In memory of Wolf-Peter Funk, 1943–2021

1. Fate of a Manuscript: Discarded, Recycled, Rediscovered

The manuscript under discussion here, edited for the first time in this article, is part of the Phantoou find, a group of parchment codices that once belonged to the library of the Monastery of the Archangel Michael at Phantoou, an ancient site in the western part of the Fayyūm. The ruins of the monastery are located near the present-day village of al-Ḥāmūlī. The manuscripts were found in a stone cistern by a group of farmers in 1910. After having changed hands several times, most of the codices – forty-seven in total – were purchased by the famous American financier John Pierpont Morgan. Today, these manuscripts are housed at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York.Footnote 1

The Phantoou manuscripts are large in size, which, as Stephen Emmel observes, ‘shows that they were made for the purpose of public reading during church services’.Footnote 2 Most of the codices are written in Sahidic Coptic and comprise various biblical, hagiographic and homiletic texts. One such codex – housed at the Morgan Library & Museum under inventory number M.585 and designated in Leo Depuydt's catalogue as P.MorganLib. 166Footnote 3 – is MICH.BM,Footnote 4 which contains three texts in Sahidic: the Martyrdom of Leontius and Publius (cc 0519), Encomium on Leontius, attributed to Severus of Antioch (cc 0344) and Miracles of Menas (cc 0231).Footnote 5 Like most of the Phantoou codices, MICH.BM was found in its original binding, made from papyrus boards and leather coverings.Footnote 6 Leaves extracted from an older parchment codex were pasted down to the inside of the covers of the codex and are the sole remnants of the Fayyūmic manuscript designated in Depuydt's catalogue as P.MorganLib. 265.Footnote 7

Both paste-downs were made up of several parchment fragments, designated by Depuydt as frs. (a), (b), (c), (d) and (e). The upper paste-down was made up of frs. (a) and (b); the lower one of frs. (c), (d) and (e). Fr. (b) is a complete manuscript leaf, which I designate fol. (b). Frs. (c) and (a) join and make up a complete folio, which I designate fol. (c + a). Frs. (d) and (e) also join, forming the innermost side of the leaf, which I designate fol. (d + e). The outermost side of fol. (d + e) is lost. Both fol. (c + a) and the innermost side of fol. (d + e) were probably cut in two at the bindery.

When making the paste-downs of MICH.BM, the binder needed to paste several parchment fragments together, because the covers of MICH.BM were larger than the untrimmed leaves of P.MorganLib. 265 and even more so in those cases when the edges of the leaves were trimmed by the binder.Footnote 8 To produce the upper paste-down, the binder rotated frs. (a) and (b) by 180° and attached the verso of fr. (a) to the recto of fr. (b), so that fr. (a) would extend fr. (b) from below. To make the lower pastedown, the binder attached fr. (c) to fr. (d), the recto of fr. (c) facing the verso of fr. (d) – both rotated by 90° anticlockwise – so that fr. (d) would extend fr. (c) from above. He then attached fr. (e) to frs. (c) and (d), the recto of fragment (e) – also rotated by 90° anticlockwise – facing the rectos of frs. (c) and (d). Both paste-downs were then attached to the papyrus boards.

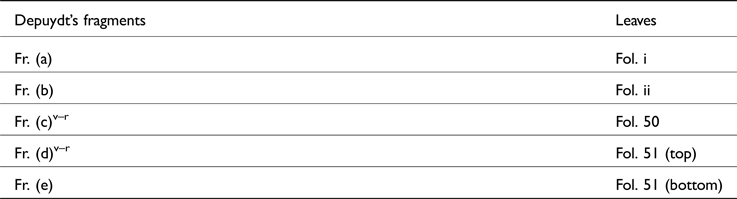

In 1912, the Morgan Phantoou codices were sent to the Vatican Library for restoration. There, the restorers separated the original binding of MICH.BM from its text block and its paste-downs from its covers. The manuscript, along with its covers and paste-downs, was photographed for the facsimile edition, published in 1922.Footnote 9 Fragments of P.MorganLib. 265 were separated from each other, inlaid in modern parchment and bound together with the text block of MICH.BM. The codex then received modern binding, while the original binding received a new housing and was assigned a new inventory number – viz. M.585A.Footnote 10 In the rebound codex M.585, the Fayyūmic fragments occupy fols. i–ii and 50–1. This position reflects the one they had when they were pasted together; thus, frs. (a) and (b) are upside down, and frs. (c), (d) and (e) are rotated by 90°. For the same reason, the versos of frs. (c) and (d) precede their rectos. The correspondence between the division of Depuydt's fragments and the modern foliation is given below.Footnote 11

In sum, P.MorganLib. 265 seems to have had a veritable afterlife. After it became worn out, this codex made its way to the binder's shop, where three of its leaves were reused as paste-downs of another codex, MICH.BM. This latter codex, along with many other manuscripts from the Monastery of the Archangel Michael, was eventually hidden in a stone cistern, where, centuries later, it was rediscovered by Egyptian farmers. Then, at the Vatican, the restorers removed the paste-downs from MICH.BM, separated the fragments of P.MorganLib. 265 from each other and rebound them with the rest of MICH.BM. It is in this state that the fragments are now available to researchers visiting the Morgan Library & Museum in New York.

2. Description of the Manuscript

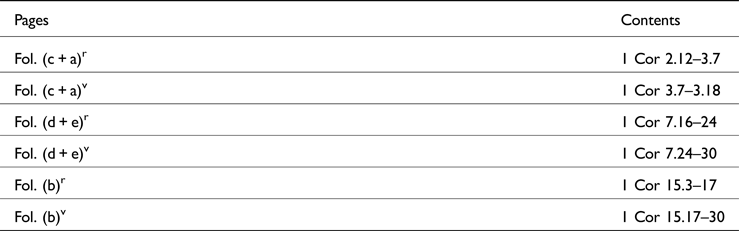

Having discussed the fate of P.MorganLib. 265, I now turn to a description of the manuscript and its contents. All three extant leaves of P.MorganLib. 265 comprise portions of Paul's First Letter to the Corinthians in Fayyūmic. It seems certain that, when the codex was intact, it contained the complete text of this letter. It is also plausible that the codex contained more than one text. Although it is impossible to ascertain what these lost texts might have been, the most likely possibility is that the codex comprised Pauline letters.Footnote 12 The contents of each surviving page of P.MorganLib. 265 are summarised below.

The original page size of P.MorganLib. 265 can only be measured approximately. Fol. (d + e) is of no use for this purpose, since it is missing not only its outermost side but also its upper margin. Fol. (c + a) is taller than fol. (b) – 320 mm vs 287 mm – and thus may preserve the manuscript's original upper and lower margins. Conversely, fol. (b) is broader than fol. (c + a) – 253 mm vs 234 mm – and thus possibly preserves the manuscript's original left and right margins. That the height and width of fols. (c + a) and (b) are different probably indicates that, before the fragments were pasted down, the edges of the leaves that had experienced natural deterioration were cut off.

None of the extant margins seems to preserve any page numbers, which most probably indicates that the three surviving leaves were not paginated.Footnote 13 The text of the manuscript is divided into two columns. The longest columns – viz. col. ii of fol. (d + e)r and col. i of fol. (d + e)v – comprise forty-one lines; the shortest column – viz. col. i of fol. (c + a)v – thirty-seven lines.

The text is written in unimodular uncials. Vertical strokes are upright and thick and horizontal strokes thin, with curved strokes alternating between thicker and thinner segments (e.g., the letter ⲟ is written in one stroke, whose left and right edges are thick and upper and lower edges thin). The letters ⲝ, ⲣ, ⲯ, ϣ, ϥ and ϯ extend below the baseline; the letter ⲫ breaks the bilinearism both at the top and at the bottom.

Two letters have shapes attested only in Fayyūmic manuscripts – viz. ϣ and ϭ. The letter ϣ seems to be written in three strokes, with a thick vertical stroke connected to a finned stroke at the top and a horizontal stroke at the bottom; the horizontal line stretches to the left then takes a sharp turn and extends all the way back to the right. The letter ϭ is usually written in two strokes, with a circle resembling the letter ⲟ and a diagonal stroke stretching from the lower edge of the circle to the right. However, in at least three instances,Footnote 14 the scribe did not give the letter ϭ this uniquely Fayyūmic shape; instead, in these cases, the oblique stroke joins the left edge of the circle and stretches to the right, reaching the bottom of the preceding line.

There are two other letters in P.MorganLib. 265 written in two different shapes – viz. ⲁ and ⲙ. The letter ⲁ is usually made up of two thick oblique strokes connected at the top and joined by a thin oblique middle stroke at the bottom. However, occasionally the letter is shaped differently, with a thick vertical stroke joined to a curved stroke on the left and a thin horizontal stroke on the right; the horizontal stroke connects ⲁ with the following letter. As for the letter ⲙ, it seems to be always written in three strokes, usually with two thick vertical strokes connected by a curved middle stroke. Sometimes, however, ⲙ is written in three concave strokes, the right stroke extending along the baseline and connecting to the following letter.

When it appears near or at the end of the line, the letter ⲧ is sometimes enlarged, its vertical stroke being written above the adjacent letters. For the same reason – i.e. to accommodate more text – when the combination ⲟⲩ occurs at the end of the line, the letter ⲟ is sometimes significantly reduced in size and written above ⲩ (see ⲛⲓⲉⲛⲧⲟⲗⲏⲟⲩ at 1 Cor 7.19 and ⲡⲟⲩ|ⲉⲓ at 1 Cor 7.20). Other letters written towards the end of the line can also be reduced in size; of those, ϥ is especially noteworthy (when it occurs at the end of the line, its vertical stroke is slightly elevated and its curved stroke very small, positioned above the bilinear space).

The new sections of text are marked with initials, which are often enlarged and written in ekthesis. The initials are always accompanied by paragraph marks, usually shaped as simple angular coronides (>).Footnote 15 Smaller textual units within paragraphs are separated from each other by means of middle dots. The middle dot also occurs on the last line of a paragraph, followed by a blank space. In one instance (at the end of verse 15.20), the middle dot is followed by a long horizontal stroke. The coronis, signalling the beginning of the following paragraph, is zeta-shaped, its lower branch growing into an ornament, with four spirals of identical size.

In at least six instances (ⲓⲙⲓ̇ at 1 Cor 2.14, ϣⲱⲡⲓ̇ at 1 Cor 7.12 and 15.21, ⲛⲁⲃⲓ̇ at 1 Cor 15.17, ⲛⲓⲃⲓ̇ at 1 Cor 15.19 and 15.28), the scribe placed a dot above the letter ⲓ. It is noteworthy that, in all these instances, the dotted ⲓ is word-final and preceded by a consonant; this phenomenon is also attested in P.Mich.inv. 158 (9) + P.MorganLib. 264. The function of the dot is obscure.

The supralinear stroke is tilde-shaped and used only to signal abbreviations – i.e. the nomina sacra (ⲫ︦ϯ︦, ‘God’; ⲡϭ︦ⲥ︦, ‘the Lord’; ⲡⲉⲡⲛ︦ⲁ, ‘the Spirit’; ⲡⲭⲣ︦ⲥ, ‘Christ’; ⲓⲏ︦ⲥ, ‘Jesus’) and numbers (ⲅ︦, ‘three’; ⲓ︦ⲃ︦, ‘twelve’; ⲫ︦, ‘500’) – and to represent line-final ⲛ (e.g. ⲁ⳯ for ⲁⲛ in verse 15.21).

3. History of Research

The first to study P.MorganLib. 265 was Henri Hyvernat, the scholar responsible for the production of the facsimile edition of the Morgan codices, comprising fifty-six volumes. In the ‘index tabularum’ of vol. xxxviii (comprising M.585), Hyvernat mistakenly wrote that each of the two paste-downs was made up of two fragments, somewhat imprecisely identifying their contents (e.g. saying that fr. (b) comprised 1 Cor 15.4–31 – this mistake was later repeated by Depuydt). After the publication of the facsimile, Hyvernat must have occasionally revisited the manuscript, as his copy of vol. xxxviii housed at the Catholic University of America in Washington, dc contains numerous marks witnessing his attempts to trace the faded letters, identify the biblical verses and restore some of the lacunae. An entry on M.585 in his unpublished Catalogue of the Coptic Manuscripts in the Pierpont Morgan Library Footnote 16 includes a note on the ‘fly leaves’ (i.e. paste-downs),Footnote 17 which, however, merely repeats what Hyvernat had written in the ‘index tabularum’.

Although only thirteen copies of Hyvernat's facsimile were made and although the photographs of P.MorganLib. 265 printed therein were taken before the paste-downs were dismantled (meaning that portions of text were inaccessible to the reader), this publication still allowed Coptologists to make use of the manuscript. Thus, the text of P.MorganLib. 265 is occasionally referenced in W. E. Crum's Coptic Dictionary. Unfortunately, Crum's references to P.MorganLib. 265 are often indistinguishable from his references to codex C, both of which he designates with the siglum ‘F’ (i.e. ‘Fayyūmic & related dialects’) – even though the language of the latter manuscript is better defined as ‘unevenly Fayyūmicised Crypto-Sahidic’Footnote 18 – and which happens to also contain 1 Cor 7.16–30 and 15.3–30.Footnote 19 That is, Crum never specifies when a passage derives from codex C and only occasionally marks his references to P.MorganLib. 265 with ‘Mor 38’. Thus, in his entry for ‘circumcise’, the stative ⲥⲉⲃⲏⲟⲩⲧ and the construction ⲁⲓ ⲛⲁⲧⲥⲏⲃⲃⲓ (‘be uncircumcised’), which both come from codex C, are marked ‘1 Cor 7.18 F’.Footnote 20 On the other hand, in his entry for ‘have pity, mercy’, the source of ϫⲓ ⲙⲡⲛⲉⲉⲓ (‘get pity, take alms’) – marked ‘1 Cor 15.19 F’ – is P.MorganLib. 265.Footnote 21 The importance of P.MorganLib. 265 for Fayyūmic lexicography is further discussed in the following section (see pp. 14–15 below).

Later, P.MorganLib. 265 was briefly mentioned by Theodore C. Petersen in his unpublished monograph on Coptic bookbindings (written between 1929 and 1950) and by Paul E. Kahle in an appendix on the relationship between the Fayyūmic (fa) and the Bohairic (bo) version of the New Testament.Footnote 22 Finally, Depuydt wrote an entry on this manuscript in his catalogue, which, although quite short, needs several corrections. For example, while he rightly observes that there are five fragments (rather than four), he fails to identify the contents of fr. (e) or notice that frs. (d) and (e) join together. The description of P.MorganLib. 265 provided in this article thus supersedes that by Depuydt.

4. Language

The consistent lambdacism of P.MorganLib. 265 – i.e. the substitution of /r/ with /l/ (e.g. ⲗⲱⲙⲓ, ‘human’, for S ⲣⲱⲙⲉ, B ⲣⲱⲙⲓ) – immediately informs the reader that the manuscript is written in a Fayyūmic dialect. The two major varieties of Fayyūmic Coptic are F4 (Early Fayyūmic) and F5 (Classical Fayyūmic).Footnote 23 Although the dividing line between the two dialects is not as clear as we might wish it to be (i.e. F5 manuscripts often exhibit features characteristic of F4), the distinction still seems to be worth retaining. Wolf-Peter Funk has formulated several criteria for distinguishing between F4 and F5,Footnote 24 according to which P.MorganLib. 265 should be classified as a witness to the latter dialect:

– The stem-final stressed front vowel of a word in prepersonal state, which in Sahidic and Bohairic is represented by ⲁ, is represented by ⲉ in F4 and by ⲏ in F5. In accordance with the F5 standard, P.MorganLib. 265 always reads ⲛⲏ⸗ (‘to, for’; SB ⲛⲁ⸗, F4 ⲛⲉ⸗) and ⲛⲉⲙⲏ⸗ (‘with’; S ⲛⲙ̄ⲙⲁ⸗, B ⲛⲉⲙⲁ⸗, F4 ⲛⲉⲙⲉ⸗). This rule can be found also in operation in the verb ⲙⲉϣⲏ⸗ (‘not to know’), which at verse 7.17 occurs as part of the conjunction ⲉⲙⲉϣⲏⲓ (‘except’).

– F5 signals the presence of a glottal stop /ʔ/ after a stressed vowel by doubling the vowel graphemeFootnote 25 – unlike F4, which does not have any graphic expression for the glottal stop. P.MorganLib. 265 follows the F5 standard in reading, e.g. ⲙⲉⲉⲓ (‘truth’; F4 ⲙⲉⲓ), ⲙⲁⲁϣⲓ (‘to walk’; F4 ⲙⲁϣⲓ), ⲛⲉⲉⲓ (‘to have mercy’; F4 ⲛⲉⲓ), ⲡⲓϭⲉⲉⲓ (‘vanity’; F4 ⲡⲓϭⲉⲓ), ϣⲁⲁⲡ (stative form of ϣⲱⲡⲓ, ‘to be’; F4 ϣⲁⲡ) and ϩⲱⲱ⸗ (‘self’; F4 ϩⲱ⸗). There are, however, also words spelled without vowel gemination whose form thus coincides with that in F4 – viz. ⲕⲉ⸗ (prepersonal form of ⲕⲱ, ‘to put’; cf. ⲕⲉⲥ, ‘in order that’), ⲙⲏⲟⲩⲓ (‘to think’), ⲟⲩⲉⲃ (‘holy’), ⲟⲩⲉⲓ (‘one’) and ⲟⲩⲁⲉⲧ⸗ (‘self’). It is worth noting, however, that, although other F5 manuscripts often geminate the stressed vowel in these words (thus ⲕⲉⲉ⸗, ⲙⲏⲏⲟⲩⲓ, ⲟⲩⲉⲉⲃ, ⲟⲩⲉⲉⲓ, and ⲟⲩⲁⲉⲉⲧ⸗), the F5 corpus is by no means uniform in this respect. As Funk notes, manuscripts that regularly employ forms like ⲛⲏ⸗ and ⲛⲉⲙⲏ⸗ yet exhibit certain inconsistency with regard to vowel gemination should still be classified as witnesses to F5.Footnote 26

– In F4, the indefinite pronoun used in negative contexts is ⲗⲁⲡϯ, while F5 either uses ⲗⲁⲡⲥ or oscillates between ⲗⲁⲡⲥ and ⲗⲁⲡϯ. In accordance with the F5 standard, P.MorganLib. 265 consistently employs ⲗⲁⲡⲥ.

– For the relative perfect, F4 usually employs ⲉⲧⲁ-, ⲉⲧⲁ⸗, while, in the F5 corpus, we predominantly encounter ⲛⲧⲁ-, ⲛⲧⲁ⸗. P.MorganLib. 265 always employs ⲛⲧⲁ-, ⲛⲧⲁ⸗, except for the hitherto unattested form ⲉⲧⲁⲁ⸗, which appears to be reserved for instances where the relative perfect occurs in the ‘glose’ of a cleft sentence (see the discussion below).

– In F4, the definite plural article is usually ⲛⲓ-; in F5, ⲛⲉ-. In P.MorganLib. 265, the form ⲛⲉ- occurs only twice (1 Cor 15.3, 4), both times in the expression ⲕⲁⲧⲁ ⲛⲉⲅⲣⲁⲫⲏ (‘according to the scriptures’). In all other instances, the manuscript has ⲛⲓ-. Just like the occasional absence of vowel gemination, this preference for ⲛⲓ- should probably be interpreted in the light of the fact that the transition from the ‘early’ norm of Fayyūmic (F4) to the ‘classical’ one (F5) is likely to have been a long and gradual process.

In sum, despite some notable departures from what can reasonably be conceived of as the dialectal norm, the dialect of P.MorganLib. 265 is undoubtedly F5.

In what follows, I briefly discuss the orthographic and morphological features of the manuscript, its treatment of Greek loanwords and, finally, its significance for Coptic lexicography.

Overall, the orthography of P.MorganLib. 265 is quite consistent and compliant with what seems to be the standard Fayyūmic scribal practice – for example, the grapheme <i/y> is always represented by ⲓ. There are, however, several orthographic features that are worthy of note.

– The definite singular article ⲡ-, ⲧ- usually has the long form (viz. ⲡⲉ-, ⲧⲉ-) if the determined noun begins with two consonants – hence ⲡⲉϩⲙⲁⲧ (‘the grace’) and ⲡⲉⲕⲗⲱⲙ (‘the fire’). The nomen sacrum ⲡⲉⲡⲛ︦ⲁ (‘the Spirit’) is similarly written with the long article. Yet the long form is never employed with the nomen sacrum ⲡⲭⲣ︦ⲥ (‘Christ’). This latter spelling, which in the F5 corpus competes with ⲡⲉⲭⲣ︦ⲥ, is most certainly a reflection of the Bohairic practice, just like the abbreviations ⲫ︦ϯ︦ for B ⲫⲛⲟⲩϯ, ‘God’, and ⲡϭ︦ⲥ︦ for B *ⲡϭⲱⲓⲥ, ‘the Lord’ (F5 does not have consonant aspiration and thus the ‘proper’ F5 forms of these words would be ⲡⲛⲟⲩϯ and ⲡϫⲁⲓⲥ).Footnote 27

– The scribe often doubles the letter ⲛ when it is morphemic (serving as the linkage marker, direct object marker, negative scope definer etc.) and precedes vocalic onsets – e.g. ⲛⲧϩⲏ ⲛⲛⲟⲩⲉⲓ (‘like someone’) in verse 7.25. Sometimes, morphemic ⲛ is not doubled – e.g. ⲛⲧϩⲏ ⲛⲟⲩϩⲟⲩϩⲏ (‘like an untimely birth’) in verse 15.8. Non-morphemic ⲛ, on the other hand, is never doubled – e.g. ϩⲓⲧⲉⲛ ⲟⲩⲗⲱⲙⲓ (‘through a man’) at 1 Cor 15.21 and ϩⲛ ⲁⲇⲁⲙ (‘in Adam’) at 1 Cor 15.22.

– The scribe omits the non-morphemic initial syllabic nasal in the first-person singular form of the conjunctive, writing ⲧⲁ- rather than ⲛⲧⲁ- (1 Cor 7.25). In the F5 corpus, ⲛ is similarly omitted in codex MICH.AX (comprising the Investiture of Michael (cc 0488)), where ⲧⲁ- occurs eleven times,Footnote 28 ⲛⲧⲁ- only once.Footnote 29 In the F4 corpus, this omission is attested in P.Lond.Copt. 1.504 (comprising John 3.5–4.49), where ⲧⲁ- occurs twice,Footnote 30 ⲛⲧⲁ- five times.Footnote 31 On the other hand, the scribe of P.MorganLib. 265 does not omit the initial ⲛ in the first-person plural form of the conjunctive, writing ⲛⲧⲉⲛ̣- rather than ⲧⲉⲛ- (1 Cor 2.12). The latter spelling occurs in three manuscripts in the F5 corpus – viz. MICH.AX, codex B and the still unpublished papyrus codex comprising the Martyrdom of Paphnutius (cc 0294) and the Life of Onnuphrius (cc 0254).Footnote 32

– In the expression ⲙⲙⲛ ϣϭⲁⲙ ⲙⲙⲁ⸗ (‘to be unable’), the initial syllabic nasal of the preposition ⲙⲙⲁ⸗ is omitted, resulting in the spellings ⲙⲙⲛ ϣϭⲁⲙⲙⲁϥ (‘he is unable’) at 1 Cor 2.14 and ⲙⲙⲛ ϣϭ̣ⲁⲙⲙⲁⲧⲉⲛ (‘you [pl.] are unable’) at 1 Cor 3.2. However, in the one instance where this expression is used with the affirmative existential – viz. ⲟⲩⲁⲛ ϣϭⲁⲙ̣ ⲙⲙⲁⲕ (‘you [sg.] are able’) in verse 7.21 – the nasal is not omitted. Similarly, the negative existential is usually ⲙⲙⲛ (1 Cor 2.14; 3.2; 15.13) but is at least once spelled with the initial syllabic nasal omitted – viz. ⲙⲛ (1 Cor 3.11).Footnote 33 The initial syllabic nasal is also omitted in the only occurrence of the phonologically reduced form of the possessive predicate ⲙⲙⲛⲧⲉ-, ⲙⲙⲛⲧⲏ⸗ (derived from the negative existential ⲙⲙⲛ and the preposition ⲛⲧⲉ-, ⲛⲧⲏ⸗) – viz. ⲙⲛϯ (‘I do not have’), in verse 7.25.

– The modal auxiliary of the conditional can be spelled either with or without the nasal sonorant – viz. ϣⲁⲛ and ϣⲁ. The former spelling – which is the norm in F5 Footnote 34 – occurs in all five instances when the modal auxiliary is preceded by the pronominal subject (1 Cor 7.28 (bis); 15.24 (bis), 27). In the two instances where the subject is nominal – viz.,1 Cor 3.4 and 15.28 – the morpheme is spelled ϣⲁ.Footnote 35 This pattern (ϣⲁ before nouns, ϣⲁⲛ before pronouns) seems to be the same in P.Mich.inv. 158 (9) + P.MorganLib. 264.

– The form ⲥⲏⲃⲃⲓ (‘to circumcise’; S ⲥⲃ̄ⲃⲉ, B ⲥⲉⲃⲓ) and its cognates – viz. the construct form ⲥⲏⲃⲃⲏⲧ⸗ and the stative form ⲥⲏⲃ̣ⲃⲏⲟⲩⲧ – deserve a special comment. This form also occurs in another F5 manuscript extracted from the covers of a Phantoou codex – viz. P.MorganLib. 267 (unpublished). However, yet another F5 manuscript – viz. P.Mich.inv. 158 (9) + P.MorganLib. 264 – always reads ⲥⲩⲃⲃⲓ, ⲥⲩⲃⲃⲏ-. These latter forms attest to the Fayyūmic scribal practice also reflected in ⲧⲩⲃⲧ (‘fish’) and ϣⲩⲃϣⲓ (‘shield’) – namely, to represent the reduced vowel (i.e. schwa /ə/) with ⲩ in a closed stressed syllable, with /v/Footnote 36 as its coda.Footnote 37 P.MorganLib. 265 and 267 thus bear witness to an alternative practice, in which the schwa followed by /v/ in a closed stressed syllable is represented by ⲏ. It is tempting to surmise that this difference in spelling – viz. ⲥⲏⲃⲃⲓ (P.MorganLib. 265 and 267) vs ⲥⲩⲃⲃⲓ (P.Mich.inv. 158 (9) + P.MorganLib. 264) – indicates that different Fayyūmic scriptoria maintained different scribal habits.Footnote 38

– With regard to the schwa followed by a tautosyllabic ϩ, the scribes of the F5 manuscripts had three strategies: sometimes, the schwa is represented by ⲁ (e.g. ⲧⲱⲃⲁϩ, ‘to entreat’), sometimes it has no graphic representation (ⲧⲱⲃϩ); in late manuscripts, the schwa is occasionally represented with a supralinear stroke (ⲧⲱⲃϩ̄). The scribe of P.MorganLib. 265 seems to be consistent in opting for the second approach, writing ⲗⲱⲕϩ (‘to burn’) at 1 Cor 3.15 and ⲱⲛϩ (‘to live’/‘life’) at 1 Cor 15.19, 22.

– At 1 Cor 15.9, the preposition whose usual spelling is ⲟⲩⲧⲉ- is spelled ⲟⲩⲇⲉ-. In the F5 corpus, this spelling likewise occurs in P.Mich.inv. 158 (9) + P.MorganLib. 264 (at Rom 2.15, although at Eph 3.8 this manuscript also has ⲟⲩⲧⲉ-). The form ⲟⲩⲇⲉ- is also found in codex C (at 1 Cor 15.9), in Sahidic manuscripts (including those produced in the Fayyūm)Footnote 39 and some of the first-millennium B5 manuscripts.Footnote 40 This spelling could perhaps be explained by the scribe drawing an analogy with the Greek loan words ⲟⲩⲧⲉ (οὔτɛ) and ⲟⲩⲇⲉ (οὐδέ), which were often confused with each other due to the lack of contrast between voiced /d/ and voiceless /t/ in Coptic.

– The word ⲙⲛⲥⲟⲥ (‘then’) occurs twice in the manuscript (1 Cor 15.6, 7), in both cases spelled with omicron. In the F5 corpus, the prepersonal form of ⲙ(ⲉ)ⲛ(ⲛⲉ)ⲥⲁ- may be spelled differently (viz. ⲙⲛⲛⲥⲱ⸗, ⲙⲛⲛⲉⲥⲱ⸗, ⲙⲉⲛⲛⲥⲱ⸗, ⲙⲉⲛⲥⲱ⸗), but always with omega. It is worth noting, however, that the form ⲙⲛⲛⲥⲟ⸗ occurs in codex C,Footnote 41 as well as in a number of Sahidic manuscripts produced in the Fayyūm – e.g. MICH.AL (= P.MorganLib. 51),Footnote 42 MICH.AZ (= P.MorganLib. 116)Footnote 43 and MICH.BF (= P.MorganLib. 173 + 417).Footnote 44

Of the morphological features of P.MorganLib. 265, the most remarkable is the relative perfect form ⲉⲧⲁⲁ⸗, which occurs twice in the extant text (1 Cor 2.12, 16). In the history of Coptic linguistics, the reasons behind the occasional doubling of the letter ⲁ in the F5 perfect conjugation base have been a matter of debate. While Ludwig Stern considered the pattern ⲁⲁ⸗ϥ-ⲥⲱⲧⲉⲙ to be a mere variant of the first perfect (ⲁ⸗ϥ-ⲥⲱⲧⲉⲙ), H. J. Polotsky argued that ⲁⲁ⸗ϥ-ⲥⲱⲧⲉⲙ is, in fact, a special form of the second perfect, an interpretation later endorsed by Walter C. Till and Georg Steindorff.Footnote 45 However, as Funk noted in 1995, this interpretation does not take into account those instances in the F5 corpus where the doubled ⲁ occurs in relative perfect.Footnote 46 This Gordian knot was severed in the latest instalment of Funk's F5 concordance, where two homonymous morphemes are distinguished, one occurring in the second perfect,Footnote 47 the other in the relative perfect.Footnote 48 P.MorganLib. 265 is thus an important new witness of the second morpheme. Its importance lies in the fact that, in this manuscript, the relative form occurs for the first time with the spelling ⲉⲧⲁⲁ⸗ (rather than ⲛⲧⲁⲁ⸗). Moreover, P.MorganLib. 265 is the only known F5 manuscript where the relative perfect with the doubled ⲁ appears in the ‘glose’ of a cleft sentence. In fact, it seems that, in all other contexts, P.MorganLib. 265 employs the form ⲛⲧⲁ-, ⲛⲧⲁ⸗, which may indicate that, in this manuscript, the form ⲉⲧⲁⲁ⸗ was reserved exclusively for cleft sentences.

The following two morphological features of P.MorganLib. 265 are also worth mentioning:

− The manuscript uses two sets of definite articles – viz. ⲡ(ⲉ)-, ⲧ(ⲉ)-, ⲛⲉ- and ⲡⲓ-, ϯ-, ⲛⲓ-. As I have already noted, in the plural the definite article is predominantly ⲛⲓ-, while ⲛⲉ- occurs only twice, and only in the expression ⲕⲁⲧⲁ ⲛⲉⲅⲣⲁⲫⲏ (‘according to the scriptures’). In the singular, the situation is reversed: the text normally employs ⲡ(ⲉ)- and ⲧ(ⲉ)-, while ⲡⲓ- occurs only five times (1 Cor 2.14; 7.16, 22 (bis); 15.5) and ϯ- only once (1 Cor 7.28). As far as I can tell, the use of one of the two sets of articles is not conditioned syntactically, nor is there any discernible difference in meaning between them.Footnote 49

− The manuscript also attests to two competing forms for causative infinitive – viz. ⲧⲣⲉ-, ⲧⲣⲉ⸗ and ⲧⲉ-, ⲧⲉ⸗. The pattern ⲧⲣⲉ-, ⲧⲣⲉ⸗ occurs six times: twice in the purpose clause construction ⲉ-ⲧⲣⲉ- (1 Cor 7.26; 15.9), twice in the negative causative imperative ⲙⲡⲉⲗⲧⲣⲉ- (1 Cor 3.18; 7.18) and twice conjugated (1 Cor 3.6, 7). The pattern ⲧⲉ-, ⲧⲉ⸗ occurs only once, in the negative causative imperative ⲙⲡⲉⲗⲧⲉ- (1 Cor 7.21). This datum seems to support Funk's observation that, in F5, the pattern ⲧⲉ-, ⲧⲉ⸗ was out-competed by ⲧⲣⲉ-, ⲧⲣⲉ⸗ and that, as a rule, its use was restricted to the definite purpose clause ⲉ-ⲡ-ⲧⲉ- and the negative causative imperative ⲙⲡⲉⲗⲧⲉ-.Footnote 50

The treatment of Greek loanwords in P.MorganLib. 265 reflects the standard practices of the Fayyūmic scriptoria: that is, our scribe is consistent in representing all Greek epsilon–iota sequences with ⲓ (e.g. ⲓⲧⲉ for ɛἴτɛ) and all alpha–iota sequences with ⲉ (e.g. ⲙⲉⲗⲉⲥⲑⲉ for μέλɛσθαι). Similarly, Greek verbs always occur in the infinitive and are always derived by means of the light verb ⲉⲗ- (e.g. ⲉⲗⲇⲟⲕⲓⲙⲁⲍⲓⲛ). The following features of the manuscript are worthy of note:

– Although the scribe of P.MorganLib. 265 often misspells Greek words – replacing ω with ⲟ (e.g. ⲅⲛⲟⲙⲏ for γνώμη), ο with ⲱ (e.g. ⲱⲧⲓ for ὅτι), τ with ⲇ (e.g. ⲁⲣⲭⲓⲇⲉⲕⲧⲟⲛ for ἀρχιτέκτων) etc. – he never uses the monogram ϯ for the tau–iota sequences in Greek loanwords (hence ⲉⲧⲓ, ⲡⲓⲥⲧⲓⲥ, ⲡⲛ︦ⲁⲧⲓⲕⲟⲥ, ⲱⲧⲓ).

– The verb ὑποτάσσɛσθαι (‘to be subject’), which occurs in P.MorganLib. 265 six times, is remarkable with respect to its spelling. As Funk observes, in Bohairic and Fayyūmic, Greek verbs ending with -τάσσɛιν and -τάσσɛσθαι would normally be spelled -ⲧⲁⲍⲓⲛ or -ⲧⲁⲍⲉⲥⲑⲉ.Footnote 51 This observation is confirmed by P.MorganLib. 265, where, five out of six times, the verb is spelled ϩⲏⲡⲟⲧⲁⲍⲉⲥⲑⲉ, yet once it is spelled ϩⲏⲡⲟⲧⲁⲥⲉⲥⲑⲉ, which indicates that the scribe had difficulty distinguishing voiced /z/ from voiceless /s/. It is worth noting, however, that at least one manuscript that can be considered for inclusion into the F5 corpus – viz. P.MorganLib. 268 – goes against this tendency, reading ϩⲩⲡⲟⲧⲁⲥⲥⲉⲥⲑⲉ (at 1 Cor 14.32, 34). However, given that the orthography of P.MorganLib. 268 is often at odds with the F5 standard – for example, in this manuscript, the full (stressed) form of the possessive predicate is ⲟⲩⲁⲛⲧ⸗ (rather than ⲟⲩⲁⲛⲧⲏ⸗) – the form ϩⲩⲡⲟⲧⲁⲥⲥⲉⲥⲑⲉ should probably be explained by the scribe’s insufficient acquaintance with the orthographic norm.Footnote 52

– Another medio-passive infinitive that occurs in P.MorganLib. 265 is μέλɛσθαι (‘to be an object of care’). In the Greek text of the New Testament, the verb μέλɛιν occurs only in the active voice. It is, therefore, rather remarkable that, at 1 Cor 7.21, P.MorganLib. 265 employs the medio-passive form; a similar ‘predilection for the longer form’ was recently detected by Funk in the ‘Curzon Catena’ (P.Lond.Copt. 2.249), one of the key witnesses to the medieval Bohairic (dialect B5) of the first millennium.Footnote 53 Interestingly, in the Bohairic New Testament (bo), the active voice of the Greek original is also occasionally rendered with ⲙⲉⲗⲉⲥⲑⲉ – see e.g. Acts 18.17 – but not at 1 Cor 7.21, where all the witnesses use the active form.

– The word ⲯⲩⲭⲏⲕⲟⲥ, which occurs in P.MorganLib. 265 at 1 Cor 2.14, also occurs in one other manuscript of the F5 corpus – viz. P.Vindob. K 3280 + K 3921 + K 9311 – where it is similarly spelled with ⲏ. It is tempting to suggest that ⲯⲩⲭⲏⲕⲟⲥ was the standard F5 spelling of ψυχικός (rather than a mere case of iotacism). This suggestion receives support from the fact that, in the F5 corpus, some of the words formed with the prefix ἀρχ- are similarly spelled with ⲏFootnote 54 – viz. ⲁⲣⲭⲏⲁⲅⲅⲉⲗⲟⲥ (in National Library of France, Copte 1631 fol. 1 (comprising an otherwise unknown martyrdom) and MICH.AX),Footnote 55 ⲁⲣⲭⲏⲉⲡⲓⲥⲕⲟⲡⲟⲥ (in P.Carlsberg 300, comprising De incredulitate (cc 0013) and De providentia (cc 0012), both attributed to the fictitious Agathonicus of Tarsus),Footnote 56 ⲁⲣⲭⲏⲡⲗⲁⲥⲙⲁ (in MICH.AX)Footnote 57 and ⲁⲣⲭⲏⲥⲧⲣⲁⲇⲓⲕⲟⲥ (in MICH.AX).Footnote 58

– The F5 corpus is divided on the pluralisation of the noun ἐντολή. Two manuscripts – viz. codex B (at John 14.21)Footnote 59 and P.Mich.inv. 158 (9) + P.MorganLib. 264 (at Rom 13.9) – employ the singular form (ⲉⲛⲧⲟⲗⲏ), specifying the number of the noun only by means of the article. Two other manuscripts – viz. P.Carlsberg 300 and Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, i.1.б.637 – also add the plural marker -ⲟⲩ.Footnote 60 P.MorganLib. 265, which uses the form ⲉⲛⲧⲟⲗⲏⲟⲩ (at 1 Cor 7.19), belongs to the second group.Footnote 61

– The F5 corpus is also divided on the spelling of the conjunction ἵνα. Some manuscripts always read ϩⲓⲛⲁ (e.g. codex B and National Library of France, Copte 1631 fol. 1), others always ϩⲓⲛⲁⲛ (e.g. P.MorganLib. 259 and 261).Footnote 62 P.MorganLib. 265 seems to belong in the former group. It is worth noting, however, that, in both instances where ϩⲓⲛⲁ occurs in this manuscript (viz. 1 Cor 2.12; 15.28), it is followed by the initial ⲛ of the conjunctive. It is thus possible that the form ϩⲓⲛⲁ in these two cases is due to ‘phonetic’ haplographyFootnote 63 and that, elsewhere in the manuscript, the word was spelled ϩⲓⲛⲁⲛ. In fact, there are at least two manuscripts in the F5 corpus (viz. codex A and P.Mich.inv. 158 (9) + P.MorganLib. 264) that usually use ϩⲓⲛⲁⲛ but occasionally have ϩⲓⲛⲁ – albeit always before the conjunctive.Footnote 64

– Another Greek loanword that perhaps deserves to be mentioned here is the personal name Ἰάκωβος (‘James’), which, in P.MorganLib. 265, is spelled with the kappa doubled – viz. ⲓⲁⲕⲕⲟⲃⲟⲥ (1 Cor 15.7). A case can be made that this was, in fact, the standard spelling of the name in F5. Apart from P.MorganLib. 265, the form with the doubled kappa occurs in at least four manuscripts: P.Vindob. K 10113 (at Mark 16.1: ⲓⲁⲕ̣ⲕⲱⲃ[ⲟⲥ]),Footnote 65 codex B (at Matt 13.55: ⲓⲁⲕⲕⲱⲃⲟⲥ),Footnote 66 P.Carlsberg 300 (fol. 7a, ll. 8–9: ⲓⲁⲕⲕⲱⲃⲟⲥ)Footnote 67 and MICH.AX (ⲓⲁⲕⲕⲟⲃⲟⲥ).Footnote 68

Finally, P.MorganLib. 265 provides scholars of the Coptic language with valuable lexicographic data. In a number of cases, this manuscript attests to the use of a lexeme or a form thereof otherwise unattested in the F5 corpus. Fortunately, though the manuscript itself has been hitherto unpublished, most of these forms were registered in Crum's dictionary, who consulted P.MorganLib. 265 via Hyvernat's facsimile – viz. ⲁⲛⲁ- (phonologically reduced form of ⲱⲛⲓ, ‘stone’, occurring in the compound ⲁⲛⲁⲙⲙⲉⲉⲓ, ‘precious stone’),Footnote 69 ⲁⲣⲱϯ (‘milk’),Footnote 70 ⲕⲁⲁⲛⲥ⸗ (‘to be buried’, prepersonal form of the verb whose absolute form is unattested),Footnote 71 ⲥⲁⲁϥ- (prenominal form of the verb ⲥⲱ(ⲱ)ϥ, ‘to defile’),Footnote 72 ⲟⲩⲁⲁⲓⲉ (‘farmer’, occurring in the compound ⲓⲉⲡⲟⲩⲁⲁⲓⲉ, ‘tillage’)Footnote 73 and ϩⲟⲩϩⲏ (‘untimely birth’).Footnote 74 Two otherwise unattested forms were unknown to Crum – viz. ⲥⲏⲃ̣ⲃⲏⲟⲩⲧ (stative of ⲥⲏⲃⲃⲓ, ‘to circumcise’) and ⲥⲏⲃⲃⲏⲧ⸗ (prepersonal form of the same verb). P.MorganLib. 265 also bears witness to several forms that are rather poorly attested in the F5 corpus – for example, ⲁⲗⲓⲗⲓ (absolute form of the imperative of the verb ⲓⲗⲓ, ‘to do’; not registered in Crum's dictionary) otherwise occurs only once, in P.Vindob. K 3280 + K 3921 + K 9311 (at 1 Cor 16.1); ⲕⲉⲉⲛⲓ (‘thing’) only once, in P.Mich.inv. 158 (9) + P.MorganLib. 264 (at Rom 14.2);Footnote 75 and ⲗⲁⲩⲓ (‘straw’) only once, in codex A (at Isa 5.24: ⲗⲁⲟⲩⲓ).

While Crum's inventory of forms attested in P.MorganLib. 265 is more or less complete, the data provided by P.MorganLib. 265 can still be used to supplement existing dictionaries and grammars with regard to the use of several words and constructions in F5. For example, P.MorganLib. 265 has two instances of the preverbal modifier ⲉⲗⲡⲕⲉ-, ‘also’ (1 Cor 15.15, 29), for which Crum provides only Sahidic and Bohairic attestations.Footnote 76

It is also worth noting that, in one instance, P.MorganLib. 265 leaves Coptic lexicographers disappointed. At 1 Cor 7.29, bo reads ⲡⲥⲏⲟⲩ ⲙⲡⲱⲣϥ ⲡⲉ (‘it is the time of withdrawal’), and there can be little doubt that the phrasing of fa was similar (with F5 ⲟⲩⲁⲓϣ corresponding to B5 ⲥⲏⲟⲩ). Unfortunately, the letters following ⲱ̣ are lost in the lacuna, and thus we cannot know whether B5 ⲱⲣϥ was subject to lambdacism in F5.Footnote 77

5. Provenance and Date

Since P.MorganLib. 265 is written in F5, a dialect of the Fayyūm, and since it was extracted from the covers of a manuscript which belonged to a monastery in the Fayyūm, we can be fairly certain that P.MorganLib. 265 was copied in the Fayyūm. Nevertheless, it seems impossible to ascertain where exactly in the Fayyūm it was produced. According to Petersen, the binding of MICH.BM (from which P.MorganLib. 265 was extracted) ‘very clearly’ comes from the same bindery as those of MICH.AB, MICH.AR and MICH.AU.Footnote 78 Since, according to their colophons, these three codices were donated to the Monastery of the Archangel Michael, it is not impossible that this monastery was also where the codices were copied and bound. However, this hypothesis is made problematic by the fact that MICH.AR seems to have been originally donated to a place different from the Monastery of the Archangel Michael.Footnote 79 On the other hand, since one of the scribes of MICH.AB – viz. Isaac – resided in Ptepouhar,Footnote 80 we might surmise that the binding of MICH.AB (along with those of MICH.AR, MICH.AU and MICH.BM) was produced there, too. Unfortunately, however, even if this surmise should be correct, we would still not know whether the scriptorium where P.MorganLib. 265 was produced and the bindery where it was later reused were situated in the same place.

The terminus a quo for P.MorganLib. 265 is provided by its dialect. According to Funk, the manuscripts of the F4 corpus were copied between the fourth and sixth centuries ce, while the witnesses to F5 were produced from the sixth century until the turn of the millennium.Footnote 81 The terminus ante quem is provided by the date of the binding of MICH.BM. According to the colophons of MICH.AB and MICH.AU,Footnote 82 these manuscripts were donated to the Monastery of the Archangel Michael in the year 609 of the era of Diocletian (= 892/3 ce). Since, as Petersen observes, the date of the bindings of these two codices and MICH.BM is ‘approximately the same’,Footnote 83 we can be certain that P.MorganLib. 265 was produced before 893 ce.

Within this date range, an earlier date (sixth or seventh century) seems more plausible than a later one. According to Kahle, P.MorganLib. 265 was produced ‘not later than the seventh century’.Footnote 84 Kahle's proposal receives support from the fact that the hand of P.MorganLib. 265 is similar to that of P.Vindob. K 8691, two parchment strips in dialect F4 that partially preserve 1 Pet 2.11–13, 20–3 and Jas 1.21–6.Footnote 85 A documentary text in Middle Persian was written over the Fayyūmic,Footnote 86 which provides a secure terminus ante quem for P.Vindob. K 8691 – viz. 629 ce (end of the Sasanian occupation of Egypt).Footnote 87

Moreover, the paragraph mark signalling the beginning of 1 Cor 15.21 in P.MorganLib. 265 can be compared to those of the three Sahidic codices from the Monastery of Jeremias at Saqqara, housed at the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin.Footnote 88 Thanks to the coins with which they were discovered, these manuscripts – numbered as sa 4, sa 5 and sa 6 in the SMR (Schmitz-Mink-Richter) database – can be securely dated to ca 600 ce.Footnote 89

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Anne Boud'hors, Hugh Houghton, Antti Marjanen and the anonymous reviewer of NTS for commenting on the previous drafts of this article, as well as Kenneth Lai for revising its English. I am especially grateful to Wolf-Peter Funk, who not only shared with me many of his unpublished findings but also kindly allowed me to consult the latest instalments of his concordances of the F4 and F5 corpora. Wolf-Peter's sudden passing on 18 February 2021 was an irreparable loss to Coptic dialectology.