitarian assistance in response to the presence of refugees.Footnote 5 CSOs, as referred to in this paper, range from local community-based organizations to professionalized international CSOs. This paper raises the following broader questions: How does mass migration (of Syrians) shape the (Turkish) state into a receiving country from being a predominantly migrant-sending country? What do we learn about state–civil society relations from a broader sociological point of view as the two interact on the issue of Syrian migrants in the Turkish national context? Further, to what extent does this changing relationship between state and civil society have an impact on the way in which services are provided to Syrians in Turkey?

This study, taking the field of adult language education as a case study, looks at the transformations and evolution of this relationship and the power dynamics between different actors and their margin of maneuver to show how the state manages to dominate the language-provision scene, even as it, at the same time, abdicates its responsibility to ensure long-term integration through language education.

Unprecedented in its scale, the need for service provision for refugees has rapidly represented a challenge for the financial capabilities of the Turkish state, even as it received the support of international humanitarian organizations or local civil society. In 2016, the EU–Turkey deal on the management of migration deeply modified the attitude of the government toward CSOs. The “laissez-faire” politics that were adopted until then transformed into control politics with the goal of capturing European funds, mainly destined for implementers of humanitarian projects. These efforts also aimed at silencing potential dissent and criticism in this field as they also aimed to control academic and research activities about Syrians in Turkey and revoke the registration of several organizations working with Syrians, sometimes cross-border. While maintaining a logic of control over CSOs and funding, it continued to respect the procedures for managing aid in terms of implementation and accountability standards set by international donors. In this way, the state maintained its power over the EU and CSOs, gathered funds for itself and its loyalists, and managed to avoid changes to the system in view of the longer-term integration of migrants.

The field of language instruction constitutes an interesting case study for two main reasons. First, unlike other fields such as healthcare and social assistance, in which there was already an existing social welfare system and domestic social policies,Footnote 6 the need to provide Turkish language education to a large number of individuals has newly emerged and does not fall under the responsibility of any existing system or institution. With such a large arrival of non-Turkish-speaking refugees, a significant need was created for Turkish language instruction. This has led to increased levels of humanitarian assistance to Turkey from external resources and the subsequent development of state institutions to accommodate it. Second, in the field of education among others, humanitarian assistance has recently undergone increased state control as part of the efforts of the state to increase pressure on civil society following the failed coup attempt in 2016, in continuity with an already tense relationship between international organizations and the government,Footnote 7 especially since the Gezi Park protests in 2013.Footnote 8 In order to analyze the changes in this field, I focus solely on state and non-state actors who are directly involved in the provision of language education for adults.

In the following sections, I first outline the literature that analyzes the relationship between the state and civil society highlighting the dichotomy in which the state is portrayed as either playing a dominant role or whereby civil society takes over control depending on the national context. Second, after presenting the method and data used for this paper, I provide background information on the arrival of the largest flow of non-Turkish-speaking refugees from Syria, followed by the current landscape of language education initiatives for Syrian refugees in Turkey. Then, I demonstrate how humanitarian assistance for adult language education has been subjected to increased state control and centralization. Thus, the autonomy of expansion of state bureaucracy has contributed to reshaping the field by creating a hierarchy between organizations. It has also led to channeling humanitarian assistance toward large projects that can align their strategies with state institutions through “partnerships” at the expense of smaller initiatives. This was not only a result of the lack of trust between state and civil society but also an attempt at channeling EU funds to handle an unprecedented number of refugees through state institutions, while complying with the funders’ conditions. All the while, this relationship allowed the state to avoid having to make long-term integration policies and avoid facing growing tensions among the public. Indeed, in light of the domestic politics in the country, whereby opponents of the current party in power hold it responsible for the long-term presence of Syrians, public perceptions of Syrians as competing for the same resources predominate, and as the economic crisis looms there have been rising social tensions and clashes in neighborhoods.

Relations between humanitarian assistance and the state

The question about the relationship between state and civil society is a much-debated one. Typically, the role of the state in countries in the “Global North” is portrayed in the literature as dominant in policy making, and CSOs as merely acting as service providers as part of the social policy network.Footnote 9 Generally, the term “migration state” refers to advanced industrial countries with high levels of state capacity and sovereignty. These states are treated by researchers as rational actors with functioning policy making and bureaucratic apparatuses. In contrast, in countries that are receivers of humanitarian assistance, in the “Global South,” it is the CSOs and donor states that are portrayed as taking a more dominant role. In times of mass migration especially, the responsibilities are blurred and non-state initiatives act as pseudo-nation-states due to limited funding and resources.Footnote 10 Such states are described as having low levels of state capacity or compromised sovereignty and thus a poorer ability to formulate and implement coherent and effective migration policies.Footnote 11 Departing from this approach, this paper seeks to challenge this Global North–Global South dichotomy in the relationship between the state and CSOs. Instead, it aims to capture the complex relationship between these two actors and the mechanisms through which the dynamics of this relationship evolve in Turkey, a country which is at the front line of refugee service provision.

The literature shows that the extending role of non-state actors, in such states that provide services for a great number of refugees, is due to the absence of adequate resources and institutional capacity,Footnote 12 leading to increased reliance and a new form of dependency on civil society actors. As a result, such host states, fearing weakened sovereignty or the emergence of oppositional movements, may assert control over CSOs.Footnote 13 These practices of state control on CSOs serve to recognize and reinforce the social separation between the state and international organizations, thereby giving the image of “an integrated, autonomous entity that controls, in a given territory, all rule making, either directly through its own agencies or indirectly by sanctioning other authorized organizations.”Footnote 14 Further, government officials seeking to maintain power and legitimacy take actions to meet the “crisis” by establishing new institutional forms.Footnote 15 A growing state apparatus and control over CSOs, however, do not necessarily equate to state dominance.Footnote 16 Instead, a variety of different configurations of power relations may emerge as a result. Governments may target CSOs by enacting legislation that prohibits foreign funding for them.Footnote 17 Civil society often operates as an instrument to extend state social control over its citizens in the example of Jordan.Footnote 18 In Turkey, while CSOs do challenge the state in some regard, the state is by far the more powerful actor and very effective at moderating and deradicalizing civil society.Footnote 19 Civil society in Turkey had reached a peak following the 1999 Izmit earthquake which prompted humanitarian response in an authoritarian contextFootnote 20 and constituted a window for activating civic participation.Footnote 21 This instance set a precedent for the cooperation between the state and civil society. Yet, CSOs faced difficulties after the Gezi Park protests in 2013,Footnote 22 and since the coup attempt in July 2016 about 1,500 CSOs have been closed.Footnote 23 The presence of Syrian refugees in Turkey is believed to demonstrate that strong governments may also be substituted by non-state actors.Footnote 24 While Turkey is itself in the highest league of humanitarian assistance donors,Footnote 25 facing this humanitarian situation requires financial means on a bigger scale compared to the earlier situations mentioned above, such as the 1999 earthquake. As such, it currently receives humanitarian assistance in the face of refugee arrivals. The curtailing of civil society, coupled with a large financial input for the sector from both domestic and international sources, makes Turkey an interesting case for empirically examining the particular conception of the relationship between the state and civil society actors in service provision to refugees. This paper contributes to this conception by showing that the Turkish state is wary of the risks of strong CSOs faced in other countries in the Global South and acts to control them, while still allowing them to provide funding and expertise through particular mechanisms. In addition, this case investigates the expansion of state bureaucracy and its autonomyFootnote 26 in the context of a dependent capitalist country, in exercising influence to define and interpret the “general interest” of the country.

Methods and data

This qualitative study was conducted between September 2018 and June 2019. I conducted desk research to analyze the literature focusing on language instruction and the historical flow of forced migrants in the case of Turkey. In order to capture and understand the relationship between the state and civil society, expert interviews were carried out with thirteen state officials (in Turkish) including representatives from the lifelong learning departments of the Ministry of National Education (Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı, MoNE) and the municipality, Public Education Centers (Halk Eğitim Merkezleri, PECs) and Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities (Yurtdışı Türkler ve Akraba Topluluklar Başkanlığı, YTB) in Ankara. In addition, twenty interviews were carried out in Turkish and English with representatives from CSOs of varying types and sizes in Istanbul (international and domestic non-governmental organizations; community centers; foreign and local; faith-based and not), Some having signed the protocol with MoNE in order to be able to offer any educational activities to Syrian refugees, including teaching Turkish as a foreign language, others not. The representatives include administrators, teachers, and coordinators. Most of these organizations were based in socio-economically and demographically diverse districts in Istanbul (e.g., Fatih, Sultanbeyli, Kücükçekmece, Sultangazi, Şişli, and Beyoğlu) in which there is a dense population of Syrians. The interviews started with questions about the organization: its funding, role, and structure. These were followed by questions about the perceived importance of teaching Turkish to incoming migrants, the level of instruction provided, Turkish language class content, and the existing policies in terms of teaching Turkish to incoming refugees. The interviews also focused on the relationship between CSOs and the state, including questions about the protocol process and changes that occurred. The interviews with a diversity of actors allowed me to capture the variety of relationships among different types of actors, namely the way in which state institutions have evolved over time in this particular field, focusing on the protocol process as well as the way in which administrators in these institutions are implementing internationally funded programs. The interviews with CSO representatives in different organizations explore how the CSOs are responding to these changes and how their relationship with the state has developed. The audio-recorded interviews (when permitted) were transcribed. The analysis of interview materials was shaped through a grounded theory coding approach. I attributed initial codes, based on lines, segments, and incidents, then engaged in focused coding by selecting what seemed to be the most useful initial codes, when tested against data.Footnote 27 The data coding and analysis were carried out using the Atlas.ti software.

Evolution of migration management in light of the Syrian refugee presence

As of June 2020, there were around four million Syrian refugees in Turkey.Footnote 28 A variety of factors have come together and led to a partnership approach between the state and civil society. First, the Turkish state was unprepared for the arrival of such a large number of refugees and had to scramble to make laws and procedures to regulate reception and protection. In 2012, the Temporary Protection status was officially implemented for Syrian refugees. The following year, in 2013, the Law on Foreigners and International Protection was ratified, in which the rights and obligations of persons under temporary protection was regulated.Footnote 29 Under this law, state institutions also evolved in terms of migration management, as it called for the establishment of the DGMM under the Ministry of Interior (İçişleri Bakanlığı). Second, as the stay of refugees became protracted Turkey had to develop strategies to cope, so CSOs became active where the state was slow to react. In the first year of reception, the Turkish state did not ask for humanitarian aid from the international community and instead sought to manage Syrians’ needs on its own.Footnote 30 However, as of late 2012 it started to appeal to the international community for support, all the while continuously emphasizing the cost incurred to shelter the refugees, especially on international platforms. With increasing numbers of Syrians residing out of the camps, state institutions, especially MoNE, started to cooperate with CSOs to address the needs of refugees. Discourse in Turkey progressively evolved toward “harmonization” (or uyum in Turkish, purposefully avoiding the word “integration”).Footnote 31 Originally, integration and language courses were foreseen as requirements for Turkey’s foreigners, but these were removed from the final version of the law.Footnote 32 Since the Turkey–EU deal in 2016, the EU has disbursed six billion euros in funding for humanitarian assistance activities to support refugee hosting.Footnote 33 Further, although Turkey offered citizenship status to some refugees it considered to be “skilled,” state discourse did not imply long-term permanent integration for all. Mostly EU-funded initiatives were introduced throughout the country to provide or facilitate refugees’ access to education, employment, and healthcare services, among others.

Third, the internal political dynamics following the coup attempt in Turkey influenced migration governance as it increased mistrust toward CSOs. The relationship between the state and civil society could already had been described as mutually suspicious, especially in the context of the Gezi Park protests. The presence of Syrians was accompanied by significant amounts of humanitarian assistance and an increase in the number of CSOs. During the state of emergency, declared just after the 2016 coup attempt, the state moved toward further control of CSOs and the shutdown of many international CSOs. While a variety of CSOs had initially been offering language instruction as part of an ad hoc emergency response, the state required organizations to sign a protocol with MoNE in order to offer any educational activities to Syrian refugees, including language education courses, according to a circular issued in 2017 as part of the crackdown. CSOs continue to be perceived as temporary or unofficial partners (as material suppliers) while the ministry retains its supervisory role. Furthermore, the “politically and ideologically fragmented structure of the civil society” is reported to allow the Turkish state to “play favorites.”Footnote 34 Researchers show that the state chooses to selectively cooperate with loyal CSOs, considered as reliable partners, aligned to the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi) growing neoconservative agenda,Footnote 35 while organizations with clear secular agendas are left out.

Lastly, the EU–Turkey deal gave more power to Turkey to manage foreign influences. Indeed, the deal was subject to political bargaining and joint accusations breeding substantive mistrust on both sides.Footnote 36 As such, although Turkey, which hosted a considerable number of refugees, faces similar challenges to those faced by EU countries, the deal was not accompanied with collaboration in planning a longer-term vision. Instead the deal, which included a plan to manage irregular migration from Turkey and substantial funding (three billion euros in 2016–17 and another three billion euros in 2018–19) to support Turkey in hosting refugees,Footnote 37 gave the Turkish state more negotiating power. These types of agreements between countries in the Global South and the EU are not new and often result in patron–client relationships based on the threat of migrant numbers, rather than on common goals.Footnote 38

Language education as a response to the arrival of refugees

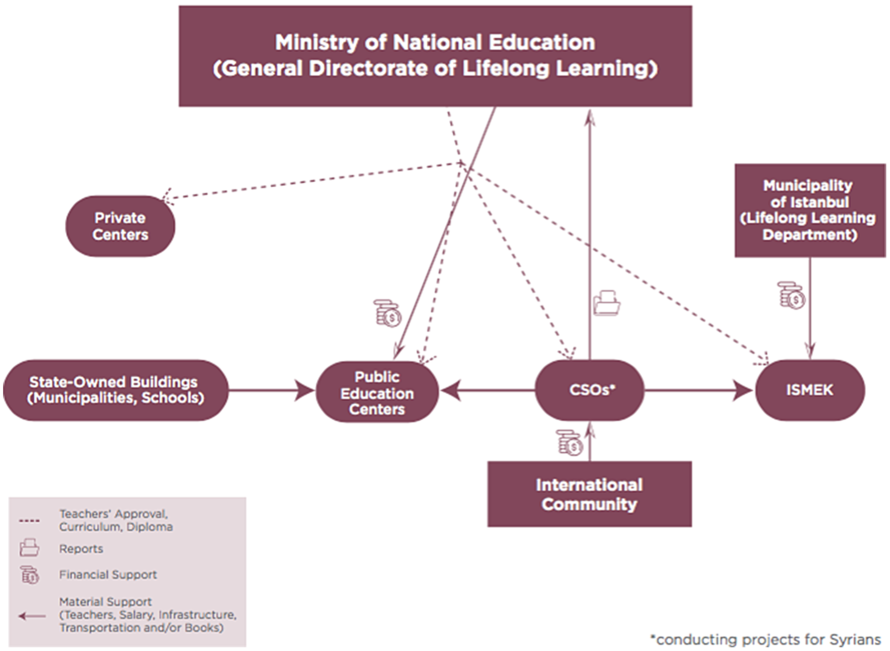

A variety of private centers emerged to offer instruction at different costs and of variable quality, mainly accessible for Syrians with sufficient economic resources. However, language-learning opportunities have been provided free of charge to adult Syrians in Turkey under the umbrella of MoNE’s Lifelong Learning Department and Istanbul Municipality (see Figure 1). PECs, currently under MoNE’s Lifelong Learning Department, were founded at the start of the Republic as a national initiative to teach reading and writing and Republican values. With the increasing neoliberalization of Turkish cities, these centers started focusing on skill formation for the job market. In addition, municipalities founded centers to deliver vocational courses in 1996. The largest of these, the Istanbul Art and Vocation Training Courses (ISMEK), is funded by the Municipality of Istanbul. As Syrians’ stay became perceived as long term, both of these centers, which have a flexible mandate of work, started to offer Turkish for foreigners. Despite their growth in recent years, these options present limited capacity and rarely meet demand. In PECs, a total of 192,625 students registered for Turkish classes between 2014 and 2018, and in ISMEK, a total of 9,326 Syrian adults attended language courses between 2013 and 2019.

Figure 1: Institutional map of language education landscape in Istanbul

The proportion of Syrian adults that are reached by these initiatives is thus very low. Several stakeholders commented on this situation:

We had [started] registration on the third of July. During those days our systems usually collapse. (Head of a language center run by the municipality)

It is impossible to match the population there [in Zeytinburnu]. The population is so large that all of us coming together to open however many courses would not be enough. (Project coordinator, medium-sized local CSO founded in 1993, operating in twelve centers across Istanbul, and working with protocols with municipalities and MoNE)

Resources are often limited and waiting times between courses are long. In all of the above-mentioned state-run centers, the number of courses, teachers, and classrooms is inadequate. CSOs have tried to respond to the above-mentioned limitations by increasing the number of humanitarian assistance programs for language education.

Increasing state control over CSOs in the field of language education

I will demonstrate that the state, which needs financial support to manage the presence of refugees, develops mechanisms whereby it creates institutions to take over control of CSOs while continuing to comply with the regulations of funders to continue to receive international funds. As the EU releases funding for humanitarian assistance activities via the agreement between Turkey and the EU, a portion of these sums of money, along with other funding, has been progressively channeled into initiatives that aim to address the limitations related to language instruction for adults through governmental institutions, as the state must align with the priorities of the funders, such as “putting refugees to work”Footnote 39 or facilitating their entry to the formal job market, through professional training and language education among others. The funds for these projects have been progressively channeled through state institutions. This situation has led to the creation of new departments which are in charge of its implementation. For instance, in 2016 a new department was founded within MoNE’s Migration and Emergency Situation Education Department (Göç ve Acil Durum Eğitim Daire). Its goal is to “develop, implement, follow-up and evaluate policies related to education in migration and emergency situations” based on an interview with a state representative from this department. While the state exerts pressure on the international CSOs to take over the assistance activities of Syrians, it must strictly submit to the procedures for obtaining funds, with the creation of departments that are specialized in the management of funds and personnel trained in this field within each state institution.

While CSOs initially offered language education in an ad hoc manner to small groups of students, they have progressively come under the control of the government in recent years. After the 2016 coup attempt, and in an atmosphere of increased suspicion, the state took over control of the previous humanitarian-led adult education programs, yet ensured a continuing partnership between the government and some of these CSOs (mostly partners of EU organizations), requiring them to sign a protocol with MoNE. The state’s goal is thus to restrict and control civil society and its actions while continuing to benefit from the funds and from collaboration with organizations. These types of protocols were already in place before 2017 between MoNE and various organizations. The procedure for these protocols has now been specifically adapted to CSOs. According to an official in the Lifelong Learning Department of MoNE, in December 2018 there were 114 active protocols. Of these, forty-one projects cater to individuals under Temporary Protection.Footnote 40 Signing a protocol with CSOs involves a long process. First, the CSOs submit a proposal, which is reviewed then modified or accepted by governmental institutions. The organization must lay out the goal of the proposed project, its target group (gender, age), and its budget amount. The organization proposes an operational system shared between the organization and the government. The application is then sent electronically to the department of the Ministry of Interior Affairs that looks over relations with civil society and enquires about the CSO. For international CSOs, the department of legal services examines the project’s legal status. Finally, the application comes back to the Lifelong Learning Department’s protocol unit to be examined by the head of the unit, general director, and vice director. After alterations are made, all parties then sign this protocol. While protocols with governmental institutions last three years, those with CSOs last one year and have to be renewed. When proposals are approved there is a rigorous reporting mechanism. Each CSO is required to write a report every month and submit it to the PEC, and every month the PEC sends the report to the district office of MoNE (İlçe Milli Eğitim). Every three months, the district office of MoNE sends a report to the Provincial Ministry of Education (İl Milli Eğitim). Every six months, the Provincial Ministry of Education sends the report to the Lifelong Learning Department (Hayat Boyu Öğrenme) at MoNE, while simultaneously CSOs send a report to the Lifelong Learning Department at MoNE. These two reports must match.

This reveals a particular mode of interaction between humanitarian assistance programs and state institutions. The interviewed state actors believe that the increased control over and standardization of services delivered by CSOs is necessary to reduce fund loss, improve structure and capacity, and standardize the quality of services. This sentiment is reflected in the following quotes by representatives within MoNE:

As someone who was involved in that process, I can say that CSOs were acting by themselves. They gave unqualified education without a certificate and this resulted in loss of funds. It is not good. (Public Relations, Lifelong Learning Department, MoNE)

It was uncontrollable; who gives what education in which area was unknown. Whoever gathered three people, said I will give language education. This is not right. Education has standards. Those standards should be met. And these standards can only be met by institutions who can give certificates. (Project expert, Lifelong Learning Department, MoNE)

This reflects the perceived need for greater control over education providers. A state official describes the level of knowledge that the state currently has with this protocol system as follows:

This way, now I can tell you for example on Monday afternoon this organization is offering this course level, A2 for example to these students from this time to this time. (Protocol Unit, Lifelong Learning Department, MoNE)

Overall, the increased state intervention and centralization of Turkish language instruction for Syrians in principle could be favorable as it reduces duplication of efforts and the waste of resources and increases efficiency. It also allows the ministry to set conditions tied to funding, namely requiring that all courses be “free of charge” to students. Yet, it reduces CSOs to taking a support role in terms of material needs. A stakeholder in the Lifelong Learning Department of MoNE reiterated that CSOs should support the existing structure.

Instead of directly teaching Turkish, international organizations should provide infrastructure support for existing institutions, which would be more productive. There are institutions teaching Turkish. There’s no need to open a new type of course … At this point, classrooms should be well equipped, including digital equipment. We have enough education material; there will be a need for publishing and distributing books. (Public Relations, Lifelong Learning Department, MoNE)

The state’s increased control has reshaped the relationship between the state and CSOs, relegated CSOs to support roles, and changed the way in which humanitarian assistance is provided when compared to the earlier period. In addition, it was accompanied by an extension of state bureaucracy to maintain control over incoming funds. These steps have aimed for the state to maintain its legitimacy within the arena of power negotiation with civil society in the eyes of its citizens and the international community.

“Selective permeability” of organizations based on loyalty to the state

By requiring that CSOs sign a protocol the state has created a hierarchy between organizations whereby it is “selectively permeable”Footnote 41 to organizations based on the degree to which they are loyal to the state. Similarly to Oszlak,Footnote 42 I show that the activity of bureaucracy does not take place in a vacuum; it is directly and dynamically connected to the needs of “civil” and “state” actors, who seek alliances and accept or neutralize the challenges of actors with opposing interests. The protocol decision-making process, as outlined above, is often perceived as opaque by the organizations themselves. At the beginning there was a lot of confusion about how to apply, and CSOs working with Syrian refugees asked each other for support in the process. Several CSOs described the process as long and difficult. Once this process became required, most stopped their ad hoc classes for several years until they figured out the process and adapted to it. One of the CSO representatives expressed it as follows:

Turkish classes were offered since the opening of the community center in 2015, but it was interrupted, there were no classes offered after the protocol was required, until this year, when we obtained a protocol with a public education center. (Project Officer, large-scale Turkish CSO in Istanbul operating in nine cities, founded in 2005, working with a protocol from MoNE)

This came up in many interviews with these types of local organizations. However, organizations close to the government (or created by the government) are aligned with its mission and as such do not face as much difficulty with the process. These organizations, which function in subordination to the state, are favored through a patron–client relationship given the larger resources involved. There are particular types of organizations created by municipalities as a response to the refugee presence in order to be able to receive funding. In these cases, the process of getting the protocol is facilitated through their affiliation with the municipality as reported by one of these CSOs:

Interviewer: There were changes in the regulation of language instruction, how did that affect you?

Respondent: This was part of our main problem at the beginning, but we were the second organization who got the protocol from the Ministry of Education. Especially in that kind of protocol, governmental issues, the municipality is really important for us. Because it is a public institution. (External relations officer, medium-sized Turkish CSO established in 2014, affiliated to a local municipality in Istanbul, with international partnerships and protocol with MoNE)

In contrast, in light of an atmosphere of lack of trust between the state and civil society, other organizations (especially the foreign-based ones) expect the process to be difficult. They thus refrain from applying, rather choosing to collaborate with larger local CSOs with a protocol, as they fear being denied permission due to the enquiries involved and the vagueness of the criteria. These organizations mostly already existed before the arrival of Syrian refugees. Some were created as a result of the 1999 earthquake in Turkey, others after the Iraqi refugee arrival in the late 1990s. After the mass Syrian refugee arrival, they moved to working with this group.Footnote 43 They apply to international funds on a project basis and have the capacity to manage them as well as have established relations with the state. For instance, a foreign organization based in the United States had received funding and was thinking of operating in the area of language education but doubted its ability to pass these steps and thus opted for directly funding an organization with a protocol. Several organizations similarly opted out preventatively, because they did not want to risk being refused and then being submitted to stricter controls.

Those who did obtain the protocol remained cautious regarding the information they shared during the interview or in their activities, as they remain under close control. “On the day of the exam the PEC director comes and oversees, meets students, monitors closely,” indicates a project officer within a local large-scale CSO, founded in 1995, based in Ankara, and operating across fifty cities, with a protocol such as the ones mentioned above. These connections and permits are thus volatile and need to be renewed on a yearly basis. Even more established CSOs considered to be aligned with the state can sometimes fall out of favor.

Channeling humanitarian assistance toward large projects through state bureaucracy

Humanitarian assistance was progressively channeled toward large projects by international CSOs. For instance, UNHCR implemented a thirty-month project to “strengthen the institutional capacity of eight PECs” to make available more Turkish language learning courses and vocational training. The project aims to reach 8,000 beneficiaries and has a budget of ten million euros.Footnote 44 Similarly, UNDP is leading a project in which they are developing a “blended learning approach” combining face-to-face with distance learning. This new initiative, funded by the EU, will deliver Turkish language courses to 52,000 adult Syrians living in ten provinces across Turkey. Infrastructural and technical support is also provided to fifty-three PECs. In addition, there has been a significant amount of international funding that was channeled toward university scholarships and language education programs for young adult Syrians who intend to pursue higher education. This funding is run under the YTB public institution, which was established in 2010 and now receives significant amounts of funding from the EU (among others) through UNHCR. YTB runs the scholarships for foreigners wishing to study in Turkey, which had been run by the President’s Office since the 1960s. In 2012, a number of scholarships were transferred to the newly created YTB catering to students coming mostly from the developing world (including Syrians) to study at universities in Turkey.Footnote 45 With the increasing number of Syrians in Turkey, YTB started implementing new programs, mostly funded by the EU, particularly geared toward Syrians that also included one year of language training. The YTB created a department and trained individuals to run these scholarships as well as a new type of scholarship program, the Advanced Level Turkish Education Program (Ileri Düzey Türkçe Eğitim Programi), which was developed for Syrians in collaboration with UNHCR. It covers the cost of around one year of Turkish language instruction as part of the EU humanitarian assistance funds. In the 2017/18 school year, a total of 3,000 students were selected from among a pool of 8,000–9,000 applications. To ensure increased state control over larger projects, new departments and institutions were created within the YTB to run this program in collaboration with more than twenty university language centers. International organizations usually collaborate with the state in the implementation of these types of large projects: “For instance, UNICEF, UNDP, UNHCR, GIZ have all signed protocols” (Protocol Unit, Lifelong Learning Department, Ministry of Education).

As the system of protocols with the state becomes time-consuming and the projects larger, CSOs also had to expand their capacity in terms of staff and hired individuals to deal with this bureaucracy. Only larger international organizations have the necessary capacity and staff to maintain this relationship, which might involve trips to Ankara. The process usually involves intensive interactions with ministry representatives, and CSOs usually have a contact point within the ministry to facilitate the process, as stated by a representative of a large international organization. In contrast, smaller CSOs, who organize local activities and have small-scale funding, do not have the capacity to apply for these protocols due to lack of staff and budget. Some of them may purposefully not wish to increase their capacity to avoid exposing themselves to the “inflexible demands of the donor industry.”Footnote 46 As such, they sometimes offer support in language education without providing certificates to their participants. As they are not allowed to call these sessions language classes, they refer to them as “workshops,” “study sessions,” or “language café activities.” Others just refer potential students to the nearest PEC. For instance, one small community center in Istanbul, consisting of eight staff members, said that they were too small and decided not to apply. All their staff members were already working hard in three different areas of activities. They would have to hire more staff to take care of such a process. In addition, they lacked information about how to apply. Consequently, smaller local or foreign CSOs in terms of funding and staff only operate in collaboration with larger organizations that already work closely with the state. A similar organization with fifteen staff members stated that they lacked the capacity to apply for the protocol, so they instead applied for a project which funded two consecutive levels of Turkish language courses to be offered by the Turkish and Foreign Languages Research and Application Center of Ankara University (Türkçe ve Yabancı Dil Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi) private center in their facilities. This collaboration allowed centers to offer certificates recognized by universities.

Yet, organizations running large projects tend to be target-oriented and focus solely on reaching the largest possible number of beneficiaries, while the smaller ones, which are better able to meet the specific needs of their beneficiaries, are excluded from operating in this context. One of the stakeholders in a large international CSO proudly showed the number of students they had reached, which was significantly higher than the sum of all other CSOs, as an indicator of their success. Similarly, a representative from another large organization stated: “With this year we have more than 9,000 applications and we are trying to accommodate around 2,000 to 3,000 students each year.” As a result, in order to facilitate selection they end up setting selection criteria, such as cutting the age limit and systematically excluding students who had to interrupt their studies due to their displacement. Success is measured in terms of attendance and completion rates. In contrast, smaller organizations aim to tailor their activities based on the needs of their community. A representatative of a community center explained that he regularly sends out online links asking their community members to request activities, give their opinions of past activities and plan upcoming activities accordingly.

Mechanisms of alignment of large projects with state priorities

All of the large projects are conducted with increased state involvement and with complete alignment with state priorities. As one civil society actor explained, these initiatives tend to adopt an approach of “strengthening public institutions” and are generally instigated by international actors “to increase the capacity of PECs to offer Turkish language courses and skills training.” Projects by CSOs are reportedly written in collaboration with local and state actors:

In our events and projects, we use the municipalities’ feedback to detect the needs of refugees. We then go through the UN’s and EU’s funding opportunities to get a sense of what sort of projects we can undertake in collaboration with municipalities. When we establish that connection and re-evaluate the possibilities, we write a suitable project draft. We also conduct surveys before and during this step. With these surveys, we seek to understand what the local residents, the refugees, and the municipal staff are thinking. With the feedback we received we were able to create an initial model for the project. (Project coordinator, medium-sized local CSO founded in 1993, operating in twelve centers across Istanbul, working with protocols with municipalities and MoNE)

Another organization also expressed its desire to be involved in the strategic planning with MoNE:

They just need to issue the new education philosophy … I think they are very inclusive, holistic. They have a very holistic philosophy for the future … I’m not fully informed about the details of the program. We would want to participate in the planning and advocate on behalf of our principal sponsor. (Education officer, large-scale international CSO mandated for protecting and providing humanitarian assistance, working with protocols with MoNE)

Further, in an effort to develop partnerships the Ministry of Interior plans to hold regular consultations with the aim of developing cooperation between public institutions and CSOs and to form a “Civil Society Strategy” with the participation of around fifty CSOs and fifty state representatives. The goal of these meetings is to discuss needs and challenges in partnership. These organizations would design and implement projects in close collaboration with state institutions and ministries. One of the large CSOs describes the collaboration on all fronts (selecting PECs, assigning teachers, selecting a book, and deciding on a stipend) as follows:

We are going to be working with the Ministry of National Education in four provinces. We provide support for PECs, selected by the Ministry of National Education based on the number of refugees of course and the location. We are also going to be supporting PECs’ capacity. For language courses, and field training and infrastructure support … MoNE is going to assign teachers. But we are going to pay their salaries … We procured large numbers of Turkish language books from/for the Ministry. It was determined based on an open tendering, technical specifications given by MoNE. [The stipend amount] was decided by the Ministry, we would like to be in line with their system. (Education officer, large-scale international CSO mandated for protecting and providing humanitarian assistance, working with protocols with MoNE)

This rhetoric is one of consensus rather than conflict in that all actors should negotiate a “shared vision”Footnote 47 in an effort to align civil society to the state and eliminate dissent. We can also see that these large international organizations, which are implementing these projects, nevertheless remain perceived as temporary, non-official partners, often as material providers, while ministries and other state actors maintain a supervisory role. State institutions that oversee language education for adults have gradually become implementers of projects. The director of the Lifelong Learning Department at MoNE states that “for those projects, the EU–Turkey delegation provides funds and we execute.”

Further, the new institutions that were created to implement these programs are highly fund-dependent. A growing state apparatus and control over CSOs, however, do not necessarily equate to state dominance.Footnote 48 An official representative of this program highlighted the following:

If the funding continues to decrease and the program does not get funded, there are people working on this program who will need to be laid off. There was experience gained that should be transferred. (Expert at the YTB office)

In the absence of long-term policies and planning, the state often takes on the role of implementer of these projects. As such, despite an apparent increase in state control of CSOs and funds, the Turkish state struggles to gain autonomy from international actors, as it continues to shape its actions, reporting mechanisms to the demands of the funder.

Conclusion

This case study contributes to the literature on the relation of states and CSOs by examining the way in which state institutions handle the reception and integration of refugees on such a large scale. It illustrates a particular configuration of power relations that emerge as a state transforms from being a migrant-sending to also being a migrant-receiving country, in contrast with other relations documented in the literature about countries in the Global South.Footnote 49 It challenges the dichotomy in the relation between state and CSOs, whereby either one or the other plays a dominant role depending on the national context, or whereby the state asserts sole control, fearing weakened sovereignty or the emergence of oppositional movements, presenting instead the complex relationship between these two actors and the mechanisms through which the dynamics of this relationship evolve. In the particular case of the provision of language education to refugees in Turkey, the growing state apparatus and control over CSOs resulted in a hierarchization of CSOs and channeling of international funding toward larger projects that align their strategies with the state. Larger organizations have been allowed and encouraged to participate in decision making and strategic planning for the delivery of assistance. Yet, increased state control and centralization has not been accompanied by long-term state policies in the field of language education. This position of the state vis-à-vis civil society, delegating service provision while maintaining control, thus allowed the former to continue avoiding the adoption of long-term integration discourses and policies. By externalizing service provision to CSOs, the state avoids being perceived by the public as spending public resources on refugees. Consequently, it can continue to avoid engaging with tensions among the public as anti-refugee sentiment increases. Beyond the argument that CSOs in Turkey challenge the state in some regard, but that the state is by far the more powerful actor, this paper reveals a strategy that allows the Turkish state to continue to receive funding while keeping a strict control on civil society, preventing it from becoming as strong as in other Global South countries. In that sense, this emerging relationship effectively allows the state to avoid making policies, arguing that this is a safer option in the broader policy environment, considering the possible role of public opinion and the increasing tensions of the host society regarding the presence of refugees. Yet, this paper also shows that this type of interaction has some limitations with regards to the way in which services are provided to refugees in the field of language education. The large-scale projects that are preferred are oriented toward reaching the highest number of participants and measure success largely through enrollment and completion rates, while the smaller ones, which are better able to meet the specific needs of their beneficiaries, are excluded from operating in this context. Further, since these initiatives were not accompanied by further measures such as monitoring or evaluation, education continues to be provided on an ad hoc basis, despite the apparent centralization. It also means that humanitarian assistance will continue to come in and projects will continue to be implemented without leading to long-term changes in practices and improvement in the situation of both incoming and host communities unless priority is given to a long-term integration approach by all the actors involved.

Funding

This work was supported by a Mercator-IPC fellowship (2018-2019) and by a Seed Fund from Koç University SF.00080.