Introduction

Liberia's c. 4.33 million ha of forest (Christie et al., Reference Christie, Steining, John and Peal2007) are distributed within the two largest remaining areas of continuous forest in West Africa (Kunkel, Reference Kunkel1965; Gatter, Reference Gatter1997) and contain c. 40% of the remaining Upper Guinea forests. The country potentially hosts as yet unknown species and lies within a conservation priority ecoregion (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Pimm and Joppa2013). Moreover, it has high levels of biodiversity and falls within the richest 5% of land area for threatened amphibians, birds and mammals (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Pimm and Joppa2013), including the West African chimpanzee Pan troglodytes verus.

Junker et al. (Reference Junker, Blake, Boesch, Campbell, du Toit and Duvall2012) found that, within West Africa, Liberia has the most suitable environmental conditions (SEC) for chimpanzees, a measure defined by environmental and human impact variables, including human population density, poverty, distance to roads, precipitation, temperature, distance to rivers, forest cover and distance to nearby forest. Although there has been a 3.94% decrease in SEC in Liberia since the 1990s, this is relatively small compared to other countries in the region (e.g. Côte d'Ivoire, 18.34%; Ghana, 16.45%; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Junker, Boesch and Kühl2012). Liberia still has relatively large remnants of suitable habitat for chimpanzees and other species, which should make the country a conservation priority in West Africa. The long-term survival of Liberia's wildlife populations may be threatened by hunting (Anstey, Reference Anstey1991; CEEB, 2003–2004; Greengrass, Reference Greengrass2011; Bene et al., Reference Bene, Gamys and Dufour2013), unsustainable land-use management (Humle & Kormos, Reference Humle, Kormos, Matsuzawa, Humle and Sugiyama2011) and the illegal pet trade (Verschuren, Reference Verschuren1983; Junker, pers. obs.).

Anstey (Reference Anstey1991) estimated the annual wildlife harvest in Liberia at 150,000 t, which is one of the highest per capita offtake rates in Africa. More recent bushmeat surveys estimated the total income generated from meat sales in Monrovia in < 1 year at > USD 8 million (CEEB, 2003–2004). Hunting has been reported as one of the main threats to wildlife, even near officially protected areas (Greengrass, Reference Greengrass2011; Bene et al., Reference Bene, Gamys and Dufour2013). Quantitative data on offtake rates of chimpanzees are rare but chimpanzees appear to be hunted country-wide and mostly opportunistically (Lormie et al., unpubl. data). However, in some regions hunters may specialize in killing chimpanzees. For example, a bushmeat survey reported 58 chimpanzee carcasses in a commercial hunting camp near Sapo National Park despite traditional beliefs in this area that supposedly prohibit the consumption of chimpanzee meat (Greengrass, Reference Greengrass2011).

Since the end of the civil war, in 2003 (Christie et al., Reference Christie, Steining, John and Peal2007), logging and mining companies have returned to Liberia to profit from what remains of the country's rich natural resources. Extraction of timber and minerals is expected to generate the majority of the country's gross domestic product in the next 15 years (MPEA, 2010). According to data provided by the Forestry Development Authority (MPEA, 2010) > 20,000 km2 of forest have been assigned as forestry concessions and awarded to international and local investors since the ban on timber exports was repealed in 2006. Since 2010 logging companies have used legal loopholes to issue > 60 so-called Private Use Permits, which are subject to virtually no sustainability requirements; these alone account for almost half of Liberia's remaining primary forest (Global Witness et al., 2012).

To gain a quantitative measure of the effects of these threats on Liberia's wildlife populations and to propose mitigation measures to conservationists and policy-makers, accurate and up-to-date information on the distribution and abundance of wildlife populations and the severity of local threats is required (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Pimm and Joppa2013). However, despite its biological wealth there is a lack of rigorous and quantitative biological datasets for Liberia. This situation can largely be ascribed to the years of civil conflict (1989–1997 and 2002–2003), which prohibited efforts to conduct biological surveys. Most information on Liberia's chimpanzee population, for example, comes from short-term or multi-species rapid assessments (Barrie et al., Reference Barrie, Zwuen, Kota, Lou, Luke, Hoke, Demey and Peal2007) or unsystematic field observations (Coe, Reference Coe1975; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Williamson and Carter1983; Verschuren, Reference Verschuren1983). This paucity of scientific data led Kormos et al. (Reference Kormos, Boesch, Bakarr and Butynski2003) to suggest a country-wide chimpanzee survey as a prerequisite for chimpanzee conservation in Liberia.

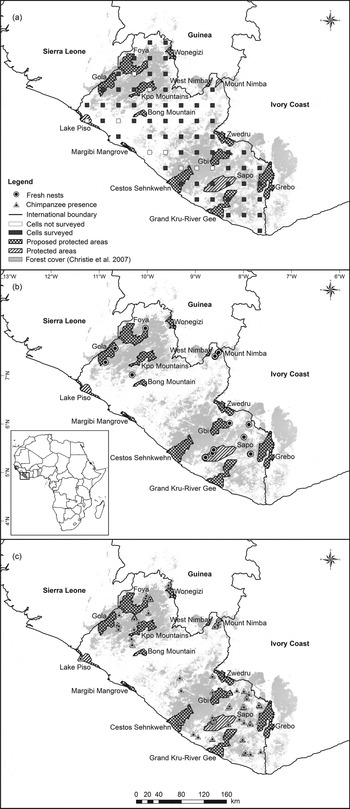

Such data, for chimpanzees as well as other species, are essential for the location and delineation of conservation priority areas (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Kuehl, Diarrassouba, N'Goran and Boesch2011; N'Goran et al., Reference N'Goran, Boesch, Mundry, N'Goran, Herbinger, Yapi and Kühl2012, Reference N'Goran, Kouakou, N'Goran, Konaté, Herbinger and Yapi2013). To promote the establishment of a network of protected forest areas, the Forestry Development Authority committed to ‘establishing a biologically representative network of protected areas covering at least 30% of the existing forest area’ (MFA, 2003). At the time of our study there were only three protected areas in Liberia, Sapo National Park, Mount Nimba Nature Reserve and Lake Piso Community Reserve (Environmental Protection Agency, 2004), representing c. 6% of the country's total forest cover (estimated based on Christie et al., Reference Christie, Steining, John and Peal2007; Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1 Liberia, showing (a) the locations of cells surveyed, (b) locations of fresh chimpanzee nests, which were marked and revisited to estimate nest decay rate, and (c) distribution of all signs of chimpanzee presence encountered on both transects and recces over the entire study period. The rectangle on the inset in (c) indicates the location of Liberia in Africa.

To provide quantitative and up-to date information as a platform for conservation decision-making (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Kuehl, Diarrassouba, N'Goran and Boesch2011; N'Goran et al., Reference N'Goran, Boesch, Mundry, N'Goran, Herbinger, Yapi and Kühl2012) we conducted the first systematic survey of chimpanzees and large mammals in Liberia during August 2010–May 2012. We used traditional line-transect methods (Buckland et al., Reference Buckland, Anderson, Burnham, Laake, Borchers and Thomas2001) to estimate the distribution and abundance of chimpanzees, the distribution and diversity of large mammal species, and the distribution and abundance of anthropogenic threats related to hunting, logging, mining, extraction of non-timber forest products (NTFPs), and agriculture.

Methods

During January 2011–May 2012 we surveyed line transects placed systematically across Liberia for chimpanzee nests, presence of large mammals and signs of anthropogenic threats. Prior to the survey we marked and revisited fresh chimpanzee nests in various parts of the country to estimate nest decay rate. We used Distance v. 6.0 (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Laake, Rexstad, Strindberg, Marques and Buckland2009) to estimate chimpanzee abundance, and a geographical information system (GIS) to plot distribution of chimpanzees, diversity of large mammals and encounter rates for hunting sign.

Nest decay study

During August–December 2010 we walked reconnaissance paths (hereafter recces) to locate fresh chimpanzee nests (White & Edwards, Reference White and Edwards2000), making an effort to obtain a representative sample across the entire country. To increase our chances of finding fresh nests we used information obtained from interviews with local people and from the distribution of SEC in Liberia (Junker et al., Reference Junker, Blake, Boesch, Campbell, du Toit and Duvall2012). While walking recces we marked all fresh nests observed; we revisited each nest only once, to record whether the nest had decayed (Laing et al., Reference Laing, Buckland, Burn, Lambie and Amphlett2003; Kouakou et al., Reference Kouakou, Boesch and Kuehl2009). Our data covered different time intervals between the time of detection and the revisit. Nests were considered decayed when they were no longer visible.

Line-transect survey

We used ArcMap v. 10.0 (ESRI, Redlands, USA) to systematically locate 68 9 × 9 km sampling cells across Liberia (Fig. 1a). We used the survey grid developed for the West African region, available on the A.P.E.S. (Ape Populations, Environments and Surveys) Portal (Kühl et al., Reference Kühl, Williamson, Sanz, Morgan and Boesch2007), as a model. Based on observations made during the nest decay study we excluded one cell that fell within a 10 km radius of a town with > 100,000 inhabitants as we were confident that there were no chimpanzees in this area. We also excluded cells that extended across international boundaries, for logistical reasons.

The distance between the centre points of neighbouring cells was 36 km. Cells were further divided into nine 3 × 3 km sampling blocks. We placed one line transect in each centre block and one in a second, randomly chosen block. This yielded a total of 136 transects.

We followed IUCN best practice guidelines (Kühl et al., Reference Kühl, Maisels, Ancrenaz and Williamson2008) and Murai et al. (Reference Murai, Ruffler, Berlemont, Campbell, Esono and Agbor2013) for collecting data. Along transects we recorded all chimpanzee nests, perpendicular distances from individual nests to the transect line (Buckland et al., Reference Buckland, Anderson, Burnham, Laake, Borchers and Thomas2001), nest decay stage and the first direct or indirect sign of other large mammals. We also recorded all signs of human presence related to hunting (empty cartridges, gunshots, poachers’ camps and snares), commercial and artisanal logging and mining, extraction of NTFPs, and agriculture.

Statistical analysis

We used logistic regression to estimate the probability of nest decay as a function of time (nest age measured in days). We fitted three logistic models to our data, as suggested by Laing et al. (Reference Laing, Buckland, Burn, Lambie and Amphlett2003). All models were run in R v. 2.15.1 (R Development Core Team, 2012).

We used Distance to estimate chimpanzee population size, based on a nest production rate of 1.143 (Kouakou et al., Reference Kouakou, Boesch and Kuehl2009), a proportion of nest-builders of 0.83 (Plumptre & Cox, Reference Plumptre and Cox2006) and an estimate of the nest decay rate derived from our nationwide nest decay study. We calculated density estimates, with associated analytical coefficients of variation and 95% confidence intervals (Buckland et al., Reference Buckland, Anderson, Burnham, Laake, Borchers and Thomas2001).

We also estimated separately the size of the chimpanzee populations in Sapo National Park and Grebo and Gola National Forests from data collected during surveys conducted in 2009 (N'Goran, unpubl. data), 2012 (Kouakou, unpubl. data) and 2010–2012 (Hillers, unpubl. data), respectively. Survey efforts for these areas were 44, 178.27 and 118.3 km, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1). We fitted a global detection function including data from all three surveys, where we post-stratified according to survey area.

To calculate population estimates for these three sites we used the nest decay rate of 100.65 days calculated for Sapo National Park (N'Goran et al., Reference N'Goran, Kouakou and Herbinger2010). We used the same nest decay rate for abundance estimations for Grebo and Gola National Forests as these areas had similar vegetation and climate conditions to Sapo National Park. We used the same nest production rate and proportion of nest-builders as for the analysis of the nationwide data.

We used the inverse distance weighted method in the spatial analyst toolbox in ArcMap to interpolate the population density of chimpanzees nationwide, based on transect estimates calculated by Distance. We also interpolated encounter rates for large mammal species and hunting sign. We separated hunting signs into two categories: (1) snare-hunting (active and inactive snares), and (2) gun-hunting (poachers’ camps, empty cartridges, and gunshots heard).

We used a Spearman correlation test and the function rcorr from Hmisc (Harrell & Dupont, Reference Harrell and Dupont2013) in R to compare the spatial distribution of nest abundance and mammal species diversity.

Further information about our distance analysis is provided in Supplementary Material 1.

Results

Nest decay

We marked and revisited 165 fresh nests (Fig. 1b), at intervals of 6–310 days. We found 14 nests in old secondary forest, 151 nests in primary forest and none in palm trees, and therefore we did not estimate nest decay rate for different habitat or tree types. The log-transformed model overestimated nest decay time (295 days) by fitting an elongated tail, and the reciprocal model did not converge. We thus chose the left-truncated model as it fitted our data best (residual deviance = 160.23, df = 148, P < 0.001). It yielded an estimated mean time to decay of 164.38 ± SE 0.32 days; Supplementary Fig. S2).

Chimpanzee distribution and abundance

We were able to survey 116 of the 136 transects. Two cells were inaccessible for logistical reasons. We were denied access to seven cells by local communities (Fig. 1a). For similar reasons we could not walk the full length of some transects. The effective survey effort was 326.18 km. The mean nest encounter rate was 0.342 km−1 (range 0–18) and involved 113 nests.

Chimpanzees were widely distributed across Liberia (Fig. 1c). We found the majority of signs of chimpanzee presence within the two largest forest blocks: (1) in the south-east, spanning Maryland, Grand Gedeh, Grand Kru, Rivercess, River Gee and Sinoe counties, and in and near East Nimba Nature Reserve in northern Nimba county, and (2) in the north-west, including Gbarpolu and Lofa counties and the Lake Piso Community Reserve on the coast in Grand Cape Mount county (Fig. 2a). Our estimate of the population of Liberian chimpanzees, based on the nationwide survey and excluding protected areas, was 5,045 individuals (95% CI = 2,974–8,559), which translates to a country-wide density of 0.047 (95% CI = 0.028–0.08) chimpanzees per km2. Analysis was based on 108 nest observations in a total area of 106,970.49 km2 (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. S3; Supplementary Tables S1 & S2).

Fig. 2 Liberia showing (a) chimpanzee population densities, (b) species richness of large mammals, interpolated from transects, (c) snare-hunting (active and inactive snares), and (d) gun-hunting sign, (poachers’ camps, gunshots, empty cartridges) encounter rates, interpolated from transects. GIS data on market locations were provided by USAID GEMS, major road shapefiles were provided by USAID (extracted from Digital Chart of the World and re-aligned with Landsat) and country and county capitals were extracted from Digital Chart of the World.

Table 1 Estimates of West African chimpanzee Pan troglodytes verus populations in unprotected, protected and proposed protected areas in Liberia (Fig. 1), based on comparable systematic surveys conducted during 2009–2012 using line-transect distance sampling.

1 Population estimate excludes the non-surveyed mining areas within the park

2 Population estimate excludes the non-surveyed north-west of the proposed protected area

Population estimates for Sapo National Park and Grebo and Gola National Forests were 1,517 (95% CI = 1,033–2,228), 352 (95% CI = 214–578) and 94 (95% CI = 39–225) individuals, respectively. These calculations were based on a total of 277 nest observations (Sapo = 175; Grebo = 59; Gola = 43; Supplementary Fig. S4; Supplementary Tables S3 & S4). We estimated the total population of chimpanzees in Liberia to be 7,008 (95% CI = 4,260–11,590; Table 1).

Mammal diversity and anthropogenic threats

We observed signs of presence of 27 species of large mammals along 92 transects. We encountered 0–9 species along each transect (mean = 2.439; Supplementary Table S5). Diversity of large mammals was highest in Grand Gedeh, River Gee, Grand Kru, Nimba and Sinoe counties in the south-east and in Gbarpolu and Lofa counties in the north-west (Fig. 2b). There was a positive correlation between diversity of large mammals and abundance of chimpanzee nests recorded on line transects (Spearman correlation: R = 0.42; P < 0.001).

Hunting was the most frequently encountered anthropogenic threat on transects. Encounter rates for signs of hunting, logging, mining and NTFP extraction were 1.32 ± SD 2.404 km−1 (range 0–14), 0.126 ± SD 0.593 km−1 (range 0–5.667), 0.278 ± SD 0.919 (range 0–5), and 0.035 ± SD 0.155 km−1 (range 0–1), respectively. We encountered 0–42 signs of hunting per transect (n = 441). Snare-hunting was most common in the non-forested areas of central Liberia and Montserrado and northern Lofa counties and was approximately associated with the spatial distribution of daily and weekly agricultural markets (Fig. 2c). The highest encounter rates for signs associated with gun-hunting were recorded on transects in the forested areas of Lofa, Grand Gedeh and River Gee counties (Fig. 2d).

The majority of the signs of mining and logging that we encountered were artisanal. We encountered 0–15 signs of mining per transect (n = 93) and these were most abundant in the west (Gbarpolu and rural Montserrado counties) and in the south-east (Sinoe, Grand Gedeh and Grand Kru counties). We encountered signs of logging (n = 44; range 0–17) and extraction of NTFPs (n = 7; range 0–3) relatively infrequently. The total length of agricultural clearings recorded on transects was 30.21 km, which represents 9.4% of the total length of transects surveyed.

IUCN SSC A.P.E.S. database

All data collected during this study are stored in the IUCN SSC A.P.E.S. database (Kühl et al., Reference Kühl, Williamson, Sanz, Morgan and Boesch2007). A.P.E.S. serves to centralize and standardize all ape survey information, providing a universal platform from which these data may be accessed in accordance with a data access and release policy.

Discussion

Based on our survey results we estimate a population of > 7,000 chimpanzees in Liberia. Chimpanzees were found across much of the country, with the highest relative densities in the two forest blocks in the south-east and north-west, in which we also found the highest diversity of large mammals. We observed chimpanzee nests predominantly in primary forest and rarely in human-disturbed habitats. This is comparable with results from a similar nationwide survey in Equatorial Guinea (Murai et al., Reference Murai, Ruffler, Berlemont, Campbell, Esono and Agbor2013), which indicated a strong negative relationship between ape abundance and agricultural mosaic habitat. In Guinea and Sierra Leone, however, researchers have frequently found chimpanzee nests in secondary forest and agricultural mosaics (WCF, unpubl. data; Brncic et al., Reference Brncic, Amarasekaran and McKenna2010). These country-specific differences may be attributable to environmental factors such as resource abundance and hunting pressure. They may also be influenced by geography and habitat structure: chimpanzees in Liberia are exclusively forest-dwelling, whereas some chimpanzee populations in Sierra Leone and most populations in Guinea live in dry forests and in savannah–woodland mosaics and may thus be more adaptable with regard to their habitat requirements.

Liberia harbours the second largest and probably one of the most viable chimpanzee populations in West Africa (Table 2), making it a regional conservation priority. However, chimpanzees and other mammals are increasingly threatened by widespread hunting, as well as the habitat destruction that will inevitably result from proposed plans for large-scale timber and mineral extraction (MPEA, 2010). Our results form the basis for systematic conservation planning and may aid in implementing effective site-specific conservation actions to maintain current levels of diversity of large mammals and ensure the long-term persistence of Liberia's chimpanzee population.

Table 2 Population estimates for wild-living chimpanzees in West African countries.

* This survey included only the Fouta Djallon region. We therefore assume that the population for the entire country was > 17,751.

More than 70% of chimpanzees and some of the most species-diverse large mammal communities in Liberia occur outside fully protected areas (Fig. 2a,b), which include only c. 6% of the country's forests. In 2003 the Liberian government agreed to increase the extent of the protected area network to include at least 30% of the forests (MFA, 2003). Our study provides crucial information for site prioritization and selection in this ongoing process. Rapid implementation of full protection status of selected areas is necessary as there already appear to be multiple overlaps between proposed protected areas and future mining and forestry projects (Supplementary Fig. S5; MPEA, 2010).

The majority of mineral and timber extraction activities encountered were artisanal. However, since the end of the civil war in 2003, and following the complete war-time collapse of the country's economy, international logging and mining companies have shown renewed interest in Liberia's rich timber and mineral resources. The country's economy is largely resource-driven and thus, in an attempt to fuel economic growth, extensive tracts of natural habitat have already been assigned to forestry and mining concessions (MPEA, 2010).

It is therefore necessary to assign full protection status to areas of high conservation priority to meet the Forestry Development Authority's protected area network goal. Our dataset may aid the authorities in selecting locations for additional protected areas. Our data are also being used to evaluate the conservation importance of proposed and existing protected areas. A systematic planning study to set conservation priorities in Liberia is underway (Junker et al., unpubl. data).

Experience from other regions has shown the importance of stepping up efforts to control hunting in and around existing and future conservation areas (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Kuehl, Diarrassouba, N'Goran and Boesch2011; Tranquilli et al., Reference Tranquilli, Abedi-Lartey, Amsini, Arranz, Asamoah and Babafemi2011; N'Goran et al., Reference N'Goran, Boesch, Mundry, N'Goran, Herbinger, Yapi and Kühl2012, Reference N'Goran, Kouakou, N'Goran, Konaté, Herbinger and Yapi2013). Our survey results showed that snare hunting was more common in non-forested areas in which smaller mammals were more abundant, whereas signs of gun-hunting were more common in forest blocks, where we recorded larger-bodied mammals and primates more frequently. These generally have lower intrinsic rates of population growth and are thus more susceptible to overharvesting (Weinbaum, et al., Reference Weinbaum, Brashares, Golden and Getz2012). This may explain why chimpanzees are no longer present in non-forested areas with high human population density.

Purchase and import taxes on ammunition and rifles, and the introduction of certified arms permits, as suggested by Verschuren (Reference Verschuren1983), may help to control gun-hunting. More importantly, inspecting markets in major towns, roadside sale posts and vehicles should help to reduce the commercial trade of illegally hunted bushmeat species (Verschuren, Reference Verschuren1983). This should be relatively easy to apply because administrative and Forestry Development Authority control posts already exist along all of the major transport routes.

The combination of large-scale resource exploitation and unsustainable hunting may jeopardize the continued existence of Liberia's chimpanzees and other wildlife (Supplementary Fig. S5). We propose conservation strategies with the primary aim of protecting chimpanzees and their habitat but these measures may also safeguard mammal species diversity. We found a positive correlation between chimpanzee abundance and mammal species diversity, indicating that chimpanzees may serve as indicators for high levels of biological diversity (as defined by Lindenmayer et al., Reference Lindenmayer, Margules and Botkin2000). Previous studies in Taï National Park, Côte d'Ivoire have shown that improved protection for chimpanzees and other mammals can be achieved through regular and site-specific law enforcement patrols and permanent research presence (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Kuehl, Diarrassouba, N'Goran and Boesch2011; N'Goran et al., Reference N'Goran, Boesch, Mundry, N'Goran, Herbinger, Yapi and Kühl2012). Regular wildlife surveys will provide information on population trends and allow authorities to evaluate the effectiveness of their conservation strategies (Tranquilli et al., Reference Tranquilli, Abedi-Lartey, Amsini, Arranz, Asamoah and Babafemi2011).

In Liberia one of West Africa's last viable chimpanzee populations is threatened by widespread hunting for bushmeat and potential habitat destruction for large-scale resource extraction in the logging and mining sectors. We provide an accurate and comprehensive data-based platform for local wildlife protection authorities, policy-makers and international conservation agencies, which they can use to inform effective conservation strategies to protect what is left of Liberia's rich wildlife heritage. More specifically our results will provide the basis for systematic conservation planning and present a reliable reference for future trend analyses and assessments of conservation effectiveness. With its interactive maps and various functionalities, the IUCN SSC A.P.E.S. database represents an important tool in this process, allowing all stakeholders to access and evaluate information. Furthermore, our data are also being used by conservation organizations to prepare environmental impact assessments of several proposed extraction projects and large-scale agricultural plantations, to facilitate the Liberian government to make evidence-based management decisions that balance both economic and conservation priorities.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Max Planck Society and the Arcus Foundation. We thank ArcelorMittal for providing stipends to CGT and MML, and the Forestry Development Authority in Liberia for granting us permission to conduct the survey and for their on-going collaboration. We thank C. Boesch for providing advice and assistance; the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation, Conservation International, Fauna & Flora International and the University of Liberia for their interest, support and collaboration; the Society for the Conservation of Nature of Liberia and Across the River—a Transboundary Peace Park Project for sharing unpublished data; the USAID/Liberia Governance and Economic Management Support project; the Liberia Institute of Statistics & Geo-Information Services for providing GIS data; S. Buckland and E. Rexstad for their advice on survey design; two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments; and all county superintendents for their collaboration. Lastly and most importantly we are grateful to all survey team members for their motivation and hard work: Evangeline Nyantee, Tecanna Jones, Nathaniel Naklen, Augustine Nimley, Kokoloku Sali, Beyan Flomo, Abednego Gbarway, Tulay Padeah, Samuel Cooper, John Kaso, Kpaquille Sheriff, Mr Joseph, Victor Davies, Prince Kor, Mr Kuli, Sam Freeman, and John Smith.

Biographical sketches

Clement Tweh is interested in human–wildlife conflict, its underlying causes and ways to mitigate it. Menladi Lormie is a biologist with a keen interest in monitoring of wildlife populations as a tool to inform conservation management in Liberia. Célestin Kouakou's research focuses on biodiversity conservation and the sustainable management of ecosystems. Annika Hillers works to facilitate protected area management in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Hjalmar Kühl is a quantitative ecologist with a focus on patterns of spatial and temporal population distribution among great apes, ecological drivers of population diversification, development of monitoring approaches and evidence-based conservation. Jessica Junker's research focuses on global, regional and site-specific population dynamics among great apes, and the factors influencing these.