Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most frequently reported cancer in women in the United States, with 281,550 new cases diagnosed per year (American Cancer Society 2021). Treatment advances have yielded a 90% five-year survival rate for women with BC (Runowicz et al. Reference Runowicz, Leach and Henry2016). Although survival rates have increased, BC patients of childbearing age (<45 years) for whom treatment was successful may not have had the opportunity to engage in fertility preservation, family planning, or complete their family during cancer treatment (Logan et al. Reference Logan, Perz and Ussher2019). Young women of childbearing age undergoing BC diagnosis and treatment may experience a wide range of reproductive concerns and distressing threats to fertility, pregnancy, and parenting, including delaying pregnancy, termination of pregnancy, loss of ability to breastfeed, and undergoing cancer treatment during pregnancy or early parenting (Logan et al. Reference Logan, Perz and Ussher2019; Ussher and Perz Reference Ussher and Perz2019). BC patients of childbearing age represent 10.9% of all new cases of BC in the United States, making these concerns clinically important issues for this population (Runowicz et al. Reference Runowicz, Leach and Henry2016).

Existential distress often accompanies cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Cohen and Edgar2006). Cancer-related fertility concerns are a source of existential distress in the loss of meaning related to important roles (motherhood) and life goals (pregnancy and child-rearing), as well as uncertainty about the future (Vehling and Philipp Reference Vehling and Philipp2018). In a study of female gynecologic cancer survivors who experienced cancer-related infertility, most (n = 15, 75%) reported a sense of meaninglessness and 40% (n = 8) reported a sense of lack of purpose in life due to reproductive concerns (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Rowland and Chi2005). Additionally, female cancer survivors report higher fertility-related distress than men (Ussher and Perz Reference Ussher and Perz2019), with 20–70% of survivors reporting clinically significant distress (Logan et al. Reference Logan, Perz and Ussher2019). Paradoxically, women are less likely than men to receive sufficient fertility-related information during their course of cancer treatment (Anazodo et al. Reference Anazodo, Laws and Logan2019). In female cancer survivors, a higher level of fertility concerns is associated with higher odds of experiencing moderate to severe depression (Gorman et al. Reference Gorman, Su and Roberts2015), anxiety, grief, and challenges with gender identity (Ganz et al. Reference Ganz, Greendale and Petersen2003; Logan et al. Reference Logan, Perz and Ussher2019; Ussher and Perz Reference Ussher and Perz2019). Assessing patients’ desire for children and addressing the impact of cancer-related fertility concerns on a patient’s mental health is a critical component of comprehensive cancer care across the cancer care continuum for young women with BC (Ussher and Perz Reference Ussher and Perz2019; Zebrack et al. Reference Zebrack, Mathews-Bradshaw and Siegel2010).

Recent research has shown that existential, meaning-focused, and positive psychological therapies can be effectively applied in the context of cancer and can improve psychosocial outcomes such as anxiety, depression, hopelessness, optimism, self-efficacy, and quality of life (Breitbart et al. Reference Breitbart, Pessin and Rosenfeld2018; Casellas-Grau et al. Reference Casellas-Grau, Font and Vives2014; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Cohen and Edgar2006; Nakamura and Kawase Reference Nakamura and Kawase2021; Rosenfeld et al. Reference Rosenfeld, Cham and Pessin2018; van der Spek et al. Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-kraan2017; Vehling and Philipp Reference Vehling and Philipp2018). Targeted existential and meaning-focused interventions have the potential to reduce existential distress from cancer-related fertility concerns by enhancing sense of meaning, psychological flexibility, and adaptive coping strategies to adjust to cancer. Existential and meaning-based interventions warrant further examination in this population. However, the relationship between the impact of cancer-related fertility concerns on existential distress and meaning making must first be explored prior to the development and adaptation of an intervention. Qualitative methodology (Boeije Reference Boeije2002; Marris Reference Marris1994) has the potential to capture the subjective experiences of female BC survivors’ cancer-related fertility concerns impacting existential distress and meaning in life (Logan et al. Reference Logan, Perz and Ussher2019). Understanding these perspectives can provide a contextual framework (Britten Reference Britten1995) for developing and adapting necessary supportive interventions to this population.

The current study was part of a larger longitudinal survey-based study that sought to investigate the relationship between meaning and psychological distress (i.e., anxiety, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder) and the stability of meaning and psychological distress over time in 98 young women with BC who experienced reproductive concerns. This study focused on identifying avenues for improving the quality of life of young women with BC who endorse reproductive concerns due to cancer diagnosis and treatment, as there is an increased likelihood of distress and decreased likelihood of receiving information and appropriate psychological care. Existential distress appears to play a role in coping with infertility due to cancer (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Rowland and Chi2005), and the relationship between this distress and other diverse types of infertility concerns warrants further exploration. The purpose of this qualitative study was to describe the experience of cancer-related fertility concerns impacting existential distress and meaning making among female BC patients of childbearing age. Additionally, we assessed the psychosocial supportive needs of this population.

Methods

Study design and population

A purposive sampling strategy was used to identify female BC patients with cancer-related reproductive concerns. Inclusion criteria were (a) female BC patients who endorsed having undergone treatment for a BC diagnosis, which included current chemotherapy, radiation, surgical planning, or hormone therapy interventions; (b) 18 to 45 years old, and (c) endorsed experiencing reproductive concerns due to BC (i.e., “has your cancer diagnosis impacted your thoughts or feelings related to your fertility, reproductive plans, or parenting?”). The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved the study (COMIRB#19-1812).

Data collection methods

Recruitment was conducted via a review of medical charts for patients seen in the oncology breast clinic and via recruitment flyers distributed through email LISTSERVS. Participants self-identifying as potentially eligible and interested completed an online screening form to confirm eligibility; eligible participants then provided informed consent and completed an online survey through REDCapTM. As part of this survey, participants shared their thoughts on the impact of their cancer diagnosis and treatment on their sense of identity and their story using open-text fields. Responding to these items was optional for all participants. The standards for reporting qualitative research guidelines were used to report the research (O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Harris and Beckman2014).

Description of materials

Demographics

Demographic data, cancer-related support preferences (Arch et al. Reference Arch, Vanderkruik and Kirk2018), and diagnostic and treatment information were collected from participants.

Qualitative text fields

Seven open-ended questions asked participants to describe the impact of cancer diagnosis and treatment on their sense of identity (Supplementary Appendix A). Authors A.L.C. and E.K. constructed the interview questions using definitions of meaning from Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (MCP) (Breitbart and Poppito Reference Breitbart and Poppito2014). Participants reflected on relevant roles and relationships before, during, and after BC diagnosis and treatment.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis based on Braun and Clark’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) six-step process was used to analyze the open-ended question responses. The six-step process utilized by the study team members (A.L.C. and S.R.) are as follows: (1) becoming familiar with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining themes, and (6) writing up the findings (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Participant responses to the open-ended survey items were downloaded from REDCapTM, aggregated into a single qualitative database, and uploaded into ATLAS.ti software to conduct the qualitative analyses. Two study team members (A.L.C. and S.R.) independently read the aggregated open-ended survey responses prior to developing the codebook to gain a full understanding of participant experiences and discussed themes emerging from the data. They then developed the initial codebook and refined the codebook as new themes emerged. Study team members coded each open-ended survey independently and met regularly to discuss emerging themes, discrepancies, and alternative explanations. Emergent themes were discussed with all team members (A.L.C., S.R., and E.K.). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic data and cancer-related support preferences.

Results

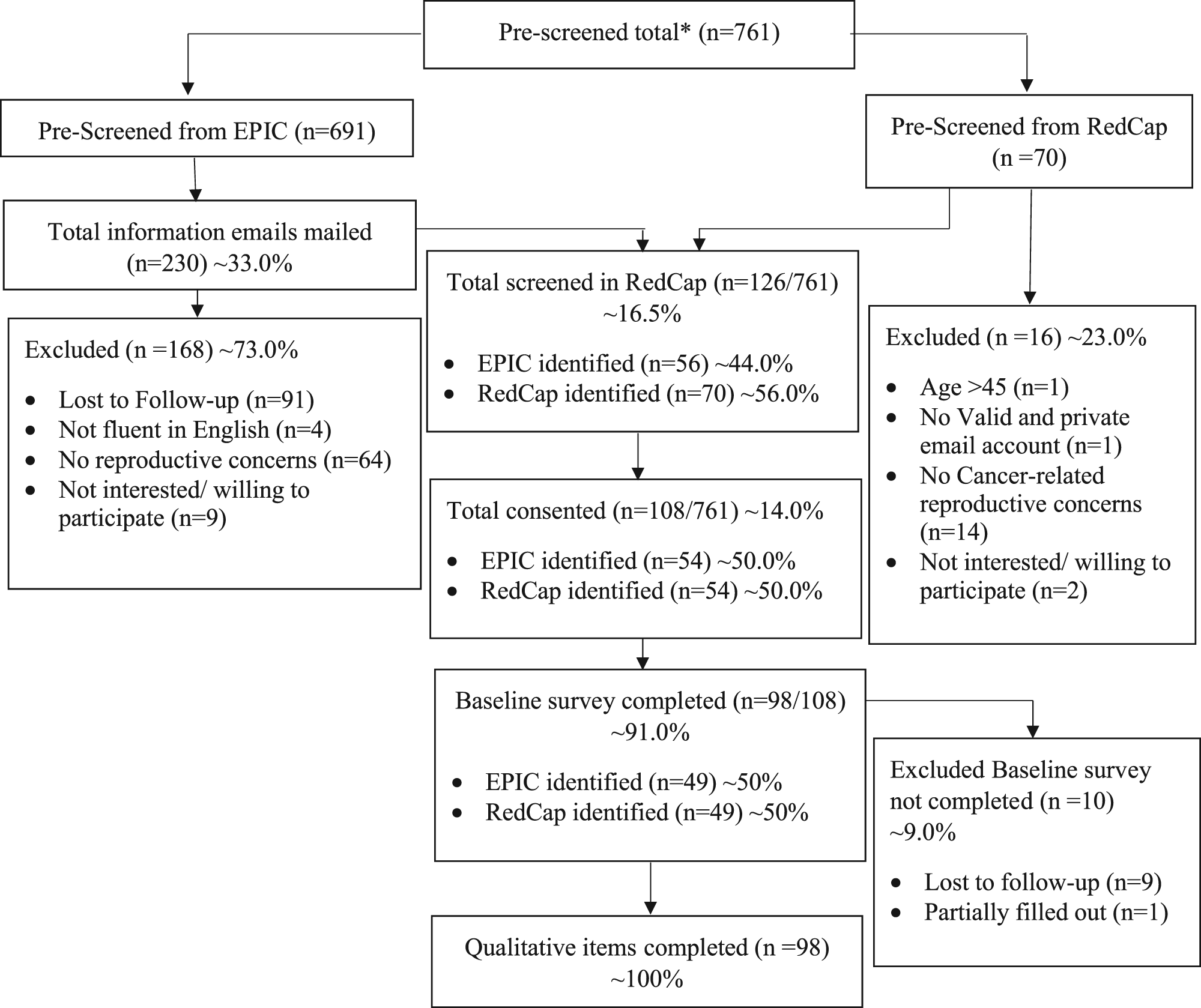

From July 2000 to April 2021, study staff screened 761 BC patients. Ninety-eight of the 761 patients screened met eligibility criteria, consented to the study, and completed the online survey (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. CONSORT flow diagram. *Sum of Prescreening Epic Chart and Prescreening RedCap

Participant characteristics

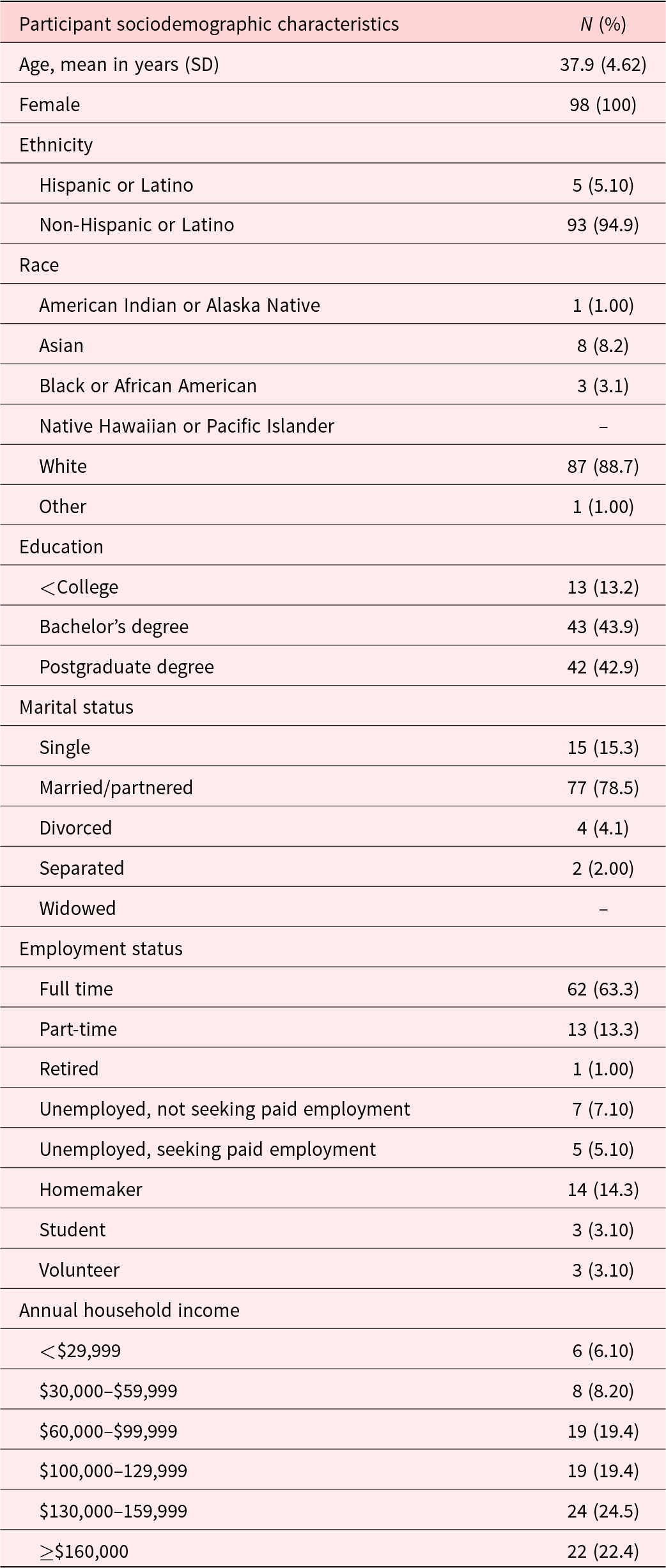

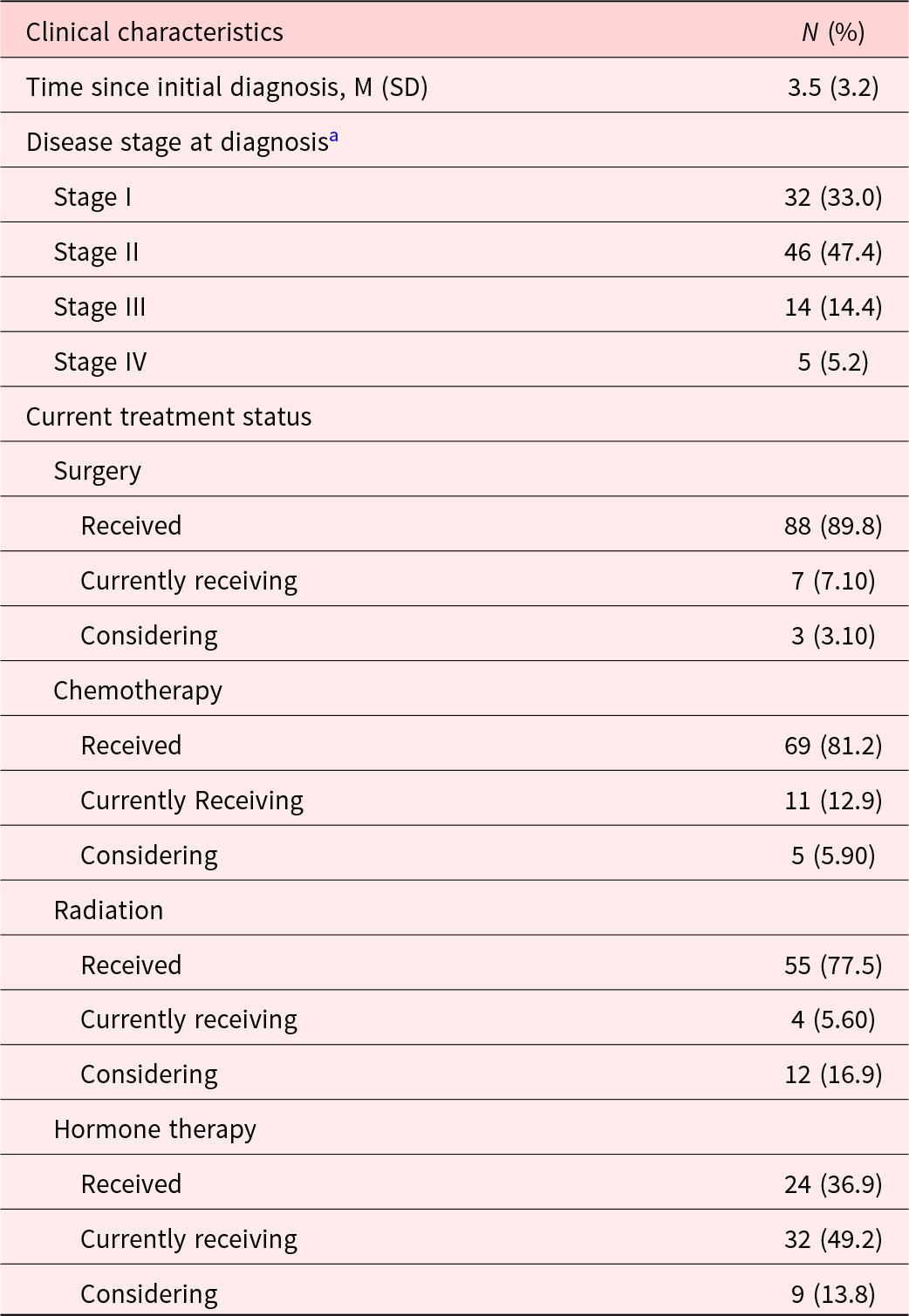

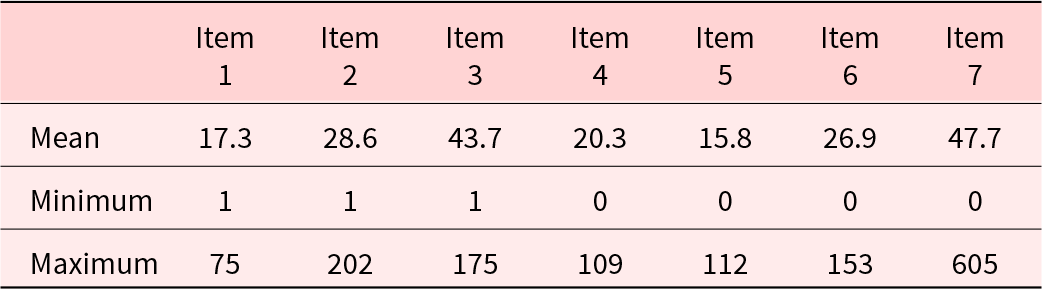

Participants were identified as white (88.7%), non-Hispanic (94.9%), married/partnered (78.5%), employed full time (63.3%), and completed college or a postgraduate degree (86.8%). Participants were 37.9 years old on average and had either stage I (33%) or II (47.4%) BC. More than half of participants (60.2%) indicated that they were currently seeking any kind of help or treatment for anxiety, distress, or other emotional difficulties, and 53.6% of participants reported that these difficulties were “mostly related” or “completely related” to having had cancer. Many participants endorsed (75.5%) needing the support of a counselor or support group during their experience of cancer or survivorship. Tables 1 and 2 present participant sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, respectively. Table 3 presents an overview of cancer-related supportive preferences. Participants demonstrated generally good engagement with their responses to qualitative items. Table 4 describes participant response word count for each item.

Table 1. Participant sociodemographic characteristics (N = 98)

Table 2. Participant clinical characteristics (N = 98)

a Item response is missing from one participant.

Table 3. Cancer-related support preferences

a One respondent did not answer this question.

b 1 = completely; 4 = not at all.

c Two respondents did not answer this question.

d 1 = most preferred; 8 = least preferred.

e 1 = most preferred; 6 = least preferred.

Table 4. Qualitative responses word count descriptive statistics

Qualitative themes

Two major themes emerged from thematic analysis: (1) BC patient sources of existential distress from cancer-related fertility concerns and (2) meaning making with fertility-related existential concerns. Table 5 displays participant quotes illustrating the range and nuance of each theme and subtheme presented below.

Table 5. Participant quotes by major theme and subthemes.a

a Direct quotes are identified by a unique three-digit number.

BC patient sources of existential distress from cancer-related fertility concerns

The three subthemes that emerged from BC patient sources of existential distress represent physical, emotional, and cognitive domains of existential distress.

Loss of womanhood: treatment-related physical changes impact on gender identity (Physical)

Most participants described a fundamental shift in their core identities due to cancer-related fertility changes. Specifically, many perceived the threat to their ability to conceive as a loss of their identity as a woman, mother, and future mother. Several participants felt that physical changes to their bodies such as mastectomies, lumpectomy, hysterectomies, chemotherapy-induced menopause, and hair loss were losses to their womanhood. One woman described these physical losses as “cancer stealing my body.” Participants, who reported always wanting to have children, indicated that the impact of the loss or threat to their fertility was life-altering to a core facet of their identities. Some participants indicated that it was not until the threat to their fertility came to the forefront that they became more aware of how important motherhood was in their identity. Others, who gave birth while undergoing cancer-related treatments, also described an impact on their identities as mothers. These women felt a loss of motherhood followed by unanticipated treatment-related barriers to bonding with their newborn child, including experiencing treatment side effects (e.g., illness and fatigue) that reduced their ability to hold and care for their child or not being able to breastfeed due to mastectomies or chemo-related toxicities.

Existential distress due to treatment decisions impacting fertility (Emotional)

Following initial diagnosis and treatment initiation, many participants described a sudden, unexpected rush of concerns and emotions, which added to their sense of making difficult treatment decisions very quickly. Many patients felt insufficiently informed of the potential long-term complications their cancer treatments could have on their fertility; thus, many BC patients reported decision-making that prioritized survival without also weighing their plans for childbearing. Several women voiced regret or decreased confidence in their treatment decisions during such a vulnerable yet critical time window. This sense of regret was particularly salient among those who did not harvest their eggs or store embryos. Many BC patients expressed anxieties about their future ability to conceive or uncertainty around the need for alternative family planning methods.

Furthermore, several women described a newfound sense of fear or ambivalence around future decisions to conceive, given known increased risks of recurrence associated with pregnancy following a BC diagnosis. Some expressed fear of dying from cancer before they could ever have children or passing their BRCA (BReast CAncer) gene mutation on to future children. The emotional toll of cancer and fertility-related concerns impacted survivors who could conceive in several ways. Women who were able to get pregnant reported a mix of positive emotions of being able to conceive (e.g., joy, relief, and accomplishment) and negative emotions such as fear and uncertainty related to possible complications during pregnancy. Among these mothers who faced cancer treatment–related barriers to bonding with their newborns postpartum, feelings of failure or inadequacy were a great source of distress.

Shattered vision: cancer-related infertility impact on meaning and purpose (Cognitive)

In addition to the loss of identity (i.e., “womanhood”) and existential distress reported by BC patients experiencing changes in fertility due to cancer, many participants endorsed these changes impacting their sense of meaning in life. Along with the destruction of their cognitive constructions of self, family, and future, cancer-related fertility changes had also taken a deeply held sense of purpose that those schemas had created, collectively described as a “shattered vision” for the future. Although many BC patients shared this experience of infertility-related loss of meaning, the expressed severity, complexity, and personal impact varied across respondents.

Notably, some participants did not describe a loss of meaning but rather described a deepened sense of purpose as a mother, either to existing children or an invigorated determination to create a family through alternative family planning options. Some women who had children prior to cancer-related fertility changes or who were able to conceive posttreatment reported that their experience with cancer gifted them with a profound sense of gratitude for life and fostered an even deeper sense of purpose in their role as mothers. However, other women with children in this sample continued to struggle with recalibrating their sense of purpose following secondary cancer–related infertility that shattered their visions of bigger families.

Meaning making with fertility-related existential concerns

In reflecting on fertility-related existential concerns, participants also described and explored their varied approaches to confronting their sense of loss, examining their values, and seeking new sources of meaning.

Coping with loss of meaning

Participants described various ways they cope with fertility-related existential concerns and loss of meaning. Some women reported engagement in health-care utilization through counseling, couples’ therapy, support groups, psychotropic medications, and psychotherapy to cope with their distress. Many stated they cope with the loss of meaning through inner exploration, reflection, and acceptance. When asked how patients can find meaning despite life’s hardships, most BC patients identified seeking meaning through mutual relational connectedness. These women reported finding strength and hope in being supported by and feeling connected to loved ones. Many described their ability and motivation to return that support – to “show up for” others, including family, friends, their community, and other cancer survivors – as a deep source of meaning during difficult times. BC patients also found meaning in spirituality or faith through prayer, their relationship to God, or trusting in a divine plan for their life. Others turned to enjoyable activities (e.g., being in nature, hobbies, physical activity, and travel), work and career, or forward-thinking goals and plans (e.g., career goals, life plans, and starting something new) as a source of meaning during difficult times. A small number of patients also cited finding hope in the medical and scientific advancement of cancer treatments for future cancer patients.

Participants who described motherhood as a steadfast source of meaning in their life indicated they found hope through alternative family planning. Several participants renegotiated their definitions of motherhood and parenting with their partners and opted to foster or adopt.

Re-evaluating priorities in life

Many participants indicated their cancer-related fertility concerns helped reframe their perspectives on what is most important in their lives. Several participants noticed an active shift in how they invested their energy and time. Frequently referenced values included mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual wellness. Many BC patients described living in the present and actively changing their behaviors to focus on valued priorities such as connecting with loved ones. Most explained their cancer experience and cancer-related fertility concerns shifted the way they describe their personal identity from external (work, appearance, and status) to internal (family, spirituality, health, and friendships) facets. One woman described this experience as “cancer clarity.”

Resilience to loss

The cancer experience made many participants appreciate the fragility of life and no longer taking life for granted. One BC patient described this newfound sense of appreciation as “living every day to the fullest.” Several BC patients indicated their cancer experience provided them with a new identity, and they emerged as “fighter[s]” or a “survivor[s]” from their cancer diagnosis and treatment. BC patients who already had children felt their identity as a mother was enhanced by their cancer experience and cancer-related fertility concerns. Many referenced their children as what prevented them from experiencing loss of meaning, and they echoed a sense of gratitude for their family.

Persistent loss of meaning

Some participants referenced a perceived inability to find passion in another facet of life or worthiness in their own life outside of the construct of motherhood. Many of these BC patients characterized cancer treatment and cancer-related fertility concerns as dehumanizing. Several women indicated they were still actively processing the loss of meaning in their lives and searching for new forms of meaning.

Discussion

This study explored the impact of cancer-related fertility concerns on existential distress and meaning making and assessed the supportive needs of female BC patients. Many participants expressed a need for supportive services from a counselor or support group during their experience with cancer. More than half of participants indicated they are currently seeking any kind of help or treatment for anxiety, distress, or other emotional difficulties, and 53.6% of participants reported that these difficulties are mostly or completely related to having had cancer.

Qualitative analyses identified three subthemes representing the physical, emotional, and cognitive domains of cancer-related fertility concerns impacting existential distress. Additionally, participants identified various ways they found meaning or where they are in their current process in meaning making with fertility-related existential concerns. Qualitative findings of existential distress and challenges to gender identity are consistent with those of previous studies assessing fertility-related existential distress in cancer patients (Logan et al. Reference Logan, Perz and Ussher2019; Ussher and Perz Reference Ussher and Perz2019). More specifically, many women viewed their cancer diagnosis and treatment as disrupting family building, which was seen as a universal major life event. The degree to which participants’ sense of meaning and purpose in life varied among patients with and without children. This may suggest different degrees of experiential sources of meaning among BC patients with and without children.

Participants provided insight into various ways they cope with cancer-related fertility concerns. Connection to loved ones and engagement in enjoyable activities such as hobbies or spending time outdoors helped BC patients enhance their sense of meaning despite cancer-related fertility concerns. Additionally, participants noticed an active shift in how they chose to focus their time and energy. For example, some BC patients spend less time focusing on work and more time on their relationships with loved ones or activities in line with their values. Most BC patients described this as reevaluating their priorities and perspectives in life. Finally, several BC patients felt changes in cancer-related fertility enhanced their sense of meaning and purpose and helped them become more resilient in the face of hardships. In contrast, several BC patients were actively processing and searching for sources of meaning in their life.

These findings have important implications for developing targeted supportive and informational interventions for female BC patients with cancer-related fertility concerns. The findings provide a unique perspective and additional context regarding sources of meaning, BC patient adjustment, and ways of coping in this sample. Existential and meaning-making interventions that focus on coping with existential distress, meaning making with loss of meaning and identity, and quality of life may be beneficial for this population. One such intervention could be MCP, a manualized intervention for increasing meaning and purpose for patients with cancer, which has been adapted for BC survivors (Lichtenthal et al. Reference Lichtenthal, Roberts, Jankauskaite and Breitbart2016) and to address grief and loss (Lichtenthal and Breitbart Reference Lichtenthal and Breitbart2015). Research has shown that MCP for cancer survivors is an effective intervention to improve personal meaning, psychological well-being, and adjustment to cancer and reduce psychological distress (Rosenfeld et al. Reference Rosenfeld, Cham and Pessin2018; van der Spek et al. Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-kraan2017). This therapy holds salience for a population of women who experienced reproductive concerns in the context of cancer survivorship as it specifically addresses issues related to identity, legacy, roles, responsibilities, and connecting to life through love and relationships in the context of cancer. MCP’s foundational components are rooted in enhancing meaning and patient quality of life through patient identification of historical, attitudinal, creative, and experiential sources of meaning in their life (Breitbart et al. Reference Breitbart, Pessin and Rosenfeld2018; Breitbart and Poppito Reference Breitbart and Poppito2014). These core sources of meaning in MCP target the identified experiences of existential distress and adjustment to cancer-related fertility concerns in this sample. Additionally, several BC patients reported unmet informational needs regarding cancer-related fertility prior to the initiation of cancer treatment. Informational interventions such as decision-aids can reduce decisional conflict in treatment decisions (Ehrbar et al. Reference Ehrbar, Urech and Rochlitz2019) by informing female BC patients of childbearing age early on in the treatment process about fertility issues related to treatment and help facilitate timely fertility preservation counseling before starting cancer treatment. Early implementation of informational interventions in the treatment process may buffer against the unmet informational needs expressed by participants.

Limitations

The qualitative findings are indicative of a subset of individual female BC survivor experiences rather than the general experiences of the population. The sample primarily comprised white married or partnered female BC patients, which does not capture the experiences of female BC patients of color or non-partnered or married female BC patients. The 7-item open-text survey format did not allow for study staff to probe participants for more information in vivo. Additional probes may have identified that uncovered themes had a different qualitative methodology been used, such as individual semi-structured interviews. Additionally, definitions of meaning and meaningful life moments are highly individual. We allowed participants to define meaning individually; responses to this question likely influenced responses to others, as well as the study results.

Conclusions

Current BC survivorship guidelines provide limited guidance about infertility (Runowicz et al. Reference Runowicz, Leach and Henry2016) and how these issues are handled, especially for those at greater risk for adjustment difficulties, such as female BC patients without children. There is a current gap in care and a lack of discussion about fertility risk prior to cancer treatment for female BC patients. One strategy to address this gap in clinical care is through existential and meaning-making interventions that target existential distress related to the perceived and actual threat to fertility. Existential and meaning-making therapies may have the potential to improve posttreatment psychosocial outcomes in female BC patients with cancer-related fertility concerns by enhancing meaning and purpose and promoting psychological adjustment through adaptive coping.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951522001675.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Army of Women for their support in the recruitment process. A.L.C.’s effort on the original draft preparation and editing was supported by T32CA261787.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.