Introduction

Achieving a healthy balance between personal and professional life is a challenge for many people. When it comes to health professionals, this challenge is made more difficult due to the variety of psychosocial risk factors: work overload, alternating shifts, job demands and responsibilities, wage inequality, little time for patient interaction, high expectations of the population, fragmentation of knowledge due to super-specialization, and a tendency toward emotional neglect (Moreno-Milan et al., Reference Moreno-Milan, Cano-Vindel and Lopez-Dóriga2019). All this occurs in a climate where other sources of pressure on healthcare workers converge, such as threats of lawsuits, disproportionate expectations of society of the possibilities of technology and science, and a model of “acute disease” that is inadequate to assist a population with increasing chronicity and aging (Braquehais, Reference Braquehais2019). Consequently, healthcare professionals, especially in the fields of medicine and nursing, have begun to feel progressive emotional exhaustion and growing disenchantment with their work (Hafferty, Reference Hafferty2003; Aasland, Reference Aasland2015; Parola et al., Reference Parola, Coelho and Cardoso2017).

This exhaustion is accentuated in care contexts such as the end of life since it implies that the worker becomes involved with complex and delicate vital issues (Samson and Shvartzman, Reference Samson and Shvartzman2018; Hynes et al., Reference Hynes, Maffoni and Argentero2019). Integrating the clinical, emotional, and ethical dimensions at the end of life can be very demanding for the professionals in charge of providing care. On the other hand, in palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic, other new and unexpected factors have been added that have further increased the risk of suffering in care providers: priorities in resource allocation, lack of contact with patients (telemedicine vs. face-to-face consultation), deficient healthcare in nursing homes, death in solitude of seriously ill patients, and lack of protection of the workers themselves by organizations and health authorities (Gautam et al., Reference Gautam, Kaur and Mahr2020; Kannampallil et al., Reference Kannampallil, Goss and Evanoff2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Huang and Wei2020; Lai et al., Reference Lai, Ma and Wang2020).

We consider it an ethical imperative to make progress in the approach to burnout in palliative care. Firstly, because published evidence suggests that this emotional depletion has a significant influence on the quality of care, patient safety, and patient satisfaction (Chittenden and Ritchie, Reference Chittenden and Ritchie2011; Shanafelt et al., Reference Shanafelt, Trockel and Ripp2019). Another compelling reason is the range of possible consequences for the psychological well-being of the worker as an individual, from the breakdown of relationships (Shanafelt et al., Reference Shanafelt, Boone and Dyrbye2013) and the appearance of addictions such as alcoholism (Oreskovich et al., Reference Oreskovich, Shanafelt and Dyrbye2015), to suicide (Fridner et al., Reference Fridner, Belkic and Minucci2011; Shanafelt et al., Reference Shanafelt, Balch and Dyrbye2011).

The core of the psychological well-being and suffering of health workers lies in their responsibility as professionals (Zanatta et al., Reference Zanatta, Maffoni and Giardini2020). Feeling responsible is recognizing the authorship of the actions that are carried out freely and, especially, the result thereof, generating a need to assume the consequences (Royal Academy of Spanish, 2020). In its conceptual evolution, different types of responsibility can be distinguished that can directly affect professional well-being: individual, social (or broad), and organizational/institutional.

We propose a deep reflection on the psychological suffering of the palliative care worker. This paper will have particular characteristics. We will reflect on the characteristics of the three levels of responsibility (individual, social, and organizational) that influence the psychological well-being (vs. suffering) of the palliative care professional and, following this, we will propose a global strategy for the care of the worker's psychological well-being.

Individual responsibility

The approach to burnout from the standpoint of individual responsibility has been — and often continues to be — the most widely used. It considers that exhaustion and professional satisfaction depend exclusively on the worker, so the prevention of emotional fatigue and the promotion of psychological well-being should be approached understanding them as a deficit of the workers themselves (Oltra, Reference Oltra2013; Sansó et al., Reference Sansó, Galiana and Oliver2015; West et al., Reference West, Dyrbye and Erwin2016). Individual responsibility refers to the fact that a subject is responsible for the consequences of their particular acts. The consequences determine the moral value of their actions, possibly warranting legal responsibility (criminal, civil, or administrative), but also moral responsibility because they can generate shame and guilt or, on the contrary, recognition, satisfaction, and good conscience. All of this influences the psychological well-being of the healthcare professional.

This perspective tries to identify individual predictors of professional burnout, although these are not modifiable. Most studies include sociodemographic variables such as age, gender, and years of experience (Fernández Sánchez et al., Reference Fernández Sánchez, Pérez Mármol and Peralta Ramirez2017). Other predictors of burnout in palliative care are lack of self-confidence in communication skills with patients and family members, lack of time (which makes it difficult to communicate effectively), communication of bad news, pain management, the appearance of “conspiracy of silence” (withholding a negative prognosis from the patient by family members), and the professional's relationship with relatives, and with suffering and death (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Fonseca and Carvalho2011; Rothenberger, Reference Rothenberger2017). One of the predictors most closely related to burnout is the excessive workload and the overload of individual responsibility for working under pressure and alone for an excessive number of hours (50 and up to 60 h/week).

All these factors should be considered from a team management and organizational standpoint (Koh et al., Reference Koh, Chong and Neo2015), but the approach to burnout has usually been from an individual perspective (Kamal et al., Reference Kamal, Bull and Wolf2020). Attempts at prevention have been made by providing coping resources and self-regulation skills since certain effective coping mechanisms are associated with less exhaustion. To do this, training strategies have been implemented on communication skills, time management, communication of bad news, stress management, or mindfulness (Asuero and García de la Banda, Reference Asuero and García de la Banda2010; Asuero et al., Reference Asuero, Rodríguez Blanco and Pujol Ribera2013; Sansó et al., Reference Sansó, Galiana and Oliver2018; Benito Oliver and Rivera Rivera, Reference Benito Oliver and Rivera Rivera2019). In this line, the recognition of one's own limits (both at a personal and professional level) has been identified as a first step, which seems to be insufficient (Lozano Gomaris, Reference Lozano Gomaris2016). These traditional skills-training approaches have shown low efficacy in the medium- and long-term. A primary reason, among others, is that they are not usually accompanied by actions at the social or organizational/institutional levels. The approaches based on training worker's skills (communication, emotional regulation, self-care, etc.) largely attribute the responsibility for burnout to an inadequate coping of the specific individual, indirectly blaming them for their discomfort. This implies avoiding the responsibility of the meso-macro levels involved, which also require specific and adequate intervention.

Social (broad) responsibility

The crisis caused by the pandemic we are suffering has revealed the relevance of the three previously mentioned levels of responsibility: individual, social, and organizational. The dramatic shortage of resources (material and psychological) for health personnel has shown us that to protect the health of all, we must protect those who care for it. On one hand, the principle of justice requires prioritizing those who will benefit the community the most. On the other hand, the principle of reciprocity implies that society has to support those who assume a disproportionate burden or risk in protecting the common good. In many cases (and of course in the pandemic), the psychological well-being of the worker does not depend only on individual management. The social and work environment are also essential.

Along with individual factors, organizational and interpersonal, institutional, and social aspects have also been identified as causes of professional burnout (West et al., Reference West, Dyrbye and Erwin2016). The responsibility for the worker's well-being is associated with the individual's relationship with the environment and with the institutions (González Rodríguez Arnáiz, Reference González Rodríguez Arnáiz2004; Gracia, Reference Gracia2004a). Our actions affect us, but also the environment, and vice versa: what happens around us influences us, inexorably.

The broad sense of responsibility was developed in the second half of the 20th century, largely thanks to the ethics of responsibility introduced by Max Weber in the early 20th century (Weber, Reference Weber1984; Gracia, Reference Gracia and Gracia2004b). This responsibility implies being responsible “toward something or someone with whom one is committed or over whom one has some specific power or link.” We feel responsible for all those people or things with which we have ties and moral commitments, which generates, for example, the feeling of compassion (González Rodríguez Arnáiz, Reference González Rodríguez Arnáiz2007; Sánchez González, Reference Sánchez González and Gracia2016). We are responsible for the consequences of our actions in our environment (for what “I do”) and for the omission of action (for what “I do not do”). We have “antecedent” responsibility (with the acts performed) and “consequent” (toward the future), so we must consider the result that our actions will have on something or someone whom we must care or protect.

The well-being of the palliative care professional depends on themselves and also on their relationship with the environment. Their exhaustion is related to the work environment, to the personal relationship they have with other team members and with patients. This responsibility of the worker toward their environment is bi-directional: health workers must take care of their environment and the environment must take care of them. The relationship with the work environment is especially problematic in units that work with patients in the final phase of their lives, often the elderly, alone and frail. The reason for the admission of these patients is, in many cases, social fragility, that is, the lack of a social and family network and the consequent need for care (Araya and Iriarte, Reference Araya and Iriarte2018a, Reference Araya and Iriarte2018b). The professional has the (social) responsibility to attend to these patients, and the lack of resources can generate feelings of helplessness and discouragement (Zambrano et al., Reference Zambrano, Chur-Hansen and Crawford2014). From the ethical approach of compassion, for example, we can contribute to reducing the psychological suffering generated by an inhospitable environment with the professional since it sensitizes us toward the suffering of others and promotes humanity in each of our acts (Mélich, Reference Mélich2010; Sikka et al., Reference Sikka, Morath and Leape2015).

Organizational and institutional responsibility

In recent decades, evidence has been obtained that supports the relationship of certain organizational and institutional factors with the exhaustion of professionals (Kondrat, Reference Kondrat2016). Institutions are as responsible for the well-being of professionals as they are themselves (Berry and Adawi Awdish, Reference Berry and Adawi Awdish2020). However, despite the existence of a shared responsibility framework that should lead to finding global solutions (at the individual, team, organizational, and even system level), these continue to not be carried out in a meaningful and constructive way. The reality is that institutions do not work on the care of professionals, but rather their value as “human capital” is assumed (Gálvez Herrer et al., Reference Gálvez Herrer, Gómez García and Martín Delgado2017).

Unfortunately, this capital is not cared for as human that it is. The causes of this are multiple and diverse in nature: from a bias in the delimitation of the concept of responsibility, to resistance to change in team and organizational cultures. This resistance is due in part to the fact that certain ideas and beliefs persist in organizations that make it difficult to address the psychological well-being of the professional from an institutional perspective. One of these ideas is that “it is not necessary to cultivate the well-being of professionals because it is an individual choice.” This implies that individuals are solely responsible for their own well-being. As noted, this approach has proven to be insufficient and ineffective, in addition to increasing suffering and lack of commitment to work (Shanafelt et al., Reference Shanafelt, Dyrbye and West2016). Another false belief is that “individuals should only take care of themselves,” derived from the lack of awareness of teamwork, which prevents integrative and interdisciplinary care work, essential in palliative care, from being fully implemented. Often there is no good teamwork management: objectives are not shared, imposed meetings are held that are unproductive, etc. In palliative care, interdisciplinary meetings are essential to deliberate on the different views of the professionals involved in caring for the sick, so they should not be a mere formality of the organization. Finally, there is also the idea that it is necessary to put the objectives of the organization (thinking of the “client — user — patient”) before those of the workers. The satisfaction perceived by the users — normally poorly evaluated — and the reduction of economic costs are prioritized, instead of the well-being of the professionals (Han et al., Reference Han, Shanafelt and Sinsky2019). This results in the neglect of continuous training, the reconciliation of work, and family life or the necessary work break. However, an increased awareness at the institutional level of the need to take care of the professional would have a positive impact on the institution's objectives.

Care strategies for the psychological well-being of the palliative care professional

To deal with the disenchantment of professionals who work with terminally ill patients, it is common for organizations to implement sporadic, isolated solutions (e.g., stress management workshops and individual training in mindfulness/resilience, and improvement of communication skills), the usefulness of which has yet to be demonstrated. These strategies neglect social, organizational, and institutional factors. As if that were not enough, they are sometimes perceived as an insincere effort by the organization to address the problem, which reinforces the feeling of helplessness and skepticism of the professional (Trockel et al., Reference Trockel, Corcoran and Minor2020). If the psychological well-being of the professional is considered to be a solely individual responsibility, professionals can seek solutions that are personally beneficial, but detrimental to the organization and society, for example, reducing their effort in the workplace.

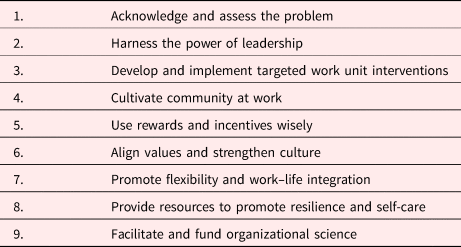

It is urgent to design strategies that globally address the burnout of palliative care professionals. Coherent strategies focused on those most responsible for the burnout are needed: the subject themselves, their immediate environment, and the institution. A Mayo Clinic research team proposed several organizational strategies with levels of approach to the well-being of professionals with the aim of preventing the burnout of their physicians from having an impact on the organization, as it causes lower productivity, frequent changes in personnel, worsening, or quality of care, and lawsuits for malpractice (Theimer, Reference Theimer2016). This strategy (Table 1) is currently being applied, for example, in California centers (Shanafelt et al., Reference Shanafelt, Dyrbye and West2016; Shanafelt and Noseworthy, Reference Shanafelt and Noseworthy2017; Trockel et al., Reference Trockel, Corcoran and Minor2020).

Table 1. Organizational strategies to reduce burnout and promote physician engagementa

a From Shanafelt and Noseworthy (Reference Shanafelt and Noseworthy2017).

The Mayo Clinic strategies are complementary to the global strategy (professional, team, and institutional) that we propose (Table 2). This would start with the joint design of a global plan to support the healthcare professional. To design such a plan, the specific problems that lead to burnout of the professionals of the specific institution must be recognized and analyzed. It is necessary to identify the causes behind the burnout of professionals and palliative care teams. Ethically responsible organizations have to consider the well-being of their professionals important and should systematically assess their burnout/well-being, along with other assessments of the quality of care (Milaniak et al., Reference Milaniak, Wilczek and Ruzycka2016). There are a large number of initiatives focused on improving the quality of care (Shanafelt et al., Reference Shanafelt, Dyrbye and West2016), but it is seldom taken into account that it is impossible to achieve quality care with exhausted professionals. The promotion of the health professional's well-being as a fundamental objective shared by the members of the organization is a factor closely associated with the quality of care (Cortina, Reference Cortina2002).

Table 2. Global strategy to care for the well-being of palliative healthcare professionals

In bold the two steps of the strategy: the first step contains three tasks required for step 1 and the second step contains five specific tasks.

The healthcare worker, for their part, has to feel free and cared for in order to express their difficulties and problems. Otherwise, it will not be possible to help them. In addition, they must want to contribute to improving the work environment and facilitating teamwork. Each professional has a responsibility to themselves and to their colleagues, so their involvement in the plan is necessary to prevent and address burnout. It is imperative that all members of the organization are recognized as people and feel heard and supported to achieve greater team and institutional cohesion.

After identifying which problems lead to burnout and exhaustion, a realistic and specific action plan can be designed for the institution and its professionals. To be effective, the plan must be applied at all three levels. The institution, for its part, must review its values and whether these are reflected in its actions: if there is no ethical coherence in the institution, it loses credibility and opens the door to disenchantment. A coordinated and coherent strategy for the implementation of the organization's values is necessary, that is, that the values are disseminated and reflected in real events. The plan must also include actions at the work team level, promoting their coordination, self-management, and the existence of an adequate work environment, for which the involvement of professionals is essential. If training deficiencies are detected, the specific training that the healthcare team and professionals require to improve their well-being must be promoted.

Conclusions

Patient engagement can only result from their healthcare professionals and engagement. Thus, future research and interventions for healthier societies should also maintain the view that “care of the patient requires care of the provider.”

As patients and family members, we need well-trained healthcare professionals with a vocation for care, working as a team, and committed to their personal, professional, and institutional goals. As a society, we want health organizations responsible for ensuring the care of their professionals through comprehensive programs that prevent burnout and promote the well-being of the people who will take care of us when the end of our lives nears. Taking a comprehensive approach to addressing the psychological suffering of healthcare professionals and improving their well-being will allow organizations to ensure access to high-quality palliative care for patients and their families.

As humans, as we age we become aware of the coherence or lack of coherence (moral and emotional) of our lives with our values, projects, and dreams. Palliative care professionals work very hard to help their patients, and it is part of their dreams and personal projects. To take care of patients as they deserve, we owe healthcare workers the same care and the same respect. We can deny it, ignore it or, also, take steps to make professional care a reality. What the future holds will depend on what we do now.