‘Away, Away, my steed and I,

Upon the pinions of the wind’.Footnote 1

The epigraph above derives from Lord Byron's poem, Mazeppa (1819). Without additional context, these lines may propose an image of a triumphant hero mounted upon his horse. The command ‘away, away’ evokes a propulsive dynamism, while pinions of the wind conjure impressions of liberty and transcendent flight. In short, these lines portray a fusion between rider and horse where action and unfettered freedom define heroism. However, those familiar with Byron's narrative, particularly the wild ride, know that neither the hero nor the horse are truly free. As the legend narrates, Mazeppa is punished for having an affair with a Nobleman's wife by being bound, naked, to the back of an unbroken horse for a tortuous three-day ride. In this context, ‘away, away’ initiates a spur that sets the ride in motion and pinions, recast as the verb pinioned, invoke the binds that tether Mazeppa to the steed. Yet the heroism implied by ‘away, away’ is not lost, nor is the tension between pinioned, cords that hinder freedom, and pinions as the source of freedom, easily resolved. This complexity acts as a potent metaphor for Mazeppa's process of ‘becoming’. He is at once passive and active, vulnerable and strong, suffering and triumphant, bound but set free.

‘Away, away’ was a personal motto for Franz Liszt. During his virtuoso years, for instance, he often expressed a desire to withdraw from his relentless touring, but his success and celebrity ‘kept him bound to his piano “like Mazeppa bound to his horse”’.Footnote 2 Liszt also aligns Mazeppa's binding with his fears of being a misunderstood artist. Following a concert at Dresden in February 1844, Liszt wrote to Marie d'Agoult asking

so am I the type of person who is difficult for the Public, as well as Individuals, to make out? Does one have to get used to me and to submit totally to my point of view? Sometimes, I don't understand myself, either in my relations with others, or of myself. “Away, Away!”Footnote 3

Liszt's allusion to Byron's Mazeppa does not stop at biography. The characteristics of Mazeppa's heroic persona inspired him to compose several Mazeppa-works beginning in the late 1820s. By the time his symphonic poem Mazeppa was published in 1856, the myth had accumulated layers of symbolic associations. Liszt's preface alone reveals a chain of meanings by including Byron's now familiar inscription ‘away, away’ and Victor Hugo's poem ‘Mazeppa’ in its entirety. This intertext, a complex interrelationship between similar and related works, transformed Mazeppa into a ‘mythic-messianic hero’, a man created by – and redeemed in – his suffering.Footnote 4 Or, in Jürgen Schultze's valuation, Mazeppa is a ‘man of genius who endures so much for the sake of his art’.Footnote 5 The Mazeppa myth became an allegory for how the power of genius is a hard-won prize, and to achieve its reward, the artist must be painfully pinioned to its unyielding force – ‘away, away’!

To fully appreciate how Liszt relates Mazeppa as both a subject of compositional creativity and a source of personal connection requires consideration of the myth's intertextuality. Bruno Sibona calls the Mazeppa myth a ‘super-complex’ in which each text is perceived independently and as a composite of other texts.Footnote 6 Joanne Cormac describes intertextuality as an interpretive framework that speaks to ‘broad debates about historicism, authorial intention and hermeneutics’.Footnote 7 Deciphering intertextual associations is undertaken by referencing paratexts – titles, epigraphs, quotations, metaphors, allusions and so forth. But intertextuality also connects extramusical associations to musical subjectivities by merging, as Cormac continues, ‘emotional, personal and individual music’ with ‘the figures of composer, performer, and/or a protagonist from literature or visual art’.Footnote 8 Drawing from Cormac, this article considers the broader sources that informed Liszt's Mazeppa and offers an interpretation that extends beyond the preface to include an array of Mazeppa ‘texts’ that have appeared since the mid-eighteenth century. These include a quasi-historical narrative, poetry and visual art, along with Liszt's original commentary for Mazeppa and his defence of programme music in his Berlioz and His ‘Harold’ Symphony essay. I argue that connecting these threads of cultural history adds depth to the musical gestures, motives and themes in Liszt's work, and illuminates the mythology of heroic suffering in the pursuit of artistic genius.

Between Form and Content: Subjectivity in Mazeppa

Liszt's Mazeppa has frequently been dismissed as a formless work with little to offer beyond insipid mimetic tropes. At its first performance in Leipzig on 26 February 1857, audience members allegedly booed and hissed.Footnote 9 In a review published in the March issue of Signale für die musikalische Welt, an anonymous reviewer described Mazeppa specifically as a ‘colossal act of tastelessness’ where ‘mere noise is captured and turned into cheap effects through the coarsest handling’.Footnote 10 Eduard Hanslick similarly asserted that Mazeppa was anti-musical, warning ‘every sane and sensible person’ to ‘turn away’.Footnote 11 Admittedly, it is possible to interpret Liszt's motives, gestures and thematic material as surface-level illustrations. But like all programmatic works, Mazeppa is not music alone: to neglect or completely dismiss the extramusical associations limits interpretative potential. To help mitigate misunderstanding, Liszt published Berlioz and His ‘Harold’ Symphony, an essay that outlines his aesthetic approach to composition and defends programme music as a subjective expression. He argues for the importance of programmes in clarifying meanings expressed in instrumental music, writing that the painter-symphonist introduces ‘the approximation of certain ideas, the affinity of certain figures, the separation or combination, juxtaposition or fusion of certain poetic images’ resulting in ‘a series of emotional states which are unequivocally and definitely latent in his consciousness’.Footnote 12 When musical representation is present, it is done to draw out associations of deeper, non-representational meaning. To elucidate this idea, Liszt creates an analogy between instrumental music and sculpture, writing that those with ‘poetic temperaments’ will view sculpture not as a representation of the subject but as

passions and forms, generating certain movements of the affections, rather than the specific particular individuals whose names they bear – names, moreover, which are for the most part again allegorical representations of ideas. For them, Niobe is not this or that woman stricken by this or that misfortune; she is the most exalted expression of supreme suffering.Footnote 13

Some of Liszt's contemporaries base their interpretation of Mazeppa in this vein. Felix Draeseke defended Liszt's musical representation of the hero, writing that Mazeppa contains ‘a deeper, inwardly spiritual context even when it seems that only the actions of the narrative are given’.Footnote 14 Claude Debussy praised Liszt for his evocation of a ‘stormy passion that rages throughout’, implying that emotion contributes to Mazeppa's external and internal experience.Footnote 15 The generally more positive critiques by Draeseke and Debussy show that illustrative musical themes, motives and gestures are not merely facile mimetic tricks. Instead, approaching Mazeppa through the processes of analysis, hermeneutics and intertextuality offers an interpretation of these same musical signifiers endowed with meaning through the cultural contexts embedded within them. Mazeppa contains a more complicated narrative that highlights the symbolic value of Mazeppa's heroic expression.

The extramusical programme is also more than a text to aid in interpreting music. Throughout his Berlioz essay, Liszt alludes to art embodying subjectivity, which he asserts derives from ‘extremes, opposites, high points bound one to another in a continuous scene of various varieties of being’.Footnote 16 Programme music, as a ‘poetic art’ with intertextual references, contains the ‘indestructible life principle of which the human soul has embodied in them’.Footnote 17 Further, Liszt implies that programme music maps the composer's subjective experience of the text (along with those potential meanings) onto his work. The preface guides the listener to the ‘psychological moment which prompts the composer to create his work and of the thought to which he gives outward form’.Footnote 18 Or to frame it in line with Liszt's poetical language, programme music seeks to communicate the ineffable, from soul to soul, through the expressive qualities of musical forms, themes and gestures along with its intertextual and intersubjective content. Understood in these terms, the programme does not describe or explain the music but instead prepares the listener to experience what the subjects in the programme experience through music. In Mazeppa, Liszt conveys the hero not merely as a rider on a horse but as a representation of the artist struggling with/against genius as it takes him to new creative territory.

While the concept of musical subjectivity is challenging to define, at its core lies the formation of the subject through socio-cultural mediation.Footnote 19 Cormac offers a mode of interpreting musical subjectivities, writing that intertextual references are expressed in four primary ways: (1) a (virtual) ‘voice’; (2) disjunctions in the musical fabric; (3) genre relationships within instrumental music; and (4) topics and/or gestures.Footnote 20 In particular, topics and gestures offer an interpretation of musical signifiers that may be expressions of subjectivity through the cultural contexts embedded within them.Footnote 21 Benedict Taylor characterizes musical subjectivity as active and transformative, as intersubjective, and as an emergent, temporal and interpretive process:

music may be heard as an action or type of agency, as speaking to us through another persona, as immediately expressive of feelings and emotions that are felt as ours, as pure presence, as another consciousness, or even as an extension of or surrogate for one's self. … Often there is not a single, realistic subject formed by music, but disparate elements of that which may constitute a subject.Footnote 22

Taylor outlines how the listener perceives musical subjectivity as a collection of possibly disparate intertextual elements – voice, agency, expressivity and extramusical texts. By voice, Taylor argues that subjectivity arises from overlapping our subjectivity with the composer's fictional one. Agency refers to the tonally directed motion moving to a defined ending. It is determined by the interaction of melody, harmony and rhythm and is perhaps coded by an illusion of coherence and causality. Expressivity refers to the preeminent language of the emotions, but not necessarily of the composer. Rather, it arises from a ‘hypothetical protagonist “in” (or “behind”) the music’.Footnote 23 In programme music, extramusical texts denote a musical subject's existence, introducing a certain degree of precision. This unity of the dissimilar echoes Liszt's conception of programme music. He frequently returns to the theme of bringing together a plurality of diverse and sometimes contrary elements, writing that art, like nature, is ‘rich in variously formed and dissimilar phenomena’ and ‘weds related or contradictory forms and impressions’ within the soul.Footnote 24 Liszt elevates ‘diverse unity’ as the governing principle of ‘the All’ and casts this comingling of diverse forms as not only natural, but life-giving, calling it the destiny of art.Footnote 25

Taking all of this together, my approach in this article is to analyse Mazeppa as if listening for the protagonist and letting the character of that musical subject inform my interpretation. I take seriously Liszt's intention to embed more profound significance within a musical subject comprised of mimetic elements, as a sculptor might form an allegory through representational forms. Adopting this approach does not mean conceding to Liszt's suggested listening practice for programme music in all cases, but rather involves a willingness to understand him on his terms. Moreover, Liszt's commitment to wedding contradictory forms invites a relational understanding of subjectivity that makes sense of Mazeppa's contradictory characteristics. Hearing the musical subject in this work requires attention to voice, expressivity, motives, gestures, themes, and extramusical intertexts to construct, layer by layer, an interpretation of Mazeppa's symbolic significance.

Boundless Horizon: Mazeppa (Inter)Texts

Ivan Stepanovyeh Mazeppa was born into the Ukrainian gentry in c. 1632. He spent his youth in the Polish court but returned to Ukraine under mysterious circumstances.Footnote 26 Mazeppa later emerged as a soldier in the Cossack army, eventually working up the ranks to become Hetman, or military commander. He was a vassal to Peter the Great but later conspired against the Tsar and entered into secret negotiations with King Charles XII of Sweden. The culmination of this alliance was the Battle of Poltava in 1709, an event that signalled both Mazeppa's demise and solidified his place as a Ukrainian folk hero. The ‘real’ Mazeppa figured primarily in Eastern European contexts. However, the publication of Voltaire's Histoire de Charles XII, roi de Suède (1731) brought Mazeppa to Western European readers. While his primary subject examines the reign, rise and fall of the Swedish King, Voltaire briefly recounts Mazeppa's youthful transgression and punishment:

on the discovery of an intrigue with the wife of a Polish nobleman, the latter had him tied, stark naked, to a wild horse, and set him free in that state. The horse, which had been brought from Ukrainia, returned to his own country, carrying Mazeppa with him half dead from hunger and fatigue.Footnote 27

This account of Mazeppa's Ride is undoubtedly a fabrication.Footnote 28 However, issues of accuracy aside, the evocative image of horse and rider bound together against their collective will captured the imagination of Romantic-era artists. Among the earliest and most influential was Byron, whose portrayal of Mazeppa's punishment effectively propelled the ride narrative to legendary status. Byron's Mazeppa draws primarily from Voltaire's history. However, in his re-interpretation, Byron focuses on Mazeppa's profound suffering and triumphant survival. Additionally, Byron prefaces his poem with three extensive quotations from Voltaire's Histoire that allude to the critical relationship between horse and rider.Footnote 29 Byron's poem establishes the symbiotic relationship manifest in the pinions of simultaneous suffering and freedom, which inspired other artists to meditate on the Mazeppa myth.Footnote 30 Notable among these artists is Théodore Géricault, whose Mazeppa from c. 1820 epitomizes the image of the suffering hero.

Victor Hugo's poem ‘Mazeppa’, first published in his larger collection Les Orientales (1829), was directly inspired by Byron, but contains additional layers of meaning.Footnote 31 To begin, Hugo incorporates two intertexts. The first is Byron's familiar poetic line in translation ‘En avant! En avant!’ The second is a dedication to Louis Boulanger, whose painting Le Supplice de Mazeppa (1827) was familiar to Hugo. Much like Byron's Ride narrative, Hugo's poem does not contain a plot. Instead, it relies on descriptive language to amplify the metaphor of flight (‘Nous volons’). But Hugo adds elements of Boulanger's visual imagery, particularly in the first section, casting Mazeppa as a heroic genius rejected by the old guard. In the second section, Hugo transforms the horse into Pegasus, an allegory of the genius who flies the rider through a gauntlet of terrors and recriminations. Endowing both Mazeppa and his steed with allegorical references suggests a vision rather than a story.Footnote 32 Hugo explores non-representational subjective emotions of artistic agony through the representational elements of the horse and rider.

The intertexts that inform Liszt's Mazeppa include Voltaire's quasi-historic figure of a great but tragic military hero and Byron's and Géricault's focus on the agony of the ride as a model of heroic suffering and internal resolve. In contrast, Hugo and Boulanger recast Mazeppa's suffering as an allegory of the artist's struggle with genius. Furthermore, the figure of Mazeppa in these works borrows from the symbolism of Christ's crucifixion, death and resurrection. Like Christ, Mazeppa is rejected by the authorities, passively suffers physically and mentally while splayed in torture, endures three days of suffering to be revived and reborn as a king who leads against oppression in perpetuity. Hugo, in particular, recounts the ride through this messianic lens; however, his vision focuses on artistry and creativity, not religion.

The complex chain of intertexts was pervasive even as Liszt composed his earliest Mazeppa works. The symphonic poem derives from a series of piano studies.Footnote 33 The first related piece was published as No. 4 in Etudes en douze exercices (1826). While this exercise lacks a primary theme and has no known extramusical associations, it contains a pervasive three-note motive in the opening bars. This figuration was retained as the accompaniment to a new theme in the second version, published as part of the Grandes etudes (1839). Like the first study, there are no explicit programmatic indications. However, a letter to Marie d'Agoult in 1832 indicates that Liszt was composing a work evoking ‘Mazeppa running at a quadruple gallop’.Footnote 34 This letter reveals that, at the very least, he was thinking about the breakneck speed of the ride. Or perhaps Carl Loewe's Tondichtung ‘Mazeppa’ Op. 27 (1830), the first known composition based on the Mazeppa myth, served as inspiration. The third re-composition, a stand-alone Mazeppa etude (1840), expands the second version and includes a five-bar introduction, a conclusion in D major and three integral extramusical associations: the title, a dedication to Hugo and the closing line of his poem ‘Et se relève roi!’ as part of the triumphant conclusion. The final iteration of Liszt's ‘Mazeppa’ solo piano works was published as part of the twelve Etudes d'exécution transcendante in 1852. Along with retaining its programmatic elements, this version is longer, likely the result of Liszt drafting his symphonic poem at the same time. Liszt reached the maturity of reworking the Mazeppa myth in his symphonic poem. He retained the propulsive triplet figure of the accompaniment and the thematic transformations of the main theme, but also incorporated an expanded andante section leading to a newly composed march. Furthermore, the orchestral transcription creates a new colour palette, allowing for greater emphasis on the emotive aspects of the titular character.

Examining the intertexts of Mazeppa reveals that Liszt gained inspiration from characterizations of the heroic. This is not new for Liszt. Five of his 13 symphonic poems are based on heroes from history, mythology and literature.Footnote 35 Yet, these heroes differ from Aristotelian depictions of epic and tragic heroes who are typically gods, demi-gods or even men who live, fight and suffer beyond common human experience.Footnote 36 Central to their emergence as heroes are journeys to protect or redeem humankind from a fallen world.Footnote 37 For some mortal heroes, the reward for their extraordinary deeds is apotheosis – the moment of divine transfiguration. In music research, the myth surrounding Beethoven serves as a poignant representation of heroes and the heroic. Beethoven simultaneously exemplifies aspects of the archetypal hero, portraying the composer as highly individual and socially isolated. These characteristics, as Scott Burnham suggests, are embedded in Beethoven's compositions, particularly his Eroica, revealing a universal reflection of human experience ‘cast as heroic experience’.Footnote 38 Furthermore, Burnham's ‘Beethoven Hero’ reflects more than a composer as a musical hero, and one who writes ‘heroic music’, but a figure whose music touches, and perhaps redeems, the hearts of humanity. Liszt's character pieces, however, explore the ideal of Romantic heroism, fixating on the ‘sensibilities, innate self-awareness and the complexities of their being’.Footnote 39 This focus on subjectivity often recasts heroes as ‘great men’ or even geniuses dominated by passivity as not only inaction and vulnerability but also their passion: the ability, even desire, to endure suffering.Footnote 40 Liszt certainly draws from this discourse, writing in his Berlioz essay that the modern ‘philosophical epopoeia’ recounts the hero's ‘inner events’, or the ‘affections active within [the] soul’.Footnote 41 Liszt's Mazeppa incorporates a variety of musical gestures – distinguished from the Horse motive and main theme – that are not readily illustrative but, with a deeper understanding of the intertexts, reveal a connection with heroism to genius.

Structural Considerations

Liszt's Mazeppa has accrued several formal interpretations that engage with the extramusical to varying degrees. Carl Dahlhaus focuses on the main theme's constituent parts, showing how its transformation throughout the Ride section reflects a quasi-sonata structure. He does not, however, consider the musical material of the March.Footnote 42 Taking a narrative approach, Michael Stegemann argues that the formal structure in Mazeppa is determined by ‘linear hearing’.Footnote 43 He asserts that it is possible to decipher an archetypal heroic journey from suffering to triumph without a close reading of the programme, just in the transformation of the theme. Cormac, on the other hand, suggests that the formal divisions in Mazeppa derive from Hugo's two-part poetic structure. Within this wider structure, she argues that there is an introduction, an A section with variants, a contrasting B section, development, recitative, fanfare and finale, each deriving from the transformation of the main theme.Footnote 44 My interpretation aligns closer to Cormac's, particularly in the two-part structure and formal divisions based on thematic transformation. However, I approach Liszt's Mazeppa with a greater emphasis on the intertexts that shape the work, including both Byron's and Hugo's poetic structure.

Byron's ballad is structured as a frame narrative, or a story within a story. The narrator sets up the main story by situating King Charles XII's and Mazeppa's exile following their defeat at Poltava. Charles asks Mazeppa to entertain him with a tale in which the aging Hetman recounts the ‘school wherein [he] learn'd to ride’.Footnote 45 The middle portion recounts Mazeppa's tortuous heroic journey. In the closing lines, the narrator returns to relay how Mazeppa's story lulled the Swedish king to sleep. The frame structure of Byron's poem dramatizes Mazeppa's transformation from a historic soldier to a legendary hero who survives the impossible and, in turn, amplifies the meanings inscribed in his two contrasting characters. In his youth, Mazeppa survives a tortuous ride, finding victory through death. Then, in his old age, he attempts to snatch victory from the jaws of death again. In Liszt's Ride section, there is an implication of victory in death; and in the March, there is a sense of death in victory – a parallel construction.

Hugo's two-part structure is perhaps more obviously apparent in the large-scale form of Liszt's Mazeppa. The first section favours detail and consists of smaller subsections that focus on the narrative progression of Mazeppa's binding, movement, suffering and eventual triumph (see Table 1). The section closes with the fall of the horse: ‘the horse sinks and dies’ [‘Le cheval tombe aux cris de mille oiseaux de proie’], taking the rider along with him.Footnote 46 The second section opens much like the first, but reframes the descriptive aspects of the Ride into a commentary on the allegory of flight and the personification of genius. But unlike the first section, the winged horse takes Mazeppa on a ride to spiritual elevation. The content, therefore, points toward ‘génie’ as the driver of Mazeppa's experience. The mystical revery of the second section might tempt the reader to interpret the poem's first section as a portrayal of Mazeppa's suffering and the second as his triumph as king. Yet, the second section contains as much terror and pain as the first and ends with death before Mazeppa's allegorical coronation. Rather than a sequential narrative, the two sections are concurrent retellings of the Mazeppa myth: the first through an illustrative and representational mode, the second through a spiritual and mythical mode.

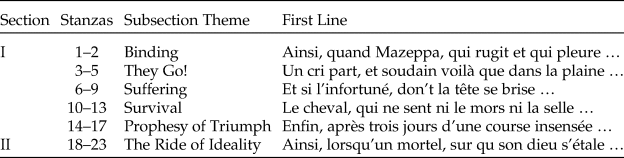

Table 1 Large Structure of Hugo's ‘Mazeppa’

As in Hugo's poem, the large structure of Liszt's Mazeppa consists of two sections that provide complementary depictions of the same journey: the first ‘Ride’ section emphasizes suffering, and the second evokes a march-like victory (see Table 2). On a micro level, the Ride and March have different formal structures. The Ride derives some of its musical material from the fourth etude and contains an introduction, a theme with transformations and a transitional passage to a new March section. The March is in simple binary form and contains two new themes. In the final bars, Liszt recalls the main theme of the Ride for the archetypal apotheosis. This broader structure reveals that while the Ride and the March are separate sections, both nevertheless link suffering and triumph into a concurrent heroic experience at once triumphant and militaristic.

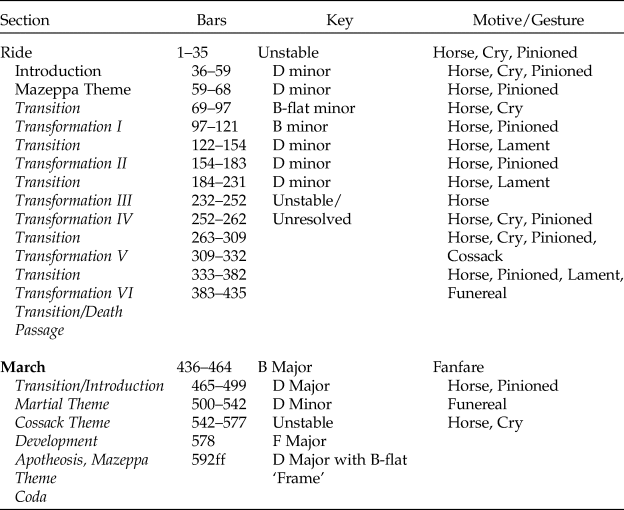

Table 2 Formal Structure: Themes, Motives and Gestures of Liszt's Mazeppa

Within the larger form, Liszt incorporates motives, gestures and distinctive themes to tell the deeper story of Mazeppa's subjective experience. I use the term motive to designate salient, recurring melodic or rhythmic figures that never expand into full thematic material. Gesture refers to short, mutable and often fragmented musical ideas. Like motives, these musical gestures do not transform into a melody, but rather provide additional layers of meaning to the primary thematic material. Theme refers to a longer, repetitive musical passage with a cohesive structure. For clarity, I will introduce the descriptive titles I have ascribed here but will elaborate on their possible meanings in my following interpretation. Liszt establishes the primary ‘Horse’ motive and the ‘Cry’ and ‘Pinioned’ gestures in the introduction. The main ‘Mazeppa’ theme charges in at bar 36 and undergoes six transformations all mediated by iterations of the Horse motive and the Cry and Pinioned gestures. A new ‘Lament’ gesture appears with the second and third transformations. To close the Ride section, a transitional quasi-recitative ‘Death Passage’ leads to the March. Here, the Pinioned motive reappears, but its statement includes aspects of a ‘Funereal’ gesture to signify the end of the brutal Ride. The March opens with a brass Fanfare, which leads directly to a new ‘Martial’ theme based on a reworking of Liszt's Arbeiterchor (1849). This is followed by a secondary ‘Cossack’ theme that evokes a ‘pastiche oriental’ melody.Footnote 47 The apotheosis – a brief statement of the Mazeppa theme – appears at bar 578, and is followed by a singular statement of the Funereal gesture from the Death Passage as a frame to the piece. The varied motives, gestures and themes set the overarching poetic narrative of the symphonic poem. But the musical material of Mazeppa also captures the emotional content encapsulated in the narrative, fortified by substantial intertextual and intersubjective associations. Despite the difference in tone between the Ride and the March, both evoke a death amidst victory in their endings.

Pinioned: Mazeppa's Suffering

Horse

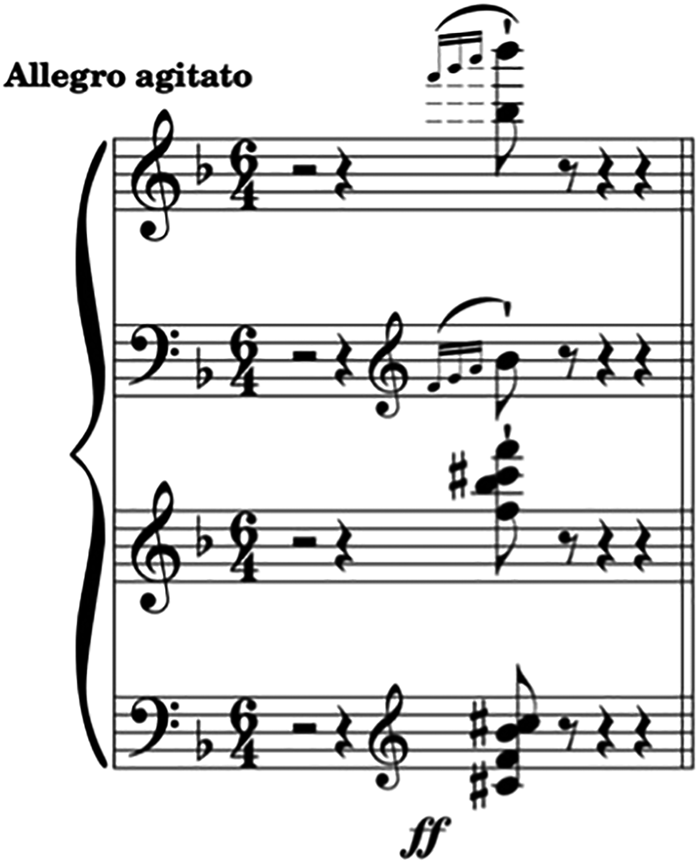

Liszt's Mazeppa is a ‘warhorse’, a type of composition Dana Gooley classifies as dramatic, virtuosic and militaristic.Footnote 48 The metaphor of the warhorse emerged during Liszt's touring years in which he programmed virtuoso compositions to imbue his public persona with the heroism and physicality of a military figure. These works often contained power akin to equestrian movement. From the opening bars of Mazeppa, Liszt evokes the warhorse subject by integrating pervasive triplets and semiquavers, marked allegro agitato, consistently played by the strings. This motive appears most obviously in the Ride, but aspects of its musical qualities – scoring and rhythm – are also present in the March. There is no question that this ‘Horse’ motive (see Ex. 1) is a representation of a physical character.Footnote 49 Perhaps this point is the impetus behind Michael Saffle's assertion that, although Liszt was a ‘marvelous creator of effects’, his best works, which does not include Mazeppa, ‘consist of more than effects’.Footnote 50 Yet in considering the intertexts, there is a method to presenting the mimetic helter-skelter and relentless energy of the horse.Footnote 51 The motive amplifies speed and unpredictability, an aspect present in Byron's ballad:

‘We sped like a meteor through the sky’;

‘fast we fled, away, away – ’;

‘At times I almost thought, indeed,/He must have slacken'd in his speed’.Footnote 52

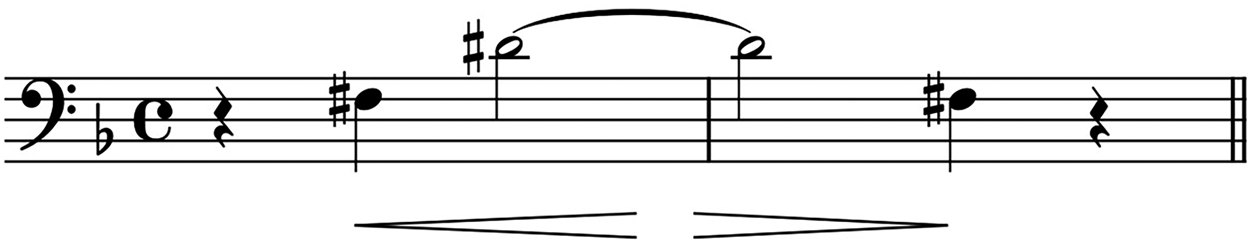

Ex. 1 Liszt, Mazeppa, Horse Motive, bars 1–2. Transcribed from Franz Liszt, Mazeppa, in Franz Liszt-Stiftung, Franz Liszt: Musikalische Werke, Serie I, Band 3 (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1909)

And in Hugo's poem: ‘the horse, which feels neither saddle nor bit,/Flies ever’ [‘Le cheval, qui ne sent ni le mors ni la selle,/Toujours fuit’.]Footnote 53 Furthermore, speed and movement suggest subjective agency, and in Byron's Mazeppa, that agency derives from its compulsion to return to Ukraine: ‘In truth, he was a noble Steed,/A Tatar of the Ukraine Breed’.Footnote 54 Musically, the signification of agency in Mazeppa is more difficult to determine. Taylor describes subjective agency as an ‘apparent ability to act towards a defined end’.Footnote 55 This can include harmonic, thematic, rhythmic and/or formal progression. Liszt certainly emphasizes consistent rhythmic properties, scoring in the strings and constant forward movement to evoke agency. Yet despite these consistencies, the horse motive is also erratic and unpredictable. But that is the point. The horse is wild and unbroken, far from home and carrying an unwanted passenger. Its only course is to run, and run it does.

Mazeppa does not dominate the horse but bends to its will. Nevertheless, the horse's subjectivity is bound with the hero in what Sibona calls a ‘centaur complex’.Footnote 56 This intersubjective union articulates the tension between the horse's speed and power and Mazeppa's helplessness to control or direct its path: ‘Each motion which I made to free/My swoln limbs from their agony/Increased his fury and afright’.Footnote 57 The relationship of control and passivity becomes more apparent if contrasted with familiar visual representations of the mounted military hero. For example, Jacques-Louis David's iconic series of paintings, Bonaparte Crossing the Grand Saint Bernhard Pass, depicts Napoleon as a conqueror (see Fig. 1).Footnote 58 His stance embodies power as he asserts dominance over his troops, nature and even history. David's portrait also evokes mutual respect between rider and horse as they visually appear in communion with their complementary postures. Yet, while they work toward a mutual goal, the rider is ultimately in control. Patricia Mainardi describes this symbolic gesture as a representation of rationality, with the rider's intellect controlling the horse's body.Footnote 59 While this relationship in David's image is hierarchical, there is also an implication of a shared purpose – to command and conquer.

Fig. 1 Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Bonaparte Crossing the Grand Saint-Bernhard Pass, 20 May 1800 (1801–02), Oil on canvas (Château de Versailles), photo: Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jacques_Louis_David_-_Bonaparte_franchissant_le_Grand_Saint-Bernard,_20_mai_1800_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

In contrast to the control portrayed in David's Napoleon, Géricault's representation of Mazeppa portrays a physically passive, pinioned hero (see Fig. 2). His naked body is stretched across the horse's back with his head tilted over its withers. Mazeppa's position has an erotic quality that further accentuates his vulnerability and passivity. His naked body is presented, as Vincenzo Patanè evocatively states, ‘in a sexual position, legs akimbo and open to any intrusion’.Footnote 60 Stated plainly, Mazeppa is open to receive. While Géricault represents the physical binds that tether Mazeppa to the horse, a chiaroscuro effect merges the foreground and background into a dark focal plane while illuminating Mazeppa's leg and chest and the horse's mane and tail, symbolically unifying the subjects on a metaphysical level. Although their bodies are physically connected, the horse has a will of its own and moves in a way that eludes Mazeppa's control. This is visually reflected in the inclined posture of the horse, which suggests forward momentum toward some goal outside the frame. Furthermore, as the horse evokes individual agency, Mazeppa's obscured face removes his defining features. His bodily position, therefore, promotes emotional expressivity and mood. Liszt's Mazeppa evokes the same aspects. As the steed races, it carries Mazeppa to realms beyond his control. All he can do is remain determined to survive, even if that means doing nothing.

Fig. 2 Théodore Géricault, Mazeppa, c. 1820, Oil on canvas, Private collection (Paris), photo: Wikimedia Commons. www.wikiart.org/en/theodore-gericault/the-page-mazeppa]

The Cry

Liszt's Mazeppa begins with a sudden shout on an embellished and idiosyncratic sonority of C-sharp–F–B-flat. This brief fortissimo ‘Cry’ gesture (see Ex. 2) contains a sense of musical realism, and refers to the third stanza of Hugo's ‘Mazeppa’ where ‘A shout’ [‘Un cri part’] marks the beginning of the Ride. Liszt returns to the Cry gesture at various moments and guises throughout his symphonic poem. At times it embellishes the Mazeppa theme, but it also often integrates more fully into the orchestral texture. As in Hugo's ‘Mazeppa’, the cry prompts the horse's gallop. In an extended programmatic commentary he wrote for Mazeppa (1854), Liszt reveals that the cry is associated with the birth-spark of inspiration, writing that ‘as man's first awakening to life is marked by the cry of the newborn, so a cry of suffering often marks the first stammering of the flaming spur of genius’.Footnote 61 Cast in this way, the Cry gesture adds an additional layer of meaning to the horse and its gallop: it both activates and comments on the erratic nature of genius.

Ex. 2 Liszt, Mazeppa, Cry Gesture, bar 1. Transcribed from Franz Liszt, Mazeppa, in Franz Liszt-Stiftung, Franz Liszt: Musikalische Werke, Serie I, Band 3 (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1909)

Liszt discusses the role of genius in modern art in his Berlioz essay. He writes that as art oscillates between ‘sterile’ and ‘outworn forms’ and progressive, evolving yet ‘still imperfect’ forms, the ‘agency of genius’ offers its beacon of divine progress to extend boundaries and push the development of new art.Footnote 62 Liszt's assessment reveals that genius is embodied within the artist, fusing inspiration with creative impulse. In a letter to George Sand from 30 April 1837, he implies that creative acts also involve both pleasure and pain:

There he [the artist] hears eternal, harmonious music whose cadence regulated the universe, and all the voices of creation are united for him in a marvelous concert. A burning fever then seizes him, his blood courses impetuously through his veins, filling his brain with a thousand compelling concepts from which there is no escape except by the holy labour of art.Footnote 63

The concept of genius is a key intertextual element connecting Liszt's Mazeppa to Hugo's poem. In the first stanza of section II, Hugo introduces the idea that genius, embodied as a passionate steed, carries the artist beyond ordinary human experience to the moons of Herschel, the rings of Saturn and past the pole adorned with the northern lights in a transcendent journey of suffering.Footnote 64 The speed and frantic pace of the horse, spurred by inspiration, transforms into a metaphor for flight. Liszt similarly evokes the effect of this transcendence in his Berlioz essay, but renders flight as the necessary result of being misunderstood and reviled. Being chosen by genius invites pain, reproach and envy as the cost of carrying that burden. Yet, the glory of surviving such an enduring, painful flame is a life that transcends death. Genius is thus inexplicable: spirit, inspiration, essence. It is fiery, hot, tempestuous. It is tranquil, sublime, eternal. Genius merges with the artist in a holy union and together make their escape ‘toward distant horizons’.Footnote 65 Genius belongs to artist-heroes capable of withstanding being pinioned to such a force and the fortitude to fly upon its pinions of freedom.

Pinioned

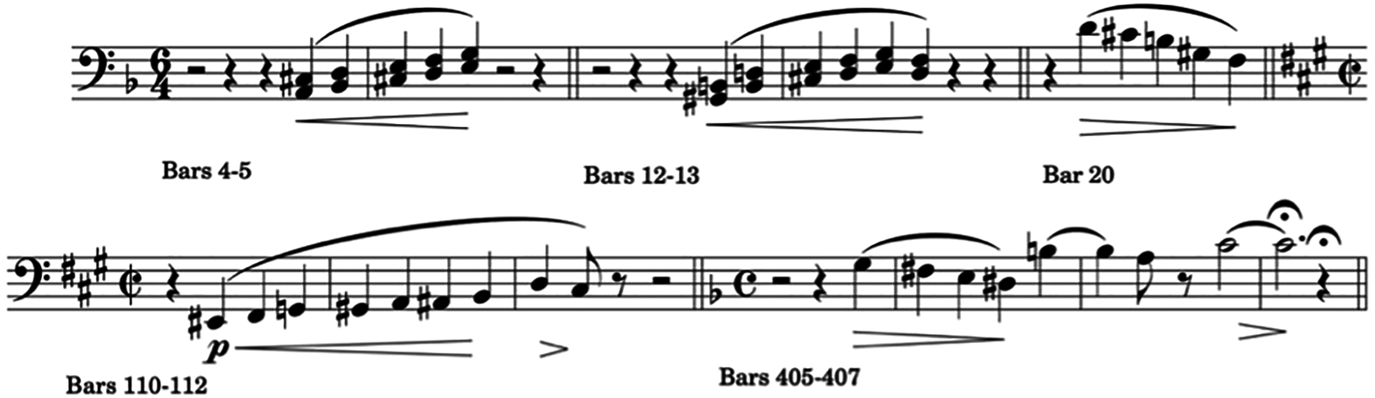

Becoming pinioned serves as an allegory for creative genius. To evoke this, Liszt introduces a new ‘Pinioned’ gesture in bar 4. Unlike the mimetic aspects of Horse motive and Cry gesture, this gesture reflects the emotive and expressive aspects of Mazeppa being bound to the horse (see Ex. 3). The Pinioned gesture consists of a flexible scalar pattern that exists in various permutations at key moments of the Ride. It is sometimes diatonic, chromatic, ascending or descending, and it frequently appears as transitional material to the Mazeppa theme. Furthermore, Liszt presents the motive in different instruments throughout the Ride, creating emotional valences. In the introduction, for instance, the gesture is initially stated by the clarinet and bassoon, suggesting delicate anguish. However, when the Pinioned gesture appears as transitional material in bar 108, it is stated in the woodwinds and doubled in the low strings, suggesting an even greater sense of anxiety. The symbolism of the pinioned gesture conveys the tethers that bind Mazeppa to the agent of his suffering: “Hold him silent and hold him down’.Footnote 66 Liszt amplifies the binding at the downbeat of bar 20. Here, an inverted statement of the gesture accompanies a short, dotted rhythm that foreshadows a main rhythmic component of Mazeppa theme. The pinioned gesture conveys a growing anxiety, and its presence in Mazeppa appears at moments of heightened tension. Thus, in the context of the Mazeppa myth, this gesture acts as an analogy for the always tightening binds.

Ex. 3 Liszt, Mazeppa, Variations of the Pinioned Gesture, bars 4–5; 12–13; 20; 110–112; 405–407. Transcribed from Franz Liszt, Mazeppa, in Franz Liszt-Stiftung, Franz Liszt: Musikalische Werke, Serie I, Band 3 (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1909)

Ex. 4 Liszt, Mazeppa, Mazeppa Theme bars 36–39. Transcribed from Franz Liszt, Mazeppa, in Franz Liszt-Stiftung, Franz Liszt: Musikalische Werke, Serie I, Band 3 (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1909)

Mazeppa's suffering exists on two planes: internal and external. The former is codified by an intense passivity and internal struggle that at once causes pain and signifies eventual triumph in death. This struggle, as Hugo explicitly states, only ties Mazeppa firmer to his steed: ‘And like a long serpent binds and multiplies/It bites and tangles’ [‘Et comme un long serpent resserre et multiplie/Sa morsure et ses nœunds’].Footnote 67 I will return to Mazeppa's internal suffering in more detail in my interpretation of the thematic transformations. For now, I will focus on Liszt's depiction of external struggle that centres on artistic rejection, another major theme in the Mazeppa intertexts.

Stanzas one and two of Hugo's poem describe Mazeppa's capture and the anticipation of the ride. He is ‘o'erpowered’ by the Count's subjects and unable to defend himself. His bonds keep him under control as the spirited horse also struggles by being ‘bound’ against its will. The imagery of Mazeppa's capture, fury and binding may be perceived as a symbol for Liszt's constant fight against his detractors in the so-called ‘War of the Romantics’. Within the context of Mazeppa, there are essential details that relate to the intertexts Liszt draws from. Liszt suggests that the artist-genius is almost required to struggle against his critics or, as he states in his Berlioz essay, the ‘Pharisees’, both as a necessity of pushing ahead and as a sign that his aesthetic transgressions are pointing toward the path of aesthetic enlightenment. The more his binds are tightened, the more confident he can be that the flight of genius will take the artist beyond the narrow vision of his critics. For Liszt, the holiness of the artist-genius derives from his mission to adapt the rules. The ‘professional musicians’ cling to the old, killing the spirit of progress:

To our regret we must admit that a secretly smoldering but irreconcilable quarrel has broken out between vocational and professional musicians. The latter, like the Pharisees of the Old Law, cling to the letter of the commandment, even at the risk of killing its spirit.Footnote 68

In contrast, vocational musicians honour the old patriarchs by creating ‘new forms for new ideas’.Footnote 69 As it relates specifically to Mazeppa, Liszt writes in his programmatic commentary that the cry of suffering ‘strikes fear’ and that as ‘people hasten to muzzle it: bonds of iron and garlands of flowers, chains of gold and tangles of thorns weave together to hold him immobile and keep him silent’.Footnote 70

Boulanger's painting Le Supplice de Mazeppa (1827), the direct inspiration for Hugo's poem, offers a visual representation of Mazeppa's binding (see Fig. 3). The chaotic scene conveys a juxtaposition between the energetic youth and the static elders, and marks the moment the Mazeppa myth developed into an allegory for creative genius. In other words, Boulanger establishes Mazeppa's binding as integral to his suffering and reflects the moment the artist is bound to genius. His painting also provides a visual metaphor for the misunderstood artist-genius struggling against the control of the old guard. Just as Mazeppa's sexual transgressions put him under the judgment of the elders, sending him on the ride of his life, the artist's aesthetic transgression put him under the judgment of his critics. The four elder men seated at the top of the frame observe the chaotic scene below, but they are almost completely covered by darkness. Their stillness and obfuscation contrasts with the movement of Mazeppa, the horse and, by extension, the captors. The light emanating from the horse surrounds Mazeppa, illuminating his power despite being pinioned. Mazeppa expresses heroic potential, highlighting his resistance to endure suffering. Moreover, in their attempt to punish Mazeppa, the captors only bind him tighter to the source of his eventual freedom, though he must endure incredible pain to earn that liberty. Those who judge, reject and criticize the powers of the artist-genius cannot be illuminated by its powerful light, but ironically, their rejection spurs the genius to create light they cannot see. Similar to Géricault's visual representation of Mazeppa and Liszt's allusion to the Pharisees, there are also religious connotations in Boulanger's painting, particularly the parallel symbolism of Christ being nailed to the cross as consequence of transgressing the old structures of earthly power with a new revelation. Binding, suffering and eventual death are integral to the artist-genius's purpose. In borrowing from Christian symbolism, these artists imbue Mazeppa's suffering with a messianic purpose. As Christ was crucified to redeem humanity, Mazeppa suffers to bring art to humanity. For both, their persecutors unwittingly unleash their greater power. Or as Hugo writes, and as Liszt explicitly quotes in his programmatic commentary, ‘his wild greatness is born out of his suffering’.Footnote 71

Fig. 3 Louis Boulanger, Le Supplice de Mazeppa (1827), Oil on canvas (Musée des Beaux-Artes de Rouen), photo: Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mazeppa_Louis_Boulanger.jpg

Thematic Transformations

Mazeppa is ultimately a character piece. Central to its genre-specific features is the focus on mood and emotion. This suggests the presence of an ‘aesthetic subject’, or an imagined musical persona related to another consciousness, subject or subjectivity.Footnote 72 Michael Spitzer asserts that subjective expression ‘amalgamates character and emotion’ into one being.Footnote 73 Taking this approach, a case may be made that in Liszt's Mazeppa, the expressive qualities of the Horse motive, Cry and Pinioned gestures of the introduction are also embodied within the hero. Indeed, the ‘Mazeppa’ theme and transformations illuminate the different facets of Mazeppa's heroic character – defiant, lamenting and persistent – all of which are mediated by interactions with external and internal forces.

The first brash statement of the Mazeppa theme in D minor at bar 36 (see Ex. 4), and transformation I in D minor at bar 69 suggest heroic defiance. In both statements, the theme is scored in brass, first in the trombones, then the trumpets, evoking military musical tropes that, on one hand, convey the power of his will to endure suffering and, on the other, foreshadow his future as Hetman, a position that requires the events of the Ride to fulfil.Footnote 74 Hugo's depiction of Mazeppa's capture not only focuses on despair, but also portrays a sense of wilful, even tempestuous power despite being bound: ‘With brow dropping sweat and with foam on each feature / His eyes redly glare’ [‘La sueur sur le front, l’écume dans la bouche, / Et du sang les yeux’].Footnote 75 Byron's poem more explicitly details Mazeppa's defiance. As the horse is set free, Mazeppa shouts curses to foes.

With sudden wrath I wrenched my head,

And snapped the cord which to the mane

Had bound my neck in lieu of rein,

And, writhing half my form about,

Howled back my curse … Footnote 76

But the ride narrative ultimately inverts militaristic imagery and expresses, rather, Mazeppa's will to survive. Layering the Horse motive and the Cry and Pinioned gestures of the introduction to the Mazeppa theme augments the symbolic associations of the hero. When these elements come to together, they characterize the artist-genius and render the emotion of being thrust into creating art. This is represented by the inclusion of an embellished Cry gesture in the strings at bar 36 as an accompaniment to the Horse motive. The result is a musical metaphor connecting inspiration and genius more explicitly to the hero. Liszt further heightens the fraught union between Mazeppa and the horse by incorporating a descending phrase of the Pinioned gesture at bar 46, connecting the hero and his binds. The first transformation at bar 69 contains much of the same aspects as the Mazeppa theme. The dotted rhythm is virtually intact and the main timbral quality remains largely in the brass, though the theme is doubled in the woodwinds. However, Liszt incorporates more fully into the orchestral texture the Cry gesture in the woodwinds, the result of which is a more lilting, dance-like quality. The overall effect of transformation I has changed from a defiant fight against the power of genius to movement in tandem with genius. Each gallop elicits a responding cry of inspiration in the artist-genius.

A new iteration of Mazeppa's heroic expression emerges in transformations II and III. Liszt prepares the shift with extensive transitional material from bars 98–121. Leading into bar 108, rapid chromatically ascending scales in the strings create a deceptive climax. This is immediately interrupted by a static C-sharp pedal in the strings followed by increasingly agitated ascending statements of the Pinioned gesture in the winds paralleled in unison by the low strings. There are several transitional passages like this in Mazeppa. Taking the whole of Liszt's symphonic music into account, Cormac proposes that transition passages imply musical subjectivities that may either ‘halt the progression and development of musical themes and structures’, or indicate where ‘one intertext and musical subjectivity can be interchanged for another’.Footnote 77 I hear the transitional musical material in Mazeppa along these lines and suggest, like Cormac, that Liszt deliberately incorporated musical fissures as a way to transition to the hero's various emotional states.

The agitation of the transition to transformation II gives way to an augmented lyrical statement of the Mazeppa theme in the distant key of B-flat minor at bar 122. Following this transformation, another transition passage appears in bar 155 that leads to second lyrical statement in B minor at bar 184. The move to B-flat minor marks a deep suffering within the piece, and foreshadows the apotheosis. The lyrical aspects of these two transformations point to subjectivity found in lyrical poetry. Drawing from Liszt's Berlioz essay, and emphasizing his discussion of differences and merits of epic, lyric and dramatic poetry, Cormac asserts that the lyric ‘limits its content to the inner world of a particular individual’ and therefore focuses on ‘moods and reflections rather than actions and events’.Footnote 78 This change to a lyrical style shifts the subjective expressivity from externally focused defiance to inwardly focused aguish, introspection and self-doubt. This shift mirrors stanzas six to nine of Hugo's poem in which Mazeppa suffers in ‘unconscious convulsion’ [‘la tête se brise’] and ‘his eyes gleam and flicker … his head sinks’ [‘Son œil s’égare, et luit … Sa tête pend’] as if struggling to remain conscious.Footnote 79 Secondary gestures accompany the shift and punctuate the musical texture, including an affective descending chromatic ‘Lament’ gesture, marked gemundo, or ‘moaning’ (see Ex. 5). Significantly, when this gesture appears, the Mazeppa theme is relegated to the background of the orchestral texture, making Mazeppa's introspection the focal point of his subjective experience. The Lament gesture continues until bar 154 when the agitated pinioned gesture serves, again, as transitional material to make Mazeppa momentarily aware of his binds to the back of genius.

Ex. 5 Liszt, Mazeppa, Lament motive, bars 135–144. Transcribed from Franz Liszt, Mazeppa, in Franz Liszt-Stiftung, Franz Liszt: Musikalische Werke, Serie I, Band 3 (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1909)

The third transformation is much like the second – an augmented statement of the Mazeppa theme interrupted by constant restatements of the Lament gesture. The sparse orchestral texture and augmentation of the Mazeppa theme to the point of its near obfuscation create an illusion of time slowing down and internal space opening up. The second violins retain the horse-like triplet figure, but the effect creates an aural distance between horse and hero. For a moment, Mazeppa mentally retreats deeper from the struggle of their merged subjectivity, allowing space to concentrate, as Saint-Saëns aptly writes, ‘on the man who suffers and who thinks’.Footnote 80 This is when Mazeppa reaches the nadir of his suffering. He fights against his own thoughts as he questions whether he has the strength to endure or if his freedom is worth the pain. As a part of Liszt's extended allegory for the plight of the artist-genius, Mazeppa's inner suffering mirrors the anguish artists often feel midway through the creative process. Their only defence against the temptation to abandon the project is the perseverance to see it through to the end. Likewise, Mazeppa cannot act to alter his fate while passively bound to the steed, but his heroic stature nevertheless shows his inner resolve to hold on as he is carried always, away.

Coming out of this dark night of the soul, the defiance and resolve to see the journey through returns in transformations IV, V and VI. Mazeppa's interior struggle closes with a martial-like transition back to the external realities of the Ride in bar 232. The Horse motive returns to the foreground with the arrival of the fourth transformation in D minor. The hero and horse continue on this track for the remainder of the Ride. In transformation V at bars 263–332, the Mazeppa theme is restored to its initial statement in the brass, punctuated by the ever-present gallop in the strings. This suggests a reinvigoration of Mazeppa's resolve to survive. The sixth and final transformation includes colourful ‘Cossack’ ornamentation that infers both the arrival in Ukraine and the foreshadowing of Mazeppa's triumph as Hetman. The horse motive transforms into a uniform expression that complements the hero's (future) martial presence. If there was a moment in the Ride where Mazeppa could possibly be Napoleonic, this would be it. Perhaps the promise of genius strengthens his resolve since, at this moment, his subjective expression reflects dynamism, control and power. However, the transformation does not evoke a sense of closure. Rather, the promised victory of the sixth transformation must be accompanied by death.

Death Passage

The theme of death-in-life is present throughout the development of the Mazeppa myth.Footnote 81 Byron's framing narrative reinforces the theme that new life can come amidst certain death. In Géricault and Boulanger, references to the pietà in Mazeppa's stretched-out body imply an eventual resurrection. Both sections of Hugo's poem end with an image of death. In the first section Hugo writes,

Behold him [Mazeppa] there naked, blood-stained and despairing,

All red, like the foliage of autumn preparing

To whither and fall.

Voilà l'infortuné, gisant, nu, misérable,

Tout tacheté de sang, plus rouge que l’érable

Dans la saison des fleurs.Footnote 82

In the second section, Hugo truncates Mazeppa's death into a single line: ‘He totters – falls lifeless – the struggle is ended’ (‘Enfin le terme arrive … il court, il vole, il tombe’).Footnote 83 Liszt's conclusion to the Ride section slows in order to explore the emotional contours of this death. Rather than a rousing continuation of the martial trope in the final thematic transformation, Liszt ends with an immediate decrease in tempo (poco ritenuto) and a focus on the Pinioned gesture, heard in the lower woodwinds and doubled in the strings at bars 383–402. After six transformations (and three days!), Liszt brings horse and rider to the brink. The Horse motive virtually disappears signalling the horse's death and ending its merged subjectivity with the rider: ‘The horse dies to the cries of a thousand birds of prey’ (‘Le cheval tombe aux cris de mille oiseaux de proie’).Footnote 84 What follows is an andante, quasi-recitative ‘Death’ passage at bars 403–435 that corresponds to the final stanzas of Section I of Hugo's poem. Liszt creates feelings of ambiguity and uncertainty in the Death passage through sparse orchestral texture and the fragmentation of the Pinioned gesture and Mazeppa theme. He also adds a new lamenting ‘Funereal’ gesture that sequentially ascends with each statement (see Ex. 6). The Funereal gesture exemplifies the slow, forward-moving steps of a dirge, and refers to Mazeppa's own death procession of birds that follow as he nears death:

All hasten to swell the procession so dreary,

And may a league from the holm or the eyrie

They follow this man.

Tous viennent élargir la funèbre volée!

Tous quittent pour le suivre et l'yeuse isolée,

Et les nids du manoir.Footnote 85

Ex. 6 Liszt, Mazeppa, Funereal Gesture, bars 411–412. Transcribed from Franz Liszt, Mazeppa, in Franz Liszt-Stiftung, Franz Liszt: Musikalische Werke, Serie I, Band 3 (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1909)

As the Death passage reaches its end, a five-note descending statement of the Pinioned gesture in bars 405–406 concludes with intermittent statements of the Funereal gesture in the strings and doubled by the bassoons. Fragmented solo statements of the Mazeppa theme in the second flute and clarinets punctuate the two gestures at bars 409–410 and 415–416. The closing bars of the Death passage evoke Mazeppa's physically broken body through the fragmentation of his theme.Footnote 86 Rather than resolve, each of these musical fragments unravel to the point of near silence, leading to a genuine doubt about Mazeppa's state after his efforts to survive.

Liszt lingers on the uncertainty of death in these passages to emphasize Mazeppa's capacity for suffering. Death cannot be glossed over. Indeed, in the Mazeppa myth, death is necessary to find life. When the artist-genius concludes the creative process, there is a metaphoric death as the inspiration that sparked the work dies. Moreover, the constant push against critics and even self-doubt leaves the artist exhausted and almost broken – hardly a triumphant ending. At a broader level, the artist's literal death might be the price for public recognition. Drawing from a messianic metaphor, Liszt writes in his Berlioz essay that the artist is destined to suffer reproach and misunderstanding for the sake of the art he gives to the world: though the artist leads ‘a tortured, hunted life, at death they leave behind their works, like a salutary blessing’.Footnote 87

Pinions: The Flight of Genius

The March

Whereas the Ride illustrates the experience of creating art as being pinioned to genius, emphasizing suffering, persistence and death; the March explores the same experience of genius as flying on pinions of freedom and triumph. The March begins with a trumpet Fanfare in B major (see Ex. 7). The evocation of this moment suggests a symmetry in imagining Mazeppa mounted once more, but this time for his coronation. There is a desire to hear the March as a reflection of the final line of Hugo's poem:

Yet mark! That poor sufferer, gasping and moaning,

To-morrow the Cossacks of Ukraine atoning,

Will hail as their king

Eh bien! ce condamné qui hurle et qui se traine,

Ce cadavre vivant, les tribus de l'Ukraine

Le feront prince un jourFootnote 88

Ex. 7 Liszt, Mazeppa, Fanfare, bars 437–443. Transcribed from Franz Liszt, Mazeppa, in Franz Liszt-Stiftung, Franz Liszt: Musikalische Werke, Serie I, Band 3 (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1909)

However, the Cry gesture in the strings accompanies the triumphant Fanfare voiced by the brass, as if to signal a restatement of the birth pangs of inspiration. While the close of the Ride section implied the triumph found in suffering, the March begins by commenting on the suffering that accompanies triumph. Like Hugo's two concurrent retellings of Mazeppa's wild ride (one representational, one mythical), Liszt also uses the second section of his work to explore the other side of genius – freedom. In Hugo's poem, Pegasus replaces the horse, turning the ride into a flight. Though bound to Pegasus, Mazeppa still moves at the whims of his mount. The hero ‘Traverses soaring on fiery pinions, / All possible fields and the worlds of the soul / Drinks from the eternal river’ (‘traverse d'un vol, sur tes ailes de flame,/Tous les champs du possible, et les mondes de l’âme;/Boit au fleuve éternel’).Footnote 89 The flight of genius takes the artist beyond the boundless horizon of the Ride and transforms the landscape into an ideal horizon where genius takes Mazeppa to the moons of Herschel, the rings of Saturn and past the pole adorned in northern lights.

The expressions of victory and freedom are obvious throughout the March. The two new themes are uncomplicated. The first, in D major, is outwardly regal and evokes an image of the archetypal rider on his noble steed (see Ex. 8). Like the Mazeppa theme of the Ride, this new ‘Martial’ theme is heard in the brass and contains the familiar rhythmic qualities of the main theme. The strings, again, evoke a horse, but the headlong gallop of the Ride transforms into the rider controlling the steed. The second theme in D minor (see Ex. 9) evokes Eastern European sounds through ornamentation and instrumentation. Like the embellishments to transformation VI of the Mazeppa theme, this ‘Cossack’ theme musically reflects the prophecy of Mazeppa as the future Hetman. His victory is assured.

Ex. 8 Liszt, Mazeppa, Marziale Theme, bars 466–468. Transcribed from Franz Liszt, Mazeppa, in Franz Liszt-Stiftung, Franz Liszt: Musikalische Werke, Serie I, Band 3 (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1909)

Ex. 9 Liszt, Mazeppa, Cossack Theme, bars 500–503. Transcribed from Franz Liszt, Mazeppa, in Franz Liszt-Stiftung, Franz Liszt: Musikalische Werke, Serie I, Band 3 (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1909

Amidst the pomp of the themes, Liszt momentarily returns to the persistent rhythmic qualities, speed and movement of the wild steed from bars 550–558. Given the context, this reference to the Ride appears out of place, even unsettlingly so, given the suffering they recall. In approaching the final bars of the symphonic poem, Liszt surprises the listener again with a brief but structurally important reintroduction of the Mazeppa theme along with the other complementary motives of the Ride. I consider this the moment of apotheosis, an archetypal thematic trope that infers monumental admiration and glorification.Footnote 90 However, what follows destabilizes such glorification. The closing lines of Section II of Hugo's poem reveal that the allegorical celestial rider cries in terror as the pursuit of genius continues unrelentingly:

Pale, exhausted, [mouth] gaping, under your flight which overwhelms him

He bends in fear;

Every step you take seems to dig his grave.

Finally, the end comes … he runs, he flies, he falls,

And rises king!

Pâle, épuisé, béant, sous ton vol qui l'accable

Il ploie avec effroi;

Chaque pas que tu fais semble creuser sa tombe.

Enfin le terme arrive … il court, il vole, il tombe,

Et se relève roi!Footnote 91

Liszt's refiguring of Mazeppa similarly bears the mark of always suffering. In the final bars, he reintroduces the Horse motive, an augmented statement of the Pinioned gesture and the final, truncated transformation of the Mazeppa theme from bars 578ff. Following this statement of the Mazeppa theme, the Funereal gesture from the Death passage recurs one last time. To accompany the Mazeppa theme with evocations of binding, especially in the context of triumph, calls into question the characteristics of that triumph. In the work's coda, Liszt builds toward a rousing conclusion in D major before suddenly shifting to B-flat minor just before the piece ends. Although a short moment within the context of the entire work, this chord stands out against the tonic. This surprising B-flat chord, along with its placement as part of the triumphant March, recalls the depths of introspective suffering heard in the second thematic transformation of the Ride, acting as a lamp into Mazeppa's inner torture.

The apotheosis and the coda therefore make it possible to hear the Ride and the March concurrently. If the closing of the March is reminiscent of the dying horse and Mazeppa's broken body of the Ride, then I may infer that in this moment suffering and transcendence intersect. Liszt's insistence on returning to these moments suggests that Mazeppa's suffering persists even in triumph. Returning to the messianic structure of the Mazeppa myth, it is possible to see the March as a recognition of the power of suffering in triumph. Christ's crucifixion is entwined with the idea that the cross symbolizes both suffering and triumph. From this perspective, Mazeppa's ordeal is an act of triumph, not contingent on his release and rescue. The restatement of the Mazeppa theme and transformed Pinioned and Funereal gestures reveal that Mazeppa has only reached his triumphant end in suffering. And like Christ, Mazeppa could not achieve transcendence without being bound to his version of the cross. The parallels between Christ and genius are found in the patience to bear a passion beyond imagining. Similarly, the artist must endure the ride of genius to reveal the potential of their art. The recursive patterns of victory in suffering and suffering as victory found in Liszt's Mazeppa imply that the experience of the artist-genius repeats and can never be finished. Liszt hints at this possibility in the final three bars of the work, where he ends where he began with the Cry gesture. The artist's struggle with being pinioned to genius will continue indefinitely. The Ride will always start over again with the next spark of inspiration. Away, away!

Conclusion

There is something deeply poignant about Liszt's expression of vulnerability in Mazeppa. The metaphor of the bound-yet-free hero resonated with Liszt throughout his career as both a performer and composer. In the figure of Mazeppa, he found a hero who could convey his own struggles as a misunderstood artist fighting for credibility among the conservative establishment. The varied intertexts that comprise the Mazeppa myth form an elaborate allegory for the artist pinioned to genius who, by that same binding, becomes artistically freed upon the pinions of genius's wings. The subjectivity of the hero expressed in Mazeppa gives shape to the emotional experience of the artists-genius: defiant, anguished, rejected, pained, euphoric, triumphant, defeated, resigned to die and reborn to start the creative cycle again. Mazeppa's relationship to the horse embed all of these meanings, beginning with the mimetic cliché of galloping. Analysing these pictorial effects alongside their intertextual and cultural references brings to fore an image of the artist suffering to the whims of inspiration and the labour of genius.

The impetus behind this article began with a simple question: what can be learned by taking the extramusical content of Liszt's symphonic poems as seriously as the score? Since its premiere, Mazeppa has been dismissed as a work with little to offer beyond repetitive, unrelenting mimetic tropes. But Mazeppa is more than its music. It intertwines musical topics with broader extramusical associations drawn from a rich cultural history. Using Cormac's and Taylor's discussions of intertextuality and musical subjectivity, I have built an interpretation that connects the various threads of cultural history – from historical accounts to poetry and painting – to the musical gestures, motives and themes present in Mazeppa. My purpose is to take Liszt up on his call to interpret programme music as the expression of ‘the approximation of certain ideas, the affinity of certain figures, the separation or combination, juxtaposition or fusion of certain poetic images’.Footnote 92 Liszt argues programme music is not merely the result of the musical representation of a text's meaning, but it also maps the composer's subjective experience of the text onto his creative work. Liszt's compositional approach, as I have argued, aligns with Cormac's interpretive framework that ties extramusical associations to musical subjectivities by merging musically mimetic tropes with the subjectivity of the work's protagonist.

Although approaching Mazeppa through the lens of musical subjectivity could yield boundless interpretations, Liszt intends that the programme keeps the interpretation within a set of ideas, concepts and feelings close to the meaning the composer seeks to express. Liszt's effort to fuse juxtaposed images into his music provides a means to connect seemingly disparate elements within a work into one musical subject. The willingness to understand Liszt's work on his own terms could – perhaps ironically – offer new interpretations into subjective experiences he sought to embed in his work. I therefore suggest that analysing his other heroic symphonic poems through intertextuality and musical subjectivity could offer new insights into how Liszt emulated his heroes. Listeners certainly do not need to agree with Liszt's claims about his music to enjoy it or derive meaning from it. Likewise, one listener's subjective experience with a work cannot compel another listener to hear the piece the same way. Whether critics hear Liszt's Mazeppa as empty noise, my assertion is that in considering the programme and the cultural history of the myth, listeners may find meaning that is far richer than its reputation. Perhaps listeners may even resonate with the expression of artistic vulnerability in Mazeppa.