Descriptive political representation of minorities in national legislatures is an imperfect but extremely useful tool for assessing their access to political decision-making and degree of involvement in national politics. In Western Europe, the French Muslim minority is the largest in absolute numbers and also the largest as a proportion of the national population. One would expect to observe more than forty Muslim-origin MPs in the French Assemble National if they were proportionately represented. Instead, there were only eight Muslim-origin MPs representing mainland France in the French parliament in 2017, four in 2012, and none in 2007. Considering that the French Muslim community is relatively old and established, hailing from formerly French territories such as Algeria, which became part of France in 1830, such a low number of Muslim-origin MPs indicates particularly significant descriptive underrepresentation. In contrast, in neighboring Belgium, the Muslim minority has already reached and surpassed parity, and has been overrepresented in the lower chamber of the Belgian national parliament, having ten MPs (in both the 2010 and the 2014 elections) instead of eight that would be expected based on the share of Muslims in Belgium’s population. As we demonstrate, such variation in descriptive political representation of Muslim minorities across European countries is not limited to these two examples.

We present here a new cross-national data set, which includes 635 seats filled by Muslim-origin MPs in the lower chambers of national parliaments of twenty-six European polities in three legislative cycles between 2007 and 2018. As of the third and last of these cycles that we examined, there were 224 Muslim-origin MPs serving in the national legislatures of these twenty-six European countries. Our data set includes the compositions of legislatures formed after three national elections for each polity to address the potential biases of generalizing from the outcome of a single election. This data set is a major improvement on previous comparative studies on this topic because it is the first of its kind to examine Western and Eastern European polities together, hence combining predominantly immigrant and predominantly native Muslim minorities.

We lay out and test an argument about the positive spillover effect of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity on the levels of descriptive representation of religious minorities. We suggest that the constitution of a polity as a union of multiple ethnocultural communities, reflected in concrete state policies and institutional arrangements, may be conducive to better descriptive representation of religious minorities as well, including Muslims, who were not originally envisioned as one of the nation-constituting communities in European polities. The results of multivariate regression analysis provide support for our hypothesis about the positive impact of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity on the levels of descriptive representation of European Muslims. We supplement our findings with congruence testing in four brief case studies: Belgium, France, the Netherlands, and Bulgaria.

Our Argument: Institutionalization of Ethnocultural Diversity and Muslim Minority Representation

We argue that institutionalization of ethnocultural (including linguistic) diversity in a polity creates an environment that is conducive to a more proportional representation of religious minorities, even if such minorities were not originally targeted in the process of institutionalization. Such a multiethnic and multicultural institutionalization inculcates the idea that the polity is made up of multiple collectivities with perceptibly different cultural features. In contrast to a polity conceived as a union of individuals, who might or might not exhibit cultural differences at the individual level, polities, which institutionalize a multicultural vision of their nation, are conceived as a union of distinct collectivities with different ethnic or linguistic features. We conceptualize institutionalization of multiple collectivities as recognition of ethnocultural and linguistic diversity through state policies and legal arrangements. We limit our focus to formal institutional arrangements and policies, while excluding implementation practices and informal declarations, as formal arrangements are less susceptible to subjective interpretations and more resistant to political changes, hence having a much more consistent and long-lasting effect on the ways in which a particular polity is conceived.

Conceptually, such polities were defined by Canadian political philosopher Will Kymlicka (Reference Kymlicka1995) as multicultural(ist), multinational, or polyethnic states, guided by the principles of recognition, acceptance, and promotion of cultural differences. However, Western multiculturalism is not the only source of state recognition of ethnocultural differences and their institutionalization. Many scholars of Soviet policies toward ethnic diversity, also known as the Soviet “nationalities policy,” argue that the Soviet Union promoted ethnic particularism (Slezkine Reference Slezkine1994; Aktürk Reference Aktürk2011), valorized the ethnic diversity of its citizenry (Suny and Martin Reference Suny and Martin2001), and that the Soviet Union can be depicted as “the first affirmative action empire” in the world as such (Martin Reference Martin2001; Hirsch Reference Hirsch2005), decades before affirmative action and multiculturalist policies were implemented in Western polities. These Soviet policies toward ethnic diversity influenced all Eastern European polities that became communist after World War II (Connor Reference Connor1984). “Communism preserved, solidified, and perhaps even exacerbated ethnic diversity by institutionalizing ethnoterritorial structures, classifying citizens by nationality, changing patterns of ethnic settlement, and providing opportunities for ethnic mobilization” (Rovny Reference Rovny2014, 679). The most consequential institutional difference between many (but not all) Eastern European polities and most (but not all) Western European polities is precisely such an institutional legacy of multiethnic nationhood, which was often, but not always, originally built or consolidated under Communism in Eastern Europe. In contrast, indirect or informal affirmative action policies found in some Western European polities “as part of what may be described as an administrative rationalization of antidiscrimination law enforcement” (Sabbagh Reference Sabbagh2011, 470) may not amount to the institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity, unless they specifically define different ethnolinguistic groups as constituent components of a multiethnic polity.

The institutionalization of ethnocultural differences via recognition of multiple groups as constitutive units of the political community and reflection of this heterogeneity in state policies are not directly connected to state policies toward religion, let alone to Muslim minorities. If there was such a direct connection, it would render our argument endogenous, if not tautological. The origins of institutionalization of ethnocultural differences in both Western and Eastern Europe were about the accommodation of Christian-heritage ethnolinguistic group identities, such as Flemish and Walloon in Belgium; English and Scottish in the United Kingdom; Finns and Swedes in Finland; Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes in former Yugoslavia; as well as Croats and Serbs, and Montenegrins and Serbs in present-day Croatia and Montenegro, respectively. Consider Belgium, the country with strongly institutionalized ethnocultural diversity: neither Flemings nor Walloons are Muslim, and their struggles that shaped Belgium as a bilingual, binational, ethnofederal polity had nothing to do with Islam or Muslim minorities. And yet we argue that Muslim minorities electorally benefit from this previous institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity.

We hypothesize that the multilayered and culturally segmented depiction of the polity along ethnocultural lines may also have a positive spillover effect on religious (i.e., Muslim) minority representation for the following reasons. First, it might legitimate or even motivate political party elites, or “gatekeepers,” to nominate Muslim candidates for the national parliament. Official recognition of ethnocultural diversity creates heightened awareness of ethnic and linguistic differences (e.g., Flemish and Walloon, English and Scottish, Montenegrin and Serbian) and the need for their equitable representation to ensure the stability and the legitimacy of the political community. Thus, it is easier for party elites in such polities to conceive of the Muslim religious minority as just another, albeit almost always newer and smaller, identity group that deserves to be nominated and represented in the parliament. Second, Muslim individuals may be more motivated and self-confident to run for office in a country that recognizes multiple ethnocultural groups, emboldened by their observation that the expression of cultural differences is not frowned upon but taken as a given in their polity. Ethnic or linguistic identities may be conceived or perceived as representing different ways of life (e.g., Flemish, Scottish, or Sami way of life), similar as such to the perception of different religious identities as representing different ways of life (e.g., Jewish or Muslim ways of life). Thus, inspired by members of different ethnolinguistic groups proudly campaigning and seeking office, members of Muslim minorities may likewise campaign for office, perhaps also more readily expressing their religious identity. Third, in a polity with two major ethnolinguistic groups and a very high level of multiethnic institutionalization, the smaller Muslim minority may appear as a critical minority group that identifies with the overarching (e.g., civic, supraethnic, territorial, etc.) national identity. This is indeed the role that Muslim minorities occupy in many polities with high levels of multiethnic institutionalization such as Belgium and the United Kingdom in Western Europe and Montenegro in Eastern Europe. Muslims’ identification with Belgian (rather than Flemish or Walloon) or British (rather than English, Scottish, or Welsh) national identity could in turn motivate both the nomination and the election of more Muslim minority representatives. Likewise, in close competitions between more nationally oriented (i.e., Belgian or British) and more subnationally oriented (i.e., Flemish or Scottish) parties, both sides may have incentives to nominate Muslim-origin candidates to win over the Muslim vote, although more nationally oriented parties would have greater incentives to do so due to the likely more supraethnic/national territorial identification of Muslims.

Literature on Descriptive Representation

Representation is an essentially modern concept with multiple different connotations such as “acting for” and “standing for” as Hanna Pitkin argued, and although this concept is associated with democracy at present, “through much of their history both the concept and the practice of representation have had little to do with democracy or liberty” (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967, 2). The kind of representation that we examine most closely resembles what Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967, 60-91) called “standing for” in terms of “descriptive representation.”Footnote 1 Descriptive representation of disadvantaged minority groups has many positive effects, which we briefly discuss in our conclusion.

According to Bloemraad and Schönwälder (Reference Bloemraad and Schönwälder2013, 572), “scholarship on minority representation in Europe is in its infancy,” and this is even truer of comparative studies of Muslim minority representation. While there are some detailed empirical surveys and diagnoses of political underrepresentation of Muslim minorities, especially as case studies of specific European polities, causal arguments seeking to explain the cross-national patterns of Muslim minority representation in European politics are far fewer.Footnote 2 Some of the most significant comparative empirical works on Muslim minorities in Europe and the Americas are edited books, and due to the different methodological and theoretical orientations of the contributing authors (Haddad Reference Haddad2002; Sinno Reference Sinno2009; Bird, Saalfeld, and Wüst Reference Bird, Saalfeld and Wüst2011), the otherwise very valuable contributions of these edited books are often not organized to consistently test or demonstrate the explanatory power of the same causal factors throughout different country-specific case studies. Nonetheless, they are unanimous in diagnosing the underrepresentation of Muslim minorities in almost all the Western legislatures.Footnote 3

Existing scholarly literature on descriptive political representation of minorities discusses a variety of factors influencing representation levels. Electoral system design is the most widely acknowledged factor that influences the levels of descriptive representation of minorities. Proportional representation (PR) electoral systems are claimed to be more advantageous in terms of minority representation compared to plurality and mixed electoral systems (Ruedin Reference Ruedin2009; Sinno Reference Sinno2009; Bloemraad and Schönwälder Reference Bloemraad and Schönwälder2013, 570). Hughes (Reference Hughes2016) demonstrates that PR electoral systems are associated with better representation of Muslim ethnic minority women in particular.

The mechanism that links electoral system design to descriptive representation is twofold. First, the more majoritarian the process of elections to the legislature is, the more likely it is to distort the distribution of seats in favor of major parties at the expense of smaller parties. Second, the “winner-takes-all” principle of such electoral systems encourages parties to nominate candidates that are most capable of reflecting the preferences of the median voter. Therefore, such candidates would be more likely to come from the majority ethnoreligious background. PR systems can incorporate various institutional features that distort the translation of votes into seats. For instance, multi-member electoral districts in PR systems may vastly differ in the number of contested seats. Multi-member electoral districts with a smaller number of seats have a higher effective electoral threshold than districts with a larger number (Lijphart and Aitkin Reference Lijphart and Aitkin1994). Consequently, electoral outcomes will be more distorted in such smaller districts. The translation of votes into seats is also distorted through the application of various national or regional electoral thresholds. In some cases, such as Greece (OSCE 2012) and Italy (Cotta and Verzichelli Reference Cotta and Verzichelli2007, 92), the winning political party is rewarded with additional parliamentary seats so that it ultimately obtains a greater plurality or majority of seats in the legislature than its share of votes would suggest.

The current scholarship mostly finds a positive relationship between leftist parties and Muslim minority representation. In many Western European polities, the majority of Muslim MPs are elected from leftist parties, and to the extent that there are reliable ethnoreligiously specific surveys, more Muslims seem to vote for leftist parties than for conservative right-wing parties (Sinno Reference Sinno2009; Bird, Saalfeld and Wüst Reference Bird, Saalfeld and Wüst2011; Dancygier Reference Dancygier2013, Reference Dancygier2014, Reference Dancygier2017). Therefore, legislatures that are more dominated by leftist parties would be expected to have higher descriptive representation of Muslim minorities. The reasons for the electoral affinity between Muslim minorities and leftist parties are more complicated and contested. Leftist parties’ greater propensity to support multiculturalism or minorities in general may be sustaining the mutual affinity. On the other hand, since Muslim minorities are poorer than the general population in most European countries, their economically disadvantaged position might also be the cause of this electoral affinity.

The assumption that positive attitudes toward minorities translate into the public’s greater willingness to vote for minority candidates or into political parties’ greater inclination to nominate such candidates has already been questioned in comparative and single case studies of Muslim minority representation (Sinno Reference Sinno2009; Hussain Reference Hussain2000). For example, public opinion is much more anti-Muslim in Denmark and in the Netherlands compared to France, but Denmark and the Netherlands both have much higher levels of descriptive representation. In a study on the regional legislatures of the United Kingdom, English (Reference English2019) finds no statistically significant impact of anti-immigrant public attitudes on the representation levels of MPs with an immigrant background. He finds, however, a negative relationship for those MPs who belong to racial minorities. On the other hand, Rahsaan Maxwell’s (Reference Maxwell2012) finding in his comparison of Caribbean and Maghrebian minorities’ representation at the local level in France indicates that a less tolerant social environment can be conducive to higher levels of political mobilization and political representation of national minorities.

To the best of our knowledge, large-N cross-national comparative analyses of the variation in Muslim minority representation that include both Western and Eastern European countries are virtually non-existent. In the context of political representation, the role of citizenship as a precondition for voting and being nominated for officeFootnote 4 is related to the native (autochthonous) origin of the Muslim minority, which is the distinctive feature of most Eastern European countries, or to the naturalization rates of immigrant-origin Muslim minorities in most Western European countries. In addition, native status itself may strengthen claims for political representation and encourage minorities to take part in national politics. We must note, however, that a native (autochthonous) versus immigrant distinction should be treated with caution and may be normatively and operationally quite problematic because “arguments of justice do not make a difference between minority groups based on how a group has become a minority or how long a group has been present in society” (Ruedin Reference Ruedin2013, 15). Even more critically, from an operational point of view, any binary classification of native/autochthonous versus immigrant/newcomer Muslim minorities is bound to be challenged given the non-binary variation in Muslim minorities’ longevity cross-nationally as well as within the same polity. A few examples would suffice to illustrate the practical problems with a binary autochthonous/immigrant distinction in relation to Muslim minorities in Europe. French Muslims are typically depicted as immigrants because of their historical origins in North Africa, whereas Greek Muslims are considered native due to the centuries-old presence of a Muslim minority in Greece. However, Algeria, the country of origin for the largest number of French Muslims, was occupied by France in 1830 (later annexed as “French Algeria”), the same year modern Greece came into existence at the end of a protracted rebellion against the Ottoman Empire (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2018). Moreover, many Muslims currently residing in Greece are immigrants, who arrived in recent decades, whereas most French Muslims were born and lived their entire lives in France. The subjective nature of the differentiation when applied to Muslim minorities in Europe becomes even more apparent when we consider many Christian-heritage Balkan nationalists’ (e.g., Bulgarian, Greek, Serbian) claim or allegation that Muslim minorities in their countries are not indigenous but foreigners brought in from Asia by the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 5

Data

In this article, we use an original data set that includes the number of Muslim-origin MPs serving in European legislatures between 2007 and 2018. Data collection was conducted in three cycles–2010, 2014–2015, and 2017–2018, which correspond to the years of access to the MP lists in national legislatures, reflecting the outcomes of most recent elections.Footnote 6

Identifying Muslim-origin MPs by their names is the most common method in the extant scholarship on Muslim minority representation in Western legislatures, even in single country studies (Donovan Reference Donovan2007),Footnote 7 and almost without an alternative in comparative studies (Sinno Reference Sinno2009; Dancygier Reference Dancygier2014, 240) such as the current endeavor. Despite the possibility of a measurement error, inferring one’s ethnoreligious background from his or her first and last name is probably the most common method that people themselves use in their daily lives. Moreover, Muslim identity is not only framed as a religious, but also as a racial and cultural identity by many non-Muslims in Europe, which includes the far right (Froio Reference Froio2018). Therefore, a name-based approach better approximates the ethnoreligious minority representation that we seek to explain. Furthermore, having a Muslim name alone leads to vast discrimination in the European job market, such that a fictional African female applicant with a typical Muslim first name received two and a half times fewer invitations for a job interview in France than another fictional African female applicant with the identical resume but with a typical Christian first name in France (Adida, Laitin, and Valfort Reference Adida, Laitin and Valfort2016). In referring to “Muslim-origin” MPs in the same way we would refer to “Christian-origin” MPs, we seek to emphasize that we are not assuming any form of religiosity or level of religious observance with this appellation.

Data collection was done manually by going through the MP lists of national legislatures in our sample and conducting a subsequent background check on the Internet for each preliminarily identified MP. In the course of data collection and background checks, we also benefitted from the help of researchers who are native speakers of Albanian, Bosniak, Russian, and Turkish. We checked every MP with a Muslim-origin name to confirm whether they are of Muslim origin; and if they were, we counted them as such unless they publicly converted to another religion or publicly self-identified as non-Muslims or atheists. There were a number of cases of MPs with Muslim-sounding names of Middle Eastern origin, where we checked and confirmed that they are of non-Muslim origin, and hence did not count them as Muslims.Footnote 8 Likewise, a French MP with a Muslim-origin name (Malek Boutih) openly stated on a TV show that he was no longer MuslimFootnote 9, and we did not count him as one of the Muslim-origin MPs included in our data set and calculations. The opposite phenomenon, namely, a non-Muslim MP who converts to Islam, is extremely rare, and if and when it happens, it would be widely reported in the media.Footnote 10 Indeed, there was one former Dutch MP (2010–2017) from a far-right Party for Freedom (PVV), Joram van Klaveren, who converted to Islam, and his conversion was widely reported in European and non-European media (including media of the Muslim-majority countries), but he converted in early 2019, when he was no longer an MP. In short, we did not automatically accept all MPs with traditionally Muslim or Middle Eastern names as Muslims in the sense that we individually checked every MP to confirm that he/she is indeed of Muslim origin and that he/she did not publicly self-identify as non-Muslim. We do not assume or expect Muslim-origin MPs to be practicing or religiously observant Muslims, just as many if not most Christian-origin MPs are not practicing or religiously observant Christians. Despite the additional measures that we took to confirm our count of Muslim-origin MPs, we realize that we cannot entirely rule out the possibility of measurement error in the sense that the Muslim names in some countries may have been easier to identify.

We excluded countries where the share of Muslim population was lower than the share of population represented by a single member of parliament in the legislature at the time of the election. We find such a restriction both empirically sound and theoretically consistent with the expectations of descriptive representation, as it implies that the demographic breakdown of the legislature should mirror the demographic breakdown of the general population as closely as possible. From a practical standpoint, the absence of such a threshold would have led to a sample that would include a large number of theoretically uninteresting negative observations, where there are no Muslim-origin MPs expected to be elected and none is indeed elected.

Variables

Number of “Missing” Muslim-Origin MPs

The number of “missing” Muslim-origin MPs is the dependent variable of our research.Footnote 11 It indicates the difference between the actual number of Muslim-origin MPs in the legislature and the expected number of Muslim-origin MPs based on the share of Muslims in the general population of that country.Footnote 12 Since the number of MPs cannot be a fraction, the expected number of Muslim-origin MPs for individual elections is calculated as the integer part of the value obtained by multiplying the number of MPs in the national legislature by the share of Muslims in the population. Our empirical puzzle reflects the cross-national variation in descriptive underrepresentation, which is the prevailing norm in our data set. Besides, taking into account assumptions behind the concept of descriptive representation, the phenomenon of descriptive overrepresentation of certain ethnoreligious minorities in national legislatures might be associated with causal factors that are distinct from the ones affecting the levels of descriptive representation up to the point of parity. For example, electoral designs with more proportionate outcomes should, in principle, be negatively associated with political overrepresentation. Consequently, observations with negative difference, reflecting descriptive overrepresentation, are coded as having zero missing MPs.

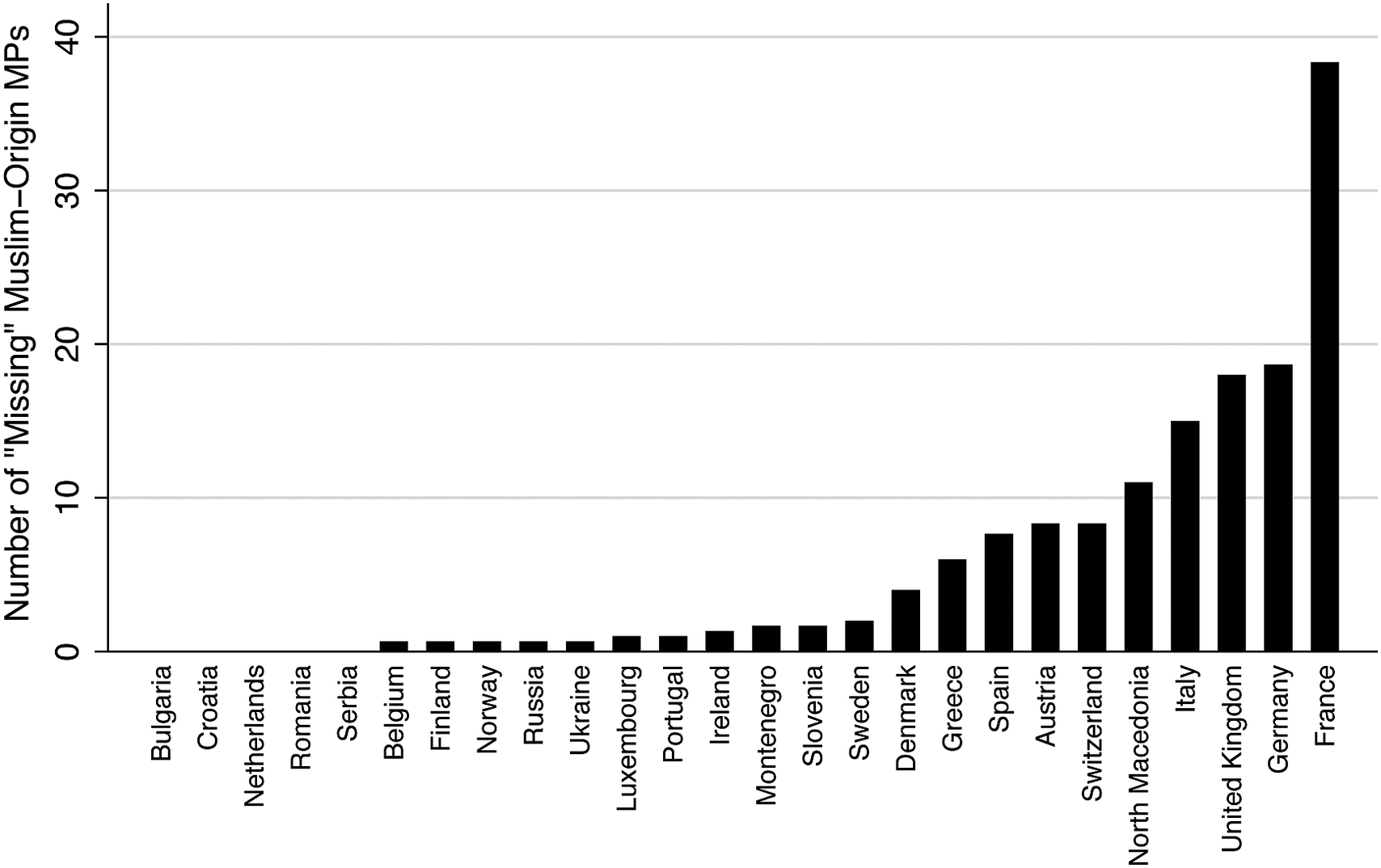

Figure 1 summarizes cross-national differences in the number of Muslim-origin MPs who were expected to have been in the legislature based on the share of Muslims in the general population (ARDA 2015) but were not there. Countries with the largest average number of such missing MPs are France (38.67), Germany (18.66), the United Kingdom (18), Italy (15), and North Macedonia (11). In contrast, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Netherlands, Romania, and Serbia have had no missing MPs for all observations in our sample, whereas Belgium, Finland, Montenegro, Norway, Russia, and Ukraine have had fewer than one missing Muslim-origin MP on average. As for the regional differences, on average 1.7 Muslim-origin MPs are missing from the legislatures of Eastern European countriesFootnote 13 and 7.8 MPs are missing in Western European countries. There also exists a regional difference within Western Europe. Nordic countriesFootnote 14 on average have 1.8 missing Muslim-origin MPs, whereas on average 9.6 Muslim-origin MPs are missing from national legislatures in the rest of Western Europe.

Figure 1 Average number of “missing” Muslim-origin MPs by country

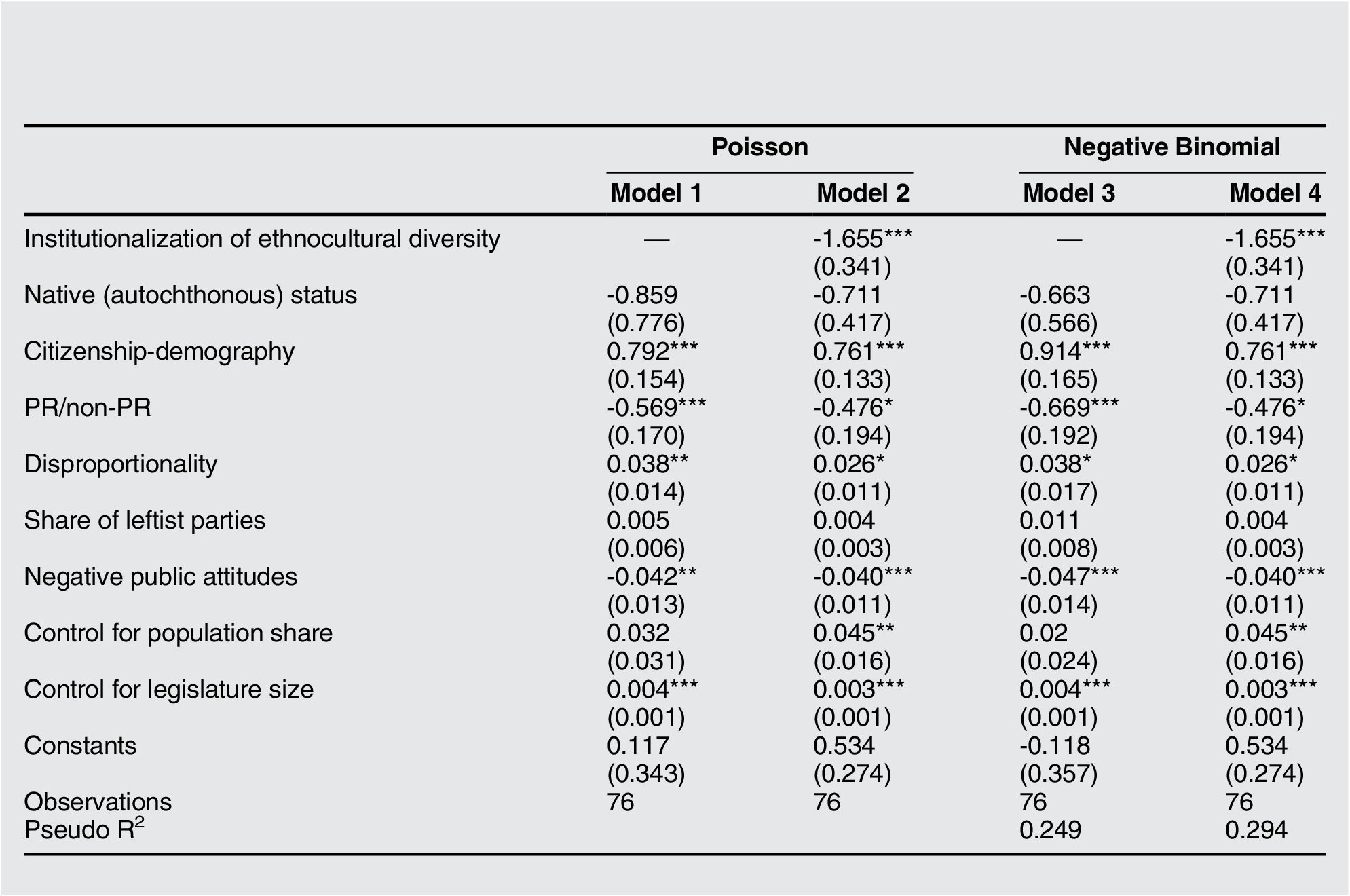

The dependent variable is a count (non-negative integer) variable, which varies between 0 and 42 and has a skewed distribution, which makes count models adequate for such data structure. The data shows signs of overdispersion (the variance of the dependent variable exceeding the mean) which we seek to alleviate by clustering standard errors. Besides adjusting standard errors in Poisson regression models, opting for a negative binomial regression model may provide a better model fit in such cases (Hilbe Reference Hilbe2014; Cameron and Trivedi Reference Cameron and Trivedi2013). We tested our data with the help of both Poisson and negative binomial regression models and arrived at identical results in terms of statistical significance and coefficients of the variables for the full models (table 1, models 2 and 4).

Table 1 Institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity and descriptive underrepresentation of Muslims in European legislatures

Note: Standard errors clustered by country are in parentheses; * p<.05, ** p <.01, *** p<.001.

Institutionalization of Ethnocultural Diversity

There are no cross-national quantitative measurements of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity that cover all countries in our data set and could be utilized for testing our hypothesis.Footnote 15 Therefore, in order to test our argument empirically, we have developed an original measurement of how weakly or strongly ethnocultural diversity is institutionalized based on an already existing global study of ethnic policies—an index that takes into account the presence or absence of particular policies such as multiple official languages, multiple ethnic categories in the constitution, ethnic territorial autonomy, ethnic minority status, ethnic categories in the census, ethnic affirmative action policies, and ethnic categorization of individuals in personal identification documents. Policies included in this measurement should be regarded as indicators of the overall level of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity, rather than a collection of independent variables, since none of them, taken individually, is expected to have a direct causal relationship with the levels of descriptive representation of European Muslims. The measurement is not based on value judgments but is restricted to formally codified elements alone, whose presence is validated by multiple experts, which together minimizes subjectivity in measurement. We utilize the “Regimes of Ethnicity” (Aktürk Reference Aktürk2015) survey data for the measurement of the institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity.Footnote 16

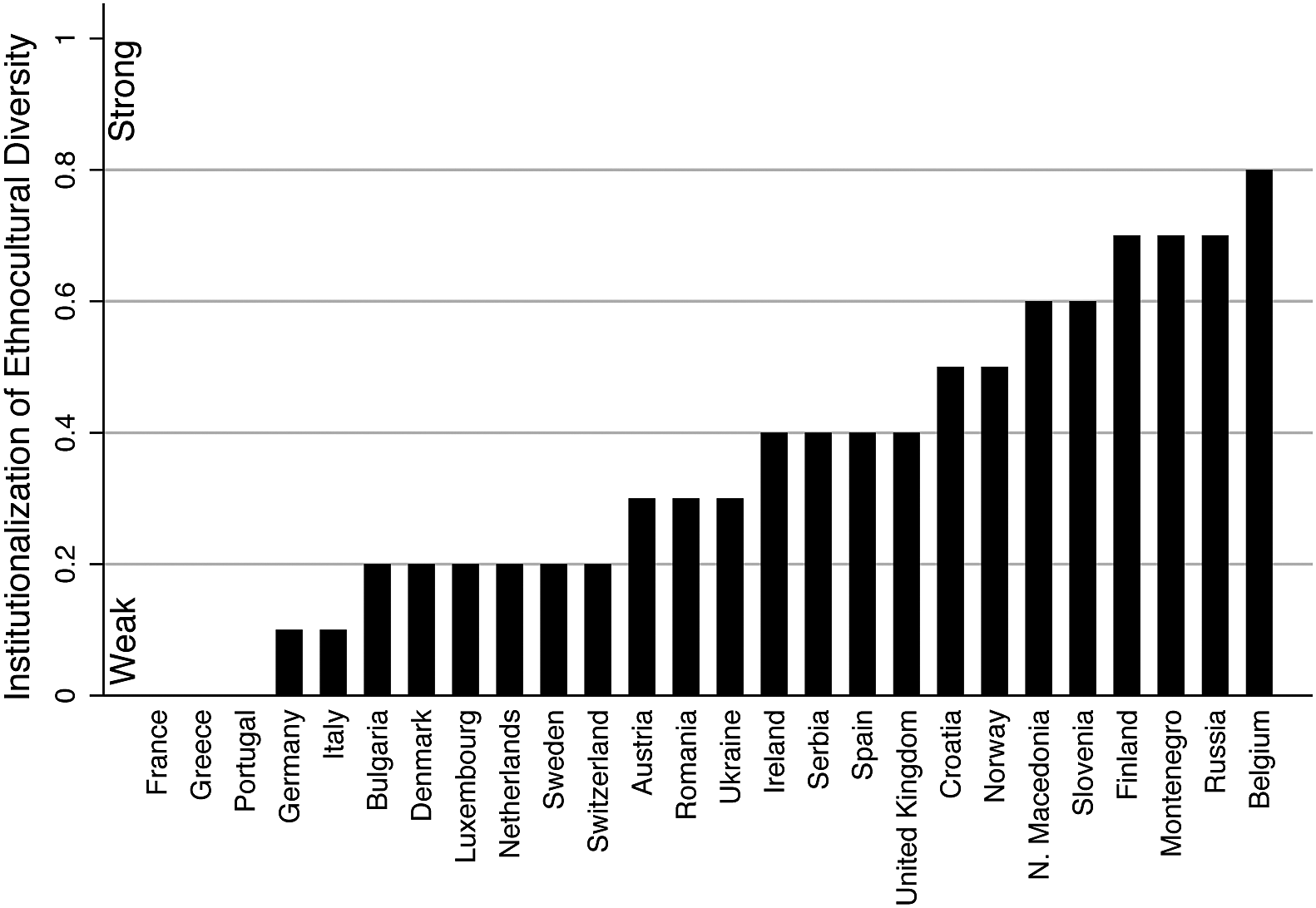

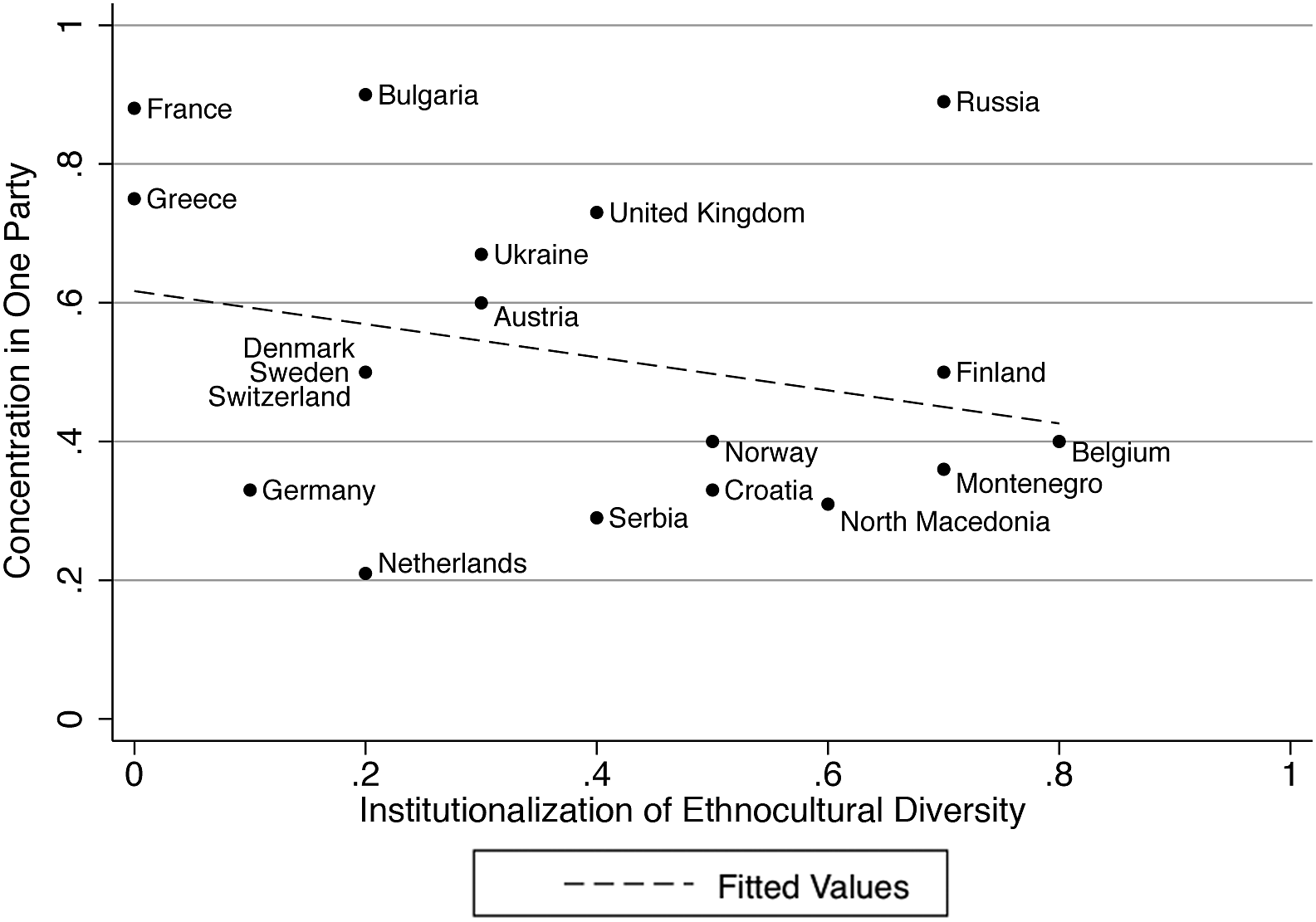

The values of the index that measures institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity in our sample (figure 2) vary between 0 (France, Greece, and Portugal) and 0.8 (Belgium). The index negatively correlates with the number of missing Muslim-origin MPs (correlation coefficient -0.39). Coincidence of the index values and variation in Muslim minority representation is also present at the regional level: Eastern Europe has an average value of 0.48, whereas Nordic countries have 0.4 and the rest of Western Europe has an average value of 0.24. Consequently, a working hypothesis based on our argument is as follows:

Stronger institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity will be negatively associated with the levels of descriptive underrepresentation of European Muslims, measured as the number of missing Muslim-origin MPs.

Figure 2 Institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity by country

Other Variables and Controls

Native or immigrant origin.

We utilize a binary measurement that differentiates between the countries in our sample that have or lack native (autochthonous) Muslim communities. We classify countries as having a native (autochthonous) Muslim minority if they had a Muslim minority in their modern day territory at the time of the state’s independence (or a functionally equivalent date) that was at least as large as the population share represented by a single MP, which is the same quantitative cut-off point that we used in selecting observations for our sample. As a result, we code all Eastern European countries, with the exception of Croatia and Slovenia, and with the addition of Greece, as having native (autochthonous) Muslims, which make up approximately 30% of observations in our sample.

Effects of migration and citizenship acquisition.

We do not use the naturalization rates as the proxy measurement for access to citizenship, since the data on naturalization rates is not available for all the countries in our sample. Available country-level data also contains gaps for particular years. Instead, we create a composite equivalent measurement (Citizenship-Demography) of this effect. We approximate citizenship acquisition through the number of years of legal residency in the country that is necessary to qualify for citizenship through naturalization,Footnote 17 normalized between 0 and 1, where 0 corresponds to no residency requirement and 1 corresponds to the largest number of years of legal residency in our sample. However, we expect the depressing effect of longer residency requirement to be more or less pronounced depending on the larger or smaller number of immigrants arriving, respectively. Therefore, we also account for the disproportionate growth of the local Muslim minority in years preceding any election included in our data set. We calculate it as the positive difference between the current share of Muslims in population and the share of Muslims lagged by twenty years. We multiply the two components to obtain our measurement. As the result, observations in which the share of Muslims has not increased over twenty years have the value of 0 regardless of residency requirements, and observations in which the share of Muslims has increased the most and the residency requirement is the longest have the highest values.

We assume that in the absolute majority of cases, migration remains the main contributor to the disproportionate growth of Muslim minorities in European countries. We have chosen a twenty-year period because it constitutes a time span that is sufficiently long for the naturalization as well as linguistic and socioeconomic integration of the members of immigrant minorities, and for building up a political career by those who choose to pursue such careers. However, accounting for disproportionate growth can also capture the additional effect of higher birth rates among some Muslim minority groups, which result in higher shares of children and adolescents and lower shares of cohorts eligible to vote or run in elections.

Electoral system.

We include both the binary coded distinction between PR and non-PR electoral systems and the continuous variable that measures the disproportionality of electoral outcomes through the least squares index in our empirical analysis. The least squares index (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2019) measures the level of disproportionality of electoral outcomes between the vote distribution and the seat distribution. The least squares index is an indirect measurement of the variation of electoral designs, since it is calculated based on the outcomes of particular elections and it slightly varies across electoral cycles in a single polity; but it strongly correlates with cross-national differences in electoral institutional arrangements. The index is the lowest in countries that have electoral systems based on proportional representation with larger districts and lower electoral thresholds.

Party ideology.

In order to test the presence or absence of an association between the levels of descriptive representation of Muslims and ideologically leftist parties, we have calculated the share of ideologically leftist and left-of-center parties in national legislatures in our sample.Footnote 18 As a rule, we classified communist, socialist, “green," social democratic, and labor parties as leftist and left-of-center parties. We crosschecked our classification based on membership in European party alliances, as listed on the European Parliament’s official website (2019).

Public attitudes.

We utilize the European Value Survey country-level data about prevailing attitudes toward Muslims (EVS 2015). We chose to operationalize unfavorable public attitudes as listing Muslims among undesired neighbors. We find this operationalization to be more suitable for our purpose than listing Muslims among undesired family members. The latter operationalization is too restrictive, since it pertains to the private sphere of family relations rather than to the public sphere of national politics. In other words, it is perfectly conceivable that people who would not want to see Muslims as part of their family would nevertheless be willing to vote for parties that nominate Muslim-origin MPs or for individual Muslim-origin candidates. It is much less conceivable that people who do not want to see Muslims among their neighbors would do so.

Controls for population share and legislature size.

Countries in our sample vary greatly with regards to the share of Muslims in their population (with minimum being 0.32% in Romania and maximum being 37.19% in North Macedonia) and the size of their national legislatures (with minimum being 60 seats in Luxembourg and maximum being 709 seats in Germany in 2017). We control for both of them, because it is mathematically more likely to have more MPs missing if more MPs are projected to be in the legislature in the first place.

Results

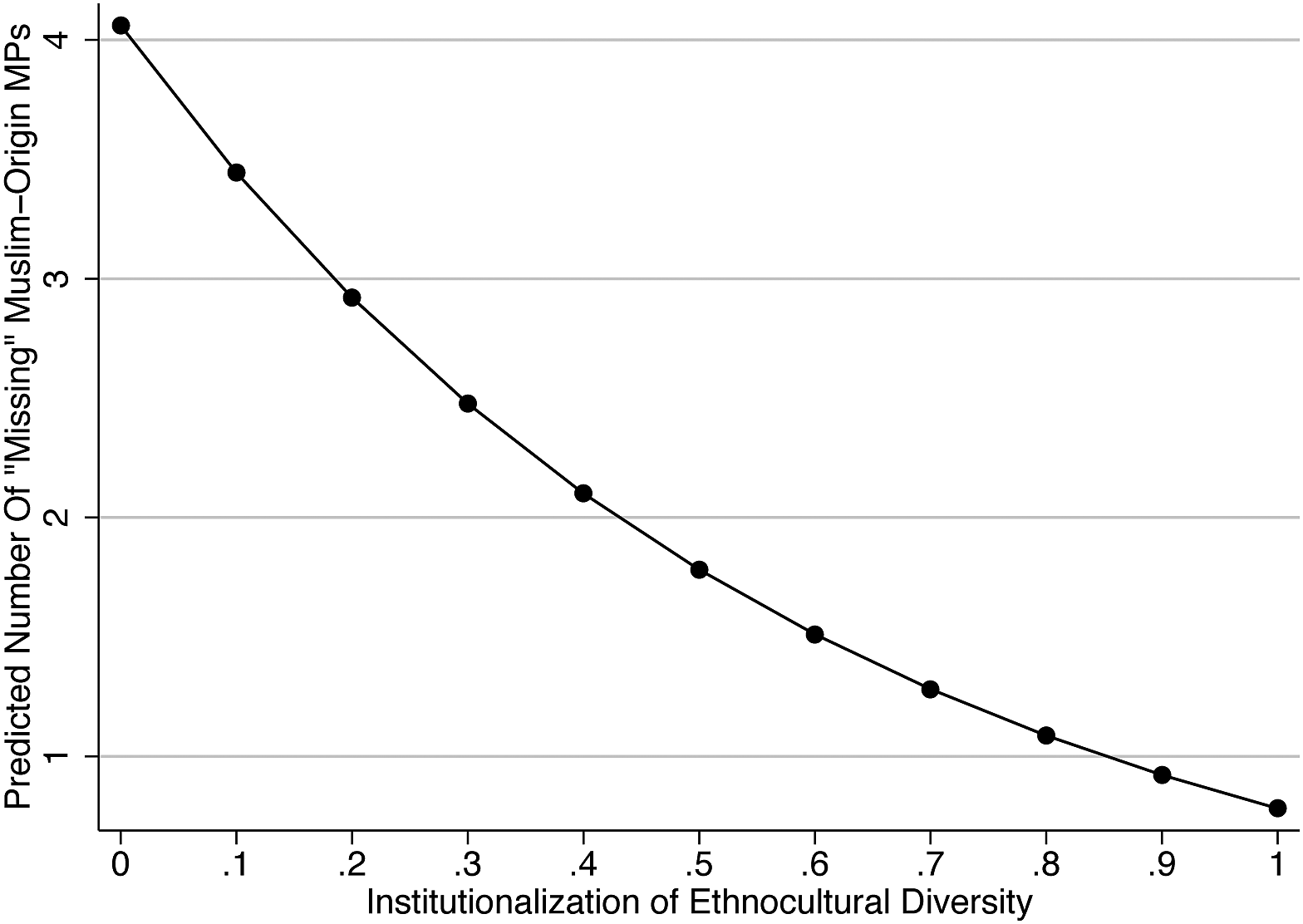

Table 1 presents results for the effect that institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity has on the number of missing Muslim-origin MPs, or MPs that are absent but predicted to be in the legislature based on the share of Muslims in the population. The results indicate that institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity has a statistically significant effect on the number of missing MPs in the theoretically anticipated direction. In other words, more strongly institutionalized ethnocultural diversity is associated with lower levels of descriptive underrepresentation of Muslim minorities in European legislatures. In more concrete terms, the association can be represented as follows (figure 3): if all other variables in the model are taken at their means, an increase in institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity from 0 to 0.4 corresponds to roughly two fewer Muslim-origin MPs that are missing from the national legislature, and an increase from 0.4 to 0.8 corresponds to an additional one fewer missing Muslim-origin MP.

Figure 3 Predicted number of “missing” Muslim-origin MPs

As anticipated, more rapid demographic changes, mediated by citizenship acquisition, which in our analysis capture the impact of migration and naturalization, are associated with higher levels of descriptive underrepresentation of local Muslim minorities. Likewise, electoral systems with proportional representation are associated with lower levels of underrepresentation whereas electoral systems that produce more disproportionate outcomes are associated with higher underrepresentation. More prevalent negative attitudes toward Muslims are associated with lower levels of descriptive underrepresentation, which can be interpreted as evidence for more intolerant social environments being conducive to higher levels of political mobilization and representation of minorities.

The dominance of ideologically leftist parties does not seem to be a statistically significant factor in explaining cross-national variation in the levels of descriptive representation of European Muslims in our sample. Likewise, there also seems to be no separate effect of native (autochthonous) status on the levels of descriptive representation of Muslim minorities. The lack of such an association supports our concerns regarding the strength of the often taken for granted connection between native (autochthonous) status and the levels of descriptive political representation of minorities.

Apart from correlations and cross-national inferential statistical models that test the relationship between institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity and Muslim minority representation, how could one observe the effects of the mechanisms that lead to higher political representation of Muslims, such as the willingness to nominate Muslim candidates by party elites across the political spectrum in a specific country? The distribution of Muslim-origin MPs across many political parties, as opposed to being concentrated in or captured by one or very few parties, could be an indication of multiple party leaders’ willingness to nominate Muslims. For countries with two or more Muslim-origin MPs, the relationship between the index and the concentration of Muslim-origin MPs in one partyFootnote 19 for the 2017–2018 data collection cycle is summarized in figure 4. The relationship is as we predicted, namely, higher levels of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity correlate with the existence of Muslim MPs from a larger number of parties.

Figure 4 Concentration of Muslim-origin MPs in one party

Congruence Testing

“Causal mechanisms, cross-case analyses, and case studies form the research triad” (Goertz Reference Goertz2017, 1), and we seek to follow a multimethod research approach to address our empirical puzzle. Therefore, we seek to support our cross-national inferential statistical findings regarding the effect of institutionalized ethnocultural diversity through congruence testing in four necessarily brief case studies.Footnote 20 First, we review Belgium and France as the “typical cases” of strongly and weakly institutionalized ethnocultural diversity that coincide with very high and very low levels of descriptive representation of local Muslims, respectively. Then we discuss the deviant cases of Bulgaria and the Netherlands, in which high levels of descriptive representation of local Muslims coincide with low levels of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity, but their deviance is explained through other factors identified in our statistical findings, namely, the positive effects of a proportional electoral system in the case of the Netherlands, and the effect of the disproportionate demographic change in the case of Bulgaria.

Belgium

Belgium has the highest institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity score in our sample (0.8), and it is one of the two countries in Western Europe where the Muslim minority has become represented beyond the level of parity. Even in electoral cycles earlier than the ones that we examined in our study, Belgium was already identified as “the only Western country where the proportion of Muslim parliamentarians exceeds the proportion of Muslims in the population” (Sinno Reference Sinno2009, 76). The coincidence of the highest institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity and consistently high Muslim representation in Belgium provides support for our argument, especially against the background of cross-national inferential statistical findings in the same direction. There are also case-specific qualitative observations that strengthen our inferences.

First, the pattern of Muslim-origin MPs’ distribution in the Belgian parliament across different political parties strongly supports our inference that a high level of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity encourages party gatekeepers across the political spectrum to nominate Muslim MPs. Muslim-origin MPs are not concentrated or segregated in a single party but distributed across five main parties; Muslim-origin MPs are not only found in socialist or center-left parties but can also be found in center-right parties; and Muslim-origin MPs are found not only in Francophone/Walloon or in Flemish parties but in both. More specifically, in the 2014 legislative term, there were six Muslim-origin MPs from the two largest center-left/socialist parties (PS and SP.A), three Muslim-origin MPs from two center-right (CD&V) and nationalist right wing (N-VA) parties, and one Muslim-origin MP from the ecological Green (Ecolo/Groen) party. Likewise, four Muslim-origin MPs belonged to Francophone/Walloon parties (PS), whereas five Muslim-origin MPs belonged to Flemish parties (SP.A, N-VA, CD&V), and one Muslim-origin MP belonged to a party that combines the Francophone and Flemish ethnolinguistic groups (Ecolo-Groen). These three forms of diversification of Muslim minority representation in the Belgian parliament (partisan, ideological, and ethnolinguistic) are indicative of widespread acceptance by almost all the main Belgian political parties’ elites (selectorates or “gatekeepers”) that Muslim candidates can, and often should, be nominated for electable positions in their party lists.

Second, one can also observe that Muslim candidates who are vocal about Islamic identity, including those exhibiting conspicuous indicators of religiosity, also succeeded in running for and getting elected to the Belgian parliaments, as we hypothesized in relating higher institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity to higher Muslim minority representation. This is an important distinction, because in most European countries where ethnocultural diversity is weakly institutionalized, such as France, only the most secularized segments of the Muslim minority successfully seek political representation. This would contribute to the underrepresentation of more religious segments of local Muslims, which may even constitute the majority of the whole group in some contexts. In Belgium, Muslim candidates who are vocal about Islamic identity run and sometimes win elections for a seat in the parliament, both at federal and regional levels. Emir Kır has been one of the most successful Muslim-origin Belgian politicians elected to different positions over the years including being a minister in a cabinet, and he is often spotted visiting mosques, on and off the campaign trail, and according to news reports, his supporters even referred to seeing him praying at their mosque (Alan Reference Alan2020). Beyond his personal connection to the mosques or religiosity, he has been politically outspoken in defense of Muslims attending the mosques, alleging that the Belgian federal government is profiling/monitoring the attendees (Yıldırımer Reference Yıldırımer2017). Somewhat similarly, Yüksel Veli (CD&V) campaigned in fundraising events for mosques (Gündem 2019). Furthermore, Belgium is also unique as the only European country that had a Muslim woman wearing an Islamic headscarf, Mahinur Özdemir, elected as a member of the parliament in the Brussels region, albeit not the federal but the regional parliament. These few examples are all the more remarkable because such public behavior among Muslim-origin MPs in most European countries is extremely rare, with the notable exception of the United Kingdom, which also has a moderate level of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity, thus conforming to the pattern we hypothesized. For example, praying at or campaigning in support of mosques, or wearing an Islamic headscarf, is unprecedented for any current or former Muslim-origin MPs in the French, Danish, and German (federal or regional) parliaments, which are countries that have low levels of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity. In short, our qualitative observations in the case of Belgium also support our expectation that higher levels of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity may be motivating and enabling more Muslim politicians, specifically those vocal about Islamic identity, who are conspicuous for their absence in many European parliaments, to successfully gain representation as MPs.

France

In France, very few Muslim-origin candidates are nominated for the national legislature by almost exclusively left-wing parties, and very few Muslim-origin candidates are elected as MPs (e.g., there was not a single Muslim-origin MP from mainland France in 2010), and in another stark contrast to Belgium, the few elected Muslim-origin MPs are overwhelmingly if not exclusively, from leftist parties (in the 2012–2017 legislative cycle, all four Muslim-origin MPs were from the Socialist Party). Not only that they are very few in number, but it is also widely recognized that the French Muslim MPs do not resemble the Muslim minority in their religious profile. While “70% of French Muslims of both sexes and across the age spread claim to fast for the entire month [of Ramadan]” and “39% of Muslims in France adhere to the strict regimen of five prayer interludes each day” and the Islamic headscarf “is worn by nearly one-third of religious Muslim women in France” according to respectable public opinion surveys (Adida, Laitin and Valfort Reference Adida, Laitin and Valfort2016, 82-84), not a single one of the Muslim-origin French MPs in our study (refer to online appendix 1) is ever reported to fast during Ramadan, wear a headscarf, or participate in weekly Friday prayers, let alone perform daily prayers. In short, we have no French Muslim equivalent of the successfully elected Belgian Muslim-origin MPs such as Emir Kır, Mahinur Özdemir, and Veli Yüksel, reviewed in the previous section.

It is also recognized that not only Muslims, but other minorities are also considerably underrepresented in France (Brouard and Tiberj Reference Brouard, Tiberj, Bird, Saalfeld and Wüst2011, 165; Maxwell Reference Maxwell2012, 106), once again confirming our argument that the monocultural, monolingual and unitary conception of the French nation that actively combats what is derisively called as “communitarianism” depresses the nomination/selection and election of minorities in general, not just Muslims. “Addressing a meeting of Prefects on 7 December 2004, Jean-Pierre Raffarin, Chirac’s Prime Minister, cut to the quick: ‘La Republique rassemble; le communautarisme divise’—The Republic brings us together; communitarianism divides” (Saunders Reference Saunders, Levey and Modood2009, 58). In reaction to the assimilationist political atmosphere that limited opportunities for minority representation, some French Muslims launched their own “Muslim” political parties, but all such attempts failed. For example, the Democratic Union of French Muslims (UDMF), probably the most prominent example of such a Muslim party, could not even get a single one of its candidates to the second round of the 2017 parliamentary election in any electoral district throughout France, let alone getting elected to the national parliament. Even in the districts of mainland France where it had its best results, UDMF’s vote hovered around 3%, and even the most successful candidates of the UDMF could not make it to the top five in the first round in any district.Footnote 21 Not a single Muslim MP has ever been elected to the national parliament from mainland France as an independent candidate or from one of the de facto Muslim parties.Footnote 22

In another stark demonstration of our argument, political parties associated with the major autochthonous/historical ethnolinguistic minorities of mainland France, such as the Breton Democratic Union (UDB) and the Occitan Party, have been rather unsuccessful if not altogether marginal in terms of their electoral performance. For example, Paul Molac has been hailed as the first Breton autonomist deputy ever elected to the French national parliament in 2012 and struggled for the recognition of Breton ethnolinguistic identity (Equy Reference Equy2018). It is not possible to obtain reliable figures on the number of Breton members who have been elected to the French national parliament past and present, in great part due to the very low level of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity in France. However, the singular exception of Molac’s recent election as the first Breton autonomist demonstrates the relatively low level of autochthonous ethnolinguistic minority representation in France, as the secondary literature on this topic also suggests (Brouard and Tiberj Reference Brouard, Tiberj, Bird, Saalfeld and Wüst2011, 165).

Netherlands

On average, there are four more Muslim MPs in the Dutch national parliament, Tweede Kamer, than a proportional representation of the Netherlands’ Muslim minorities would suggest. What might be the most relevant contributing factor that explains such high levels of Muslim minority representation in the Dutch national legislatures? We suggest that the Dutch electoral system might be in great part responsible for this outcome.

The Netherlands is located at the extreme end of the spectrum of proportionality of electoral systems with the average least squares index score of 0.92, reflecting its PR electoral formula with a single nation-wide district and absence of thresholds. These features of the Dutch electoral system have favored the Muslim minority’s proportionate representation and even overrepresentation throughout multiple legislative cycles. In the Netherlands, not only that half a dozen parties in the parliament have Muslim-origin MPs, but also a de facto Muslim party, DENK, gained representation in the parliament with three MPs. In the 2017 general election, fourteen Muslim-origin MPs were elected to the Dutch national parliament and their party affiliations were as follows: 3 DENK, 3 VVD, 2 D66, 2 GL, 2 SP, 1 CDA, and 1 PvdA. When Tunahan Kuzu and Selçuk Öztürk, two Muslim-origin members of the PvdA (Labor Party), criticized their own party’s plan to monitor religious organizations with Turkish origins in 2014, they were asked to apologize by the party leadership. When they refused to do so, they were expelled from the PvdA. In many other Western European countries, such an expulsion would have been the end of these MPs’ political careers, but in great part due to the Dutch electoral system, Kuzu and Öztürk were able to establish a successful new party, DENK. Kuzu and Öztürk, along with Farid Azarkan, were reelected as MPs from DENK in the next election that followed their expulsion from the PvdA, having received just 2.1% of the national vote.

Bulgaria

Bulgaria is an Eastern European country that has a low level of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity. At the same time, it has the highest level of descriptive political representation of local Muslims among twenty-six countries in our data set. On average, Muslims are overrepresented by eight additional MPs in the Bulgarian parliament. We suggest that rapid demographic changes might be responsible for current overrepresentation, because the relative share of the Muslim minority in Bulgaria’s population declined by 42% over the last twenty years. By a very sizeable margin, this decline is also the largest among the three countries in our data set where such a decline took place (two others being Serbia and Montenegro).

“Rearview mirror” is an appropriate metaphor to capture the temporal dynamics of Muslim minority representation, because the relative size of the Muslim population twenty years ago may be a more relevant demographic reference point for present-day electoral processes if there are disproportionate changes (positive or negative) in the minority’s share in the general population. An earlier demographic cohort is relevant for several reasons. First, it takes up to two decades for the youngest (infant) members of the minority to reach voting age. Second, it takes time for the politically ambitious members of the minority to gain experience, build networks, lobby for nomination, and have a reasonable chance of getting elected. Third, political parties, often led by members of the non-Muslim majority, likewise may be nominating MPs based on their sense of the size of the minority electorates without considering the recent growth or decline in the minority population, hence imprinting their candidate lists with the “rearview mirror” image of the electorate as it existed in the past. Fourth, “path dependence” in political processes (Pierson Reference Pierson2004) may also influence professional politicians of minority backgrounds, such that once elected, their MP or candidate status may become resilient in the face of changing demographics.

Arguably, this is what we observe in the significant overrepresentation of the Muslim minority in the Bulgarian legislature. Even as the share of the Muslim minority declined precipitously due to a variety of factors including mass emigration (especially to Turkey), seasoned Bulgarian politicians of Muslim origin, who almost entirely monopolize the third largest party in Bulgarian politics, Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS), continued to be nominated and elected as MPs, thus resulting in significant overrepresentation of the minority population over time (Aktürk and Lika Reference Aktürk and Lika2020).

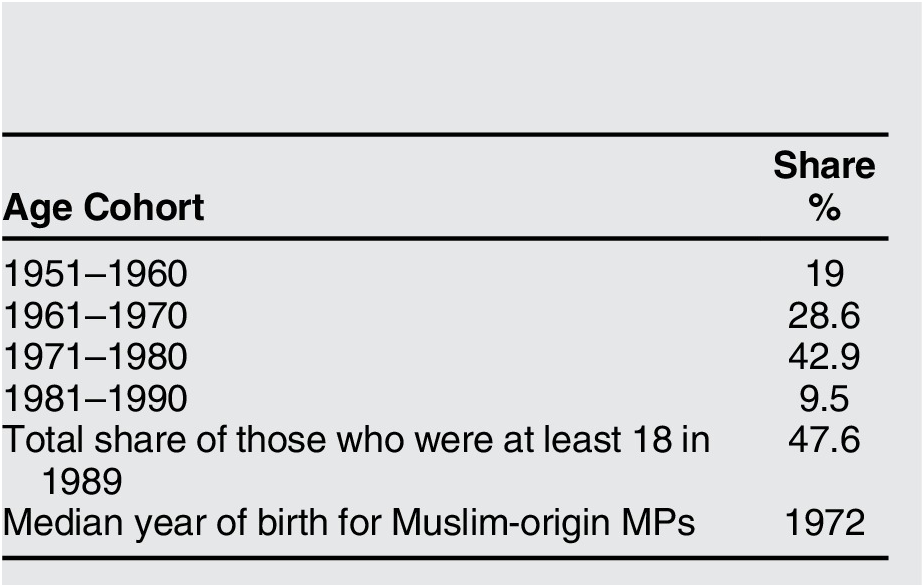

Table 2 reflects Muslim-origin MPs elected to the Bulgarian parliament in 2017, split by age cohorts. Almost half of the deputies were at least eighteen already in 1989, reflecting relatively older demographics, which supports our argument that the “rearview” nature of political representation, combined with dramatic demographic decline, accounts for the current descriptive overrepresentation. In a counterfactual thought experiment (Tetlock and Belkin Reference Tetlock and Belkin1996), we project that if the share of Muslim population had remained constant in the past twenty years, six Muslim-origin MPs would be missing in the legislature, corresponding to notable underrepresentation.

Table 2 Muslim-origin MPs in Bulgaria by age

Other Relevant Factors and Limitations of Findings

We do not directly test the validity of the argument that ethnically specific quotas have a positive effect on descriptive representation (Htun Reference Htun2004; Jensenius Reference Jensenius2017). Ethnically specific quotas are already included as part of our operationalization and measurement of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity under the category of “ethnically specific affirmative action.” Four countries in our sample implement arrangements, such as lower electoral thresholds for minority parties (Serbia, Montenegro) and guaranteed seats for national minorities (Romania, Croatia), which are functionally similar to ethnically specific quotas, and from which traditionally Muslim minorities may benefit even if they are not targeted directly.

We do not test the impact of territorial concentration of Muslim minorities on their descriptive political representation (Ruedin Reference Ruedin2013; Dancygier Reference Dancygier2017) due to reservations regarding the operationalization of this factor and the lack of reliable cross-national data. Countries in our sample that we identified as having native Muslim populations have regions in which traditionally Muslim minorities are geographically concentrated, and by including and testing the possible effect of being a native/autochthonous Muslim minority, we also control for the possibility that territorial concentration of historical (“native”) minorities might be resulting in higher Muslim minority representation in Eastern Europe. However, we are unable to measure reliably what percentage of the Muslim population actually resides in such areas as opposed to major urban centers and other regions. Besides, immigrant minorities also tend to concentrate in particular regions and urban centers rather than disperse evenly throughout the country. It is reasonable to assume that territorial concentration will most likely have some positive impact on descriptive representation, especially in those cases where local Muslim minorities constitute regional pluralities or majorities in areas that overlap with electoral districts. The autonomous republics of the Russian Federation with traditionally Muslim populations; Footnote 23 the Greek prefectures of Rhodope and Xanthi; the Bulgarian provinces of Kardzhali, Razgard, Shumen, and Targovishte; and municipalities in the Polog region of North MacedoniaFootnote 24 seem to meet this condition at least partially (Aktürk and Lika Reference Aktürk and Lika2020). Similarly, we are unable to test whether Muslim minorities are better represented in urban areas than in the countryside, based on Maxwell’s (Reference Maxwell2019) finding that cosmopolitan attitudes prevail in the former, whereas nationalist attitudes predominate in the latter.

Likewise, we are unable to test the proposition that higher turnout rates of Muslim minorities translate into higher levels of representation (Fieldhouse and Cutts Reference Fieldhouse and Cutts2008) due to the lack of corresponding cross-national empirical data. Nonetheless, country-specific qualitative assessments (Bird, Saalfeld, and Wüst Reference Bird, Saalfeld and Wüst2011) and figures for immigrants’ turnout rates in ten Western European polities (France, Belgium, UK, Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Germany, Austria, and Spain) are not congruent with our measurements of descriptive representation. Norway has significantly lower minority turnout rates than both France and Germany but has a much higher level of descriptive representation of its Muslim minority in the national legislature. Minorities in Sweden are also reported to have lower turnout rates than France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, and yet Sweden has higher levels of descriptive political representation of its Muslim minority than those three polities (Bird, Saalfeld, and Wüst Reference Bird, Saalfeld and Wüst2011).

Finally, the findings of our analysis are mostly limited to the effects of structural and institutional variables on the descriptive representation of European Muslims, who are treated as if they were a homogenous religious minority, despite their “myriad divisions” (Warner and Wenner Reference Warner and Wenner2006). We do not account for cross-national differences in the socioeconomic characteristics of local Muslim minorities that are generally associated with engagement in politics such as income and education levels (Klingemann Reference Klingemann2009, 85-89). We also leave out potentially relevant differences in ethnic and national backgroundsFootnote 25 of Muslim minorities in each country.

Conclusion

The advantages of descriptive representation include “adequate communication in contexts of mistrust” and “innovative thinking in contexts of uncrystallized, not fully articulated, interests,” both of which enhance substantive representation of the group’s interests, as well as “creating a social meaning of ‘ability to rule’,” and “increasing the polity’s de facto legitimacy” according to Jane Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge1999, 628). Anne Phillips (Reference Phillips1995, 6) argues that, compared to the representation of socioeconomic class differences, “once difference is conceived … in relation to those experiences and identities that may constitute different kinds of groups, it is far harder to meet demands for political inclusion without also including members of such groups.” In addition, Irene Bloemraad (Reference Bloemraad2013, 654-5) considers descriptive representation “a measure of the acceptance of a particular group by those in the majority” while having “real consequences for a minority group’s substantive representation … influencing the allocation of public resources such as public contracts or social benefits.” Moreover, minority “representatives may provide worse rhetorical representation, but nonetheless offer better policy representation than their [majority] counterparts,” as was recently demonstrated in the case of the first African American president of the United States (Haines, Mendelberg, and Butler Reference Haines, Mendelberg and Butler2019, 1039). Other benefits of higher descriptive representation include a positive change in the majority’s beliefs about a minority (Chauchard Reference Chauchard2014) and lower risk of civil conflict (Cederman, Weidmann, and Gledistch Reference Cederman, Weidmann and Gleditsch2011).

We present an original data set that includes Muslim minorities in both Western and Eastern European countries across three legislative cycles, hence avoiding generalizations based on a regionally specific subset of European countries or a single electoral cycle. Our empirical baseline also allows us to test hitherto taken for granted assumptions about the causal effect of Muslim minorities’ native/autochthonous versus immigrant/newcomer status on their political representation. The levels of descriptive political representation of Muslim minorities demonstrate a notable degree of variation across twenty-six European polities. On average, Muslim minorities have the highest levels of descriptive representation in Belgium, Bulgaria, the Netherlands, Romania, and Serbia, followed by Croatia, Russia, Finland, Montenegro, and Norway. In contrast, Muslim minorities in France, Switzerland, Spain, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Germany are the most underrepresented.

Theoretically, we provide a novel contribution by demonstrating that institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity may have a positive effect on Muslim minority representation. We argue that the official institutionalization of one kind of diversity (ethnic or linguistic) benefits the political representation of another kind of diversity (religious). This is also very much a story of unforeseen consequences, a kind of a spillover effect. For example, the eventually successful (sub-)nationalist struggle in Belgium to elevate Flemish to equal status with French throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, endowing Belgium with the highest level of institutionalization of ethnocultural diversity in our sample, originally had nothing to do with the prospective Muslim minority, which only arrived in Belgium in the late twentieth century. Recognition of any collectivity other than a single nation means recognition of multiple collectivities within the political community. The plurality of officially sanctioned collective identities, rather than the nature of the collective identities as such (e.g., ethnic, linguistic, racial), is the critical factor that legitimates and motivates the nomination and election of members of other collective identity groups, such as Muslim minorities, as members of the national parliaments across Europe. In contrast, polities that designate only one officially institutionalized collective identity, the single nation, and allow for the official expression of diverse ethnic, linguistic, and other cultural identities only by individual citizens, rather than as collectivities, tend to exhibit significant underrepresentation of their Muslim minorities in their national legislatures.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. Muslim-Origin MPs in 26 European Countries

Appendix 2. Measuring Cross-National Variation in Descriptive Representation of European Muslims

Appendix 3. Summary Statistics

Appendix 4. The Procedure for Measuring Institutionalization of Ethnocultural Diversity

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720001334.