Introduction

During seed storage, lipid peroxy radicals cause membrane breakdown and cell ageing. Vitamin E, a group of eight homologues (four tocopherols and four tocotrienols), is a strong antioxidant that scavenges lipid peroxy radicals, hence they play a role in seed longevity (Sattler et al., Reference Sattler, Gilliland, Magallanes-Lundback, Pollard and DellaPenna2004; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Li, Fang, Shi and Chen2015; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kwak, Yoon, Lee and Hay2017). Our previous study using a diverse rice panel grown in the Philippines indicated that the ratio of different vitamin E homologues rather than total vitamin E content is crucial in extending seed longevity (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kwak, Yoon, Lee and Hay2017). In particular, a high proportion of γ-tocotrienol was correlated with high seed longevity. A better understanding of the molecular basis of seed longevity may help improve longevity and/or identify varieties that are short-lived in storage. We were therefore interested in understanding whether the relationship between vitamin E homologue ratios and seed longevity is still apparent when seeds are produced under different environmental conditions. In this study, we used seeds produced under temperate conditions to assess the correlation between seed longevity and vitamin E.

Experimental

Seeds of 20 Oryza sativa accessions held in the T.T. Chang Genetic Resources Center at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), representing the five subpopulations of Indica and Japonica Variety Groups (Supplementary Table S1; IRRI, 2006a–q, 2007a–c)) were grown in the experimental field of the Rural Development Administration (RDA), Republic of Korea (N35° latitude and E128° longitude) in 2016. During seed production, mean temperature and rainfall per day were 23.7°C and 6.3 mm, respectively. After dormancy-breaking (50°C, 5 d), seeds were germinated in seedling boxes and 30-d-old seedlings transplanted on 5 June 2016, with 300 × 150 mm2 spacing. Fertilizer, insect, disease and weed control were according to standard procedures. Five accessions did not flower. Seeds of the other 15 accessions were harvested between 50 and 56 d after heading and dried at 25°C, 30–40% relative humidity (RH). A sample of 300 g seeds of each accession were sent to IRRI for seed storage experiments; remaining seeds were used for vitamin E analysis. Eight vitamin E homologues (α-, β-, γ-, δ- tocopherol/tocotrienol) in lipid extracts of brown rice were analysed by ultra-performance liquid chromatography (H-Class system, Waters, USA; Ko et al., Reference Ko, Kim, Kim, Kim, Chung, Tae and Kim2003). Individual homologues were determined at 298 nm excitation and 325 nm emission with a Lichrospher Si-60 column (250 × 4.6 mm i.d.; Merck Co. Germany) and quantified based on retention time and amounts of standards (Darmstadt, Germany; Helios, Singapore). Seed longevity parameters were determined at IRRI through standard storage experiments (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Timple and van Duijn2015, Reference Hay, Valdez, Lee and Sta Cruz2018). After moisture content (MC) equilibration at 20°C, 60% RH, seeds were heat-sealed inside aluminium foil bags and placed at 45°C. Samples were taken at 3-d intervals and tested for the ability to germinate on two layers of Whatman No. 1 filter paper in 90 mm-diameter Petri dishes. Additional samples were used for monitoring MC: ground seeds were weighed before and after 2 h oven-drying at 130°C (ISTA, 2018). The mean MC was 10.3% (mean of all accessions and sample times). Germination data were analysed by probit analysis in GenStat v. 18 (VSN International Ltd., Hemel Hempstead, UK). Correlations between seed longevity parameters and proportion of vitamin E homologues were determined using STAR v2.0.1 (IRRI). Genomic information in the region of vitamin E-related genes were extracted from the 700k high-density single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) marker data (McCouch et al., 2016).

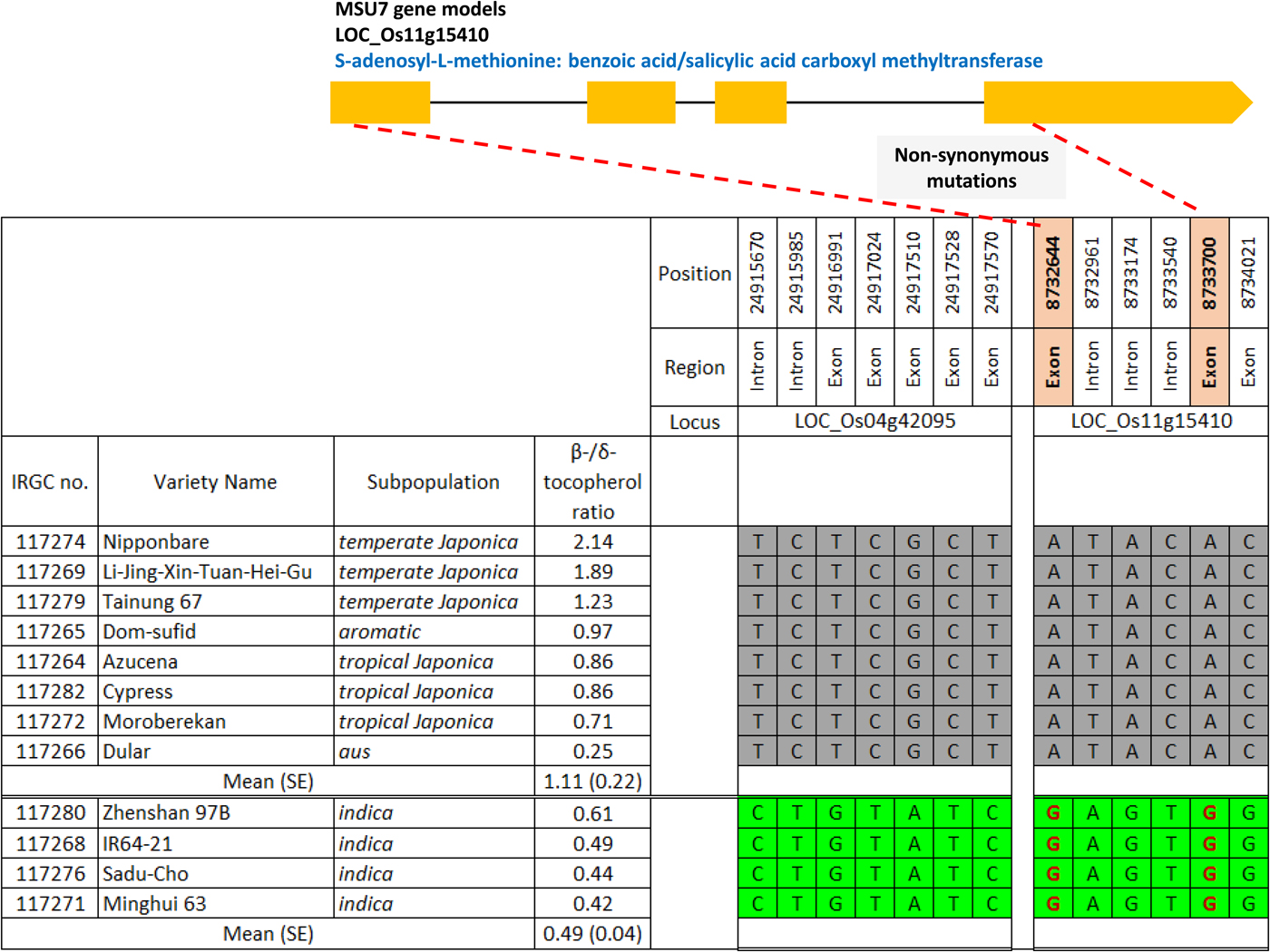

The estimate for K i (initial viability in normal equivalent deviates (NED)) ranged between 1.10 and 10.90 NED (mean 5.66 NED; Supplementary Table S1). The slope of the survival curves, −1/σ, ranged between 0.18 and 0.44 NED/d (mean 0.16 NED/d). Time for viability to fall to 50%, p 50, ranged between 5.73 and 34.58 d (mean 18.75 d). Total vitamin E content varied between 9.53 and 21.66 mg/kg brown rice (mean 15.80 mg/kg). The proportion of γ-tocotrienol was significantly positively correlated with p 50 (r = 0.516; P < 0.05) (Table 1). In contrast, the proportion of β-tocopherol was significantly negatively correlated with K i (r = −0.533; P < 0.05) and p 50 (r = −0.740; P < 0.01). There was no significant correlation between −1/σ and any of the vitamin E homologues. Using the public rice genomes database (Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Fuentes, Borja, Detras, Abriol-Santos, Chebotarov, Sanciangco, Palis, Copetti, Poliakov, Dubchak, Solovyev, Wing, Hamilton, Mauleon, McNally and Alexandrov2017; Rice SNP-Seek Database: http://snp-seek.irri.org/, latest access on 26 January 2019), we determined the DNA haplotype of 12 accessions in the region of six known S-adenosylmethionine synthetase (SAM) genes which regulate the conversion of δ-tocopherol into β-tocopherol (Sattler et al., Reference Sattler, Gilliland, Magallanes-Lundback, Pollard and DellaPenna2004). The association between haplotype and β-/δ-tocopherol ratio was assessed. Clear allelic variations were observed in the region of two SAM genes: LOC_Os04g42095 and LOC_Os11g15410. Four accessions belonging to the indica subpopulation with the favourable haplotype (shaded green in Fig. 1) showed a 2.3-fold lower β-/δ-tocopherol ratio (mean 0.49) compared with the eight accessions having the unfavourable haplotype (shaded grey) (mean 1.11).

Table 1. Correlation coefficients (r) between seed longevity parameters and proportions of vitamin E homologues for 15 diverse rice accessions.

* and **, significant at P < 0.05 and 0.01, respectively. ns, not significant (P > 0.05).

Fig. 1. Haplotype analysis on two S-adenosylmethionine synthetase genes regulating δ-tocopherol conversion into β-tocopherol for 12 rice accessions (IRRI, 2006a-c, e-f, h-i, k, m, p-q; 2007, b). Green shading indicates the favourable haplotype, grey shading the unfavourable haplotype; non-synonymous mutations are shown in red font. Three accessions, IRGC 117270, 117273 and 117277 (IRRI 2006g, j, n), were not included in the high-density SNP data set.

Discussion

Consistent with Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Kwak, Yoon, Lee and Hay2017), the proportion of γɣ-tocotrienol relative to other vitamin E homologues in the caryopses was significantly positively correlated with seed longevity (p 50). Further, a high proportion of β-tocopherol relative to δ-tocopherol was significantly negatively correlated with K i and p 50. Vitamin E α-/β- homologues have inefficient molecular structures for scavenging free radicals compared with γ–/δ- homologues (Jiang, Reference Jiang2014; Kim Reference Kim2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kwak, Yoon, Lee and Hay2017). LOC_Os11g15410 is annotated to S-adenosyl-L-methionine: benzoic acid/salicylic acid carboxyl methyltransferase, but its network function has not been validated. In four indica accessions with high seed longevity, there were two non-synonymous mutations (positions 8,732,644 and 8,733,700). An insertion at position 8,733,744 and a deletion at position 8,733,747 may be linked to the mutation at position 8,733,700 (Rice SNP-Seek Database: http://snp-seek.irri.org/, last accessed 26 January 2019). These functional changes might be responsible for inhibition of δ-/β-tocopherol conversion resulting in less β-tocopherol and greater seed longevity. This hypothesis needs validating since the favourable haplotype was specific to the indica subpopulation and all other groups have the unfavourable haplotype. Further research such as transgenic experiments could be used to validate gene function. A better understanding of the molecular basis for seed longevity will facilitate screening of genebank accessions for this trait and ultimately, rationalization of retest intervals.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S147926211900008X.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a grant from the Rural Development Administration, Korea (RDA) as RDA-IRRI cooperative research project (Grant Ref. PJ012723). We thank Stephen Timple (IRRI) for technical support.