Zootopia is a computer-animated Disney film about a rabbit police officer—Judy Hopps—and a fox con artist who partner to investigate a criminal conspiracy. Toward the end of the film, Officer Hopps needs to find the drop-off location for “night howler” flowers (a poisonous flower that has been weaponized to turn animals “feral”). She turns to an organized crime boss to extract information from a lackey of the antagonists. The crime boss’s polar bear enforcers hold the lackey over a hole in iced-over water, threatening to throw him in (and ostensibly kill him) if he doesn’t give up the location. “Ice him,” says the crime boss. The lackey quickly gives up the desired information and our heroes go on to (spoiler alert) save the day. In an animated film, this scene may seem like an innocuous plot device to move the story forward. Yet it also serves two other functions: it suggests that torture is an effective method of extracting information and it normalizes this violence for a young audience in a way that may prepare them for darker depictions of torture—often involving humans—as their media consumption evolves toward more adult-geared content.

Despite domestic and international prohibitions on torture dating back more than half a century, recent public opinion polls show that approximately half of adults in the United States think that torture can be acceptable in counterterrorism (Tyson Reference Tyson2017). Particularly since 9/11, we have seen a resurgence of debate over the use of torture where many politicians and members of the public assert that torture works to produce actionable intelligence (Murdie Reference Murdie2017). Yet many interrogation professionals disagree and maintain that torture is ineffective and often counterproductive (Fallon Reference Fallon2017; Lagouranis and Mikaelian Reference Lagouranis and Mikaelian2007). The disconnect between public and expert opinion on torture is especially troubling given that public support for human rights has consistently been one of the major bulwarks against violations. Democracies such as the United States generally have fewer human rights violations because voters punish leaders for violating democratic norms (Davenport Reference Davenport2007). Torture, though, appears to be an exception to this general principle, at least among voters in some democratic states such as the United States and India (Amnesty International 2014).

The vast majority of the U.S. public (thankfully) lacks direct, personal experience with torture. Rather, public exposure to torture is almost entirely limited to depictions in popular media, raising questions about how media affects voter opinions on torture policy. Recent experimental studies show that when people see torture as effective, they are both more supportive of the practice and more willing to sign a petition in support of torture (Kearns and Young 2018, Kearns and Young forthcoming). Yet as Bennett and Iyengar (Reference Bennett and Iyengar.2010) note, it is unclear whether entertainment media as a whole present a consistent message on political issues and—if the messages are scattered—then persuasion effects should be minimal. To date, most studies on torture in media have focused on specific shows or movies known to depict torture within a national security context such as 24 or Zero Dark Thirty and thus the extent of their external validity or generalizability is unknown. Without a systematic accounting of the portrayal of torture in popular media, it is impossible to ascertain whether media presents a clear message on torture or not.

We address this gap in the literature by systematically evaluating the prevalence and nature of torture in popular movies. Specifically, we watched and coded every instance of torture in the twenty top-grossing films (in terms of North American box-office receipts) each year over a ten-year period from 2008 to 2017. To be clear, we cannot say what influence these media depictions have on the public. Rather, our aim here is to describe and analyze how torture is characterized across popular media in a systematic way to ascertain whether messages are scattered, as Bennett and Iyengar (Reference Bennett and Iyengar.2010) contend, or more consistent. From this, we expect that movies generally show torture to be effective. Further, we expect movies will depict protagonist-perpetrated torture as more acceptable and necessary and antagonist-perpetrated torture as more harsh and unjustified.

Why Media Matter

Media play a critical role in framing the world around us, especially given its prominence in our lives: adults in the United States spend—on average—twenty-four hours of each week watching both news and entertainment television (Koblin Reference Koblin2016). Particularly when we lack direct personal experience with something, media representations are central to how we mentally construct the issue (Adoni and Mane Reference Adoni and Mane1984; Gerbner Reference Gerbner1998; McCombs Reference McCombs2003). Moreover, people view violent media in general as informative (Bartsch et al. Reference Bartsch, Mares, Scherr, Kloß, Keppeler and Posthumus2016) and inoffensive (Coyne et al. Reference Coyne, Callister, Gentile and Howard2016). When media portray an issue, it conveys to viewers that the topic is important and worthy of being shown (Bekkers et al. Reference Bekkers, Beunders, Edwards and Moody2011). Media coverage can influence policy preferences across a number of domains including the time it takes for FDA drug approval (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2002), public views of a social problem’s importance and how to address it (Strange and Leung Reference Strange and Leung1999), and responses to conflict and disasters (Gilboa Reference Gilboa2005). In the context of counterterrorism, images and video can be particularly effective at political persuasion. For example, Gadarian (Reference Gadarian2014) found that images of terrorist attacks in the news can enhance voters’ opinions of counterterrorism policy.

As Jones (2006, 365) noted, political communication studies long assumed that news was the “primary and proper sphere of political communication.” However, the distinction between news and entertainment is increasingly arbitrary and untenable as genres and sources blend. Delli Carpini and Williams (Reference Delli Carpini, Williams, Bennett and Entman2001) argued that the political relevance of media depends on its use in the public conversation, not necessarily its status as fact or fiction. Similarly, Curran (Reference Curran, Overholster and Jamieson2005a, Reference Curran, Curran and Gurevitch2005b) argued that entertainment media play a critical role in democratic processes by maintaining and regulating social norms as well as by facilitating debate on those norms. Prior (Reference Prior2007) articulates a theory of the “postbroadcast democracy,” wherein those disinterested in traditional news programming can now eschew that content in favor of entertainment media and other forms of gratification. Holbert, Garrett, and Gleason (2010, 19) argue that while “the primary intention of entertainment media may be to entertain … these non-news outlets can still generate a host of unintended political outcomes.”

Mutz and Nir (Reference Mutz and Nir2010) contend that entertainment media can have a persuasive effect on its audience. This audience, when compared to consumers of news media, is more likely to hold weak political views and be less resistant to this more subtle form of political persuasion. Research shows that both television and movies influence public views on a host of crime and justice issues (Callanan and Rosenberger Reference Callanan and Rosenberger2011; Donahue and Miller Reference Donahue and Miller.2006; Donovan and Klahm Reference Donovan and Klahm2015; Eschholz et al. Reference Escholtz, Blackwell, Gertz and Chiricos2002). For example, experimental work shows that fictional television can influence support for the death penalty (Slater, Rouner, and Long Reference Slater, Rouner and Long.2006) and perceptions of the criminal justice system more broadly (Mutz and Nir Reference Mutz and Nir2010). Experimental work using another entertainment genre—dystopian fiction—was shown to enhance subjects’ willingness to justify radical and violent forms of political action (Jones and Paris Reference Jones and Paris2018). Looking at the link between entertainment media and action, a longitudinal study found that youths who watched more violent media were more likely to later engage in violent and delinquent behavior (Hopf, Huber and Weiß Reference Hopf, Huber and Weiß2008).

Tenenboim-Weinblatt (Reference Tenenboim-Weinblatt2009) showed that political elites and commentators often use fictional media to justify real-life political positions, serving a function in political discourse similar to that of real-life individuals and events. Perhaps the clearest illustration of this dynamic regarding torture comes from the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia who used 24—a fictional entertainment show—as justification for torture in real-world counterterrorism. While Scalia disavowed torture as punishment, he was less absolutist on torture in interrogations, and reportedly said, “Is any jury going to convict Jack Bauer? I don’t think so” (Benen Reference Benen2014).

Justice Scalia was not the only prominent political figure to use 24 as a lens through which to analyze public policy. Former president Clinton, in a 2007 appearance on Meet the Press¸ speculated that real-life agents might decide on their own accord to use torture, and that this was preferable to torture being enshrined in public policy: “If you look at the show, every time they get the president to approve something, the president gets in trouble, the country gets in trouble. And when Bauer goes out there on his own and is prepared to live with the consequences, it always seems to work better” (New Republic 2007). Further, columnists in major newspapers regularly cited 24 in order to supplement their real-life political arguments about torture (Tenenboim-Weinblatt Reference Tenenboim-Weinblatt2009). Surprisingly, even Senator John McCain—who was tortured during the Vietnam War and remained a vocal opponent of torture throughout his life—was a fan of 24. Senator McCain appeared in an episode of 24 and later joked about torture on the show.Footnote 2 McCain’s actions suggest that he, like many Hollywood producers, viewed entertainment media as just that—entertainment.

Entertainment Media, Violence, and Public Opinion

Applying Giddens’ theory of structurations to media, Webster (Reference Webster2011) argues that agents consume media, structures are the media resources that provide content for agents, and the duality of media is the process through which agents and structures mutually construct society. Through duality, media both reflect and shape public desires to create a symbiotic relationship between audiences and the fictional storylines that resonate with them. As such, pop-culture media have the potential to convey information and to influence public attitudes, yet it is unclear whether these media are the cause or the effect of political views within society (Nexon and Neumann Reference Nexon and Neumann2006).

Crime dramas—a popular entertainment genre—illustrate the relationship between media and public opinion and policy. Crime and violence are frequently depicted in media despite their relative rarity in everyday life. In part, the prevalence of crime media results from high public demand for the content (VanArendonk Reference VanArendonk2019). Yet the proliferation of crime-related entertainment media may also help explain why the public views crime as increasing when—in fact—it has been declining over the past few decades (Gramlich Reference Gramlich2017).

The argument that media influence public opinion—and potentially policy—assumes that media present a coherent and consistent view on torture policy. While Mutz and Nir (Reference Mutz and Nir2010) found that the tone of a criminal justice-focused TV clip influenced views on policy, they note that the aggregate impact of such media on policy preferences is likely related to the net tone of these messages across media. As Bennett and Iyengar (2010, 36) point out, the political messaging in entertainment media tends to be scattered and inconsistent: models of political persuasion “generally assume repetition of clear messages, often through campaigns that reach people multiple times in contexts that tend to reinforce the credibility of the message.” They further contend that, on the whole, entertainment media are diverse and inconsistent in terms of political messaging, making it unlikely that it provides a persuasive effect on viewers. Yet the assumption about media’s inconsistent messaging remains relatively untested due to a dearth of systematic analyses of messages across entertainment media.

Entertainment Media and Torture

While U.S. public actors have committed torture in places like Abu Ghraib and the Guantanamo Bay detention camp, most adults in the United States have no direct personal experience with torture. Since the vast majority of the U.S. public lacks first-hand knowledge of torture, media may play a particularly strong role in framing public opinion on this subject—particularly if there is a clear and consistent message. Research suggests that media play a critical role in framing torture as a “necessary evil” to gather actionable intelligence in the name of national security (Flynn and Salek Reference Flynn and Fernandez Salek2012; Prince Reference Prince2009). To date, two studies have experimentally tested the influence of media depictions of torture on public attitudes and actions on torture policy. First, college students who were assigned to see a clip from 24 where torture works were both more supportive of the practice (beliefs) and more willing to sign a petition to Congress about torture (actions) (Kearns and Young Reference Kearns and Young2018). Second, the aforementioned study was replicated with an approximately representative sample of adults in the United States. Again, people who saw a clip from 24 where torture worked were more supportive of the practice. Further, to test whether people were primed on torture specifically or violence generally, some participants saw a clip of a fist fight and average support for torture in that condition decreased post-treatment (Kearns and Young forthcoming). Together, the limited experimental evidence suggests that media depictions of torture do influence views. Further, results suggest that there is something unique about media depictions of torture and their influence on public opinion of the practice relative to media depictions of crime or violence more broadly. Yet undergirding Bennet and Iyengar’s (Reference Bennett and Iyengar.2010) point on media messaging, previous studies of torture in media have almost exclusively focused on a handful of films and television shows that overtly display torture in a specific national security context. To that end, a systematic study of how torture is presented in media more generally provides a needed test of the external validity of previous experimental work.

Prior work tells us little about the consistent versus scattered nature of media messages on torture in general. There is, however, limited research on how torture is screened in particular genres or films. Movies help to create and perpetuate the myth and cultural language through which Americans see themselves and the country (Belton Reference Belton1994). As such, film depictions of torture degrade real violence, privilege white characters as the hero, and are rife with ethical issues (Goldberg Reference Goldberg and David Slocum2001). Through genres of horror and torture-porn films, both the perpetrators and victims of torture have historically been “othered” in some way that creates distance from the viewer (Middleton Reference Middleton2010). More recently, however, films acknowledge U.S. responsibility for torture in an attempt to redeem American identity, though film depictions of torture still privilege Western perspectives and suggest that torture is sometimes necessary to protect U.S. interests (Middleton Reference Middleton2010). Further, film can be a medium to present contentious policies such as torture to the audience (Westwell Reference Westwell2014) and to provide an avenue to argue for the ethics, value, and need for torture (Clucas Reference Clucas, Clucas, Johnstone and Baden-Baden2009).

Pop culture depictions of torture often rely on oversimplified notions of good versus evil (Wright Reference Wright2010) and portray torture with a sense of foreboding conveyed through the cinematography and the score (Middleton Reference Middleton2010). For example, focusing on The Bourne Ultimatum and 24, Brereton and Culloty (Reference Brereton and Culloty2012) describe both lead characters as traumatized protagonists who serve as surrogates for the American audience, combat internal enemies, and provide escapist entertainment. Similarly, drawing from Bordwell’s (Reference Bordwell1985) film analytic approach to examine Zero Dark Thirty, Schlag (Reference Schlag2019) describes the film’s protagonist as a traditional cowboy (or cowgirl in this case) who reluctantly embraces unsavoury means to accomplish her mission. In the film, torture scenes are shot in partial darkness with an up-close, handheld camera to give the viewer a sense of participation in the events. Further, depictions show divergence between two intelligence officers, one of whom is less brutal and intended to represent the audiences’ gaze. Throughout the film, torture is depicted as both common and exceptional where the perpetrators do not suffer any psychological or legal consequences for their actions (Schlag Reference Schlag2019).

Despite the clear depictions of torture, the word “torture” itself only appears in Zero Dark Thirty twice (Schlag Reference Schlag2019), which mirrors news media framing of Abu Ghraib (Bennett, Lawrence, and Livingston Reference Bennett, Lawrence and Livingston2006). Importantly, while the U.S. public is generally tolerant of torture in entertainment media, photographs of actual torture from Abu Ghraib were shocking and served as a “critical prism through which elite and popular views on U.S. foreign policy are refracted” (Andén-Papadopoulos Reference Andén-Papadopoulos2008, 24). The Abu Ghraib photos evoked images of lynching, genocide, and pornography (Carrabine Reference Carrabine2011; Sontag Reference Sontag2004) while suggesting that torture was used for fun (Sontag Reference Sontag2004).

Work on how torture is screened in some genres or films is interesting, though again this tells us relatively little about the overall presence of torture in the media that Americans consume. Even the most well-known and studied examples of torture in film remain unseen by the majority of the public. For all its fanfare, Zero Dark Thirty was only the thirty-second most popular film in its year of release (Box Office Mojo). Similarly, 24 never once cracked the top twenty in terms of Nielsen Ratings across its nine seasons, topping out as the twenty-second most-watched prime-time network show in its 2008–2009 season (Brooks Reference Brooks2018). When compared to top-grossing movies such as Zootopia or Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, the cultural impacts of 24 or Zero Dark Thirty are negligible, as a relatively small subset of the public has even seen them.

The extant focus on more overt examples of torture is a clear case of “selection on the dependent variable” in constructing the sampling frame (King, Keohane, and Verba Reference King, Keohane and Verba1994) and omitting all variation in the key outcome variable: whether media depicts torture or not. Without a systematic evaluation of the prevalence and nature of torture in media, we are unable to respond to Bennett and Iyengar’s (Reference Bennett and Iyengar.2010) critique. Indeed, other systematic evaluations of entertainment media related to crime and justice issues have found some consistency in messaging. For example, Cavender, Bond-Maupin, and Jurik (Reference Cavender, Bond-Maupin and Jurik1999) coded seven seasons of America’s Most Wanted and found that the show predominantly—and disproportionately to actual crime statistics—depicts young, white female victims and portrays them in perilous, subordinating roles where men speak for them. More recently, Nielsen, Patel, and Rosner (Reference Nielsen, Patel and Rosner2017) coded fourteen Disney films for themes of law and morality, which they found were often at odds with one another. If media indeed presents a scattered and inconsistent message regarding the efficacy and acceptability of torture, it likely has no effect on the viewing public. If, however, media systematically presents and reinforces the idea that torture can be an efficacious means to a desirable end, it may indeed shape political opinion.

Current Study

A key challenge we faced was to develop a working definition of torture that is rooted in conventional, real-world definitions but is flexible enough to apply to film contexts. We began with the definition of torture as spelled out in the UN Convention Against Torture and expanded it where needed to accommodate the alternate universes presented in popular films. A thorough discussion of this process is detailed in online appendix B. We eventually landed on the following working definition of a torture incident for the scope of this project:

A torture incident includes any act by which severe pain and suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a specific, unwilling anthropomorphized being who a) is not actively resisting or posing a direct, personal threat to the torturer and b) cannot voluntarily remove themselves from the situation in a reasonable manner. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in, or incidental to lawful or unlawful sanctions, murder, or other forms of killing. It does not include descriptions of off-screen torture incidents in which the results are not shown on-screen.

Beyond simply assessing the prevalence of torture in popular films, we also seek to assess the nature and context of media depictions of torture to evaluate how torture is portrayed. Should media portray torture as ineffective, brutal, and unjustified, we might expect that viewers would come away with a dismal view of the practice. Instead, we contend that popular media portrays torture in a sympathetic light; depicting it as an effective and justifiable technique used by even the most virtuous heroes. Specifically, we argue that media portrays torture as an effective strategy to obtain information or to coerce victims into action. Further, we expect that the way in which media portrays torture will depend on who is perpetrating it. Specifically, protagonists engage in more socially acceptable forms of torture whereas antagonists use torture in ways that are less justifiable. We elaborate on our specific hypotheses here.

Torture’s Efficacy

We consider torturers to have two possible goals, which are not mutually exclusive. Instrumental torture is intended to extract information from victims or coerce them into action, whereas punitive torture seeks to use torture as a method of punishment. Discussions about the efficacy of torture exclusively center around its instrumental form, since torture is obviously an effective form of punishment. Given that extant experimental research shows that people are more supportive of torture when they see it work (Kearns and Young 2018, Kearns and Young forthcoming), understanding the overall effectiveness of torture in media is crucial to understanding the net message across media. From this, we expect that:

H1: Instrumental torture is effective most of the time.

Who Tortures and the Acceptability of Torture

Social identity theory posits that people view members of their in-group—or people like themselves—more positively than members of an out-group—or people dissimilar to themselves (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986). In the context of torture, people tend to be more supportive of using torture against people of a different race (Miron, Branscombe, and Biernat Reference Miron, Branscombe and Biernat2010), nationality (Norris, Larsen, and Stastny Reference Norris, Larsen and Stastny2010; Tarrant et al. Reference Tarrant, Branscombe, Warner and Weston2012), or ideology (O’Brien and Ellsworth Reference O’Brien and Ellsworth2012). Films also exploit this in- and out-group dynamic to make audiences invest their emotional sentiments in the plotline; a successful protagonist is someone in whom we see a bit of ourselves, or at least a reaffirmation of the norms and values we hold dear (Snyder Reference Snyder2005). Should the protagonist engage in behavior that the audience considers unacceptable, the audience may begin to root against them and therefore find the protagonists’ eventual success unsatisfying.Footnote 3 Conversely, antagonists succeed to the degree that they engage in behavior that subverts and violates norms that the audience holds dear. In general, films provide us with narrative affirmations of our core values: Protagonists experience a challenge, but eventually succeed because of their adherence to (or discovery of) the core ideological values that matter to the audience. Antagonists challenge the protagonist, but eventually fail because of their rejection (or abandonment) of those very same core values. These films are thus satisfying to the audience because they reassure us that our values are correct, and that they will lead us to success.

For our purposes, we can use this dynamic to assess the forms of torture that films portray. Building from prior examinations of torture in select films (Middleton Reference Middleton2010), we expect that media depict torture differently based on which character(s) are involved. Protagonists—members of our in-group as viewers—should engage in more acceptable forms of torture than antagonists—members of our out-group. Acceptability of torture can be thought of in a few ways: the reason for its use, the outcome, and the target.

We first consider the reason for torture. Most public debates regarding torture as public policy tend to center on torture for instrumental reasons: perpetrators are forced to engage in torture as an unfortunate necessity in service to some larger goal such as obtaining information crucial to preventing either an imminent or a potential future terror attack (Gronke et al. Reference Gronke, Rejali, Drenguis, Hicks, Miller and Nakayama2010). By contrast, torture as punishment is generally proscribed, and receives specific legal prohibition in the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Though rarely addressed directly in public debate, we expect to see this discrepancy between the justifications for torture borne out in the actions taken by protagonists and antagonists. Protagonists should torture for more noble (instrumental) reasons when the situation demands this course of action. Antagonists, in contrast, should be less discriminating and torture sometimes for instrumental purposes but also for punitive reasons. Further, in the public narrative torture is often justified under the ticking time bomb scenario where only torture will prevent an imminent attack. Whereas antagonists might be likely to torture for any number of reasons, we contend that protagonists are more likely to torture because the situation “demands” it. Since both instrumental goals and threat mitigation provide more acceptable reasons for torture, we expect that protagonists will be more likely to use those. Specifically, from this we expect that:

H2a: Protagonists are more likely than antagonists to use torture for instrumental purposes.

H2b: Protagonists are less likely than antagonists to use torture for punitive purposes.

H3: Protagonists are more likely than antagonists to torture in response to a specific, existing threat.

Next, we consider differences in the efficacy of instrumental torture. A protagonist is someone we “identify with and want to root for” (Snyder Reference Snyder2005, 49). The protagonist’s journey to achieve their goals is not only a chronicle of struggle, but presents the theme of the movie itself: We root for them because their goals and techniques are virtuous, and it is because of that virtue that our heroes succeed (Snyder Reference Snyder2005). Accordingly, we expect to see this dynamic expressed with regards to torture: Given the superior approach and noble goals of protagonists, we expect that their attempts at instrumental torture will be more effective than those of antagonists. Specifically, we expect that:

H4: Protagonists are more likely than antagonists to be effective at torture.

Finally, we turn to the victims of torture. The majority of public opinion polling on torture seems to presume that all suspects (and potential victims) are a) culpable of some crime and b) are capable of whatever action(s) the torturers demand (Gronke et al. Reference Gronke, Rejali, Drenguis, Hicks, Miller and Nakayama2010). Whereas this assumption of guilt on the part of victims serves to ease objections to the perceived informational gains of torture, torturing innocents or those incapable of complying would reflect a violation of societal norms. Further, film narratives are a reflection of symbolic social order and gendered power relations where women are rarely depicted as the perpetrators of violence and representations of female victims tend to be depicted as both abnormal and sensational (Wolf Reference Wolf2013). From this, we expect that protagonists will rarely torture women, who may be perceived as more vulnerable than male victims. We expect to see this dynamic reflected in the protagonist/antagonist dichotomy: Antagonists will be more inclined to torture without discrimination, more often torturing victims incapable of complying as well as women. Specifically, we expect that:

H5: Protagonists are less likely than antagonists to torture women.

H6: Protagonists are less likely than antagonists to torture people who are incapable of complying.

Method

Data

The purpose of this study is to investigate the prevalence and character of torture in popular films. Since our focus is on popular media, our criteria for inclusion is based on box office receipts as reported by the website BoxOfficeMojo.com. Due to limitations on the researchers’ funds, time, and sanity, we restricted our sample to the twenty most popular films each year (in the North American market) from 2008 to 2017, giving us a sample of 200 total movies. Using average ticket prices and box office numbers, each film sold between 16,224,707 and 111,110,584 tickets in the North American market (M=30,478,129; Mdn=25,489,246; SD=15,017,302).

We coded torture at the incident-level. Some movies have no torture incidents, yet more than half (59.5%) of the movies in our sample contained at least one torture incident, and nearly one-third (30.5%) contained more than one. In total, we coded 284 torture incidents across the 200 movies in our sample.Footnote 4 A full list of the movies and the number of torture scenes in each is provided in online appendix A. The full dataset that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Coding Torture

In attempting to impose empirical rigor to the motion picture arts, we faced numerous conceptual hurdles prompting deep discussion and difficult choices. Movies take place in fantasy worlds that routinely bend physics and reality, and those worlds are often characterized by many forms of violence. As a consequence, formulating a strict definition of what is or is not a torture scene was a challenging and sometimes absurd process. Despite these challenges, we were able to create and impose a systematic process of inclusion that meets our purpose. Details of our coding criteria follow and we provide various examples from movies in our sample in online appendix B.

What Torture Is

We start with our working definition of a torture incident derived from the UNCAT and modified it to apply to a movie context rather than the real world. The largest point of departure between the UNCAT definition and our working definition is that the UNCAT stipulates that a public official must be involved in order for an incident to be considered torture. This is likely due to the UNCAT’s status as a legal document more than a statement on the meaning of the word. Since human rights agreements are treaties among states to limit their own actions, one would presume that prohibiting torture from non-state actors is outside the scope of the UNCAT. For the purposes of our study, we see no reason why movie viewers would make such a distinction in terms of how the scene informs their attitudes about torture. If torture works, it works, whether you’re a private or government actor.Footnote 5

How to conceive of public officials was but one of the many conceptual hurdles we faced in quantifying the amount of torture in popular movies. Beyond the identity of the perpetrator, we often found the act itself difficult to define. In our sample there were a number of cases in which victims underwent extreme physical or psychological pain, but the victims accepted such pain willingly for one or another reason. Much like the U.S. military’s Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) program which infamously subjects its trainees to various forms of torture, all of the victims in such scenes were capable of ending the torture through voluntary withdrawal. As such, we cannot consider it torture.

There are also scenes in which torture is mentioned or described, but never shown on-screen. As a rule, we decided to only include off-screen torture if we later see the results of this torture (in the form of injuries or dramatic changes in behavior) on the screen.

The decision of whether to include the threat of pain or death was one of the trickier decisions we were forced to make for this project. One would intuitively consider the threat of imminent death or pain to be a form of psychological torture, and many examples of this would be uncontroversial to include. However, sometimes the threat of death or pain is a reaction to an immediate threat to one character posed by the other character—such as pulling a gun.Footnote 6 We clarify these decisions based on the threat (or lack thereof) posed by the victim: If the threat of death is intended to counter a direct and immediate personal threat (real or potential) posed by the victim, we do not consider it torture. Unlike the Ill Treatment and Torture (ITT) dataset (Conrad and Moore Reference Conrad and Moore2012), we do not require that victims be detained in order to be tortured. Victims are indeed detained in the majority of cases, but the supernatural nature of some movies make “detention” difficult to define.

Finally, wide-scale atrocities also merit a mention. The dividing line we decided to draw between these cases and more traditional forms of torture is one of scale: Torture is conducted against specific individuals, not classes or groups of people, and not people selected via lottery. Those examples given earlier are surely heinous crimes against humanity, but they are crimes which by virtue of their scale are beyond the scope of the crimes we seek to investigate here.

What Torture Is Not

By the UN definition, torture “does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.” As such, we therefore exclude any and all injuries sustained that were incidental to or necessary for disabling an active threat. For example, attacking a guard warrants a physical response that would not be coded as torture, but if the guard continues to harm the attacker after they are incapacitated or no longer an active threat, then that would be punitive torture. Moreover, we exclude pain that is incidental to murder, capital punishment, or other forms of killing. Violent death is often painful for the victim, but the pain itself isn’t the point. We do not exclude, however, forms of legal sanction or killing where pain itself is a core goal.

It will come as no surprise to learn that movies contain a wide variety of violent crimes perpetrated against a similarly wide variety of victims. We exclude cases of harm to a non-anthropomorphic victim on the basis that, legally, torture can only be applied to humans. We specify non-anthropomorphic as opposed to non-human because popular movies are rife with talking animals, aliens, and even gods that nonetheless interact and communicate with other characters in a fully human manner. Specifically, we draw the line at communication: beings incapable of communicating their thoughts in a recognizable language are thus incapable of themselves being tortured.

Coding Process

We created a codebook so we could measure variables of theoretical importance in the context of torture. As shown in online appendix C, we coded thirty-seven variables that measure details about the incident itself, the perpetrator(s), and the victim(s). We also included a detailed text summary of the scene. After creating the codebook, we completed an initial inter-rater reliability test. We selected three movies and the two authors coded each movie on the thirty-seven established variables. Each variable was coded as 0=no; 1=yes; -88=unclear. Interrater reliability (k=0.88) was well above the common threshold of 0.7 (Landis and Koch Reference Landis and Koch1997). We discussed any coding discrepancies and finalized our codebook. We then divided the remaining movies between the two authors and completed coding. Initially, we erred on the side of being overly inclusive to prevent potential torture incidents from being missed. After coding all movies for all possible torture scenes, both authors separately revisited each potential torture incident to make final determinations on whether or not to include each scene in the dataset used for analyses. We discussed all coding decisions until a final determination was made for each scene identified in the initial, inclusive coding. In this final process, we erred on the conservative side in an effort to understate our case. Our aim here is to only include scenes where torture is clearly used. We excluded any incidents where it was unclear whether or not the actions amounted to torture. We also did not include depictions of violence in general, which would have greatly increased the number of incidents. As a robustness check, we also conducted all analyses to include borderline cases though this did not change any of the results reported in text.

Variables

We break down the variables into four sets: movie-level, incident-level, perpetrator-level, and victim-level. Table 1 shows a summary of these variables overall. We also break down each variable by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA)’s film rating system (G, PG, PG-13, R) to visualize how trends in torture depiction vary across categories of films.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics

Movie-Level Factors

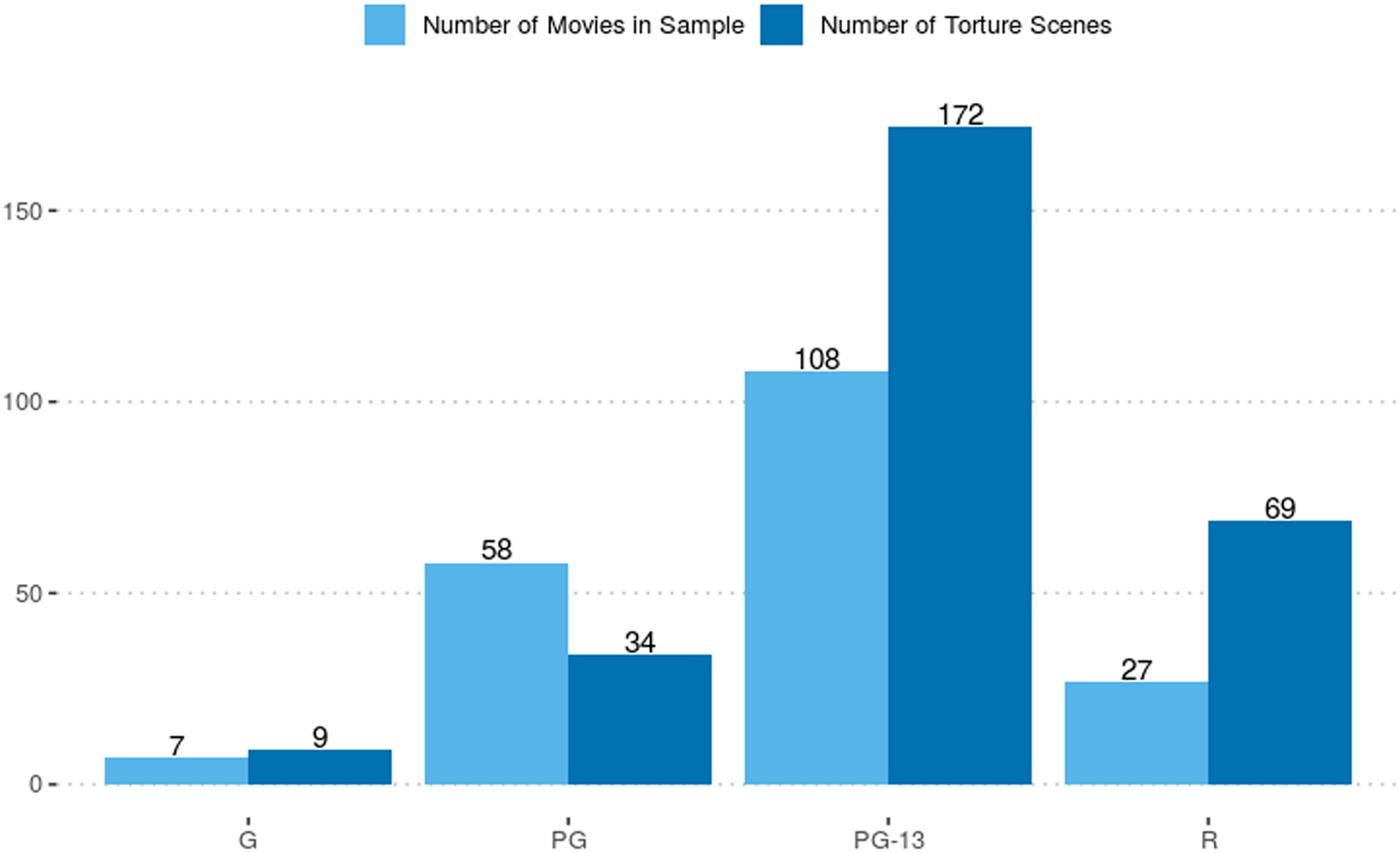

Most of the movies that we coded (59.5%) contained at least one torture scene. On average, each movie contained 1.4 torture scenes, though this ranged from 0 to 14 scenes per movie. Figure 1 compares the frequency of films in our sample and the number of torture scenes by MPAA rating. Nearly half of G (42.9%) and PG (44.8%) movies contained at least one torture scene. Similarly, more than half of PG-13 (64.8%) and R (74.1%) movies contain torture. In short, torture is prevalent in popular movies. Further, the prevalence of torture in movies is fairly consistent across the ten years we examined. Refer to online appendix A for a figure depicting the number of torture scenes in each film across rating and year.

Figure 1 Breakdown of sample by MPAA rating

Incident-Level Factors

Goals. As defined earlier, the goals of inflicting torture are instrumental or punitive; these are not mutually exclusive. Instrumental torture is conducted with the aim to either coerce the victim into doing something or to gain information on various topics including another character, something that has happened, or something that will happen—either specifically and imminently like the ticking time bomb paradigm (i.e., threat variable) or a more general threat of attack at some potential unknown future time. Overall, most torture scenes have an instrumental goal only (55.5%).Footnote 7 Punitive torture is conducted with the aim to hurt the victim. About one-third of the scenes involve punitive torture only (33.5%). Sometimes torture is both punitive and instrumental, which accounts for the remaining 11.1% of the scenes. In G movies, torture is mostly used for instrumental reasons only (88.9%). By contrast, R movies are more likely to show torture for only punitive (48.5%) or a combination of punitive and instrumental reasons (8.8%).

Outcome. Debates on torture often center around its efficacy. Punitive torture no doubt achieves its desired outcome to harm. In the context of justifying torture, however, efficacy refers to producing the information or action desired by the perpetrators. For this reason, we consider efficacy only for the 187 scenes where at least part of the goal was instrumental. Torture was effective in nearly three-quarters (72.7%) of the scenes where torture was used for instrumental purposes, even when counting cases in which victims were incapable of complying. Again, the frequency here varies across movie ratings but does not suggest a trend.

Type. Torture involves either physical or psychological harm, which are not mutually exclusive categories. Overall, nearly half of the torture scenes depict physical harm only (47.0%) whereas just over one-quarter show psychological harm only (27.9%).Footnote 8 Another quarter (25.1%) of the scenes show both physical and psychological harm. Interestingly, the two types of harm are shown in relative parity for G and PG movies, though physical harm is far more prevalent in both PG-13 and R movies.

Perpetrator-Level Factors

Role. Overall, most torture perpetrators were antagonists (61.3%) rather than protagonists (34.9%). Across movie ratings, the breakdown of who tortures is fairly consistent.

Demographics. Overall, perpetrators were mainly both white Footnote 9 (72.2%) and male (85.6%), although it is hard to tell whether this is merely a reflection of the typical demographics of movie subjects versus privileging white perspectives (Goldberg Reference Goldberg and David Slocum2001; Middleton Reference Middleton2010). In G and PG movies most perpetrators are not white and a lower percentage of perpetrators are male. However, perpetrators were mostly non-human in G movies (88.9%) and over one-third were non-human in PG movies (38.2%), which makes sense given the number of animated children’s movies in the sample. In PG13 (8.7%) and R (1.5%) movies, very few perpetrators were non-human.

Victim-Level Factors

Role. While torture perpetrators tend to be antagonists, the victims tend to be protagonists (51.4%). However, antagonists are the victim in about one-third of the scenes (33.5%). This breakdown in roles is fairly consistent across movie ratings.

Poses a specific, existing threat. Since torture is often justified using hypothetical “ticking time bomb” scenarios, we measured all instances where torture is intended to counter an existing, specific threat to the life of at least one person. The specificity of threat is important: Whereas perpetrators may torture in order to get information on a person or group considered dangerous, we do not code them as posing a threat unless there is a specific attack (known to the perpetrators) that they plan to carry out. A real-life example to clarify: Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) was reportedly waterboarded at least 183 times in order to reveal information about Al-Qaeda (Feinstein Reference Feinstein2014) though he likely had no knowledge of specific upcoming attacks. While the existence of Al-Qaeda is certainly threatening, we would not in this instance consider KSM’s torture to be in response to a specific threat to the life of at least one person. We exclude the temporal dimension of threat because, in many films, it is difficult to ascertain the specific length of time that has passed between scenes. Likewise, it is unclear whether there is a limit on how long a “time bomb” can “tick.” Finally, time travel makes the temporal dimension of threat even more difficult to measure. There is at least one instance wherein the perpetrator has traveled back in time to prevent an attack, the specificity of which is only revealed in the future. So, a torture scene was only coded as presenting an existing and specific threat when it was clear that a) an attack was going to happen without external intervention and b) that attack threatened the life of at least one specific person. Due to the temporal constraints of the show 24, scenes where a bomb is going to go off in a few hours and only the suspect in custody has the information to stop it were prevalent. Yet in films that are outside of the time constraint of depicting events in real time, victims of torture posed a threat in very few of the scenes (14.4%). Interestingly, the victim did not pose a threat in any of the torture scenes featured in R movies.

Inability to comply. Torture can also be used against someone who does not possess the ability to comply or have the information that the torturer wants. Compliance assumes that the torturer’s goal is instrumental, so we coded this as not applicable for scenes where the goal was only punitive.Footnote 10 Out of the torture scenes where the goal was not solely punishment, the victim was unable to comply in a small percentage of scenes (13.5%). In G movies, all of the victims had the ability to comply. As the MPAA rating increases, the percentage of victims who have were unable to comply steadily increased to 29.4% in R movies.

Female victim. We create a binary variable for female victim. Of all torture victims depicted across movies, 26.8% were women. While few torture victims in G movies are female, the prevalence of female victims was fairly consistent across PG to R films.

Demographics. Similar to torture perpetrators, torture victims also tended to be white (69.7%) and male (87.0%) though, again, this may be a mere reflection of demographics in movies rather than privileging of a white perspective (Goldberg Reference Goldberg and David Slocum2001; Middleton Reference Middleton2010). However, in G movies most victims are not white and in both PG and R movies only half of victims are white. Again, we see that victims are disproportionately non-human in G (88.8%) and PG (41.2%) movies while non-human victims are rare in PG13 (6.4%) and R (1.5%) movies.

Results

The central aim of this project was to assess the frequency and nature of cinematic depictions of torture. We next test our hypotheses about dramatic depictions of torture in recent popular movies.

Torture’s Efficacy

We first test our hypothesis about the efficacy of torture in movies. In H1, we expect that instrumental torture is effective most of the time. We use a one-sample t-test to examine the actual efficacy rate against the comparison rate of 50% effective since anything above that would be considered most of the time.Footnote 11 Results show that instrumental torture is effective most of the time, t(186)=6.96, p<0.001. Of the scenes where instrumental torture was used, it worked 72.7% of the time. When we conducted separate t-tests by movie rating, we found that instrumental torture is depicted as effective most of the time for G (p=0.01), PG13 (p<0.001), and R (p<0.001) movies but not for PG ones (p=0.14). It is important to note that, when disaggregating films by MPAA rating, we begin dealing with sample sizes that are fairly small. As such, significant results are quite meaningful given the low statistical power, and null results (such as that found for PG movies) may well be an artifact of our small sample size. Figure 2 presents these results in visual format.

Figure 2 H1: Effectiveness of instrumental torture (one sample t-test using hypothetical mean of 0.5)

Who Tortures and the Acceptability of Torture

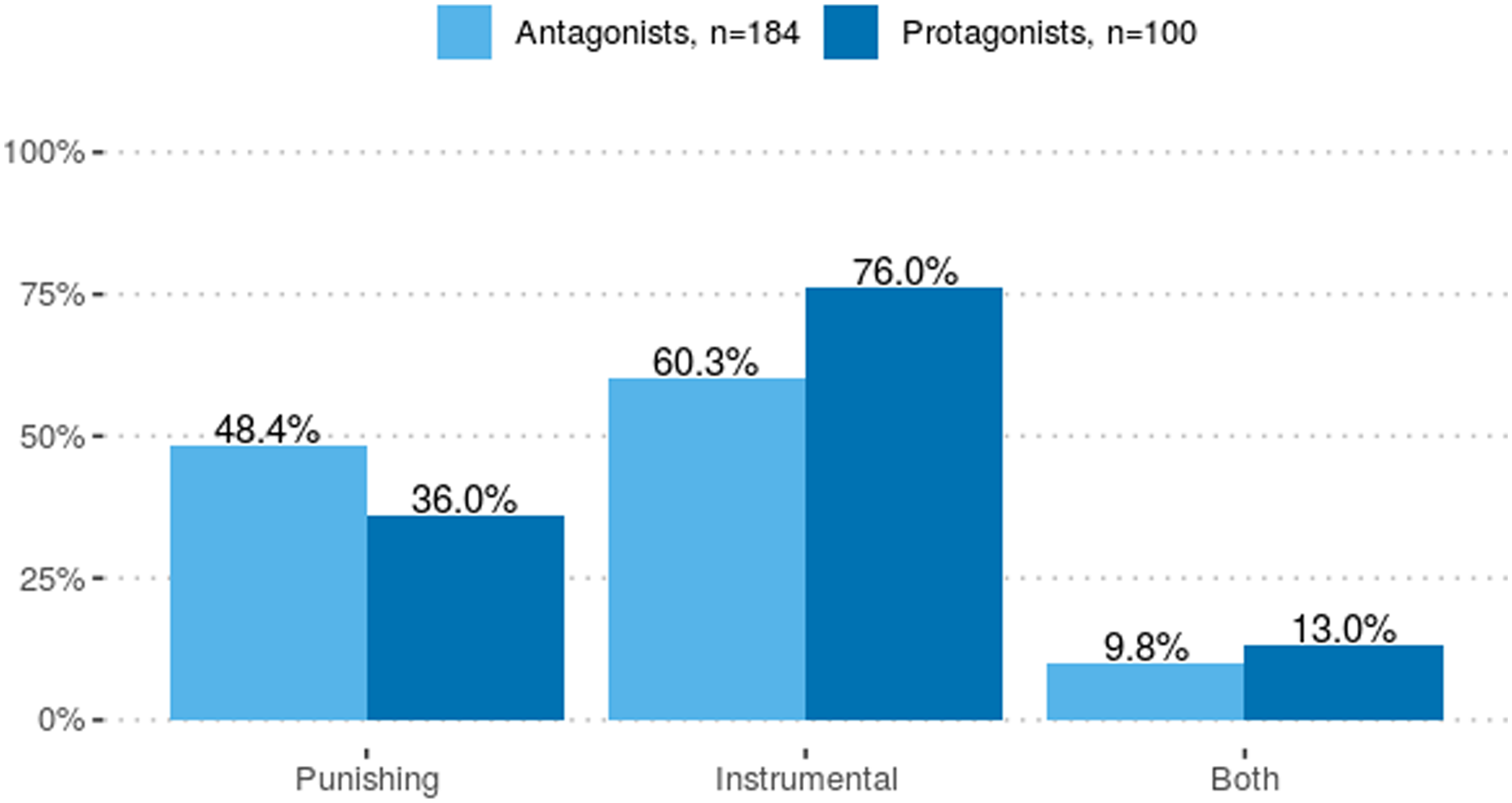

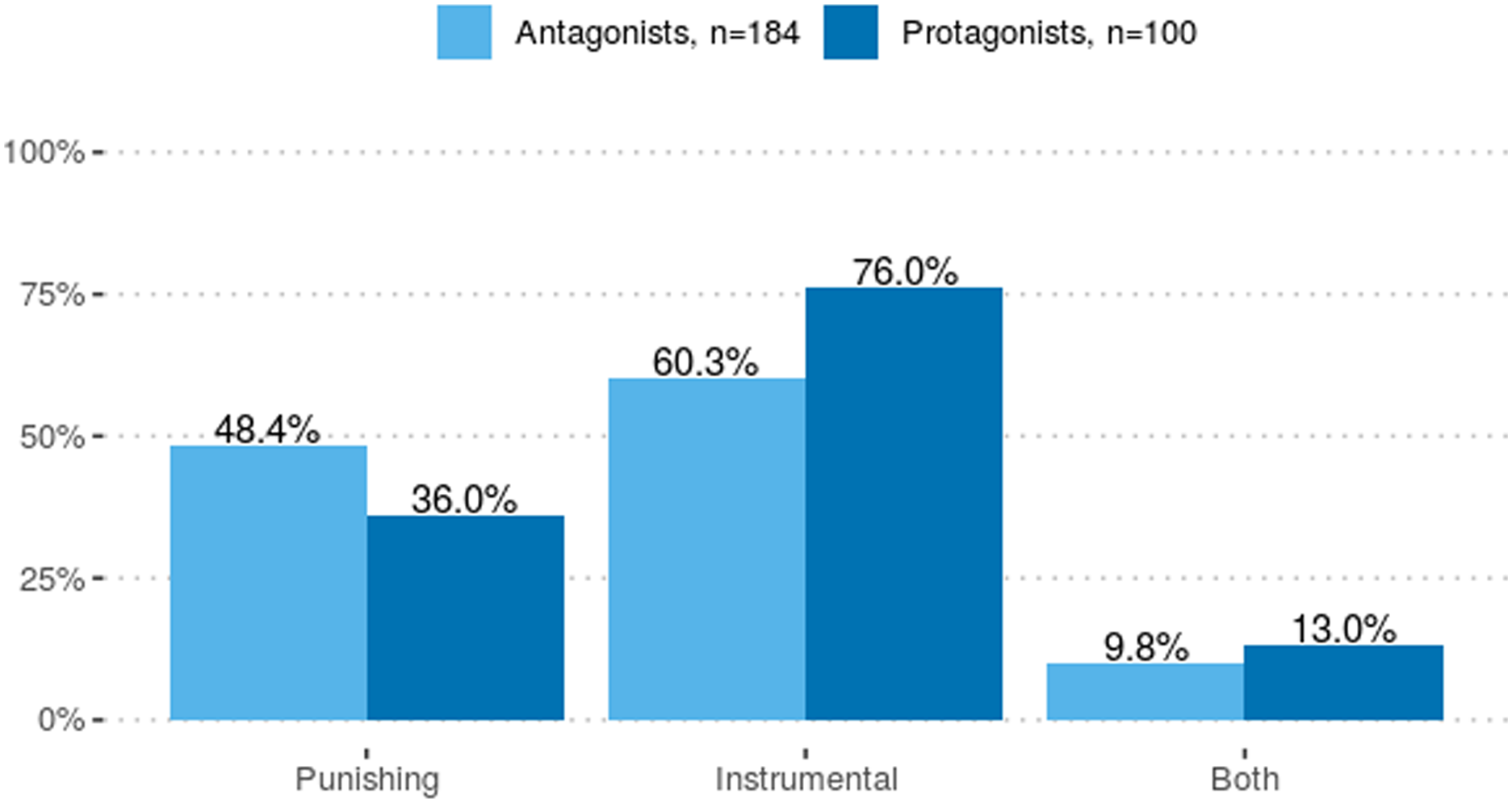

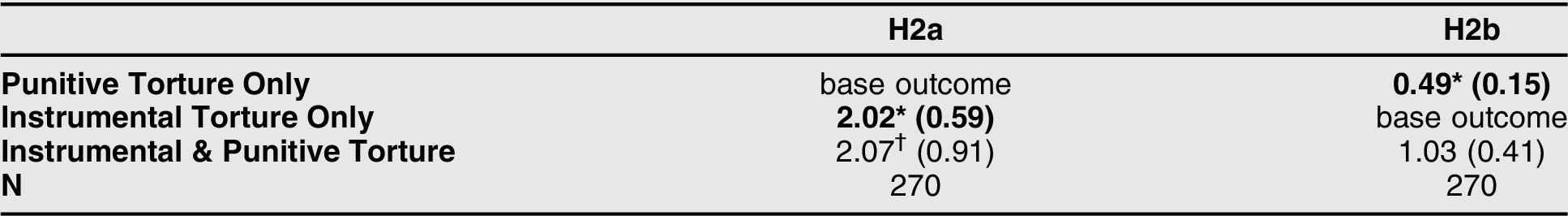

We expect that protagonists engage in torture under more acceptable conditions while antagonists engage in torture under less acceptable circumstances. First, we look at the goal of torture, which can take one of three mutually exclusive categories: instrumental only, punitive only, or both instrumental and punitive, as shown in figure 3. Accordingly, we estimate these models using multinomial logistic regression with a binary variable for protagonist perpetrator.Footnote 12 To ease interpretation of coefficients we present relative risk ratios in table 2, which are similar to odds ratios in logistic regression. Supporting H2a, we find that protagonists are more likely than antagonists to use instrumental torture.Footnote 13 Supporting H2b, we find that protagonists are less likely than antagonists to use punishing torture. We see no differences in the simultaneous use of both instrumental and punitive torture between protagonists and antagonists.

Figure 3 Torture scenes by goal and perpetrator

Table 2 Depictions of Torture Type and Goal by Perpetrator (Protagonist dummy)

Multinomial logistic regression models. All models are estimated with one independent variable— a dummy for protagonist perpetrator where protagonist perpetrator=1 and antagonist perpetrator=0. Constants not reported.

Relative risk ratios are presented with standard errors in parentheses.

†p < 0.10. *p < 0.05. **p <0 .01. ***p< 0.001.

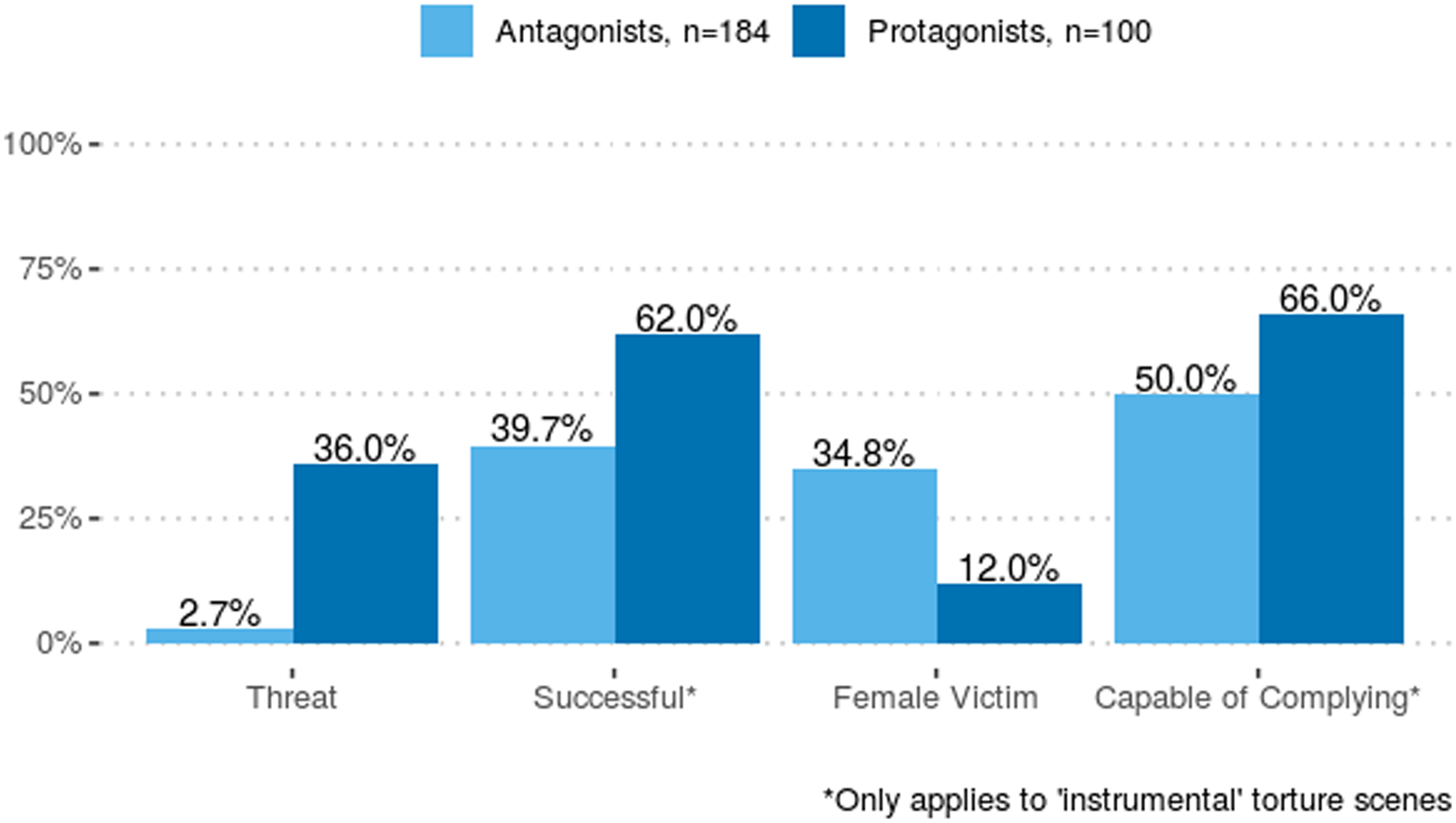

Figure 4 shows the reasons for torture and the outcomes from torture for both protagonists and antagonists. Next, we used t-tests to examine if there are significant differences on these variables between protagonists and antagonists.Footnote 14 Supporting H3, we found that protagonists are more likely than antagonists to torture in response to a specific, existing threat, t(271)=8.31, p<0.001. The effect size is large (d=1.05). Supporting H4, when used for an instrumental goal, protagonists are more likely than antagonists to be effective when they torture, t(179)=2.02, p=0.02.15 The effect size is small (d=0.31). As expected in H5, protagonists are less likely to torture women than antagonists, t(271)= 4.74, p<0.001. The effect size is medium (d=0.60). Finally, we found that protagonists and antagonists were equally likely to torture people who were incapable of complying, t(177)=0.96, p=0.17, which was contrary to our expectations in H6.

Figure 4 Torture scenes characteristics by perpetrator

Discussion

Our main aim for this project was to examine how frequently—and in what context—torture is shown across popular media. Most of the twenty top-grossing films in the previous decade depict at least one instance of torture. Further, torture is depicted regularly across MPAA movie ratings including those geared toward young audiences. While Mutz and Nir (Reference Mutz and Nir2010) suggest that any audience effects from media result from the net message sent, Bennett and Iyengar (Reference Bennett and Iyengar.2010) argue that media effects are likely minimal due to inconsistent messaging across sources. As we find with torture, however, the messaging is largely consistent. Results show that movies generally depict torture for instrumental purposes and it is mostly shown as effective, which supports Goldberg’s (Reference Goldberg and David Slocum2001) expectation that torture would be depicted in ethically fraught ways. While we cannot draw a direct connection from movie depictions of torture to public views of it, we do see parallels. The public receives their information about torture from media, which may help explain why many people assume that torture is effective.

We also see clear differences in how torture is depicted depending on whether the perpetrator is the protagonist or antagonist. In short, protagonists tend to engage in more acceptable forms of torture than antagonists. Protagonists are more likely than antagonists to use instrumental torture and less likely to use punitive torture. This suggests that protagonists are more likely to use torture when there is no perceived alternative while antagonists are more inclined to use torture as retribution. Protagonists are more likely to torture in response to threat and, when they do, they are more effective than antagonists. Further, while antagonists tend to torture more vulnerable people, protagonists do not. Overall, movie depictions of torture further propagate the narrative that the “good guy” tortures out of necessity to gain information that successfully averts disaster.

The disparity between the actions of protagonists and antagonists is notable because, as mentioned prior, protagonists exist as a means for viewers to “see themselves” in the film’s core story (Brereton and Culloty Reference Brereton and Culloty2012; Snyder Reference Snyder2005). Therefore, the actions taken by protagonists may simultaneously reflect and crystallize societal attitudes about torture and its social acceptability as Belton (Reference Belton1994) suggests. Thus, the forms of torture undertaken by protagonists can give insight into the kinds of torture considered “socially acceptable” by the general public. Indeed, most polling indicates that public support for torture is conditional on the forms that torture takes. For example, respondents are more likely to support torture when framed in a national security context or as necessary in response to an imminent threat (Armstrong Reference Armstrong2013; Conrad et al. Reference Conrad, Croco, Gomez and Moore2018; Davis Reference Davis2007; Davis and Silver Reference Davis and Silver.2004). Likewise, respondents are more likely to support “clean” forms of torture rather than more physically coercive ones (Gronke et al. Reference Gronke, Rejali, Drenguis, Hicks, Miller and Nakayama2010; Mayer and Armor Reference Mayer and Armor2012). While it is beyond the scope of this paper to determine whether there is indeed a causal connection between film and public opinion on torture (or which way that causal arrow might point), it is still notable that we see such agreement between public opinion on torture and protagonists’ actions.

Conclusion

Limitations and Future Directions

The present study is a first attempt to systematically examine the prevalence and nature of depictions of torture across popular media. Like any project, this work is not without its limitations, which we address here and suggest ways to address them in future research. While we examine 200 popular movies over a ten-year period, this is a small slice of the available media. Our results highlight popular media depictions of torture in the United States in recent years but are far from conclusive.

There are, of course, resource constraints that limit the feasibility of examining torture across a broader swath of media. Still, future research should examine the extent to which our findings hold across other forms of media, geographic locations, and time. First, future research should examine how torture is depicted across popular television shows beyond just 24 or other terrorism-focused shows. Perhaps torture is used as a plot device in different ways in media that is serialized and occupies more screen time. Second, research should examine and compare how depictions of torture in popular U.S. movies relate to movies that are popular in other countries. Even across democratic states, there are differences in public support for torture. Perhaps audiences abroad have a lower appetite for this kind of violence so it is shown less. Or, perhaps foreign media depict torture less often so audiences are not as primed to view it as acceptable or receive counter-messaging that makes torture less appealing to support.

We are particularly interested in how the prevalence of torture in movies may have changed over time. While there doesn’t appear to be a positive or negative trend over our ten years of data, it is somewhat intuitive to surmise that the prevalence of torture in entertainment media increased after 9/11. If pop culture is a reflection of the society that produces it, it would make sense that an increase in the centrality of torture to the public discourse would be matched by an increase in torture’s presence in media. That said, Goldberg (Reference Goldberg and David Slocum2001) discussed torture in films prior to 9/11 and anecdotal speculation yields a number of pre-9/11 movies with high-profile torture scenes, such as those in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994) or Reservoir Dogs (1991). While some may contend that Tarantino films are notably violent exceptions, L.A. Confidential (1997) is ostensibly a remake of decades-old noir films and contains multiple torture scenes. Without a systematic accounting of movies prior to 9/11, it is difficult to assess whether torture in movies is a recent phenomenon.

Our findings here show how torture is depicted in popular, recent North American films. Contrary to Bennett and Iyengar’s (Reference Bennett and Iyengar.2010) expectation, the message sent on torture is rather consistent—even in films outside of a national security context. What we cannot say, however, is the influence that these media depictions have on public perceptions of and support for torture. To probe this question and bolster the generalizability of previous studies, both longitudinal survey research and experimental studies could be used to identify the impact that media depictions of torture—particularly those that occur outside of terrorism and counterterrorism focused media—have on the public. Recent experimental studies have shown that seeing torture work can increase support for the practice among U.S. adults (Kearns and Young 2018, Kearns and Young forthcoming). Does this finding hold for younger people? Samples outside of the United States? When torture is depicted in a context outside of counterterrorism? Further, at present we cannot tease out the potential causal pathway between media depictions and public perceptions of torture. It is possible that media depictions influence policy. It is also possible that filmmakers think American audiences are more tolerant of instrumental torture when it works. Or, it is possible that both explanations are accurate and reinforce one another. To probe this, future experimental work could present participants with a depiction of torture that varies by goal (instrumental, punitive, both) and outcome (effective, ineffective, unclear) to measure the level of enjoyment of the scene and other attitudes toward it beyond just support for the practice.

Implications

Communications research has long suggested that media influence how the public perceive issues, especially when people lack direct, personal experience with the topic. Though more recently, Bennett and Iyengar (Reference Bennett and Iyengar.2010) argued that the inconsistent messages sent across media minimizes any potential audience effects. Yet our systematic examination of torture in popular film shows a consistent message: torture regularly appears in popular movies, is often shown to be effective, and is depicted in ways that perpetuate the narrative of “good guys” torturing out of necessity to avoid harm. Further, recent experimental work suggests that dramatic depictions of torture can influence both beliefs and behaviors. Since the vast majority of the U.S. public have not experienced torture, people reasonably rely upon media to frame the practice. How torture is depicted in movies may help explain why a high percentage of U.S. adults think torture can be acceptable in counterterrorism.

As citizens of a democracy, our suggestion here is certainly not to constrain how media depict interrogations and torture. Rather, our aim is to draw attention to the prevalence of this trope and hope that screenwriters will exercise more caution in using torture as a plot device. Some entertainment media producers recognize the educational potential of the content they produce (Klein Reference Klein2011). In the context of torture, depictions may influence the public in ways that are incongruent with reality. To address this, perhaps screenwriters could seek input from interrogation professionals as an extension of extant relationships between the intelligence community and Hollywood (Jenkins Reference Jenkins2009). Torture scenes seem to be an easy crutch for screenwriters trying to inject tension and drama into a script, but they may have more fundamentally disturbing effects: Media depictions of torture may influence public opinion and policy, thus they should be used sparingly and in ways that are more reflective of reality.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A. Movies in Sample

Appendix B. Criteria for Inclusion

Appendix C. Variable Names and Descriptions (numbered variables = we coded)

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719005012