1. Introduction

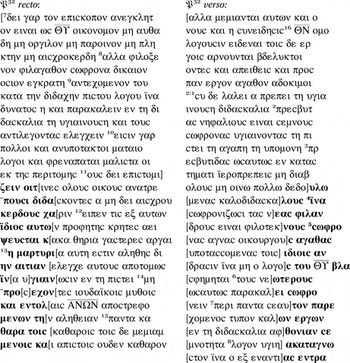

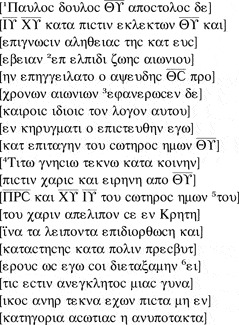

The fragmentary John Rylands papyrus of Titus (P.Ryl. Gr. 1.5), commonly known as 𝔓32, is the only surviving manuscript of this Pauline epistle prior to the mid-fourth-century Bible Codex Sinaiticus. 𝔓32 was acquired by papyrologist Arthur Hunt (the editor) between 1895 and 1907, during which time he and Bernard Grenfell jointly conducted several archaeological excavations at Oxyrhynchus and towns in the Fayûm, but its provenance is unknown.Footnote 1 Presently 𝔓32 is a relatively small fragment (c. 4.9 × 10.5 cm) from the bottom half of a single papyrus leaf, now showing only some of Titus 1.11-15 and 2.3-8. It happens that on the recto (→) side only the first 7-9 letters of 13 lines of text are preserved, while on the verso (↓) side we have the final 3-9 letters of 14 lines (some letters are partly or wholly effaced). There are inner and lower margins, c. 1.5 and 2.3 cm respectively. It is evident that, as usual for NT manuscripts, the original format of 𝔓32 was that of a codex (a ‘book’) of gathered leaves rather than a roll, for the flow of writing can be traced as running in a single column across the two ‘pages’, from the recto (‘front’) side (1.11-15) to the verso (‘back’) (2.3-8), though the intervening text is now missing due to the deterioration of the top of the leaf. Rolls were normally written only on the recto side (the horizontal fibres being preferred to the vertical fibres of the verso side), though occasionally the verso could also be used for another document. But in 𝔓32 we have the same text continuing on both sides so as to indicate two consecutive ‘pages’ of a codex leaf. Since there are no indications that 𝔓32 was excerptive or anything other than a continuous-text manuscript, it is presumed that the immediate literary context of the fragment is the remainder—the whole—of the epistle to Titus.Footnote 2

The script of 𝔓32 is upright, large, well rounded and carefully written, with some cursive formations and occasional ligature. Vertical and horizontal strokes are typically decorated with intentional ‘roundels’ (ink blobs), and obliques with ornamental curls (finials), which accentuate the generally bilinear arrangement of letters with respect to the notional upper/lower horizontal guide lines. The spacing between letters is slightly uneven, but on two occasions the gap is large enough to suggest intentional word division (between [ɛπιϲτομι]ζɛιν and οιτ[ινɛϲ], line 1 recto, and ψɛυϲται and κ[ακα], line 5 recto). Diaereses for ϊδιοϲ (line 4 recto) and ϊν[α] (line 8 recto; line 2 verso) aid reading. The purpose of the short horizontal strokes in the left hand margin at the beginning of lines 2 and 9 recto is unclear. Contraction of the nomen divinum occurs in the form θυ (line 7 verso), and available space suggests the contraction of ανθρωπων (line 10 recto). Overall, the type of presentation may be characterized as the ‘reformed documentary’ common among early NT papyri—the product of a skilled scribe who was aware of working on a literary text and aimed for, but to some extent fell short of, a professional effect. It is not possible to determine the textual character because only a relatively small amount of text remains.Footnote 3

Before attending to hypothetical reconstruction of the lost text, I reappraise the palaeographical dating of the manuscript, which is important for the ultimate question of content.

1.1. The Date of the Manuscript

Hunt palaeographically assigned 𝔓32 to the third century, briefly commenting that its ‘round and rather large uncial hand’ looks ‘decidedly early’ and belongs to about the same period as the very similar hand of P.Oxy. 656 (Genesis LXX), which he and Grenfell had assigned to the late second or early third century, though 𝔓32 ‘is perhaps the later of the two’. E. Dobschütz listed 𝔓32 as third or fourth century,Footnote 4 whilst H. I. Bell and T. C. Skeat sought to push back the date of P.Oxy. 656—and therefore 𝔓32—definitely into the second century, appealing to ‘a really striking similarity, both in the general appearance and in the forms of individual letters’, with the then newly discovered P.Lond.Christ. 1 (‘Egerton’ gospel), which they assigned to the middle of the second century using the roughly dateable P.Lond. 130 (a horoscope with introductory letter, I-II) and the documents P.Fay. 110 (94) and P.Berol. 6854 (98-117).Footnote 5 Bell and Skeat's earlier placement of 𝔓32 on this basis has been supported by C. H. Roberts, P. W. Comfort and D. Martinez, whilst K. Aland puts it at ‘um 200’, the date that has been most influential in the wider literature.Footnote 6 However, M. Gronewald reassigned P.Lond.Christ. 1 to c. 200, in light of the discovery of another fragment from the same codex, P.Köln 255, that has an oblique apostrophe between two consonants (a feature that was not common until the third century).Footnote 7 This in turn undermines confidence in the second-century datings of P.Oxy. 656 (using P.Lond.Christ. 1) and 𝔓32 (using P.Oxy. 656 and P.Lond.Christ. 1) and highlights a problem of circularity of argument arising from over-reliance on assigned dated comparanda. For the same reason, other early Christian manuscripts with which 𝔓32 has close affinities, such as 𝔓66 = P.Bodm. II (John; assigned c. 200, using P.Lond.Christ. 1), 𝔓90 = P.Oxy. 3523 (John; assigned II, using P.Oxy. 656 and P.Lond.Christ. 1), and 𝔓104 = P.Oxy. 4404 (Matthew; assigned late II, using 𝔓90), are of limited independent value for dating.

A more rigorous method for dating an undated literary manuscript such as 𝔓32 is to locate the hand within the historical context of its ‘graphic stream’ by comparison with dated (or else firmly dateable) hands that are characterized by the same stylistic elements.Footnote 8 W. Schubart understood the large, round script with decorative finials and roundels to constitute a single, normative ‘decorated style’ (Zierstil) prevalent in the period from the last century of the Ptolemaic era to about AD 100,Footnote 9 but Turner identified these features in various non-specific calligraphic scripts that persisted into the third century in documents such as P.Oxy. 3030 (c. 207), P.Oxy. 3093 (217) and P.Lund IV.13 (250–275).Footnote 10 G. Cavallo places 𝔓32 in the early third century by contextualizing it within a particular stream that appears in dated documents such as PSI V.446 (133–37), P.Fay. 87 (155/6), P.Oxy. 473 (138–61) and eventually in the fifth to sixth centuries turns into the normative style known as ‘Alexandrian Majuscule’ (or Coptic-type Uncial).Footnote 11 The broad, rounded forms of θ ɛ ϲ in 𝔓32 contrast the narrower, oval forms of the later, more fully-fledged versions found in P.Berol. 13418 (V), P.Grenf. II.112 (577), P.Oxy. 1820 (VI/VII), P.Köln 215 (VI/VII), P.Oxy. 2258 (VI/VII), P.Louvre E. 7404 (VII/VIII), P.Berol. 10677 (713/719) and P.Heid. 295 (VIII).Footnote 12 The two forms of α (looped and arched), curled δ, dish-shaped μ, (sometimes) smaller ο and looped υ are attested already in the late first-century P.Fay. 110 (94) and persist along the continuum through the second-century P.Oxy. 2968 (190) and late third-century P.Oxy. 3183 (292); D. Barker is evidently correct to describe the stream as having a strong ‘holding power’ in many of its letter formations.Footnote 13

The agreement of Hunt, Turner and Cavallo in narrowing the date of 𝔓32 to the third century is justified by attention to the dimensions of the codex (about 15 × 21 cm; see §2 below), which align it with thirteen similarly sized papyrus codices in Turner's ‘Group 7 Aberrants 1’, of which only one (P.Yale 1, Genesis) possibly predates the third century.Footnote 14 Third- and fourth-century codices predominate, including the Christian manuscripts 𝔓113 = P.Oxy. 4497 (Romans, III), 𝔓28 = P.Oxy. 1596 (John, III–IV), P.Oxy. 1172 (Shepherd of Hermas, IV) and P.Bodm. XXIII (Coptic Isaiah, IV), whilst a couple are as late as the seventh–eighth century. None of the eighteen slightly taller codices in ‘Group 7’ proper (c. 15 × 25 cm) or ‘Group 7 Aberrants 2’ predates the third century. The trend of the physical data supports the assignment of 𝔓32 to the third rather than second century.

2. Reconstructing the Beginning of the Epistle to Titus

The missing portions may be conjecturally reconstructed, by supplying the text of a modern critical edition of Titus (Nestle-Aland's 28th), adjusted to reflect the convention of nomina sacra, and by assuming reasonably consistent layout of text across each page. The reconstruction in the editio princeps aptly completed the broken parts of the twenty-seven extant lines. It is a reasonably straightforward procedure to take the additional step of supplying text for the missing top of each page, to give a fuller sense of the whole. The intervening text (1.15b–2.3a) which must have occupied the top of the verso page can be supplied according to the average number of letters per complete line (approximately 23) and average line spacing (c. 0.6 cm) in the extant parts.Footnote 15 It is found to fill a further 12 lines and suggests a column of text containing a total of 27 lines (or 622 letters), measuring c. 11 × 16 cm (breadth × height). Assuming that both pages contained approximately the same amount of text (i.e. a regular column size), the top of the recto page can then be projected by working backwards from Titus 1.11b with the slightly different averages of 27 letters per restored line and 0.65 cm line spacing,Footnote 16 to produce a column of text about 26 lines (698 letters) that begins at Titus 1.7, as follows:

This concurs with earlier estimations of E. M. Schofield, E. G. Turner, J. van Haelst, K. Aland, K. Wachtel and K. Witte, P. W. Comfort and D. P. Barrett that the size of the written area (the β measurement) was 26-27 lines or c. 12 × 16 cm, hence the overall size of the codex (the α measurement) was about 15 × 21 cm.Footnote 17 The actual division of text across the missing lines cannot be certain, and neither can our manuscript's particular readings at the known points of variation in the tradition; yet what is important is that this fuller reconstruction does provide an approximate sense of the overall shape of the text on the two pages.Footnote 18

This stage leads us to consider further the place of Titus 1.1-6 in the codex—the key contribution of this article—by extending the scope of codicological reconstruction to include the previous page. Again, the focus of interest is in determining an overall sense of the physical situation of the epistle within this page of the codex. My approach is similar to that of Skeat in his article, ‘The Oldest Manuscript of the Four Gospels?’, who identifies the Gospel fragments 𝔓4 = BnF.Suppl.Gr. 1120/2 (Luke 1.58-59; 1.62–2.1, 6-7; 3.8–4.2, 29-32, 34-35; 5.3-8; 5.30–6.16), 𝔓64 =P.Magd.Gr. 17 (Matt 26.7-8, 10, 14-15, 22-23, 31-33) and 𝔓67 =P.Barc. 1 (Matt 3.9, 15; 5.20-22, 25-28) as originating from the same codex, and seeks to determine by reconstruction and calculation the position of the end of Matthew's Gospel and the beginning of Luke (concluding that the two are incompatible and ‘another Gospel or Gospels must have intervened’ between them in the codex).Footnote 19 Skeat reconstructs the two-column codex leaf from which the three small fragments of 𝔓64 originated, and then, by analogy (assuming a consistent amount of text per leaf, spread evenly across the four columns), extrapolates forwards 10,115 letters (five leaves, nine pages, 18 columns) to find the location of the end of Matthew's Gospel ‘just before the foot of col. 2 of the fifth leaf—probably about 3 or 4 lines from the foot’, concluding that ‘The next Gospel would then have begun overleaf, viz. at the head of col. 3’.Footnote 20 Such a procedure of reconstruction and extrapolation is theoretically endorsed by P. M. Head in his response article, although Skeat's particular execution proves unconvincing in this instance for being over-precise in not allowing for a range of possible page sizes (measured in number of letters per page).Footnote 21 The same kind of approach to reconstruction is also exemplified by D. Barker, who uses the average number of letters per page to make projections for the lost beginning of the parchment codex 0206=P.Oxy. 1353 (1 Pet 5.5-13). He argues that the extant pagination (either ΩΚΘ, 829, or ΩΙΘ, 819) evidences a large codex, whose preceding pages could have contained NT epistles from Romans to 1 Peter (a total of c. 194,500 letters at an average of 250 letters per page gives about 778 pages).Footnote 22

My own reconstruction of 𝔓32 works backwards from the restored recto page to the page that preceded it, and deals not with tens or hundreds of thousands of letters, but several hundred. Assuming the scribe employed a similar amount of text on this page as on the two that followed, we would expect a total of approximately 660 letters, spread across 26 or 27 lines with an average of c. 25 letters per line. This expectation is calculated using the figures from the reconstructed recto and verso pages, i.e., 660 is the average number of letters across the two pages (622 + 698 ÷ 2), 25 is the average number of letters per line across all 27 restored lines. One finds, however, that at c. 25 letters per line the 491 letters to beginning of the epistle, Titus 1.1–6, would occupy a space of just 19 lines, as follows:

The relevance of this additional stage of reconstruction for the question of the original content of the codex lies in the marked difference between the amount of text on this page and that which we would anticipate by analogy with the two extant pages: the text of Titus would begin seven or eight lines (approximately 169 letters) short of the expected column size of 26-27 lines (660 letters), occupying only the lower part of the available writing space.

The argument that the text of Titus would not have begun at the top of the page is robust across a range of possible amounts of text per page. For instance, if we were to assume instead an average of 24 letters per line (i.e. a total of 624–648 letters per page) the text of Titus 1.1-6 would occupy approximately 20 lines and fall six or seven lines short of the top of the column. Assuming a lower average of 23 letters per line (i.e. a total of 598-621 letters per page) the text would occupy approximately 21 lines and fall five or six lines short. Assuming a still lower average of 22 letters per line (i.e. a total of 572-594 letters per page) the text would occupy approximately 22 lines and fall four or five lines short. Conversely, any increase in the average number of letters per line (and total number of letters per page) would serve to strengthen our argument. For instance, assuming an average of 27 letters per line, as in the reconstructed recto page (698 letters), the discrepancy would rise to eight or nine lines; assuming an average of 29 letters per line (i.e. a total of 754-783 letters per page), a rise to nine or ten lines. The conclusion more than allows for a normal amount of variation in page size between these three pages of the codex.

A certain proportion of the remaining writing space at the top of our reconstructed page may be accounted for by assuming the presence of an epistolary title at the head of the main text.Footnote 23 In keeping with the general convention of concise titles in the form ‘author, work, book number’, the superscriptions extant in early NT manuscripts are all relatively brief in form, namely: προϲ ɛβραιουϲ, προϲ κορινθιουϲ α, προϲ κορινθιουϲ β, προϲ ɛφɛϲιουϲ, προϲ γαλαταϲ, προϲ φιλιππηϲιουϲ, προϲ κολαϲϲαɛιϲ, προϲ θɛϲϲαλονι![]() ɛιϲ [α?] (𝔓46 =P.Ch.Beatty II+P.Mich. 6238), ɛυαγγɛλιον κατα ιωαννην (𝔓66 and 𝔓75 =P.Bodm. XIV-XV), πɛτρου ɛπιϲτολη α, πɛτρου ɛπιϲτολη β and ιοδα ɛπɛιϲτολη (𝔓72 =P.Bodm. VII-VIII). In 𝔓66 and 𝔓46 a small aesthetic space equivalent to one or two lines stands between the superscription and the first line of text, but in 𝔓72 and 𝔓75 the first line of text immediately follows that of the superscription. A comparably brief superscription in our manuscript, such as προϲ τιτον (א2 A I K Ψ 0142 0150), αρχɛται προϲ τιτον (D F G) or παυλου ɛπιϲτολη προϲ τιτον (P), would still leave a discrepancy of around five or six lines at the top of the column, room enough for a further 125-150 letters.

ɛιϲ [α?] (𝔓46 =P.Ch.Beatty II+P.Mich. 6238), ɛυαγγɛλιον κατα ιωαννην (𝔓66 and 𝔓75 =P.Bodm. XIV-XV), πɛτρου ɛπιϲτολη α, πɛτρου ɛπιϲτολη β and ιοδα ɛπɛιϲτολη (𝔓72 =P.Bodm. VII-VIII). In 𝔓66 and 𝔓46 a small aesthetic space equivalent to one or two lines stands between the superscription and the first line of text, but in 𝔓72 and 𝔓75 the first line of text immediately follows that of the superscription. A comparably brief superscription in our manuscript, such as προϲ τιτον (א2 A I K Ψ 0142 0150), αρχɛται προϲ τιτον (D F G) or παυλου ɛπιϲτολη προϲ τιτον (P), would still leave a discrepancy of around five or six lines at the top of the column, room enough for a further 125-150 letters.

Why might the scribe have positioned the beginning of Titus a fifth of the way into the column? It is difficult to imagine that s/he would deliberately have done so if there were only empty space beforehand—especially as this would be the back side of a leaf.Footnote 24 Since para-textual prefatory materials such as the Euthaliana belong to the later tradition, the most natural explanation is that Titus was not the first document on this page of the codex but followed on immediately from another. Footnote 25 The early Pauline codex 𝔓46 demonstrates that a transition from one epistle to the next could occur even at the very top of a column; folio 21 recto has just the final four words of Rom 16.23 on the first line, before commencing Hebrews.Footnote 26 My proposal, therefore, is that 𝔓32 should be understood as part of a manuscript which did not contain Titus alone but was a collection of at least two texts—a multi-text codex.

3. The Content of the Manuscript

The contention that 𝔓32 was part of a multi-text codex provokes the intriguing question of content: which text(s) accompanied Titus? Of course, the number and identity of any such text(s) can only ever be a matter of conjecture. It remains possible that in this instance Titus was grouped with some non-Pauline writing(s) in a variegated collection. A number of early Coptic and Greek-Coptic manuscripts have heterogeneous arrangements of Christian writings, including the fourth-century miniature codex P.Mich. 3992 with fragments of John, 1 Corinthians, Titus, Psalms (in that sequence) and Isaiah.Footnote 27 Perhaps these reflect the uncoordinated nature of early translation efforts.Footnote 28 The third-century Bodmer ‘Composite’ Codex (P.Bodm. V, VII-XIII, XX) also houses a surprising mix of Christian writings, with the Protoevangelium of James, 3 Corinthians, the 11th Ode of Solomon, Jude (=𝔓72), Melito's Homily on the Passover, a liturgical hymn, the Acts of Phileas, Psalms 33–34, 1 and 2 Peter (=𝔓72), but this represents exceptional practice within the unilingual Greek tradition.Footnote 29 It is reasonable to base a hypothesis for the 𝔓32 codex on what might normally have been transmitted with Titus at the time of its production. An overview of the epistle's history of reception indicates that at the turn of the third century it was regarded among the proto-orthodox as belonging to the group of Pauline scriptures, whether thirteen (in the West) or with Hebrews fourteen (in the East). This suggests that it was ordinarily being published together with texts in this same authorial (eventually: canonical) group.

In the West, Irenaeus of Lyons (writing c. 180) makes use of Titus (and the epistles to Timothy) in his promotion of a normative reading of Paul, prefacing his quotes with introductory markers that unambiguously attribute it to the apostle and so identify it with his other epistles.Footnote 30 The biographically, theologically and pastorally constructive manner in which Irenaeus deploys it shows that it already ‘fits comfortably’ within the Pauline tradition he inherited.Footnote 31 The Muratorian fragment (probably originating in the late second century) counts it among the thirteen esteemed epistles of Paul (over against Laodiceans, Alexandrians and other Marcionite forgeries which ‘in catholicam ecclesiam recepi non potest’).Footnote 32 Tertullian of Carthage (fl. c. 200–220) also utilizes it constructively in his development of doctrine and discipline, and in his heresiological battle over the hermeneutical ownership of Paul defends its place in a thirteen-epistle corpus.Footnote 33 In the East, Theophilus of Antioch (writing c. 180) in his apology employs Titus and 1 Timothy alongside Romans as ‘ὁ θɛῖος λόγος’, which surely presupposes acceptance of its Paulinicity.Footnote 34 Clement of Alexandria (writing c. 200) explicitly receives it as a divine (θɛσπέσιον, θɛίαν) epistle of the apostle, and condemns the rejection of 1 and 2 Timothy by certain ‘heretics’.Footnote 35 Evidently by the turn of the third century Titus was widely being read by mainstream Christians in the theological context of the Pauline epistolary deposit. It formed a constituent part of their conceptual or ‘virtual’ Pauline collections.Footnote 36

The transmission of Titus in comprehensive fourteen-epistle Pauline collections was standard in the Greek manuscript tradition from the mid-fourth century (the pandect Codex Sinaiticus encompassing the earliest non-fragmentary and therefore unambiguous example), but not necessarily as early as the third.Footnote 37 E. Randolph Richards suggests that a thirteen-epistle Pauline ‘collection’ (minus Hebrews) began in the later first century with the transmission of Paul's own letter-copies to his disciples at his death: he probably followed the ancient letter-writing custom of retaining personal copies of his letters in codex notebooks, to mitigate the risks of loss or damage to the original, and for future reference (hence the early Christian predilection for the codex format).Footnote 38 But insofar as the authenticity of the three so-called ‘Pastoral epistles’ (and other ‘deutero-Paulines’) constitutes the minority paradigm,Footnote 39 few accept the argument as a whole.Footnote 40

Tertullian would have it that the absence of 1–2 Timothy and Titus from the heretic Marcion of Sinope's bipartite ‘Bible’ of Euangelion (Luke) plus Apostolikon (Galatians, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Romans, 1 Thessalonians, 2 Thessalonians, Laodiceans [=Ephesians], Colossians, Philippians, Philemon) constituted their deliberate expulsion from an inherited, i.e. pre-140, Pauline corpus: ‘Soli huic epistulae [sc. Philemon] brevitas sua profuit ut falsarias manus Marcionis evaderet. Miror tamen, cum ad unum hominem litteras factas receperit, quod ad Timotheum duas et unam ad Titum de ecclesiastico statu compositas recusaverit. Affectauit, opinor, etiam numerum epistolarum interpolare.’Footnote 41 Polycarp of Smyrna's apparent utilization of 1 Tim 6.7, 10 and 2 Tim 4.10 in two ‘clusters’ of predominantly Pauline allusions (Epistola ad Philippenses 3.2–4.1, 9.1–10.1) implies his acceptance of their ostensible Pauline authorship, two decades previous to Marcion, and renders the claim plausible.Footnote 42 However, Tertullian's portrayal of Marcion's corruptive editorial enterprise is complicated by his heresiological rhetoric, as well as his temporal distance from Marcion (some fifty years) and his dependence on lost refutations (including those of Justin Martyr and Theophilus).Footnote 43 Marcion's redactional activities are now thought to have been far less extensive and tendentious than Tertullian and his other opponents contended; Ulrich Schmid shows that most of the allegedly peculiar Pauline readings are attested elsewhere in the tradition, in an early stratum of the so-called ‘Western’ text as well as the old-Syriac.Footnote 44 Whilst the handful of deliberate omissions with which Marcion can confidently be credited demonstrate a capacity for use of the pen-knife when it suited him, Marcion may simply have appropriated a primitive Pauline collection to which the epistles to Timothy and Titus did not belong.

Jerome Quinn argued for their early circulation with Philemon in an independent Pauline collection conceived as epistles ‘to individuals’ (i.e. individual co-workers), the companion to a collection of epistles ‘to churches’ (the two eventually being amalgamated into a single canonical edition).Footnote 45 Quinn took Tertullian's complaint that Marcion inconsistently includes only one of the epistles addressed ‘ad unum hominem’ to presuppose an ‘individuals’ collection, from which Marcion plucked Philemon and added it to a nine-epistle ‘churches’ collection in an explicitly theological move to exclude the ‘Pastoral epistles’. Quinn also thought the two sub-collections to be presupposed by the separate treatment of the nine ‘church’ and four ‘personal’ epistles in the stichometric arrangements of the later manuscripts (ostensibly marking a ‘seam’ in the collection), and in an ancient argument for their catholicity in response to a theological problem with their particularity, first attested by the Muratorian fragment: Paul, like John in his Apocalypse, wrote ‘nonnisi nominatim septem ecclesiis’ (albeit twice each to the Corinthians and Thessalonians ‘pro correptione iteretur’) and thereby addressed the one universal Church (II.47–60); furthermore, he wrote one to Philemon, one to Titus and two to Timothy ‘pro affectione et dilectione, in honore tamen ecclesiae catholicae in ordinatione ecclesiasticae disciplinae sanctificatae sunt’ (II.60-63).Footnote 46 Quinn quite rightly acknowledged that it is not codicologically demonstrable that 𝔓32 was a leaf from just such an ‘individuals’ collection, since any number of epistles could have preceded Titus in the first part of the codex. Nevertheless he thought this feasible on the basis of the said principle of aesthetic distinction, supposedly illustrated in practice by the 𝔓46 codex of the mid-second to mid-third century.Footnote 47

The magisterial 𝔓46 preserves most of Romans, Hebrews, 1-2 Corinthians, Ephesians, Galatians, Philippians, Colossians and 1 Thessalonians in eighty-six leaves of a single quire, and has widely been taken as a ‘churches’ edition. The outer parts of the codex are defective, with the last surviving page breaking off at 1 Thessalonians 5.28. Frederic Kenyon, one of the editors, inferred from preserved pagination that seven leaves were lost at the beginning (thirteen pages for Rom 1.1-5.17 and a blank cover page) and by implication seven leaves lost at the end, which would be insufficient to accommodate all of 2 Thessalonians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, Titus and Philemon. Additional leaves could have been attached at the end so as to house a fourteen-epistle collection, but Kenyon thought this unlikely, and assuming that the ‘Pastoral epistles’ constituted a group that would not have been split up he favoured a ten epistle hypothesis: 2 Thessalonians occupied two of seven missing leaves and the remaining five were left blank.Footnote 48 Kenyon's proposal was reiterated by influential text critics such as Bruce Metzger and (initially) Eldon Epp and became standard.Footnote 49

Jeremy Duff's review essay picks up on earlier observations of the crowding of text in the second half of the 𝔓46 codex, and proposes rather that the scribe had intended to copy all fourteen Pauline epistles but miscalculated the space required and finished accidentally part way through 2 Timothy. S/he may then have abandoned the manuscript as incomplete, but more likely did add a few (three) extra leaves or a small quire to complete the edition (as exemplified in some Nag Hammadi codices and the Toura Origen manuscript).Footnote 50 Duff concludes that, either way, the scribe ‘produced 𝔓46 assuming that the Pastorals were a constituent part of the Pauline corpus’.Footnote 51 If 𝔓46 does witness the assumption that 1–2 Timothy and Titus were components of a fourteen-epistle Pauline collection, one might suppose, given their rough contemporaneity, that the same assumption shaped the formation of the 𝔓32 codex. Aspects of Duff's methodology are questionable, however. Epp thinks Duff exaggerates the scale of textual compression by insufficiently accounting for normal variation arising from the changing widths of pages in a single quire.Footnote 52 David Parker criticises his short-cut in calculating the average number of letters per page from an ‘adjusted’ modern edition rather than actual counts of extant lines, and doubts the appropriateness of his analogies for the addition of supplementary sheets.Footnote 53 Edgar Ebojo observes para-textual features—the constant size of the script, the constant spacing of the lines, the failure to utilize spare lines at points of transition from one book to another, the fact that an increase in the number of lines per page does not necessarily correlate with an increased number of letters per page—and fundamentally questions whether the scribe was really intent on maximising the available space in order to avoid over-running.Footnote 54 Ultimately, whether 𝔓46 was a late survivor of a ‘churches’ collection or a larger edition containing some or all of the ‘Pastoral epistles’ and Philemon cannot be codicologically demonstrated.

The scope of the remaining early Pauline manuscripts is also inconclusive due to their fragmentary state. The 𝔓30 = P.Oxy. 1598 codex, extant only at portions of 1 and 2 Thessalonians, evidently once housed a sizeable collection since it bears the pagination σζ, ση (207, 208) on two surviving pages. There was probably sufficient room in the preceding 206 pages to have accommodated the beginning of 1 Thessalonians and the rest of the ‘church’ epistles,Footnote 55 but there is no way to determine how much (if any) capacity there was at the end of the codex for further texts. The 𝔓92 = P.Narmuthis 69.39a + 69.229a codex must have contained at least three texts because Ephesians and 2 Thessalonians do not appear to be consecutive. The column numeration preserved in 𝔓13 = P.Oxy. 657 + PSI 1292 (μζ = 47) shows that Hebrews was not the first text on the verso of the roll since it would have begun around column 44; Romans would be a good fit (cf. 𝔓46). Possibly 𝔓15 = P.Oxy. 1008 (1 Corinthians) and 𝔓16 = P.Oxy. 1009 (Philippians) belonged to the same codex, 𝔓49 = P.Yale 415 + 531 (Ephesians) and 𝔓65 = PSI 1373 (1 Thessalonians) to another.Footnote 56 Most of the rest are, like 𝔓32, highly fragmentary and preserve only a single text.Footnote 57 None can be pressed as proof of ‘churches’, ‘individuals’ or comprehensive Pauline collections.

The main difficulty with Quinn's suggestion is not so much the uncertain scope of the 𝔓46 codex as the growing recognition of a pre-Marcionite edition of ten epistles ‘to seven churches’ that counted Philemon with Colossians as addressed to (part of) the same community. Nils Dahl and Harry Gamble detect its vestiges behind an obsolete ‘Western’ arrangement of epistles which enumerated them according to the principle of decreasing length, counting those to the same church as one unit and so emphasising the number of churches rather than the number of epistles.Footnote 58 Since Marcion's Apostolikon largely followed this order (with the exception of Galatians at the head), it is thought to have been structurally indebted to a ‘seven churches’ edition that was originally ordered by decreasing length, i.e., Corinthians (1–2), Romans, Ephesians, Thessalonians (1–2), Galatians, Philippians, Colossians–Philemon, but was modified owing to chronological considerations.Footnote 59 The textual transmission of the epistles is also explained ‘as due to alterations and conflations of two basic editions, one in which Paul's thirteen (or fourteen) letters and another in which his letters to seven churches were arranged according to the principle of decreasing length’.Footnote 60

As a corollary, most have accepted Peter Trummer's contention that the epistles to Timothy and Titus probably never circulated independently of the ten ‘church’ epistles, for strategic reasons: as a pseudepigraphal ‘Corpus pastorale’, they must have been written and published ‘im Zuge einer Neuedition des bisherigen Corpus [Paulinum]’, because a different origin would have had to face a very perceptive critique and rejection.Footnote 61 Their personal address could well be an intrinsic falsification strategy to explain their relatively late appearance in anticipation of their readers' Echtheitskritik. Footnote 62 But it ought to be noted that the literary unity of a ‘Corpus pastorale’ is no longer axiomatic; recent emphasis on their individuality has led to various proposals of diverse authorship—whether distinguishing 2 Timothy from 1 Timothy and Titus (Michael Prior, Jerome Murphy-O'Connor, James Aageson), 1 Timothy from 2 Timothy and Titus (Jens Herzer), or all three from each other (William A. Richards)—which imply some other form of conglomeration.Footnote 63

Yet whatever their origin, there is general agreement (pace Quinn) that the bipartite argument of the Muratorian fragment reads more naturally as utilizing the churches–individuals distinction for the purpose of supplying a post facto apology for a thirteen-epistle edition, especially since (Eusebius reports that) Gaius of Rome, a contemporary churchman, enumerated thirteen epistles of Paul, distinguishing only Hebrews from the rest.Footnote 64 Thus the Muratorianum notionally sets a terminus ante quem for the inclusion of the epistles to Timothy and Titus at the turn of the third century.

4. Conclusion

This study offers a new, expanded reconstruction of the third-century John Rylands fragment of Titus (𝔓32), working from the two partially extant pages to the preceding page under the assumption that the scribe was reasonably consistent in the design of their written areas. The beginning of the epistle is estimated to fall seven or eight lines short of the top of the column on the preceding page, which leaves five or six lines (a fifth) of the available writing space to be accounted for once a conventional superscription is inferred. The discrepancy indicates that Titus was preceded by at least one other text; 𝔓32 belonged to a multi-text codex. The identification of any accompanying text(s) cannot be codicologically deduced, but the canonical reception of Titus at the turn of the third century generates the expectation that it was normally being transmitted in a collection of thirteen or fourteen Pauline scriptures, and the 𝔓32 codex was probably no exception.