Introduction

In the summer of 1934, approximately 3,000 of the 13,000 Jewish inhabitants in Eastern Thrace were forced to leave the region due to heightened Turkish nationalist sentiments Hâkimiyet-i Milliye (15 July 1934). The attacks lasted approximately a little over two weeks, commencing at the end of June and concluding at the beginning of July 1934. Initiated by the civilians, the attacks first started in Çanakkale, but subsequently spread to surrounding cities such as Edirne, Kırklareli, and Tekirdağ. While the attacks did not result in casualties for the Jewish population, they involved raiding and looting of their homes and property in these cities. During the attacks, the government turned a blind eye, taking no serious steps to protect the small Jewish community in Thrace. This passive stance of the Turkish state during the attacks has – and for good reasons – been a matter of controversy among scholars. Typically, scholars have highlighted several factors that led the central government to tacitly approve the attacks towards the Jews: the role of the Republican People’s Party’s (Cumhuriyet Halk Fırkası; CHF) local officials in the affair (Toprak Reference Toprak1996); the rise of antisemitism in Turkey manifesting itself in the publication of two antisemitic journals, namely Milli İnkılâp and Orhun (Levi Reference Levi1996); and the state officials’ desire to “Turkify” the population (Bali Reference Bali2008; Karabatak Reference Karabatak1996) and remove non-Turkish segments of the population because of geopolitical concerns primarily regarding Bulgaria and Italy (Aktar Reference Aktar1996; Bayraktar Reference Bayraktar2006).

Despite their differences, the underlying theme of this debate focuses on whether this violent attack took place under the guidance and assistance of local and central state officials. While the civilian participation in the event is evident, the primary focus without exception has been on state-sponsored Turkish nationalism, which scholars viewed as the driving force behind such violent acts.Footnote 1 This view usually ignored the active role of civilians in such acts, tacitly assuming that ordinary people were passive bystanders, who could only act when provoked, triggered, and manipulated by the ruling elite. As part of this general indifference to the civilian participation in such incidents, scholars did not adequately address the role of Thrace’s social and economic context in fueling local antagonism.

This article addresses this shortcoming and proposes a closer examination of the regional dynamics. Rather than focusing on the extent of state responsibility, it deals with the understudied and subtle aspect of civilian participation: agricultural indebtedness and the practices of usury throughout the 1930s. More specifically, I refer to three interconnected developments, which, I argue, shaped the socio-economic aspect of the violence at the local level: the prominence of Jewish merchants in the Thracian economy as usurers; the local farmers’ exacerbated indebtedness due to the Great Depression; and the central state’s inability to address these issues with appropriate policies.

With its particular focus on the local context, this research refrains from state- and elite-centric perspectives predominant in the 1990s and early 2000s on the expulsion of Jews. During this period, the Kemalist secular–nationalist modernization trajectory came under heavy fire in relation to rising Kurdish nationalism, left-liberalism, and Islamism (Kasaba Reference Kasaba, Bozdoğan and Kasaba1997). The expulsion of Jews from Thrace in 1934 attracted scholarly attention in this intellectual climate, where scholars publicly criticized the exclusionary practices of the Republican regime, with the debate mainly focusing on issues such as minority rights, Turkification policies, and the illiberal nature of Republican modernization. Exposing the Kemalist tutelage (vesayet) had become a popular notion with the optimistic belief that Turkey had to face its history to create a more inclusive, democratic polity. This intellectual climate of the 1990s (and the early 2000s) left an important mark on Turkish studies, which resulted in an overt preoccupation with the state, the ruling elite, and their wrongdoings.Footnote 2 In that narrative, the portrayal of “the” state as a demonical, all-powerful, self-standing, and omnipotent entity has become a norm while the societal actors were either largely silenced or victimized.Footnote 3 Put differently, the referral to the role of “the state” and “the ruling elite” became a sufficient analytical tool to explain extremely complicated violent events in an easily digestible manner whereas the state and society are understood as dichotomous, isolated units with no interdependency (Gerlach Reference Gerlach2010, 4).

Recent generations of scholars effectively challenge this shortcoming, turning their attention to the intricate interrelationship between the local actors and the ruling elite in the execution of mass atrocities. In his study on the plunder of properties in genocidal settings, Ümit Kurt (Reference Kurt2015, 306), for instance, argues that “genocide in both exemplars (i.e. the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust) was far more than a mere reflection of a decision-making process exclusive to the political leadership.” Emphasizing the locals’ active participation in both cases, Kurt underscores the importance of material incentives that triggered self-radicalization at the local level. Uğur Ümit Üngör and Mehmet Polatel adopt a similar approach, arguing that an “analysis of bargaining and negotiating processes between state and society” and “interplay between top-down and bottom-up” must be considered in the destruction and confiscation of Armenian property (Polatel and Üngör Reference Polatel and Üngör2011, 3). Finally, Jacob Daniels takes a nuanced view of the dark history of mass expulsions in Thrace to examine the 1934 attacks. In his view, Muslims’ resentment of Jewish merchants’ presence in the local economy and the Turkish government’s behind-the-door support of the perpetrators were interrelated reasons that produced this antisemitic mob (Daniels Reference Daniels2017).

This research closely engages with this recent literature, particularly Jacob Daniels’ research. It underscores the complex interplay of state-sponsored nationalism with local dynamics and thus explores the attacks as part of broader and contingent dynamics of the 1930s in Thrace. The emphasis on the 1930s obviously does not ignore the long history of nationalism and anti-minority policies deeply rooted in the final decade of the Ottoman Empire. As is well known, these policies, also implemented assertively by the Republican elites, included assimilation and/or blatant discrimination, the confiscation of the so-called “abandoned properties,” and their transfer to Muslim Turks to create a national economy (milli iktisat) (Koraltürk Reference Koraltürk2011). However, as one penetrates the regional context of Thrace in the 1930s, it becomes evident that the underlying causes behind this civilian participation in the 1934 attacks also stemmed from contingent developments of the 1930s. Put differently, one should not reduce these attacks to the pre-determined, another inevitable by-product of nationalist policies.

In its endeavor to explore the local origins of violence, this research takes a snapshot of the local circumstances in Thrace in the first half of the 1930s. This emphasis on the spatial and temporal context is not merely a preference but rather a methodological necessity given that nationalist violence arises under specific political, social, and economic conditions and retreats in others. In other words, nationalist violence is neither a random occurrence nor a mere outcome of inexplicable, deep-seated primordial encounters. Understanding the peculiar context of each violent event is vital because, as Jacques Semelin notes, collective violence “is the product of a co-construction between a will and a context, the evolution of the latter being capable of modifying the former” (Semelin Reference Semelin2007, 10). Semelin’s emphasis resonates with the observation of Claude Lanzmann, who underlines that “a gulf lies between the desire to kill and the act itself” (quoted in Semelin Reference Semelin2007, 1). While the dark history of ethno-religious cleansing in the Empire and Turkey is well known to any student of the field, viewing the 1934 attacks as an inevitable outcome of long-lasting homogenization policies entirely overlooks “the gulf between the desire to kill and the act.” To overcome this shortcoming, I follow Lanzmann’s argument and develop a temporally and spatially sensitive explanation of how contingent developments, such as the Great Depression and exacerbated indebtedness, eradicated the gap between “the desire to kill” and “the act itself.”

In what follows, I discuss the importance of three developments in three separate sections. The first section discusses Turkey’s national political context during the 1930s, highlighting the prevalence of anti-minority and Turkification policies as well as the publication of two antisemitic journals, Milli İnkilâp and Orhun. While these issues should be considered to contextualize the attacks, they do not fully capture the local context that resulted in the breakout of violence in 1934. For this reason, the second section pays closer attention to the local voices, which resentfully emphasized some Jewish merchants’ involvement in usury in Thrace. While complaints about “the Jewish merchants” in Thrace existed as early as the 1920s, these resentments intensified in the 1930s in the context of the Depression years due to the exorbitant interest rates charged by usurers. I point out Jewish merchants’ involvement in usury as one major factor paving the way for violence. I substantiate this argument by utilizing a wide range of resources such as documents from CHF local party branches, minutes of parliament meetings, memoirs, and periodicals. In the final section, I link the issues of usury and high interest rates to the devastating impact of the Great Depression on Thrace’s rural social fabric dominated by small landowners. I show that the complaints over usury had intensified at a time when the plummeting prices of agricultural products adversely affected the peasants’ ability to survive in the market, making them highly reliant on outside financial resources, whether from usurers or from state institutions such as the Agricultural Bank (Ziraat Bankası) or credit cooperatives. Agricultural producers, however, received little support from state institutions despite local requests to create alternative credit sources. It was in this multi-faceted socio-economic context that Turkish–Muslim producers perceived the Jewish usurers as an easy target rather than tangling with the authoritarian single-party government.

Before proceeding, I would like to rule out a possible misunderstanding. Not all attacked Jews were usurers, and not all aggressors were debtors. In such collective events, the cause-and-effect relationship is not so straightforward because the motivations of aggressors are often “situational rather than rooted in grand political projects” (Üngör and Anderson Reference Üngör, Anderson, Knittel and Goldberg2020, 17). As Charles Kurzman (Reference Kurzman2005, 10) highlights,

participants do not know ahead of time exactly what is going to happen, at the moment they decide to protest, or not to protest, and the decision is made in a context of hearsay, rumor, conflicting predictions, and the intense conversations that surround breaks from routine behavior.

At the peak point of violence, a political bystander may have felt excited about the prospect of breaking his mundane routine, asserting his masculinity, or witnessing the pleasing aspect of collective action with individuals in his social circle. In other words, incidents of collective violence are complex events that occur “with the interweaving of collective and individual dynamics which are political, social and psychological by nature, to name a few” (Semelin Reference Semelin2007, 10). Here, my emphasis on the socio-economic factors does not downplay political factors such as antisemitism and Turkish nationalism. Instead, this research debunks the artificial separation between “economic factors” and “ideology” and highlights their intertwined characters. In the 1934 attacks, ongoing socio-economic problems reinforced antisemitism, which increasingly identified the Jewish community in Thrace with “greediness,” “profiteering,” and “exploitation.” Once this process of “demonization” was complete, the moral justification for the attacks was established, and the Jews’ properties had “rightfully” been put up for grabs by the locals.

The Turkish Republic as the zone of intolerance: Turkish nationalism in the 1930s

The 1934 attacks occurred when fully fledged Turkish nationalism was gaining deeper roots in politics, coinciding with “the advent of high Kemalism” (Çağaptay Reference Çağaptay2006). While policies of mass extermination, deportation, and expulsion have long been embedded in Ottoman history, the Kemalists made a greater effort to institutionalize Turkish nationalism through scholarly research on language and history (Okutan Reference Okutan2004, 247).Footnote 4 In line with this effort, the emphasis on Turkishness, Turkish national identity, and familiarity with the Turkish language became much more prominent in official documents. For instance, the CHF’s 1931 Regulation (Nizamname) mandated knowledge of the Turkish language and the adoption of Turkish culture as prerequisites for party membership (C.H.F. Nizamnamesi ve Programı 1931). In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the government more assertively imposed the use of the Turkish language through public campaigns, which violated non-Muslim groups’ rights to use their native tongue in public life and educational institutions (Okutan Reference Okutan2004, 167). This privileged position of Turks and the Turkish language normalized prejudice and discrimination towards both non-Muslims and non-Turkish-speaking Muslims (Kolluoğlu Reference Kolluoğlu2013).

It was in this general climate that non-Muslim (non-Turkish) communities in Turkey faced increasing pressure across various aspects of daily life. Starting in 1928, societal actors, with the support of state officials, launched a campaign known as “citizen, speak Turkish” to prevent the use of languages other than Turkish in public spaces (Çağaptay Reference Çağaptay2006, 15). In line with such public campaigns, there was also a conscious state policy to minimize non-Muslims’ role and activities in the economy. The Republican leadership pressured foreign enterprises to employ at least 75 percent Turkish–Muslim workers and fire non-Muslim workers if their number was above the set limit (Aktar Reference Aktar and Hirschon2004, 92). A report published by the World Jewish Congress in 1938 demonstrates that these policies concerned all enterprises in the country:

The Turkish manufactory employs a very small number of Jewish officers and workers. It is true that Turkish laws stipulate that only Turkish citizens are allowed to be employed; however, in practice, these (people) are expected to be Muslim. This requirement is so evident that even Jewish manufacturers could not find the chance to employ Jewish workers and officers in their enterprises (Bali Reference Bali2014, 176).

Finally, the parliament also enacted laws showing that the government approached non-Muslim (and non-Turkish) populations as a national security issue rather than treating them as ordinary citizens. For instance, the 1934 Settlement Law dictated the resettlement of “those communities not possessing Turkish culture” in various parts of inner Anatolia to blend the non-Turkish population with the Turkish people (Bozarslan Reference Bozarslan and Kasaba2011, 361). While its primary goal was to disperse Kurds, who it was believed would soon adopt “Turkish culture,” one should keep in mind that the attacks towards Jews in Thrace began on June 21, only a week after the parliament approved this law on June 16, 1934.

In addition to these policies, two other issues specifically concerned the Jewish community in Turkey. The first development pertained to the Jewish community’s school Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU). Founded by Parisian Jews in 1860, the AIU operated as a transnational institution, striving to elevate Jews’ social and economic conditions across the world through “European education and enlightenment” (Drucker Reference Drucker2015). The French rhetoric of mission civilisatrice had deeply inspired the AIU’s founding philosophy, equipping these schools with the additional duty of “Westernizing” their co-religionists in French colonies and the Empire (Rodrigue Reference Rodrigue1983). These schools proved instrumental in solidifying the communal ties among Jews and integrating them into the Ottoman imperial structure (Şar Reference Şar2010, 232).

During the first years of the Republic, the introduction of the Unity of Education Law (Tevhid-i Tedrisat Kanunu) in 1924 significantly changed the future of the AIU. The law enabled the government to bring all types of educational institutions, including minority schools, under direct state control and supervision. In what followed, the Republican officials restricted the use of the French language as the medium of instruction and demanded its replacement with either Turkish or Hebrew whereas most Jews in Turkey spoke Ladino and French, not Hebrew (Bahar Reference Bahar2003, 216). Thus, adopting Hebrew as the medium of instruction would mean adopting a language that Jews in Turkey did not widely use (Okutan Reference Okutan2004, 170). In the end, Turkish was adopted as the medium of education, but in either case, the government’s purpose was to disrupt the ties between local Jews and AIUs without technically violating the Lausanne Agreement’s clause regarding minority groups’ education rights (Oran Reference Oran2004, 87). The second problem faced by AIUs was aggravated financial difficulties (Bahar Reference Bahar2003, 62). The Turkish government had obliged these schools to offer Turkish language, history, and geography courses taught by Turks whose salaries were determined by the Ministry of Education and usually were higher than other teachers in these schools (Guttstadt Reference Guttstadt2012, 33; Güven Reference Güven2013, 63).

Another development concerning the Jewish community was the publication of two antisemitic journals, Milli İnkilâp and Orhun. Owned by Cevat Rifat Atilhan, an ex-officer in the Ottoman army, Milli İnkilâp described itself as a “rampant nationalist” (taşkın milliyetçi) journal with the aim to “make Turks master in their own country” (Milli İnkilâp 1 May 1934a, 1). The journal’s extreme hostility against Jews rendered it unique among the other publications of the era. In general, it highlighted the Jews’ alleged global economic domination and their “degenerate” and “immoral” essence. For instance, an article published there in 1934 described Jews as “social parasites” and “carrion crow,” engaging in customs brokerage and stock trading and taking advantage of every opportunity to assure their economic supremacy (Milli İnkilâp 1 June 1934c, 4; Milli İnkilâp 13 June 1934d, 2). Derogatory language was pervasive in Milli İnkilâp, as several pieces in the journal depicted the Jews as “timid, cowardly, conspiring, and deceiving people,” posing a threat to the Turkish nation (Lamprou Reference Lamprou2022, 35). In some cases, Milli İnkilâp went so far as to claim that the immoral essence of Jews made them “unfit” to be an integral part of the Turkish nation, even if they were to change their names and convert to Islam (Milli İnkilâp 1 May 1934a, 5).

Orhun, although more focused on historical and contemporary issues associated with Turkish history and Turkic people, was no less aggressive in its antisemitism. Nihal Atsız, the owner of the journal and a well-known fascist figure working as a teacher in Edirne High School, had identified three major enemies at home: communists, Jews, and sycophants (dalkavuk). While communists were accused of “selling their conscience to Karl Marx,” sycophants unconditionally supported their government and thus left no space for a critique of it. No less threatening were the Jews, “who are the enemy of whatever country they reside in.” For Atsız, Jews were “dishonorable merchants” who would not hesitate to betray their country to “put some money in their pocket” (Orhun 21 March 1934a, 94). Atsız’s identification of Turkishness with blood and ancestry led him to argue that a person in Lithuania or Siberia could still be called a “Turk” if he was a Turk by blood. Meanwhile, he considered Jews unable to become Turks even when “they went through the same stages of education with Turkish children” due to their historical reliance on “fraud” and “dishonesty” (Orhun 16 July 1934b, 159).

Although both journals were blatantly antisemitic, scholars still debate their impact on the 1934 attack. Ayhan Aktar suggests that there was no direct correlation between the attacks and these journals because there was no well-established communication network in Turkey to disseminate their arguments to a broader audience (Aktar Reference Aktar1996, 49). Conversely, a recent study implies that the impact of these journals might have gone well beyond their circulation rates as literate individuals would orally share news from the publications to a broader audience in public places such as coffeehouses (Öz Reference Öz2020, 108). While these journals may have played a role in promoting antisemitism, it would be an overstatement to give them a central role in the attacks without analyzing the regional conditions in Thrace. For this reason, the following section pays careful attention to the Jewish community in Thrace. More specifically, it discusses the Jewish merchants’ role in the Thracian economy, which drew complaints during the 1920s and the 1930s.

The activities of Jewish merchants and the role of usury in the expulsion of Jews in 1934

The historical context in which Jewish merchants assumed a prominent role in Thrace paradoxically coincided with the removal of almost all Christians from the region and the subsequent implementation of national economy (milli iktisat) policies – both well underway since the final decade of the Empire. The final years of the Empire witnessed the conscious policy to create “an economy in the hands of Turks and Muslims” by seizing the properties of Christian communities and transferring them to the nascent Turkish–Muslim entrepreneurs (Kieser Reference Kieser2018, 273). According to Yusuf Akçura, a prominent Turkish nationalist intellectual, “the sound establishment of the Turkish state” was contingent upon “the natural growth of the Turkish bourgeoisie” (Polatel and Üngör Reference Polatel and Üngör2011, 35). As it soon turned out, “the growth of the Turkish bourgeoisie” heavily relied on the state-sponsored policies that dispossessed non-Muslim communities through various means including boycotts, economic discrimination, and outright plunder (Polatel and Üngör Reference Polatel and Üngör2011, 61). The period from World War I in 1914 to the end of the National Liberation War in 1923 saw the aggressive implementation of these policies accompanied by the annihilation of Armenians and Greeks in Anatolia (Toprak Reference Toprak1995, 1–5). This pursuit of creating a strong native bourgeoise extended well into the Republican period.

By the end of 1923, the Christian population in Anatolia was almost entirely wiped out. Alongside their physical destruction, their commercial activities also ceased. However, this destruction did not automatically mean that the wealth was transferred to the Turks and Muslims in a linear manner. While the indigenous merchants in Anatolia were the primary beneficiaries of this process, regional variations continued to exist, and the developments in Thrace exemplify this point. In Edirne, for instance, the removal of Christians and the confiscation of their properties ironically contributed to the economic prominence not of Muslims but of Jews, who mainly filled the economic lacuna in the region during the 1920s. The scope of this wealth transfer was such that, by the 1930s, “three-quarters of money circulated in Thrace’s economy belonged to the Jews” (Başbakanlık Cumhuriyet Arşivi (BCA) 490. 1. 0. 643. 130. 1, 15). Although the Jewish merchants’ influence over the entire Thracian economy may be somewhat lesser than suggested by these sources, the Jewish merchants’ operations show that they were the chief rival to the well-off Turkish–Muslim merchants/entrepreneurs in Thrace.

The degree of Jewish merchants’ activities varied by city. In Edirne, they managed thirty-four enterprises out of fifty-two while the rest were owned by Turks/Muslims (Öz Reference Öz2020, 88). In other words, the Jewish merchants in Edirne assumed control of 70 percent of all commercial activities by the 1930s following the destruction of Christian communities. In Tekirdağ, Muslims constituted the majority in the Chamber of Commerce, making up nearly 75 percent of the registered members. While lacking a numerical advantage, the Jewish merchants held disproportionate influence over the local economy; they accounted for 30 percent of registered merchants in the Chamber of Commerce although the Jewish community constituted only 5 percent of the city’s population (Daniels Reference Daniels2017, 383). This disparity highlights the significant role of the Jewish merchants, who were particularly active in grain-selling (zahirecilik), wine making, dairy farming, wholesale trading, and commissioning (Koraltürk Reference Koraltürk2011, 197–199).

It thus comes as no surprise that the open complaints about Jewish merchants’ activities stretch back to the mid-1920s. From 1923 to 1927, local newspapers, such as Milli Gazete and Trakya-Paşaeli, accused the Jewish community of dominating the Thracian economy and exploiting the Turkish peasants (Öz Reference Öz2020, 75–76). Like these complaints, nationalist campaigns such as “citizen, speak Turkish” and the aggressive implementation of national economy policies and the “Turkification” of minorities also date to the 1920s. With this tension in mind, it is worth noting that materially incentivized aggressors, resentful of “Jewish dominance,” did not target the Jewish merchants in the 1920s despite their intensified economic activities in Thrace. This raises the question of why the hostility against the Jews escalated into open, fully fledged ethno-religious violence in the 1930s but not in the 1920s.

A part of the answer lies in some Jewish merchants’ involvement in usury in the 1930s when the Great Depression ravaged the region and the country, especially in rural areas. This apparently aggravated the perception of Jews as “a greedy and alien” community, adding fuel to the fire. Complaints issued by the CHF local party branches provide a concrete illustration of this point, and while not exclusively, these complaints coincide with the post-Depression period. For instance, in 1931, the Çanakkale branch recommended “fierce legal measures” against the Jewish merchants accused of engaging in usury and appropriating the properties of those who could not pay their debts. The complaint pointed out the relatively high interest rates charged by the merchants, which resulted in the dispossession of the borrowers (BCA 490. 1. 0. 493. 1985. 1, 25). The document emphasizes the necessity of decreasing annual interest rates, which reached as high as 60 percent, calling for legal safeguards against “Jewish profiteering” (BCA 490. 1. 0. 493. 1985. 1, 22).

The CHF deputies of the region also highlighted the role of the Jewish merchants as usurers in Thrace. For instance, in a parliamentary speech delivered in 1933, Çanakkale deputy Ziya Gevher pointed out the detrimental effects of the usurers and implicitly targeted Jews:

Here we have colleagues coming from Edirne, Çanakkale, Gelibolu, and Ayvalık who put up with usurers from alien elements. They do not only charge money, colleagues. After charging 100 percent interest, they purchase grains and products from people at a half rate and thus increase the rate to 500 percent [in total] (TBMM Zabıt Ceridesi 8 June 1933, 98).

Such exorbitant interest rates made the agricultural producers’ survival in the market unlikely, if not entirely impossible. Mehmet Şeref Aykut, the Edirne deputy, expressed similar concerns over this issue:

Today if you apply any courts, you will see that they are working on behalf of usurers who rob, sink, and finish the Turkish farmers. … Fifteen days would suffice for you … to see how the Turkish farmers are being crippled by the usurers (BCA 491. 1. 0. 0/568. 2263. 3, 111).

The active involvement of Jewish merchants in usury is also confirmed by non-state sources. Rifat Bali, for instance, quotes the Edirne-born socialist politician Mihri Belli, highlighting that “the one and only source of credit for the peasant are the usurers in the market all of whom are Jews” (quoted in Bali Reference Bali2008, 41). Bali’s research is in line with Belli’s observation, demonstrating the active role of Jewish merchants and usurers “who not only dominated the economic activities” but also “provided credits to the peasants.” An oral history account of Mehmet Atar, born in Çanakkale in 1920, likewise refers to Jewish moneylenders “who get rich by commercial activities, burden peasants with debts, and appropriate peasants’ properties if peasants are unable to pay back” (Esenkaya Reference Esenkaya2005, 35). It is probably for this reason that the report by the Consulate General of Switzerland in Turkey presented the expulsion of Jews in 1934 as “a wonderful opportunity” for “the peasants to get rid of the Jewish usurers to whom they were indebted” (Bali Reference Bali2008, 346).

Milli İnkılâp eagerly exploited these economic tensions, agitating the Turkish–Muslim producers against the Jewish usurers. In May 1934, a month before the attacks, the journal published an article entitled “The peasants should be saved from the hands of merchants” (Köylüyü, bezirgânların elinden kurtarmalı). The article claimed that Çanakkale was economically under the total control of Jews: “Here are the files in the offices of enforcement (icra dâiresi)! Most creditors among these files are Jews. All farms in villages are now in the hands of Jews. Peasants can now only use these lands by leasing them.” Then it asked the government to inspect the sale of lands, as [peasants] lose them “at dirt cheap prices (yok pahasına)” (Milli İnkilâp 15 May 1934b, 4).

Criticisms against the Jewish community were also voiced by a top-ranking government official, İbrahim Tali (Öngören) – the General Inspector of Thrace with broad administrative authority. Following his appointment, Tali conducted an inspection tour starting on May 6, 1934, and compiled a comprehensive report about Thrace. While attributing economic problems in the region to the Jews, he also, somewhat paradoxically, acknowledged their functional role in the economy and reported that “Thracian peasants are afraid that their products will be wasted unless the Jews open their pocket” (BCA 490. 1. 0. 643. 130. 1, 91). Here, he most likely referred to the merchants who provided cash advances to the producers, making it possible for them to finance their activities and but in return bought “their products at dirt cheap prices” (BCA 490. 1. 0. 643. 130. 1, 33). Largely written with an antisemitic tone, the report also accused Jews of espionage and spreading communist propaganda.

In considering that this report was completed only two weeks before the attacks in June, Hatice Bayraktar justifiably points out İbrahim Tali’s role in the expulsion of the Jews, stating that he “used local party functionaries to carry out his plans by applying unofficial pressure” (Bayraktar Reference Bayraktar2006, 105). However, it would be wrong to assume that his report alone instigated the attacks. Complaints about Jewish usurers preceded his tour, with antisemitic sentiments running deep in regional politics. Moreover, the fact that he compiled this ninety-page report in just a month hints that Tali’s information possibly relied on local informants and his day-to-day interactions with the locals. At the end of his trip, he emphasized that he “had learned a lot” from the people in Thrace during his investigation in the region (Cumhuriyet 21 June 1934, 2). While he and the local party functionaries/state officials may indeed have played a role in the attacks, it would be naïve to think that İbrahim Tali alone fabricated local resentments. Moreover, even if the aggressors attacked their Jewish neighbors based on İbrahim Tali’s direct order, one should keep in mind that “individuals do not often uncritically act based on clear orders,” and they often tend to interpret these orders “in ways that advance their own interests” (Üngör and Anderson Reference Üngör, Anderson, Knittel and Goldberg2020, 18).

Attacks against Jews started in Çanakkale on June 21, 1934. Despite early rumors of the government’s plans to remove Jews “through special arrangements,”Footnote 5 Jewish residents did not abandon the region, believing that no harm would come from their Turkish neighbors (Haker Reference Haker2006, 250). This optimistic perception shifted rather rapidly following the outbreak of attacks, which reminded some Jews of the “1915 incidents.” One witness reported that aggressors from “mountains and countryside” (dağlardan ve kırlardan) arrived in the city center (of Kırklareli) to purge and kill the Jews who “controlled the agriculture and commerce” (Koçoğlu Reference Koçoğlu2002, 166). At least some of the aggressors were motivated by material gain, as one expressed flagrantly: “The intention was not to kill Jews but to take away their goods” (Haker Reference Haker2006, 255). Aggressors broke into Jewish houses and stores and “purchased” their possessions, valuables, and assets at meager prices (Koçoğlu Reference Koçoğlu2002, 163). Meanwhile, Jews’ immovable properties also changed hands following the Jewish departure from the region. For instance, in Edirne, Kaleiçi, where well-off Jews lived, “too many houses were sold” and taken over by Turks following Jews’ departure (Borakas Reference Borakas1987, 50; Öz Reference Öz2020, 133).

With the evidence available, it is impossible to unearth each aggressor’s individual motives. However, it is clear that a complex interplay of economic competition and diverging economic interests was at stake. For the well-off Muslims and Turks, the expulsion of Jews from the region meant the weakening, if not the elimination, of a local rival. For underprivileged ones, the expulsion of Jews meant an opportunity to get their “fair share” of Jewish properties and end their financial dependence on Jewish usurers. The case of the Polikar family substantiates this latter point. One of the wealthiest families in the Jewish community in Kırklareli, the Polikar family owned a distillation plant producing various alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks, including wine, rakı, and hardaliye Footnote 6 (Haker Reference Haker2006, 221). Moreover, the Polikars were in the business of commercially exporting sheep to Bulgaria while also selling dairy products to the surrounding villages and towns (Haker Reference Haker2006, 222). Perhaps, more importantly, one of its members, Azarya Polikar, was engaged in lending money to the peasants, thanks to his family’s wealth.

Azarya Polikar was one of the Jews attacked by the locals. According to Erol Haker’s account, one of Polikar’s debtors visited him in his store on the day of the attacks before the store was closed. As the debtor and Polikar were together drinking rakı in Polikar’s store, a large crowd of aggressors suddenly raided the store, but the attacks did not end there. As Polikar tried to escape, the crowd followed him on his way home and plundered his house. Haker’s account emphasizes that Polikar had provided cash advances to peasants, which he could not get back after this incident. He and his family then left Kırklareli, taking a train to İstanbul with 3 liras, whereas the debtor owed him 4,000 liras (Haker Reference Haker2006, 258–259).

While materially incentivized, aggressors in Kırklareli also targeted religious figures such as the rabbi Moşe Fintz, alongside wealthy Jews such as Simanto Aviente and the members of the Adato family (Haker Reference Haker2006, 259). Civilian participation, however, was not limited to aggression; there were also a few cases where Turkish–Muslim people defended their Jewish neighbors, with some going as far as to threaten to shoot the aggressors (Haker Reference Haker2006, 235–236). In some other cases, indebted local producers sought to pay a visit to the exiled Jews. In one such instance, a heavily indebted local producer paid a visit to İstanbul to find a Jewish merchant named Moşon Salinas, who, like Azarya Polikar, provided credit to the locals and moved to İstanbul from Kırklareli right after the attacks. According to Haker’s account, both the debtor’s name and that debtor’s status as an aggressor remain unknown although Haker shows that this debtor traveled to İstanbul in the hope of paying his debt to Moşon Salinas. By the time the debtor found the Salinas family in İstanbul, Moşon Salinas had already passed away, and the debtor paid his debt back to Salinas’s wife, Miriam (Haker Reference Haker2006, 235–236).

After the attacks, Kazım Paşa (Özalp), the President of the Grand National Assembly, declared that aggressors would be penalized according to the provisions of the Republican laws (Son Posta 8 July 1934, 3). The attitude of the local newspapers, however, proved to be a bit trickier. While warning locals that “the government will not allow provocations against citizens,” they concurrently accused prosperous Jewish merchants, including Azarya (Polikar), along with Yusuf Adato and Mişon Salinoz (Moşon Salinas), who had adopted a “hostile attitude towards Turkish sons and daughters for years,” and did their utmost to suppress the activities of Turkish merchants (Trakya’da Yeşilyurt 10 July 1934a, 2). For instance, Trakya’da Yeşilyurt asked, “Do our Jewish citizens bear no responsibility at all in this incident” (Bu hadiselerde Musevi vatandaşlarımızın hiç mi kabahati yok), noting that Jews had so much monopolized the production of dairies that “they raised every difficulty for the Turkish child to buy even a small dairy farm” (Trakya’da Yeşilyurt 23 July 1934b, 1).

Official reports, parliamentary minutes, and local and national newspapers consistently associate economic problems with the prosperity of Jewish merchants and their involvement in usury. As highlighted above, the Jewish merchants were undeniably active in the Thracian economy. Nevertheless, various sources of the Republican era unfairly present the antagonistic image of “exploited Turkish sons and daughters” versus “the greedy, blood-sucking, immoral Jews.” This presentation stigmatizing the Jewish merchants appears somewhat unfair because exorbitant interest rates charged by usurers remained a country- wide problem in the 1930s, with interest rates being as high as 120 percent (Tökin Reference Tökin1990, 146). Despite this widespread issue, official and non-official documents exclusively targeted Jews based on their involvement in usury. This supports Jacob Daniels’ contention that “the economic nationalism indicted the Jew twice: first as foreigner and then as small merchant” (Daniels Reference Daniels2017, 376).

While the sources utilized above demonstrate residents’ stereotypical perception of Jewish merchants, they remain silent about the reasons for producers’ increased reliance on the usurers, Jewish or not. Understanding the complex temporal background of the attacks requires going beyond what Jewish merchants did or did not do and examining the Great Depression’s impact on the region’s social fabric. The attacks occurred when economic hardship in the agricultural sector had reached its peak and the central government proved incompetent in addressing this crisis in favor of peasants, particularly for those with limited financial resources at their disposal and reliant on outside financial support. The government’s incompetence, small agricultural producers’ deteriorating economic conditions, and the dominance of this segment of the Thracian peasantry added another layer to the ongoing tensions, contributing to the escalation of violence.

The entangled contradiction: the Great Depression and agricultural indebtedness

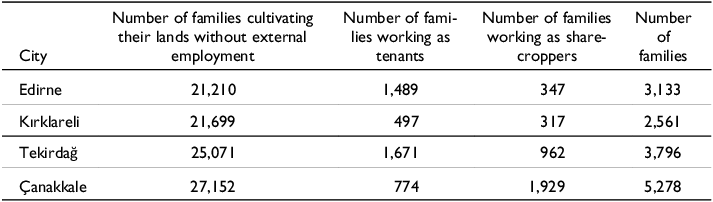

In the early years of the Republic, Thrace was a predominantly rural region. Approximately 70 percent of the entire population in Çanakkale and Tekirdağ, 60 percent of the population in Edirne, and 80 percent of the population in Kırklareli were cultivators (1927 Tarım Sayımı 1970, 19). The dominant group within the peasantry in Eastern Thrace was land-owning and relatively independent peasants, who possessed enough land for self-subsistence and did not need external employment, as shown by the statistical figures in Table 1.

Table 1. Land ownership in Thrace in the late 1930s

Source: T.C. Başvekâlet İstatistik Umum Müdürlüğü (1941, 18–21).

This rural social fabric of Thrace dominated by small landowners was further solidified by constant immigration between the 1877–1878 Ottoman–Russian Wars and the mid-1930s. By the 1930s, approximately one-third of locals in Thrace were born in other countries such as Greece or Bulgaria, and these migrants were predominantly peasants, increasing the proportion of peasant families by at least 30 percent in Kırklareli, Tekirdağ, and Edirne (Oluç Reference Oluç1946, 44–50). Perhaps more importantly, the demographic changes in Thrace reinforced the dominant position of small ownership and divided the cultivated lands into smaller pieces.

One important characteristic of small agricultural producers is that they generally own a piece of land for self-subsistence but lack extra financial means to sustain their activities. This brings heavy reliance on loans and advances to cultivate the land as they operate with extremely limited resources. More importantly, this segment of the agricultural producers is not isolated from the market, its pressures, and fluctuations. This was also the case in the commercialized, market-oriented economy of Thrace in the 1930s, where peasants relied on the market to maintain subsistence (Akçetin Reference Akçetin2000).

In times of crisis, this dependency on the market works to the disadvantage of small and mid-sized producers with few financial resources. As Birtek and Keyder mention:

The middle farmer is in a marginal situation in terms of his ability of surplus production; small shifts in the parameters may force him into a deficit situation. The fact that his surplus is small implies his inability to plan for marketing over a period of time. Unlike the large surplus producer, he cannot protect himself against a short-term decline in price, or profit from speculation (Birtek and Keyder Reference Birtek and Keyder1975, 449).

This fragile position of small agricultural producers became all the more apparent in the early 1930s. According to İsmail Hüsrev Tökin, “the Great Depression (buhran), without exception, ravaged all segments of the peasantry. However, it was the small, economically weak peasantry that suffered the most severe blow” (Tökin Reference Tökin1990, 42). In the 1930s, vulnerable producers found themselves trapped in a growing cycle of debt due to the declining prices of their products, particularly grain (Genelkurmay Başkanlığı Coğrafya Encümeni 1944, 40). Whereas wheat prices declined by 50 percent, the prices of other important crops in the Thracian economy such as grapes, figs, and tobacco fell by about 20 to 30 percent (Başar Reference Başar1931, 23–81). In 1931, producers in Tekirdağ complained that “the prices of grain are so considerably low that [this situation] puts them and merchants (ziraat ve ticaret erbabı) in a very inconvenient position” (Tekirdağ Vilayeti Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası 1931, 74). As prices decreased, the small producers needed additional financial means through credit, which became increasingly difficult to discharge because of the loss in revenue. As producers had trouble paying their debts back, interest rates skyrocketed, which subsequently deepened producers’ already crippling debts. As American experts succinctly put it, “farmers are so indebted that it is impossible for them to discharge their debts and receive credits once again” (Atasağun Reference Atasağun1943, 225).

In Turkey of the 1930s, the only institutions capable of lessening the burden of indebtedness through appropriate credit policies were credit cooperatives and the Agricultural Bank. That being the case, the Agricultural Bank “did not even come close to satisfying the needy peasant” (Emrence Reference Emrence2000, 33). A report penned by İbrahim Tali Öngören in 1935 supports this contention as it refers to the producers withdrawing from the market “due to not having access to the credit” (BCA 30. 10. 0. 0/72. 474. 8, 2–4). Producers with inadequate financial resources were thus left with two options: either to borrow money from usurers “who secure the credit from the bank by 8 percent to 10 percent interest rate per year but loaned it to the peasants by 10 percent interest rate per month” or not to obtain the required financial resources at all (Milli Gazete 6 August 1934b; Tezel Reference Tezel1982, 364).

In response, the local producers expressed their frustration through their ties with the branches of the CHF in Çanakkale. For instance, in 1931, some members of the Çanakkale branch sent a letter of complaint to the party headquarters, demanding the Agricultural Bank expand its institutional base in the region:

For their agricultural affairs, the farmers need to borrow money with excessive interest rates from profiteering moneylenders because there is not a unit of Agricultural Bank in our sub-province (Eceabat, Çanakkale). Farmers are unable to pay the interest back and fall into severe poverty. There is an urgent need to establish the Agricultural Bank’s unit and transform it into an institution solely concerned with agricultural affairs (BCA 490. 1. 0. 493. 1985. 1, 27).

There were similar requests in the other cities of Thrace. Tekirdağ, for instance, was “desperately in need of [national] banks,” and the opening of two more branches (by the Agricultural and the Ottoman Banks) would be both recommended and welcomed, as suggested by the city’s yearbook (salname) (Tekirdağ Vilayeti Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası 1931, 26).

While such requests demonstrate the bank’s weak institutional presence, such a presence, once established, would not automatically resolve the issue. Producers faced significant challenges even when they secured credit as the bank required such loans to be paid back with interest within one year – an extraordinarily short amount of time to clear the debt (BCA 490. 1. 0. 493. 1985. 1, 28). Indeed, by 1932, only 2 percent of the total credit allocated to producers constituted long-term credits (Atasağun Reference Atasağun1943, 225). To make matters worse, contingent factors also occasionally hindered producers’ ability to repay their debts. If a producer was fortunate enough to secure credit from the Agricultural Bank, unfavorable climate, poor weather conditions, or even a slight decrease in production made the loan virtually unpayable. Indeed, Thrace witnessed an exceptional drought in 1934, the year of the attack, as evidenced by the low precipitation in the region. This unfortunate climactic condition, in turn, resulted in 1934 having the lowest agricultural yield per hectare, making it, along with 1932, one of the worst years in terms of productivity during the entire 1930s (Oluç Reference Oluç1946, 70). In Vize, Kırklareli, producers petitioned the Agricultural Bank to postpone their repayment due to the climate conditions and the resulting low productivity (BCA 490. 1. 0. 0. 495. 1994. 2, 26).

By the early 1930s, the credit problem had become an “elephant in the room” in Turkey’s politics. It constituted one of the important factors garnering mass support for the short-lived opposition party, the Free Republican Party, led by Fethi Okyar (Emrence Reference Emrence2000, 41).Footnote 7 The party’s rapid establishment of local organizations in cities like Edirne enabled it to attract support from disenfranchised groups such as peasants adversely affected by the Great Depression (Ceylan Reference Ceylan2021, 280).

The government consequently recognized the danger of economic problems turning into outright political resentment and took a more active role in addressing credit-related problems (Varlık Reference Varlık1980, 105). While cooperatives represented a viable solution in theory, in practice, usurers tended to take control of them and render them virtually ineffective (Tökin Reference Tökin1932, 43). In other cases, these cooperatives only served to exacerbate the peasants’ reliance on usurers. As Akçetin argues, “credit cooperatives did not prevent usurers from dealing with peasants in need of liquid money” because “peasants had to borrow more money from usurers to be able to pay the cooperatives and become shareholders” (Akçetin Reference Akçetin2000, 93). In Thrace, the insufficient institutionalization of cooperatives represented yet another pressing issue: despite the existence of twenty-two cooperatives with a total budget of 78,065 liras in the region by 1932, Serap Taş’s study demonstrates that the General Inspector reiterated in 1936 the urgency to establish new cooperatives that would be “the first blow to the Jews” (quoted in Koçak Reference Koçak2010, 143).

The period in question also witnessed increased efforts to regulate usury through new legislation. After recognizing the exorbitant interest rates charged by usurers, the parliament passed the Law on the Affairs of Lending Money in 1933 to regulate moneylending within legal boundaries. More specifically, this legislation set a maximum interest rate of 12 percent, requiring individual creditors to receive authorization from the government before lending money. Usurers were only allowed to exceed this pre-determined interest rate if they agreed to make additional payments to the government (TBMM Zabıt Ceridesi 8 June 1933, 91–92). Perhaps more strikingly, the Law on the Affairs of Lending Money increased the bank’s interest rate from 9 to 12 percent, even to the dismay of the deputies (TBMM Zabıt Ceridesi 8 June 1933, 98). The government would only reduce the interest rate to 9 percent in 1935 and 8.5 percent in 1938, and only after the country had largely overcome the adverse impacts of the depression (Kazgan Reference Kazgan2017, 58). In other words, peasants suffered from the lack of alternative credit sources in the most difficult years of the Great Depression, which only exacerbated their dependence on usurers.

In his essay on the link between economic crisis and nationalism, Rogers Brubaker argues that what triggers nationalist sentiments is not the economic crisis itself but rather the political response to it (Brubaker Reference Brubaker, Calhoun and Derluguian2011, 96). The 1934 attacks support this argument, where one observes a complex interplay of Turkish nationalism with the Great Depression, indebtedness, and some Jewish merchants’ involvement in usury. In another political context, the locals’ resentment of the depression, their reliance on usurers, plummeting agricultural prices, or insufficient government support could have triggered anti-government and anti-elite protests. One cannot help but wonder whether the fate of Thracian Jews would have been different had there been an opposition party channeling this socio-economic resentment toward the political party in power. In any case, this possibility ceased to exist in 1930, when the opposition party – the Free Republican Party – was shut down. Under these circumstances, scapegoating the small Jewish population in Thrace was surely a safer option than confronting the authoritarian single-party regime of the 1930s.

Conclusion

Viewed in hindsight, one may be tempted to view the 1934 attacks as inevitable given the long history of ethnic cleansing and mass extermination in the Empire and, later, Turkey. While useful in demonstrating that these violent events exhibit striking continuities, this approach runs the danger of situating the 1934 attack as the representative of another foreseeable event of violence. Moreover, this type of linear explanation leaves no room for human agency – whether by civilians or politicians. To avoid such deterministic explanations, Jacque Semelin urges scholars “to study the eighteenth century without knowing that the (French) revolution took place” (Semelin Reference Semelin2007, 63). Applying this method to the 1934 attacks, one immediately notices that Turkification policies, ethnic homogenization, or the desire to create a “national economy” all fall short of explaining the 1934 attacks, as these processes were underway well before 1934.

Alternatively, this article argues that understanding the local context is necessary to analyze how these attacks were intertwined with wider dynamics in the region. Following Semelin’s advice, this study explored the complex interplay between politics and the economy, the local and the national, and, finally, the ruling elite and civilians. By doing so, it situated the 1934 attacks in a broader context. In this story, both structural factors and human choices played a role. On the one hand, the adverse impact of the Great Depression, the decreasing prices of agricultural products, and the state institutions’ weak presence in the localities were all structural factors that extended well beyond the immediate control of the ruling elite. On the other hand, the implementation of nationalist policies, the desire to create a national and Turkified economy, and the suppression of minorities were the policies embraced and implemented by the ruling elite. The 1934 attacks occurred when these contingent developments and political choices interacted with the civilians’ resentment at the local level, leading to the partial destruction of the centuries-old Jewish community in Thrace.

Competing interests

None.