Introduction

In the past decade, the importance of communication competencies in the context of advanced, life-limiting illnesses, particularly about end-of-life care, has become more evident, resulting in a greater need for professionalization (Barnes et al. Reference Barnes, Gardiner and Gott2012; Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Butow and Tattersall2005; Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Duberstein and Fenton2017; Eychmüller et al. Reference Eychmüller, Forster and Gudat2015; Galushko et al. Reference Galushko, Romotzky and Voltz2012). For example, the American Society of Clinical Oncology continues to emphasize in their consensus guideline about patient-clinician communication the need for oncologists to learn more effectively how to communicate in different scenarios, including communication about prognosis, advance care planning, and end-of-life care (Gilligan et al. Reference Gilligan, Bohlke and Baile2018, Reference Gilligan, Coyle and Frankel2017). Within end-of-life care the greatest focus has been on early end-of-life discussions (early palliative care) that lead to less aggressive treatment and an increase of trust among patients and professionals (Bernacki and Block Reference Bernacki and Block2014; Wright et al. Reference Wright, Zhang and Ray2008). However, less is known about effective communication during the last days of life with dying patients and family caregivers (FC), specifically regarding communication about approaching death. Within the context of this study, the terms approaching death, the dying phase, and the last days of life are used as equivalents and refer to the last 4–7 days of a patient’s life, according to international guidelines regarding diagnosing dying (Domeisen Benedetti et al. Reference Domeisen Benedetti, Ostgathe and Clark2013; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Brooks-Young and Brunton Gray2014; White et al. Reference White, Harries and Harris2018).

Although caring for dying patients is an integral aspect of care in different healthcare settings, medical and nursing students lack training and exposure to dying patients and to conversations between health professionals and dying patients and their FC (Hawkins and Tredgett Reference Hawkins and Tredgett2016; Powazki et al. Reference Powazki, Walsh and Cothren2014). As a result, many physicians and nurses have insufficient skills on how to communicate about approaching death (Coyle et al. Reference Coyle, Manna and Shen2015), and thus often feel uncomfortable initiating these conversations (Travers and Taylor Reference Travers and Taylor2016). With the fear of destroying hope and of increasing anxiety in patients and their families, health professionals remain hesitant to initiate the open, direct and honest conversations that the majority of patients and their FC would have wished for (Fallowfield et al. Reference Fallowfield, Jenkins and Beveridge2002). In addition, health professionals may experience lack of satisfaction, increased stress (Hewison et al. Reference Hewison, Lord and Bailey2015) and heightened risk of burnout or illness when dealing with dying patients (Kearney et al. Reference Kearney, Weininger and Vachon2009), with some regarding care for dying patients as one of the most challenging tasks in the profession (McCann et al. Reference McCann, Chodosh and Frankel1998; Olsson et al. Reference Olsson, Windsor and Chambers2021).

Evidence for training in communication skills in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education is mounting, particularly within oncology and in greater topics, such as communicating bad news of a life-limiting diagnosis, advance directives, and prognosis (Bernacki and Block Reference Bernacki and Block2014; Moore et al. Reference Moore, Rivera Mercado and Grez Artigues2013; Walczak et al. Reference Walczak, Butow and Bu2016). When it comes to communication about approaching death with dying patients and their FC, few training initiatives and strategies for communication about the last days of life exist (Billings et al. Reference Billings, Engelberg and Curtis2010; Gibbins et al. Reference Gibbins, McCoubrie and Forbes2011; Parry Reference Parry2011). Even though preferences of patients and FC regarding end-of-life communication have been described (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Clayton and Hancock2007), the “bigger picture” of key stakeholders regarding what is most important to consider when talking about dying and death, as death is approaching, is still missing.

Therefore, within this study, we aimed to explore essential aspects of communicating approaching death that are critical from the perspectives of physicians, nurses, medical students, family caregivers (FC) and patient representatives in non-emergency situations. Based on the findings of this qualitative study, the broader project sought to develop a communication model as the basis for a new educational module of talking about dying for health professionals (Felber et al. Reference Felber, Zambrano, Guffi, Guttormsen and Schnabel2022).

Methods

Design

We thematically analyzed data collected from five focus groups conducted to understand the essential aspects of communication about approaching death from the perspective of key stakeholders. Our analysis was underpinned by a critical-realist ontology and a contextualist epistemology, meaning that reality and knowledge are understood as only partially accessible and that they are shaped by specific contexts and social realities of the participants and the researchers. Nonetheless, within this stance, we still recognize an external reality, and hence why we focused on identifying the “essentials” of communication from participants’ experiences of communication about approaching death (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2021). The study received a waiver of formal ethical review by the Bernese Cantonal Ethical Commission (REQ-2019-00977).

Participants and recruitment

We employed a purposive sampling technique to recruitment. At the university hospital of Bern, one of the major teaching hospitals in Switzerland, we invited participants from the following groups: medical students from 5th and 6th year who were taking part in a mandatory seminar in palliative care; physicians at all hierarchy levels (head, consultants, assistant and resident physicians) and nurses from internal medicine, specialist palliative care, intensive medicine, oncology and neurology. From the outpatient setting, we approached general physicians linked to the regional palliative care network and nurses from the regional specialized palliative home care teams.

Criteria for invitation were the likelihood of having a higher death rate within the hospital department and/or outpatient services based on the annual statistics and therefore high exposure to communication with patients in the dying phase and their FC. As patient representatives, we invited members of the hospital’s patient advisory council. For FC, we approached FC of patients who had died in the palliative care unit at the university hospital and who provided support to the patient on a regular basis during the last days of life until death. We invited FC based on the list of patients that had died within the previous three months and in close consultation with the unit’s head physician in order to not add to the FC’ distress.

Data collection

We conducted the focus groups between November 2019 and February 2020. All focus groups took place at the Inselspital, Bern University Hospital and were conducted in Swiss German (the mother tongue of the participants). There was no monetary incentive given to participants in exchange for participation. A total of 30 persons participated in the five focus groups with five to eight participants per group. Each focus group was composed of participants of the same type, i.e., there was a focus group for nurses (n = 5), one for physicians (n = 6), one for medical students (n = 6), one for patient representatives (n = 8), and one for bereaved FC (n = 5). The majority of participants were women (n = 23). Except for the nursing focus group, all other focus groups had at least one male participant. The focus groups discussions lasted 114 min in average (range: 101–126 min).

The focus groups were led by SJF, a female communication scientist specialized in health communication and TG, a male internal medicine resident physician. All focus group discussions followed the same focus group schedule, which we developed within the research team in several cycles. We showed participants a vignette describing a conversation between a health professional and a dying patient and we asked them to imagine how it would feel, if they had such a conversation in the next few minutes (either as a health professional, as a potential dying patient or as a relative). Further, we asked about aspects that would be essential for them when having a conversation about the last days of life, and in particular, regarding verbal and nonverbal communication components and the context for such conversations.

Analysis

After obtaining written consent from the participants, we audiotaped the focus groups, coded, and analyzed them directly from the audio with the aid of NVivo 12 Pro for Windows, a qualitative data analysis software package (QSR International Pty Ltd 2018). We employed reflexive thematic analysis following the six steps described by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun and Clarke2021). SJF coded and performed the main analyses in close collaboration with SCZ, a psychologist with experience in palliative care and in qualitative research, and kept notes throughout this process as a form of audit trail. All recordings were coded inductively, first as close as possible to the participant’s statements, and then by grouping all codes into preliminary thematic clusters. The thematic clusters were discussed at different instances among all co-authors. SJF and SCZ defined the final themes by ensuring the fit of the final themes with the data from all focus groups, in a process consistent with our critical-realist and contextualist stance. We translated the quotations accompanying the themes and subthemes from Swiss German to English.

Results

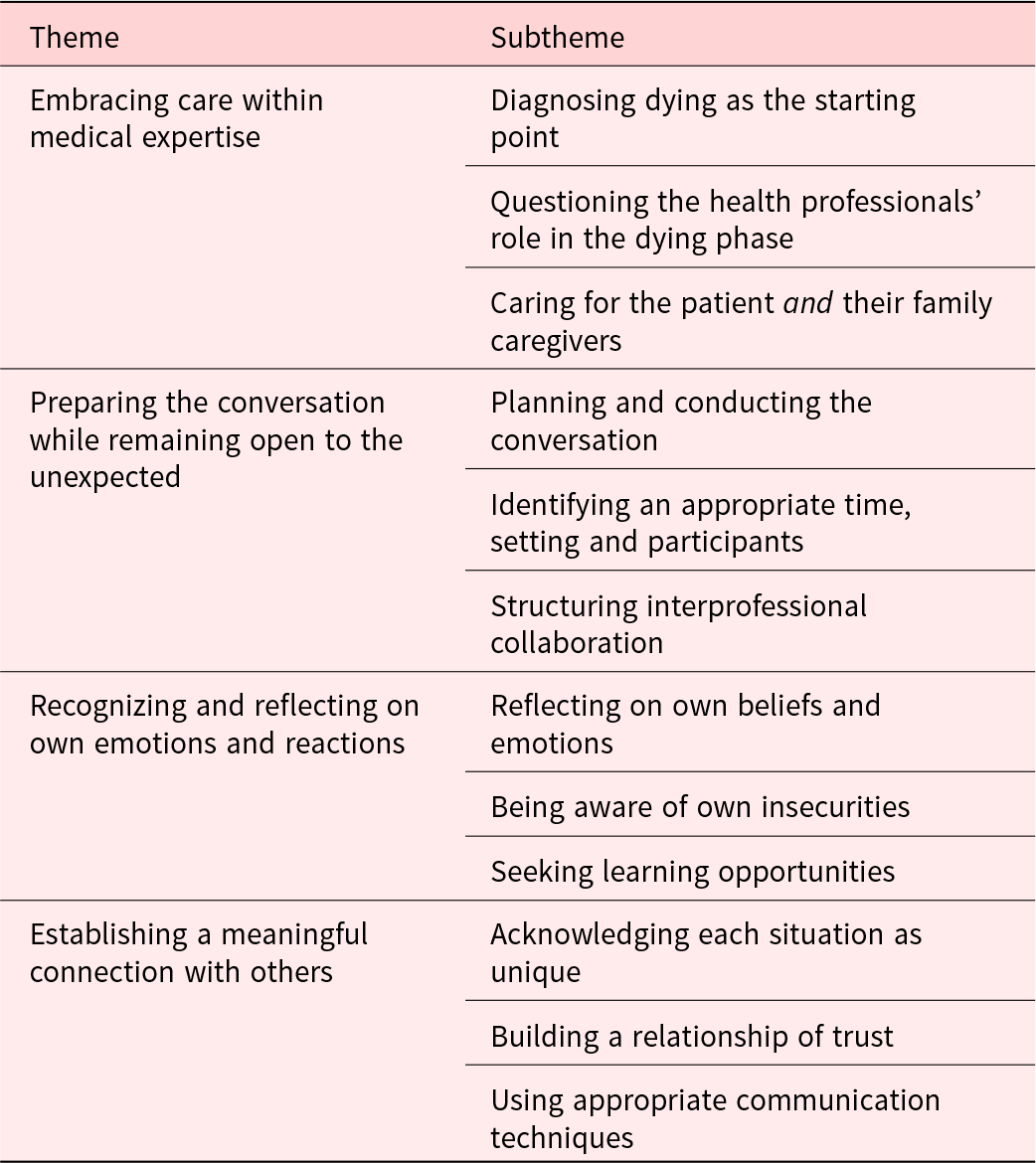

We identified four main themes across the five focus groups under which the essentials of communication about approaching death could be grouped: (1) embracing care within medical expertise, (2) preparing the conversation while remaining open to the unexpected, (3) recognizing and reflecting on own emotions and reactions, and (4) establishing a meaningful connection with others. The themes contain the different building blocks to the conversations, starting with essential prerequisites to the conversations, including their main characteristics and organization (Themes 1 and 2), followed by the need to remain self-aware (Theme 3), and finally, about what matters the most when establishing a meaningful connection with patients and their families and conducting the conversation (Theme 4). For an overview of themes, refer to Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of themes and subthemes

Embracing care within medical expertise

In the context of approaching death, participants emphasized that it was not only the biomedical knowledge about illnesses which was important, but also seeing the person beyond the illness itself, considering and connecting with them as human beings during these discussions. The main subthemes identified were: (1) diagnosing dying as the starting point (2) questioning the health professionals’ role in the dying phase, and (3) caring for the patient and their FC.

Diagnosing dying as the starting point

This subtheme was discussed among medical students and professionals as one of the most important preconditions for initiating a conversation about approaching death. Medical knowledge about how to diagnose dying as well as expert knowledge about the dying process were seen as crucial prerequisites for these conversations. If there was no awareness that the patient might be dying in the next few days or hours, the starting point for having such a conversation would be missed. In addition, participants also referred to the difficulty of having discussions about approaching death when patients had had no earlier indication that their condition was not improving and that their treatment goals needed to be changed. A medical student highlighted diagnosing dying as a key trigger for initiating the conversation:

It [diagnosing dying] is really important, because otherwise, if you miss it, then you never have the conversation. (focus group 1, medical student 2)

Other participants also emphasized the importance of diagnosing dying. They further highlighted the great impact of recognizing the beginning of the dying phase, as it helped relieve tensions and often signaled the beginning of a slowdown of the daily hospital routine and of a feeling of calm around the patient:

Just, the step before, until it’s clear [that the patient is dying], that’s what makes it difficult sometimes […] once it’s clear, there’s a deceleration around the patients. (focus group 4, nurse 1)

I think the tension is there for everybody, including for the patient and the family members […] And I have often experienced that when you have talked openly about the fact that the situation has changed and you are now taking a different path or doing other therapies, uhm, that it then automatically becomes calmer, not only on the part of the nursing staff, but also on the part of the family caregivers and the patient. (focus group 4, nurse 4)

Questioning the health professionals’ role in the dying phase

Some participants wondered whether health professionals, especially physicians, had a role in this very intimate last phase of life, particularly once the dying patient and the FC were well organized and cared for. Physicians and nurses discussed the fact that as health professionals they were trained to intervene in order to save lives rather than to support and accompany a dying person and their FC. While both groups felt this was needed, not everyone did regard it as their main professional competency in this phase:

We are actually first trained to intervene, to act, to be active. And in a way, the focus is now to accompany, which emerges with time, but which is also the primary goal now […]. And that is perhaps quite good, that when someone is in the dying phase, that then the family members are the first ones who belong at the bedside, and that is also sometimes a very intimate thing, the doctor does not always have to be there. […] So if the person and the family members are doing well, then I often just make a social visit in order to show sympathy but I have no role anymore. (focus group 5, physician 1)

Caring for the patient and their family caregivers

All participant groups described the FC as being an important resource to the dying patient at the end of life as the primary focus of the conversation. FC were seen and also mentioned often as having different concerns than the patient and highly appreciated it when health professionals also cared for them. As a result, participants highlighted that it is essential for health professionals to not only focus on providing care for the dying patient but also for their FC:

I often experience that the family caregivers have completely different questions than the patient and sometimes it’s also good if you break it down or you explain it to them first or talk to them in a second step. (focus group 4, nurse 2)

Often you talk to the family caregivers afterwards, outside the door and usually in great detail. […] There are also […] all the questions, “what happens when he dies” and what happens in this or that case. (focus group 5, physician 4)

Even towards us, as family caregivers, there was always someone ready to talk, which was great. (focus group 2, patient representative 3)

What was particularly important when including the FC was that the patient was not lost of sight and that if still conscious, it was important to have the patient as the primary focus of the conversation:

I find respect for the patient, for the dying, primary and the information goes primarily to him and not to the family caregivers […] and therefore, ask who should be there. (focus group 2, patient representative 5)

Preparing the conversation while remaining open to the unexpected

Participants discussed an underlying uncertainty to many aspects of communicating approaching death. In order to reduce this uncertainty and to use time effectively, they were of the view that thorough preparation for these conversations was crucial. The subthemes identified were: (1) planning and conducting the conversation, (2) identifying an appropriate time, setting and participants, and (3) structuring interprofessional collaboration.

Planning and conducting the conversation

Participants from the health professional groups stressed that a thorough preparation based on the patient’s history was essential, in order not to take away much of the valuable time that patients have left. In all groups, different components of the conversation were mentioned: opening the conversation, assessing patients’ and families knowledge (awareness) of the current situation, sharing the prognosis, exploring wishes and needs regarding the dying phase, clarifying and adjusting therapy goals, providing knowledge regarding the dying phase, care planning and follow-up after death, and closing the conversation. In addition, while they agreed that it was important to come up with a potential agenda for the conversation in advance, it was imperative to remain flexible and to structure the actual talk according to where the patients’ and FC were at:

Even if I feel I know exactly or fairly well where they [patient and family caregivers] are in the process, I never skip the first phase of picking up the need [understanding where people are at]. There just has to be a relative there that I have never seen before, who may be in a completely different stage of the process, and then you are already in the fray. […] especially if you think you know the situation, always listen first, how the situation really is […]. And secondly […] what I certainly also prepare well is I ask myself, “do I really have something urgent that I need to know about?,” so that I do not miss it. Or is there something that I need to be informed about or that I need to have said? (focus group 5, physician 4)

While health professionals focused more on exploring wishes and needs, providing knowledge regarding the dying phase, clarifying therapy goals and opening the conversation, members of the patient council were more engaged in discussions about care planning. They emphasized the possibility to engage actively in the planning of the last days as patients and/or FC:

[It’s about] very pragmatic questions, what do I still want to do, what do I still want to get done. What is still important to me, what should be said or not said or written about me after I die. (focus group 2, patient 6)

FC discussed, in particular, the importance of hearing the prognosis. They highlighted the need to be informed with clear words of what they often already assume but in a respectful and empathic way:

My husband, after a while, […] he also didn’t want the infusion anymore. That’s when you knew it wasn’t going to last much longer. That’s when I asked a nurse, and then she said “He’s dying. That’s all I can say.” And I felt that was very respectful […]. So I was very satisfied with that answer, although yes…, of course…, uhm, it hurts. (focus group 3, relative 5)

However, the conversations often included many more aspects, and thus for participants it was important to be prepared to address other topics:

Often it’s about issues, issues like hope and uhm, issues like, are there still conflicts?, are there conflicts in the social network that are still unresolved or any misunderstandings? (focus group 5, physician 6)

Identifying an appropriate time, setting, and participants

Participants in all focus groups discussed that the setting where the conversation takes place often had a major impact on the course of the conversation. A non-involved person in the room, noise, or any other interferences were seen as affecting the atmosphere and intimacy of the conversation. From the participants’ perspective, although the health professionals could not always control all aspects of the setting, they could still aim to create the best possible setting for the conversation:

What I also find important is the positioning and also the combination, how people are distributed in the room […], so when I enter the room, I actively reposition the people, for example that I don’t stand between the family caregivers and the patient, or for example that a relative certainly sits next to the patient, so that he can be close to him, not that I have another relative somehow in the back and I am between them. (focus group 5, physician 5)

Regarding a specific timing and time for the conversation, participants agreed that there is no ideal time for having these conversations and they described that the conversations evolved as part of a process, mostly as the product of rather short conversations. All groups highlighted the importance of providing a moment of privacy for this very intimate conversation, whenever possible “among four eyes” (meaning in private, between two people; the professional and the patient) – at least for the first conversation:

The ward round is the wrong time, I have the feeling. Then everyone rushes in with the trolleys, then there’s another nurse, if possible another student and others, and then you have to talk about incredibly intimate, very difficult topics – I don’t find it very amusing for the assistant [resident] either, because they can’t be themselves either, because the nurses are looking at what they are doing right then. And also for the patient, I find it horrible, they are lying there and we are all standing around them and we are dousing them with bad things. (focus group 4, nurse 2)

My experience is that those kinds of conversations – unless the family is well prepared, by whoever they’ve seen before – are initial conversations and then you usually meet hours later or again the next day and discuss it all again. (focus group 5, physician 6)

Further, participants suggested that time constraints that were already known before the talk should be communicated in a transparent manner and at the beginning of the conversation, as patients may otherwise react with discomfort; or that when having interruptions, it was better to come back later to be able to be fully present in the conversation. The relevance of the setting where the conversation takes place was discussed among all focus groups. From the participants’ perspective, although the health professionals could not always control all aspects of the setting, they could still aim to create the best possible setting for the conversation:

What I also find important is the positioning and also the combination, how people are distributed in the room […], so when I enter the room, I actively reposition the people, for example that I don’t stand between the family caregivers and the patient, or for example that a relative certainly sits next to the patient, so that he can be close to him, not that I have another relative somehow in the back and I am between them. (focus group 5, physician 5)

Structuring interprofessional collaboration

Participants from all focus groups agreed that during the last phase of life, the dying patient and their FC were at their most vulnerable. They are seen as experiencing a crisis, in which they need to rely on trustworthy, reliable health professionals who support and guide them through the situation. Thus, requiring very good coordination and arrangements within the team, excellent flow of information, timely involvement of other professions if needed, as well as a designated contact person who was available 24/7. Important to this aspect was that much of this work should occur in the background, so that time with the patient and the FC was left for essential topics:

That makes a lot of difference, because the patient also feels taken more seriously, they also have the feeling that the team communicates with each other. It is not…one day someone from the team stands there and tells exactly the opposite of the other. Especially when many disciplines are involved, it is incredibly important, especially in such a critical phase, I would say, that you have the same line of communication […], otherwise it drives the patient and the family caregivers crazy and also makes the institution itself untrustworthy. (focus group 5, physician 5)

What I did not like was when so many people were standing around the bed and they were still negotiating what it’s going to look like. And uhm, ‘what do you want now?’, ‘do you want to take her home again?’ or ‘do we want to transfer her?,’ Yes, that… I think, should not be done in front of the patient. (focus group 3, relative 4)

It is about offering support and giving a perspective despite everything that will happen in the next few days and hours, and that you don’t just abandon them after such a conversation […]. (focus group 5, physician 5)

That […] what I have missed […] was a contact person. That they say you are coming now [to the hospital], you can turn to…, that you simply have someone else whom you can maybe ask something or get one more piece of information. (focus group 3, relative 3)

Recognizing and reflecting on own emotions and reactions

Accompanying dying patients and their FC was described as challenging for health professionals with the potential to affect them emotionally more than expected, on a professional as well as personal level. To be able to sympathize but not to suffer, participants suggested that health professionals needed to be aware of their own emotions and to reflect on them in order to remain able to take action. Three subthemes were central to this process of self-reflection: (1) reflecting on own beliefs and emotions and (2) being aware of own insecurities and (3) seeking learning opportunities.

Reflecting on own beliefs and emotions

Participants mentioned that personal convictions regarding dying and death or different cultural backgrounds could potentially impose unnecessary demands on the dying person and/or their FC. Therefore, the more the health professionals knew their own attitudes and values, the better they would be able to distinguish between their own priorities and the needs of the patient and the FC. Reflecting upon and being aware of one’s own beliefs and emotions during the conversations also provided an important basis for an authentic conversation:

Perhaps also [reflect] beforehand, ‘am I prepared to get involved with this person at all?,’ I think that if I know my own point of view, then I can express it better and take on the patient’s point of view. (focus group 1, medical student 2)

I think authenticity is important, no matter how you go in there, whether you are happy or sad, just being authentic, not pretending anything. It doesn’t matter whether you are a relative or a doctor who is conducting the conversation with the relative or with the patient himself. I think authenticity is very important there. (focus group 2, patient representative 7)

It [showing emotions] also makes for professionalism, in that you are also genuine, that it is so professional that you can show, “hey, these situations still touch us”. (focus group 4, nurse 1)

Being aware of own insecurities

Participants were aware that conducting conversations about approaching death was a process filled with different uncertainties and difficulties, especially due to a lack of experience in dealing with situations when care for the dying is the main concern, rather than medical interventions. As they often saw themselves as experts, health professionals mentioned that when experiencing powerlessness, many of them rushed to give explanations or to do things for the patients rather than to try to stay with the emotion they were experiencing when death was approaching. Therefore, they mentioned the need to be aware of the risks of using (too) many technical terms when feeling overwhelmed and powerless, or of filling pauses with unnecessary words, was mentioned:

Providing medical expertise is easy…, the other part is high art. Imparting expertise, I mean, you can read about it, you can learn it, it’s always a little bit similar, this is stiff, the other part is…is soft, is flexible. […] from my experience, you often use medical reasoning and facts when you are feeling helpless, or when you just don’t know what to do next. Beginners need expertise, […] medical expertise. It’s all clear, you have to give professional expertise too, but at the right moment, in the right portion and with the right words. (focus group 4, nurse 2)

I don’t know if that’s something that comes with experience. I always have to pull myself together very tightly, it’s always easy to fill in gaps like that by rambling, just so that something is said. (focus group 5, physician 3)

Seeking learning opportunities

Participants were convinced that it is essential to seek learning opportunities such as debriefings, learning through role models or training on-the-job in order to reflect on their own work and on their own needs. Juniors, in particular, were seen as being dependent on seniors to be “guided” as they discover the broad variety of possible situations when death is approaching by accompanying them and providing feedback. Time constraints in daily clinical routine posed challenges to implement these strategies. However, in order to develop their own skills, they described as essential being able to learn more from the perspective of others, for example through receiving feedback. For those senior enough to be role models, it was important to be aware of how they could purposefully engage in this role with their students:

About learning: it’s just like, I’ll say, administering…prescribing chemotherapy or learning to have an operation, you don’t learn it overnight, you don’t learn it in a communication course with actors, you learn it through experience and through role models. And most people learn by example. And all of us here as – let me say – experienced physicians, should try to implement such things as role models and take our people with us [junior clinicians] and evaluate together with them what we have actually done. (focus group 5, physician 6)

Establishing a meaningful connection with others

Every situation as well as the needs of the dying person and their FC were described as unique and requiring specific communication skills. The subthemes identified were: (1) acknowledging each situation as unique, (2) building a relationship of trust, and (3) using appropriate communication techniques.

Acknowledging each situation as unique

Participants highlighted that each encounter with a dying patient and their FC is unique. Therefore, the health professionals’ focus should be on understanding the actual needs, values, attitudes, fears and questions of the persons in front on them and assume that they do not know what is important to a patient and a family until they have (repeatedly) asked the persons involved:

We must not forget, we [professionals] go as a healthy person, but we have a seriously ill, dying person in bed and they sometimes have very different needs than we feel they should have. (focus group 4, nurse 2)

One should be open that the patient wants to take responsibility for his decisions and he is allowed to do so. What I [as a physician] think is appropriate is only predominant if it really is futile care. Then I have the right to say that makes no sense at all. (focus group 5, physician 6)

Consequently, professionals thought patients should be involved in the decision-making process with their last wishes being respected whenever possible:

It is more about following the wishes [of the patient] and not a plan of action, so, I don’t think we have to plan it [the proceeding] in that sense, but rather the patient says […] what is important to him in this time, what his wishes are. We [professionals] actually have to follow them; we do not determine the plan. (focus group 4, nurse 4)

Building a relationship of trust

In the last phase of life, where all involved are very vulnerable, participants agreed that it is essential to lead conversations about approaching death with great care allowing for trust to develop between each other, even if time was limited and there was not a prior relationship with the patient and/or their FC. There was much discussion in all groups about who should actually have the first conversation with the dying patient (and the FC) about approaching death. Discussion ranged from the most senior physician present to the professional who knows the patient and the FC the best. All agreed that it is most suitable, if someone who has already established a relationship with a certain level of trust to those concerned leads the talk:

Perhaps one should get away from the fact that it is always – or normally – the doctor, perhaps it should simply be a trusted person. […] maybe a nurse, or whoever, […] It brings more if it is a person who already has a certain trust relationship, where a certain relationship exists, it is perhaps more favorable than to have it done by – let’s say – a rather boisterous doctor. (focus group 2, patient representative 1)

If I don’t have a relationship with a patient beforehand […] and there is an acute deterioration during my shift, then that stresses me out a bit. (focus group 5, physician 2)

Accompanying dying patients and their FC not only as professionals but also as human beings was not to be underestimated. Participants often highlighted that for trust to develop, it was important to have compassionate communication between professionals and patients and to see the patient beyond the illness:

The health professionals should not see the patient as, uhm…they should see him as a human being and not as a palliative case, “that’s the liver” or “that’s the lung” or “that’s the palliative situation,” but as a human being […]. Keep dignity [for the patient], this is often experienced that the patient lies in his bed and everyone stands around, they don’t even sit down […] and then they talk about him down there, then he has no dignity anymore. (focus group 2, patient representative 1)

At the end of the day, we [professionals] are also there as human beings, just like they [patients and their families] are, and I think at the end of the day, profession is a secondary matter. (focus group 4, nurse 4)

In order to establish trustworthy rapport with patients and FC, participants highlighted a variety of further aspects, such as being empathetic, having time to listen, or being honest, which they felt were central to having a respectful and open communication in this vulnerable phase of life:

That professionals are empathetic towards me [as a patient], but that they are also honest, so they don’t want to kind of belittle or go easy on me, that they take enough time, that I [as a patient] don’t feel like they’re stressed, that they include my values, and that they’re also available if something unexpectedly goes badly. (focus group 1, medical student 6)

For me, it’s very important [that health professionals] take time to listen, to be empathetic…and once nothing is said, to be able to endure the silence, that’s very difficult for many people, and above all to be honest with the situation and not pretend. Respond to the situation, ask questions and very subtly observe what the patient’s mood really is. From my own experience, as a patient, you just get run over because the doctor doesn’t have time. (focus group 2, patient representative 6)

Using appropriate communication techniques

All groups agreed that in conversations about approaching death it was necessary to leave enough space for the dying person and their FC. Techniques such as establishing eye contact, using honest words, naming unspoken “things in the room,” allowing for pauses, or mirroring and adapting speed and level of speech, were emphasized by all participants as important to respond sensitively to the needs of dying patients and their FC:

At that moment, everything around the patient and the caregivers doesn’t count, […] put the phone away when you are in the room…now the patient and the family caregivers set the pace for all the conversations. (focus group 4, nurse 4)

I try to meet the needs of the people concerned nonverbally […] if they look at you, then I also look at them, and if they look more like this, then I also look like this, and if they speak quickly, then I also speak more quickly […] I think that mirroring nonverbally and verbally is important in order to understand each other and that they feel met. (focus group 5, physician 4)

You need to adapt the language to the level of the patient and I mean that in a multi-layered way […]; I mean also to the level where someone stands. If one would speak to me now very very amateurishly, and one knows what my [nursing] background is, then it would bother me just as much as if they would express themselves only in technical terms. (focus group 2, patient representative 7)

Further, across all groups, speaking at eye level by sitting down next to the bed of the dying patient was found to be essential particularly in two ways: first, professionals showed that they are of equal value as the person concerned (“not lecturing from above”) and thus preserved the dignity of the patient. By sitting down, professionals also signaled that they are taking some time for this important conversation. Finally, the invaluable impact of a positive attitude and humor was highlighted, even if the situation seemed desperate:

I always think to myself, how would I like someone to tell me, in what setting? Do I want that someone to stand? Certainly not. Go at the eye level, […] sit down, at least come to the level of patient. (focus group, physician 6)

[…] not from above, like the good Lord who is saving us [patients and family caregivers] but from person to person and he [the physician] also still has a bit of humor, despite everything. Humor is also good when you are in the hole yourself [going through a difficult situation]. (focus group 3, relative 5)

And not to forget, to bring some lightness even in a difficult situation, I always find…yes, and partly they [the patients] also make jokes, I have also laughed a lot, it’s not just difficult. (focus group 4, nurse 5)

Discussion

This study identified essential aspects of communication about approaching death from the perspective of physicians, nurses, medical students, bereaved FC, and patient representatives. By focusing on key stakeholders and on communication about approaching death in the last days of a patient’s life (after diagnosing dying), the findings of this study help fill a gap on core aspects of this type of communication, which, despite their importance, remain overlooked in current medical and nursing undergraduate and postgraduate curricula (Olsson et al. Reference Olsson, Windsor and Chambers2021; Scholz et al. Reference Scholz, Goncharov and Emmerich2020; Walczak et al. Reference Walczak, Butow and Bu2016). Among the aspects and attributes integral to these conversations, the necessity of embracing care as part of medical expertise, the need to prepare for the conversation while remaining open to the unexpected, the importance of recognizing and reflecting on own emotions and reactions, and the predisposition to establish a meaningful connection with others, were identified as essential. These main themes can serve as a basic guide for the training of medical students, or from which health professionals, particularly those starting out in their professions, can build upon when engaging in conversations about approaching death with patients and their FC.

We identified that the acknowledgement of one’s role in providing care for dying patients is an important prerequisite for initiating discussions about approaching death. Some clinicians in our study questioned whether they had a role in this last phase of life, and though trainees and clinicians are nowadays more exposed to end-of-life care training (McCormick and Conley Reference McCormick and Conley1995; Michaud and Jucker-Kupper Reference Michaud and Jucker-Kupper2017), the curative perspective, focused on diagnosis and treatment of illnesses, seems to remain predominant in practice (Wilson and Gilbert-Obrart Reference Wilson and Gilbert-Obrart2021). Therefore, more emphasis is needed in encouraging not only junior physicians, but also those in senior positions to acknowledge and become more comfortable with this role. This requires not only communication training, but also the preparedness of clinicians to examine their own attitudes towards death and care of the dying (Childers and Arnold Reference Childers and Arnold2019).

Along with acknowledging their role, diagnostic skills are essential, as the diagnosis of approaching death or the awareness that the patient is entering the dying phase was seen as the essential step to initiate discussions about approaching death. The diagnosis of dying as the trigger for these conversations has been described by others (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Johnson and Dowding2020), and several studies have identified different signs and symptoms associated with dying that serve health professionals to ascertain when such a conversation may be initiated (Domeisen Benedetti et al. Reference Domeisen Benedetti, Ostgathe and Clark2013; Hui et al. Reference Hui, Dos Santos and Chisholm2015; White et al. Reference White, Harries and Harris2018). Importantly, clinicians should be aware that uncertainty has been found to be intrinsic to diagnosing dying but that openness about this fact, greatly helps the decision-making process and the patient’s and FC’s preparation for death (Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Brooks-Young and Brunton Gray2014).

In view of the limited time left for patients and families, our findings also stress the need for health professionals to meaningfully use the patient’s remaining time by preparing for these discussions as thoroughly as possible and to communicate time limitations early in the conversation in a transparent manner. Interprofessional communication and collaboration in this phase are key (Bays et al. Reference Bays, Engelberg and Back2014; De Witt Jansen et al. Reference De Witt Jansen, Weckmann and Nguyen2013), as they improve the provision of high-quality and person-centered care (Eggenberger et al. Reference Eggenberger, Howard and Prescott2020; Lippe et al. Reference Lippe, Stanley and Ricamato2020). Additionally, we found that preparation also requires identifying and designating a contact person for the dying patient and the FC. Finally, in preparing themselves, we found that clinicians should also remain open to the unexpected, as much of the agenda should be dictated by patient and FC needs upon discussion.

To explore patient and FC needs, establishing a meaningful connection with them, may help to understand their fears and what really matters at the specific time to them. We found a broad range of traits that facilitate a meaningful connection: clinicians should be honest, authentic and trustworthy, which they can achieve by being present and compassionate. Several suggestions were made by our participants to learn compassion via reflective practices, experiential learning or with clinical mentors, if possible early on in clinical training programs and tailored to individual needs, as it has also been suggested by others (Brito-Pons and Librada-Flores Reference Brito-Pons and Librada-Flores2018; Krishnasamy et al. Reference Krishnasamy, Ong and Loo2019).

Across all themes, participants highlighted the importance of acknowledging FC at every step, thus supporting the established palliative care principle of taking together “the patient and the family and or significant others as the unit of care in assessment of needs” (Mount et al. Reference Mount, Hanks, McGoldrick, Fallon and Hanks2006). It is well known that at the end of life, facilitating the FC’ understanding that their relative is dying (Caswell et al. Reference Caswell, Pollock and Harwood2015) promotes a trusting relationship with the health professionals (McQuellon and Cowan Reference McQuellon and Cowan2000), not only because FC are advocates for the patient but also because they bring their own specific needs and questions (Zambrano et al. Reference Zambrano, Löffel and Eychmüller2019). As a result, medical education should not only prepare to care for the dying but also to care for the families, before and after the death of a significant other, as some may be at risk of developing complicated grief (Mason et al. Reference Mason, Tofthagen and Buck2020) and to have difficulties when grieving.

Not least of all, our findings underscore the need to acknowledge that dealing with death and dying can have personal consequences for health professionals. Indeed, studies have shown that when caring for patients at the end of life, physicians and nurses can experience a range of emotions that include powerlessness, resentment, guilt, emotional pain, grief but also happiness, satisfaction or gratitude (Sinclair Reference Sinclair2011; Zambrano et al. Reference Zambrano, Chur-Hansen and Crawford2012, Reference Zambrano, Chur-Hansen and Crawford2014). Unacknowledged, this emotional work may lead to moral distress, burnout and to a reduced job satisfaction in health professionals (Jeon and Park Reference Jeon and Park2019; Parola et al. Reference Parola, Coelho and Cardoso2017). Therefore, knowledge and practice of self-reflection, self-awareness and self-care is required, as is the acknowledgement that health professionals can feel personally involved (Childers and Arnold Reference Childers and Arnold2019). In addition, systematic opportunities for supervision, providing feedback, and debriefing in the clinical setting are essential, as is the exposure to role models.

Limitations and strengths of the study

A potential limitation of this study is that the majority of participants were linked to the same university hospital. However, given the complexity of cases seen in the acute hospital, this may have helped to identify a variety of aspects that would be useful in other contexts where dying takes place. Another potential limitation of this study is that, as in most focus groups research, group dynamics may have hindered the sharing of experiences of some participants. While this did not seem to be the case in the focus groups with nurses, medical students, and patient representatives, we identified some of these dynamics in the focus groups with physicians and families. To manage them, the moderators focused on giving voice to those participants who remained more silent, so that they could also express their views. Due to similar reasons of potential unfavorable group dynamics, focus groups were held separately per stakeholder group aiming to maximize participant comfort in order to allow them to express their thoughts directly and without being hindered by any role expectations or attributed hierarchy levels. This, however, could be a potential limitation since participants of the same group may not have challenged each other in the same way as if the groups had been composed differently. Finally, though five focus groups may seem a small sample size, studies have shown that it is an appropriate sample size from which to reach meaningful conclusions (Hennink et al. Reference Hennink, Kaiser and Weber2019).

Among the main strengths of this study is that it gathered the views of the major stakeholders in these discussions, including the views of patient representatives, and merged them in order to achieve a “greater picture” of what is important when communicating about approaching death. Similarly, it was an advantage that the focus group moderators were not clinically linked to any of the participants, and would therefore be unlikely to have a future clinical or professional relationship with them, meaning that all participants could speak freely without any social desirability bias, nor fearing any potential negative consequences in future encounters. Finally, by focusing on communication about approaching death, a very distinct phase of the end of life, this is one of the few studies to provide focused strategies about how to prepare for and communicate in this clinical situation.

Conclusion

Dealing with death and dying remains a complex and challenging task at a personal and professional level for health professionals. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown even more poignantly the significance of these sensitive conversations and the need for further research, education, and on-the-job training for health professionals in order to feel skilled to engage in end-of-life scenarios.

In this study, we identified essential aspects of communication about approaching death that may serve as the core basis for developing communication models and educational interventions. These include the need for health care professionals to have sound clinical knowledge to diagnose approaching death, to employ a compassionate and human approach to the relationship with patients and their families, and to engage in constant self-reflection and self-care. All of which should be learned, practiced, reflected on through active engagement and constant exposure to these conversations. This requires not only professional competence but also personal engagement, which may even involve removing the “white coat,” accepting one’s own limitations and mindfully establishing a relationship with the other. Through accompanied confrontation with the unique challenges of communicating with dying patients and their FC about approaching death, health professionals will be able to find their own unique place in supporting them at this sensitive time.

Acknowledgments

The authors are particularly thankful with the participants of the focus groups who greatly supported the project by participating lively in the discussions and for generously dedicating their free time. Furthermore, the authors are very grateful for the commitment and knowledge provided by the members of the advisory board of the study, as well as the international palliative care and communication experts.

Author contributions

SJF, TG, BGM, FMS, KPS, SG, SE, and SCZ made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study, SJF and TG to the acquisition of data, and SJF, TG, and SCZ to the analysis and interpretation of data. SJF and TG drafted the article with the support of SCZ, with BGM, FMS, KPS, SG, SE, and SCZ revising it critically for important intellectual content. Finally, SJF, TG, BGM, FMS, KPS, SG, SE, and SCZ approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swiss Cancer Research Foundation (Grant No. KFS-4522-08-2018).

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

The Bernese Cantonal Ethic Commission reviewed the study (REQ-2019-00977) and considered that the study could be performed without formal ethical approval.